Bryn Hammond's Blog, page 10

May 31, 2013

A history written by the losers

It’s a quip that occurs to people: that the Mongols’ history has been written by the losers. I quipped in my author’s note; I’ve seen a blogger say so, I think I’ve spotted it in a book. History is written by the victors? No, not when the victors don’t write, and the losers do, and the losers are us or more familiar to us. There must be other cases than the Mongols, where victors don’t have a foothold in the historical record and it’s the losing side that’s heard.

The Secret History was the Mongols’ first ever book. It’s famously non-propagandist, in that it bags Temujin on several counts, and besides it was secret, not disseminated; it came to (our) light centuries later. The Mongols haven’t written our history of them. Who has? China, Persia, old Europe. Our historians are used to written sources, and until such as Gideon Shelach pushed the Chinese records aside to dig in the earth with a clear mind, the Chinese wrote our history of the steppe peoples to their north. When do you get past traditions like that? Not yet. I look at my library and think, not yet.

I am discontent with half my steppe library. Severely discontent or disgruntled or driven to despair. What researcher has to say that? Not talking about quibbles here; I’ve got quibbles with every one of them like any healthy researcher: I mean scholarly books I’d cringe to have you read.

“Can you rec me a general history of the Mongols?”

Erm.

“Biography of Genghis?”

Blah.

Outside the field (maybe inside) people must assume that Mongol studies is going strong. To me, it’s in a sad state, or just getting its legs. I have to think it’s one of the worst-written histories we possess. Not that I’ve done a great survey of others… but what other field’s novelist (poor me) has to wear a flak-jacket in her library, grow rhinoceros hide, and needs anger management as she researches?

Yes, I bet you’ve got rotten books that say rotten things. But I believe Mongol history, unto this day and age, retains the effects of a history seen through enemy eyes.

How ignorant were the European friars who journeyed among the Mongols in the 13th century? What, we expect them to understand the society they see? They are a major source for us. We fail to question them, we often fail to question our sources, step back and back again, deeper and deeper into question. Can it ever be enough?

Settled peoples won’t understand a nomad people, without the greatest efforts of mind. We’re rude enough to write their history. Our inclinations lead us to the Chinese records, the Persian, as if they were the ones acquainted with the Turks and Mongols. Yes of course they were. I’ve seen Chinese scholarship criticised as slow to shake off old prejudices. Easy for us to say, but I haven’t heard much about ours. Our history books have been slow to shake off old prejudices – let me state. You can read straight history on the Mongols and still wade through those prejudices, up to your knees.

One statement of this truth is in the David Morgan book, The Mongols, 2nd edition. For the 2nd edition, 2007, after the 1st of 1985, he adds a bibliographical chapter, on what has happened in the scholarship since. To quote:

The two decades since then have been, perhaps, more productive historiographically than any comparable period, and the subject now has a distinctly different feel to it. This is not, for the most part, because startlingly revealing new primary sources have been discovered and published… It is more that perspectives have changed: historians have begun to look at different issues. They have dug deeper into Mongol history, and their emphasis has shifted away from purely military aspects, away from the death and destruction which, while it did undeniably characterise the initial Mongol imperial expansion, is now seen as very far from being all, or even what is most important, that there is to say about the extraordinary Mongol phenomenon. The results of this new research are to be found in specialised monographs, collective volumes and journal articles. There has not as yet been any attempt at an overall scholarly synthesis…

Alas no: we don’t have a new general history. The David Morgan is still transmitted from person to person with the magic tag of the ‘standard’ history – even when the book itself acknowledges how out of date its ideas are. For he has not updated his main text, from 1985. That main text is old-school and lacks sympathy for its subject; I wouldn’t have you read it; read the added chapter, not the rest.

Sympathy’s a common-use word in my kit; perhaps it’s a novelist’s word, but I believe you can’t write history, either, without a sympathy for your subject. You can’t see your subject without a sympathy. David Morgan’s book is an example: perfectly valid history (more or less) but there’s a distance, a remove, you’re stuck in an outsider’s perspective, you’re blind to the inside story: there is no explanation. History too needs insight, needs to enter into the experience of its subjects – or else you come to wrong conclusions, as a hostile witness does. I did not like the Morgan book; my hackles rose; at the end I thought, wrong wrong wrong. Yet it’s not the history that’s wrong. In a narrow sense.

I don’t want to pick on David Morgan… it’s because he has that ‘standard’ tag. I’m every bit as unhappy with the ‘standard’ biography (Paul Ratchnevsky).

Not every old book is bad. By God no – just as there are old-school still in operation. How enlightened is Karl Wittfogel, in 1949? How sympathetic Rene Grousset, 1939? I chose Genghis as a subject after I read Rene Grousset, so that the fundamentals of my portrait I owe to him. Afterwards, the battering my brain took from the less sympathetic Genghises that stalk the history books; the walls of prejudice I met; the stupidities I saw, in histories of repute. One’s experience of history isn’t meant to be this way, is it? It must be that the Mongols’ history has largely been written with hostility. We’ve learnt; first to question old European reports, where they roast babies on stakes; next we saw that the Persian-language accounts of the war are indeed by the losers. But massacre figures from those accounts still get quoted, you know. They are quoted in the Cambridge History of Iran: Volume 5, a contribution on ‘The Socio-Economic Condition of Iran under the Il-Khans’. I’ll have to insist that if you read this, you’ll read George Lane. Me, I’ve marked this article to never read again, or if I have to, with a very stiff scotch by my chair (possibly the bottle). It’s in a Cambridge, which I only bought three years ago; old Bernard Lewis was oft-scoffed for cutting down to size those massacre figures; Paul D. Buell has an unpublished paper on their absurdity. Of course those figures get the Mongols onto the Wikipedia list of most destructive human events in history.

I named Paul D. Buell. He has the nearest thing to a general history, that I thrust on people whenever I can: The A-Z of the Mongol World Empire. It’s stuffed with new findings and is definitely new-wave, not old-school. Unfortunately not in a standard-history format, but he’s ideal to do us one, and he gives rumour of “my forthcoming general history, with the late Angelo Anastasio, and Eugene N. Anderson, Mongols and the Outside World. This will include recent Mongolian history, as well as that of the period of empire, all looked at from a unified, Mongolian perspective.” Eugene N. Anderson, on my investigations, seems just as with-it as Paul Buell; he’s a cultural ecologist; I cannot express how sorely we need this book.

In stronger terms than David Morgan, I call the last twenty years a revolution in the scholarship. Thomas T. Allsen, George Lane, Isenbike Togan. A general reader’s book that incorporates these: what a difference that might make. We have popularisers. In 2004 I walked into Abbey’s Bookshop Sydney and saw side by side in the new releases, John Man and Jack Weatherford on Genghis Khan. I bought both in hardback at once, took them home and thought, is 2004 the year of a tide-change, out there on the street? To continue in a reminiscent vein… I felt a discomfort with the Jack Weatherford at first. I’ll admit that, because I know those who won’t have a bar of him. I called him apologetics, I feared he went too far (me, with the most sympathetic Genghis in fiction, by miles). But you know what? That was defensive huddling, that was my psychic bruises, after I’d run the gauntlet of my bad-Genghis library for years. And now? The situation that I see is simple in the extreme. People read Conn Iggulden or they read Jack Weatherford. Conn Iggulden perpetuates stereotypes. Jack Weatherford is out to overturn stereotypes. My allegiances? As simple.

Maybe I shouldn’t complain about non-specialists, but they depend on Mongol scholarship, don’t they? The eminent John Keegan writes about English livestock farmers when he comes to explain the Mongols; Azar Gat is also guesswork: these seek to place steppe warfare within their histories of war. There is a gulf of understanding, and you cannot guess, to cross it. Historians’ only hope is to soak themselves in anthropology or other culture study, which old-school doesn’t do. Here’s a tip: if he/she has a French name you stand a better chance. Do the French have a tradition of more cultural awareness in their history? I swear I remember a fairer mind from the French when I used to read about Arabs.

The purpose of this post, I suppose, is to beg people to be aware, to be extra-wary, when they read history on Mongols. Know that Mongol scholarship remains inadequate and as if in its infancy (perhaps any scholarship worth its salt knows this of itself). Keep in mind how rude it is for settled people to write nomads’ history. Not that I want us not to try, but it’s healthy to see a fundamental impossibility there. I liked David Christian because he gave me a sense that the steppe way of life, since extinct, was almost a different evolutionary road. That overstates David Christian’s case, no doubt, but you need a radical sense of departure – or else you don’t have a history of nomads in your hands.

# # #

I’m an amateur Mongolist with my home library of academic books (no expense spared, to feed the novel; I live on baked beans) but without a university library or journals. This is the view from here.

Links are to Goodreads, either my reviews, the book page or the author page. I’ve done two lists on Goodreads, The Mongols for Beginners and The Mongols In-Depth, with my suggestions.

May 6, 2013

My hero - on my hero

YouTube link: http://youtu.be/v81_hm8T92c

Hey, he says in his question session, “There’s nothing objective about anything I say” — so why do I have to put an objective title up there?

The wonderful Jack Weatherford stands on a stage at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, in February this year, and talks about Genghis Khan. His focus: “who he was as a person.”

Or to quote my own Bultachu Ba’atur, as he tries to talk his wife into softening on Temujin; he points to the figures-become-legends in the epics: ‘The legend, he’s described to curl your hair, he’s the bristly brindled blue-maned wolf, he glares red when he’s roused. Beneath that once was a person. What he was like?’

Jack’s a story-teller as he gives you excerpts from the Secret History of the Mongols. The start Temujin had in life. If you ever doubted Temujin is one of the astounding people in history, let Jack lay out the facts for you.

And what an odd army he had, with which to achieve things no-one else has. Hung together on loyalty and talent — not aristocracy, not kinship. His generals weren’t the steppe aristocrats but poor herders, who never betrayed him. Kin betrayed him and he did not use kinship but found or created other loyalties. Loyalty is his most important word. Army communications? — in verse. Of course, in an oral society, where people can talk in verse, the way fish swim. He built bridges. He built nothing else — no fortresses, palaces, temples, these were alien to him and remained so. But bridges, by the hundred. He was a practical man.

With a huge creative intelligence. I’ll quote Juvaini, Persian historian, dates 1226-83 — because Jack says pretty much exactly this:

The statecraft to be learnt from the great Chosroes of old and what is written on the arts of war and method of government of the Pharoahs and the Caesars was by Tchingis Khan gleaned from the book of his own mind, without records for instruction or the trouble of traditions to observe, but self-taught by the light of the intelligence God gave him: and as for his intelligence and his ingenuity, Alexander, of the curious mind, might have been his student in contrivances for the seige of castles and in how to conquer… To his own conceptions, then, he framed the Jasaq.

The Jasaq is his law code. When the Mongolian government — freed from the Soviets, under whom you weren’t allowed to mention Genghis on the streets — planned its first official statue of him, to preside over the parliament, they took for a model that of Abraham Lincoln: not a conqueror on a horse but a lawgiver. It’s how he’s seen at home.

What sort of government did he run, himself? His government began as an army, yes, and as a distribution machine. This is a man who, fairly certainly, “accumulated more wealth than any person in the history of the world: he didn’t keep it. It went out — it went out. The first people to get a share were war widows and orphans.”

But Jack talks about a dereliction of principles, late in his life. Not a violation but… a retreat from his old principles of ability and loyalty as the only factors that matter. He too succumbed to kinship above these, undone by his love for his sons, and left the government to them. I like how Jack criticises this. It didn’t work out, it had bad consequences, and is a shame, yes. Our Temujin’s only human. Jack tells you the tragedy of Jochi, his first son, who wasn’t fathered by him, but the one Temujin loved most.

Then there’s half an hour of question time. He’s asked about The Secret History of the Mongols. Jacks stresses its intimacy: conversations he had in bed at night with his wife, are reported. This isn’t a public document to honour a public figure — hence the ‘secret’.

Ethics in war? “In warfare I think he was scrupulous… He was a practical man. But a very ethical man.”

He is asked about rape, Genghis Khan and rape. Yes, I’ve seen on the internet he’s the greatest rapist in the world. Never mind evidence, assumption is enough. Jack says: “I know of no documented case where this happened.” He explains a little about how “the whole (Mongol) masculinity is so different from ours.” With wives commonly older than the husband. “Steppe culture in general — rape was not a part of it.” He distinguishes from the kidnapping of women, in tribal life. As I do — it’s quite a different thing. So different, that I have not used the word ‘rape’ — our word rape — in the story of either his kidnapped mother or his kidnapped wife. As soon as I do, modern ideas intrude, and so I don’t. Rape in his wars? “To my knowledge it did not happen.” He wants evidence, see, and they can’t bring him any. As for me, I haven’t got there yet; I’m still in 1206.

I won’t always tally with Jack Weatherford, in my portrait. His Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World came out when I was a couple of years into work on mine — and I was over the moon at such a sympathetic portrait, in a popular history, for a wide audience. But I felt dead lucky, too, that I’d had time with my Tchingis before Jack, BJW, because that’s an Anxiety of Influence I might never have escaped.

Jack Weatherford turns out to be a great talker, if you ask me, and you did since you’re here. If you have a spare hour and a quarter… put it on while you’re knitting, and listen to Jack.

# # #

Jack Weatherford is the author of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World and The Secret History of the Mongol Queens. Here’s his author page on Goodreads.

Don’t miss The UB Post on Walker Pearce, where I link to a feature on his wife from an English-language newspaper in Mongolia. Jack gets a look-in.

May 5, 2013

My hero on my hero

Hey, he says in his question session, “There’s nothing objective about anything I say” — so why do I have to put an objective title up there?

The wonderful Jack Weatherford stands on a stage at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, in February this year, and talks about Genghis Khan. His focus: “who he was as a person.”

Or to quote my own Bultachu Ba’atur, as he tries to talk his wife into softening on Temujin; he points to the figures-become-legends in the epics: ‘The legend, he’s described to curl your hair, he’s the bristly brindled blue-maned wolf, he glares red when he’s roused. Beneath that once was a person. What he was like?’

Jack’s a story-teller as he gives you excerpts from the Secret History of the Mongols. The start Temujin had in life. If you ever doubted Temujin is one of the astounding people in history, let Jack lay out the facts for you.

And what an odd army he had, with which to achieve things no-one else has. Hung together on loyalty and talent — not aristocracy, not kinship. His generals weren’t the steppe aristocrats but poor herders, who never betrayed him. Kin betrayed him and he did not use kinship but found or created other loyalties. Loyalty is his most important word. Army communications? — in verse. Of course, in an oral society, where people can talk in verse, the way fish swim. He built bridges. He built nothing else — no fortresses, palaces, temples, these were alien to him and remained so. But bridges, by the hundred. He was a practical man.

With a huge creative intelligence. I’ll quote Juvaini, Persian historian, dates 1226-83 — because Jack says pretty much exactly this:

The statecraft to be learnt from the great Chosroes of old and what is written on the arts of war and method of government of the Pharoahs and the Caesars was by Tchingis Khan gleaned from the book of his own mind, without records for instruction or the trouble of traditions to observe, but self-taught by the light of the intelligence God gave him: and as for his intelligence and his ingenuity, Alexander, of the curious mind, might have been his student in contrivances for the seige of castles and in how to conquer… To his own conceptions, then, he framed the Jasaq.

The Jasaq is his law code. When the Mongolian government — freed from the Soviets, under whom you weren’t allowed to mention Genghis on the streets — planned its first official statue of him, to preside over the parliament, they took for a model that of Abraham Lincoln: not a conqueror on a horse but a lawgiver. It’s how he’s seen at home.

What sort of government did he run, himself? His government began as an army, yes, and as a distribution machine. This is a man who, fairly certainly, “accumulated more wealth than any person in the history of the world: he didn’t keep it. It went out — it went out. The first people to get a share were war widows and orphans.”

But Jack talks about a dereliction of principles, late in his life. Not a violation but… a retreat from his old principles of ability and loyalty as the only factors that matter. He too succumbed to kinship above these, undone by his love for his sons, and left the government to them. I like how Jack criticises this. It didn’t work out, it had bad consequences, and is a shame, yes. Our Temujin’s only human. Jack tells you the tragedy of Jochi, his first son, who wasn’t fathered by him, but the one Temujin loved most.

Then there’s half an hour of question time. He’s asked about The Secret History of the Mongols. Jacks stresses its intimacy: conversations he had in bed at night with his wife, are reported. This isn’t a public document to honour a public figure — hence the ‘secret’.

Ethics in war? “In warfare I think he was scrupulous… He was a practical man. But a very ethical man.”

He is asked about rape, Genghis Khan and rape. Yes, I’ve seen on the internet he’s the greatest rapist in the world. Never mind evidence, assumption is enough. Jack says: “I know of no documented case where this happened.” He explains a little about how “the whole (Mongol) masculinity is so different from ours.” With wives commonly older than the husband. “Steppe culture in general — rape was not a part of it.” He distinguishes from the kidnapping of women, in tribal life. As I do — it’s quite a different thing. So different, that I have not used the word ‘rape’ — our word rape — in the story of either his kidnapped mother or his kidnapped wife. As soon as I do, modern ideas intrude, and so I don’t. Rape in his wars? “To my knowledge it did not happen.” He wants evidence, see, and they can’t bring him any. As for me, I haven’t got there yet; I’m still in 1206.

I won’t always tally with Jack Weatherford, in my portrait. His Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World came out when I was a couple of years into work on mine — and I was over the moon at such a sympathetic portrait, in a popular history, for a wide audience. But I felt dead lucky, too, that I’d had time with my Tchingis before Jack, BJW, because that’s an Anxiety of Influence I might never have escaped.

Jack Weatherford turns out to be a great talker, if you ask me, and you did since you’re here. If you have a spare hour and a quarter… put it on while you’re knitting, and listen to Jack.

# # #

Jack Weatherford is the author of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World and The Secret History of the Mongol Queens. Here’s his author page on Goodreads.

Don’t miss The UB Post on Walker Pearce, where I link to a feature on his wife from an English-language newspaper in Mongolia. Jack gets a look-in.

April 12, 2013

Historical Novelists’ Spring Book Fair

Welcome fair-goers to my stall. The Historical Novelists’ 4 Day Book Fair is a get-together run by Francine Howarth; here’s her blog, from where you can browse and wander the stalls of novelists.

Ny name’s Bryn. I’d better put a face on, since we’re at a fair:

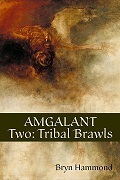

And here’s the face of my lad:

China has executed Ambaghai, the Mongols’ khan, on a hurdle with donkey ears and tail from the theatre, in mockery of the horse peoples of the steppe. It cries for hachi.

‘Hachi means that which is owed, or felt due. It can mean an act of humanity. It can mean vengeance. It meant justice.’

The Mongols go to war for Ambaghai’s hachi, in a century when no steppe people is fit to tackle China. They believe battles are won by the just, and the size differential doesn’t bother them. They are wrong, but the Mongol God comforts them with an omen. Temujin, the baby of that battle day, has in his hand his people’s future victory.

The Chinese have crossbows, but the Mongols have belief.

Of Battles Past is my FREE starter to Amgalant, the story of Chinggis or Genghis Khan. I closely follow a source, the Secret History of the Mongols. This is an intimate biography of the Mongols’ greatest figure, but uses the art of oral epic: it has frequent direct speech, frequent verse — gorgeous as a source. See my page on the Secret History for more.

Find your free copy at Smashwords, Apple, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Sony. At Amazon or Amazon UK I have to charge 99c.

If you like the first, my lad has other faces, as he grows. On these, see my page Amgalant and me. Or explore the blog; I have categories for ‘steppe culture’ and ‘Mongol history’, where I hope you can discover images and information from a world not enough known.

April 11, 2013

Historical Novelists’ Spring Book Fair

Welcome fair-goers to my stall. The Historical Novelists’ 4 Day Book Fair is a get-together run by Francine Howarth; here’s her blog, from where you can browse and wander the stalls of novelists.

Welcome fair-goers to my stall. The Historical Novelists’ 4 Day Book Fair is a get-together run by Francine Howarth; here’s her blog, from where you can browse and wander the stalls of novelists.

Ny name’s Bryn. I’d better put a face on, since we’re at a fair:

And here’s the face of my lad:

China has executed Ambaghai, the Mongols’ khan, on a hurdle with donkey ears and tail from the theatre, in mockery of the horse peoples of the steppe. It cries for hachi.

‘Hachi means that which is owed, or felt due. It can mean an act of humanity. It can mean vengeance. It meant justice.’

The Mongols go to war for Ambaghai’s hachi, in a century when no steppe people is fit to tackle China. They believe battles are won by the just, and the size differential doesn’t bother them. They are wrong, but the Mongol God comforts them with an omen. Temujin, the baby of that battle day, has in his hand his people’s future victory.

The Chinese have crossbows, but the Mongols have belief.

Of Battles Past is my FREE starter to Amgalant, the story of Chinggis or Genghis Khan. I closely follow a source, the Secret History of the Mongols. This is an intimate biography of the Mongols’ greatest figure, but uses the art of oral epic: it has frequent direct speech, frequent verse — gorgeous as a source. See my page on the Secret History for more.

Find your free copy at Smashwords, Apple, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Sony. At Amazon or Amazon UK I have to charge 99c.

If you like the first, my lad has other faces, as he grows. On these, see my page Amgalant and me. Or explore the blog; I have categories for ‘steppe culture’ and ‘Mongol history’, where I hope you can discover images and information from a world not enough known.

April 4, 2013

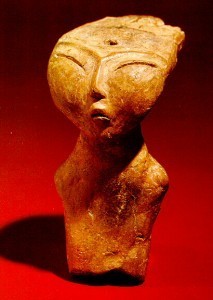

The ‘Nefertiti of the Amur’

So they like to call her. She’s from the Stone Age on the Amur River, and I’ll take her over Nefertiti.

She’s in an online gallery called Faces of the Amur. Named for a strong tradition, as old as we go, in human masks, abstract faces and portraits, as petroglyphs and clay figures. A while ago I posted on Liao tomb masks (I think I used the phrase: Tutankhamun, eat your heart out — or did I only tweet that?) where I said we know nothing about them, we can only guess at significance and context. These age-old human faces of the Ussuri and the Amur must help with context. The exhibition’s text, found on this page, stresses the continuity of culture, from archaeologists’ finds to ethnographic evidence — what’s in museums from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

There’s a book to go with this exhibition, that I own, but I think you get the full text online, and most of the images. I have to say, though, the big photo in the book makes our Nefertiti’s case more convincingly. She’s lovely, exudes ‘real woman’, and was the first human figure they found in Neolithic excavations on the Amur.

Alexei Okladnikov, Art of the Amur: Ancient Art of the Russian Far East,1981, Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad

March 30, 2013

What’s independence?

Me and my independent sentiments. Last week I read an article with an independent creed I almost never see — that expresses my unexpressed convictions. Here’s a link: Matthew Gasda, ‘How Indie Authors are Like Naked Emperors’.

(It’s on a site that one-starred my book; you’ll spot that if you explore. What can I say? This reviewer had no patience to put the time in. I gather my book didn’t suit her, don’t you?)

Anyhow. I’ll have to follow what Matthew Gasda writes; his last piece for them talked of artistic integrity — I kid you not — and how people go indie for the sake of it. What old fashioned values. Link: ‘Indie Books and Their Critics’.

Now, I went indie like a shot and mine won’t be a take-off indie, and I was quick to make the adjustment from old fantasies of the book funding me, to the real state of affairs — it’s me funding the book. That’s fine. What else is Bryn for but to slave on behalf of the book? It’s only fair and right.

Independence. For me, Smashwords has been a spokes-outfit for independence, while Amazon does not act in the spirit of indie. I sell at Amazon and shouldn’t insult them, but they have just swallowed Goodreads, which was my social life. One can’t always be polite.

Of course it’s way way better for the book if I don’t have a social life, so ta for that Amazon.

What the hell is the purpose of this post? I think, to give you that 1st link. An indie creed. The sort of indie creed I need to see more of. World?

March 27, 2013

Finished? Unfinished?

A note on my books. Can they stand alone? Do you have to wait for Three for satisfaction? How finished or unfinished is the story?

A note on my books. Can they stand alone? Do you have to wait for Three for satisfaction? How finished or unfinished is the story?

Answer: One and Two are whole books, with a conclusion to the events in them, and the themes tied up. Read One, and you’ve reached a finish. Read One and Two, and you’ve reached a finish. As for me, if I’m smashed by a bus today, I’ll be upset that I haven’t gotten to tell you my ideas on Temujin’s later life; but I, too, for my comfort, know I have reached a finish.

My instincts operate this way; I wouldn’t myself write an unfinished book, and very far from leave you with a cliffhanger, I’m concerned to give us both closure. I think you’ve a right to insist on that at the end of six hundred pages, and I have no excuses, I’ve had space to see my story and my themes out to an end. [There is a footnote to this. See footnote.]

Also, I want to be free for the next. The next has different demands, and I need the freedom to meet new questions with new answers. Each of my books has a different style — at least to my eyes, which may be hyper-sensitive. It’s a big thing for me about how Temujin changes, how life changes for him, and I’ve got to have an elasticity to capture that.

Footnote

So, what about the sections I’ve issued? Are they finished books? I’d say, #1 Of Battles Past, #2 When I am King and #4 The Sheep from the Goats — yes, these are books in themselves. Only #3 Me and Atrocity I don’t call a book, and I’m dissatisfied with the situation there.

March 16, 2013

William Napier’s Attila trilogy

I was interested enough to read these three books in a month, and they deserve a spot here as steppe fiction. On my blog I can be more personal than I am on Goodreads.

I was interested enough to read these three books in a month, and they deserve a spot here as steppe fiction. On my blog I can be more personal than I am on Goodreads.

To start off: I mostly avoid the more commercial fiction on steppe topics. I come with an inbuilt distrust of bestsellers, and when the subject is dear to me, I expect to be dismayed and upset. Right, that’s honest.

But I read William Napier. I’ll be terribly honest about him: I thought his trilogy an opportunity lost.

He’s an uneasy cross between action/adventure bestseller-style, and a fiction that I see as more ambitious, and that takes artistic licence such as removes him from the mainstream. He does weird things. Beyond what I’d do, although I defend him in my reviews (the ‘right to write’). He’s an old Yeats PhD and he can’t keep Yeats out of his fiction – or other 19thC poets, or Shakespeare. I understand this. It’s the language he talks in. If he excised that – the phrases spontaneous to his lips – then what’s he doing? Writing from a front, a censored front. Not from his self. – I just thought up that argument, on his behalf. I’m wary of fiction that… is self-limited, is from a part of the writer. “I can’t do this because action/adventure doesn’t let me. Maybe I’ll write another book freestyle.” In his trilogy William Napier oscillates between freestyle and conventional. Guess which I liked. I’ll live with him giving Attila quotes from William Blake, if that’s what the author needs to do to say what he has to say, spontaneously. If that’s how the words come to him, and sound to his ear true.

It’s radical, and again I’ll mention, my Tchingis doesn’t express himself in Percy Bysshe Shelley, much as I like the old poets. My narrator has been known to, because I do zoom out to an ‘I’ that’s me, now and then. But I’m not here to talk about my techniques, that’ll only get me into trouble.

I didn’t grow up on historical fiction. I grew up on speculative fiction and great books of the past. If that’s left me with a pref for the unconventional in hf, or an attitude of ‘rules? what rules?’ then, fine. Neither sf nor the greats are known for rules. Mine is, whatever works.

Napier’s other sin is against history and occurs in book Two. Two is the steppiest book, by far, thus guaranteed my fave. I defend his historical stretches, too:

“It draws on history before and after. I think he has drawn on Attila’s later distant cousin, Genghis – both for Attila’s life story, and for this grand conception of conquest east and west. These Huns can sing the Mongols’ origin legends, and the Turkic epic Manas. Of this I’m going to say, Napier widens history. He fits more history in. He has a time period, but he draws into that strands from before and after, because he wants to talk about historical issues – large ones. He wants to talk about the settled and the steppe, and to that end Attila, steppe spokesman, knows things he can’t have known, travels further than in any likelihood he did. As I say, this is fine by me, and makes for a fiction that comments on history.”

In Three he abandons both poets and ahistoricism. I hated Three. It was so average.

Even his style, I felt, lurched from cliché to originality, from ordinary to art. These books had the potential to cut loose from action/adventure, to contemplate history, with a prose he might have learnt from Yeats – and sell atrociously, no doubt. I regret them.

#

Painting of Attila by Delacroix

My reviews on Goodreads:

One Attila

Two Attila: The Gathering of the Storm

Three Attila: The Judgement

March 8, 2013

Single women on the steppe?

As a happy single these days, and even committed I think (that’d be a first) (enough about me) — I’m intrigued by the possibility that certain steppe societies allowed women to live singly.

As a happy single these days, and even committed I think (that’d be a first) (enough about me) — I’m intrigued by the possibility that certain steppe societies allowed women to live singly.

Liao, at least. But Liao was an aspirational society for other nomad cultures, which seem to have found them fit to imitate. Almost the only information I have on this comes from Linda Cooke Johnson’s study of Liao and Jin women, Women of the Conquest Dynasties. She offers the example of Changge (1006-1077), a scholar and poet and member of the royal clan, on whom we have a biography in Liao records. “The entry specifically notes that Changge never married, and [her] epitaph mentions no husband, which suggests that marriage may not have been universal among Liao women.” [p.7] Other than this, “The numbers of Liao tombs in which women are the sole occupants also suggest that other women may never have married.” [p.111-2]

It’s not much to go on. But Linda Cooke Johnson speculates that the Liao/Kitan custom whereby women married men of the generation beneath them may have led to singlehood. Women of the royal clan (that I like to call the Ile, instead of a Chinese transcription) were often significantly older than their husbands, but “the primary marriage pattern in which younger males married somewhat older women was common among both upper- and lower-class Kitans. Although Jin sources are less explicit, the Jurchen also evidently followed the generation-gap pattern in arranging marriages…” [p.99] We’ll want to know at this point, sex before marriage was not a no-no. “Liao and Jin sources indicate that premarital permissiveness was a widespread and well-entrenched social custom…” [p.86] We might feel that the unmarried were ‘left on the shelf’, but that’s our assumption, and this on girls’ sexuality reminds us not to make foreign assumptions.

In Mongol history, we have Qaidu’s daughter Qutulun (c.1260-1306) who tried not to marry, who wished to remain as her father’s right hand in war and politics. As I say, I believe Liao was a glamorous culture for other steppe societies, and I have to guess that Qutulun, to justify her life, cited Liao women, who before her had commanded troops — possibly she cited them on singlehood, too. That is, doesn’t the Liao information mean she needn’t have been pitted against society, to live thus? Still, Qutulun gave in to pressure, and to slander: she and her father were accused of incest, and after this she chose a husband — one of her father’s followers, which let her stay at her father’s side. I was a daddy’s girl too.

That incest accusation, a low blow, has an after-history in a Karakalpak epic, ‘Kyrk Kyz/Qiz’, known in English as ‘Forty Maidens’. There, a brother and sister lead the fight against a Persian invasion. The enemy Persian Shah slanders them with incest to undo them. The brother, humiliated, leaves his troops and people, but they refuse to believe the accusation and choose the sister to head the army in his absence. Here I must see a memory of Qaidu and Qutulun. The latter’s legend as a war champion and army leader surely went towards the inspiration of this epic, which boasts more women under arms than an average plot of Xena.

I’m afraid that’s the end of my observations. I’ll keep digging, fascinated as I am, for single women on the steppe.

– Linda Cooke Johnson, Women of the Conquest Dynasties: Gender and Identity in Liao and Jin China, University of Hawai’i Press, 2011