Richard Goodman's Blog, page 7

July 17, 2024

The green beans aren't salted

November 25. Today, we went to an all-day, post-Thanksgiving celebration in Jefferson Davis Parish in southwestern Louisiana. (Counties are called parishes in Louisiana.) This part of Louisiana is rice country. The land is flat and, for the most part, there are no trees. It’s called the Cajun Prairie, and when you drive through it, mile after mile after mile, you might well think you are in Kansas or in one of the Dakotas. That kind of landscape, flat and forever, made me feel a bit lonely in an exquisite way.

My wife, Gaywynn, and I were invited as guests by the family she had nannied for in the past and who had since moved away. They are a sweet couple, with two little girls. They’d come home for Thanksgiving and invited us to this grand fete.

It was a gorgeous day, in the mid-sixties; the sun was strong, and there was little wind. We drove through the voice-quieting level land until we turned down a narrow country road and reached our destination.

It was a compound of small houses leading to a large, open-ended barn. Over 100 people were gathered there, drinking and eating and enjoying the day. There was a long table overwhelmed with food: gumbos, stews, pulled pork, various slaws, sweet potatoes, dishes I didn’t recognize, more than I or anyone could eat. The sun spilled into the barn, and its warmth and brightness was mirrored by the mood of the people. We found Gaywynn’s former employers and stayed and talked with them for a while and then sat with plates and ate and met some new people.

Then came the music. There was a bandstand, and about 2p.m. musicians made their way there. They were, except for one man, African American, and the music they were going to play was Zydeco. The band was Joe Hall & The Louisiana Cane Cutters.

Joe Hall, with accordion, and his Cane Cutters

Joe Hall, with accordion, and his Cane CuttersZydeco is “a music genre that blends blues, rhythm and blues and music indigenous to the Louisiana Creoles.” The origin of the word is uncertain. One theory is that it’s derived from the French phrase, les haricots ne sont pas salés, which means, “the green beans aren’t salted.” When pronounced, it sounds something like the word “Zydeco.” Perhaps. This phrase was used to express hardship: when you don’t have enough money for salt, things are tough.

Zydeco is mainly, but not solely, played by African American musicians. The most famous of these was probably the late Clifton Chenier. Its main instrument, the centerpiece, is the accordion.

The band began to play. Immediately, the man who owned the barn and all the outlying buildings and who was at least in his sixties, got up with his wife and began to dance. He was soon followed by other couples. Most of them were in their fifties or sixties, seventies and older.

Zydeco is one of the most danceable forms of music you’ll ever encounter. The couples knew how to dance and had probably done it all their lives. They grew up with it. They spun around the floor smoothly.

I had been feeling a bit blue about this whole aging thing lately. (I’m 78.) And the slow segregation you begin to experience as an older person. Your world gets smaller and smaller. Once, for example, you felt comfortable in bars. Then, one day, you walk into a bar and find no one remotely your age. So, you leave. This is the same for many places, events. We’ve all felt excluded with looks and body language at one time or another for various reasons.

This is accompanied by a general feeling that you are no longer competent as a person. This is called ageism. It’s also called getting old. Eventually, you may find yourself conversing, mingling, socializing uniquely with people your own age, like some kind of restricted country club from the 1950s, except instead of rejecting blacks, Jews, Catholics, Italians or whomever, the world in general doesn’t want the pleasure of your old, white-haired, mottled-skin self.

I’m not telling you anything new or that you haven’t heard before.

Hearing about it, though, and experiencing it are two different things. My reaction to all that is one of sadness and anger. Sad, because I don’t want to be excluded from anything joyful. Anger, because how dare you 20s, 30, 40s-somethings tell me I’m not wanted. I’m powerless, though, to change that.

Gaywynn read these words and got teary. “I don’t want you to buy into this,” she said. I don’t. I feel young inside. I have energy to spare. But I can’t control the outside world.

I was talking to a friend the other day, a woman about ten years younger than I am, but still in the “older” category, about all this. She said that ageism is the only “ism” that is still acceptable to practice. She said that people are still able to make fun of old people. Ageism isn’t woke. It’s still sleeping, or nodding off, or napping.

Which leads me back to the barn where Gaywynn and I were watching the people dance to Joe Hall & The Louisiana Cane Cutters. When was the last time I saw older people dancing like this? With panache, pleasure, skill? Not shuffling around listlessly but with brio. At a wedding, perhaps. Other than that, nowhere.

It struck me how beautiful it was. Here they were, older couples dancing at a party, and it all seemed right. What made it all the more lovely was that the older couples were dancing amongst a crowd of younger people. This was everybody dancing. There was no ageism at this party. Gaywynn and I danced with the others. I thanked Zydeco and this part of Louisiana gratefully and sincerely.

When you don’t see something for a long time, like people of all ages dancing together, and then you do, it’s something that makes you feel alive. The world becomes full of possibility.

Here, it was as it should be. People, all of us, together, living life, living life, living life.

July 11, 2024

Happy birthday

79 today.

Only a number. Hear this a lot.

Does it have to be such a big number?

Cue laughing-so-hard-I’m-crying emoji.

Seriously, folks.

The main thing not to forget is that I’m here. I’m able to take a deep morning breath.

Importantly, then another.

My wife Gaywynn said to me yesterday, caringly, that I tend to spend too much time looking to the past, trying to resurrect things that are gone. Long gone, often. I have, she said, much more to say.

Light bulb.

That’s usually the case when something is there in front of you, staring you down.

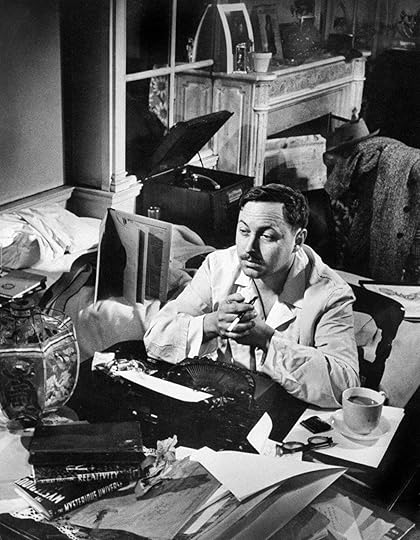

I’m writing a piece about Tennessee Williams. Much to admire about the man, but one aspect of his character that I return to again and again is that he did not dwell in the past.

His motto, that he repeated again and again in his notebooks and letters, especially when things were not looking particularly good, and that he lived by:

En avant!

Forward!

That’s the spirit.

July 5, 2024

A Pilgrimage to Algiers

It was a late January day in 2015 in New Orleans. My friend Alex Jones and I boarded the ferry to Algiers, on the west bank of the Mississippi, just across from New Orleans, to find the house where a celebrated writer once lived. The ride across the river was short and pleasant. The sun was out. The temperature was in the low 60s. The ferry nudged into the terminal, and we disembarked. It was a good day for walking. The house, on Wagner Street, was about a mile from the terminal.

We walked past sweet-looking houses on Algiers Point, then followed the road that hugs the Mississippi and, some thirty minutes later, turned inward. We walked a few blocks more, and there it was.

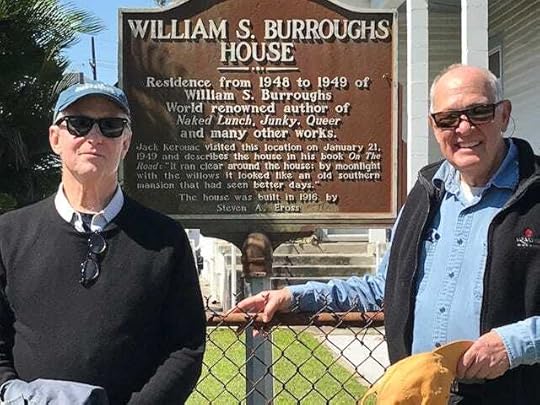

It was a small shotgun with thin columns, in need of care, with a chain link fence enclosing it. The neighborhood was undistinguished, with few trees. There was a standing plaque that told the world who had once resided there.

It read, “Residence from 1948 to 1949 of William S. Burroughs. World-renowned author of Naked Lunch, Junky, Queer and many other works.”

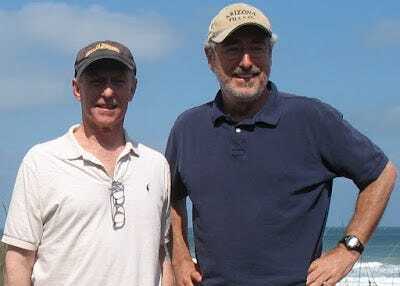

The author, left, with his good friend, Alex Jones.

The author, left, with his good friend, Alex Jones.As we had walked toward the house, Alex and I talked about a day over forty years earlier, in the fall of 1972, when we’d both come to 8 Duke Street in London, not far from Hyde Park, to visit William Burroughs. I remember how nervous I was as I pushed the buzzer next to the name, “Burroughs.” Suddenly, I heard his voice, a low growl, for the first time, through the intercom,

“Yesssssss.”

My own voice raising an octave to a near-squeak, I replied, “It’s Richard Goodman! From America!”

There was a long pause. I looked at my friend Alex wildly. Then the voice said, “Come on up.”

We ascended the stairs to the third floor, and I knocked on the door. It opened, and there he was, William S. Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch, Junky and many other books, so-called father of the Beat Movement, mentor to Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, infamous drug addict, cult figure and a unique presence in American literature. He was smaller than I expected and wore a black turtleneck and slacks.

“Come in,” he said, waving a slow, low hand toward the inside. He turned, and we followed him into the apartment.

Now, so many years later, on that January day in 2015, we were traveling back and forth through time. We were standing before a house where Burroughs lived for a year, in 1948-49. That was sixty-five years ago. We were remembering a London visit forty-three years ago. Burroughs had died in 1983. This was 2015. It was slightly disorienting.

The house we were looking at is described by Jack Kerouac, who, with Neal Cassidy, visited Burroughs there on their legendary cross-country journey that would later be included in Kerouac’s classic book, On the Road, published in 1957. Kerouac and Cassidy took the same ferry we did from New Orleans to Algiers Point. In the novel, Kerouac calls Burroughs “Old Bull Lee.” (William Lee was a pseudonym Burroughs used on some of his earlier works, including Junky.) Kerouac writes,

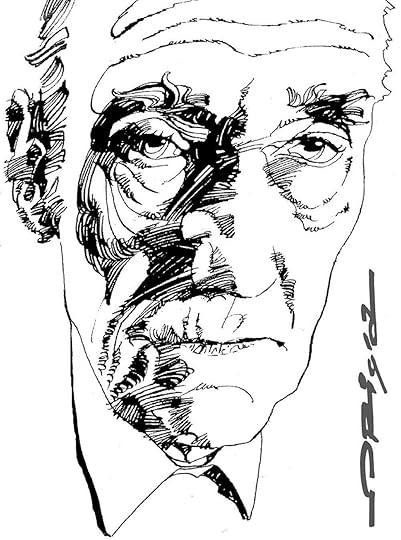

Drawing of Burroughs by Origafoundation, Creative Commons

Drawing of Burroughs by Origafoundation, Creative Commons“We went to Old Bull Lee’s house outside town near the river levee. It was on a road that ran across a swampy field. The house was a dilapidated old heap with sagging porches running around and weeping willows in the yard; the grass was a yard high, old fences leaned, old barns collapsed. There was no one in sight. We pulled right into the yard and saw washtubs on the back porch.”

The Burroughs they visited hadn’t written Naked Lunch yet, or anything else, really. But he was a charismatic figure. Kerouac and Ginsberg met him in New York City a few years earlier, and he became a mentor to them. This is how Kerouac describes his allure in On the Road,

“It would take all night to tell about Old Bull Lee; let’s just say now, he was a teacher, and it may be said that he had every right to teach because he spent all his time learning; and the things he learned were what he considered to be and called “the facts of life,” which he learned not only out of necessity but because he wanted to. He dragged his long, thin body around the entire United States and most of Europe and North Africa in his time….He was an exterminator in Chicago, a bartender in New York, a summons-server in Newark. In Paris he sat at cafe tables, watching the sullen French faces go by. In Athens he looked up from his ouzo at what he called the ugliest people in the world. In Istanbul he threaded his way through crowds of opium addicts and rug-sellers, looking for the facts. In English hotels he read Spengler and the Marquis de Sade…. Now the final study was the drug habit. He was now in New Orleans, slipping along the streets with shady characters and haunting connection bars.

“He spent all his time talking and teaching others. Jane[his wife] sat at his feet; so did I; so did Dean [Neal Cassidy]; and so had Carlo Marx [Allen Ginsberg]. We’d all learned from him. He was a gray, nondescript-looking fellow you wouldn’t notice on the street, unless you looked closer and saw his mad, bony skull with its strange youthfulness – a Kansas minister with exotic, phenomenal fires and mysteries. He had studied medicine in Vienna; had studied anthropology, read everything; and now he was settling to his life’s work, which was the study of things themselves in the streets of life and the night.”

The household at 509 Wagner was chaotic. Burroughs, heavily addicted, lived with his wife, Joan Vollmer, also addicted, who he would later kill in Mexico. There were also two young children, one his, and the other hers from a previous relationship. The kids ran wild. There was little food in the house. Burroughs, Kerouac and Cassidy took several trips to New Orleans to scour the bars and, for Burroughs, to look for a fix.

Reading about the visit a sense of squalor runs throughout, yet Kerouac still writes about Burroughs worshipfully. It’s all surreal, flowing with the energy of youth and travel and the strong, odd, unrelenting personalities who were there in the week or so the visit lasted.

Kerouac and crew departed after about a week, and, not long after, Burroughs went to Mexico, one step ahead of the police. One drunken night, he shot and killed his wife in what has been described as a William Tell-like stunt. He fled Mexico to avoid jail. He eventually landed in Morocco where Kerouac and Ginsberg visited him and helped him prepare the manuscript of Naked Lunch.

Photo by Kim Ranjbar

Photo by Kim RanjbarHow did I find myself in 1972 walking in the door of Burroughs’ London flat, a young man of twenty-seven, an aspiring writer, who like Burroughs in 1948 in Algiers, had written very little and published nothing to speak of?

I first read Naked Lunch in 1968 when I was a graduate student at Wayne State University in Detroit. I fell under its spell. I can still hear myself, laughing hard at passages in the book in my cheap student apartment on West Willis in Detroit. I was a convert. I immediately enlisted in the corps of Burroughs admirers and acolytes. After reading Naked Lunch and its predecessor, Junky, I decided I wanted to write my master’s thesis on Burroughs’ work.

When I told my advisor, he was stunned and horrified.

“You mean the William Burroughs who wrote Naked Lunch?!? The drug addict?”

Yes, that’s the one. And yes, I do.

Credit to him, my advisor. He reluctantly said yes.

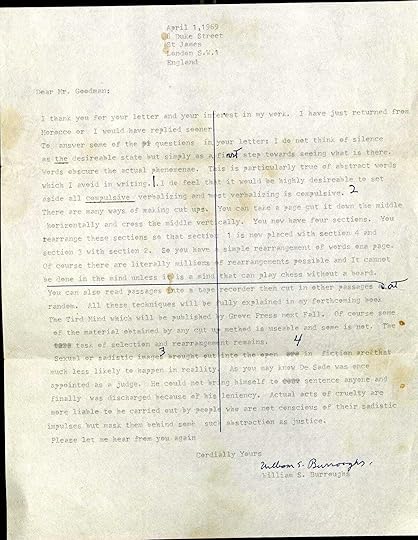

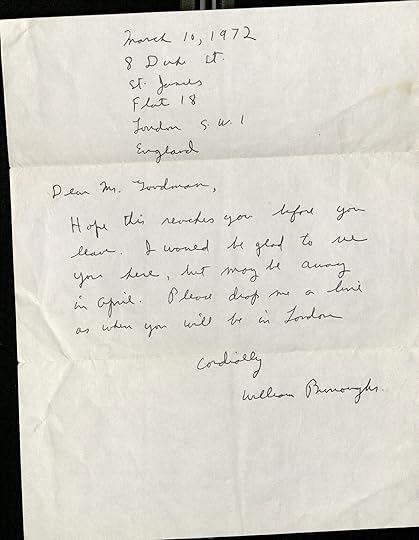

In the process of writing and researching my thesis, I decided, on a whim, to write Burroughs a letter in care of his publisher. I asked him a few simple questions about his work. I had no idea where he was or what he was doing. Three months later, to my astonishment, I received a reply. Burroughs was living in London.

“Dear Mr. Goodman,” his letter, dated April 1, 1969, began, “thank you for your letter and interest in my work. I have just returned from Morocco, or I would have replied sooner.” He answered a few of my questions. It was a short letter, but at the close he wrote, “Please let me hear from you again.” So began an irregular correspondence between us that lasted about five years.

After I’d finished my thesis—and sent a copy to Burroughs—sometime in 1971, I decided to go to Europe with my friend Alex. I wrote William Burroughs telling him I would be coming to London and asked if I could stop by for a visit.

He said yes.

That’s how I found myself in front of his apartment door in London that fall day. I still find that hard to believe. I wrote a piece about that visit, which lasted far into the evening, a few years later. It was my first published piece, and it was because of William Burroughs. I saw Burroughs a few times after that, in New York, where he moved to from London. We lost touch, but I still have his letters and the memories of our visits, and I cherish both.

That January day in 2015, so many years later, we didn’t stay long at Burroughs’ old house in Algiers.

The thing about pilgrimages like this one is that the person who lived there is long gone, and you are really encountering ghosts. Nobody’s home, so speak—even literally, sometimes. You walk through, or gaze at, a phantom house. The emptiness can be deafening. So it was in Algiers, that warm day. Burroughs had been dead for over twenty years. He hadn’t lived in Algiers in seventy years.

But I was a pilgrim. I didn’t go to Algiers expecting to actually find Burroughs. I was there to pay homage. I was a devotee. If you want to see and visit with the occupants, they are alive and well in the pages of On the Road, and they always will be.

People go on religious pilgrimages to worship at the shrines of saints and martyrs. I don’t see much difference in what I did that day. They go to make a physical journey, often following in the footsteps of a saint or hero—or in my case, a writer—to their home or final resting place.

It’s a way of acknowledging your gratitude for their gifts to you. They have inspired, delighted, astonished, uplifted and comforted you. You want to publicly acknowledge that. You’re saying, “You once lived here, perhaps in obscurity, perhaps struggling, perhaps lonely and in doubt, perhaps even badly. I am here to give thanks to you and to pay homage.”

That’s what I did that mild January day in 2015 at 509 Wagner Street. I was a pilgrim.

June 28, 2024

Prophets

We have had, and have, some great prophets.

I mean prophets who have warned, cajoled, praised and cried to us about our environment. About the precious earth on which we live and which we seem determined to destroy.

These prophets, like the Biblical prophets, have not been listened to as often and carefully as they should have been. To our everlasting detriment.

They are, in my view, as holy as any Biblical prophet and their message is as urgent.

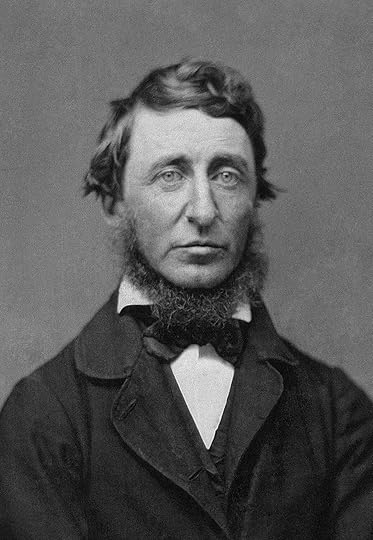

You could list many of them. Anyone who cares about our earth will have their own essential prophets they can name. You might begin with Thoreau. He wrote like a prophet—in maxims with an aggressive wisdom. But he directed our eyes to what was right before us, to the woods and lakes and animals at our door, and said that was all we needed.

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David ThoreauI would list Aldo Leopold, who wrote A Sand Country Almanac, published in 1949, who gave his comings and goings exactly the same significance and worthiness as those plants and animals on his Wisconsin farm.

Aldo Leopold

Aldo LeopoldI would list Rachel Carson, who wrote Silent Spring, published in 1962. She was a brave and highly principled writer. Her book was about the damage and danger of pesticides to birds, and though she was vilified by chemical companies and her science was challenged, everything she wrote was meticulously researched and sound beyond measure—and true. Her book led to the banning of DDT.

Rachel Carson

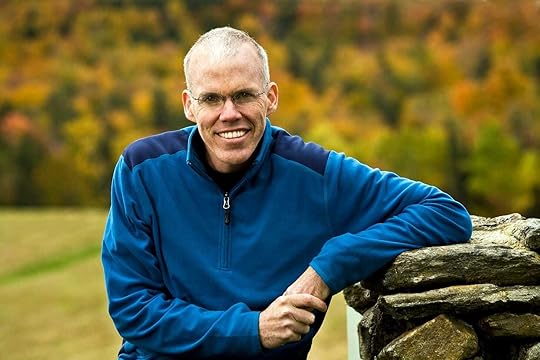

Rachel CarsonI would list Bill McKibben, a tireless advocate for our environment, starting with his prescient (a proper word for a prophet) book, The End of Nature, published in 1989. He has never stopped his efforts to make us understand the urgency of what we are facing, including his efforts as a founder Step It Up and 350.org.

Bill McKibben

Bill McKibbenI would list Elizabeth Kolbert, the learned storyteller whose pieces for The New Yorker have been collected into several remarkable books, The Sixth Extinction (a Pulitzer Prize winner) and Field Notes from a Catastrophe. Her range is extensive, her concerns endless, and her writing both lyrical and highly intelligent.

Elizabeth Kolbert

Elizabeth KolbertThese are our prophets. There are more. No one can ever claim they haven’t made us see our future, bravely and loudly, haven’t told us in so many well-written, persuasive words, “Repent! The End is Nigh!”

Listen to them. Listen to our prophets. While we can.

June 21, 2024

The reluctant writer of the Upper West Side

She was about five feet four, with thick brown hair that came to just below her ears. She didn’t pay much mind to it. Her skin was pale. She had brown eyes and largish lips that were always painted with the gaudiest orange lipstick. She was forever rubbing it off her teeth with a forefinger. She had a seemingly permanent case of cottonmouth. When you listened to her talk, all you wanted to do was to give her a glass of water. She constantly tried to fight the dryness by smacking her lips, moving her tongue about or swallowing. Nothing worked. Her mouth miraculously stayed dry all the time.

Jan.

She was part of our writers group in the early 1980s in New York. Decidedly Jewish, sweet, shy, very talented.

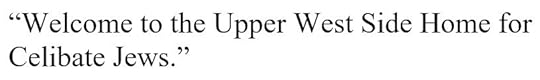

She had a lovely smile, lipstick or not. Not a huge or even a big smile but a smile that broke through her melancholy so that you saw for a brief moment there was light in her. (I don’t have a photo of her. I wish I did.) But most of all, she was funny. She cracked jokes. They were almost always self-deprecating. When she opened the door of her apartment, she might say,

“Welcome to the Upper West Side Home for Celibate Jews.”

When she got on a roll, it was almost always about her nonexistent love life or her self-proclaimed unworthy body.

“Yesterday I called a plumber to fix my sink,” I remember her saying once. “It wasn’t broken, but it was the only way I could get a man into my apartment.”

Her delivery was worthy of standup, and this was before standup became a cult.

“I’m still a virgin,” she said another time. Then the perfect little pause. “I’m holding out for the Messiah.”

She was a proofreader at Simon & Schuster.

“I can’t get you published,” she would say, “but I can correct your spelling.”

She wasn’t just a verbal comedian, though. She was a good writer who cared about words, who could make you laugh with the written word as well as with the spoken word. She wrote a great deal about her mother, about the twisted, co-dependent (we didn’t have that term then, so had to make do) relationship the two of them had in the past and still had.

“My mother was a fanatic about modesty,” she read to the group one day. “She put so many clothes on me I didn’t know I had breasts until I was twenty-eight.”

All of us were immensely fond of her. Jan came to the writers group for about six months. You could tell she was pathologically insecure. (“I don’t even think I have a right to open my own mail.”) A lot of comedians are, but she seemed especially so. She was doubtful about everything, including her own humor. She didn’t think she was especially funny. And of course she thrived on guilt, the ultimate nourishment for any female Jewish comedian. She feasted on it.

“I feel incredibly guilty about sex. I even feel guilty about sleeping with myself.”

I adored her. I felt protective of her. I wanted her to be great, to write a marvelous book, to become famous, to share her lovely spirit with the world. I did everything I could to encourage her—we all did. And I meant it. I don’t think I’d ever been such a fan of someone before, not in this way, not in a literary way. I discovered that this, too, was one of the great joys of being in the writers group. That you could be a fan, an unabashed fan, of a fellow writer. That you could give them your support.

Of course there were different kinds of support. The somewhat token support you gave every person in the group when they read something. That was just manners. But I’m talking about the surge of admiration and possibility you felt from time to time about someone, about something someone read. Then you wanted to carry them forth on your shoulders, and show them to the world and say, “This person is someone you should read. This person is a writer!” This sense of selflessness the group provided from time to time cleansed my soul, as if I dipped into the healing waters, and I walked away feeling renewed and liking myself, something that I too often did not.

That was how I felt about Jan. I felt she was the real thing, that she was a marvelous writer, and that she deserved to have a career doing this. I meant it when I told her that.

There was always something in her, though, that didn’t listen. You could see it in her response. We can all be shyly modest when someone praises us, but Jan’s reaction was different. In some way she was always telling you, “I don’t believe you. It’s not true.”

Then one day she stopped coming to the group. She missed one, two, then three meetings, and so one of us who knew her, called her. He reported to us, “She says she’s not coming back.”

“Why?” three or four of us said at once.

“She wouldn’t say.”

We tried to convince her to change her mind. Two or three of us even went to her apartment and literally begged her. She just shook her head. I think I even got down on my knees to implore her. She laughed.

“No, no,” she said. “You guys have been very nice, but no.”

“Why? Why won’t you come back?”

She just shook her head again. “No, no,” she said. “I can’t.”

And so we had to grant her her privacy, had to grant her what she deserved—the right to fight her own demons in the way she wished. It was clear she had paid a large price for her humor. We tried to call her once or twice after that, but she wouldn’t return our calls. So she vanished.

I thought about her for a long time afterward. From time to time, I still do.

We just don’t want some people to leave.

June 14, 2024

China in Chicago

I’m learning Chinese.

I had my first lesson last night, on the 21st floor of a downtown office building on LaSalle Street, here in Chicago.

The class was filled with people much younger than I am. Considerably younger.

The teacher’s name is Andy. He’s China-born, spent I think he said 18 years in Beijing. He’s been teaching Chinese for twenty years.

Why am I learning, trying to learn, Chinese? Well, I’m 78, soon to be 79 (July 11. Please make a contribution to the Richard Goodman Fund for Sustainable Aging), and I want to keep the brain cells alert. I love languages. Plus, I’ve always wanted to learn a non-Roman language.

Andy packed a lot on the 2 1/4 hours of the class. Here’s some of what I learned.

The Chinese language—here I am making a general pronouncement about the language after a 145-minute exposure to it—is a kind of shorthand when, grammatically speaking, you compare it to English. There are no tenses, for example. At least no past or future tenses. Just now. Chinese can speak of the past or future, but not in the way we do it in English. Oh, and there are no plurals.

I find this refreshing.

Andy imparting knowledge

Andy imparting knowledgeEach word, or character, is a single syllable. There are no multi-syllable words in Chinese. No “indefatigable” or “conclusively.” Words are combined with other words to produce multi-syllable phrases. But in Chinese, with perhaps a few exceptions, it’s one word, one syllable.

I’m fine! And how are you?

I’m fine! And how are you?Chinese more than makes up for that paring down with sounds that are complex and highly disruptive to the mouth and tongue. Andy instructed us on how to say the Chinese letters and what he calls “finals” and “phonetics.” Some of them are daunting. I have simply never placed my mouth and tongue in those positions before.

It’s sort of like taking a yoga class for the first time and being asked to place your body in certain positions it’s never been placed in before. In fact, Chinese is a kind of yoga for the mouth and tongue. As you try, it doesn’t feel like the tongue should be doing these things. The tongue asks, “What are you doing?”

Chinese, Andy informed us, is a tonal language. That is, words have tones. The pronunciation can rise, or fall, or rise and fall. For example, the word for “good,” which is hǎo (Substack makes the “ǎ” look a bit weird, for some reason), descends and rises. Thus the ˇ mark above the word to indicate the tone; it’s a kind of singing.

The textbook is free with the course!

The textbook is free with the course!I liked Andy. He was constantly joking. These were sort of Dad jokes, Chinese teaching version. My kind of humor! They were corny, sweet-intentioned and, despite their corniness, effective. That’s because we all need reassurance. At one point, he had us all speak Chinese words and phrases together. They got increasingly difficult to say.

“Great!” he said, after a group effort. We did this again and then again, ending with Wǒ hěn gāoxìng jiàndao nǐ. “I am very glad to meet you.” Difficult! I stumbled. Then Andy paused and closed his eyes.

“I close my eyes, and what do I see?” he asked.

Silence. None of us knew.

“I see a group of Chinese people saying these words!!!!”

He meant us.

All of the class—well, at least me—felt a small surge of pride at this patently false observation. It always amazes me how susceptible we are to outright flattery.

That kind thing keeps me going.

Finally, the class was over. I walked out that evening with the freshness and fullness of mind that comes with learning.

Goodnight, Andy!

Zàijiàn!

Translation: See you soon!

June 7, 2024

The terrible infant

It’s surprising to find yourself, or something you’ve written, as a source for part of a famous dead poet’s biography. Especially a famous dead poet with an exotic, volcanic life. I’m speaking of the French poet, Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891).

I wrote an essay for a magazine about Rimbaud’s time late in his short life as a coffee trader in Ethiopia, about how he got there, unlikely as that was. I was thinking about writing something else about Rimbaud recently, so I promptly went to everyone’s convenient source of choice, Wikipedia. Lo and behold, there it is, citation number 72, a reference to the article I’d written twenty-three years ago and nearly forgotten.

It made me think of how strange it is the places we end up in our lives. Here was this enfant terrible, terrible child, possessed of extraordinary poetic powers, who ended up in Harar, in what is now northern Ethiopia, having abandoned poetry forever some fifteen years earlier, counting his money, forever concerned that local merchants were cheating him out of a few pennies, or whatever currency they used.

That’s not the way it began.

Arthur Rimbaud

Arthur RimbaudHe sprang full blown as a poet from a small city in northern France, Charleville.

Sidebar: Patti Smith, an ardent lover of Rimbaud, made a pilgrimage to Charleville that she writes about in her lovely book, Just Kids. In a video, she describes, in her typical heartfelt, sweet, brilliant way, how she discovered Rimbaud as a teenager. A year ago, she had what she called “Rimbaud Month” on her Substack newsletter with more enlightening videos. I recommend watching at least some of them. No one I know of has talked or written about Rimbaud more knowledgeably and sensitively. Hers has been a genuine lifelong love affair.

Arthur Rimbaud was writing lasting poems by the age of sixteen. He was a poet whose life was like one of those Roman candles that goes astray and sweeps erratically across the sky with the possibility of crashing into a house or a person or you. Everything about his life was dramatic, self-destructive and extreme.

He wrote incendiary, sometimes gorgeous, sometimes fearlessly sexual, sometimes frustratingly complex, and, at times, incomprehensible poetry in the remarkably brief period he wrote poetry. Which is to say, from the age of sixteen to about the age of twenty. His most famous poems are “The Drunken Boat” and “A Season in Hell.” I prefer poems like his early, exquisite, “Au Cabaret-Vert,” or “The Seekers of Lice,” or his bold depiction of early sexuality, “Memories of the Simple-Minded Old Man.”

Nothing had ever been seen like this in French poetry before, even from Baudelaire. Suddenly, Rimbaud stopped writing altogether. No one knows why. The rest of his life, he was a wanderer. He went in search of something he could never find, because it wasn’t there. He looked for it in Paris, in Indonesia, in London, in Cyprus, in Yemen. And, finally, in Ethiopia.

One of his last efforts was “Illuminations,” forty-odd prose poems it seems he wrote mostly when he was in England. Some people claim they understand them. (Patti Smith delightfully advises not to worry about that. Just experience them.) Read one, and see for yourself. If you comprehend it, please enlighten me.

Rimbaud by Picasso

Rimbaud by PicassoSome artists love Rimbaud because his chaotic, fiery life gives them validation for their own self-generated chaos. I’m sometimes a passenger on that ship. And Rimbaud’s life was as chaotic as any self-destructive American artist’s has been, if not more so. Typical is the affair he had with the (married) poet Paul Verlaine that ended with Verlaine, in a rage, shooting Rimbaud in the wrist.

As Allen Ginsberg said, “Rimbaud seems to be a complete turn-on catalyst to every poet in small town isolated, or big megapolis, staring at the city lights over the roof.” What that means to me is: don’t let those small-town minds stop you from becoming the comet that you are. So you destroy a few things, or lives, along the way. You’re an artist. Yes, an artist! A pass for crashing through life! But, really, Rimbaud harmed himself more than anyone else. Verlaine, after all, was responsible for his own life and marriage.

Rimbaud in Ethiopia, self-portrait

Rimbaud in Ethiopia, self-portraitThe last years of his life Rimbaud spent exporting coffee from Ethiopia—an astonishingly able linguist, he learned the two languages spoken there, Amharic and Harari, quickly—and smuggling guns. All he cared about was money. He took up photography. In those later years, someone realized who he was (Rimbaud had become famous in Paris without knowing it) and asked him about his poetry. “Disgusting!” Rimbaud replied. He had left that person behind long ago and, in the words of a biographer, had become “somebody else.”

One of his last letters, written to his sister from a hospital in Marseille where he was soon to die at the age of thirty-seven, says, “Our life is a misery, an endless misery. Why do we exist?”

May 31, 2024

Furnishing our Chicago apartment

We moved to Chicago a few weeks ago. We lucked into a fantastic apartment. It’s furnished, but sparsely. So we—I mean my wife, Gaywynn—set out to acquire items that we’ll need for our six-month stay. That started with a chest of drawers and a few tables.

Gaywynn hit Facebook Marketplace running. Soon enough, she’d found two tables and a chest of drawers from three different sellers all at highly-reasonable prices. She closed the deals, one by one.

Then it was up to me to fetch each piece of furniture with our car. This I did, driving to a different part of the city for each one.

All three pieces were sold by young couples in their twenties. All three couples were moving to bigger apartments, hence the selling. Each apartment I went to was in a state of high disarray of moving. All three had the male help me haul the furniture down the inevitable narrow, angular staircase. All three couples were cheery even in the face of the daunting task of moving. All three were moving to places not far from the apartments they were leaving. All three couples seemed happy.

How to define “happy”? I define it as young, healthy, bright-natured, in love, starting their young lives together.

The kind of piece and price I’m talking about.

The kind of piece and price I’m talking about.Many of us were that young couple once. All energy and optimism. A couple ready to take on the world. Barring unforeseen tragedy or ill health, they’re fine with not having a lot of money—all the apartments I visited were not plush, just young couple apartments.

When you’re young and in love you don’t need a lot of money to savor life. You want enough to pay the bills, but if you can do that, you’re free to be happy. By your own resources. You can make dinners for your friends, go to concerts in the park, ride your bikes, shop at farmer’s markets, spend time at local coffee shops and talk for hours, buy slices of pizza, walk your dog together on a new morning. Did you do that, or some version of that? Were you distraught at not having a ton of money? What was there to be distraught about?

Just $50. Notice that the cat is not included.

Just $50. Notice that the cat is not included.I didn’t get to know these young couples. Our meetings were brief. They ended when we put the tables or the chest of drawers in the back of my car. I wish them all well. But I don’t think they need my good wishes. They’re young and in love and are starting another part of their lives in a new place where they will have adventures they deserve to have, the kind you have when you’re two people who see the world as all possibility.

Gaywynn informed me yesterday that we need a rug. Soon enough, she’ll find one, and I’ll go fetch it. If things go according to plan, I’ll meet another young couple, happy together, about to move, their apartment in disarray. I’ll bask in that happiness, long after we haul the rug down the narrow stairs and put it in the back of my car, and I drive, somewhat reluctantly, away.

May 24, 2024

Phil Deaver

A little over six years ago, Phil Deaver died. He was 72. I think of him often, still. When I do, I summon up one of the sweetest men I have even known, full of good intentions and humor.

He was a great friend, loyal and caring. I can’t see and talk with the man again; but my memory can summon the times we spent together, the things he said and how he said them, and I am grateful for that. Good friends can leave their earthly selves, but their spirit stays with us and nurtures us, often in unexpected bursts, like sunshine.

Phil was a writer, first and last.

He was a complex man, and he wore his worries and insecurities on his sleeve. I remember him at Spalding University, in Louisville, where we both taught writing, how nervous he was among people there, how insecure, wanting to be with people he knew and trusted. He would insist on eating with just three or four people and no one else. You couldn’t help but love him and feel protective of him, he was so human.

Some of the writers who were our colleagues at Spalding were cliquish and condescending, and Phil was sensitive to any sense of judgment, imagined or real. Those writers, breezily haughty, probably do not know who they are, arrogance being the blinder it is, but I do. Fiction was not their genre, I can tell you that. They excluded an open heart, a lover of fiction and a man who had earned every accolade and advancement by pure passion and determination. Their loss.

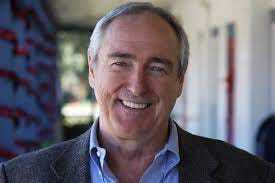

Phil

PhilPhil’s father and grandfather were killed in an automobile accident when he was 18, and that changed him forever and haunted him forever. He told me the story of that day many times, with a matter-of-fact solemnity to it, and I often felt I was there with him when he returned home that day to hear the news from his sister. This was the defining moment of his life, and it never was far from his mind or heart. He worshiped his father, who was a doctor in a small town in Illinois.

Phil was raised Catholic, and I don’t think he ever left his faith, despite what he might have claimed. It was deeply there. He had a sense of Catholic guilt about him. He told me that after his father died a group of Catholic elders from his town took him on a silent retreat. It meant a great deal to him.

He had a distinct way of talking, a Midwestern drawl with a slow cadence often leading to a bright punctuation of emphasis. I can still hear his voice in my mind’s ear. He was rooted in the Midwest.

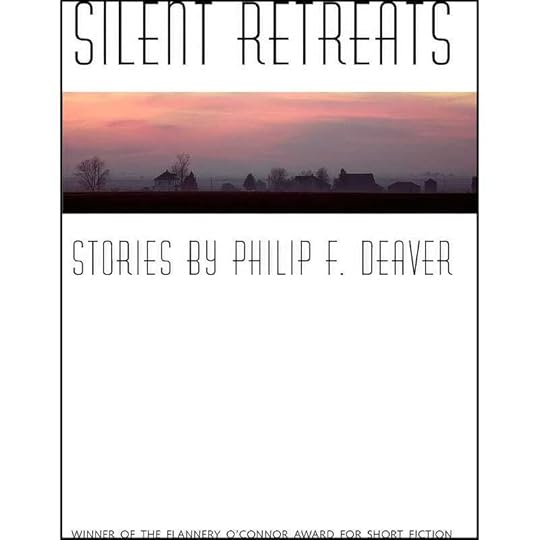

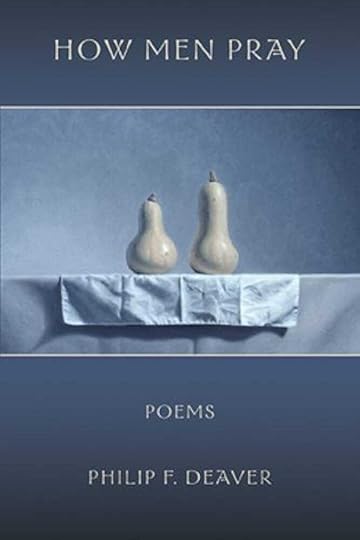

Fiction was everything to him, a religion. He worshipped great fiction writers, especially living ones. Ann Beattie was a good friend. He loved Robert Stone and Richard Ford. He was a fiction writer to his very core. His first book, Silent Retreats, a book of short stories, won the prestigious Flannery O’Connor Award in 1988. (All underlined titles have links to the works themselves.) In all his writing, Phil shows a deep love and affection for his characters. That’s not always the case with writers.

He published a book of poems, How Men Pray. I always thought he was a better poet than he thought he was or wanted people to think he was. I liked his poetry very much, and I remember how proud he was when Garrison Keillor chose his poems—on four occasions—to read on “The Writer’s Almanac.” Try his poem, “Illinois,” read by Keillor on June 29, 2014.

Phil also edited an anthology about baseball, Scoring from Second: Writers on Baseball. He was a serious fan of the game, among the sort who drive to spring training camps to see games.

I visited him twice in Florida before he became ill. I loved being at his home. We would sit and talk about books and writers and fathers and fatherhood and anything else that came to mind for hours. And watch baseball. He was a delight to be with.

He arranged a reading for me at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, where he taught and also at a local bookstore. The bookstore reading was lightly attended, and he was mortified. It didn’t bother me that much, having read at quite a few lightly-attended events in my time, but I know how he must have felt. I’ve arranged readings that were sparsely attended. You feel like you’ve let the author down. He hadn’t, of course. Part of the game.

Phil helped other writers, too. He did everything he could through Rollins to aid writers he admired or who he felt were deserving. I remember he brought in a young writer from New Orleans, who had been his student at Spalding, so she could meet with one of her literary heroes, Jamaica Kincaid.

This to me is what separates many writers from others. Those who, like Phil, use whatever influence and funds they have, not to mention encouragement, to help emerging writers flourish and those who claim they will help, and don’t. When Phil pledged his help, he kept that pledge. His students loved him. He was always enthusiastic about my work, in more ways than one, and that meant everything to me.

Phil (r) and me

Phil (r) and meHe and I used to play a ridiculous sort of game where we posed as 1950’s TV cowboy heroes. I was the Cisco Kid, and he was Lash LaRue. Which became simply, Cisco and Lash. We’d begin our letters to each other “Dear Lash” or “Dear Cisco.” It meant something to us—that 1950s TV culture that helped raise us in a dull dry era. It was some of the little romance America had back then. We still had the Wild West. We were intrigued by Lash. He used a bullwhip to subdue the bad guys. Think about it.

When I heard from Susan Lilley, his wife at the time, that Phil had suffered a brain disorder, and that, as she put it, the old Phil was slipping away, I wanted to visit him before he slipped away altogether.

So, I went to Florida in the spring of 2016 to see him for a few days. It was a sad trip. Part of him was indeed gone, and I think that may be one of the saddest things that can happen to someone we love, to have their corporal selves there, right before us, unchanged, but to have the self, or much of the self, missing. It didn’t make sense to me—there we were in his house where we had once laughed and bantered for hours—and I kept looking for Phil, the man who I loved and admired so much and who was a wonderful friend, to appear. But he was not to be found.

He was haunted by his Flannery O’Connor Award, weighed down by the burden of promise that honor bestowed on him and not producing another work of fiction. So, when he published a new book of short stories, Forty Martyrs, in 2016, a fine book, just a month or so before I visited him, he and all his friends and admirers were relieved and happy. His friend Ann Beattie loved the stories. Phil showed me a letter from her praising the book unreservedly, and he was hugely proud of that praise, which was so clearly sincere, as he should have been. I have an autographed copy. The dedication to his book reads,

In memory of my father,

Philip F. Deaver, M.D.

1920-1964

I’m writing about Phil, now, six years after his death, because in doing so, I focus him clearly and bask in his sweetness. I am better for that. For another reason, as well. When we no longer talk about someone, when we no longer conjure their laughter, the way they walked, spoke their words, the way they drove a car, sat and read a book, argued with us, laughed and talked about the things they loved—then we are co-conspirators in their vanishing.

May 17, 2024

Chicago!

We arrived yesterday evening at around 6:30, in the rain, our car packed to the brim, and over, with our dog and cat and a five-month stay ahead of us.

We had encountered Chicago rush hour traffic.

Found our apartment. Not really knowing where we are.

Unpacked, hauled suitcases and bags up three flights.

Ate something. Spent.

Bed.

Wife couldn’t sleep.

Restless pets, dog wandering about the house like a sleepless college student before an exam.

Cat meowing for God knows what reason.

Car alarm goes off at 5:30 am.

Ours?

Yes.

Downstairs to discover front driver’s door partially opened.

What? How? No damage. Fluke.

Made coffee. Everything’s good after strong, black coffee.

The morning, after a nighttime arrival, is always revealing.

I look around. The apartment we’re staying in, courtesy of a friend, is light-filled. Airy.

Our dog, Manon, observes Chicago from the deck of our new apartment.

Our dog, Manon, observes Chicago from the deck of our new apartment.Down the stairs. I step outside.

Look around. Yes, it’s true.

We’re here.

Chicago.