Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1391

July 25, 2014

CEOs, Get to Know Your Rivals

In an interview, Cisco CEO John Chambers once remarked on his intimate knowledge of rival CEOs. He claimed that based on this insight he could anticipate their market moves one or even two steps in advance. I thought he might be exaggerating, making good copy but lacking substance.

I decided to test his claim by interviewing current and former C-suite executives, including Bob Crandall, former CEO of American Airlines; David Norton, former CMO of Harrah’s casinos; Will Ethridge, CEO of Pearson Education; and Pat O’Keefe, former CEO of Watts Water Technologies. From plumbing equipment to casinos, these executives all agreed: what Chambers said was not only true but almost an understatement. In fact, I began to see four different strategies for keeping track of — and out-maneuvering — rivals:

Look for weaknesses that present opportunities. “It’s important to understand your rival’s weak spots and strategy,” says Will Ethridge, Pearson Education’s former CEO. “I knew one rival whose CEO was focused on driving profitability and bringing up margins. I knew that meant he would be relatively focused on short-term results while mostly ignoring product development. I also realized he would go after our top sales people to meet those short-term sales goals. So we worked extra hard to protect our key sales people. At the same time, we continued to invest in long-term product development and overseas markets, knowing it was unlikely he could follow us in the short term.”

Play to your strengths, not your rival’s. David Norton, former CMO and SVP of Harrah’s/Caesars points out that you must appreciate your counterpart’s competencies and weaknesses, as well as your own. Gary Loveman, then CEO of Harrah’s, was an MIT-trained economist. He had recruited other quant experts, such as Norton, formerly of American Express. They saw the casino business as a great numbers experiment. Among their rivals was Sheldon Adelson, CEO of Las Vegas Sands Corporation, who they believed operated from gut feel. He made a killing by opening casinos in Macau and Singapore.

Adelson’s bold move in Asia had outflanked Harrah’s. But Norton says the executive team didn’t conclude that they should abandon their quantitative strengths in favor of big rolls of the dice. Instead, Loveman decided to apply their deep quantitative knowledge of customer behavior in casinos and double down on U.S. expansion, out-maneuvering Adelson in the domestic market.

“We used data to personalize our marketing and become more efficient in attracting and holding onto customers,” says Norton. “And when it came to expanding our presence in the U.S. market we knew no one else would go to the extent we did, investing heavily in analytics, training and so on to build a comprehensive loyalty program.”

Encourage employees to monitor rivals, too. Former American Airlines CEO Bob Crandall, like Chambers, watched his counterparts, but more broadly he encouraged the entire corporation to watch the competition at all levels.

“It’s like running a national intelligence network,” he says. “If you are running it right, everyone is aware that anything and everything is important, and lots of information trickles up to management. For example, if a ticket agent in Chicago hears from an agent at another airline that the rival airline is looking for additional gate space, she should tell the local manager, who calls the division head who feeds it up the line. Senior management could then make some guesses about what the rival is up to, and could either add flights to use existing gates more intensively or take other action to blunt the success of whatever the rival might do.”

Meet the competition in person. You don’t have to watch your rivals from afar – or engage in deception to get close to them. In fact, face to face contact can pay off in unexpected ways. Pat O’Keefe was CEO of Watts Water Technologies, a global plumbing, water safety, and control equipment company. According to O’Keefe, his mandate was to grow Watts, largely through acquisitions. He spent most of his time seeking out and learning about acquisition candidates.

“I was personally obsessed with looking at our competitors,” said O’Keefe. “I wanted to know more about them than other bidders, when and if the time came to make them an offer. But there was no point in deceiving them. Their CEOs all knew who I was and they would very willingly show me their products. I visited them regularly to ask if they might like to join the Watts family of companies.

No matter the industry, John Chambers is right. CEOs not only can, but should, be watching their counterparts closely, assessing their strengths, weaknesses and predilections, and developing counter-measures accordingly.

July 24, 2014

The Future of Talent Is Potential

Linda Hill, Harvard Business School professor, and Claudio Fernández-Aráoz, senior adviser at Egon Zehnder, on the talent strategies that set up a company for long-term success. Linda is the coauthor of Collective Genius, and Claudio is the author of It’s Not the How or the What but the Who. Both authors will be speaking at the World Business Forum, October 7–8, 2014.

Why CEOs Should Follow the Market Basket Protests

Somebody must have done something really right at Market Basket.

Thousands of the supermarket chain’s employees have organized rallies at their local stores and at the company’s headquarters during the last week. Were these employees rallying for higher wages, better benefits, and predictable schedules — the needs so many retail employees face? No, they were demonstrating to help their ousted CEO, Arthur T. Demoulas, get his job back (he was fired in June after coup led by his cousin, Arthur S. Demoulas).

At a time when we see so much division between CEOs who represent the 1% and their workers who representing the 99%, this is amazing. Other CEOs should take heed. Such support is priceless.

Market Basket is a profitable family-owned regional chain of 71 supermarkets in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, with around 25,000 employees. According to Forbes, it’s the 127th-largest private company in the United States, with $4.6 billion in revenue. It has a loyal customer base who value the chain’s low prices and good service — as evidenced by the thousands of customers who have signed petitions backing the employees. The combination of low prices and good service is delivered by a loyal, committed, and capable workforce. If you visit a Market Basket store, take a look at the employee name badges — which include length of employment — and you will likely be impressed by how long people have been working there.

Market Basket employees don’t seem to stick around just for the wages and good benefits, however. The rallies for Demoulas suggest that they truly believe in his leadership and the direction he set for the company.

Yet, as I visited Market Basket stores and talked to employees during the last two days, I saw that they are not just fighting for their ousted CEO and his leadership and guidance. They are fighting for their values, their culture. They are fighting to remain an organization that takes care of its customers and its employees, a place where they can be proud to work.

Several employees told me they worry that Market Basket will become like any other supermarket. They worry that to make a quick buck, the company will increase its prices or reduce its service or reduce employee benefits or profit-sharing — maybe all of these.

These employees recognize that a “good jobs strategy” that allows companies to deliver great returns to investors by taking care of employees and offering low prices and great service to customers is a rare strategy to see in their industry. They recognize that it is a strategy worth a fight. They are right.

How Internal Entrepreneurs Can Deal with Friendly Fire

We know some of you find being an “internal entrepreneur” disappointingly difficult. You are frustrated by employers who thwart your entrepreneurial efforts on a routine basis. But that’s how it is supposed to be! Large organizations, with rare exceptions, are created to scale up and master repetition without error or variance. They are professional Predict, Plan & Execute (“PP&E”) machines, and as they have evolved over time, are carefully engineered to stamp out anything that induces uncertainty. The stock market demands this—and the systems, structures, and procedures (including the career path of your boss) support and reward it. For you to expect this situation to change quickly or without some pain is naïve and, quite possibly, mean-spirited. Imagine you are a professional long-distance runner and decide to switch careers and become a professional tennis player. Think it might take a while? Organizations can take 10 times longer to change.

But we see signs of change. Innovation is the number one topic on CEOs’ minds in various surveys. Many companies are creating chief innovation officers. There has been explosion in the past 10 years of conferences and popular and academic books, articles and blogs on the topic. Scores of boutique consulting companies and every major consulting firm now has an innovation practice.

We’re optimistic about the future of innovation in organizations, but for sure the continued dominance of the “PP&E model” makes things difficult for you. Perhaps hardest of all is the disappointment and frustration that comes from people you see on your team constantly and systematically rejecting what you believe is a commonsense action toward some sort of improvement. The external entrepreneur can experience this sort of market non-acceptance on a daily basis. While it can be dispiriting, the best don’t let it get to them. What makes it particularly difficult for the entrepreneur inside is that it feels like you are taking “friendly fire” from your own team. That’s because you are! But you can’t let that get you down. It’s not personal. Your organization would do it to anyone trying to operate outside of the PP&E operating system.

Our first bit of advice for those of you in this situation is: persist. Your internal situation is not that different from the external entrepreneur who must “befriend” her market—thinking of it as a treasured counselor teaching her about current reality—and never treat it as an adversary. True, this is difficult, but it is nonetheless required. You must change your mindset about opposition—from foe to friend—and then work hard to maintain it. You will never succeed if you view your organization and your colleagues as enemies. All of this is just as true for your perception of your boss; perhaps more so. Both you and your organization are in transition, and wherever the organization is right now is not as good as where it is going to be. You can help, but not if you don’t appreciate them.

Second, here’s a way to think about your situation—a simple diagnostic framework—that we’ve found helpful in our work with internal entrepreneurs. You, your boss, and your organization can each be in one of four modes: Make It Happen (Make), Help It Happen (Help), Let It Happen (Let) or Keep It from Happening (Keep). If you personally are not in the Make mode, you should stop selling your idea now. But assuming that you are… do your own diagnosis of your boss and your organization and an appropriate action strategy will become obvious. For example, if your organization is actively trying to suppress innovation (Keep) but you have a Make, Help, or even Let boss, you can try—very quietly. Or maybe your firm has a Strategic Innovation Imperative (look at the annual report for clues if you don’t know) but your boss wants you to do your job and nothing else (Keep). If senior management hasn’t helped him to change, it won’t be easy for you. You might be able to build support outside of your workgroup but it will be difficult and dangerous. You will probably be better off moving either to a more supportive boss or outside the organization.

Assuming that you really care about your innovative idea and your boss grants you some freedom to operate, you need to use the practical Act-Learn-Build steps that we talked about in a previous post, “Act Like an Entrepreneur Inside Your Organization.” Through your efforts you will help your boss be a better coach of you and others, and you will help your organization be more capable of supporting innovation and entrepreneurial behavior. If you don’t, chances are that you don’t care enough, and you should simply (and now happily) accept things as they are.

The Answer to Every Business Question Is “It Depends”

What happens when you put three business professors in a rental car and send them out to talk to owners and managers of small- and medium-sized businesses? Would they discover their MBA frameworks to be a bunch of academic mumbo-jumbo with no real applicability?

For the past several years, professors Mike Mazzeo (Kellogg), Paul Oyer (Stanford) and I (Utah) have been touring the back roads of America, knocking on doors, and asking business people how they do it. We trudged through ice and snow in Enid, Oklahoma, cruised over mountain passes near Missoula, Montana, and dodged mammoth raindrops in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. We got lost dozens of times, ate some dodgy meals, and, most importantly, learned a lot about business.

Our learnings support a single point, which Paul and I named in Mike’s honor. Mazzeo’s Law: The answer to every strategic question is “It depends.” Corollary: The trick is knowing what it depends on.

What we found is that there’s no best path to business success. Managers successfully address seemingly similar problems in very different ways and, as our corollary suggests, the trick is to find which solution fits with the specifics of your business.

In Johnson City, Tennessee, we chatted with Elisa Comer, the owner of Eagle’s Landing Informatics. The firm, which does medical transcription work, employs a couple dozen medical language specialists who listen to recordings of a physician’s spoken notes and generate typed records. We asked Elisa how she pays her transcriptionists, all of whom work remotely from home. “[They] are paid some number of cents per line based on the contract and the turnaround time,” she explained. “If they’re working extra, they get a few cents more per line.”

Elisa identified the performance she hoped to elicit from employees and simply tied pay to a measure of this performance. But, while this plan effectively aligns the interests of the employee with those of the company and motivated speeds, we worried about the side effects. “Are you concerned about accuracy?” we asked.

“Absolutely,” Elisa said. “’Is’ or ‘Is not’ is a big deal in medicine, and the doctors are not always helpful by dictating at a normal speed.” So Eagle’s Landing also employs a staff of quality assurance specialists to check on transcriptionists, especially new hires.

In Saint Joseph, Missouri, we met with JR Cheek, owner of JR’s TBA (for tires, brakes and alignment), who faced a similar problem but decided on a different solution. JR described the issue as follows: “Say a customer comes in for an oil change. I’m not here to rob anybody, but [when] the tech put[s] your car up in the air … he might uncover a want or a need that you have. If he asks for that order, that’s where I become profitable.”

Based on this description, we expected that JR could align employee and corporate interests by paying his technicians a commission based on the additional revenue they generate by identifying “wants and needs.” But JR told us that pay-for-performance didn’t work for him. Employees, he found, focused too much on uncovering problems with customers’ cars, creating an incentive to do a hard sell, or worse, to suggest unnecessary repairs, which turned people off and, JR believed, cost him more in the long run. His solution was to monitor and encourage the right activities, but to pay by the hour instead of connecting it directly to revenue.

Elisa resolved her speed vs. accuracy trade-off by paying for speed and monitoring accuracy, while JR Cheek resolved his “identify wants and needs” vs. “don’t hard sell” trade-off by abandoning commissions. So who’s right?

Probably both. The key to making good business decisions is to assess how the potential benefits and potential costs of a particularly strategy, in this case an incentive plan, pertains in your specific situation. Following our encounters with Elisa, JR and many other company owners like them, we have come to view business frameworks as a set of tools to help managers resolve the “what it depends on” question.

Use a Brand Council to Help Steer Strategy

David Packard, co-founder of Hewlett-Packard, once observed that “Marketing is too important to be left to the marketing people.” A more current corollary might be, “Brand-building is too important to be left to the brand people.”

The historical role brands have played – serving as symbols to guarantee a certain level of quality or as images to attract attention – is no longer relevant or useful today. A brand can’t just be a promise; it must be a promise delivered. And brand stewardship can no longer be under the exclusive purview of marketing departments and brand managers.

A 2008 survey of chief marketing officers and brand managers by the Association of National Advertisers found that 64% say their brands do not influence decisions made at their companies. Brands may drive communications activities, but little else. This means that nearly two-thirds of companies are pouring millions of dollars into marketing and advertising to promote certain values and attributes that may or may not be aligned with the reality of the business. Customers no longer tolerate the disconnects that arise from such gaps – and companies can no longer afford to keep brand-building a costly, discrete, and subjective set of activities.

Brand-building is a function that business leaders, owners, and general managers – the people responsible for the culture, core operations, and customer experiences of an organization – must drive. Smart companies form brand councils to meet this leadership imperative.

Brand councils are comprised of senior executives from a range of company functions: key business unit leaders, influential staff leaders from human resources, marketing, legal, and finance, and sometimes even the CEO. On occasion, these senior executives may designate lieutenants to sit on the brand council as their representatives, but they ensure the designees have the social capital, as well as the authority, to participate fully.

The brand council is charged with using the brand as the lens for strategic business decision-making. It uses the brand identity and positioning as guardrails to assess the appropriateness of proposed initiatives and as standards to evaluate their execution. The charter of a brand council is usually limited to oversight and approval, not implementation, so it draws the line between what is on-brand and what is not, and holds project teams and working groups accountable to it.

Brand councils usually devote the most attention to three areas of the organization.

Product development often requires strong executive brand stewardship because the pursuit of innovation and the pressure to fill the pipeline often cause teams to veer off-brand. A brand council can resolve conflicting priorities, or at least bring the parties with different interests together in a brand-focused discussion.

Partnerships are also potential brand stumbling blocks that deserve attention. Whether it’s a strategic partnership, a distribution deal, or a co-marketing campaign, companies often enter into agreements with a focus on the business opportunity and the business terms of the contract. A brand council can ensure brand objectives are also met and brand equity is protected in the arrangement.

Brand councils are actively involved in people issues. Not only do they shape people strategies throughout the employee lifecycle, from recruitment to transition, but they also serve as champions for brand alignment and engagement throughout the organization. Brand councils often oversee the development and deployment of brand guides and tools, and they may provide leadership for brand rollout meetings and experiences. Brand council members also represent their functions on the council, giving them voice and visibility to other executives by recognizing their brand-related successes and raising their brand-related concerns.

Forming and running a brand council requires a significant investment of time and energy by executives who already have very full plates. But companies must stop thinking about and using brands as static outward-facing, image-oriented objects. No longer is a brand an experience mediated through messaging and marketing communications. It is the experience that is actually delivered and expressed through every single thing the organization does, every day. As such, brand-building needs to be led at the highest levels of the organization. It can’t be delegated to a marketing department or an advertising agency. It must be driven – and embraced – as an enterprise-wide approach. A brand council is how savvy companies ensure this happens.

Ultimately, though, the best brand councils operate with the goal of making themselves unnecessary. Rather than relishing the role of brand police, they inform, inspire, and instruct the organization on stewarding the brand, so that over time, everyone in the organization knows how to appropriately interpret and reinforce the brand.

The Emotional Boundaries You Need at Work

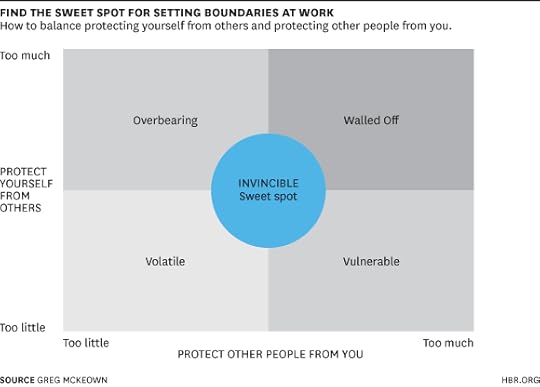

To develop meaningful and mature relationships at work or at home we need to develop two filters. The first filter protects you from other people. The second filter protects other people from you.

Filter 1: protect yourself from others. I once worked with a manager who gave blunt feedback in perpetuity: “You’re not a grateful person!” and “You’re just not a great writer!” and “Well, that was dumb!” My response, at first, was to listen as if everything he said was true. On the outside, I became defensive — but on the inside, I returned home emotionally beaten up. Every night my wife, Anna, would listen to the details of the encounters and help me to discern truth from error. One day she just said, “You’ve got to learn to consider the source!” My error was not that I didn’t listen, but that I listened too much. In other words, I needed to learn to filter the feedback.

Filter 2: Protect other people from you. On the other hand, I once worked with a leader with whom I felt I could be completely open. One day she said to me, “I value what you have to say, but sometimes it feels like I’ve been punched in the solar plexus when we talk.” Clearly, I was not doing a good enough job at protecting this colleague from me. I needed to increase the filter of what I shared and how I shared it. (For further reading see Pia Mellody’s work on boundaries).

Learning to apply enough of both filters — but not too much — is tough. Too much or too little can create relationship conflict as depicted in the matrix below (with a hat tip to “The Relationship Grid” by Terrence Real)

Here’s how it works:

If both filters are low, you’re volatile.This is the worst position to be in: you don’t protect yourself from other people or protect other people from you. If you’re in this place you will act like a wounded animal. You will feel hypersensitive to what someone is saying to you but you will speak defensively. You may feel like a victim but will act like a bully.

When you find yourself feeling this way, ask, “Am I seeing the situation clearly?” and “Do I feel like I am overreacting here?” and “Does it seem like the other person is overreacting here?” Apply a tax to what the other person is saying; assume he isn’t 100% accurate. Look for one thing you agree with and discard the rest. Hold back your own words until you feel clearer. Write down what you feel like saying to him (and do it on paper so you can’t send an outraged email accidentally), then review it later.

If you have one high filter and one low filter, you’re either overbearing or vulnerable. If you’re overbearing, it’s is a tricky position to be in; you feel confident but may be unknowingly causing offense. You’re saying what you believe, but may seem too outspoken. The problem is that you may not be adjusting well to other people because you’re not really hearing them. You’re communicating like it’s a one-way street.

When you sense this situation, say, “Perhaps I am being a bit bombastic about this. Do you see this differently?” or “You know, I have been wrong before. What are your thoughts?” Hold back more than you feel like doing.

When you are vulnerable, you protect other people from you, but you don’t protect yourself from other people. You take feedback personally but also struggle to push back on others.

Remember you have the right to be treated kindly. When you find yourself in this situation, think of the words of Dr. Maya Angelou: “There’s a place in you that you must keep inviolate. You must keep it pristine. Clean. So that nobody has a right to curse you or treat you badly. Nobody. No mother, father, no wife, no husband, no — nobody. You have to have a place where you say: ‘Stop it. Back up. Don’t you know I’m a child of God?’”

And when both of your filters are too high, you’re walled off. In this position, you are basically withdrawn. You’re being overprotective of what you say and what you absorb. You’re not going to give or take offence, but you can seem aloof and a bit cold.

Try opening up a bit. Say, “I want to share something with you, but I want you to be gentle with me on this.”

When we find the right balance with these two filters, we find the sweet spot, and become invincible. Here, we have the ability to know and be known. We can listen without risk of permanent damage and speak without risk of offending. We can navigate complex relationships because we can adapt without losing sight of who we are.

The truth is that we can be in different places with different people. The challenge is to figure out where we are in any particular relationship and then to adjust towards the sweet spot, where relationships thrive.

July 23, 2014

Don’t Let Your Head Attack Your Heart

I had been planning a dinner party for weeks. There were twenty people coming, some family, some friends, to celebrate my wife Eleanor’s birthday. I designed a ritual for her: my goal was to create a space where people spoke from their hearts in a way they don’t usually do.

I prepared questions I wanted us to explore together, questions like: What do you feel grateful for in your life? What new things do you feel are struggling to grow and be born in you? What do you want to let go of, so that the new can be born?

Before I go any further, pause for a second, imagine yourself at the dinner, and notice your own reaction to those questions. Are you rolling your eyes at the touchy-feeliness of them or do they excite you? Would the answers you shared be superficial or deep?

I was excited and nervous as I introduced the initial question. I shared from my heart. Then, one person, David*, made a joke. It was light fun, but it was directed at my response and felt biting. Others laughed and chimed in. Then more jokes. I tried to keep the focus of the group but I failed.

I had been so excited and now I just felt sad, angry, vulnerable, and disappointed.

This is what I discovered that night: The heart is an easy target of the mind.

I was asking questions of the heart, and the mind fought back. We are trained and rewarded, in schools and in organizations, to lead with a fast, witty, and critical mind. And it serves us well. The mind can be logical, clear, incisive, and powerful. It perceives, positions, politics, and protects. One of its many talents is to defend us from emotional vulnerability, which it does, at times, with jokes and quick repartee.

The heart, on the other hand, has no comebacks, no quips. Gentle, slow, and unprotected, an open heart is easily attacked, especially by a frightened mind. And feelings scare the mind.

Why are feelings so scary? I asked my friend and colleague, Jessica Gelson, a traditionally trained psychotherapist who specializes in body-based techniques to help people unblock their feelings.

“People are afraid of feelings for the same reason people are afraid of ghosts,” Jessica told me. “You can’t see them. You can’t put them in a box. And you can’t really control them.”

Most of us are never taught how to experience and understand our feelings. And since our mind hates things it doesn’t know, it reacts like a guard fending off an attack.

But why is that bad? Why not just rely on your agile and capable mind instead of exposing your heart, especially in a business or professional environment?

Because our hearts are the source of our real power.

The heart is how we connect with others. It’s how we engender trust. It’s the heart — both ours and theirs — that makes people want to follow us and throw everything they’ve got into making something successful. People follow leaders who show competence and warmth, head and heart. And there is a growing body of evidence that suggests we should start with the heart.

It takes tremendous courage to lead. And it takes even more courage to lead with heart. But that’s what leadership call us to do. Mostly, when people want to develop their leadership, they try to learn more about what to do. Which is precisely why most leadership programs fail. Because the hard part about leadership isn’t knowing what to do, it’s having the courage to do it.

Are you willing to experience the discomfort of speaking from your heart? Yes, it’s a risk. But a risk whose payoff includes the commitment, loyalty, and passion of the people around you.

Now, think back to how you answered the question at the beginning. Was your instinct to protect yourself and your open heart? Would you have resisted answering those questions honestly and openly? How can we be more emotionally courageous in those situations, both as the listener and the speaker?

Notice. Notice when your head wants to protect your heart. Notice how you might use humor to avoid feeling something. I am now aware that I do this myself. Honestly, I like the positive attention I get when people laugh. But I’m now sensitive to the cost. How it shuts me – and other people – down. When your instinct is to make a joke, see if you can pause without saying anything and notice what you feel.

Take risks. Taking risks builds your emotional courage. And you don’t even need to take big, emotional risks. Maybe your risk is speaking up in a meeting, or not speaking up, or asking about someone’s day, or giving someone feedback. Courage begets courage. The more you take even small emotional risks, the more you’ll be willing to show up authentically in all areas of your life. You’ll have a chance to practice this, right here, in a moment.

At Eleanor’s birthday dinner, I wavered. But, once I realized it, I saw it as an important opportunity to practice emotional courage. My risk was to call David, the person who first started the joking, and tell him that it felt hurtful. Without attacking him, I shared my disappointment and sadness.

He was defensive at first, but soon we engaged in a deep and real conversation about his discomfort and how hard it was for him to share his feelings at the dinner. We both learned some important lessons and felt closer after that call.

I’m still interested in how people choose to answer the questions I asked at that dinner party. I’d love to see your responses in the comments, if you feel comfortable sharing them. What do you feel gratitude for in your life? What new things do you feel are struggling to grow and be born in you? What do you want to let go of, so that the new can be born?

*Names and some details changed.

Design Offices to Be More Like Neighborhoods

As more people flock to urban areas (about 80% of the U.S. population lives in cities), government officials and academics are becoming more interested in the study of urban space. This has coincided with a boom of new methods to study cities on a macro scale – but many of these techniques can also be used on a micro level to understand and improve workplaces and employee conditions. One practice in particular – integrating urban physics in workforce planning – has the potential to make waves.

Urban physics, a more recent addition to Urban Studies, is currently being used by researchers at MIT and NYU to determine how systems within a city interact with each other and with individuals. Marrying traditional research principles with Big Data, urban physics involves monitoring and analyzing an endless supply of urban variables — crime rates, traffic flow, spread of infectious diseases — to understand emerging patterns, problems, and opportunities for change. Urban physicists are applying this research to reimagine a number of concepts, including the energy efficiency of city buildings, infrastructure conditions, and emergency detection.

The basic principles of urban physics can prove equally useful in planning office spaces. Its use of quantitative information can help organizations optimize their spaces in a way that positively reinforces their overarching mission, and accommodates the unique work styles of their employees. Urban physics has the power to transform workspaces to reflect companies’ true ethos and values, to instill a sense of belonging in employees, and to encourage productivity, engagement, and overall happiness.

Companies across the globe are forging into the future by using urban physics to rewrite the commonly held definitions of office space. Google, for instance, has a room in their Chicago office crafted to resemble an intimate speakeasy, a common space for employees that promotes cross-departmental “serendipitous encounters.” Or take Groupon, which uses carnivals, tiki huts, and enchanted forests motifs to spark employee creativity. The “conventional” workspace (drop ceilings, monochromatic cubicles and all) is being phased out in favor of connected spaces that encourage innovation and demand collaboration while still prizing individuality.

Google’s speakeasy room taps into the relationship between an interesting workspace and employee engagement.

More businesses are striving for vibrant, youthful spaces, but they must be careful not to let eco-friendly water coolers dilute the bigger picture; wall decals and a foosball table don’t equate to company culture or employee satisfaction. By applying urban physics to office decisions, companies can actually improve workflows and organizational culture.

Groupon’s tiki bar “conference room” acts both as an escape from work and as a space that encourages innovation.

Infusing science into office planning doesn’t mean you need to have a Ph.D. on staff. Consider these ways to think more like an urban physicist in your next office steering committee meeting:

Generate more data. Apply your company’s CRM or business intelligence systems to internal operations. Start gauging employees’ peak workload times, and think about how your physical space can mitigate extended peaks or encourage more departmental cross-pollination during down time. Google provides a model for putting these kinds of insights to work in the workplace. Executives at the company’s Chicago office realized that employees went to coffee shops when they were busiest. So the company built its own in-house café, letting staff sustain their ingrained habits while creating an atmosphere for peak productivity in the office.

Go straight to the source. Use your company’s intranet or another internal communication tool to provide an outlet for all employees (from intern to executive, remote to in-office) to ask tough questions or offer opinions about your office environment. Sustain a consistent feedback loop to measure what the staff thinks about their current workspaces, and what is due for an adjustment. This is exactly how voice-based marketing automation firm Ifbyphone found success. By surveying employees prior to designing their space, executives learned first-hand how personnel at all levels wanted their new environment to look, act, and feel.

Find your feng shui. In a non-intrusive, transparent way, track employees’ movement within the office to identify which conference rooms or meeting areas see the most traffic, and which areas get minimal use. Depending on what trends and habits appear in the data, even small physical rearrangements could help improve certain processes, decrease idle time, and boost productivity. Take online advertising and media buying firm Centro, for instance, which boasts glass conference rooms to reflect the firm’s emphasis on transparency. Providing executives with full viability allows them to easily measure which spaces are employee favorites. Firms should optimize the most popular spaces, and reform conference room duds. Coffee bars, quiet rooms, and intern “housing” all make for more productive uses of space than underutilized conference areas.

Use technology for smarter scheduling. Establish a greater connection between technology and employees — beyond the one they have with their own iPhones. For example, digital consulting firm Rightpoint uses a connected tablet system on conference room doors to let employees know when rooms are free. Conference room technologies can also house room reservations and meeting agendas. In smaller offices where meeting spaces (that aren’t the kitchen) come at a premium, a small addition like this can help employees determine room availability and avoid an eleventh-hour scramble.

Space is both a reflection and projection of company culture. By embracing modern science and diving into the interactions between system and individual, firms can construct a space that addresses employees’ obvious and more obscure environmental needs. Applying urban physics to your office space requires a new kind of thinking toward something that often boils down to desks and chairs, but in today’s business world, the extra thought counts.

Should Couples Go into Business Together?

There’s a ton of advice aiming to answer whether or not couples working together is a good idea, as more and more couples are choosing to open joint firms. It’s been estimated that 3 million of the 22 million U.S. small businesses in 2000 were couple-owned, and that number has likely gone up.

But to really answer this question, we have to ask: Why do couples choose to go into business together – and what are the benefits? New research from the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) looks into this. Using a sample of 1,069 Danish couples that established a joint enterprise between 2001 and 2010, the study revealed that couples often establish a business together because one spouse (usually the female) has limited outside opportunities in the labor market. And it found that starting a business together led to significant income gains for both spouses (but especially the female), both during the life of the business and post-dissolution. The research suggests that starting a business together is typically a sound investment of both spouses’ human capital, and it has the added benefit of reducing income inequality in the household.

To identify the labor market prospects of these entrepreneurs, the study looked at how much they made before starting their venture. The data shows that, on average, women in co-entrepreneurial couples earned 27% less beforehand than women in couples where each partner owned their own business, and 33% less than women in couples where only one partner was an entrepreneur.

This indicates that wives who choose to open a firm with their spouse come from a less advantageous labor market position and join the business because the opportunity cost is low. And the authors concluded that this decision wasn’t due to these couples being any more traditional than others. Since co-entrepreneurial wives see even higher income gains than their husbands (because they made significantly less pre-venture), the earnings difference between both spouses shrinks. The study also found that couples that open businesses together are no more or less happy than other couples (measured by usage of antidepressants or anxiety/insomnia medications), and they’re no more or less likely than their counterparts to separate, divorce, or have children.

Viewed through the lens of income, this research suggests that couple-founded companies have the potential to mitigate gender inequality. Unfortunately, previous studies reveal a different picture. A 2013 research paper out of UNC Chapel Hill found that gender inequality in the distribution of control was more likely to occur within spousal teams. According to the authors, “women have reduced chances to be in charge if they co-found new businesses with their husbands,” because certain expectations around gender-typical work (breadwinner v. homemaker) affect wives’ and husbands’ power positions – as do other family conditions like having children. So husbands are more likely to take the lead of new business, while wives end up in a subordinate role, and gender ideologies that shape their social roles and responsibilities at home reinforce these positions (a tension we’ve highlighted before in a case study).

Other research hints at differences between women who start businesses with their spouses and those who venture out on their own. Kathy Marshack, a clinical psychologist who studies entrepreneurial couples, pointed out that co-entrepreneurial wives often feel it’s their job to make their husbands “look good.” She often found that even if the wife is the founder of the business and her husband joins later, she may identify herself as a “co-owner” rather than the founder or president. “I found that the wives were not as independent as women who were in a career separate from their husbands,” Marshack said. “On a test of sex role orientation, they tended to score high on desirable feminine traits, whereas dual career wives scored high on desirable feminine traits and high on desirable masculine traits. The latter is what we tend to see with women who function as more independent professionals in the work world. They also have more egalitarian marriages than the copreneurial wives.”

While the IZA’s research points to higher incomes for co-entrepreneurial wives (and “cautiously” infers that spousal teams have productivity advantages), going into business with a spouse is bound to be challenging – and often comes with its own set of gender biases.

Families and couples working together has always been the norm, from family farms to mom-and-pops to Walmart. And there are plenty of couple-founded business success stories, e.g., Kate Spade and Flickr (before the founders split). But today, most of the challenge around erasing that work/home line stems from couples’ unclear working roles (a lack of “defined working roles” is apparently one reason why VCs may be reluctant to invest in a husband-wife start-up) and the need to also balance family responsibilities.

So should couples go into business together? There is no easy answer. Taken together, the research suggests that there are often real financial benefits to doing so, but that gender inequality often comes into play. It also provides advice for those thinking about taking the plunge: consider what your other career options are, and be sure to talk openly about how you plan to share responsibilities, at work and at home.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers