Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1389

July 29, 2014

Were OkCupid’s and Facebook’s Experiments Unethical?

It’s been an interesting month for online social science experiments, between Facebook’s research into emotional contagion and now OkCupid’s study of perceived compatibility. The two experiments had very different objectives, but both companies learned the same lesson: People get really upset about studies like this.

Problem is, that’s the wrong lesson.

According to a multitude of critics, the companies stepped over an ethical line by playing with emotions without asking users’ permission. The Facebook study showed that users who see more negative content are more likely to produce negative posts of their own. And OkCupid found that telling people — falsely — that they’re compatible is a good way to get them to converse more online.

Why was there such an outcry? True, both companies were manipulating users’ emotions, but people don’t seem to mind the daily emotional manipulation that companies engage in every day through marketing and product design. It’s hard to imagine a world in which companies didn’t try to influence our emotions.

What bothers people is the experimentation. To many people, experiments conjure images of twisted scientists. Businesses even shy away from the word “experiment.” In a recent conversation with a group of managers, I was told, “We don’t run experiments; we run A/B tests” — so named because customers are tested on their preferences for option A or B. The word “experiment” apparently needed a euphemism.

People fear that corporations have free rein to test whatever mad idea strikes them. Let’s make vegans fall in love with steak lovers! Let’s tell people they’ve been unfriended by their mothers! Where does it end? Will Facebook and OkCupid be in the next season of Orphan Black?

While Facebook and OkCupid won’t be creating clones anytime soon, there is a legitimate concern here. In academia, research involving human subjects is severely limited and carefully monitored. Each institution, in the U.S. at least, has an Institutional Review Board for just that purpose. Social science experiments typically must adhere to the following protocol: In lab settings, where subjects are recruited and brought into a room, research participants are informed that they’re taking part in an experiment (though in some fields, such as psychology, they’re routinely deceived about the experiment’s purpose).

Outside the lab, in what we call field experiments, it’s fairly common practice for research subjects not to be informed that they’re in an experiment. For example, my colleagues and I recently hired hundreds of employees of the online work platform oDesk and experimentally varied how much pay we offered in order to better understand the impact of wages on effort. We were able to show the IRB that the research presented no more than minimal risk to the subjects, that it wouldn’t infringe their rights or harm their welfare, and that we weren’t deceiving participants about the work involved. We also showed that if the participants knew it was an experiment, we wouldn’t be able to interpret the results. Hence, the IRB waived the informed-consent requirement.

Facebook’s experiment probably would have been approved by most IRBs, because the possible harm was minor and — importantly — because it wasn’t deceptive (all the posts shown to users were real). OkCupid’s is another story. Because the experiment involved telling users that their compatibility scores were high when they actually weren’t, it probably wouldn’t have gotten through many schools’ IRBs unless participants were asked for their consent.

Despite the element of deception, OkCupid cofounder Christian Rudder was refreshingly open and unapologetic about the dating site’s experiment. He described the company’s past experiments and practically dared users to take offense: “Guess what, everybody,” he wrote. “If you use the internet, you’re the subject of hundreds of experiments at any given time, on every site. That’s how websites work.”

He’s right, of course: Every website experiments on its users in one way or another.

Regardless of IRB considerations, companies should certainly adhere to the core principles of ethical research. But the real problem in corporate America isn’t too many experiments — it’s too few. Although the value of experimentation is self-evident, companies aren’t doing enough well-designed experiments. Not only are companies unwilling to conduct experiments that are aimed at increasing scientific knowledge, they’re reluctant even to pursue the narrower goal of understanding how customers react to their products.

The reason for the dearth of experimentation in corporations is the excruciating number of internal obstacles, many of which are based on knee-jerk reactions rather than careful deliberation. In most companies, you have to get approval from various operational functions, as well as legal and public relations teams, especially if the results are going to be made public. Often there’s a good deal of pushback: Will the public misinterpret the results? Will competitors learn too much about our secret sauce? Don’t we already know this without doing an experiment? Is this going to get in the way of my lunch plans? In addition to these kinds of barriers, there’s a pure know-how issue that makes real research difficult to pull off in corporate settings: Most people never learn how to run experiments.

Even when companies do run experiments, they often balk at allowing the results to be published. So the studies don’t go through the valuable peer-review process, and the findings don’t see the light of day. That’s a loss for other companies, for research as a whole, and even for the company that ran the experiment.

The biggest risk from the Facebook and inevitable OkCupid blowback is that companies will conclude that experiments are too risky and will be even more reluctant to act on opportunities to learn about human behavior or understand products’ effects on society.

It’s hard to overstate how much companies can learn from even the simplest experiments. Which advertisements work? Will customers look elsewhere if we raise prices? How do users interact with and rely on social media? Questions like these are often critical for a company’s bottom line. And the smart use of data and experiments to answer them allows companies to look less like Don Draper and more like Nate Silver — which (fashion aside) is a change for the better. Within the bounds of ethical principles, companies should embrace the experimental method and feed more of their hunches into transparent, published experiments with generalizable insights.

OkCupid’s Co-Founder Probably Wouldn’t Agree to the Experiments OkCupid Runs on Its Users

You may have heard that OkCupid sometimes lied about potential matches’ algorithmic compatibility for the sake of understanding its users. You may have also read its co-founder and president Christian Rudder’s explanation on OkCupid’s blog in which he dismisses concerns about the practice. “That’s how websites work,” he patronizingly tells us.

What you probably haven’t read yet is that Rudder himself would be reluctant to be a subject in one of these studies. In his forthcoming book Dataclysm: Who We Are When We Think No One’s Looking, which I read (a reviewer’s copy) for a September HBR article on privacy and data collection, Rudder writes that “Tech loves to push boundaries, and the boundaries keep giving. Software has become almost aggressively invasive.”

He also notes that he’s not really into it. Why?

“I myself know the value of privacy,” he writes. “That’s part of the reason I’m not a big social media user, frankly.”

That quote points to what marketers might call an authenticity problem. He sounds like a liquor baron who says, “I never touch the stuff.”

Rudder’s follow-up blog post reads like the book, actually. It has the same giddy enthusiasm (title: “We Experiment on Human Beings!”) and shows off the same irresistible correlations and trends he’s dug up in OkCupid data. The data can be fascinating, and the visualizations are good. I didn’t dislike his book, even though I mostly gave up on it, and on Rudder by the end. He clearly loves data science and has charted some neat stuff. But he’s also divorced from the world he’s analyzing. In fact he’s actively avoiding it. At various points in the book, he notes that in addition to avoiding social media, he’s never been on an online date, and “Tweeting embarrasses me.”

And on our decisions to cede our privacy, he writes “Not to confuse the issue here, but many people, men and women, trade on privacy when they walk out the door in the evening, giving it away, via a hemline or a snug fit, for attention.”

Passages like that leave you convinced that Rudder doesn’t understand privacy at all. He spends a few paragraphs explaining how he made his data anonymous (a good thing). But it reads as if he’s celebrating that, as if anonymity equals privacy. As if doing experiments on people without their consent, deceiving your customers, is just fine so long as it generates interesting results. “I never wanted to connect the data back to individuals, of course,” he writes. “My goal was to connect it back to everyone. That’s the value I see in the data and therefore in the privacy lost in its existence: what we can learn.”

Rudder seems to think that privacy is about the outputs: because he sanitizes data, and because he has a loftier goal, it’s fine to do whatever. We can see no one got hurt, so it must be okay. He writes: “The fundamental question in any discussion of privacy is the trade-off—what you get for losing it.” Note the verb there, lose, which is something that happens to you not something controlled by you.

That’s what he’s missing. Privacy is about the inputs. The better sentence would have been “The fundmental question in any discussion of privacy is whether or not you, the individual, have been given the choice to selectively reveal what you want about yourself.”

In fairness, in the book Rudder eventually does raise all of the important privacy issues surrounding data collection and hints at the insidious nature of what’s happening. He largely blames users’ “blasé” attitude for allowing it to happen. He’s not entirely wrong.

But raising issues and thinking about them critically are two different things, and he falls down on the latter. He floats regulation as a possible solution then half-heartedly dismisses it—“[it] will be outdated before the ink is dry.” Then he opts out of thinking too hard about the problem. “As far as balancing the potential good with the bad, I wish I could propose a way forward. But to be honest I don’t see a simple solution.” And if it’s not easy, why even try?

Should OkCupid be worried about a backlash? Probably not. When Rudder wrote his in-your-face blog post, he was probably thinking about something else he wrote in his book: “Whenever Facebook updates its Terms of Service to extend their reach deeper into our data, we rage in circles for a day, then are on the site the next, like so many provoked bees, who, finding no one to sting, have nowhere to go but back to the hive.”

Your move, consumers.

How the Internet of Things Changes Business Models

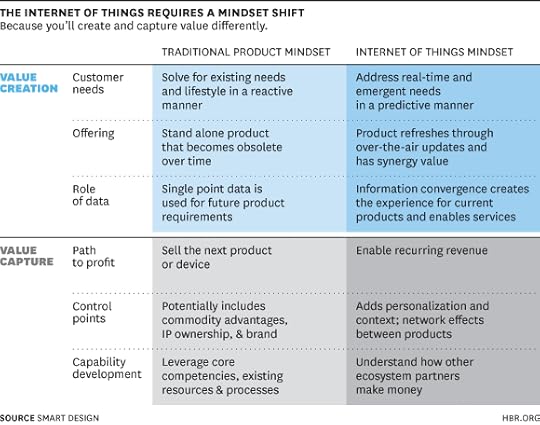

As the Internet of Things (IoT) spreads, the implications for business model innovation are huge. Filling out well-known frameworks and streamlining established business models won’t be enough. To take advantage of new, cloud-based opportunities, today’s companies will need to fundamentally rethink their orthodoxies about value creation and value capture.

Value creation, which involves performing activities that increase the value of a company’s offering and encourage customer willingness to pay, is the heart of any business model. In traditional product companies, creating value meant identifying enduring customer needs and manufacturing well-engineered solutions. Competition was largely feature-versus-feature warfare. And when feature innovation eventually proved to be too incremental, price competition would ensue, and products would become obsolete. Two hundred and fifty years after the start of the Industrial Revolution, this pattern of activity plays out every day, at your local big box electronics retailer or department store.

But in a connected world, products are no longer one-and-done. Thanks to over-the-air updates, new features and functionality can be pushed to the customer on a regular basis. The ability to track products in use makes it possible to respond to customer behavior. And of course, products can now be connected with other products, leading to new analytics and new services for more effective forecasting, process optimization, and customer service experiences. A variety of consumer products and services, from Nest thermostats to Philips Hue lightbulbs to If This Then That (IFTTT), highlight these new possibilities for IoT-based value creation.

Albert Shum, Partner Director of UX Design at Microsoft, notes: “Business models are about creating experiences of value. And with the IoT, you can really look at how the customer looks at an experience—from when I’m walking through a store, buying a product, and using it—and ultimately figure out what more can I do with it and what service can renew the experience and give it new life.” To foster a conversation about the potential implications of connected experiences for designers, technologists, and business people, Albert’s team at Microsoft recently released a short film documentary called “Connecting: Makers.”

Just like value creation, connecting to the cloud forces a new mindset around value capture, the monetization of customer value. At most product companies, value capture has been as simple as setting the right price to maximize profits from discrete product sales. Sometimes this is done creatively, as with the razor-and-blades model made famous by Gillette. Margins are maximized to the extent that companies leverage core capabilities in bringing products to market, and are able to establish control of key points in the value chain, for example regarding commodity costs, patents, or brand strength. Here are some ways to shift your thinking when it comes to both value creation and capture:

However, making money in the connected space is not limited to physical product sales; other revenue streams become possible after the initial product sale, including value-added services, subscriptions, and apps, which can easily exceed the initial purchase price. In a recent conversation, Renee DiResta, a Principal at O’Reilly AlphaTech Ventures, noted: “Things that generate recurring revenue are actually more appealing to venture capitalists. Otherwise, the business model is banking on the hope that prospective customers will be loyal and be compelled enough to come back to buy the second product.”

Options for control points also expand through the IoT. Customers can become “locked in” due to personalization and context gained through information gained over time, and network effects scale as more products join a platform. Equally important, firms’ efforts to develop their core capabilities change focus to emphasize growing partnerships, not always build internal capabilities—so that understanding how others in the ecosystem make money becomes important to long-term success. Zach Supalla, the CEO of Spark (an open source IoT platform), says, “With the IoT, you can’t think of a company in a vacuum. The market stack is deeper than traditional products; you need to think about how your company will monetize your product and how your product will allow others to generate and collect value, too.”

In his classic book Competitive Strategy, Michael Porter describes three generic strategies: differentiation, cost leadership, and focus. For some industries, those basic strategies still hold true today. But in industries that are becoming connected, differentiation, cost, and focus are no longer mutually exclusive; rather, they can be mutually reinforcing in creating and capturing value. If your company is an incumbent firm that built its kingdom through a traditional product-based business model, be concerned as your competition and disruption-minded start-ups take advantage of the IoT.

The Former CEO of Ogilvy & Mather on Personal Branding

Shelly Lazarus has been building brands at Ogilvy & Mather for more than 40 years. When she joined the agency in 1971, she was one of few women in the advertising field. Twenty-six years later, having steered successful branding efforts for clients such as IBM, Ford, American Express and Unilever, she was named its Chairman and CEO. What does this business trailblazer, Advertising Hall-of-Famer and current Board member of Merck, G.E. and Blackstone recommend to people who want to build their own brand? I recently sat down with Lazarus and an audience of senior professional women, to discuss personal, rather than corporate, marketing advice. In this condensed and edited interview, Lazarus shares her thoughts on what “brand” really means in a career context, and why simply being yourself may be the best strategy of all—for women or for men.

What can a personal brand do for your career, and what’s the best way to start building one?

Here’s the thing: I hate it when people talk about personal brand. Those words imply that people need to adopt identities that are artificial and plastic and packaged, when what actually works is authenticity. One of the fabulous things I’ve enjoyed about my career is collaborating with so many leaders across different industries and countries, and without exception the successful ones have been comfortable in their own skin. Resilience —the ability to hang in there when things are difficult—is critical in a career, and if you’re spending every hour of the day pretending to be someone you’re not, you’ll be exhausted and won’t have the energy needed to face your real work. On the flip side, if you’re genuinely excited about what you’re doing, and have that light in your eyes, it will attract other people to you, and motivate them.

How does the recommendation to “be yourself” hold true if you’re not certain you’ll be effective?

Expressing a point of view is always legitimate, and if you’re doing it because you’re genuinely passionate about a topic, I don’t think anyone will have a problem with that. If you’re valuable to the organization and advocate strongly for an idea, what’s the worst that can happen? Even if the project doesn’t move forward, you’re not going to get fired.

What you do need to pay attention to, however, is style —not just what you say, but how you say it. People tell me I smile a lot —but I’m strong. I express very clear and forceful opinions, but I try to do it nicely. You don’t have to be mean to be powerful, and you can do anything with charm.

How would you advise people who are nervous about putting themselves out there and making mistakes?

Early on in my career I was in my boss’s office and the media planner came in to his office and she starts literally running in circles. That’s not just a metaphor. She was going around like that because we were supposed present the media plan to a big client and the computer was down. My boss gets in front of her, grabs her by her shoulders and shakes her and says, “Karen, what do you think they’re going to do to you? Take away your children?” Regardless of the situation, if you’re really valuable and you do a great job, you’re not going to get fired. Somebody’s not going to think your idea is smart? So what? You won’t forget it for weeks, but they’ll forget it five minutes later. Take a chance. Just speak your mind. There’s no bad outcome.

Does a personal brand have to change as you become more senior in your company?

There’s a common misperception that you have to take on a new persona when you enter the leadership ranks: to become more restrained, intellectual, cerebral. But that doesn’t do anything for you. Brands exist in the hearts and minds of the people who use them, and if you suddenly try to switch them—which I’ve seen many corporations try to do —you alienate the customer. Whatever humility or generosity or warmth made me successful early in my career when talking to a brand-manager level client, I tried to keep when we were both promoted and sitting in corner offices.

When you think about people with strong personal brands, who comes to mind?

David Ogilvy, the founder of our agency, was one of the world’s great salesmen, and completely outrageous. He wore kilts to work. Once we were at a client dinner and he ordered five of those little jam jars you get with hotel breakfasts, plus a spoon. If you can’t be brilliant, he said, at least be memorable. Trust me: If you met David, you remembered.

What advice do you have for today’s aspiring leaders about being memorable within their own organizations?

Pick your words carefully— and say what you really mean. David had principles by which he led Ogilvy, and unlike with so many corporate mission statements, his are impossible to forget. Whereas other companies might say, “Politicians don’t do well here,” David said, “We abhor toadies.” Other leaders might tell their employees to respect the product’s end user; according to him, “the consumer isn’t a moron; she’s your wife.” Every so often during my tenure leading Ogilvy these hot stuff young copywriters would want to overhaul the principles, and inevitably they came back with a version that together we’d rip right up, because it had lost all of its passion and uniqueness and fervor. When you’re leading people towards something important, losing your authentic voice is the last thing you want to do.

Case Study: Should a Female Director “Tone It Down”?

Finally, Sarah thought.

J.P. Offutt, the CEO, had named a time when they could meet.

Sarah was a longtime director of the company that J.P. ran, a Florida-based shopping-center-development group, and she was devoted to both him and his firm.

But board meetings had been tense recently, and J.P. had grown distant.

In Sarah’s opinion, the problem was obvious: Sid Yerby, the CFO. Despite her repeated requests for comprehensive financial statements, he continued to come to board meetings with a mere two pages of analysis that lacked any explanation. How could she or any of the other directors provide fiscal oversight without access to details of the company’s operations or accounting? Increasingly, however, hers seemed to be the minority view, and she was starting to feel isolated.

Some months back, J.P. had told her privately that he appreciated her persistence with Sid. The young and inexperienced CEO confessed that he often felt uncomfortable asking tough questions of the CFO, an industry veteran who was 10 years his senior. It didn’t help that J.P.’s father, Bill Offutt, who had founded the company and remained its chairman, didn’t seem bothered by the lack of documentation.

Sarah, an experienced real estate consultant, had always been happy to help. But the clamor against her from Sid and the other board members was growing uncomfortably strong. In fact, one of her fellow directors had accused her of having a private agenda that included taking the CFO down a couple of pegs. Another said to her face that she talked too much, just like his teenage daughter. Outwardly Sarah balked at this, but inwardly she was intimidated, especially because she was the only woman on the board. Even Bill, who had recruited her as a director, praising her stick-to-itiveness and gumption, had commented that others considered her “pushy.” It was high time, she thought, that J.P. sprang to her defense.

Editor’s note: This fictionalized case study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Harvard Business Review, along with commentary from experts and readers. If you’d like your comment to be considered for publication, please be sure to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

The Previous Quarter

As Sid clicked through to a liquidity projection slide, Sarah allowed herself a small smile. It was a minor victory, but a victory nonetheless. Two weeks earlier, J.P. had pulled her aside and asked her to stop arguing with the CFO. Initially she was taken aback. Arguing? She was just asking questions. Besides, she’d been under the impression that J.P. wanted her to question and challenge Sid. Nevertheless, she decided to try a new approach: Before the board meeting she called Sid and suggested that his presentation include certain essential details, such as the liquidity projections.

Still, he had to know that the inclusion of a single additional slide wasn’t enough. After Sid finished, Sarah raised her hand. She could hear the sighs around the table. “Sid,” she said, “I want to commend you for the additional information you’ve provided. But as I mentioned when we spoke a few weeks ago, it would be helpful to have even more information. For example, how do our financial ratios compare with the rest of the industry’s? And what about best-, base-, and worst-case scenario projections?”

Everyone started talking at once. Sid turned to Bill with a shrug, as if to say, “You see what I have to deal with?” Bill quieted the room by tapping his pen on the table. “We simply can’t fight over every financial report. Everyone here is an experienced business leader,” he said, using the pen as a pointer. “Avery is the CEO of a trucking company, Louis runs a bank, et cetera. They’re very comfortable reading financial summaries, and they don’t want to waste their time getting into the weeds.”

“But it’s our fiduciary duty to get into the weeds,” Sarah said. “Even though we’ve had a steady rise in our stock price, we’ve been relying more and more on purchasing underperforming assets using floating-rate debt. We’re assuming that the assets will stabilize and we can refinance at lower rates, but that’s a big assumption, and the board deserves more detail about why that’s our strategy.”

Rather than address those issues, Bill ended the discussion and moved on. It burned Sarah up. Fine — she would be quiet for now, but that night she wrote J.P. a letter that pulled no punches, for the first time formally documenting her concerns about the company’s strategy and Sid’s reporting standards, which she felt were far too casual for a big real estate investment trust, or REIT. The letter also asked J.P. for a one-to-one meeting in the week after she came back from a vacation with her husband and their four children.

Sisterly Advice

Before leaving for vacation, Sarah had her monthly dinner with her sister Betsy, a biotech entrepreneur. Although they both juggled work and large families, they remained close and engaged in each other’s lives.

It was as Sarah waited for her sister at their favorite restaurant that she received the affirmative response from J.P. She was relieved he’d agreed to meet, but there was a nervous twinge in her gut that wouldn’t go away. The terseness of J.P.’s e-mail unsettled her.

As Sarah greeted Betsy, she tried but failed to wipe the worry off her face. “What’s wrong?” Betsy asked immediately.

“It’s that board I’m on — the real estate company.” Sarah exhaled loudly. “Did you know we’re now the second-biggest REIT in the country? We own hundreds of properties, and we’re making tons of money. But the management team still wants the company to function like the small family business it was years ago. I can’t tolerate that. And I especially can’t tolerate our CFO Sid Yerby’s casual approach to the numbers.”

“I know. You’ve talked about him,” Betsy said.

“He’s like an overconfident card shark who bets high on a pair of deuces. Nobody calls him on it except me. By the way, many of the times when I’ve grilled Sid over his numbers, it’s been because J.P. asked me to. J.P. once told me he couldn’t run the company without me. But now it seems like he’s giving me the cold shoulder and giving Sid free rein.”

“What exactly is Sid doing wrong?” Betsy asked.

“Well, back in 2011, we made a few big acquisitions that gave us a lot of great properties but also stuck us with billions in debt, most of which had to be financed with short-term paper. The company is now highly leveraged — much more so than any of our competitors. Sid says property values have stabilized, the consumer is back in the saddle, and there’s nothing to worry about. But what if we hit another downturn? No one else seems to be concerned about this.”

She sighed. “All the other directors hate it when I grill him. They think I have some private agenda. But I don’t, except the interests of the company.”

“In all your grilling, have you ever uncovered anything nefarious or illegal?” Betsy asked.

“No,” Sarah replied.

“Incompetent, boneheaded, sloppy? ”

“No, but — ”

“Misguided, rash, questionable?”

“Well, I do think many of his choices are questionable, especially around our leverage,” Sarah said.

“But he did get your company through the mortgage crisis and the recession in good shape, right?” Betsy countered.

“Yes.”

“Well, rightly or wrongly, that might be one reason why you don’t have a single ally on the board.”

In J.P.’s Office

Sarah and J.P. sat opposite each other on the short leather sofas in his office. He looked nervous.

“Sarah, you know my own capabilities are limited,” he began. “I don’t know everything there is to know about business, and I never will. And as I’ve said to you before, that’s why I can’t run this company without — ” he hesitated.

Sarah filled in the rest. “Without me. I know. And I appreciate that.”

“No — sorry. Without Sid.”

She stared at him, unsure what to say.

“Sarah, your intellect is very powerful,” he continued. “And your questioning, especially on financial matters, is very informed and insightful. What you have to say is always important.”

“But?”

“But Sid has expressed his frustration with the situation on the board, and in fact he’s prepared to tender his resignation.”

“Really?” This was exciting news, Sarah thought.

“He’ll stay if you, well, as he put it, ‘tone it down and back off.’”

Sarah was stunned. She had to exert considerable effort to bring herself back into the conversation. She realized then that J.P.’s expression showed more resolve than she was used to seeing in him. Was he truly giving her an ultimatum: Shut up or leave the board?

Question: How should Sarah respond to J.P.?

Please remember to include your full name, company or university affiliation, and e-mail address.

Ace the Group Interview

An interview with the board of directors is standard for the CEO, CFO, and nonprofit Executive Director hiring processes, but the group interview approach is becoming more common for many other positions. If you have a group interview in your future, it probably means that you are one of the top candidates for the job, but there are challenges that are specific to these sessions that can make them a tough hurdle to cross.

For one thing, group interviews are far less predictable than their individual counterparts. If you’re interviewing with one person, it’s relatively easy to develop a sense of comfort about what to expect from her; once you have many people in front of you it gets harder to know where they are all coming from and predict what they might ask. Furthermore, more people means that the session will feel more like an inquisition and less like an informal conversation. The dynamic between the interviewers can also present a challenge. There may be factions or disagreements among the interviewers that may play out in front of you. You should be prepared in case your interviewers compete for air time, interrupt each other–and you. Succeeding in this kind of dynamic setting requires preparation and some specific tactics during the session.

To prepare:

Do your own due diligence on the interviewers. If you’ve been working through a search firm, they will prepare you for the meeting, as will anyone who suggested you apply for the position. But do your own research as well: you will come up with actual personal information that you can use to help you break the ice or create affinity with individual interviewers. I’m the mother of twins, and you’d be surprised at the number of times I’ve used that fact to build rapport. If you have been referred to the role by someone in the group, find out from them what they dynamics of the group are: if there are different factions, and if so who is on each and what particularly volatile subjects might be.

Prepare a summary based on benefits. In individual interviews, you typically pick a specific interest area or two on which to focus for each interviewer. In a group interview, you need to round up all your important points and present them everyone at the same time. The best way to do this is to summarize the benefits you bring to the table. Make a list of the requirements that were expressed in the job description as well as any previous interviews you’ve had. Match those needs with your experience and attributes. Those are the benefits of hiring you. (Remember the sales training workshop you went to once that taught you to sell benefits, not features? Don’t just give them a quick history of your work life; those are your features.)

Once you are in the room:

Greet them individually. Don’t just sit right down in your chair and wait to be grilled. Walk around and introduce yourself to everyone individually and shake their hands. This helps to break up the inquisition dynamic. If your interviewers don’t have name cards, write down their names in the order in which they are sitting, so you can use their names when addressing them.

Build bridges. If you were referred for the position by a group member who represents a particular faction, don’t sit next to the person who referred you; instead, sit next to a leader of the opposition. Proximity always defuses conflict. Pay a lot of attention to her throughout the interview. It may be important to have a relationship with this person if you get the job. Start now.

Be friendly, but don’t be a wimp. The temptation in meetings like this one is to duck all controversy and make everyone happy at all times with your answers. This is more challenging the more people there are in the room, and moreover, it’s just not the right approach. Remember they are looking for a leader, so don’t hesitate to push back in your replies. You can always soften the pushback with a question, for example, “What do your clients say about your current marketing approach?” instead of, “It doesn’t look as if your current marketing approach is working.”

Manage the meeting. Think of yourself as the facilitator of the group. If one person can’t stop talking, it’s up to you to turn her off politely. If there is an interviewer who hasn’t had much to say, make a point of letting him into the conversation. Go around the room, if necessary, to make sure everyone has had a chance to be heard. They are likely looking for someone who will listen to everyone carefully and provide the structure for them all to move forward together, and this is your chance to show them you can do it.

Indeed, remember that you are evaluating whether you can be successful in this position if it is offered to you. The dynamic of this interview will continue to play itself out when you have the position and as such is an important indicator of whether you can get the organization aligned and moving in the same direction. On your way home, instead of focusing on how you did, think about how the group did and whether you feel that you can work well with them—that’s the key to your success.

Science Shows Why Marketers Are Right to Use Nostalgia

Nostalgia, by heightening feelings of connectedness, reduces people’s desire for money, says a team led by Jannine D. Lasaleta of the Grenoble School of Management in France. In one experiment, nostalgic feelings increased people’s willingness to pay for desired objects. In another, participants who were asked to draw pictures of coins drew them 10% smaller after writing about a nostalgic event. Inducing warm feelings about a cherished past could bring big benefits for those seeking to part consumers from their money, the researchers say.

What It Will Take to Fix HR

In the July/August issue of HBR, Ram Charan argues that the Chief Human Resources Officer (CHRO) role should be eliminated, with HR responsibilities funneled in two separate directions — administration, led by traditional HR-types, reporting to the CFO; and talent strategy, led by high-potential line managers, reporting to the corner office. While my colleague and I vehemently agree that HR’s status quo is an inhibitor to growth, it is with the same fervor that we disagree with Ram’s proposed solution.

Really? Break up a strategic function in response to underperformance in the wake of severe market disruptions? Put the most strategic pieces into the hands of up-and-comers passing through the leadership-development revolving door? What would the capital markets look like today if a similar tack had been taken when the CFO role was ripe for transformation?

CHROs are standing at essentially the same crossroads that CFOs were, beginning in the 1980’s. Back then, CFOs (inclusive of the role’s predecessor titles) were squarely focused on accounting, controls, and preparing financial and tax statements. Fast-forward to today and the corporate bean-counter of old has become the CEO’s closest partner in driving strategy — and increasingly a candidate for the top job. How did this happen and what can be gleaned from it to inform the transformation of the CHRO?

Let’s think about the realm of the CFO and how it’s changed. As growth became a competitive imperative, business leaders began seeing the firm as a system of investment rather than a system of production. Financial capital was recognized as the scarce resource and its shortage a significant constraint on growth. At the same time, alternative approaches to accessing capital and funding projects proliferated, forcing financial decision-making to become increasingly sophisticated. Those conditions elevated the work of the finance function to the point that, today, the CFO helps to set the course of business, advancing an organization’s growth and improving its competitive position by identifying and resolving key financial constraints. This transformation took time to play out and involved both displacements of incumbents operating in outdated modes and the emergence of new “feeder” roles for those aspiring to the C-suite. A glance backward reveals how radically firms’ expectations have shifted in regard to the CFO’s breadth of background and the caliber of talent the position attracts. Baseline financial skills are still essential, but international experience, industry knowledge, investor relations acumen, technology expertise, and strategic prowess are now just as much part of the package.

Now compare that to the context and condition of today’s CHRO role. These days, the scarcity impeding firms’ growth is not of capital — it’s of talent. Nearly 40 percent of the 312 CFOs and other executives participating in Deloitte’s 2013 Global Finance Talent Survey said they are either “barely able” or “unable” to meet the demand for the talent required to run their organizations. And HR’s credibility deficit doesn’t help the matter. A recent survey of CEOs reveals that HR is overwhelmingly viewed as the least agile function. In our own conversations with CFOs we consistently hear that their attempts to work strategically with HR are the most trying. Business leaders concur, with nearly 50 percent reporting that HR is not ready to lead. Even HR itself agrees. In a March 2014 global survey, HR and talent executives graded themselves a C-minus for overall performance, citing a large capability shortfall, with 77 percent of respondents ranking the need to re-skill the HR function among the top quartile of their priorities.

While we disagree with Charan’s solution, we think he’s on to something when he asserts that the best CHROs have line and/or operational business experience.

Lynanne Kunkel, VP-Global Talent Development and HR-Asia for Whirlpool, is a case in point. After earning a degree in chemical engineering and spending eleven years in production roles at Procter & Gamble, Lynanne was drawn to P&G HR where she spent the next ten years in various roles, before moving over to Whirlpool HR four years ago. What Kunkel is particularly known for is bringing a cross-functional perspective to talent strategy at the consumer products companies she serves. In addition, she believes that a few noted CHROs elsewhere are beginning to set the standard and emerge as top-notch leaders within their respective organizations. “There’s a flaw in the perception that the only thing HR is good for is administration. HR strategy is an expertise that takes years to fully develop.”

The cutting-edge HR leaders we’ve met, like Kunkel, are thinking more boldly and blurring the experience line with a fresh understanding of talent. Couple that with comprehensive functional expertise and soon we’ll have a generation of CHROs that consistently brings and activates strategic, holistic perspectives. What will it take to accelerate the shift within HR and recalibrate the role of the CHRO? We offer three pieces of advice.

Focus most on where strategic value is created. In the early 1980’s, sixty percent of corporate value creation emanated from the optimization of tangible assets. Today, we live in an era where eight-five percent of value creation stems from brand, intellectual property, and people — all intangible assets. Delivering HR-related operational, compliance, and administrative tasks with distinction is important, but let’s be clear that doing so is table stakes. The CHRO must step up to the implications of the new world of work.

Recalibrate and reskill HR to ensure its relevancy. Kunkel says that “while ‘good with people’ may have been the mantra for those attracted to the field in the past, the new mantra should center around the effective use of people to effect intended business outcomes.” Relatedly, organizations need to be deliberate in the design and implementation of development programs aimed at helping HR professionals acquire and hone an increasingly wide range of sophisticated skills, not only in talent areas but also in understanding the dynamics of how the business works, makes money, and competes.

Bring on the quants. For the CFO, analytics is a native language. Beth Axelrod, CHRO for eBay and someone who pivoted from consulting on strategy (as a principal at McKinsey & Company) to running an HR function, acknowledges that HR leaders have traditionally set their agendas based on qualitative metrics and shied away from quantitative analytical tools. That needs to change. Google is probably the best-known case of a company that uses analytics to inform a slew of daily HR transactions and interactions. Its managers use data to determine everything from whom to hire and promote to how much to pay them and what benefits are most valued, all segmented by a variety of contextual attributes. According to Prasad Setty, Vice President of People Analytics at Google, their goal is to have all people decisions informed by data. “We want people, no algorithms, to make people decisions, but we want the decision-makers to make decisions informed by data and analytics.” Using analytics to drive, design, defend, and activate a growth-oriented agenda will bring newfound credibility to HR leaders, and will be the hallmark of the great ones.

Rethink the division of labor. Bifurcating leadership between those who focus on what needs to get done and those who focus on how it gets done is an effective means for HR organizations to step up to the demands of today’s talent marketplace and growth challenges. Instituting an HR chief operating officer (COO) role, charged with optimizing how HR services are delivered is an emerging trend. The COO has a clear mandate to drive the design, development and implementation of HR services—optimizing operations while ensuring compliance across HR disciplines. Not only does this role free up the CHRO to focus on strategy and the larger talent agenda, thereby eliminating growth constraints, but it also preserves the crucial cohesiveness of the HR functi0n overall.

* * * * * * *

So, kudos to Charan for starting the conversation. The problem to which he is responding is real; indeed, as CEOs turn their thoughts to growth again, many will find the gap between the need for talent and the CHRO’s ability to deliver it greater than ever before. Success demands a far more diverse set of experiences and skills. But, as with CFOs before them, the solution resides in CHROs and the teams that support them. Just as financial management became increasingly sophisticated, so can talent management. CHROs can step up to meet this challenge — and they must, or someone else will step in to do it for them.

July 28, 2014

The Cardinal Sins of Innovation Policy

It happens every time there’s a big announcement about a national or regional innovation policy that will lead us into the future: We are presented with schemes to strengthen intellectual property rights, enlarge the pool of risk financing, and upgrade the universities while pushing them to collaborate more with industry. If we are truly lucky, we are told about a new science park to be built just around the corner.

There is only one question that is never asked or answered: Why?

Why should a specific place — a region, a city, or even a country — want to have an innovation policy?

This is a nonsensical question, you might argue. It is perfectly clear why: Innovation is the main engine of sustained economic growth; therefore, if you want to ensure a vibrant economy you must excel in innovation.

This, sadly, misses the main difference between innovation policies and economic growth policies.

The aim of growth policies is to entice people or companies pursuing specific, well-developed activities to move to your locale or create businesses there. For example, when Singapore decided to bolster its economy by developing its information and communication industries, it created detailed plans aimed at products such as hard drives. Because the skills and capital equipment needed for these products were well understood, Singapore could strategically allocate resources to achieve its goals. Not only did Singapore achieve rapid economic development; it also was able to upgrade its economic infrastructure so that it could repeat the strategy in newer, more-sophisticated tech fields.

The aim of innovation policies, by contrast, is to foster the development of technologies that don’t yet exist and whose business models and markets are unknowable. Organizations capable of inventing these technologies must be attracted or built, and the result of their labors must be channeled into economic growth. That means we’re not talking about a process of long-term planning but one of continuous experimentation. Policy makers need to rapidly come up with new initiatives, kill those that don’t work, scale up those that do, and then, as a new industry grows, keep changing the incentives in a co-evolutionary process in order to keep pace with the industry’s dynamic needs and capabilities.

Israel is a case in point. In 1968, when Israel decided to build a science-based economy (the concept of high tech didn’t yet exist), there were only 886 R&D workers in Israel’s civilian sector and the country had an R&D intensity (the ratio of R&D investment to GDP) of 1%, the second-lowest in the OECD. Policy makers’ vision was not of specific industries but of an economy whose competitive advantage would be based on continuous invention of products to be sold around the world.

Over the course of more than 40 years of policy experimentation, the office of the chief scientist in the Ministry of Trade and Industry has aided in the creation and stimulation of companies capable of carrying out such invention. Officials identified bottlenecks as they arose and developed policies to relieve them. In the mid-1970s, for example, policy makers realized that entrepreneurs in a mostly poor, quasi-social-democratic society (as Israel was then) might not have the knowledge to develop, sell, and service products for the American market, so they created the Bi-national R&D foundation (BIRD) to finance the joint development of new products by American and Israeli companies, with the U.S. firms focusing on product definition, sales, and service, and the Israeli firms on R&D. Then, in the early 1990s, when Israel already had 4,000 companies with products and revenues but no financiers willing to invest in scaling them up, officials created the Yozma program to kick-start the Israeli VC industry by infusing it with foreign know-how and connections to NASDAQ.

No one in 1968’s Israel knew what technologies and innovations would allow Israeli companies to succeed in 2014. No one even dreamed that a new form of finance, called venture capital, which was taking it first steps in the United States, would prove crucial in changing the Israeli financial environment 30 years later. However, the creators of Israel’s innovation policies had a clear vision of the economy they wanted to develop, were very willing to tweak this vision and their actions to fit the evolving reality, and had a deep commitment to develop a thriving private industry, knowing that their own status and importance would diminish as the industry grew.

Over the past 40 years, each and every case of very successful economic growth based on rapid innovation has been rooted in policy makers’ clear vision of developing an innovation-based economy.

Thus the importance of the “why” question. You need to understand where you are, and where you want to be, in order to know which best practices to apply, where you need to experiment, and when you need to change policy as the industry evolves. If you don’t have a goal, and you are not sure where you are, then you will get nowhere in particular. Applying all the best practices approved by the world’s most prestigious consultancies to reach goals such as patent numbers and R&D intensity doesn’t show that you are an innovation leader. It shows only that yours is a risk-averse society enjoying too much capital.

Innovation needs risk taking and grand visions. The willingness to face multiple failures and undertake repeated experimentation to reach a vision is what separates those who succeed from those who do not.

It is a cardinal sin of innovation policy not to have a vision. It is a second cardinal sin not to be flexible and experimental in turning this vision into reality.

Promoting the Non-Obvious Candidate

Conventional talent-management systems emphasize the need to give high performers appropriate experiences to help them ascend to more senior levels of management. Companies define career paths accordingly and carefully map, often in a linear fashion, the various roles one has to fill to reach higher management ranks.

However, in addition to grooming obvious high performers who are accomplished in a particular domain, talent-management systems should also deliberately look at non-obvious candidates. They are high performers in other domains who do not automatically fit the bill. This may be because they do not have the expertise or experience typically viewed as relevant for the job. But they do have, say, strong leadership skills or a different set of experiences that may be useful in a wider context.

Roles and contexts increasingly call for improvisation as opposed to experience, or resourcefulness as opposed to resources. So bringing in someone who will have a tendency to look at things differently makes great sense.

Placed in leadership positions, such candidates can redefine outcomes for the better. The benefits are often unexpected and interesting. Here are some examples that we’ve seen at GE:

An exceptionally talented financial controller was moved to head IT and in just a year was able to re-energize the organization. Her strength as a leader helped her to refresh talent, refocus the function’s purpose, and allow IT to reinvent itself as a major strategic partner for the company.

The legal counsel of a business was made a business leader with a substantive commercial focus. His negotiation skills, ability to prioritize, and ability to drive much-needed change allowed the business to recover strongly from a tough patch.

A commercial leader in financial services moved over to a health care business, bringing with her the ability to structure deals and work closely with C-suite executives. Her multi-dimensional perspective and consultative, solution-based approach were extremely well received by the health care business’ customers.

Success in identifying such non-obvious candidates requires HR to focus on strong leadership competencies such as mobilizing change, decisiveness, building teams, vision, and communicating in a compelling fashion.

For the individual, the stretch is radical, not incremental. At GE we believe that most growth happens when an employee shifts into an unfamiliar role and has to exercise all his or her faculties to figure out the new equation and drive change and growth.

Our challenge is to apply this principle across a range of contexts; constant experimentation ensures a vibrant talent pool. Taking bets on non-obvious talent is an art and comes with some risks. For instance, in critical situations, it is not sufficient to consider the non-obvious candidate without first making sure others on the team possess the necessary expertise to provide balance. In addition, pairing the candidate with a manager who is a strong mentor and coach capable of providing air cover as well as guidance is important. Finally, some extra preparation via a bridge role can help candidates more readily transition to their longer-term assignments.

At GE, we have used “integration leader” (of an acquisition) and Six Sigma Black Belt roles to broaden individuals at the mid-management level so they can better adapt to future opportunities. For instance, someone overseeing the integration of a newly acquired company can only be successful if he or she can influence others, empathize with people at the acquired company, and take a broad view of the business, and has strong project-management skills. The HR system for developing a pipeline of talent should be carefully constructed to put individuals in roles like these to broaden their leadership competencies.

When companies bemoan the talent shortage, they often do so because they have not thought about talent in a broader, more holistic way. We need leaders who can face different contexts and situations and handle different roles. By creating a variety of opportunities for leaders to grow, companies will be better able to prepare their talent for the challenges of a fast-moving world.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers