Bryn Hammond's Blog, page 14

March 1, 2012

To the Left of Chinggis Khan

[image error][image error]A where-to-read about Chinggis as social revolutionary (I'll spell him Chinggis, the convention, when I mean the historical figure and not the guy in my novel).

One of the more gettable-at books is Thomas J. Barfield, A Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221BC to AD 1757. He has a chapter on 'Mongol Political Organization' where he discusses Chinggis' move away from political dependence on kinship and clans. Chinggis had his reasons to distrust his kin, which, Barfield argues, was what led him to abandon tribal government, reject the aristocracy of the clans and switch to a talent system. Mongolian political organization was not, therefore, the culmination of a long evolving steppe tradition, but a deviation from it.

Barfield is one opinion. You find another strongly-put case in Isenbike Togan, Flexibility and Limitation in Steppe Formations: The Kerait Khanate and Chinggis Khan. This is not an easy read. But if Chinggis the radical is your interest, it's possible to consult the section on him as a stand-alone: 'The New Universal Order'. Togan sees the beginning of an 'anti-tribal movement' before Chinggis, a voluntary, popular movement that Chinggis came to lead and made into a central policy.

He started with his nokers, his companions: With his reputation of righteousness and fairness he was able to build a following… The noker functioned on the principles of equality among participants… this basic relationship of loyalty and equality was transferred… into the ranks of the army of conquest... Groups joined him – not tribal groups but people who had split from their tribes. We get a sense of the excitement of the small groups who joined Temujin… These people who had used their right of volition to join him were now becoming part of a new organization.

Togan talks about 'detribalization' – riddance to the old order. Chinggis directed his anti-tribe measures not against tribes in general but those whose leadership had become 'dynastic'. The main objective of these policies was to create a society in which individuals, irrespective of their tribal, ethnic or religious background, could participate around common goals. She goes on to discuss his separation of wealth and power – his cutting of the ties between those two things – and his institutionalized redistribution… to the soldiers, to the common man.[image error]

Togan also maintains that Chinggis – in his jasagh, his ordinances – severed religion and power. The Chinggisid period stands out with its tendencies that we are inclined to call 'secular'. In the separation of the divine from wealth and power Chinggis Khan was successful… No-one was more divine than another; no-one was better, no-one was closer to the sacred ancestors… This aspect of the Jasagh remained uncontested until the sixteenth-seventeenth century when again divinity emerged in the cloak of saintliness (sayyid, qutughtu)… that is, Islamic and Buddhist saints.

There you have Isenbike Togan and her bold strokes on behalf of twelfth and thirteenth century ideology: a belief in and a conscious fight for universalism.

There are bits and pieces online that you can read. Here's a few links to articles on Chinggis and politics:

There are bits and pieces online that you can read. Here's a few links to articles on Chinggis and politics:

'Something New Under the Sun: The Mongol Empire's Innovations in Steppe Political Organization and Military Strategy' by Thomas J. Barfield (him of the first book I mentioned – an abstract of his argument)

'The Legacy of Chinggis Khan in Law and Politics' by Prof. Robert D. McChesney – on 'what we might call the constitutional system introduced by the Mongols' (his jasagh or yasa)

As a curiosity, 'Chengiz Khan and Nehru' by Jack Weatherford – Jawaharlal Nehru, in prison for his work towards Indian independence, muses on the Mongols' struggle

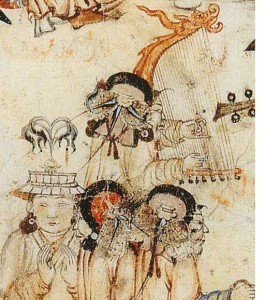

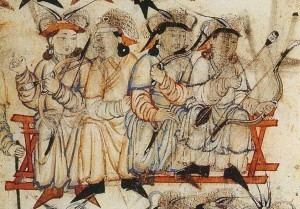

And the hats, I hear you ask? These are details from a Mongol court scene, celebrations of an enthronement: an illustration to Rashid a-Din's world history, written in Persian under Mongol patronage.

February 25, 2012

The Kyrgyz epic Manas, online

It ain't easy to find your steppe epic in English. So I alert you to a project to translate the epic Manas online. Here's the link: The Kyrgyz Epic Manas, selections translated, introduced and annotated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil.

It ain't easy to find your steppe epic in English. So I alert you to a project to translate the epic Manas online. Here's the link: The Kyrgyz Epic Manas, selections translated, introduced and annotated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil.

It's the epic of a people – a little like the Shahnameh used to be, perhaps; it's THE epic, people didn't bother to make up others, they just added to Manas. In fact the Kyrgyz don't have epic singers, they have manaschi: singers of Manas. They celebrated the poem's 1000th anniversary a few years ago. Wiki contests that age, but Wiki can argue with the 'new independent government of Kyrgyzstan' and cultural pride. The version from which you find great swathes here is half a million lines: take the Iliad and the Odyssey together and times by twenty… or since the lines are short, yes Wiki, let's say by ten. It's oral epic, written down and saved in sixty versions from the last of the oral poets alive, who in the tradition of their art have each an original rendition. The art is alive in Kyrgyzstan, just not exclusively oral. That changes things.

Horse-head fiddles

W. Barthold, of the wonderful book Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion, called it an absurd gallimaufry of pseudo-history. That's the sound of a frustrated historian; fast and loose is the least of Turk epic's attitude to history, quite as bad as Homer and the Trojan War. Nora Chadwick, my fave person on steppe epic, thinks this the peak of the art: The Kirghiz were said to specialize in epic poetry almost to the exclusion of saga and lyric, and to pay especial regard to finished and polished diction… An individual feature of the poetry of the Kirghiz, and one which shows the advanced character of the tradition, is its tendency to fall into cycles. She means, Manas is a cycle rather than a single poem, with shifts to different central figures. Thus the neverending story.

Go explore.

February 16, 2012

Guest spot: A.J. Campbell’s gallery of steppe women

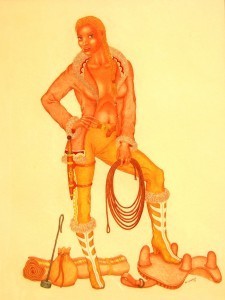

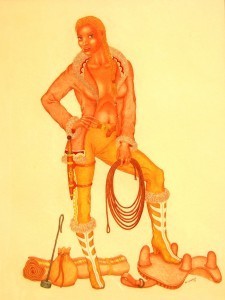

The Horsebreaker

I’m proud to have A.J. Campbell on the blog. And gobsmacked by his steppe women. He’s the author of The Demon’s Door Bolt, and another novel to be out shortly, both of which are very strong on fighting women. I discover he’s also an artist. Here he is:

Thems what was real womenses, arr!

Steppe women have always intrigued me. Oft enough, they rose to greatness, as seen in the great number of female warrior burials. Some were buried in kurgans not reserved for just kings; and at least one woman – the so-called Golden Man of Issyk – achieved a status beyond the greatest of steppe chieftains. So, there really was a historical Xena.

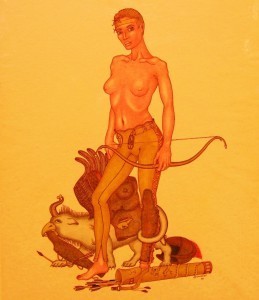

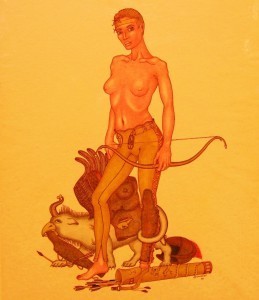

Penthesilea's Little Helper

Brunhild and Hedgehog

I’m not a prolific painter, especially when writing novels… which is most of the time, lately. But somehow, I’ve managed to dry-paint a few women warriors. My art tends to reflect my humour, which might not entertain everyone. Each painting is on vellum, similar to the art of the late Alberto Vargas. In essence they are ‘cartoons’ reflecting the nearly-dead pin-up genre of the 1930s and 40s.

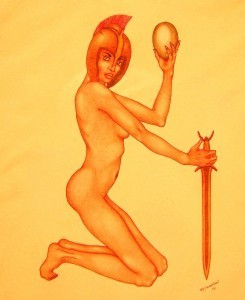

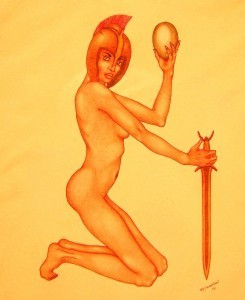

Rokhshan with a Gryphon Egg

Behind each semi-realistic work, there’s an underlying truth. They are women who can hold their own against any man. More important, they are heroic, not passive reclining nudes. My favourites are The Horsebreaker, a brazen Alan woman replete with lasso, horned saddle, tamga iron and Sogdian blanket (a painting so outrageously priced that no-one will ever buy it) and Penthesilea’s Little Helper (with its baby gryphon).

Bryn back

Thanks, A.J. Another favourite of mine is Brunhild in spiky armour with a hedgehog, and she’s here although she isn’t steppe (so these are the spangens?) Rokhshan was Alexander’s wife, and A.J. had to tell me there’s a joke in there, because I wouldn’t recognise a football or a Corinthian football helmet.

I notice I’ve got him talking Xena. A.J.’s met the age of 70 (I hope he doesn’t mind me dropping that) and gave up the idiot box before Xena leapt into our lives; I’ve been telling him he missed a pop culture fighting-woman icon, if nothing else.

You can find these and others for sale on his End of Days Press website – along with a fantastic little shop for re-created arms and armour, horse bows and swords, steppe helmets, the akinakes as featured in The Demon’s Door Bolt, and even your steppe accessories. A.J. Campbell is an archery instructor and a living-history reenactor, and him and his make the weaponry.

Guest spot: A.J. Campbell's gallery of steppe women

The Horsebreaker

I'm proud to have A.J. Campbell on the blog. And gobsmacked by his steppe women. He's the author of The Demon's Door Bolt, and another novel to be out shortly, both of which are very strong on fighting women. I discover he's also an artist. Here he is:

Thems what was real womenses, arr!

Steppe women have always intrigued me. Oft enough, they rose to greatness, as seen in the great number of female warrior burials. Some were buried in kurgans not reserved for just kings; and at least one woman – the so-called Golden Man of Issyk – achieved a status beyond the greatest of steppe chieftains. So, there really was a historical Xena.

Penthesilea's Little Helper

Brunhild and Hedgehog

I'm not a prolific painter, especially when writing novels… which is most of the time, lately. But somehow, I've managed to dry-paint a few women warriors. My art tends to reflect my humour, which might not entertain everyone. Each painting is on vellum, similar to the art of the late Alberto Vargas. In essence they are 'cartoons' reflecting the nearly-dead pin-up genre of the 1930s and 40s.

Rokhshan with a Gryphon Egg

Behind each semi-realistic work, there's an underlying truth. They are women who can hold their own against any man. More important, they are heroic, not passive reclining nudes. My favourites are The Horsebreaker, a brazen Alan woman replete with lasso, horned saddle, tamga iron and Sogdian blanket (a painting so outrageously priced that no-one will ever buy it) and Penthesilea's Little Helper (with its baby gryphon).

Bryn back

Thanks, A.J. Another favourite of mine is Brunhild in spiky armour with a hedgehog, and she's here although she isn't steppe (so these are the spangens?) Rokhshan was Alexander's wife, and A.J. had to tell me there's a joke in there, because I wouldn't recognise a football or a Corinthian football helmet.

I notice I've got him talking Xena. A.J.'s met the age of 70 (I hope he doesn't mind me dropping that) and gave up the idiot box before Xena leapt into our lives; I've been telling him he missed a pop culture fighting-woman icon, if nothing else.

You can find these and others for sale on his End of Days Press website – along with a fantastic little shop for re-created arms and armour, horse bows and swords, steppe helmets, the akinakes as featured in The Demon's Door Bolt, and even your steppe accessories. A.J. Campbell is an archery instructor and a living-history reenactor, and him and his make the weaponry.

February 11, 2012

Women, Barbarians and the Dread Interpretation

I think the person in the street knows by now, women were better off in barbarian societies. That's a blanket statement I can conscientiously make. I have even thought, on my travels in the past, we aren't the most feminist society that has ever been. I'm hesitant there, but I'd say, don't make that assumption. If I were a woman in the Middle Ages, I'd want to be either Norse or from the steppe. So I have a laugh when I see macho projections onto Vikings or steppe hordes (that isn't true: I don't have a laugh, I have a cry).

It's risky to let scholars intervene between you and the source material. They can skew your perceptions. In the Nibelungenlied (German, circa 1200), Brunhild warns her suitors: "He will have to cast the weight, follow through with a leap, and then throw the javelin with me. Do not be too hasty – you may well lose your lives and your reputations here," said the charming woman. "Consider it very closely." And Hatto footnotes, There is always a touch of burlesque when Brunhild goes into action. I like you, A.T. Hatto; you translated a steppe epic, bless you; but why is this burlesque? Brunhild's a riot, I grant you, but the butt of the burlesque is Gunther. The Nibelungenlied can be (mis)taken for misogynist. Its society, yes, which hides a girl away; but distinguish from that the author's stance. Are we happy when Brunhild is robbed of her vast strength and Gunther manages to sleep with his wife? He can scarcely deserve her less. On his second attempt at a wedding night Hatto apologises for the poet, who as a child of his age, is shocked by her refusal to consummate the marriage. Is he? He's thrown in a conservative sentence – at face value – but that has been a strategy of poets since. Does the story support a husband's right? Doesn't the story ask questions?

While we're on this folklore motif – the girl who challenges her suitors to trials of strength – let's visit Qaidu's daughter Qutulun, over in Turkestan and eighty years after the Nibelungenlied was written: she put the folktale into practice. I love it when people decide to live out fiction. She had the wherewithal, and beat her suitors at wrestling. She didn't have them killed, but only took a forfeit of horses.

Four centuries later – we're in the 1650s now – a Dutch embassy to China, shortly after the Qing conquest, leaves us sketches of your typical northern woman, in contrast to Han Chinese. The women from the north strode around on big feet, with unpainted faces, while the Chinese were caked in make-up and didn't walk anywhere on their lotus-feet. The Europeans seem amused and oddly charmed to meet these Tartar ladies – forward, free and easy, very hospitable – although the ambassador's eyes might have spun when she unbuttoned him. Here are two encounters:

The Governor was by birth a Tartar, but understood not the Chinese language, therefore his sons were Interpreters. His Wife, a proper and comely Dame, spoke more than her husband, and was strangely inquisitive about Holland; she was not dismayed at our strange Arms, but like a bold Virago drew out our Swords, and discharged our Pistols, which much delighted her.

As we were riding out one day to take the air, we passed by the gate of the Old Imperial Court, where sat a great Tartar Lady, with her servants waiting upon her, about forty years of Age: She very civilly sent to our Interpreter to invite the Ambassadors into her House; Jacob de Keyzer hereupon alighted, and the Lady then made towards him: She was very debonair and free, looked upon our Swords, and much admired their bending without breaking: She took the Ambassador's Hat, and put it on her own Head, and unbutton'd his Doublet almost down to the Waist: Afterwards she led the way into the house and desired him to follow… in her Apartment we found her standing with her Daughter about half her age, waiting our coming, in great state…. They set before us some of their Sweet-meats, much entreating us to Eat, excusing the meanness of their Entertainment, her husband being absent.

Case study: were the women heads-of-state in Qara Khitai regents or khans? Once China had a woman emperor, and only one historian dares to call her that. Christopher I. Beckwith explains: The sources indicate she was called 'Emperor' (Chinese, ti) during her reign. Although she is better known by her posthumous name, Empress Wu Tse-t'ien, I prefer to follow her own intentions and also to give her credit for her accomplishments; thus I call her 'Emperor Wu'. It's a similar tale in Qara Khitai (or Western Liao; Central Asia, dates 1141-1218) where Michel Biran is the first to acknowledge the women khans for what they were: Two out of the five Gurkhans were women… According to the Liao shi [Chinese source], the Qara Khitai empresses were merely regents, who reigned only temporarily, until their male children or nephews reached majority. Both Qara Khitai empresses, however, were specifically nominated for the post by their predecessors… Muslim sources suggest that the empress held unlimited authority in her realm, as is also implied by her titles… In fact, it is clear that the empresses functioned as rulers in their own right. They had their own reign titles, a feature that no Liao (or Chinese) regent ever had; they bore the titles Gurkhan [Universal Khan] and Dashi; and they certainly determined the empire's internal and external policy.

On matters of sexual violence (a subject I have to research; my God, wish me luck or grant me strength), I was deeply struck, early in my education, by the sheer enlightenment found in The Wife of Bath's Tale, and yes, the kindness. Forget her Prologue, read her Tale. At eighteen or twenty I thought, this is so much more civilized than what I hear in the world today.

February 4, 2012

The Demon’s Door Bolt by A.J. Campbell

[image error]Left: more Mehmet Black Pencil (the guy who did my banner) – he liked to draw monster-demons, often in daily human affairs, sitting about chatting, whacking a donkey. What’s Mehmet telling us? I’ve heard they called him Black Pencil for his mordant sense of humour.

But onto the book: The Demon’s Door Bolt by A.J. Campbell. Here’s my comments at Goodreads. Science fiction on the fifth-century steppe, with humour.

[image error]It’s my idea of an indie book: straight out of the writer’s brain to you; cherished in his hands for years; written with commitment, since he tries to squeeze into a book his heart, his soul and what he’s learnt in life.

Right, that’s my definition of an indie. Toss those that don’t fit aside. While you’re at it, toss aside the output of career novelists. Find a writer.

I’m strident today. I get like that. Sorry. Back to subject.

It’s those unique books I am on the lookout for, above the herd of others. This one may not be your cup of black milk, folks; besides, it’s his comedy and I believe he has another up his sleeve. But I’m excited by it, as you’ll see if you follow that link.

The Demon's Door Bolt by A.J. Campbell

[image error]Left: more Mehmet Black Pencil (the guy who did my banner) – he liked to draw monster-demons, often in daily human affairs, sitting about chatting, whacking a donkey. What's Mehmet telling us? I've heard they called him Black Pencil for his mordant sense of humour.

But onto the book: The Demon's Door Bolt by A.J. Campbell. Here's my comments at Goodreads. Science fiction on the fifth-century steppe, with humour.

[image error]It's my idea of an indie book: straight out of the writer's brain to you; cherished in his hands for years; written with commitment, since he tries to squeeze into a book his heart, his soul and what he's learnt in life.

Right, that's my definition of an indie. Toss those that don't fit aside. While you're at it, toss aside the output of career novelists. Find a writer.

I'm strident today. I get like that. Sorry. Back to subject.

It's those unique books I am on the lookout for, above the herd of others. This one may not be your cup of black milk, folks; besides, it's his comedy and I believe he has another up his sleeve. But I'm excited by it, as you'll see if you follow that link.

January 29, 2012

On ebook errors. A flippant post.

I seem to have high, high threshold for those unvetted ebooks that come equipped with grammatical gymnastics, slips of the finger, and creative spellings. Notice how fond that sentence was?

It's an issue that puts a lot of people off the indie publishing lark. A great excuse has leapt to mind, about my toleration factor. From an early age I have stumbled through medieval literature, unmodernised. I loathe modernisations. (If you want to know why, just read the first four lines of Canterbury Tales in Penguin's modern English translation, and then read them in Penguin's original-spelling edition. See?) I had the commonsense – which I must have learnt, possibly from T.H. White, or T.E. Lawrence? – to loathe modernisations from the start, so I pitted my teen brain against original-spelling Malory and onwards into the wonders of medieval romance.

As for genuine Malory, may I pose the question: do you like your knights garnysshed for battle, or… come to that, I've only eyed moderns to scorn them and don't have one in the house. What do they do? Garnish Sir Lancelot for joust? I bet he prepares, doesn't he, or arms himself: and how much is lost?

Or I'll give you the serious argument, although this is a tangent. Yes, the original is odd to our eyes. But that is a constant little memento to you: throw yourself back, do not make your modern assumptions, question them – at every sentence, watch for the 15thC ideas of the world, and don't judge by your own. Else you read the book half-blind. The 'simplest' change – removal of the garnysshynges – starts to remove the evidence, in this case, on their idea of battle, that's different than ours, in subtle ways you need the words to study. If you want to know how a knight felt in his battle preparations, Malory can tell you, but a moderniser won't.

Where was I? Ebooks. After these encounters with spelling and grammar different from our own, and yet English, can I mind an ebook? The grammar and spelling taught to us goes for here and now, but English has been a Beast Glatisant with head of pard and feet of hart, and Chaucer, he'd be kicked out of grammar class today. It's English, he might protest on his way out. If I can understand it – this is the bottom line – it's English, and even to have strictures on how to spell a word is latter-day in the wonderful life of English. Is this why I don't care?

It is a great excuse.

January 19, 2012

Talking Horses

"Throughout Turkic literature, human and superhuman faculties are attributed to horses. Not only are these generally gifted with human speech and reason, but they are superior morally and intellectually to the heroes themselves." – Chadwick's Oral Epics of Central Asia.

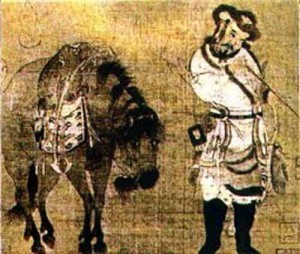

In steppe art, too, the horses talk. Take this bloke:  [image error]He's being galloped into the fray – a sad affray of Mongols against Mongols. And the people are lusty about it, but the horse is going, yes, this seems like a bloody great idea.

[image error]He's being galloped into the fray – a sad affray of Mongols against Mongols. And the people are lusty about it, but the horse is going, yes, this seems like a bloody great idea.

His eyes are set at the front of his head. Unanatomical, and done for effect: that's so he can make eye-contact with us, and comment on the scene. This horse is definitely smarter than the humans.

Portrait with Horse is one of the commonest subjects in steppe art, and often the horse has more expression than its person. Which happens in the Secret History: Horses always have their features documented when they trot into the story, unlike the people on them; we're told that Tchingis got his fatal injury in a fall from a red-earth roan, but for Tchingis' own looks we have to consult Chinese travel journals and Persian war reports.

Here's a Jurchen hunter (he's squinting at his arrow) and a sheepish sort of horse, with his eyes on us again.

Here's a Jurchen hunter (he's squinting at his arrow) and a sheepish sort of horse, with his eyes on us again.

I guess your average nomad saw more horse faces than human, daily, outside the family ger.

I thought I was being clever in the quarrel between Temujin and Jamuqa, late in book one: Jamuqa's mare catches his mood and starts to give his body language for him, as Jamuqa becomes too deeply agitated to tell us how he's feeling – even in pov – he can't think about himself and only notices the antics of his mare. But no, I'm a rank amateur in use-of-a-horse. I'll have to do much more with my horses in book three.

January 14, 2012

Q&A

[image error]Here I want questions. I'm keen to answer questions.

Or just to talk to the likeminded.

Interactivity is the value of the site to me. You can start discussions with an answer to this entry.