Richard Goodman's Blog, page 8

May 12, 2024

Wish you were here

“Mothers are all slightly insane,” Holden Caulfield says at one point in The Catcher in the Rye. I always knew what he meant. It was never a quote that I puzzled over. In five words, he got it.

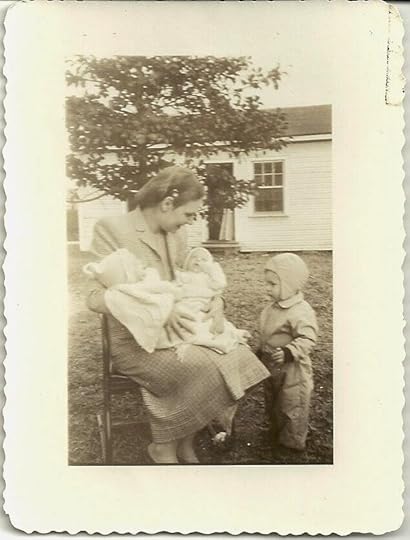

My mother holding me, age 7 weeks

My mother holding me, age 7 weeksYes, mothers are all slightly insane, some more slightly than others. They’re insane because they can never be certain, ever, that their children are completely without harm. They are on some kind of alert twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year. Some part of them never sleeps. You can’t be that attentive and worried for that long and not be slightly crazy. Combine this worry with powerlessness—as soon as the boy or girl steps out of the house (out of the room, actually), their mother can’t do a thing to protect them.

Holding her twins with me observing. She had three children within eleven months.

Holding her twins with me observing. She had three children within eleven months.I think of my own mother, of her difficult life, and of her living alone after her divorce. For years. I think of all that she tried to do with that ache and pull toward her children. I think of her carrying that ache of loving me and that love unrequited, and how can you stand that day after day year after year? She used to say to me, “I get lonely for you, Richie.” I think of her probably feeling she hadn’t been a good mother, and how that must have devastated her after worrying about us so deeply and so continuously. I think of her bright, sharp mind, love of writing and reading and of her unblemished soul. I think she did the best she could. Now that I have made my own big mistakes as a father, I see this so much more clearly.

In Old Greenwich, CT, sometime in the 1970s.

In Old Greenwich, CT, sometime in the 1970s.It’s too late to tell her that I love her. I tried to do justice to her memory in a piece called “The Wheaton Girl.” She went to Wheaton College. “The happiest days of my life,” she told me. I doubt she’d like it, even though I wrote of of her intelligence and of her kindness. She didn’t want her weaknesses exposed, and who would? I wrote another piece about watching her hang out the wash when I was a boy. Still not right. I’m not here to say anything silly like, tell your mom you love her before it’s too late. (Or maybe I am.) I’m just here to say to you, Mom, you deserved better. But I can’t. I think about you every day. I wish your life had been easier. I hope you’ve found peace. Happy Mother’s Day from your son.

The only time my mother saw my daughter, Becky.

The only time my mother saw my daughter, Becky.

May 10, 2024

My dog has fleas. So do I.

We returned from France late last night, jetlagged and tired. The pets were not there. They were being taken care of somewhere else while we were away. My wife, Gaywynn, sat down on the couch, weary, only to jump up a minute later and cry out,

“Fleas! We’ve got fleas!”

She drew my attention to her ankle. Little dots were moving about on her skin.

Fleas? But our dog and cat hadn’t been here for two weeks.

“That doesn’t matter!” she said, extricating flea and after flea and then peering at the couch from which she sprang. “When they bite the dog or the cat, they die because of the medicine we give them. They’ve been waiting for something to bite into.”

“I guess that’s us,” I said with a smile, relieved I hadn’t been invaded, like my wife.

Then I felt something moving on my leg.

“Hey,” said, looking down at my ankle area, “are those fleas?”

Gaywynn came over, looked closely at my ankle.

“Yes.”

“What? I’ve got fleas?!?”

“On the other leg, too.”

Just back from Paris, that most elegant city, and we both had fleas.

Welcome home.

Gaywynn immediately went into action. Fatigue or no fatigue. After she had divested herself of all the fleas she could find—we’re not talking hundreds here but maybe six—out came the vacuum cleaner.

“They’re so small!” I said, trying to pick one off.

“About the size of a breadcrumb.”

I kept finding them. No wonder they’ve been so successful, evolutionarily speaking. They’re tiny, hard to kill and can jump like Olympians. You have to give them credit—as if they cared. Just read this, from Wiki,

“Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about one-eighth inch long. They lack wings; their hind legs are extremely well adapted for jumping. They can leap 50 times their body length.”

That’s quite a CV. If I were an employer, I’d hire them.

Exhausted, we finally went to bed, somewhat fearful that fleas lingered, perhaps in the bed somewhere, but unable to care because we were so tired.

The next morning, fleas were still about here and there. Gaywynn went into full Shaker mode, stripping the bed, putting sheets and towels in the washing machine, vacuuming—again—mopping and researching online for the best possible sprays and smoke bombs to rid us of these pests forever.

I found a few fleas on myself now and then throughout the day.

It struck me at one point that before I met my wife, finding fleas on my body would have been a personal disaster. I would have been shocked, disgusted, angry and petulant about the whole experience. That’s me. That’s what I’m like. About a lot of things. Not very admirable, but by this time, age 78, I know who I am.

Now, though, with my wife, fleas, though not guests I’d invite home every day, are a slight nuisance, no more. In fact, they are the basis for an improvised farce we write as it happens. It’s a kind of slapstick, and our home is a theater where this one-act has its debut. The dialogue is crisp and the action brisk. It’s actually quite entertaining.

“Fleas!” a comedy in one act, starring Gaywynn and that guy who you might have seen in the long-running melodrama, “The Whiner.”

Someday, Samuel French might publish our farce about fleas.

Someday, Samuel French might publish our farce about fleas.This flea invasion is something we experienced together, jointly dealing with it, in that communal way one deals with small inconveniences like leaks, broken dishwashers, clogged gutters and such when married.

In short, this flea I dislodge from my ankle reminds me that I am, thankfully, no longer starring in a sometimes trying one-man show.

May 4, 2024

Nature writing workshop! May 20-June 1! On-line!

Please join me for an on-line nature writing workshop with Maine Media from May 20-June 1.

We’re inspired by the natural world. Let’s convey our thoughts and feelings about that with passionately-chosen words.

Just go here for more information and for how to enroll:

https://www.mainemedia.edu/workshops/...

See you there, I hope!

Richard

May 2, 2024

Speaking French in France

My wife and I have come to France for our honeymoon. We spent the first days in Paris, went to Rouen for a few days, and returned to Paris for the last four days of our trip.

I have spoken French as much as possible during this trip. It has gone reasonably well. I never took French in school. Spanish was the language I tried to learn in high school. I learned whatever French I know when I lived in a small village in Provence for a year many years ago.

So, this trip I dusted my French off and tried it on, like a garment that had been in storage in the attic for a long time. Would it fit? Or would it feel awkward, too small, as it were, ungainly and awkward?

French is an incredibly difficult language to speak correctly. Some words and phrases seem to have been created by a linguistic sadist. In any case, speak it I did and have been.

I have made myself understood. Not always, to be sure, but for the most part. It’s when I get tired from speaking, listening, concentrating, and so on, that the tongue begins to rebel and things get slurry and I get those tilted-head looks that say, What-are-you-saying? Other times, though, I can actually communicate.

If, like me, you’re not fluent in French but, let’s say, somewhat capable, then you have to work hard when you speak and, especially, when you listen to the person you’re speaking to. Some words I know, others come to me after a kind of tape delay, others I guess at and still others I absolutely don’t know. A lot of what I do is in context. If I’m in a boulangerie, a store that sells bread, I’m pretty sure the conversation won’t be about spark plugs or shoes.

It all goes very fast, of course. French is a language that the French love to speak rapidly, sometimes like a comet, and I often find myself racing to catch up, trying to catch words that are flying off or picking up phrases and words off the ground that have been hurtled off.

Then there is the French tendency to use, on occasion, English words as part of their speech. I remember the first time I heard a Parisian say, “Passez un bon week-end” to someone. “Have a good weekend.” I racked my brain for what “week-end” meant, thinking it was a French word—why would the proud French employ an English word?—until, finally, I had the ah-ha moment. That throws you off.

Some phrases mystify me. Twice in stores after asking for something, the person behind the counter said, “Avec souci?” Befuddlement. The word souci means “care” or “worry.” I knew that. One well-known French expression is sans souci—without a care. So—what the hell is this? Later, I looked it up, and it’s a phrase that means, “Anything else?” So, I encounter this kind of thing.

My ability and accent waver in quality. Some days, like a baseball pitcher, I perform better than others. Who knows why? Some days my accent is passable. Other times, I sound like I’m talking underwater.

I think speaking any foreign language is a kind of magic. What I couldn’t understand before, that seemed pure mystery, is now like a locked door I’ve opened. Now I have access to what’s inside.

I have even made a few jokes in French. And gotten a few laughs.

In a store in Rouen with my wife, the cashier asked us, as we were about to pay for something,

“Est-ce que vous avez une carte de fidélité?”

Meaning, “Do you have a loyalty card?” This is the French version of our membership card, the sort of thing you get at a coffee shop that will give you a free cup of coffee after so many you pay for. It’s called a fidélité.

“Non,” I tell her, glancing at my wife affectionately, “mais je suis fidèle.”

“No, but I’m loyal.”

She laughed. Well, smiled, actually.

Making people laugh or smile in another language makes you feel like you can do most anything.

I’ve also figured out a way to deflect the Parisian tendency to speak to you in English, even when you first speak to them in French. This was not the case in Rouen, where people seemed quite happy to stay with French. Rarely would they reply in English. I’m sure they could tell I wasn’t French. That was easy to see. But they went with it.

Not so in Paris. Not as much anyway.

Yesterday, we were on the Left Bank, and we stopped at a cafe. I ordered some coffee and tea. In French. The waiter came back with the coffee and tea and said to me, “Here is your tea.”

I looked at him and said, “Vous parlez bien l’anglais.” “You speak English well.”

He nodded, blushed a bit. Then he paused. I could see him thinking. What has just happened?

April 25, 2024

Lessons in Rouen

There are three names that will always be linked to this city in northwest France where we are staying for a brief visit.

The first is Joan of Arc, who, at nineteen, was burned at the stake for heresy in Rouen in 1431.

The second is the author Gustave Flaubert, who was born in Rouen in 1821 and grew up there.

The third is Claude Monet, who executed multiple paintings of the facade of the city’s famous cathedral at different times of day in different light.

All three revolutionaries, each in their own way.

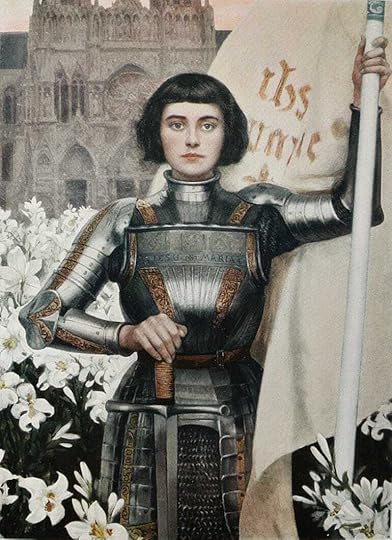

Artist’s rendition of Joan. Note illustrious cathedral in background.

Artist’s rendition of Joan. Note illustrious cathedral in background.Joan—well, she’s one of the patron saints of France. Now that she’s dead. It was France that killed her almost 600 years ago. Do you know that one of the reasons she was convicted of heresy was because of “the wearing of men’s clothes?” A grave sin. In 1920, they made her a saint. I have a feeling she would have traded that honor for a few more of her just-nineteen years of life.

Flaubert, who lived most of his adult life near Rouen, was also put on trial. Or, rather, his book, Madame Bovary, was, on charges of immorality. (That happened in Paris, so we can’t blame Rouen.) He and his book were acquitted. After the trial, sick of the world, he vowed to go home and never write again. Luckily for us, he did write again. Now, of course, he’s a literary saint.

Gustave Flaubert

Gustave FlaubertMonet’s art was, at first, rejected by the establishment. Speaking to that, I have just seen an exhibition at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris called, “Paris 1874: Inventing Impressionism,” in which Monet plays a significant part. As the museum puts it,

“On April 15, 1874, the first impressionist exhibition opened in Paris. ‘Hungry for independence’, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro and Cézanne finally decided to free themselves from the rules by holding their own exhibition, outside official channels: impressionism was born.”

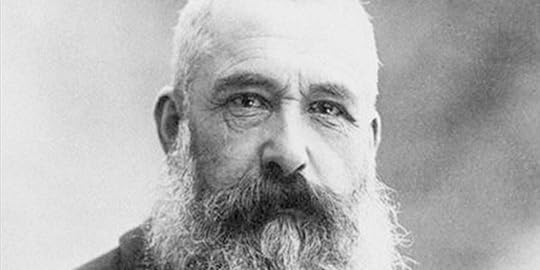

Claude Monet

Claude MonetOne fascinating aspect of this exhibit is that they have an entire room dedicated to the paintings that were selected by academics for the official exhibition in Paris that year. I didn’t recognize a single name. The paintings look like a Saturday yard sale.

These three people, closely associated with Rouen where we are staying, remind me, once again, that what you need to persevere in life is, above all, courage.

And, I suppose, its first cousin, conviction.

I know I don’t have Joan’s courage. Not even close. I don’t have Flaubert’s talent or his unwavering discipline and devotion. Monet? Well, not only can’t I paint, I can’t even draw a decent stick figure. Even if I could, I wouldn’t come close to his art.

Never mind. I can take inspiration from their example. I can be inspired by how they lived.

This is one reason why I travel. To be inspired.

April 18, 2024

Water Island days

There were five of us—Bruce, Kerri, Pamela, Nancy. And me. We rented a house on the Great South Bay on Water Island, with that sweeping, faceted water right before us. From our deck, the sun set in wide dying flourishes every evening. The ocean, on the other side of the slim island, was a two-minute walk from our house. The beach was one link in the grand line that stretched along the southern flank of Long Island to its very tip. We were on Water Island, a small enclave that was part of Fire Island, just 50 miles from New York City—but another world entirely. It was a kind of miracle, really, that this dreamy place was so near.

Our house. We kept the windows and doors wide open. The clean scents of the island entered and left as casually as we did. Every so often, a light, brackish breeze from the Great South Bay wafted through. Out front, there was Rosa rugosa, with its little beach bum flower that always looked disheveled, as if it had just gotten out of bed. When you put your nose to it, you received a narcotic jolt of rose.

Light everywhere.

If you walked into the house late in the morning, you would encounter the five of us, like a curtain going up at the beginning of a play, in various places around the spacious single room. Kerri on the easy chair with his sketchbook, drawing, but listening. Nancy on a bar stool, slim legs crossed, glasses perched in her hair, laughing. Bruce, standing before the island counter near the open kitchen chopping or slicing something. Me, on the other couch, trying to make everyone laugh. Pamela, just getting up. She’d make her entrance groggily from her bedroom as late as eleven. She slept in a long dark T-shirt down to mid-thigh. She’d stumble toward the coffee.

Bruce, with a friend

Bruce, with a friend“I hate mornings,” she’d say. “I’m a real bitch. Stay away from me.” Then a half-hearted rendition of her two-beat laugh. “I’m warning you. I’m serious. I’ll rip your head off.”

She’d pour some coffee, take the cup to the couch and sit. She’d reach for a magazine with her free hand and begin reading. Like Nancy, no make-up. It was a privilege to see them both unadorned.

We’d sit and talk. There was never any shortage of subjects. All of us had our New York lives. Bruce was a lawyer working part time. Nancy worked for a man who advised hospitals on how to streamline their costs. Kerri worked for a jewelry designer. Pamela did various things to get by and probably had some money coming in from her family. I was an advertising copywriter. None of us were married. None of us had children. None of us had any real obligations. Our parents were still healthy then. This happens only once. I know that all so well now, reaching back.

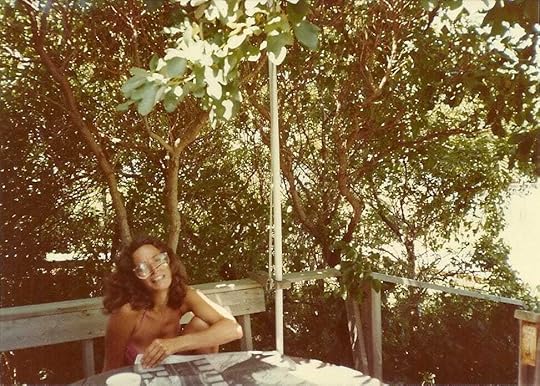

Pamela

Pamela“Bruce, why don’t you become a chef?” I said. It was clear he loved to cook.

“I would,” he said, “if I were good enough.”

“Will you ever practice law?” I asked.

“I sincerely hope not,” he said. He had his law degree from Columbia.

“He’s been offered a job,” Nancy said.

“Oh, really,” Kerri said with arched eyebrows. No one could arch eyebrows like Kerri.

“At the Bank of New York,” Nancy said. “They love him. They want him to work full time,” Nancy said.

“Are you going to take it?” Kerri said.

“You should,” Pamela said. “You’re so brilliant.”

“I hate the law,” Bruce said. “I hate everything about it.”

“But,” I said, “all that education you have.”

“A complete waste,” Bruce said.

“You don’t mean that,” Pamela said.

“Yes. I do,” Bruce said. You could see he didn’t want to hear any more about this.

Nancy on the deck

Nancy on the deckIt was like a family discussion. It was a family discussion. We were a family—the first real family I ever had. I had the beautiful security of being part of other people’s lives. This was something I hadn’t ever experienced. A sense of belonging. Here, in this house, on a summer morning, with these four people, with Kerri, Bruce, Nancy and Pamela, I felt us against the world. I felt—perhaps not in any way I could articulate—that now I truly had a family. And a sense that what I lost, or never had, could be found.

I was grateful then. I’m grateful now.

“Well, I have some news,” Kerri said. He said in his bombshell-dropping way, calmly, with a little sing-song.

“What, what?” Nancy said.

“This better be good,” Bruce said. “I’m in the middle of slicing carrots.”

“I think I’m in love.”

Even Pamela perked up.

Nancy screamed.

“Who? Who is it?” Pamela said, leaning forward on the couch.

“Well—you’ll love this. He’s an orthodox Jew.” Kerri let off a peal of machine gun laughter.

“Who is he?” Nancy said.

“Yes, how did you meet this…rabbi?” Bruce said.

“He’s not a rabbi,” Kerri said. Laughing. “He works for Saks.”

Kerri

KerriKerri had a look on his face. The look of someone who had found what he was looking for. That he hadn’t been able to find until now.

We were all exuberant, happy for him. One more of us had gotten there.

The morning unfolded, never lacked the energy of friendship.

Then, at last, someone would call out, “I’m going to the beach. Anyone want to come with me?” The second part of the day would commence. We’d finish whatever it was we were doing. The beach and the ever-surprising ocean was waiting.

We’d gather towels and chairs and straw bags with water and books and lotions and hats. Then, one by one, we’d make our way down the now-warmed narrow boardwalk to where it ended and to where the sand began.

Us.

April 12, 2024

Mulberries

We have two mulberry trees in our yard where we live in south Louisiana.

Our trees are bearing fruit now, overflowing with it, the smaller tree literally bending over to one side, like it’s bowing to someone, its hands (branches) touching the ground.

The supplicant mulberry tree

The supplicant mulberry treeThere are three kinds of mulberry trees, I learned—white, red and black. Ours is red, Morus rubra, with the red fruit ripening to deep black. The ripe black fruit looks like an elongated blackberry. It’s firmer than a blackberry, but, despite the similarity, the species are not related. Its taste is subtle or, less kindly, hardly exists.

The tree in front of our house, the smaller, has by far the most fruit, is the most fertile. We’ve picked it at least five times, and it’s still heavy with fruit. We—well, my wife—has made mulberry jam, a mulberry crumble and has frozen many mulberries from these harvestings.

Ripening mulberries from our tree

Ripening mulberries from our treeWe’ve picked them often with the little girl who lives next door, a Cajun girl, seven years old. She adores my wife and comes to our house every afternoon after school to visit and stay as long as we’ll allow her. She will negotiate that departure time with us, trying, as it gets dark, to eke out a few more minutes if she can with highly inventive pleas. She loves helping my wife clean, cook, paint—anything.

And pick mulberries. The other day, we spread a tarp underneath the larger mulberry tree. I got on a ladder and shook the branches, so the ripe berries would fall, making it easier to glean them. This delighted the little girl, whose job, self-declared, was to gather all the fallen berries into the middle of the tarp. We will miss her dearly when we go away for the summer.

Our dog, Manon, surveying the mulberry tree in our back yard

Our dog, Manon, surveying the mulberry tree in our back yardThe other day I read some words by the U.S. poet laureate, Ada Limón. She’s compiling an anthology of nature poetry by American poets. She said that these poems “make me want to pay attention to wherever I am right now, to look deeply at what’s around me, and not miss it.”

So it is with mulberries and picking them with my wife and the little girl next door. I never had mulberries in my life before I moved to this rural area of Louisiana. The tree’s range is wide, though, covering most of the eastern United States. I’m not sure why I never encountered them before, but there you are.

Ripe mulberries fallen to the ground in our back yard

Ripe mulberries fallen to the ground in our back yardSo I think of Ada Limón and what is around me. I see mulberry trees and the fruit they bear.

Trees bearing fruit. A reliable event. Perhaps. If I’m really aware of what’s around me, though, I have to be aware that mulberries may not be in our future, the way things are going. Last summer in Louisiana, the heat was horrible, like living in magma. Every single day during the month of August, it was 100 degrees or above—one day reaching 110 degrees. That heat, combined with the debilitating Louisiana humidity, was too much. We hardly went outside the entire summer. Some of our trees could not withstand that furious assault and died.

Not the mulberry trees, fortunately. For now, at least.

My mind wanders when I consider this. I think about the people I know who are basically accepting of whatever happens with regards our imperiled environment. “What can I do to make a difference?” one person said to me. “It’s probably too late anyway.”

How do we know if it’s too late?

I will die, and with that, there will be no more mulberries and mulberry picking for me. That does not mean, though, that there will be no more mulberries and no more mulberry picking for the little girl next door. I fervently hope there will be.

April 10, 2024

Writing about nature starting May 20!

Please join me for an on-line nature writing workshop with Maine Media from May 20-June 1.

We’re inspired by the natural world. Let’s convey our thoughts and feelings about that with well-chosen words.

Go here for more information and for how to enroll:

https://www.mainemedia.edu/workshops/...

See you there, I hope!

Richard

April 4, 2024

Rick Stolorow

Fellow prep school student. Roommate at the University of Michigan, freshman and senior year. 1964 and 1967. Yes, many moons ago.

A few days ago, I got word that he’d died. Struck by a car while walking. He was 78.

I hadn’t seen him in 30 years. He was reclusive. Lived in Rhode Island with his girlfriend, but did not communicate. I tried. Reached out. Many times. No response.

Taught me so many things. We were a team. The two ridiculous brothers. Going to parties at U of M. Smoking dope. Inhale. Cough. Pass that joint. Whew.

We did bits at parties. Anything for a laugh. He had deadpan delivery. The desperation for a response became his—our—trademark. Yes, he pulled a plant from a pot and placed it on his head once. Expressionless. A friend who was there still laughs about it today.

Competitive. Both won awards at U of M for writing. Would-be writers. Maybe. We both had domineering fathers. Lots to talk about. We did.

Freshman roommates the University of Michigan. We’d stay up for hours debating the existence of God. Such urgent inquisitiveness. Pondered other Big Matters.

That freshman year, I was sinking into a dark depression. He was seeing a psychiatrist, and his man recommended one for me. Life saver.

We roomed again together senior year. We had a second floor apartment in Ann Arbor, perfect for rabble rousing. We did. Many tales I could tell.

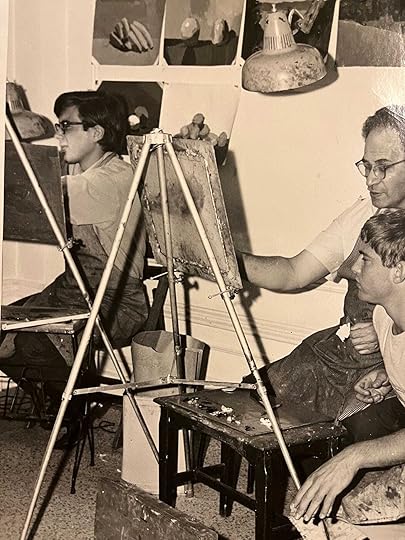

We spent a summer together—was it 1965?—in New York studying painting. An urban adventure with an odd, larger-than-life instructor on the Upper West Side.

Rick, left, painting. New York City. Summer. Possibly 1965.

Rick, left, painting. New York City. Summer. Possibly 1965. Took him home with me two or three times to St. Clair, where my mother lived. Small, insular town with bored semi-delinquents waiting to get drunk and cause mayhem. Rick enraged one of them, last name Bankey, by speaking too long to his girlfriend. Rick, trying to calm Bankey down, urgently imploring, “Now, Sparky, relax. I know you’re angry, Sparky….”

Laughed about that for years.

He was a sweet man, a kind man, a complicated man.

We both graduated, went separate ways. Saw him in Cincinnati years later where he was living. His girlfriend had a child who Rick was most caring toward. Then, more years later, shortly after my daughter was born, in, I think 1994, or so, he came to New York with his girlfriend. Dropped by our apartment for an hour or so. He told me he was writing and publishing here and there. Then he left.

That was that. I never saw him again. Perhaps there was one letter, maybe two. Then, nothing. I tried, but he had a way of living, and that was to be respected. As recent as a year ago, I tried to find an e-mail address for him. No luck. So there is a great gap in his life I really know nothing about. That happens.

I always looked for his work. He’d turned to poetry. I found some of it on-line. I liked and admired it very much. Still do.

Here is a poem he wrote, published in Apple Valley Review:

Otter Lake

by Richard Stolorow

Come up old man from the green water—

I know you are there. When I dove

in off the back square end of the rowboat

you held the oars. I was a lonely boy

given to fits of anger in a noisy world

and when I entered the cool sleeve

of Otter Lake there was no sound

among the soft shafts of light

no human motor in the mineral water.

I was home, the other home, where

you are now, my dad, I know.

I take the boat out stroking

to the lake’s blue midst, once my

boyhood tennis shoe day. There is

a slight breeze, enough to push

a dingy sideways over the surface

where I place my lips, waiting for you.

There is a fine, generous obituary that was published a few days ago. I would be happy if someone wrote something like that about me when I’m gone. It begins,

“Rick Stolorow, of Riverside, RI, walked quietly and with intention.”

I hope, somewhere, Rick, you continue to walk quietly and with intention.

March 29, 2024

Spending Easter alone

I think everyone who believes or thinks they believe or who may believe, should spend at least one Easter alone.

I am struck by how much of Jesus’ life was spent alone. Right from the start. He’s baptized by John the Baptist and then immediately heads to the desert to spend 40 days thinking and fasting—alone. That is followed by a series of temptations by the devil himself that do not succeed. From this encounter come two famous phrases, “Man does not live by bread alone” and “Get thee behind me, Satan.”

Jesus proceeds to round up his twelve apostles, the first being brothers Peter and Andrew, fishermen both. He then begins preaching and making miracles, curing people of leprosy and palsy, casting out devils, not to mention raising the dead. There follows the Sermon in the Mount and other familiar events.

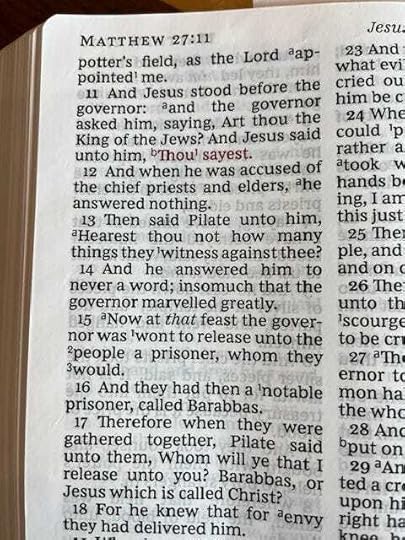

Then he’s betrayed by Judas and is turned over to the authorities who find him to be a dangerous rabble-rouser. Pilate questions him, and, except for one brief response, Jesus is silent.

And he’s alone. There’s no one there to defend him, to counsel him, to simply be there with him. No one standing beside him. These last hours are one of a man completely alone. He was mocked, spit upon. All those people who marveled at his miracles and were so taken by his teachings—not there. The crowd that is there is hostile; they cry for the release of the thief Barabbas and demand that Jesus be crucified. Pilate literally washes his hands of it all, and Jesus is, as well all know, crucified.

Even dying, he calls out that he has been forsaken by his father, left by himself.

Many people fixate on what must have been an agonizing death, but I always felt the extreme loneliness of Jesus’ final hours. The agony of being utterly alone in his suffering.

One Easter, I was in France. That would seem to be not a bad place to be, and it surely was not. But I was alone and lonely, and when Easter came around, I felt a kind of kinship to that weekend, and especially to Good Friday, that I wouldn’t have felt in a communal situation, paradoxical as that may seem. My aloneness was mirrored by Jesus’. It was embraced.

We are all alone at one time or another in our lives. Sometimes, that is fine, but on other occasions, it’s very hard to bear. We’re alone and we’re lonely, and that can be a strong, forlorn ache. To be totally alone. No one to have our back, to take our part. My aloneness gave me a deeper understanding of Jesus’ trials. I felt closer to him. Spending Easter alone widened my perspective on what happened to him.

Today, Good Friday, I think about my poor cousin, in a hospital room, plagued by demons, afraid and trembling and feeling hopeless. Family visit her, console her, do all they can, but she is hours from home, and, mostly, with strangers. I think about her. I want her to feel she’s not alone.