Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1390

July 28, 2014

Why No One Gets Away with Trash Talk Anymore

This summer, a milestone crept up on me—I realized it’s been twenty-five years since I began my career as a professor. So naturally, I’ve spent some time reflecting on how my choice of profession has worked out. I spend most of my classroom time with executives who are there because they are unhappy with where they are – or they at least understand they won’t be satisfied for long. Their hope is that whatever we do together in class will help them find something they’ll find more fulfilling. How thankful I am that I’ve never had to wrestle with that.

And how grateful I should be to an early mentor whose advice, I would say, led to my good fortune. I began my career at Louisiana State University in August of 1989. The department chair had worked hard to hire a cohort of five young faculty members that could help shore up a department that had suffered from attrition. As newly minted Ph.D.s, what we lacked in wisdom we compounded with inexperience. The chairman had his hands full.

At some point during that first fall, I was walking across campus with him for lunch and I recall sharing a frustration. I don’t recall the precise source of it, but I know it led me to want to call someone out for what I felt was a grievous offense of one sort or another. Though I can’t remember the foul, I do remember his advice. He told me, “You need to remember that this is a small field and you are going to have a long career.” There hasn’t been a month across the twenty-five years since in which that simple piece of advice hasn’t helped me frame the way I should respond to a colleague, a student, or an administrator.

When my mentor made his observation, he was speaking quite particularly about the profession he and I shared. Ours was a small field – there are only so many business schools and only so many professors – and, because it is a good gig, very few people are in any rush to leave. Make an enemy, and you will keep encountering that enemy for a long time. Soil your reputation, and you will find it next to impossible to make a fresh start.

But it occurs to me that what was true of our world a quarter century ago is true much more generally today. Technology has now made his advice relevant to virtually every person beginning a career. Now, no matter what your profession is and no matter where you practice it, you work in what is essentially a small field.

Certainly, those of us participating in social media are proactively making our reputation knowable to a much wider audience than ever before – with implications we might not anticipate. But even if we personally aren’t contributing, others are on our behalf. Faculty, as an example, are subject to ratemyprofessor.com (where rating criteria include student evaluations even of a professor’s “hotness”). All sorts of other professions deal with similarly candid and arbitrary reviews on sites like yelp.com.

We all know that this explosion of information is a genie that is not going back in its bottle. So, for those of you just embarking on your careers, look around you: the people around you will be your companions on a long journey. Manage your interactions with them accordingly.

And for those of you who are already well down the road and perhaps, along the way, have burned bridges, raised hackles, made enemies – well, do what you can to get those relationships on a better, more professional footing. Odds are that the person you’ve alienated will still be part of your field many years from now. And you’re in for a long career.

5 Things Digital CMOs Do Better

If you’re a mid- or late-career marketer, chances are your job today is mostly unrecognizable from what you signed on for. Perhaps no other business function has changed as dramatically over the past decade.

Why? Following a silent coup, the coronation is complete: the customer is king. With an abundance of information and choice, customers now guide their own self-directed decision journey as they traverse connected experiences that blur the lines between physical and virtual and scramble marketers’ signals for targeting.

Many marketers are left behind, simply tuned in to the wrong frequencies. In response, capturing the right data has become the key capability in finding and engaging audiences. But data, alone, isn’t enough; search and social marketing, for example, are content hungry disciplines. Marketers must also become publishers.

For marketing leaders, this has forced some serious soul searching on how to meet these challenges. Last April, I wrote “The Rise of the Digital CMO” to lend some perspective to this exercise. Subsequently, Gartner turned this into an ongoing research series designed to identify the patterns and exemplars behind the chief marketing officer (CMO) transformation — in effect, what digital CMOs do differently and what they look like incarnate. We found that digital CMOs do the following things better than their peers.

1. Shift from finding customers to getting found

The best digital CMOs don’t just shout from the hilltops, demanding attention on their terms. They orchestrate content marketing tactics that situate their brands at the moments that matter to their audiences. They do this by publishing brand-aligned, but audience-centric content that inspires, delights and, most importantly, engages customers on a self-directed decision journey where earned and owned often trump paid.

Hubspot CMO Mike Volpe is an exemplar of this pattern. He and his team publish a daily diet of blog posts, ebooks, infographics, videos and other content that lend insight to the digital marketing discipline. In doing so, Hubspot has become a go-to destination for insight on this topic. American Express does this, too, with its Open Forum site, which publishes editorial-style content for managers and operators of small and mid-sized businesses. Both of these are examples of brands that look and act like publishers, not carnival barkers.

But, as Hubspot’s Volpe says, it’s rarely just one thing alone that works well — it’s the right blend of activities. Inbound is about grassroots experimentation. Without proper measurement, these varied activities can turn into a fragmented mess.

Today, customers are inundated by pleas for their attention. As a marketer, the onus is on you to meet these customers on their terms with something of extraordinary value. That’s how your brand gets found.

2. Shelve the commercial pitch in favor of authentic storytelling

Digital CMOs have moved well beyond better-faster-cheaper; problem-solution-impact; features, feeds and speeds; and other self-referential brand-forward conceits, which are now rejected by audiences like a foreign body in the bloodstream. Instead, they tell stories — and, most importantly, they find others to tell stories for them.

These stories often follow the traditional narrative arc of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution. These stories are told with images, video and data. They inspire. They enlighten. They amuse.

Tami Cannizzaro is a brand storyteller. As IBM’s VP of marketing for social business, Tami leads a team that uses IBM’s celebrated “Smarter Planet” theme as the baseline for selling software. She says, “We’re not selling software, we’re building a smarter planet.” Nike marketing doesn’t sell footwear so much as it sells an aspirational point of view. Nike tells stories that ask audiences to reach for their personal best. National Football League franchise Atlanta Falcons’ CMO Jim Smith asks fans to “Rise Up”—and they do. To sell carbonated beverages, Coca-Cola tells stories designed to inspire nostalgia and happiness. More importantly, they ask consumers to tell their story on their behalf by cultivating user-generated content.

According to IBM’s Cannizzaro, today, people’s perceptions of the IBM brand are more likely to be formed by their community, not the message coming from IBM. The best digital CMOs now get this intuitively.

3. Break through silos to erase sea ms between channels and experiences

Digital CMOs recognize that customers are channel-blind. Channels, after all, are an artificial construct designed, first, to support corporate goals and organizational structures; and, second, to support the needs of customers. Today, customers expect the inverse: brand interactions that hide the seams between channels, where stories, experiences and services serve their needs first and the brand’s second.

Sharon Osen, SVP of global marketing at Swiss luxury beauty brand La Prairie starts with the customer, developing customer archetypes and personas that guide the design of multichannel experience that deliver on real customer needs. This begins with a deep understanding of customer habits and preferences, and how La Prairie can add value in their daily lives. Beauty retailer Sephora blends in-store and mobile channels to create ensemble experiences that make shopping easier and more engaging.

But La Prairie’s Osen makes it clear that the goal isn’t transformation for its own sake. She says it’s about enhancing brand experiences customers have come to expect with new digital extensions.

4. Use data to target precisely and measure relentlessly

Digital CMOs have learned to “close the loop,” turning their marketing efforts into a data-centric, performance-driven discipline. Here, the goal is to trace the thread from investments to outcomes, directly attributing marketing dollars with business outcomes. These CMOs use first- and third-party data to target contextually relevant offers and experiences guided by predictive analytics and algorithms that learn and adapt as customers traverse a meandering purchase path. These marketers then close the loop by combining this data-driven targeting with a process for continuous measurement. The result is a performance-driven discipline where marketing investments can be optimized to highest yield.

eBay’s CMO Richelle Parham is an example of a performance marketer. Her company collects more than 50 petabytes of data a day that it can use to target offers and experiences. For example, products that were browsed but not purchased become an opportunity for remarketing and the insight for collaborative filters in the form of recommendations that aid — and guide — customers’ decision making.

But, Parham warns, if this sort of personalization is handled clumsily, it can be intrusive. She’s right. Personalization can cross the line to creepy. Her advice is to balance head and heart: “In the end, we’re selling to human beings. To drive behavior change, we need to understand who the customers are and what they care about.”

5. Experiment aggressively, and challenge business model assumptions

Digital CMOs are agile marketers who embrace the mantra “test and fail to learn and scale.” Gartner finds that, today, 83% of enterprise marketing organizations have an innovation budget that reflects, on average, 9.4% of marketing spend. What do they use this for? Exploration. Experimentation. Learning by doing in recognition of the fact that sustainable competitive advantage is a quaint vestige of another time. These CMOs seek to create pipelines of innovations that they test and validate in rapid succession.

Delta Airlines, for example, has applied this technique to its websites, kiosks, in-flight Wi-Fi and entertainment, resulting in what it describes as a holistic set of touchpoints that inform the customers’ opinion about the brand. Here, a series of continuous experiments guide innovations that improve customer experience. The results? A 20-second reduction in kiosk check-in times, a substantial increase in check-ins via digital channels and improvements in overall customer satisfaction and brand sentiment.

But digital CMOs can’t go it alone. Digital CMOs need to hire the right people to lead and execute. As my colleague Laura McLellan and Scott Brinker wrote in their July-August 2014 Harvard Business Review article “The Rise of the Chief Marketing Technologist,” Gartner finds that 81% of enterprises have a chief marketing officer in place today, up from 70% last year. Seventy-seven percent have a chief customer officer as the primary advocate for the customer and final arbiter on customer experience. Forty-eight percent of the time, this role reports into the CMO, which supports yet another finding: the CMO is on the rise in strategic importance.

Other roles to watch: data architects, corporate journalists, data storytellers and chief content officers. They are all emerging to fill the gaps that stand between marketing from a decade ago and marketing for today.

A year later, digital CMOs are still on the rise. Only now, their secrets are coming into focus.

Why It’s Fair to Save a Parking Spot – For a Price

Tech start-up Haystack has developed an innovative – and controversial — solution to the stressful challenge of finding an open parking meter in congested areas. This smartphone app allows those leaving a parking space to alert other Haystack users in the area of their “about-to-be” open spot. To secure this meter (i.e., have the parked car driver wait until they arrive), users pay a fee of $3 (75 cents goes to Haystack while the incumbent “parker” pockets $2.25). Not surprisingly, Haystack has stirred up controversy amongst city officials, particularly in Boston, as well as drivers.

We explored these and other questions with pricing strategy author and consultant Rafi Mohammed. An edited version of our conversation is below.

First off: From a pricing perspective, is Haystack a good idea?

Absolutely! Haystack provides a solution to a key market failure in popular parking areas: meter prices are too cheap, which results in excess demand.

Start-ups like Uber and Haystack seem to be profiting by capitalizing on pricing inefficiencies like the one you just mentioned. Is this an emerging trend?

A great point that’s spot on. It just doesn’t make sense, for instance, to charge the same price for taxi cabs all of the time. Uber is brilliant in charging higher prices during peak periods (which incentivizes more drivers to provide service, thus increasing supply) as well as lowering prices during slack periods to generate more demand. Technology allows Uber to strategically flex prices and just as importantly, inform its customers of the current price. Customers are better served by this innovative pricing.

Parking meters are notoriously underpriced. A private for-profit garage in downtown Boston, for example, charges $12 for the first hour and then scales rates up to $32 for 24 hours. Meanwhile, public parking meters located directly in front of this garage run $1.25 an hour. As a result, drivers seeking a meter circle around (…and around) until they “luck out” by getting a below-market priced parking spot. Haystack is simply providing an arbitrage solution to a market failure created by poor city regulation.

But is this fair?

Is it ok, for a fee of $2.25, to “save” a parking space that you’ve paid for? What about saving a space for a family member or friend at no charge? These answers to these questions are really subjective. I will point out, however, that it’s axiomatic for a secondary resale market to emerge for any product that is priced below-market. Examples of this are in-demand sporting or music events that are routinely resold at higher prices through the scalper market.

The bigger question is whether meter rates should be so low that it incentivizes people to drive into the center of town (instead of taking public transportation) and then incur the time, frustration, and extra gas to find a cheap parking spot. Don’t even get me started on the wasteful pollution generated throughout this process!

In other words, though, is it a right of all citizens to have access, albeit inefficient access, to rock-bottom priced parking? I don’t think so – I vote for jacking up meter prices and investing in public transportation improvements.

And when you think about it, Haystack represents an incredible value to parking spot seekers. A $3 fee secures, for instance, $1.25 an hour parking in Boston instead of paying $12 at a garage. And then, if a driver uses Haystack to “re-sell” their space, they’ll reap $2.25. Thus, a net price of 75 cents enables drivers to save a bundle – seems like a bargain to me. Perhaps Haystack should boost its prices!

So what should local governments do about Haystack?

Officials, for instance those in Boston, need to stop being so status quo and allow technology to better serve their residents. Haystack exists because city officials have done a poor job of pricing parking spaces. Instead of needlessly obsessing on Haystack, cities should start dynamically pricing parking meters based on demand: increase rates during peak times and conversely, discount during periods of low demand.

San Francisco, for instance, is currently dynamically pricing parking spots. Meter rates in pilot neighborhood blocks are being varied based on demand with the goal of at least one space always being available. That’s a much better solution than complaining about a start-up that actually solves a major problem.

Don’t Try to Read Your Employees’ Minds

Albert Einstein once observed, “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” I think of this quote often when observing executives with a “little knowledge” of emotional intelligence (also called “EQ”).

Don’t get me wrong; the beneficial insights and managerial advances derived from research on emotional intelligence have been game changing. But appreciating a powerful concept is not the same as understanding it well enough to use it productively. Sometimes, “a little knowledge” about EQ abets the delusion that you know people better than you actually do.

Consider the case of Vernon (not his real name), whose modus operandi was to find a fault in a subordinate and then turn it into a clinical diagnosis. Detail-oriented people were labeled “OCD” while those whose attention wandered in dull meetings had “ADHD.” His “corrective feedback” thus rarely focused on behaviors, but instead came across as a personal attack, and his employees felt bullied – hence his referral to work with me.

While we were working together, one member of his group, James, missed several deadlines – and was often seen scooting out of the office at 4:45. Yet when asked to explain the missed deadlines, James explained that it was teammates who hadn’t held up their end of the bargain, causing his own work to be delayed.

Vernon, who considers himself an excellent judge of character, looked at this available evidence and vented to me that James had a “corner-cutting personality,” was “lazy” and “didn’t take responsibility.”

The problem? It’s not that Vernon isn’t a perceptive person with an intuitive understanding of people; indeed, he’s typically very insightful, and when he wants to be, he can be extremely charming. The problem is that he simply has no way to evaluate whether his analysis about James is accurate. All he can observe is James’s behaviors, not his intentions. (For instance, maybe James was leaving early to care for a sick relative; maybe he was signing on late at night, finishing his work remotely; maybe his coworkers really did torpedo his best efforts.)

Psychologists have long discussed a phenomenon known as “behavior engulfing the field” which describes how we infer that others’ actions reflect that person’s true “inner self,” belief system, and personality. Eg, when someone loses an important document, we say they’re disorganized. When they show up late, it’s because they’re inconsiderate. (Importantly, we give ourselves exceptions to this all the time – when we’re late, it’s because we got stuck in traffic.) Psychologist E. E. Jones did a series of studies in the 1960s to prove how robust this phenomenon is. In one study, a group of students read essays opposing the Fidel Castro and another group read essays endorsing him, and were asked to evaluate the opinions of the writers. Even when the researchers told the readers that the essay-writers had been assigned to take a pro or anti view, the readers still believed the students who wrote pro-Castro essays actually supported him.

So, knowing that we are all subject to such biases, how should Vernon respond to James? By embracing (and applying) one of psychoanalyst Carl G. Jung’s guiding principles: “Through pride we are ever deceiving ourselves. But deep down below the surface of the average conscience a still, small voice says to us, something is out of tune.”

If you feel that something is amiss in someone else’s actions, purge yourself of biases toward him or her prior to expressing what you think. Then, when giving your feedback, follow these two bits of advice to avoid letting a little knowledge of EQ cause you to do more harm than good:

Keep it simple. Leadership legend Winston Churchill observed, “Broadly speaking, the short words are the best, and the old words best of all.” My suggestion to Vernon was to say, simply, “I’m perplexed by what looks to be a pattern of cutting corners – missed deadlines, and leaving early. Is there something else going on?” After that, listen to James’ commentary. If plausible, give James a Mulligan; if not, put him on notice.

Show empathy. Consider the case of Bill Clinton; sure, he’s seen by many as having more than his fair share of psychological “issues.” Never, however, was he accused of failing to charm, ingratiate, and exploit every possible bit of EQ at his disposal to win over a person or a crowd. His secret is empathy. Remember “I feel your pain…”? Who cares if, given how diversified the audience he said it to was, absurd. Expressing empathy in a self-effacing way is the key to mastering EQ. If you tell someone, “You know, you got an issue that calls for an attitude adjustment,” you’ll never connect with them. Even if you are correct, the other person will dislike you for being insensitive. Say, “I sense you have been out of sorts for some time,” and that person will embrace you.

And to really insure that you never use your little knowledge about EQ in a maladaptive way, take a page from comedian Dennis Miller’s book, Rants. In it, Miller tears apart everyone and everything that irks him, making his targets look like minced onions at a hamburger bar. Yet at the close of each rant Miller says, “Of course that is just my opinion…I could be wrong!”

With one simple phrase Miller captures a key to evincing EQ vis-à-vis others: Vulnerability. Recognizing the limits of your knowledge is a much safer strategy than letting the little you know lead you into danger.

July 25, 2014

How Virtual Humans Can Build Better Leaders

The aviation industry has long relied on flight simulators to train pilots to handle challenging situations. These simulations are an effective way for pilots to learn from virtual experiences that would be costly and difficult or dangerous to provide in the real world.

And yet in business, leaders commonly find themselves in tricky situations for which they haven’t trained. From conducting performance reviews to negotiating with peers, they need practice to help navigate the interpersonal dynamics that come into play in interactions where emotions run high and mistakes can result in lost deals, damaged relationships, or even harm to their — or their company’s — reputation.

Some companies, particularly those with substantial resources, do use live-role playing in management and other training. But this training is expensive and limited by time and availability constraints, and lack of consistency. Advances in artificial intelligence and computer graphics are now enabling the equivalent of flight simulators for social skills – simulators that have the potential to overcome these problems. These simulations can provide realistic previews of what leaders might encounter on the job, engaging role-play interactions, and constructive performance feedback for one-on-one conversations or complex dynamics involving multiple groups or departments.

Over the past fifteen years, our U.S. Army-funded research institute has been advancing both the art and science behind virtual human role players, computer generated characters that look and act like real people, and social simulations — computer models of individual and group behavior. Thousands of service men and women are now getting virtual reality and video game-based instruction and practice in how to counsel fellow soldiers, how to conduct cross-cultural negotiations and even in how to anticipate how decisions will be received by different groups across, and outside of, an organization. Other efforts provide virtual human role players to help train law students in interviewing child witnesses, budding clinicians in how to improve their diagnostic skills and bedside manner, and young adults on the autism spectrum disorders in how to answer questions in a job interview.

Our research is exploring how to build resilience by taking people through stressful virtual situations, like the loss of a comrade, child or leader, before they face them in reality. We are also developing virtual humans that can detect a person’s non-verbal behaviors and react and respond accordingly. Automated content creation tools allow for customized scenarios and new software and off-the-shelf hardware are making it possible to create virtual humans modeled on any particular person. It could be you, your boss, or a competitor.

Imagine facing a virtual version of the person you have to lay off. Might you treat him or her differently than a generic character? What if months of preparation for an international meeting went awry just because you declined a cup of tea? Wouldn’t you wish you’d practiced for that? If a virtual audience programmed to react based on your speaking style falls asleep during your speech, I’d be surprised if you didn’t you pep up your presentation before facing a real crowd.

It is still early days in our virtual-human development work, but the results are promising. An evaluation of ELITE (emergent leader immersive training environment), the performance review training system we developed for junior and noncommissioned officers, found that students showed an increase in retention and application of knowledge, an increase in confidence using the skills, and awareness of the importance of interpersonal communication skills for leadership.

A related study showed that subjects found the virtual human interaction as engaging and compelling as the same interaction with a live human role-player. I can say from personal experience that asking questions of the students in a virtual classroom can be exhilarating (and unnerving when the virtual student acts just like a “real” student, slouching in boredom and mumbling an answer). Unlike a live human actor, however, a virtual human does not need to be paid, can work anytime, and can be consistent with all students, or take a varied approach if needed. Virtual human systems can have the added advantage of built-in assessment tools to track and evaluate a performance.

Technology alone is not the answer, of course As I recently wrote in “Virtual Reality and Leadership Development,” a chapter of the book Using Experience to Develop Leadership Talent, virtual humans and video game-based systems are only as effective as the people who program them. No matter how convincing a virtual human is, it’s just an interface. If the instructional design behind it is flawed it won’t be effective. So we focus as intensively on what a virtual human is designed to teach, how learning will occur, and how to continuously improve its performance as on the technology itself.

I believe simulation technologies are going to change the way we educate and train the workforce, particularly in the area of social skills. In time, just as a pilot shouldn’t fly without practicing in a simulator first, managers and leaders will routinely practice with virtual humans for the challenging situation they’re sure to encounter.

When the Jobs Go Away, They Take Your DNA

Eleven years ago, a full tenth of Kannapolis, North Carolina, residents were laid off when the town's textile mill closed. This could be the start of yet another story about the decline of manufacturing in America, but it's not. It's a much more nuanced tale. You see, aside from a Walmart, Kannapolis's most promising economic opportunity is in the hands of Los Angeles billionaire and health and life-extension aficionado David H. Murdock. Murdock purchased the old mill in 2004 and turned it into what journalist Amanda Wilson describes as "a public–private campus that would host research efforts broadly in his areas of interest." Yes, it employs people — but primarily people with advanced degrees from out of town. Regular old residents are offered the opportunity to work at the genomics lab as research subjects.

"At any given time, Kannapolites can take part in studies of nutrition, longevity, or cognitive or physical performance; eat a standardized diet; or spend time in a metabolic chamber while their vital signs are monitored — sometimes for $30 to $250 and up," reports Wilson. As you can imagine, this is where things get complicated. It's worth your time to read the entire piece for all the reasons why.

Clean Up Your Subcontracts 4 Tips for Business to Ensure Ethical, Slavery-Free Supply ChainsThe Guardian

It may not seem like a topic for a listicle, but this quick rundown of what businesses need to keep in mind to avoid exploiting vulnerable people – and becoming embroiled in often well-deserved PR nightmares — is entirely useful. After acknowledging how complex and unwieldy supply chains have become, Jessica Burt poses the question: "How can you ensure you aren't contracting with a criminal?" The answer: Do your research, audit supply contracts, understand the pressures your suppliers are facing, and don't be satisfied with the bare minimum. "Going above and beyond the basic rules, truly interrogating your supply chain, pre-empting cumbersome legislation, and taking voluntary action should be the target of any forward-thinking brand," says Burt. Amen.

Take a Good, Hard Look In Market Basket Protests, Three Lessons for Corporate AmericaWBUR

Here in Massachusetts, you can't go anywhere without someone mentioning what's happening at Market Basket, a grocery chain with loyal employees and stores that are almost impossible to navigate on weekends because they’re so packed. The backstory involves warring factions of the family business, the ousting of the company's beloved CEO, and subsequent employee protests that have resulted in firings, boycotts, and empty shelves. While the story may seem local, its lessons are anything but, argues MIT's Thomas Kochan. To start, it demonstrates just how frustrated workers are with "short-term, self-interested owners and corporate executives who choose to line their own pockets at the expense of the workforce and their customers."

Maybe most important, the events are "sending a message to business schools across America that it is time to teach the next generation of managers how to lead companies in ways that better balance and integrate the interests of all stakeholders,” including frontline employees and communities that support the business.

Searching for MeaningComputer Engineering: A Fine Day Job for a PoetThe Atlantic

I love this Q&A with poet TJ Jarrett, whose literal day job is as a senior integration engineer working on a decision system for medical-equipment purchases. At night she goes to a loud bar where she writes poetry, some of which will appear shortly in the collection Zion, her second volume of poems. IT suits her well. In fact, she sometimes feels that she’s found her dream job. She sees connections between her two kinds of work: Whether she’s troubleshooting code or imaginatively exploring black Americans’ lives under Jim Crow laws, one of the themes of her poetry, she has to “watch the parts coming together like gears and ask good questions. How did it come to be like this?” —Andy O’Connell

SighWomen Penalized for Promoting Women, Study FindsThe Wall Street Journal

We know that women are penalized in a multitude of workplace situations, such as when they negotiate salary. New research out of the University of Colorado puts the terrible icing on this often depressing cake by finding that women who promote women up the ranks are rated less highly by their bosses — and the same is true of nonwhite managers who boost the careers of nonwhite employees. But when it comes to white men, the authors found that they got a bump in performance scores when they were perceived as valuing diversity.

One of the study's authors, David Hekman, says he thinks the results go back to notions of self-interest: "People are perceived as selfish when they advocate for someone who looks like them, unless they’re a white man." And if executives who aren't white men "believe it’s too risky to advocate for their own groups" — which this research seems to bear out — "it makes sense that successful women and nonwhite leaders would end up surrounded by white males in the executive suite."

BONUS BITSInside Stories

Is T.J. Maxx the Best Retail Store in the Land? (Fortune)

Burger King Is Run by Children (Businessweek)

The Fasinatng … Frustrating … Fascinating History of Autocorrect (Wired)

Collaborate Across Teams, Silos, and Even Companies

Everywhere I turn right now, I hear leaders talking about their need for collaborative leadership. It’s being identified as the fundamental differentiator in achieving strategic objectives. In order to make a difference though, it has to go beyond the polite, thoughtful behaviours of involving others, sharing information and lending strength when it’s needed. I define real collaborative leadership as: facilitating constructive interpersonal connections and activities between heterogenous groups to achieve shared goals. It is proactive and purpose-driven.

Dubai Airports offers a case study. Leaders there are being incredibly proactive in their collaborative leadership efforts, with a very clear purpose. While already running the world’s busiest airport (passenger traffic grew to almost 66.5 million in 2013, a 15% rise on the previous year), they recognized that to achieve their vision of becoming the world’s leading airport company, they need to drive a new service culture through the 3,400-person organization. But they knew they couldn’t make a meaningful change in their culture alone. To change customers’ real experience of Dubai Airports, they needed to engage their vendors and partners as well.

One of the outcomes is a customer-service training program that is being rolled out over a three-year period across many stakeholder organizations and 43,000 employees. The Dubai Airports team is investing in training for over 39,000 people outside of their own organization, aiming to ensure behavioral consistency and therefore customer experience consistency at every possible touch point. Samya Ketait, VP for Learning and Development says, “This is a huge project, but a worthwhile one. It means that regardless of who you meet at Dubai Airports – a police officer, a cleaner, an immigration officer… you should have the same positive customer experience. Collaborating with our stakeholder leaders has made this possible.”

While it’s spoken of highly in organizational life, it’s not something that necessarily comes easily. It may seem like a lovely, generous gesture of Dubai Airports to offer to provide customer-service training for so many other organizations’ employees, but the leaders from outside who bought into this collaborative processes had to weigh the costs of their employees’ time out of work to participate, and to trust Dubai Airports with training their teams in a way that would match their own organization’s values and objectives. To sustain the three-year collaborative process and achieve its goals, these leaders recognized the behaviors that would make it work. When it comes to collaborative leadership, these factors can drive success:

Focusing on interests rather than positions. As with negotiations and conflict resolution, one of the most important keys to successful collaborative leadership is focusing on interests rather than positions. When leaders are “collaborating” they are typically not from the same team – otherwise we would most likely frame it as “teamwork.” What makes teamwork different from collaboration is the goal. In collaborative leadership cases the goals may be different – the leaders may have different positions, but yet common ground can be almost always be found at the level of interests. In collaborating with others ask, “What’s most important to you here? What really matters?” Encourage their openness and foster trust by sharing personally what your main drivers are.

Being an agent and a target of influence. We spend a lot of time in leadership development helping professionals to have greater influence (i.e. be a more successful agent of influence). Rightly so, as influence (e.g. influencing people towards common goals) is at the core of what constitutes leadership. Of equal importance when it comes to collaborative leadership, is being prepared to be a target of others’ influence. This requires: openness to alternative ideas; inquisitiveness to understand the foundation of others’ arguments before pushing back and asserting one’s own ideas; and recognition of the value the other party has and therefore can add to the collaborative venture.

Having clear roles and responsibilities. Research has shown that where leaders are successfully leading together, they have a clear sense of who is responsible for what. Mapping out these roles and responsibilities early, and refining them along the collaborative journey, ensures a smoother road.

Sharing and acknowledging the credit. We know that acknowledging our own part in a problem, even if it’s taking only 5% of the blame, alleviates tension during conflict and leads to faster reconciliation. The reverse is true of facilitating collaborative success. Acknowledging others’ contributions – be they big or even incredibly small, in the success of our ventures, energizes them in our collaborative efforts. Nothing undermines collaborative leadership like one leader taking — be it actively or passively allowing others to allocate them — all the credit.

Carving out space and time to collaborate – and a mission worthy of that effort. Too often in organizational life we know we’re meant to be collaborating and so try to squeeze it into our schedules when really we just want to get the pressing things on our to-do list done, or collaborate simply to the point of meeting our own immediate priorities. In order for collaborative leadership to be purposeful and sustainable, it needs to meet all parties’ true interests, warrant their time, and help them achieve their core objectives. Leaders need to highlight why this particular collaboration matters (not just extol “collaboration” in general), what difference it will make, and encourage the project’s participants to create the time and space it deserves.

One of the most exciting parts of the collaborative leadership journey is that while it is purpose-driven (there are clear goals and objectives in mind to achieve along the way), the end is unwritten: we never know where our collaborative leadership efforts may take us. One door opens another possibility and one creative venture prequels another.

The Evidence Is In: Patent Trolls Do Hurt Innovation

Over the last two years, much has been written about patent trolls, firms that make their money asserting patents against other companies, but do not make a useful product of their own. Both the White House and Congressional leaders have called for patent reform to fix the underlying problems that give rise to patent troll lawsuits. Not so fast, say Stephen Haber and Ross Levine in a Wall Street Journal Op-Ed (“The Myth of the Wicked Patent Troll”). We shouldn’t reform the patent system, they say, because there is no evidence that trolls are hindering innovation; these calls are being driven just by a few large companies who don’t want to pay inventors.

But there is evidence of significant harm. The White House and the Congressional Research Service both cited many research studies suggesting that patent litigation harms innovation. And three new empirical studies provide strong confirmation that patent litigation is reducing venture capital investment in startups and is reducing R&D spending, especially in small firms.

Haber and Levine admit that patent litigation is surging. There were six times as many patent lawsuits last year than in the 1980s. The number of firms sued by patent trolls grew nine-fold over the last decade; now a majority of patent lawsuits are filed by trolls. Haber and Levine argue that this is not a problem: “it might instead reflect a healthy, dynamic economy.” They cite papers finding that patent trolls tend to file suits in innovative industries and that during the nineteenth century, new technologies such as the telegraph were sometimes followed by lawsuits. But this does not mean that the explosion in patent litigation is somehow “normal.” It’s true that plaintiffs, including patent trolls, tend to file lawsuits in dynamic, innovative industries. But that’s just because they “follow the money.” Patent trolls tend to sue cash rich companies, and innovative new technologies generate cash.

The economic burden of today’s patent lawsuits is, in fact, historically unprecedented. Research shows that patent trolls cost defendant firms $29 billion per year in direct out-of-pocket costs; in aggregate, patent litigation destroys over $60 billion in firm wealth each year. While mean damages in a patent lawsuit ran around $50,000 (in today’s dollars) at the time the telegraph, mean damages today run about $21 million. Even taking into account the much larger size of the economy today, the economic impact of patent litigation today is an order of magnitude larger than it was in the age of the telegraph.

Moreover, these costs fall disproportionately on innovative firms: the more R&D a firm performs, the more likely it is to be sued for patent infringement, all else equal. And, although this fact alone does not prove that this litigation reduces firms’ innovation, other evidence suggests that this is exactly what happens. A researcher at MIT found, for example, that medical imaging businesses sued by a patent troll reduced revenues and innovations relative to comparable companies that were not sued. But the biggest impact is on small startup firms — contrary to Haber and Levine, most patent trolls target firms selling less than $100 million a year. One survey of software startups found that 41% reported “significant operational impacts” from patent troll lawsuits, causing them to exit business lines or change strategy. Another survey of venture capitalists found that 74% had companies that experienced “significant impacts” from patent demands.

Three recent econometric studies confirm these negative effects. Catherine Tucker of MIT analyzed venture capital investing relative to patent lawsuits in different industries and different regions of the country. Controlling for the influence of other factors, she estimates that lawsuits from frequent litigators (largely patent trolls) were responsible for a decline of $22 billion in venture investing over a five-year period. That represents a 14% decline.

Roger Smeets of Rutgers looked at R&D spending by small firms, comparing firms that were hit by extensive lawsuits to a carefully chosen comparable sample. The comparison sample allowed him to isolate the effect of patent lawsuits from other factors that might also influence R&D spending. Prior to the lawsuit, firms devoted 20% of their operating expenditures to R&D; during the years after the lawsuit, after controlling for other factors, they reduced that spending by 3% to 5% of operating expenditures, representing about a 19% reduction in relative R&D spending.

And researchers from Harvard and the University of Texas recently examined R&D spending of publicly listed firms that had been sued by patent trolls. They compared firms where the suit was dismissed, representing a clear win for the defendant, to those where the suit was settled or went to final adjudication (typically much more costly). As in the previous paper, this comparison helped them isolate the effect of lawsuits from other factors. They found that when lawsuits were not dismissed, firms reduced their R&D spending by $211 million and reduced their patenting significantly in subsequent years. The reduction in R&D spending represents a 48% decline.

Importantly, these studies are initial releases of works in progress; the researchers will refine their estimates of harm over the coming months. Perhaps some of the estimates may shrink a bit. Nevertheless, across a significant number of studies using different methodologies and performed by different researchers, a consistent picture is emerging about the effects of patent litigation: it costs innovators money; many innovators and venture capitalists report that it significantly impacts their businesses; innovators respond by investing less in R&D and venture capitalists respond by investing less in startups. Haber and Levine might not like the results of this research. But the weight of the evidence from these many studies cannot be ignored; patent trolls do, indeed, cause harm. It’s time for Congress to do something about it.

Most Managers Think of Themselves as Coaches

As a manager, do you think of yourself as a leader or as a coach? Do you, for instance, feel it’s important that your staff see you as an expert or do you prefer to create an egalitarian environment? Are you the person who solves problems or helps your staff come up with their own solutions? Are you more comfortable being directive or collaborative?

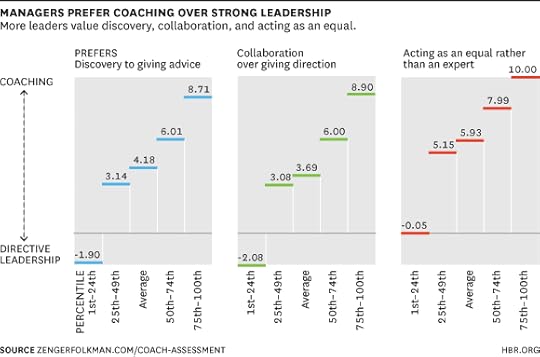

Results of a survey we’ve been conducting indicate a stronger desire to display coaching attributes than we were expecting.

Our assessment consists of 30 items we have tested and correlated to the most important attributes associated either with strong, top-down leadership or excellent coaches. (If you have not yet, we encourage you to take the assessment now, so that you can compare your scores with the those we present below.)

More than 2,00o readers responded to the survey. The results represent a global audience with 60% of respondents from the U.S., 10% from Europe, 9% from Asia, 6% from Canada, 2% from Central/South America, 2% from Africa, and 11% who did not identify their location. Respondents represent a fairly even mix of all levels in the organization: 20% executive management, 23% senior management, 27% middle management, and 30% supervisors or individual contributors.

You can compare your scores to others in the chart below here, which displays ranges of scores we’ve so far collected for the three different attributes. A negative score indicates a preference strong, direct leadership, managing through applying your expertise and through giving advice and clear direction. A positive score indicates a greater desire to act as a coach. Generally speaking, we have found through our research and our experience, excellent coaches would rather help others discover an answer for themselves than give advice. They prefer to act collaboratively rather than tell people what to do. And they prefer to act as an equal rather than as an expert. And as we analyzed the data, we were surprised (and frankly, pleased) to see that three-quarters of scores were positive, indicating that the vast majority preferred to manage through coaching.

Years ago, Joe recalls sitting through an introduction by the CEO of a Fortune 50 company that had grown dramatically by acquisition. In his presentation, he said, “The reason we bought all these different companies was that we felt like they would be worth more together than they would running as separate entities. The only way we get that value is through your efforts to collaborate and work together.” Most of the CEOs across the world have given that same speech. Apparently, people are hearing the message.

Well, perhaps. What we’ve tracked here are people’s desire to act in a particular way, not what they actually do. We imagine many readers are saying to themselves, “My boss does not seem that interested in letting me discover my own solutions.” Or many could be musing, “It’s true that sometimes we desire an open, collaborative conversation only to find ourselves barking out directions and orders.” That can happen, but there’s a world of difference between organizations in which people fall short of a collaborative ideal and those that don’t subscribe to it at all.

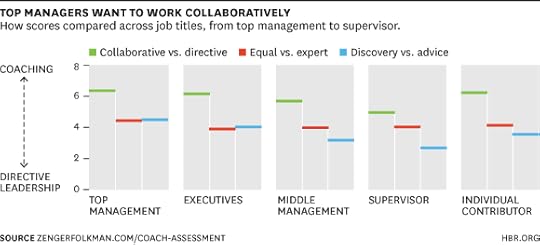

As we looked further into the results, we found those in top management positions to have the strongest desire to be more collaborative and help others find their own solutions; supervisors ranked the lowest. That jibes with our own experience, in which we find supervisors often believe that they are expected to give advice, give orders, and assure that orders are executed. But, remarkably, even this group prefers coaching to directive leadership to some degree.

We find these results so heartening because, frankly, we’ve seen supervisors and managers who were really good at getting results by giving lots of direction and advice and staying on top of all the details. A really effective autocratic leader can be efficient and quick about getting things done. But something suffers in the process. People wait for orders. They stop taking initiative. Their level of engagement declines slowly—and often rapidly—as time progresses. It can be easy in the effort to get the job done to lose sight of the long-term goal of helping people get better at getting the job done. The enormous value of coaching is what it does to develop people and create an ever more engaged and empowered team of employees.

In China, Breathing Is a Work Hardship

Expatriate employees of Coca-Cola working in China receive 15% bonuses because of the country’s air pollution, according to a Bloomberg article about a report in the Australian Financial Review (local Chinese aren’t eligible for the bonus). Panasonic has announced that it too will compensate expatriates in China because of air pollution. The U.S. State Department offers a “hardship differential” to employees who serve in posts with difficult circumstances, including unhealthful conditions; the differential ranges from zero in Kunming, China, to 30% in industrial areas such as Shenyang.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers