Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1372

September 4, 2014

Plan a Satisfying Retirement

You’ve worked hard all your life, and now you’re on the brink of retirement. Trouble is, the things you looked forward to all those years — mornings on the golf course, afternoons puttering in the garden, trips to exotic places — don’t feel like they’ll be enough to sustain you. Encore careers — jobs that blend income, personal meaning, and often some element of giving back — are becoming an increasingly popular alternative to full-time retirement. But where do you start?

What the Experts Say

According to Encore.org, a think tank focused on Baby Boomers, work, and social purpose, nearly 9 million people ages 44 to 70 today are engaged in second-act careers. “People are leading longer and healthier lives and so leaving full-time work in your mid-60s means that you’re looking at a horizon of 20 to 30 years. That’s a long time,” says Marc Freedman, CEO of Encore.org and the author of The Big Shift. There is, he says, the financial question of how you’ll support yourself, “and then there is the existential question: Who you are going to be?”

On one hand, it’s daunting to contemplate embarking on a new career at this stage in life. On the other hand, it’s liberating to “let go of the past” and forge a new identity based on “things that you find exciting, stimulating, or interesting,” says Ron Ashkenas, a senior partner at Schaffer Consulting and an executive-in-residence at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “It’s an opportunity to think about how you want to contribute to society, your community, and your family.” Karen Dillon, coauthor of How Will You Measure Your Life?, agrees: “Life doesn’t necessarily get simpler after you leave a full time job,” she says. “But it can become more rewarding — if you’re willing to hold yourself accountable and work for the new goals you’ve set yourself.” Here are some things to think about as you prepare to for this new phase.

Lay the groundwork early

If you’re confident that your job won’t be in jeopardy, tell colleagues about your plans to officially retire while you’re still gainfully employed. “Then it’s not out of the blue, and it also gives them a chance to figure out if they have contacts or a network you could leverage,” says Ashkenas. It’s also important that you leave on good terms with your company and indicate if you are open to occasional projects and assignments — which is a good way to keep your hand in your profession. Adds Dillon: “You can’t just stop working and expect the phone to ring. Plant seeds early so that once you’re in circulation, experiences and opportunities will come to you.”

Don’t rush

Once you leave your job, give yourself a period of time — ideally months in duration — to reflect on what you want to do next. “Give yourself time to rest, renew, and restore,” says Freedman. Navigating this transition will take some time. “You’ve been working and juggling family stuff for decades and likely haven’t had the time to think about this next chapter of your life. Recognize that finding work that is significant and fulfilling could take two to three years.”

Ask yourself: what’s really important?

Make a list of all the things “that feed you emotionally” and then drill down to figure out exactly what it is about those things that inspires you and makes you happy, suggests Dillon. For instance, you might list spending time with your kids or doing work that’s challenging, but “what you most enjoy is having new experiences with your children, like travel. And what you really like about work is collaborating with others and creating something,” says Dillon. “Push yourself to do the things that matter to you and be conscious of the choices you’re making and how you’re spending your time.” Your goal, says Freedman, is to “figure out what your priorities are at this juncture in your life.”

Be willing to experiment

Freedman advises taking a “try-before-you-buy” approach. “Find ways to dabble in things that interest you,” he says. Seek out internships, fellowships, or part-time jobs; give back by volunteering to serve on a board of a nonprofit; take on different kinds of professional assignments; or sign up for a class at a community college. “If it sounds fun and interesting and it seems as though you will learn new things, do it,” says Dillon. Also look for ways to transfer your hard-earned expertise to new domains, says Ashkenas. “It’s not as if you stop being who you are. You are still you, and you still have the same skills; you’re just applying them to new situations and environments.”

Keep productive

After you’ve given yourself some time off, it’s important to return to some of the things that office life gave you: structure and community. “Just as you would look ahead to milestones in your work, you need things to look forward to and anticipate,” Ashkenas says. Consider joining a group or community like an alumni association, a volunteer or religious organization, a freelancer’s group, a book club, or even a virtual community. After all, “you need the stuff you get from the informal office environment: banter, chatter, laughter, and information,” Dillon adds. It’s also helpful to spend time with others who are “wrestling with the same challenges you are,” says Freedman.

Hold yourself accountable

As you’re navigating this transition, “you have to think about goals,” says Dillon. “Get feedback from those you care about — like your spouse or partner, children, and friends — about how you’re doing. And be honest with yourself about how you’re spending your time. Do a reality check by asking yourself, “Do I feel good and healthy? Do I feel stimulated? Don’t let outside voices dictate your answers,” says Dillon. And once you figure out where you want to focus, Ashkenas says, “you need to keep asking yourself: Am I adding value? Am I making a contribution? Am I learning something?”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Find meaning in your new life by pinpointing how you most enjoy spending your time

Experiment with different jobs and assignments to stretch yourself and learn new things

Expose yourself to new perspectives and ideas by joining a community

Don’t:

Be secretive about your intentions to leave your job — share your plans with colleagues and let them know you’re open to new opportunities

Rush into a new job right away; give yourself time to relax and restore

Squander hours away just because you can; hold yourself accountable about how you’re spending your time

Case study #1: Embrace your personal passions as the source of new opportunities

The day that Gail Federici sold John Frieda — the professional hair care company she co-founded with the British stylist — her mind reeled. “We hadn’t been planning to sell the company,” she says. “Over the years we had meetings [with prospective buyers], but we wanted to keep doing what we were doing.”

Once the paperwork was signed, she took a one-week trip to Venice with her college roommate then returned home to London. At first it was a tough transition. “We had been building this company for 12 years: I had a definitive routine; I had a plan for the future; I had goals. All of a sudden it was gone,” she says. Gail decided to dedicate her time and energy to a personal passion: music. It was a natural second act: Her husband is a musician and Gail used to sing in his band in New York. At the time, the couple’s twin daughters were interested in becoming performers. “It was a huge learning curve for me: I had to read the back of CDs to find out the names of producers and songwriters,” she says.

Over the next five years, she worked on albums and promotions with several musicians and boy bands, including Taio Cruz, the British singer-songwriter and record producer. “It was exciting and challenging to learn a new industry but I was still doing what comes easy to me: marketing, problem solving, and strategizing.” After signing the main act she and her team developed to Interscope, she decided to “go back to what [she] does best.”

Now in her 60s, Gail is the President and CEO of Federici Brands, another hair styling company. While she is happy to be back in the hair care business, she looks back on her years in the music industry fondly. “I was out of my comfort zone but I liked it.”

Case study #2: Leverage your expertise and connections to give back

Bill Haggett spent the first part of his career in the shipbuilding business — first as President and CEO of Bath Iron Works in Maine and later as the head of Irving Shipbuilding of New Brunswick, Canada. After leaving Irving in the late 1990s and returning to Maine, Bill wanted to give back to his community.

His first priority: building a new YMCA in his hometown. Bill helped raise funds for the Y and also helped design the new complex. “I grew up in Bath, Maine in the 1940s and I am from a family of modest means,” he says. “The YMCA was a terrific outlet for me and my friends.”

By 2000, the Y project was complete, but Bill wasn’t interested in “moving into retirement mode.” The Libra Foundation, a large charitable organization in Maine, approached him about a job. “They wanted to make a strategic investment in a potato company in northern Maine on the brink of bankruptcy. And they asked: ‘Would I be willing to serve as chairman and CEO?’”

Bill knew nothing about the potato business, and he had little interest in moving to northern Maine. But after reflecting on what he wanted out of the next chapter of his life, he realized the opportunity was appealing. “It was a way to help the economy by adding value and jobs in that part of the state,” he says. The job would be fulfilling on a personal level too. “I wanted the challenge of turning this business around. It was a way to learn something new, but I also thought I had some expertise I could bring to the party.”

The early years were a struggle, but after a while, business at Naturally Potatoes improved: Sales increased by 40%, and the company returned to profitability. By 2005, it was sold to California-based Basic America Foods (BAF). Bill, meanwhile, went on to run a meat company. But Naturally Potatoes fell short of BAF’s expectations, and when, in 2010, a team led by Libra bought the company back, Bill resumed the role of CEO.

At the age of 80, Bill — who is chairman and CEO of Pineland Farms Natural Meats and Pineland Farms Potatoes — has no plans to stop working. “I feel energized,” he says. “One of the great pleasures of being my age is that everyone I work with is younger than I am. They have bright ideas, skills, and technology savvy that I don’t have.” Learning a new business every few years has been “stimulating,” he says. “I like to be useful and to make a contribution.”

To Make Better Decisions, Combine Datasets

A complicated system is somewhat like a complicated recipe.

You know what the outcome will be because you understand what will cause what — combine a given number of ingredients together in a certain way, put them in the oven, and the results will be consistent as long as you repeat the same procedure each time.

In a complex system, however, elements can potentially interact in different ways each time because they are interdependent. Take the airline control system—the outcomes it delivers vary tremendously by weather, equipment availability, time of day, and so on.

So being able to predict how increasingly complex systems (as opposed to merely complicated systems) interact with each other is an alluring premise. Predictive analytics increasingly allow us to expand the range of interrelationships we can understand. This in turn gives us a better vantage point into the behavior of the whole system, in turn enabling better strategic decision-making.

This idea is not new, of course. Firms have been developing models that predict how their customers will behave for years. Companies have developed models that indicate which customers are likely to defect, what advertising pitches they will respond to, how likely a debtor is to default (and what can be done to avoid making loans to that person), what will prompt donors to up the ante on their giving, and even who is likely to pay more for services like car insurance. Organizations such as Blue Cross Blue Shield have used their considerable databases about chronically ill people to target and influence their care, reducing to some extent the total cost of care, much of which is concentrated in helping a small portion of their total consumer base.

What is new is that the advent of predictive analytics, in which disparate information that was never before considered as or looked at as related parts of a system, is giving us new ways to see interrelationships across, and think comprehensively about, entire systems. Rather than arguing about what various kinds of activities will drive which outcomes, the questions can now be answered quantitatively. Indeed, as I argued in Harvard Business Review, complex systems with their continually changing interrelationships often defy understanding by using conventional means. This in turn creates the opportunity for strategic action.

An example of exactly this kind of action caught my eye in an unlikely setting—city government. New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, in an effort to help the city reduce its considerable cost of defending against and paying out legal claims made against the city, has turned to predictive analytics to help. The program is called ClaimStat and is modelled after Richard Bratton’s famous CompStat program of collecting crime data. The system tracks the incidences that led to the city’s paying out $674 million in payments for claims. Stringer’s website observes that “These costs are projected to rise over the next four years to $782 million by FY 2018, a figure that is greater than the FY 2015 budget for the Parks Department, Department of Aging, and New York Public Library combined.”

Using analytics, the city found a non-obvious systemic relationship—one where the dots may never have been connected otherwise—with costly unintended consequences: In fiscal year 2010, the budget allocated to the Parks and Recreation department for tree pruning was sharply reduced. Following the budget reductions, tree-related injury claims soared, as the Comptroller reports, leading to several multi-million dollar settlements with the public. One settlement actually cost more than the Department’s entire budget for tree pruning contracts over a three-year period! Once funding was restored for tree-pruning, claims dropped significantly. Such a relationship might never have been spotted absent the connected database, as the budget for Parks and the budget for lawsuits are managed as separate and unrelated resources. By bringing them together, the system-wide consequences of individual decisions becomes obvious and something that can be tackled in a strategic way.

In the coming years, we can expect to see smart organizations increasingly leveraging the power of multiple databases to get a real vantage point on their strategic challenges.

Predictive Analytics in Practice

An HBR Insight Center

Nate Silver on Finding a Mentor, Teaching Yourself Statistics, and Not Settling in Your Career

Beware Big Data’s Easy Answers

Who’s Afraid of Data-Driven Management?

When to Act on a Correlation, and When Not To

A Simple Fix Makes a Big Difference in Phone Thefts

Kill switches in cell phones appear to be having an effect on thieves. Thefts of iPhones declined 38% in San Francisco and 24% in London in the six months after Apple’s offer in September 2013 of software that allows users to lock down phones after thefts, and in New York City, robberies of Apple products fell 19% in the first five months of 2014, according to The New York Times. Cell-phone companies were slow to incorporate kill switches, which make it harder for thieves to resell stolen phones, but Samsung has added the technology to the newest version of its top-selling Galaxy S phones and is expected to add it to others soon.

The Ice Bucket Challenge Won’t Solve Charity’s Biggest Problem

I love the Ice Bucket Challenge. Period. It’s a collective expression of love in a world with far too little of it. It has generated public tears in an age with far too few of them. It restores faith. It connects. And, as of last week, it raised more than $100 million for the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association, up from donations of $2.8 million for the same period last year.

So, are we looking at the future of charity? We are glimpsing the potential of momentary collective engagement, but at the same time, we are seeing the confining rules by which nonprofits must play, collectively imprisoned in an ancient way of thinking. The ALS Association is already being scrutinized to make sure it doesn’t spend a penny of the Ice Bucket money on anything but research. So when the enthusiasm fades, there will be nothing there to replace it, because investment in the replacement was forbidden.

I love the Ice Bucket Challenge as a thing unto itself. But for the sake of the ALS Association and everyone afflicted with ALS, we must dedicate ourselves to something far greater – yes, far greater than $100 million. We must aspire to a statistically significant increase in charitable giving as a percentage of GDP. And for that to happen we need to give charities far more freedom to invest in that result.

Charitable giving in the U.S. was $335 billion in 2013, but only about 15% of that, or $50 billion, went to health and human services causes – 85% went to religion, higher education and hospitals. $50 billion isn’t near enough to cure cancer, ALS, AIDS, Alzheimer’s, and other threatening diseases. It’s not enough to end poverty, homelessness, bullying, and all of the other problems charities address.

Charitable giving has remained stuck at 2% of GDP in the U.S. ever since we started measuring it in the 1970s. In forty years, the nonprofit sector has not taken any market share away from the for-profit sector.

What keeps us from increasing charitable giving? We are inherently averse to seeing humanitarian organizations spend money on anything other than “the cause,” as we define it, and we define it very narrowly. We condemn them for using donated resources on building market awareness or on fundraising, even though without those things, they can never reach the scale we need to fully address these massive social problems.

Without a systemic way to raise money and also build market awareness of its causes, charities have to pray that a fluke like the Ice Bucket Challenge – a zero-cost, once-in-a-lifetime, spontaneously combusting viral idea – will come their way. This is no way to change the world. Imagine if Tim Cook had to get people to dump ice on their heads in order to bring revenue into Apple – and had to figure out a new idea like that every six months – with an R&D budget for hatching it of precisely zero, to boot. Apple’s revenues are close to $50 billion every quarter – equal to the entire annual budget of the entire U.S. health and human services charitable sector.

The humanitarian sector has been taught to settle for scraps. The $100 million-in-two-months Ice Bucket Challenge is our highest-profile success in years. Compare this to what some companies can make in a day: Apple sells $465 million worth of iStuff every single day. And Anheuser Bush sells $40 million worth of beer daily.

Predictably, the sector is all abuzz now with Ice Bucket fever, and organization after organization is scrambling to figure out how to create its own version of it. That’s not the future. It’s how we’ve always done things. We look for the get-rich-quick-and-easy-scheme because we think that’s what donors want. Meanwhile, we are largely blind to the deep strategic and systemic issues that keep us scrambling for the next Ice Bucket Challenge.

For an audience hell-bent on promoting sustainability, we have a strange addiction to things that are not. The Ice Bucket Challenge is not sustainable, not for ALS and not for the sector as a whole. Zero-cost fundraising ideas that spring up from out of nowhere and require virtually no investment are not sustainable because they rarely happen, and relying on them won’t result in the world we truly seek.

Ice melts. The big play here is a wholesale re-education of how the American public thinks about charity. We did it with pork (“the other white meat”), we did it with gay marriage, and we can do it with charity. We need an Apollo-like goal that challenges America to increase charitable giving from 2% of GDP to 3% of GDP within the next ten years – and this, in large part, means allowing charities to make the investments in growth that they need (and not withholding donations because we disagree about what those mean). That would amount to an extra $160 billion a year. That’s the future of charity.

The Ice Bucket Challenge shows us that the human heart wants to be engaged. Now it’s time to invest in sustaining and increasing that engagement. If you really want to challenge yourself for ALS and for charity at large, challenge the long-held belief that charities should not be able to invest a healthy part of your donation in growth, the same way that beer and cosmetics companies do every day.

September 3, 2014

Uber-Style Talent Poaching Happens in All Industries

How much does it cost you when your employees are chatting with recruiters from other organizations, polishing up their LinkedIn pages, or just networking with employees at rival organizations? The dust-up between two popular app-based car services, Uber and Lyft, has produced some very heated competing calculations of the economic damage of aggressive recruitment.

The Verge reported that Uber sent out brand ambassadors with burner phones and credit cards. Ambassadors “request rides from Lyft and other competitors, recruit their drivers, and take multiple precautions to avoid detection.” The story was picked up by CNN Money, which reported that Lyft’s internal data suggesting 5,560 canceled rides between October 2013 and August 2014. Uber admitted enlisting average passengers: “We even recently ran a program where thousands of riders recruited drivers from many platforms, earning hundreds of dollars in Uber credits for each driver who tries Uber.”

The interesting thing here is not so much the question of whether Uber should curb its aggressive recruitment, but the phenomenon that, for all companies, strategic success increasingly depends on competitive advantage in talent markets as much as in product, service, and brand markets.

Strategic talent constraints are typically described in vast interconnected global supply chains and high-tech knowledge jobs like software engineers and research scientists. Yet, the Uber-Lyft story plays out in the sharing economy for local services. With millions of drivers in every major city, should Lyft and Uber really be concerned about losing a few to their competitors? Yes, because the pool of suitable and motivated drivers for ride-sharing is limited, and drivers are the only face to customers of Uber and Lyft. Lock up the good drivers and you lock up the market. In our book Beyond HR, Peter Ramstad and I described how Corning in the 1990’s could lock up float glass manufacturing in Central Europe by locking in a small population of qualified pivotal engineers. So, this phenomenon isn’t new — but it is increasingly more pervasive, faster, and more varied.

And trying to stop aggressive recruitment is increasingly futile. Jack-in-the-Box employees can chat up McDonalds’ associates during work hours, and engineers from one company strike up relationships with engineers in competitor companies. Zappos got rid of formal job postings in favor of an “Insider” website, for those who “might like to work for Zappos someday” to “sign up, stay in touch, talk to real people with real names and real faces, get to know us and allow us to get to know them.” Microsoft recruited engineers for its Kinect for Windows team using a food truck called The Swinery, serving pepper bacon and toppings such as spray cheese, Sriracha, peanut butter, maple syrup, and chocolate sauce. The truck was parked at lunchtime near the Adobe and Google buildings, and staffed with Microsoft recruiters.

So Uber and Lyft should stop fixating on whether this recruitment activity is unseemly or not, and ask the more pivotal strategic question: Will Lyft or Uber (or someone else) create the best “value proposition” for drivers? That may be happening already. As this spat has played out, Uber and Lyft have both tried to depict themselves as being more devoted to their drivers’ welfare.

All leaders need to ask themselves the same question about their key employees. Just as with the ride-sharing drivers, technology is making alternative jobs easily available to your pivotal talent. Everyone is familiar with Glass Door, Monster.com, and LinkedIn. More recent examples include Mediabistro.com’s AgencySpy channel featuring “Cubes,” a video series that tours actual workers in cubicles at different creative agencies. Plus, your talent will increasingly have alternatives that are more varied and accessible, and go well beyond traditional full-time employment.

In ride-sharing, the drivers can find alternatives and change employers with the tap of a phone. Your pivotal talent today may seem safely insulated in a cocoon of traditional employment and HR practices like rewards, careers, and culture. That’s what taxi and limousine services thought too, just a short time ago. If you’re still focusing on how to stop your employees from using work time to look for other jobs, you’re missing the bigger question: Will your strategy make you the best place for the pivotal talent that embodies your strategic capability?

The Corporate Folklorist’s Credo

Storytelling is key to a strong brand and culture — if it’s done right. Having a corporate folklorist on staff helps to convey an organization’s purpose and values through stories and artifacts. But since it’s a relatively new function, it could use a credo to inform and inspire good work.

Physicians have the Hippocratic Oath, reporters have the Journalist’s Creed, and military recruits have the Oath of Enlistment. Even as a little kid, I had to abide by the Girl Scouts Law (and sell a wagonload of Thin Mints to someone other than my dad) if I wanted to add badges to my Brownie sash.

What would the folklorist’s credo include? Here are some principles that guide my own work, gleaned from market research, social science, and storytelling best practices.

Ask lots of questions. There’s a story in every situation, and it’s the corporate folklorist’s job to find that juicy little nugget of narrative. Ask your interview subjects (executives or worker bees, customers or partners, whomever they may be) open-ended, I’ve-got-no-agenda kinds of questions. Simple prompts like “How did you get started in this work?” or “Tell me about the first time you attempted to do this” can unearth a deep narrative vein that branches off in multiple directions. Then probe for truths that expose underlying values: What did they try and fail before discovering the right path? Where did they find the courage to persist? How did that shape their values later on? Let the phrase “say more about that” weave its magic and then follow that thread as far as it goes.

Trust but verify. Storytellers often have a reputation for stretching the truth (at least in my family), and dramatic license certainly can make a story more lively. But as folklorists, we aren’t writing novels; we’re documenting history. So, facts matter as much as entertainment value. We need to capture the “who, what, where, when, why, and how” of a story and corroborate those claims with multiple sources (eyewitness perspectives, third-party coverage, public records, and so on) for a more complete account. For instance, when my colleagues and I crafted a corporate narrative for a life science firm, we gathered anecdotes from R&D and sales leaders about how their company’s technology had been used by health care firms across the country. But we supplemented their accounts with first-person perspectives obtained directly from customers, along with news coverage about the disease outbreaks that their technology had helped to stem.

Tell the whole truth. Every story has many sides, and the folklorist should represent them all truthfully. Including multiple points of view makes a story well-rounded and believable. What if stories are unflattering to a particular person or product, or to the company as a whole? Tell them anyway, because they may contain lessons that somebody needs to hear. For instance, the history of a major product launch should include the flawed prototypes, missed deadlines, customer complaints, or competitive countermoves that taught the launch team hard lessons and made the product stronger in the end. Learning from that past helps prevent bad decisions on other products and builds confidence that leaders in the company have the skills to handle tough situations in the future.

Make it interesting. Folklore may be an important source of learning, but it won’t get its point across if it’s dull. This is where the art of storytelling comes into play. It’s not a natural language for analytical thinkers, but you can guide them into a dramatic frame of mind and set the stage for a high-impact story by probing for details about a specific moment. A few years ago, I worked with a college educator who explained to me — in a logical (and dull) narrative devoid of conflict — how he had radically restructured his school’s curriculum. He happened to mention that he tested his initial ideas with new students (who loved the changes) and tenured staff (who hated the changes) over a series of meals that led to increasingly heated debate. I saw those events as the turning points in an emotionally charged story that pitted idealistic students against jaded teachers in a battle over the future of education. I then shaped his anecdotes into a classic three-act structure — likeable hero encounters obstacles and emerges transformed — to convert a factual account into an engaging tale.

Share the lore. Folklore is more than content; it’s the corporate conscience. The stories you tell about your company’s mission and values, including successes and failures, reveal the soul of the organization and the character of its people. Don’t allow them to be reduced to meaningless, jargon-filled platitudes. Instead, teach your leaders and employees how to share stories about your values in a personal, emotionally rich way. Companies like Mars, Boeing, and Esri embed storytelling into their culture by training employees to document and present their stories. Nike goes a step further by cataloguing stories about their maxims in video form. At Duarte, we ask functional teams to stand up at all-staff meetings and tell stories about situations when they embodied one of our core values.

Regardless of what form your lore takes, the corporate folklorist role demands rigor. As Voltaire and Spiderman’s Uncle Ben said, “With great power comes great responsibility.” It’s time we took a pledge to use our power well.

Learn from Your Analytics Failures

By far, the safest prediction about the business future of predictive analytics is that more thought and effort will go into prediction than analytics. That’s bad news and worse management. Grasping the analytic “hows” and “whys” matters more than the promise of prediction.

In the good old days, of course, predictions were called forecasts and stodgy statisticians would torture their time series and/or molest multivariate analyses to get them. Today, brave new data scientists discipline k-means clusters and random graphs to proffer their predictions. Did I mention they have petabytes more data to play with and process?

While the computational resources and techniques for prediction may be novel and astonishingly powerful, many of the human problems and organizational pathologies appear depressingly familiar. The prediction imperative frequently narrows focus rather than broadens perception. “Predicting the future” can—in the spirit of Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational—unfortunately bring out the worst cognitive impulses in otherwise smart people. The most enduring impact of predictive analytics, I’ve observed, comes less from quantitatively improving the quality of prediction than from dramatically changing how organizations think about problems and opportunities.

Ironically, the greatest value from predictive analytics typically comes more from their unexpected failures than their anticipated success. In other words, the real influence and insight come from learning exactly how and why your predictions failed. Why? Because it means the assumptions, the data, the model and/or the analyses were wrong in some meaningfully measurable way. The problem—and pathology—is that too many organizations don’t know how to learn from analytic failure. They desperately want to make the prediction better instead of better understanding the real business challenges their predictive analytics address. Prediction foolishly becomes the desired destination instead of the introspective journey.

In pre-Big Data days, for example, a hotel chain used some pretty sophisticated mathematics, data mining, and time series analysis to coordinate its yield management pricing and promotion efforts. This ultimately required greater centralization and limiting local operator flexibility and discretion. The forecasting models—which were marvels—mapped out revenues and margins by property and room type. The projections worked fine for about a third of the hotels but were wildly, destructively off for another third. The forensics took weeks; the data were fine. Were competing hotels running unusual promotions that screwed up the model? Nope. For the most part, local managers followed the yield management rules.

Almost five months later, after the year’s financials were totally blown and HQ’s credibility shot, the most likely explanation materialized: The modeling group—the data scientists of the day—had priced against the hotel group’s peer competitors. They hadn’t weighted discount hotels into either pricing or room availability. For roughly a quarter of the properties, the result was both lower average occupancy and lower prices per room.

The modeling group had done everything correctly. Top management’s belief in its brand value and positioning excluded discounters from their competitive landscape. Think this example atypical or anachronistic? I had a meeting last year with another hotel chain that’s now furiously debating whether Airbnb’s impact should be incorporated into their yield management equations.

More recently, a major industrial products company made a huge predictive analytics commitment to preventive maintenance to identify and fix key components before they failed and more effectively allocate the firm’s limited technical services talent. Halfway through the extensive—and expensive—data collection and analytics review, a couple of the repair people observed that, increasingly, many of the subsystems could be instrumented and remotely monitored in real time. In other words, preventive maintenance could be analyzed and managed as part of a networked system. This completely changed the design direction and the business value potential of the initiative. The value emphasis shifted from preventive maintenance to efficiency management with key customers. Again, the predictive focus initially blurred the larger vision of where the real value could be.

When predictive analytics are done right, the analyses aren’t a means to a predictive end; rather, the desired predictions become a means to analytical insight and discovery. We do a better job of analyzing what we really need to analyze and predicting what we really want to predict. Smart organizations want predictive analytic cultures where the analyzed predictions create smarter questions as well as offer statistically meaningful answers. Those cultures quickly and cost-effectively turn predictive failures into analytic successes.

To paraphrase a famous saying in a data science context, the best way to predict the future is to learn from failed predictive analytics.

Predictive Analytics in Practice

An HBR Insight Center

A Predictive Analytics Primer

Nate Silver on Finding a Mentor, Teaching Yourself Statistics, and Not Settling in Your Career

Beware Big Data’s Easy Answers

Who’s Afraid of Data-Driven Management?

Your Company’s Purpose Is Not Its Vision, Mission, or Values

We hear more and more that organizations must have a compelling “purpose” — but what does that mean? Aren’t there already a host of labels out there that describe organizational direction? Do we need yet another?

I think we do, and I’ve pulled together a typology of sorts to help distinguish all these terms from one another.

A vision statement says what the organization wishes to be like in some years’ time. It’s usually drawn up by senior management, in an effort to take the thinking beyond day-to-day activity in a clear, memorable way. For instance, the Swedish company Ericsson (a global provider of communications equipment, software, and services) defines its vision as being “the prime driver in an all-communicating world.”

There’s also the mission, which describes what business the organization is in (and what it isn’t) both now and projecting into the future. Its aim is to provide focus for management and staff. A consulting firm might define its mission by the type of work it does, the clients it caters to, and the level of service it provides. For example: “We’re in the business of providing high-standard assistance on performance assessment to middle to senior managers in medium-to-large firms in the finance industry.”

Values describe the desired culture. As Coca-Cola puts it, they serve as a behavioral compass. Coke’s values include having the courage to shape a better future, leveraging collective genius, being real, and being accountable and committed.

If values provide the compass, principles give employees a set of directions. The global logistics and mail service company TNT Express illustrates the difference in its use of both terms. TNT United Kingdom, the European market leader, lists “customer care” among nine key principles, describing it as follows: “Always listening to and building first-class relationships with our customers to help us provide excellent standards of service and client satisfaction.” TNT’s Australian branch takes a different approach: Rather than outline detailed principles, it highlights four high-level “core values,” including: “We are passionate about our customers.” Note the lighter touch, the broader stroke.

So how does purpose differ from all the above, which emphasize how the organization should view and conduct itself?

Greg Ellis, former CEO and managing director of REA Group, said his company’s purpose was “to make the property process simple, efficient, and stress free for people buying and selling a property.” This takes outward focus to a whole new level, not just emphasizing the importance of serving customers or understanding their needs but also putting managers and employees in customers’ shoes. It says, “This is what we’re doing for someone else.” And it’s motivational, because it connects with the heart as well as the head. Indeed, Ellis called it the company’s “philosophical heartbeat.”

For other examples of purpose, look at the financial services company ING (“Empowering people to stay a step ahead in life and in business”), the Kellogg food company (“Nourishing families so they can flourish and thrive”) and the insurance company IAG (“To help people manage risk and recover from the hardship of unexpected loss”).

If you’re crafting a purpose statement, my advice is this: To inspire your staff to do good work for you, find a way to express the organization’s impact on the lives of customers, clients, students, patients — whomever you’re trying to serve. Make them feel it.

You Perform Better When You’re Competing Against a Rival

A runner can be expected to finish a 5 kilometer race about 25 seconds faster, on average, if a personal rival is also running, according to a study by Gavin J. Kilduff of New York University of 184 races conducted by a running club. Although past research has shown that competition imposed on strangers can be demotivating, Kilduff’s findings suggest that longstanding personal rivalries between similar contestants can boost both motivation and performance.

How to Market Test a New Idea

“So,” the executive sponsor of the new growth effort said. “What do we do now?”

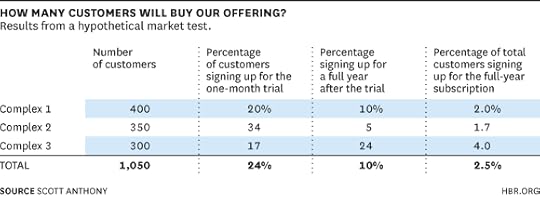

It was the end of a meeting reviewing progress on a promising initiative to bring a new health service to apartment dwellers in crowded, emerging-market cities. A significant portion of customers who had been shown a brochure describing the service had expressed interest in it. But would they actually buy it? To find out, the company decided to test market the service in three roughly comparable apartment complexes over a 90-day period.

Before the test began, team members working on the idea had built a detailed financial model showing that it could be profitable if they could get 3% of customers in apartment complexes to buy it. In the market test, they decided to offer a one-month free trial, after which people would have the chance to sign up for a full year of the service. They guessed that 30% of customers in each complex would accept the free trial and that 10% of that group would convert to full-year subscribers.

They ran the test, and as always, learned a tremendous amount about the intricacies of positioning a new service and the complexities of actually delivering it. They ended the three months much more confident that they could successfully execute their idea, with modifications of course.

But then they started studying the data, which roughly looked as follows:

Overall trial levels were lower than expected (except in Complex 2); conversion of trials to full year subscribers were a smidge above expectations (and significantly higher in Complex 3); but average penetration levels fell beneath the magic 3% threshold.

What were the data saying? On the one hand, the trial fell short of its overall targets. That might suggest stopping the project or, perhaps, making significant changes to it. On the other hand, it only fell five customers short of targets. So, maybe the test just needed to be run again. Or maybe the data even suggest the team should move forward more rapidly. After all, if you could combine the high rate of trial in Complex 2 with the high conversion rate of Complex 3…

It’s very rare that innovation decisions are black and white. Sometimes the drug doesn’t work or the regulator simply says no, and there’s obviously no point in moving forward. Occasionally results are so overwhelmingly positive that it doesn’t take too much thought to say full steam ahead. But most times, you can make convincing arguments for any number of next steps: keep moving forward, make adjustments based on the data, or stop because results weren’t what you expected.

The executive sponsor felt the frustration that is common to companies that are used to the certainty that tends to characterize operational decisions, where historical experience has created robust decision rules that remove almost all need for debate and discussion.

Still, that doesn’t mean that executives have to make decisions blind. Start, as this team did, by properly designing experiments. Formulate a hypothesis to be tested. Determine specific objectives for the test. Make a prediction, even if it is just a wild guess, as to what should happen. Then execute in a way that enables you to accurately measure your prediction.

Then involve a dispassionate outsider in the process, ideally one who has learned through experience how to handle decisions with imperfect information. So-called devil’s advocates have a bad reputation among innovators because they seem to say no just to say no. But someone who helps you honestly see weak spots to which you might be blind plays a very helpful role in making good decisions

Avoid considering an idea in isolation. In the absence of choice, you will almost always be able to develop a compelling argument about why to proceed with an innovation project. So instead of asking whether you should invest in a specific project, ask if you are more excited about investing in Project X versus other alternatives in your innovation portfolio.

And finally, ensure there is some kind of constraint forcing a decision. My favorite constraint is time. If you force decisions in what seems like artificially short time period, you will imbue your team with a strong bias to action, which is valuable because the best learning comes from getting as close to the market as possible. Remember, one of your options is to run another round of experiments (informed of course by what you’ve learned to date), so a calendar constraint on each experiment doesn’t force you to rush to judgment prematurely.

That’s in fact what the sponsor did in this case — decided to run another experiment, after first considering redirecting resources to other ideas the company was working on. The team conducted another three-month market test, with modifications based on what was learned in the first run. The numbers moved up, so the company decided to take the next step toward aggressive commercialization.

This is hard stuff but a vital discipline to develop or else your innovation pipeline will get bogged down with initiatives stuck in a holding pattern. If you don’t make firm decisions at some point, you have made the decision to fail by default.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers