Marina Gorbis's Blog, page 1373

September 2, 2014

How to Manage Scheduling Software Fairly

Starbucks workers recently scored a point against the machine. After a lengthy New York Times story, the company decided to adjust some of their controversial scheduling practices, eliminating “clopening” — when workers are required to close at night and re-open in the morning — and requiring at least a week’s notice of upcoming schedules.

In this case, “the machine” refers to a real machine: the highly sophisticated automated software Starbucks uses to schedule its 130,000 baristas, sometimes giving them less than a few day’s notice about their schedules in order to “optimize” its workforce.

Starbucks is just one of many companies using this type of technology, and it’s not hard to understand why. Until recently, determining who works when involved store managers manually slotting each employee into shifts on paper. Automation not only frees store managers to focus on customers, but can take into account much more data than a person can remember —historical customer patterns, weather, experience at neighborhood stores — so workers spend less time either with nothing to do or being completely overwhelmed with long lines and unhappy customers.

As the argument goes, that’s good for workers, who don’t want to be bored or overwhelmed, and it’s good for retailers, whose biggest cost and revenue driver is typically labor.

Our collective research has also shown that retailers really do struggle with scheduling. In a study of 41 stores of a women’s apparel retailer, for example, Saravanan Kesavan and his co-authors found that all of the stores were understaffed significantly during the peak periods of the day, while they were significantly overstaffed during the rest of the hours. The authors estimated that the retailer was losing about 9% of sales and 7% of profits due to this mismatch.

So why not implement just-in-time, software-driven staffing across the board? The problem — and one that Starbucks was forced to face first-hand— is that while scheduling software may seem “like magic,” as one of the major software vendors in the Times article put it, it’s actually not. Starbucks’ experience is common among a number of retailers who have taken their passion for engineering and optimizing schedules too far. As soon as a computer is scheduling your people at 15-minute increments to match the peaks and valleys of customer demand, employees’ desire to live a normal, predictable life becomes a barrier to profitability.

Three additional realities get in the way:

Perfect forecasts don’t exist. To produce an optimal labor schedule, the scheduling software must forecast customer patterns accurately—if you want to schedule labor at 15-minute increments, you must also understand demand at 15-minute increments. The dirty little secret is that even the most advanced scheduling software, incorporating every bell and whistle, tends to be wrong at least as often as it is right when the time intervals are short.

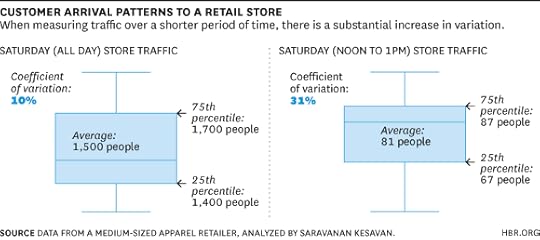

For example, the charts below show the variation in customer arrival pattern for a retail store on Saturdays, and then a breakdown of the same store between noon and 1 p.m. on Saturdays. The coefficient of variation, a measure of how variable the traffic is, increases from 10% to 31% as we go from daily to hourly data. This implies that it would be lot harder to predict hourly traffic compared to daily traffic, and it’s guaranteed to be lot more erroneous when predictions are generated at the 15-minute interval.

Because of this, good scheduling software tends to serve the “normal” customers well (those buying cappuccinos on the way to work every morning), but it may be at least as important to serve the abnormal ones (like a person who buys 20 lattes for a single meeting).

Tracking everything is unreliable. The response to unpredictable customer behavior has been, “well, let’s just track everything more carefully.” But tracking doesn’t always yield better predictions. For one, there’s inherent variability, as shown in the arrival pattern of customers to 35 stores of a retail chain over a period of a day. The differences between the top and bottom lines – in other words, the differences between two stores – don’t offer much in the way of insights.

Increased tracking can also create distortions in the data and unforeseen employee reactions, as Ethan Bernstein has found in his research. At a factory in Southern China, for example, executives thought that watching workers would help managers increase productivity and lower costs. It turns out that the opposite was true: Employees were more likely to be innovative when they weren’t being monitored, and production slowed when all eyes were on them.

A lot of flexibility isn’t necessarily a good thing. Saravanan Kesavan, Brad Staats, and their co-author have shown that temporary and part-time workers can help improve sales and profitability up to a point. For example, store profits were found to increase when the number of part-time and temporary workers was increased from zero to 4-5 for every 10 full-time workers. But beyond that point, any further increase in the number of those workers decreased store profits as the intangible costs of lower motivation and greater coordination dominated the benefits of scheduling workers to meet unpredictable demand.

So what should retailers do? To start, they can learn a lot from the considerable variation in how these systems have been implemented across companies. We see them as falling somewhere in the spectrum of purely creating value for management and purely creating value for workers.

The systems designed solely to create value for management fail to take into account so many unpredictable (and human) variables that they often result in public failures. In 2011, over 4,000 workers from Macy’s threatened to go on strike, in part because employees felt that the management was pushing for an online scheduling system that would make their schedules unpredictable. Walmart has often been accused by working mothers that the unpredictable schedules and low wages hurt their lives. The story of Jannette Navarro, the Starbucks worker profiled in the Times, absolutely rings true.

At the same time, strictly human-centric approaches can be problematic: If store relies on a remote scheduler, that’s a person who isn’t spending time with customers or employees. Like the scheduler Ms. Navarro had to beg in order to get 40 hours, he or she may also exert unfair power over workers.

Some systems, however, are implemented to create value for workers while simultaneously taking advantage of software’s benefits. If a store has a scheduling system that is accessible to, and modifiable by a team of corporate managers, store managers, and workers, it can balance human needs, customer needs, and company needs in a fair, transparent, and more informed way. These implementations can make ordinary workers, even part-time workers, better at managing themselves.

In other words, the best kinds of scheduling systems involve both managers and software, not for the purpose of more tightly controlling workers, but to inform them on how optimal schedules stack up against predicted forecasts. For example, what if store-level employees could edit the schedules produced by the machine, but were held accountable for the ultimate effectiveness of them?

This is the exact approach taken by Belk, the largest family owned and operated department store in the United States. Before their tool was implemented, scheduling was performed by store managers and schedulers who balanced profits and worker needs to create a “fair” schedule that worked for everyone — incorporating preferences and an equal amount of weekend work. These types of nuances, with lots of variation, were too complicated for any workforce software to take into account.

So when Belk implemented their new tool, employees saw its failure to create fair schedules as “bugs” in the software.

But unlike other retailers who take an iron hand to push compliance with a new system, this retailer let the team at the store “edit” the system to “fix” the “bugs” — essentially, they allowed workers and their supervisors to ensure they had the days or hours off they needed, more than a week in advance, by overriding the system.

At the same time, a central workforce team at corporate was tasked with analyzing a sampling of edits to understand their reasons and benefits. Some edits were, of course productive; others involved resistance to change or misunderstandings and miscommunications. Belk then worked with its store managers through weekly meetings to encourage compliance in areas where the scheduling system made sense, and at the same time provided feedback to the scheduling company to update its software where the schedules did not make sense.

Belk now revises about 50% of its scheduling based on this new approach, a healthy balance between the efficiency you get from a machine and the intelligence you get from human intervention. And the company reported a 2% increase in gross profits several months after implementing the override system.

Ultimately, the success of scheduling systems depends on whether they serve as tools for or against the workers. In many ways, data-driven scheduling software is attractive to retailers because it gives them unprecedented transparency. But the ultimate success of these systems depends on this same transparency being available to employees as well. When management takes enabling its workers seriously — when these tools become an experiment in worker learning rather than top-down compliance — results can far exceed even the most magical predictions that scheduling software initially promised.

A Predictive Analytics Primer

No one has the ability to capture and analyze data from the future. However, there is a way to predict the future using data from the past. It’s called predictive analytics, and organizations do it every day.

Has your company, for example, developed a customer lifetime value (CLTV) measure? That’s using predictive analytics to determine how much a customer will buy from the company over time. Do you have a “next best offer” or product recommendation capability? That’s an analytical prediction of the product or service that your customer is most likely to buy next. Have you made a forecast of next quarter’s sales? Used digital marketing models to determine what ad to place on what publisher’s site? All of these are forms of predictive analytics.

Predictive analytics are gaining in popularity, but what do you—a manager, not an analyst—really need to know in order to interpret results and make better decisions? How do your data scientists do what they do? By understanding a few basics, you will feel more comfortable working with and communicating with others in your organization about the results and recommendations from predictive analytics. The quantitative analysis isn’t magic—but it is normally done with a lot of past data, a little statistical wizardry, and some important assumptions. Let’s talk about each of these.

The Data: Lack of good data is the most common barrier to organizations seeking to employ predictive analytics. To make predictions about what customers will buy in the future, for example, you need to have good data on who they are buying (which may require a loyalty program, or at least a lot of analysis of their credit cards), what they have bought in the past, the attributes of those products (attribute-based predictions are often more accurate than the “people who buy this also buy this” type of model), and perhaps some demographic attributes of the customer (age, gender, residential location, socioeconomic status, etc.). If you have multiple channels or customer touchpoints, you need to make sure that they capture data on customer purchases in the same way your previous channels did.

All in all, it’s a fairly tough job to create a single customer data warehouse with unique customer IDs on everyone, and all past purchases customers have made through all channels. If you’ve already done that, you’ve got an incredible asset for predictive customer analytics.

The Statistics: Regression analysis in its various forms is the primary tool that organizations use for predictive analytics. It works like this in general: An analyst hypothesizes that a set of independent variables (say, gender, income, visits to a website) are statistically correlated with the purchase of a product for a sample of customers. The analyst performs a regression analysis to see just how correlated each variable is; this usually requires some iteration to find the right combination of variables and the best model. Let’s say that the analyst succeeds and finds that each variable in the model is important in explaining the product purchase, and together the variables explain a lot of variation in the product’s sales. Using that regression equation, the analyst can then use the regression coefficients—the degree to which each variable affects the purchase behavior—to create a score predicting the likelihood of the purchase.

Voila! You have created a predictive model for other customers who weren’t in the sample. All you have to do is compute their score, and offer the product to them if their score exceeds a certain level. It’s quite likely that the high scoring customers will want to buy the product—assuming the analyst did the statistical work well and that the data were of good quality.

The Assumptions: That brings us to the other key factor in any predictive model—the assumptions that underlie it. Every model has them, and it’s important to know what they are and monitor whether they are still true. The big assumption in predictive analytics is that the future will continue to be like the past. As Charles Duhigg describes in his book The Power of Habit, people establish strong patterns of behavior that they usually keep up over time. Sometimes, however, they change those behaviors, and the models that were used to predict them may no longer be valid.

What makes assumptions invalid? The most common reason is time. If your model was created several years ago, it may no longer accurately predict current behavior. The greater the elapsed time, the more likely customer behavior has changed. Some Netflix predictive models, for example, that were created on early Internet users had to be retired because later Internet users were substantially different. The pioneers were more technically-focused and relatively young; later users were essentially everyone.

Another reason a predictive model’s assumptions may no longer be valid is if the analyst didn’t include a key variable in the model, and that variable has changed substantially over time. The great—and scary—example here is the financial crisis of 2008-9, caused largely by invalid models predicting how likely mortgage customers were to repay their loans. The models didn’t include the possibility that housing prices might stop rising, and even that they might fall. When they did start falling, it turned out that the models became poor predictors of mortgage repayment. In essence, the fact that housing prices would always rise was a hidden assumption in the models.

Since faulty or obsolete assumptions can clearly bring down whole banks and even (nearly!) whole economies, it’s pretty important that they be carefully examined. Managers should always ask analysts what the key assumptions are, and what would have to happen for them to no longer be valid. And both managers and analysts should continually monitor the world to see if key factors involved in assumptions might have changed over time.

With these fundamentals in mind, here are a few good questions to ask your analysts:

Can you tell me something about the source of data you used in your analysis?

Are you sure the sample data are representative of the population?

Are there any outliers in your data distribution? How did they affect the results?

What assumptions are behind your analysis?

Are there any conditions that would make your assumptions invalid?

Even with those cautions, it’s still pretty amazing that we can use analytics to predict the future. All we have to do is gather the right data, do the right type of statistical model, and be careful of our assumptions. Analytical predictions may be harder to generate than those by the late-night television soothsayer Carnac the Magnificent, but they are usually considerably more accurate.

Predictive Analytics in Practice

An HBR Insight Center

Nate Silver on Finding a Mentor, Teaching Yourself Statistics, and Not Settling in Your Career

Beware Big Data’s Easy Answers

Who’s Afraid of Data-Driven Management?

When to Act on a Correlation, and When Not To

It’s Never Been More Lucrative to Be a Math-Loving People Person

Parents who spend a good chunk of the week shuttling kids to and from soccer practice or drama club might be comforted by new research that suggests this effort is not in vain – as long as their kids are good at math, too.

A recent paper from UCSB found that the return on being good at math has gone up over the last few decades, as has the return on having high social skills (some combination of leadership, communication, and other interpersonal skills). But, the paper argues, the return on the two skills together has risen even faster.

What does all that have to do with soccer practice? The research compared two groups of white, male U.S. high school seniors – the class of 1972 and the class of 1992 – to see how earnings associated with social and math skills have changed over time. Using two National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) surveys, it looked at senior year math scores on standardized tests, questions about extracurricular participation and leadership roles, and individual earnings seven years after graduating high school. And it corroborated the findings with Census and CPS data.

The analysis found that while math scores, sports, leadership roles, and college education were all associated with higher earnings over the 1979-1999 period, the trend over time in the earnings premium was strongest among those who were both good at math and engaged in high school sports or leadership activities. In other words, it pays to be a sociable math whiz, more so today than thirty years ago.

Some may be skeptical that high school sports participation or club leadership (the study also includes publications and performing arts groups) are accurate indicators of “social skills” – perhaps rightfully so. But these extracurriculars, which typically involve teamwork, communication, and general interaction with others, have long been associated with the development of social skills. (Whether these activities foster these skills or attract already social kids is another question.) And the paper looked at how they tend to affect future careers:

The sports/leadership group is likely to be employed in an occupation requiring higher levels of responsibility for direction, control and planning, even after controlling for high school math scores, psychological measures, and college completion. This is compelling evidence that participation in high school sports or leadership activities – a behavioral indicator of social skills – can be linked to … complex interpersonal skills.

The other justification for using sports and clubs as a proxy for social skills was methodological. In order to measure how the price of social skills has changed over time, comparable metrics were needed. They may not be perfect, but these categories stayed available and consistent over time.

The analysis was restricted to white men for the same reason – their test scores and activity levels remained the same, while a lot of things were changing for other groups. According to the paper, “Math scores were stable across cohorts among white men, but not among black students – and women’s participation in high school roles and activities changed dramatically during these years.”

But the author argues that the findings are still likely generalizable – and help to explain the changing demand in the labor market for different skills.

According to the data, while people focused on the surge in demand for math skills in the ‘80s and ‘90s, there was a concurrent (and underappreciated) increase in demand for both math and social skills. Employment in high-skill occupations increased between 1977 and 2002, but the paper found that, among the groups studied, all of that growth was in jobs that required both analytic and social skills. Employment in jobs requiring just one or the other didn’t increase over time. And this growing importance for “multiskilled” individuals in the labor force can be seen in the higher earnings for those who played sports or led in high school.

Why the increasingly valuable relationship between the two skills? Cathy Weinberger, the author, says answering that requires further research. But others have studied how technological innovations affect workforce skill requirements. Weinberger mentioned one study that found that adopting new technologies not only resulted in technical training for workers, but also in training to develop their complex communication skills and teamwork. So this rise in demand for social skills, happening alongside the rise in demand for math skills, could be the result of technological progress.

The data suggests that today’s economy rewards the balance of quantitative and social skills more than ever. That has ramifications for how we educate children – calling into question schools’ heightened focus on standardized testing, as opposed to a broader view of skills development – as well as for our own careers. In an era even more defined by rapid technological innovation, we’re increasingly expected to bring technical savvy and interpersonal know-how to the table. Quantitative reasoning is understandably in high demand, but so too are the skills learned on the sports field.

Beware Consumers’ Assumptions About Your Green Products

In an experiment, people expressed greater intentions to purchase a dish soap when they were told its environmental benefits were an “unintended side effect” of the product-development process, as opposed to a planned feature (5.65 versus 4.77 on a 9-point scale, on average), says a team led by George E. Newman of Yale. Results for other products were similar. The apparent reason: Consumers tend to assume that product enhancements in one dimension — such as environmental impact — come at the expense of performance on other dimensions.

What to Do on Your First Day Back from Vacation

You come back from vacation and start your game of catch-up. This is an especially challenging game if you’re a senior leader. You have hundreds, maybe thousands of emails, a backlog of voicemails, and a to-do list that doubled or tripled in length while you were away. You need to respond to the pent-up needs of clients, managers, colleagues, employees, and vendors. You need to fight fires. You need to regain control.

So you do your best to work through the pileup, handling the most urgent items first, and within a few days, you’re caught up and ready to move forward. You’re back in control. You’ve won.

Or have you?

If that’s your process, you’ve missed a huge leadership opportunity.

What’s the most important role of a leader? Focus.

As a senior leader, the most valuable thing you can do is to align people behind your business’s most important priorities. If you do that well, the organization will function at peak productivity and have the greatest possible impact. But that’s not easy to do. It’s hard enough for any one of us to be focused and aligned with our most important objectives. To get an entire organization aligned is crazy hard.

Once in a while, though, you get the perfect opportunity. A time when it’s a little easier, when people are more open, when you can be more clear, when your message will be particularly effective.

Coming back from vacation is one of those opportunities. You’ve gotten some space from the day to day. People haven’t heard from you in a while. Maybe they’ve been on vacation too. They’re waiting. They’re more influenceable than usual.

Don’t squander this opportunity by trying to efficiently wrangle your own inbox and to-do list. Before responding to a single email, consider a few questions:

What’s your top imperative for the organization right now? What will make the most difference to the company’s results? What behaviors do you need to encourage if you are going to meet your objectives? And, perhaps most importantly, what’s less important?

The goal in answering these questions is to choose three to five major things that will make the biggest difference to the organization. Once you’ve identified those things, you should be spending 95% of your energy moving them forward.

How should you do it?

Be very clear about your three to five things. Write them down and choose your words carefully. Read them aloud. Do you feel articulate? Succinct? Clear? Useful? Will they be a helpful guide for people when they’re making decisions and taking actions?

Use them as the lens through which you look at – and filter – every decision, conversation, request, to do, and email you work through. When others make a request, or ask you to make a decision, say them out loud, as in “Given that we’re trying to accomplish X, then it would make sense to do Y.”

Will that email you’re about to respond to reinforce your three to five priorities? Will it create momentum in the right direction? If so, respond in a way that tightens the alignment and clarifies the focus by tying your response as closely as you can to one or more of the three to five things, as you have written them.

If you look at an email and can’t find a clear way to connect it to the organization’s top three to five priorities, then move on to the next email. Don’t be afraid to de-prioritize issues that don’t relate to your top three to five things. This is all about focus, and in order to focus on some things, you need to ignore others.

You’ve got this wonderful opportunity, a rare moment in time when your primary role and hardest task – to focus the organization – becomes a little easier. Don’t lose it.

Coming back from vacation isn’t simply about catching up. It’s about getting ahead.

September 1, 2014

How Beacons Are Changing the Shopping Experience

Beacons are taking the world of mobile by storm. They are low-powered radio transmitters that can send signals to smartphones that enter their immediate vicinity, via Bluetooth Low Energy technology. In the months and years to come, we’ll see beaconing applied in all kinds of valuable ways.

For marketers in particular, beacons are important because they allow more precise targeting of customers in a locale. A customer approaching a jewelry counter in a department store, for example, can receive a message from a battery-powered beacon installed there, offering information or a promotion that relates specifically to merchandise displayed there. In a different department of the same store, another beacon transmits a different message. Before beacons, marketers could use geofencing technology, so that a message, advertisement, or coupon could be sent to consumers when they were within a certain range of a geofenced area, such as within a one-block radius of a store. However, that technology typically relies on GPS tracking, which only works well outside the store. With beaconing, marketers can lead and direct customers to specific areas and products within a store or mall.

As a point of technical accuracy, the beacon itself does not really contain messaging; rather it sends a unique code that can be read only by certain mobile apps. Thus, the carrier of the smartphone has to have installed an app – and if he or she has not done so, no message will arrive. The choice to opt-out exists at any time. But the key to beaconing’s effectiveness is that the app does not actually have to be running to be awakened by the beacon signal.

Think about it, and you realize that beaconing has been the missing piece in the whole mobile-shopping puzzle. The technology is essentially invisible and can work without the mobile consumer’s having to do anything – usually a major hurdle for any mobile shopping technology. The shopper only has to agree in advance to receive such messages as they shop.

So imagine walking by or into a store and receiving a text message triggered by a beacon at the store entrance. It alerts you that mobile shoppers are eligible for certain deals, which you can receive if you want. Assuming you accept, you begin receiving highly relevant messaging in the form of well-crafted, full-screen images based on what department or aisle you are strolling through at the moment. Here’s an example:

Implementing beaconing is less about installing the actual beacons and much more about rethinking the overall shopping experience they can help shape. Since the best way to imagine the possibilities is through actual, small-scale deployments, this has been how many retailers have spent the past several months, quietly experimenting and learning. Now, many are ready to scale up their initiatives, and beacons are bursting onto the scene in a big way. For various purposes, they are being used by retailers such as Timberland, Kenneth Cole, and Alex and Ani, hoteliers such as Marriott, and a variety of sports stadiums. Here are some details from a handful of companies – each by the way running on a different beacon platform:

Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). The owner of Lord & Taylor, Hudson’s Bay, and Saks recently became the first major retailer to launch a North American beacon deployment, in its U.S. and Canadian stores. A shopper with the SnipSnap coupon app on an iPhone can receive messages and offers from seven separate in-store, beacon-triggered advertising campaigns. Like some others, the retailer is not relying on its own app for the beacon recognition, but rather is using outside, third-party apps that more people are likely to already have on their phones. (This also allows Lord & Taylor to use the beacon program for new customer acquisition.) The Hudson’s Bay beacon program runs on the advertising platform of Boston-based Swirl.

Hillshire Brands. In what appears to be the first U.S.-wide beacon deployment by a brand, the maker of Ball Park Franks, Jimmy Dean sausage, Sara Lee, and the Hillshire Farm portfolio of products, beaconed grocery shoppers to launch its new American Craft sausage links in the top 10 markets for grocers nationally. Based on an analysis by Hillshire’s agency BPN (part of the IPG Mediabrands global network), there were 6,000 in-store engagements in the first 48 hours of the two-month trial, and purchase intent increased 20 times. Shoppers needed an app such as Epicurious, Zip List, Key Ring, or CheckPoints; this beacon platform is run by InMarket.

Universal Display. This global mannequin company based in London and New York is putting beacons inside mannequins in store windows. Why? To allow passersby to instantly see the details of the outfit the mannequin is wearing – and purchase any of its components right from their phones. The beaconed-mannequins are in the U.K. in the House of Fraser, Hawes & Curtis, Bentalls, and Jaeger, and will soon come to stores in the U.S. Here, the beacon app used is Iconeme, which is also the platform.

Simon Malls. The giant of retail real estate is putting location-based technology into more than 200 of its shopping malls, targeting the complexes’ common areas. For beacon recognition, the mall owner is using its own Simon Malls app, which already contains mall information ranging from maps to dining options. That beacon platform is run by Mobiquity.

Regent Street. London’s mile-long, high-end shopping street has some 140 store entrances, and now has beacons at the entrances of many of them. The beacon app used is the Regent Street app, slated to be promoted on the sides of double-decker buses that run along Regent Street. The app allows shoppers to pre-select the categories that interest them and the ones that don’t, making the messages they receive more relevant to them. That platform is run by Autograph.

That’s a lot of activity to report, but the truth is that it only constitutes a vanguard. Most shoppers have yet to be beaconed; many will encounter the technology before the end of this year. How long will it be until it’s hard to find someone who is not familiar with beaconing? How long till it’s hard to remember a time when the marketing messages you encountered had nothing to do with where you were? I would guess, not long at all.

Give Your Organization a Work-Life Vision

More and more companies are acknowledging the importance of work-life balance, at least as far as official policy goes. The Families and Work Institute’s 2014 National Study of Employers finds that, compared to six years ago when it conducted the same survey, several numbers have moved in the right direction:

Employers have continued to increase their provision of options that allow at least some employees to better manage the times and places in which they work. These include occasional flex place (from 50% to 67%); control over breaks (from 84% to 92%); control over overtime hours (from 27% to 45%) and time off during the workday when important needs arise (from 73% to 82%).

So why doesn’t it feel like we’ve made that much progress? Because, unfortunately, policies aren’t worth much in the absence of supporting culture. Research shows that an organization’s work-life culture – all the unwritten yet well understood norms and expectations about how people are supposed to work, and what it means to be a good employee – has enormous power over behavior. Culture is what really defines how much latitude people have in terms of managing their work and non-work demands, whether or not there’s a flextime policy on the books.

For a striking example, think back a year to the sad story of Moritz Erhardt. He was the 21-year-old investment banking intern who died in London, August 15, 2013, after having worked 72 hours straight at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. (To be clear, the coroner testified that Erhardt suffered an epileptic seizure, and while exhaustion from the 72-hour work marathon might have triggered it, she could not conclude whether this was so.) When the news broke, a director at the bank commented: “We are used to working with people who are ambitious and want to over-perform.” Fellow employees were more candid about the expectations they faced at work, where it was not uncommon to stay till 3 or 4 am. “If you go home at 11 pm, it is said you are ‘giving up’,” said one. “You have no hope of a job offer.”

Investment banking industry: this is your culture speaking. There is no question that Bank of America Merrill Lynch had work-life policies in place. There is also no question that having those policies didn’t change the reality of the organization

How, then, can business leaders start cultivating a healthier work-life culture? The levers at hand are communications and, more important, personal modeling – both by executives at the top and in the management ranks. For instance, SurveyMonkey CEO Dave Goldberg, husband of Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, believes that creating a company culture that encourages people to lead full lives is key to his edge in hiring key leaders and retaining top talent. He proves this point by leaving his office every day at 5:30 p.m. Sabrina Parsons, CEO of Palo Alto Software, makes sure employees know they can bring their children to work any time they need to. The director of a French electric utility I’ve worked with uses the top 40 managers in his organization as a key work-life pilot group, making sure that they use the work-life policies the company makes available and meet regularly to discuss how they can better support work-life integration.

But as easy and inspiring as it is to cite such examples, it’s surprisingly hard to shift the culture of an existing organization. It takes a high level of consistency in communications, rewards, and executive behaviors over time. To drive all of these in the same, positive direction, I’d suggest you need a work-life vision.

Having a work-life vision means being able to offer an overarching point of view that is compelling to people and provides guidance to their daily behaviors, decisions, and practices. Here’s a work-life vision that might serve you well: The best managers in our organization are the ones who best manage the energy of their teams. Energy is something we can all recognize as a precious resource, which is only valuable in use, yet must not be over-exploited and should not be wasted. In an organization, energy is the essential “human resource” to be channeled – every bit as important as financial resources to success, and often more so.

Share this work-life vision and it gives managers a consistent way to think about situations that require work-life judgment: what they must balance is not the conflicting desires for output (on the employer’s part) and time away from work (on the employee’s part). It’s the two sides of a coin both parties want: good work accomplished today, by burning energy, and good work accomplished tomorrow, by conserving and replenishing energy.

There is already a rich literature having to do with human energy management (including this classic HBR article) – my point here is not to reinvent that wheel. My argument is that reframing work-life balance in terms of energy management can provide the vision that allows you to change culture. It casts the work of leaders in a new way. They are the champions and defenders of workforce energy, responsible for ensuring that employees have the physical, cognitive, and emotional resources to draw on, as well as the sense of purpose, to do the organization’s important work.

I like the energy vision especially because it empowers organizations to deal with what I call the third rail of work-life: workload. Policies from HR will never touch this – indeed, earlier this summer, at the Work and Family Researchers Network Conference, the work-life director from a global corporation spoke for many when she admitted that there were no conversations going on between her group and senior leadership about what level of workload is sustainable for employees.

Overwork is especially hard to fight when the rationale offered is “current business demands.” You know the refrain: “In this market, we’ve all got to work harder.” In other words, work-life integration and well-being are luxuries we can only afford in times of slack resources. There’s a good one-word response to the “business requires working like this” argument, and it technically refers to the waste produced by male bovines. When leaders see work-life as fundamentally about stewardship of human energy, they no longer ask themselves whether business conditions currently favor keeping employees healthy and whole.

9 Habits That Lead to Terrible Decisions

Several years ago we came up with a great idea for a new leadership-development offering we thought would be valuable to everyone. We had research demonstrating that when people embarked on a self-development program, their success increased dramatically when they received follow-up encouragement. We developed a software application to offer that sort of encouragement. People could enter their development goals, and the software would send them reminders every week or month asking how they were doing, to motivate them to keep on going. We invested a lot of time and money in this product.

But it turned out that people did not like receiving the e-mails and found them more annoying than motivating. Some of our users came up with a name for this type of software. They called it “nagware.” Needless to say, this product never reached the potential we had envisioned. Thinking about the decisions we had made to create this disappointing result led us to ask the question, “What causes well-meaning people to make poor decisions?”

Some possibilities came immediately to mind – people make poor decisions when under severe time pressure or when they don’t have access to all the important information (unless they’re are explaining the decision to their boss, and then it is often someone else’s fault).

But we wanted a more objective answer. In an effort to understand the root cause of poor decision making, we looked at 360-feedback data from more than 50,000 leaders and compared the behavior of those who were perceived to be making poor decisions with that of the people perceived to be making very good decisions. We did a factor analysis of the behaviors that made the most statistical difference between the best and worst decision makers. Nine factors emerged as the most common paths to poor decision making. Here they are in order from most to least significant.

Laziness. This showed up as a failure to check facts, to take the initiative, to confirm assumptions, or to gather additional input. Basically, such people were perceived to be sloppy in their work and unwilling to put themselves out. They relied on past experience and expected results simply to be an extrapolation of the past.

Not anticipating unexpected events. It is discouraging to consistently consider the possibility of negative events in our lives, and so most people assume the worst will not happen. Unfortunately, bad things happen fairly often. People die, get divorced, and have accidents. Markets crash, house prices go down, and friends are unreliable. There is excellent research demonstrating that if people just take the time to consider what might go wrong, they are actually very good at anticipating problems. But many people just get so excited about a decision they are making that they never take the time to do that simple due-diligence.

Indecisiveness. At the other end of the scale, when faced with a complex decision that will be based on constantly changing data, it’s easy to continue to study the data, ask for one more report, or perform yet one more analysis before a decision gets made. When the reports and the analysis take much longer than expected, poor decision makers delay, and the opportunity is missed. It takes courage to look at the data, consider the consequences responsibly, and then move forward. Oftentimes indecision is worse than making the wrong decision. Those most paralyzed by fear are the ones who believe that one mistake will ruin their careers and so avoid any risk at all.

Remaining locked in the past. Some people make poor decisions because they’re using the same old data or processes they always have. Such people get used to approaches that worked in the past and tend not to look for approaches that will work better. Better the devil they know. But, too often, when a decision is destined to go wrong, it’s because the old process is based on assumptions that are no longer true. Poor decision makers fail to keep those base assumptions in mind when applying the tried and true.

Having no strategic alignment. Bad decisions sometimes stem from a failure to connect the problem to the overall strategy. In the absence of a clear strategy that provides context, many solutions appear to make sense. When tightly linked to a clear strategy, the better solutions quickly begin to rise to the top.

Over-dependence. Some decisions are never made because one person is waiting for another, who in turn is waiting for someone else’s decision or input. Effective decision makers find a way to act independently when necessary.

Isolation. Some of those leaders are waiting for input because they’ve not taken steps to get it in a timely manner or have not established the relationships that would enable them to draw on other people’s expertise when they need to. All our research (and many others’) on effective decision making recognizes that involving others with the relevant knowledge, experience, and expertise improves the quality of the decision. This is not news. So the question is why. Sometimes people lack the necessary networking skills to access the right information. Other times, we’ve found, people do not involve others because they want the credit for a decision. Unfortunately they get to take the blame for the bad decisions, as well .

Lack of technical depth. Organizations today are very complex, and even the best leaders do not have enough technical depth to fully understand multifaceted issues. But when decision makers rely on others’ knowledge and expertise without any perspective of their own, they have a difficult time integrating that information to make effective decisions. And when they lack even basic knowledge and expertise, they have no way to tell if a decision is brilliant or terrible. We continue to find that the best executives have deep expertise. And when they still don’t have the technical depth to understand the implications of the decisions they face, they make it their business to find the talent they need to help them.

Failure to communicate the what, where, when, and how associated with their decisions. Some good decisions become bad decisions because people don’t understand – or even know about — them. Communicating a decision, its rational and implications, is critical to the successful implementation of a decision.

Waiting too long for others’ input. Failing to get the right input at the right time. Failing to understand that input through insufficient skills. Failing to understand when something that worked in the past will not work now. Failing to know when to make a decision without all the right information and when to wait for more advice. It’s no wonder good people make bad decisions. The path to good decision making is narrow, and it’s far from straight. But keeping in mind the pitfalls can make any leader a more effective decision maker.

When You’re Feeling Down About Your Job, You Seek Brighter Light

In an experiment, people who felt more hopeless about the economy and their employment opportunities showed a preference for brighter lighting, suggesting that those with poor job prospects may have an unfortunate predilection for spending more on electricity, says a team led by Ping Dong of the University of Toronto. The researchers calculated that it would cost participants an average of 20.6% more for electricity in order to feel 1 point less hopeful (on a 9-point scale) toward the economy. Hopelessness can darken people’s perception of brightness, increasing their desire for more light.

What Unions No Longer Do

Forty years ago, about quarter of American workers belonged to unions, and those unions were a major economic and political force. Now union membership is down to 11.2% of the U.S. workforce, and it’s increasingly concentrated in the public sector — only 6.7% of private-sector workers were union members in 2013.

This isn’t exactly news, and professors and pundits have for years been dissecting the causes of labor’s decline. What doesn’t get talked about so much, though, are the consequences. Income inequality has, for example, become a hot topic. You might think that the dwindling away of an institution that devoted much of its energy to equalizing incomes would be a big part of that discussion. It hasn’t been.

Jake Rosenfeld, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Washington and a past and, one hopes, future contributor to HBR.org, is out to change that. His book What Unions No Longer Do, published earlier this year by Harvard University Press (only the most distant of relations to Harvard Business Review), is an account of Rosenfeld’s attempt to empirically establish (mainly through a lot of regressions of data from the Current Population Survey, the American National Election Studies, and the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service) the consequences of Big Labor’s decline.

I had heard good things about the book, and for the last few months it’s been sitting near the top of my to-read pile, taunting me. With Labor Day coming up, I figured I should just go ahead and read it. Now I have. It is in fact a good book — careful, wonky, and for the most part not all that hard to read — and an important one for anyone trying to understand the current state of the U.S. economy and politics. You should buy it. But in case you don’t, here, for Labor Day, are the four big things that, according to Rosenfeld, unions in the U.S. no longer do:

Unions no longer equalize incomes. Income inequality (as measured by what the 90th percentile worker makes vs. the 10th percentile worker) remains much lower among unionized workers than nonunionized workers. But remember, only 11% of U.S. workers are now unionized, and Rosenfeld shows that unions’ ability to affect wages for nonunion workers in the same region or industry sector — which used to be significant — is now negligible. Rosenfeld estimates that about a third of the rise in income inequality since the 1970s is due to unions’ decline — the same share that he attributes to economists’ favorite explanation for rising inequality, rising rewards to skilled workers due to technological change.

Unions no longer counteract racial inequality. As Rosenfeld acknowledges, labor unions in the U.S. don’t have the greatest history on race. For a long time many unions wouldn’t let African-Americans join, and some fought hard to keep employers from hiring them. But during World War II this began to change, and by the 1970s black workers were more likely to be in unions than white workers were. Unions shepherded millions of their African-American members into the middle class, and helped bring black and white wages closer together. Since unions fell into sharp decline in the private sector in the 1970s, the private-sector wage gap between blacks and whites has grown. In the much more unionized public sector, the wage gap has narrowed for black men, although black women have lost some ground to white women.

Unions no longer play a big role in assimilating immigrants. Unions also don’t exactly have a stellar history of relations with recent immigrants to the U.S. But in the first half of the 20th century immigrants still found their way in great numbers into unions and even union leadership roles. For the recent great wave of Hispanic immigrants, that hasn’t been the case. Yes, there have been a few noteworthy unionization campaigns among immigrants, like the United Farm Workers in California’s fields and the Service Employees International Union’s efforts among office janitors and hotel workers. But on the whole, Hispanics are less likely to be union members than other workers are.

Unions no longer give lower-income Americans a political voice. The higher your socioeconomic status, the more likely you are to vote and to be listened to by politicians. As political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page documented in a much-discussed recent study, the policy preferences of organized interest groups and Americans in the 90th income percentile seem to carry a lot more weight in modern political decision-making than those of the 50th percentile. Unions used to be perhaps the most important organized interest group, and Rosenfeld shows that, even now, union members with low education levels are much more likely to vote than non-members with low education levels. But public-sector union members are more educated and more affluent than the population as whole, while private-sector union members are a dwindling and in many ways privileged breed. Not only are unions a much weaker political force than they used to be, they also no longer really represent those at the bottom of the economic ladder.

The decline of unions in the U.S. has often been painted as inevitable, or at least necessary for American businesses to remain internationally competitive. There are definitely industries where this account seems accurate. Globally, though, the link between unionization and competitiveness is actually pretty tenuous. The most heavily unionized countries in the developed world — Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, where more than 65% of the population belongs to unions — also perennially score high on global competiveness rankings. The U.S. does, too. But France, where only 7.9% of workers now belong to unions (yes, France is less unionized than the U.S.), is a perennial competitiveness laggard.

And even if the decline of unions was inevitable or desirable, that still leaves those tasks unions once accomplished — which on the whole seem like things that are good for society, and good for business — unattended to. Who’s going to do them now?

Marina Gorbis's Blog

- Marina Gorbis's profile

- 3 followers