Richard Goodman's Blog, page 11

November 23, 2023

Thankful

It’s Sunday afternoon. A cool, sunny November day in Louisiana. Gaywynn, my wife, and I are here in our small house, which is in the country. It’s an old house, once moved, with a tin roof that needs replacing and a lot of other things that need repairing as well. Don’t get me started, as the comedian says. “It has character,” as my mother would say. Maybe too much.

I’m feeling a bit under the weather. Nothing too serious but just a bit blah. Gaywynn is cleaning her closet, something that she is happy doing. She’s got jazz playing on the radio. Right this moment, I hear, “Begin the Beguine.” I think it might be the Artie Shaw version. It makes me feel good.

I sit and read my book in the back room for a while, a thriller that entertains me greatly. I am in awe of the good thriller writers who can keep you riveted and turning the pages. Any writer would be. Or should be. What higher praise is there? “I couldn’t stop turning the pages.”

I put down the book and walk out to the kitchen. Gaywynn comes sailing in, carrying something. She smiles the biggest, most winning smile at me. It lifts my heart. It’s for me, a beautiful private gift given wholeheartedly, with love.

I don’t need anything more to be thankful for. This is all I need. This is enough.

November 16, 2023

The first couch

My first therapist was Dr. Glenn Galloway. I was a freshman at the University of Michigan, and I was a mess. Dr. Galloway’s office was in downtown Ann Arbor on the second or third floor of an old office building. I remember there was the local headquarters of the John Birch Society down the hall. I was with Dr. Galloway for about four years until he left Ann Arbor.

I came to him in the nick of time. When we started talking—or, rather, when I did—I couldn’t believe how much goo of pain was inside me. It just kept coming and coming, from some kind of inexhaustible emotional pump, all of it strange and newly-revealed, all of it I’d kept private and secluded for years and years. All my secrets and shame, all my murderous thoughts, all my unspeakable sexual desires. Un-bottled-up.

None of these I’d ever expressed to anyone before. I was re-creating trauma—is there a word for “trauma” that hasn’t become neutered?—with the original cast, at least conjured by my sobbing memory. There it was, gushing out of me like emotional projectile vomiting. This Dr. Galloway never blinked an eye.

Well, metaphorically, since I couldn’t see him. I was on the couch. What a classic position! It’s become a cartoon cliché now, the patient on the couch, and the doctor with a pad—Dr. Galloway did take notes—in anxious acceptance. It feels strange to lie, or lay, on an analyst’s couch for the first time, or even for the second and third time. I felt naked, literally. I think sometimes I might have even folded my hands across my clothed crotch reflexively. I wanted to make my body smaller. Throw me a blanket! I wanted to say. Can I wear dark glasses?

What shame and secrets? What unspeakable sexual desires?

You may ask. And I’ll tell you—if you reveal yours to me.

Still there?

I believe I came to see him three times a week. Back then—back then, I was drowning. I can hear his voice. Soft, soothing, probing. Nothing seemed to faze him. Nothing was astonishing.

He wouldn’t tell me anything about himself. Was he married?

“Hmm, why do you ask?”

“Just curious!”

“What makes you curious?”

Maddening, but, those were the rules. He never broke them, though I tried hard and cleverly.

“How long have you been married?”

“Clever.”

How many buckets of tears did I accumulate? Lots of leaks in that room. (Which was soundproof, by the way. Had two doors.) Anyone who has left their therapist’s office after weeping uncontrollably knows what it’s like to try to instantly become a normal person, especially when there’s someone in the waiting room. Hurry by.

He wasn’t perfect. He fell asleep once while I was in the middle of my relating some agony. I started hearing sleeping noises. Not snoring but, you know, that deep breathing of sleep.

“Hey!” I said. “You’re asleep!”

He woke up. Made me feel a tad less interesting, at least for a while.

He was an interpreter of dreams. That came with the package. You can unlock these Hieronymus Bosch films in my head? These sweat- and screaming-inducing nightmares? He did. At least, his take made sense to me. They weren’t just blood-soaked glyphs! They were telling me something. They became useful.

“This clearly means that…”

“This clearly means that…”I told him everything. This was before I started lying to my therapists. And withholding. I was too scared and desperate to hide anything. All the mess came out. When people talk about therapy, they often describe it as work. “I did the work,” they say. “I’m better at relationships now. But I did the work. I put in the hours.”

If you’re drowning, and you don’t want to drown, you’ll put in the work, a kind of desperate clawing. I was too desperate to lie.

I kept these things inside like a hoarder, until he opened the house and started pointing, “You have to get rid of this. It’s taking up too much room.”

“I need that!”

“No you don’t. You’re fine without it. Get something beautiful instead. And useful.”

Really?

The one thing, above all, in four years, that Dr. Galloway gave me was the assurance that I wasn’t the one, the only. I wasn’t the only one who felt these so-called appalling emotions. Who wanted these heretofore unspeakable desires met. That can take years to learn, and to believe.

“You mean,” I asked, I’m sure more than once, “That stuff isn’t abnormal?”

“No.”

November 9, 2023

Poetry. What? Are you kidding?

Every so often some intellectual will go on a talk show and try to convert America to poetry. It always sounds condescending. “Look, you people in suburbia or wherever you are, even you can appreciate poetry. With my help, of course.”

Poetry is like beets. You can’t convert people to enjoying it or convince them with some florid argument.

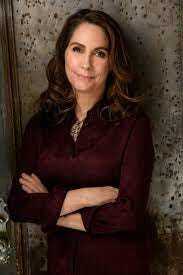

Not to mention that a lot of poetry is bullshit. That fact is not helped by critics who proclaim that bullshit to be sublime. I was so happy to see the gutsy Mary Karr call out poet John Ashbery in the The New York Times:

“His seductive voice is the most poisonous influence in American poetry. You know those page-long pieces of his in The New Yorker you can’t comprehend? Neither can anybody else. A brilliant, modest guy, immensely charming, but the most celebrated unclothed emperor in U.S. letters today — an invention of academic critics.”

Mary Karr, truth-teller

Mary Karr, truth-tellerMary, I love you! But there’s more BS where that came from. Have you ever been in the presence of someone who said their favorite poet is Mary Oliver, only to have someone else say, “Yes, well, everyone loves her. She’s a feel-good poet.” I want to knee that person in the groin. As if feeling good is antithetical to quality. Speaking of calling out, I was grateful to see Ruth Franklin’s piece in The New Yorker, “What Mary Oliver’s Critics Don’t Understand.” There’s a lot.

Mary Oliver and fan

Mary Oliver and fanI would distrust, run away from, completely reject, anyone who makes you feel small or guilty about any artist or art you love. Especially a critic.

You can’t blame people for rejecting poetry when critics make them feel inadequate by anointing false prophets who write irresponsible, unintelligible stuff. Or by heralding poets who are simply dull. But what you will find is that poetry critics are very, very reluctant to call out a living poet.

Take the critic Helen Vendler. She wrote about poetry for The New Yorker for years. I read a lot of her reviews. The only poets she disparaged were dead poets. Surely, there were living poets she thought unworthy. But to call them out would have been literary suicide—unless you have the guts and the dedication to honesty of a Mary Karr. (Ashbery was still alive when Karr’s Times’ comments appeared, by the way.) How can you choose someone to be your guide when the only color they use is rose?

Let me quote the authoritative words of the baseball-loving poet Marianne Moore. This is the beginning of her poem, “Poetry”:

“I, too, dislike it.”

Marianne Moore

Marianne MooreI like poetry. I love some of it. In fact, it has been a wonderful friend and companion my entire life. Sometimes, a lifeline. That’s just me. I’m not going to try to convert you.

Wait, let me just read you a few lines from a poem by Elizabeth Bishop…

October 31, 2023

October 27, 2023

Beauties of the common tool

Living on three acres in rural Louisiana, there is always something to tend to. Which means I use tools. These tools are about as simple as you can get: shovel, rake, ax, hammer, hoe, saw.

Simple doesn’t mean incapable, or frivolous. The opposite. These tools are works of genius. None of them have changed that much over the centuries, because their basic designs are nearly flawless. They’ve been used by people for thousands of years, and are still used, will always be used.

If they are well-made, tools have virtues that I, as a human, strive for: efficiency, steadfastness, endurance, reliability, simplicity and capability. Simplicity as exemplified in these tools is elegance. A cleanness of design, where there is nothing that doesn’t contribute to the tool’s purpose and success. A purity. What can you add to an ax? To a rake? A hoe?

People admire skillfully-made Japanese swords. They’re considered paragons. We see them in museums. Why not skillfully-made shovels, rakes and hammers in museums, the best of their kind? Their purpose is beneficial, not murderous. Their genius has contributed incalculably to humankind. Unlike those rarified swords, they’re accessible to most people. They can last a lifetime, completing untold tasks.

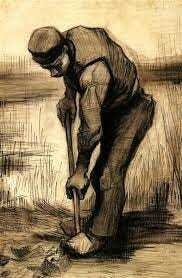

“Man Digging” by Van Gogh

“Man Digging” by Van GoghA few artists have understood their basic beauty. Walker Evans, the great photographer who collaborated with James Agee, published a piece in Fortune Magazine in 1955, “Beauties of the Common Tool.” Evans would be someone to do that. Like Van Gogh, he even turned shoes into a work of art

“Three Shovels” by Walker Evans

“Three Shovels” by Walker EvansI don’t know what tool is used by more people than any other, but my guess would be the hoe. In any case, these tools connect me to the task in the most direct way possible, short of using my own hands. They provide a sense of communion. When I dig with a shovel, I know that somewhere a farmer in Kenya is digging with a shovel or a gardener in Finland or a well-digger in New Zealand. We all use it in more or less the same way, thrusting the shovel into the ground with one foot, dislodging the earth, then lifting the earth and tossing that earth aside or into a wheelbarrow or into a hole that needs filling.

I wrote a chapter about tools in my first book, about a garden I had in the South of France. I said, “Using these tools every day was very satisfying to me. I loved taking them from their resting place in the cave, loading them in the car, hearing the sounds they made jostling together as I drove along. I loved carrying the tools from the car to the garden under my arm.”

I still feel that way.

These tools represent struggle. They represent work. And we must work. Work is what saves us. Not mindless work. Work that has a purpose. The work can be hard, certainly. We sweat. Our muscles ache. Our hands can become blistered. We want to quit. Or at least to pause. So we do, leaning on our shovel, to regain our strength. We resume, take up the tool again.

I think of Colette’s extraordinary book, Break of Day. She wrote it in the 1920s. It’s about her house and garden in the South of France and the visitors who come and go. She writes about digging in her garden:

“To lift and penetrate and tear apart the soil is a labor—a pleasure—always accompanied by an exaltation that no unprofitable exercise can ever provide.”

The work with tools is hard, it’s clean, it’s satisfying.

Shovel, hoe, rake, saw, hammer. Ready, willing and able.

October 20, 2023

A ride in Chicago with Olabode

We are in Chicago for a week. The visit is about half over. We’ve taken four Uber rides so far. These rides have been some of the highlights of the time we’ve spent here. All of the rides have been an education, a look into different worlds. All have been with drivers who were born in other countries.

One Uber ride, Saturday afternoon, was from our hotel to my wife’s children’s apartment, a 6.58 miles trip uptown that took us 21 minutes. (These facts, including our driver’s name, are from the Uber receipt.) This ride was with Olabode, who was from Nigeria. We got in his car at our hotel, and he proceeded to drive us by Lake Michigan on the way to our destination, a thrift shop my wife, Gaywynn, wanted to see.

It was a gusty, rainy day, and the lake was responding to that. It was unruly. Gaywynn and I were excited to see the waves breaking on a slant, the water gray and unfriendly. What an idea to run a major throughway along this vast lake!

Olabode was playing some music from his playlist. The language wasn’t English.

“What language is the singer using?” I asked.

I couldn’t see Olabode’s face as well as I wished, because I was in back, directly behind him.

“That is Yoruba,” Olabode said.

“Is that the language you speak?”

“Yes. Yoruba.”

Olabode gave us a rundown on the languages in Nigeria.

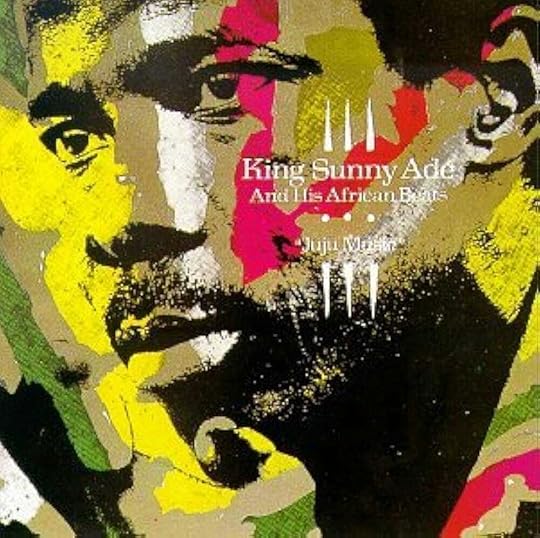

“Do you like the music of King Sunny Adé?” I asked. I knew Adé was Nigerian. I had King Sunny’s album, JuJu Music, on my iPhone. I’d listened to that album for years, even had owned the CD before I ever got a phone. Adé’s music is mellow, sweet. His voice is even-toned, appealing, soothing.

“King Sunny!” Olabode said. “Yes! Tell me a song of his, and I will play it.”

I retrieved my phone and found JuJu Music with its multi-colored cover. I blurted out the name of the album’s first song, “Ja Funmi.”

“That is a great song!” Olabode said. He scrolled through his long playlist on his phone, which was mounted on his dashboard, and found the song. Suddenly, King Sunny’s distinctive voice, like a smooth-running stream, was playing.

In an instant the power of music to unite strangers swept through the car. When I think of all the chasms there are between everyone in the world and how music can bridge them, I become optimistic—even if it was briefly.

“‘Ja Funmi’ means ‘God fight for me’ in Yoruba,” Olabode said.

“Is King Sunny still alive?” I asked.

“Oh yes. He is still very much alive.”

In the back of my mind I was thinking of a musical I’d seen on Broadway at least ten years ago. My damn aging mind couldn’t retrieve it, though. I knew, somewhere, that the singer the musical was about was Nigerian. Who was he?

We drove on. I was animated. Olabode was animated. Gawynn was animated. King Sunny Adé was singing us on our way. Olabode turned off Lake Shore Drive and headed onto Wilson Street, toward our destination.

“You know,” Olabode said, “if you like King Sunny, you must listen to Fela.”

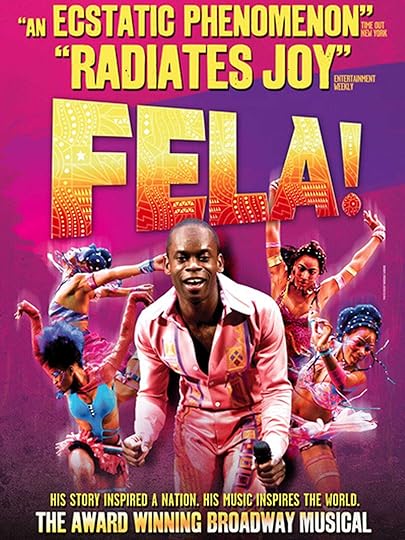

Yes!! That was it!! Fela! That was also the name of the show I’d seen on Broadway! One of the best evenings I’d ever spent at the theater. Fela appeared on Broadway from 2009-2011, so it was at least twelve years since I’d seen it.

“Wasn’t he that musician who died of AIDS?” That seemed a ridiculous detail to have remembered and to start the conversation with.

“Yes. His music is fantastic.”

“I know. I saw the Broadway show!”

Now Olabode got into it. Clearly, Fela was somebody that he revered. Fela, who died in 1997, was much more than a musician. He was a movement.

Then, bit by bit, as Olabode spoke, I recalled details of the musical, which was absolutely incredible—joyous, painful, exciting, tragic, with great music and great dancing. (If you check out the link here, make sure you look at the sample video of the show.) Olabode explained, in less than a mile, Fela’s story. Then unfolded a history of courage, nationalism, tyranny.

Fela’s full name was Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì. He was sui generis, a unique figure, an artist who disdained authority. This is from Wiki: “After early experiences abroad, he and his band Africa 70 shot to stardom in Nigeria during the1970s, during which he was an outspoken critic of Nigeria’s military juntas.”

“His mother was an activist,” Olabode said. “She fought for women’s rights in Nigeria. She was thrown out of a window by soldiers. That is how she died.”

Meanwhile, Olabode put on some of Fela’s music.

Indeed, as early as the 1940s, Fela’s mother established a women’s union and fought for women’s rights in Nigeria. I remembered her presence in the Broadway show. The actor who played Fela salutes his mother’s large photograph at the beginning of the show. Olabode told us how Fela rejected the junta’s rule and created his own compound, like a separate country.

From Wiki: “[Fela] Kuti was highly engaged in political activism in Africa from the 1970s until his death. He criticized the corruption of Nigerian government officials and the mistreatment of Nigerian citizens.” This got him into trouble more than once. He was jailed in the 80s for nearly two years. He was, throughout his life, unbowed.

“I loved that musical!” I said again.

“Yes, my wife and I saw it here!” Olabode said.

We were in the presence of not just music but courage.

We arrived at our destination.

“You have made my day!” Olabode said, with heartfelt enthusiasm.

“Ours, too!” we both said.

I felt Olabode’s generosity and enthusiasm all around us. That the common language of music had blessed us all. In twenty-one minutes, we had had a shared experience. It was genuine. It was strong. It was beautiful.

I didn’t want to leave. Of course, we did leave, though.

Ja Funmi, Olabode.

October 13, 2023

Stormy weather and trees

A week or so ago, we had a lot of wind blowing in the evening, accompanied by white jagged lightning bolts and splitting thunder.

I went outside to look. We live on three acres in rural Louisiana, and there are four towering live oak trees next to our house in addition to bushes and other trees opposite our front door. I stood and watched the wind as it swept through the trees in front and made their tops sway to its will. There was some rain, but not a lot, mostly strong wind. The sound the bushes and trees made as they brushed against one other was exciting. What did the poet Marianne Moore say about wind bending salt marsh grass? “It is a privilege to see so much confusion.” I was mesmerized, happily.

After a while, I had my fill and went back inside. The wind continued, then abated, and, finally, the thunder and lightning passed, too. The tumult was over, and a slightly disappointing ordinariness came over everything. I want to feel alive. Storms do that.

The next morning, I went outside to discover a thick, many-branched limb had been detached from one of the live oaks by the wind and had fallen. It had narrowly missed our house.

When you look at a large live oak, the limbs stretch out forever, in hills and valleys, descending their way sinuously toward the earth. They look like ballet dancers’ arms moving to music. Because they’re so graceful, you tend to forget how heavy and dense those limbs are. This snapped-off limb on the ground was very heavy indeed, and I breathed a sigh of relief that it missed our tin roof. It’s not a match for large live oak limbs. There were so many branches and limbs on this one tree, it was very hard to locate where the limb had broken off. The tree would do fine without it.

One of the live oaks near our house with Manon, our dog, patrolling.

One of the live oaks near our house with Manon, our dog, patrolling.Live oaks are synonymous with Louisiana. You see them everywhere. No other tree looks like them. They are dramatic and expansive, yet another manifestation of the originality of trees. I think of Walt Whitman’s poem, “I Saw in Louisiana A Live-Oak Growing.” He calls the tree “lusty,” but that’s like him.

I spent the greater part of the morning sawing off the branches of the limb, hauling them away, one by one, sometimes two by two, to a field nearby where they would be out of the way. It was hot. I used a medium-sized handsaw—we do not own a chainsaw—to do the work. I always find sawing wood with a handsaw more fatiguing than I expect. It makes my chest heave, my face flush. There is no doubt about your progress. But it’s work.

Work like this, small as it is, makes me feel connected to the writers who have made work in nature part of their lessons. I think of Aldo Leopold. In his stirring book, A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949, about his life on a Wisconsin farm, he describes sawing into a felled oak tree with a companion in February. He writes, “Fragrant little chips of history spewed from the saw cut, and accumulated on the snow before each kneeling sawyer. We sensed that these two piles of sawdust were something more than wood: that they were the integrated transect of a century; that our saw was biting its way, stroke by stroke, decade by decade, into the chronology of a lifetime, written in concentric annual rings of good oak.” He was sawing wood to provide heat. I was doing it to clean the yard. His writing is noble, and I feel better quoting it here. The page seems cleaner.

I sawed off all the branches and got down to the limb itself, thick as a python. It was twisted with its end displaying where it had snapped off unevenly. I sawed as much as I could from it to reduce its weight. Once again, I was amazed at how dense and heavy a tree limb can get, originating as it does from a single nut no bigger than a fingernail.

More of the live oaks, in the other direction.

More of the live oaks, in the other direction.I lifted the fat limb and placed it in our wheelbarrow. I pushed it to the field of dead limbs and branches where I deposited it with a great heave. I felt like Hercules casting this heavy thing, with a shout, onto the pile. Manual labor like this can make even small tasks seem heroic.

My job was over. I went inside. Not everything about living deep in Louisiana appeals to me, but work like this does. It’s about as clear a sense of satisfaction as you can get. It had been a good morning.

October 6, 2023

The phone book

I don’t remember the last time I saw a phone book. Much less opened one.

I’m old enough to remember small phone books. When I was a kid, in Virginia Beach, Virginia, in the 1950s, we had a phone book that was about as big as one of those explanations of insurance benefits you get these days.

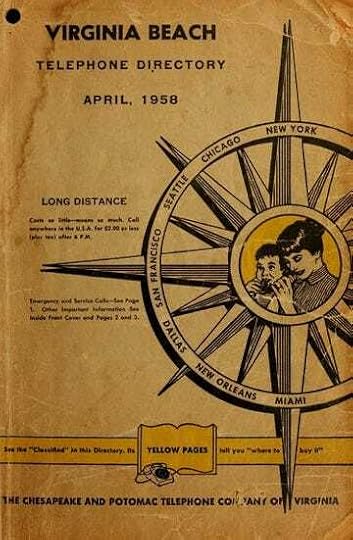

One of the phone books we had back then. Found it on the Internet.

One of the phone books we had back then. Found it on the Internet.This was also before rotary phones. There was nothing on the phone, just a blank face. You picked up the phone and a woman said to you, “Operator. Number, please.” I may be wrong—after all, this is 70 years ago—but I think our number was 3160. (It was 3163. I checked a digitalized copy of a 1953 phone book from the local Virginia Beach library.) You could ask the operator for the number of someone you didn’t know if you gave her—it was always a woman—the name and address, or even just the name. It was simple.

This is not CGI. There was no rotary.

This is not CGI. There was no rotary.Or you could look in the phone book for the number.

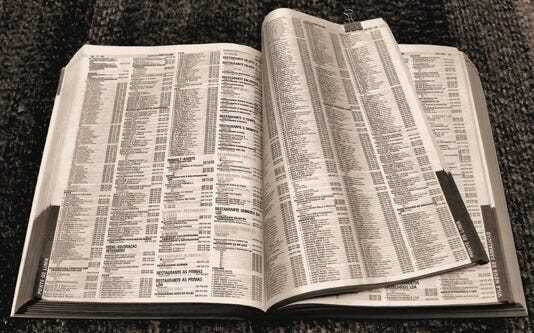

What is a phone book, some of you Generation XYZ’s may ask? It’s a book that listed, alphabetically, the names, addresses and telephone numbers of people in your area. These books started small, but as people got more telephones, they got larger.

When I moved to New York City in 1975, the phone book was as hefty as a Congressional report. The phone books were free, sent to you by the phone company annually or semi-annually. They could be so massive that sometimes guys would prove their strength by tearing one in half.

The first part of the phone book was the White Pages. That’s where you found the names and numbers of people who lived in your general area. The second part was the Yellow Pages, where businesses were listed with advertisements. The Yellow Pages became such a familiar part of American culture that the expression, “Look for it in the Yellow Pages,” became synonymous with finding a solution to almost any problem you had. It was also the source of a clever advertising slogan, “Let your fingers do the walking.”

Indeed, looking through a phone book was something you did with your fingers and hands. It carried a small sense of discovery with it.

Those big phone books were heavy. The paper was thin, but there was lots of it. In fact, they became such behemoths, the phone company began creating separate volumes for Whites Pages and Yellow Pages. It seemed to get out of control.

Actually, the phone book was handy and helpful. It had almost everyone’s name in it who had a phone. You simply opened the telephone book, searched for their name, and, usually, there it was. If there were two or more people with the same name, (“Smith, John”), then you checked the address. Ta-da! You had the number. There was something amazing having an entire city like New York in one book.

Once the cell phone arrived on the scene, it started looking around for things to replace. It set its eyes on the White Pages. Poof! They became obsolete. Then the Internet made the Yellow Pages obsolete.

I think you can still get a phone book if you want one. But who does? It was big, cumbersome, required a lot of trees, and, before you knew it, as one replaced the other, you had accumulated three or four giant tomes in the back of your closet, cursing how they took up so much space.

It doesn’t make a lot of sense, but, from time to time, I miss it.

September 29, 2023

The mystery of water

This pure, colorless liquid, this strange substance that makes things grow. That all living things must have.

Water is a great mystery.

We all know water is H2O. Two atoms of hydrogen, one of oxygen. How simple can you get? Yet no one has made water in a practical way, in great quantity. Why not? Hydrogen is readily available, and so is oxygen. Chemists, why haven’t you put two and one together? What’s the holdup?

Another mystery. Where did water come from? Scientists aren’t sure. When the earth first came into existence, it was incredibly hot. Too hot for water. So, when things cooled down, obviously there was no water. How did it get here? Scientists have theories, but no one can say, definitively, “This is how water came to be on Earth.” Today, many posit that asteroids, packed with ice, crashed into earth, thus delivering water to our planet. (Check out this piece from Carnegie Science that elaborates on that.) But there is no actual proof. You could say that water is a gift from an anonymous donor. A spectacular gift.

In a way, it would be easier to believe the Bible. In the Bible, water is just there from the start: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.”

Ta-da!

Nevertheless, as we know, water came to be. And, as we all know, there’s a lot of it. Most scientists agree that life, whether it began on land or in the sea, required water for its genesis. Space scientists—is that the term?—get all excited when they discover water on another planet. “That means there is the possibility of life!” they declare.

Let’s further the mystery: “Water is vital for all known forms of life, despite not providing food, energy or organic micronutrients.” (Source: Wiki.) What does it provide? It seems we need water for almost everything we do. “Water is fundamental to photosynthesis and respiration.” Not to mention for growing things, however that works.

Water is the ultimate shape shifter. It exists, as we know, in three forms, solid, liquid and gas. It can boil, freeze, evaporate, melt. We experience water as ice, snow, fog, rain, steam, hail, dew, frost. It makes up rivers, lakes, oceans, bays, lagoon, brooks, waterfalls. And more. It comes from the sky and from beneath the earth. What have I left out? Do you know anything on earth as mutable, each form with such distinct properties?

Like all of us, I have had exhilarating experiences with water. Some subtle, like a damp cloth being placed on my feverish brow. Some rousing, like plunging into the turquoise ocean on a hot day. Some awe-inspiring, like early-morning fog on a field. Some restful, like rain falling while I’m sitting on a porch listening. Some enlivening, like skating on a wide frozen pond in winter. Some so satisfying, like watering my garden in the early morning. Some sensual, like taking an outdoor shower in summer, water pouring over my bare body, feeling part of everything. So many more.

All of us have the picture in our minds of water being poured over hands as part of a ritual. Water, again, as we know, is sacred to many peoples.

It would take at least one post on its own—probably many more—to write about water’s religious and cultural significance. Water purifies. It brings renewal and promise. For me, water in the form of rain has always provided a sense of cleansing. The earth feels cleaner after a rain, as if it’s been given a second chance.

There will never be enough words about water.

September 22, 2023

It started with Stan and ended with Jose

My little 2010 Ford Focus was not sounding good. At low speeds, it had a distinctive wheeze that made it sound like it was out of breath. I had been told by someone who knows about these things that the spark plugs probably needed changing. So, I drove my car to Stan’s Auto Center, in Lafayette, the city near where we live in rural Louisiana. Stan’s had been recommended as trustworthy and capable.

The car would be ready the next day, the manager told me. So I called Uber to take me home. As many of you know, when you book the ride, Uber provides you with the name of the driver, the car make and the license number, along with a small photo of the driver. I was going to be picked up by Howanda, an African-American woman who would be driving a white Chevrolet Traverse.

She arrived about ten minutes later. I opened the passenger door and peeked my head in. “Ok if I sit in the front,” I asked.

“You sit wherever you like, Honey!” she said.

I installed myself in the front, and we were off.

Howanda was personable and up for conversation. She had a big smile. I could feel her energy immediately. We got around to talking about family.

“Do you have any children?” I asked.

“Four! I have three grown boys, twenty-one, twenty and nineteen. And a twelve year-old.”

“Twelve? That’s a big gap.”

“I know. My husband—my ex-husband—and I had the two boys and we wanted a girl, but the third was a boy so we said, that’s all.”

“Is the fourth one a girl?”

“No! A boy!” she laughed. “My husband and I got divorced. When people ask me who’s the father of my twelve-year-old, I say Jose Cuervo. My girlfriends and I went to Houston for a weekend, and I got a little wild. I had a lot of Jose Cuervo, and there you are.”

“Do the older boys live around here?”

“They do! They each have a wife or a girlfriend, but they love their mama.”

Her phone rang. It was on speaker. It was her mother telling her that she was going out tonight.

“You mom lives with you?”

“She does, and we like that.”

I told her that my daughter lives in New York and is a singer, writer and performer.

“It’s a difficult life,” I said. “Being an artist. But she has a lot of friends who do the same thing, so they…”

“They support each other.”

“Yes!”

“You have to surround yourself with people who support you,” Howanda said. “And you have to get rid of that one person who sows doubt, who tells you that you can’t do it. There’s always that one person trying to crush your dream. You can’t let anyone crush your dream!”

“No! You can’t.”

What a pleasure it is to talk about your children. Especially if they’re ok and healthy and trying to do what they need to do.

I became reflective, “I read somewhere recently—you know how sometimes you hear something you might have heard before, but it’s just the timing that makes you really hear it? Someone said the more you surround yourself with positive energy and people with positive energy then that will attract more people and situations with positive energy.”

“Yes!” Howanda said. “I agree with that!”

We were now off the expressway and deep in the country where I live. I realized I didn’t want this conversation to end. I told her I just got married.

“Congratulations!” she said. It was genuine. I could feel it. Anyone could.

“Thank you. I’m very happy.”

“I’m happy for you, too.”

“My wife grew up around here,” I said.

I’m still getting used to saying my wife. It feels a little odd and wonderful. It feels—how shall I put this?—grown up. I’m 78, but it still feels grown up when I say my wife.

Howanda turned right on Courville Road where we live, my wife, Gaywynn, and I.

I got out of the car.

“It was very nice talking to you,” I said. It was.

“Yes!” Howanda said.

I was reluctant to see her go. Has that ever happened to you? After such a brief encounter?

She turned her white Chevrolet Traverse around, drove to the road, turned right, and then, her car picking up speed, she was gone.