Bryn Hammond's Blog, page 12

November 3, 2012

and again, joys of indie

Still on text placement, do your own. With special attention to climactic passages. It’s wonderful how a space, inserted where convenient and unnoticable, that merely shortens a line twenty lines above, gives a new page break which – in the drama of the moment – functions for us, either holds a line back, keeps a paragraph whole, and the sense leaps out unobstructed, undiffused. It’s like poetry, your line and your word placement in poetry.

If I’d known paperbacks were this much fun…

November 2, 2012

joys of indie #103

With paperbacks, you can arrange your text on the page, for the sense. I can set out my sentences, by quietly juggled spaces, not to sprawl sloppily or lurch from page to page, cut in half or quartered where we don’t want an interruption — I can make that brief gap when you have to turn the page, suit or run smoothly, even hide a spoiler. Every page handcrafted, by me, for your experience of the book.

My paperbacks, and my text layout, I don’t doubt, have an indie feel. But that includes lines set out by the writer, with an eye to content, not just neatness.

November 1, 2012

Two months to go

Come January I’m not allowed to read fiction. Two months to wallow.

It isn’t that I’m not allowed, but I’ve had a year off – quite unintentional; publishing proved a fatal interruption to my hermit-writer’s existence, close-closeted with the book. I haven’t written since January, but I’ve shovelled into the abyss that is my life without the book, a record amount of fiction. Because I can’t read fiction while I write. While I write, the whole goal is never to exit the world of my novel; other fictional worlds are too violent a yank. I didn’t read fiction for years. It’s an unfortunate side-effect and one of the prices you pay, happily. Maybe I won’t go back to that extreme closetedness (now I’m online…) and if I can keep up a feed of fiction, I want to. But I have a fixed date when I have to take up work again, no matter what state my head’s in: no excuses from January 19, a year after I published.

In short, I’ve started to think, two months, what novels can I cram in, which can be left out?

October 28, 2012

A batch of fiction

A batch of fiction with a foot, or both feet or heart on the steppe. Links are to my reviews on Goodreads. My reviews can go on a bit, and I don’t like to post content twice.

The Blue Sky

by Galsan Tschinag

Boyhood in the Altai Mountains

“A little tragedy, a child’s tragedy.”

My review

The Gray Earth

by Galsan Tschinag

2nd of three on his youth, between nomad life and Communist indoctrination

“The boy, at 8 and 9 years, knows he wants to be a shaman. Shamans are persecuted and liable to be sent to prison…”

My review

Last of the Amazons

Last of the Amazons

by Steven Pressfield

Speculative historical fiction: Amazons and Greeks

“I had no idea Steven Pressfield had written such a serious contribution to savage/civil arguments.”

My review

The Golden Lynx

The Golden Lynx

by C. P. Lesley

Adventure in Russia, 1534: the infancy of Ivan the Terrible

“…our girl hero whose heart is on the steppe though she’s plunked into Moscow to patch up a feud with a marriage…”

My review

The Day Lasts More than a Hundred Years

by Chingiz Aitmatov

A spaceport on the steppes of Kazakhstan

“A fable.”

My review

Now we’ll go north of the steppe, but stick with shamans.

The Chukchi Bible

by Yuri Rytkheu

Native cultures of Siberia under siege

“The author’s grandfather, whose story is two-thirds of the book, was ‘the last shaman of Uelen’.”

My review

And I’ll throw this in. Far from the steppe, but about the messy intersection of cultures.

Fathers and Crows

Fathers and Crows

by William T. Vollmann

Jesuits in Canada, 1600s. One of his ‘Seven Dreams’ set of novels on the clash of Indians and Europeans in the New World

“In spite of the culture clashes, the Black Crows and the Savages are often strikingly alike.”

My review

October 25, 2012

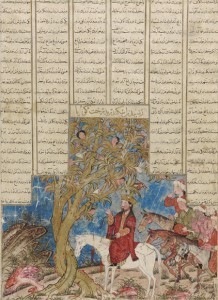

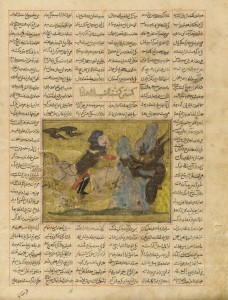

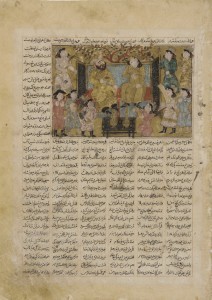

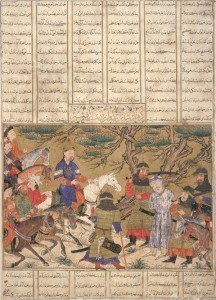

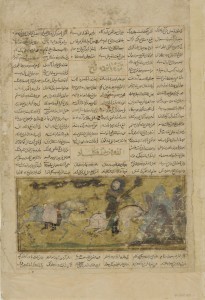

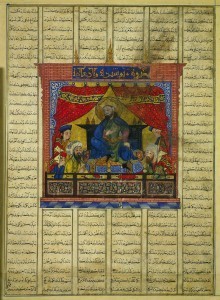

from the Great Mongol Shahnama – 2

Simply pages from the Great Mongol Shahnama. Who needs an excuse? For a quick introduction to this most splendid example of book art from Mongol Iran, see my 1st post so titled. These pages are over half a metre high.

As ever, click to enlarge

“Breadth of conception and sheer physical size, historical focus, astonishing imagination combined with extraordinary material veracity, and a high quality of style and execution: these are among the fundamental differences between what survives of the Great Mongol Shahnama and any of the other illustrated fourteenth-century copies of Firdawsi’s epic.”

- Eleanor Sims, ‘Thoughts on a Shahnama Legacy of the Fourteenth Century’ in Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, editor Linda Komaroff, Brill, 2006.

October 20, 2012

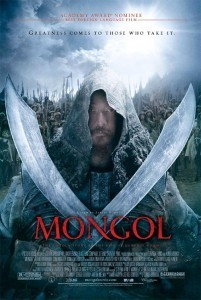

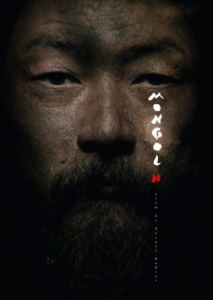

Sergei Bodrov’s film Mongol

I walked into a cinema for this. I’m not a cinema-goer; in ‘recent’ years I’ve made the trip for Lord of the Rings, for The Weeping Camel, and for Mongol.

I walked into a cinema for this. I’m not a cinema-goer; in ‘recent’ years I’ve made the trip for Lord of the Rings, for The Weeping Camel, and for Mongol.

Perhaps that’s why – although I was thrilled to see Temudgin splattered on posters, although I enthused over the results – now I watch again, after a few years’ interval, I see I managed to underrate this film. I don’t have eyes for film.

Jamukha’s tremendous and steals the stage. I remember that’s what reviews said: Jamukha’s a scene-stealer and almost hauls the film out from under Temudgin. Which, of course, is just what he does in the Secret History: almost takes over the story, almost takes over the steppe. I can’t tear my eyes off him when he’s on screen, and that’s only right. Go Jamukha.  He wears such a different face to my Jamuqa that at first I was thrown. But that’s the beauty of him: he’s a gift to any fictionalist, a great anti-hero, and what you do with that potential is up to you. I only hate to see that potential wasted and him narrowed into a villain.

He wears such a different face to my Jamuqa that at first I was thrown. But that’s the beauty of him: he’s a gift to any fictionalist, a great anti-hero, and what you do with that potential is up to you. I only hate to see that potential wasted and him narrowed into a villain.

Borte. When I’m not transfixed by her face – and I am, so I miss what else is going on – she was a hit with the public too. Poor Temudgin, in between these two. He does great. That the film-maker spins his plot around the three of them is the strength, and exactly why the Secret History enchants a story-teller.

Borte. When I’m not transfixed by her face – and I am, so I miss what else is going on – she was a hit with the public too. Poor Temudgin, in between these two. He does great. That the film-maker spins his plot around the three of them is the strength, and exactly why the Secret History enchants a story-teller.

This film is the one fiction on Genghis that I like with a whole heart.

Onto Temudgin. Truth to tell, back then, his portrayal was why I was thrilled with the film. Now… I haven’t written for a year, perhaps I have objective eyes for these my characters with different faces. Now I see more and more Genghis in him. It isn’t just that Bodrov stitches his film together from phrases out of the Secret History and elsewhere (game with the subtitles: how infrequently the talk is mere invention). His Temudgin, to me, is a true portrait, exudes the right scent – I can believe in him. What I saw back then is how his sufferings and his simple fortitude under them – his child’s face in the plank-contraption, his man’s face in the cage – lends him a little of the saint. I think he needs an air of saintliness. Call to mind what a ferocious creature a saint is, before you get me wrong. Bodrov ends his childhood on a miracle: his imprisonment-planks falls off, in the open temple to Tangri, under the eye of the blue-grey wolf. The Secret History tells of miracles at this point, that the man himself believed in.

Captivity in Tangut? It’s one theory, and it’s film shorthand for the manner of wrongs the Mongols feel have been done them. It says well, in that expressive shorthand, what you might write a lot of pages on. I’d bet Bodrov has read his fellow Russian Lev Gumilev, who has a passionate page on these affronts, on the causes of war. He quotes a Chinese witness, Meng Hong, who wrote in 1221:

Captivity in Tangut? It’s one theory, and it’s film shorthand for the manner of wrongs the Mongols feel have been done them. It says well, in that expressive shorthand, what you might write a lot of pages on. I’d bet Bodrov has read his fellow Russian Lev Gumilev, who has a passionate page on these affronts, on the causes of war. He quotes a Chinese witness, Meng Hong, who wrote in 1221:

The head of the Jin exclaimed with alarm, ‘The Tatars will unfailingly be a cause of disturbance to our kingdom!’ Therefore, he gave orders for an immediate attack to be mounted against their remote and desert country. Every three years troops were sent to the north to exterminate and plunder; this was called ‘the reduction of slaves and extermination of people’. Even now they remember in China that for twenty years before this, in Shandong and Hebei, what home had not bought Tatar boys and girls into slavery? These had all been captured by the troops. Those who at the present time are grandees among the Tatars were then for the most part led off into captivity… the Tatars fled into the desert and vengeance entered their blood and brain.

Gumilev comments on this account: “It were better unsaid! What the Chinese scholar described recalls the hunt for Indian scalps organised by the Puritans of New England and the Baptists of Massachusetts, the slave trade of the French and English merchant venturers, the slaughter of the Patagonians undertaken by the Argentine government, i.e. pages of history branded as those most shameful for mankind.”

My guess is, Bodrov draws his history from this page. I thought Temudgin’s dialogue with Tangut, with that governor, with the monk, efficiently sums up much that you can say about his interactions with the settled states.

Bodrov’s only large invention is Borte’s rescue of him from Tangut, and I have excuses to make. It isn’t such a large invention: there were rescues from Tangut – Jaqa Gambu and/or Jaqa Gambu’s daughter. She can be a hero: women were very active participants in Tangut history for a century or two, with the nomad background and the example set by Liao. That she has a daughter unfathered by him, along with Jochi? Why not? He adopted several children from the enemy, a Tangut boy among them. Novelists, none of whom I’ll name, tend to decide it’s a better story if Genghis rejects Jochi. Maybe Bodrov felt the urge to state twice, ‘except he didn’t’.

Bodrov’s only large invention is Borte’s rescue of him from Tangut, and I have excuses to make. It isn’t such a large invention: there were rescues from Tangut – Jaqa Gambu and/or Jaqa Gambu’s daughter. She can be a hero: women were very active participants in Tangut history for a century or two, with the nomad background and the example set by Liao. That she has a daughter unfathered by him, along with Jochi? Why not? He adopted several children from the enemy, a Tangut boy among them. Novelists, none of whom I’ll name, tend to decide it’s a better story if Genghis rejects Jochi. Maybe Bodrov felt the urge to state twice, ‘except he didn’t’.

By now, I know our luck to have this film. Think Genghis cinema, think what you’d expect. Instead we have this.

Mongol, a film by Sergei Bodrov, 2007

Lev Gumilev, Searches for an Imaginary Kingdom: The Legend of the Kingdom of Prester John, English translation by R.E.F. Smith, Cambridge University Press, 1987

October 10, 2012

Blog love with Liebster

Liebster is a nice little contagion going around blogs. A germ of love (it’s from German liebe, love) for lesser-known blogs – under 300 followers – given from blogger to blogger. When you get one, the idea is to share the love with three to five other worthy blogs. At this rate, of course, there won’t be a blog left. But then no blog ought to go unloved. It’s a nice germ, and the fact there’s a person who chose my blog means a lot to me.

Liebster is a nice little contagion going around blogs. A germ of love (it’s from German liebe, love) for lesser-known blogs – under 300 followers – given from blogger to blogger. When you get one, the idea is to share the love with three to five other worthy blogs. At this rate, of course, there won’t be a blog left. But then no blog ought to go unloved. It’s a nice germ, and the fact there’s a person who chose my blog means a lot to me.

My giver is C.P. Lesley, and here’s her blog: blog.cplesley.com, titled Historical Novelist Tackles the Internet Age. Historian by day, she has written The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, a take on the story, and The Golden Lynx, first of five set in the times of Ivan the Terrible Find out about these on her site. We have a common interest in steppe history, and I enjoy her Tatar heroes from the second-mentioned novel.

And now to hand on. This took me a while, because I don’t get out and about much in blog-world – not nearly enough, as I’ve learnt. For when I set out with the task to discover blogs to love, I did. I did discover blogs to love, three of them, and so worthy are they, I won’t search further to make five. This Liebster Award has done wonders for me, in the discovery of blogs.

Now, ignorant as I am in blog-world, I didn’t rudely inquire into what hordes of followers these blogs have, or not. Me, I don’t even have a follow button. But this Liebster Award is a germ, like I say, freed into the world by nobody knows who, and qualifications and protocols… I Googled for them, but obviously to me, follow the spirit and otherwise make up your own. Blogs whom I award: feel free to ignore this whole affair. Or whatever. I’ll notify them as I’m meant to.

The first one I found: mongolianecologyculture.wordpress.com

Titled Mongolian Climate, Ecology & Culture

By fieldworkers in Mongolia who study the environment – with an eye to history. Their latest project is to determine whether a wetter, warmer climate in the 13th century led to the Mongol surge under Chinggis Khaan. It has great info, great images (don’t miss the photographs of ancient Siberian pines), lots of general enlightenment beyond the specific study, natter about Mongolia. Thanks for doing a blog, people.

Next I found the Silk Road Blog of Hans van Roon: mongolschinaandthesilkroad.blogspot.com.au

Titled Marco Polo, Genghis Khan, China and the Silk Road

It’s fantastic, a treasure-house: covers museum exhibitions, alerts you to new books, trawls the archaeological news, directs you to other resources – as rich as the Silk Road. For any person with an interest in these areas.

Thirdly I stumbled on Pamela Toler’s blog:

www.historyinthemargins.com

Titled History in the Margins

This came up in my searches because Pamela has an old post on my guy Genghis, which begins: ‘I want to make it clear right from the beginning that I think Genghis Khan and the Mongol hordes have gotten a bum rap in the annals of history…’ and goes on ‘…the man I like to call Genghis the Great…’ Now this is the way to my heart. But the more I delve the more I like the blog, and the mind behind the blog, and the way she talks. Her interests and knowledge are nothing if not far-flung.

That’s it from me. Three very worthy, and again, C.P. Lesley, thanks for the experience.

September 27, 2012

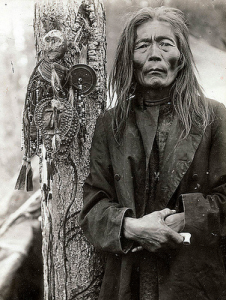

How to deal with old religion – 1

Fugitive shaman chased by a photographer

To Soviet anthropologists, shamans had to be either insane or conscious frauds. With this assumption they set out to study them.

And what are our assumptions? Aren’t they uncomfortably alike? It’s troubled waters for your average rationalist who’s sworn, on heavy forfeits, not to demean the people she writes about – that’s me.

Me and where I start from, my axiom and vow: These people were as intelligent as you and I. Do not dumb them down. Because dumbing-down is oh so easily done in the area of old or obsolete religion, but remains an error and an insult and they ought to haunt you for it. Science can tell you brains haven’t evolved since the 13th century. Don’t just pay lip service to that, implement it in every sentence you write about them, or may they blow rude noises at you.

I have to assume the opposite of a Soviet scientist – mostly. Insanity has traits in common, you might say, and can give clues. Fraud? Shamans were aware of an audience, and a few tricks up one’s sleeve won’t go amiss: I’ve seen that cheerily admitted by shamans who take their real work very seriously. There are levels. It was always hard to get a shaman to give an ‘authentic performance’ in front of a scientific observer. When observation proved impossible to ignore a shaman might have to act, and overact.

Putting on the spooky

You’ve never met a more determined set of religion-bashers, believe me, than Soviet-era anthropologists, whose reports are a big percentage of what we have on still-living, still-functioning shamans, before the shop closed down (it’s open again, sort of). A thing they mightn’t have expected – and we mightn’t either – is the critical spirit that pertained. Shamans were used to an audience, and a sceptical one. That audience – that clientele – is on the alert for tricks, and familiar with shamanry; the scientists found them far from dupes, ready to believe whatever was thrown at them. They had stern tests for their shamans, and if they weren’t bamboozled they weren’t impressed. It’s when the shamans managed to flummox this audience that the scientists too scratch their heads.

The anthropologists have to record instances they can’t explain. It can be stunts with knives and fire, but often it’s knowledge: shamans earn a hard-earnt trust with pieces of knowledge – maybe trivial, maybe irrelevant to the case in hand – and though the anthropologists impute to them an espionage of the class they have back home, they’re left with unexplainables.

Watch what you say about me

That’s why I put an unexplainable into my story. Because if I didn’t, I’d be false. Shamanship was such an art a Soviet scientist can’t see to the bottom of it: how the heck would I? I’m not without a partial theory on how my shaman knows what she knows, but if I presented my shamans as fully transparent to you and me, I’d be untrue – and unjust – to historic shamans. My aim is to be true to life. Me pretend to understand a shaman? No, that’s not true to life.

As for shamans’ insanity… I’ll leave that for another post. Maybe Jamuqa can guest-post on that, being loopy as a Merqot lasso.

[Jamuqa’s voice] If that’s an attempt to stir me up into a guest-ghost-post, try harder.

Jamuqa, that’s about as dirty a thing as I can say to you.

I noticed. What’s with that?

You’ve infected me.

Our first shaman clutches his drum against intrusion. These photographs are telling, aren’t they?

September 16, 2012

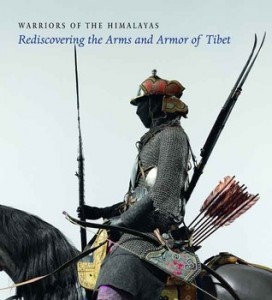

Tibetan Arms and Armour

In this book was the inspiration for Jamuqa’s prize arm-guard and Hoelun’s trophy stirrups – among other items.

In this book was the inspiration for Jamuqa’s prize arm-guard and Hoelun’s trophy stirrups – among other items.

You can see the arm-guard, thanks to Google Books. And here’s the exhibition page at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.This book is the catalogue… it’s funny to call these glorious books catalogues.

Donald J. LaRocca, Warriors of the Himalayas: Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet, Yale University Press, 2006

September 9, 2012

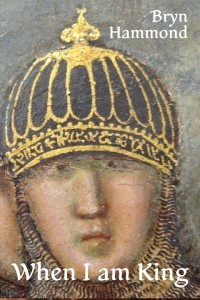

My new children

If I was in the dumps last post, I’m out. I have new children.

If I was in the dumps last post, I’m out. I have new children.

A couple of thoughts. I’ve decided I like indie covers, in that they are indie. Why try to eradicate the indieness and pretend we’re Industry? We’re getting away from industry, aren’t we? An indie chooses her or his own covers, with the care and intelligence the creator has. But who wants to look expensive and out of the Publicity Department?

I’m going to steam ahead and issue the two sections of Tribal Brawls, as I have done with The Old Ideal. For one thing, paperbacks are going to be unwieldy and costly, as they stand. I’ll do trade size paperbacks for The Old Ideal and Tribal Brawls, but as an alternative, medium-sized and medium-priced with the four that make up these. I think I was led to this because I want them covers. But it’s easy to do and why on earth not? These new books, by titles, blurbs and covers, I think express us. The next title, for instance, started facetiously but stuck. It might be oddball (as my Tchingis worries he is). Ah, the indie freedom to be oddball.

Publication date, for both on Smashwords, happens to be the 9th of the 9th. Nine is a lucky number for Mongols.