Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1370

September 8, 2014

The Innovator’s Question: What Would Fosbury Do?

When 16-year-old Dick Fosbury first attempted the high jump in high school track-and-field, he couldn’t even qualify for his meets. With a bad back, bad feet, and an easily worn-out body, Dick was hardly champion material. He also had a terrible habit of jumping and landing the wrong way, to the dismay of his coaches and probably his mother.

Five years later, he broke high jump records, winning gold at the 1968 Olympic Games by

clearing 7’ 4”.

At the time, top competitors used what was known as the “straddle” technique. They’d run straight and clear the bar face-down, kicking pronated legs up and over in succession. At the Olympics, Fosbury shocked the world by running at the bar diagonally, jumping off the “wrong” foot, and arching himself over the bar backwards—resulting in implausible height and the record.

By the next Olympics, the majority of competitors were jumping with Fosbury’s back-first technique. Today, it’s rare to see a high jumper not use the “Fosbury flop.”

Fosbury’s breakthrough took his sport to a new level. He did it not by working harder or developing bigger muscles than his competitors, but by recognizing that a convention of his sport was not a rule.

The same pattern is present in breakthrough innovations in business. Dramatic progress in both macro and micro environments happens when players break rules that aren’t actually rules – in other words, when they rethink assumptions.

Psychologists call this “lateral thinking.” As the man who coined the phrase, Edward de Bono, explains, “In most real life situations the pieces are not given, we just assume they are there. We assume certain perceptions, certain concepts and certain boundaries. Lateral thinking is concerned not with playing with the existing pieces but with seeking to change those very pieces.”

We got printing presses and express trains and the American Revolution from lateral thinking. More amazing, we got stealth jets and digital projectors and sticky notes from lateral thinking inside existing enterprises. Gmail was once a one-man side project. Tipsy programmers developed Facebook’s ubiquitous “Like” button during a hackathon. They each approached the challenges in their businesses sideways, and created a new game for their competitors to catch up to.

The dilemma for most businesses is how to encourage unconventional thinking that leads to such breakthroughs while minimizing risk. Starbucks doesn’t want lateral-thinking baristas bringing bourbon from home and spiking lattes.

Unless bourbon lattes start selling.

And that’s the problem. We who’ve gotten far by playing by the rules or even writing our own as entrepreneurs have an easy time carving our assumptions about our businesses into stone. We become increasingly entrenched in “this is what matters” and “that’s the way it’s done” the longer we invest.

The key to flipping that script, to encouraging lateral thinking that doesn’t lead to liquor-license fines or bankruptcy—or turn a company into Enron—is to be honest with ourselves about what hard boundaries actually exist. And even then, we ought to spend time questioning those boundaries as well. The only hard line we ought to draw, at the end of the day, is a question that has little to do with profits: Is it ethical?

Fosbury recognized that there was no rule in his sport other than “clear the bar” and “jump off of one foot.” He could run from any angle, jump from either foot, twist and flail and land however he wanted. But his peers assumed that the direct approach was the “right” approach, and therefore only made incremental improvement.

How did Fosbury convince his nervous coaches to let him use his unorthodox technique? With cold data. He practiced his flop on his own, then showed up to practice with higher scores. It’s tough for a boss to be too mad about better results.

When Ben Franklin was a young man working for his brother’s print shop, his brother wouldn’t print his writing. So Ben stayed up late writing essays under a pseudonym, slipping them under the print shop door. He did this extra work on his own time, and his essays soon became a colonial hit. He bent the rules (though writing under a pseudonym was common at the time, he disobeyed his brother’s wishes), but his brother couldn’t deny their critical reception and benefit to the newspaper.

The calling of an entrepreneur is to forge her own path despite the obstacles, and true intrapreneurs have that mindset as well. Would Ben Franklin have put those letters under the door if they were garbage? No. Neither would he have written them during work hours. At a corporation like 3M or Google where time for experimentation is allotted, perhaps he would have. But in the absence of such encouragement, he built his own innovation on his own time.

“I use the phrase of responsibly ‘irresponsible’,” says Astro Teller, director of Google’s innovation lab, Google[x], which has produced Glass and Internet-bearing balloons called Loon. “It can’t just be Peter Pans. But they can’t just be PhDs. It’s Peter Pans with PhDs that’s powerful.”

The average business isn’t set up to encourage (or reward) rule-bending. Slippery slope analogies abound. Teller says, “It’s got nothing to do with anything but bravery.” And if the organization doesn’t have it, the intrapreneur can.

On a practical level, the brave intrapreneur will do well to ask herself a few starter questions to kickstart lateral thinking in her work:

What are the assumptions inherent to this question?

How could we change the question?

What if we couldn’t take the conventional approach?

What if we had to do this for 100x cheaper?

What if we had to do this 10x better?

Then there’s my personal favorite: What would Fosbury do?

How to Get the Most Out of Your Executive Education

My summer short course executive education “students” are terrific. They come from all over the world and radically different industries. They’re entrepreneurs as well as intra-preneurs inside established organizations. They’re motivated, dedicated and demanding—as they should be. They authentically want to be better innovators. I’m grateful for their commitment and how much I learn from them.

The single most important thing I’ve learned over a decade of summer studies is that cultivating new capability is more important than better communicating one’s expertise. These mid-career leaders and managers aren’t just seeking greater knowledge, they want to acquire greater skill. But this sensibility isn’t just confined to the classroom— the desire for getting better at getting better is a global phenomenon. I’ve discovered that the summer short course is a great laboratory for learning how human capital revitalizes, renews and retools. Here’s the seven lessons managers and executives should consider as they invest in themselves:

1) Organizational impact matters as much as professional development. At mid-career, if you receive any kind of professional development, it has to have immediate impact on your organization. The course content and curricula need to clearly connect with what matters to your colleagues, clients and customers. A better view from 30 thousand feet or a firmer grasp of technology may exhilarate but will that translate to meaningful organizational influence within 100 days?

2) Keener introspection facilitates greater external influence. I am no longer surprised when students email or share that the session forced them to become more self-aware. Being able to do more pushes people to re-evaluate what they really want to do. In my class, people revisited what kind of innovators they wanted to be and what kind of innovation they wanted to encourage. The surer their insight into their own innovation priorities, the more clearly they could communicate and motivate. Whether you spend time in a classroom or not, the message here is to look for opportunities to rethink not just what you can do, but what you want to do. As you increase capability in one domain, look for adjacencies and complements.

3) Rethink, repurpose and renew what we’re already doing. Revolution and new paradigms weren’t top priorities for my mid-career students. The primary opportunity was revisiting the fundamentals of everyday projects and processes. Instead of starting from scratch, my students sought innovative ways to leverage what their organizations were already doing. For example, their company already prototyped. How might simple changes in the prototyping process yield disproportionately greater value? In the same way, you should be looking for similar opportunities where small tweaks result in creating and capturing new value. Don’t make “reinvention” your focus.

4) See something differently. The classroom thrust was empowering students to individually and collectively “see” innovation in a different way. Students wanted novel perspectives and points of view that let them observe or appreciate something in a potentially valuable new way. Just as a microscope or MRI scanner offers new eyes, a different framework similarly invites a new vision. But seeing different is not enough; that vision has to be communicated. This is where social media can play an important role. How will you share not just a vision but a visualization?

5) Do something different. Effective leaders and managers can’t simply be visionaries and voyeurs. Actions speak louder than words. The cultivation of capability means that “seeing differently” has to be translated into tangible actions. In our class, that meant collaboratively designing simple models, prototypes and experiments. Turning a novel “point of view” into a testable innovation hypothesis represented a different way of exploring value creation. But that “do something different” has to be made accessible and understandable. Simple exercise: Is there an “app” or “calc” that could have an impact?

6) Measure the difference. Seeing and doing something different is the essence of new capability creation. But those differences need to be credibly measured. How do those differences make us more efficient or effective? How might our customers or clients experience that difference? It’s one thing to claim a new capability; it’s quite another to rigorously measure it. Serious executive education students are always looking for new ways to measure impact, influence and improvement. Similarly, whether you’ve learned in a classroom or on the job, what is the metrics conversation you want to facilitate? What gets measured gets managed. Incentives don’t follow too far behind.

7) Build an arc. What’s next for high impact professional development? How often are you asking yourself, or your boss, that question?

The lesson I take away from listening to, working with and learning from these students is that professional development requires a commitment to interpersonal development. That is, the capabilities we cultivate aren’t just about getting better at getting better—they’re about getting our colleagues and collaborators better at getting better, as well.

What You Don’t Know About Sales Can Hurt Your Strategy

The goal of strategy is profitable growth, meaning economic value above the firm’s cost of capital. There are basically four ways to create that value: (1) invest in projects that earn more than their cost of capital; (2) increase profits from existing capital investments; (3) reduce the assets devoted to activities that earn less than their cost of capital; and (4) reduce the cost of capital itself.

In my experience, most CEOs, CFOs, and other C-suite executives involved in strategy formulation know these finance basics. (Or, they learn fast after a few investor meetings.) But far fewer understand and operationalize the core sales factors that materially affect each value creation lever.

Most projects and investment initiatives in firms are driven by revenue-seeking activities with customers. Hence, the customer-selection criteria of sales managers, and call patterns of sales reps, directly impact the first value-creation lever: which projects the firm invests in. But most sales compensation plans focus purely on volume incentives. In effect, the C-suite is saying to salespeople: “go forth and multiply!” That’s precisely what they do, selling to any customers and, in the process, generating a motley mix of investment initiatives in the selling firm. Soon, it really doesn’t matter what your strategic planning documents say. Your real “strategy” is the collection of investments made via this ad hoc process.

To increase profits from existing investments, the interactions between sales and other functions is crucial because those interactions accrete costs, time, and on-going asset utilization patterns in organizations. Consider the order cycle in most businesses. For the seller, an order typically touches multiple functions as it moves from a customer’s request for specifications or quote to a purchase and through any post-sale service activities such as delivery and installation. The process starts with a sale—as the old saying goes, “nothing happens until you make a sale”–and sales is involved in most of these activities, if only because it’s the sales rep who usually fields the customer’s questions or complaints and who then interacts with other functions to respond.

Smartly reducing assets devoted to activities that earn less than their cost of capital requires good links with evolving market realities. (My previous article emphasized how and why these links are broken in many companies.) But creating value also requires senior executives to get more serious and knowledgeable about performance-management issues in sales. Without that understanding of how sales hiring, incentives, organization, and training affect field behavior in your company, asset redeployment becomes an academic exercise that does not affect the actions of those using unproductive assets. Or, worse, C-suite initiatives become an unwitting impediment to the use of assets that in fact remain essential to profitable selling.

It may seem that sales has little impact on the fourth value-creation lever, the firm’s cost of capital. Isn’t that a function of risk parameters and the debt-to-equity ratio? (Call the investment bankers for advice, since they’ve shown how smart they are in managing their risks and leverage.) But consider the basics. Financing needs are in large part driven by the cash on hand and the working capital required to conduct and grow the business. Most often, the single biggest driver of cash-out and cash-in is the selling cycle. Accounts payables accumulate during selling, and accounts receivables are largely determined by what’s sold, how fast, and at what price. That’s why increasing close rates and accelerating selling cycles is a strategic issue and not only a sales task.

Interactions with customers affect all core elements of enterprise value and, in many firms the sales force is the sum of those interactions. If the C-suite can’t make these connections between sales and strategy, then attempts to increase stock price or valuations are at best limited and, at worst, going down the wrong path. For example, as a leader, you can worry prudently and diligently all you want about disruptive innovations in your industry, but you need a sales channel aligned with strategy to do something about it. Or as a character in a John le Carre novel says, “A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world.”

Strategic Humor: Cartoons from the October 2014 Issue

Enjoy these cartoons from the October issue of HBR, and test your management wit in the HBR Cartoon Caption Contest. If we choose your caption as the winner, you will be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free Harvard Business Review Press book.

“Ever since I hacked into that retail group, I can’t get off its mailing list.”

John Klossner

“They’ve passed their peak performance years, but they have access to fresh coffee and plenty of room to roll around.”

Teresa Burns Parkhurst

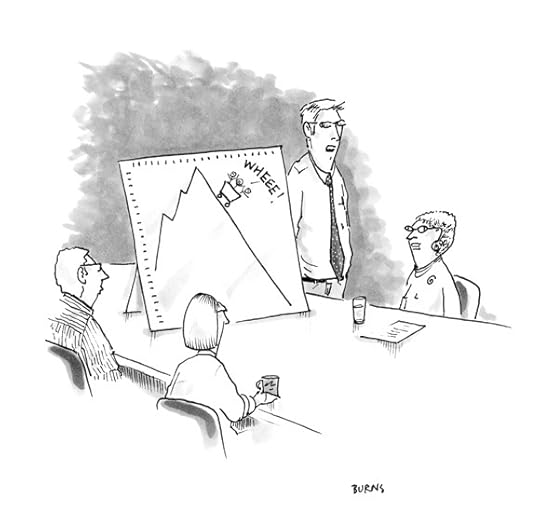

“I thought it might help.”

Teresa Burns Parkhurst

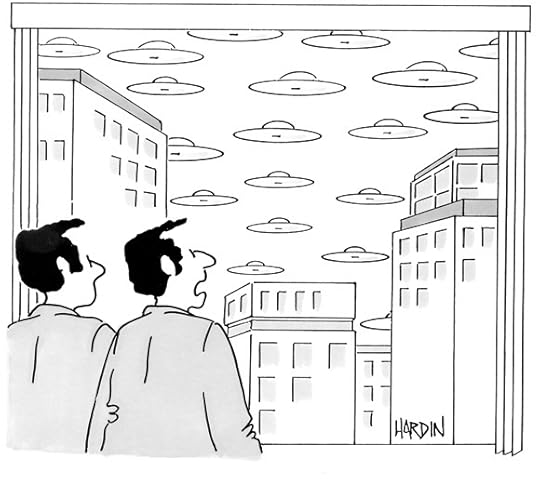

“Good heavens! What if they’ve come seeking market share?”

Patrick Hardin

And congratulations to our October caption contest winner, Tony Vance of Millersville, Maryland. Here’s his winning caption:

“So that’s where they hide the silent partner.”

Cartoonist: Crowden Satz

NEW CAPTION CONTEST

Enter your caption for this cartoon in the comments below—you could be featured in an upcoming magazine issue and win a free book. To be considered for this month’s contest, please submit your caption by September 23.

Cartoonist: Martin Bucella

If Your Kids Get Free Health Care, You’re More Likely to Start a Company

Starting a business is risky enough in the best of circumstances. Most new ventures fail, and the prospect of forgoing a salary is enough to keep many would-be entrepreneurs from taking the plunge.

But think about how much harder it would be if your child had a health condition, and you couldn’t get her insurance if you struck out on your own.

That’s less of a problem in the U.S. than it was a few years ago, thanks to Obamacare, but until recently it was a very real conundrum. So does the extension of publicly provisioned health insurance prompt more people to start companies? That’s the question asked by a paper released earlier this year by Gareth Olds of Harvard Business School.

Olds analyzed Census data from before and after the passage of the Children’s Health Insurance Program in the U.S. in 1997 to assess its impact on entrepreneurship. CHIP, or SCHIP as it was previously known, provides publicly funded health insurance to children whose families don’t qualify for Medicare, but whose incomes still fall below a cutoff (typically around 200% of the federal poverty line).

His results suggest that the policy did significantly increase business creation by those families affected. The self-employment rate for CHIP recipients increased from just under 15% of those eligible to over 18%. That amounts to an a 23% increase. The rate of ownership of incorporated businesses — a better proxy for sustainable, growth entrepreneurship — increased even more dramatically, from 4.3% to 5.8%, an increase of 31%.

What about all the other factors that might skew this sort of analysis? Olds used several quasi-experimental statistical methods in his research to control for such variables. The basic intuition behind his methods is that a family just above the CHIP cutoff isn’t all that different from a family just below it. Whether you make 199% of the poverty line or 201% doesn’t matter for much, except whether or not you’ll be able to enroll in the program. With that in mind, his methods zero in on this sub-group, in order to confirm that the policy actually caused the increase in firm creation.

The mechanism by which Olds believes CHIP boosts entrepreneurship is relatively straightforward: it reduces the risk of “consumption shocks,” i.e. the possibility of having to pay out a large chunk of cash unexpectedly for a child’s illness. Lower the risk and more people start companies.

Though it may seem counterintuitive given the political rhetoric around social insurance and economic growth, Olds’ is not the only research to suggest that welfare programs can promote entrepreneurship. Previous research has found that American self-employment rates jump at 65. Why is 65 a better age to start a company than 64? Because you qualify for health insurance through Medicare.

All of this serves as a reminder that bigger government needn’t discourage entrepreneurship and risk-taking. The relationship between the two ultimately depends on what government chooses to spend money on.

The final takeaway from Olds’ work is just how many business owners do depend on public programs like CHIP. “12% of households with incorporated businesses report enrollment in a public program,” he writes, not even counting Social Security, Medicare, or veterans benefits. And “disproportionately more entrepreneurs are receiving public healthcare benefits than would be expected based on their income alone.”

Overall, though, entrepreneurs still hail from disproportionately well-off families. The lesson from Olds’ paper is that starting a business doesn’t have to be a risk only wealthy people can afford to take — and the government can help.

Have Economists Been Captured by Business Interests?

To be an economist, you kind of have to believe that people respond to economic incentives. But when anyone suggests that an economist’s views might be shaped by the economic incentives he or she faces, that economist tends to get bent out of shape. This happened perhaps most famously in the documentary Inside Job, in which filmmaker Charles Ferguson posed his questions to the likes of Glenn Hubbard and Rick Mishkin as tendentiously as possible in order to spark just such reaction. But it’s actually pretty common to hear economists saying things like — this is from the usually no-nonsense John Cochrane of the University of Chicago — “the idea that any of us do what we do because we’re paid off by fancy Wall Street salaries or cushy sabbaticals at Hoover is just ridiculous.”

It is perhaps ridiculous to suggest that economists do what they do only because of the prospect of consulting gigs or think-tank stints. Economists are human beings, with diverse motivations. But it is definitely ridiculous to suggest that such rewards have no impact at all. Economists are human beings, and human beings respond to incentives. Right, economists?

Happily, Luigi Zingales, a colleague of Cochrane’s at Chicago’s Booth School of Business, is trying to correct his discipline’s blind spot by examining the economics of economists’ opinions. He does this in a chapter in the Tobin Project book Preventing Regulatory Capture, published last December, that has been trickling into the public’s consciousness mainly in this working paper format (there’s also a short version in the Booth School’s Capital Ideas magazine, but the full paper is so entertaining that you really should download it, if you’re into this kind of stuff). The economic lens Zingales uses is regulatory capture, the idea expounded by economists Mancur Olson and George Stigler in the 1960s and early 1970s that, as Zingales puts it, “regulators can be influenced and not all groups have equal opportunities in influencing them.”

Zingales looks at the ways in which economists can be influenced and who might influence them, then subjects his notions to an empirical test: Are there discernible patterns in what kinds of economists think corporate executives are overpaid and what kinds think they’re paid fairly? (He also examines views on whether executive pay should be more or less sensitive to corporate performance, but I don’t want to overcomplicate things here.) The answer turns out to be yes. Economists with appointments at business schools are more likely to give a thumbs up to executive pay than those without — and this even after controlling for “the Bebchuk effect” caused by the extreme productivity of executive pay critic Lucian Bebchuk, who teaches law, economics, and finance at Harvard Law School. Economists on corporate boards are more approving of current pay practices than those who aren’t. And articles in economics and management journals are more likely to be pro-pay than those in law or finance journals.

None of this is proof that the individual economists in question have been corrupted, Zingales writes. Maybe economists who sit on corporate boards simply understand executive pay better than those who don’t. But the evidence does suggest that, among other things “the optimal strategy for a junior faculty who works on executive compensations [sic] and wants to maximize her chances to get tenure is to write articles that show that the level of compensation is appropriate.” Which sounds a lot like capture.

What is to be done about this? Zingales thinks media attention is an important force, and lauds Inside Job for “curbing the potential effects of capture.” He also has some specific suggestions about the management of economics journals, the ways in which economists go about acquiring private data, and forcing economists to be more accountable for what they say in expert-witness testimony and elsewhere. Also, as an immigrant from Italy with a charming but distinct accent, he thinks there should be more economists like him:

Ceteris paribus a foreign economist with a thick foreign accent is less likely to be asked to be an expert witness or to find a job in the industry, except in very quantitative (and generally not very lucrative) positions. These economists are less likely to cater to business interests.

What Zingales doesn’t call for is any kind of blanket retreat by economists from consulting and expert witnessing and board memberships. Which is a good thing, I think. One of the reasons why economics rocketed past the other social sciences in influence and prestige over the past 75 years was because so many economists involved themselves in the worlds they studied. That has surely led to some amount of capture by outside interests, but it also seems to have counteracted the natural academic tendency toward insularity and obscurity. Lots of economists study things of direct relevance to business leaders and government policy-makers. We wouldn’t really want to take away their incentive to do that, would we?

Incorrupt Nations Fare More Poorly in the Olympics

According to an analysis of the 2012 Summer Olympics, nations within the top 15% to 20% in controlling corruption achieved lower shares of medals, says Todd Potts of Indiana University of Pennsylvania. A possible explanation, he says, is that nations such as Sweden and the UK, with high control of corruption (corruption, in this context, meaning the exercise of public power for private gain, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interests), appear to have lower rates of doping among their athletes, as evidenced by lower rates of suspensions and disqualifications for doping violations.

We Can’t Always Control What Makes Us Successful

The 2002 movie Minority Report told the story of a future in which law enforcement could tell who would commit crimes in the future. The police then arrested those people before they could commit the crimes.

A good deal of work in the social sciences tries to do the same thing, albeit without clairvoyance or Tom Cruise. The idea is to identify the attributes of individuals that cause them to act in certain ways in the future: What causes some students to do well in school, why are some patients bad at taking their medicine, and, for our purposes, what causes some candidates to perform well in jobs?

Most of the studies in the workplace have been done by psychologists. Despite the new hype about big data as a means to build such models, psychologists have been studying questions like what predicts who will be a good performer since WWI. Over the generations, we’ve gotten used to the fact that tests most applicants don’t understand, examining attributes such as personality, determine who gets hired.

Of course, there are lots of other tests that are not as well known but sometimes used by HR in the workplace, such as “integrity” tests that try to determine who will steal at work, something very much like the Minority Report movie.

But a few things have changed with the rise of big data. The psychologists have lost control of the effort. It’s now done by economists, data engineers, IT operatives, and anyone who has access to the data. It also migrated outside the firm to an ever-growing crowd of vendors who offer enticing claims about the benefits of their prediction software. Rather than giving tests, the new studies look for associations with background data. The better ones worry about actual causation.

As data has gotten easier to access and software has made analyzing it simpler, we can examine every aspect of employee behavior. My colleague Monika Hamori and I did a study of what determines whether executives say “yes” when headhunters call to recruit them; in work underway, a colleague recently identified the attributes of individuals who get laid off in a consulting firm based on email traffic; another is looking at the attributes of supervisors that predict which ones do the best job of training. You name it, it’s being studied now.

The promise of big data means that we are likely to get better at prediction in the future. Even a small improvement in predictive accuracy can be worth millions to companies that hire tens of thousands of people per year. These tools are especially attractive to retail and service companies because they have so many employees and such high turnover, which means they are hiring all the time.

Here’s the issue, which is not new but it has grown more important with the developments above: Many of the attributes that predict good outcomes are not within our control. Some are things we were born with, at least in part, like IQ and personality or where and how we were raised. It is possible that those attributes prevent you from getting a job, of course, but may also prevent you from advancing in a company, put you in the front of the queue for layoffs, and shape a host of other outcomes.

So what, if those predictions are right?

First is the question of fairness. There is an interesting parallel with the court system where predictions of a defendant’s risk of committing a crime in the future are in many states used to shape the sentence they will be given. Many of the factors that determine that risk assessment, some of which include things like family background that are beyond the ability of the defendant to control. And there has been pushback: is it fair to use factors that individuals could not control in determining their punishment?

Some of that fairness issue applies to the workplace as well. Even if it does predict who will steal, what if, for example, being raised by a single parent meant that you did not get a job, all other things being equal?

Second is the effect on motivation. If I believe that decisions about my employment such as promotions, layoff decisions, and other outcomes are heavily influenced by factors that I cannot control, such as personality or IQ, how does this affect my willingness to work hard?

And finally, unlike the Minority Report movie, our predictions in the workplace are nowhere close to perfect. Many times they are only a bit more accurate than chance, and they explain only a fraction of the differences in behavior of people.

The field of psychology has long thought about the ethical issues and moral consequences of their tests. At least as of yet, the new big data studies and the vendors selling them have not. How we balance the employer’s interest in getting better employees and making more effective workplace decisions with broader concerns about fairness and unintended consequences is a pretty hard question.

Predictive Analytics in Practice

An HBR Insight Center

Predict What Employees Will Do Without Freaking Them Out

To Make Better Decisions, Combine Datasets

Learn from Your Analytics Failures

A Predictive Analytics Primer

September 5, 2014

It’s Not the How or the What but the Who: Succeed by Surrounding Yourself with the Best

Are you surrounding yourself with the right people?

Yes, your success depends on your own performance. But have you thought about how those around you affect your performance? Do they strengthen or weaken it? Help or hinder your progress?

In his insightful book It’s Not the How or the What but the Who (a phrase adapted from Amazon’s Jeff Bezos), renowned global talent management expert Claudio Fernández-Aráoz explains why people’s decisions–choices about friends, spouses, employees, partners, and mentors–are more important than any other. To thrive, you need the best people in your corner and on your team. Yet few people know how to do that well.

In this interactive Harvard Business Review webinar, Fernández-Aráoz offers wisdom and practical advice on how to “get people right” in a more systematic way.

5 Essential Communications Skills to Catapult Your Career

Developing great communication skills is a key to professional success.

Communication skills have always been instrumental for senior leaders. But they’ve become equally important for aspiring leaders.

Professionals today are expected to show polished “executive” communications skills earlier in their careers, to a wider network of audiences. Getting work done through distributed teams, virtual workforces, and flattened hierarchies requires having outstanding strategic communications abilities. Yet, these skills are rarely taught–if at all–until professionals are already in senior management.

In this interactive Harvard Business Review webinar, communications expert Kristi Hedges teaches aspiring executives five must-have communication skills: creating an intentional presence; being able to get buy-in; delivering executive briefings; connecting with distributed teams through virtual leadership; and giving and receiving direct feedback.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers