Bryn Hammond's Blog, page 11

March 7, 2013

Single women on the steppe?

As a happy single these days, and even committed I think (that’d be a first) (enough about me) — I’m intrigued by the possibility that certain steppe societies allowed women to live singly.

As a happy single these days, and even committed I think (that’d be a first) (enough about me) — I’m intrigued by the possibility that certain steppe societies allowed women to live singly.

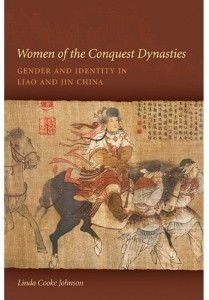

Liao, at least. But Liao was an aspirational society for other nomad cultures, which seem to have found them fit to imitate. Almost the only information I have on this comes from Linda Cooke Johnson’s study of Liao and Jin women, Women of the Conquest Dynasties. She offers the example of Changge (1006-1077), a scholar and poet and member of the royal clan, on whom we have a biography in Liao records. “The entry specifically notes that Changge never married, and [her] epitaph mentions no husband, which suggests that marriage may not have been universal among Liao women.” [p.7] Other than this, “The numbers of Liao tombs in which women are the sole occupants also suggest that other women may never have married.” [p.111-2]

It’s not much to go on. But Linda Cooke Johnson speculates that the Liao/Kitan custom whereby women married men of the generation beneath them may have led to singlehood. Women of the royal clan (that I like to call the Ile, instead of a Chinese transcription) were often significantly older than their husbands, but “the primary marriage pattern in which younger males married somewhat older women was common among both upper- and lower-class Kitans. Although Jin sources are less explicit, the Jurchen also evidently followed the generation-gap pattern in arranging marriages…” [p.99] We’ll want to know at this point, sex before marriage was not a no-no. “Liao and Jin sources indicate that premarital permissiveness was a widespread and well-entrenched social custom…” [p.86] We might feel that the unmarried were ‘left on the shelf’, but that’s our assumption, and this on girls’ sexuality reminds us not to make foreign assumptions.

In Mongol history, we have Qaidu’s daughter Qutulun (c.1260-1306) who tried not to marry, who wished to remain as her father’s right hand in war and politics. As I say, I believe Liao was a glamorous culture for other steppe societies, and I have to guess that Qutulun, to justify her life, cited Liao women, who before her had commanded troops — possibly she cited them on singlehood, too. That is, doesn’t the Liao information mean she needn’t have been pitted against society, to live thus? Still, Qutulun gave in to pressure, and to slander: she and her father were accused of incest, and after this she chose a husband — one of her father’s followers, which let her stay at her father’s side. I was a daddy’s girl too.

That incest accusation, a low blow, has an after-history in a Karakalpak epic, ‘Kyrk Kyz/Qiz’, known in English as ‘Forty Maidens’. There, a brother and sister lead the fight against a Persian invasion. The enemy Persian Shah slanders them with incest to undo them. The brother, humiliated, leaves his troops and people, but they refuse to believe the accusation and choose the sister to head the army in his absence. Here I must see a memory of Qaidu and Qutulun. The latter’s legend as a war champion and army leader surely went towards the inspiration of this epic, which boasts more women under arms than an average plot of Xena.

I’m afraid that’s the end of my observations. I’ll keep digging, fascinated as I am, for single women on the steppe.

# # #

– Linda Cooke Johnson, Women of the Conquest Dynasties: Gender and Identity in Liao and Jin China, University of Hawai’i Press, 2011

February 24, 2013

The UB Post on Walker Pearce

Yesterday I got up the gumption to send Jack Weatherford a fan email. Not only didn’t he mind, he took time to answer and even inquire into this site. Proud to have his feet here, I can tell you. Right, I’ve always been the hero-worship type, but his work is inspirational and of enormous use to me, and if my spirits were flagging, daunted by Three ahead and who cares about these subjects in the world? his kindness has given me the spurt I need.

He sent me a story from the UB Post, ‘Expats in UB’ by Allyson Seaborn, on his wife Walker Pearce who has adventured over Mongolia in a wheelchair. Now, I’d seen this… hey, I’m a fan, I keep track. Maybe you haven’t–here’s a link. Follow the link, because these are two wonderful people, loved in Mongolia. As Jack Weatherford is quoted to say in the story, it isn’t the official honours he’s had there that matter most to the both of them, but the daily “care and warmth”.

February 14, 2013

Solitary writers (are you out there?)

Writers have different habits, different ways to write, and I hope we can politely leave each to our own. It is an exercise in politeness, as I know from myself, because when I hear a friend say, ‘I’m sending out to my beta-readers,’ I want to howl at her, No no no no no. Of course I do no such thing.

Obviously, I don’t use beta-readers. I am the alpha to omega reader of my work, until it’s in a state fit to print. This makes for slow publishing: you need years of perspective on a work, to be an omega reader yourself. So I had my first book in my hands for nine years; I only had beta eyes – or new eyes as I call them – after I’d finished the second and come back. To ask another person for new eyes… no, I cannot contemplate it. They see differently. Only I can see the true road for my book, even if I can’t see yet, even if not for years. Foreign eyes (as I think of them) I fear must hopelessly confuse. Muddy the waters. When I can’t see clearly, the last thing I need is advice in my ears. I have to stare until I see. Or take a hike, come back in a few years’ time with the eyes of a stranger. But my eyes.

One hand writes a novel, that’s my creed. It’s no use to try to shift a belief like that, so I hope we writers can rub along together with our different habits and beliefs.

One hand, one eye to see the right words (did you hear Tolkien creep in? Bugger off, Tolkien. If I’m as crazy as Sauron, let it be so. I can tell you I’ll never change). Where was I? Only the creator’s eye can spot the right word. Other people’s words must be inserts, intrusions, and wrong. Wrong in ways you won’t notice, but you’ve been shifted, if ever so slightly, off your tracks. So if you’ve lost the sense of those tracks, wait. Wait. Wait for years. Others’ input, foreign influence – is your greatest danger.

Now, I can scarcely understate how out of fashion this writing philosophy is. Here I’m in the privacy of my blog; if I essayed to defend this argument in a writers’ public square, I’d be shot down or locked up. But I know I’m not the only one who writes this way – are you out there, solitary writers?

To express my puzzled feelings, crudely, I have a made-up tale of Picasso and the paintbrush. That’s when a bystander looks over his shoulder and says, ‘I don’t think people are going to understand that smudge in the corner. How about you turn that into a cabbage?’ He got a paintbrush through the eye, didn’t he?

It seems to me that written arts are singled out, for the art-by-committee strategy. And I don’t understand why that should be so. Writers have always fought to keep creative control, of course – and lost in general. ‘Go indie’ we urge writers of the past, safely in their graves. Except I’ve met on indie review sites the admittance question, ‘Have you been professionally edited?’ And I can’t tick yes to that box. I can tick, ‘No, piss off. But give me credence. Every word is mine. Every judgement call, my judgement – because no-one else knows what I’m doing with the book, do they? Try it. Call it single malt and have a swig.’

January 20, 2013

Impressions of ‘Manas’

First impressions of the online Manas, after a once-through yesterday, at the speed I might have heard it sung. This epic talks to me, more directly than the Iliad, say, my king of epics… though maybe, kingly-wise, not as near to me, not at my heart and hearth. I am most emotional about Beowulf, whose hero is my hero, above whatsoever figures in history or fiction. But yesterday I laughed and felt and fell in love with Manas at the age of eight. It isn’t so closed a poem as Beowulf (where I can feel the one hand, that draws significance); to go on I have to switch to A.T. Hatto’s translation of another singer – with plot divergences. Have to see how I feel about that one. For now I mean the online Manas, sung by Saiakbai Karalaev, translated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil: which leaves off when Manas is still twelve – in a monster-child way, the kid’s just flattened a detachment – and Joloy and Dongo attack from the capital of China. Yes, that’s Joloy/Joloi who has his own epic, which we met (or I did, and one or two of you) in The Old Ideal.

First impressions of the online Manas, after a once-through yesterday, at the speed I might have heard it sung. This epic talks to me, more directly than the Iliad, say, my king of epics… though maybe, kingly-wise, not as near to me, not at my heart and hearth. I am most emotional about Beowulf, whose hero is my hero, above whatsoever figures in history or fiction. But yesterday I laughed and felt and fell in love with Manas at the age of eight. It isn’t so closed a poem as Beowulf (where I can feel the one hand, that draws significance); to go on I have to switch to A.T. Hatto’s translation of another singer – with plot divergences. Have to see how I feel about that one. For now I mean the online Manas, sung by Saiakbai Karalaev, translated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil: which leaves off when Manas is still twelve – in a monster-child way, the kid’s just flattened a detachment – and Joloy and Dongo attack from the capital of China. Yes, that’s Joloy/Joloi who has his own epic, which we met (or I did, and one or two of you) in The Old Ideal.

These paintings are from Qing China’s wars on the steppe, first east, where they subject and enlist the Mongols, then against Oirats with their Zunghar state. In Manas (and this is a typical situation in extant Turk epic) Mongols known as Kalmyks are in league with the Manchus from Beijing; and they march west, a threat to peoples throughout Turkestan, like the Kyrgyz of this poem. The painting above has Kyrgyz or Kazakhs, post-conquest or perhaps to stave off conquest, with tribute of fine horses for the emperor. While beneath is a champion named Ayuxi, a captured Zunghar who thereafter fought on the side of the Qing. He can represent Joloy and his ilk, steppe greats in high standing at the Chinese court.

These paintings are from Qing China’s wars on the steppe, first east, where they subject and enlist the Mongols, then against Oirats with their Zunghar state. In Manas (and this is a typical situation in extant Turk epic) Mongols known as Kalmyks are in league with the Manchus from Beijing; and they march west, a threat to peoples throughout Turkestan, like the Kyrgyz of this poem. The painting above has Kyrgyz or Kazakhs, post-conquest or perhaps to stave off conquest, with tribute of fine horses for the emperor. While beneath is a champion named Ayuxi, a captured Zunghar who thereafter fought on the side of the Qing. He can represent Joloy and his ilk, steppe greats in high standing at the Chinese court.

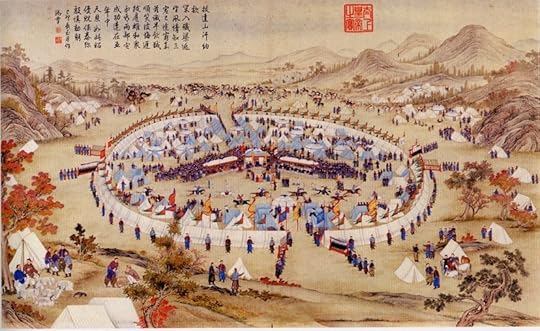

Manas opens with calamity for the Kyrgyz people: invaded, enslaved, slaughtered or scattered. As a picture of large-scale war, I couldn’t call to mind its like, in old epic. We don’t look at a hero or a king, at this stage, or stay with the leadership cluster; we look at a people. We hear from the girls who are taken as booty, the old men who are beaten up, the remnant populations that are driven into exile. I learnt about war habits. Loot, tax and tribute. Snippets such as the capture of craftswomen. I gained a real sense of war on the scale known in these parts – with Qing, or with Chingiz. It’s no-punches-pulled, and I can’t say that epic often gives me the groups of grandmothers who suffer. Here’s the type of big-scale battle painting we have from Qing’s conquest of the steppe. Notice the cannon ranks and gun smoke.

Rarely were a people so in need of a hero.

Rarely were a people so in need of a hero.

Leadership is important, in Manas. A lament runs through this section for Karakhan (=black khan), whose death exposed the Kyrgyz to their enemies. We never saw him, he was dead before the poem began – but we miss him. He left eight orphan sons, children, and of these, Jakip has promise, and starts a line in rear-guard action or fight-back against the Kalmyks and Chinese (called Kitay: that’s our Cathay). A neighbour khan of the Noygut, Baltay or Akbaltay (ak=white) who has been stripped of his wealth in herds, whose people have been wiped out, determines to lift a hand, to join Jakip’s efforts and at least die fighting – instead of curl up crying. Together they attack a troop with ninety-five camels loaded with loot from their tribes. For a moment they know success. Shortly they are worse off than ever. They are punished, and Baltay – who has my admiration by now – undergoes the humiliations of submission. I found this rough. ‘Humiliation’ is a word often used; there are no bones made about how low our heroes go; however, afterwards Baltay is no less esteemed by the people he led, and leads. I liked that. Here’s a celebration of surrender: a little figure on his knees in the centre of the Qing camp.

To Be Continued, because I’m pooped for today. Tomorrow we have a change of scene, and an uplift in the story.

To Be Continued, because I’m pooped for today. Tomorrow we have a change of scene, and an uplift in the story.

– the online Manas translated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil, 2005. Link: http://www.silk-road.com/folklore/manas/manasintro.html

– art: by Guiseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), Jesuit missionary and court painter to the Qing

– for a history of the Qing’s steppe wars (and where I found these paintings) see Peter C. Perdue, China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia, the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005

January 19, 2013

Impressions of Manas

First impressions of the online Manas, after a once-through yesterday, at the speed I might have heard it sung. This epic talks to me, more directly than the Iliad, say, my king of epics… though maybe, kingly-wise, not as near to me, not at my heart and hearth. I am most emotional about Beowulf, whose hero is my hero, above whatsoever figures in history or fiction. But yesterday I laughed and felt and fell in love with Manas at the age of eight. It isn’t so closed a poem as Beowulf (where I can feel the one hand, that draws significance); to go on I have to switch to A.T. Hatto’s translation of another singer – with plot divergences. Have to see how I feel about that one. For now I mean the online Manas, sung by Saiakbai Karalaev, translated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil: which leaves off when Manas is still twelve – in a monster-child way, the kid’s just flattened a detachment – and Joloy and Dongo attack from the capital of China. Yes, that’s Joloy/Joloi who has his own epic, which we met (or I did, and one or two of you) in The Old Ideal.

These paintings are from Qing China’s wars on the steppe, first east, where they subject and enlist the Mongols, then against Oirats with their Zunghar state. In Manas (and this is a typical situation in extant Turk epic) Mongols known as Kalmyks are in league with the Manchus from Beijing; and they march west, a threat to peoples throughout Turkestan, like the Kyrgyz of this poem. The painting above has Kyrgyz or Kazakhs, post-conquest or perhaps to stave off conquest, with tribute of fine horses for the emperor. While beneath is a champion named Ayuxi, a captured Zunghar who thereafter fought on the side of the Qing. He can represent Joloy and his ilk, steppe greats in high standing at the Chinese court.

Manas opens with calamity for the Kyrgyz people: invaded, enslaved, slaughtered or scattered. As a picture of large-scale war, I couldn’t call to mind its like, in old epic. We don’t look at a hero or a king, at this stage, or stay with the leadership cluster; we look at a people. We hear from the girls who are taken as booty, the old men who are beaten up, the remnant populations that are driven into exile. I learnt about war habits. Loot, tax and tribute. Snippets such as the capture of craftswomen. I gained a real sense of war on the scale known in these parts – with Qing, or with Chingiz. It’s no-punches-pulled, and I can’t say that epic often gives me the groups of grandmothers who suffer. Here’s the type of big-scale battle painting we have from Qing’s conquest of the steppe. Notice the cannon ranks and gun smoke.

Rarely were a people so in need of a hero.

Leadership is important, in Manas. A lament runs through this section for Karakhan (=black khan), whose death exposed the Kyrgyz to their enemies. We never saw him, he was dead before the poem began – but we miss him. He left eight orphan sons, children, and of these, Jakip has promise, and starts a line in rear-guard action or fight-back against the Kalmyks and Chinese (called Kitay: that’s our Cathay). A neighbour khan of the Noygut, Baltay or Akbaltay (ak=white) who has been stripped of his wealth in herds, whose people have been wiped out, determines to lift a hand, to join Jakip’s efforts and at least die fighting – instead of curl up crying. Together they attack a troop with ninety-five camels loaded with loot from their tribes. For a moment they know success. Shortly they are worse off than ever. They are punished, and Baltay – who has my admiration by now – undergoes the humiliations of submission. I found this rough. ‘Humiliation’ is a word often used; there are no bones made about how low our heroes go; however, afterwards Baltay is no less esteemed by the people he led, and leads. I liked that. Here’s a celebration of surrender: a little figure on his knees in the centre of the Qing camp.

To Be Continued, because I’m pooped for today. Tomorrow we have a change of scene, and an uplift in the story.

# # #

– the online Manas translated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil, 2005. Link: http://www.silk-road.com/folklore/manas/manasintro.html

– art: by Guiseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), Jesuit missionary and court painter to the Qing

– for a history of the Qing’s steppe wars (and where I found these paintings) see Peter C. Perdue, China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia, the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005

January 14, 2013

‘Manas’: inspiration from Chingiz, Bilga Khaghan

Today I read the beginning of Manas – the Kyrgyz oral epic – and was struck by Chingiz resemblances. Already I think Chingiz overshadows the story. I’m not alone: the introduction to the online Manas discusses its similarities to the Secret History of the Mongols. There are obvious clues. The father of Temujin’s wife-to-be has a dream… I’ll quote my own words, that are straight from the Secret History (of course): “In my dream I saw a gyrfalcon in flight, sheer white, with the sun and the moon in its talons. It flew down to me, as if I had cast the bird, and alighted on my glove with its trophies.” That’s a bold dream, you’d think, but the epic poem is three times as bold. Here’s what the future father of Manas dreams:

Today I read the beginning of Manas – the Kyrgyz oral epic – and was struck by Chingiz resemblances. Already I think Chingiz overshadows the story. I’m not alone: the introduction to the online Manas discusses its similarities to the Secret History of the Mongols. There are obvious clues. The father of Temujin’s wife-to-be has a dream… I’ll quote my own words, that are straight from the Secret History (of course): “In my dream I saw a gyrfalcon in flight, sheer white, with the sun and the moon in its talons. It flew down to me, as if I had cast the bird, and alighted on my glove with its trophies.” That’s a bold dream, you’d think, but the epic poem is three times as bold. Here’s what the future father of Manas dreams:

Reaching with my right hand,

I grasped the sun for myself.

Reaching with my left hand,

I caught the moon for myself.

My right hand held the sun,

My left hand held the moon.

I took the sun

And put it in the place of the moon,

I took the moon

And put it in the place of the sun. (lines 3083-92)

I don’t know (yet) what that signifies, except it’s fast and loose with the heavenly objects. I have had glimpses ahead to other Chingiz echoes, from the blood clot in his hand as he comes from the womb to, possibly, the manner of his death. It’s more than specifics, though… it’s the story, it’s the scope. I can only talk hazily now – I’ll get back to you.

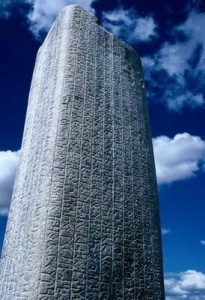

I consulted another introduction to Manas, by R.Z. Kydyrbaeva. The poem, she says, “can be seen as an imaginary history of the Kyrgyz people, in which myths, fairy-tales, legends and historical events are inextricably interwoven.” She finds distinct echoes of the stele inscribed by Bilga Khaghan of the Blue Turks (pictured above) that I quote – almost word for word – early in Tribal Brawls:

“I did not come to the throne a rich king. I came to a weak people, without food on their inside, without clothes on their outside. Of this I spoke with my brother Kul Tegin, that the work of our father Elteresh for the Turks’ name and fame be not lost, and we spent, for love of the Turkic people, our nights without sleep and our days without a spell from labour. Our nobles and our people who had gone to foreign service came back on foot and naked. Forty-seven campaigns, twenty battles fought Elteresh; thirty-five wars fought Kul Tegin and I, to feed and clothe them.”

Up against this Kydyrbaeva quotes Manas:

Forty-two years was he khan,

Gathered solitary kites and turned them into worthy birds,

Gathered exhausted slaves and turned them into a people,

Gathered gold so that it lay scattered like stones,

Made that scattered people into a great nation. (lines… he doesn’t tell me)

She claims, “The very text of the epic, its compositional structure and stylistic qualities evoke the eulogy of Kul Tegin by Bilga Khaghan.”

And the common theme is unity – with the common weal of the people. “The whole spirit of the epic centres on the idea of unification, an idea that runs through Manas. It constantly stresses that fragmentation and intestine strife are signs of weakness.”

Which certainly echoes both Bilga Khaghan’s stele and Chingiz’ life story.

– the online Manas translated by Elmira Kocumkulkizil, 2005. Link: http://www.silk-road.com/folklore/manas/manasintro.html

– R.Z. Kydyrbaeva, ‘The Kyrgyz epic Manas’ in C.E. Bosworth and M.S. Asimov, editors, History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Volume IV, The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century. Part Two: The achievements. Unesco, 2000.

December 22, 2012

Nomads: state evasion?

State evasion/state prevention. Clastres, French radical, blasted into anthropology with these concepts in the 70s. The title of his definitive essay says it: ‘Society Against the State’. He studied peoples of South America and contended that their lack of a state is not because they are, or ever were, too primitive to establish states, but because they have cleverly in place tactics to prevent the rise of a state amongst them. They are consciously in defence against institutionalised power. What’s more, of course, they succeed.

I first read about steppe nomads as state evaders in Philip Carl Salzman, Pastoralists: Equality, Hierarchy and the State. We know them as state invaders, but are slow to see their strategies for the avoidance of government. Think of the view from Persia. Salzman does a study of ‘pastoralists of Iran’ – of a patchwork of different tribes/ethnicities, with each its tactics, dependant on situation, location, to NOT became a part or a full part of the Iranian state. They live in the interstices. They live in difficult terrain. They stay on their feet, of course, and that is key. To settle down is a danger, and Salzman looks at cases where once-nomads have had to settle. They lose their liberty of movement, which is the ability to say no. They pay their taxes, like the rest of us, and slip to the status of peasants. It isn’t seen as evolution or advance, if you ask a nomad. How does the Iranian government see its pastoralists? They are ‘backwards’, their growth has been inhibited by their awkward or dead-end way of life.

Integral to the nomads’ state-avoidance – in Salzman’s study – is an ethic of equality, an anti-hierarchy attitude. To understand this, to understand where this comes from – is Salzman right to tell us that pastoralist tribes, in general, yes, are insistently anti-power, that they hold a value of egalitarianism, that their tribal structures are built to frustrate and limit chieftaincies? – as buttress or understructure to this, I think you need a deep background. I did.

Christopher Boehm, who wrote Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior, is a primatologist turned anthropologist. That is, he moved from the study of apes to the study of our ancestors – in the light of hunter-gatherers extant today. To me, at that point in my explorations, his book was invaluable, worth galleons of Spanish treasure. For he explains – whether to your satisfaction is up to you – how a species, our species, can achieve and maintain egalitarianism, even if we began with the unpretty politics of apes. He does this in the light, as I say, of just such anthropology as Clastres and Salzman, who watch the techniques tribal peoples have to defend themselves against that p-word, power. Boehm tromps around the world to see anti-power attitude in action. And he finds a similarity of story, in the least ‘advanced’ of societies, where in pockets they remain – those societies that may still shed a light on us, back when the human species were hunter-gatherers – a similarity that is suggestive of his thesis. He works backwards from them, and he works forwards from the apes, and… you be the judge. It’s an important book.

This post was prompted by a book I’m engaged in at the moment: The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia by James C. Scott. He quotes Clastres for his epigraph: “It is said that the history of peoples who have a history is the history of class struggle. It might be said with at least as much truthfulness, that the history of peoples without history is a history of their struggle against the state.” James C. Scott sets out to write the unwritten history of an area he calls Zomia, from words for ‘hill people’. Zomia is the hills – Zomia straddles eight states – it is the area people escape to, out of those states, whose reach can’t extend into the high terrain. His main contention is as follows. Hill peoples, even in local accounts, have always been seen as remnant populations, as savage peoples left behind by civilizations, as ‘our ancestors’. This is untrue. Most of the population of the hills fled there. Away from these vaunted civilizations, with their wars, their taxes, their famines and diseases. People choof off. States don’t like to advertise the fact that their citizens choof off, at the rate they do, and if you’re unconscious of this phenomenon, the state wants you to be.

Hey, it’s written by an anarchist – I suppose. – The web just told me ‘choof off’ is Australian slang. Is it? You know I mean scarper.

While I read Scott on the escape of subjects from states, I think constantly of the steppe. He puts me in mind of the steppe – he visits the north of China, too. I think of the archaeological finds of Gideon Shelach, who deduces a story uncannily like the story Scott tells, in Northeast China circa 1100-600 BCE. Uncannily, because… his article, in a book called Mongols, Turks and Others, came as a thunderclap to me, I don’t know whether it’s caused a splash in academia. Or a riot. It’s fantastic, and perhaps my favourite thirty-three pages on the whole subject (though a few of those pages are dry). I’m not an academic, right? I’m a novelist. I’m certainly excitable where source material is involved.

About the article. He asks, “Why did pastoralism gain importance during the first millennium BCE?” and goes on, “I argue that rather than looking for determinative factors such as climatic changes or external influences we should try to explain the choices made by the local population… The transition to pastoralism… was coupled in this area with an ideological change as well as with a new definition of cultural affiliation.”

In this area of Chifeng, where either lifestyle was possible, some people chose to become pastoralists, and some people remained as agriculturalists. When people made the pastoral choice, they displayed – from the archaeological remains – signs of an ideological shift, or commitment, a new identity. They wore badges. I’m a nomad, said these badges, and I believe in… Alas, the remains can’t talk. But they wore animal-style art – because animals had set them free? They were conspicuous with symbols of the steppe. It was a movement.

In circa one thousand BC. People were dropping out, at the time towns were in coalescence, and China wasn’t China yet but state-like tentacles were on the creep. Not likely, said these nomads-by-choice of Chifeng.

— Pierre Clastres, Society Against the State, translated by Robert Hurley, Zone Books, 1987. French original 1974

— Philip Carl Salzman, Pastoralists: Equality, Hierarchy, and the State, Westview Press, 2004

— Christopher Boehm, Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior, Harvard University Press, 1999

— Gideon Shelach, ‘Early Pastoral Societies of Northeast China: Local Change and Interregional Interaction during c. 1100-600 BCE,’ in Mongols, Turks and Others, edited by Reuven Amitai and Michal Biran, Brill, 2005. Gideon Shelach has a book out, that enlarges on his article: Prehistoric Societies on the Northern Frontiers of China: Archaeological Perspectives on Identity-Formation and Economic Change During the First Millennium BC, Equinox Publishing, 2009

Acknowledgement

I have never lifted so bodily from a scholar as I have from Gideon Shelach, when Mother Hoelun instructs Temujin in early nomad ideology (Of Battles Past, chapter 8). Although I lift from scholars, it’s usually disguised by the fact I have blent two or three or more together. It is because Gideon Shelach stands on his own, that my theft is naked.

December 17, 2012

Julian Rathbone: creative anachronism, political commitment

I haven’t before blogged book reviews, because that’s what Goodreads is for. But I might, now and then, with a novel relevant to me as a writer.

At the moment I’m sprawled at Julian Rathbone’s feet. What so excites me, I know, is certain nerves of kinship. I hasten to say he’s far more outrageous than me. But I’ll seat him here among my house-gods, who teach me how to write in the way I want to write.

The Last English King by Julian Rathbone, 1997

First: vividly written, feelingly, very high on ‘reality-sense’, atmosphere and peoplehood. With that, creative, unusual, and determined not to be your ordinary histfic. Also, fantastic writing. I didn’t skip once, through boredom with a description or thinking I know what the author’s going to tell me {or not until the idyll near the end. Right, I skipped once}. He knows how to craft a place-description so that even I, a poor visualiser, see. His description of people – and there I’m an aficionado – is super. He’s a student of gesture, an expert in body-language.

The early part is soaked in mood and the humanhood of Walt and Quint, whose journey together was the heart for me and knits the narrative: two odd travellers, cast out of life, in a way, in different ways. Their accidental friendship, very gently stated, is a joy. From there we look back on Walt’s past as a companion-in-arms to Harold, loser of the Battle of Hastings; while we travel to Constantinople and on through the Near East, see the world, the state of the world and discuss the future, too.

Walt’s nostalgia for Old (Anglo-Saxon) England is critiqued by Quint, and that nostalgia/critique goes on throughout the novel. I gave up English history years ago and had to brush up for this – not on the history so much as on perceptions of that history. Because I know he’s in a game with perceptions. The lines, I learn, are drawn thus: either England needed that vigorous Norman injection, or else England was an ideal place once, before the Normans came. I imagine that Julian Rathbone, being the sort of writer he is, addresses the historiography, the way history has been written, in ways that go over my head. If he deconstructs the characters of Edward the Confessor and William the Conqueror, I wouldn’t know – I don’t know what the image of them is. I can sense he’s engaging with interpretations of history but I’m not his audience there. I hear he upset people with his portrayals, and I’ll egg him on with that. In his author’s note he says William ‘saw to it that history was written the way he wanted it written’, and in the histories I know more about, I am only too aware that happens – and that propaganda then lasts down to the present day. Propaganda seems ineradicable, once in the record. I like his conscious tackling of our records of history. It’s a job historical fiction ought to do more often.

To this end he uses his anachronisms. He talks about them, too, in his author’s note: aside from the amusement, anachronism ‘serves a more serious purpose – to place the few years spanned by the book in a continuum which leads forward as well as back, to remind readers, especially English readers, that it was out of all this that we came.’ At commencement I thought that lame and wished he’d gone ahead and not tried to excuse himself. Later I started to see what he meant. After I’d read, for background, about 19thC heavyweight historians who have influenced our view of the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans. Because of that he’s not just writing about the 11th century. The anachronisms are often called arch, and I do laugh but if they were only for amusement I’d slam him. Quint quotes Yeats on Byzantium and what does that mean? That Yeats hit the nail on the head about Byzantium? I don’t know, but I enjoy the challenge to me, the ‘what does that mean?’

Edward the Confessor is a sad old soul. We first meet him as he faces the news he has six months to live, which helps our sympathy. He’s no hero and he’s no saint… they promise him sainthood, for political ends, and his kingship ends as his kingship began, used and abused. In the beginning, the thug of England Godwin set his ‘cock-quean’ son Tostig onto him, to entrammel him; after the Godwins change their policy and mangle that affair, he’s celibate for the rest of his life. As a king, even as a Norman-influenced king, he believes in non-interference: he sees that Anglo-Saxon England works. He is exhorted to make things more continental but he resists that pressure – even if he must enlist the Normans against the thuggish Godwins. I felt for Edward and he wasn’t such a bad old king. England blossoms under him.

Nostalgia seems to have won the argument by now and Anglo-Saxon England is/was a fairer, kinder, quieter place – even though its own politics has led to the crisis that lets the Normans in. The Witan is great, except the families in power determine what happens there. Harold knows he doesn’t need to be king – he runs England, like his father before him.

Nevertheless, after Harold visits the Normans, when he tries to tell the English what they have to lose – what Englishness is and won’t be – you believe in the urgency of his fight. When Walt tells the charcoal-burners, relicts of ancient inhabitants, who aren’t English, what their lives will be under the Normans. Will be, since we know the Normans win. What’s given as Norman is the later medieval system with its order, its suppression of disorder. Fair enough. Always thought I’d rather live in the 8th century than the 13th. A novelist takes sides, but – see beneath, for what the author has to say on that.

I like that he cares about societies before and after, that he cares what happened in history, even in 1066. If that’s writing with a political commitment, then – go ahead. Ancient fights for freedom, that lost and lost freedoms for us… there were others, and we need to care. If you care about your liberties now, let’s study the history.

William the Conqueror is Hitleresque. At first you think he’s a lampoon, but then Hitler looks like a lampoon. Soon the description is that of a serious psychopath. The word is used. Invented for him by Quint, who invents words, and Freudian psychology, such as I used to read about Hitler. So he was the Hitler of the day: how to get that across to us? Invoke Him, our equivalent. But Quint wants to talk about psychopathy, to us, across the distance, and he claims the right. He’s seen it. It’s just a matter of words. Perhaps Quint is a time-traveller. I’ll stop here as I’m rambling. I welcome his experiments.

Harold is decent but underdrawn. More might have been made of how he fits or doesn’t in his gangster family. Conveniently, the two brothers left to fight Hastings with him are also decent, much unlike the other brothers gone.

I read an interview with Julian Rathbone on the web – http://www.twbooks.co.uk/crimescene/Rathboneinterv.html – where he argues for a self-conscious historical fiction that knows it has an ideology or an agenda. Because every historical fiction does. Better – more honest – for that not to be unconscious in the writer. Perfectly true.

November 24, 2012

I hate genre

I haven’t written a post like this because, although I have very decided views (see title of post) I live in woeful, happy ignorance of the industry, the market and other words I do not like.

I like books.

There is a type of book I like most, or go to ahead of others: and I guess they’d have to be called, in the terminology, those that crossover or straddle the literary and genre (neither of which words I use).

Examples are easy. First off, Shakespeare: popular plots, art in the telling. Dostoyevsky’s novels always revolve around a murder. – If he weren’t a crime novelist he wouldn’t be my number one; it’s psych of murderers I got into him for. And things are thought difficult now or abstruse, that were popular in their own age: such as most of the medieval stuff I read.

I’ve been on a quest this year, to seek out high-art historicals and bludgeon my brains with them. When great novelists turn their hand to historical. I want to be there and see what they do – whether I understand it or not.

At a slighly less oxygen-starved altitude of art, I’ve found two or three of my ideal type this year, in historicals. The prize-winner is Robert Polevoi’s Port Royal, which is art about pirates; and Edith Pargeter’s A Bloody Field by Shrewsbury qualifies too. The depth of study of people’s heads – with battles and swordfights.

’Taint just historical I’m interested in; give me science fiction art. I always liked your arty science fiction, and arty fantasy, of course, has hundreds and thousands of years of tradition. The 1st of humanity’s writings were fantasy, weren’t they? and the writing of histfic, as I say elsewhere, is very much older than the writing of history.

I’d better not start on the publishing industry’s encouragement of genre. Mostly because I’m happy in my total pig-ignorance. If I ‘research the market’ – which I don’t do – I get depressed. My local bookstore has two stands for hf, side by side; one’s for girls, one’s for boys; you can tell by the covers, which are as clone-like as possible, and as for the contents – buggered if I want to find out. With a presentation like that.

That’s the sort of historical novelist I do not want to be. That’s why we escape the industry for the free air of indie (or so we hope and dream).

Down with genre. Up with art, high art or lower to give our intellects a rest. But my gods, Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, prove there’s no need to throw out your imaginative settings, your excitement. Pirates, of course, had as much subtlety of thought and sensitivity of experience as John Brown who lives at number five and led a dull life, frankly. So – I’m here to tell you – did Mongols. I hate genre books that deny these people their peoplehood. Oh, he’s a pirate, he’ll have three thoughts in his head. Oh, he’s a Viking, he can only fight, f— and f— (hey, I’m bad at crude. Don’t worry, my people swear when they have to). I get dead sick of two of those fs, and the third, too, unless he thinks and feels.

If we must have genre shelves, put Shakespeare and Dostoyevsky on them – where they belong, and widen the concept. Give us Gilgamesh and Homer to take as examples, and not the bestseller lists, that’s like in-breeding or reductionism, I don’t know what, but it’s bad. ‘Genre’ closets, closer and closer, and we hear or know of stifled authors, who have been locked in and lose their art. In the industry, I believe, authors are told to study the bestsellers in their line. How bad an idea is that?

But then, art+industry=a marriage made in hell, and let’s not pretend otherwise, even if we have to live together. Author, know thine enemy; be polite to him if you’re under contractual obligation. I don’t know. I’m an indie who boasts about my ignorance. Perhaps I ought to have stuck to ‘books I like’, but what are blogs for?

November 19, 2012

Near misses

Whenever you pick covers, there are those you almost chose or wish were possible to you. So I just have to exhibit a few great images I didn’t use.

Whenever you pick covers, there are those you almost chose or wish were possible to you. So I just have to exhibit a few great images I didn’t use.

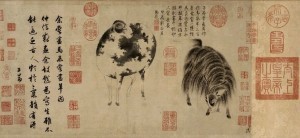

For a book titled ‘The Sheep from the Goats’ and to do with Mongols, the above was an obvious resort. It’s quite famous: painted by a Zhao Mengfu in the Yuan Dynasty (that’s the Mongols in China), it’s thought to be a comment on the question, whether or not to work for the Mongols. There were Chinese scholar-officials who refused to serve under the Mongols and kept an ivory-tower aloofness; others argued for useful service, yes, even with barbarians in charge. After ten years in the ivory tower Zhao Mengfu agreed to join the court of Khubilai Khan, and defended his stance against the criticism of peers. His stout, stuffy sheep feels lofty next to his combative, more energetic goat.

Another goat I found – in case you’re keen on goats. Here’s a totem-style Yule Goat from Gotland, an 18th-century farm now a museum.

Getting away from goats. When I began to think about animalistic masks, I found this Swiss carnival mask, in the Museum Rietberg, Zurich.

It’s great, but we went to Africa instead. I’ll have to post on the African masks, but it’s a subject new to me.

And here’s what else I found on David with the head of Goliath:

A second Caravaggio

A Titian

And one by a certain Valentin de Boulogne

I did notice, on my search, most Davids were too dainty, too fastidious to touch the head, never mind haul it by the hair, as Caravaggio’s does: they posed beside it with their hands off. Caravaggio, of course, knew about the seamy side of life, wasn’t a stranger to blood. No-one else even thought to try an expression on David’s face like to my chosen Caravaggio.