Richard Goodman's Blog, page 4

February 20, 2025

A kayak ride in Maine

At 6:30 a.m. on a July morning, I pull the heavy, sleek kayak across the grass toward the water. The grass is damp, and the kayak glides surely to where the lawn meets the rocky beach. I have to lift the kayak by the cockpit rims and haul it to the water some fifty feet away. I step cautiously over rocks I can’t see—the kayak’s bulk obscures my view—until I reach the water’s edge and set the kayak down with a splash.

I’m on an island in Maine. The amber sunlight spreads across the flawless water in front of me. I’m wearing a chest-tightening life jacket, baseball cap, swim trunks and flip flops. I ease myself into the kayak, always a touchy maneuver with great possibilities for farce. Once installed, I push the kayak away from the shore with the paddle, digging the end into the sand for leverage. Then there is that space shuttle-like moment when the bottom is freed, and the kayak begins to glide off into the water.

For glide is what you do in a kayak. You glide across the water like some sort of nautical skater. Newton seems wrong here, as the kayak’s lengthy reaction to my paddle’s action appears far more extensive than equal.

The world is still.

Isle of Springs, Maine, 1995

Isle of Springs, Maine, 1995There are a few lobster boats moving from trap to trap on the water in the sunny distance. The sound carries so well, a boat a mile away can seem like it’s bearing down on you. I’ll hear a lobster boat’s motor and crane my head around in slight worry only to see the boat is far away. I can never get used to this disparity, and it makes me feel a little foolish.

I paddle the kayak along the edge of the island. Above, on a branch of a bleached, skeletal pine, an osprey perches. As I approach, it sees me and begins a high, relentless screech. These noble birds, with their haughty Medici profiles, are a welcome presence. With their superb fishing skills and fierce dedication to their young, they make me want to be a better human with whatever resources I’ve been given. They are proud, hard-working birds, and I want to be proud and hard-working, too.

I paddle away from the island, which is now fully bathed by the early sun. The smell of the water enters my nostrils. There is nothing in the world like the scent of Maine coastal salt water. The water is limpid, briny and wonderfully alive. It’s so pure it almost seems drinkable. Yes, it’s cold, and I feel the electric pins and needles when I swim in it—when I dare. But as a kayaker I only dip my hand into it from time to time for cleansing and renewing, and it’s Ponce-de-Leon refreshing.

When I am out riding in a kayak, I feel like the first man. I feel as if I’m seeing these sights before anyone else has ever seen them. That I am the first person to see these dark massive rocks and quiet tall spruces. I think this has a lot to do with the point of view of the kayak. It’s a stealthy and almost noiseless experience. Its purpose seems discovery. It’s also easy in Maine to feel this way where there are hundreds of small, uninhabited islands that you can paddle by without seeing a soul. It’s easier here to pretend you’re Magellan, discovering.

I paddle east. I see a seal’s head break the surface of the water. Surprise and delight from me. There is water everywhere, deep and cold, but for some reason, I don’t think of seal being underwater until one appears. Seals are curious, and, if not exactly friendly, are often unafraid. If I’m lucky, one will surface near me, probably having seen the bottom of my kayak, and will swim by to have an assessment. It’s almost impossible not to grin when I see one of these sleek, alert, graceful animals. Today, though, this particular seal is staying clear of me, and I can’t make out the details of its face. It is a seal, though, and I feel lucky having seen it. It’s as if I am in a state of grace somehow.

I kayak hoping to see animals. I have in the past seen weasels making their way amongst the rocks on shore. They slither along adroitly as if they had designed the rocks for their movement. Weasels are highly disparaged, but no animal consciously does harm. I have also seen bald eagles in the huge nests high above, and loons, and little ducks I can’t identify and, at the water’s edge, a lone Great Blue Heron.

Rockport Harbor, Maine, 2021

Rockport Harbor, Maine, 2021Now, as I paddle around the tip of the island and make my way toward the modest dock area, something new: a huge sturgeon leaps out of the water not ten feet away. Even with so brief a glimpse, it’s absolutely unmistakable. Its long, antediluvian body with its notched spine and blunt snout looks like no other fish. It crashes back into the water and disappears. Because of the quick, explosive nature of the sight, it leaves me wondering if it actually happened. Wondering, too: do fish jump to warn us, to have a look, to show off? Another mystery that doesn’t need explaining. What a creature I’ve just seen! For the first time I wish there were someone with me to share this moment.

My shoulders feel strong as I paddle, in that steady switchback motion of a kayaker. The day is getting warm. I’m sweating lightly. I take a scoop of water and splash it on my face. It braces my whiskers. It’s delicious. I paddle past the dock area. No one is there, just the tethered boats, empty and ready. I continue around the island, slowly and steadily.

My mind rejects anything complex. It’s at this moment that the ego subsides. I’m grateful for its diminution. The clarity of the wisdom of these rocks, trees, this sharp cold water and these animals shrinks my importance. It’s a burden, this presumptuousness I’ve learned being human. Nature, of course, has no such concern. Nature has no ego. For a few blessed moments out on the Maine water, I join her.

I increase the power of my stroke, and the kayak surges like a racehorse. Muscle and mind work flawlessly together. I paddle around the northeastern point of the island and head for home. I see the little cove where I began this ride. I slow my paddling then stop, not wanting the ride to end.

The kayak drifts ever so slowly toward the little beach. It finally touches with a small, sandy crunch. I awkwardly get out of the kayak, right foot first, then left. I pull the kayak up on the beach. It feels unnatural to be walking on land. Am I really terrestrial? I’m not so sure. I take a deep breath and look back out onto the water. Most of the island is still asleep. I continue savoring my moments traveling on the water as I become, reluctantly, a creature of the land once again.

February 14, 2025

Lavinia

“Come in,” she said, waving me in with a low hand. I caught the door, and she turned around in a measured pivot, giving me her back and talking as she walked toward the living room.

“I don’t know why you want to see an old lady like me,” she said as she hobbled away from me. I could see she was bent over. She had that smallish hump in her back many old people have, and it seemed to weigh on her heavily.

I laughed self-consciously. I didn’t have a reply. I followed her, experiencing all the excitement, nervousness and tension you feel when you give yourself over to a new person.

I was being polite, too, trying to appear well bred. I wasn’t sure how to do that in a brief walk from her foyer to her living room. I decided walking softly was the best way. I was also trying to take everything in. Her apartment was modest, but pleasant, though somewhat dark. The window in the living room faced to the back of her building, an unglamorous structure on Greenwich Village’s Eight Street, between Fifth Avenue and Broadway.

“Sit. Sit,” she said when we were both fully in the living room.

Her eyes flickered toward the only couch in the room. She sat in a tall dark chair behind her desk and immediately lit a cigarette.

“So, you’re Mr. Goodman,” she said, as if by saying my name things could now begin.

“Yes, but please call me Richard.”

“All right,” she said. I waited for her to return the gesture. She didn’t. She took a long drag from her cigarette and then tapped the stalk on the ashtray. Later, after I had visited her a few times, I asked her if I might call her by her first name, Lavinia.

“Of course!” she said. “Such a silly name, isn’t it?”

“Well, no….”

“Oh, it is. It’s Latin. The name of some third-rate Roman goddess. I think Mother had just read Bullfinch’s Mythology when she had me. I’ve never liked my name.”

Her full name was Lavinia Russ. Even now, when I put it down on paper, she emerges from the fog of time to greet me once again. Lavinia. La-vin-i-ah. A honey-sounding name.

“They,” she said, waving a hand somewhere, “they didn’t say too much about you. But you look like a nice man.”

At first, I had no idea what “they” she was talking about. I looked wildly in the direction of her extended hand for a clue. Suddenly, I realized that they were the Village Visiting Neighbors, a nonprofit organization in New York City’s Greenwich Village. They brought people together with older people who needed errands done for them, or who simply wanted someone to visit them to quell the loneliness. It was they who had matched us together. In all the time I knew her, Lavinia never spoke the actual name of this organization. So, here I was. On my first visit.

Lavinia

Lavinia“Well, I want to warn you,” Lavinia said as she took a quick puff of her cigarette, “I’m losing my mind.” She cast a half glance my way but avoided actually looking at me.

“Oh,” I smiled, trying to think of something to say to counteract that.

“I can’t remember things anymore.” She struggled with the words. “Words and names I used to be able to pluck out of the air at will. I find as I get older, I simply can’t remember them.”

“But that doesn’t mean th….”

“I must be going…what do you call it when old people lose their memory?”

“Senile!” I said brightly.

“Senile! Yes. Thank you. Alec used to say—you don’t know Alec, but he was a great friend of mine—he used to say, ‘Lavinia, for God’s sake, you never could remember those things anyway.’”

“But I forget things all the time, too. All the time!” I said.

“You do?” She sounded like she wanted to believe me, but she was tentative.

“Yes! I’m constantly forgetting things. I even forget what city I’m in.”

This brought a deep rolling laugh from her. At its height, it was accompanied by, then evolved into, a wet smoker’s cough, the kind that sounds alarmingly like splitting wood.

“No, really,” I said, mildly alarmed at her cough but satisfied at my ability to make her laugh, “I’m not kidding. I do forget things.”

“Well, that’s awfully nice of you to say that, but I don’t quite think it’s the same thing.” She stabbed her cigarette out, then immediately reached for another from a long lime-colored pack. “Old age,” she snorted, as her hand trembled with the lighted match.

And so it was, old age. That and so many other things we talked about in the two years I knew Lavinia. Many many things we discussed, but old age came back again and again and pushed its way to the front of the line, like a rude, bossy tourist, demanding to be served first. Now, some thirty-five years later, as I enter that harsh land myself, I think of those years, and of her, again and again. She taught me so much.

As Lavinia talked, I stole glances at her, trying to drink in this new being, this fresh face. She had very pale, almost sallow skin. She had wrinkles, true, but not the deep Lillian Hellman-like slashes. Hers were thinner, and not as profound. I guessed she might be seventy-five. (It turned out she was eighty-one.) Yet she had the most vibrant hair. The color was an appealing blend of russet and wheat, with tinges of gray. It was cut fairly short and flowed in supple waves.

Because her body was simply no longer up to it, her eyes, and, naturally, her voice, were the major ways in which Lavinia communicated her considerable variety of moods and emotions. Lavinia’s eyes, though somewhat cloudy—she was eventually to have two cataract operations—were formidable. They could, and often did, in a single hour’s time, definitively express surprise, remorse, sadness, anger—this occasionally, but what a fearsome sight!—skepticism and worry. I felt I always had to look at Lavinia’s eyes, for fear of missing something dramatic and essential.

In intimate partnership with those stagy eyes was a voice that was frayed and prone to fatigue but which, on any given day, could find its full measure and have you on the edge of your seat. Or, perhaps closer to the mark, could reach out and grab you by the scruff of the neck, as if you were a wanton cat. Just as it did now.

“The thing is,” she burst out, “I don’t like old people. I can’t think of anything worse than sitting in a room with a bunch of old people.” She shuddered. “They’re always complaining.”

“And so you don’t want to be like them?” I was cautious. I was leaving myself the option of retraction.

“No,” she said, “I don’t.”

No, she didn’t. She did everything in her power not to be jettisoned into that general bin labeled old. I’m sure that was one reason why she contacted Village Visiting Neighbors. It was to have some young blood flowing through her days.

“I mean,” she continued, “have you seen those television commercials with that what’s-her-name woman talking about diapers?”

She had stymied me. “Johnson and Johnson?” I said. I named a brand, because I had no idea what woman she was talking about.

“I don’t know,” Lavinia said, not hearing me correctly, “but she used to be in all those college musicals in the 40’s. Small. A little too cute for me.”

“Oh! You mean June Allyson!” My outburst about a somewhat obscure movie star sounded a bit too enthusiastic to me. I toned myself down. I suddenly knew what commercial she was talking about. It was for protective undergarments for old people.

“Yes! That’s the one. And they even talk about incontinence.” She shuddered as if asked to eat something unspeakable.

“I wouldn’t be caught dead wearing one of those,” Lavinia said with bitterness in her voice. “I’d rather urinate in public. So humiliating!”

“Yes, I have to agr….”

“Now, dear,” she said, ceremoniously placing her cigarette down on the ashtray, “I want to hear about you.”

I blurted out a few things. Job: advertising copywriter. Marital status: single. Age: 45. And so on. As I tossed off this necessary but hollow-sounding data, I realized one of the things that was so exciting and yet bewildering about this, my first visit with Lavinia. The fact was that, aside from relatives, I didn’t know any old people. True, I saw them in the street. I jostled up against them in lines. I watched them being picked up Sunday mornings to go visit their children and grandchildren. But I didn’t have any friends who were over sixty.

“….of those advertisements on television are so clever. I adore those commercials with that man who sells chickens.”

Lavinia startled me out of my reverie.

“Oh, you mean Frank Purdue.”

“I don’t know, but they’re awfully clever.”

“Yes, they are,” I said. The truth was, my heart wasn’t in my profession. But that was another story. “Did you know he act….”

“Now, dear, before you go.” Lavinia had a short list in her hand, and she began speaking about it without looking at me. “If you can’t get the peach, then any kind will do. And for this I need the small-sized carton—not the big one, please. The last person they sent couldn’t manage to get that straight. And here’s the money.”

Was the visit at an end? I put my coat on and went out, and in a few minutes bought her what she needed from a delicatessen nearby. When I returned, Lavinia was at the door to meet me.

“Thanks very much, dear,” she said as I handed her the grocery bag. “Now, you go home now.”

“It’s been very nice.”

“Yes, it has,” she said.

“I’ll telephone you soon, all right?”

“That would be nice. Goodbye.” She smiled. Her eyes, even squinted against the outdoors, were bright and alive.

I walked home, excited and enthusiastic, as if I’d just had a first date. And I suppose, in a way, I had.

February 7, 2025

The bird's heart

We have two bird feeders in our yard. We put black sunflower seeds in both. We’ve experimented, like a new restaurant, with different varieties and combinations of seeds for them to eat, but we’ve found, no contest, the birds prefer sunflower seeds. They go at them like college students at an all-you-can-eat buffet. Which is what these ravenous birds seem like sometimes.

We have a few species of birds that reliably come to the feeders: Carolina Chickadees, Cardinals, House Finches, American Goldfinches and Carolina Wrens. We have had, depending on the season, quite a few others: White-throated Sparrow, Red-winged Blackbird, Ruby-throated Kinglet, Downy Woodpecker, Brown Thrasher, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, Baltimore Oriole and Common Yellowthroat. Watching these birds from our chairs on the porch gives us great calmness and joy.

We make sure the feeders are replenished after the seeds are devoured. Our dog keeps close watch on the feeders from her perch on the couch indoors, peering through the window, waiting for a squirrel to come out of hiding to scavenge the ground for seeds that have been dropped by the birds. Seeing a squirrel makes her day.

Lately, we’ve had near-swarms of American goldfinches at the feeders. It’s not unusual to see fifteen at a time at the feeders and on the ground. The males are pretty little things, with yellow-and-black coloring that’s like a small sun. We were especially glad to have seeds at the ready for the birds during our extreme (for Louisiana) cold spell recently. It got as low as 4 degrees. The birds, somehow, survived and, even in the brutal cold, they came to the feeders.

Male American Goldfinch

Male American GoldfinchYesterday, my wife Gaywynn went out to refill the tall hanging feeder we have. I was inside. Suddenly, I heard her call me:

“Can you come out and help?! There’s a bird stuck in the feeder!”

I ran out. Gaywynn was holding the empty plastic feeder in her hand. At the base, where, normally, the birds peck out the seeds, was a little American Goldfinch, stuck. It had evidently tried to get the few seeds left at the bottom and had somehow got its head lodged between a small supporting piece of wood that crossed the bottom and the hole itself. Gaywynn was distraught.

Something like our feeder

Something like our feeder“We have to do something!” she said. We didn’t want to try to twist the feeder, for worry that it would break the tiny bird’s neck. I touched its warm body. It was so small, so vulnerable. It could feel its little heart beating and the warmth coming through its feathers in my hand. What terror it must have felt! I could feel a wetness on the bottom of its little feathered body.

We didn’t know what to do. There was another supporting piece of wood at the top that prevented me from reaching down to the bottom to see if I could move the containing stick a bit to free the bird. We couldn’t get at it. Then Gaywynn had the idea of sawing the plastic feeder in half. I got my little handsaw, tough and reliable, and began sawing. I’m sure it must have frightened the little bird even more. Imagine the colossal sound, so near you and you, trapped.

I got through the feeder, but I still couldn’t reach the bottom. I had to saw further down, which I did. Now we could see the bird’s trapped head clearly. I gingerly placed my hand on the crossbar and tried to move it ever so slowly away from the bird’s head.

In a feathery explosion, the bird escaped and flew away. It flew up into a live oak tree nearby. Gaywynn burst into tears. It seems the bird—a male, from its markings—was fine. It had rocketed up to the tree like nobody’s business. Wouldn’t you? Clearly, its wings still worked. We sighed in relief. It could all easily have gone wrong.

Suddenly, the day was bathed in goodness. We’d freed the bird from its plastic prison. It had gone to live another day—many more, we hoped. Even better, as there was no way for the bird to thank us. It was just the doing of it.

January 31, 2025

Bright lights, big city

You may know these words as the title of a book by Jay McInerny. It was quite popular in the mid-1980’s. I cite it from time to time in writing classes as one of the few books successfully written entirely in the second person.

Long before I read the book, I heard the song. (Which is where the title came from.) It was written and sung by Jimmy Reed (1925-1976), a blues singer with one of the most distinctive voices you’ve ever heard. His voice sounds like you’re resting on a pillow.

Jimmy Reed

Jimmy ReedI suspect not that many people know about Jimmy Reed these days. He had some hits in his hey-day, in the late 1950s and 1960s, but he never became truly famous, like the early rock ‘n’ roll stars Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino. Or even as famous as his fellow bluesman and Mississippian, Muddy Waters. How many even know what his voice sounds like?

I first heard “Bright Lights, Big City” in the early 1960s in Virginia. I know this fact because I bought his album. There was no Spotify, no Apple Music, no Pandora. Just records. Which I loved and still do. They’re a most intimate, informative and gratifying way to listen to music. Not to mention the quality of the sound is unmatched.

Other songs he sang and/or wrote or co-wrote are “Baby What You Want Me To Do,” “Big Boss Man,” “Ain’t That Lovin’ You Baby” and, my favorite, “Take Out Some Insurance.”

I can see the 19-year-old me sitting in the living room in Virginia Beach, Virginia, LP playing, swimming in that voice, getting an education. How long does it take to realize your real education is not in school?

If you were to leave me baby

Say you won't be back

That would be the end of me

'Cause I'd have a heart attack.

You better get some insurance on me, baby

Take out some insurance on me, baby

'Cause if ya ever, ever, said goodbye

I'm gonna haul right off and die.

This was a way to learn about people I could never meet or know. This was familiarity. This was a kind of friendship. I certainly gave him all my enthusiasm and affection. He gave me smiles and beauty. Widened my somewhat narrow horizons. In some ways, we’re more segregated than we’ve ever been these days. There are so few ways to connect. Jimmy Reed welcomed me in with his music. What did I know about all this? Not much.

Jimmy Reed died young, age 51, and had his struggles with alcohol along the way.

That’s not to say that people don’t remember Jimmy Reed. Bob Dylan does. His song, “Goodbye Jimmy Reed,” was part of his 2000 album, Rough and Rowdy Ways. Neil Young covered “Bright Lights, Big City” on his Everybody’s Rockin’ album. Elvis Presley covered Jimmy Reed songs, as well. Still, even though he was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991, it really can’t be said that he’s a household name. Even to music lovers. If you haven’t, try his music.

You don't know me, baby

Like I know myself.

That’s Jimmy Reed! Yeah!

January 24, 2025

Not the way I want to go

I’m an early riser. 5:00AM, generally. I have my clothes ready on a small table near the bed. Underpants, undershirt, pants, shirt, socks. The first thing I do when I get out of bed is to walk to the aforementioned table and reach for my underwear. I raise a leg up—always my right leg for some reason—and, balanced on my left, insert it into the underwear. Then, standing on my right leg, I insert the left leg into my underwear. Process completed. Nothing different than what millions of people do every day.

If all goes according to plan.

This morning, it did not. When I raised my leg high to go into the underwear, my foot got caught on the underwear’s edge. It was wedged between two toes. I was stuck, and I began losing my balance. I started hopping to regain it. As anyone knows who has tried to hop on one foot, it’s increasingly difficult to control the direction or velocity of the hop. I hopped and hopped, foot stuck in my underwear, around the room, until the hopping took me to a point where being vertical was no longer tenable. This seems right out of a Charlie Chaplin movie, only it was no cinema.

Warning! Danger!

Warning! Danger!Everything went into slow motion at that point. It was as if I were watching myself, one hand holding the underwear’s edge tightly, and then, foot caught, I was falling, falling, falling. No one was going to catch me. So, I fell. Fortunately, the floor in my bedroom is carpeted. Still, a senior falling from the upright position to a horizontal position on the floor can have unforeseen consequences. This morning, my left shoulder and the top of my left arm hit the floor first. I probably bounced a bit. I know it hurt. I didn’t break any bones. I was just bruised.

This time.

But what about next time? As I get older and older, I am more susceptible to this kind of mishap. Consequently, to injury. To a fall in which I break a bone. Or even crash my head against the wall.

I imagine an obituary would read something like this:

BIZARRE UNDERGARMENT FATALITY

Richard Goodman, 79, died Thursday. Goodman, in the process of trying to put on his underwear, apparently got caught up in the garment and suffered a fall, striking his head on the floor, which proved fatal. Goodman’s landlord discovered his body when he came to repair a leaky faucet. “I found him there on the floor, half-in, half-out,” the landlord told police. “Very sad. And odd.”

I don’t want a death that makes people laugh. It’s just too humiliating. I don’t want people to say, “He fell and hit his head after he got tangled in his underwear.” Then laugh. Because, who wouldn’t laugh? I wouldn’t blame you. I just don’t want it to happen to me.

Growing old, I feel sometimes like I’ve become an actor in a farce.

Just give me a normal, not-funny exit.

January 16, 2025

The last pointu

They said he was perhaps the last builder of pointus in France. He was 83 years old and lived in Saint-Aygulf, a small town on the Mediterranean almost midway between Cannes and Saint-Tropez. His name was Raphaël Autiéro.

The fishermen in Sanary, the coastal town about 100 miles west where I was living and researching a book, knew about him. It’s even possible they owned one of his boats at one time, but I could never verify this. I was told that he was in the middle of building a pointu for a contest, of all things. A well-known maritime and boat magazine was sponsoring a contest, “to reconstruct or restore the historical and traditional boats of the French ports.” The contest was divided into categories according to length and type of boat, and the judging would take place in Brittany in the summer.

Saint-Aygulf, which is between Saint-Tropez and Cannes.

Saint-Aygulf, which is between Saint-Tropez and Cannes.I came to see him for the first time on the 19th of March, the day set aside by the church for St. Joseph, patron saint of carpenters. He lived in an old villa near the sea with his daughter, son-in-law and their children. I’d called ahead and asked his daughter if I might visit. Next to his villa was his large workshop. I knocked on the workshop door at 9:30 A.M. on a sun-filled morning. I heard that confident, raspy voice for the first time asking me in.

When I opened the door, I saw the pointu he was working on, huge-looking in its confinement, tilted to one side by wood supports. Sawdust and wood shavings were everywhere. Beautiful wood was leaning against walls and stacked in precise piles on the floor and jutting out from bins above our head. The aroma of wood filled the room. Wood, wood, wood. Motes of woody dust floated on sunbeams. The light shone through windows onto the many tools he had on a long work table nearby.

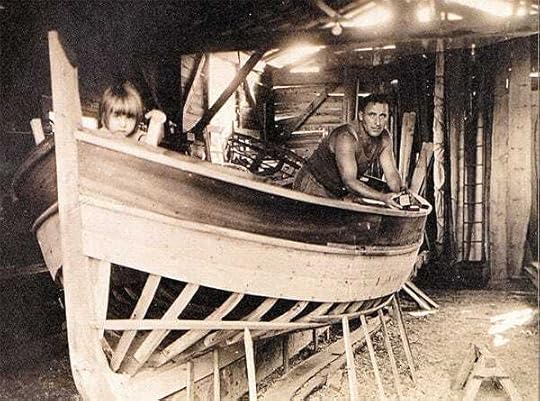

Raphaël working, in the 1940s, with his daughter observing.

Raphaël working, in the 1940s, with his daughter observing.He stood there in baggy trousers and a T-shirt; he had a mallet in his hand. He was short, white-haired and powerful-looking. While we talked, he never stopped working. It was his eyes I noticed first. Raphaël Autiéro’s eyes were blue and limpid as the Mediterranean. They were strong eyes, full of hope, full of tomorrow, and they trained upon you with no glasses in the way. I looked as often as I could into his eyes—absolutely without clouds they were—and was astonished by their youth.

If a voice might be described, like a fine Bordeaux—earthy, powerful, perfumed with soil and vines and a whiff of the sea—this was Raphaël’s voice. It wasn’t the whispering, listless voice I heard emitting from the retraitées, the retirees, in Sanary. Raphaël’s voice came directly from somewhere vital. Though he had a wonderful smile, he also had great Italianate swings of emotion, and so I often heard him use this voice to full force. He hated the French government, and I can still hear him railing at them, “Des brigands! Des brigands!” Robbers! Robbers! His magnificent rasp carried to the far end of his workshop.

“So, you’ve come from America to meet an old boat builder?” he said.

“Yes, I guess you’re famous all over the world,” I said. I wasn’t far off. Through the small world of enthusiasts, he was even known by a few boat builders in America. He’d had visitors from all over France and beyond.

Raphaël Autiéro.

Raphaël Autiéro.“Well, what do you want to know?” he asked. He began to work as we talked. He took up the mallet and began knocking. I circled slowly around his still skeletal pointu, its fresh, young ribs sticking out.

He began building boats with his father when he was twelve. He reckoned he had built about one hundred boats in his lifetime. Were they still in use? What was it like, I wanted to know, to be perhaps the last pointu builder in France. What about his sons? His grandsons? Weren’t they interested in learning?

“No. It’s hard for me to get them away from their television sets and their computers even to go on a short boat ride with me. I have to force them. When I do, they love it. But this,” he waved his hand at the boat, “this stays with me.” Raphaël was calmly realistic about how the world of fishing had changed. He wasn’t bitter. But one word about the French government, and he was off:

“Thieves! The government are thieves! I stopped building boats four years ago, because of their taxes! I had to pay more than I make.”

All I had to do was say, “L’ètat,” the state, and his voice would explode. These two boats he was making for the contest were an exception and would in fact be the very last he would make. The town of Saint-Aygulf was paying the cost but not all. Some of the money was coming from Raphaël’s own pocket.

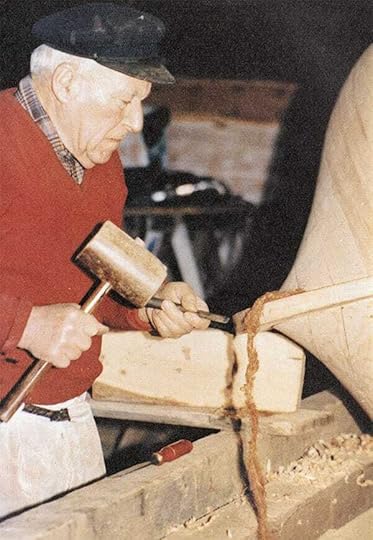

Raphaël working.

Raphaël working.“Why should we give him any special treatment?” a local tax official said when I asked him about Raphaël’s high taxes.

“But,” I said, “he’s a special case. He’s perhaps one of the last men who knows how to build a pointu—maybe even the last. He’s like a living museum. The taxes are high for him. Can’t the government make an exception?” The official was unmoved. “If he makes money, he will be taxed.” France, which has so often been tolerant of its artists, bending the rules in their favor—think Jean Genet—was rigid here. I just counted myself lucky I’d arrived at his workshop before Raphaël quit building altogether.

“Now the boats are made of Aleppo pine,” he said. “Before, we used mahogany from Gabon.” Look at the French words: L’acajou du Gabon, and suddenly the sense of France’s former colonies, that great adventure and exploitation, surges forth. You cannot help thinking of this country in days past—in days Raphaël knew intimately—with its rubber coming from Vietnam, cane sugar and rum from Martinique, leather and spices from Morocco, wood from Gabon.

“You must have good wood,” Raphaël said, stroking the unfinished boat tenderly. “The wood must be cut dans une bonne lune,” he said. During a good—or waning—moon. So, that the wood isn’t in flower, as he put it, and the sap isn’t rising. “When I find bad wood, I know it wasn’t cut during a good moon. It also should be cut in winter, in December or January, that’s best, so it doesn’t deteriorate.”

I stroked the smooth, nearly living wood, the grain and texture, and I let my hand glide across it.

“It feels so sensual,” I said, “like….” I bent forward. I was tempted to kiss it.

“Like the buttocks of a woman,” Raphaël said matter-of-factly.

“Yes!” I said, drawing back discreetly. I looked long at the boat he was building.

Raphaël looked moody. “Today, when I go to a woodcutter and ask him to cut my wood during a good moon, he says to me, ‘No, I can’t possibly guarantee that. I have to cut the wood when I can, when my men are in the forest.’ But I tell him, ‘I’ll give you one year to deliver if you can promise me that.’ But they still won’t.”

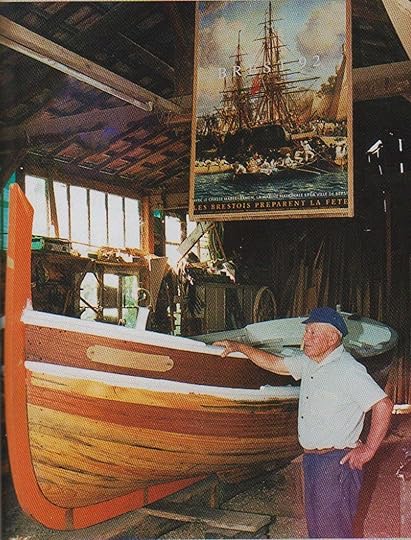

Raphaël with one of his (unfinished) pointus.

Raphaël with one of his (unfinished) pointus. He had managed to obtain mahogany from Gabon for these boats, and so he was very pleased.

It takes him about three months to build a boat. If it is built well—by someone like Raphaël—a good pointu, well looked after, will last sixty years. It will more than pay back its original cost. A pointu is not an especially heavy boat. Of course, you can have different lengths, but the boat Raphaël was working on was 5.85 meters long (19 feet) by 2.20 meters wide (7 feet). It weighed just 900 kilograms, or about 2,000 pounds. Much less than the fishing boats in Sanary with their big diesel engines.

As Raphaël described it to me, the pointu has “the shape of half a nut.” It originated, it’s thought, in Naples, and probably its popularity spread north and west to France when fishermen found it well suited the erratic, short-spaced waves of the Mediterranean. It’s an open boat—like a rowboat in shape but worlds apart in spirit—it was, before motors, equipped with a lateen, or slanted, sail and up to four pairs of oars.

In their pointus, fishermen sailed—and rowed, if there was no wind—as far as Corsica, over 100 miles from shore. Mostly they stayed close to home, fishing a mile or two offshore. Men fished mostly for sardines, which were there in abundance. They also fished for scorpionfish, eel, wolfish and anything else they could net. For the most part, they went after la blé de la mer, as fishermen called sardines, the wheat of the sea.

“In the old days,” Raphaël said, “you had to have a light boat. In the winter, you might pull up your boat three or four times in one night. You’d leave at 5 PM, cast your net, come back around 9 PM, sleep for two or three hours and then go back out. Each time, you had to pull the boat up on shore. We didn’t have all these docks and anchorages back in those days. That’s why the pointu had to be light.”

A pointu, berthed in Sanary-sur-Mer. The words, “Lou Pantai,” in Provençal, mean “shore,” “coast” or “beach.”

A pointu, berthed in Sanary-sur-Mer. The words, “Lou Pantai,” in Provençal, mean “shore,” “coast” or “beach.”Raphaël would often be asked to repair the boats he had built if, say, there had been an accident of some kind or if it needed fixing. He was often shocked by the condition of his boats. “Some,” he said spiritedly, “you could eat bouillabaisse off the bottom. Others....” He shook his head.

I saw him several more times after that first visit. Each time it was lovely to see how the boat had advanced. It was hard to finally leave the smell of wood, the sunlight streaming in, the motes dancing in the air, and the great, nearly finished pointu, leaning on its side. On my last visit I circled around the boat one final time, stroking it, letting my hand slide freely across its side. It was a room full of learning, skill and beauty. I thanked Raphaël for his time and for the privilege of watching him work. He was modest in reply, as always.

Soon after, I finished my time in Sanary. I’d been there for six months. It was time to leave. I left France and returned home.

Back in New York, six months later, I received a note from Raphaël’s daughter that said, “Papa died yesterday. Very, very sad.”

Here was a man who did exactly what he wanted to do with his life, and he did it well. He knew it. He had done what he was supposed to do on this earth. People had benefited from his gift, fed their families and made do. He had created beauty—a useful beauty. I hope I can say something like that at the close of my time here.

January 10, 2025

Our dog

Her name is Manon. It’s a French name. She’s a Louisiana dog, a rescue, and because we live in Acadiana, in south Louisiana, and my wife, Gaywynn, is Cajun, we wanted a name that is French. The name Manon will be familiar to those who know the movie, Manon of the Spring (Manon des Sources in French.) It’s not a well-known name in America, and so we inevitably have to say it more than once to people and explain why we chose it.

Manon is a pretty dog, a black and white female, about three years old, of indeterminate ancestry. We think there must be some Border Collie in her. That’s what people who see her for the first time often say. But we don’t really know. Clearly, she’s got more than one breed in her past.

Manon as Sphinx.

Manon as Sphinx.She weighs about forty pounds. She has ears that are luxuriously soft to the touch, flopping like beauty in your hands. The tip of her tail is white. She has wide, darkish spots on her belly. Her most distinguishing feature, though, is her underbite. You can’t see it when her mouth is closed, but when it’s open, you can. It’s both comical and a bit scary.

Manon in Chicago, right at home.

Manon in Chicago, right at home.We adopted her when she was about six months old. We don’t know what happened to her the first months of her life, but we suspect something that wasn’t good.

She’s very shy around people—including me, sometimes. She doesn’t like it when someone raises their voice and will slink away when they do. If you try to pet her head, she lowers that head and sometimes moves out of the way. She’s much more comfortable around females and often takes to new women we meet, and girls, immediately. This makes me feel guilty for all past male behavior. To make a dog fear you seems to me to be a grave sin, but people do.

My daughter, Becky, filming Manon. Note belly spots.

My daughter, Becky, filming Manon. Note belly spots.She doesn’t bark much at all. Hardly ever. In fact, when we first got her, she didn’t bark at all for weeks, and we thought she didn’t know how. She does, though. She will bark, but never superfluously. Usually when she hears the UPS truck approaching.

When we first brought her home, she chewed everything in sight. Probably from anxiety in being in a new place with new people. Eventually, she became accustomed to us and our home, and she stopped. Not before many items were destroyed. She hasn’t relapsed, thankfully. Her favorite activity—what she lives and breathes for—is the squirrels. To be specific, the chasing, catching and demise of said squirrels.

She’s a sweet soul. She loves to play with other dogs, but she’s deferential around them. She’s never exhibited one aggressive tendency in her life. I’ve never even heard her growl. If there was a war, she’d be a pacifist. She’s fleet afoot. We have three acres here in south Louisiana, including a long stretching front lawn, and she loves to dash around it like a comet. She’ll chase and retrieve a ball and likes me chasing her. I will, until I run out of gas, which is soon.

She’s Gaywynn’s dog, really. When Gaywynn comes home in the evening, Manon is beside herself. We’ve all seen crazy-happy dogs greeting their owners, leaping, running in circles, just flipped out seeing their beloved human. I’m a bit jealous, I admit. Not pathologically, I hope.

We’ve grown to love her very much. Like many fervent dog owners, we talk about her when we’re not home with her, especially when we go on trips and have to board her (it’s a nice, caring place) for a few days. We might as well be talking about our child we just dropped off at college and how lonesome we are without her. It usually starts the minute we leave her.

Manon is a bit mysterious. There’s part of her that she keeps to herself. She doesn’t always act like a typical dog. For instance, when we put food in her bowl, she’ll often ignore it—for the entire day. Then, for whatever reason, after leaving the food untouched all day, she’ll walk up to her bowl and eat. No rhyme or reason—to us, anyway.

Manon meditating.

Manon meditating.A dog adds something inexplicable to a home. Yes, affection, humor, sweetness and playfulness. Also, the delight of being around a creature who acts on pure instinct. What freedom not to have to think about everything. Manon was homeless when we found her, and now she has a home. That sense of providing a home for her partly fills a hunger in me for a home. When you give a dog a home, you give yourself a home as well.

Manon resting peaceably with our cat, Grace.

Manon resting peaceably with our cat, Grace.Having a pet usually means, because of how they age, that you’ll witness their decline and, eventually, end. You know you’ll be a caretaker, and you will do your best to ease them on their way. I don’t like to think about that much. But a dog—our dog—will remind you of the temporality of life, the transitory nature of things, of how it’s all borrowed, every minute, and that eventually, the ticket will be recalled and there is no more time. Every dog you love carries with them a foreseen sadness.

In the meantime, she’s here, with us, alive and well, youthful, the singular dog she is. We love her. Manon of the Spring.

Squirrel! I see you!

Squirrel! I see you!

January 3, 2025

Judy Hartline Elbring

Reading the New York Times’ Bestseller list recently, I saw Kristin Hannah’s novel, The Women, about nurses in Vietnam, near the top. It made me think about the brave Judy Hartline Elbring once again.

When, some years ago, I found Women in Vietnam: The Oral History, edited by Ron Steinman, my eyes were opened. (Hannah mentions this book in her acknowledgments.) I’d read quite a few books about Vietnam—the war of my generation—but I hadn’t read a thing about the women who served there, most particularly the nurses. I stayed up half the night reading the testimonies of the nurses Steinman interviewed who served in Vietnam. All the nurses’ stories are stories of courage, but one nurse’s story struck me especially deeply: Judy Hartline Elbring’s.

Elbring volunteered to go to Vietnam in 1967. (All nurses in Vietnam were volunteers.) She might have been shocked or frightened by what she encountered, but, as she told Steinman, “There wasn’t time to be scared. There wasn’t time to worry about anything except the immediate job at hand.”

She saw what it was like.

“To see a kid who’s not that much younger than I am. He’s my brother’s age, and some of them are younger. They’re eighteen and nineteen years old, and they’re kids and they’re skinny and they’ve been in the jungle too long and they haven’t eaten well and the bones in their face show, and their uniforms are dirty and they smell bad, and now they’re going to die.

“I remember after we were through work and had done all we needed to do, there would always be a few of them that were behind a curtain in the area where we used to keep them. I would go back there with them, and I would pet them until they died because I was like their mother, their sister, their girlfriend. I would stay with them until they died, because too many of them died alone, and that’s not right. That’s just not right.”

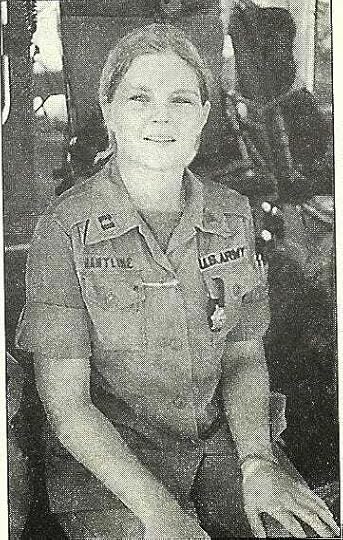

Judy Elbring, née Hartline.

Judy Elbring, née Hartline.So some of you mothers who lost sons in Vietnam, know that it might be that Judy Hartline Elbring was there with your boy, easing him into his dying, helping him in his hour of being taken away, so that he didn’t begin that journey alone.

She came home. She wore her uniform, and she was vilified. “There was no one to talk to about this.” Nevertheless, she went back for a second tour. Her brother, a marine, was going to Vietnam, and she wanted to be there in case he was wounded. He was, and she was able, because of her rank as a captain and simply because of her will, to be airlifted to his base and to take care of him.

She came home again to hostility. “I was just a nurse. I did my duty as I needed to do my duty. But what I didn’t get was that I hadn’t been welcomed home, and if that’s important to me, it’s got to be important for other women too. I had no idea this was still affecting me. I had no idea that not saying anything could carry this long a toll on me, on anyone. How many women are sitting on their anger, are sitting on their sadness?”

She ends her account with the picture in her mind of a boy who died, a boy for whom she could do nothing. “He stays with me. I don’t know why he stays with me, but he does. He comes back in my dreams. They’re helpless dreams in a way. They’re all the things I can’t do anything about. I would love to be somebody’s good dream. Oh God, wouldn’t that be wonderful? I’d be very proud to be somebody’s good dream.”

Vietnam Women's Memorial

Vietnam Women's MemorialAfter reading her account, I was so haunted by her qualities, I went and found her on the web. She lived in California, and she and her husband ran an organization that helped couples with their relationships. I sent her a fan letter. She replied with a handwritten letter thanking me. I had a letter from my new hero.

Judy Hartline Elbring died in 2022 at the age of 80. What a brave and gracious life she lived.

A brave, compassionate woman

A brave, compassionate womanI would think, in her time in Vietnam, she was more than one young wounded or dying soldier’s good dream.

December 28, 2024

The snows of yesteryear

It’s impossible to be certain you’re getting what’s essential in a poem by the 15th century French poet François Villon. As Galway Kinnell says in his introduction to his translation of Villon’s poems, Villon is toe-to-top in slang. That slang was already hard to decipher 100 years after Villon’s death. And here we are over 500 years later.

Villon, born in 1431, is one of these writers who had a hyper-romantic life that included being a thief and a killer, almost being hanged, imprisoned more than once and who, to enshrine his aura forever, vanished from recorded history in 1463, providing for freewheeling speculation as to his fate ever since. There have been movies, plays and novels created about him. But he isn’t, I don’t think, a poet most Americans are familiar with. I’m not sure what the French think of him.

“Much of Villon’s popularity arises from sympathy for the difficult life he led,” the Poetry Foundation says, “which is described with both humor and poignancy and at great length in his largely autobiographical poetry.” His major work is Le Testament (“The Testament”), written in 1461. In it, he describes the hardships he endured, but with a sense of straightforward melancholy. He does hope his tormentors get their due, though.

The most famous line of Villon’s is “Mais ou sont les neiges d’antan?” It’s usually translated as, “But where are the snows of yesteryear?” This line, repeated at the end of stanzas in Villon’s poem, Ballade des dames du temps jadis, (Ballad of Ladies of Time Gone By), is about famous women in history (Héloïse, Joan of Arc) and their passing. “Where are the snows of yesteryear” has long emerged from that specific reference to signify the melancholy of death and loss that visits us all.

Tennessee Williams places the words, Ou sont les neiges, on a scrim at the beginning of The Glass Menagerie. He calls Glass Menagerie a memory play, which makes the Villon reference apt.

And who knew that these words could also be considered prophetic? With less snow everywhere.

Few poets I’ve read, in English or in translation, write about the loss of beauty and youth and the cold starkness of death as memorably as Villon. He’s the great poet of “Where have they gone?” So, now, age 79, when I think of my old friends, some of whom I haven’t seen in decades, I turn to François Villon’s words from The Testament in Kinnell’s translation:

Where are the happy young men

I hung out with in the old days

Who sang so well and spoke so well

So excellent in word and deed?

Some are stiffened in death

And of those there’s nothing left

May they find rest in paradise

And God save the ones who remain.

Villon, supposedly

Villon, supposedlyAll I can do is think of my friends from my youth—of Dud, Chris, Alex, Sandy, Rick, Bill, Monty and others. Some I’ve seen through the years. Some I see infrequently. Some I no longer see. One I can’t find. One died recently. And, yes, they sang so well and spoke so well. And they were happy. And they were excellent in word and deed. And God save them all.

December 19, 2024

Music at Christmas

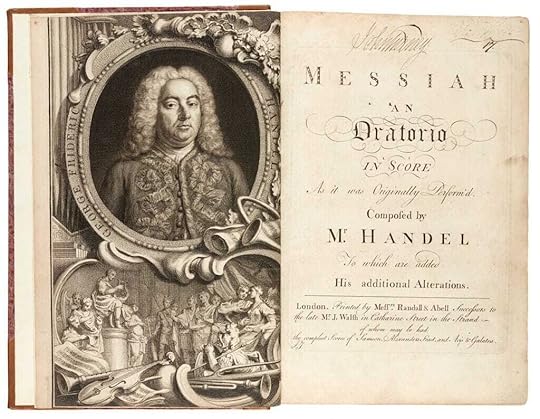

At the top of the list—Handel’s Messiah. By the German-born, naturalized British citizen, George Frideric Handel (1685-1759). It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742. Continued to be performed. Still, as we know, is.

I listen to this oratorio all through the year. The thing about this music is that there are some of the most uplifting passages and some of the saddest—all in the same piece of music. In the exalted category, well, to name three, “Every valley shall be exalted,” “For unto us a child is born” and “I know that my Redeemer liveth.”

And, of course, the iconic “Hallelujah!” chorus that makes everyone feel that they’re two inches higher.

Messiah isn’t just the story of the birth of Jesus but of his death as well. It’s sung both at Christmas and Easter, and sometimes it’s abridged to suit the particular holy day. Handel’s music is sublime, but the great choice he made was to have his words, the lyrics, taken from the Bible. From both the Old and New Testaments. (There is an actual credited librettist, but I’m still trying to figure out what he wrote.) Many of the most stirring passages are taken from the Old Testament. Isaiah is heavily drawn upon. Whatever your beliefs, if you love language, you can be uplifted by these words. “Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill made low; the crooked straight and the rough places plain” can move an atheist as well as a believer. That’s true of all great sacred music, isn’t it?

And Messiah—everywhere I search it’s never referred to as The Messiah—has some of the most movingly sad music, too.

“He was despised and rejected of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” This is Jesus, alone, scorned, ridiculed. “…a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” You can’t write much better than that. In the Bible, the language is never just about dispensing information. The Bible, at its highest level, is poetry, as anyone knows who has read the 23rd Psalm. This is language that, even without Handel, is music. “But who may abide the day of His coming…” Add great music and—sublime.

What better choral/opera/oratorio is there in English? Can you think of another piece of music, for soloists, orchestra and chorus, sung in English, that can stand up to the Italian, French and German efforts? Listening to the chorus sing, “For unto us a child is born,” I hear male and female voices balanced, in counterpoint, playing off one another with equal force and effect, so that I feel not just stirred but optimistic for all of us.

I read somewhere that Beethoven, an admirer of Handel’s, said something to the effect that no one did more with less. I feel with Handel that he used every ounce of his talent and capability. That there was nothing left to draw on. He didn’t squander a thing. With Messiah you can hear—and if you see it live, see—how well constructed it is. He may have been born German, but Handel knew how to set English words to music.

I listen to Messiah in July. I listen to it in October. In season and out of season. It’s not just a wonderful piece of holiday music. It’s wonderful music, period.

Have a great holiday.