Richard Goodman's Blog, page 9

March 22, 2024

The man in white

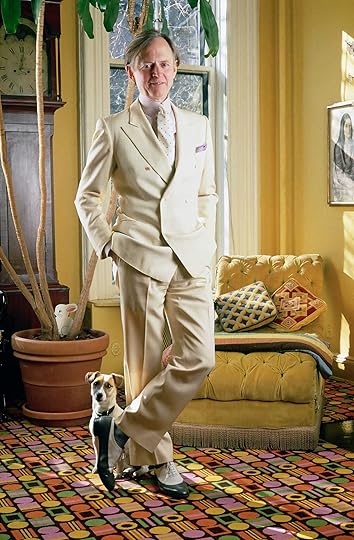

I was skimming through YouTube the other day when I spotted a video of William F. Buckley interviewing the late writer, Tom Wolfe. The interview, from 1981, was about Wolfe’s book on modern architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House. It’s a delightful fifty-six minutes. Wolfe is articulate, amusing and highly engaging. He’s not dressed in his trademark all-white three-piece suit, which is a tad disappointing, but, well, you can’t have everything. Besides, there are at least four other Buckley interviews with Wolfe discussing his other books and one, from 1999, about Wolfe’s critics, where you can see him in full bespoke regalia.

The man himself, at home

The man himself, at homeTom Wolfe changed American journalism, and, I would say, American writing. His influence was, and is, strong. I don’t think, for example, we would have had David Foster Wallace—or at least the David Foster Wallace as we know him through his arch, footnote-heavy writing—without Tom Wolfe.

Starting with The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby in 1963, Tom Wolfe continued with a stream of sharp, hugely entertaining, original books. He produced over fifteen of them. They include The Right Stuff, about the first astronauts and their model for bravery and stoicism, Chuck Yeager, and the novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities. He took on the emperor and his clothes, piercing the self-important veneer of architecture and painting, for example, with the cool expertise of a man wielding a Japanese knife of burnished steel.

Take The Painted Word, his 1979 book about modern art. He writes, at the beginning, “All these years, I, like so many others, had stood in front of a thousand, two thousand, God-knows-how-many thousand Pollocks, de Koonings, Newmans, Nolands, Rothkos, Rauchenbergs…now squinting, now popping the eye sockets open, now drawing back, now drawing closer, waiting, waiting, forever waiting for…it…for it to come into focus, namely the visual reward (for so much effort), which must be there…”

It’s refreshing to read his books. His style is like nobody else’s. He hardly ever disappoints. He always leaves you with some reward.

On top of that, as I mentioned, he was a dandy, or at least dressed like one. The Oscar Wilde of his time. Some people mocked his dress. “What’s with all this white he insists on wearing? Can’t he dress like a normal person?” I would say many people were simply jealous of his unapologetic individualism, his I'll-dress-the-way-I-want. He was a stylish writer. God forbid. He wasn’t disheveled, frumpy, slouchy, like we expect our writers to be.

He was no joke, though. He was the real thing. He added panache, daring and intelligent provocation to our society with his books and articles.

Watching the Buckley interview made me realize how much I miss his presence. Who do we have today who has replaced him? Who you can say is sui generis, authentic, as daring, penetrating, as fine a writer? Who isn’t afraid to take on any subject with as much wit and intelligence? Anyone? Please tell me that I may seek them out.

God knows, we could use that.

March 15, 2024

"I won't have what she's having."

You’ve invited someone to dinner. Say, a couple. A couple you’ve never asked to dinner before, but you’ve wanted to. You spend the afternoon or the previous evening preparing a French country dish (or whatever) for them. Say, coq au vin. You’re quite proud of your creation. It looks wonderful. It tastes wonderful. It shows imagination, effort, care and, yes, love. You’re eager to serve it to them, because, well, it’s special. It’s worth being invited to dinner for this.

They arrive. Conversation follows. Some drink. Some laughter. Then it’s time for you to serve your masterpiece. Be seated everyone! You emerge from the kitchen with the coq au vin residing in a rustic pot. It looks perfect—wine-rich with alluring scents filling the air. You place it before the couple with a flourish, certain they will be pleased.

One of them leans forward and peers at the food.

“Is that chicken?” he or she inquires.

“Yes!”

“Uh, I’m a vegetarian.”

You’re a what? You’re a vegetarian? You can’t eat this?

“Oh, don’t worry,” the vegetarian says breezily. “I’m happy with anything. Have you got something to make a salad with? Anything at all will do.”

You’re happy with anything? How about happy with this serving fork shoved up your ass until it emerges from your mouth?

This person did not think to be courteous enough to inform me of their predilection before coming to dinner so that I could plan accordingly. No, they simply arrived, assuming that I would be prepared to accommodate their saintly dietary choices.

I’ve actually had a vegetarian bring their own food to my home when they came for dinner.

It’s not that I don’t understand their choice. I actually sympathize with it. I may join them some day. Not tonight, though.

And has this happened to you? Recovering from the deflation of not being able to bask in your guests’ pleasure from your creation, you put together an uninspired, meatless dish—not expecting to have to do this, of course—and serve it to them. It looks boring. It looks unappetizing. You don’t feel right. They’re your guests!

They smile as you serve it to them.

“This is perfect,” they say. Then they proceed to pick at it desultorily. “I’m not that hungry anyway,” they say. “It’s fine. Really. Fine.”

At this point I’m going to introduce some self-proclaimed legislation. Everyone should be able to throttle at least one vegetarian in their life when this happens. Better yet, strangle them before a huge steaming plate of baby back ribs. Or in front of a row of perfectly-cooked lamb chops, dripping blood, the odor of lamb hovering in the air. Or next to a pot of country-style chuck roast, the brand of the cow still faintly visible. Or—wait! I’ve got it!—wearing a new version of the Lady Gaga meat dress.

Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha!!!

Vegetarian? I’ll. Show. You. Vegetarian.

Eat this!

Eat this!Go, save the world. Don’t eat animals. Don’t wear fur. Don’t buy leather anything. Feel good about yourself. I admire you. Honestly.

But stay the fuck away from my dinner table.

March 8, 2024

Tatted

I was getting a tattoo.

My twenty-four year-old daughter had gotten one, an owl, the symbol of Athena. She suggested I get one, too. She was visiting me in New Orleans where I was living at the time. I decided I would.

I was seventy-three.

You may wonder: why? Why did I want to get a tattoo at all?

Good question. I’m tempted to say, “Why not?” The answer is, simply, for the adventure. For the sense of solidarity with my daughter. For the—badass-ness of it. One of my friends here, a man about my age, said, when I told him that I was thinking about getting a tattoo,

“But you’ll have that on your body for the rest of your life!!!” He looked like I was about to swallow poison.

“I’m seventy-three. Rest-of-your-life is not particularly ominous at this point. Rest-of-your-life could be tomorrow.”

Anyway, it wouldn't be anything unusual in New Orleans, a heavily tatted city. (I’ve picked up some jargon along the way.) I'd chosen the likeness of a bicycle for my tattoo, an old Raleigh three-speed that I owned when I first came to New York and that I'd loved. My daughter had pulled a photo of an old Raleigh from the Internet for the tattoo artist to work from. Perfect.

But where would I have this rest-of-my-life tattoo done?

Thus followed about an hour on the Web assessing the various tattoo parlors in New Orleans, of which, as you might expect, there are quite a few. They have names like, “Hell or High Water Tattoo,” “Electric Ladyland Tattoo,” “Downtown Tattoo,” “Idle Hands Tattoo Parlor,” “Good Work Tattoo,” “Forbidden Art” and “Pigment Custom Tattooing and Piercing.”

I had to get beyond that fact that many of the artists—the men and women who would be doing the actual tattoo—looked like Queequeg. And that many of the examples of tattoos they put up on their website went from the surreal to the actually frightening. I also had to admit that some of them were beautiful—florid, accomplished tableaus, redolent with color, that carried drama and were highly expressive.

After browsing and assessing, my daughter and I decided on Pigment, a tattoo parlor on Magazine Street in uptown New Orleans, a well-heeled part of the city. I figured, with some odd logic, that if they could pay the rent in that tony location, they were probably ok.

In the words of Brigham Young, “This is the place!”

In the words of Brigham Young, “This is the place!”So, I was going to get it done.

The hour arrived, and my daughter and I drove to Pigment. On the way up, I asked her if the actual tattooing hurt. She'd gotten hers in New York where she lives.

“Not really,” she said. “I was nervous when I went in, but when he started, it just felt like he was putting pressure on my skin with the needle.”

Relieved.

We arrived at Pigment. I had just one moment of hesitation, at the door.

“Dad?” my daughter said, a slight bit of tone in her voice.

“Yes! Yes! I’m doing it.”

In we walked.

A heavily tattooed—surprise!—young man in a t-shirt was behind the counter. The place looked surprisingly orderly and, well, normal. I could see some cubicles in back where the tattoo artists were performing their magic. No screams. I explained to the man what I wanted, showed him the image of a bicycle on my daughter’s phone. He examined it.

“Yeah, we can do that. Where do you want it?”

I had decided my upper left arm.

“Ok, wait just a minute.”

He went to the back and a few minutes later a young man, slightly disheveled with clearly unwashed dark hair and, somewhat alarmingly, shaky hands, stood before me. His name was Sean. I explained what I wanted, gave him the phone with the image.

He then said something. I couldn’t make it out, because he mumbled.

“What?”

“Yeah, ok. I can do this.”

“How much will that be?”

“Uh, I can do this for one-fifty.”

That didn’t seem unreasonable. I said yes. He made a Xerox of the image on the phone and took it back to where he worked to make a sketch of it.

“Do you think he might be a heroin addict?” I asked my daughter. “I mean, look at how his hands shake. I’m a little concerned—you know, the needle. I don’t want to end up with some sort of insane zig-zag thing that looks like a toddler did it.”

“Yeah,” she said, “he is a little shaky.”

“What?”

“It’ll be fine.”

About ten minutes later, he came back with the sketch. He showed it to me. It looked all right, nothing spectacular.

“Sure. Looks good,” I said.

He nodded. Then he went back to make a stencil of the drawing from which he would make the actual tattoo. He finished and beckoned me back to his cubicle.

So it came to pass that I was lying in a semi-twisted position on the kind of cushioned couch you find in a doctor’s office, turned away from Sean so as to better afford him a good vantage to work. And then he began to tattoo me.

The first thing I realized was that it hurt. It fucking hurt. It felt like a constant stream of flu shots. Daughter! What the hell? You told me….but of course I couldn’t say this because I’d seem too much a wimp. You can’t be a wimp in a tattoo parlor. It just won’t do. That would be like saying you don’t like loud noise at a Hell’s Angel’s rally. ("Hey, you guys, be quiet!") So I just took it. And took it.

A cubicle at Pigment. (From their website.) Picture me there with Sean.

A cubicle at Pigment. (From their website.) Picture me there with Sean.I remember lying there, about twenty or thirty minutes in, tired of the puncturing needle and suddenly becoming conscious of the music that was playing all around me. Of course, it was going to be tattoo parlor music. And it was going to be loud. This is the lyric that I kept hearing:

You think your little wife will protect you, you are wrong!

You think your children will protect you, you are wrong!

You think your government will protect you, you are wrong!

It was sung with ferocious vehemence, in that monotonal, punishing pulse that punk rock does so expertly. Lying there, in pain, that music assaulting me, made me think, as I winced—what the fuck am I doing here? I found the song later. It’s titled “Heathen Child” by Grinderman. Play it when you’re getting a root canal. You’ll see what I mean.

I calmed down. I had not spoken to Sean while he was doing his work. I didn’t want to break his concentration. After one particularly painful jab, I did ask, “Has anyone stopped you in the middle of a tattoo and…just gotten up and left.”

“Hasn't happened so far,” he said in his mumbly voice. He paused. “Why—you thinking of that?”

“Me? Ha ha! No, no! Of course not! Just curious.”

Finally, after what I suppose was about an hour, Sean was done.

My daughter moved in to have a look.

“Oh, that looks great!” she said.

I got up and, slightly dazed, shirtless, looked in the mirror.

There it was, on my arm, a bicycle.

And, I have to say, it looked pretty damn cool. It really did look like my old Raleigh three-speed. The detail was amazing—all the spokes, radiating from the center of each wheel, faithfully rendered. I could even sense the heft of the bike, its presence. There it was, memorialized on my upper left arm. My daughter was beaming. I thanked Sean. Sincerely. Because he really had done a marvelous job. I was, well, in awe. He looked pleased. He took a shaky photo of his art. Then he streaked some salve on the still-aching arm and covered it with Saran Wrap. My daughter later told me that was customary.

“Just wash it with some mild soap three times a day and put some AV cream on it. After a few days, it should be fine.”

I put my shirt back on. I shook Sean’s hand. Then, with my daughter, I walked outside. I was suddenly feeling very cocky. Very baddass. Seventy-three, and look at me.

Tatted.

February 29, 2024

Paris in bad weather

The last time I was in Paris, it rained. When it didn’t rain, it threatened to. This was in October, so leaves were starting to fall from trees, and that added a sense of forlornness to my visit.

Each morning, I stepped out from my hotel on the Left Bank just off the Boulevard St. Germain into a dull gray morning. The sky hung low, the color of graphite, and it seemed just as heavy. The air was cool and dense. But I wasn’t disappointed. In fact, the opposite. After a shot of bitter espresso, I was ready to go.

That week I set myself the goal of following the Seine, walking from one end of Paris to the other. I had bad weather as my companion, and a good one it was, too. A slight rain began. I walked along the quays and over the bridges in a soft drizzle. The colossal bronze figures that hang off the side of the Pont Mirabeau were wet and streaming.

The Eiffel Tower lost its summit in the fog. The cars and autobuses made hissing noises as they flowed by on wet pavement. The Seine was flecked with pellets of rain. The dark, varnished houseboats, so long a fixture on the river, had their lights shining invitingly out of pilothouses. The facade of Notre Dame in the gloom sent a medieval shudder through me. None of this I would have seen in the sunlight.

Bad weather brings out the lyrical in Paris and in the visitor, too. It summons up feelings of regret, loss, sadness—and in the case of the first pangs of winter—intimations of mortality. The soul aches in a kind of unappeasable ecstasy of melancholy. I walked on and on in the rain, in grayness. I was seeing the city moody, poetical. So many cities look their best in the subtlety of black and white, and Paris is no exception. Gloomy weather suits it.

Great photographers like André Kertész understood how splendid Paris looks awash in gray and painted with rain. His book, J’aime Paris, shot entirely in black and white over the course of forty years, draws heavily on foul weather.

Then there is the matter of food.

There may be no Parisian experience as gratifying as walking out of the rain or cold into a welcoming, warm bistro. There is the taking off of the heavy wet coat and hat and then the sitting down to one of the meals the French seemed to have created expressly for days such as this: pot-au-feu or cassoulet or choucroute.

I remember one rainy day on this trip in particular. I walked in out of the wet. I was cold and fatigued. I sat down and ordered the house specialty, pot-au-feu.

For those unfamiliar with this dish, don’t seek enlightenment in the dictionary. It will tell you that pot-au-feu is “a dish of boiled meat and vegetables, the broth of which is usually served separately.” This sounds like British cooking, not French; the dictionary should be sued for libel.

My spirits rose as the large smoking bowl was brought to my table along with bread and wine. I let the broth rise up to my face, the concentrated beauty of France. Then I took that first large spoonful into my mouth. The savory meat and vegetables and intense broth traveled to my belly. I was restored.

I sat and ate in the bistro and watched the people hurry by outside bent against the weather. I heard the tat, tat, tat of the rain as it beat against the bistro glass. The trees on the street were skeletal and looked defenseless.

I looked around inside and saw others being braced by a meal such as mine and by the warmth of the room. The sounds of conversation and of crockery softly rattling filled the air. Efficient waiters flowed by, men with long white aprons, working elegantly.

Every so often the front door would open, and a new refugee would enter, shuddering, with umbrella and dripping coat, a dramatic reminder that outside was no cinema.

I finished my meal slowly. I had left almost all vestiges of cold and wet behind. My waiter took the plates away. Then he brought me a small, potent espresso. I lingered over it, savoring each drop. I looked outside. It would be good to stay here a bit longer. It was all comfort.

I got up to go. Paris—gloomy, darkly beautiful Paris—was waiting.

February 23, 2024

The kind of writer you want to be

Young writers are often reluctant to ask for help from established writers they know.

Unpublished and unknown, these young writers can be hesitant to ask a favor from a published writer they’ve taken a writing workshop or class with. Even if that published writer is admiring of their work.

Ask.

When your ship comes in, you can help the next boatload of young writers. That’s how you balance the ledger.

Lamentably, though, I’ve seen too many young writers who want you to buy their first small press (expensive) books, to attend the local production of their plays, to go to their poetry readings—and you do, often paying full price, even when it’s a stretch for you. Even introducing them to their future editors. And so on, all of which you do eagerly, hoping it will help.

Then when they begin to have a career, they forget those lean years when stand-up people supported them when very few others did. And they don’t help others. They seem to have conveniently lost their memory of those struggling years. And for the help others gave them.

I know such a writer in New Orleans. I know such a writer in New York. I know others elsewhere. The way things go with that sort of thing, those writers may just glide through life taking and not giving back and doing just fine. We all know justice can be fickle and arbitrary.

The writer in New Orleans—I bought his books faithfully, went to his readings and plays. Plunked down the cash. Then once I asked him to please come to a reading I was hosting for young writers in a local bar. His response? “I’m doing my laundry that night.” I still have the e-mail.

This isn’t limited to young writers. I’ve experienced the same thing with not-young writers, too.

I helped get a New York writer a job that’s taken him abroad and provided him with a steady income for years. I asked him once if he knew of a critic who might review my daughter’s work. Just wanted a name; didn’t want him to make contact. His answer? “I’m not in that world anymore.” He most certainly is, I know for a fact.

Unfortunately, the list goes on. Sometimes, it’s a surprise and a sting to get a “no” from a writer you thought would be more than happy to help. What? Really? Some memories are disarmingly short.

Don’t be one of those writers. It’s a kind of betrayal to the gods who have been so good to you. Remember how bolstering to your spirit it was to have someone on your side when you were struggling. To have someone believe in you, often when you didn’t believe in yourself.

How to be? Be like Molly Peacock. A wonderful poet, memoirist and biographer. She and I were teachers at the same university. I once asked her for a blurb—a comment that is customarily one of praise—for a book I’d written. She’s extremely busy. Nevertheless, she took the time to write one of the most movingly realized blurbs anyone has ever given me—when it meant a great deal to the book’s possible success.

Buy this book by Molly Peacock!!

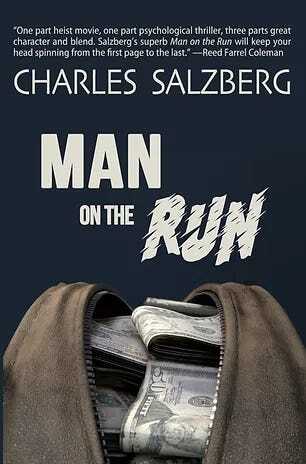

Buy this book by Molly Peacock!! Fortunately, there are others like her. Who understand what even a small gesture of recognition and praise can do for a young writer (and for an older writer) much less handing that writer the name of an agent or editor. My old friend, Charles Salzberg, in New York, is another. He’s spent a lifetime helping writers.

Buy this book by Charles Salzberg!!

Buy this book by Charles Salzberg!!I know. I was one. He helped me more than once. He’s still helping others.

That’s the kind of writer you want to be.

February 16, 2024

Parlez-vous provençal?

I lived for a year in Sanary-sur-Mer, a fishing/tourist town on the Mediterranean coast of France, about 35 miles east of Marseille. It’s a pretty town, with multi-colored fishing boats tethered to the quay and the azure Mediterranean unfolding before you. My time there did not produce the book I hoped it would, but that’s another story.

During the winter, I would look for things to do when the weather wasn’t good, and I was tired of writing. One day, I saw a notice posted that said weekly classes in Provençal were being offered for free. I wrote down the information, and when the date for the first class arrived, I went.

Sanary-sur-Mer

Sanary-sur-MerIn the 18th century, about 30% of France spoke Occitan, the umbrella language of Provençal. The language was suppressed in the early 20th century in an effort to make French the only tongue spoken throughout France. Children who spoke Provençal in class were punished. All official business had to be conducted in French. The language withered.

Provençal feels like French, Italian and Spanish were thrown into a bowl and shaken up to create a single language. For example, “How are you?” is Cossí vas? “Good afternoon” is Bonser. “The good friend” is Lou bon ami.

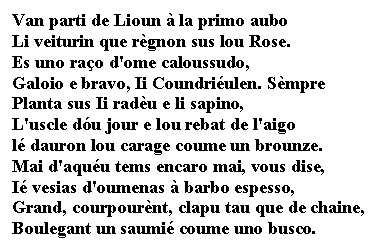

What Provençal looks like

What Provençal looks likeThe Provençal class I attended was on the second floor of a building next to a church. We met once a week. It was all women, except for me. I think there were about twelve of us, and the class was taught in French. I became their mascot, the American man who tried vainly to learn to speak Provençal. Whenever the teacher called on me to say something in Provençal, my stumbling efforts were met by surprised delight by the ladies, as if I were an infant taking his first steps. Even my smallest attempts were greeted by applause and wide eyes.

“C'est très bien, Monsieur Richard!” someone would invariably say. That’s very good, Mr. Richard!

“Regarde comment il fait ça!” Look how he does it!

“Incroyable!” Unbelievable!

When all I’d done is say “Good morning.”

“I didn’t say that very well,” I would lament in French.

“Non, Monsieur Richard, c'était excellent!”

“Oui, il a vraiment bien dit ça!” Yes, he really did say that well!

All the women would nod and smile. It’s amazing how happy I became with their flattering words, true or not.

I enjoyed very much meeting them, and I looked forward to the class and to their company. There was something warm and comforting about being in their presence. I was far from home, by myself, and I would sometimes get lonely, especially in the winter when the town was empty of tourists and a bit stark. They mothered me, the women in the class, and I realized that we all want to be mothered from time to time, no matter how old we are. These women were sweet to me, and I was grateful.

The class lasted six weeks, I think. I was sorry to see it end. It gave me a sense of purpose, and it was a kind of adventure. I didn’t learn much Provençal, though.

Once in a while, I would run into one of the women from the class in town. I was always glad to see them. If she was with a friend, she would extend a hand toward me and say to her companion, brightly,

“Il parle provençal!”

February 9, 2024

Rescued by a book

As a writer, I’ve had my share of dreams and fantasies. I’ve long since abandoned many of them—Pulitzer Prize, MacArthur Award and various other honors in a galaxy far, far away.

But then there are dreams and fantasies that may be highly unlikely, but not necessarily impossible. One of those is to tell my literary heroes (living, of course) how much their writing has meant to me. And to hear back from them.

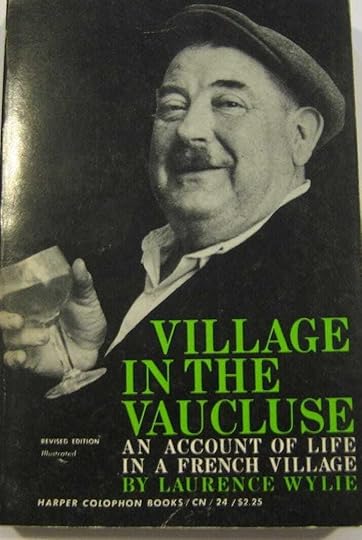

Sometimes, they can even rescue you. Which is what happened to me. It was Laurence Wylie who did the rescuing. You may not know who he is. He wrote a wonderful book called Village in the Vaucluse about living in the South of France in the early 1950s in the hill village of Roussillon.

To anyone who has not spent much time in a small village in Provence, Wylie’s Village in the Vaucluse may seem strange, or anachronistic, or both. If you have been only to cities in the South of France, the little village in the hills of Provence Wylie describes where he spent a year in 1950 with his family will probably seem something out of the 19th century to you.

He’s writing about the Roussillon of just a few years after World War II, a place with little indoor plumbing, only two phones, a once-weekly bus service to Avignon and, to be sure, no tourists to speak of. The village even had a blacksmith. It’s not the Roussillon of today, which does indeed have tourists—and gourmet restaurants, indoor plumbing, boutiques, and many more cafés than the solitary establishment Wylie used to frequent daily.

So, is this simply history, a description of a year spent in a tiny French community seventy-five years ago that, for all intents and purposes, no longer exists?

No.

If you know village life in Provence at all, you know Village in the Vaucluse is truth. Save for those few insignificant details, like indoor plumbing, Laurence Wylie’s account of living for a year in the ochre-hued Roussillon—which he dubbed Peyrane to protect the villagers’ privacy—reflects the villagers of Provence and their character as much as when it was first published so many years ago.

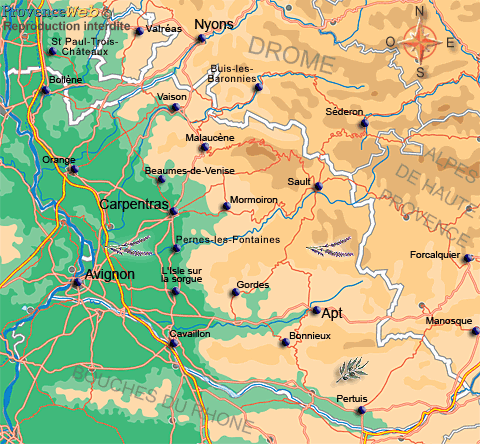

General area of the Vaucluse in France

General area of the Vaucluse in FranceAbove all, the book is a story of people’s lives. No one is a caricature in this book. Everyone is real. Everyone is memorable, too, because Wylie did his best to get inside their skin and walk in their shoes.

When you get beyond the burnished modernity of guidebook Provence, you can still find many small villages where you will encounter the direct descendants of Wylie’s Peyrane.

Yes, the houses have television now, most everyone has a car, and the kids have iPhones, but if you listen closely, you’ll hear clear echoes of Wylie’s villagers. And if you stop and live in this village or one like it for any length of time, you might swear you’ve actually stepped into Wylie’s book and that your village is his twin.

So, how did Wylie’s book rescue me?

When I was living in my village in the late 1980s, I didn’t understand why, after several months of residing there, the villagers were so aloof and unforthcoming. Why did they shun my overtures? Why did they reply to my greetings and questions with the skimpiest of answers? I was perplexed and unhappy. One day I found Village in the Vaucluse in the library of the house. My American landlord had a copy, and she had told me to read it. I’d never heard of it.

After three or four chapters, I was flung out of my doldrums. I now knew that my situation was not unique. I saw my own villagers in Wylie’s Roussillon of forty years earlier. This was the Provençal character I was dealing with, and it obviously extended far beyond my own village and beyond my own point in time. So many of the things he describes in his book mirrored my own experience.

Nothing real had changed. The longer I stayed in my little village—which is on the other side of the Rhone, by the way, some 100 miles west of Roussillon—the more reaffirmations I got from Village in the Vaucluse. What Wylie was able to capture was not just a way of living, but a character of a people. Life was much easier after I read his book.

When my own book about living in a French village was published, one of the first things I did was to send Laurence Wylie a copy in care of his publisher. Along with it, I sent a letter explaining how he had rescued me and how his book would live forever because it was true. I had no idea if he was even alive at that point. It was forty years after Village in the Vaucluse had been published, after all.

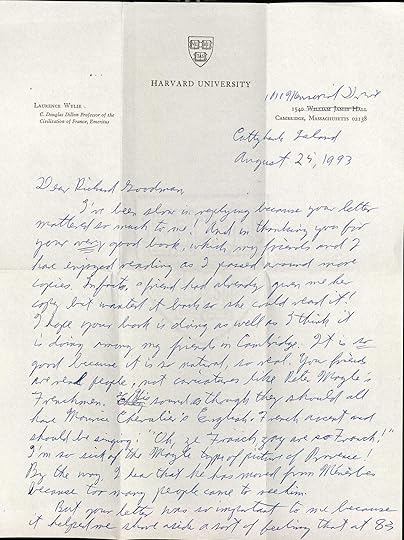

Then, one wonderful day, I received a handwritten letter from Laurence Wylie.

This, in part, is what he wrote:

“Your letter was important to me because it helped me shove aside a sort of feeling that at 83 my life is sort of dwindling without my having made a difference by living. Your letter made me feel that I had done something, so I thank you.”

That was beyond great expectations.

Two years later, he was gone.

But not his book. Not Village in the Vaucluse. It continues to have a healthy life, still in print, in its third edition, still selling. That’s great news. No book about Provence deserves it more. No author, either.

February 2, 2024

Under her spell

I remember one cold, wet January morning, I walked down Prince Street to Dean & DeLuca to meet her. Typically, she had called me a few minutes earlier, out of the blue.

“I can meet you now,” she said. That was all.

I, of course, dropped everything. The moist, frigid air penetrated my leather flying jacket, my gloves, my shoes. The light was wan. In that gray, muted light I could take in the details, the intricacies of Soho’s architecture—the rust shades of brick walls, jagged fire escapes, the cobbled streets unfolding. It was all so drinkable.

This was back when Dean & DeLuca opened its first gourmet food store on Prince. It was so new, so young, that Giorgio DeLuca himself would serve you. Small, bespectacled, with dark curly Bacchus hair and black eyes, he was nervously energetic, so determined with his young mission that he seemed hardly able to focus. Giorgio would talk to you in clipped phrases as he grabbed a croissant or pain au raisin—“Hey good to see you. Try the Romano cheese. Unbelievable.”—and shoved it into a little bag, darting around his young workers, reaching for something else.

I bounded up the two riveted iron steps, opened the door. As I walked in, the big door jingled. Just to my right were wicker quivers holding arm-long crusty baguettes, backward leaning. Directly in front of me was the counter, shaped like a tuning fork, behind which workers with optimistic faces circulated, moving in that frantic choreography of service.

The first Dean & DeLuca

The first Dean & DeLucaIn the back of the store were tables where patrons could sit and drink coffee, talk, write, or read. I stood on tiptoe, stretched my neck to look in the back to see if she was there.

She wasn’t. I ordered a café au lait and took it with me to a vacant table in back. The wood floors creaked as I made my way there. There was an old skylight above the tables, an ancient facet that poured light on you as you sat and drank or ate. There were no computers. There were no cell phones. Only pens and pencils working against paper and people reading or conversing.

I had a notebook with me. I pulled it out and imagined I was Hemingway in a Paris café. I had the pen, I had the café au lait. It was easy to convince myself that I was a writer here. I sipped the strong coffee, which was rich with breeding.

But the people around me were too interesting. The smells were too ravishing. There was too much life. Instead of writing, I looked around to see who else was there. I could do that for hours. It was the best cinema.

Then I felt something. I turned and looked up and there she was. She was standing next to the table, silent. She wore her long Salvation Army men’s coat, a fat cable knit scarf wound twice around her neck and a cable knit hat. Her long gray-brown hair streamed from under the cap and flowed onto her coat. She wore, as usual, glasses—old fashioned, the kind 1950 movie stars wore, with flares at the edges. She had put on lipstick. For me? Silly to think that! I couldn’t help it, though. My heart raced. She didn’t say hello.

“Oh, hi!” I said, a bit flustered that she hadn’t said a word.

“Hi.”

I stood up. I moved to pull out a chair for her.

“I can sit down by myself,” she said. She took the chair from me, and I was left standing there, an absurd tableau vivant, leaning toward her chair. She had limitless ways to make me look foolish, and I seemed to try on every one.

“Oh, yes, sure,” I said. I sat down.

“Look,” she said, “I don’t have much time.”

“How about some coffee?”

“I don’t drink coffee.”

“That’s right! Well, what about some tea?”

She nodded. I got up and went to the front and fetched her a pot. I put it before her. She took the tea bag out with a cautious gesture as if I’d tried to poison her.

“How’s the work going?” I asked her.

“I don’t like to talk about it while I’m doing it,” she said.

Her feral baritone! She had very little subtlety in her tone, very little modulation—a minimal range. She didn’t use the pitches, timbres or keys of her voice to help express what she was thinking or feeling. Her speech was pretty much level. She did all her expressing with her razor-blade words.

“Uh, well, ok,” I said. “What can I ask you about?”

Those wary eyes examined me through her glasses. Then she glanced at her watch.

“Don’t tell me you have to go already?” I said.

“Soon.”

Still, with all her stone cold incivility, I loved looking at her. Those lips! Those eyes, darting about the room even as I spoke to her, as if she were searching for some prey to devour. That streamy hair.

If I had had the presence to look at her closely, I would have seen someone who had no room for anyone else. But my vision was impaired.

I was under her spell, obsessed, a lap dog, a mess. I’m sure it was ludicrous to watch, laughable, embarrassing. There was no reasoning with me. I was a stranger to myself. And when a stranger inhabits you, someone who will go to any lengths for so-called love, it shakes you, like moving earth under your feet. There was no part of me that I could rely on. I doubt if I could even tell you why I was so drawn to her. I still can’t.

Do we ever have full control of ourselves?

“Well, what did you think of Danny’s piece?” I asked. At our last writers group meeting, Danny had read a piece about going home to visit his parents.

“Not much,” she said. She took two beats. “Oh, there were a few places that were all right.”

“I sort of liked it,” I said.

“We’ll,” she said evenly, “that’s the problem.”

“What? What do you mean?”

“What if I said that about your writing? That I sort of liked it.”

“Hmm.”

She reached into her old leather bag she carried and pulled out a paperback. “There’s something I want to give you.” She pushed it across the table to me. I picked it up. It was The Beet Queen by Louise Erdrich. It had obviously been read, perhaps by more than one person.

“You should read this,” she said.

“Oh great, thanks, I will.”

She got up to go. She hadn’t even taken off her coat. She’d only taken one sip of her tea.

“You’re going?” I looked up at her.

“Thanks for the tea,” she said. Then she turned and walked away.

I watched her open the store door and walk out. I wondered where she was going. To write? To meet someone else? I stayed there in Dean & DeLuca for twenty minutes or so, restoring myself with the power of the place.

I finished my coffee, got up and went outside. I drank in Prince Street. I took a deep breath.

I was miserable. I walked back toward my apartment. I waited for her call.

January 27, 2024

The best New Orleans Mardi Gras parade

Others will have their favorites, but for me it will always be Krewe du Vieux. It’s tonight. I wish I were there.

A few explanations. The people who organize and run the Mardi Gras parades are called a “krew.” Why not “crew?” I have no idea.

Most Mardi Gras parades do not roll—that’s the term used—on Mardi Gras day but in the week before, and even earlier. A few take place weeks earlier, like Chewbaccus, a Star Wars-themed parade and tons of fun, which took place on January 20, over three weeks before Mardi Gras itself, which this year is on February 13.

Most of the traditional parades have mammoth, unwieldy, tractor-pulled floats that need wide streets to accommodate them. These are the parades that are world-famous, or at least America-famous. I avoided them in the eleven years I lived in New Orleans. I could go into why, but that’s another story.

I adore Krewe de Vieux. It’s a parade on a human scale, one of the few allowed to enter the French Quarter. Its floats are not the humongous things that the mainstream parades have, but much smaller. The narrow French Quarter streets can accommodate them. Plus, the Krewe de Vieux is as much about the people who march as it is about the floats. Here’s a wandering video I took at the 2022 parade:

What is Krewe du Vieux? First, it’s a bawdy parade. The floats are out-and-out explicit. They’re usually very funny, these floats, but they’re not particularly subtle, not are they meant to be. One that comes to mind from the past depicted former (and deeply loathed by many) governor Bobby Jindal having gleeful intercourse with I think it was the Louisiana school system. In other words, Bobby screws the schools. The Bobby Jindal figure was mechanized to perform a continuous in-out motion in case you needed further explanation.

Everyone knows what they’ll see. If you take your kid to the parade—and many do—you do so with full knowledge of what to expect.

But the inventive ribaldry of the floats is not all that draws people—at least not the people I used to hang out with. It’s the pure, unadulterated joy. The exuberance. Something akin to what Rio Carnival is like, I imagine: the pounding of the drums. The gleeful faces. The costumed onlookers. It’s a festival. It’s people oriented. In a real neighborhood. The heart is happy!

This is a second video from that same parade:

My daughter came to visit one year around this time, and I took her to see Krewe du Vieux. Her eyes opened, and she literally jumped for joy.

This is New Orleans at its absolute best.

I’ll miss you tonight, Krewe du Vieux! Have fun everyone!

January 22, 2024

Last passport

I’m renewing my passport Wednesday. I have a 1pm appointment at my local post office here in rural Louisiana. I’m 78. We know passports are good for 10 years. I figure this will most likely be my last.

Yes, I’m aware that many people these days are living to be in their 90s and even to 100. But if you were a betting person, would you put your money on me getting another passport after this one? I wouldn’t.

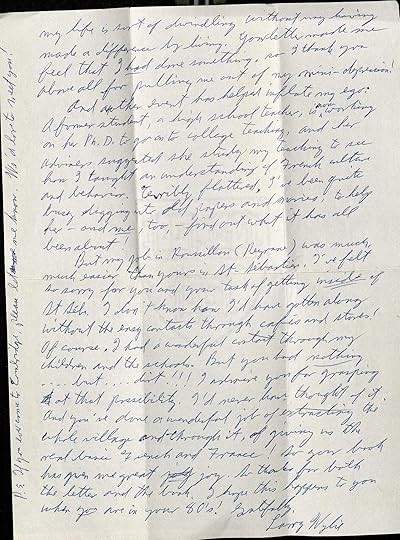

They used to let you keep them when you renewed, but in recent decades, no. So I don’t have a record of my last two or three passports, unfortunately. But I still have my passport from fifty+ years ago.

What a lift it is to look at that young man and the record of his globetrotting!

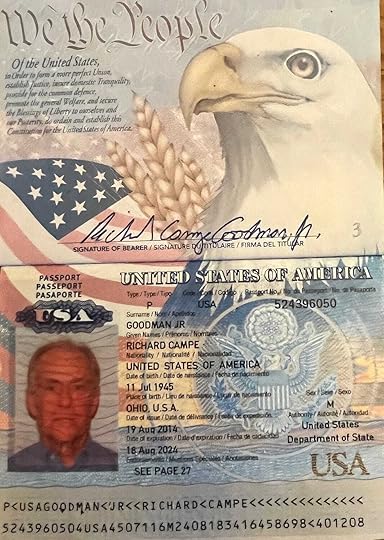

The young man, neatly dressed, slightly long hair combed, natty striped shirt and nearly tight tie, is 26.

The young man, neatly dressed, slightly long hair combed, natty striped shirt and nearly tight tie, is 26. He went to a lot of exotic places. Of course, most anyplace he went to would be exotic. He’d never been anywhere. So, Ottawa would have been exotic.

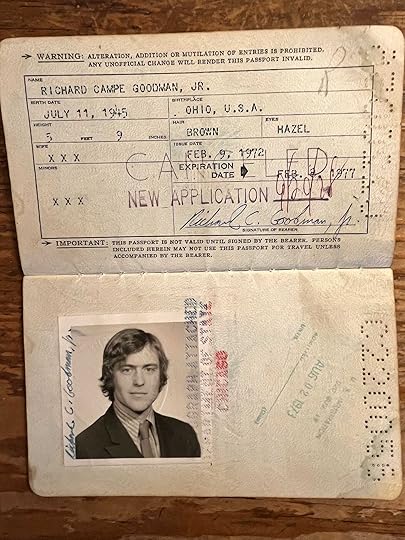

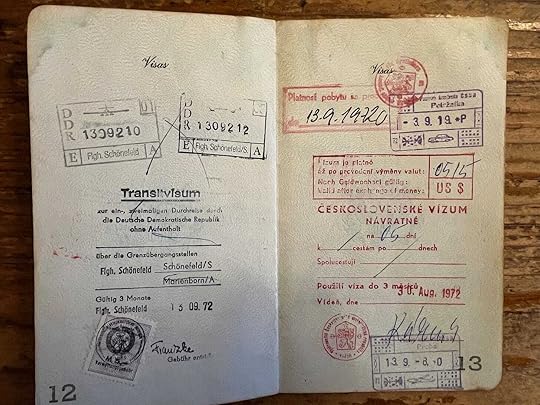

This is just the first page!

This is just the first page!But he didn’t go to Ottawa. He went to Lebanon, Syria, Greece, Italy and Yugoslavia. He went to Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary. He went to Czechoslovakia, Austria, Germany and Switzerland. To France, England and Scotland. To Holland, Denmark and Norway. And to Spain and Morocco. Each of those countries has a strong, unique taste associated with its name, like a spice.

A passport should look messy and crowded, with words you can’t read.

A passport should look messy and crowded, with words you can’t read.A passport is that most individualistic of documents. You don’t need to prove anything to obtain one, except that you are who you are. Then it becomes an official scrapbook, a record of traipsing, of whims, of careful planning and scrimping, of astonishments, even of fear and loss. Back then, when they stamped a passport, they used actual stamps that were micro-paintings. When I looked at my passport, I knew I’d been to that country.

These marks are a kind of travel tattoos.

These marks are a kind of travel tattoos.A passport in your hand says: Let’s go! Where? Well, anywhere! You and me, we can do this, we want to do this. We don’t have much money? So what? We’ll make do. We’ll sleep in campgrounds, cheap hotels, hostels. We’ll eat street food. We’ll walk, walk, walk. We’ll travel!

Some people have called me a romantic, as if it were something like having fleas. As if by being a romantic I am a sappy dreamer who wants to turn my back on reality. But some things are romantic! Traveling in faraway lands when you’re young, eating strange food, listening to unheard-of music, meeting people who speak other languages but with the same language of the heart—that is romantic! I stand by that.

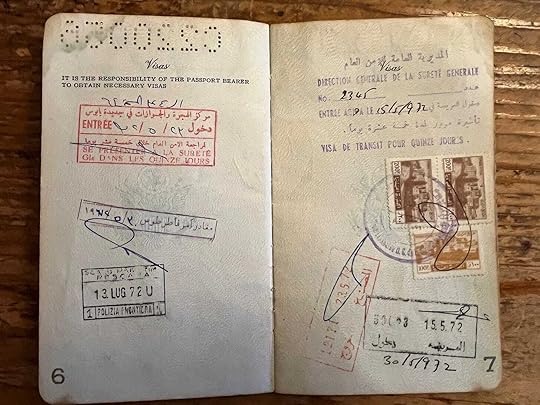

Now, here we are fifty years later.

I’m holding my most recent passport.

Look at the lines over my face, like I’m in an aquarium.

Look at the lines over my face, like I’m in an aquarium.See how complex and cautious the document has become. Look at the watermark and the hologram. (There is a barcode on the inside back cover.) It’s so protective, this passport, with all sorts of hidden alarms and shibboleths. “Be careful!” it seems to say. “Do you really have to go there?”

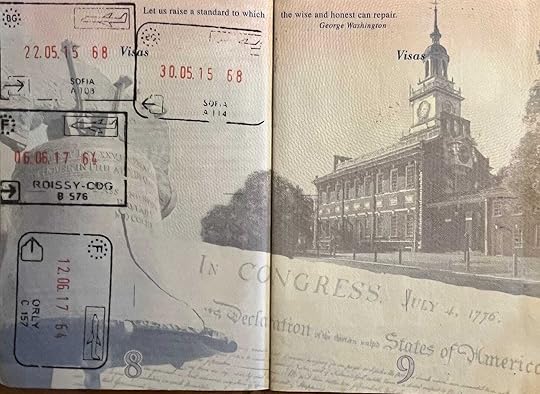

No colorful stamps on this one. Just stamped. Some nightclub stamps on your hand are more vivid.

No colorful stamps on this one. Just stamped. Some nightclub stamps on your hand are more vivid.Well, the good news is that I am getting a new passport. I’m still here. I’m still traveling. I’m still going to get up and go. In April, as a matter of fact. Paris. Can’t wait.

As for the drab passport rubber stamps, I’ll buy postcards. They’re still in color. They’ll do.