Bryn Hammond's Blog

September 9, 2025

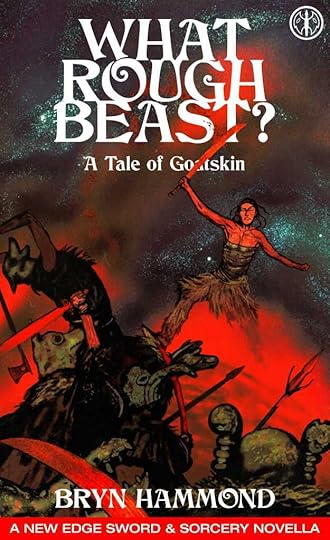

What Rough Beast?

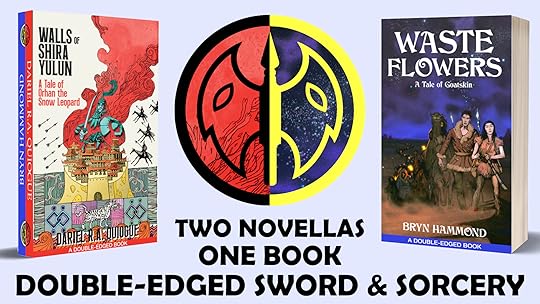

Art by Goran Gligović. I am thrilled with this cover.

~excerpt~

They did not light a fire. Stars were thrown spectacularly close up here. No moon was out.

Until a glow slid through chinks in stone on the far side of the ring, behind cultists who turned to the encounter in a stance with lifted arms, pale flares licking at them like disastrous meteors, and slowly the moon loomed above the rim. As spooky a moon as Duz had seen, with as near a thing to a face: a blistered, cracked, eroded face, bleary eyes in heavy pouches, an old person’s slobbery pout. A monstrous moon.

It seemed their signal.

Down at the fair the young had favoured city liquor, mash you buy cheap in the wine shops – even though summer was the time for fermented milk in frothy vats, sweet and astringent, a sting and a tang on the tongue. Duz had indulged to bloat on bubbly milk. Now the stick insect Duz had leapt carts against dragged out a night-black yak calf and quickly slit its throat. They caught its blood in a leather pail, and then they poured in milk – milk others freshly squeezed from the dead calf’s mother’s teats, a clump of them around her to hide what they had done. But she smelt the blood and was suspicious, and she struggled free: they flung the carcass downslope and she bellowed, her whitened eyes on that limp arc, and the yak cow blundered away after her child.

Raw milk and fresh blood, swirled together in a pail, and the stick insect first dipped a ladle and swallowed. Others followed him. One by one the cultists crouched and partook of this filthy drink.

Duz almost heaved up her belly of fermented milk. The smell alone made her queasy.

And the smell took her back, took her back to Ominan, though the last shaman’s ceremony she witnessed must be fifteen years ago. Raw milk, fresh blood, was the concoction a community gave its shaman, because it was spirits’ food, an anti-food a human stomach turned to think of. At Ominan people fed the shaman laughing, for he was not quite human, he was one too with the spirits, he belonged on both levels of existence. People prepared a pail for him with exaggerated displays of disgust, and teased him with the treat, for in his trance he was the victim of a more-than-human hunger, a crazed desire for this strange sustenance, and when they let him at it he lapped and splashed, his head right in the pail, the picture of a wolf deranged with thirst.

Nobody drinks an animal’s milk from the teat, and blood you put in sausages or soup. People cook.

What Rough Beast?

Among the yak nomads, rowdy, restless young have thrown themselves into a cult of were-beasts ridden by unknown spirits, and they stalk Goatskin.

They feel evil: evil by the lights of the intruder Temple, or by the banned old beliefs? And the shaman Goatskin searches for – a sad old man who set off on a quest his people call insane – what beast does he impossibly grapple?

In the starry high meadows, what inhabits the night? Whose evil?

What Rough Beast?, my second Goatskin novella (each a standalone), is being crowdfunded as one of four novellas from Brackenbury Books. Find us on Backerkit September 9-30. Here’s the link — do click and give us a look, and I hope support.

New Edge Sword & Sorcery Novellas 2025

The excerpt above is from early on in the story; you can hear it in situ as publisher Oliver Brackenbury reads the first couple of chapters.

Meanwhile I have an interview out at Black Gate, part of S E Lindberg’s series on Art & Beauty in Weird Fantasy. This was right up my alley, and a perfect excuse to ramble about my Decadent influences in both Goatskin novellas, Waste Flowers and What Rough Beast? Beauty, the stranger places one can find it, has always been a fascination of mine, and likely to be a presence in whatever I write.

Black Gate interview

June 17, 2025

Waste Flowers: sources and influences

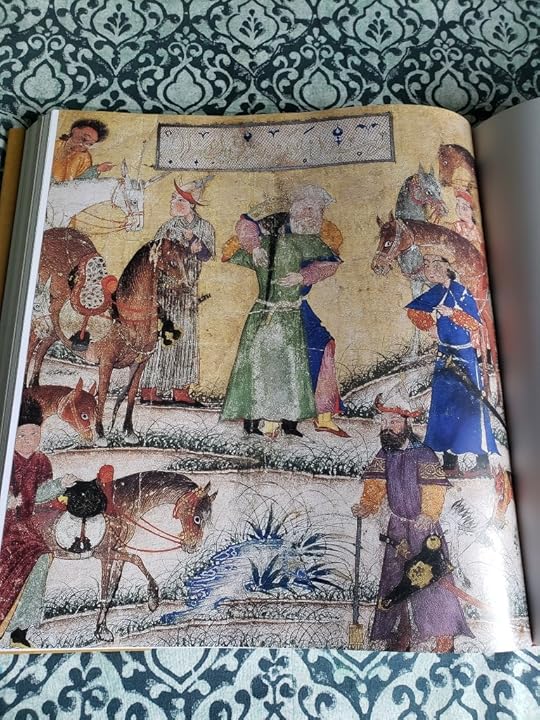

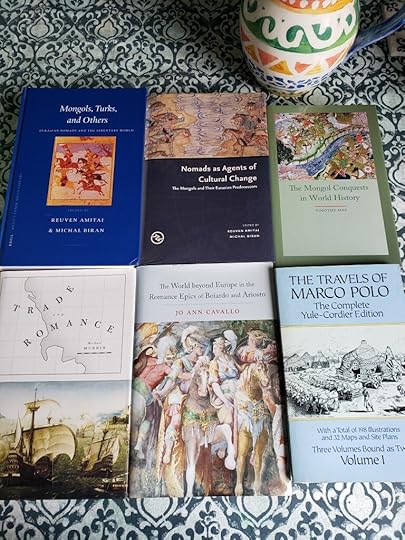

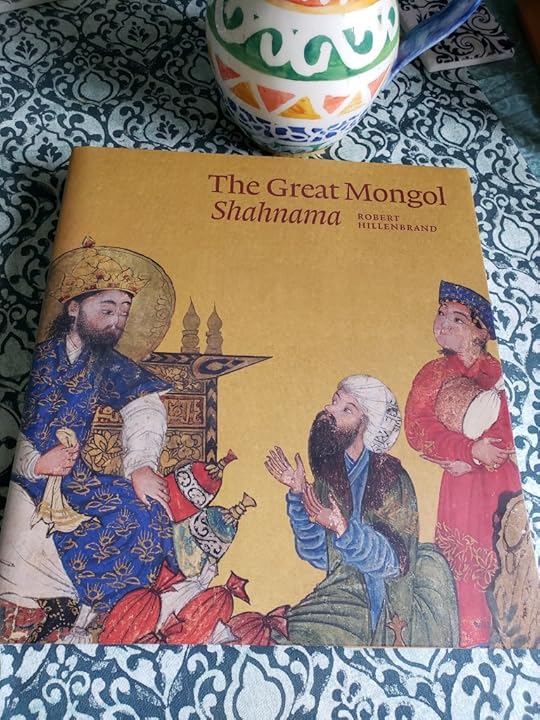

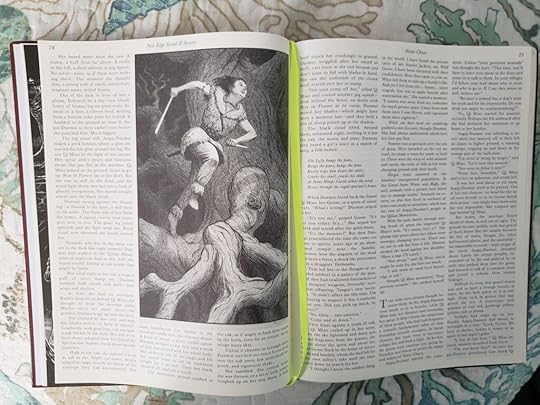

photo by Carl Ellis (@carlc75.bsky.social)

Here’s a smatter of sources and influences for my novella Waste Flowers, published in May as half of Double-Edged Sword & Sorcery.

1927, before the roads were too-travelled. On the brink of railways and the forgetting of journeys by camel. Owen Lattimore is a great writer, say what else you like, and I have stolen from him certain ethics and habits of camel men — over a large gap of time from Sogdian Traders: A History by Étienne de la Vaissière, but one does what one can to flesh out the sparse medieval sources.

Earlier travel. Go as early as you can with your travel accounts, and grasp over the space between French priests sent to spy on khans in the thirteenth century, and French priests out to wander in the nineteenth. Huc and Gabet have given me oddments from songs to animal behaviour: rich, lively, less rude than other old travels about Mongols and their way of life.

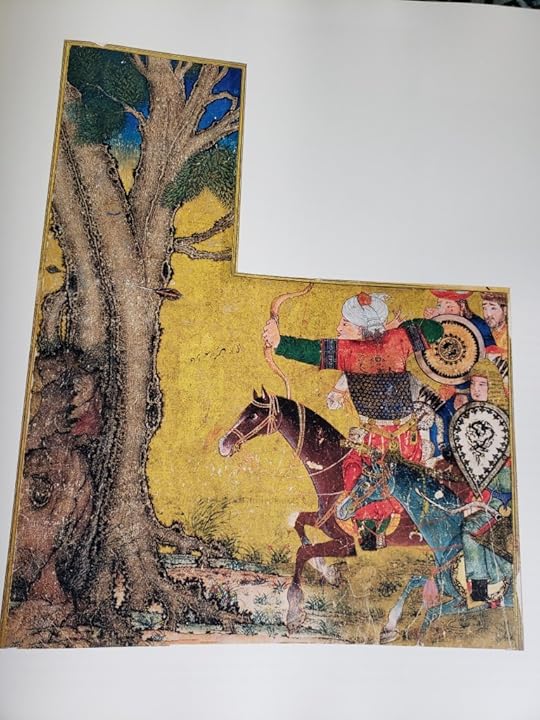

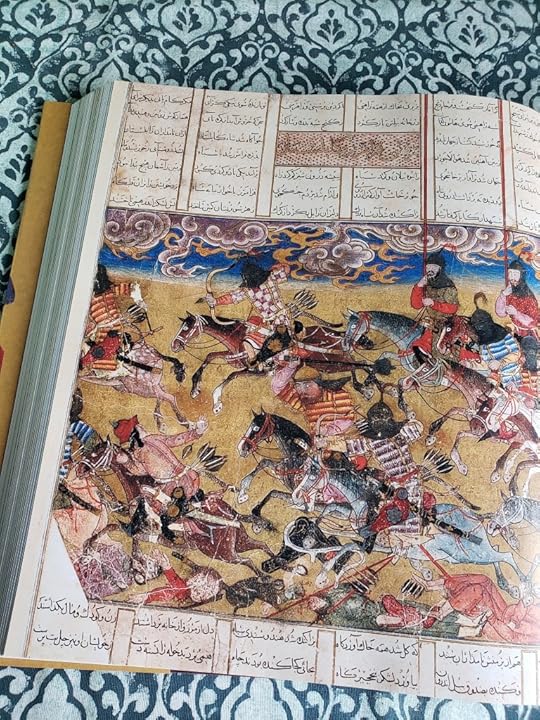

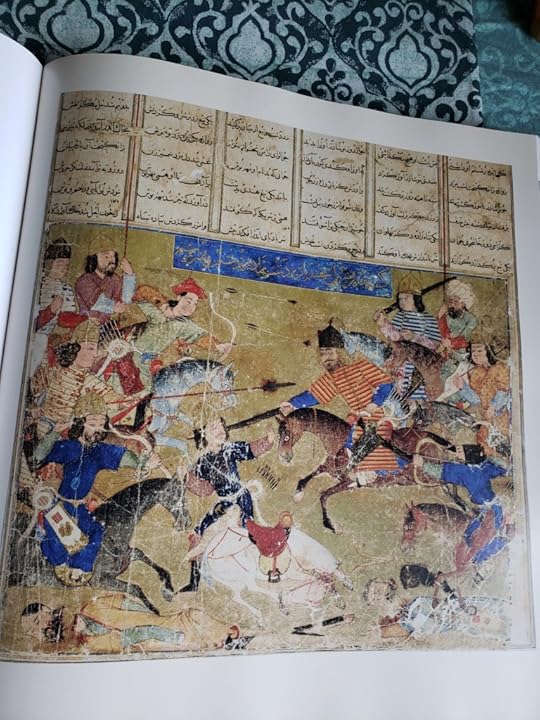

A great book for background on foreigners and reception of the foreign in Tang, but the photo is a stand-in for a more particular source: my most-consulted unpublished thesis (MA), Lee Chamney’s ‘The An Shi Rebellion and Rejection of the Other in Tang China’. I find this fascinating on an interaction of poetry and politics. ‘Just as the genre of frontier poetry briefed officials on what to expect at the frontier, it also briefed Xuanzong on how to understand the wars he commanded.’ How poetry shaped politics and not the other way around. I think the researcher writes SFF now.

Tang China’s ‘anti-foreign turn’ runs through my story. Nimgart’s little disquisition on how frontier poetry cemented the Walls, owes entirely to Lee Chamney.

Now we come to the people-eaters.

When my bandits sit around and discuss the end of aristocracy in Tang, and attribute it to the sheer destruction caused by That Terrible Bandit, they make the argument of this book.

For a quote on Huang Chao’s use of civilians as rations, and other incidents of people-eating, see my old post ‘They Eat People in the City’: three anecdotes.

These are what I turned to in preparation: old influences of mine that I felt the need to revisit, to stoke a mood.

Beauty and evil entwined in mine, so I went to Baudelaire. A website devoted to his Flowers of Evil gives you several English translations. This time around, I liked his Litany to Satan the most.

I was to write criminals, so I go to Jean Genet — again, for perverse beauty. My criminals always and indelibly owe to Dostoyevsky, but I think I talked about him in interviews (you can find more, much more, in the interviews I did when our crowdfund was on: collected here).

In the end, these two named my novella: between Flowers of Evil and Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers, I went with the title Waste Flowers.

February 2, 2025

Grendel poem ‘Scapegoat’

Meghan Purvis, my #1 translation

My poem on Grendel, ‘Scapegoat’, has been published at Heroic Fantasy Quarterly.

As always, I urge people to read a poem aloud, with the mouth and the ears.

My inspiration was Algernon Swinburne’s ‘The Leper’, which I read (aloud) over and over to steep myself in its ballad rhythms, somewhat halt, its stark simplicity of words, somewhat awkward, its rough rhymes. Swinburne does a medievalist diction here and I think he found in medieval poetry a choppy quality, rough edges that in medievalism (imitation of the medieval) are a part of the charm. In his poem these aid the rude simplicity, the stumblingly sincere narrator’s voice.

‘The Leper’ got called ‘one of Swinburne’s shockers’. It describes a lady being eaten away by leprosy, rejected in disgust by her erstwhile admirers, cared for in squalid circumstances by a lowly man, always devoted to her, whom she once despised. There is suggested necrophilia and the scenario sets up a questioning of God.

Sometimes Swinburne ‘shockers’ are side-on and deliberately lurid, and are lesser works for that. Other times, they stretch empathy into its most radical positions. The perverse story of ‘The Leper’ is told straight, with a sincerity as simple as that ballad metre, and goes straight for the heart. It has things in common with my primary Swinburne poem ‘Anactoria’, which again questions God through a story of obsessive love and sadomasochism (Sappho’s for a girl who abandoned her), not a ballad but first-person and voicy, and out to do much more than shock.

I didn’t think I’d got much of that choppy sincerity to the verse, but on a pre-publication re-read, I do catch that kind of simplicity I aimed for when I set out to write a poem like ‘The Leper’. And I hope I tweak your heart on behalf of the sentimental monstrous, like Swinburne. Here’s a link to his poem.

Grendel has been my ultimate outsider for decades and I love him dearly. One of my early abandoned novels was titled Grendel in Hell, and had steampunk demons before steampunk was a thing, because the Devil stood for artificiality as Against Nature (to invoke the title of a Decadent classic by Huysmans). I snipped off a little piece of this material and got it into ergot.

And because my Beowulf translation, abandoned after 1000 lines, won’t see the light of day, have a primer/reminder of the original, the section pertinent to ‘Scapegoat’. Starting at first mention of Grendel:

The times that dawned meant only torment for one,

An estranged spirit, weary with his years spent in the waste –

Each day to hear echo the enchantment in the court.

There the harp played and the bard’s lay leapt up.

An orator, taught in the lore of the origin of life,

Talked on the Omnipotent, on the cosmos his creation:

The symmetry of earth encircled by the seas,

The proud march of sun and moon, lamps for our path,

Embroidery of boughs and leaves, living, burgeoning;

Life too quickened in the creatures that stir, each in its kind.

So the king’s company lived in celebration, blessed,

Until one inflicted his envy upon them, an unholy fiend.

This grim figure they knew as ugly Grendel,

Rumoured to wander the wild moors and marshes,

Frightening men from the frontiers of the fens.

An age he had guarded the monsters’ home ground –

Such was his dark fate since God had forsaken

The tribe of Cain’s kindred until the end of time,

Condemned in him, because he killed his brother.

That feud did not profit him; far was he pursued

By the great judge for his guilt, a fugitive from men.

Owed to his ancestry are the unnatural things –

Ogres and elves and ghouls from the dead,

Even the giants who fought against God

In an epoch of havoc… but He had his own back.

One night he intruded, intrigued, into the house,

Hushed now the Ring Danes had drunk enough of wine.

Inside he found them, and saw how those fighting elite

Slept after the feast, forgot the sad state, the dark end of flesh.

The damned one, grim and greedy, at once was urged on,

Ferocious, in frenzy, and seized thirty lives as they slept –

Then escaped, ecstatic with his catch, back the way he came,

Towards his solitudes to enjoy his spoil of slain.

Then, in the half light from under the horizon,

The danger of Grendel dawned upon men.

After the laughter uplifted yesterday

Screams and cries clamoured to the morning sky.

The king, known for honour, the old noble,

Once they had searched and discovered the tracks

Of the cursed demon, sat downcast

As his strong heart strove under his heavy grief.

Too harsh that trouble, too hard and tenacious.

No pause – the next night unleashed another onslaught,

Double the flagrant murder. No doubts he felt

About his drastic feud; he was lost too deep in it.

His gist was unambiguous, and most of Hrothgar’s guests

Disbanded to secure beds, separate from the court,

Where was no grudge against them, about the outer grounds

Or among the animals, since a devil had joined the army.

So he usurped the house from the use of men,

At war against right, one against the world.

The ideal court was empty, abandoned to the enemy.

It went on a great while; throughout twelve winters

Scyld’s childrens’ chief suffered his inflictions,

Utmost sorrow, the gamut of grief.

The tale of it travelled, heard by the tribes

In elegies for Hrothgar under Grendel’s siege –

Hostilities sustained, season in, season out,

A vendetta without end, and vengeance for no fault.

Not for him arbitration, or atonement, or a truce;

No family saw a fee for his felonies,

No victim had his due; futile to demand

Handsome satisfaction at the slayer’s hands.

The uncanny creature only hunted them like quarry,

A shadow of death stalking their footsteps in the dark,

Ambushing in the unnatural night on the misty moors;

The haunts of hell’s initiates are a mystery.

So the enemy of men sought their harm and ignominy

And up against them on his own, overawed them.

He dwelt in Heorot the jewelled while the light was out –

With no grace to know the gift throne, nor to kneel

In loving kindness at that seat in the Creator’s sight.

Heavy was his punishment, crushing the heart

Of Scyld’s childrens’ king and comrade.

His under-chiefs sat often in conclave, to consult

On a strategy, what strength of spirit might attempt

In defence, what face the fear of his rush.

Some among them sacrificed at pagan shrines,

Worshipped stones, supplicated in prayer

The slayer of souls to help, to have pity on the people.

Such was their habit, the only hope of heathens;

Their hearts’ instinct turned to hell, ignorant of heaven.

The one God was unknown to them, the wonderworker,

Our sanctuary; they had not learnt His sacraments.

Lost is his case who in his soul’s last crisis

Must feel himself fall into the arms of the inferno.

Found is his desire who after his death day

May follow his weary heart into our father’s arms.

So Scyld’s great-grandson in the sorrows of his times

Seethed with suffering that had no cease;

Nor against his anguish the sagacious hero

Saw a promise of salvation. Too harsh,

Hard and tenacious, this trouble upon his people,

Worst disaster, urgent need, desperation in the night.

[ll. 86-194]

All right, that’s up until Beowulf’s advent. I wrote a poem from Beowulf’s perspective too: you can read ‘A Monster to Fight Monsters’ in this post.

November 30, 2024

Black Death on the Black Sea

This is a rescues post: a Twitter thread salvaged as Twitter goes under, an essay I meant to extend. Better here, as is, than hidden in my files.

I remain concerned about how new work on the origins of the Black Death is going to set medievalists and other people talking about Mongol history. We know what happens when diseases are associated with foreigners. But, as with the turn towards the Global Middle Ages, Mongol history can also flower under new attention.

Incident at Caffa: Mongols lobbing plague dead into the enemy? Not likelyFirst, my Twitter thread on the incident at Caffa. Context — the murder of a Mongol:

The most serious episode, which ushered in a long period of hostilities between Genoese and Venetians on one side and Janibeg Khan (r. 1342-57) on the other, occurred in 1343 as a consequence of the Venetian refusal to deliver to Mongol authorities a Venetian nobleman, Andreolo Civran, who had been found guilty of having ambushed and slain a Mongol with whom he had previously had an altercation. The subsequent turmoil all but wiped out the Italian presence on the Black Sea, forcing the “Franks” (that is, the Italians) to flee Tana to save their lives and seek refuge in Caffa. Caffa, however, was attacked, besieged, and nearly taken by the army of Janibeg. Th is episode is famously known for the connection between the Mongols’ bombardment of Caffa with infected corpses and animal carcasses and the spread of the Black Death that ravaged Europe.

— Di Cosmo, Nicola, ‘Black Sea emporia and the Mongol Empire: A reassessment of the Pax Mongolica’

[searches Twitter for ‘Mongols’ + ‘Black Death’] We so need to dislodge the factoid ‘first recorded use of biological warfare’ from people’s heads. The one source is a complaint full of rhetorical flourish from a stay-at-home lawyer in Italy. Consider his ignorance and prejudice.

#

We need to be source-critical and not just re-tell a grisly tale for the same reason Gabriele de’ Mussis told it: for the shock-horror, to appease readers’ cravings and transmit our own texts on the back of a grisly story. We need to do lit-crit on de Mussis in our history books.

#

But instead, historians themselves (Mongolists not excluded) revel in the war-and-gore tale and only want to tell it again to the kids.

#

It matters because ‘first recorded use of biological warfare’ is lodged in heads, all over the internet, accepted in reputable books, and one of the basic factoids people ‘learn’ [in quote marks] about Mongol history. While it doesn’t stand up to any source criticism at all…

#

Even May (found in agreement with Dr Green’s new work on marmots, Issyk Kul origins & plague as a factor in the collapse of Mongol states) — in an otherwise excellent chapter on ‘Mongols and Plague’, licks his lips at this story and dives in. He calculates body splatter range.

#

Instead of interrogating Gabriele de’ Mussis and his prose-poem of blame for the plague.

#

Such sensationalism is *exactly what we have to avoid* now that Dr Green’s stellar work has made Mongols and the Black Death an inevitably big talking-point and, once again, a main way into Mongol history. We don’t want a ‘Mongol plague’ language now — after de Mussis’ Tartars.

#

I can see the talking-points about Mongols eating rodents. Wet markets, anyone?

#

So let’s at least avoid historians’ disgust when discussing Mongol eating habits. It’s easy to express disgust in that not-so-neutral, not-so-measured historians’ style. We have to try not to replicate attitudes of 13thC European travelers on rat-eating, even while we quote them.

#

Like, it’s easy to write without disgust or a laugh on what historical Mongols ate and why. But writers seem to find it easy to imagine eating marmot or rats, screw up their faces and smirk in collusion with the reader. Don’t do that? Write straight-faced. Imagine historically.

#

Download Dr Monica H. Green’s The Four Plagues. For the moment, still read Timothy May on The Mongols and Plague, which stands up well enough after Dr Green (but ask questions — always).

#

Dr Barker lays our meme to rest. A reconstruction of Caffa from Byzantine, Genoese, Venetian, Mamluk residents and travelers. ‘Laying the Corpses to Rest: Grain, Embargoes, and Yersinia pestis in the Black Sea, 1346–48’ Hannah Barker, Speculum 96.1 Jan 2021

#

Yesterday-today have read Dr Barker. Along with Dr Green’s intervention, it’s conclusive. Ends: ‘Plague’s movement across the Black Sea was certainly not a matter of bioterrorism during the siege of Caffa. Instead, it was an unintended consequence of peace.’

#

[end thread]

A few years previously I’d written this essay on how plague destroyed European-Mongol contacts. It’s a sad essay. I’ll introduce it with this quote:

To the few who could perceive it, the Mongols’ arrival had appeared in the thirteenth century as a comet that indicated the way to a brighter future of global trade and unfettered exchange. They had demonstrated that it was possible to achieve a more integrated world… — Di Cosmo, Nicola, ‘Black Sea emporia and the Mongol Empire: A reassessment of the Pax Mongolica’.

What was lost to plague? or, a lament for the Pax Mongolica and its other, forgotten Marco Polos

What was lost to plague? or, a lament for the Pax Mongolica and its other, forgotten Marco PolosThe Black Death of 1347-50 began on the Black Sea, for Europe. Before the great pestilence, Genoese were the most heavily involved of Europeans with the Mongol world beyond the Black Sea. This essay looks at Italian contacts with farther Asia, and the effects of the plague on these contacts. Mongol states suffered in the plague and lost their ability to facilitate trade; for Italian merchants, who had travelled with unprecedented freedom through this world, farther Asia was again cut off. Cultural interchanges were lost, and even knowledge of them was often lost to sight in a post-plague world, except as preserved in popular romances. Italian art also testifies to an engagement with farther Asia in the later thirteenth and the early fourteenth centuries, before the plague. Thus we need to turn to paintings and romance, in order to see the before and after, and assess the effects of the plague. This very trade between the Italian merchant republics and the Mongols was understood to be the agent of transmission of the plague to Europe; the Genoese feature in chronicles as shipping plague from port to port. It is a sad end to a story of exchange and openness between Asia and Europe in the medieval age.

For a century before the great plague of 1347-50, the Pax Mongolica was in effect. The whole Mongol world was open for trade, into farther Asia – that is, beyond what touches the Mediterranean and Black Seas. Previous states in these areas, running on principles of settled peoples, had not allowed foreigners to travel freely in their interiors, and they had their own merchants whose commercial interests to protect. Not so Mongols, who took every means possible to attract foreign merchants and facilitated their travel through the vast spaces in which they had demolished borders. The four khans’ territories were loose-knit; the Ilkhans in Iran and the khans of the Golden Horde above the Black and Caspian Seas were political rivals, at times at war. Nevertheless, neither government let this disrupt the transit trade, or punished each other through trade access as is usual for non-nomad states. Trade was of the first concern to Mongols. Janet Abu-Lughod has seen in this century, A.D. 1250-1350, an emergent ‘world system’ of trade connections; Roxann Prazniak, who studies Italian-Asian contacts, talks of a ‘Mongol world century’ with these same dates. It ends around the date of the Black Death.

Italians moved confidently in the Mongol world. They negotiated with Mongol governments, made treaties, stood up for their rights, quarrelled with Mongols and entered into armed conflict. They are found as individuals in service at the court of the Ilkhans; in a Genoese Quarter in the Ilkhans’ capital Tabriz; a brother and a sister, guessed to be Genoese, have tombstones in the port city of Zayton (Quanzhou) in China, where lived a Latin community. Genoa had won a struggle with Venice for the lion’s share of trading opportunities in the Mongol world. Its operations on the Black Sea can be described as a partnership or a symbiosis with the Golden Horde Mongols – the ‘closest recorded working relationship’ between a European and an Asian state in the medieval age. Unfortunately, the far-travelled Genoese left few records of their activities, in part due to commercial secrecy and a preference for oral information. None of these exploratory merchants and adventurers met the accidents that led the Venetian Marco Polo to divulge his experiences. Other reasons for the quiet of the records have been adduced: vital to Genoa’s trade arrangements between the Golden Horde and Egypt was the shipping of slaves to be mamlukes from one to the other. This service, a necessity for the Dawla al-Turkiyya (‘The State of the Turks’) in Egypt and its Mongol ally, was not a matter for the European go-betweens to boast of; if merchants chose to major in this trade, they did not keep the accounts they did for other merchandise.

The plague coincided with and in part caused the close-down of trade with farther Asia and the end of the Pax Mongolica. The Golden Horde had been over a diplomatic barrel; the khans in Saray had often displayed a reluctance to export their own population, but strategy required they satisfy this unique need of Egypt for new slave soldiers from the steppe, in order to keep Egypt as an ally against their rival Ilkhans. Plague depopulated the Golden Horde and this sacrifice of people became unconscionable for the Saray khans. Plague, at the same time, helped the descent of the Ilkhans’ state into chaos, which ended the diplomatic triangle, and the Golden Horde’s attitude towards its Genoese trading partners on the Black Sea underwent a change. It did not have to do business with them in the old ways, and resentments over the slave trade became evident.

As Nicola di Cosmo observes, the Genoese on the Black Sea in fact had a strengthened hand against a debilitated Golden Horde after the plague, and their colony cities gained in sovereign rights. However, farther Asia was cut off, as Mongol states in Iran (1340s onwards) and China (the two decades up to 1368) collapsed – both, it has been argued, victims of the plague. There is a distinction to be made between Genoa’s government and its private merchants: the government had never pursued opportunities to extend its activities east; even Mongol offers for diplomatic exchange were not taken up. The Genoese government was content to exploit the immediate Black Sea surrounds, that had been familiar European places for trade and slave acquisition since the Greek colonies in ancient times. Ventures into farther Asia had been of private initiative. Privately led and funded enterprises were a mark of Genoese ways of doing business; Benjamin Kedar contrasts the traits ascribed to Genoese and Venetians in the contemporary view, with the Genoese individualistic and resistant to state control. Indeed, Genoese resident on the Black Sea were known to disobey the home government when its orders interfered with trade. These differences can help explain Genoa’s deeper engagement with Asia. It was individual exploits, self-organised, that struck out beyond the purview of the Genoese state. After the plague on the Black Sea, the more conservative trade interests of Genoa’s government held sway: just as in post-plague Europe, trade became localised and distance trade suffered. Di Cosmo lists the retained merchandise from local sources: fish, caviar, timber, hides – not the conspicuous ‘Tartar cloth’, or nasij in the Mongol world, gold-embroidered brocades. In Kedar’s study of Genoese and Venetian merchant mentalities in the fourteenth-century depression, the evidence indicates retrenchment, safe bets, low aims. Steven Epstein writes similarly in his history of medieval Genoa: he farewells ‘the earlier, heroic age of merchant entrepreneurs’ for a risk-averse climate after the plague: ‘the Genoese do seem collectively to have lost their intrepid spirit… nothing would be heard of China for a long time.’

As Nicola di Cosmo observes, the Genoese on the Black Sea in fact had a strengthened hand against a debilitated Golden Horde after the plague, and their colony cities gained in sovereign rights. However, farther Asia was cut off, as Mongol states in Iran (1340s onwards) and China (the two decades up to 1368) collapsed – both, it has been argued, victims of the plague. There is a distinction to be made between Genoa’s government and its private merchants: the government had never pursued opportunities to extend its activities east; even Mongol offers for diplomatic exchange were not taken up. The Genoese government was content to exploit the immediate Black Sea surrounds, that had been familiar European places for trade and slave acquisition since the Greek colonies in ancient times. Ventures into farther Asia had been of private initiative. Privately led and funded enterprises were a mark of Genoese ways of doing business; Benjamin Kedar contrasts the traits ascribed to Genoese and Venetians in the contemporary view, with the Genoese individualistic and resistant to state control. Indeed, Genoese resident on the Black Sea were known to disobey the home government when its orders interfered with trade. These differences can help explain Genoa’s deeper engagement with Asia. It was individual exploits, self-organised, that struck out beyond the purview of the Genoese state. After the plague on the Black Sea, the more conservative trade interests of Genoa’s government held sway: just as in post-plague Europe, trade became localised and distance trade suffered. Di Cosmo lists the retained merchandise from local sources: fish, caviar, timber, hides – not the conspicuous ‘Tartar cloth’, or nasij in the Mongol world, gold-embroidered brocades. In Kedar’s study of Genoese and Venetian merchant mentalities in the fourteenth-century depression, the evidence indicates retrenchment, safe bets, low aims. Steven Epstein writes similarly in his history of medieval Genoa: he farewells ‘the earlier, heroic age of merchant entrepreneurs’ for a risk-averse climate after the plague: ‘the Genoese do seem collectively to have lost their intrepid spirit… nothing would be heard of China for a long time.’

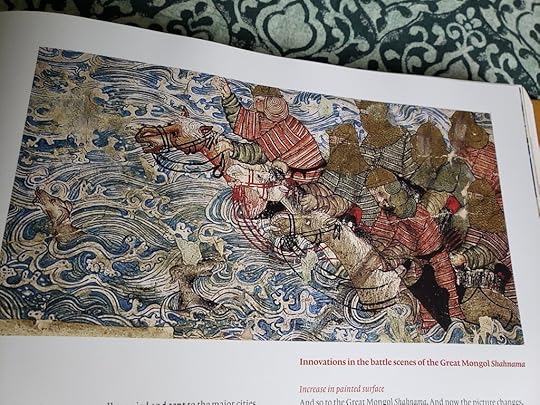

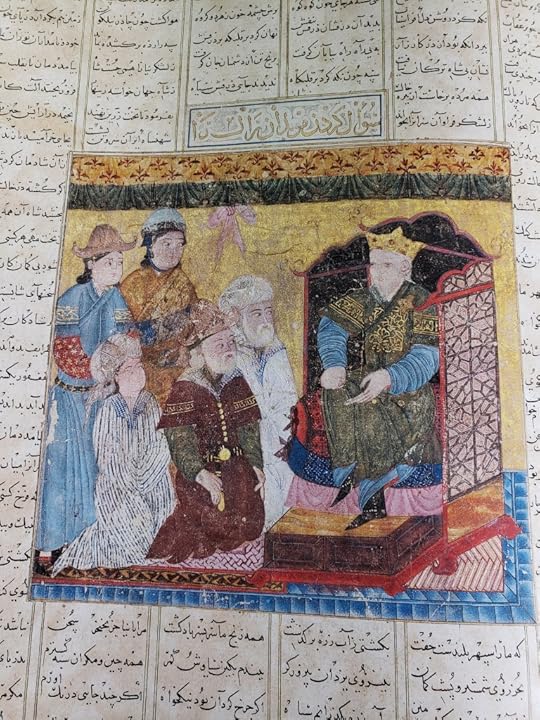

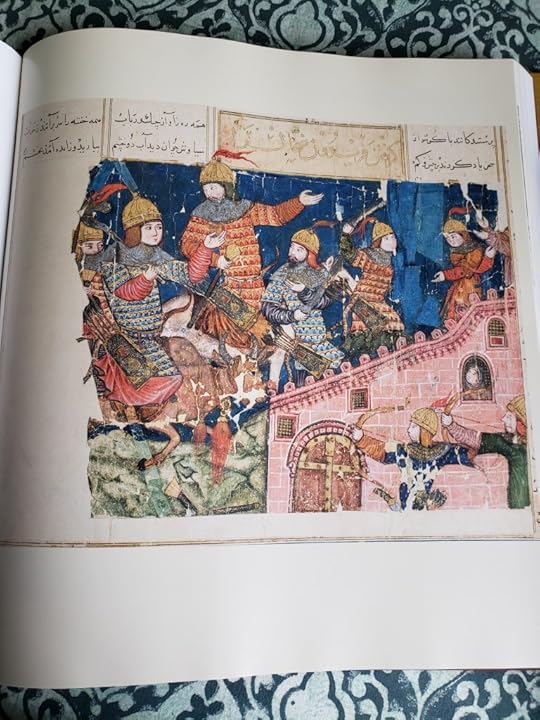

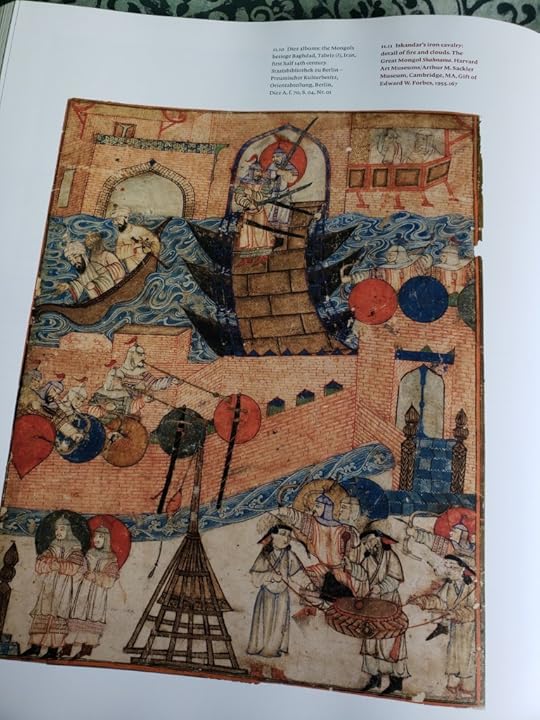

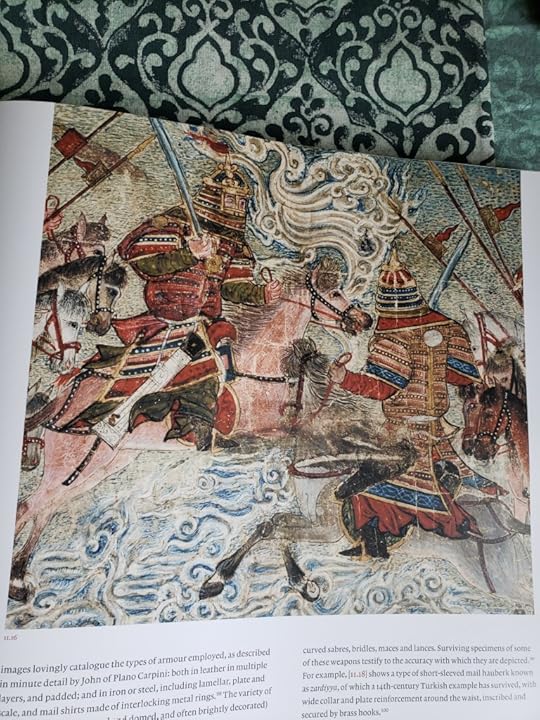

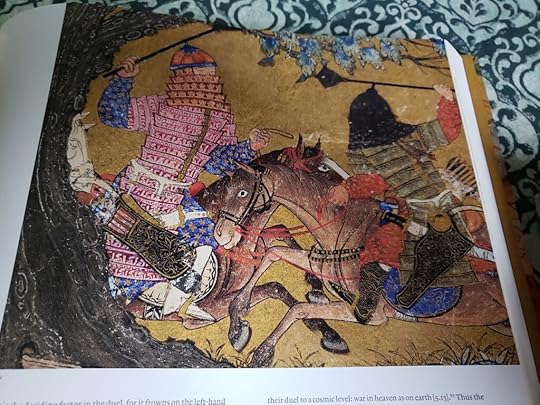

To see what was lost in the post-plague world, we need a view of the world before the plague: so Kedar reasons when he sets out to assess the fourteenth-century depression. This is true of Italy’s engagement with the east. With the interruption of the plague and the closure of farther Asia, knowledge too went into retrenchment, and the engagement of Italy with Asia was lost sight of – even into the scholarship today. Art history is one road to rediscovery of how close these worlds once were. Fourteenth-century Italian painting has been plumbed for evidence of Asian influence. Most strikingly, Roxann Prazniak has detected in the paintings of Ambrogio Lorenzetti of Siena, on the eve of the Black Death in the 1340s, a direct intimation of art styles in Tabriz, the ‘world historical’ city of the Ilkhans, as well as an intelligent commentary on Mongol conditions in one work set at a Central Asian court. Meanwhile, art historians of the period of Mongol rule in Iran trace Italian influences there. Prazniak’s ongoing investigations are at the forefront of Italian-Mongol cultural links.

After the plague, there is also reminiscence in romance. That ‘heroic age’ of mercantile Genoese before the post-plague depression is captured in romance, which in the thirteenth century took a turn to Asia, as known through merchant travellers. Michael Murrin, in his book Trade and Romance, argues that the new Asian settings, first inspired by Marco Polo, continued to be fuelled by the experiences, the real adventures – and the interests – of non-aristocratic travellers for commerce, even though the heroes remained knights. Chaucer set his Squire’s Tale in Saray, capital of the Golden Horde. This tale has proven to be well-informed about the Mongol world, with its most extravagant fantasies anchored in actual events, historical stories, material items. Murrin posits that Chaucer heard tales of the Golden Horde from Genoese merchants, in the later decades of the fourteenth century. Inexplicable, otherwise, is his idealisation of Chinggis Khan (Cambyuskan) as an exemplary monarch – a portrait matched elsewhere only by Marco Polo’s eulogy on Chinggis. Marco Polo took a Mongol view of things and may scarcely have felt European. Residents among the Mongols were open to this foreign world: the Squire’s Tale, written on Genoese intelligence, stands as proof. It contrasts with a view from home: the doges of Genoa and Venice, in correspondence with each other in 1345, ‘vent their real feelings’ on the Tartars – insulting and estranged. In a later reminiscence, from 1495, Matteo Maria Boiardo’s Italianised Roland makes friends with a Tartar king whose characterisation also invokes (good) qualities told of Chinggis Khan. Boiardo’s open Asia is more that of the Pax Mongolica than of his present-day; while the Squire’s Tale envisages a golden age in the Golden Horde. These are the memories of merchants, preserved in romance; an evidence not to be neglected.

After the plague, there is also reminiscence in romance. That ‘heroic age’ of mercantile Genoese before the post-plague depression is captured in romance, which in the thirteenth century took a turn to Asia, as known through merchant travellers. Michael Murrin, in his book Trade and Romance, argues that the new Asian settings, first inspired by Marco Polo, continued to be fuelled by the experiences, the real adventures – and the interests – of non-aristocratic travellers for commerce, even though the heroes remained knights. Chaucer set his Squire’s Tale in Saray, capital of the Golden Horde. This tale has proven to be well-informed about the Mongol world, with its most extravagant fantasies anchored in actual events, historical stories, material items. Murrin posits that Chaucer heard tales of the Golden Horde from Genoese merchants, in the later decades of the fourteenth century. Inexplicable, otherwise, is his idealisation of Chinggis Khan (Cambyuskan) as an exemplary monarch – a portrait matched elsewhere only by Marco Polo’s eulogy on Chinggis. Marco Polo took a Mongol view of things and may scarcely have felt European. Residents among the Mongols were open to this foreign world: the Squire’s Tale, written on Genoese intelligence, stands as proof. It contrasts with a view from home: the doges of Genoa and Venice, in correspondence with each other in 1345, ‘vent their real feelings’ on the Tartars – insulting and estranged. In a later reminiscence, from 1495, Matteo Maria Boiardo’s Italianised Roland makes friends with a Tartar king whose characterisation also invokes (good) qualities told of Chinggis Khan. Boiardo’s open Asia is more that of the Pax Mongolica than of his present-day; while the Squire’s Tale envisages a golden age in the Golden Horde. These are the memories of merchants, preserved in romance; an evidence not to be neglected.

Within Europe, the picture is quite different. The alliterative Morte Arthure, with a date close to the Squire’s Tale at the end of the fourteenth century, has King Arthur slay a baby-spitting giant from Genoa. The Genoese in Europe lived in disrepute, very often – this is the theme of David Wallace’s study of Genoa as a place in the imagination, then and now. Now, in the historical imagination: Abu-Lughod notes the ‘inequal treatment in the literature’ of Venice and Genoa, when these were equivalent in importance in the thirteenth century. Genoa’s connections with the little-understood Tartars, with the slave trade, with ambivalently-seen wealth from the east, must have fed into this unsavoury image. Then, they were blamed for shipping the plague. Its very transmission to Europeans was located at Genoese Caffa on the Black Sea, besieged by Tartars in a quarrel over a murder. The tale of Gabriele de’ Mussis in his Historia de Morbo need not be taken at face value: both shamanists and Muslims had ways to dispose of dead, which didn’t include lobbing them at the enemy; in the khan’s plague-stricken army despair might have set in, over religious concerns. Whether true or not, this is the tale that went around, with the declamation of de’ Mussis: ‘Speak, Genoa, of what you have done.’ Next, Genoese ships feature in chronicles around the coasts of Europe as bringers of the terrible disease. ‘Tartars’, ‘Caffa’, ‘ships of Genoa’ recur as Europe records its history of transmission of the plague in the year 1347. Of the course of the plague in Genoa itself, Epstein finds absolutely no local records. But Genoese, and their eastwards trade with Tartars, acquired the ill-fame of afflicting Europe with the great pestilence known as the Black Death. There seems to be a split view, of Genoese as of Tartars: a golden age, a Pax Mongolica, remembered by the merchants involved; and the scapegoating of these Europeans who had truck and traffic with such a foreign world – before the plague.

Within Europe, the picture is quite different. The alliterative Morte Arthure, with a date close to the Squire’s Tale at the end of the fourteenth century, has King Arthur slay a baby-spitting giant from Genoa. The Genoese in Europe lived in disrepute, very often – this is the theme of David Wallace’s study of Genoa as a place in the imagination, then and now. Now, in the historical imagination: Abu-Lughod notes the ‘inequal treatment in the literature’ of Venice and Genoa, when these were equivalent in importance in the thirteenth century. Genoa’s connections with the little-understood Tartars, with the slave trade, with ambivalently-seen wealth from the east, must have fed into this unsavoury image. Then, they were blamed for shipping the plague. Its very transmission to Europeans was located at Genoese Caffa on the Black Sea, besieged by Tartars in a quarrel over a murder. The tale of Gabriele de’ Mussis in his Historia de Morbo need not be taken at face value: both shamanists and Muslims had ways to dispose of dead, which didn’t include lobbing them at the enemy; in the khan’s plague-stricken army despair might have set in, over religious concerns. Whether true or not, this is the tale that went around, with the declamation of de’ Mussis: ‘Speak, Genoa, of what you have done.’ Next, Genoese ships feature in chronicles around the coasts of Europe as bringers of the terrible disease. ‘Tartars’, ‘Caffa’, ‘ships of Genoa’ recur as Europe records its history of transmission of the plague in the year 1347. Of the course of the plague in Genoa itself, Epstein finds absolutely no local records. But Genoese, and their eastwards trade with Tartars, acquired the ill-fame of afflicting Europe with the great pestilence known as the Black Death. There seems to be a split view, of Genoese as of Tartars: a golden age, a Pax Mongolica, remembered by the merchants involved; and the scapegoating of these Europeans who had truck and traffic with such a foreign world – before the plague.

The Black Death, from a European perspective, began on the Black Sea, an unfortunate contact between the adventurous Genoese merchants and the Mongol world that welcomed them. It must be seen against the contacts that existed in a world before the plague, where Italians travelled into Mongol Iran and Mongol China. They left few records – Marco Polo is a stand-out – and the evidence of them often lies in cultural exchanges, in Italian art influenced by art styles in Tabriz, in romances that know the Mongol world through the tales of these travellers. The great pestilence of 1346-50 interfered with trade, helped reduce the Mongol states to chaos, and left affairs on the Black Sea to the more conservative Genoese government, instead of private, exploratory ventures farther into Asia. The trade itself, the connection of Genoa and the Mongols, was seen as the agent of this catastrophic disease. The closest cooperation between Europe and Asia, in the medieval period, was over.

The Black Death, from a European perspective, began on the Black Sea, an unfortunate contact between the adventurous Genoese merchants and the Mongol world that welcomed them. It must be seen against the contacts that existed in a world before the plague, where Italians travelled into Mongol Iran and Mongol China. They left few records – Marco Polo is a stand-out – and the evidence of them often lies in cultural exchanges, in Italian art influenced by art styles in Tabriz, in romances that know the Mongol world through the tales of these travellers. The great pestilence of 1346-50 interfered with trade, helped reduce the Mongol states to chaos, and left affairs on the Black Sea to the more conservative Genoese government, instead of private, exploratory ventures farther into Asia. The trade itself, the connection of Genoa and the Mongols, was seen as the agent of this catastrophic disease. The closest cooperation between Europe and Asia, in the medieval period, was over.

Further reading

My blog post Mongols and the Plague: mostly about Mongol understandings of disease and contagion.

My blog post Chaucer Goes to the Golden Horde: on the Squire’s Tale and its Mongol knowledge.

Roxann Prazniak, often mentioned in this essay, has since published a book about the interconnected Mongol world. Here’s my review for the Asian Review of Books.

My review of Jo Ann Cavallo’s The World Beyond Europe in the Romance Epics of Boiardo and Ariosto, where I get excited about meeting a sympathetic Mongol khan in Italian romance; and of Michael Murrin’s Trade and Romance, for when romance changed from the ‘Celtic fantastic’ to the ‘marvelous real’, whose tutelary spirit was Marco Polo.

Bibliography and footnotes

Abu-Lughod, Janet L., Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989.

Allsen, Thomas T., Commodity and Exchange in the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Blair, Sheila, ‘The Religious Art of the Ilkhanids’, in The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, eds. Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2002, pp. 104-33.

Braud, David, ‘The Slave Supply in Classical Greece’, in The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 1: The Ancient Mediterranean World, eds. Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp. 112-33.

Cavallo, Jo Ann, The World Beyond Europe in the Romance Epics of Boiardo and Ariosto, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2013.

Childs, Wendy, ‘Anglo-Italian Contacts in the Fourteenth Century’, in Chaucer and the Italian Trecento, ed. Piero Boitani, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1983, pp. 65-87.

Ciocîltan, Virgil, The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, trans. Samuel Willcocks, Leiden, Brill, 2012.

Di Cosmo, Nicola, ‘Black Sea emporia and the Mongol Empire: A reassessment of the Pax Mongolica’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, vol. 53, iss. 1-2, 2009, pp. 83-108.

Di Cosmo, Nicola, ‘Mongols and Merchants on the Black Sea Frontier in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Convergences and Conflicts’, in Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World, eds. Reuven Amitai and Michal Biran, Leiden, Brill, 2005, pp. 391-424.

Epstein, Steven A., Genoa and the Genoese, 958-1528, Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Epstein, Steven A., Purity Lost: Transgressing Boundaries in the Eastern Mediterranean, 1000-1400, Baltimore, The John Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Ho, Colleen, ‘Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century European-Mongol Relations’, History Compass, vol. 10, iss. 12, 2012, pp. 946-68.

Horrox, Rosemary, The Black Death, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1994.

Jordan, Carmel, ‘Soviet Archeology and the Setting of the Squire’s Tale’, The Chaucer Review, vol. 22, iss. 2, 1987, pp. 128-9.

Kedar, Benjamin Z., Merchants in Crisis: Genoese and Venetian Men of Affairs and the Fourteenth-Century Depression, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1976.

Korobeinikov, Dimitri, ‘A Broken Mirror: The Kipchak World in the Thirteenth Century’, in The Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars, and Cumans, ed. Florin Curta, Leiden, Brill, 2008.

Lach, Donald F., Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume 1: The Century of Discovery, Book One, Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press, 1965.

May, Timothy, The Mongol Conquests in World History, London, Reaktion, 2012.

McKee, Sally, ‘Domestic slavery in Renaissance Italy’, Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies, vol. 29, iss. 3, 2008, pp. 305-326.

Murrin, Michael, Trade and Romance, Chicago & London, University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Peleggi, Maurizio, ‘Shifting alterity: The Mongol in the visual and literary culture of the late Middle Ages’, The Medieval History Journal, vol. 4, iss. 1, 2001, pp. 16-33.

Piacentini, Valeria Fiorani, ‘The Golden Age of Genoa’s eastwards trade (13th-15th centuries)’, The Journal of Central Asian Studies, vol. 19, iss. 1, 2010, pp. 25-40.

Prazniak, Roxann, ‘Siena on the Silk Roads: Ambrogio Lorenzetti and the Mongol Global Century, 1250-1350’, Journal of World History, vol. 21, iss. 2, 2010, pp. 177-217.

Prazniak, Roxann, ‘Tabriz on the Silk Roads: Thirteenth-century Eurasian cultural connections’, Asian Review of World Histories, vol. 1, iss. 2, 2013, pp. 169-188.

Wallace, David, Premodern Places: Calais to Surinam, Chaucer to Aphra Behn, Malden MA, Blackwell, 2004.

Mongol attitudes to trade are well explained in Virgil Ciocîltan, The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, trans. Samuel Willcocks, Leiden, 2012, pp. 1-36; see also Timothy May, The Mongol Conquests in World History, London, 2012, pp. 109-29. Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350, Oxford, 1989; Roxann Prazniak, ‘Siena on the Silk Roads: Ambrogio Lorenzetti and the Mongol Global Century, 1250-1350’, Journal of World History, vol. 21, iss. 2, 2010, pp. 177-217. See Ciocîltan, The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade, which throughout gives the impression of confident, at times assertive engagement; also Valeria Fiorani Piacentini, ‘The Golden Age of Genoa’s eastwards trade (13th-15th centuries)’, vol. 19, iss. 1, 2010, pp. 25-40. Colleen Ho, ‘Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century European-Mongol Relations’, History Compass, vol. 10, iss. 12, 2012, pp. 949-50. Ciocîltan, The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade, p. 281. Nicola Di Cosmo, ‘Black Sea emporia and the Mongol Empire: A reassessment of the Pax Mongolica’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, vol. 53, iss. 1-2, 2009, p. 103. I take the Egyptian state’s name for itself from Dmitri Korobeinikov, ‘A Broken Mirror: The Kipchak World in the Thirteenth Century’, in The Other Europe in the Middle Ages: Avars, Bulgars, Khazars, and Cumans, ed. Florin Curta, Leiden, 2008, p. 379; for slave traders’ record-keeping, see Sally McKee, ‘Domestic slavery in Renaissance Italy’, Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies, vol. 29, iss. 3, 2008, pp. 314-5. Ciocîltan, The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade, pp. 165, 201. Ibid., p. 201. Ibid., 206-7. Di Cosmo, ‘Black Sea emporia’, pp. 104-5. May, The Mongol Conquests in World History, p. 209. Di Cosmo, ‘Black Sea emporia’, p. 105; again, ‘Mongols and Merchants on the Black Sea Frontier in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: Convergences and Conflicts’, in Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World, eds. Reuven Amitai and Michal Biran, Leiden, 2005, pp. 394-5. David Braud, ‘The Slave Supply in Classical Greece’, in The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 1: The Ancient Mediterranean World, eds. Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge, Cambridge, 2011, pp. 112-33. Benjamin Z. Kedar, Merchants in Crisis: Genoese and Venetian Men of Affairs and the Fourteenth-Century Depression, New Haven and London, 1976, pp. 9-11. Ciocîltan, The Mongols and the Black Sea Trade, p. 213. Di Cosmo, ‘Black Sea emporia’, p. 25; for nasij, see Thomas T. Allsen, Commodity and Exchange in the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles, Cambridge, 1997. Kedar, Merchants in Crisis, pp. 85-97. Steven A. Epstein, Genoa and the Genoese, 958-1528, Chapel Hill and London, 1996, ch. 5, last paragraph (unpaginated ebook). Kedar, Merchants in Crisis, pp. 2-3. Donald F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume 1: The Century of Discovery, Book One, Chicago and London, 1965, pp. 71-3; Ho, ‘Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century European-Mongol Relations’, pp. 951-3; Maurizio Peleggi, ‘Shifting alterity: The Mongol in the visual and literary culture of the late Middle Ages’, The Medieval History Journal, vol. 4, iss. 1, 2001, p. 27-33. Prazniak, ‘Siena on the Silk Roads’; for Tabriz as a ‘world historical city’, Roxann Prazniak,‘Tabriz on the Silk Roads: Thirteenth-century Eurasian cultural connections’, Asian Review of World Histories, vol. 1, iss. 2, 2013, pp. 169-188. Sheila Blair, ‘The Religious Art of the Ilkhanids’, in The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, eds. Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, New Haven and London, 2002, p. 112. Michael Murrin, Trade and Romance, Chicago & London, 2014, pp. 9-26. Carmel Jordan, ‘Soviet Archeology and the Setting of the Squire’s Tale’, The Chaucer Review, vol. 22, iss. 2, 1987, pp. 128-9. Murrin, Trade and Romance, pp. 43-62; for Chaucer’s Italian contacts, see also Wendy Childs, ‘Anglo-Italian Contacts in the Fourteenth Century’, in Chaucer and the Italian Trecento, ed. Piero Boitani, Cambridge, 1983, pp. 65-87. Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition, eds. Henry Yule and Henri Cordier, 2 vols, New York, 1993, i, pp. 238, 245. Steven A. Epstein, Purity Lost: Transgressing Boundaries in the Eastern Mediterranean, 1000-1400, Baltimore, 2006, p. 122. Jo Ann Cavallo, The World Beyond Europe in the Romance Epics of Boiardo and Ariosto, Toronto, 2013, pp. 45-61. The Alliterative Morte Arthure: A Critical Edition, ed. Valerie Krishna, New York, 1976, lines 840-85. David Wallace, Premodern Places: Calais to Surinam, Chaucer to Aphra Behn, Malden MA, 2004, pp. 181-202. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony, p. 131, endnote 1. For usual disposal of the dead, see May, The Mongol Conquests in World History, p. 202. De’ Mussis, quoted in Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death, Manchester, 1994, p. 19. Ibid., primary sources on the spread of the plague in continental Europe, pp. 14-61.Epstein, Genoa and the Genoese, ch. 5, section ‘How the plague changed society and the economy’.

October 22, 2024

A few interviews

As our crowdfund closes (you can view the results) and I emerge from a whirl of activity, let me save here a few interviews I gave. Eric, Adam and Trish asked about both my historical fiction and my sword & sorcery — and where the line is crossed, how I experienced the difference between those modes.

I got the chance to talk about things I’ve mulled over for years. Certainly a perquisite of having a book out. Gratitude to Oliver Brackenbury, my publisher, for drumming up press opportunities, and to Eric de Roulet, Adam McPhee and Trish Matson for asking intriguing questions.

Eric de Roulet on his blog Sad But Building Worlds

part 1 ‘World-building, but it’s medieval Mongolia’

part 2 ‘Gender, sexuality, and marginalized lives in historical fiction’

This was an in-depth interview that we had to stretch over two parts, about writing in historical settings.

Adam McPhee at Adam’s Notes substack

An interview with Bryn Hammond

About my vision/version of Tchingis Khan, who Goatskin is, and the historical turn in sword & sorcery.

Trish E Matson on her blog What’s the Word Now?

A triple interview with Oliver Brackenbury, Bryn Hammond and Dariel Quiogue

Oliver is the publisher, and Dariel my steppe brother with the other half of our Mongol Double. In my segment: Goatskin, her wanderlust, her love life, and what she means to me.

NESS Short Story Panel Discussion

This discussion of my short story ‘Sister Chaos’ and Dariel’s ‘The Demon of Tashi Tzang’ was a sheer joy for me to watch, and offers keen insights into each of our stories. It neatly contrasts our writing styles and is a great way to gain an idea of the sort of thing you’ll find in our novellas on these characters, back to back in the Double.

I’ve never had a panel on a work of mine before — and such a generous one too. Quite the experience. And seriously, bless Kirk for liking the poetry.

#

Shout-outs to shorter interviews … snippets of insight not found elsewhere! (I did not run out of new material per interview)

Just the Axe, Ma’am with Kevin Beckett

— a great newsletter you should subscribe to if curious about the sword & sorcery revival

From the Sorcerer’s Skull with Trey

Emporium of the Weird (YouTube) with Janek

And a quick review of Waste Flowers at Liam’s Lyceum (YouTube)

#

The book is expected out in the first quarter of 2025. Preorders up soon at the New Edge Sword & Sorcery shop, where issues of the magazine with my Goatskin short stories are also available.

September 6, 2024

Chinggis Khan goes S&S: our Mongol Double

A Mongol Double? Two novellas, where both feature fantasy-Chinggis Khan, at the frontier between the steppe and China? – that contested frontier, that freight of history, that rich and wild inspiration for story?

Brackenbury Books presents Double-Edged Sword & Sorcery. One book, back to back novellas: Walls of Shira Yulun by Dariel R.A. Quiogue, Waste Flowers by Bryn Hammond.

Continuity, for those who have read my Amgalant? You’ll see Tchingis Khan, you’ll see Jamuqa, you’ll see my Hodoe Aral woman Tahilga, just as you knew them in my historical novels. What’s more, you’ll get a look at history post-Amgalant: how does Tchingis go about his war with North China? What helps and hinders him?

Sword & Sorcery heads, who haven’t read my historicals, don’t worry: no knowledge is assumed. You can come in without a clue about Mongols, and my Mongols in particular.

People on this blog might know me, or else they can poke around my posts and find out. But let me introduce Dariel R.A. Quiogue, in his own words. I recommend this post, where Dariel talks about his motivations in fantasy fiction: Forgotten Asia, beyond China and Japan, and his personal perspective on colonialism:

If sword and sorcery is a literary form of rebellion, then my rebellion is against the veneer of Latin civilization, digging for an identity I can accept as my own. So in my writings I try to probe beyond this veil, into the past before Magellan, or outward, tracing back links to other parts and peoples of Asia.

Please do sign up for updates on our crowdfunding campaign. Numbers help, going in. Like most of Chinggis Khan’s campaigns, we’re aiming high, and with the courage of confidence, but bottom line? If you’ve read Amgalant, you remember, every victory is staggeringly chancy. Join us.

Read more, and register your interest, at the link below:

Pre-launch campaign page: Get ready for Double-Edged Sword & Sorcery

June 29, 2024

Crowdfunding S&S & romance

I have a novelette in an anthology being crowdfunded right now, Beating Hearts & Battle-Axes.

There you see my name on the cover. I am beyond proud to stand alongside the other names: SL Huang of The Water Outlaws, Brent Lambert of A Necessary Chaos, TA Markitan who has stories in A Book of Blades I and II, David C Smith of Sometime Lofty Towers, Valerie Valdes of Where Peace is Lost. Jay Wolf is our wonderful editor.

Six novelettes of about 12,000 words, telling a Sword & Sorcery tale with an integral relationship story.

When Oliver Brackenbury, the publisher, asked me to be a part of the anthology, I was keen for the chance to explore the love relationship between my Goatskin and Sister Chaos (she who goes by several pseuds) more deeply. Previous Goatskin stories can be found in New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine issues 0 and 1, and A Book of Blades II. My historical fiction series Amgalant leans heavily into relationships, and has a strong love story — while *not* being historical romance, as the anthology isn’t capital-R Romance. So this was more back to my usual than a new departure.

We have met our minimum funding goal, which means the book’s going ahead. First stretch goal is an internal illustration for each story by Trevor Ngwenya – you can bet I want that one. Second stretch goal is a significant discount on shipping for Rest of the World folk, and as an Australian familiar with the cost disadvantages of book acquisition from overseas, that one means a lot to me too.

After those two goals, funds go toward further projects from Brackenbury Books. This anthology is the first book from what hopes to be a shiny new publisher of Sword & Sorcery. I expect more in the spirit of New Edge Sword & Sorcery Magazine, also from Oliver Brackenbury: innovative and inclusive Sword & Sorcery, in other words so much up my alley you can come and swig a drink with me in the street or the tavern if it lets us in (I write social outsiders, you’ll often be refused at the fantasy taverns). I’m excited to see the future of Brackenbury Books, and I have a great respect for Oliver from our work together in the past.

The campaign runs until July 21. It’s on Backerkit, described as like Kickstarter but better. There are exclusive extras through the crowdfund, and you can add on issues of New Edge Sword & Sorcery at a crowdfund-only discount. I have a Goatskin story, ‘Sister Chaos’ in issue 1 from last year, and a non-fiction piece in one of this year’s issues, 3 or 4.

Here’s the campaign link. I’d be delighted if you choose to back.

www.backerkit.com/c/projects/brackenbooks/beating-hearts-battle-axes

May 22, 2024

at 60, life with book

Bravely, I am 60 today.

When I wrote Amgalant, roughly between ages 40-50, I thought of it as my life’s work. It still is. Not that I don’t dig what I’m doing now, but those books were an effort I can’t put in again.

And that’s fine, loves. I had writer’s sadness before Amgalant, but not after.

They were wildly ambitious books to write, and I met them at the right age. Not that conditions were ideal: when I look back I think, hang on, this stuff was going on in those years, how did I?

The before I remember: a ghastly state of frustration and enforced writer’s idleness, in my thirties, waiting for the right project, with no guarantee I’d ever write anything significant. The after was rough too, for a few years: angst about reaching (not reaching) an audience.

Perhaps it’s by dint of doing other things I’ve come to a peace about that. Still, if you think I’m ever going to cease plugging Amgalant, you’re mistaken.

Here’s a little gallery of me + book.

circa 2013

I’m going to celebrate with four links to explore Amgalant and the writing thereof, from over the years.

My post ‘A Bastard Art’: how I figured out writing historical fiction based on what was already an artistic text. ‘To think about originality and inherited story, I turned to medieval romance.’

Perhaps the most thorough review of Amgalant, by John Caviglia, author of Arauco.

A craft-based interview in Marian L Thorpe’s Writing for Effect series. ‘Bryn has chosen to discuss how she used poetic speech, homely metaphor, and lively conversation in her work.’

A Five Books list at Shepherd, in which I try to convey my idea of ‘seriously epic historical fiction’ by examples. It isn’t just about size …

Cheers for visiting the site.

Buy Amgalant direct at my Payhip store

April 23, 2024

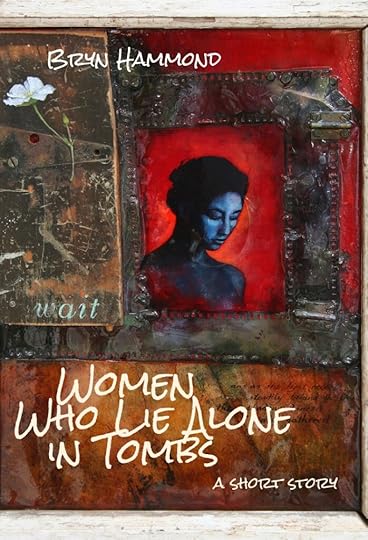

Women Who Lie Alone in Tombs

I’ve published a new short story, ‘Women Who Lie Alone in Tombs’.

I’ve published a new short story, ‘Women Who Lie Alone in Tombs’.

This is the description:

After a failed insurrection, Ixin follows her lady Ai Jaruq to a Mongol queen’s court to join in a wider revolt.

In the lost Khitan kingdom, there were women who found space to live unwed — the ‘women who lie alone in tombs’, without husbands. Is that what Ixin wants, or can she strike out on a new type of life altogether?

A slice of thirteenth-century women’s lives, mostly historical, with a zest of speculation.

And this is the Afterword:

‘Women Who Lie Alone in Tombs’ is a post-Amgalant story. It fits into the Amgalant world shortly after the events of those novels, although of the characters, only Yisui Queen features in Amgalant Two: Imaginary Kings.

Bibliography? I greatly recommend Women of the Conquest Dynasties: Gender and Identity in Liao and Jin China by Linda Cooke Johnson. It’s here I read most about Khitan women who managed to remain single and lie alone, without husbands, in their tombs.

Qip pops up again in my less historical sword & sorcery, set in the same time and place as Amgalant but with a fantasy slant. You can find Qip in my story ‘The Grief-Note of Vultures’ in New Edge Sword & Sorcery #0, which is a free download in digital: newedgeswordandsorcery.com

In case you wonder what’s historical and what isn’t, here’s a partial list (you can ask me others).

Attested:

Swell-root and its uses. It’s a particular root that swells in moisture.

The institution of ‘fake pageboys’ in high Jin circles.

Single women, and the push to make them allowed in Khitan society.

Khitan attitudes to chastity and sex before marriage.

The first Khitan widow-queen who chopped her own hand off to lay in her husband’s tomb and silence critics of her continued rule.

Unattested:

Qip. But I bet she existed.

This short story is free for the week 23-30 April in our HistFic Outside the Box on Bookfunnel. My Amgalant novels are also on sale at 50% off.

January 7, 2024

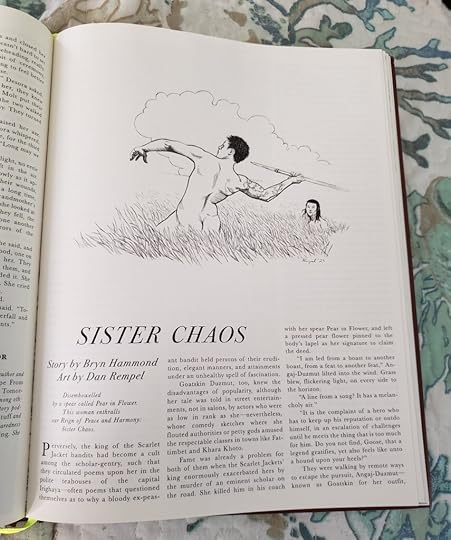

On story process: ‘Sister Chaos’

As usual, a story is an amalgamation of elements, and my main job seems to be to hammer them together, the ideal to make them augment each other. This post is a look at a few elements of ‘Sister Chaos’, my story in New Edge Sword & Sorcery #1.

As usual, a story is an amalgamation of elements, and my main job seems to be to hammer them together, the ideal to make them augment each other. This post is a look at a few elements of ‘Sister Chaos’, my story in New Edge Sword & Sorcery #1.

To start with the title. I meant this story to focus on chaos – enough to let me use the title, which I’d had sitting around. When I first ventured into S&S, not two years ago, I knew chaos was going to be a theme. In my sketches-to-self are statements too crude to say to other people, but this is a process post, so in their naked inglory:

I want to make a case for chaos, I argue on the side of chaos… Orderly society has rarely been on my side, and I think chaos opens up a lot of possibilities. So I want to haul on those law-order axes, and those good-evil axes, and make sure they align to my truth, and my experience. Who’s doing damage, that I feel and know, and fear? This is what I have to quiz myself on, when I come to write a story.

Now, at an certain editorial stage I was told I’m to be in the Michael Moorcock issue, whose Elric stories have mused on Law and Chaos for half a century and hugely influence the ideas about chaos you come across in fantasy. It was cheeky to continue my focus. But S&S had seemed to me an opportunity to talk about chaos, in large part because of that influence of his, so, to put my own spin on chaos is only tribute.

Besides, my spin is less existential, more social (not that those thing don’t interact). As a challenge – note that challenges are things one sets oneself as writer, prior to being a challenge to the reader – I have Qi Miao ‘murder an eminent scholar’ on the first page. Often her kill-fare is listed as constables, magistrates, officials of the state machinery. A couple of pages later we find out the scholar was an official too, and in his judicial duties used to sentence peasants to the lopping off of limbs. That the ‘famous prose stylist’ and the judge are the same person is a point neatly captured in the term ‘scholar-official’, familiarly used in histories of China. But even without that term, the point is that cultural and legal forces of order tend to be interlocked. It was likewise in the history of Europe. When Qi Miao flytes the edifice of the classics, she is also applicable to the European intellectual elite. You can transpose to Greek and Latin and the patriarchal order of the West, and she won’t change her flyte a jot.

Here’s a tangent, from my back story as a historical novelist. The Mongol invasion of China, of which we hear intimation in ‘Sister Chaos’, led to social upheavals too and intellectual disruptions. Khubilai Khan suspended the civil service entry examinations in the classic texts. Often historians accept the perspective of scholars who watched their hold on affairs severely weaken and who left written sources outraged at barbarian crudity and attacks on culture. But Khubilai had his reasons: a diversity of ethnic make-up in his government led to a diversity in the ideology behind advice; he was determined to draw on a wider range of talents than those shaped by study of the ‘Confucian’ classics. (You can read a lot more about Khubilai’s innovations in this post).

Who is order for? Who gets left out?

In my story, Goatskin and Goose visit the margins where they meet a queer shaman and a spirit of disparate pieces.

Anthropological sword & sorcery?I pinch my subtitle from Anthony Perconti’s comments on my story.

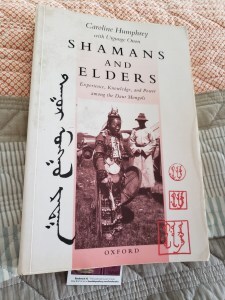

Anthropological sword & sorcery? No doubt, after I came straight from a heavily anthropological historical fiction. In that genre my cry has been, ‘Read anthropology. History books won’t be nearly enough.’ Anyhow, I have utilized the same sourcebook. My spirit Galierti owes to the account of Holieri in Shamans and Elders: Experience, Knowledge, and Power among the Daur Mongols by Caroline Humphrey with Urgunge Onon. I quote a bit on Holieri, ‘the Shattered Ancestor’, in my review of this book:

Although they might use the same idioms, such as ancestry and imperial power, shamans suffused these ideas with subversive content, thus creating a distinctive sense of identity for the people… [T]hey made almost nothing, in shamanic practice, of their own real patrilineal ancestors and they reached for a lateral, inclusive, and metaphoric idea of what an ancestor might be.

Towards the ancestor spirit Holieri went humans and body parts of humans, as well as

animals, birds, aquatic creatures, artefacts, and mythic beings … Self-identity was not located inside a unique bounded ‘we’ but shattered outwards to embrace all forms including the broken, the imperfect, and the humble … Its placing consisted of a wooden box, with two doors or a curtain in front, containing a series of carved objects, representing tens of spirit-parts… People in Horli told me that it could also be made very simply: one took a bit of wood in the shape of a human, broke it, and worshipped the parts.

There is a strong through-line from my story ‘Ill Spirits’, although that wasn’t sword & sorcery.

Outsiders‘Outsiders’ is the theme common to my elements. I have written before about what sword & sorcery means to me, and the answer is mostly, it’s known for outsider perspectives.

And that always needs to be pushed further. Conan? When he walks into an inn he intimidates every patron and the men in the joint (I’m told – I don’t know) want to be him.

I’ll do heroes who make less impression, have less physical presence, who walk into a bar and risk stares of hostility or glances of contempt. I guess that means I don’t want wish-fulfilment from my sword & sorcery fiction. I am a serious sort who seeks much exploration of the real in her escapism. I value Janrae Frank’s ugly portrait of a woman with post-combat trauma. I want to write about poverty, although that’s hard even in S&S fantasy where your happy-go-lucky protagonists lurch from one temporary embarrassment to another. And how do you write about homelessness in a genre where every hero wanders? Still, Delany solved most of these problems back in Nevèrÿon (homelessness, in particular, important to Delany: see this beautiful profile).

I haven’t achieved these things yet. In a way I did most towards them in my first stab, Goatskin’s origin story, which is slighter as a story. One needs aims and ambitions, to keep writing.

Antelopes and camelsMy ‘bulb-nose’ is the saiga antelope. I made up nothing about the saiga.

Here’s the Saiga Resource Centre with as much as you want to know about this endangered species of the steppe.

Confession time: I have never seen the 80s Conan movies. But I watched the clips of Conan punching camels (frankly, I hope they ‘taunt him a second time’ as the French knight said to King Arthur). However, at certain junctures it’s kind of necessary to punch a camel. I couldn’t resist Angaj-Duzmut telling us that’s a real thing.

A puzzle, a poemIn the first scene Angaj-Duzmut quotes a line or two ‘from a song’, and the first person to identify it wins … I don’t know what kind of prize, but see me. Its origin lies far from the steppe. Something I’ve wanted to use for decades.

As an extra, here’s a poem I wrote, a companion piece to the story. It is, you might notice, contra Yeats [‘The Second Coming’]. Which is at least as cheeky as writing about chaos in the Moorcock issue. I’m never going to see eye to eye with a poem where ‘the centre cannot hold’ is a bad thing (I do love Yeats, though: ‘Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop’, those fey poems about Fergus and Wandering Aengus).

What Rough Beast?

What rough beast slouches out of desert sands,

Or vast salt marshes or bleak windswept steppe,

Towards your holy city?

Against your bastions what frail wild four legs,

What low glimmer of horn or weightless hoof

That you chased from your purview a century ago?

What scapegoat back from the wilderness,

Having eaten of your sins, nothing else to fat it,

What skinny goat? What creature slain and risen?

Its name is Chaos –

But you won’t think that suits

Such a scrawny rag in such a quiet return.

Nevertheless, our name – we whom you refused,

And thought not of, and pushed

To the gutter of the street the other day.

Your humblest, us.

Cut-off limbs, clapped-out soldiers,

A starved child or two,

Skull of stray cat, foot of tiny wren.

Unconsidered fragments.

What rough beast?

With thanks to Dan Rempel for the wonderful art to my story. Thanks to Oliver Brackenbury who has been the most wonderful editor.

I’ll leave you with a link to June Orchid Parker’s story process post, ‘The Writing of ‘How Many Deaths Till Vengeance?’’.

And of course, a link to the New Edge Sword & Sorcery website. There’s an exciting year ahead: please sign up to the newsletter and stay in the loop.