Richard Goodman's Blog, page 5

December 12, 2024

Old faithful

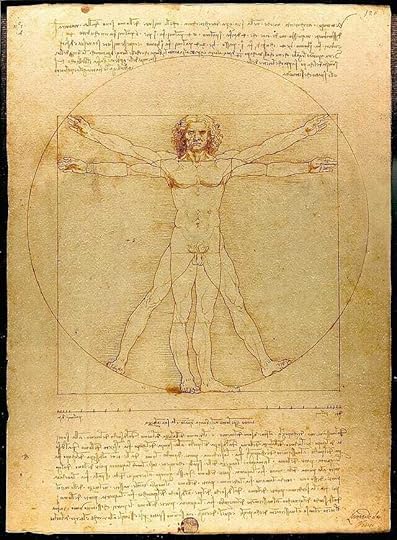

I’m in my late seventies. I like to point this out on a regular basis. This time, because I want to talk about my body, to thank it for all the long years of faithful service, for tirelessly performing day in and day out so wonderfully well. No one ever had a better companion in this life.

So, Ladies and Gentlemen, I first want to thank my brain. Thank you for letting me think. And create. And imagine. The spectacular leaps, connections, solutions you came up with—amazing! You’ve been responsible for coordinating the whole shebang, my entire form, working efficiently and well. You never let me down. Somewhere in there is memory, preserving experience on demand. My great, heartfelt gratitude.

Heart! What can I say? How unstintingly you pumped my blood to the far reaches of me, supplying me, from head to toe, with nourishment and centering me with your beat. The engine room, still going strong. Is there anything on earth that works this well, when healthy, without fail, for so long?

Thank you, lungs, for your tireless day-in-day-out bellows work. When I slept, you never did. I’m so grateful for the great swell and release of air, 24/7.

Thank you, stomach, kidneys, liver, for the impossibly complex work, the alchemy, you’ve performed for me. Cleansing, converting, filtering, regulating. I could spend days reciting your greatness.

Thank you, eyes for letting me see the world. For letting me see my daughter’s face. And for being able to weep. Thank you tongue for the letting me taste peaches. Ears for letting me hear the singing of birds. Fingers for letting me touch a woman’s hair. Nose for letting me smell an ocean breeze. For the many daily miracles I’ve experienced, I’m in your debt.

Thank you, arms for making me so versatile and for the hard work we did, lifting and pulling. Thank you, hands for letting me grasp, push, and pull. And hold a pen, move it across the page, write words. Thank you, legs for taking me near and far and for giving me so much steed-like pleasure. Thank you, skin for keeping it all together and for sweat. Thank you, lips for letting me kiss. Thank you voice for letting me speak, for letting me issue words of comfort, praise, and affection.

Thank you intestines, large and small. Your work may not be as glamorous as your colleagues, but it’s no less complex and miraculous. You represent inherently what my entire body demonstrates daily, hourly—efficiency.

I am at the podium with my extended list of thank-yous. The other parts of my body to thank are just so numerous. But I at least have to mention blood, that great mystery. And I can’t forget spine, neck, back. Back, of course! So mighty and responsible.

Hips, feet, nerves. Shoulders, bones, muscles. How much time do I have? Let me not leave out all those unheralded and unseen microbes that have, for three score and nineteen, been mixing, converting, breaking down and doing astonishing things men and women in white are still trying to figure out.

Pardon me for what I’ve left out, body. It was all so important.

You’ve been the best body any person could ever want. I know I’m fortunate. You’ve worked well for so long without a hitch. I’ve never taken that for granted. I know you’ll be getting tired soon. Parts of you will begin to break down, to give out. Of course. Then I’ll become even more aware of the essential role you played in my life. But what a ride you’ve allowed me to have. All of it, every single part of it, a gift.

December 5, 2024

Coming home

I’m a writer. That means I spend a lot of time alone. In many cases, at home. My wife, Gaywynn, has a job, and she leaves the house in the morning at 8:30 and comes home about 5. It’s just the two of us in this house.

We live out in the country, so if I don’t go to town and work in a coffee shop, it’s just me and the dog and the cat—all day. I’m by myself. After I finish writing, in late morning, I do have things I have to do. There are always things to fix in our house, which is old and keeps reminding us of that. During the day, though, I miss my wife. I’m glad she’s happy doing what she’s doing, but at times throughout the day, I miss her.

So when Gaywynn’s car pulls up the long driveway at around 5, and she gets out and comes to the door, my heart leaps up, as they say. I’m so glad to see her. She has a beautiful smile, and seeing it warms me, and everything is all right. She’s back home. We’re here together.

This makes me think of other times when women I’ve known have experienced this moment in different ways. In ways that weren’t always so bright.

I think of my mother who after she married my father moved from Ohio where she lived to Virginia where he lived. It was the late 1940s. A different world! She encountered a new and strange place. She didn’t know a soul except for my father. They had three children within eleven months—me, first, and then twins, my brother and sister.

When my father left for work in the morning, she was there by herself in the house with three young children, alone. If you’ve been in a similar situation, you know how difficult that can be. So the moment my father returned and opened the door was one that she waited for all day, a moment that could turn a stressful, exhausting day into bliss. That moment could make up for a lot.

I’m thinking of all the mothers, like mine, in the 1940s and 1950s who waited for their husbands to come home. They applied lipstick and brushed their hair, took off aprons and made themselves as beautiful as they could. They just wanted that door to open and have their man there, once again, home. Because then you had the two of you against the world. You were together.

Then my father began coming home late and later, and my mother’s wait became longer and harder to bear. She took solace in drink and then things began to get bad. I’m not trying to pin their problems on a single daily moment—who really knows what happens between two people?—but I think it’s emblematic, it dramatizes a relationship. Things dulled between them, they argued, there were tears. They divorced. Then my mother never waited for anyone to come home again.

The roles may be reversed between us, but that powerful moment is the same. That moment when each of us thinks, it was worth it, whatever mess I had to deal with today, whatever low points I had, whatever failures. Because you’re home. We’re together. I’m so happy to see you, and we can deal with whatever it is. Throw most anything at us, and we’re good for it.

You’d be so nice to come home to, Cole Porter wrote. It is, and I want to protect that.

November 28, 2024

Thankful

I’m thankful for so many things. Especially now. Especially today.

I’m thankful for my daughter. It’s a sublime gift to be the father of this brilliant, beautiful young woman. And she’s here, with me, this Thanksgiving!

I’m thankful for my good health.

I’m thankful for light; for the English language; for walking; travel; reading; Hemingway; museums; laughing; storms; for Paris; birds; learning, for my body.

For gardening; the French language; poetry; outdoor showers; Maine; Flaubert’s letters; for the moon; The Great Gatsby; Southern food/soul food; for my Smith-Corona Galaxie II manual typewriter; for cooking; my first apartment in New York on Tenth Street; music; M.F.K. Fisher; Giotto.

For van Gogh; French bookstores; the sound of rain; dogs; New York City; driving down country roads; Isak Dinesen; fall, winter, spring, summer: the ocean; opera; the light in Provence; for writing; Deborah Attoinese; the struggle to make my book, French Dirt, the best book I could write.

For salt air; Ralph Ellison; a good baguette; my sister; snow falling down; road trips; going to sleep when I’m exhausted; tea; kayaking; for Van Morrison; the Frick Museum; the Italian language; my bicycle; Michelin maps; François Truffaut; my daughter’s laugh; tall, slim pine trees; New Directions paperbacks; Tennessee Williams.

For old docks; books; going barefoot; etymology; James Baldwin; friendship; biscuits; work; identifying plants and trees; New Orleans; porches; the songs of birds; Balzac.

For Cole Porter; West Fourth Street in New York City; libraries; the smell of hay; my wife’s gorgeous smile; sweat; the Seine; Rome; my senses; the stillness of early morning; women’s breasts; Pablo Neruda’s poetry.

For overcoming fear; for deep, pristine snow; water; wood, the smell and feel of it; herons and egrets; trains; Chris Downs; a simple desk; for women’s rich, lavish hair; my brother; the rejuvenation sleep provides; Jean Rhys; coming home to someone you love; wetlands, Velázquez.

For a cast iron skillet; Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers; a good dictionary; lovemaking; Big Joe Turner; Evelyn Waugh; the Cevennes; rock ‘n’ roll; full lips; seeing my daughter born, holding her for the first time; for Joseph Conrad; Marcel Pagnol; Chester, my dog, RIP; my memory; pecan pie; Ms. Booth, Ms. Benson, Ms. Shugrue, Ms. Carley, all the teachers who were so kind to my young daughter.

For Langston Hughes; Greenwich Village; Verdi; warblers; kindness; pastrami; bookstores; belly laughs; breathing; Lucinda Williams; the smell of suntan lotion at the beach; dusk; strong coffee; Ray Charles; brilliant sunsets; Elizabeth Bishop; Central Park; Wellfleet oysters; stretching; friends’ voices; affection; holding hands with the woman I love; the release of crying; John Lennon; truth.

And, especially, this Thanksgiving, for my wife, for Gaywynn.

November 22, 2024

Snow in New York

It snowed all night. It snowed heroically, with some flakes so large they were like parachutists floating down. The snow continued hour after hour. I was in bed in my Soho loft, and I watched the snow through the windows as I finally fell asleep in that vast room.

The next morning, Saturday, it was still snowing. I was going to my mother’s apartment on the East Side later, but before I made that journey uptown, I wanted to see New York City in the snow, and there was only one place I wanted to go.

I took the shaky elevator down from my loft and walked outside. The sidewalk, and even the cobblestones in the street, were puffy white versions of themselves. This was the advantage of getting out on the street early. People never emerged that early in New York on weekends. I had this white perfection to myself, at least for a while. The snow made me a child again, full of wonder.

There are no trees in Soho, that domain in lower Manhattan that was once a manufacturing hub. No shrubbery, no plants — except on rooftops — no eye-level windowsills, no cast iron gates protecting small plots of earth — nothing to catch or hold the snow, except the street and sidewalk. Snowy perfection was transitory in Soho. That’s why when it snowed significantly, I always sought out Greenwich Village for the most stirring New York snow experience.

That early morning, I walked up to Bleecker, then turned west toward Seventh Avenue. There were only a few people trudging along in the swirl. I passed by Zito’s bakery and my mouth watered thinking of the crusty loaves they sold and how many I had bought there. I passed Ottomanelli’s butcher shop with its pig head in the window wearing a hat. I thought of the white-haired man and his four burly sons who ran that family place. There was so much to brighten your day here.

I crossed Seventh Avenue. The swirls of flakes landed on my eyelashes. They flew against my cheeks. I trudged on and arrived at my destination: West Fourth Street. When most people think of snow, they may have a Robert Frost image of easy wind and downy flakes in the dark deep woods. In my mind, I see West Fourth Street, especially the portion between Seventh Avenue and West Twelfth Street in Greenwich Village. When you walk it, you pass by century-old brownstones and cross some of the city’s prettiest streets: Bank, Charles, Perry, West 11th. It’s quiet. It’s narrow. Trees line both its sides. In the snow, it’s as gorgeous a place there is to be in New York.

I walked along, my footsteps muffled, my progress slowed, my legs breaking trail. That’s how deep the snow was. Just a few cars had gone by leaving parallel impressions in the street. I could smell the snow. As I walked, I looked into the huge brownstone windows to see life stirring inside. Some windows had curtains, some did not. Some were decorated with lights outside, blinking at me. I saw a woman indoors in her robe pass by the glass. A cat stared at me from the windowsill, its eyes following my every move. I could feel its inside warmth

I walked on. I saw enviable kitchens. I saw paintings and mirrors on the walls. I saw ceiling-high bookcases. The world of families. The brownstone life. Everything you could want: intimacy and the tensile strength of families in the heart of Greenwich Village. That was the life I wanted. It was love and comfort.

Soon, children would be emerging from these buildings, dressed snugly like little astronauts, scooping up the snow and tossing it at each other, slipping and squealing. But not yet.

The only sound was the wind. I inhaled coldness. I crossed Perry. I was tempted to turn off West Fourth and follow that street. Every street I crossed was tempting. The snow was molded on grates and on plants and on sconces to the very brim, waiting for the one flakey addition that would force it to calve. That hadn’t happened yet. Everything was soft, white perfection. I didn’t want Vermont. I didn’t want Robert Frost. He could have his dark, deep woods. I wanted West Fourth Street covered in snow. I wanted New York.

November 14, 2024

Sena Jeter Naslund

I’m writing a thank-you letter here.

You may know Sena Jeter Naslund from her books, especially Ahab’s Wife. She’s written nine. I know her in a different capacity. As the leader, guide and inspiration of the Master of Fine Arts in writing program at Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky where I taught.

I taught at Spalding, under her careful eye and guidance, for nine years, from 2003 to 2012. It’s no stretch to say that she rescued me. I was living in New York City, struggling to stay afloat. My first book had been reissued, and I got some mileage out of that, including an invitation to the South Carolina Book Festival. That’s where I met Sena. An old friend, who taught at Spalding, introduced me to her there. He had raved about Sena and the program for years.

I returned to New York and wrote Sena asking her if she would consider hiring me to teach at Spalding. It’s a low-residency program, meaning that students come to Louisville twice a year for workshops and the rest of the year send their writing to their teachers for critiquing. I sent her a copy of my book. Luckily for me, she said yes. I was thrilled. In the fall, I went to Louisville for the first time.

That’s where I got to know Sena up close and personal. To see how she ran the MFA program, but, more important, to experience an atmosphere for writing and learning she had created unlike I'd ever experienced before or since.

Her presence—when I was there, at least, because she has since retired, is very much with us, and continues to write—was felt in every corner, every room, in every decision, in every goal of the program. She handpicked each teacher, most of whom she knew personally and many of whom she had taught at an MFA program in Vermont.

She told me once that she could never hire anyone whose work she didn’t like. Every teacher that I knew spoke of her as if their friendship was a kind of betrothal. These relationships were deeply personal and proprietary. I always got the feeling that teachers felt that Sena was theirs alone. Their bonds were fast.

What she did was to create an atmosphere of non-competitiveness and unity of purpose I have never seen in any of the colleges and universities where I’ve taught writing. She’d encountered the opposite in her own teaching career and was determined that would never be the way in her program. It wasn’t. There was a sanctity that she created by her force of will and, yes, aura.

“Welcome home!” she said, beginning each residency. And another perennial opening, “Your competition isn’t in this room.” Meaning the auditorium where we all gathered. “It’s in the library.” You can get an idea of her Alabama-born, bell-like voice here in several interviews I’ve never heard a voice as commanding with less aggression.

For two weeks each year, in the fall and spring, students and teachers would live and work in a foreign country where everyone spoke the same language. Foreign, because this country of Spalding existed nowhere else.

This was a place and time, for example, where you could stop a student or fellow teacher on the way to a workshop and ask them their opinion about semicolons—and off you went. Where you were fellow citizens in the realm of sentences, dialogue, characters, story. Where your tentative desire to write was openly encouraged. There was never any doubt that you belonged there. That was her doing.

Sena was there, everywhere. Faculty read from their work each evening, and the readings went late sometimes. By then, everyone was thoroughly depleted from a long, overflowing day—especially at the end of the week. But there Sena would be, sitting in the audience, attentive and engaged while others, like me, were nodding off or leaving early for the comfort of our hotel rooms. She closed the place each night. She was dedicated, and we wanted to follow her example.

Sena, fellow teacher Jody Lisberger and this writer, hopefully after our workshops.

Sena, fellow teacher Jody Lisberger and this writer, hopefully after our workshops.She gave everyone a kind of open permission to be themselves, to be the self in their heart of hearts. I felt each time I came to Louisville as if I’d been given a transfusion. A shot of purpose, an infusion of art. We were all exhausted at the end of the residency. We were spent. But we carried a fierce inspiration home with us that sustained us for weeks.

No writer is asked to do what they do. They’re doing something that for many, still, has no tangible purpose and does not fit in with traditional ideas of work. Sena and her program reassured you that it was not just acceptable but inevitable that you write.

I left Spalding in 2012. I took a job teaching at the University of New Orleans in their MFA program. Sena did not allow you to teach at Spalding and for a competing MFA program at the same time. Reasonable, but it was a sad day for me when I realized I would not be going back. But I, as have so many others, experienced those years in a foreign country where everyone speaks the same language. I still do.

November 7, 2024

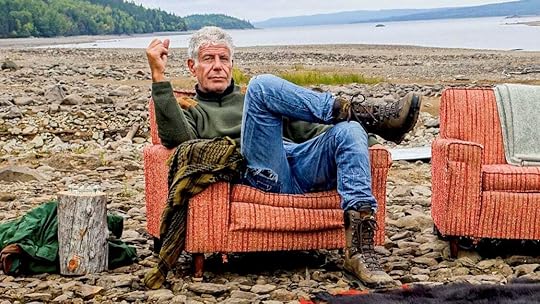

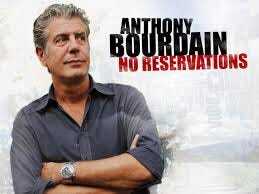

Missing Anthony Bourdain

I miss Anthony Bourdain. I miss him a lot. I know I’m just one of his legion—probably millions—of fans. But I need him. I need him here and now.

He told the truth. He told the truth uncompromisingly. And he told it with brio, guts and passion. With humor, that’s for sure. With wry gusto. And with doubt, anger, regret and yearning.

All his shows, in all their forms and configurations, had, at their core, a quest. It wasn’t simply a quest for good food. In fact, no show of his was ever just about food. It was a quest for understanding and for connecting—especially connecting—laced with a sense of adventure.

He was casual and companionable. He was opinionated and curious and, ultimately, the best guy to sit next to at a bar, have a beer with and talk about life, love and good food. His shows are incredibly fun to watch. And who doesn’t love good food? If you don’t, you are suspect to me.

His talking was profane, exhilarating and singular. It was a baritone as recognizable as Pavarotti’s voice. His vocabulary, his choice of words, was arresting and exact. The English language was his ally. He treated it well. He spoke with care. He used words judiciously and sharply, like cutting with a honed kitchen knife.

He spoke, during a visit with the poet and writer Jim Harrison, about the country where Harrison lived, “It is a place where some must follow the heart’s affection, as to do otherwise would be unthinkable. Where others can pursue with uncommon vigor the truth of the imagination. Where people can hear their own inner voices with great clearness and live by what they hear.” How can you write better than that? What food writer but Bourdain writes about those matters so stirringly?

What did he stand for? Despite his pirate background, his druggy days—the hard stuff, too, heroin—his down-and-out past—which he often went into unabashedly—his at times rebellious, fuck-you attitude, he stood for some pretty traditional values.

He was for decency, for example. The worst thing you could do, in his mind, was to stiff a server, to mistreat the wait staff. “Because there is really no lower person in the world than someone who ends up stiffing waiters,” he said during a late night romp around Manhattan with his crew. “There is a 10th circle of hell for them.” He meant it.

“It’s a very weird place,” he said during an interview, “where I get paid to be myself.” That was part of his appeal. He was absolutely himself. What we all long to be. Genuinely ourselves. But that requires ignoring fear. And we often give in to fear and compromise—at least I do. We often conceal ourselves. Not Bourdain.

He was, despite his bravado, humble when he encountered a foreign place and a new culture. He was a guest. We took those rides with him to Vietnam—his favorite country and that he returned to many times—to Lebanon, to Argentina, to Haiti, to India, to the Congo, to, well, everywhere. He looked at his shows as stories.

“I detest competent, workmanlike storytelling,” he said. “I’d rather fail.” (Listen to the whole Bourdain philosophy here in an interview. Listen to his speech, to his choice of words.) And on occasion, by his own account, he did fail. You could see when he spoke about that, it bothered him greatly.

He did several shows about southern Louisiana, where we live, Cajun country. He liked being here and loved the cooking, especially a crawfish bisque he ate one evening. In fact, one of the cooks he spoke with during that visit we will see this weekend when we go to a local boucherie.

I can’t talk about Anthony Bourdain without giving you a link to one of his episodes about Vietnam, a country he had deep affection for and felt uncommonly close to. In this episode, he laments the loss of a woman who owned a restaurant he loved and who, in Bourdain’s words, was like a mother to him and to his crew. Bourdain’s encounters stayed with him, gave him solace and joy and sometimes haunted him. He was, you could see, a man of deep feeling.

There are some others who have tried to fill his place, but the shows I’ve seen are drab, spiritless. The hosts go to the foreign places, and the shows are competent, workmanlike. And bloodless. Manufactured enthusiasm without risk and without giving of themselves, without leaving something of themselves, as Bourdain always did. One host always sounds to me like he’s giving elocution lessons while he’s instructing you how to cook.

I can’t begin to properly cite even one-tenth of those television episodes Anthony Bourdain made. (Or his various obsessions outside of food.) Which is a good thing, because we have them to watch again and again, a huge store of brilliance and learning and pure pleasure. After you spend an hour with Anthony Bourdain traipsing in a country you’d never visit yourself or that you wouldn’t see as he did, you feel, well, happy. He has a good time, and you do, too. You’ve had the most appealing enlightenment.

I need his fearless honesty, his down-to-earthness, his humanity, his joie de vivre, his thirst for knowledge and connection, the singularity of his personality. His truth. I need it now.

October 31, 2024

Fore!

Some summers ago, I was in Denver visiting my sister and her family. One morning, someone suggested a game of golf.

I’d played golf only a few times in my life. But I figured, nice day, get some exercise, move the legs, see some scenery, try my hand at it. What the hell.

So, off we went to a course whose name I no longer remember. My brother and brother-in-law were playing and my nephew, too. Playing at a high altitude helped, since even a bad shot went farther in the thin air. The course was fairly narrow. Some new houses were being built on either side of the fairways.

Around the third hole, I realized I was actually having fun.

Not that I knew what the hell I was doing. I just reared back and let her rip. Sometimes the ball went somewhere, and sometimes it trickled off the tee disconsolately. I took a lot of mulligans. No one cared. Just a good time on the links.

Somewhere along the eighth hole, I teed up. It was a par five. I would have been happy with a ten. I wielded some kind of driver, a number five, if memory serves. I liked that little head. I did some obviously fake warm-up stuff, stepped up, reared back and swung. Thwack. Miraculously, the ball took off from the head of the club and sailed high and long.

For a while.

Then, mid-flight or so, the ball began to curve right. What’s that called? A slice? A hook? Well, whatever it’s called, it curved right and headed directly for the houses that flanked the side of the course.

“Uh-oh,” my brother-in-law said.

“Get ready to pay for a window,” my brother said.

I didn’t hear any glass breaking, but of course we were pretty far away.

“Nice shot,” my nephew said. “Even better if it had gone straight.”

We walked down the fairway until we came to where I thought the ball had gone. There was one house, and then, next to it, a house that was in the process of being built. I had followed the ball’s flight and thought it most likely landed there.

I walked to that unfinished house, the walls of which hadn’t been raised yet. Just the floors had been built. I encountered a man, obviously a carpenter, lying face up on the wood floor, arms outstretched, a hammer in his open hand. One of his fellow carpenters was kneeling next to him and saying,

“Dude! Dude! Can you hear me! Dude, are you ok?”

Next to the prostrate man was a golf ball. Indeed, as it turned out, it was my golf ball.

Restraining my urge to flee, I walked toward the unfortunate man who was moaning, but not dead. First stroke (no pun) of luck.

“Dude!” his friend said, “Speak to me!” And, thank the gods, the guy on his back began opening his eyes.

“Wh…whappened?” he asked dreamily.

“You got beaned by a golf ball, Dude. I think it was this dude who did it.” He looked at me. Everyone did.

“Hi there!” I said.

“Oh, my head hurts,” the injured party said, rubbing the back of his head.

But the fact is, he came around. He even sat up. I apologized like an insane man. I offered to take him to the hospital and pay whatever bill there might be, hoping an operation wouldn’t be necessary. Or a replacement. I felt awful. Here he was, working away, and, out of the blue, my golf ball finds his head.

“No, man,” he said, continuing to rub the back of his head. “That’s ok.”

“What are the odds of that happening?!?” I said cheerily, picking up my ball.

“With you, who knows,” my nephew said.

And guess what—it was ok. I got the man’s number and called him the next day. He couldn’t have been sweeter. I apologized again, but he really was all right about it.

For years afterward, I would hear that refrain at family gatherings,

“Dude! Dude! Can you hear me? Dude!”

I haven’t played golf since.

Thankfully, my family might add.

October 22, 2024

The language of cookbooks

Good cookbooks are more than collections of recipes.

They’re also books. To be read. I turn to them for the author’s presence on the page. I turn to them for the pulse and the blood of the writer. I turn to them for the author’s voice, which can be complex, learned, buoyant. Some voices are congenial. Some are warm. Some are funny. Some are all of the above. I like spending time with these authors. I like being in their presence.

Some cookbook authors clearly want to write more than they want to cook. They’re writers first. Food is a way for them to write about a country or a region or a city, about its people, its history and its culture. You can sense the recipes are secondary. I don’t mind that at all when the writing is exceptional. I take out a favorite cookbook to read and often don’t go near the stove.

M.F.K. Fisher is a writer like that. Her book, The Art of Eating, has recipes. I’ve tried a few. But that’s not why I read her. I read her because she’s a superb writer. As the poet W.H. Auden, reviewing that book, said, “Though it contains a number of recipes, The Art of Eating is a book for the library rather than the kitchen shelf.” He went on, “I do not know of anyone in the United States today who writes better prose.” He meant of any kind.

At one point in The Art of Eating, M.F.K. Fisher says, “People ask me: Why do you write about food, eating and drinking? Why don’t you write about the struggle for power and security, and about love, the way others do?

“They ask it accusingly, as if I were somehow gross, unfaithful to the honor of my craft.

“The easiest answer is to say that, like most humans, I am hungry. But there is more than that. It seems to me that our three basic needs, for food and security and love, are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot strongly think of one without the others. So it happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and warmth and the love of it and the hunger for it…and it is all one.”

M.F.K. Fisher

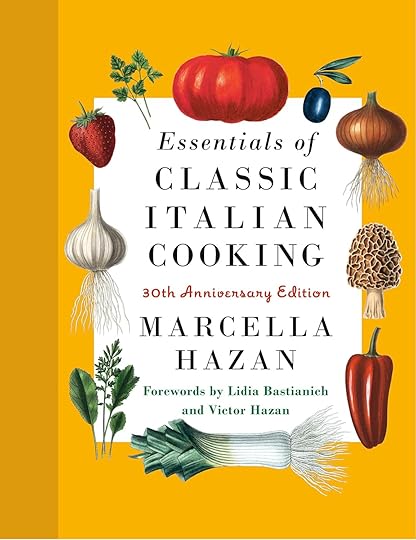

M.F.K. FisherThere are writers who give you both—delicious recipes and delicious prose. When that happens—heaven. Marcella Hazan is such a writer in my opinion. This is her description of anchovies,

“Of all the ingredients used in Italian cooking, none produces headier flavor than anchovies. It is an exceptionally adaptable flavor that accommodates itself to any role one wishes to assign it. Chopped anchovy dissolving into the cooking juices of a roast divests itself of its explicit identity while it contributes to the meat’s depth of taste. When brought to the foreground, as in a sauce for a pasta or with melted mozzarella, anchovy’s stirring call takes absolute command of our taste buds.”

That’s not just fine cookbook prose. That’s fine prose, period.

Her superb writing aside, so many of many of Marcella Hazan’s recipes are knockouts. The best. Have you tried her roast chicken with lemons? Her Bolognese? Her tomato sauce with onion and butter? I have three or four of her books. I thank her all the time.

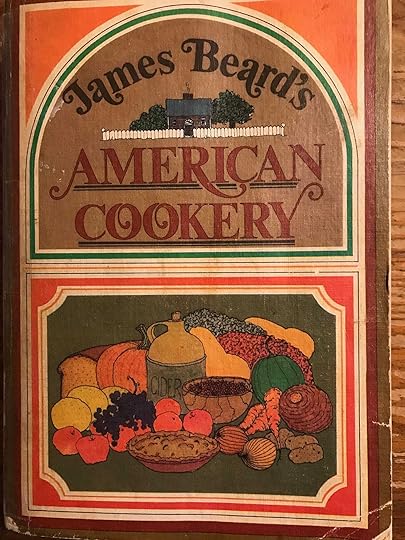

James Beard is another cookbook author in that class. No writer that I know of knows more about, and writes as well about, the history and evolution of American food. Reading him is a college education. He draws from his own profound knowledge as well as that gleaned from what seems every American cookbook ever written since Plymouth Rock. Here’s what he says about beets in James Beard’s American Cookery:

“The poor beet has suffered no end of unpopularity. This is quite beyond my understanding, for it is versatile and attractive and has good flavor. It has been in use since the Romans and seems to continue despite its enemies.”

I’m sure you could name many more. I’m sure you have your favorites. Cookbook authors whose prose is nourishing and, simply, desirable writing. Whose books are more than just reference books. Who give you themselves.

My copy

My copy“There is food in the bowl,” M.F.K. Fisher writes, “and more often than not, because of what honesty I have, there is nourishment in the heart, to feed the wilder, more insistent hungers.”

October 15, 2024

Digging in Louisiana

We got back home Friday evening at sunset. We’d been living in Chicago for five months, having left southern Louisiana in May to escape its hellish summer heat. It was a good summer in Chicago, but now we are home.

In three or four days back, my body has changed. My hands and legs have cuts. I have blisters from fire ant bites. I have scratches from blackberry thorns, which are knife-sharp and tenacious and draw blood. I have other marks I can’t account for.

I have cleared our three garden beds, which were overrun and sprawling with plants, dreadlocked and matted, some of which I didn’t recognize. They had settled in like squatters. They didn’t want to be evicted. But I wanted my garden beds back, and I ripped them out. Gardening was one thing I missed sorely in Chicago. It gives me so much satisfaction

The three beds, reclaimed.

The three beds, reclaimed.In the process of weeding, I knelt next to the confines of the beds. I forgot about fire ants. You don’t see them on your strolls through Chicago. But they are here in Louisiana. I didn’t feel their bite at first. It was only after a few got hold of my skin that something told me I needed to stand up and do something. Their bite is painful, a fierce, insect-y fire. I had to experience this more than once before I became more vigilant. And wear gloves and long pants. The sores remain. Badges.

What I do when I garden is bend, dig and pull. Basic, simple words for basic, simple tasks. I thrust my hands into the clean dirt. I sense the dark soil against my skin. I smell its earthy perfume. I am happy.

I missed manual labor in Chicago. A big city doesn’t provide as many opportunities for this as the country does. There are simple but sometimes strenuous tasks to perform here on our land in Louisiana, and I like doing them. My wife thanks me for doing them, and there is pleasure in your wife appreciating your work well done. If you can’t impress your wife, who can you impress?

One of the reclaimed beds, planted with winter vegetables.

One of the reclaimed beds, planted with winter vegetables.As a writer, I’m never sure if my work is any good. I try my best, and if I like what I’ve written and like reading it myself, that’s all I can do. There is no objectivity in writing. But a cleared garden bed is a cleared bed. This is an objective truth. No one can refute that. I find great comfort in that.

One of my greatest friends died last week, Bob Finch, a heralded nature writer and a lovely man. I think of him from time time as I work. He enjoyed manual labor as well and knew the worth of it. At one time in his life he was a carpenter. He liked to chop and split wood, and when I visited him, I watched him have at it. I feel a kindship with his spirit as I work. It will take a long time to get used to the fact that he is no longer here.

I think of Seamus Heaney’s lovely poem, “Digging.” The poet, as a boy, watches his father and grandfather dig the earth for potatoes. He knows that he, as a grown man, will never match their skill. So instead of a spade, he will take a pen in his hand. “I’ll dig with it,” his poem concludes.

Writing is manual labor. Especially if you use a pen or pencil. You strain, you sweat, you grimace, you take deep breaths and go at it. A lot of times what you produce is a mess. All you’ve dug is a big hole.

My shovel.

My shovel.Often I’d rather have a shovel in my hands, dig dirt, turn it and extract weeds. It’s all so clear and so satisfying, and worth enduring the in-the-blood venom of a few fire ants. Besides, I like having the marks of that struggle on my body. Ink on the side of my writing hand just doesn’t get the same respect.

But a writer I am, and so I take my pen in my hand. And begin.

Watch over me, Bob, as I dig.

October 8, 2024

Robert Finch, writer

Robert Finch, the esteemed nature writer, died September 30 on his beloved Cape Cod. He was 81.

I met Bob at Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky, in 2005. We were paired to teach a creative nonfiction workshop as part of Spalding’s MFA in Writing program. We would teach many together. Thus began a nearly twenty-year friendship that I am mourning today and will continue to mourn for a very long time.

I want to provide some words about Bob, because he was a wonderful writer and wonderful friend, and the more people who know about his work, the better.

The expression “writer’s writer” is often used to describe certain kinds of writers. Usually that means their standards are pure and exacting and their sentences gems—clear, strong, lyrical and nearly impossible to improve. I would say that description fits Bob well. His peers—Annie Dillard, Bill Roorbach, Edward Hoagland, Barry Lopez and Marge Piercy to name a few—respected and admired his work, and they said so.

Bob Finch

Bob FinchNo eye looked more closely at what was right before him and no hand wrote more compellingly and revealingly about what that eye saw than his. I think of William Blake: “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower.” He saw that. All you need to do, for example, is read his marvelous essay, “Death of a Hornet,” from his collection of the same name, to see what I mean. He describes a hornet’s buzzing “like a yellow-and-black column of electricity slowly sizzling up the window pane.” It’s exciting and fulfilling to read his words.

Bob wrote about a hornet in his office or a spiderweb affixed to a boat and what, in a title of one of his radio pieces he called “a remarkable unremarkable event” and made that writing indelible with his keen eye and his surgeon-like prose. He saw in these intimacies large lessons to be learned. He was an appreciator of nature who never lost his sense of humility about nature, who never saw his own feelings and person as the larger subject.

Listen to almost any of his radio pieces his did for the local Cape Cod NPR station. For example, the aforementioned “Spiders on the Lake,” which was broadcast a year ago. It begins with a discovery of a spiderweb affixed to a boat and concludes with the possible fallibility of Darwin’s Origin of Species. How surely and genially—to use Annie Dillard’s description of his work—he led his readers. (Click here to find many more of his sharply-etched, highly entertaining radio essays.)

He wrote memorably about people he encountered as well. Look into The Iambics of Newfoundland. Read the first chapter about a hitchhiker Bob picked up and who gave the book its title. I’m smiling, having reread it just now.

The settings of his books were mainly two: Cape Cod, by far the most prominent, and Newfoundland, where he had a house for a number of years. His last book, which will be published posthumously, concerns Newfoundland. But it was Cape Cod, a place he knew as well as any person ever did, that captured his attention enduringly and inspired him the most.

He did not, as so many American writers do and have done, spend his career teaching at a college or university. His writing was free from the baleful eye of academia, originated and was nurtured solely by his own passions and standards. Those standards were high. He was a most generous friend and person, a warm presence, and he had a delightful sense of humor. But when it came to writing, he never compromised.

I’d send him my work from time to time, and he usually enjoyed it, but if he had something pointed to say about it, he did not hesitate. This is from a letter he wrote to me:

“I enjoyed this piece - I really did. But sometimes I wish you'd dig deeper. Not every time, but sometimes, regularly. I know you can - I've seen you do it. Being in a happy place, where you seem to be at this point, can make it harder, but as they say, "If writing were easy….

Your gadfly friend,

Bob.”

I can feel his strict gaze on these very words even now. I know some students at Spalding bristled at his rigor, but little did they know the privilege they had to be under that expert gaze. I hope they do know now.

I visited him at his home in Wellfleet on several occasions where he lived with his wife, Kathy, whom he adored. We would sit before his fireplace and discuss writing and books and writers. Because what was more interesting or important than that? He read widely and deeply. His curiosity was always famished. He urged me to read John O’Hara, for example, a writer popular in the 1940s and 1950s but who today is largely forgotten—especially The New York Stories. I got the book, read it, and saw that he was right, that O’Hara could indeed write, and we had many feasts on O’Hara’s work, sustaining me, at least, through one winter.

It was at Spalding where I was closest to Bob. We taught together, walked and talked together, and dined together, often with our friend Phil Deaver, a kindred spirit and another writer whose life was as pure a dedication to writing as to be a religious calling. The three of us had splendid times together and our friendship was the best thing to come out of my experience at Spalding. For that, I am forever grateful to Spalding. Bob wrote me once, “Oh Richard, I realize that when I write to you, I am trying to write us back to those evenings in Louisville we shared with Phil Deaver.” I never met two men I loved more.

I talked to Bob just a few days before he died. His voice was faltering, but he was still there, Bob Finch, the writer and curious spirit. Even weak, he was inimitable. He died a few days later and despite knowing he was on the verge, I was stunned. I still am. I feel less secure in the world now that he’s gone. And much sadder.

His writing will live as long as there are books and readers.