Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1387

August 1, 2014

GE Is Avoiding Hard Choices About Ecomagination

After nine years, GE is taking its famous green initiative, ecomagination, into some complicated territory. This includes a new open innovation program that encourages ideas to reduce greenhouse gases from Canadian oil sands production — the same controversial, greenhouse-gas-heavy source of fossil fuels that environmental groups are fighting against when it comes to the Keystone XL pipeline.

By stretching ecomagination into areas that many people clearly don’t consider very green, GE may be risking a valuable business and brand asset.

Launched in 2005, ecomagination has always been a bit amorphous. Is it a marketing campaign? A corporate strategy? A guide for product and service development? In truth, ecomagination is all of these and more. GE always kept the program broad, including both flashier, clearly green products like wind turbines, and also more industrial, behind-the-scenes offerings such as energy-efficient motors.

The company has reaped $160 billion from the program since 2005. These revenues grew twice as fast as total company sales, providing a critical crutch in the post-financial-meltdown years (GE gets about half its business from financial services). Given the value of the program to GE and the broader green business movement, it should be handled carefully — and it has, for the most part.

But that may be changing, as evidenced by two recent announcements. First, when the company committed $10 billion in R&D for “clean tech” technology by 2020, it put at the top of the list of priorities a goal to develop alternative water technologies for fracking natural gas. Fracking is another contentious process, but one that even some major environmentalists have supported as long as there is no significant methane leakage during extraction (which negates the greenhouse gas reduction that comes from substituting gas for coal).

Second, GE launched the third installment of the Ecomagination Innovation Challenge, an open innovation competition that previously asked the world for ideas to help “power the grid” and “power the home.” In those incarnations of the initiative, GE and its venture capital partners invested serious money, $140 million, into some great clean tech businesses.

But this new contest is different, with its focus on the above-mentioned Canadian oil sands.

If the world is going to continue using oil sands and fracked natural gas (the latter much more assured than the former), then, yes, we should do it with as little water or carbon impact as possible. Oil sands, more accurately called tar sands, require shocking amounts of energy to melt the tar — so lessening those production emissions is a worthy goal. But then we still face the serious problems associated with using so much oil, including climate change (emissions from burning the fuel) and global security concerns (the global market for oil props up petro-dictators). So cleaning up oil sands is like putting a filter on your cigarettes — it’s a bit better, but it will still kill you.

Innovation in oil sands takes GE, and all of us, further from where we need to go. We’re facing monumental challenges globally, and the cost of inaction on climate change is rising fast (see a recent compelling report from former US Treasury Secretaries and Mayor Mike Bloomberg titled “Risky Business“). Our biggest and best companies need to shift more dramatically to a truly clean economy and make what I’m calling a big pivot.

In short, we don’t have time or excess capital to spend on making the old world fuels cleaner just because we’re dependent on them now. It’s a clean economy “all in” moment for humanity.

I spoke to GE executives to get their perspective, and in many ways, the company sounds like it is making a big pivot. GE’s Chief Marketing Officer, Beth Comstock, says that the company is spending “record amounts” on renewables-related clean tech, including “energy storage, solar, LED, lighter materials and advanced manufacturing,” as well as energy efficiency, distributed energy, fuel cells, and biofuels. Global Communications Leader Gary Sheffer posed this question: “Who’s doing more research on renewable energy in the world than GE?” (It’s hard to say, but any list of companies spending as much as GE is certainly short).

But GE, pursuing what Sheffer calls an “ambidextrous” strategy, wants to make the dirty forms of energy cleaner as well. This dual focus has always been a part of ecomagination, Sheffer says. From the GE point of view, then, this latest use of ecomagination is in keeping with its nine-year history. As Comstock said, “We believe we exist to help solve some of the world’s toughest problems. Ecomagination has always been about using GE’s invention and scale to solve tough challenges in a way that benefits the environment and business economics.”

But there’s the problem. As sustainability thought leader Hunter Lovins put it, oil sands are “economically dicey as it is…any price on carbon and it fails.” Meaning, if through taxation or regulation, the world makes carbon-based energy more expensive, the economics of carbon-heavy energy sources get much worse. Pricing carbon is no longer fringe policy —according to a World Bank report, “40 national and 20 sub-national jurisdictions are putting a price on carbon…covering 12% of annual global GHG emissions.” And even in the U.S,. the tide is turning: former Treasury Secretary and Republican Hank Paulson recently called for a carbon tax.

Given a shifting regulatory and social attitude toward carbon, supporting oil sands — even if you’re making it marginally cleaner— is bad for the environment and very likely bad for business.

Oil sands move the world in the wrong direction on carbon, and suck up intellectual and fiscal capital that could we could allocate differently. So let’s get more heretical about GE’s future and ask whether the company should help the oil sands sector at all. Is it so hard to imagine a company walking away from a current source of revenue? Drug store chain CVS recently had the guts to stop selling tobacco, worth $2 billion in sales, because cigarettes don’t fit the company’s mission on “health.”

But let’s say that it’s hopelessly naïve to think that public companies will voluntarily give up on objectionable lines of business. Fine, then GE should make its product offerings as environmentally sound as possible. But those initiatives should be part of business as usual, not necessarily fall under a banner as (supposedly) forward-looking as ecomagination. Today, making oil sands cleaner is not as imaginative as we need to be.

So in the end, it may be semantics whether you call it ecomagination or not. In reality, this discussion is about the heart of our economy and the souls of the companies that drive it. Every company and country is going to face some really hard choices very soon, and we’ll need to ask a core question: Will we turn to the future and put all we’ve got into building the clean economy? Or will we try to have it both ways?

As the wise Mr. Miyagi said to the Karate Kid 30 years ago, “Walk on road, hm? Walk left side, safe. Walk right side, safe. Walk middle, sooner or later get squish just like grape.”

The Aging of American Businesses

The year was 1995.

Tom Hanks was awarded an Oscar for Forrest Gump, Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise” was number one on Billboard, and a young undergraduate named Monica Lewinsky began a summer internship at the White House.

Elsewhere, Timothy McVeigh murdered 168 people in Oklahoma City, three years of war in the Balkans came to an end, O.J. Simpson was acquitted of double homicide, and the World Trade Organization was formally launched on New Year’s Day.

A lot has changed since then—the iPhone, Tivo, the Toyota Prius, Google, Facebook, YouTube, human genome sequencing, GPS navigation, Skype, mobile broadband, just to name a few.

And yet, despite all of that change and memories of historic events that now seem ever distant, America’s business sector might be less dynamic than ever. That’s the major takeaway of research I co-authored with Robert Litan of the Brookings Institution and published this week. The evidence is pretty overwhelming.

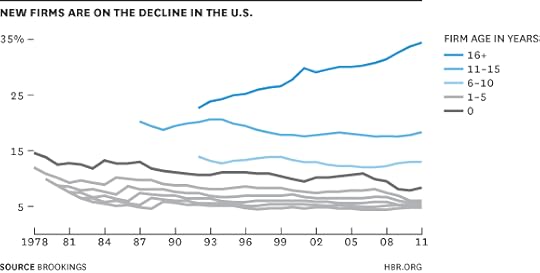

Our research documents a steady rise in economic activity occurring in mature firms during the last two decades, and declining in new, young, and medium-aged firms, or what we dub “The Other Aging of America.” Mature firms (those aged 16 years or more) comprised 34 percent of U.S. businesses in 2011—up from 23 percent in 1992, for an increase of half in just under two decades.

The situation is more pronounced with employment. By our estimate, about three-quarters of private-sector employees and nearly 80 percent of total employees (private + public) work for organizations born prior to 1995. This is especially remarkable considering the volume of product innovations and household-name businesses that have emerged in the last two decades.

Further, we found that the aging of the business sector during this period has been universal across the American economy—occurring in every state and metropolitan area, in every firm size category, and in each broad industrial sector.

The evidence suggests that a decline in entrepreneurship is playing a major role; perhaps the largest. As we and others demonstrated in previous research, the rate of new firm formation has fallen by half during the last three decades, and has contributed to the decline of American “business dynamism”—the productivity-enhancing process of firm and worker churn. Fewer firm births means fewer young and medium-aged firms. It’s a matter of simple arithmetic.

Compounding this, we document a sharp uptick in early-stage firm failure rates and believe it might be playing an increasing role over time. The failure rate of firms aged one year—the youngest firms in our data outside of freshly launched ones—increased from a low of 16 percent in 1991 but rose steadily and persistently to reach 27 percent by 2011. It is possible that the increased likelihood of failure in the first year is holding back would-be entrepreneurs from forming businesses at all. In the last decade, failure rates have also increased for all firm age categories except for one—mature firms, where failure rates have held steady.

In short, fewer firms are being born, and those that are born are increasingly likely to fail very early on, as are firms that survive into young- and medium-aged years. Those that are old, on the other hand, tend to persist, allowing them to constitute a larger share of economic activity in the United States over time.

Somewhat surprisingly, we were unable to find evidence of a direct link between business consolidation and an aging firm structure. Though we do find a substantial rise in consolidation during the last few decades—confirming the widely suspected belief—it doesn’t appear to be a major contributor to business aging specifically, which has been occurring across all firm size classes, and most of all in the smallest of businesses. If business consolidation were a driving factor, we wouldn’t expect this to be the case.

This leaves some questions unanswered and some future areas for research—most notably the cause of declining business formation. But whatever the reason, our research clearly establishes that it has become increasingly advantageous to be an incumbent, particularly an entrenched one, and less advantageous to be a new and young competitor—regardless of business size, location, or broad industry group.

The Value of Customer Experience, Quantified

Intuitively, most people recognize the value of a great customer experience. Brands that deliver them are ones that we want to interact with as customers — that we become loyal to, and that we recommend to our friends and family. But as executives leading businesses, the value of delivering such an experience is often a lot less clear, because it can be hard to quantify. Rationales for focusing on customer experience tend to be driven by a gut belief that it’s just “the right thing to do.” The problem with this is that often, whether experience is a priority or not simply becomes a battle of opinions.

It was for this reason that we wanted to explore ways of quantifying the impact of good versus poor customer experiences — and then see what the value was in delivering them. In order to do so, we gained access to experience and revenue data from two global, $1B+ businesses. One of these was a transaction-based business; the other, a relationship-based subscription business.

What we found: not only it is possible to quantify the impact of customer experience — but the effects are huge.

We looked at two companies with different revenue models — one transactional, the other subscription-based — using two common elements that are relevant to all industries: customer feedback, and future spending by individual customers. To see the effect of experience on future spending, we looked at experience data from individual customers at a point in time, and then looked at those individual customers’ spending behaviors over the subsequent year. While transactional businesses primarily care about return frequency and spend per visit, subscription-oriented industries focus on retention, cross-sell, and upsell. We used multiple regression to account for factors that might drive these outcomes other than customer experience — for instance, the fact that exercise enthusiasts might simply enjoy their gym membership more regardless of experience — and estimate how much of the behavioral differences were due to past customer experience. After doing so, it soon became clear: customer experience is a major driver of future revenue.

What we found: after controlling for other factors that drive repeat purchases in the transaction-based business (for example, how often the customer needs the type of goods and services that the company sells), customers who had the best past experiences spend 140% more compared to those who had the poorest past experience.

The results for the subscription-based business were equally impressive. Whereas a transaction-based business is interested in how often customers return, a subscription-based business is primarily interested in how long their customers remain loyal. Our findings: A member who rates as having the poorest experience has only a 43% chance of being a member a year later. Compare this to a member who gives one of the top two experience scores — they would have a 74% chance of remaining a member for at least another year. We were also able to use this data to predict future membership length based on the quality of experience. The difference: on average, a member who gives the lowest score will likely only remain a member for a little over a year. Compare that to a member who gives the highest score — they are likely to remain a member for another six years.

These are dramatic differences.

Of course, the rationale we often hear for not investing to deliver a great experience is that the cost is high. Speaking to executives inside these businesses, however, we often hear the opposite. That is: delivering great experiences actually reduces the cost to serve customers from what it was previously. Unhappy customers are expensive — being, for example, more likely to return products or more likely to require support. Systematically solve the source of dissatisfaction, you don’t just make them more likely to return — you reduce the amount they cost you to serve. For example, Sprint has gone on record as suggesting that as part of their focus on improving the customer experience, they’ve managed to reduce their customer care costs by as much as 33%.

It’s time to stop the philosophical debate about whether investing in the experience of your customers is the right business decision. This isn’t a question of beliefs — it’s a question about the behavior of your customers. Connect the right data, and not only is it possible to quantify the impact of the difference between delivering a great experience and delivering a poor one — but it will demonstrate to everyone in your organization just how big that impact can be.

Ditch the Start-Up Pitch

How do you get somebody interested in investing in your startup? You pitch them the idea. Pitching skills are widely considered fundamental to basic entrepreneurship, and this skill is taught, evaluated, and rewarded as part of almost any entrepreneurial education. The problem is that pitching is a waste of time and teaching this as a primary skill of entrepreneurship is misleading and sets the wrong priorities for aspiring entrepreneurs.

Pitching ideas is accepted as an important entrepreneurial skill for two fundamental reasons. First, it requires aspiring entrepreneurs to create a short, precise description of their idea and why it is likely to result in a successful enterprise. With this first reason comes an implied assumption that entrepreneurs who can organize and present their ideas in a compelling and concise fashion have a better understanding of the potential business opportunity and will also be able to better recruit skilled talent to their teams. A second reason that pitches are well accepted is that they allow investors, professors, or judges evaluate a large number of ideas in a short period of time. An implied assumption associated with this second reason is that pitches are the best way to evaluate many ideas in a short period of time.

There is no evidence that the people who give the best pitches have materially better chances of entrepreneurial success than any other entrepreneur with the same motivations, traits, and skills presenting the same idea. Anecdotal evidence that comes from seeing many hundreds of pitches and having talked about pitches with many other startup investors, mentors, and academics indicates that people who are better at pitching are more extroverted and more willing to practice. I am not aware of any evidence that ties these traits to entrepreneurial success, but even if such a link existed, the pitch is hardly the best way to test them.

A counter argument could rest on the second major reason pitches are so popular, pitches are more about evaluating the idea than the entrepreneur and pitches are the best way to evaluate an idea. But this point has major flaws too. As good entrepreneurs (and investors) well know, even the best idea will not succeed without a skilled entrepreneur. Moreover, to the extent that the idea must be evaluated, the pitch is a poor way to do it. Start-up ideas are best evaluated in writing without the emotions created with a “live performance.”

If we want to produce more successful entrepreneurs then we need to realize that we must adopt a fast and effective test that evaluates all the things we know relate to entrepreneurial success: the entrepreneur, their idea, and their team. There are better ways to test for these three parameters within the same time frame as a standard pitch. Here is a process that could simply and effectively replace the pitch for evaluating potential entrepreneurial leaders and their ideas:

Ask aspiring entrepreneurs to send in advance a written description — under 400 words — describing their idea, their team, and why they expect to produce a good financial and/or social return.

Potential judges and/or investors read the summaries in advance and formulate three hypothetical situations that could occur in the development and commercialization of the idea. Each entrepreneur and his or her supporting team are given 15 minutes to develop proposed solutions, responses, or next steps to the three hypothetical situations. They are then given five minutes to present their responses.

This process evaluates, in a time efficient manner, the entrepreneur’s leadership ability, the idea, and the quality of the entrepreneur’s team – three things we know are critical entrepreneurial success factors. Some VCs run a process similar to this with the difference being that they do not give the entrepreneur and his team the hypothetical problems in advance, they just immediately interrupt the entrepreneur as he starts his pitch by asking him what he would do in some situation. This tests the entrepreneur’s ability to think on their feet — but this variation tends to overlook the potential strengths and contributions of the introverts on the team. In general, coming up with and verbalizing ideas under pressure tests more for extroversion than it does for leadership.

Pitching ideas for startups as a way to test for which entrepreneurs are most likely to succeed is a waste of time. The pitch tests for characteristics that are not tied to entrepreneurial success and misses those that are. Pitches are also an inefficient way to test ideas as potential reasons to start new enterprises. It’s time to ditch the pitch.

When Misfortune Happens to Us, We Believe We Deserve It

Research participants who were informed they had gotten an unlucky break and would have to forfeit £3, rather than win the same amount, subsequently viewed themselves significantly more negatively and believed they were more deserving of bad outcomes, showing that random misfortune damages people’s self-esteem, says a team led by Mitchell J. Callan of the University of Essex in the UK. This low self-esteem, which can lead to self-defeating beliefs and behaviors, stems from people’s need to believe that the world is just and predictable and that bad fortune is meted out to those who deserve it, the researchers say.

Relax, You Have 168 Hours This Week

There are 168 hours in a week; this is immutable truth. That sounds like a lot, but is it really enough time to cover the demands of a successful career, family involvement, and everything else that makes up a fulfilling life? Let’s do the back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Starting with those 168 hours, first take away 49 just for sleep. Don’t try to cheat on this. If you are getting less than 7 hours a night, you are probably not resting enough, and your decreased performance will take its toll on the rest of the hours of the week.

So you’ve really got 119 hours. Let’s assume you’re an ambitious professional and subtract 56 for work. That would amount to working 8 hours a day, 7 days a week – or, if your weekends are off-limits, 11+ hours a day on weekdays only. I know some of you put in more time than this. However, outside of very few professions (and peak times at others) no one really needs to – so if you do, you are probably working inefficiently or being pressured to uphold unrealistic expectations. In fact, research shows that productivity craters after 6 hours a day. If you work more than 56 hours a week, you may need to examine your time use.

Assuming 56, then, you still have 63 hours. But take out two more chunks of non-fun activity – 7 hours per week of commuting, and 13 hours per week of errands and routine housework – and you’re down to 43 hours. This is the amount of time you have for family and other aspects of life.

Childcare, cooking, and other responsibilities on the home front certainly take effort, but they can also serve as family connecting time. Let’s put you down for 20 hours of those.

Guess what: that leaves you with a full 23 hours. Maybe you’ve been saying you don’t have time for exercise, but it seems you do (and exercise makes you more effective the rest of your week at work and at home). Let’s devote 3 hours to that – and still give you 20 hours of free time to do whatever else makes you happy and healthy. It’s surprising, isn’t it: with a little prioritizing and planning, work and life aren’t so impossible to balance.

So here’s the real question: Why are we always so stretched? Why doesn’t 168 hours actually feel like enough time? I can name three culprits: time sucks, time confetti, and technology. And those suggest three ways to get your life back.

Don’t succumb to time sucks. These are those trivial activities that, once you get into them, are so comfortable that you just keep doing them. It takes real resolve to limit yourself to just a few hours of TV or gaming a week, or just one fantasy sports team, or just 30 minutes a day on Facebook. But try keeping a keeping a diary and adding up the hours you’re spending now, and you might just gain that resolve.

Stop tossing time confetti. In her book Overwhelmed, author Brigid Schulte makes an important distinction between time chunks and time confetti. The best way to use your free time, and make it really feel like free time, is to block it off in chunks. A dedicated hour of play with your kids feels like more time than four quick, distracted 15-minute interactions in between other stuff. The big problem with time confetti, Schulte says, is that it amounts to “contaminated time” which prevents pure enjoyment, relaxation, focus, and mindfulness.

Start being the boss of your technology. Smartphones, email, and other communication technology are great assets in the quest to get the most out of a day, but they can also create the perceived need to be accessible to work 24/7. Set limits such as “no screen hours,” letting everyone at work know the single time you’ll check email each night, and banning devices from the dinner table or family room. Lots of others have written about how unplugging actually leads to higher productivity.

I’m surely not the first to point out that your week contains 168 hours. It’s a staple of time management books and courses, as seen here and here. But until you go through the exercise yourself of adding up your weekly commitments, you probably won’t find the almost three hours per day potentially left over. Of course, all our situations differ, and some face more challenges and time commitments than others, but knowing that you have 168 hours might be the motivation you need to prioritize and make the changes that will make life more satisfying.

July 31, 2014

The Dangers of Confidence

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, professor at University College London, on how confidence masks incompetence. For more, read Confidence: Overcoming Low Self-Esteem, Insecurity, and Self-Doubt.

At the U.S.-Africa Summit, Leaders Need to Signal Change

Washington is usually quiet in August, but an event next week has the potential to shake things up for business and foreign policy.

More than 200 U.S. and African CEOs, including the heads of General Electric, Walmart, Blackstone, Google, and Coca-Cola, will gather on August 5 to attend the first ever U.S.-Africa Business Forum. Convened by the White House, the forum is the centerpiece of a three-day U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, which aims to strengthen ties and will bring together business leaders and more than 40 African heads of state – an unprecedented number in Washington at one time.

It’s clear why the White House has called for this business-oriented summit. Africa’s growth has been well chronicled in Harvard Business Review. More recent articles in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times summarize the case for U.S. commercial engagement in Africa.

How the U.S. government will succeed is less clear. There are a myriad of African business conferences, but even the largest of these pales in comparison to the scope and visibility of this event. Given the rise of Chinese influence in Africa, some in Washington have suggested the U.S. match the pageant of Chinese summits, with deal announcements and photo opportunities. Others have said that the U.S. must adhere to its history of pressing U.S. values at the expense of business opportunities.

Any of the successful CEOs attending would balk at these ideas. They would tell you that following your competitor’s strategy is a recipe for coming in second, and replicating what you’ve done before is a recipe for coming in last.

To succeed in this most unusual summit, U.S. officials must do the opposite: signal a break with patterns that hold the relationship back, and present an attractive alternative to the patterns of our competitors.

Can the summit mark a change in how the U.S. interacts with Africa? “I wake up every morning and wonder how I can help Africa.” That is how a senior U.S. official guiding Africa policy recently described his job motivation. Respectfully, that’s misguided. The U.S. taxpayer deserves a public servant who wakes up every morning thinking about U.S. interests. African business leaders, whom I know, understand that and expect it. The Summit will be filled with successful Africans building a continent and ready to meet us as equals. Look to see if our officials and executives are prepared for that.

Can the summit demonstrate a new orientation to the opportunities in Africa? Three-quarters of Africa’s growth in recent years has been outside of natural resources. Yet most U.S. investment in Africa is in natural resources. And contrary to what is widely asserted, the U.S. invests less in Africa’s manufacturing than Africa’s newer trading partners, including China. Can the U.S.-Africa summit signal a shift from that historic mismatch, and show the U.S. on a path of investing in what is above Africa’s ground, as well as what’s beneath it?

Can the U.S. disrupt our competitors’ models? In the race for opportunity and influence in Africa, no competitor looms larger than China, which has increased its total trade with Africa twenty-fold since 2001. The Chinese model of state capitalism has unique strengths that the U.S. will not match, such as subsidized financing at scale and freedom from the pressure to show positive quarterly results. As a result, China has contributed significantly to the continent’s development.

The Chinese are also more capable of closing summits with multibillion-dollar deal announcements. That’s a superficial manifestation of a very deep difference. The Chinese government commands its largest businesses. The U.S. government does not. And in that distinction lies the opportunity for the U.S. to overtake its competitors. The private capital model of the U.S. has the potential to create more skill, technology, and innovation in Africa than a Statist partner could. Intel’s African software developer platform and Microsoft’s continent-wide investment in entrepreneurship are the kinds of ventures we have not yet seen from China’s state-owned enterprises. Watch to see if the U.S. effectively highlights the differentiating advantages of U.S.-African collaboration.

Making these distinctions clear is at the core of winning opportunities and influence next week. The U.S. and Africa share a broad set of opportunities and values. It can be the role of this summit to clear preexisting patterns obscuring that reality.

How the Next Generation Is Approaching Society’s Biggest Problems

Though governments around the world have mounted massive campaigns to address poverty, expensive (and poor) healthcare, crime, and ineffective education, daunting challenges remain. Fortunately, we are witnessing three fundamental changes that offer hope.

First, private citizens, particularly younger people, are choosing different types of career paths. The old model — get a job, earn money, pay back — is being replaced by an earlier commitment to change. Wendy Kopp, who founded Teach For America, and Linda Rottenberg, who founded Endeavor are just two well-known examples. Second, changes in technology have dramatically lowered the cost of experimentation and create unprecedented transparency into problems, solutions, and results. Finally, innovation in the financial markets are funding novel approaches to address these problems.

Take the story of Salman Khan and the eponymous Khan Academy. Kahn, 38 years old, graduated from MIT in 1998 and Harvard Business School in 2003. Soon after, when Khan began tutoring his niece in mathematics while working at a hedge fund, he hit upon the idea of developing short video tutorials on YouTube. Each video showed Khan writing on a graphics tablet while talking about the subject. His niece, and many others, enjoyed the videos and were able to master content they struggled with in school. In 2006, Khan launched Khan Academy to deliver “a free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere.” By 2014, the academy comprised over 3,000 videos on subjects from mathematics to art history. Approximately 10 million people engage with that content each month.

When Khan started tutoring his niece he did not imagine he would devote his life to education; he was simply trying to be helpful. In the process he discovered a fundamental problem in American K-12 education — that the traditional lock-step approach to mass public education of everyone taking the same courses at the same age in the same sequence, did not work for millions of kids. Khan’s self-paced, master-then-move-on model changed the paradigm. Individuals or even entire schools were able to flip the typical classroom structure — have students watch Khan videos at night and do homework with the support of teachers during the day. He created tools to help teachers, students, and parents track progress. Students who mastered materials quicker could help students who needed more time or could go through more advanced materials.

How did Sal Khan finance his venture? Private donors have invested over $40 million since Khan Academy was officially launched in 2009. Philanthropists have also supported efforts to translate the content for local use. Khan has been able to attract some of the best computer programmers and educational content experts in the country even though he has no profits to share or stock options to grant. His backers believe that investing in Khan Academy represents one of the highest returns in improving education around the world (see this HBS case for more on how funders decided to get involved).

The Khan Academy story well illustrates those three changes we’re witnessing. First, Sal Khan could have continued in finance and made far more money than he does in a nonprofit. The same is true of everyone on his team. But, instead, they want to make the world a better place. Second, technology made Khan Academy possible. The cost of running the initial experiment — attaching a graphics tablet and microphone to a personal computer — was trivial. Distributing content over the Internet is also inexpensive, while reaching a potential audience of billions. Khan has easily created tools to measure mastery and progress for individuals and institutions, comparing the effectiveness of his classroom model to the traditional one. His niece, who might have been assigned to the “slow” math class, zoomed to the top of the class. Khan Academy does not replace public education, though it might in other countries; it supplements or complements what is possible for all citizens.

Finally, venture philanthropists are willing to invest in projects like Khan’s that can reach millions of people with a modest amount of money. In this case, a select group of private philanthropists have funded the organization. That’s great but the sums involved are modest compared to the $200 trillion in global financial assets. What if some of that capital could be deployed to attack social challenges? A relatively new instrument called a social impact bond is a powerful example of how this might be done.

Several years ago, one of us (Sir Ronald Cohen) and a group of like-minded individuals in England hit upon the idea of using private capital to fund efforts to reduce prison recidivism. When prisoners are released without an effective support system they are highly likely to end up back in jail, which is devastating to them and their families and costly to government. However, private social enterprises have been effective at reducing recidivism rates. Cohen and his colleagues created a bond, backed by private investors. If the social enterprise delivers on the promise of reducing the recidivism rate relative to current best practice, the investors receive their capital back and a capped but attractive rate of return. If not, the investors receive a lower return and risk losing their capital. The government benefits by saving money.

One can imagine many similar areas in which there are measurable costs and outcomes that might benefit from this approach. Increasingly governments are publishing data on the costs and consequences of issues like recidivism, dropping out of school, or treating certain diseases. This data provides a benchmark against which a financial instrument can be devised.

For example, there have even been efforts to use securitization techniques to support finding and delivering better therapies or cures in certain disease areas. Professor Andrew Lo and colleagues at MIT have pointed out that individual company efforts to find new therapies for cancer or Alzheimer’s are risky and not able to attract debt financing. If, however, there were a way to invest in a pool of such efforts, the aggregate portfolio risk would be far lower. Some investors with modest risk tolerance could invest in a bond secured by the pooled research and intellectual property. Other investors might buy equity tranches that have a higher likelihood of low returns but the potential for outsized returns.

These are exactly the kinds of new solutions we need to succeed where previous monolithic attempts to tackle society’s woes have failed. But these efforts won’t make a difference if people continue to protect the status quo and block these new ideas. Instead, we need to encourage the trends we’re witnessing — the continued commitment of human and financial capital and the use of technology in new and innovative ways — if we are going to help future generations create an affordable and equitable society.

McDonald’s Already Knows How to Manage Its Franchisee Labor Practices

The National Labor Relations Board ruling on Tuesday that McDonald’s could be held responsible for labor conditions in its franchisees’ operations has business groups and lawyers crying foul. McDonald’s says it will appeal, contesting the determination that it exercises “significant control” over the practices of its franchisees.

But McDonald’s is already going through great lengths to ensure good working conditions in the other direction in its value chain. It should do the same for franchisees.

Its sustainable supply chain program employs staff around the world to strengthen sustainability and working conditions in the operations of McDonald’s suppliers — also independent entities over which McDonald’s ostensibly has little control. (Disclosure: I have served as a judge for its Best of Sustainable Supply awards.)

Brands in other industries have realized that even though they may have minimal leverage on paper over parties with which they do business, they must proactively engage them on labor conditions. Rightly or not, their brand is likely to take a hit if major problems at a supplier come to light. And if a business partner is committing labor transgressions, there are likely quality, safety, or other problems lurking somewhere, too.

McDonald’s should apply to franchisees a model similar to the one it uses for its suppliers: The company engages in long-term relationships with suppliers to make it clear that they’ll work together on tough issues, not just issue fines; brings suppliers together periodically to learn from each other; and rewards innovation. A combination of internal staff and independent auditors ensures compliance and supports these efforts.

Then, McDonald’s might follow the lead of other industries and develop a collaborative initiative with peer companies and some of its harshest critics.

In the 1990s, oil companies (e.g., Shell in Nigeria and BP in Colombia) got into trouble for the abusive actions of security personnel supposedly protecting their facilities. As a result, those companies and others got together with NGOs such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International and the U.S. and U.K. governments to form the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, a code that spells out how companies can work with security providers in a way that respects the rights of local communities.

Other so-called “multi-stakeholder initiatives” have similarly cropped up to address the difficult problems that arise when companies don’t fully control the impacts of their businesses. The Global Network Initiative was created by Google, Yahoo!, and Microsoft and socially responsible investors, academics, and human rights groups to protect free expression and privacy on the internet. Government demands for surveillance or censorship was a major reason they did so.

The Fair Labor Association was created in the 1990s to bring together companies, civil society organizations, and colleges and universities to protect factory workers’ rights in complex global supply chains. Following the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse, the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety and the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety were established to focus on that country.

These initiatives have enabled companies to work with peer companies that face similar challenges, and collaborate with groups that have relevant expertise. Perhaps it’s time for a multi-stakeholder initiative on fair working conditions in franchise operations: not just for fast food chains like McDonald’s, but for hotels and retail outlets as well.

The challenges of ensuring labor compliance among franchisees are not insignificant. But McDonald’s neither needs to reinvent the wheel nor go it alone. There are models for how to tackle such difficult challenges — in other industries and within McDonald’s itself.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers