Bryn Hammond's Blog, page 9

October 26, 2013

Translations of The Secret History

Available English translations of The Secret History of the Mongols, with my (personal) notes on them.

Francis W. Cleaves

Francis W. Cleaves

The Secret History of the Mongols, Translated and edited by Francis Woodman Cleaves, Harvard University Press, 1982

The translation I’m fondest of: Francis W. Cleaves, who has run afoul of the majority for his attempt at a King James Bible English. He argued that he should be archaic, like his original, and that the King James style was ‘singularly consonant’ with the matter in hand. Dammit, he was right. Isenbike Togan defends this style, which grants to the oral tradition of history, not just its true dignity but its true weight and strength for people of the time. Cleaves is obscure, but often because he is over-exact.

Sorry, but I find him more in sympathy with the material than other translators — which includes Igor de Rachewiltz. The latter you need too for study, because of its hundreds of pages of notes. Cleaves meant to put out a second volume with his notes, but never did: this volume only has brief footnotes.

The Francis W. Cleaves translation — alongside translations into other languages — can be downloaded in pdf at Monumenta altaica

Urgunge Onon

Urgunge Onon

The Secret History of the Mongols: The Life and Times of Chinggis Khan, Translated, Edited and with an Introduction by Urgunge Onon, Curzon Press, 2001

I like this for Urgunge Onon’s notes and material fore and aft. Certainly better annotated than the Cleaves (who meant to put his notes into a second volume that never saw the light of day). Maybe this version is the best of both worlds: not off-putting for non-scholars, but with Urgunge’s knowledge on Mongol lifestyle and culture.

Igor de Rachewiltz

Igor de Rachewiltz

The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century, Translated with a historical and philological commentary by Igor de Rachewiltz, Brill, 2004. Two volumes.

My complaint with this edition of the Secret History — unarguably the scholarly edition — is how frequently, in the notes, he’ll say ‘this issue has been discussed by [insert names] so I won’t comment on those lines.’ I’m an amateur Mongolist, at home, and for me, that’s an intensely frustrating habit.

I prefer the translation of Cleaves, if only perhaps for its greater art. The notes here… I can’t call them exhaustive, because of what he leaves out (see above). Detailed, although, I’d venture to say, more at home in language than in culture study.

Paul Kahn

Paul Kahn

The Secret History of the Mongols: The Origin of Chingis Khan, An Adaptation by Paul Kahn

He calls this an adaptation, not a translation, and that’s my note of caution. It interprets for you, and often, I think, chooses a simple meaning out of several. Still, it’s great for an easy-to-get and unfrightening English version. I love the Cleaves — Francis Woodman Cleaves whose translation he uses for this, but whose language he changes. Even though Cleaves’ presentation, the intro and how he sets out the text, is only fit to baffle you, and he never did publish the second part: the notes.

Urgunge Onon is another alternative: strictly a translation, but meant for a general audience.

Arthur Waley

Arthur Waley

The Secret History of the Mongols and Other Pieces, (translated by) Arthur Waley, House of Stratus, 1963, 2002

This is an anthology of texts from China, Japan, Korea. If The Secret History is what you’re after, Waley only gives extracts. As he says himself, “Of The Secret History, I have translated only the parts founded on story-teller’s tales.” Whatever he means by that, it’s loose translation, story-style. He says he doesn’t believe in its historical value, so you won’t get the text as document here.

I won’t comment on what the cover tells you: “A saga of epic battles, betrayal, love, tyrants and prisoners in Ancient China”.

October 23, 2013

link: Perceptions of Genghis in Mongolia today

Worth a link: an interview by Harvard Asia Pacific Review with Dr Ts. Tsetsenbileg, a sociologist who researches what the figure of Genghis Khan means in Mongolia today. How deep is he in the Mongolian psyche — after decades of the negative Communist image of him? Where does he help, as a social tool, with the tensions between traditional values and modernisation?

http://www.hcs.harvard.edu/~hapr/winter00_millenium/Genghis.html

September 28, 2013

A court on horses: Khitan painting

A little gallery-post: Khitan painters of court life in the north. [1]

A little gallery-post: Khitan painters of court life in the north. [1]

Above we have the prince of the eastern circuit Dongdan — given as a principality by Abaoji to his first son Bei. This work was once attributed to Bei, a poet and painter. His father, founder of the conquest state, wished him to succeed, but even Abaoji failed to foist first-son succession upon the old tribal order, and Bei was exiled to China. From there he sent intelligence back home, and his paintings were of home, never mind that they had thought him “too Chinese” to head the state. Here’s ‘The Prince of Dongdan Rides Out’ in parts:

This is one, if lesser in splendour, still ascribed to Bei:

And this is by a painter named Hu Gui, a Khitan of the 10th century. It’s known as ‘Rest Stop for the Khan’ and has a Khitan khan and his wife on a rug, with musicians, amongst their nomad court. The painter’s life overlaps Abaoji’s, but I don’t know that we can identify the khan:

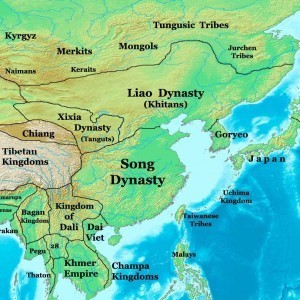

[1] The Khitan of Khitai or the Qidan. In my novels I call them Qatat and their state Qatay, in part because I’m in Mongol speech and in part to suggest our old word Cathay. Khitan fame stuck and North China was known by their name throughout Central Asia and onwards, for centuries afterwards. The Liao Dynasty (dates 907-1125) is the Chinese name, inconsistently used by the Khitan themselves. Here’s a map, and for further information, the Wikipedia entry isn’t bad.

September 24, 2013

A recommendation

This is simply a recommendation, for a novel that has nothing to do with the usual subject of this blog. But I also like to support indie publishing.

This is simply a recommendation, for a novel that has nothing to do with the usual subject of this blog. But I also like to support indie publishing.

I read Port Royal in May 2012, and it’s been a highlight of my historical fiction explorations over the past couple of years. Trad authors, famous authors, dead authors have had trouble to beat this one. I’d line it up for historical fiction prizes, and vote for it over Hilary Mantel. That’s how I feel, and this is a challenge to you to try the first few pages. Because the first page screamed the book’s quality to me.

Here’s a link to my review on Goodreads.

September 21, 2013

Did Jamuqa shoot in the wrong direction?

Mine does, “incorrigibly”. How radical is this in the field of Jamuqa studies? Who else has him so?

Mine does, “incorrigibly”. How radical is this in the field of Jamuqa studies? Who else has him so?

A couple of biographies at least contemplate the idea. Michel Hoang is convinced in his Genghis Khan, and if you forgive the archness of his presentation I’ll quote him.

From a section he titles ‘A Strange Friendship’: “Rarely has the chronicler of The Secret History spoken so effusively or at such length about love… Jamuqa was suspected by Temujin’s wife and mother of having ignored ‘proper manners and customs’. Is this to be understood as an allusion to the private habits of Jamuqa…? Did the ‘sworn brotherhood’ conceal some other intimacy? Like the Sinologue Arthur Waley, the Mongolist Paul Pelliot claims not to know the significance of the line, ‘they slept together under the same blanket.’ However, the clause ‘they loved each other’ repeated four times in just a few lines, lends weight to the theory that this was a special kind of friendship taken to its conclusion. One cannot speak with any certainty on this point… however, there is only one inference to be drawn.”

Qorchi’s dream, after Temujin and Jamuqa have quarrelled, “adds to the ambiguity surrounding the anti-hero, Jamuqa.” Hoang relates the dream, in which Jamuqa is symbolised by a cow who knocks her horn off and Temujin by a hornless bull, and asserts that it “does little to dispel the equivocal character of Jamuqa.” [pp.100-1]

I have to quote one other thing from Hoang. In a section titled ‘The Tragedy of Jamuqa’ he puts forth the opinion, “The story of this strange pair and its disturbing denouement might have inspired Shakespeare.” Amen. If only Shakespeare had got his hands on the Secret History of the Mongols. Hoang gets his teeth into it, the Jamuqa and Temujin bits, like an incipient novelist – and he even attributes to Jamuqa “incontrovertibly a greatness of soul”. [pp. 140-1] But this is a tangent, isn’t it, Jamuqa?

Go on, then. Tell them I’m gay.

You just made sense that way, Jamuqa.

I never did.

I do have a note on this, at the end of Tribal Brawls/The Sheep from the Goats. Wherein I don’t offer much grounds but my gut feelings or a novelist’s logic. (… ‘It’s just that he’s fascinated by Temujin his whole life and his life hung together that way, he came across that way to me, and he’s such an outsider, too.’…) Another novelist, Pamela Sargent in Ruler of the Sky, has him in love with Temujin, although he’s Bad Jamuqa.

A second biography I want to quote has a more sensible tone. Doeke Eisma in Chinggis Qan and the Conquest of Eurasia concludes that Jamuqa was the major emotional involvement of Temujin’s life: “Jamuqa seems to have been the only person for whom Chinggis had strong personal feelings, much more intense than for his wives, or he may have kept them more private, so that they are hardly recorded. He clearly fell in love with Qulan and the only record of an intimate gesture is when he was glad to find Borte again after she was kidnapped by the Merkit. With Jamuqa things were different… There was in Jamuqa a mixture of love, jealousy and hatred… It is not clear to what extent homosexual love was also involved, but their relation certainly was tragic.” [p.53]

Qulan I’ve named Ulun, Brown Usun’s daughter near the end of Tribal Brawls. Later he takes her with him on the Turkestan campaign, when Borte has to mind the home camp. Then, to be equal, he takes Yisui on his last campaign in Tangut.

On his wives, the above is better than what I’ve seen in several places: that he evinces no particular affection toward any one woman. How the heck would we know, is the first thing to ask. I’d say – against the above – the evidence is there for Borte. However, “with Jamuqa things were different,” in that the Secret History is drenched in emotional description. Most biographers take this with more or less of your cynical salt. But what the Secret History tries to tell you is, whether love or friendship, Jamuqa was the big emotion of his life. I think the cynical lenses lead us astray too often with old cultures, but… that’s getting into deep water. This is a short post.

The second biography quoted was self-published at Lulu and seems to have lost its availability. No ebook. It began as an annotated translation of Rene Grousset’s old Conqueror of the World, until the annotations took over. Rene Grousset certainly gives us a highly charged Temujin and Jamuqa (where both are great-hearted, quite often) – no mention of sexuality, but he too puts Jamuqa at the centre of Temujin’s life, and enters into the spirit of the text. I love his book.

Jamuqa, if I may invite you to comment? The last word is yours.

Can you do a post about my military genius?

September 20, 2013

Did Jamuqa shoot in the wrong direction?

Mine does, “incorrigibly”. How radical is this in the field of Jamuqa studies? Who else has him so?

Mine does, “incorrigibly”. How radical is this in the field of Jamuqa studies? Who else has him so?

A couple of biographies at least contemplate the idea. Michel Hoang is convinced in his Genghis Khan, and if you forgive the archness of his presentation I’ll quote him.

From a section he titles ‘A Strange Friendship’: “Rarely has the chronicler of The Secret History spoken so effusively or at such length about love… Jamuqa was suspected by Temujin’s wife and mother of having ignored ‘proper manners and customs’. Is this to be understood as an allusion to the private habits of Jamuqa…? Did the ‘sworn brotherhood’ conceal some other intimacy? Like the Sinologue Arthur Waley, the Mongolist Paul Pelliot claims not to know the significance of the line, ‘they slept together under the same blanket.’ However, the clause ‘they loved each other’ repeated four times in just a few lines, lends weight to the theory that this was a special kind of friendship taken to its conclusion. One cannot speak with any certainty on this point… however, there is only one inference to be drawn.”

Qorchi’s dream, after Temujin and Jamuqa have quarrelled, “adds to the ambiguity surrounding the anti-hero, Jamuqa.” Hoang relates the dream, in which Jamuqa is symbolised by a cow who knocks her horn off and Temujin by a hornless bull, and asserts that it “does little to dispel the equivocal character of Jamuqa.” [pp.100-1]

I have to quote one other thing from Hoang. In a section titled ‘The Tragedy of Jamuqa’ he puts forth the opinion, “The story of this strange pair and its disturbing denouement might have inspired Shakespeare.” Amen. If only Shakespeare had got his hands on the Secret History of the Mongols. Hoang gets his teeth into it, the Jamuqa and Temujin bits, like an incipient novelist – and he even attributes to Jamuqa “incontrovertibly a greatness of soul”. [pp. 140-1] But this is a tangent, isn’t it, Jamuqa?

Go on, then. Tell them I’m gay.

You just made sense that way, Jamuqa.

I never did.

I do have a note on this, at the end of Tribal Brawls/The Sheep from the Goats. Wherein I don’t offer much grounds but my gut feelings or a novelist’s logic. (… ‘It’s just that he’s fascinated by Temujin his whole life and his life hung together that way, he came across that way to me, and he’s such an outsider, too.’…) Another novelist, Pamela Sargent in Ruler of the Sky, has him in love with Temujin, although he’s Bad Jamuqa.

A second biography I want to quote has a more sensible tone. Doeke Eisma in Chinggis Qan and the Conquest of Eurasia concludes that Jamuqa was the major emotional involvement of Temujin’s life: “Jamuqa seems to have been the only person for whom Chinggis had strong personal feelings, much more intense than for his wives, or he may have kept them more private, so that they are hardly recorded. He clearly fell in love with Qulan and the only record of an intimate gesture is when he was glad to find Borte again after she was kidnapped by the Merkit. With Jamuqa things were different… There was in Jamuqa a mixture of love, jealousy and hatred… It is not clear to what extent homosexual love was also involved, but their relation certainly was tragic.” [p.53]

Qulan I’ve named Ulun, Brown Usun’s daughter near the end of Tribal Brawls. Later he takes her with him on the Turkestan campaign, when Borte has to mind the home camp. Then, to be equal, he takes Yisui on his last campaign in Tangut.

On his wives, the above is better than what I’ve seen in several places: that he evinces no particular affection toward any one woman. How the heck would we know, is the first thing to ask. I’d say – against the above – the evidence is there for Borte. However, “with Jamuqa things were different,” in that the Secret History is drenched in emotional description. Most biographers take this with more or less of your cynical salt. But what the Secret History tries to tell you is, whether love or friendship, Jamuqa was the big emotion of his life. I think the cynical lenses lead us astray too often with old cultures, but… that’s getting into deep water. This is a short post.

The second biography quoted was self-published at Lulu and seems to have lost its availability. No ebook. It began as an annotated translation of Rene Grousset’s old Conqueror of the World, until the annotations took over. Rene Grousset certainly gives us a highly charged Temujin and Jamuqa (where both are great-hearted, quite often) – no mention of sexuality, but he too puts Jamuqa at the centre of Temujin’s life, and enters into the spirit of the text. I love his book.

Jamuqa, if I may invite you to comment? The last word is yours.

Can you do a post about my military genius?

September 9, 2013

Ogodei’s deeds and misdeeds

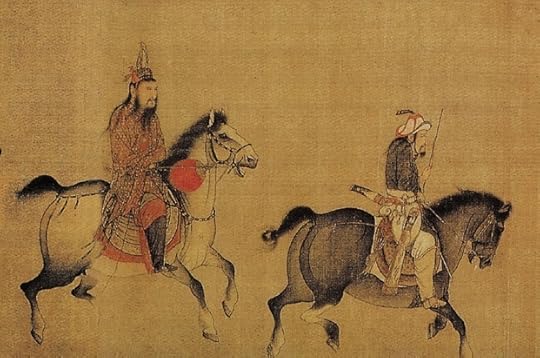

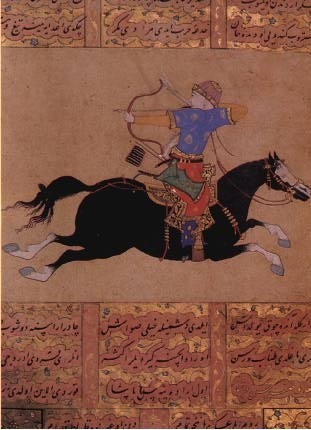

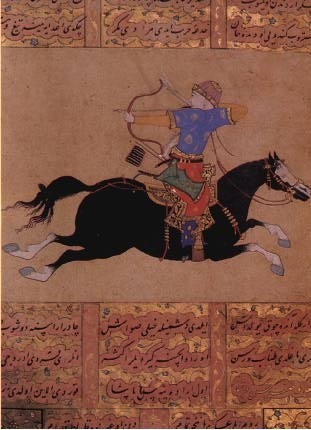

{Chinggis and three sons, from the Persian histories, 15th century. Perhaps Ogodei is in between, as he was, and little brother Tolui holds the horse.}

{Chinggis and three sons, from the Persian histories, 15th century. Perhaps Ogodei is in between, as he was, and little brother Tolui holds the horse.}

In the last passage of the Secret History, Ogodei, son and khan after Chinggis, lists eight deeds of his khanship: four deeds that have been to the betterment of his people and four ill deeds.

Was this traditional, that a king give a reckoning of his services and his sins – an even-handed one, perhaps, with equal count on either side, to be humble? Or is this Ogodei, which you can imagine of him from the anecdotes told about him in Juvaini? Is this Ogodei in emulation of his father, whose own admission of ill deeds allowed the Secret History to tell them?

Fascinating questions. Today I’m attempting investigation and I thought the passage worth a look. It seems to have a sense of a tradition. What with the four + four and statements that might be formulas: “Although I be the Qahan, Lord of the Nation, to deliver myself unto deeds which were errors without principle, this was one of my wrongs.”

The Francis W. Cleaves translation can be downloaded in pdf at Monumenta altaica. I shall quote the passage – #281 of The Secret History of the Mongols – in his translation.

The misdeeds come second, so hang in there.

If anyone can help my researches with hints towards a tradition, or a background, for this public confession of Ogodei’s, I beg you do so. One editor of the text, Igor de Rachewiltz, suggests it is a posthumous assessment put into his mouth, but I’d be reluctant to take his confession off him, or change events as given, unless I have to. First, seek reasons why it may be as the Secret History says, that’s my approach.

#281

When Ogodei Qahan spake, he said, “[After] sitting on the great throne of my father, [as to] that which I did after my father the Qahan, going a warfare unto the people of the Jaqud, I destroyed the Jaqud people. [As to] my second deed, [I] made one to establish post stations for that Our messengers, hasting on the way, make speed, and again for that [We] make [them] for to convey our need and necessities. [As to] yet another deed, making [one] to dig wells in places without water, making [one] to bring them forth, [I] made [one] to bring the nation and the people unto water and grass. Again placing spies and tammachin unto the people of cities in divers quarters, of the nation and the people, causing [them] to set [them], I caused

The feet to be

On the ground

The hands [to be]

On the earth.

After my father the Qahan [I] added [these] four deeds [to all those done by him]. And, again, being made to sit on the great throne by my father the Qahan, being gone, carrying [as a burden] upon myself my many people, then, to be conquered by grape wine was my wrong. This was one of my wrongs. [As to] my second wrong, to hearken unto the word of a woman without principle and to cause [one] to bring the daughters of the ulus of Uncle Odchigin were [mine] errors. Although I be the Qahan, Lord of the Nation, to deliver myself unto deeds [which were] errors without principle, this was one of my wrongs. Again secretly to harm Doqolqu [was] one wrong. If one say, ‘How [was it] a wrong?,’ secretly to harm Doqolqu which, in the service of his proper [lord], my father the Qan, pressed forward was a wrong and an error. Now, in the service of me, who will so press forward for [me]? I myself have declared as wrong the fact that, not comprehending, I secretly harmed a man which, in the service of my father the Qahan and [of] all, was prudent [in] principle. Again, being covetous, saying, ‘I fear lest the wild beasts which were born having [their] destiny from Heaven and Earth will go toward [my] brethren,’ making one to build in beaten earth fences and walls [to contain the prey], as I was [thus] staying [them], I heard words of murmuring from the brethren. It, also, was a wrong. After my father the Qahan, I added four [good] deeds [to all those done by him] and four deeds were wrongs.”

#

The Jaqud = North China.

I’m glad he beats himself up about Doqolqu, known to us among his dad’s comrades. – Whether ‘harm’ indicates murder we don’t know, we only guess. And the women? Guesses and gossip, but again, we don’t know the story. As Cleaves notes, “Of the eight deeds… there is no mention elsewhere in the Secret History of the four which are enumerated as ‘wrongs’.” That’s telling, too…

August 26, 2013

The Secret History: a crying need

You’d think the Secret History of the Mongols had been studied to death, but it hasn’t, or not in English. There is one need that I see and I’m going to talk about here. It is, for those with a written arts background to take a look.

You’d think the Secret History of the Mongols had been studied to death, but it hasn’t, or not in English. There is one need that I see and I’m going to talk about here. It is, for those with a written arts background to take a look.

I’m an old English student… majored in medieval history too, but English was my thing. I know I see the Secret History differently than an historian – I come to conclusions from different evidence. Hell, I hang arguments off psychological signals in the text, and I don’t catch historians doing that, nor do I expect to. God knows I’m no historian, and in their field I’m dependent upon them, but on the other hand I have thought more than once or twice, ‘haven’t they noticed this?’ And that’s from arts criticism.

While working with the Secret History I came up with thoughts… inevitably… which I’ve written into the novel. Whatever cases I make, I make them more persuasively in fiction. Why can I put my ideas better in fiction? Maybe because they rest on little signs and usages of fiction. The Secret History is art, you see, and the trouble is, it rarely has been studied in the Written Arts Dept. It’s seen to belong to History and historians study it.

While working with the Secret History I came up with thoughts… inevitably… which I’ve written into the novel. Whatever cases I make, I make them more persuasively in fiction. Why can I put my ideas better in fiction? Maybe because they rest on little signs and usages of fiction. The Secret History is art, you see, and the trouble is, it rarely has been studied in the Written Arts Dept. It’s seen to belong to History and historians study it.

From me, if I were set this in English class, you’d get an essay on the psychological clues in the text. I don’t want to reduce to an essay what I’ve built now with story-materials, that these days seem subtler than an essay – I’ve been reluctant to ‘extract’ my speculations into a blog post. Besides I lack credentials. I’ll admit to you that the original Mongolian is a closed book to me… I do what I can to study at word-level from the editions available [see my Goodreads shelf of editions]. Obviously – but unfortunately, I often think – I can’t write an article on the Secret History that argues my arguments. At times I wish I were an historian – except the point is I need to keep the English student in me. Clearly we need a person who is both, or we need a cross-pollination of ideas: the Secret History shouldn’t belong only to the History Dept, where eyes are shut – trust me on this – to what can be seen over in Written Arts.

From me, if I were set this in English class, you’d get an essay on the psychological clues in the text. I don’t want to reduce to an essay what I’ve built now with story-materials, that these days seem subtler than an essay – I’ve been reluctant to ‘extract’ my speculations into a blog post. Besides I lack credentials. I’ll admit to you that the original Mongolian is a closed book to me… I do what I can to study at word-level from the editions available [see my Goodreads shelf of editions]. Obviously – but unfortunately, I often think – I can’t write an article on the Secret History that argues my arguments. At times I wish I were an historian – except the point is I need to keep the English student in me. Clearly we need a person who is both, or we need a cross-pollination of ideas: the Secret History shouldn’t belong only to the History Dept, where eyes are shut – trust me on this – to what can be seen over in Written Arts.

So what did I learn from the Secret History that I feel hasn’t been studied? My main contention – it’s there to be torn down – is that Chinggis himself contributed to the Secret History. That we can trace his memories, therefore his thoughts and attitudes. I was led to the deduction that he himself tells us the story of the murder of his half-brother, and then you ask why he told us? Also I like to look at how the artist – for I believe one can be distinguished – lent his own voice to what he told us. I believe there is much more to be learnt, about Mongol attitudes and about individuals, than has been found. Yes. That’s cheeky of me, but it is my conviction, old English student that I am. A sensitive eye, used to analysis of written arts, has things to see in the Secret History that no, I haven’t read in the history books’ discussions.

So what did I learn from the Secret History that I feel hasn’t been studied? My main contention – it’s there to be torn down – is that Chinggis himself contributed to the Secret History. That we can trace his memories, therefore his thoughts and attitudes. I was led to the deduction that he himself tells us the story of the murder of his half-brother, and then you ask why he told us? Also I like to look at how the artist – for I believe one can be distinguished – lent his own voice to what he told us. I believe there is much more to be learnt, about Mongol attitudes and about individuals, than has been found. Yes. That’s cheeky of me, but it is my conviction, old English student that I am. A sensitive eye, used to analysis of written arts, has things to see in the Secret History that no, I haven’t read in the history books’ discussions.

Even I, just a novelist you know, without Mongolian in my kit, fancy I have new things to say about the Secret History. I didn’t mean to have new things to say, when I began a novel, but the things weren’t said. And they were there, to my eye.

Even I, just a novelist you know, without Mongolian in my kit, fancy I have new things to say about the Secret History. I didn’t mean to have new things to say, when I began a novel, but the things weren’t said. And they were there, to my eye.

A truth an English student learns is that there is no one interpretation of a text, and what I see won’t be what others see (is that different to the discipline of History? I don’t know). But what’s certain-sure is, there is rich material for interpretation, from a written arts perspective.

Notes

I hate the word ‘literature’. I say written arts.

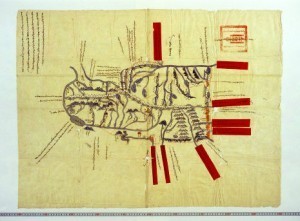

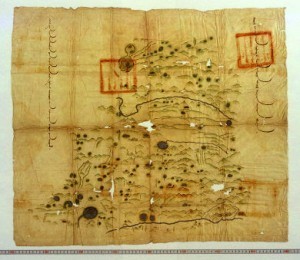

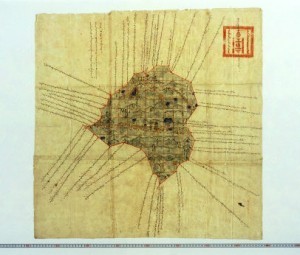

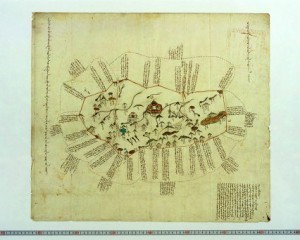

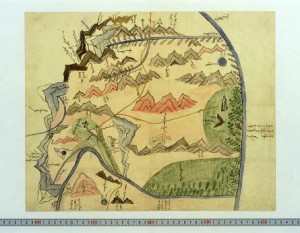

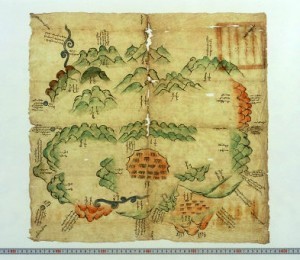

I’ve illustrated this post with 19thC and early 20thC Mongolian maps, because… I’ve just found them and they’re gorgeous. At this site: http://mongol.tufs.ac.jp/landmaps/

August 2, 2013

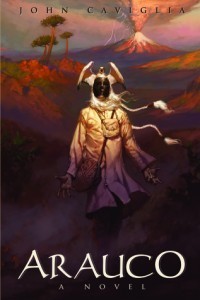

Interview with John Caviglia

“Outside perspectives dismantle the complacent inbuilt bias of cultures, and this dismantlement is at the heart of my novel.”

“Outside perspectives dismantle the complacent inbuilt bias of cultures, and this dismantlement is at the heart of my novel.”

I haven’t done an interview on the blog before, but I took nerve in hand and asked John Caviglia, author of Arauco. I thought Arauco a spectacular book. It stands for me alongside Robert Polevoi’s Port Royal as a major work of historical fiction, independently published. I expect them both to be alive in fifty years (the books not the authors — sorry), in the faith that originality lasts. Ebooks, as we know, last forever; I hope so does major work, even in these new times of trad and indie.

Here’s the interview. My questions, his answers. Links at the bottom, if you first need an acquaintance with the novel.

Arauco gives equal story time to the Spanish and the Mapuche. Was that the way you determined to tell the story, from inception? Do you feel equal-time isn’t often done?

Loving historical novels as I do, and having been born in Chile, when I finally got around to researching a novel I chose Inés de Suárez as the starting point (long story in itself)…. Without knowing it, I had discovered something like a magician’s hat…. Pulling on that first handkerchief, I found it attached to another—Pedro de Valdivia. To that was knotted his enterprise. I kept pulling—the entire emergence fascinating … eventually taking me to Valdivia’s death and the catastrophic defeat of the Spanish by the Mapuche at the battle of Tucapel. This, when Cortez and Pizarro had conquered empires with paltry handfuls of men! It was time to rethink the book and I became fascinated by the fact that no accounting of the Spanish invasion included the Mapuche perspective. So—as I knew almost absolutely nothing about the indigenous people of Chile—I dipped again into that magician’s hat…. When I actually began to write (still researching), my plan from the outset was to devote equal time to both Spanish and Mapuche, though the pressures of storytelling created an evolution in that decision….

Equal-time is seldom done, I think, when both cultures and languages are foreign to the reader, and especially when the novel is set in a different era. So much has to be explained or glossed, simply left out or left to the imagination. Also, in my novel, the landscape, the fauna and flora, are unfamiliar to most readers of English. This is the main reason Arauco is so long. In my blog, www.arauconovel.com, I supplement the novel with image and explanation, that the reader may better see and understand the time and place, and the Mapuche.

What made you choose your main point-of-view characters on each side? I thought your leads more or less unusual choices. For instance, the Mapuche we are most intimate with may be called outcasts. While Juan was idealistic for a conquistador.

Let’s just think of the main point-of-view characters in Arauco as having outside points of view, the outsider as narrator being an old chestnut of a literary convention (Think of Montesquieu’s Persian Letters, in which two visiting Persians attempt to understand 18th century France). Outside perspectives dismantle the complacent inbuilt bias of cultures, and this dismantlement is at the heart of my novel. So, take “equal time” in Arauco to mean that the Spanish and Mapuche cultures are being equally examined from outside by the main characters of the other culture. This interactive inquisition defines the relationship of Juan and Raytrayen, and the difficulty of their love.

Now, in my novel (as in most societies) almost all the characters lead lives largely unexamined—accepting the ‘roles’ in the drama given them by their time and culture. Thus, Pedro de Valdivia and his minions are embarked upon an enterprise in which horse, armor and sword will wrest gold and land from people they have no real interest in. Valdivia wants to conquer, not understand them. As for Lautaro and the Mapuche he led to war against the Spanish, ditto—no real interest, save as how to fight the invaders better. What I needed were characters enough at the “edge” of their culture—outsiders, if you will—to be at least curious about difference. There is a fascinating book by Mary Douglas—Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo—that long ago changed the way I looked at societies. From MD, I derived the notion that cultures have “edges,” and that there, in being different, lies the power given those such as Ñamku. And—though it’s been decades since I read MD—it makes sense to me that the “hearts” of very different cultures can only fight each other—so that whatever meeting there is to be must happen at the periphery.

I chose Ñamku as a principal character because shamanism has always fascinated me. Also, if you examine the Mapuche culture of the time, there was scant choice for a male—you were a warrior, unless something different in you made you shaman—and I needed more than just a warrior’s simple hate as perspective. I made Ñamku albino to give him curiosity about the invaders, creating at least the illusion of kinship with them. Also, to have him yearn for contact.

As for Juan de Cardeña, he was an ‘outsider’ in being educated, a literate conquistador being something of an oxymoron. As secretary to Valdivia, he was also largely outside the action, observing, sometimes quite literally recording it. Also, he was privy to Valdivia’s intentions, and very interestingly close to Inés de Suárez (which made it possible to embed the novel I initially thought to write within a larger novel). And finally, one of the things I wanted to include in Arauco was the astonishing intellectual ferment of the time, which made the invasion of the Americas what it was—so I chose a lettered man as my lead. And being educated at that time in Spain—as Cervantes wonderfully and ironically illustrates with Don Quijote—was likely to make you idealistic.

Did you have a soft spot for Inés de Suárez, the historical/your fictional woman? Or do you believe a novelist ought to be more objective than Henry Fielding who confesses to us his own love for Sophia in Tom Jones? Any thoughts on putting a personality into a once-alive figure from the historical records?

In my novel it is Juan that has a “soft spot” for Inés de Suárez. And it’s due to his perspective that she is presented as she is in the novel, “romantically”—and by this I mean as a character colored by the fictions (the romances) Juan projects upon her. Personally, I see her as a strong, complex and very unusual woman, but still defined by her bloody time and place.

When so few actual facts have been recorded about the historical characters you write about, true objectivity is ultimately impossible, for it would mean knowing what once existed in the blanks you fill. What I attempted in Arauco with all the actual historical characters, both Spanish and Mapuche is a kind of evenhandedness, not demonizing or ensainting….

One of my heroes, Pablo Neruda, loathed Inés de Suárez. In his poem, Valdivia, which poetically recounts the founding of Chile, this is what he says about her:

Completely

soaked by entrails, screaming,

Inés de Suárez, soldier,

supported the imperial necks

with the knees of an infernal harpy.

And she threw them over the palisade,

bathing herself in noble blood.

He is of course referring to the beheading of the six captive Mapuche caciques during the battle of Santiago, and the hurling of their heads over the city’s palisade to “discourage” the attackers (an act I ‘tiptoe around’ in the novel). So yes, I gave Inés de Suárez far more latitude than Neruda does, and maybe more latitude than strict objectivity would require … but then, again, for Juan’s sake.

Ultimately, if “soft spot” means filling in the blanks that History leaves in your characters with good, rather than bad or questionable, then Juan de Cardeña—about whom nothing as an actual human being was recorded—is the ‘softest’ cake that I confected. Chances are excellent that I took a somewhat literate conquistador, brutal as almost every other, and made something richer, deeper and gentler of him.

You have ghastly events to write about. I think I can tell you put a lot of thought into ways to present them. Can you share a few thoughts on how a novelist might write about horrible histories?

War is the axle about which the wheel of Arauco spins—whatever happens on that war’s periphery—and war is never other than brutal and ghastly. As Tostoy writes, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Just so, every war is differently ghastly. What I attempted to do is be a ‘fly on the wall’ at this particular time and place, attempting to record the conflict of Spaniards and Mapuche as it was. Also, the conquistadores were themselves never far from civil war, if not actually engaging in it. This also I record, for that is what was happening, then and there. The horror came with the ‘territory.’ Horrible histories should be written as they were, in my opinion.

My personal, fictional, answer to history’s horrors was to have wonderful things happening at war’s edge, and of course I have Juan flee war, across the Andes, at the end. I wish him well.

How did you research Mapuche shamans? What about your choices, in creation of your shamans’ mental/spiritual world?

I began to research Arauco before there was an internet, but read absolutely everything about the Mapuche available to me at the time (thanks be, for the Library of Congress!). And in reading about Mapuche, one cannot help but repeatedly bump up against shamans and sorcerers, both being so important to their culture. According to traditional Mapuche lore, by and large human illness, and many things that go wrong with your animals or crops are due to sorcery of various kinds. So, if you want somebody sick, you hire a sorcerer. Conversely, if you want that sorcery cancelled, you hire a machi—a shaman—and so it goes…. Most of my information about machi derived from anthropological studies. I learned a lot from the works of Inez Hilger, done in the sixties. More recently, in 1997, Ana Mariella Bacigalupo published a fascinating work devoted specifically to Mapuche shamanism—Shamans of the Foye Tree: Gender, Power and Healing among Chilean Mapuche. If that study had been around when I began to write Arauco, the novel would have been a different thing.

Also, I should mention that I did research not just into shamanism among the Mapuche, but in greater Latin America. This led me to the ritual use of datura stramonium, which is widespread—and the visions of the shamans in the novel follow the characteristic course of that psychoactive plant. Interestingly, this was a time in which visions were also happening in Spain. St. Teresa of Avila was Juan de Cardeña’s contemporary.

How much time have you devoted to the novel? Who or what helped with your labours?

From inception to publication the novel took about three decades (though much of that time was spent on back burners). Through it all my wife, Barbara—who has the patience of angels—provided unfailing support and lucid, ongoing feedback. She also helped with research, which came to include such things as sleeping among chickens in a Mapuche campground in Chile, where a traditional ruka—a Mapuche dwelling—was being built. My brother, Mario, read all three drafts—the first being over a thousand pages, typescript—and his comments resulted in a great improvement and shortening of the novel. And finally, a wonderful book group my wife belongs to, the Sisters in Reading, which definitely does not read FLUFF, was gracious enough to be a focus group for the penultimate draft. I am honored to be the only male ever physically admitted to their conclave.

Who are your writing heroes? And, if these differ, are there writers who fed you for the book?

In my adolescence I must have read every historical novel in the Carnegie Library of Crawfordsville, Indiana (which took time, but was doable). My heroes then were such authors as Robert Graves, Rafael Sabatini, Walter Scott, Alexandre Dumas…. To them I owe my abiding love of literature eloquently transporting one through time and space.

As one born in Chile and brought up in the United States, I owe to Pablo Neruda—whom I read later in life—the realization that one never leaves the place where one was born. With him I also share a love of the land going back to times before history. And I admire him as a man who had principles, and never, ever, compromised them. I just read a wonderful biography by Marie Arana of Simón Bolivar, who liberated much of Latin America from Spain, and one of the things that struck me about his short and brilliant career, is how much he had to violate his beliefs to get done what he believed in. Neruda chose exile over compromise, but his poetry never left Chile.

What’s next?

Far as novels go, I’m thinking of doing another set in Chile. No title. No plot. No anything yet, except the idea of including the infamous Latin American/Nazi connection. There’s a fascinating Chilean called Miguel Serrano, who was an acquaintance of Herman Hesse and C. G. Jung, and became one of the foremost figures in contemporary Nazi “philosophy,” propounding what he called “esoteric Hitlerism….”

Hmmm … far as time and place…. My mother intended to study in France after college, but WWII was breaking out, so she went to study in Chile instead, and arrived to find Valparaíso, and its university, totally destroyed by an earthquake. She traveled down by ship of course, and many of her fellow passengers (according to her letters) were Jews fleeing Europe. Powerful stuff. And then of course, Nazis fled to SA not so many years later…. Am in the research stage right now. Being retired, I may be able to get it done in fewer than thirty years and still live a life on the side.

Arauco: A Novel

by John Caviglia

Paperback, 698 pages

Published November 28th 2012 by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

Kindle Edition, 698 pages

Published February 9th 2013 by Kindle Direct Publishing

John Caviglia’s website

My review of Arauco on Goodreads

End comment from Bryn

I’m glad I asked the questions. I already have Shamans of the Foye Tree and must explore Purity and Danger. I’ve found out that my third novel — the clashes in my third novel — is almost entirely about frontiers (Genghis only fought, you know, where steppe and sown had interpenetrated. The rest came after his lifetime). So John on the “edges of cultures” is valuable to me. Mind I’ve always been one of those who read books like The Outsider…

June 29, 2013

Jamuqa’s goat

Jamuqa just wants to pop up today with his goat.

I don’t know what his goat meant to the Scyths (it’s Scythian gold) but it’s spooky, isn’t it? Fit adumbration of his madness.

I have no other excuse to post. Have a goat, people. — It’s a great goat, Jamuqa, and any time you want to guest-post… you know, when you feel talkative. He doesn’t talk much, folks, in public, so I’ll give him his goat and see if that’s a first step.

If I were to write over, the one thing I’d do that I didn’t do (I guess I’m lucky to have a single regret — at this stage) is treat Jamuqa’s mental illness with more realism. As it is, it’s story and not science. I’ve only gone a touch mad twice and I’ve never hallucinated goats, and I’ve dabbled in serious material on the subject, over my life. One comment I have: from my researches on shamanism I’ve come to the view that mental problems were more acknowledged as the common things they are, in these societies than in our own. In descriptions of Mongolian and neighbour shamanism I have seen said that shamans work with mental ills even more often than they do with physical. Anthropologist Caroline Humphrey lists the tasks of a Daur Mongol shaman and finishes, “Daur shamans were above all invited to cure mental illness and depression.” [Shamans and Elders, Oxford, 1996]. There are a few areas where I think ‘they did better than us’ and mental illness is among them. Our Jamuqa didn’t let a shaman help him, but even so, he might agree.

While we’re here, why don’t we link to the State Hermitage Museum St Petersburg, it’s collection of Scythian antiquities. They have the goat.