Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1367

September 12, 2014

The Economic Advantages of an Independent Scotland

If its voters choose independence next week, Scotland will join the ranks of the world’s small, affluent countries. Over the past couple of decades, that’s been a good club to belong to. As Gideon Rachman put it in the FT in 2007:

This is the age of the small state. Look at almost any league table of national welfare and small countries dominate.

Things have gotten a little more complicated since then. (Rachman in 2009: “Big is beautiful again.”) Several small nations suffered brutally from the financial crisis and subsequent Euro mess: Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Portugal.

Still, several of the emerging bigs (Brazil, India, Russia) have since run into economic headwinds too. And small countries remain overrepresented near the top of lists of the world’s most affluent, most competitive, healthiest, and smartest nations.

So it’s not crazy to think that Scotland, which on its own would be a country of 5.3 million people with a GDP per capita ranking between Finland’s and Belgium’s (that’s counting offshore oil revenue), could be an economic success. But it’s not guaranteed, either.

What has made small countries so economically successful over the past few decades is less their smallness than the ways they’ve taken advantage of it. David Skilling, a former New Zealand government official and McKinsey consultant who now advises small-country governments and companies from a base in Singapore, has spent as much time thinking and writing about the strengths and weaknesses of small states as anybody. In a 2012 paper that should be required reading in Scotland, he lists two main characteristics of successful small states:

They’re cohesive, and thus able to make policy decisions quickly and stick with them.

They tend to make good policy decisions, in part because they’re very aware of the world around them and what it takes to compete in it.

In polls, Scotland appears evenly split on whether to leave the United Kingdom. That doesn’t look very cohesive. But one of the forces that’s been driving Scotland toward possible separation has been the divergence between Scottish political priorities and those of the rest of the UK. The ruling Conservatives hold only one of the 59 Scottish seats in the British parliament; two leftist parties, Labour and the Scottish National Party, dominate Scottish politics. If the question of independence were settled, it seems like the Scots would be able to find lots of other things to agree on.

Would they agree on the right things? A generous welfare state and economic success aren’t incompatible for small nations — there are several examples of this just across the North Sea from Scotland. But since a stretch of tough economic times in the early 1990s, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland have combined their generosity with remarkable efficiency and economic savvy (Norway, with its vast oil riches, hasn’t had to make quite as many hard choices). They and other successful small states tend to balance their budgets, export more than they import, and invest heavily and smartly in infrastructure and R&D. As Skilling tells it, they have designed their economies to be globally competitive.

“Being a small country offers a lot of in-principle upside, brings with it significant risks, and is what you make it — but it’s only for serious countries,” Skilling replied when I emailed him about Scotland.

So is Scotland serious? Skilling thinks it is, but the leaders of the “Yes” movement don’t seem to be quite there yet. They assume that they can continue in a currency union with London when officials in London say that won’t work, for one thing. What’s more, Scotland today has giant government deficits, a fast-aging population, and not much in the way of exports apart from oil, The Economist argued this summer. That, and it has spent the past three centuries becoming ever more economically intertwined with the rest of Britain. Set loose alone on the rough seas of the global economy, it seems likely to founder at first.

After that, the question is whether the small-state effect would kick in. Would the Scots be able to get their act together and rally around things like fiscal discipline and smart tax policies and R&D investment? This is the land that spawned such great economic thinkers as Adam Smith, David Hume, and — what the heck — John Law. Surely the Scots could figure it out eventually. And once they did, it is entirely possible that an independent Scotland with a clear economic identity would be a more vibrant, cosmopolitan, thriving land than the sometimes-neglected northern appendage of a populous country that it is now.

The big question — which neither I nor anybody else outside Scotland can really answer — is whether it would be worth the pain it will probably take to get there.

Your Well-Being Declines When Others Are Unemployed, and Not Because of Empathy

A 1 percentage point increase in local unemployment depresses still-working people’s well-being to a degree that’s roughly equivalent to a 4% decline in household income, according to John F. Helliwell of the University of British Columbia and Haifang Huang of the University of Alberta, both in Canada. The apparent reason has nothing to do with workers’ feeling badly for the unemployed; instead, rising unemployment leads people to fear they’ll lose their own jobs, the researchers say.

How Being Filmed Changes Employee Behavior

Since Michael Brown’s shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, more than 154,000 people have signed a “We the People” petition to the White House to “require all state, county, and local police to wear a camera” to curb misconduct. The Ferguson police force was recently given about 50 cameras, following a national trend toward tech-enabled transparency.

The public may expect cameras to remove bias from interpretation of police behavior. If we can just see what happened, the thinking goes, we’ll know who was in the wrong.

But that’s not what the research shows. Video (particularly one-way footage) is not an all-seeing, neutral observer, as Florida International University law professor Howard Wasserman has repeatedly pointed out. The most significant impact of bodycams, taxicams, and the like is not reliving the past but, rather, changing behavior in the present. We act differently when we know we’re on camera.

That can certainly be a good thing, as researchers found in a field experiment with California’s Rialto Police Department. In that study, incidents occurring during shifts without cameras were twice as likely to result in the use of force. Indeed, when officers wore cameras, every physical contact was initiated by a member of the public, while 24% of physical contact was initiated by officers when they weren’t wearing the cameras.

You’ll see similar results — with an interesting twist — in a study by Washington University’s Lamar Pierce and his coauthors, who looked at employee behavior at almost 400 U.S. restaurants. Bodycams reduced restaurant employee theft by 22%, or about $24 per week. (The effect grew over time, with theft dropping $7 a week the first month and $48 a week by the third month.) But the cameras actually had a much larger impact on productivity and sales: On average, total check revenue increased by 7% ($2,975 per week), and total drink revenue by 10.5% ($927 per week). Tips went up, too, by 0.3%.

When increased monitoring made it harder for workers to steal money, the researchers observed, people redirected their efforts toward “increasing sales and customer service in order to regain some of that loss.” The positive responses to the cameras — performance improvements that benefitted employees as well as their employers — were more substantial than the negative behaviors they prevented.

So perhaps the real upside of surveillance is the potential to spot and reward good work, not to deter bad conduct. Other research suggests that, as well. A food-service study, for example, found that dining hall customers perceived greater employee effort and valued the service more when they could watch workers doing their jobs (through video-conferencing software on iPads). The effect was mutual: Employees felt more appreciated and, in turn, exerted greater effort when they had a clear view of customers. They completed orders much faster, and customers reported higher food quality. The reciprocal transparency created a positive feedback loop, generating value for both groups.

But transparency can also have an unintended negative consequence: Knowing that their managers and others will closely evaluate and penalize any questionable recorded behavior, workers are likely to do only what is expected of them, slavishly adhering to even the most picayune protocols. That’s what has happened in factory production work, where excessive transparency has thwarted both creativity and productivity. Assembly line workers hide fruitful time-saving and cross-training experiments to avoid having to explain them to anyone who might be watching. (See my recent HBR article about such tradeoffs.)

If too much transparency kills innovative behavior, how can police departments improve officers’ track record on profiling without sacrificing the kind of educated risk-taking and problem solving that’s often needed to save lives?

I would argue that the answer lies in focusing on developing good judgment and supporting justice, rather than on enforcing police protocol. Police in Ferguson and elsewhere can learn from companies that use cameras for coaching and development instead of evaluation and punishment. For example, a U.S. trucking company has installed a DriveCam in each of its tractor cabs — recording what’s happening both on the road and in the driver’s seat — to improve fleet safety. Coaches review the footage with the individual drivers, who are receptive to the feedback because they know the videos won’t be used against them. (The footage is only shown to managers in situations where drivers willfully break the law.) Even at UPS, which has sensors in its trucks to track workers’ every move and reduce delivery times, the master agreement with the Teamsters prohibits management from using the data to discharge employees.

More organizations — including police departments — should explore ways of making employee surveillance constructive rather than punitive. Part of the challenge here, of course, is that law enforcement and government agencies are required (for good reason) to be transparent to the public. A certain amount of transparency ensures accountability. But unless it’s mitigated with zones of privacy — areas where workers can receive developmental coaching, as the truck drivers do, without getting dinged for mistakes that generate learning — it may actually be counterproductive. If every choice, every little misstep, is recorded for all to see and to second-guess, people will quickly learn to play it safe in the worst sense. There aren’t many individuals who could work productively under the magnifying glass of an entire country of arbiters — the Hunger Games version of policing.

That said, in a country where smartphone penetration is now over 70%, and almost every smartphone has a video camera, another question is: how much police work is on video already?

Another Reason to Take More Breaks

Working long hours, while taking only short breaks or no breaks at all, can have negative consequences. Take medical workers. Researchers have found that staff members wash their hands less frequently at the end of their shifts than at the start. And they’re even more neglectful if they’ve been engaged in intense tasks. This is a big problem, especially in hospitals, where germs and bacteria can lead to infections, but it’s not unique to doctors and nurses. Workers of all stripes — meaning you and me — suffer from the same problem. When we’re tired and overworked, we tend to neglect secondary duties and responsibilities. But there is some good news: taking a long break from work can make us more diligent.

September 11, 2014

What New Team Leaders Should Do First

Getting people to work together isn’t easy, and unfortunately many leaders skip over the basics of team building in a rush to start achieving goals. But your actions in the first few weeks and months can have a major impact on whether your team ultimately delivers results. What steps should you take to set your team up for success? How do you form group norms, establish clear goals, and create an environment where everyone feels comfortable and motivated to contribute?

What the Experts Say

Whether you’re taking over an existing team or starting a new one, it’s critical to devote time and energy to establishing how you want your team to work, not just what you want them to achieve. The first few weeks are critical. “People form opinions pretty quickly, and these opinions tend to be sticky,” says Michael Watkins, the cofounder of Genesis Advisers and author of the updated The First 90 Days. “If you don’t take time upfront to figure out how to get the team working well, problems are always going to come up,” says Mary Shapiro, who teaches organizational behavior at Simmons College and is the author of the HBR Guide to Leading Teams. “You either pay upfront or you pay later.” Here’s how to start your team off on the right foot.

Get to know each other

“One of your first priorities should be to get to know your team members and to encourage them to get to better know one another,” says Shapiro. To that end, “resist the urge to immediately start talking about the work and the task outcome,” and focus instead on fostering camaraderie. In practice, this may mean holding a retreat or beginning meetings with team-building exercises. For virtual teams, it might mean starting calls by getting updates on how each person is doing or hosting virtual happy hours or coffee breaks. One particularly effective exercise is to have people share their best and worst team experiences, says Shapiro. Discussing those good and bad dynamics will help everyone get on the same page about what behavior they want to encourage — and avoid — going forward.

Show what you stand for

Use your initial interactions with team members as an opportunity to showcase your values. Explain what’s behind each of your decisions, what your priorities are, and how you will evaluate the team’s performance, individually and collectively. Walk them through what metrics you might use to gauge progress, so that they understand how they’ll be evaluated and what’s expected of them. “Team members will want to know how you define success,” says Shapiro. By communicating your vision and values, you will show your team that you’re committed to a healthy degree of transparency, says Watkins, and “create positive momentum around yourself in the new role.”

Explain how you want the team to work

You also need to explain in detail how you want the team to work. When you have newer team members coming on board, don’t assume that veteran team members will explain to the new recruits how meetings are supposed to be run or the best ways to ask for help; it’s your job as a leader to set expectations and explain processes. If you don’t make those norms clear for everyone, you risk creating an environment where people feel excluded, uncertain, or unwilling to contribute.

Set or clarify goals

One of your most important tasks as a team leader is to set ambitious but achievable goals with your team’s input. Make clear what the team is working toward and how you expect it to get there. By setting these goals early on, the group’s decision making will be clearer and more efficient, and you’ll lay the framework of holding team members accountable. Many managers inherit their teams, which often means they aren’t creating new goals, but clarifying existing ones. “It’s actually rare that someone gets to come in and redefine the goals for the group in a profound way,” says Watkins. In those instances, your challenge as a manager is to reorganize roles or rethink strategies to best achieve the goals at hand.

Keep your door open

If there’s one thing that new managers need to remember, it’s that over-communicating in the early days is preferable to the alternative. “It’s always better to start with more structure, more touch points, more check-ins at the beginning,” says Shapiro. How you do that — via big meetings, one-on-ones, email, or shared progress reports — will vary from team to team and manager to manager, but whatever the communication method, “do as much as you can,” says Shapiro. Watkins agrees: “I’ve never encountered a situation where a team member says, ‘Gosh, I wish the boss would stop communicating with me. I’m so sick of hearing from her.’ You just never hear that.”

Score an “early win”

Identifying and solving a business problem that has a quick and dramatic impact early on shows that you can listen and get things done, says Watkins. Perhaps there is a longstanding employee frustration or an outdated work process. Maybe there is a project that you can easily fund or prioritize. Taking swift action demonstrates that “you are connecting and learning.” But most importantly, achieving an “early win” builds team momentum. “It motivates people,” says Shapiro, “and can win you goodwill you might need later if the going gets tough.”

Principles to Remember

Do:

Be clear about what goes into your decision making and how you’ll evaluate the team’s progress

Encourage team members to connect — better communication early on will help avoid misunderstandings and poor results later

Look for roadblocks or grievances you can fix — it will earn you capital and inspire the team

Don’t:

Jump into trying to accomplish the work without building relationships with the team

Assume that new team members understand how you or others work — take the time to explain processes and expectations.

Be afraid to communicate often early on — you can always pull back when the team is working well

Case study #1: When in doubt, over-communicate

Czarina Walker, the founder and CEO of InfiniEDGE Software, had a crisis on her hands. She had recently taken over the leadership of a combined team of engineers and creative employees for a new project. With a deep well of experience leading technical teams, she assumed that the minimalist management approach that had worked for her for years would also work with this hybrid team. “I figured the non-techies had some understanding of our technical team’s processes, and knew how we worked by virtue of shared office osmosis,” Czarina says.

But the team dynamics floundered from the beginning. “My technical team didn’t have a problem getting in a room and talking about what was going well and what wasn’t,” says Czarina. But this standard tactic of identifying improvement areas with her engineers felt like a blame game to the new creative members. “They felt thrown into this process; it was like being invited to a firing squad.” Resentments festered, and soon she was having difficulty getting everyone to attend the weekly status meetings. “As a result, the project started off the exact way you hope it never does — with a lot of frustration and animosity,” she says.

Czarina recognized that her failure to establish communication norms was partly to blame. She hadn’t made the purpose of the status meetings clear, and hadn’t explained that her agenda was not aimed at criticizing, but at getting everyone on the same page. “So I had to do something I never had to do before: over-communicate,” Czarina says. She sat down with both groups to go over the purpose of the meetings, and how she expected them to be run, while addressing each groups’ concerns.

The extra work paid off. The project was completed on deadline, and the creative team members reported that they felt the process had been a valuable learning experience. “Even though I had to over-communicate,” Czarina says, “it was well worth it, because the next project is going to go so much smoother.”

Case study #2: Build connections outside the office

For the past decade, Nate Riggs, the founder of marketing firm NR Media Group, has run a virtual office, with employees scattered across the country. But this year, after realizing the company needed a brick-and-mortar base to grow its video production unit, Nate transitioned the firm to the new Columbus, Ohio, headquarters.

Because some employees still worked remotely and others reported to the office each day, Nate recognized that challenges and miscommunications could arise among the group, some of whom were new employees. So he held a team retreat in Columbus, a combination of strategy sessions, client meet-and-greets, and after-hours social events. “The team cohesiveness that was developed on that retreat has been amazing,” says Nate.

The team-building efforts had immediate benefits. “We left with a lot of momentum. Our first week back, we were meeting deliverables in about half the time that it took us before the retreat,” says Nate.

In order to maintain the energy, the team now gathers each week in a virtual Google Hangout with a set agenda. Nate also has regular one-on-one meetings with each team member to get status updates and reassess goals. “We try to keep high-frequency touches with the team, but not so much that it interferes with getting work done,” he says.

He has also encouraged the team to maintain the social connections they established at the retreat. To mimic the banter that might have happened around the office water cooler, employees have recently launched a group texting thread, regularly sharing jokes, interesting news, and funny stories with coworkers. “To me, that’s the indicator of a team culture, right?” says Nate. “We all have something that we can laugh at together.”

Track Customer Attitudes to Predict Their Behaviors

CRM is typically all about customer behavior: you track customers’ behavior in terms of where, when and in what context they interacted with your company. But the increasing ease with which you can track behavior and the ability to build and maintain extensive behavioral databases has encouraged many marketers to de-emphasize the collection and interpretation of “soft” attitudinal information: that is, data around customer satisfaction, attitudes towards brands, products, and sales persons, and purchase intentions.

The argument is that in-depth behavioral data already encapsulates underlying attitudes, and because decision makers are mainly concerned with customer behavior, there is not much need (any more) to worry about underlying attitudes. There’s a similar assumption underlying much of the discussion around how to measure the return on marketing investment, where it seems to be tacitly accepted that attitudinal insights are insufficient at senior decision-making levels, and behavioral insights represent today’s benchmarks.

But downplaying attitudinal data seems rather too convenient. After all, it’s hard work to capture attitudes. Purchases, customer inquiries, or mailing contacts are collected by firms continuously for all customers through CRM software systems, but attitudinal information rests in the hearts and minds of customers, who have to be explicitly prompted and polled for that information through customer surveys and textual analysis of customer reviews and online chatter. What’s more, some customers might not want to give that information, even if firms wanted to collect it.

Bottom line, you can maybe hope to get strong attitudinal information about a few customers, but it is unrealistic that you can get it about a lot of them — and you certainly can’t be polling everyone all that often just to get information from a possibly unrepresentative subset. Much easier, therefore, to pretend that attitudes are just not that important.

This is actually a cop-out. In fact, respectable analytic techniques exist that allow to you impute attitudes from a small group about which you have complete information (attitudes, behavior, demographics) to a larger group where the attitudinal information is missing, and then test whether the imputation of those attitudes produces better predictions of the larger group’s subsequent behavior (which you are tracking all the time).

Basically, what you do is analyze the relationships between attitudes, behavior, and demographics for customers in the small group so that you can express attitude as a derivative of the other observable factors: a male customer who is X years old and does Y will have Z attitude. You assign customers in the larger group with the attitudes that their behavior and demographics imply, using the relationships derived from the small group analysis. You then make predictions about their future behavior, which you can compare to the predictions you make on the basis of demographics and past behavior only.

We tested the approach with a company in the pharma industry. Our large dataset included the prescription history of more than six thousand physicians for a leading cardiovascular drug over 45 contiguous months. Physicians were surveyed on their attitudes toward the main drugs in the relevant therapeutic category, as well as their attitudes towards the firm’s salespeople. The survey asked the doctors, for example, to rate the product’s performance and to assess to what level they agreed or disagreed with statements made by the firm’s salespeople during sales calls in light of their experience with the drug. Our goal was to explore how the pharmaceutical firm’s customer lifetime value (CLV), customer retention, and sales were affected by the physicians’ experience of the drug coupled with their attitude regarding the salespeoples’ credibility and knowledge.

The results were startling. We found that for this company, a $1 million investment in collecting customer attitudes would deliver projected annual returns of more than 300% from providing more accurate behavioral predictions. It also revealed that attitude information for mid-tier customers (in terms of future profit potential) would produce the highest relative benefit. In other words, incorporating attitudes provides a forward-looking measure that helps to discriminate between the customers that will likely contribute to increasing profitability and those whose profitability will likely decline. In this case, it appeared that the firm was overspending on top-tier customers with regard to their CRM campaigns and that it could improve the ROI from CRM by rebalancing resources across top-tier and mid-tier customers.

Of course, there is no guarantee that the inclusion of customer attitude information in predictive CRM modeling will always yield returns. But our findings do make a very strong case that firms should explore avenues for tracking customer attitudes and to assess their predictive potential in order to adjust CRM strategies accordingly.

Rotary Strengthened Their Brand by Simplifying It

It’s no surprise that simplicity sells. Too many options can overload short-term memory, inhibiting the ability to process information, creating cognitive overload. In addition, excessive options can spark feelings of remorse after transactions as customers continue to wonder if they had made the right choice.

But creating “decision simplicity” presents only part of the brand simplicity picture. Sephora, Carrefour, and Amazon are examples of successful simple brands, despite providing a vast range of options to their customers.

Simplicity should be built into the very core of the brand, beginning with the product or service itself and extending through the interactions at each touch point and in all brand communications.

Achieving simplicity at this level is not easy, but the returns can be well worth the effort. The Siegel+Gale Global Brand Simplicity Index, an annual global study of 10,000 consumers (both customers and familiar nonusers) found that three out of four people are more likely to recommend a brand that provides simpler overall experiences and communications, and that people are even willing to pay more for a simpler brand’s product or service. In addition, brands that are perceived as being simple in their “products, services, interactions, and communications” outperformed indices on the stock market by as much as 100%.

So how can a brand achieve this form of simplicity? A look at the 2013 rebranding of the nonprofit Rotary can supply some clues.

Rotary is a highly complex organization, steeped in tradition, with 1.2 million members in 34,000 autonomously run clubs in 530 districts across the globe. Navigating its extensive and varied programming was difficult for members and the public alike, making it hard for the organization to stay relevant. Rotary also discovered, through an internal survey, that members had difficulty explaining the nonprofit’s role in the world.

Working with Siegel+Gale, they conducted two additional worldwide studies. The first one assessed a donor’s motivation to give money or time by comparing the nonprofit to 12 international peers and two local charities in each of four global regions to see how people perceived Rotary, as well as the respondent’s “brand preferences” among these organizations. This survey found that while some nonprofits were positioned clearly in people’s minds, Rotary wasn’t. The second study revealed that neither their members nor their staff could consistently answer the question, “What is Rotary?”

While the results were certainly disappointing, these surveys found two recurring and motivating themes: People join and stay with Rotary because of the connections they make with others and the positive feelings they get by giving back to their communities. Seeing the potential in these themes, Rotary adopted “community and connections” as their brand essence — the core benefit, promise, or purpose of a product, service, or organization.

Rotary organized all of their activities into three core areas at aligned with this brand essence: 1) “join leaders” for their club meetings; 2) “exchange ideas” for their work finding solutions to community problems; and, 3) “take action” for their work to create positive change in their local communities and in the world. As a result, Rotary was able to imply the benefits of getting involved with the organization, as well as explain how to do it, through one simple structure.

Finally, Rotary turned their attention to their website. Prior to the rebranding, this site was focused on internal operations, making it nearly incomprehensible to the general public. But with the new brand essence and architecture in place, they were able to simplify their messaging by using the three core areas as part of their navigation. They found they needed two websites: one for the public, helping them to understand Rotary’s role, and another for their members, where they could conduct their business. In addition, they updated their logo and imagery to underscore an experience centered on community and connections.

According to Rotary’s General Secretary, John Hewko, this simplification effort is showing positive results.

Based on Rotary’s experience, here are four key action steps to keep in mind for simplifying your brand:

Find your brand essence. Understanding what your brand stands for is not only essential for helping you focus your products and services, it is the key for helping you simplify your communications. A brand essence can be used as the screen for judging the appropriateness of everything from a group’s product and service offerings to their brand experience and communications. But be careful not to go too narrow with your essence. Focusing on one idea alone will be too limiting and handcuff your brand without providing the vibrancy needed for today’s world.

Hide your complexities. Many of the brands that rank high on the Siegel+Gale Brand Simplicity Index, such as Amazon and Google, have truly complex underpinnings, while providing a simple experience. Likewise, Rotary remains highly complex with its vast number of initiatives and programs. But the brand refresh simplified the experience into their three-item menu of “join leaders,” “exchange ideas,” and “take action,” making it easier for both members and non-members to get and stay involved.

Simplify your communications. Organizations that make their communications too complicated, have inconsistencies between their message and experience, or employ the use of fine print raise transparency questions and force consumers to work to align the promise with the reality. What consumers want is a clear presentation of the value a brand provides.

Realign your metrics. Measurements you once thought were helpful might not tell the entire story after your simplification process. When Rotary launched their new websites, they found that less time was spent on the site and there were fewer page views. But upon a further look, they learned that the change was because readers were now able to find their needed information more quickly — a key benefit of simplicity.

Taking these steps just might spark added recommendations and referrals, the ability to charge a premium, and greater brand value.

The Industries Plagued by the Most Uncertainty

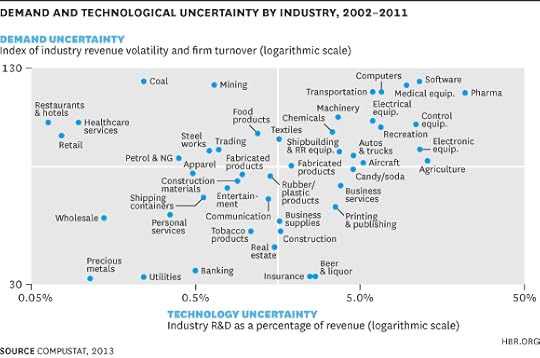

It’s a cliché to say that the world is more uncertain than ever before, but few realize just how much uncertainty has increased over the past 50 years. To illustrate this, consider that patent applications in the U.S. have increased by 6x (from 100k to 600k annually) and, worldwide, start-ups have increased from 10 million to almost 100 million per year. That means new technologies and new competitors are hitting the market at an unprecedented rate. Although uncertainty is accelerating, it isn’t affecting all industries the same way. That’s because there are two primary types of uncertainty — demand uncertainty (will customers buy your product?) and technological uncertainty (can we make a desirable solution?) — and how much uncertainty your industry faces depends on the interaction of the two.

Demand uncertainty arises from the unknowns associated with solving any problem, such as hidden customer preferences. The more unknowns there are about customer preferences, the greater the demand uncertainty. For example, when Rent the Runway founder Jenn Hyman came up with the idea to rent designer dresses over the internet, demand uncertainty was high because no one else was offering this type of service. In contrast, when Samsung and Sony were deciding whether to launch LED TVs, which offered better picture quality than plasma TVs at a slightly higher price, there was lower uncertainty about demand because customers were already buying TVs.

Technological uncertainty results from unknowns regarding the technologies that might emerge or be combined to create a new solution. For example, a wide variety of clean technologies (including wind, solar, and hydrogen) are vying to power vehicles and cities at the same time that a wide variety of medical technologies (chemical, biotechnological, genomic, and robotic) are being developed to treat diseases. As the overall rate of invention across industries increases, so does technological uncertainty.

Consider the 2×2 matrix below. The horizontal axis plots each industry based on technological uncertainty, measured as the average R&D expenditures as a percentage of sales in the industry over the past ten years. The vertical axis plots each industry’s demand uncertainty, measured as an equal weighting of industry revenue volatility, or change, over the past 10 years and percentage of firms in the industry that entered or exited during that same time period. Although these are imperfect measures, they identify the industries facing the highest, and lowest baseline levels of uncertainty.

The table below ranks industries into the top 10 and bottom 10.

Where does your industry sit?

If your industry is in the lower left quadrant, or in the bottom 10 in the above table, you face relatively low baseline uncertainty for both demand and technology. Examples of industries here include providers of personal services, such as hair styling and dry cleaning, who have used similar technologies to provide solutions for well-known demands. By contrast, if you’re in the lower-right quadrant, you can generally predict demand but the challenge you face is technological uncertainty. For example, insurance companies face technological uncertainty that comes from how big data and analytics investments will drive revenue; whereas demand is based on highly predictable demographics.

If you’re in the upper-left quadrant, you are with industries that face high demand uncertainty but low technological uncertainty. For example, restaurants and hotels often have difficulty predicting demand for their services, because many factors influence whether, when, and where people eat out or travel. However, the technologies used to offer food or lodging have not changed dramatically over the years. Finally, industries in the upper-right quadrant — such as software, pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment — face high uncertainty in both demand and technology. For example, who would have predicted that medical robots would perform surgeries? When Intuitive Surgical launched the Da Vinci System medical robot — which allows surgeons to operate using 3-D visualization and four robotic arms — the company faced significant technical as well as demand uncertainty.

If you’re in the upper right quadrant — or in the top 10 most uncertain industries as shown in the Table — you require greater innovation management skills than industries in the other quadrants or in the bottom 10. In fact, among the top 10 companies of the Forbes Most Innovative Companies list (since 2011 when we started the list), more than 80% of the most innovative companies compete in industries in the top right quadrant. In other words, if you are in a high uncertainty industry, you must excel at innovation…or die.

A new set of tools and perspectives — such as, for example, design thinking, lean start-up, agile development — are emerging in many disparate fields and revolutionizing the way managers in established companies successfully create, refine, and bring new ideas to market in conditions of high uncertainty. In our new book, The Innovator’s Method, we show how managers can adapt these tools, in an end-to-end process, for managing innovation.

For example, companies that excel at resolving demand uncertainty become experts at design thinking and validating concepts through rapid experimentation with customers. Successful software companies like Google, Intuit, and Salesforce.com churn out their “beta” or “labs” products that effectively test demand for new products. When Google software engineer Paul Bucheit had ideas for Gmail and AdSense (the system that placed advertisements based on keywords in your Gmail messages, search, or website) he found he was often fighting against the opinions of leaders. But fortunately, experiments with customers trump opinions at Google. Following the advice of then CEO Eric Schmidt to “get 100 happy users inside Google,” Bucheit prototyped solutions that eventually proved demand and won the day. Today, AdSense generates $10 billion in annual revenue for Google.

Companies that excel at resolving technological uncertainty often develop a broader technology palette. For example, to help start-up teams generate a broad list of solutions, Intuit identified and hired experts in technologies related to mobile devices, social media, user interaction, collaboration, data, and the like. These experts are valuable for broadening solution searches, and they help teams identify what is technologically feasible. At biotech Regeneron, the company pioneered a new experimentation platform — “humanized” mice that allowed them to test drug effects more rapidly and reliably — that dramatically increased their ability to test various technology solutions to problems.

The bottom line is that success requires an understanding of how much uncertainty you face and the ability to manage those uncertainties in new ways.

How much uncertainty does your industry face? Ask yourself the following questions:

Have new technologies or startups started to threaten my company or my industry?

Over the past five years have new competitors entered the market and captured 10% share by targeting our customers with a different value proposition than what we offer?

Over the past five years have we begun to see customer preferences change, resulting in a different mix of products and services being demanded?

Have you recently started offering (or are planning to offer) a product or service that has never been offered before?

If you answered “yes” to the first two questions, you’re likely sitting in a business with high technological uncertainty; if “yes” to the last two questions, you’re probably dealing with high demand uncertainty.

American Wealth Gap Widens Despite Economic Recovery

The surge in the U.S. stock market over the past few years has disproportionately benefited wealthier Americans, according to the Federal Reserve and the Wall Street Journal. While nearly all families in the top 10% owned shares, the proportion of families holding stock declined from 15.1% in 2010 to 13.8% in 2013, says the Fed, with the decrease in stock ownership being most pronounced in the bottom half of the income distribution. Between 1989 and 2013, the proportion of all U.S. family wealth owned by the top 3% rose from 44.8% to 54.4%, while the proportion owned by the bottom 90% fell from 33.2% to 24.7%.

A Speech Is Not an Essay

Reading an essay to an audience can bore them to tears. I recently attended a conference where a brilliant man was speaking on a topic about which he was one of the world’s experts. Unfortunately, what he delivered was not a speech but an essay. This renowned academic had mastered the written form but mistakenly presumed that the same style could be used at a podium in the context of an hour-long public address. He treated the audience to exceptional content that was almost impossible to follow — monotone, flat, read from a script, and delivered from behind a tall podium.

He would have done well to heed the words of communication professor Bob Frank: “A speech is not an essay on its hind legs.” There is a huge difference between crafting a speech and writing an essay. And for those new to public speaking, the tendency to mimic the forms of writing we already know can be crippling.

Speeches require you to simplify. The average adult reads 300 words per minute, but people can only follow speech closely at around 150-160 words per minute. Similarly, studies have shown auditory memory is typically inferior to visual memory, and while most of us can read for hours, our ability to focus on a speech is more constrained. It’s important, then, to write brief and clear speeches. Ten minutes of speaking is only about 1,300 words (you can use this calculator), and while written texts — which can be reviewed, reread, and reexamined — can be subtle and nuanced, spoken word must be followed in the moment and must be appropriately short, sweet, and to the point.

As you focus on brevity and clarity in a speech, it’s also important to signpost and review. In a written essay, readers can revisit confusing passages or missed points. Once you lose someone in a speech, she may be lost for good. In your introduction, state your thesis and then lay out the structure of your speech ahead of time (e.g., “we’ll see this in three ways: x, y, and z”). Then, as you work through your speech, open each new point with a signpost to let your listeners know where you are with words such as, “to begin,” “secondly,” and “finally,” and close each point with a similar, review-oriented signpost (e.g., “so we see, the first element of success is x”). This lack of subtlety can be repetitive and inelegant in a written document, but it is essential to the spoken word.

Similarly, the subtleties of complex argumentation and statistical analysis can be compelling in an essay, but in a speech it’s important to drop the statistics and tell a story. Neuroscience has shown that the human brain was wired for narrative. And while I always appreciate arguments that are fact-based and grounded in sound logic, it’s easier for me to engage with a speaker when she keeps the statistics to a minimum and opts for longer and more vivid stories. Lead or end an argument with statistics. But never fall into reciting strings of numbers or citations. Your audience will better follow, remember, and internalize stories.

To bring these stories to life, remember that when delivering a speech you are your punctuation. When you’re speaking, your audience doesn’t have the benefit of visual signifiers of emphasis, change in pace, or transition — commas, semicolons, dashes, and exclamation points. They can’t see question marks or paragraph breaks. Instead, your voice, your hand gestures, your pace, and even where and how you’re standing on stage give the speech texture and range. Vary your excitement, tone, and volume for emphasis. Use hand gestures consciously and in accordance with the points you’re trying to make. Walk between main points while delivering the speech — literally transitioning your physical position in the room to signify a new part of the argument. Standing motionless while speaking in a monotone voice doesn’t simply drain your audience’s energy, it deprives them of understanding — like writing a text in one run-on sentence with no punctuation or breaks. Resist the urge to read your speech directly from the page. Become the punctuation your audience craves.

Speeches and essays are of the same genus, but not the same species. Each necessitates its own craft and structure. If you’re a great writer, don’t assume it will translate immediately to the spoken word. A speech is not an essay on its hind legs, and great speech writers and public speakers adapt accordingly.

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers