Richard Goodman's Blog, page 6

September 27, 2024

Leaving Chicago

We’ve spent the last four months living in Chicago, on North Damen Street, near Hamlin Park, on the North Side. We came from rural Louisiana for the summer to be near my wife’s children, to be in a big city and to escape the horrendous Louisiana heat. We had the good fortune to stay at a friend’s spacious, light-drenched apartment, and that was a true luxury.

We’re going back to Louisiana next Thursday. I’m not looking forward to that. But it’s time. We’ve enjoyed the hospitality of our friend, and we don’t want to overstay our welcome. We’ve had a grand summer and to complain about anything, including having to leave, would be an affront to the gods who have been so good to us.

It took me a few weeks to realize that Chicago is nothing like New York. I lived in New York for thirty-five years, and I guess I assumed Chicago would be similar to New York. Not so. In fact, it seems to me nothing like New York. It’s another species altogether, as different as Spain is from Sweden. Both big cities, yes, but hardly anything else in common. Different customs, traditions, languages, histories, auras.

Downtown Chicago from the North Side. (All photos and videos mine.)

Downtown Chicago from the North Side. (All photos and videos mine.)Four and a half months is too brief a time to write about Chicago with any confidence. I can’t say I know the city. That would take years. But I will miss many things about being here.

I will miss Lake Michigan. It’s ocean-like with ocean-like behavior and personalities. “Lake” seems too restrictive a name for it. Like an ocean, it gives a balm and inspiration with its moods, shades and changes. I often rode my bicycle down the bike path that runs adjacent to it, passing little enclaves with tethered sailboats resting together, like a Monet painting. What a tonic sailboats are! (Video below of the Lake on a blustery August day.)

Speaking of Claude Monet, I’ll miss the Art Institute of Chicago. It has some celebrated paintings—Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” Seurat’s “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” and Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” to name three. These are paintings so famous they reside inside you. Seeing them for the first time is like seeing an old friend. You want to say, “Oh, it’s you!” It has many treasures. Going to the Art Institute reminded me how much I need visual art in my life, like blood in my body.

At the Art Institute. Rodin’s “Portrait of Balzac” with Georges Seurat’s “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” to the right and Monet’s “Cliff Walk at Pourville” to the left.

At the Art Institute. Rodin’s “Portrait of Balzac” with Georges Seurat’s “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” to the right and Monet’s “Cliff Walk at Pourville” to the left.I’ll miss Montrose Street, where my wife’s daughter and son-in-law own Spoken, a delightful cafe beloved by locals and where I always felt an instant warmth when I walked inside. And Montrose Beach, where we took our dog.

I’ll miss riding my bike around the North Side, like a Magellan on two wheels, making small voyages of discovery. Claiming the urbanscapes I came upon as if I were the first person to see them. That’s what riding a bike in a new city can do. Safe? Riding a bike in a big city is never really safe, but it’s safe enough in Chicago that I never worried. I had an able bike, one that I bought used and that was refitted and given several transplants and upgrades by my wife’s son-in-law, a wizard with bicycles.

My trusted friend.

My trusted friend.I’ll miss walking our dog, Manon, around the neighborhood. I’ll miss her unwavering search for squirrels, none of which she ever caught or came near to catching. But hope always sprung eternal.

I’ll miss the trees in my neighborhood. In Louisiana, where we live, we don’t have a large variety of trees. Not like here. In one block alone, while walking our dog, I could see a botanical garden-variety of trees. Trees are the Buddhist monks of nature, with great, deep dignity and wisdom, silent and enduring and instructing.

Some trees on our block. There are more.

Some trees on our block. There are more.And I’ll miss much more.

As I say, I can’t claim to know Chicago with any authority, since all my experiences took place in the North Side of the city or downtown, except for a few visits to Chinatown on the South Side. So my knowledge is skewed and highly incomplete. But I do have great warmth, respect and gratitude for the city. Thank you, Chicago, much obliged.

September 20, 2024

The man from Aubagne

I divide French literature into two categories. Very presumptuous of me, but there you are. There are those who write from the brain, like Voltaire, Racine, Descartes, Pascal and Sartre. And those who write from the heart, like Villon, Molière, Hugo, Balzac and Zola.

Flaubert? Funny you should ask. I’d say—this may be heresy—Madame Bovary, brain. Sentimental Education, heart. His letters? All heart.

(Please don’t take me to mean that the heart writers are without brain power.)

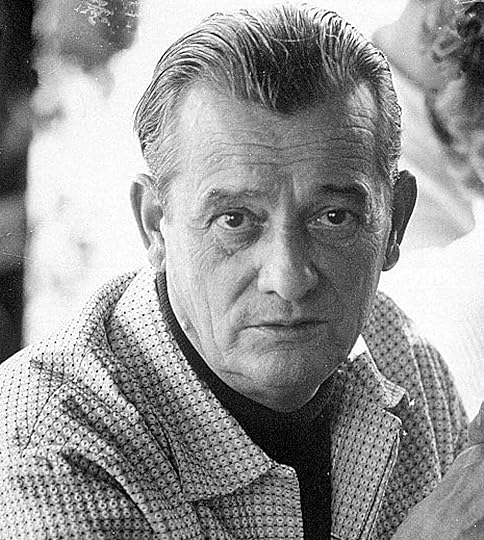

Marcel Pagnol (1895-1974) belongs resolutely in the heart category.

Marcel Pagnol

Marcel PagnolWiki says, “his work is less fashionable than it once was.” Note the word “fashionable.” Beware of that word when it is attached to a literary figure and to their work. Who the f&%$ cares if a book is fashionable or not? What is it—a coat?

Pagnol writes from his heart, and he speaks directly to yours. The heart is where truth resides, not in our brain, that great deceiver. Some of us spend our whole lives trying to avoid the influence of our brain, that conniving crafty creature that does everything it can to keep us from authenticity. “The heart knows,” as Philip Roth said.

Marcel Pagnol was born in the town of Aubagne, in the South of France, about 12 miles east of Marseille, in 1895. His father was a schoolteacher. His mother, a seamstress. He celebrated his parents tenderly and memorably in two books, My Father’s Glory and My Mother’s Castle. If you want to see what a happy childhood was like, read these books.

Pagnol had a remarkable career as a writer and filmmaker. You could say he was a regional writer, but that would be like saying Faulkner was a regional writer. He loved and cared about his characters, the men and women of Provence, and their problems, heartbreaks, needs, loves, hopes and betrayals.

In America, Pagnol is probably best known for the 1986 films, Jean de Florette and Manon des sources (Manon of the Spring), directed by Claude Berri. (Pagnol himself directed a version of Manon of the Spring, released in 1952.) These films take place in a village in Provence in the 1920s and indeed have a Faulknerian sense to them. They star Yves Montand, Gérard Depardieu and Daniel Auteuil.

I love those films, but I love the three early black-and-white films made from Pagnol’s works even more: Marius (1931), Fanny (1932) and César (1936). These films—which began their lives as plays—star the marvelous Raimu as the boisterous owner of a bar on Marseille’s Old Port and Pierre Fresnay as his son, Marius.

Raimu

RaimuEven in their grainy, early-film, melodramatic way, they stir the heart still. Marius, watching the ships in the port departing for exotic places, longs to go with them—and eventually does, leaving Fanny, a local girl he has slept with, pregnant, without him knowing.

These films are worth seeing for Raimu’s performances alone. This actor, from Toulon, who Pagnol called a genius and who Orson Welles said was “the greatest actor who ever lived,” is larger than life. He swagers and rages and is operatic in every sense, even in his speech, because his Provençal accent is the music of the region.

Have a look at this excerpt from Marius (1931), a famous scene where four friends are playing cards—César, played by Raimu, Panisse (whose name might be familiar to fans of Alice Waters and her restaurant, Chez Panisse) and two other denizens of Marseille’s Old Port. You can hear the Provençal accent in full flower, bouncing, rolling, careening like a roller coaster. Raimu is cheating, and he is over-the-top blatant about it. Panisse, furious, quits the game. After which, César declares, “If you can’t cheat among your friends, why bother to play?”

Pagnol also directed, with Raimu as the star, films made from books by Jean Giono, another Provençal writer but whose domain was haute Provence, not the coastal region of Provence. These films, most notably, La femme du boulanger (The Baker’s Wife), are delightful and moving as well.

Anything he touched is worthwhile.

When does the heart go in and out of fashion?

Richard Goodman's Newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

September 13, 2024

The open-hearted Sherwood Anderson

Garrison Keillor does not like Sherwood Anderson.

Or, rather, he doesn’t like Winesburg, Ohio, which was written by Anderson. He once said the book “is pretty dreadful, and it inspired a whole lot of bad books about sensitive adolescent males needing to flee the philistines in their hometowns.”

I’ve been entertained by Garrison and his A Prairie Home Companion many times over. I’m grateful for the wry and original shows he put on, week after week, year after year.

I think he’s wrong about that book.

Winesburg, Ohio, in case you haven’t read it, is a series of linked short stories about life in a small town in Ohio with a recurring character, a young man named George Willard, a stand-in for Anderson. It was published in 1919.

You can make a case for Garrison’s point about the book. Sometimes the writing is naive and simplistic. But his comment is a bit suspect when you consider that his show’s humor seems right out of the small town worries, insecurities and eccentricities that populate Winesburg. In his case, it’s Lake Wobegon.

Beyond that, though, Anderson’s book is true. You can experience this dramatically in one of the stories, “Adventure.” The story is about a lonely woman in this small town whose hopes are dashed. A woman whose story, save for Anderson, would be swallowed by much bigger stories that vie, always, for our attention. These are the intimate, intense tragedies in life that everyone knows about and many of us have experienced. Anderson casts his eye on them knowingly and with concern.

“Adventure” is about Alice Hindman who, at sixteen, falls in love with a boy named Ned Currie. She, “betrayed by her desire to have something beautiful come into her rather narrow life,” sleeps with Ned. She imagines they will get married and move away from Winesburg and live happily together. Ned moves to Cleveland without her, then to Chicago, promising in letters to Alice that he will send for her soon. He never does. His letters become less frequent and, eventually, stop.

Alice, however, never loses hope. She rejects all offers from other men. She holds onto the belief that Ned will send for her. As the years go on, her hope turns into delusion. Her thinking veers from reality. She no longer thinks about Ned but holds a vague notion of being rescued from her lonely life in this small town.

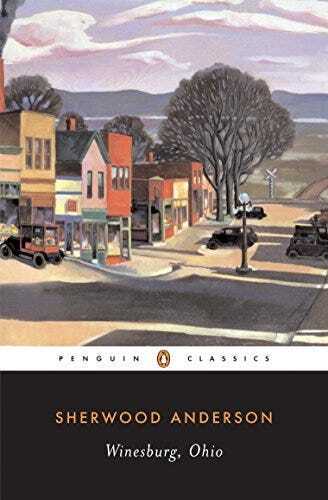

Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood AndersonOne night, during a rainstorm, she takes off all her clothes and runs naked into the street. “She thought,” Anderson writes, “that the rain would have some creative and wonderful effect on her body. Not for years had she felt so full of youth and courage. She wanted to leap and run, to cry out, to find some other lonely human and embrace him.”

Suddenly, she realizes what she’s done. Horrified, falling to the ground, not daring to stand up, she crawls back to her house.

Here, I want to ask Garrison Keillor to have a close look at this woman, at her life and what she’s come to. I want to ask him if he knows anyone like Alice who has kept the agony of being alone inside her for years and who has reached the point that Alice has reached and, in her bed at night, as Anderson describes it, “turning her face to the wall, began trying to force herself to face bravely the fact that many people must live and die alone, even in Winesburg.”

I can’t speak for you, Garrison, but I know I’ve turned my face to the wall in tears more than once.

September 6, 2024

Tidy? Me?

A while back, my landlady asked if she could come up while I was gone and clean the filters on the air conditioners. Yes, I said, sure. So, she did.

She lived behind me. A few days later, I met her at the mailboxes.

“I changed the filters,” she said.

“Thank you.”

“You keep your place very tidy,” she said.

“I do?”

“Yes. Other tenants haven’t been as tidy as you.”

I walked away, disturbed. She called me tidy. Tidy. That sent an electric current of rebellion through me. Tidy?!!?? Neat, maybe. Clean. Organized. Orderly. But TIDY?!!?? Fussy people are tidy. Finicky people. The anal-retentive.

Not only that, the word tidy evokes a man obsessed with minutiae, someone who walks around the apartment adjusting things on the table that are slightly out of line. Who blanches at a poster that is a bit askew. Who even arranges food in his refrigerator in a certain orderly fashion, the rules of which are known only to him. (You want the mayo? Second shelf, two bottles in, next to the artichoke hearts. Reason supplied upon request.)

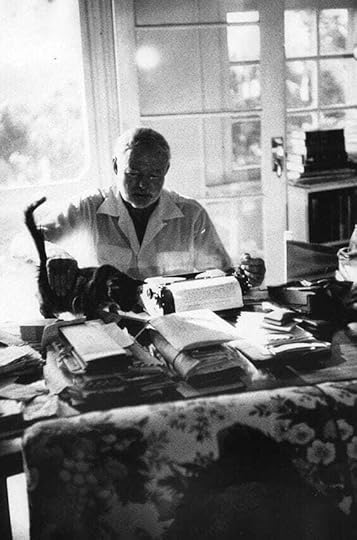

This tidiness seems to me to be the opposite of what it means to be an artist, a writer. Which I am. If I’m tidy, how can I be great?!!?? What greatness comes from tidiness? Artists are wild! Chaotic! A mess! If cleanliness is next to Godliness, what is tidiness next to? Goody-ness??? Did anyone ever call Hemingway tidy? Faulkner?

Hemingway’s desk. Very un-tidy. Of course!

Hemingway’s desk. Very un-tidy. Of course!I try. I do. I leave the bed unmade.

For a few hours.

I leave books on the floor. Clothes strewn across the couch. Dishes unwashed. Toothpaste without the top screwed on!

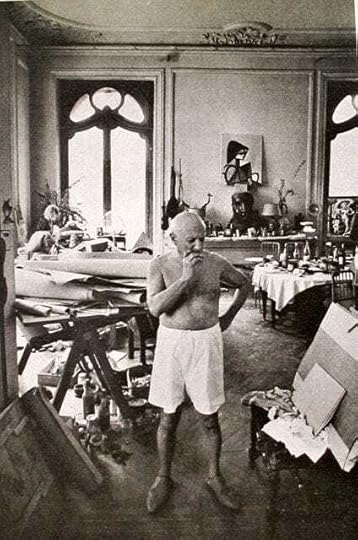

Picasso’s studio. What a mess. How did he do it?

Picasso’s studio. What a mess. How did he do it?But by some unknown force or miracle or unseen hand, all that becomes straightened out and arranged, seemingly by itself, before too long.

Once someone got into my car, a 2010 Ford Focus, and commented,

“Does anyone ride in this but you?”

“What? What do you mean?”

“It’s so neat and clean.”

“It’s not neat! Look at that stain on the seat.”

“What stain?”

“There.”

“I can’t see…”

“There, for God’s sakes!”

“I think that’s part of the fabric design.”

“No! It’s not! I distinctly remember the day I spilled a few drops of that Coke. It was a few years ago. Sunday, I think.”

“How can you remem….”

“Put on your seat belt, please.”

You decide. Judge for yourself. Come on in. Take a look at my apartment. Would you call it “tidy”?

Now that you’re here, do you think the curtains are all the same length?

August 28, 2024

Lucien

Lucien Vitiello died last February. He was 85. He passed away in his hometown of Sanary-sur-Mer in the South of France. He was a man I was lucky to know in the year I spent researching a book in that pretty town on the Mediterranean coast near Marseille.

He was a fisherman. Every morning, before dawn, he would take his small boat, Irène, five or six miles or more out on the Mediterranean in search of fish. I went with him quite a few times on that quest as an observer. I’m sure I was in the way, but he let me come again and again. When we returned, he often gave me some of his prized fish to take home. He was like that.

He didn’t know me from Adam when I first came to Sanary. When I sought out fishermen, because I wanted to learn about their ways for a book I was writing, everyone directed me to him. Lucien was the Prud’homme, or head, of the fishermen’s collective. He was highly respected, even among the fiercely independent, often disgruntled fishermen of Sanary who rarely agreed about anything. No one was ever kinder to me.

The harbor at Sanary-sur-Mer with a classic pointu in the foreground

The harbor at Sanary-sur-Mer with a classic pointu in the foregroundLucien lived in a house in the hills above Sanary with his wife, LuLu, whose child, from an earlier marriage, Lucien adopted. She was his opposite — boisterous, always in motion and sometimes a scold. She had not been treated well in her previous marriage, and she worshipped Lucien who was very good to her. He was good to everyone.

Lucien was born and raised on the small island of La Galite, which is about forty miles off the coast of Tunisia and part of that country. When he lived there, in the 1940s and 1950s, it, and mainland Tunisia, were a French protectorate. Lucien often called this small island “a paradise.” Soon after Tunisia gained its independence from France in 1956, Lucien and his family left La Galite forever and settled, finally, in Sanary-sur-Mer. He continued his life as a fisherman there.

The stories and feelings of those who were born in the French protectorates and colonies and left after independence are fraught, and that is something we rarely discussed. I was not French, had not had that experience, so felt I was better off being silent. What I saw and knew was a fine man with a generous heart.

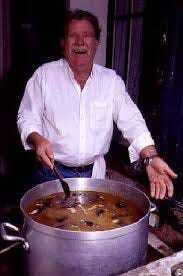

Lucien Vitiello with his bouillabaisse

Lucien Vitiello with his bouillabaisseHe would often invite me to his home in the hills for lunch on Sunday, a meal that extended well into the evening. Lucien was the cook for these meals, and a marvelous one he was. His specialty was bouillabaisse. Of course, the fish that went into the dish was what he’d caught himself.

He had a deep, growl-y voice and a short, two-beat laugh. He had a dragoon-like mustache and curly brown hair. Away from the Irène, he always wore a crisp white shirt and jeans. He was always in a good mood.

Every June, he and some of his fellow fishermen arranged what was a true extravaganza — creating the world’s largest bouillabaisse. It was made in a vast iron cauldron, cooked in the town parking lot on an enormous wood pyre and fed 1500 people. It was a sight to see.

World’s largest bouillabaisse

World’s largest bouillabaisseIt was his kindness and good humor that I remember the most. He opened his heart and home to everyone, even to men who complained about the way he led the fishermen’s collective. They were invited to his long Sunday lunches, too, and were treated to his unbounded hospitality.

At one point, he said to me “Richard, quand tu auras fini ton livre, tu m’en enverras un exemplaire?” Richard, when you’ve finished your book, will you send me a copy?

“Oui, bien sûr,” I said. Yes, of course.

But that book was never to be. The publisher didn’t want what I’d written. So, this writing, here and now, will have to do, Lucien.

I see him in my mind’s eye, seated outside on the porch of his home above Sanary. There are seven or eight of us at his table. The day is calm and sun-filled. I can see the Mediterranean from where I sit, far below. Lucien is pouring more wine into my glass, urging me to take another helping of his splendid bouillabaisse, always accompanied by his creamy, crimson rouille and crisp baguettes. Lulu is walking about, exchanging quips with some of the other fishermen gathered there. There is much laughter, good food, good talk, and the day goes on and on and on. Lucien is presiding and urging everyone not to leave, even as the sun sets and it grows dark, to stay longer and longer.

And we all do.

August 21, 2024

Attics

I climbed the stairs to the attic in our house, an airless, boards-exposed room. The room was shaped like a triangle. The air was dusty with specks, hovering. In the Virginia summer, it was stifling. I was five.

The attic was a last home for the unused. Or for things that my parents wouldn’t throw away. The contents on the floor looked like a shipwreck on the bottom of the sea. It was as if the trunks and old wicker chairs and lamps without shades and bed headboards and reproductions of paintings all had settled haphazardly by currents on the floor. There was no rhyme or reason why something was here and not there. There were large spaces of floor between clusters of things. Why?

Nothing in the attic was important enough to be part of our everyday life. For whatever reason, these things were sent to be there. Something didn’t make sense about the attic to me. The rules were different than for the other rooms in our house.

There was a bare lightbulb hanging from the ceiling with a slim chain. I could just reach the end of it. The lightbulbs downstairs were covered by shades. Here, the light was not, and that seemed strange. The slanting walls were unpainted, exposed. There was one small window that faced outdoors, allowing in a portion of light, as if it were being rationed.

Everything contributed to a sense of abandonment. Nobody cared enough about the room to paint it, to light it properly or to decorate it. Never mind that its purpose wasn’t to be lived in. There was something about the room and its objects that seemed unloved. Why else would it look that way? Why else would these objects be put here and not downstairs where we lived?

Sometimes my younger brother and sister would come up to the attic with me. We’d play with things we’d find on the floor. We’d pretend we were pirates, and everything in the attic was our treasure. The attic could be scary, too, since it had dark corners where something might be lurking. There were no grownups there to protect us.

Sometimes I went alone to the attic to hide. That was when I didn’t like my life downstairs. When there was danger. When I was hurt. When I was afraid. I found a small opening in one of the walls to a sort of secondary attic. Like an animal going into a burrow, I would secrete myself there. I didn’t want to be found.

But no one looked for me.

When I walked down the stairs and back to my normal world filled with light and familiar objects, all in the places they always were, I was relieved. However fraught, I had a place there.

In the years after, I saw many different attics in many different houses. In Maine, I stayed in a house where the attic had been made into a bedroom. The ceiling was still a downward sloping triangle, and when I stood up, I sometimes bumped my head. I opened the little window when I went to bed, and I heard the sound of foghorns and sometimes rain and thunder. The morning light streamed through the little window, and I could smell the sea and hear the birds singing.

In a summer house where my first wife and I stayed on an island in Maine, there was another attic. The wood was unfinished pine, and it was filled with old iron beds and mattresses. In the evening, our young daughter and her little friends would climb up there and laugh, away from us, and sleep on the beds we had made up for them. They had the attic all to themselves, and there was a door they could close. And they did.

We could hear their giggles way past their bedtime. This was summer in Maine, and this, we thought, is what childhood is supposed to be. So, for them, the attic, with its fragrance of pine and the scent of the sea was a happy refuge, a room of their own, and we didn’t impose our grownup rules on them. If no one slept that well, because they were having too much fun and were too excited, then the next day they could nap in hammocks on the open porch that faced the water with a light breeze and summer scents lulling them to sleep.

Not all attics, like families, are like the ones you began with. You make, or find, your own.

Richard Goodman's Newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

August 15, 2024

I won't be going to Maine this year

I go to Maine every summer, in July or August, to teach a writing workshop. I go to Rockport, which is a small, pretty town on the coast about two hours north of Portland.

[image error] Pine trees on friend’s land near Rockport, Maine. (All photos mine.)It’s beautiful where I teach, in Rockport. The school I work for pays my airfare and gives me a stipend. That’s how I can go.

This year, though, my workshop did not fill. So, I won’t be going. I’ve grown to love Maine intensely, and not having it as part of my summer makes me feel bereft.

[image error] Rockport harbor viewed from my kayak.Maine’s beauty is of a special sort. I’m speaking of summer on coastal Maine. I haven’t experienced fall, winter or spring there. Just to be clear. Nor do I know Maine’s interior that well, a different landscape entirely. So, this is an unfinished rhapsody.

Maine’s beauty, its singular personality, is difficult to put into words. I think that’s why so many people who love Maine just look at each other and nod or sigh in expressing that love.

[image error] Hill on a friend’s land near Rockport.Maine is no secret now. If it ever was. But I think it’s to the point now where you could say it’s been fully discovered. You can’t expect to come to Maine in the summer, particularly on the coast, and have it all to yourself. Perhaps once you could, but that time is gone. Still, it’s more than worth it, I assure you.

Huge Eastern white pine in Camden, Maine, on land where I stayed.

Huge Eastern white pine in Camden, Maine, on land where I stayed.A friend, a true Mainer, said to me that real Maine doesn’t begin until you get to Portland and north. She meant that the beach towns of Ogunquit and Kennebunkport, for example, located on the south coast, with their smooth sand beaches, are not, she believes, what makes Maine Maine.

You need rocks emerging from the water. You need swaths of spruce and fir. You need tall Eastern white pines. You need long, three- or four-fingered extensions of land that jut into the sea. You need hundreds of islands. You need rarified salt air. You need, of course, lobster boats and their uniquely painted buoy-marked traps. You need hills with wildflowers spread across them. You need the sense of apparent struggle to deserve this beauty.

Harbor on the island of Vinalhaven, Maine.

Harbor on the island of Vinalhaven, Maine.I’m not sure how many people have written about the light in Maine, but I want to note that. It’s rich and buttery, a painter’s dream. Uninhibited and generous. The best companion for experiencing summer’s wildflowers, sharp salt water, tall strong trees, birds, barns, narrow roads.

View of top of Beech Hill Preserve in Rockport.

View of top of Beech Hill Preserve in Rockport.I’ve written about Maine before. I’ve written about paddling a kayak around a Maine island. About the dramatic appearance of deer on the sloping lawn before me. About summoning my mother’s ghost while hanging out the wash in Maine. About fog in Maine. About turning 75 in Maine and communicating with a huge Eastern white pine about that. About how Maine stays with you when you return home.

Rockport harbor on a gray day.

Rockport harbor on a gray day.I become a different person when I come to Maine. Or, rather, I become the genuine me, the authentic me, the me that remains after all the dross and fear washes off. I discard artifice—or at least a great deal of it. I am essentialized. That is a powerful state to be in. Can a landscape make you stronger? Yes, it can.

Path on Beech Hill Preserve.

Path on Beech Hill Preserve.If we think about our fragile earth, how much peril it’s in, we might think of the places we love and speak of them. Write of them. Paint them. Sing about them. Whatever form of awareness we can muster. We have been given a gift, a magnificent gift, and we are in the midst of squandering that gift, so that those who follow us might never receive that gift. How unimaginable is that?

Lettuce for sale at Chase’s restaurant in Belfast, Maine.

Lettuce for sale at Chase’s restaurant in Belfast, Maine.We don’t know what follows when we die. But we do know what we have while we’re alive. This earth has many problems, and you don’t need me to point them out.

Sunset sky in Maine.

Sunset sky in Maine.It has many glories as well, and Maine is one of them. A place that seems to exist to celebrate being alive in just about any way you can imagine.

What is the place you love? It behooves us to sing its praises and to fight for it to last.

August 8, 2024

Arrival at Cranbrook School for Boys

September, 1959.

My mother looked at me from the driver’s seat, her hands gripping the wheel. I was looking ahead.

“I know you’re going to like it,” she said.

My stomach was knots.

She guided the vast Plymouth Fury, with its cabin cruiser dashboard, down the expressway.

“You’ll like it, Honey. It’s one of the best schools in Michigan.”

“Why can’t I stay in St. Clair?” I looked ahead. “Why can’t I?”

St. Clair was the small town in Michigan where we lived.

My mother sighed. She was forty years old, but she looked older. She had looked old since my parents had divorced two years earlier. Before, she was beautiful. That thick, lush hair, so soft to the touch, was lifeless now, nearly colorless. Her face was puffy. Where had she gone?

We drove in silence for a while.

“Oh, Honey, you were so unhappy at school there. You need a better school. You’d be bored to tears if you stayed.”

That was true. But it was more true that I didn’t want to leave another place again. Two years earlier, I was seated in an automobile in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where I had grown up, driving away from my home for good, the gravel spitting out from the tires.

We were going to Cranbrook School for Boys in Bloomfield Hills, about two hours from St. Clair. I was entering eighth grade, or Second Form as they called it after the English system. I would be a boarding student. I would live there.

Despite my protests, here we were. We turned down the dappled Lone Pine Road and into the school parking lot. I was fiercely embarrassed by my mother, by her open practical Midwestern way of confronting people. She had grown up in Dayton, Ohio. She was an Ohio girl to the cor. Later, when I was grown and talked to her as an adult about these things, I found out that she hadn’t been happy in Virginia Beach and in the South and felt alien to many of the people she met and knew there. We moved to St. Clair in Michigan, because her sister, her only sibling, lived there with her family.

Now I was horrified she would speak to someone and identify herself as my mother. Which of course she did. An older student in a coat and tie walked by us. My mother accosted him. He had an ID badge with his name printed on it and, below it, “Senior Prefect.”

“I’m Marianna Goodman,” she said to him, one hand blindly trying to find me and urge me forward, “and this—come here, Honeybunch—this is my son, Richie.”

I smiled in anger.

“He’s starting school here this year.”

“Oh really?” the boy said. “Welcome to Cranbrook."

“He’s a little anxious,” my mother said.

“Well, he doesn’t have to be,” the boy said.

“We’re from St. Clair,” my mother said. “It’s a small town. Have you ever heard of it?”

“No, Ma’am” the boy said.

“Well, if you’re ever there, you can look us up.”

The boy nodded. I was near tears.

“Now, we’re looking for...” My mother opened her purse and searched for a paper. She found it and read, “We’re looking for Marquee Hall.”

“Marquis,” the boy said.

“Marquis?” my mother said. “Okey dokey. Do you know where it is?”

“Yes, ma’am. I’ll take you there. Just follow me.”

“What about Richie’s clothes and things?”

“I can get someone to help you with that later,” he said.

We followed him to the dormitory. I had never been to the school before. My memory is that I must have filled out an application to the school from home and never actually visited the place. This was long before applying to these kinds of schools took on the formulized rigor that it has now. It was all so casual back then. So I was looking at this school in a state of stupefied wonder.

The boy led us to Marquis, then departed. We walked into the chaos of boys arriving with lockers and suitcases and parents. Each was assisted by an older boy standing there with a clipboard. I didn’t want anyone to know my mother was my mother, but she made that clear.

“I’m Richie Goodman’s mother,” she said brightly, approaching a boy not attached to an arriving family. “He’s new here. What—where....”

“Goodman, Goodman,” the boy’s eye went down the list. “Richard Goodman. Here it is. Room 316, third floor.”

“Third floor? Well, we need to have his trunk...”

“I’ll get some boys to help. Where’s your car? If you give me the keys....”

My mother explained where the car was and handed the boy her keys.

“That’s so nice of you. We’ll just go up this stairway?”

“Yes.”

“361?”

“316.”

“Okey dokey. Thank you, young man.”

We climbed the stairs three flights and turned into a hallway. It was long and shadowy. The polished waxed floor shone like dark ice. We walked down the hall carefully, past doors that were open, with families settling their sons in, past doors that were shut, until we came to 316. My mother opened the door. The room was small and simple, with a bed, desk and chair and a larger cushioned chair. There was a closet with a curtain as a door. The walls were empty. The mattress on the bed was naked. That was all.

“Well, here we are!” my mother said. “Let me sit down and rest my weary bones.”

“Don’t say weary bones, Mother.”

“Well, they are.” She sat down on the chair in front of the desk. “Well, I wonder how long it will take for that trunk to come.” My mother looked at her watch.

“You don’t have to stay,” I said.

“Oh, well, I....”

“Honest. It may be a long time before they come.”

“Well are you sure? It is a long drive home. I hate to drive in the dark.”

“No, go ahead. It’s ok.”

“Well then, all right.” She got up and gathered all her things. Then she looked at me. Tears came to her eyes. “Oh, Honeybunch, I’m going to miss you so much.”

“Awww, Mom.”

“Give me a hug. Just one.”

I hugged her half-heartedly.

It was only years later that I would begin to comprehend the burden of sadness she carried around each day. That she would return to an empty house. To an empty house in a bleak town with no husband and few friends. That she would live with the dull constant ache of my absence. That she would walk through the small house alone, not able to see me, or to speak to me, to praise or scold me, to gaze at me for a few stolen seconds. She would carry that ache with her when she went to the store and passed by cereal she didn’t need to buy anymore. She might pass by a father holding his son’s hand on the way to school. She might be doing the laundry without the chaos of my clothes. She wouldn’t say goodnight to me.

There were endless ways for her to hurt by my absence. I learned them only later, when I was a grown man, when I had married and had a daughter and then divorced and left the household as my mother had left ours. Only then, when I would wake up in the morning without my wife and daughter, alone, to an empty house, without sounds, without a family and begin to understand.

Now, though, I was young and angry and knew nothing of pity or forgiveness or compassion.

My mother started to leave, and then turned back in sadness.

“Bye bye, Honeybunch,” she said.

“Bye, Mom.”

She disappeared into the hallway, and I could hear her footsteps echo on the hard floor, one after the other.

July 31, 2024

Surfing days

The beach, an early summer morning. The three of us walked toward the ocean, surfboards under arms. The boards were heavy. These were the days of 9’6”-long boards. So long, they had to be balanced to carry.

The air was sweet with salt and morning. The sand was still damp from the night. Our feet pressed through it like it was cake icing. We—my friend, Dudley, his brother, Hartwell, and I—left lunar-like footprints as we walked. Sand crabs scurried semi-sideways, racing by on delicate points.

The sun was edging up, fiery, from the horizon before us.

We were fourteen years old, fifteen, sixteen. We’d found exactly what it was we wanted.

We walked to the edge of the water. We gazed. Were there waves? We put the boards down on the beach beside us, careful not to let any sand get on the surface we’d waxed. That would grate on our stomachs later when we paddled.

If we saw other surfers in the water, that was good. We watched them sit, in their small clutches, bobbing on their boards, or, if there were no undulations, still. Sometimes dead still. Not a good sign.

Am I lucky today?

Am I lucky today?Then Hartwell saw what he thought were waves deep in the distance He pointed, and we all became attentive, like wary animals. Hands raised above our eyes in protective shields against the sun’s light, we looked. If Hartwell was right, and there were waves, we acted.

We hoisted our boards and walked to the ocean and kept walking until we were in water, mottled and cool, first feet, then calves, then thighs, until we were deep enough that we could lay the boards down and flatten our bodies against them.

We began to paddle out. Or if we had the practice and skill, alight the boards on our knees. Then the paddling was a leaning forward and a pulling with our finger-tightened hands through the water. There might be shore break that met us, unruly. It raised the boards’ fronts upward and against our chest or knees. We paddled hard through it. We had the strength and energy.

We paddled until we were out far enough, free and clear of shore break. We situated ourselves in a little group, sitting on our boards.

Heading out

Heading outWe might say a few words to each other, or, more likely, sit silent, legs dangling in the ocean on each side of our board, breathing the briny air. The three of us waited. A set of too-small waves might pass under us, raising us up and down, a pleasant feeling, like riding a swing. The salt water dried on our shoulders in the early morning and crinkled.

An opportunity. A set of three waves was approaching, moving slowly toward us. They were always in sets of three. “Wave, wave, wave!” Hartwell called out, like he’d spotted a whale from a crow’s nest.

Dudley, Hartwell and I watched as the waves gradually rolled their way toward us. Now, it was about timing and choice. Would we try to catch the first wave of the three? The second? The third?

The waves closed in, grown larger. Our surfing instincts, honed with practice and failure, said to us that these waves were rideable.

Then the wheeling of our boards around toward the shore, poised. When the time came—and that was the issue, when was that time?—we began paddling furiously to get up enough speed to catch the wave. We wanted our momentum to match the wave’s momentum. Then, at a certain point, if we became united with the wave’s forward motion, we stood up.

Then we were riding the wave. We were surfing.

The waves always seemed bigger than they really were.

The waves always seemed bigger than they really were.We rode forward but on a slant. If the wave’s surface was sleek—glassy was the word everyone used—we felt like the first person who had ever done this, moving along the wave’s surface, going left or right depending on the wave’s direction.

If the wave was large enough—and they hardly ever got larger than three feet in Virginia Beach—then, as we rode, we might glide our fingers against its pristine surface, feeling its strong watery-ness.

All of this was happening with the sun glinting off the water’s surface and the only sound the board moving across the wave’s face and the beating of our young hearts. No adults, just Dudley, Hartwell and I catching waves in the early summer morning.

Sometimes our ride was ended by the wave’s duration and sometimes by our own mistakes. Then we fell off our board. We found ourselves submerged, the world turned upside down.

We surfaced, looked around, and located our board, floating, hopefully, nearby. We swam to it and pulled ourselves back on. We were going back out to catch another wave until there were no more waves to catch or we had to head back home to get ready for our summer jobs.

One last wave. We rode it all the way into shore, lying flat on the board, until the moment when the bottom struck the beach. We got up, picked up our board and walked with it up the beach, water dripping off the board, then over the dunes, done for the day.

All we wanted was for the day to be done and for another new morning to arrive, and we had the chance to do it all over again.

July 24, 2024

A pilgrimage to Algiers

New Orleans, 2015, a late January day.

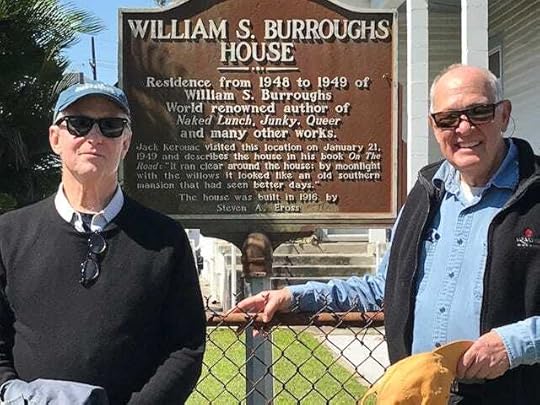

My friend, Alex Jones, and I boarded the ferry to Algiers, on the west bank of the Mississippi, just across from New Orleans, to find the house where a celebrated writer once lived. The ride across the river was short and pleasant. The sun was out. The temperature was in the low 60s. The ferry nudged into the terminal, and we disembarked. It was a good day for walking. The house, on Wagner Street, was about a mile from the terminal.

We walked past sweet-looking houses on Algiers Point, then followed the road that hugs the Mississippi and, some thirty minutes later, turned inward. We walked a few blocks more, and there it was.

It was a small shotgun with thin columns, in need of care, with a chain link fence enclosing it. The neighborhood was undistinguished, with few trees. There was a standing plaque that told the world who had once resided there.

It read, “Residence from 1948 to 1949 of William S. Burroughs. World-renowned author of Naked Lunch, Junky, Queer and many other works.”

RG, left, with his good friend, Alex Jones. Photo by Donna Parratt.

RG, left, with his good friend, Alex Jones. Photo by Donna Parratt.As we had walked toward the house, Alex and I talked about a day over forty years earlier, in the fall of 1972, when we’d both come to 8 Duke Street in London, not far from Hyde Park, to visit William Burroughs. I remember how nervous I was as I pushed the buzzer next to the name, “Burroughs.” Suddenly, I heard his voice, a low growl, for the first time, through the intercom,

“Yesssssss.”

My own voice raising an octave to a near-squeak, I replied, “It’s Richard Goodman! From America!”

There was a long pause. I looked at my friend Alex wildly. Then the voice said, “Come on up.”

We ascended the stairs to the third floor, and I knocked on the door. It opened, and there he was, William S. Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch, Junky and many other books, so-called father of the Beat Movement, mentor to Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, infamous drug addict, cult figure and a unique presence in American literature. He was smaller than I expected and wore a black turtleneck and slacks.

“Come in,” he said, waving a slow, low hand toward the inside. He turned, and we followed him into the apartment.

Now, so many years later, on that January day in 2015, we were traveling back and forth through time. We were standing before a house where Burroughs lived for a year, in 1948-49. That was sixty-five years ago. We were remembering a London visit forty-three years ago. Burroughs died in 1997. This was 2015. It was slightly disorienting.

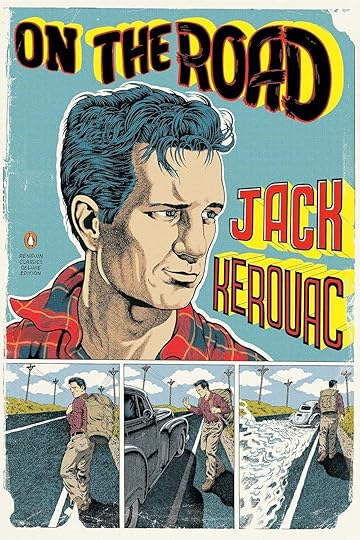

The house we were looking at is described by Jack Kerouac, who, with Neal Cassidy, visited Burroughs there on their legendary cross-country journey that would later be included in Kerouac’s classic book, On the Road, published in 1957. Kerouac and Cassidy took the same ferry we did from New Orleans to Algiers Point. In the novel, Kerouac calls Burroughs “Old Bull Lee.” (William Lee was a pseudonym Burroughs used on some of his earlier works, including Junky.) Kerouac writes,

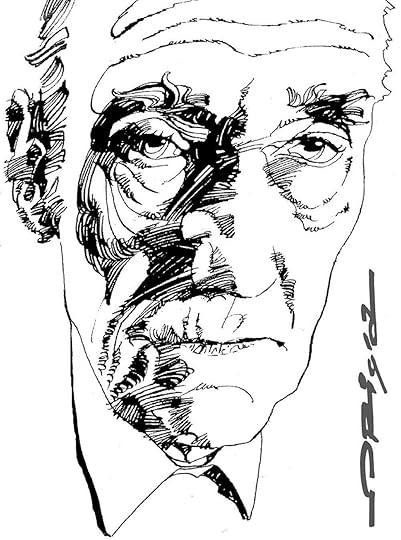

Drawing of Burroughs by Origafoundation, Creative Commons

Drawing of Burroughs by Origafoundation, Creative Commons

“We went to Old Bull Lee’s house outside town near the river levee. It was on a road that ran across a swampy field. The house was a dilapidated old heap with sagging porches running around and weeping willows in the yard; the grass was a yard high, old fences leaned, old barns collapsed. There was no one in sight. We pulled right into the yard and saw washtubs on the back porch.”

The Burroughs they visited hadn’t written Naked Lunch yet, or anything else, really. But he was a charismatic figure. Kerouac and Ginsberg met him in New York City a few years earlier, and he became a mentor to them. This is how Kerouac describes his allure in On the Road,

“It would take all night to tell about Old Bull Lee; let’s just say now, he was a teacher, and it may be said that he had every right to teach because he spent all his time learning; and the things he learned were what he considered to be and called “the facts of life,” which he learned not only out of necessity but because he wanted to. He dragged his long, thin body around the entire United States and most of Europe and North Africa in his time….He was an exterminator in Chicago, a bartender in New York, a summons-server in Newark. In Paris he sat at cafe tables, watching the sullen French faces go by. In Athens he looked up from his ouzo at what he called the ugliest people in the world. In Istanbul he threaded his way through crowds of opium addicts and rug-sellers, looking for the facts. In English hotels he read Spengler and the Marquis de Sade…. Now the final study was the drug habit. He was now in New Orleans, slipping along the streets with shady characters and haunting connection bars.

“He spent all his time talking and teaching others. Jane[his wife] sat at his feet; so did I; so did Dean [Neal Cassidy]; and so had Carlo Marx [Allen Ginsberg]. We’d all learned from him. He was a gray, nondescript-looking fellow you wouldn’t notice on the street, unless you looked closer and saw his mad, bony skull with its strange youthfulness – a Kansas minister with exotic, phenomenal fires and mysteries. He had studied medicine in Vienna; had studied anthropology, read everything; and now he was settling to his life’s work, which was the study of things themselves in the streets of life and the night.”

The household at 509 Wagner was chaotic. Burroughs, heavily addicted, lived with his wife, Joan Vollmer, also addicted, who he would later kill in Mexico. There were also two young children, one his, and the other hers from a previous relationship. The kids ran wild. There was little food in the house. Burroughs, Kerouac and Cassidy took several trips to New Orleans to scour the bars and, for Burroughs, to look for a fix.

Reading about the visit a sense of squalor runs throughout, yet Kerouac still writes about Burroughs worshipfully. It’s all surreal, flowing with the energy of youth and travel and the strong, odd, unrelenting personalities who were there in the week or so the visit lasted.

William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac

William Burroughs and Jack KerouacKerouac and crew departed after about a week, and, not long after, Burroughs went to Mexico, one step ahead of the police. One drunken night, he shot and killed his wife in what has been described as a William Tell-like stunt. He fled Mexico to avoid jail. He eventually landed in Morocco where Kerouac and Ginsberg visited him and helped him prepare the manuscript of Naked Lunch.

The house today. Photo by Kim Ranjbar.

The house today. Photo by Kim Ranjbar.How did I find myself in 1972 walking in the door of Burroughs’ London flat, a young man of twenty-seven, an aspiring writer, who like Burroughs in 1948 in Algiers, had written very little and published nothing to speak of?

I first read Naked Lunch in 1968 when I was a graduate student at Wayne State University in Detroit. I fell under its spell. I can still hear myself, laughing hard at passages in the book in my cheap student apartment on West Willis in Detroit. I was a convert. I immediately enlisted in the corps of Burroughs admirers and acolytes. After reading Naked Lunch and its predecessor, Junky, I decided I wanted to write my master’s thesis on Burroughs’ work.

When I told my advisor, he was stunned and horrified.

“You mean the William Burroughs who wrote Naked Lunch?!? The drug addict?”

Yes, that’s the one. And yes, I do.

Credit to him, my advisor. He reluctantly said yes.

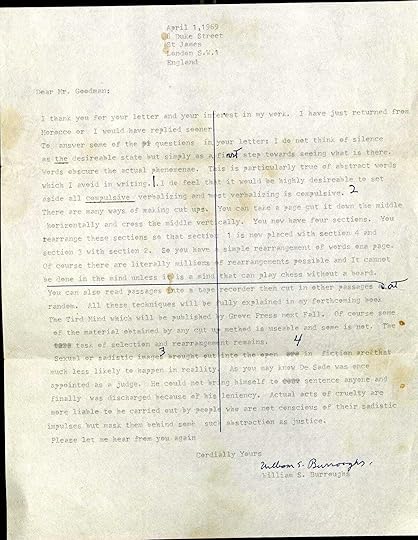

In the process of writing and researching my thesis, I decided, on a whim, to write Burroughs a letter in care of his publisher. I asked him a few simple questions about his work. I had no idea where he was or what he was doing. Three months later, to my astonishment, I received a reply. Burroughs was living in London.

“Dear Mr. Goodman,” his letter, dated April 1, 1969, began, “thank you for your letter and interest in my work. I have just returned from Morocco, or I would have replied sooner.” He answered a few of my questions. It was a short letter, but at the close he wrote, “Please let me hear from you again.” So began an irregular correspondence between us that lasted about five years.

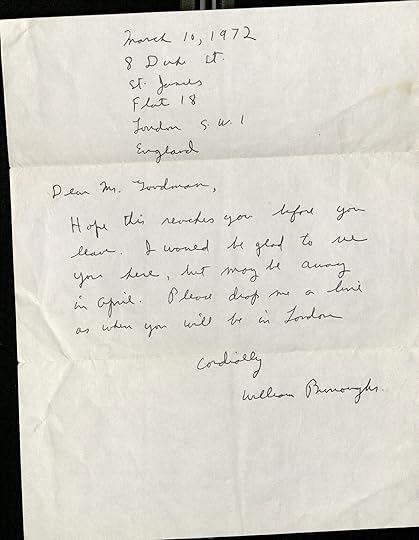

After I’d finished my thesis—and sent a copy to Burroughs—sometime in 1971, I decided to go to Europe with my friend Alex Jones. I wrote William Burroughs telling him I would be coming to London and asked if I could stop by for a visit.

He said yes.

That’s how I found myself in front of his apartment door in London that fall day. I still find that hard to believe. I wrote a piece about that visit, which lasted far into the evening, a few years later. It was my first published piece, and it was because of William Burroughs. I saw Burroughs a few times after that, in New York, where he moved to from London. We eventually lost touch, but I still have his letters and the memories of our visits, and I cherish both.

That January day in 2015, so many years later, we didn’t stay long at Burroughs’ old house in Algiers.

The thing about pilgrimages like this one is that the person who lived there is long gone, and you are really encountering ghosts. Nobody’s home, so to speak—even literally, sometimes. You walk through, or gaze at, a phantom house. The emptiness can be deafening. So it was in Algiers, that warm day. Burroughs had been dead for nearly twenty years. He hadn’t lived in Algiers in seventy years.

But I was a pilgrim. I didn’t go to Algiers expecting to actually find Burroughs. I was there to pay homage. I was a devotee. If you want to see and visit with the occupants, they are alive and well in the pages of On the Road, and they always will be.

People go on religious pilgrimages to worship at the shrines of saints and martyrs. I don’t see much difference in what I did that day. They go to make a physical journey, often following in the footsteps of a saint or hero—or in my case, a writer—to their home or final resting place.

It’s a way of acknowledging your gratitude for their gifts to you. They have inspired, delighted, astonished, uplifted and comforted you. You want to publicly acknowledge that. You’re saying, “You once lived here, perhaps in obscurity, perhaps struggling, perhaps lonely and in doubt, perhaps even badly. I am here to give thanks to you and to pay homage.”

That’s what I did that mild January day in 2015 at 509 Wagner Street. I was a pilgrim.