Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1388

July 31, 2014

Why Managers and HR Don’t Get Along

Have you ever noticed how ambivalent line managers are about the Human Resources function? On one hand, most of them want their HR people to be involved in key strategic decisions; on the other, they want to make sure that whatever they do is not perceived as an “HR program.” Managers often rely on their HR partners to help them build an effective team, but then chafe at them for forcing them to “follow the process.” The bottom line, as Ram Charan argued in his recent HBR article, is that many line managers are disappointed in their HR people.

While there may be many factors influencing their complex relationship, these three stand out:

First is the confusion about the role that HR is playing at any one time. As Dave Ulrich pointed out almost 20 years ago in his classic book, “Human Resource Champions,” there are actually four roles played by HR people: administrative expert, employee advocate, strategic business partner, and change agent. In some cases, an HR person specializes in just one of these roles (e.g. the manager of an HR call center is basically focusing on the administrative role). Many other HR professionals however, particularly generalists, switch back and forth between the roles, and when they (and their management partners) are not explicit about which role is being played, it creates misunderstandings.

For example, an HR person who was helping a team streamline a number of key planning activities switched the discussion from process mapping to employee performance assessment. The managers were puzzled and frustrated by the shift, because they felt that they were making progress and that HR was all of a sudden slowing them down. But the HR person was simply concerned about whether the team’s actions would eliminate some positions and wanted to make sure it was handled in a fair and equitable way. She had shifted her role from “change agent” to “employee advocate,” but because she had not been explicit about putting on a different hat, the rest of the team grew upset at the sudden change of direction. Unfortunately this happens all too often, particularly with HR generalists who play multiple roles. When it isn’t clear which role is being played at a particular time and why, managers become confused and then blame HR for not providing effective support.

Second, many managers don’t fully accept their own accountability for managing human capital, and instead want HR people to “take care of it” for them. They avoid or delay activities such as candidate interviews, performance assessments, employee feedback discussions, compensation reviews, responses to engagement surveys, and a host of others. Often this avoidance is based on a lack of time, skills, or interest – or anxiety about getting into tough interpersonal territory. No matter the reason, it leaves HR people acting like the process police and chasing after recalcitrant line managers, which does very little to enhance the relationship.

Finally, all too many HR people don’t take the time to truly understand their company’s business and the pressures facing its managers. It’s surprising how many HR people can’t explain their firm’s business model, competitive industry context, or critical product issues – much less be conversant with the key financial metrics. As Ram Charan noted, very few organizations encourage rotation between HR and line business roles; as a result, most HR people become functional or technical experts and miss out on the nuances (or basics) of the business. In the absence of this understanding, it’s often difficult for HR people to contextualize the critical human capital processes for managers, who then don’t know how to prioritize them.

The good news about these issues is that they are not impossible to resolve – although as in any two-way relationship, both sides have to join in the dance. Line managers have to accept that human capital management is a major part of their job that can’t be delegated or deferred; and HR professionals have to better understand the business and appreciate the performance challenges facing line managers. In addition, both parties need to be more explicit about what role HR needs to play at any given time.

Obviously this won’t happen overnight, but there are some easy steps that both sides can take to get started. For example, if you’re an HR manager, make a point of spending more time with business people and less with your HR counterparts. Don’t talk to them about HR, but about what they are doing in their jobs, their concerns, and their aspirations. If you’re a line manager, make sure that your colleagues in HR are engaged in your business reviews and encouraged to contribute, not just about human capital issues, but also about business decisions. If you keep asking, you might actually get some fresh perspectives.

Millennials Not Enthused About the Game of Golf

The number of Americans playing golf each year has declined about 17% over the past decade, and millennials’ coolness toward the sport has contributed to the trend: While the number of people ages 18 to 34 participating in sports such as running rose 29% from 2009 to 2013, the proportion playing golf fell roughly 13%, according to the Wall Street Journal. The U.S. Golf Association has launched a campaign to sell golfers on the cost and time benefits of playing just nine holes.

Produce Content Marketing That Customers Care About

You can’t just snap your fingers and produce great content. To get stories and images that people actually care about, you need to address the higher-order problems your customers are facing today or will face tomorrow. You have to do the sustained work of thinking through these problems and coming up with relevant insights.

Consider Adobe’s new content-marketing strategy. Several years ago the company’s mainstay business of graphics applications was struggling against new competition, including free software. In response, executives made a concerted effort to step back and think about customers’ most important graphics-related problems. They saw that although online retailers were putting up fancy websites, the companies weren’t connecting their accumulated consumer data to the pages in order to drive sales. So Adobe invested in R&D and made some analytics-based acquisitions in order to develop a platform to make that possible. Dubbed the Marketing Cloud, this new platform would enable websites to show the right images to the right customers at the right time.

Adobe then went on a content-marketing spree. A team of 20-plus experts traveled the world, posting blogs and speaking at digital-marketing forums. Wherever companies were talking about e-commerce, dynamic online environments, or analytics, Adobe wanted to be there — not just as a sponsor, but as a provider of insights. Those insights came from the research Adobe had done to develop the platform, as well as the data the platform was already generating from early adopters.

Retailers were all ears. Adobe’s intellectual offensive convinced them that the company had become a leading player in the field. The Marketing Cloud is now Adobe’s biggest source of revenue, contributing (along with a shift to software subscriptions) to the recent explosion of the company’s stock price.

Or consider DPR. You may not have heard of the company, but it’s a highly profitable global contractor in the notoriously difficult construction industry. Rather than duke it out in conventional bidding processes, DPR invested in the emerging practice of building information modeling, or BIM. The idea is to go beyond blueprints and “construct” a building ahead of time in digital format, an approach that can improve quality and reduce total costs.

BIM is complex, expensive, and still in development. But DPR has widely shared the knowledge and practices it has gained, in venues ranging from industry forums to a co-taught course at Stanford University. All of that content marketing not only increased the buzz about DPR in the industry; it also enhanced its customers’ perceived value of BIM. DPR executives didn’t mind that they were helping competitors get up to speed as well, because they wanted to elevate the entire industry around this new approach. They used content marketing for thought leadership, in the true meaning of the term.

For a B2C example, look at Home Depot, whose executives know that customers are eager to do as much of their own home-repair work as possible. For years the company has offered a series of how-to books, and now it has stocked its website with hundreds of videos. The physical stores offer free or low-cost classes in how to do the most common jobs. As new home-repair problems and new tools and materials emerge, Home Depot can easily expand and update this content and push it to new channels. Home Depot is helping customers become better do-it-yourselfers, and in the process it is strengthening its brand far more effectively than would have been possible through advertising.

The alternative to creating your own great content is to acquire content from outside sources. But if you do that, you’ll soon find yourself stuck in an arms race with your rivals, bidding up content that might be smart, flashy, and entertaining but is inauthentic to your brand and ultimately of little real value to your business.

The only route to sustainable success in content marketing is through helping customers navigate the crazy, pressured, opportunity-filled world we live in now. Once you’ve done that work, and turned it into practical insights and solutions, you’ll have plenty of powerful material to draw upon. And your content marketing will really hit home.

July 30, 2014

How to Tell a Great Story

We tell stories to our coworkers and peers all the time — to persuade someone to support our project, to explain to an employee how he might improve, or to inspire a team that is facing challenges. It’s an essential skill, but what makes a compelling story in a business context? And how can you improve your ability to tell stories that persuade?

What the Experts Say

In our information-saturated age, business leaders “won’t be heard unless they’re telling stories,” says Nick Morgan, author of Power Cues and president and founder of Public Words, a communications consulting firm. “Facts and figures and all the rational things that we think are important in the business world actually don’t stick in our minds at all,” he says. But stories create “sticky” memories by attaching emotions to things that happen. That means leaders who can create and share good stories have a powerful advantage over others. And fortunately, everyone has the ability to become a better storyteller. “We are programmed through our evolutionary biology to be both consumers and creators of story,” says Jonah Sachs, CEO of Free Range Studios and author of Winning the Story Wars. “It certainly can be taught and learned.” Here’s how to use storytelling to your benefit.

Start with a message

Every storytelling exercise should begin by asking: Who is my audience and what is the message I want to share with them? Each decision about your story should flow from those questions. Sachs says that leaders should ask, “What is the core moral that I’m trying to implant in my team?” and “How can I boil that down to a compelling single statement?” For instance, if your team is behaving as if failure is not an option, you might decide to impart the message that failure is actually the grandfather of success. Or if you are trying to convince senior leaders to take a risk by supporting your project, you could convey that most companies are built on taking smart chances. First settle on your ultimate message; then you can figure out the best way to illustrate it.

Mine your own experiences

The best storytellers look to their own memories and life experiences for ways to illustrate their message. What events in your life make you believe in the idea you are trying to share? “Think of a moment in which your own failures led to success in your career, or a lesson that a parent or mentor imparted,” says Sachs. “Any of these things can be interesting emotional entry points to a story.” There may be a tendency not to want to share personal details at work, but anecdotes that illustrate struggle, failure, and barriers overcome are what make leaders appear authentic and accessible. “The key is to show your vulnerability,” says Morgan.

Don’t make yourself the hero

That said, don’t make yourself the star of your own story. “A story about your chauffeured car and having millions in stock options is not going to move your employees,” says Morgan. You can be a central figure, but the ultimate focus should be on people you know, lessons you’ve learned, or events you’ve witnessed. And whenever possible, you should endeavor to “make the audience or employees the hero,” says Morgan. It increases their engagement and willingness to buy in to your message. “One of the main reasons we listen to stories is to create a deeper belief in ourselves,” says Sachs. “But when the storyteller talks about how great they are, the audience shuts down.” The more you celebrate your own decisions, the less likely your audience will connect with you and your message.

Highlight a struggle

A story without a challenge simply isn’t very interesting. “Good storytellers understand that a story needs conflict,” says Morgan. Is there a competitor that needs to be bested? A market challenge that needs to be overcome? A change-resistant industry that needs to be transformed? Don’t be afraid to suggest the road ahead will be difficult. “We actually like to be told it’s going to be hard,” says Morgan. “Smart leaders tell employees, ‘This is going to be tough. But if we all pull together and hang in there, we’ll achieve something amazing in the end.’” A well-crafted story embedded with that kind of a rallying cry means “you don’t have to demand change or effort,” says Sachs. “People will become your partners in change,” because they want to be part of the journey.

Keep it simple

Not every story you tell has to be a surprising, edge-of-your-seat epic. Some of the most successful and memorable stories are relatively simple and straightforward. Don’t let needless details to detract from your core message. Work from the principle that “less is more.” One of the biggest mistakes you can make is “putting in too much detail of the wrong kind,” says Morgan. Don’t tell your audience what day of the week it was, for instance, or what shoes you were wearing if it doesn’t advance the story in an artful way. But transporting your audience with a few interesting, well-placed details — how you felt, the expression on a face, the humble beginnings of a now-great company — can help immerse your listeners and drive home your message.

Practice makes perfect

Storytelling is a “real art form” that requires repeated effort to get right, says Morgan. Practice with friends, loved ones, and trusted colleagues to hone your message into the most effective and efficient story. And remember that the rewards can be immense. “Stories are the original viral tool,” says Sachs. “Once you tell a very compelling story, the first thing someone does is think, ‘Who can I can tell this story to?’ So, for the extra three minutes you spend encoding a leadership communication in a story, you’re going to see returns that last for months and maybe even years.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Consider your audience — choose a framework and details that will best resonate with your listeners.

Identify the moral or message your want to impart.

Find inspiration in your life experiences.

Don’t:

Assume you don’t have storytelling chops — we all have it in us to tell memorable stories.

Give yourself the starring role.

Overwhelm your story with unnecessary details.

Case Study #1: Embed conflict to motivate and inspire

Josh Linkner was worried his employees were becoming complacent. Then the CEO of ePrize, a Detroit-based interactive promotions company, Linkner had seen his company become the dominant leader in the online promotions industry almost overnight. In the mid 2000s, “we had double and triple growth every year,” he says. “I became worried that we would start clinging to our previous success instead of forging new success, and that our creativity would decline.”

“Greatness is often achieved in the face of adversity,” he says, “but we didn’t have a competitor to gun against.”

So he made up a fake nemesis. At an all-company meeting, he stood up and announced that there was a brash new competitor named Slither. “I told everyone they were bigger than us, faster than us, and more profitable,” he says. “Their investors had deeper pockets. Their footprint was better, and they were innovating at a pace I’d never seen.”

The story was greeted with chuckles around the room (it was obvious the company was a ruse), but the idea soon became embedded within ePrize’s culture. Executives kept reinforcing the Slither story with fake press releases about their competitor’s impressive quarterly earnings or infusions of capital, and soon the urge to best the imaginary rival began to drive improved performance.

“It inspired creativity,” Linkner says. “In brainstorming sessions, we used Slither as the foil. Instead of saying, ‘OK, guys, we have to reduce our production time. How are we going to do that?’ I would say, ‘The folks over at Slither just shaved two days out of their cycle time. How do you think they did it?’ The white boards filled with ideas.”

Case Study #2: Anchor the story in your personal experiences

Vince Molinaro, managing director of the leadership practice at Knightsbridge Human Capital Solutions, Canada’s biggest HR advisory, tells clients he knows exactly when his career direction snapped into focus. It was at his first job out of college, with an organization that helped needy individuals get back on their feet. Vince loved the mission but found the atmosphere uninspiring. “Everyone just went through the motions,” he says. “I remember thinking, ‘Is this it? Is this what working in the real world is like?’”

A senior manager named Zinta sensed that Vince wanted to have a bigger impact, and asked him to join several likeminded colleagues on a committee to make their workplace a more positive environment. They began to make subtle changes, and coworkers’ attitudes started to improve. “I saw firsthand how a single manager can change the culture of a place,” he says.

Then Zinta was diagnosed with aggressive lung cancer. In her absence, the office culture began to revert back. On a visit to see Zinta in the hospital, Vince told her about the disappointing turn of events. She surprised him with a confession: Since she had never smoked and had no history of cancer in her family, she was convinced that her disease was a direct function of putting up with a toxic work environment for so long.

Shortly after, Zinta sent Vince a letter telling him he would be faced with an important choice throughout his life. He could allow the negative attitudes of others to influence his behavior, or pursue professional goals because of the sense of personal accomplishment they offered. “In her time of need she reached out to me,” he says. “She was a mentor to me even though she didn’t need to be.”

Two weeks later, Zinta passed away. But the letter changed Vince’s life, inspiring him to leave his job and start his own consulting business devoted to helping people be better leaders. “I’ve seen the kind of climate and culture that a great leader can create,” he says. “For the last 25 years, I’ve tried to emulate that.” He still has Zinta’s letter.

When Vince first began sharing this story with his leadership clients, he was taken aback by their reaction. “There was a connection they had to me that was really surprising, he says. “It’s like they got me in ways that I wasn’t able to directly communicate.”

“It also gets them thinking about their own story and the leaders that have influenced them. In my case, it was a great leader. Sometimes it’s the really bad ones you learn a lot from.” Whatever the case, he says, the power comes from sharing your story with the people you lead so they better understand what motivates you.

5 Bad Reasons to Start a For-Profit Social Enterprise

Should a new social good organization choose a for-profit model or a nonprofit one? This is a question we face each year at my organization, Echoing Green, when we evaluate thousands of business plans from social entrepreneurs seeking start-up capital and support. This year, nearly 50% of those plans proposed using a for-profit model. And when we asked these entrepreneurs why, some of their reasons were just plain bad.

They are not alone. New entrepreneurs are increasingly starting for-profit firms whose primary purpose is social impact. Supporting this trend is a tremendous increase in capital available for “impact investing.” According to a recent JPMorgan/GIIN report, impact investors invested nearly $11 billion across 4,900 deals in 2013, up 250% from 2011.

At Echoing Green, the social impact of our portfolio is our highest priority, so we’re agnostic on which form the organization takes. With the new possibilities for for-profit models (including B Corps, L3Cs, etc.), social entrepreneurs now have more options. This can be a good choice for the right organization but too many entrepreneurs seem to be making the decision for the wrong reasons.

Here are some of the worst reasons we hear for starting a for-profit to do good:

Bad Reason #1: Only for-profits use “business discipline.” It’s easy to scan headlines and see undisciplined for-profit companies (take GM, American Apparel). If “business discipline” means a thoughtful, hard-nosed, numbers-driven, approach to delivering results, businesses such as Teach For America (with a $250M annual operating budget), the multi-billion-dollar-lending BRAC, or even institutions like Harvard University or the Cleveland Clinic are great examples of disciplined nonprofits. Clearly, for-profits don’t have a monopoly on discipline.

Bad Reason #2: Only for-profits can sell a product or service. This is a misunderstanding of corporate law in most countries. Whether your organization is a for-profit or nonprofit doesn’t typically affect your ability to sell products. There are some nuances in China and India, but in most parts of the world, and certainly in the U.S., nonprofits may sell products (Girl Scout cookies!) and for-profits can accept donations. In the 2013 class of Echoing Green Fellows, five of the 12 nonprofits earn revenue, and five of the seven for-profit companies have received donations.

Bad Reason #3: Only for-profits properly compensate employees. Many nonprofit social entrepreneurs earn a good living. And in sectors such as education or healthcare, nonprofit compensation is often at the same level as that of for-profits. But it is true that when nonprofit leaders earn salaries close to for-profit peers they are scrutinized. And it is certainly true that because nonprofits have no share ownership a Facebook-like founder’s payday is not in their future. Commitment to social entrepreneurship may mean lower lifetime earnings. So talk of “proper compensation” may be a signal that a particular entrepreneur is not a good fit for our model, which demands deep commitment to the social purpose.

Bad Reason #4: Only for-profits have a sustainable revenue model. There are usually two intertwined misconceptions here. First, there is the earned income fallacy (see Bad Reason #2). If an earned income model is most sustainable for a particular company, they can pursue it as a nonprofit. The second misconception, however, is that philanthropic revenue is somehow less reliable than earned income. The official statistics show that more than 50% of start-up for-profit businesses fail within the first five years. Earned revenue can be highly variable. And examples such as the United Way or the Catholic Church make it clear that organizations can rely heavily on donations and still be sustainable. In fact, according to the National Philanthropic Trust, when the S&P 500 fell by 45% after the 2007 recession, U.S. charitable giving dipped only 10%.

Bad Reason #5: Nonprofits are “old-fashioned” and only for-profits earn respect in their sectors. While few entrepreneurs express this sentiment directly, we do hear it. Entrepreneurs are deeply influenced by the people around them. In the early years of Echoing Green our applicants had often worked for nonprofits or gone through social justice-oriented law schools. These days our Fellows are more likely than ever to have an MBA. According to a recent survey by AshokaU, for example, 64% of universities that teach about social entrepreneurship do so via their business school, rather than public policy, social work, etc. And it seems that on a business school campus — and, truth be told, in many parents’ living rooms — starting a for-profit business has much more cachet than starting a nonprofit.

Of course, there are good reasons to set up a for-profit too. Echoing Green first supported a for-profit in 2007 and since then we have provided $10.4 million in start-up capital to 47 for-profit companies. Here are some of the best reasons we’ve heard for using a for-profit model:

Good Reason #1: When local laws require it. While most countries now allow some form of nonprofit corporation, in several places that classification comes with such challenging restrictions (no government protests in China, need parliamentary decree in Lebanon, difficult to raise money abroad in India) that it is not practical. In these cases, the best way to have a deep social impact may be through a for-profit.

Good Reason #2: If equity investment is the best way to get start-up capital. The rise of the impact investor is an important development in the social sector, and no social entrepreneur should leave mission-aligned money on the table. Joel Jackson (a 2011 Echoing Green fellow) launched Mobius Motors as a social purpose car manufacturer to democratize transportation in East Africa. Philanthropic donors were not able to provide the millions of dollars necessary to support design and production, so selling equity to mission-aligned investors made good sense. The trick here is not to lose sight that this will close off some philanthropic doors, and that equity investors will want to influence the business to get their money back.

Good Reason #3: To send a signal to key partners or others about the role of for-profit markets. In some cases an entrepreneur is working to improve for-profit capital markets or with for-profit entrepreneurs. David del Ser (a 2009 Echoing Green fellow) created Frogtek to provide big-company-quality business intelligence to raise the income of shopkeepers in the poorest parts of Latin America. As a for-profit, David can rely on a higher level of trust from his customers who know that they are facing similar challenges in the world.

Jane Chen (a 2008 Echoing Green fellow) did it right when she and her co-founders at Embrace began with a social goal to save lives with an innovative low-cost infant warmer, and chose the model (and then evolved it) that best served that goal.

The point of all this is not to prove that the for-profit or nonprofit form is inherently best for social impact. In fact, the point here is the opposite. Our best chance to make the world better is to agree that the choice among corporate structures should be made entirely in service of social impact.

Management’s Three Eras: A Brief History

Organization as machine – this imagery from our industrial past continues to cast a long shadow over the way we think about management today. It isn’t the only deeply-held and rarely examined notion that affects how organizations are run. Managers still assume that stability is the normal state of affairs and change is the unusual state (a point I particularly challenge in The End of Competitive Advantage). Organizations still emphasize exploitation of existing advantages, driving a short-term orientation that many bemoan. (Short-term thinking has been charged with no less than a chronic decline in innovation capability by Clayton Christensen who termed it “the Capitalist’s Dilemma.”) Corporations continue to focus too narrowly on shareholders, with terrible consequences – even at great companies like IBM.

But even as these old ideas remain in use (and indeed, are still taught), management as it is practiced by the most thoughtful executives evolves. Building on ideas from my colleague Ian MacMillan, I’d propose that we’ve seen three “ages” of management since the industrial revolution, with each putting the emphasis on a different theme: execution, expertise, and empathy.

Prior to the industrial revolution, of course, there wasn’t much “management” at all – meaning, anyone other than the owner of an enterprise handling tasks such as coordination, planning, controlling, rewarding, and resource allocation. Beyond a few kinds of organization – the church, the military, a smattering of large trading, construction, and agricultural endeavors (many unfortunately based on slave labor) – little existed that we would recognize as managerial practice. Only glimmers of what was to come showed up in the work of thinkers such as Adam Smith, with his insight that the division of labor would increase productivity.

With the rise of the industrial revolution, that changed. Along with the new means of production, organizations gained scale. To coordinate these larger organizations, owners needed to depend on others, which economists call “agents” and the rest of us call “managers”. The focus was wholly on execution of mass production, and managerial solutions such as specialization of labor, standardized processes, quality control, workflow planning, and rudimentary accounting were brought to bear. By the early 1900’s, the term “management” was in wide use, and Adam Smith’s ideas came into their own. Others – such as Frederick Winslow Taylor, Frank and Lillian Galbreth, Herbert R. Townes, and Henry L. Gantt – developed theories that emphasized efficiency, lack of variation, consistency of production, and predictability. The goal was to optimize the outputs that could be generated from a specific set of inputs.

It is worth noting that, once they gained that scale, domestically-focused firms enjoyed relatively little competition. In America, there were few challengers to the titans in the production of steel, petroleum products, and food. Optimization therefore made a lot of sense. It is also worth noting that in this era, ownership of capital, which permitted acquisition and expansion of means of production (factories and other systems), was the basis for economic well-being.

Knowledge began accumulating about what worked in organizational management. While schools dedicated specifically to business had been offering classes throughout the 1800s in Europe, the economic juggernaut US gained its first institution of higher education in management with the 1881 founding of the Wharton School. A wealthy industrialist, Joseph Wharton aspired to produce “pillars of the state” whose leadership would extend across business and public life. Other universities followed. The establishment of HBR in 1922 was another milestone, marking progress toward the belief that management was a discipline of growing evidence and evolving theory.

Thus the seeds were planted for what would become the next major era of management, emphasizing expertise. The mid-twentieth century was a period of remarkable growth in theories of management, and in the guru-industrial complex. Writers such as Elton Mayo, Mary Parker Follett, Chester Barnard, Max Weber, and Chris Argyris imported theories from other fields (sociology and psychology) to apply to management. Statistical and mathematical insights were imported (often from military uses) forming the basis of the field that would subsequently be known as operations management. Later attempts to bring science into management included the development of the theory of constraints, management by objectives, reengineering, Six Sigma, the “waterfall” method of software development, and the like. Peter Drucker, one of the first management specialists to achieve guru status, was representative of this era. His book Concept of the Corporation, published in 1946, was a direct response to Alfred P. Sloan’s challenge as chairman of General Motors: attempting to get a handle on what managing a far-flung, complex organization was all about.

But something new was starting to creep into the world of organization-as-machine. This was the rise of what Drucker famously dubbed “knowledge work.” He saw that value created wasn’t created simply by having workers produce goods or execute tasks; value was also created by workers’ use of information. As knowledge work grew as a proportion of the US economy, the new reality of managing knowledge and knowledge workers challenged all that organizations knew about the proper relationship between manager and subordinate. When all the value in an organization walks out the door each evening, a different managerial contract than the command-and-control mindset prevalent in execution type work is required. Thus, new theories of management arose that put far more emphasis on motivation and engagement of workers. Douglas McGregor’s “Theory Y” is representative of the genre. The idea of what executives do changed from a concept of control and authority to a more participative coaching role. As organizational theorists began to explore these ideas (most recently with efforts to understand the “emotional intelligence” factor in management, led by writers such as Daniel Goleman), the emphasis of management was shifting once more.

Today, we are in the midst of another fundamental rethinking of what organizations are and for what purpose they exist. If organizations existed in the execution era to create scale and in the expertise era to provide advanced services, today many are looking to organizations to create complete and meaningful experiences. I would argue that management has entered a new era of empathy.

This quest for empathy extends to customers, certainly, but also changes the nature of the employment contract, and the value proposition for new employees. We are also grappling with widespread dissatisfaction with the institutions that have been built to date, many of which were designed for the business-as-machine era. They are seen as promoting inequality, pursuing profit at the expense of employees and customers, and being run for the benefit of owners of capital, rather than for a broader set of stakeholders. At this level, too, the challenge to management is to act with greater empathy.

Others have sensed that we are ready for a new era of business thinking and practice. From my perspective, this would mean figuring out what management looks like when work is done through networks rather than through lines of command, when “work” itself is tinged with emotions, and when individual managers are responsible for creating communities for those who work with them. If what is demanded of managers today is empathy (more than execution, more than expertise), then we must ask: what new roles and organizational structures make sense, and how should performance management be approached? What does it take for a leader to function as a “pillar” and how should the next generation of managers be taught? All the questions about management are back on the table – and we can’t find the answers soon enough.

This post is part of a series of perspectives by leading thinkers participating in the Sixth Annual Global Drucker Forum, November 13-14 in Vienna. For more information, see the conference homepage .

Are Corporate Taxes Headed the Way of Prohibition?

Argument 1: Corporations that shift their legal residence overseas to avoid U.S. corporate taxes are flouting the spirit of the law. “I don’t care if it’s legal — it’s wrong,” President Obama said last week in Los Angeles. “We need to stop companies from renouncing their citizenship just to get out of paying their fair share of taxes.”

Argument 2: The U.S. corporate tax code is an ill-begotten mess that is driving companies into all sorts of weird behavior. “Moving legal headquarters abroad through cross-border mergers is a logical way for a growing number of U.S. companies to counter the competitive disadvantages imposed on them by the current U.S. tax system,” the bipartisan economic duo of Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Laura D’Andrea Tyson wrote in The Hill last week.

There’s something to both of these arguments, right?

It would be a disaster if the current trickle of corporate “inversions” turns into a flood, something Allan Sloan warned may be imminent in his wonderfully ill-tempered Fortune cover story about the phenomenon a few weeks ago. It’s not just the loss of tax revenue — in fact, as you can see in the chart below, corporate tax revenue has been shrinking as a percentage of economic activity for decades. What seems most hazardous is that if inversions become commonplace, this country’s corporate leaders will have effectively absolved their organizations of the responsibilities of citizenship, which could eventually have all sorts of ramifications beyond how much money they hand over to the IRS.

At the same time, U.S. corporate tax laws have become unique globally in both their ambition and ineffectuality. The U.S. has the highest statutory corporate tax among the world’s developed countries, at 39.1% (that’s a 35% federal rate plus the average of state rates), and is also one of the few countries that requires its corporations (and its citizens) to pay tax on their overseas earnings. Yet the GAO found last year that profitable U.S. corporations face an effective tax rate of only about 17%. As for those overseas earnings, multinational companies where intellectual property plays a big role (most notably Google and Apple) are increasingly able to distill much of their profit into what legal scholar Ed Kleinbard calls “stateless income” that will never be taxed unless they try to bring it back into the U.S. And again, as you can see in the chart below, corporate tax revenue has been shrinking as a percentage of economic activity for decades even while rates have remained high.

Going back to Argument 1 and Argument 2, you could portray this ineffectuality of the tax code as evidence of nothing other than corporate dastardliness. Or you could conclude that corporate taxes resemble Prohibition in the late 1920s: a set of laws that have lost their legitimacy, and can be flouted with little or no loss of social status.

Some economists have long questioned the legitimacy of corporate income taxes, because when corporate income is paid out as dividends or realized as capital gains, corporations and shareholders end up paying tax twice on the same income. Others argue that the burden of corporate income taxes ends up falling mostly on workers. In his classic early-1960s tract Capitalism and Freedom, Milton Friedman somewhat mischievously proposed that the corporate income tax be abolished and shareholders instead pay tax on all corporate income, whether it is paid out to them as dividends or not.

Also, much the rest of the world has for the past four decades been reducing corporate income tax rates and generally trying to design corporate tax systems that attract companies rather than drive them away. This includes lots of the high-tax, high-spending Western European countries that many proponents of Argument 1 tend to otherwise cite as examples of how to do economic policy right. For the U.S., the corporate tax code has almost certainly become a source of competitive disadvantage, and its outlier status makes it ever easier for corporate executives here to dismiss it as illegitimate.

Prohibition eventually lost so much legitimacy that it was repealed outright, although states continued to restrict alcohol sales to minors and more recently began to harshly punish drunk driving. A better fate for corporate taxes would be a more rational, internationally competitive U.S. tax code (HBS professor Mihir Desai described one reasonable approach in a 2012 HBR article), coupled with a more sensible rule on inversions.

Right now a U.S. corporation can shift its tax domicile overseas after a merger with a foreign company as long as its shareholders own less than 80% of the combined entity — or more than 25% of combined company’s employees, sales, and assets are in the foreign company’s country. The President’s FY 2015 budget and the “Stop Corporate Inversions Act of 2014” introduced earlier this year by Michigan’s bicameral Levin brothers would drop the shares percentage to 50%, which seems reasonable. The Levins’ bill would also ban inversions for any company that keeps its headquarters or more than 25% of its employees in the U.S. — which seems like it would perversely up the incentive for companies to move operations out of the country.

I’m willing to buy the argument, made recently by Sloan, that stopping the inversion wave is more pressing than reforming corporate taxes. But I don’t get the sense that passage of such legislation is imminent, and broader corporate tax reform certainly doesn’t seem to be on the way. Washington has so far remained as gridlocked on corporate taxes as ever. The issue isn’t (just) the usual partisan divide; there are substantial elements in both the Republican and Democratic parties in Washington that favor cutting corporate tax rates and rationalizing the corporate tax system — and the inversion debate crosses party lines as well. The biggest stumbling block is that, while corporate taxes may have lost legitimacy with CEOs and economics professors, they remain extremely popular with the electorate. Years of polling have shown that, if there’s one thing that Americans can agree on, it’s that corporations should pay more taxes. While there might be a way to sell voters on a corporate tax rate cut that’s accompanied by the elimination of lots of deductions and loopholes, any attempt to do the latter will be met with feverish lobbying by the affected corporations. And on inversions, which are kind of hard to understand, fear of lobbyists may outweigh fear of voters.

So this is an issue that, understandably, hardly anybody in elected office really wants to deal with. Yet it’s also an issue where continuing official inaction is likely to lead to a flood of corporate action that we’re all going to regret.

Do Not Split HR – At Least Not Ram Charan’s Way

Ram Charan’s recent column “It’s Time to Split HR” has created quite a stir. He argues that it’s the rare CHRO who can serve as a strategic leader for the CEO and also manage the internal concerns of the organization. Most CHROs, he says, can’t “relate HR to real-world business needs. They don’t know how key decisions are made, and they have great difficulty analyzing why people—or whole parts of the organization—aren’t meeting the business’s performance goals.“

While I have enormous respect for Ram’s wisdom, I believe CHROs have much to offer CEOs and can be better prepared to do so without splitting HR.

Much of Charan’s recent work has tilted towards organization and people (books on strategy execution, leadership pipeline, talent and advice on intensity, change, leadership traits, performance management, governance). I believe that Charan’s perspective reflects an increasing emphasis among business leaders on the organizational capabilities required to win. Charan has turned his attention to these organization dynamics in response to CEOs recognizing that technology, operations, access to financial capital, and even strategic positioning statements are less differentiating than their organization’s ability to respond to opportunities. As business leaders demand more of their organization, they look for counsel to create more competitive organizations, thus raising the bar on HR. Charan’s latest column actually affirms the value of HR to sustained competitiveness.

More is now expected of HR professionals. Charan (intentionally or not) lambasts the entire HR profession (“It’s time to say good bye to the Department of Human Resources”). This is both unfair and simplistic. It ignores what I call the 20-60-20 rule. In HR (or finance or IT), 20% of the professionals are exceptional, adding value that helps organizations move forward, 20% of HR folks are locked into a fixed mindset and lack either competence or commitment to deliver real value, and 60% are in the middle. It is easy and fair to critique the bottom 20%, but it is not fair to paint the entire profession with this same brush. I tend not to focus on either 20%. The top 20% are exceptional and don’t need help. They should be role models for others. Charan noted a few of these folks in his column. The bottom 20% won’t take help. But, the 60% seem, in my view, to be actively engaged in learning how to help their organizations improve. Sometimes they are stymied by their own lack of ability, but I find that often they are also limited by senior leaders who don’t appreciate the value they offer. I advocate teaching the 60% what they can do to deliver value even in difficult circumstances (working with non-supportive leaders or in difficult markets, for example).

As HR professionals engage with business leaders to deliver value, the conversation should not just be about talent. The top 20% today (and I hope more of the 60% tomorrow) focus on three things: talent, leadership, and capability, along with their attributes:

Talent: delivering competence (right people, right place, right time, right skills); commitment (engagement); and contribution (growth mindset, meaning, and well-being) of employees throughout the organization.

Leadership: ensuring leaders at all levels who think, feel, and act in ways that deliver sustainable market value to employees, customers, investors, and communities.

Capability: identifying the organization capabilities (called culture, system, process, resources, etc.) that enable organizations to win over time. These capabilities would vary depending on the strategy, but might include service, information (predictive analytics, metrics), innovation, collaboration, risk, efficiency, change (adaptability, flexibility), culture change, learning, strategic focus, etc.

I strongly believe that excellence in talent, leadership, and capability requires an outside-in not inside-out perspective. For talent, being outside-in means not being the employer of choice, but the employer of choice of employees customers would choose. It means that effective leadership is defined through the brand promise made to customers and the intangible leadership capital investors value. And that capability becomes defined as the identity of the firm in the mind of key customers. As I’ve suggested before, this outside-in view of HR complements current strategic HR perspectives.

Charan’s advocacy for a “talent” HR role actually limits the breadth of what HR can and should deliver. When HR professionals bring unique insights about talent, leadership, and capability to the senior management dialogue, they add enormous value. I suggest that HR professionals are better at delivering in each of these areas than line managers who get moved into HR roles—the path Charan recommends.

Charan’s recommendation for splitting HR into two groups raises two concerns. First, it offers a simplistic structural solution to the fundamental challenge of increasing HR’s value to the business. I am a little surprised that Charan, who is known for his integrated strategic approach to business, has reduced the HR challenge to a governance problem. Upgrading HR requires more rigorous redefinition of how HR can deliver value, how to develop HR professionals, and how to rethink the entire system of HR.

Second, advocating the separation of the HR function into two groups cannot be a blanket solution to HR governance. The structure of the HR department should be tied to the business structure (a centralized business should not have divided HR governance nor should a pure holding company). In diversified organizations HR departments should be run like professional services firms. This approach offers the benefits of centralization (efficiency, economy of scale) and decentralization (effectiveness, local responsiveness). In fact, many large diversified organizations have separated HR into three groups: the embedded HR generalists who work with business leaders on talent, leadership, and capabilities; centers of expertise that offer analytics and insights into HR knowledge domains; and service centers that do the administrative work of HR. All can be governed under the HR umbrella–just the way finance and accounting or marketing and sales work together.

I suggest a holistic approach to helping the middle 60%. This includes redefining the strategy (outside-in) and outcomes (talent, leadership, and capability) for HR, redesigning the organization (department structure), innovating HR practices (people, performance, information, and work), upgrading the competencies for HR professionals, and focusing HR analytics on decisions more than data. It is not easy to move a profession forward. The top 20% don’t always share their lessons in ways that teach others. The bottom 20% get too much attention. And, the vast middle gets discouraged when respected colleagues (unintentionally, I believe) belittle them and their efforts. We can do better than this.

Why Social Epidemics Sometimes Spread More Slowly in Collectivist Societies

Psychologists have always assumed that social trends spread more quickly in societies that emphasize people’s interdependence and de-emphasize individualism, but sometimes the opposite can happen. Sweden, a country whose culture emphasizes collectivism, was about a decade behind the U.S. (a highly individualistic society) in reaching a peak proportion of smokers in the population (30%). That’s because in collectivist societies, “social inertia” can inhibit the spread of socially contagious phenomena, the researchers say.

The Skills Leaders Need at Every Level

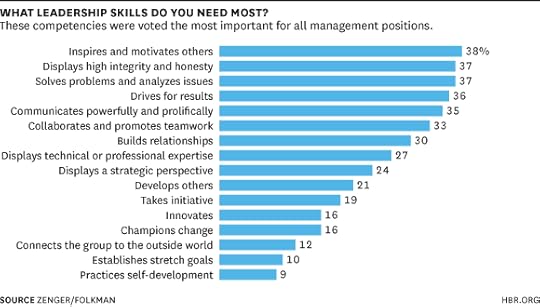

A few weeks ago, we were asked to analyze a competency model for leadership development that a client had created. Its was based on the idea that at different points in their development, potential leaders need to focus on excelling at different skills. For example, in their model they proposed that a lower level manager should focus on driving for results while top executives should focus on developing a strategic perspective.

Intuitively, this makes sense, based as it is on the assumption that once people develop a skill, they will continue to exercise it. But, interestingly, we don’t apply it in athletics; athletes continue to practice and develop the same skills throughout their careers. And as we thought about the excellent senior executives we have met, we observed that they are, in fact, all very focused on delivering results, and many of the best lower level managers are absolutely clear about strategy and vision. This got us to wondering: Are some skills less important for leaders at certain levels of the organization? Or is there a set of skills fundamental to every level?

To see, we compiled a dataset in which we asked 332,860 bosses, peers, and subordinates what skills have the greatest impact on a leader’s success in the position the respondents currently hold. Each respondent selected the top four competencies out of a list of 16 that we provided.We then compared the results for managers at different levels.

As you might expect, the skills people reported needing depended not only on their level in the organization but also on the job they held and their particular circumstances. But even so, there was a remarkable consistency in the data about which skills were perceived as most important in all four levels of the organization we measured. The same competencies were selected as most important for the supervisors, middle managers, and senior managers alike, and six out of the seven topped the list for top executives. Executives at every organizational level, our respondents reported, need a balance of these competencies. The other nine competencies included in the study were chosen only half as frequently as the top seven.

This suggests to us that as people move up the organization, the fundamental skills they need will not dramatically change. Still, our data further indicate, the relative importance of the seven skills does change to some degree as people move up. So, in the graph above the top seven competences are listed in order of importance, as it happens, for the supervisory group. With middle managers, problem solving moves ahead of everything else. Then for senior management, communicating powerfully and prolifically moves to the number two spot. Only for top executives does a new competency enter the mix, as the ability to develop a strategic perspective (which had been moving steadily up the lower ranks) moves into the number five position.

What to make of all this? From our analysis we conclude that there is some logic to focusing on distinct competencies at different stages of development. But, more fundamentally, it shows us that there are a set of skills that are critical to you throughout your career. And if you wait until you’re a top manager to develop strategic perspective, it will be too late. Lack of a strategic perspective, our research has further indicated, is considered a fatal flaw even when your current job does not require it. Your managers want to see you demonstrate that skill before they promote you.

So it is useful to ask yourself which competencies are most critical for you right now. But it’s also critical to ask yourself which competencies are going to be most critical in the future for the next level job. Demonstrating those skills in your current job provides evidence that you will be successful in the next job.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers