[image error][image error]A where-to-read about Chinggis as social revolutionary (I'll spell him Chinggis, the convention, when I mean the historical figure and not the guy in my novel).

One of the more gettable-at books is Thomas J. Barfield, A Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221BC to AD 1757. He has a chapter on 'Mongol Political Organization' where he discusses Chinggis' move away from political dependence on kinship and clans. Chinggis had his reasons to distrust his kin, which, Barfield argues, was what led him to abandon tribal government, reject the aristocracy of the clans and switch to a talent system. Mongolian political organization was not, therefore, the culmination of a long evolving steppe tradition, but a deviation from it.

Barfield is one opinion. You find another strongly-put case in Isenbike Togan, Flexibility and Limitation in Steppe Formations: The Kerait Khanate and Chinggis Khan. This is not an easy read. But if Chinggis the radical is your interest, it's possible to consult the section on him as a stand-alone: 'The New Universal Order'. Togan sees the beginning of an 'anti-tribal movement' before Chinggis, a voluntary, popular movement that Chinggis came to lead and made into a central policy.

[image error]

He started with his nokers, his companions: With his reputation of righteousness and fairness he was able to build a following… The noker functioned on the principles of equality among participants… this basic relationship of loyalty and equality was transferred… into the ranks of the army of conquest... Groups joined him – not tribal groups but people who had split from their tribes. We get a sense of the excitement of the small groups who joined Temujin… These people who had used their right of volition to join him were now becoming part of a new organization.

Togan talks about 'detribalization' – riddance to the old order. Chinggis directed his anti-tribe measures not against tribes in general but those whose leadership had become 'dynastic'. The main objective of these policies was to create a society in which individuals, irrespective of their tribal, ethnic or religious background, could participate around common goals. She goes on to discuss his separation of wealth and power – his cutting of the ties between those two things – and his institutionalized redistribution… to the soldiers, to the common man.[image error]

Togan also maintains that Chinggis – in his jasagh, his ordinances – severed religion and power. The Chinggisid period stands out with its tendencies that we are inclined to call 'secular'. In the separation of the divine from wealth and power Chinggis Khan was successful… No-one was more divine than another; no-one was better, no-one was closer to the sacred ancestors… This aspect of the Jasagh remained uncontested until the sixteenth-seventeenth century when again divinity emerged in the cloak of saintliness (sayyid, qutughtu)… that is, Islamic and Buddhist saints.

There you have Isenbike Togan and her bold strokes on behalf of twelfth and thirteenth century ideology: a belief in and a conscious fight for universalism.

There are bits and pieces online that you can read. Here's a few links to articles on Chinggis and politics:

There are bits and pieces online that you can read. Here's a few links to articles on Chinggis and politics:

'Something New Under the Sun: The Mongol Empire's Innovations in Steppe Political Organization and Military Strategy' by Thomas J. Barfield (him of the first book I mentioned – an abstract of his argument)

'The Legacy of Chinggis Khan in Law and Politics' by Prof. Robert D. McChesney – on 'what we might call the constitutional system introduced by the Mongols' (his jasagh or yasa)

As a curiosity, 'Chengiz Khan and Nehru' by Jack Weatherford – Jawaharlal Nehru, in prison for his work towards Indian independence, muses on the Mongols' struggle

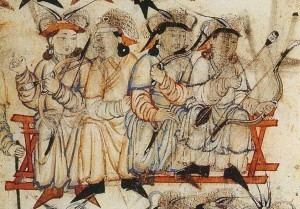

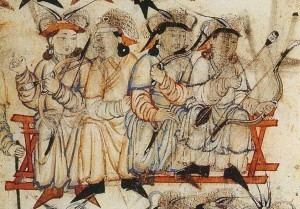

And the hats, I hear you ask? These are details from a Mongol court scene, celebrations of an enthronement: an illustration to Rashid a-Din's world history, written in Persian under Mongol patronage.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Bryn, I admire your scholarship in these matters. I truthfully have to say I've never devoted my study to a specific time and place as you have so admirably done. Please let me tell you how much I enjoyed your remark: "Chinggis had his reasons to distrust his kin, which, Barfield argues, was what led him to abandon tribal government, reject the aristocracy of the clans and switch to a talent system." Which forces us to rethink the person now known as "Genghis Khan." He was ahead of his time (his contemporaries couldn't understand him), and his tragedy was that all he had to impose his will was brilliantly imagined force.

Bryn, I admire your scholarship in these matters. I truthfully have to say I've never devoted my study to a specific time and place as you have so admirably done. Please let me tell you how much I enjoyed your remark: "Chinggis had his reasons to distrust his kin, which, Barfield argues, was what led him to abandon tribal government, reject the aristocracy of the clans and switch to a talent system." Which forces us to rethink the person now known as "Genghis Khan." He was ahead of his time (his contemporaries couldn't understand him), and his tragedy was that all he had to impose his will was brilliantly imagined force.

Hello, Ron. I've never gotten this obsessed before in my life, but it's gorgeous to be in that state: where the more you read, the more drawn in you are. It's funny how my interest stops dead at his date of death - when he can't be aware of events, they matter to me about as much as... 13thC politics matters to the next person. Until then everything matters, that he might hear about or think about.

Hello, Ron. I've never gotten this obsessed before in my life, but it's gorgeous to be in that state: where the more you read, the more drawn in you are. It's funny how my interest stops dead at his date of death - when he can't be aware of events, they matter to me about as much as... 13thC politics matters to the next person. Until then everything matters, that he might hear about or think about.