Richard Goodman's Blog, page 3

April 25, 2025

A tale of two turtles

A few years ago, we had a water oak in our yard cut down. It was too close to the house, and, being a not-especially strong tree, the wind—we’re in Louisiana, so read hurricane—might cause it to fall on our small, unprotected home.

What remained was a stump that gradually, over time, decayed. A few days ago, we burned it, or as much as we could.

The next morning it was still smoldering. We were watching the smoke curl upward when my wife, Gaywynn, spotted a turtle next to the smoking stump.

“There’s a turtle!” she said. “It’s next to the fire!”

We ran outside to the turtle. It was about a foot long, and clearly not a baby. What was it? My iNaturalist app told me it was a red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans).

Turtle!

Turtle!“We have to make sure it doesn’t get into the fire!” Gaywynn warned.

What to do? Should we move it somewhere to safety? Did it need to be near water? We don’t have water on our land or nearby. Should we just put it in the woods?

I texted Erik Johnson, a conservation scientist with the Audubon Society in Louisiana and an expert on birds as well as other plants and animals of the region. I’d met him at a bird banding workshop. “What should we do?” I asked.

Then it struck me that we were the classic interferers. How can this poor animal survive without our help? We must rescue it! It needs us! It can’t make its way through life without our intervention!

“Look at this turtle!” I said to Gaywynn. “It seems healthy! It’s nice-sized! It came here on its own! No one kidnapped it and dropped it in our yard! It fucking doesn’t need our help!” I started laughing insanely.

Red-eared slider. Note the red stripe in back of the right eye.

Red-eared slider. Note the red stripe in back of the right eye. The message came back from Erik. “I'd just leave it. Might be looking for high ground to lay eggs.”

So we did. We went back inside and, from time to time, watched the turtle move across our lawn, first going one way, then another. Something drew our attention away for a bit, and when we looked back, it was gone.

“Man, that turtle is fast!” I said, laughing at how absurd that sounded. But true! We couldn’t find a trace of it.

That crisis resolved, we had errands to do. We set off. We drove down a road that cut through developments when we spotted another turtle making its way across that road. Cars were driving by fast. It could be run over any second. We passed it and quickly made a U-turn and stopped.

I got out of the car, ran across the divide to the turtle. I started to pick it up to carry it to the side of the road out of danger when I realized that it was a snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). It was smaller than the turtle we’d found in our yard but substantial enough. As I reached down to grab its shell, it turned and came at me, head extended, mouth open, jaws ready.

Snapping turtle. Don’t f with it. (Photo by Turtle Survival Alliance.)

Snapping turtle. Don’t f with it. (Photo by Turtle Survival Alliance.)This creature was aggressive and unafraid. If I went to one side, it turned, following me, its neck extended, powerful mouth poised. Afraid? Me?

Suddenly, another car screeched to a halt and a young woman rolled down her window and leaned out.

“Take it to the side!” she yelled. Which was what I was trying to do without having a finger removed.

“It’s a snapper!” I yelled back.

She jumped out, went to her trunk and pulled out something. She ran across the road to me and the turtle. Cars were whizzing by. She handed me what she was carrying, something shrink-wrapped.

“What’s this?” I asked, taking the package.

“Frozen chicken. See if he’ll bite it, then flip him over the side.”

I could see it was Cajun chicken, because it had a deep rust color, the result of being smeared with the seasonings I had become so familiar with living here in southwest Louisiana.

Very similar to what was handed to me.

Very similar to what was handed to me.There was about a foot of concrete along the side of the road, the barrier of a sidewalk. I placed the edge of the frozen chicken package near the snapper’s jaws. He lunged at it, took it.

“Bite that chicken, you bitch!” the young woman said.

The turtle let go, perhaps insulted by the woman’s words. I placed the frozen chicken under the turtle’s body and, after a few attempts, flipped it over the edge of the concrete onto the grass.

“Good job,” the woman said, taking her frozen chicken back, running back to her car and zooming away.

I crossed the road to our car, and then we drove away, too.

Later, I read the snapping turtle’s bio and came upon this, “It may be tempting to rescue a common snapping turtle found on a road by getting it to bite a stick and then dragging it out of immediate danger. This action can, however, severely scrape the legs and underside of the turtle and lead to deadly infections in the wounds.”

I didn’t read anything about frozen chicken.

April 18, 2025

Easter, 1955

It was a small church in the country, about five miles from where we lived in Virginia Beach, Virginia. This is where my mother took us every Sunday—my brother, sister and me. It was an Episcopal church built with brick like so many buildings in that part of southeastern Virginia, marked and influenced by the colonial past. We went reluctantly, my brother and I, especially in the summer, when baseball and barefooted freedom called to us. But there was no question of not going. We put on Sunday clothes and shoes that tamed our wildness.

My boyhood church, Eastern Shore Chapel.

My boyhood church, Eastern Shore Chapel.I knew some of the people who came and some my mother knew and some we only knew from those Sundays in church. I might have whined about going, but there were moments when I sat there where the language and stories from the Bible entered me and became fixed and I think determined, at least somewhat, the course of my life as a writer.

In this little Virginia church there were two days that were the mightiest, the most significant. They were Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Though they were two days apart, the two days could not have been more different.

We usually went to church on Good Friday. This was the day Jesus was crucified. We had been taught the story in Sunday school, and the minister had led us up to this day the Sundays before. We knew what was going to happen. We knew that Jesus was going to be crucified. But part of me didn’t want to believe that. Part of me didn’t want to believe that his father—that God—was going to let his son die. It couldn’t be! As the time went by in the church, and the sad words from the Bible were read by the minister, I kept hoping that God would save his son from dying. Maybe this time it would be different.

Inside the church today. Not much different than I remember.

Inside the church today. Not much different than I remember.But they did nail him to the cross. And he did die.

And when the minister read those lines that Jesus said as he died, “It is finished,” a great sadness came over me, and I felt a great sadness sweep through the church, as dark as the clouds that the Bible says covered the sky the afternoon Jesus was crucified. I went home with my mother sad and gloomy. It was a dark day in every way. Saturday was as well.

Then, at last, Easter Sunday. We dressed in our finest. My mother wore a wide-brimmed hat, a lovely dress, and white gloves that inched up her forearms.

When we walked into the church, it was festooned with flowers everywhere. Sprawling, exorbitant arrangements by the altar, and along the sides of the church. Easter came at the same time as our Virginia spring, so the windows of the church were thrown open and the smells from the blooming flowers from outdoors entered and flowed about. Everything was saying rebirth. The women and girls were dressed in beautiful bright colors, yellows I remember, chiefly. All the women wore Easter hats. They looked like queens. Joy filled the room. Jesus had risen from the dead! He was not dead after all! He had come back from the dead and walked the earth and then ascended into heaven to be with his father.

Everyone was smiling. We sang joyful hymns, “Jesus Christ is risen today

Alleluia! Our triumphant holy day, alleluia! Who died once, upon the cross, alleluia! Suffer to redeem our loss, alleluia!”

The voices rose. I watched my mother sing. I sang, too. We sang in jubilation.

After the service we shook each other’s hand and wished each other a Happy Easter. The Lord Had Risen! Praise the Lord! Everyone was happy—joyous. Yes, joyous. From great despair to great joy in one weekend.

We rode back home in my mother’s car. If the day was warm, and it often was, the windows would be down and the sweet breeze came into the car.

In a few years I would stop feeling these things as if they actually happened to a man who walked the earth. I would still go to church on Easter, still love the words and the music and the flowers and love seeing the women in their finest. But I would never again feel exactly as I did as a boy in 1955 that everything was wrong with the world and then, just a few days later, suddenly, in a burst of communal joy, everything was right with the world.

April 11, 2025

Birds in the Louisiana woods

It’s hard to find someone who is half-hearted about birds and birding. It’s not really a “sort of” kind of thing. On the one side, you have the passionate; on the other, the “doesn’t-do-a-thing-for-me.” I am a card-carrying member of the first group. Birding, as they used to say, sends me.

If I had untold riches, I would go birding around the world. But since I have told riches, I do my birding locally. Around here, in southwest Louisiana, where I live, the birding is pretty good. Migration helps. Birds make their way north from their winter homes in Mexico and Central America across the Gulf of Mexico and pass through Louisiana, stopping to bulk up for the long voyage to their northern summer homes. We also have many birds who are year-round residents—herons and egrets, especially.

Yesterday, I went birding with a friend, David Hebert, a birder and fine photographer, at the Nature Conservancy’s Cypress Island Preserve at Lake Martin in southwest Louisiana. It was a good day. We met at 9AM and set off. The morning was ideal, sunny with temperatures in the 70s. The path we walked down is canopied, shadow-throwing, calm, wide.

Our birding path at Lake Martin. RG photo.

Our birding path at Lake Martin. RG photo.The pathway is bordered on each side by clean, un-fetid swamp, with tall, healthy cypresses, more than I’d ever seen in Louisiana in one place. There were no other people. It was quiet, except for nature. We walked at a leisurely pace, stopping often to listen. There were birds there, we could hear them, but they were not always easy to see. But see some we did.

Some of the many cypresses at Lake Martin. RG photo.

Some of the many cypresses at Lake Martin. RG photo.We were looking for Prothonotary Warblers especially. David had seen them there before in some numbers. That name sounds like an eccentric British name out of an Evelyn Waugh novel. He even has a character with a bird’s name, Peregrine Crouchback. I can see someone named Prothonotary in a Waugh novel. According to Cornell’s “All About Birds,” “The Prothonotary Warbler got its name from the bright yellow robes worn by papal clerks, known as prothonotaries, in the Roman Catholic church.”

We saw several. It’s a piercingly bright bird. I love warblers in general. They’re small, flitty birds with a variety of colors, the main one being yellow. It’s like spotting a sunburst in a tree.

David, whose business is photography, snapped away.

Prothonotary Warbler. Lake Martin, Louisiana. Photo by David Hebert.

Prothonotary Warbler. Lake Martin, Louisiana. Photo by David Hebert. We saw two Barred Owls.

Barred Owls. Photo by David Hebert.

Barred Owls. Photo by David Hebert.We saw a Northern Parula, another warbler.

Northern Parula. Photo by David Hebert.

Northern Parula. Photo by David Hebert.We heard, but could not see, a White-eyed Vireo. They’re small birds, often hiding in underbrush, and hard to locate, with a strong sound.

We saw a Yellow-crowned Night Heron.

Yellow-crowned Night Heron. Photo by David Hebert.

Yellow-crowned Night Heron. Photo by David Hebert.We saw a Red-bellied Woodpecker.

Red-bellied Woodpecker. Photo by David Hebert.

Red-bellied Woodpecker. Photo by David Hebert.The non- or anti-birder will reply, “So what?”

I’d like to bring in the novelist Jonathan Franzen here. He’s an avid birder. He wrote a piece for National Geographic titled, “Why Birds Matter.” It’s insightful and persuasive and paywalled. National Geographic, in some instances, you should not paywall articles. You are essentially saying, “Birds matter and I’ll tell you why if you pay me.” So how important can they be, Nat. Geo.? Only to those with money?

Instead, here’s a (free) interview with Franzen via the Audubon Society. In the interview, when he’s asked why he loves birds, Franzen answers, simply, “They sing. They fly. You can actually see the whole animal taking wing. They make nests. Flight, the complexity of their behavior, their beauty, and I’ve already mentioned song, but I’ll mention it again.”

Birds make you—me, at least—less consumed with myself and bestow me with a sense of wonder. Wonder is a child-like emotion that many of us lose as adults, because it’s not sanctioned as adult-worthy. It’s sloppy and uncontained and obvious. It’s made of 100% pure, unadulterated enthusiasm. There is no arrogance in wonder, and it’s is often followed, or accompanied by, caring. And caring is what we need. “We want more people to be interested in birds,” Franzen says, “because when you create somebody who cares about birds, you create somebody who is concerned about the environment.”

We finished our birding and walked back to our cars. On the way, we saw a rookery in the distance with egrets and Roseate Spoonbills perched in number in trees. We couldn’t get close, I’m sure by design, but I saw flashes of vivid pink, some in flight, that left me stunned and exuberant.

Next time, as Robert Frost says, “You come too.”

April 4, 2025

A trip to another world

Saturday, I went to a remote part of south Louisiana, about an hour and a half from where I live, to the White Lake Conservation Area. White Lake is a large—55,527 square acres—freshwater lake just ten miles north of the Gulf of Mexico. It’s home to thousands of acres of freshwater marsh. Driving south down increasingly narrow roads, not seeing even a gas station for miles and miles, I had a lunar feeling of loneliness. The land is flat and wet and empty. I came to a place very few people want to, or can, be. It’s a wet prairie with vast horizons.

Every so often, after driving a mile or so, a small house appeared, isolated, defiant, mysterious. There are very few trees. You can see without restriction far into every direction. It’s landscape stripped bare. The sky has a large presence.

What the eye sees here.

What the eye sees here.Everything seems precarious about this land. It sits at some places just five feet above sea level. It feels more like actual sea level. This in a part of the country that’s prone to hurricanes. With little to protect the land and its few people from great winds and storm surge, security is a word I wouldn’t imagine is applied often here.

Still, there’s a sense of adventure, a kind of thrill, in exploring a landscape that’s so severe and underpopulated a mere 90 minutes from where I live. I wonder what it’s like to grow up in one of these few, isolated houses, nothing around you for miles except flat, wet land. As a kid, a first visit to a large city like Lafayette must be astonishing.

The last “town” I passed is called Gueydan. The sign posted as I entered says, “Duck Capital of America.”

My destination was the ranger station for the White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area where we—Acadiana Master Naturalists in training—will meet.

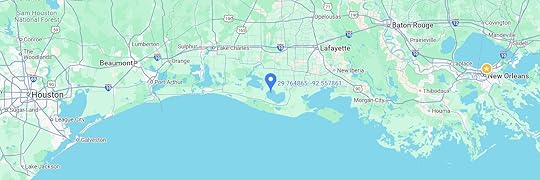

White Lake, center, with blue balloon marking it.

White Lake, center, with blue balloon marking it.Twelve of us assembled before the station house at about 9:30AM. The sky was heavy. We all brought raingear and boots in case, because part of the day will be a walk down a nature trail. Several of us are birders, and we were hoping to see one of the many species that reside here, the most famous of which is the Whooping Crane. I hadn’t done any research before my visit, so I didn’t know about the Whooping Cranes here. It was a surprise. I hadn’t thought about Whooping Cranes in years.

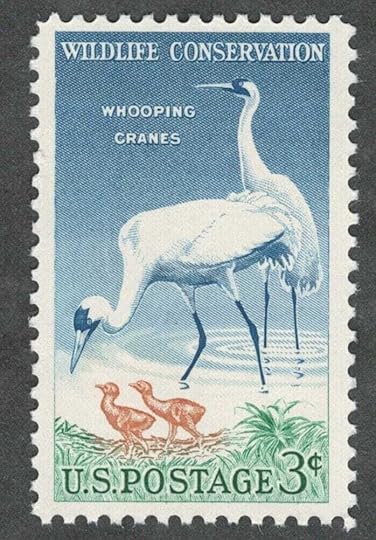

Someone my age—79—or thereabouts—may recall the effort to save the Whooping Crane, which is native to America, many years ago in the late 1950s and 1960s. Thinking back, I don’t know of any other conservation effort in that era that captured the nation’s imagination like that one. There was a concerted effort to save this animal from extinction. How did this sense of urgency come about? What roused the country to be so obsessed about a bird? We weren’t, Americans,—with some exceptions—hugely occupied with the environment. I remember, as a teenager, the sense of alarm I felt learning that only a few of these Whooping Cranes—such a strange name, I thought—were left. Worry was in the air. I, a self-obsessed American teenager, was worried. The US even issued a stamp in 1957 featuring Whooping Cranes.

The slow but steady effort to stabilize and increase the Whooping Crane population began in earnest. It was, in the scope of things, successful. The number in America went from 23 in 1941 to 600 today. That story of that effort includes remarkably inventive strategies, including an ultralight aircraft used to establish a migration route of the Whooping Crane between Wisconsin and Florida. You can find out more about this extraordinary effort here.

The Whooping Cranes at White Lake were introduced. They’re part of a long-term plan to help restore the general population in Louisiana. There once were Whooping Cranes that lived and bred in this area, but by 1950 there were no more. In 2011, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries began a reintroduction project. They released 10 juvenile Whooping Cranes, bred from eggs from birds in captivity. Today, there are 82 Whooping Cranes living and breeding in the White Lake Wetlands.

We learned all about this during a presentation that morning by Lance Ardoin, a Biologist Manager for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries. He detailed the history of the White Lake Conservation Area, including information about its nesting Whooping Cranes. We were not allowed to visit the nesting area, which, I think, was a good idea.

Above, a juvenile Whooping Crane being released in the White Lake marsh area. The person holding the bird is dressed entirely in white so that the bird will not become familiar with—and possibly unafraid of—humans in everyday dress. We want these birds to be wary of humans and to avoid us, thus giving them a better chance to survive. In the past, as we know, animals encountering humans for the first time had their trust mortally betrayed.

Below is a two-minute video of Whooping Cranes at White Lake. You can hear their distinctive call, which gives the bird its name. The brownish bird is a juvenile.

Ardoin said that years ago, this area, before it was a refuge, was a highly desired location for duck hunters, including the famous. “Lyndon Johnson was here a few times,” he told us. “And some Saudi princes.” The area is self-sustaining. That is, they have to pay their own expenses, and they do that partly by issuing duck hunting permits for certain times of the year. What they have done is create a symbiotic relationship with hunters that allows them to continue their work with the income they receive. It’s either that or shut down. Hunters are not allowed in the Whooping Crane nesting area.

After his talk, Ardoin led us on a walk down a nature trail.

Lance Ardoin leading us on a nature walk. He looks like someone who should lead nature walks.

Lance Ardoin leading us on a nature walk. He looks like someone who should lead nature walks.We didn’t see many birds, probably because we were a talkative group of twelve, and Ardoin periodically stopped to tell us about the native and invasive plants growing there, speaking loud enough so the entire group could hear.

It began to rain just as we finished our walk. I got into the car, and it started pouring. Louisiana rains can be severe. The GPS led me down hardly-traveled country roads, a different way than I took coming. It felt gothic. Dream-like.

My fifteen-year-old self encountered my seventy-nine-year-old self abruptly that Saturday. At a certain point as a teenager and young adult, I let the Whooping Crane slide from my mind, as other issues, many slightly reckless and immature, captured my attention. During that sixty-five-year interlude, though, others, more resolute, kept Whooping Cranes top of mind. They did, and are doing, the work. I drove home, optimism filling the air.

March 28, 2025

Astoria

I spent the last four days in Astoria. It’s part of New York City, specifically, of Queens. Do you know anything about it? Have you ever been there?

I lived in New York for thirty-five years, and I have to admit I only went to Astoria a few times, mostly for Greek food. There is a part of Astoria, in and around Steinway Street particularly, that’s heavily Greek and has lots of, well, Greek restaurants.

Suffice it to say, I don’t—or didn’t—know Astoria well. That is, until my daughter moved there a few years ago. And until a good friend, David Smith, rented an apartment in Astoria and graciously lets me stay there when I come to New York.

It’s a pretty name, when you think of it. Three vowels in so short a space gives it a musical, almost Italianate sound. As-tor-i-a. You could sing it. It’s almost an anthem.

Here are some maps, getting progressively more microscopic, showing Astoria and where it is in relation to the Bronx, Manhattan, Brooklyn and the rest of Queens. FYI.

My friend’s place is across the street from Sotto la Luna.

My friend’s place is across the street from Sotto la Luna.Astoria is a middle class enclave, for the most part. You don’t see a lot of trappings of wealth there. You see small stores, working people, nothing terribly fancy. You could say that’s ironic, since Astoria was named after John Jacob Astor (1864-1912, Titanic casualty), one of the world’s richest men at the time. Local officials thought, with this naming gift, Astor would invest in the area. He did not. The name remained, though.

Some parts of Astoria, in fact, are a bit grimy. Not all. There seems to be a difference in the look of Astoria north of the Grand Central Parkway, the road that leads to and from the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (forever known to old timers like me as the Triborough Bridge) that runs through it. It’s a bit nicer north of the GCP. I stayed on the south side.

The street where I stayed in Astoria

The street where I stayed in AstoriaAstoria is a place of neighborhoods, some more appealing than others, but all, in their way, to human scale. When I walk its streets, I see working people. I see mothers with shopping carts, I see students. Hardly anyone is dressed like the typical suited businessman or businesswoman you encounter so frequently in Manhattan. And you don’t see any inventively-dressed young people looking so cool sartorially it makes you feel painfully plain, as you would, say, in Brooklyn. People in Astoria dress for the job. You sense struggle here. The daily hours put in for daily bread. The edges are rough. Family is big.

You can still, like Manhattan and Brooklyn, find an array of ethnic foods here, though. It’s not monochrome. In my little neighborhood alone, I found Bangladeshi, Brazilian, Dominican, Indian, Italian, Greek and even a Welsh restaurant. I can travel metaphorically here.

My first stay in Astoria a few years ago, I didn’t find it that appealing. It seemed undistinguished, somewhat dull. My opinion changed. I grew to be very fond of its ordinariness. Of its unpretentiousness. It’s more likely that a locksmith lives here than a hedge fund manager. If you feel comfortable with middle class people, you feel comfortable in Astoria. You do see young people here, though, from outside New York, here for the cheaper rents and the ease.

It’s not that densely pedestrian compared to Manhattan, either. Walking its streets is a pleasure. Not once did I have to stop, dodge, shift, defer or adjust to another pedestrian coming my way because there was not enough room for both of us. That’s standard in Manhattan. You can feel like you’ve run an obstacle course after just a five-minute walk in Manhattan. It’s exhausting.

Typical Astoria houses.

Typical Astoria houses.A funny thing happened to me this trip. All of my thirty-five years in New York I lived in various parts of Manhattan. So, yes, on this trip I took the subway—the N Train, to be specific, the stop 36th Avenue—to Manhattan. I went to the Metropolitan Museum. I went to Chinatown. I met an old friend, and we went to an exhibit at the New York Public Library.

But twice, when I had intended to take the train to Manhattan—not a long ride, by the way—I changed my mind and stayed in Astoria. I just didn’t want to fight the aggression, the crowds and the pace, the furious energy of Manhattan. I walked around my neighborhood instead. I visited my daughter in hers. I was relaxed, I was calm. I didn’t want Manhattan. I wanted Queens. I wanted Astoria.

March 21, 2025

Pick your shame gurus carefully

I sometimes think the gurus who give their Ted Talks about shame have never experienced real shame. In my experience, they seldom tell the deep truth about their past, about their own shame—if it exists—in front of their rapt audiences. They do tell you about how many views they’ve had.

At a certain point, I’ve found these Ted Talkers sense they’ve become full-fledged stars. They begin to act and talk that way in front of you, with a kind of assumptive flair. They’re just a few steps away from wearing some kind of robe. They love their job. They love to perform. If they help you, all well and good.

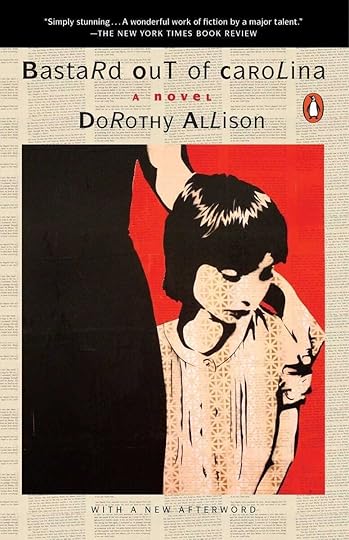

One person I know of who wrote and spoke about shame truthfully, candidly and unflinchingly was the writer, Dorothy Allison. She died recently. I believe she deserves a very high place among people who try valiantly to contend with their shame. It can be a lifetime battle. Those who have experienced real shame know what I mean.

When Dorothy Allison died, Terry Gross played an interview with her from 1992 after the success of her harrowing book, Bastard Out of Carolina. I hope you listen to the interview. (Or read it; there’s a transcript.) Allison’s voice is calm, full of grace, and she has wisdom to impart. Wisdom she earned at a high cost. Her stepfather began abusing her when she was five. It continued for years.

The late Dorothy Allison. She never gave a Ted Talk.

The late Dorothy Allison. She never gave a Ted Talk.Dorothy Allison talks about the difficulty of reconciling pleasure you feel when an adult is abusing you:

“So if a child begins to feel erotic excitement while being manipulated by an adult, does that give the adult permission to do it? It’s a horrible thing to even imagine. And you don’t - part of the reason to keep it a secret and to be quiet about that feeling is that you might give someone any small measure of encouragement to feel they have a right to do this. They have no right ever to sexually touch a child. It’s just not possible to do. There’s no justification for it. And the fact that the child might, in fact, manufacture some erotic excitement is not a justification for it. But if we pretend that it doesn’t happen, then that guilt, that self horror, stays - never goes away.”

It was a lifetime struggle for her:

“I began to think that I was this terrible person. I was being told I was. And it’s taken me most of my life to make the decision that that’s not the case.”

When I went to prep school as a kid, two teachers abused me. In both cases, what they did felt good—then bad—and I didn’t know how to reconcile this with the infringement and the betrayal. Dorothy Allison was not there to explain this to me. I never told my parents for fear they would find me at fault or somehow the one who caused it. I carried that shame with me for years. I still do.

What do we do with this shame inside of us that comes from feeling unasked-for pleasure? What do we do when there are conflicting emotions that are too big and unwieldy for us to sort out? The experts who walk the stage confidently and purposefully tell us not to feel shame, but they often haven’t revealed to us the confusing pleasure they might have felt when they were abused, and the self-loathing that followed. So, I would think twice about trusting their advice. They may say, “I know shame,” but I wouldn’t just take their word for it.

Not when you have someone as fearless and openhearted as Dorothy Allison who bears her soul and stands before you and says, “I see how hard this is. I know. I was there.”

March 14, 2025

Weary of the tough dad

I’m tired of the tough dad.

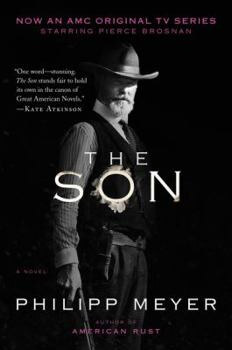

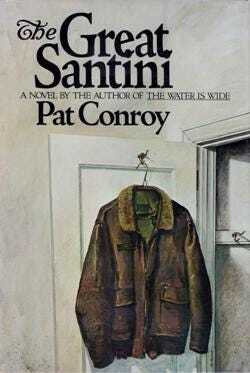

The patriarch who wields his authority over a son or sons—because it’s usually the males he directs his abuse at—harshly. “The Yellowstone” fathers of the world. You encounter them in movies and in books and on TV, not to mention in real life. Tired of the Great Santinis, tired of books like The Son, with its belittling father, tired of the romanticism of the larger-than-life man who drinks and comes back and beats his children because of some “demons” inside him. The glorification of that, like the glorification of thugs in motorcycle gangs. Hollywood loves a savage father.

We’ve all seen them, the children of these belittling fathers. They’re self-loathers. (And, yes, the recipients can be women, too.) Sometimes, their self-hatred is painful to see. We’ve heard them say, “I’m a piece of shit.” We’ve seen the person who sabotages their own progress and potential as if they were destroying their home with explosives. Someone wrenched their self-esteem from them. Often, it’s a father who has repeatedly told them they’re worthless. Maybe you’ve seen that kind of father in action yourself. It’s hard to avoid meeting them in this life. Maybe he was yours. He was mine.

We’ve all heard this: you can’t love someone until you love yourself. I’d add it’s hard to do anything fulfilling in this world if you don’t love yourself. If your self-love is taken by force from you, by some cowardly, browbeating father, you flounder, you stall, you never fly. You limp.

These humiliated children try their best to make their way through life, but something’s missing. A gap from the thing that was taken. They do their best, and some, miraculously, actually do well. How, I can’t begin to say, but they overcome. So many don’t. The houses they build are on spongy ground. They build them, but the structures are wobbly.

I once went to live in a small village in the South of France. It was rural, with barely 200 people. The villagers worked the land and, mostly, didn’t stray far from their insulated village. The place seemed outside of time, completely apart. I found little in common with my own experience in New York City where I’d come from.

I met a young man in that little village, a sort of jack-of-all trades. His father owned a small vineyard but, by the standards of the other villagers, was not terribly successful. The son, about thirty, stuttered, and his eyes twitched when you talked to him. When I met his father, I understood why.

One day I was playing boules, the game of tossed steel balls played everywhere in France, with other villagers. I, a novice, tossed my ball very far from the mark.

I heard a voice. I felt it.

“Richard est nul,” the father said. “Nul.”

“Richard is nothing, useless.”

I turned and saw that smile of his. He was pleased at my failure.

He said it again, looking at me, smiling, “Richard est nul.”

There he was, in that remote village. There he is, everywhere.

March 7, 2025

In love in Paris

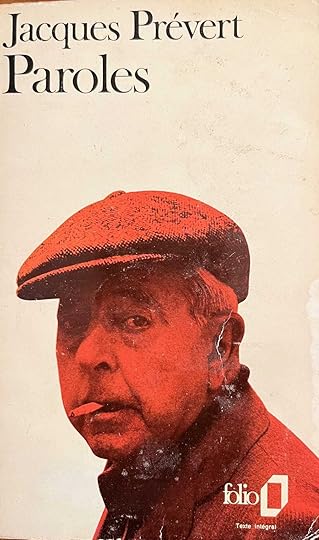

When you are young and in love and you travel to Paris, you may, as we did, have a book that becomes a part of your stay as much as any bistro, walk, museum or park. It enlarges your time and binds you and the city together as surely as a kiss. Especially if you discover the book while you’re there. Especially if the two of you fall in love with the book for the same reasons. For us, it was Jacques Prévert’s book of poems, Paroles. It came to be an essential Paris for us, the words, not so hard to understand, the sentiments, pure and openhearted.

The book is like a song that brings back the places and streets you loved.

My copy

My copyJacques Prévert was born in 1900 and died in 1977. He was primarily a poet and a screenwriter. Some of his poems were set to music, most famously, “Les Feuilles mortes,” which, in English, became “Autumn Leaves” with new English lyrics by Johnny Mercer. I prefer the French version, particularly as sung by Yves Montand. This is about as silky as you can get. What a voice.

There’s a rabbit hole we could go down here, following Montand from Édith Piaf to Marilyn Monroe, but, no. It’s Prévert I want to talk about.

Jacques Prévert was a popular poet. Paroles, his first book, published in 1946, did very well. One figure I found says it sold 500,000 copies. For a book of poetry! Popular poets are usually mistrusted—any popular artist often is. I don’t know what the French think about Jacques Prévert. I don’t care. I like his poems very much.

So, I won’t assess the quality of his poetry. As Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who translated Paroles, says about Prévert, his is “a poetry (his worst critics will tell you)…existing always on as fine a line between sentiment and sentimentality as any that Charlie Chaplin ever teetered on.” You decide.

Prévert’s a street singer, a man who you walk with, the man with an accordion, a man who speaks to you at eye level, who takes a glass of wine with you.

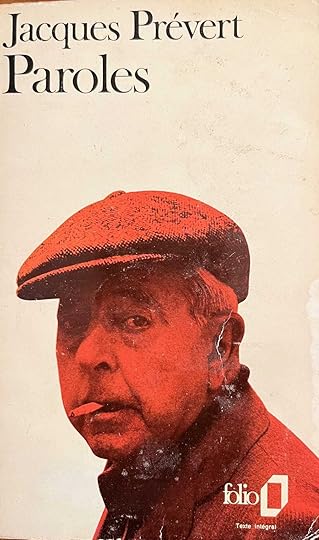

No one smoked as grandly as Jacques Prévert

No one smoked as grandly as Jacques PrévertWhen the two of you fall in love with poems written in the language, French, of the city you are wandering in, Paris, then they become essential to you, part of your heart. They provide you with an extra portion of fondness for the time you spend in Paris. You belong to the city more genuinely, and the city belongs more surely to you. Because that’s what can happen in Paris. You can fall in love with it, as we did, deeply and passionately, with Paroles our companion and witness.

I see the bookstore on Rue des Écoles in the 5th arrondissement where we bought the book still exists (the store’s label is affixed in the inside cover of the book), and that makes me happy.

I can look back and say, we found that book in Paris. Or it found us. I can read the poems once again, “Rue de Seine” and “Je suis comme je suis.” We read those poems to each other aloud at a cafe somewhere in Paris. The book was our guide. Jacques Prévert was our walking companion. One of us carried the little folio paperback with us always.

Years later, that love is gone and stone cold, and I am in love with another. (I am deeply in love with my wife, and she knows this.) I can still come upon that book, and it will transport me back to the Paris of years ago when Jacques Prévert and she and I and Paris were together. Anything this deeply felt is glorious. The soul aches in a kind of unappeasable ecstasy of melancholy. What you had, what was, what was lovely, what is gone.

Jacques Prévert and love in Paris

When you are young and in love and you travel to Paris, you may, as we did, have a book that becomes a part of your stay as much as any bistro, walk, museum or park. It enlarges your time and binds you and the city together as surely as a kiss. Especially if you discover the book while you’re there. Especially if the two of you fall in love with the book for the same reasons. For us, it was Jacques Prévert’s book of poems, Paroles. It came to be an essential Paris for us, the words, not so hard to understand, the sentiments, pure and openhearted.

The book is like a song that brings back the places and streets you loved.

My copy

My copyJacques Prévert was born in 1900 and died in 1977. He was primarily a poet and a screenwriter. Some of his poems were set to music, most famously, “Les Feuilles mortes,” which, in English, became “Autumn Leaves” with new English lyrics by Johnny Mercer. I prefer the French version, particularly as sung by Yves Montand. This is about as silky as you can get. What a voice.

There’s a rabbit hole we could go down here, following Montand from Édith Piaf to Marilyn Monroe, but, no. It’s Prévert I want to talk about.

Jacques Prévert was a popular poet. Paroles, his first book, published in 1946, did very well. One figure I found says it sold 500,000 copies. For a book of poetry! Popular poets are usually mistrusted—any popular artist often is. I don’t know what the French think about Jacques Prévert. I don’t care. I like his poems very much.

So, I won’t assess the quality of his poetry. As Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who translated Paroles, says about Prévert, his is “a poetry (his worst critics will tell you)…existing always on as fine a line between sentiment and sentimentality as any that Charlie Chaplin ever teetered on.” You decide.

Prévert’s a street singer, a man who you walk with, the man with an accordion, a man who speaks to you at eye level, who takes a glass of wine with you.

No one smoked as grandly as Jacques Prévert

No one smoked as grandly as Jacques PrévertWhen the two of you fall in love with poems written in the language, French, of the city you are wandering in, Paris, then they become essential to you, part of your heart. They provide you with an extra portion of fondness for the time you spend in Paris. You belong to the city more genuinely, and the city belongs more surely to you. Because that’s what can happen in Paris. You can fall in love with it, as we did, deeply and passionately, with Paroles our companion and witness.

I see the bookstore on Rue des Écoles in the 5th arrondissement where we bought the book still exists (the store’s label is affixed in the inside cover of the book), and that makes me happy.

I can look back and say, we found that book in Paris. Or it found us. I can read the poems once again, “Rue de Seine” and “Je suis comme je suis.” We read those poems to each other aloud at a cafe somewhere in Paris. The book was our guide. Jacques Prévert was our walking companion. One of us carried the little folio paperback with us always.

Years later, that love is gone and stone cold, and I am in love with another. (I am deeply in love with my wife, and she knows this.) I can still come upon that book, and it will transport me back to the Paris of years ago when Jacques Prévert and she and I and Paris were together. Anything this deeply felt is glorious. The soul aches in a kind of unappeasable ecstasy of melancholy. What you had, what was, what was lovely, what is gone.

February 27, 2025

Rain

It’s been raining for hours here in south Louisiana. It rained all night, and it’s still raining. Our front lawn is half flooded, with newborn lakes established here and there. At least twenty robins are scattered over this sodden earth, taking advantage, I would guess, of easier access to worms or grubs. The rain hasn’t put a damper to the crowd of American goldfinches that come to our feeders every day. Rain be damned, they’re gobbling away at the fallen seeds on the ground.

Front lawn with robins

Front lawn with robinsWhen it rains, I feel the world has been cleansed. That we have been given a new chance to get things right. That all the dirt, both real and figurative, has been washed away. When rain falls, I always feel a kind of absolution. It means I can start anew. It's a kind of recurring baptism.

The sound of rain is soothing, a lullaby. No wonder there are tapes of rain falling to help people sleep. The slap of rain on fall leaves stirs the heart. The slant of rain. The need for rain. The comfort of rain.

I have our front door open to it. I can feel the freshness of the rain waft into the room where I’m working and I can smell the freshness as well. The way you can breathe rain even indoors.

Rain can go awry, but it shouldn’t be judged for that. Anything in nature can shift from being benign to dangerous. Yes, there are rains that are not pleasant. I think of cold windy rainy March days in New York City. Or when you're driving at night and the rain is so brutal you can’t see even beyond your windshield and your heart is about to exit your body.

All in all, though, everything about rain is replenishing and poetic. It’s not a coincidence that Ernest Hemingway begins his memoir about Paris, A Moveable Feast, in rainy weather. This is a cold, sad-producing rain, but nevertheless an inspiring rain. He walks from his apartment to the Place St-Michel to a good cafe. He takes off his damp coat, sits down, and writes:

“A girl came in the cafe and sat by herself at a table near the window. She was very pretty with a face fresh as a newly minted coin if they minted coins in smooth flesh with rain-freshened skin.....”

If rain accompanies strong sensual moments, then you live a poem, you’re fully alive. In college, I was in love with a beautiful, melancholy girl. Her name was Sarah. I remember one afternoon, together, in bed. I remember it started to rain. I remember the sound of the rain slapping against the leaves on the ground and the damp smell of it breathing into the window and cooling our bodies. My arm was draped around her bare shoulder. The cascade of her soft hair fell onto my naked arm. I often think about the soft sound of the rain against the windowsill and on the leaves on the ground. Of us in bed together as we talked dreamily to the tat-tat-tat of rain against the leaves.

If we think about the wonders of being alive, so many are simple, straightforward. Rain is one. Replenishing, cleansing, encouraging. Making us poets for at least an hour or so. The beauty of those drops coming from the sky. The mystery of it. There are things in this world that are dark. Rain is not one of them.