Bryn Hammond's Blog, page 13

September 6, 2012

New strategy

The day before yesterday I was near to despair – consoled only by the knowledge I’m not alone. Over there’s Robert Polevoi with a magnificent novel in the doldrums. “Ask me in a year” has been my answer to the question, how’s your book going? A writer needs among her or his equipment the faith of a Christian in the arena, and that I have. But it isn’t humanly doable to keep our chins up, and mine was sagging.

Yesterday I heard for the hundredth time the tale of an indie who’d sold one a month, until she set the first in her series to free and caught attention. I have two 600-700 page books – depends on how you count. The first agent I submitted to told me publishers won’t look at a book that size from a new author. I knew I’d have to offer the first in halves. Very fortunately, the first is in two titled sections and splits neatly 50-50, and works as either one book or as two. When I went indie I returned to one book, because those two halves do make a whole. And God knows I’m not out to exploit the buyer by charging for two books when artistic judgement tells me they’re one (I’ve heard this beef from them as purchase books. Me ethical author and writer of integrity).

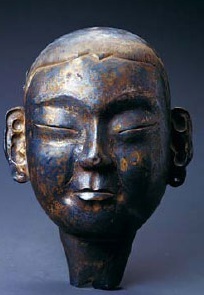

With this first-in-a-series-free thing I’ve thought, that’s fine, for those who write a book a year, but mine take five, even with drastic reduction of other activities, such as paid work and relationships (yes, we’re committed). But I’ve always had a 50% sample on Smashwords, where the choice is mine. So – in addition to Amgalant One and Two as they stand – I’m going to issue those two sections and set the first to free. It’s a way of getting that much sample into other shops. Of Battles Past permanently free; then they can either buy When I am King – the 2nd half – or the original book One, with both these.

Is that messy? It’s flexible. Think flexible, think e. It’s what you can do with ebooks, and indie. Anyhow, it’s a chance to save us from the doldrums. Mark Coker has drummed into me, ‘leverage free’.

Since yesterday – interrupted only by a visit to work – I’ve drafted a cover and a blurb for the free. The cover’s above, here’s the blurb. Both, I hope, and suspect, are bold, and if we’re provocative, that’s no bad strategy either.

China has executed Ambaghai, the Mongols’ khan, on a hurdle with donkey ears and tail from the theatre, in mockery of the horse peoples of the steppe. It cries for hachi.

‘Hachi means that which is owed, or felt due. It can mean an act of humanity. It can mean vengeance. It meant justice.’

The Mongols go to war for Ambaghai’s hachi, in a century when no steppe people is fit to tackle China. They believe battles are won by the just, and the size differential doesn’t bother them. They are wrong, but the Mongol God comforts them with an omen. Temujin, the baby of that battle day, has in his hand his people’s future victory.

The Chinese have crossbows, but the Mongols have belief.

August 30, 2012

On Change

A hymn to Change, god of novels: and nowhere more so than when you write about the Mongols.

A hymn to Change, god of novels: and nowhere more so than when you write about the Mongols.

“A big step, in sixty years, from hard times on the Onon Gol to triumphs on the Danube: Liegnitz, Wiener Neustadt might have been the moon to Yesugei’s nokod, the moon Dei Sechen dreamt of.” – I think I connected steps and the moon in echo of Neil Armstrong. And why not? The Mongols didn’t fly to the moon but they did near enough, in the age. This sentence intrudes when things are at their worst (Yesugei’s dead) – the sudden look ahead, a technique from the Secret History. Here we have Temujin’s family in their lowest circumstances:

Hoelun Ujin, with her native courage,

Tightened down the high hat on her head,

Tied up her skirts in her sash.

Up and down the Onon Gol she ran

Picking sour pear and cedar cones,

Day and night scoured for nourishment for her sons.

Mother Hoelun, with her innate gall,

Took up sharpened sticks of juniper,

Dug the ground for roots and tubers,

Nourished her sons on mountain leek and onion,

On lily bulbs, white rush bottoms, silverweed.

She fed the clutch of upturned gullets in her nest,

Her hungry young, who grew to be kings and legislators.

That’s a sudden zoom – that gives you vertigo. Now, I believe in the artistry of the Secret History. It’s art, right? I don’t think it does this to claim the inevitability of Temujin’s rise to world fame. No, crap. It does this with the opposite intention: so you scratch your head and go, ‘Eh? From here to there? Crazy.’

Because it is crazy. Let’s get that straight: history is crazy, none more than Mongol history. There’s no inevitability about it. Juvaini, 13th-century Persian historian, muses on these questions:

“How contingent are human affairs, often how inexplicable. In the face of fate and fortune our exertions go for nought. Powers overthrown in their strength, their affluence, their high civilization, while we search for the logic in vain. Such an instance (was there ever such an instance?) are the Mongol people, when one casts an eye to their circumstances before they began to beat the drum of Tchingis Khan, when one sees with what extravagance fortune has sped them: on the head of the slave a crown to his glory, on the foot of the prince a fetter to his shame. And that was easy unto God.”

Easy unto God, but baffles the historian. As he says, the Mongols’ climb is unexampled. The only analogue I have found is the Arab conquests. Nobody expected, conceived of, imagined what happened in Mongol history. It was unimaginable. So, firstly, the novelist (historians too) must keep in mind that her people can have no conception of what’s ahead.

Obvious, but tricky to do – to honestly forget your hindsight on their behalf. And there are traps in the next one: she mustn’t attribute to them things out of the future. This is often transgressed – by historians, yes. Most of our data is from the Empire Period. For lack of material, historians have been known to assume the data goes for Mongols before they left the steppe. This underestimates the change factor. And the change factor – my creed is – cannot possibly be overestimated. What people’s circumstances changed so much in sixty years? And the changes to them? In thought, practices, behaviour? Nothing can be transported straight from later times to earlier. No assumptions, except for the assumption that changes were massive, or that for anything to be unchanged is near-impossible.

Of course Chinggis didn’t set out to conquer the world – unless you believe the heavens told him what’s ahead. The first intimations that success led the Mongols on to think in terms of world-conquest, date from late in his career or after his death. And no wonder, with success like that. The bizarreness of history has to be kept, conserved, by novelist or historian. Mongol history was never inevitable. It’s bizarre.

Would the Empire Period Mongols have recognised themselves from the obscure days on the steppe? Maybe, but not the other way around. Not the other way around.

“Eljigidei who forty years on, in the strange new world Tchingis left them, was agent for negotiations with Saint Louis of France and the Pope towards a scheme for Mongols and Crusaders to concert and win the Kingdom of Jerusalem.”

I pop this in, when Tchingis is in his lowest circumstances – for the bizarreness, as I believe the Secret History teaches me: startle them with a glance ahead. I don’t argue with my original’s artistic effects, I shut up and copy. But Eljigidei, down-and-out with Tchingis at Baljuna Lake, would only reel to see his future self. Recognise him? No way. No more than the Pope.

It might have happened differently. Change goes along with uncertainty: there’s the change principle, there’s the uncertainty principle: two yak’s tails to hang on your standard, whether you want to write fiction or fact. Put in the accidental. Put in the trivia that swung history, the unfair illogical stupid little thing that swung a battle. The accident factor, there’s a third yak tail, to end on a holy number: I’ll have to think up nine, for my writer’s tuq.

June 23, 2012

‘They eat people in the city’: three anecdotes

The things you learn in research.

The things you learn in research.

1st story: Huang Chao, or the Mad Bandit (fairly factual nickname) captured Tang China’s capital with his huge army of the disaffected. He was a part and partisan of the anti-foreign swing in late Tang and had massacred 120,000 people in China’s most mercantile city with Indian, Arab and Persian residents. In the capital he was cut off with nothing to feed his army – except the inhabitants. For two years rations were human. In 883 Huang’s army killed more than a thousand people every day for food. – Dieter Kuhn, The Age of Confucian Rule, where he goes on to quote a 14th century diarist: in the past and present rebellious soldiers have eaten human flesh. They called it ‘flesh of thought’ or ‘two-legged mutton’. Kuhn makes no bones about this habit: On many occasions when rebels ran out of food, they captured people and ate them; sometimes they salted or pickled the corpses to preserve them for later consumption. In years of famine, humans were slaughtered like livestock, chopped to pieces, and cooked for food. Human flesh was often more plentiful and cheaper than dog meat.

The bandit was mad, but what about the loyal general? He pre-dates the bandit, too, by a century; he operated in the great An Lushan revolt. Zhang had been so determined not to be starved out by rebels that he and his troops are said to have killed and eaten the entire noncombatant population of their besieged city, apparently amounting to twenty or thirty thousand people by the time the city fell. Zhang Xun had encouraged his troops to the necessity of this by first killing and eating his own concubine. In the aftermath of the revolt, the Tang government debated on whether to include him in its honours list of loyalists. Some Tang memorialists now questioned whether Zhang Xun’s behavior had not been excessive and suggested that surrender might have preserved more life. The emperor settled this question with an edict saying unequivocally that Zhang’s actions were undoubtedly meritorious. – Naomi Standen, Unbounded Loyalty.

The bandit was mad, but what about the loyal general? He pre-dates the bandit, too, by a century; he operated in the great An Lushan revolt. Zhang had been so determined not to be starved out by rebels that he and his troops are said to have killed and eaten the entire noncombatant population of their besieged city, apparently amounting to twenty or thirty thousand people by the time the city fell. Zhang Xun had encouraged his troops to the necessity of this by first killing and eating his own concubine. In the aftermath of the revolt, the Tang government debated on whether to include him in its honours list of loyalists. Some Tang memorialists now questioned whether Zhang Xun’s behavior had not been excessive and suggested that surrender might have preserved more life. The emperor settled this question with an edict saying unequivocally that Zhang’s actions were undoubtedly meritorious. – Naomi Standen, Unbounded Loyalty.

The third anecdote I’ve already written into my novel, so Jamuqa can tell us. It’s true, of course (would I lie to you?) and found in Don J. Wyatt’s article ‘Unsung Men of War’ – on psychology around war in Song, known as the most civilian of Chinese eras. There was a story [Jamuqa] loved, about a Chinese. “As cultured as any Chinese, a famous prose stylist, who held the office, at one stage of his career, of Assistant Facilitator of Propriety. It’s the sort of office Chinese have. Served with distinction in the wars against a tribal mountain people stuck in the midst of China, perpetual rebels. Every day he’d send his agents far and wide to scout for executions, and whenever they found a fresh cadaver on a gallows, they filched the liver. This organ, raw, he’d have put before him with salt and vinegar, as his own first course in an otherwise perfectly conventional dinner. To the shock, horror and nausea of colleagues and acquaintances who dined at his house. Now, who does this, I ask you? The mountain tribes? Maybe. Maybe they had a nibble on a liver. But this character, he just had to out-barbarian the barbarians.”

The third anecdote I’ve already written into my novel, so Jamuqa can tell us. It’s true, of course (would I lie to you?) and found in Don J. Wyatt’s article ‘Unsung Men of War’ – on psychology around war in Song, known as the most civilian of Chinese eras. There was a story [Jamuqa] loved, about a Chinese. “As cultured as any Chinese, a famous prose stylist, who held the office, at one stage of his career, of Assistant Facilitator of Propriety. It’s the sort of office Chinese have. Served with distinction in the wars against a tribal mountain people stuck in the midst of China, perpetual rebels. Every day he’d send his agents far and wide to scout for executions, and whenever they found a fresh cadaver on a gallows, they filched the liver. This organ, raw, he’d have put before him with salt and vinegar, as his own first course in an otherwise perfectly conventional dinner. To the shock, horror and nausea of colleagues and acquaintances who dined at his house. Now, who does this, I ask you? The mountain tribes? Maybe. Maybe they had a nibble on a liver. But this character, he just had to out-barbarian the barbarians.”

I’ll use the other stories in my next. Imagine what nomads made of these tales, these urban legends with substance – nomads who begin with an image of the ‘wicked city’. Jack Weatherford has given me a lead in his terrific little book Savages and Civilization. He points out that the early Bible is a unique document in the old tribal-urban antagonism: The Bible offers the best example of the perspective on the city held by rural and nomadic tribes. Unlike most ancient chronicles, which relate their stories from the heart of urban civilization… the Bible records the perspective of distinctly nomadic herding people. The tribal people may have been conquered but were seldom awed by urban life, but when they did succumb to urban pleasures, divine retribution… followed quickly. I now read my Bible with this thought and see its city-hatred. From Egypt to Babylon, the books of the Old Testament present a catalog of urban sins for which God is constantly sending angels, armies, famines, or plagues to punish one city after another... God destroys them and often the entire city with them, or else he gives it to a more virtuous people, who are usually nomadic tribes.

The customs depicted in the Sodom and Gomorrah story, let’s face it, are unlikely: a sexual toll on travellers, you can’t stay overnight unless you offer entertainment. But as a garbled, ignorant nomad’s legend – think of a nomad who hasn’t set foot in a city and is here warned not to – with lurid sex and offence against the nomad’s first principle, guest rights – Sodom and Gomorrah suddenly make sense.

-Dieter Kuhn, The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009

-Naomi Standen, Unbounded Loyalty: Frontier Crossings in Liao China, University of Hawai’i Press, 2007

-Don J. Wyatt, ‘Unsung Men of War: Acculturated Embodiments of the Martial Ethos in the Song Dynasty’ in Military Culture in Imperial China, editor Nicola Di Cosmo, Harvard University Press, 2009

-Jack Weatherford, Savages and Civilization: Who Will Survive? Ballantine Books, 1994

Pictures by Mehmet Black Pencil

June 18, 2012

from the Great Mongol Shahnama – 1

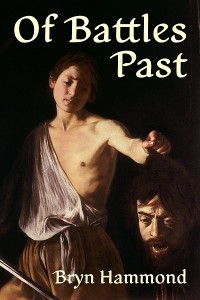

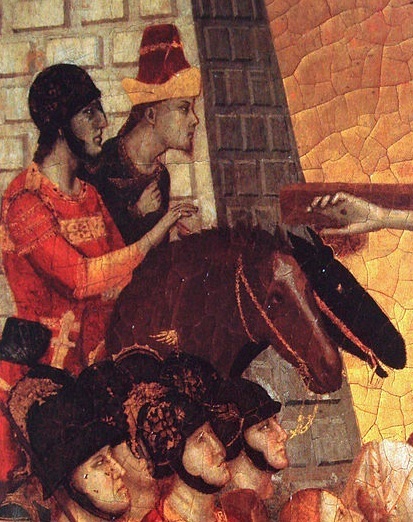

Bahram Gur Fighting a Wolf, from a page of the Great Mongol Shahnama (Book of Kings), Iran, 1330s. Ink, paint and gold on paper.

Bahram Gur Fighting a Wolf, from a page of the Great Mongol Shahnama (Book of Kings), Iran, 1330s. Ink, paint and gold on paper.

In Mongol Iran, book art exploded, and became the major art: patronage changed and this was the call, answered with a “redeployment of artistic energies”.

The Great Mongol Shahnama is an unfinished royal copy of the Persian epic. Big in scale, with a work space of 16×12 inches on the page, and 200 paintings intended, of which 57 survive. Nothing this ambitious had been tried. “Since Shahnama iconography was… in its infancy, the painters had no models for scores of the projected images… The… pressure to be innovative propelled the painters into unfamiliar territory in search of fresh inspiration.”

More to come on this spectacular book, and others, and how under the Mongols Chinese art met Persian. But here’s a sample: innovative? I believe him – those trees, that horse. Click to enlarge.

Quotes from ‘The Arts of the Book in Ilkhanid Iran’ by Robert Hillenbrand in The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, editors Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2002.

from the Great Mongol Shahnama

Bahram Gur Fighting a Wolf, from a page of the Great Mongol Shahnama (Book of Kings), Iran, 1330s. Ink, paint and gold on paper.

Bahram Gur Fighting a Wolf, from a page of the Great Mongol Shahnama (Book of Kings), Iran, 1330s. Ink, paint and gold on paper.

In Mongol Iran, book art exploded, and became the major art: patronage changed and this was the call, answered with a “redeployment of artistic energies”.

The Great Mongol Shahnama is an unfinished royal copy of the Persian epic. Big in scale, with a work space of 16×12 inches on the page, and 200 paintings intended, of which 57 survive. Nothing this ambitious had been tried. “Since Shahnama iconography was… in its infancy, the painters had no models for scores of the projected images… The… pressure to be innovative propelled the painters into unfamiliar territory in search of fresh inspiration.”

More to come on this spectacular book, and others, and how under the Mongols Chinese art met Persian. But here’s a sample: innovative? I believe him – those trees, that horse. Click to enlarge.

Quotes from ‘The Arts of the Book in Ilkhanid Iran’ by Robert Hillenbrand in The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, editors Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2002.

June 10, 2012

Grousset’s tragic Jenghiz Khan

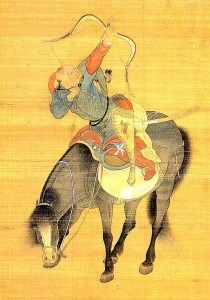

Giotto: a Mongol in a crucifixion scene, circa 1299

A homage to Rene Grousset, whose conception of Jenghiz Khan (as he spells him) was the first element of mine. It’s his Jenghiz I decided to write about. I remember that week I read the Jenghiz section of his Empire of the Steppes: halfway through his life I thought ‘I have my story, I have my hero’; from then on I was biting my fingernails, scared that in later years he’d alienate me – explicitly, I feared he’d be corrupted by power. When he was safely dead and had not lost my sympathies, I mopped my brow.

You see, I never got along with books, fiction or non-fiction, that are out of sympathy with their subject. Don’t misunderstand: give me a faulty hero. But without an essential sympathy, a writer has no hope to penetrate the subject. Ever and again I have found such books – hostile to what they write about – not only ungenerous and obtuse, but plain wrong. That’s why I’d have had to ditch Jenghiz as a subject had he done things I despised him for. The worst danger, as I say, I saw as abuses of power – the old story, turn on your own, murder old friends. When Jenghiz did not do these things, I admired him the more since I felt that to be rare. Uncorrupted by power; and add, uncorrupted by wealth. If I tell you unabashed he is my hero, these two boasts have much to do with it.

A tragic hero. I’m a tragedy addict; tragedy’s a dead art – George Steiner tells me so – to which I don’t aspire. But the tragic note in Grousset’s Jenghiz had to be there, or I’d have been bored with the story. And no other biographer has struck the tragic note. To me this is a failure: a failure of human sight, of imagination, and simply of nerve. Yes, I think Grousset is brave to face the contradictions, to grasp the nettle of paradox – take on the intellectual challenge. It’s easy to make him evil. The trouble is he wasn’t. He has nothing in common with Hitler and almost as little with Tamerlane.

Rene Grousset was meant to be a novelist; to this fact I attribute his human understanding. On Jenghiz he’s at his most lyrical, and when I quote him you might laugh. Although if you want him at his novelistic best, he also did a popular life, Conqueror of the World, which has such evocative chapter titles as ‘Misery and Grandeur of the Nomads’, ‘The Tears of Chingis-khan’, ‘The Dogs of Chingis-khan eat Human Flesh’, ‘A Note of High Tragedy: Chingis-khan and Jamuqa’. I wish he’d just written us a novel.

Rene Grousset was meant to be a novelist; to this fact I attribute his human understanding. On Jenghiz he’s at his most lyrical, and when I quote him you might laugh. Although if you want him at his novelistic best, he also did a popular life, Conqueror of the World, which has such evocative chapter titles as ‘Misery and Grandeur of the Nomads’, ‘The Tears of Chingis-khan’, ‘The Dogs of Chingis-khan eat Human Flesh’, ‘A Note of High Tragedy: Chingis-khan and Jamuqa’. I wish he’d just written us a novel.

So, what are my hero’s qualities in Grousset that, set against wars amongst the worst in history, make a tragedy of him? I can start with his famous quality of magnanimity. I have to joke about this word; I don’t know whether biographers catch it from each other, but no-one escapes talking about his magnanimity. It’s a fine thing, though ill-defined. Grousset sees a certain naivety in him, from start to finish. When he quotes his complaint to Toghrul (which I believe to be near to his actual words) he describes his “rough, naïve turn of speech” in this message that, as a quasi-legal statement, is half in poetry. (Contrary to rumour, Chinggis Khan was not a bad poet, on the strength of this and two or three verses of his own. Translations can be bad.) And he is honestly puzzled to be betrayed. These qualities sit alongside his loyalty: he ‘never flinched in loyalty’ to Toghrul in spite of the latter’s derelictions; ‘unswervingly loyal’, ‘consistently loyal’ says Grousset; and every service ever done him remained unforgotten, returned unto the end of his days.

One funny thing in Grousset is his treatment of the dignity I do not doubt our shepherd-king had: how he took in his stride the giant leap of his circumstances. “Being of noble lineage, he was in soul a king, and therefore less elated than anyone by his meteoric rise to fortune.” This dates Grousset to 1939, before we discovered the Chinggisid Revolution that was anti-clan and anti-aristocracy. Mind you, Grousset might turn out to be right; a recent book – David Sneath, The Headless State – argues there was no Chinggisid Revolution and the steppe throughout was strictly run by aristocracy. I’m not convinced, but it’s a gauntlet thrown down.

That had better do for his fine human qualities. Grousset, who has talked freely of his generous soul and lofty mind, now has to explain what happened when he met China and the cities of Turkestan. His answer is culture shock, the abysm between steppe and sown, inability to understand one another, sheer ignorance on both sides. Mongols were the ‘crudest’ of the peoples who galloped from the steppe, by which Grousset means, they had the least acquaintance with the settled world. There’s culture shock – there’s crowd shock, when you think about the demographic gap. I’ve had crowd shock in a city overseas, and I live in Sydney Australia. A nomad’s crowd shock cannot be imagined by us, but mustn’t be underestimated as a factor. Grousset looks to the shock, and it’s a start.

His solutions aren’t satisfactory, but he hasn’t shied from the challenge. Most biographers, because – in my eyes – they can’t get their heads around the contradiction, have instead to walk the cynical road. It’s the choice you get. Take Chinggis at face value, or put a cynical slant on everything he says and does. As can be guessed, biographers, in this day and age, who aren’t of the cynical party are very few. What’s taken for the standard biography, Paul Ratchnevsky’s Genghis Khan, is hopelessly confused because he can’t make up his mind on this fundamental question of stance.

For instance, shall we be cynical when Chinggis scruples to be the belligerent in a war? Even my Grousset can’t say this with a straight face. Attila (unlike Tamerlane) he sees as uncannily similar to Jenghiz, and in his Attila assessment he lists traits wherein he is akin to his later distant cousin; these include “an odd legalistic streak, which led him to seek diplomatic pretexts for his actions… so that he might at any rate be seen to have right on his side.” Every book I’ve read since, I swear, has an equivalent sentence, for Chinggis’ wars in China or Turkestan or in judgement of his career: ‘a strange quirk’, ‘a peculiar concern’ – I think I’ve even seen ‘quaint’.

Now, I quarrel with the need for an adjective. What’s odd, that his society has a concept of just war? I guess that’s only for civilized folk, for enlightened Europeans and ethical Chinese. Excuse my sarcasm. The steppe had a strong belief in God as the determiner of wars; Chinggis has to urge the justice of his cause when he asks for God’s aid; a perception of justice is going to be crucial – or God won’t help the troops. Chinggis kneels on his Sacred Mountain and tells his God, ‘I did not start this war. My cause is thus-and-thus; if you find us righteous, let us succeed.’ So, what? Is he insincere? Self-deceptive? He’s known for his piety, and within his culture as he is, for him not to believe what he says here is unlikely to the point of impossible. Still, what biographer can tell us this without a wink or a smirk or a tic at the eye?

I like the way Grousset puts the thing, when he gets to Jenghiz’ own chapter: Jenghiz had among his assets “the art of getting right on his side.” That’s perfect: it’s not cynical, but acknowledges that bystanders might be bemused at how he always manages to be in the right. That little phrase may have shaped whole swathes of my novel.

In general I think cynicism is a large mistake, towards people of the past. Nothing leads astray like the need to be cynical. It’s the blindest of tendencies. In non-fiction a lie, in fiction a dull story: I have no truck with cynicism. Its opposite I see as subtlety.

Rene Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, Rutgers University Press, 1970 (translation by Naomi Walford). First published in French 1939.

May 25, 2012

The Revolt of the Frontier

North China and the steppe

To start the war against the old enemy we have a grand tale of a revolt – an unequivocal freedom fight. It is the Mongols’ glory moment. They haven’t set foot in China, they haven’t yet waded into the bloody bog that war off the steppe becomes. Tribal peoples in China’s pay, spontaneously, go over to the Mongols and give them entry. This is why the Wall isn’t mentioned in Mongol accounts: they were given the walls, which at this time were over-extended (with hindsight) further into the steppe than walls had ever been.

This piece of history has gone undetected or ignored. It is almost the work of one historian to resurrect it. That there was a major revolt of north frontier troops, and the importance of this for the Mongols’ war on China, is the argument of Paul D. Buell, who has written an intelligent, up-to-date introduction to the Mongols in The A-Z of the Mongol World Empire.

Environmental history – that is fairly new in these parts – has much input. Mark Elvin’s The Retreat of the Elephants is ‘the first environmental history of China’, where you can find out about heavy, gung-ho urbanization (and feel sorry for the elephants). On the steppe, of course, animals far outnumber people; the opposite was true in China. Another book, Abramson’s Ethnic Identity in Tang China, in a chapter on geopolitics, stresses the traditional Chinese assumption that untilled ground is ‘empty’. The steppe was known as the ‘northern wastes’, tantamount to uninhabited – in that nomad inhabitation didn’t count. Grass was a waste of space. In the Elvin you can see how every inch of space might be humanized; he describes a war on wild animals, and human labour substituted for animal traction – human poo for animal manure. Early cities he describes as great jails, with populations under extreme surveillance and control.

Back to Paul D. Buell, who gives the environmental context for the start of 13th century, when Chinggis has united the steppe and his Mongols can become the “champions” of tribal peoples under pressure. Buell paints the frontier zone between the steppe and China as “a theatre of ecological conflict”, cultivation in expansion, urbanization rampant as population growth drove Jin China to settle and farm areas nomads used for grass. The frontier zone, that can be farmed, was easily destroyed: ploughed earth led to wind erosion, which ruined the grass, too. Once farmed, ground might be left useless.

Things came to a crunch, at the right time for the Mongols. Buell pulls together evidence that the settled population at the end of the 12th and the beginning of the 13th century – in these margins between China and the steppe – had built up as never before and not since “at any later time down to the coming of the railways”. Which is amazing.

Glaringly, these facts need to be in the story. But I hadn’t read about them before Buell and Elvin. So what was the Mongols’ war about? If we decide in the absence of this evidence, we are going to be wrong. Buell for one thinks these frontier issues let the Mongols into China, bluntly — allowed and perhaps instigated the conquest.

photograph of a Mongol circa 1900

The Mongols’ most angry pronouncements – such as the oft-quoted suggestion by Mongol old guard that they turn settled China into grass – is a case of ‘let’s do unto them as they did unto us’ – is the ongoing warfare between ways of life. The suggestion was rejected. It wasn’t feasible. But my Tchingis, I think, won’t slam this old guard as quite maniacal.

In short, the tribal peoples of the frontier, when they saw the possibility – when Chinggis was named khan of a united steppe in 1206 – shook off China and joined him. The first to do so was Alaqush Digit of Onggut, in what is now Hohhot, capital of Inner Mongolia: and then was in the thick of the new urbanization. He seems to have been courageous to declare for Chinggis; he ended up murdered for it by a Chinese-loyalist faction at home. For a while Alaqush stood alone, until a general revolt of the frontier troops in 1207.

These were tribal troops, the juyin in Mongol, which I translate as the Odds-and-Ends army. Thirty thousand of them were called up – for what campaign we don’t know, perhaps against Chinggis on the steppe, perhaps against insurgents in Old Qatay. We only know they were demobbed again and straight away “went over to the Mongols”. Other information has Jin China undertake a new wall, to be garrisoned by juyin, and this lot incites the revolt.

Early in my first novel we meet a troop of this Odds-and-Ends army, mercenaries in service to China. They kill Temujin’s grandfather, but they aren’t happy with China’s uses of and attitudes towards them. If the steppe were strong and seen to have a chance – which isn’t even speculation at that point – they’d throw in their lot with their own people. Much later this happens, and the half-and-halvers identify with the steppe cause.

Paul D. Buell, The A-Z of the Mongol World Empire, Scarecrow Press, 2003. Quotes taken from pages 18-24.

Mark Elvin, The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China, Yale University Press, 2004

Marc S. Abramson, Ethnic Identity in Tang China, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008

May 21, 2012

If I go quiet…

[image error]I can feel Three upon me. For a few months I’ve lived a life such as I dreamt of ‘when the book is finished’ – in once upon a future, if I live to see the day. And it’s been great. I’ve kicked up my heels, been ushuttable-up on Goodreads, I’ve read fiction – which I cannot do while writing (years and years wiped out for fiction, an unfortunate side-effect). I’ve dwelt on old loves, I’ve pulled my past together: into a focus. Maybe I can’t go back to the hermit life, now I’m online. I wasn’t online while writing One and Two. Can you do both? We’ll see. The most fun I’ve had is group reads in Shakespeare Fans and I can’t stop that. But here’s Jamuqa, dead on his white horse and calling to me. And life starts to feel purposeless without him, who has been my purpose for nine years now. Back to the slave pits. Not this week, but next, I almost dare to say.

May 8, 2012

Two isn’t histfic; and Three?

Why did God give writers blogs? He didn’t; we invented them; it’s obviously a bad idea, but I’m going to sally out in the happy knowledge that nobody reads mine. Don’t start now.

I’m in the thinking-about-the-next stage. But not deliberately thinking; on the contrary, I’m distracted by a dozen tangents; but in this phase of conception, everything feeds in. Nothing is not relevant. Even if I try: I thought I was whiling away the empty time between books by putting up on my Goodreads shelves my early history, influential books I’ve half-forgotten. But no, and I’m even tempted to read them again, to gather the threads together, into this that is my culmination – at least the biggest canvas I’ll ever get, if not my last chance at a book. It has to go in Three, if it didn’t get into One or Two.

Much of the old stuff that meant a lot to me is sf. Science fiction I believe excellent for historical; both are world-building; there’s the alien thought to undo your mental stuckness-in-now; and sf, like nothing else, enlargens the imagination, yes? I need a dose of space opera in my past to write the kind of wars that… had not been seen in the world, although in retrospect we’re used to them. (On retrospect and war, see Peter C. Perdue, who hammers into your head, people did not know, as we do, the next event. To be conscious of this, he teaches, ‘to recapture the sense of uncertainty’, is crucial for an historian; hey, only more so for a novelist. It makes him exciting to read, and you see that most historians do not operate this way).

When the cauldron’s bubbling, nothing is not relevant. However farfetched. In the empty space between books I took up Joseph Frank’s five-set on Dostoyevsky: the writer in his time, a portrait of the Russian 19th century, its world of ideas. That crazy Russian 19th century, with every species of leftist, under a Tsar, anarchists and aristocrats and the gamut of religious opinion, all in collision (yes, no wonder Dostoyevsky wrote the books he did). So what do I think of? Thirteenth-century China. Either that’s an absurd application of the principle ‘everything is (seems) relevant (to a one-track-mind)’ or it’s an opening of the imagination to potentials. Ideas in conflict… I don’t want to waste my opportunities in 13thC China. First off we have a society in collapse, a society (use the Perdue principle) that thought – I kid you not – what they saw around them was the Fall of Civilization. Or that was one strand of thought. There was a school of poetry that came out of the Mongol conquest, called the Death and Chaos school. I have always been fascinated by ruin, and by the barbarians over the gates. I can’t wait to get my teeth stuck into this – to give a story account of those Death and Chaos poems.

There was also ‘intellectual ferment’ in Jurchen China, before the Mongols descended. A wide choice of philosophies with political implications. I’m not a China expert. Frankly, I don’t even want to become one; besides you can’t come late to a study like that. For years I’ve thought, isn’t it mission impossible for me to write in China? The first comfort I found (comfort, not solution) is that China, often, stands for Us, in my novel. I believe no other society on earth, in the 13th century, can so conveniently stand for us – at least on the issues I pursue. War: you find attitudes to war that are not foreign to yours and mine – that are exactly mine. Where else? And then there’s the civil service government, that’s familiar. In the second book, already, China has been us (example: Ile Ahai on the ‘great man’ theory of history). As a side-effect this salves my conscience, since I have to take sides. I’m afraid I haven’t had a good word to say about China yet; when I feel awkward about that I remind myself China is us.

Nor is this – I argue – invalid in the times. They thought this way. China identified itself as Civilization: so I make China stand for civilization, and that works. The worst of them, if you like, similarly to ourselves, thought in terms of Civilization (them) and the other, which I’ll just call the uncivilized for now. So when my book makes a case for the uncivilized and critiques civilization, I am doing nowise other than what they did in centuries past. Am I justified yet?

Where was I? Ah yes. I’ve never been into Chinese history, but I discovered my other solution – this one claims the name of solution – that Jurchen China fascinates me. It’s far under-studied, too, and precisely because of what fascinates me: it’s an intersection-culture of civilized and uncivilized; very traditional China scholars discount it – they simply don’t care. But intersections are what I explore on every path. Tchingis never met undiluted Civilization: he never went to South China or to Europe or to Russia. He found himself in intersections, cross-overs, melting pots, frontiers, where nomad cultures have seeped into settled cultures or the other way around, and he sees the results thereof. Well, that does capture me, that’s up my street, and I feel confidant to write about that.

There are only 2-3 books on Jurchen China in English, but they are rich in hints. Of course the reason I never studied China… I shouldn’t crudely put this into words, but obviously, pit the nomads against China and you know whose side I’m on. I can be said to be a dead-cert anti-Confucian. I study what I am in sympathy with, and that was never traditional China (again I’ll use my phrase, China is us). But Jurchen China, ah… Right before they conquered north China the Jurchen were a ‘primitive’ forest people. Their trials and tribulations in China – intellectual, philosophical, religious – can you see why the Russian 19th century is not so far afield, for a sense of ideas in conflict? And in resolution, attempted resolutions. Jurchen China has unique features, under-studied. A movement began to weld or meld the Three Doctrines – Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism – into a universal, and this happened just at the time that universalism was the big new idea on the steppe. The Chinese guy (in fact he’s Qatat) Tchingis became tight with, Ile Jutzai, was a believer in this unity of doctrines, and he can be my champion of what is unique to Jurchen China. That’s why my Tchingis gets along with him.

Onto the title of this post. Book One seems to me to be histfic, Two scarcely, and Three is going to stretch the definition. It’s T.H. White who taught me to put in my vital interests. What the hell else are you meant to write about but your vital interests? He did Nazi ants, and I promise you I won’t; he began with legend-fic, not histfic, and I won’t take his whole license. But in One, that might pass as conventional histfic, early human politics rears its head, because I care. Because I found two wonderful books and I want to tell you what they say. What is the default politics of our species? Can we even do liberty? Hey, I have determined to my satisfaction a part of an answer – that is, I have decided which books to put my trust or vest my faith in – and sorry, you’ve got to know about that. It fits into the story. It’s why I chose the story. To me, this remains how to write, and I bet that early scifi wears a little of the blame.

I hope nobody has read this far, and I mean that. A blog is a dangerous thing, in a writer’s hands. I did not do my post on the wobbles I had about Book Two. This is just as bad, though.

April 1, 2012

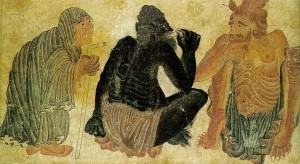

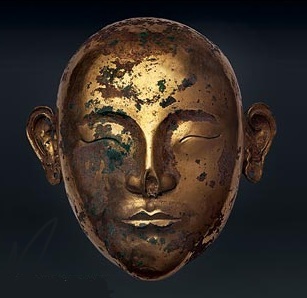

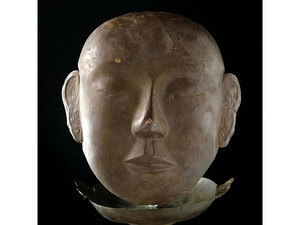

Tomb masks from the Kingdom of Qatay

Europe's old name for China, Cathay, comes in fact from a northern neighbour and rival of China's, Qatay or Khitai (or half a dozen transcriptions) between Great Khingan (Xingan) Mountains and the sea, a horse people on the easternmost steppe.

Europe's old name for China, Cathay, comes in fact from a northern neighbour and rival of China's, Qatay or Khitai (or half a dozen transcriptions) between Great Khingan (Xingan) Mountains and the sea, a horse people on the easternmost steppe.

They remained a horse people, after they acquired a great Chinese population and ran a dual government – Chinese-style for the Chinese, tribal-style for the tribals – and took on dual nomenclature. In Chinese they were the Liao Dynasty, with dates 907-1125 CE.

They remained a horse people, after they acquired a great Chinese population and ran a dual government – Chinese-style for the Chinese, tribal-style for the tribals – and took on dual nomenclature. In Chinese they were the Liao Dynasty, with dates 907-1125 CE.

[image error]These are their funerary masks. About which we know no more than we can see. We don't know whether the masks are shamanist in inspiration or Buddhist – they were ardent Buddhists; but they must have learnt to entomb their dead from China? Before their Imperial Period they left their dead in trees on holy mountains, and after three years gathered the bones to burn and bury: along the lines of other shamanists.

But their practices are unique, and I am happy to say, they created their own from these elements. These face masks, with the individual's features; and often a wire mesh wrapping the corpse – in aid of? Our guesses are merely guesses (vague waffle about shamanism). I hope to stumble on indirect evidence, a clue; then I can put them in my novel.

But their practices are unique, and I am happy to say, they created their own from these elements. These face masks, with the individual's features; and often a wire mesh wrapping the corpse – in aid of? Our guesses are merely guesses (vague waffle about shamanism). I hope to stumble on indirect evidence, a clue; then I can put them in my novel.

The mesh is silver or gold wire, the masks gilt bronze or silvered copper. Ears have ornamental squiggles or rings or flap. The expression tends to be serene, but features aren't idealised. I'll just note that Mongols, in their Imperial Period, as art patrons, encouraged a surge of portraiture. People's faces were their idea of art, and Mongols are cousin to Qatat.

It's a huge thing when a culture changes its burial practices, from a tribal style (the trees) to a civilized style (tombs learnt from the Chinese). I've read anthropology on equivalent cases, with a close-up on people's feelings. If that's what happened here; the old steppe, of course, had great burials and treasure in tombs. It's easy to over-emphasise the China influence.

This woman's face I must give you a link to. Here you can hover and see her enlarged. She's worth it. And here see the above fellow against red, in zoom: he's magnificent work that way.

I'll leave you with an odd few more: first, the most tranquil beauty, for me; second, a none-too-handsome royal woman – with her eyes open.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error] [image error]

[image error]