Bryn Hammond's Blog, page 2

December 4, 2023

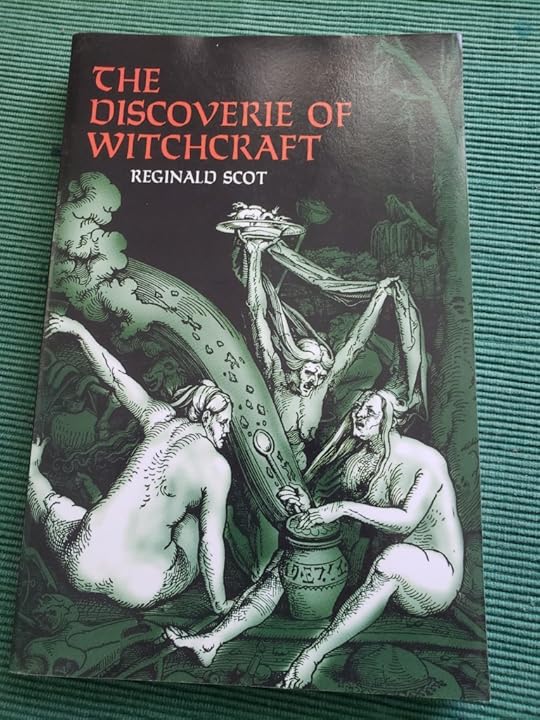

Sarcasm and compassion: Reginald Scot on witchcraft

Possibly the start of a series of essays that remain significant to my fiction writing. I have a few of these, that I felt passionately about — or thought passionately in; and that creep into my story themes — or try. First up, Reginald Scot and The Discoverie of Witchcraft, written for a Witch-Hunting unit in History.

I saw Scot in relation to the Elizabethan and Jacobean stage — both comedy and tragedy, and playwrights’ presentation of human evil. Nods to Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, Iago, and my fave, The Changeling.

Next up: my What is Tragedy? essay, if I dare after I re-read it.

Sarcasm, compassion and the stage: Reginald Scot on witchcraft

MEPHISTOPHELES Why, this is hell, nor am I out of it.

– Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus, Act 1, Scene 3, line 76

And if there be a hell upon earth, it is to be found in a melancholy man’s heart.

– Robert Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy, Partition 1, Section 4, Member 1

This essay looks at Reginald Scot’s strategy and tactics as a writer in the Discoverie of Witchcraft. His strategy is to expose ‘cousenage’, from the physical tricks of legerdemain to the belief structures of demonologists. If he can unmask the one, can he not un-construct the other? Merely bracketing the jugglers and the intellectuals in his screed against cozenage works like the strategy of a play where comic subplot is associated with tragic main plot. One tactic Scot shares with Elizabethan and Jacobean playwrights is witty speech – the provocation of laughter, by which he exposes absurdity, both in the concept of witchcraft and in the trial of witches. The playwrights are justly accused of failure to seriously engage with the contemporary topic of the witch-hunt; but they did seriously engage with the question of evil. Scot’s main enemy is the sense of Satan’s presence in the world, and his answer can be seen in the light of stage plays that treat of evil and its human agents.

Scot’s witty speech is involved with his attacks on the absurd: when his sarcasm effects a smile, then the illogic he points to is killed with humour along with contempt. Sarcasm is not low wit for Scot, not beneath him; neither is the pun; the anti-Catholic joke is a given.1 His sallies seek to clinch an argument by amusement or thrust a point home on his rapier wit: witty speech is his most ready weapon. He lampoons demonologists even as he draws out their arguments to absurd conclusions, extrapolates from what they say to use their own logic against them. He is often funny to read. This has not been enough noticed; perhaps the humour is thought an adjunct to his argument, a delivery system, rather than being an integral part of the missile itself.2

Where else in the sources can humour be found? Stuart Clark in his grand analysis of demonologists’ language does not identify humorous weapons in their arsenal; his section on ‘wit-craft’ is about clever speech, not about wit as upon the stage; the only humours in the learned writings of his study are the medical understanding of the day; laughter, it seems, was not a tool of his intellectual demonologists.3 Certainly ‘M. Mal.’ and Jean Bodin, ‘their principall doctors’ for Scot, do not construct their case by wit. Possibly wit is more suited to deconstruction, to the sceptic. Marion Gibson takes English pamphlets as her study, and finds that even the grave ones can feature humour; furthermore, there is a category of ‘triviall’ pamphlets which treat witchcraft frivolously, at a time when people are being hanged and the public is supposed to be in the grip of fear of witches. Gibson asks us not to neglect this ‘trivial’ evidence of another attitude Elizabethans and Jacobeans had towards witches.4

Comedy in the circumstances may challenge our understanding, but the same can be said for comic subplots in the Elizabethan play. In these the comic and the earnest cohabit, often uneasily to us. Like Clark’s festivals of misrule, the stage comedy and the comic subplot in a serious play can incline either to conserve or to subvert the order of the establishment (whatever that is in the context of the play).5 On stage, comedy can be tipped towards the conservative or the subversive by a performance, and of course by its audience. Festivals of misrule were live performances, too.

Performances of Doctor Faustus used tricks from Scot’s repertoire for its stage effects of magic. This play’s stage Lucifer, its machinery of devils, its close imitation of conjuration in the theatre, can be played for fear even to a post-Christian audience.6 But the stagedness may be fatal to earnest fear. If the devil on stage is a thing of masks, of smoke and mirrors, perhaps the off-stage devil is questioned, deflated, seen (if only for a moment of confusion) as spectacle. Scot equates jugglery with conjuration to mock the latter. In the case of Doctor Faustus, comedy infiltrates the main plot: audiences are invited to laugh with Faustus and Mephistopheles as they bamboozle the corrupt pope in Rome and the silly emperor of Germany. Anti-Catholicism opens a crack; it is a wedge exploited by Doctor Faustus and by the Discoverie of Witchcraft. A devil play that laughs with Mephistopheles through half of the action pulls in different directions; the opportunity to thumb one’s nose at Europe allows in what Stuart Clark calls ‘the relativity of the devil.’7 Clark identifies an opportunity in the new plurality of confessional faiths – when the church is not one edifice. Of course, it is not sufficient to be anti-Catholic to achieve a distance from the witchcraft construct. As Scot observes himself, one piece of that construct can be questioned, disproved, yet other pieces remain intact and the construct knits together again in people’s brains.8 Christopher Marlowe has been reputed an atheist; Reginald Scot has been reputed a member of the Family of Love.9 Whether or not either speculation has truth, both are taken for radicals in their work. Marlowe’s Faustus has also been interpreted as a conservative and truly Christian play, but it is a send-up, it is not a sermon.10

Scot employs the send-up, in that he particularises the opposition’s beliefs (his ‘inventory of devils’) and extrapolates from those beliefs with the ‘what if?’ question, until they are exposed as absurd. One of his counter-arguments is to point out that if witches’ impossibilities were possible, these decrepit old women would much more resemble the great stage Satanist, the learned doctor, Faustus. Like him, they would advise princes, muster imaginary armies out of the air, and obtain for themselves fabulous wealth. Furthermore, the kingdoms of Europe would be in chaos – with thousands of Doctor Faustuses at large. Does this resemble reality? he asks. The misrule that must ensue were witches real is like the slapstick scenes of Doctor Faustus, in every prince’s court.11

In addition, Scot brackets illogic with injustice. When he critiques the conduct of witch trials, he brings out the absurdities. Magistrates too are cozened, by procedure he unpicks as illogical – including torture which he attacks as absurd too, so that miscarriages of justice must be the result.12 Witchcraft cannot be seen as irrational belief; the trouble is it was rational by the thought structures of the day.13 Stuart Clark explains it was locked in by the structures of language, by which a contrary had to exist (if God, then Satan) and where logical extension was sufficient to convince people, above evidence, in the face of evidence.14 Scot is aware of the obstinacy of belief, upon which simple disproofs do not work.15 He addresses his book to the magistracy of England among other intelligent men: he knows witchcraft makes sense to persons of reason.16 His attacks on its logic, from his ‘let us assume it true’ extrapolations, to his argumentation as to why torture does not detect the guilty, are an attempt to dismantle pieces of the thought-world that makes witchcraft in his time a rational proposition. To point out the preposterous, to ridicule, or better, to construct a ridiculous case by the opposition’s own logic; to make men laugh at a facet of the false beliefs: this is his way forward, into a ‘time to come’ when witch beliefs ‘will be as much derided and contemned, and as plainlie perceived’ as the goblins once believed in.17

To banish God’s great contrary the devil, with his hosts of demons as against the host of angels, from the world, from activity on earth, might require both feats of logic to unpick how people think, and an address to their human recognition of the accused human agents of the devil. Scot comes back again and again to the trope of ‘potable babies’ – infants’ flesh rendered down into a soup that may be drunk.18 The idea of potable babies stands for Scot as the great unlikelihood. When one looks at an old woman in court and imagines she has made a hundred babies potable – then that is such a failure of human recognition as staggers Scot’s mind. He simply attempts to point out its obvious impossibility on another level, a level of sane thought as to what people do and what is too wicked for people to be doing, by the thousands, in our own neighbourhoods.

On human recognition, he has an ally in the playwrights. There are trivialisations of witchcraft that modern persons find difficult to excuse: Diane Purkiss says Shakespeare scholars go into interpretive contortions to make of his three Weird Sisters in Macbeth a significant commentary on the subject. In her investigation of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama she finds no more serious, or more sympathetic, stage witch extant. Our greatest playwright has failed us.19 However, let us not forget, the witch is personified evil. Attention is directed to Satan, while the witch is the one with malice towards other humans, neighbours, who chooses to perform these foul acts – the acts Scot disbelieves as inhuman, not humanly possible, on the scale imagined. Scot expends his pen on what is not an intellectual demonologist’s argument, but is about the acceptance of a dangerous fantasy as to deeds our neighbours do in their homes. This fantasy of evil, detached from real observation, to which intellectuals are at least as subject as other folk, he sees perpetuated by scare tactics, both demonologists’ literature and old wives’ tales fed to us early (if Scot is elitist in his scorn for ‘what our low-class nurses told us’, as Purkiss charges, he has equal contempt for the knowledge structures of the learned).20 This is the crux of the matter. The witch was personified evil in that on trial for her life was a person, accused of huge malignancy, an exaggerated wickedness.

When playwrights present an individual figure of evil actions and ask why, this too can be acknowledged a response to witchcraft. Iago is Shakespeare’s treatment of the perplexity of evil in human guise. To stage an Iago, and puzzle the audience as to why he ruins lives, must be seen as topical. Elizabethan and Jacobean playwrights did engage deeply with questions of evil. From Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy (1580s) to Middleton’s The Changeling (1622) – also in Spain, although Italy was popular – tragedies were set in Catholic lands where the playwrights could not only stage sensational action, with the anti-Catholic tropes of poisoning and illicit sex, but discuss evil’s place in the world and its existential position. In The Changeling, De Flores is a figure for the devil: a fallen gentleman, of ugly visage, Beatrice’s servant who, when engaged by her to perform a wicked piece of work, becomes her master, and for his end of the bargain demands sexual intercourse with her. This is the very devil’s pact of witches, although Purkiss only attends to Middleton’s direct portrayal in his comedy The Witch.

It is witches in the real world who suffer this being personified – being caught up in the contraries Stuart Clark analyses, whereby Satan was inflated to be (almost) God’s equal and opposite, and oppositional faiths were locked into a language of antagonism, into extremist positions.21 There was no room in such a totalising of evil, a totalising of the opposition, to be an ill-favoured, nasty old woman and not be of the devil’s party – a witch. De Flores is typecast into his devil figuration by his face. As a matter of fact it is Beatrice who tempts De Flores, to whom he succumbs: she assumes that a foul face is made for criminal work, and it is his exclusion from the opportunity to woo her in any other fashion – because of his ugliness – that leads him to agree. From there, evil actions are contagious, the contamination has set in. If a Kentish wife can be mad and yet not of the devil, if a crotchety old woman can curse her neighbour and yet not go home to practice dark arts upon him, then there is that ‘gradation’ that Clark sees as lost to the language and its conceptual structures.22 One thing leads to another, in the rhetoric of the day. Purkiss thinks Scot insults the crotchety old women,23 but this is not to the point; it is important that he does champion those hard to champion, those most easily categorised in the extreme of evil. If a petty affront, then a major crime: this is the thinking he wants to undo. It would not achieve his purpose to exempt the victims of witch trials from eccentricity, difficult tempers, distempers of the mind or ugly faces.

These are the people in danger. The Changeling has sympathy for the devil in that De Flores begins as an unfortunate whose preoccupation with Beatrice is not less to be called love than the emotions of her suitors. Macbeth has no sympathy for its witches, but the playwrights make it their business to humanise the agents of evil (it is in Lady Macbeth, or Macbeth himself, we might better look for comment). This of course is to work against the demonising of people. The demonologists, quite simply, demonise people, Scot finds, by their intellectual structures and their use/misuse of evidence. A person cannot be half bad in the contraries structure of Clark, whether Calvinist or Catholic; and herein lies the danger to the vulnerable of society, who are already seen as half bad or a quarter bad or a difficulty to the community. The thrust of a plot like The Changeling’s speaks to the inevitability of a mildly disassociated person like De Flores falling further – and this because of people’s expectations of him. Macbeth and Lady Macbeth undergo this progress into evil. Must a poor Essex woman, turned away at a door, inevitably be led by her rancour into the stereotypes that await her as a witch? Scot attempts to say no.

If Shakespeare does not grasp the nettle of the witch trials, directly, then neither do other admired writers, Robert Burton (1577-1640) with his Anatomy of Melancholy and Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) in his essays. For Burton, a witch may cause or be caused by melancholy, but he has nothing to say about melancholics misunderstood and on trial for their lives; Montaigne once meets accused witches and vaunts his strict impartiality of mind; he does not go on to write an essay on the witch-hunt.24 Both authors deal largely with what is Scot’s main defence: the psychological explanation, ‘the force of imagination’, and the sick imagination of melancholy.25 Scot rests on the medical doctor Weyer for his understanding, but he finds in melancholy madness a sufficient explanation even for cases he has witnessed. Burton writes feeling pages upon self-harm as the main ‘prognostic’ for the melancholy condition; Montaigne writes an anecdotal essay on people’s strange readiness to die.26 For Scot, such gleaned information (he and Burton in particular share authorities) demolished any difficulty posed by those cases where witches voluntarily cast themselves into the arms of the law – judicial suicide.27 As to that sad phenomenon, self-cozened witches, a book like Burton’s – a catalogue of mental illness – easily explains these, and Scot is convinced.28 His ideal story is that of the Kentish husband who so compassionately opposes his wife’s belief that she is a witch and has done harm.29 If only every woman self-abused to self-accuse were possessed of such a husband, Scot seems to say. Without him, she would have been hanged; just as, if Job’s story happened now, ‘a few old women would hang for it’ – this line or its similar is one of Scot’s themes, inserted as a chorus to his song.30 It has his traits as a writer: angry under an off-hand phrase, with scorn and compassion at work together.

Sarcasm and the argument by absurdity can be seen as a sceptic’s weapons, if Scott’s demonological opposition are conceded to have little humour. Judicial procedure against witches is also absurd in Scot’s hands: he scoffs at the illogic in the construct of witchcraft and in its proofs in court. Scot champions the victims of witch trials in their sickness, ugliness, or their common human malice; and this restores what Stuart Clark calls ‘gradation’ – the avoidance of absolutes. Sympathy for the (human) devil is almost unavoidable in a well-written tragedy like Othello, Macbeth or The Changeling, where evil action is seen in gradual steps and does not explain the whole of the personality. Scot’s most sentimental stories tend to this end, as does his pity for the unfortunate.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Burton, Robert. The Anatomy of Melancholy. Ed., Holbrook Jackson. New York: New York Review Books, 2001.

Marlowe, Christopher. Doctor Faustus and Other Plays. Eds., David Bevington and Eric Rasmussen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Middleton, Thomas and Rowley, William. The Changeling, in Three Jacobean Tragedies. Ed., Gamini Salgado. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969.

Montaigne, Michel de. Essays. Trans., John Florio. 1603. Renascence Editions: http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions, accessed 30 March 2016.

Russell, Ian (director). Doctor Faustus (video recording). London: Globe Theatre On Screen, Opus Arte, 2012.

Scot, Reginald. The Discoverie of Witchcraft. New York: Dover, 1972.

Secondary works

Almond, Philip C. England’s First Demonologist: Reginald Scot and the ‘Discoverie of Witchcraft’. London and New York: I B Taurus, 2011.

Clark, Stuart. Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Davies, S.F., ‘The reception of Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft: Witchcraft, magic and radical religion’ Journal of the History of Ideas 74 (No. 3, 2013), pp. 381-401.

Gibson, Marion. Reading Witchcraft: Stories of Early English Witches. London and New York: Routledge, 1999.

Hopkins, Lisa. Christopher Marlowe: A Literary Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000.

Purkiss, Diane. The Witch in History: Early Modern and Twentieth-century Representations. London and New York: Routledge, 1996.

Wootton, David, ‘Reginald Scot/Abraham Fleming/The Family of Love’, in Languages of Witchcraft: Narrative, Ideology and Meaning in Early Modern Culture, pp. 119-138. Ed., Stuart Clark. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2001.

Footnotes

1 Reginald Scot, The Discoverie of Witchcraft (New York: Dover, 1972). Examples of sarcasm in III xv, IV ii; of puns in III iv; of anti-Catholic jokes in III ii, IV iii. Passim.

2 His humour is not discussed in Philip C. Almond, England’s First Demonologist: Reginald Scot and the ‘Discoverie of Witchcraft’ (London and New York: I B Taurus, 2011), or in the other works consulted for this essay.

3 Stuart Clark, Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

4 Marion Gibson, Reading Witchcraft: Stories of Early English Witches (London and New York: Routledge, 1999); for ‘trivial’ pamphlets, see pp. 113-49.

5 For festivals of misrule, see Clark, Thinking with Demons, pp. 11-30.

6 Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus, A-text, 1604; for a performance which seeks to recreate Elizabethan stage machinery and effects, see Ian Russell (director), Doctor Faustus, video recording (London: Globe Theatre On Screen, 2012).

7 Clark, Thinking with Demons, pp. 134-48.

8 Scot, Discoverie, I vi.

9 Arguments for and against Scot’s Family of Love connection found in David Wootton, ‘Reginald Scot/Abraham Fleming/The Family of Love’, in Languages of Witchcraft: Narrative, Ideology and

Meaning in Early Modern Culture, ed., Stuart Clark (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2001), pp. 119-138; S.F.

Davies, ‘The reception of Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft: Witchcraft, magic and radical

religion’, Journal of the History of Ideas 74 (No. 3, 2013), pp. 396-401.

10 For the debates on Marlowe’s atheism and the play’s Christianity, see Lisa Hopkins, Christopher

Marlowe: A Literary Life (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000), pp. 65-84.

11 Scot, Discoverie, III viii and xiv, parallels Doctor Faustus, Acts 3 and 4.

12 Scot frequently touches on torture; for example, II xii.

13 Clark is certainly not on his own but he states this strongly, Thinking with Demons, pp. 3-10.

14 Ibid., pp. 43-93.

15 Scot, Discoverie, I vi, again.

16 For the persons Scot dedicated the Discoverie to, and whose perusal he hoped for, see Almond,

England’s First Demonologist, pp. 1-20.

17 Scot, Discoverie, VII ii.

18 Ibid.; first mentioned II ix.

19 Diane Purkiss, The Witch in History: Early Modern and Twentieth-century Representations (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), pp. 179-230.

20 For Purkiss on Scot’s elitism, see Witch in History, p. 64.

21 Clark, Thinking with Demons, pp. 43-68.

22 Ibid., p. 61.

23 For Scot as misogynist, see Purkiss, Witch in History, p. 217.

24 Robert Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy; witches cause melancholy, Pt. 1, Sec. 2, Mem. 1, Subs. 3; witches are caused by melancholy, Subs. 6. Michel de Montaigne meets witches in his essay ‘Of Cripples’.

25 ‘Of the Force of Imagination’ is the title of an essay by Montaigne.

26 Burton, Anatomy, Pt. 1, Sec. 4, Mem. 1; Montaigne, ‘That the taste of Goods or Evils doth greatly depend on the opinion we have of them’.

27 Scot, Discoverie, III vii.

28 Burton, Anatomy, Pt. 1, Sec. 3; Scot, Discoverie, III vii-xi.

29 Ibid., III x.

30 Ibid., V viii.

October 27, 2023

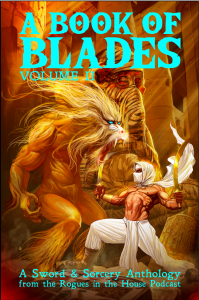

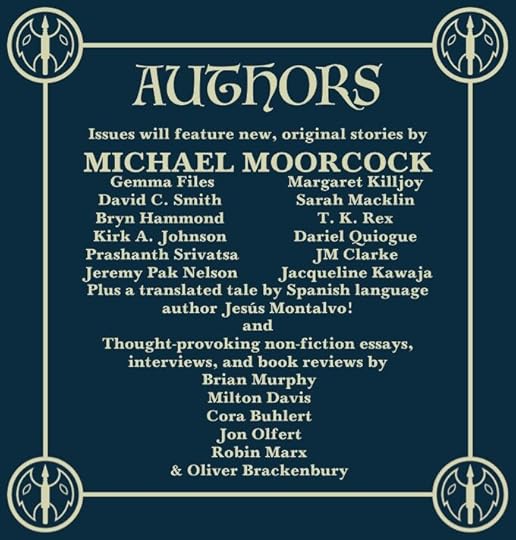

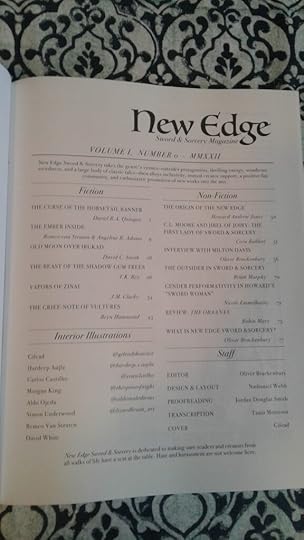

New Edge Sword & Sorcery #1

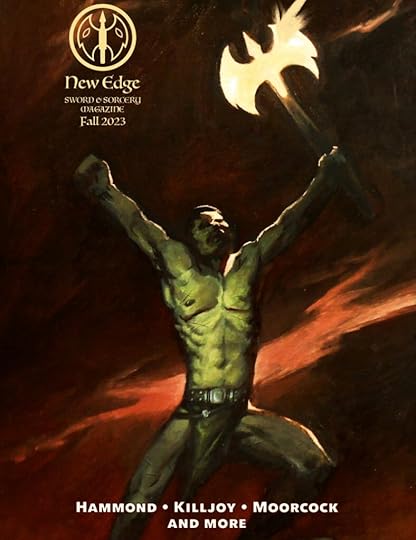

New Edge Sword & Sorcery Issue 1 is out and proud.

Caterina Gerbasi gives us a trans man barbarian for our cover hero — with a cheeky tip of the hat to Frazetta’s ‘Against the Gods’.

Thrilled to have my name on the cover alongside Margaret Killjoy and … Michael Moorcock? How did that happen?

Starburst Magazine says:

‘New Edge Sword and Sorcery is a fantastic success’

www.starburstmagazine.com/reviews/new-edge-sword-and-sorcery-magazine

The mags are going to ship real soon. Until then, you can preorder issues 1 & 2 here:

ness.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

And keep up with news at the New Edge Sword & Sorcery site:

newedgeswordandsorcery.com

August 8, 2023

The new Secret History

First impressions of the newly-out translation of The Secret History of the Mongols by Christopher P. Atwood for Penguin Classics.

Poetry. See my post on Mongol slang. From that you can gather that Atwood’s stated goal to render the poetic techniques of the original – a lack in previous translations – is one of the things that most excited me. It’s so important to convey the use of language, the imagery, and the imaginative world that is constructed from figures of speech, idioms, and the lines of verse Mongols used for emphasis or in emotion. I was highly anticipating this aspect of the translation, while uncertain how the aesthetics might go, Atwood being a Mongolist with no avowed poetry in his CV.

Well, that’s about where I end up after reading it.

It’s great to have the original’s verse features signposted. Atwood gives us lines that work well: ‘choke on the cheese and gag on the grease’ for a figure of speech around milk foods and meat foods (Mongol imagery is very bodily). Other picks are less happy: ‘chubby-cheeked/Lovely ladies’ for the convention of rounded faces in a moon-like beauty. Still, at least it tells you the alliteration is there.

General comments: First and foremost, I expect great things now that we have the Secret History of the Mongols in a Penguin Classics edition. Accessible. Acknowledged. Widely available, at a cheap price. None of the previous translations have been affordable and easy to acquire. Let it become as well-known in English as an Icelandic saga! (to which Atwood compares it in his introduction).

I am relieved that this supersedes both the scholarly Igor de Rachewiltz, whose reductive, negative view of Mongols is inserted too freely into his translation, and the popular Paul Kahn, who smooths out ambiguities and makes everything familiar. Because of his concern to imitate stylistic features, Atwood has often chosen between the literal and alliteration: he goes with the latter. People who fall in love with the text still want to consult the obscurantist, old-fashioned dignity of Cleaves, and the cultural specificity of Urgunge Onon. These two read more strangely than does the new Atwood, but the thirteenth century ought to feel strange to us.

Let’s look at a passage in side-by-side translations. Here’s young Temujin’s poem to his holy mountain, where he hid from an enemy.

In Francis W. Cleaves:

When Temüĵin, descending from on [Mount] Burqan, striking his breast, spake, saying, “Mother Qo’aƴčin,

Because she heareth

Like a weasel,

Because she seeth

Like an ermine,

Escaping as to mine own body,

With a horse hobbled by [means of] the tether,

Walking in the paths of the deer,

Making an abode of a tent of elm twigs,

I went up to [Mount] Burqan.

By [Mount] Burqan Qaldun,

As to my life [which is only] so much as a louse,

I escaped.

Sparing

Mine only life,

With an only horse,

Walking in the paths of the elk,

Making an abode of a tent of willow switches,

I went up on [Mount] Qaldun.

By [Mount] Qaldun Burqan,

As to my life [which is only] so much as a grasshopper,

I was shielded.

I was caused to be sore afraid. Every morning I shall sacrifice unto [Mount] Burqan.

In Urgunge Onon:

Temüjin then came down from Burqan and said, beating his breast, ‘Because mother Qo’aqchin

hears like a weasel

and sees like an ermine,

she saved my life.

On the dotted tracks,

[I] followed the deer trails.

I made a yurt of willow.

I climbed Burqan.

On Burqan-qaldun,

my life was like that of a louse.

I managed to flee.

My only life was spared.

With only one horse

I followed the elk trails.

I made a yurt of twigs.

I climbed Qaldun.

On Qaldun-burqan,

my life was like that of a swallow.

I was protected.’

‘I was greatly afraid. Every morning I shall sacrifice to Burqan-qaldun, and every day I will pray to it.’

In Atwood:

Temujin descended from the heights of Burġan and, beating his chest, said, ‘Because Mother Qo’aqcin,

Like a weasel kept her watch,

Like an ermine cocked her ear,

Hastily fleeing hale and whole,

A hobbled horse I led on trails of hinds;

Dwelling in a den of dense-tied willow laths,

I hiked the heights of high Burġan

And hid my life, like a little louse, in Burġan-Qaldun.

Saving as much as my poor self,

One mere mount I led on moose’s trails;

Watching from a home of plaited willow wands,

I made my way on wide Qaldun,

And kept my life, like a cricket’s chirp, in Qaldun-Burġan.

I was very frightened. I will do anointing every morning, I will do remembrance every day to Burġan-Qaldun.

The Secret History and me

And this is how I included Temujin’s poem in Amgalant:

On the heights Temujin, oriented to the sun, humbly knelt nine times and gave his humble verses, in a murmur, as though straight into the spirit’s ear. His thanksgiving verses had a childish quality; they had odds and ends of children’s safety spells.

Through great fear have I lived;

Through great grace I have my life.

I walked where the wild creatures walk,

I slept with twig and tree for tent,

Where I had fled onto Holy Old Haldun.

On Haldun the Old and Holy,

Such as I am, I was saved.

Sorely afraid, my life as frail as flea’s,

I lay in the wild creatures’ lairs,

I wove a roof of willow.

In the skirts of Haldun, Holy and Old,

The sparrow, spared by heaven, escaped the hawk.

Upon his ninth knee he finished, and flung himself out on the earth.

In a while he rose and spoke, shyly now he wasn’t couched in verse. “I vow you food from my food every day of my life.”

My Amgalant series is an engagement with this text. Indeed I go so far as to talk about the Secret History, its strategies, its meanings, within my first novel, Against Walls. An unusual way to write today, but I adopted it from TH White’s occasional commentary in The Once and Future King on his beloved source, Malory’s Morte d’Arthur; also I’d read too much 18th century fiction, when authorial asides were the fashion, and so personable. In the second novel, Imaginary Kings, which dives deeply into Temujin’s or Jamuqa’s point-of-view (half and half), I still weave my prose out of translation from the Secret History, but I don’t pull back to discuss it. The reader has learnt enough about the Secret History in One, and doesn’t need that inside glimpse into what I’m doing with the text; so I let each book accrue its own stylistic features, as arose from the material. On the other hand, Imaginary Kings has the heart and the guts of the Secret History’s story around Temujin and Jamuqa and Toghrul (To’oril) Khan, that political-personal plot told as intimate epic in the original, and in mine. Everybody, in the vast cast of Mongols and others, speaks the speeches they give in the Secret History; only, as a wise reviewer said, I amplify my original to make a novelist’s sense of its cryptic utterances. In the above review John Caviglia lights on the phrase ‘novelized exegesis’ and that’s exactly how I thought of the process.

The new Secret History, and a sale

First impressions of the newly-out translation of The Secret History of the Mongols by Christopher P. Atwood for Penguin Classics.

Poetry. See my post on Mongol slang. From that you can gather that Atwood’s stated goal to render the poetic techniques of the original – a lack in previous translations – is one of the things that most excited me. It’s so important to convey the use of language, the imagery, and the imaginative world that is constructed from figures of speech, idioms, and the lines of verse Mongols used for emphasis or in emotion. I was highly anticipating this aspect of the translation, while uncertain how the aesthetics might go, Atwood being a Mongolist with no avowed poetry in his CV.

Well, that’s about where I end up after reading it.

It’s great to have the original’s verse features signposted. Atwood gives us lines that work well: ‘choke on the cheese and gag on the grease’ for a figure of speech around milk foods and meat foods (Mongol imagery is very bodily). Other picks are less happy: ‘chubby-cheeked/Lovely ladies’ for the convention of rounded faces in a moon-like beauty. Still, at least it tells you the alliteration is there.

General comments: First and foremost, I expect great things now that we have the Secret History of the Mongols in a Penguin Classics edition. Accessible. Acknowledged. Widely available, at a cheap price. None of the previous translations have been affordable and easy to acquire. Let it become as well-known in English as an Icelandic saga! (to which Atwood compares it in his introduction).

I am relieved that this supersedes both the scholarly Igor de Rachewiltz, whose reductive, negative view of Mongols is inserted too freely into his translation, and the popular Paul Kahn, who smooths out ambiguities and makes everything familiar. Because of his concern to imitate stylistic features, Atwood has often chosen between the literal and alliteration: he goes with the latter. People who fall in love with the text still want to consult the obscurantist, old-fashioned dignity of Cleaves, and the cultural specificity of Urgunge Onon. These two read more strangely than does the new Atwood, but the thirteenth century ought to feel strange to us.

Let’s look at a passage in side-by-side translations. Here’s young Temujin’s poem to his holy mountain, where he hid from an enemy.

In Francis W. Cleaves:

When Temüĵin, descending from on [Mount] Burqan, striking his breast, spake, saying, “Mother Qo’aƴčin,

Because she heareth

Like a weasel,

Because she seeth

Like an ermine,

Escaping as to mine own body,

With a horse hobbled by [means of] the tether,

Walking in the paths of the deer,

Making an abode of a tent of elm twigs,

I went up to [Mount] Burqan.

By [Mount] Burqan Qaldun,

As to my life [which is only] so much as a louse,

I escaped.

Sparing

Mine only life,

With an only horse,

Walking in the paths of the elk,

Making an abode of a tent of willow switches,

I went up on [Mount] Qaldun.

By [Mount] Qaldun Burqan,

As to my life [which is only] so much as a grasshopper,

I was shielded.

I was caused to be sore afraid. Every morning I shall sacrifice unto [Mount] Burqan.

In Urgunge Onon:

Temüjin then came down from Burqan and said, beating his breast, ‘Because mother Qo’aqchin

hears like a weasel

and sees like an ermine,

she saved my life.

On the dotted tracks,

[I] followed the deer trails.

I made a yurt of willow.

I climbed Burqan.

On Burqan-qaldun,

my life was like that of a louse.

I managed to flee.

My only life was spared.

With only one horse

I followed the elk trails.

I made a yurt of twigs.

I climbed Qaldun.

On Qaldun-burqan,

my life was like that of a swallow.

I was protected.’

‘I was greatly afraid. Every morning I shall sacrifice to Burqan-qaldun, and every day I will pray to it.’

In Atwood:

Temujin descended from the heights of Burġan and, beating his chest, said, ‘Because Mother Qo’aqcin,

Like a weasel kept her watch,

Like an ermine cocked her ear,

Hastily fleeing hale and whole,

A hobbled horse I led on trails of hinds;

Dwelling in a den of dense-tied willow laths,

I hiked the heights of high Burġan

And hid my life, like a little louse, in Burġan-Qaldun.

Saving as much as my poor self,

One mere mount I led on moose’s trails;

Watching from a home of plaited willow wands,

I made my way on wide Qaldun,

And kept my life, like a cricket’s chirp, in Qaldun-Burġan.

I was very frightened. I will do anointing every morning, I will do remembrance every day to Burġan-Qaldun.

And this is how I included Temujin’s poem in Amgalant:

On the heights Temujin, oriented to the sun, humbly knelt nine times and gave his humble verses, in a murmur, as though straight into the spirit’s ear. His thanksgiving verses had a childish quality; they had odds and ends of children’s safety spells.

Through great fear have I lived;

Through great grace I have my life.

I walked where the wild creatures walk,

I slept with twig and tree for tent,

Where I had fled onto Holy Old Haldun.

On Haldun the Old and Holy,

Such as I am, I was saved.

Sorely afraid, my life as frail as flea’s,

I lay in the wild creatures’ lairs,

I wove a roof of willow.

In the skirts of Haldun, Holy and Old,

The sparrow, spared by heaven, escaped the hawk.

Upon his ninth knee he finished, and flung himself out on the earth.

In a while he rose and spoke, shyly now he wasn’t couched in verse. “I vow you food from my food every day of my life.”

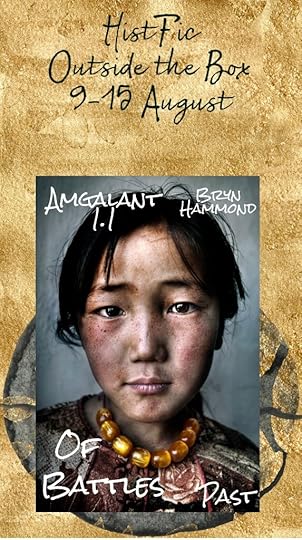

Our HistFic Outside the Box offer is running Aug 9-15. My ebooks are 50% off on Payhip (direct from me), and my craft essay, Voices from the Twelfth-Century Steppe, is a free download.

You can think of this sale as a celebration of the new Secret History, since my Amgalant series is an engagement with this text. Indeed I go so far as to talk about the Secret History, its strategies, its meanings, within my first novel, Against Walls. An unusual way to write today, but I adopted it from TH White’s occasional commentary in The Once and Future King on his beloved source, Malory’s Morte d’Arthur; also I’d read too much 18th century fiction, when authorial asides were the fashion, and so personable. In the second novel, Imaginary Kings, which dives deeply into Temujin’s or Jamuqa’s point-of-view (half and half), I still weave my prose out of translation from the Secret History, but I don’t pull back to discuss it. The reader has learnt enough about the Secret History in One, and doesn’t need that inside glimpse into what I’m doing with the text; so I let each book accrue its own stylistic features, as arose from the material. On the other hand, Imaginary Kings has the heart and the guts of the Secret History’s story around Temujin and Jamuqa and Toghrul (To’oril) Khan, that political-personal plot told as intimate epic in the original, and in mine. Everybody, in the vast cast of Mongols and others, speaks the speeches they give in the Secret History; only, as a wise reviewer said, I amplify my original to make a novelist’s sense of its cryptic utterances. In the above review John Caviglia lights on the phrase ‘novelized exegesis’ and that’s exactly how I thought of the process.

July 3, 2023

Now with sword & sorcery

I’ve made a new tag: sword & sorcery.

As reported in this post, I’ve plunged into the contemporary sword & sorcery scene lately. We have a couple of Discord servers with a nice — and lively — sense of community; if you want to have a look around them, hit me up for an invite (email bryn at amgalant dot com; also find me on the new socials, @brynhammond.bsky.social; @bryn@wandering.shop).

Today I have a story out in A Book of Blades Volume II from Rogues in the House Podcast. It’s a Goatskin story, like my two in New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine Issue 0 (free in epub/pdf) and Issue 1, due around October. ‘Goat Against the City God’ in A Book of Blades is the first S&S I wrote, and kind of an origin story for my Goatskin — in which she picks up a sword. Goatskin is a goatherd nomad living in a fantasy-Tangut on the eve of the thirteenth century, and her tales are grounded in my Amgalant research.

There are thirteen other contemporary sword & sorcery authors in the ToC, including Oliver Brackenbury, editor at New Edge Sword & Sorcery (that’s NESS for short).

Buy A Book of Blades II on Amazon

Paperbacks available now, and ebooks … any moment now?

March 4, 2023

Love and Conquest at the Gates of Samarkand

Written for Jules, posted here for L——. You know who you are.

I have this story up alongside my old fanfiction on Ao3. But one or two people have been missing Temujin and Jamuqa — as I was myself when I wrote this story in 2020. It’s a snatch of them post-Amgalant. It’s fanfiction, by which I permissioned myself to be a bit more indulgent than in the novels.

The story has a retrospective on Temujin and Jamuqa. If you hate spoilers, perhaps beware.

Love and Conquest at the Gates of Samarkandby Bryn

‘I’ve aged.’ Temujin fingered the skin of his face and thought how coarse he must look, to a love who did not change.

‘Gives you character. I like my men the way I like my leather: rumply, hardworn.’

This wasn’t true at all, in Temujin’s memory. ‘Since when?’

Gently he admitted, ‘Since you aged.’

They first met when both were eight years old. Jamuqa had lived to thirty-nine. Now Temujin was fifty-three, and Jamuqa a spirit. At this answer the mortal one of them felt a warmth of comfort, as from a fire and boiled food.

Fast march across the winter Kizil Kum – Red Sand – ought to seem like home to a Mongol, even though local guides told them nobody travelled through the desert. It wasn’t meant to be a feat to get to Samarkand, not for a Mongol army, but the khan’s old limbs disgraced them.

‘We’re at the gates of the enemy capital,’ said Jamuqa, ‘unexpected, by a road they don’t bother to put on the maps. We beat the wet, which would have bogged our horses to the elbows. Can you be less hard on yourself?’

‘We did this, Jamuqa. You and I.’

‘That’s more like it. The rest of Mongols, they came along for the ride.’

‘No. But when we made Mongol unity our cause, at twenty, did you envision we’d be here? Three thousand miles from where we started, and no lost battles to our name.’

‘I knew we’d never run out of enemies. But what feats the felt-tent people find possible, united? I had no idea.’

On his army’s urgent march Temujin, their Tchingis Khan, had not claimed the privacy of his own felt skirts about him. Tonight, while they waited outside the Samarkand gates for daylight, he set up his little travel-tent. Although he heard Jamuqa’s voice in the busiest day – in battle – still it was a luxury to concentrate on him and shape his presence.

He had obligations, before he indulged himself: spirits require gratitude, Jamuqa Spirit no exception. ‘The Hwarazm shah’s coins call him “the Second Alexander”, for his conquests where Alexander the Great once conquered kingdoms. It is your tactics which have undone Hwarazm.’

‘Not yet.’

‘We are at his capital and the shah is nowhere to be seen. He has run away from us and left his cities to defend themselves. Thirty years ago Mongols knew an obscure Mongol on the steppe to be the most intelligent tactician of the age. Now they know you preside in spirit over our victories. It is you who outface this legendary Alexander.’

‘Watch out about Hwarazm shah’s ridiculous titles, Temujin. Defeat him, you inherit them.’

This was a tease, since Temujin didn’t like the flattery of titles beyond Tchingis, his kingly name from God. When a challenger for kingship Jamuqa had gone in for extravagant titles – “universal khan” – in a game. Because, as he confessed at the last, he had secretly favoured his childhood friend, his blood brother – never truly his rival.

Titles weren’t safe ground perhaps, to dispute between them. Besides, Temujin was in a mood for more intimate subjects. ‘Yesterday in the desert Bo’orchu told me a tale of Alexander. West of here near a city Hamadan can be seen the Shir-e-gamgin, the Melancholy Lion. It is a lion in stone Alexander commissioned upon the death of his friend Hephaestion. The king of beasts, stooped to the ground with his head low: this was Alexander, in the midst of great conquests but sunken on his knees with grief.’

‘Bo’orchu told you?’

‘Yes. In apology, if you like, for his old suspicions of our friendship. I answered, that was me in the year up until you joined me as a spirit. He remembered me then, and agreed.’

‘The year of my absence. Before my death, instead of afterwards.’

‘Yes. It was that period we equated with description of the statue. Newly khan of the whole steppe, but without you. Distance I was used to, different sides in conflict. But you withdrew from us entirely, and you were ill.’

‘I tried, Temujin. I tried to leave you gently. I left you my tuq, which a man doesn’t part from alive. You were my other self, and I gave you this symbol of my soul. I declared myself dead to public life and went into the mountains, to live at peace for the time my illness let me. I’d warned you I wouldn’t live to forty.’

‘It was hard to think of you in that condition. When I was meant to feel triumphant. I hope you won’t say I was weak. Alexander survived his dead friend by eight months, and only thought of monuments to him and not of conquests.’

‘Well, I didn’t know what state you were in. Don’t imagine I did what I did for your sake only, Temujin. By my tuq in your hands I thought to have a piece of me in the great work you had ahead of you. A piece of me wasn’t enough. So I came back and asked for my execution.’

Temujin shivered, still, at mention of it. That event had been his most hair-raising hours on earth, never mind the wars he had participated in since.

He quoted to himself Jamuqa’s argument in persuasion of him to the act:

We have drunk our blood with lightning ash and holy Onon water: that drink shall never be dissolved. That drink is in my veins, your blood and mine, the alcohol of us, our selves and the charisma that in each of us has cast a spell upon the other. Then let us use the old techniques, techniques to tie one dead to one alive.

A rival, killed with preservation of the blood by the one who vanquished him, becomes his slave in the spirit world. Jamuqa, in his eagerness to live through and with his blood brother, turned himself into that tethered tutelary spirit.

‘And so I have a fortune Alexander did not have,’ smiled Temujin. ‘Certainly I wouldn’t have proved a great, but continued a poor figure like that lion. Few of my friends, I admit, understood our friendship while you lived. But they saw how our union in spirit salvaged me.’

Outside the door of the tent, with his horse and weapons ready to go, stood Jamuqa’s tuq of black yak hair, the Mongols’ banner when at war. Temujin’s own white-haired standard was kept for days of peace, and had only flown at short intervals since Tchingis Khan owned both.

Jamuqa fell silent for a while. Temujin lay down to ease his back, on comfy skins that had come off animals in Altai Mountains (where Jamuqa’s bones were sealed inside a tree). Through the smokehole overhead the stars shone over Samarkand city, which kept a strange quiet for its concentrated population – an unimaginable mass to Temujin, despite that he had seen cities. The Mongol army, of course, made its nightly noises and no more: no unseemly excitement, no faults of discipline.

Jamuqa’s face bent over him, the image cutting in on his half-closed eyes. He saw Jamuqa with his eyes either shut or open. ‘Do you know what?’

‘No.’ Temujin shook his head awake again, but stayed on his back with Jamuqa in the familiar one-legged squat beside him.

‘Never mind Alexander, who wasn’t such a big thing where I lived. Do you remember Sultan Sanjar, a hero of mine when I was young?’

‘I do. Your heroes were rare.’

‘These were his grounds eighty years ago. The last Great Seljuq, and the only one of them arguably great in a personal capacity. Your hero, Ile Dashi of Black Qatat, defeated him.’

‘Let’s not argue heroes. That was the Battle of Qatwan, and I respect both sides.’

‘It didn’t stop Sanjar, who waged war until he was seventy. I heard about him as if he were my uncle, but you know what nobody told me? When I was in love with you and young.’ Jamuqa’s triangular face, as he said this, changed the way a cloud changes, into his face at twenty. ‘When I tried on you what was illegal and we argued.’

Temujin didn’t want to interrupt him, although he itched to expand on that too-brief account: how they discovered they were both in love, and spent a legendary night together – before the famous argument, which was about integrity as much as illegality.

At the age he was he knew to simply listen and let Jamuqa talk.

‘There I was, a young Mongol who liked cock as much as he liked ayrag, or ever so slightly more. Now Bo’orchu suggests acceptance with his Alexander story, but when I was alive I was the bad influence on you.’

Temujin shut up at this juncture too.

‘Nobody told me Sultan Sanjar had a love life. His was a mess. In no way exemplary for a young Mongol to follow. But it was mamluks.’

‘Mamluk soldiers? It’s the first I’ve heard myself.’

‘See? I had to get the gossip as a spirit. If I’d known that fact about him at eighteen, I might have had the nerve to say, I’m the other kind, like Sultan Sanjar.’

‘Tell me about his messes.’

‘Several of them. He’d fall infatuated with a soldier and grant him offices above what he was fit for. Then, when his piece proved corrupt or crashingly incompetent, there’d be a public bust-up. Public, since both held public offices. You and I, Temujin, decided we were public figures – both in the running to be khan, and in those circumstances we couldn’t contravene the law.’

‘To be fair that was me, when young and stupid, and you took the side of love. Was there scandal for the sultan?’

‘Complaint, as his aides and peers mopped up the damage. Lampoons sung in the streets. Despite it, he remained the greatest of the Seljuks, talked about in the fashion I heard when I was young.’

‘Private lives are often swept away for public figures. Sanjar’s government was otherwise a fine one. I hear of him in anecdotes about his sense of justice. Because he stood high in general estimation, mischievous speech didn’t take hold of his reputation like a weed. I understand it, as a matter of fact. I am wrapped up in respect, such that I feel stifled in sable furs.’

‘No Mongol wants to taint you, Tchingis, with gossip of that sort. Even if they have to exculpate me.’ Jamuqa knocked a hand on his upright knee. ‘I wish I’d had the courage to announce myself explicitly. Before I involved you in risk of exposure, before our night together. But after I’d been given generalship over the Mongols’ first war in ages, and we won. Twenty years old, at the peak of my reputation. I could have told the assembled chiefs: you can cut my head off, or you can ask me to direct your wars, it’s up to you. But I’m a man who lies with men.’

To have to live dishonestly hurt Jamuqa, Temujin knew. Mongols valued honesty, and Jamuqa was Mongol. He said, in hopes to help, ‘I have urged them towards an honest memory of my life and acts. I have encouraged them to gather different people’s accounts, and I have related mine, whether I am proud or ashamed. Oddly, this leaves me confident that history has a circumstantial knowledge of how I killed my half-brother for theft of food from the family, when we were nearly starved, in my childhood. But how I loved? I have not given the collectors a precise report of you.’

‘You won’t, either. I won’t let you. It’s too late for gestures of that sort.’

‘Alexander has a great love story attributed to him. He seems to me exceptional. I think I won’t, although I had two great loves: my first wife Borte; my anda Jamuqa, and great matters hung on the course of those loves – the khanship, our work for the unity of Mongols. They should not believe the private side of life less important to record.’

‘I am no Hephaestion,’ said Jamuqa, ‘and might have spoiled your chances there. Loyal lieutenant to the great one. Whereas your history and mine: it’s complicated. After our argument I fought against you, and later I pretended I did, in order to send you information on your enemies. Out of this I have the name of untrustworthy. No mate for you, in story.’

‘That’s not fair.’ Temujin thought of his own words on the night he agreed to Jamuqa’s execution. Across the arena where men slay and are slain, our stomachs were hollow for each other. ‘You sacrificed for love more than any man whose story I have heard. First your reputation, to cede to me the glory. In the end your life, to be with me.’

‘I did tear up my reputation in your service, and I don’t regret that now. It isn’t acknowledgement I ask for. I find a pity, I concede, that one of your virtues goes unacknowledged, Temujin. Your constancy. It wasn’t easy to love the two of us, your queen and me, amidst the demands of public life. You did extraordinarily well.’

The compliment only made Temujin feel guilty. ‘In the past, perhaps,’ he said, to deflect it.

Jamuqa smiled knowingly, and didn’t insist.

By Temujin’s early ideals, sex meant a union of persons. He experienced that with one, and then, confusingly, with two. But where he did not love there was no soul exchange in the act, and he used to suffer from a sense of void. Used to, because Jamuqa was with him always now, which rescued him from that effect.

Jamuqa interpreted his face and offered, ‘It’s complicated.’

‘Did Sultan Sanjar have children? I forget.’

‘He had political wives, a couple, as a king of course, and out of one of them two daughters. And no end of nephews and cousins. That wasn’t why he was the last of the Seljuqs.’

Even Jamuqa had had a political wife, but no issue. Temujin’s child count stood at thirteen. After Borte, his other wives were matters of diplomacy, and he had learned to pay them the attention they were due, although Borte was the mother of nine.

‘I am not a poor husband any more,’ he said to Jamuqa, ‘and glad I am not. But you know I still prefer these nights when I commune with you alone.’ The queen he had brought on the western campaign, Ulun, had custody of the baggage wagons, which hadn’t crossed the desert.

‘“Commune” is your word now? Do you remember the description you once gave me of the melting-together spirits do? Back when I didn’t believe in spirits, but to listen to your talk, I wanted to.’

‘Yes. I do.’ He picked up Jamuqa’s spirit-hand, admiringly. Jamuqa was put together like an antelope, and he like a bear. ‘More fantasy on my part than knowledge. Rather obviously, I was justifying that we wait.’

‘You were helping me to sublimate my passions.’

‘I was stupid,’ he said for the second time that night. ‘And I don’t know whether I believed myself. I told you we’d have forever in the afterlife…’

‘It’s lucky I believed you, at the end. And took the jump to join with you, when the horses trampled me. I’m forever, Temujin. It only gets better when you’re a spirit too.’

Temujin, at fifty-three, believed him absolutely. This voice in his head, this image in his eyes. His dead love, with whom he conjured up a bliss impossibly sublime, even in their single night together at nineteen.

***

In his most uncertain hours Temujin thought he had killed his friend, by a rite which Jamuqa never believed in but staged for Temujin’s sake, to let him go gently, to give him an idea to hold onto.

For Temujin did have dark hours in these conquest years. Wars off the steppe were on another level than struggles between tribes at home. Jamuqa had taught him war, Jamuqa had been the one armoured up inside against hard sights. Tchingis Khan performed what was expected of him, but when he couldn’t help but shut his eyes he pushed his tutor spirit into the driver’s seat and hid at the rear of the wagon, in a wicker hutch of the mind like the layer of felt around him now where he lay at one with Jamuqa.

***

Dawn struck the gates of Samarkand. Alexander once conquered here. More recently, the city’s self-titled king, the Second Alexander, Hwarazm shah, had massacred its inhabitants in a three days’ sack as punishment for revolt. Ten thousand lives paid for the same number of residents from Hwarazm whom Samarkandis had killed in the streets.

Hwarazm shah had only won Samarkand thirteen years ago, to add to his rapid empire, to call his new capital for the prestige its depth of history lent him.

Today it was Tchingis Khan with his fearsome reputation, and two options.

Samarkand’s inhabitants chose the one that wasn’t massacre again. They sent out their unconditional surrender.

#

The complete Amgalant is 50% off in our HistFic Outside the Box on BookFunnel 1-7 March:

February 7, 2023

Why New Edge sword & sorcery?

Why am I involved in New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine? I have been a historical novelist for nigh on twenty years, but last year and this one – if our Kickstarter funds – have entangled me in a rush of enthusiasm for inclusive, and innovative, sword & sorcery. Let me explain myself.

There are a few key things I like about sword & sorcery. It is set apart from epic fantasy or high fantasy by its outsider heroes, its low or private stakes, and a weirdness that remains unexplained. At least, those three things are what I like. I’ll comment on them one by one.

Outsider heroes. Where do I start? By the time I ran into Colin Wilson’s cult classic The Outsider, I had already found for myself most of the books he features, and they had been important to me. It was like, yeah yeah, tell me something new. I had gone through my Seven Pillars of Wisdom craze, I had begun my continuing obsession with the works of Dostoyevsky, I had latched onto William Blake. This is not advice to read The Outsider, which is a grab-bag, probably, of popularisations and pop psychology. It is just to say what I gravitated to.

And why? Discussions on ‘what makes sword & sorcery’ have got into focus for me why. Of course, I’m a queer woman whose growing-up was bedevilled by gender expectations and your old heteronormativity. These were my serial foe, my Moriarty or my kryptonite, my danger. I do not know the person I’d have grown to be without them. I have a deadname, like an alien inside me to this day. Society excluded me from its basic institutions such as marriage. So, is S&S for queer people? You bet. The hero is an outsider, and stays that way: the hero doesn’t win a kingdom, isn’t reconciled into the majority, doesn’t join the forces of law and order in the end.

Which leads me to low stakes. Private adventures, serial adventures feel more true to my experience. Small gains – often lost again; survival; motivations that seem to the privileged to be selfish: these feel real to me.

And a weirdness that remains unexplained. I am not greatly into horror (one arm of S&S reaches into horror) but neither am I into magic in my fantasy. The weird is where I like it, and when I am writing weird, I am going to incline towards the monsters. Because I’ve been on the side of the monsters since I was a kid. Now, this isn’t necessarily the main thread of S&S, but it’s a strand. When the evil of your story lies in privilege, in civilization – when sword & sorcery, famously, from its Conan beginnings, takes a ‘barbarian’ perspective – then sympathy for monsters is just around the corner. My version of Beowulf (explicated in this poem) was always a monster himself, and rather than slay them for the safety of society, perhaps he should have joined them.

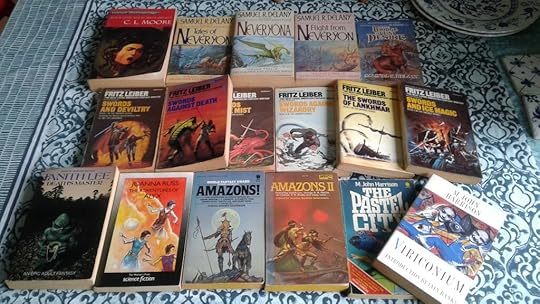

Here’s a photo representative of the sword & sorcery I grew up on. In genre, I grew up much more on science fiction and fantasy than on historical fiction, and there’s a lot to be said about that – or for that – which ought to be a post. I liked plenty of SFF flavours, and among them (particularly when they gave me an adventurous woman of her hands), S&S.

Special shout-outs to Charles R. Saunders’ Dossouye stories in the Amazons anthologies (also in the first few of Sword and Sorceress), who wrote a fighting woman with astonishing ease where others floundered and embarrassed themselves [1]; to M. John Harrison’s Pastel City, whose atmospheric prose and moody story were my Platonic Ideal as a young writer; and to Delany, for his wresting inside-out of sword & sorcery that engaged the intellect’s sense of adventure as well.

I won’t here go into sword & sorcery antecedents which have figured hugely in my history – from Beowulf and Gilgamesh to chivalric romances: if you know me you know these been my bread and butter, but they belong to another post.

In the S&S present, two that most excite me published in the last couple of years are Sometime Lofty Towers by David C. Smith, for its psychology and its postcolonial plot, and The Red Man and Others by Angeline B. Adams and Remco van Straten, for its realism, its relatableness, and for being a crafted artefact (get the paperback). And of course, New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine – its test Issue 0, its line-up for 1-2, and its potential.

We have a Kickstarter running until March 5 to fund issues 1 and 2. I beg the gods, not only to fund, but to reach the first stretch goal, which means not one but two illustrations to each story and nonfiction piece. Because you’ve got to preview the art, which you can do on the Kickstarter page with our nineteen artists’ samples. And look at the author names! Margaret Killjoy … an old bloke called Michael Moorcock …

Do I want to be in one of these issue’s ToCs, with one and maybe two illustrations to my story? You bet. More than I want much of anything right now, so – if you can help fund us, if you want these gorgeous magazines, puhleese have a look at our Kickstarter.

Have a look, too, at Issue 0, FREE in epub/pdf, available at-cost in paperback and hardcover.

#

Footnote.

1. The same can be said for Robert E. Howard’s Dark Agnes, but I discovered her only recently. I’d agree with and possibly push even further the argument in Nicole Emmelhainz’s ‘Gender Performativity in Howard’s “Sword Woman”’, in New Edge Sword & Sorcery Issue 0.

Beowulf poem

I had this up at Green Splotches journal for speculative poetry, but they seem to be down. So I’ll post here. One day I’ll blog about what Beowulf has meant to me, but … this poem says most of it.

A Monster to Fight Monsters

The dragon lies quenched in the sea, I lie in state on my pyre

and the people sing.

Of the world’s kings, Beowulf had been

The tenderest-hearted, the gentlest in spirit,

Truest of loyalty, thirstiest for glory.

A funny thing to say about a king

in elegy, but that’s my story:

Lof-geornost was I, yearningest for love,

most eager to earn it – gentle monster.

I was a monster on the humans’ side.

They say he has the strength of thirty in his fist’s grip.

The words they used for monsters fit me too:

giant, freak, and wonder.

Yet the tale is of our two-way love affair.

Nor only at home. When I went to the Spear Danes

I spoke my beot before Hrothgar

in Heorot hall, where humans sat to feast by day,

an ogre in the night.

The chief of Scyld’s children sat downcast

As his strong heart strove under his heavy grief.

– Not after me.

I presented my boast, as requisite:

how I had swum with water-snakes and harpy fishes,

dragged to where they banquet at the bottom of the sea;

I throttled them and threw them on the shore.

(I am an innocent monster, on your side. I can help.)

Happy were the stranger Danes to believe in me,

in my advent against Grendel’s visitation.

All celebrated me,

his goblin arm nailed to the gables, torn by mine.

Heorot rose up, arched gables

Like a hart’s gilt horns – not yet, not for years, but to be

Burnt in the blaze ignited from the ashes

Of old hate, old shames among the oath-sworn.

Heorot since has blazed away, and by no dragon’s fire.

I have slain you, dragon, and you me,

because that is what we monsters can.

Then there is what we can’t.

Grendel’s terror campaign was simple, though atrocious;

the unfightable isn’t from the outside but within.

I watched them try to peace-weave, spider’s webbing on a wound;

plug grievances the way they stanched a beer keg,

but the harp has a line about feud:

Chests lost grip on the uproar of hearts.

Give me ogres, give me dragons,

let me not participate in human argument.

One time I performed a stunt in battle –

staved in Dayraven with my naked embrace

(as if I were wrestling monsters)

but my fame wasn’t won in ranks of war.

In spite of that, my people thrust me on the Geatish throne

for faithful service to the royal family, self-wiped-out;

and because I had no human strings to snarl the knot of feud.

Never a wife, nor children, and no knowledge.

Not even a fine king saved his house.

I drove ogres from Heorot and left it to its own.

Now feuds wind home to the Geats.

Mismanaged foreign marriages, cut reconciliations.

So the societies of humans

makes themselves extinct through their self-contradictions,

as they have before. We, too, walked in ruins

of an architecture we ascribed to giants.

I did what I am expert in.

The Weather Geats only had Beowulf to send,

old to the bone, against the ancient drake.

For firefighters such as Beowulf and Siegfried

arrive, rare birds, out of nowhere, nobody knows why.

A few of us go wild.

But I remained tame until my end:

ogre-big, obediently sitting at the feast;

as if they strapped a dragon to make a flying milk-cart;

and they idolised me in proportion to my size

because I might have been a Grendel, and was not.

You were outraged, dragon – you and the others I killed

felt cheated, when you felt me: this isn’t a man!

You and Grendel both, of course,

infatuated with their things, as much as I with them:

you on your hoard of wrought utensils,

he fascinated by the music.

As the War Swedes sweep over the Weather Geats

bury my bones not far from human voices,

even if unknown. Like Grendel once,

I want to hear them sing.

Down from the Spear-Danes’ early days,

That grandest age under the clans’ kings,

We hear of heroes, the tales of how they triumphed.

In his heyday Scyld Scefing sailed

To seize fortresses and free the sea.

The panic of war bands he became, who had been

Once a baby abandoned to the weather.

He found ease from those times, his fortunes rose,

His honour climbed up under the clouds of the sky

Until throughout the whales’ streets, in a wheel about him,

Cities submitted and sent him tribute. He was a true king.

January 24, 2023

What’s up with Amgalant?

Last year I hit ten years since I published Amgalant One and Two in 2012.

A lot has happened, to me and to the world, in ten years. A lot of bad stuff, frankly. I am not the same person, and Amgalant – can’t be the same book.

I dread turning out one of those delayed series finishers or sequels that either don’t fit, or prove to be unreadable. It’s common and a distinct possiblity. Too, I am afraid that I have deteriorated and do not own the brain space (cognitive issues, though perhaps now solved, have interfered in those ten years). Sales remain low to nonexistent for weeks at a time, and I have been tempted away into writing short fiction that people actually read.

Ten years is time to draw a line. I’m drawing a line under Amgalant – which, true to its title, now stands as the story of the unification of the steppe. This is how I have framed the series description:

Amgalant series

‘Amgalant’ means unity.

This story is about the unification of the steppe under Tchingis Khan (Chinggis, Genghis). From the shattered condition of the Mongol tribes before him, up to 1206 when Tchingis is acknowledged khan over the different peoples of the steppe.

Amgalant likewise follows Temujin, the boy who becomes Tchingis Khan,

from an outcast life of poverty to the achievement of his dreams.

The forty years from 1166 to 1206 saw great drama on the steppe, although settled societies off the steppe scarcely noticed. That remains true to this day.

Temujin’s rise to instatement as Tchingis Khan is the heart and guts of the Secret History of the Mongols, more important to its Mongol creators and audience than

the off-steppe conquests afterwards.

The Secret History of the Mongols is a gorgeous source for a novelist,

rich in human interest and incident. Amgalant follows this source

with humble fidelity to the history and faith in the art of the original.

The series does not end abruptly. I never believed in publishing unfinished story, and on principle, each book finishes its business. Yes, Tchingis is still alive at the end. His eyes are on the horizon. It ends upbeat (oh, I notice both the books do — hell, so do those of the four-set), and I like that.

Whatever comes next won’t be Amgalant. It’ll be post-Amgalant. That half-million words of raw material and draft I have for the projected third (see last January’s report)? Presently I am extracting strands and gobbets to shape into a novella or short novel. Another novella has suggested itself beyond that. I’ll tell the story. But in different ways. Not locked into a trilogy, I am free to reconfigure that material, even in radical ways, that suddenly seem doable to me. Whatever else, it’ll be short works. My thinking has become short-term.

I want to go on writing other short fiction too, whereas Amgalant (2003-2012) was a drown-out-everything-else commitment (moreover, when I deliberately didn’t have a life and didn’t do social media). Those days are gone, whether or not my writing self can turn out work to the standards of Amgalant. I’m not even pessimistic on that point, as I am excited and enthusiastic about the novella I have in hand.

(Its working title is ‘The Khan’s Orchestra’, and I tend to let off steam about it on my Twitter).

You can buy the Amgalant series direct from me here at my Payhip storefront.

October 7, 2022

Fantasy Tangut story

I have another story out, this one quite Amgalant-adjacent: ‘The Grief-Note of Vultures’ in New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine.

It’s set in a fantasy version of Tangut (the ‘Great State White and High’) in the late 12th or early 13th century. This is where I’m at in writing Amgalant Three, Scavenger City: off-steppe, the fringes of the steppe, contested frontiers between steppe and settled. That’s where my head is, and so this story.

My fantasy-Tangut is a bit of a dystopia, at least for nomads. Those steppe frontiers have a history—and an urgent present, at the turn of the 12th-13th century—of forced settlement, of anti-nomad policies. As well, Tangut was a place of steep inequality, as disclosed to me in The Economy of Western Xia: A Study of 11th to 13th Century Tangut Records by Shi Jinbo—an invaluable close-up on Tangut in open access.

The story plot began with a tidbit I glimpsed years ago: a hell scene that seemed to be a semi-realist picture of torture, state-comissioned shortly after the conquest of the area. A caption speculated that the atrocities of conquest were re-interpreted in this religious art, in validation or even in an obscure contrition. Well, that has gone into my draft for Scavenger City, and I pulled it out to serve as the nub of this short story. For Tangut and its art, visit the site of the International Dunhuang Project

What else is historical in the story?

On spirits, my human-animal amalgam-spirits and spirit behaviour in general, as always, my first source is Shamans And Elders: Experience, Knowledge And Power Among The Daur Mongols by Caroline Humphrey with Urgunge Onon. I cannot say too much about this book, but said a bit in my Goodreads review.

I have a woman ‘king’ of bandits. She is inspired by Yang Miaozhen, who led a force of ten thousand bandits in the chaos of North China under Mongol invasion, and when she went over to the Mongols, was appointed to a governorship by them. I feel that this commoner woman’s career, as bandit leader and as governor, was only possible in the chaotic situation, and so I link my bandit with chaos. On Yang Miaozhen, the necessary article is ‘Yang Miaozhen: A Woman Warrior in Thirteenth-Century China’ by Pei-Yi Wu in the journal NAN NÜ: Men, Women and Gender in China (2002).

Angaj-Duzmut and friends have other stories in progress. I have cast them in pre-Chinggis Tangut, with the thought that in future I can have them live through a fantasy Mongol invasion. On Chinggis Khan and Tangut, see my rather long post.

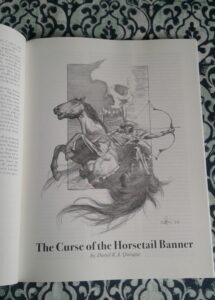

There is a second steppe-related story in the magazine. ‘The Curse of the Horsetail Banner’ by Dariel R. A. Quiogue riffs, fantasy-style, on Chinggis history. Seen here with art by Hardeep Aujla.

New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine’s Issue 0 is free in epub and pdf, and available at-cost in paperback and hardcover. Go here: https://newedgeswordandsorcery.com/