Richard Goodman's Blog

September 4, 2025

Write what you know

I was watching Merle Haggard on YouTube perform his song, “Sing Me Back Home.” The idea of writing a song about a man being led to the gas chamber is not what comes first to mind as a subject for a song. Unless you’re Merle Haggard. Haggard spent time in San Quentin, and in other prisons, and he knew what he was talking about. He wrote and sang what he knew, and that’s one reason this song sends chills down my spine. It’s hard for me to listen to that song without tearing up.

I thought while I watching him sing: well, what do I know? What can I write about? I don’t know prison. I don’t know war. I don’t know poverty. I don’t know profound illness.

What do I know?

I know loneliness. I know fear. I know cruelty. I know longing. I know abuse. I know the Flying Dutchman-like search for my father. I know shame. I know as a child wanting to kill myself. I know being beaten and humiliated by my father. I know being abandoned by my mother while she’s still in the house. I know running from love. I know telling my young child that her mother and I were divorcing. I know the look on her face. I know being laughed at. I know self-loathing. I know being a coward.

I know feeling dirt on my hands in a garden in the South of France. I know walking Paris when it’s brisk and cloudy, a black-and-white film. I know the excitement of living in the French Quarter in New Orleans. I know living cheaply and happily in the East Village in New York in the 1970s. I know getting a phone call telling me my first book had been accepted for publication. I know a lifelong friendship with a remarkable person. I know finding true love for the first time when I was in my 70s.

I know my hand moving a pen across the page writing sentences that people tell me they like to read. I know a wren’s song in the early morning. I know the briny scent of an ocean breeze.

I know turning 80.

I’ll write what I know.

August 28, 2025

Boy flying alone

This is a black-and-white memory.

I’m a boy, 12, traveling alone. The year is 1957. I’ve flown from Detroit, Michigan to Washington, DC, where I have to board another plane for Norfolk, Virginia. That’s where my father lives. It’s Christmas, and the terms of my parents’ divorce say that I have to be with my father during that holiday.

The airport is large and has many windows so I can watch the planes come and go. The planes have propellers. Sometimes two, sometimes four. I have to wait several hours for the plane to Norfolk. I sit on a chair and watch.

A man comes up to where I’m sitting. He’s tall. He’s wearing a suit. He has gray hair. He sits down next to me. He begins talking to me. I’ve never seen the man before. The man asks me where I came from and where I’m going. Am I traveling alone? I have no idea of what is right or wrong to say to the man. My sense of self has been blown apart by my parents’ divorce. I’m barely holding on.

The man is a stranger, and I know strangers are to be cautious about, but I don’t have the confidence to say, “Leave me alone.” Or, “My mom told me never to speak to strangers.” The man is a grown-up. Grown-ups are to be listened to.

The man tells me to look outside. There is a plane that has just arrived. Stairs have been pushed next to the open door of the airplane. People get off the plane and walk down the stairs. I watch them getting off the plane from inside the airport.

“You see that little girl,” the man says to me, pointing toward the plane’s stairs. I look. I can’t see who the man is talking about. I don’t see a little girl. Just a lot of people getting off the plane and walking down the stairs. Where is she?

“She just slipped and fell,” the man says. “You could see her underwear.”

The man’s face is close to my ear. He’s practically whispering. He laughs a little laugh.

“It was white,” the man says. “You could see all of it.” It feels like the man almost touched the girl. It’s as if he’s drinking something he likes to drink.

I begin to feel nervous. I’m not comfortable. I tell the man I have to go find my brother. The man smiles.

“Do you want something to eat?” the man says. “A hamburger? Hot dog? It’ll be my treat.”

I say no thank you. I have to go. I stand up and begin walking away. My brother isn’t there in the airport. There is no one I know in the airport. I walk into a gift shop. I stand next to a woman near the counter. I wait. I look back to where I had been sitting. The man is gone.

Why can’t someone kill the man?

Why can’t I kill the man?

Why not?

Would you miss him?

No one kills the man. No one stops the man. The man will be back. The man will talk to me as a boy. He will talk to you. Or to your son. Or to your grandson. Or to boys you don’t know. There will always be a man.

August 21, 2025

The old man and the pool

I just turned 80. That’s the Rubicon of aging, the line you cross when things start really f—g falling apart. We’re talking way outside warranty. I don’t want to do anything that lets the old man in, as the song goes.

So, no cruises. No bingo. No early bird specials. No plaid jackets. I want nothing to do with anything that dramatizes the fact that I. Am. Old.

And so no exercise classes in a pool with seniors. We’ve all seen them. Oldsters in the water moving about sluggishly and bouncing a few inches to 1960s rock music while someone exhorts them from the pool’s edge to “Come on, you can do it!”

Never.

Never?

Last week, I was visiting my friend Deborah Attoinese, a brilliant filmmaker whom I’ve known for 45 years. She lives in Los Angeles. A few weeks before I arrived, she e-mailed, “I want you to take this exercise class with me when you’re here. You’ll love it! I take it every morning at a pool near me.” Such was her enthusiasm about the class, I said yes, why not, sure, I’ll do it. Despite my horror at the idea.

So it was that very next morning after I arrived, she drove us to the pool. I had my bathing suit on already. When we arrived, there were clusters of women, and two men, standing around near the door waiting for the pool to open. They were all of a certain age.

Mine.

Or younger.

Mary, our leader, smiling and energetic, arrived. Everyone walked to the spacious outdoor pool. I followed everyone as they descended concrete stairs into the water in successive waves. The pool, Deborah had told me, was heated. Debatable. There were about forty-five women, those two men, and me.

We all found our spots in the pool, spread out like someone had planted us, one by one, in a garden. I was up to my chest in water. The class would last an hour.

Part of our class.

Part of our class.At this point, you may be asking yourself, “What’s the big deal? It’s just an exercise class.” I suppose you have me on that one. There is also something healthy about doing something you vowed never to do, especially if ego is the prime resistor. It shows that you’re not intractable. And intractability is often a sign of old age. (“I want my tapioca promptly at 5 o’clock, goddammit!!”)

Well, there I was, and there was no use bellyaching about it.

Mary was mic’d and wearing an enormous floppy hat to protect her from the sun. She took her position at the edge of the pool. There was a boom box next to her. She turned it on, and Van Morrison’s “Brown-eyed Girl” blasted out.

And…we were off. Mary began issuing directions and orders at a fast clip, moving along the edge, all the while joking and tossing asides.

“How many of you have brown eyes? Hmm? Raise your hands! You? You don’t have brown eyes, honey. They’re green.”

I found myself bouncing a few inches in the water. Then I found myself spreading my arms in and out against the water as she told us to.

“Come on, you can do it!” Mary exhorted us from the pool’s edge.

Selfie, having just emerged from the pool. Neck is not my own.

Selfie, having just emerged from the pool. Neck is not my own.On I went, bouncing and moving my arms back and forth, up and down, against the water. I wasn’t very good at it. Most everyone was better. They were following Mary step by step, move by move. I was going through the motions. Fortunately, being chest-deep in the water hid a lot of my gracelessness.

I suddenly had the bizarre concern that I wouldn’t be asked back. I was just too clumsy, too slow. Because none of these people seemed to be slow. In fact, I was a bit winded.

Mary, our leader, left, two of my pool mates, and the old man.

Mary, our leader, left, two of my pool mates, and the old man. I wasn’t particularly enjoying this, but that was mainly, I think, because I don’t like exercising in the morning, especially in the water. The problem with water is that it’s wet. But if I don’t want to let the old man in, I have to make myself new in any way I can. And one way to do that is to venture. Jump in.

Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline” started booming out of the boombox.

Everybody began singing along.

Sweet Caroline! Oh Oh Oh!

Good times never seemed so good

I've been inclined…

My hand went up in the air. I could hear myself sing,

Oh Oh Oh! To believe they never would!

August 14, 2025

Magellan and the voyage to the land of pancakes

As a child, I started going out into the world. First, next door, then, later, down the street, and then, a few blocks away, where Henry Clay Hofheimer and his family lived. He was a friend and business associate of my father’s. We lived in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and his house, like ours, was near the ocean. He and his family came there in the summer to escape the heat in the city of Norfolk.

Families are different, I discovered in my travels.

I was surprised not to find my own little self-contained world. His family didn’t act the same as mine. They treated each other differently. Those first venturings were, in their own way, Magellan-like. I was discovering new cultures and new customs, some so strange to me that I was taken aback.

I must have been about 8 or 9. I remember walking down a back road from our house to his, a road that went up and down and sand flowed across it. I walked barefoot. It seemed like a big adventure, like I was going very far, when it was really only a few blocks.

My brother, sister and I used to go to Mr. Hofheimer’s house on Sunday mornings for pancakes. He offered us an open invitation. We wouldn’t go every Sunday, but when we did, it was wonderful. Henry Clay, as he told us to call him, had three daughters, Elise, Linda and Clay. They were older than we were and nice enough to us. But it was Henry Clay Hofheimer himself who made the pancakes. He wore an apron and served them up hot with lots of butter and syrup, just like any kid would want them. I received my plate like a gift. Two or three fat pancakes were all mine! I sat down, and I ate them all.

I couldn’t always understand Henry Clay. He spoke through a mouth that seemed to hardly open, and he spoke quickly. He was bald, but wasn’t bald-bald. He had a semicircle of hair going from ear to ear. When he laughed, it was a chortle, never full-fledged, almost private. He smiled but not widely. He was somewhat formal, but he was warm. He liked us being there. I felt that.

Henry Clay Hofheimer, maker of pancakes.

Henry Clay Hofheimer, maker of pancakes.Those voyages to Henry Clay’s house opened my eyes and shattered a kind of protective innocence I had.

I learned that my world was not the same as other people’s worlds. I met a father who was kind, welcoming, who spoke to me as if I had a mind, as if I could understand, and that I could have an exchange of words with. This was a family that was kind to each other as well. They listened to each other. They laughed.

Anything that was different from my world somehow, somewhere, felt wrong to me. Should they be doing this, I thought? We didn’t do this at our house.

So, with the delight of eating those thick, dripping pancakes, so warm and soft and good in my mouth, came a sense of guilt. This is not how we did it in my home. We didn’t eat pancakes on Sunday morning. And if we did, my father didn’t make them. He didn’t ask if I wanted more or if they tasted good. He didn’t ask me what I planned to do that day or my sister, or brother.

Happiness overcame guilt, though. At least while I was there at Henry Clay’s house. The strangeness and slight discomfort and newness of being treated kindly, as a person, like learning a new language, was cast aside by the exhilaration of being looked in the eye and spoken to and responded to. And fed.

Something deep inside me, away in a little hidden corner, understood that this was the way it should be.

August 7, 2025

The wrens take wing

My wife’s bicycle hangs from our porch ceiling and has been as long as I’ve been living here. It is an old model, heavy and sturdy, with a wicker basket attached to its handlebars. It’s been unused for, I think, years. There is a bird’s nest inside the basket, vacant for a while now. Because the bike is hanging upside down, the handlebars and the attached basket are near the ceiling, so it’s out of harm’s way.

We have birds, notably Carolina Wrens, around our home where my wife, Gaywynn, and I live in South Louisiana. The Carolina Wren is one of my favorites. It’s a winning little bird, unafraid, with a big, operatic voice and a cocky, upturned tail. Audubon.org says it’s “richly colored: chestnut above, butterscotch below, with bold white eyebrow.” Its brilliant song is “sung all day long in all seasons.” It’s the first bird song I hear in the morning, a delight.

The other day, I noticed a wren darting about near our porch and then, in a flash, flying into the wicker basket. Was the nest being used? Wouldn’t that be grand! I alerted Gaywynn.

I wanted to check to see if this was, in fact, the case. I fetched a small stepladder, placed it near the bicycle, and climbed its two steps to look inside the basket. My probing eyes were met by two much smaller bird eyes staring back at me. We looked at each other for an instant, both of us surprised. I quickly descended the ladder. I didn’t want to scare the bird any more than I had. I went inside, told Gaywynn, and we both literally jumped for joy. A bird was nesting in our bicycle basket! We felt like parents—or, at least, grandparents.

The nest.

The nest.We have a window in the kitchen that looks out to the bicycle and to its basket. (You can see the window just to the right of the bicycle in the photo above.) You can also see that the basket’s wicker strands are not woven close together. So when the wren visited its nest, we could see its silhouette as it moved about, a little shadow puppet.

Last Saturday, my wife’s son, Nelson, came from New Orleans for a visit. He used to live in this house, and he knows it well and has great affection for it. Part of the reason for his visit was to help with whatever needed to be repaired in the house and to help clear our raised garden beds. After a few hours of labor in the scalding Louisiana sun, we took a break and went inside for relief and some water.

At one point, Nelson looked out the back window. He saw something. He called us. There was a little wren perched on the screen door that opens to the laundry room, close by to the bicycle and the nest. It was even smaller than the wren we usually see flying near the house. Clearly, it was a fledgling. It didn’t have the classic upturned cocky tail, just a stub. I guess they grow that later.

“Look! It’s a baby!” Gaywynn said. We were all smiling huge cinematic smiles.

The little fledgling clung there. Like all the bird cam videos we’ve seen with fledglings on the brink, it couldn’t make up its mind to take flight. Would it? Could it? We all worried that it might just tumble to the porch floor. Then what? Just a few weeks ago, I heard a lecture by a bird rehabilitator who said you shouldn’t interfere in a situation like that. The mother would come. But what could the mother do? She couldn’t lift her baby back into the nest.

Fledgling wren.

Fledgling wren.We worried for the little bird. It looked anxious. But it had something pure and unerring on its side—nature and nature’s guiding strength, instinct.

When I think of witnessing this, I think of my daughter, who will soon be on a plane, flying to London, about to begin a new journey of her own. I stand here, far away, in Louisiana, cheering her on, earnestly hoping for the best for her, concerned, but knowing she’s on her own, trying to negotiate life’s currents, a bright spirit making her way, her young wings moving her to where she needs to go.

“Look!” Gaywynn said. She pointed to the bicycle’s basket. “There’s another!”

And, sure enough, there was. A second diminutive bird was standing on the edge of the wicker basket. All of a sudden it flew to join its sibling on the edge of the screen door. The two of them clung there together, edging closer to one another, poised. This was not a bird cam. This was real life. This was here and now.

“Come on, you guys!” one of us said. I think it was me. “You can do it!”

Then, suddenly, one of the fledglings flew off into a tree nearby. Just like that. We cheered, as if we were watching Lindberg take off. A few seconds later, the other followed. We cheered again. They were off to live their wren lives.

It felt like we were midwives. That somehow, with our urgings, we had helped these first flights occur. Watching these two beginnings made us jubilant the rest of the day. And even now, as I write these words, seeing, in my mind’s eye, the little wrens fly away, one after another, lifts my spirits high.

July 31, 2025

I become an influencer

I’ve decided to become an influencer.

I think I might have the knack. Something tells me I do.

What exactly is an influencer, you may ask? Like me, you may have seen or heard this term on social media. It’s usually applied to a young person talking online about arcane matters from their bedroom. I found this definition:

“To define an influencer in the simplest terms, it means any person who influences the behavior of others.”

So, how do I accomplish this?

I went to the website, How to Become an Influencer in 10 Steps. I read it carefully. Several times.

Now I was ready to influence!

In terms of who I influence, I think I’ll start with my dog. She hasn’t been responding to my commands—or, really, to anything I say—for some time. Well, to be truthful, she never has. I have no influence over her at all.

In my new role as an influencer, I’ve decided to change that.

I’ve noticed that a lot of influencers have videos. So, I made my very first influencer video. In this video, you will see how I use my newfound knowledge to influence my dog. Obviously, I can’t influence my dog to buy anything. Yet. But I can use this opportunity to demonstrate my potential as a nation-wide influencer. This potential will become fully apparent when I begin influencing actual humans.

Have a look at what clearly is the beginning of a long, storied career:

As you can plainly see that while this may not be considered by some a major success, it clearly shows I have a knack at influencing. A talent, you might even say!

I’m going to be working hard in the next days and months to become the influencer I was meant to be.

Watch this space.

July 24, 2025

Angie

Angie Alexander owned a clothing store in Virginia Beach, Virginia, the resort town on the Atlantic Ocean where I grew up in the 1960s. All the kids bought their suits there and, in the summer, their Bermuda shorts and short-sleeved Madras shirts. The store was called Alexander-Beegle.

Angie was a gregarious, theatrical man, good-natured and energetic. He was stocky, dark-haired. He moved about the room like a ballet dancer, spinning his body halfway around to greet a new customer, easing gracefully to another part of the store to reach for a garment. The last time I walked into his store, many years ago, he greeted me with a flourish, “Mister Goodman! Always a pleasure! What have you been up to?”

When I walked into his store as a teenager, raised in conservative, conforming Virginia, Angie’s gusto made me see there might be a different world than what I encountered everywhere. He wasn’t like the typical held-back adults from my parents’ world. He bubbled life, like champagne. He offered it directly to me.

Angie Alexander in his store

Angie Alexander in his storeI’d finished graduate school at that point. Most of my clothes-buying days at Alexander-Beegle were over, but I always liked to visit and say hello. It had been a while.

“I’m living in New York,” I said.

“The Big Apple!” He let out a contented sigh.

“Yes.”

“Pray tell, where?”

“In Greenwich Village. On West Twelfth Street.”

He became reflective. “I lived in the Village once. On Grove Street. A hundred years ago.”

I knew that street well. “Really? That’s a great street, Grove Street. Did you like living there?”

“Loved it. Every single minute.”

“What were you doing there?”

“Trying to be an actor.”

Of course! It made perfect sense! His store was theater. His selling clothes was a performance, with his deft flourishes and wit, his voice raised then lowered, often in the same sentence, his timing perfect. He probably could have sold tickets.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Wasn’t good enough.”

“You left?”

“Had to. Ran out of money.”

It felt a bit wrong, my probing of this abandoned dream. But I was fascinated by Angie’s New York days. He looked out the store window, to the vague distance, uncharacteristically silent. It only lasted an instant.

“Did you ever think about trying again?” I asked.

“Too late. Too old.”

In that moment, I was looking at a young actor in New York City, fueled by dreams. It’s such a hard calling, so punishing, acting. The odds are high against you. You need the unwavering faith of a true believer. You need resilience and thick-skinned optimism. You need bottomless stores of resolve. In my few years living in New York, I’d already seen many young actors I knew abandon ship, unable to hold on, slipping away to careers in real estate and banking and law—and, of course, parenthood.

Angie turned to me and said,

“Now—what can we do for you today?”

I mumbled something about needing a sweater.

“Ah!” He waved a directing hand. “Follow me!”

I wanted to root for the young Angie, to tell him that he could do it. Stay a little longer! But that wasn’t my place or my choice. And who was I to say what made him content and fulfilled? Look what he gave to people—a personal performance where they were, at least briefly, the only one in the audience. He’d founded his own theater in Alexander-Beegle, and I loved going to the matinees, always leaving uplifted and satisfied, with much more than just a garment.

July 17, 2025

Flight

“I remember when we had a big scavenger hunt in Dayton when I was a teenager,” my mother said to me once. I’d been asking her about her girlhood. “One of the things we had to get was the signature of Dayton’s most important man.”

This would have been sometime in the 1930s before my mother went off to college from her home in Dayton, Ohio.

“Everybody went to get the signature of the president of Dayton’s biggest bank. Some of them went to get the mayor’s signature.”

“Whose signature did you get?” I asked her.

“I got Orville Wright’s signature.”

“Orville Wright?” I said. “He was still alive?”

“Oh, yes. He lived in a big house on a hill.”

It was true. I looked it up. Both brothers were from Dayton. Wilbur Wright died in 1912. But Orville Wright lived until 1948. Since I always thought of the Wright Brothers stuck in that 1903 black and white photograph on that windy beach at Kitty Hawk in North Carolina, it was hard for me to think of one of them still alive, even in the 1930s, when my mother was a girl.

First flight, December 17, 1903

First flight, December 17, 1903“What did you do? Did you just knock on his door?”

“Yes. I did. He came to the door himself. He was very nice.”

“He gave you his signature? Just like that?”

“Yes,” she said calmly, as if it were nothing. “I’d been there before, actually.”

“What?”

“We would go to his house on Halloween. All the kids did. He always gave us candy.”

I had to bend my mind around this. My mother had seen and spoken to one of the Wright Brothers. Those men in the bowler hats. Who invented the airplane.

Orville and Wilbur Wright

Orville and Wilbur WrightAs a boy growing up in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where my mother and father went to live after they were married, we would take trips to the Outer Banks of North Carolina. We stopped at the Wright Brothers Memorial, a plain stone monolith on the top of a hill at Kitty Hawk. When we were there, my mother never told us that she’d met Orville Wright. That she’d been to his house. I don’t know why she didn’t. I don’t know what I would have thought if she’d said to me, “I met Orville Wright once.”

Memorial at Kitty Hawk

Memorial at Kitty Hawk“Another time,” she went on, “when I was a little girl, Charles Lindberg came to Dayton. This was after his flight across the Atlantic. He came to see Orville Wright, to pay his respects. A lot of us went to his house to see. Both of them walked out on the balcony and waved at us.”

That would have been 1927, and my mother would have been nine years old.

Charles Lindberg! Orville Wright! Those names! About as famous as any Americans ever were.

Orville Wright and Charles Lindberg

Orville Wright and Charles LindbergIn a way, my mother’s silence at Kitty Hawk was emblematic of her life in Virginia Beach where I grew up in the 1950s. The only thing I knew about her past when I was a boy was that she was from Dayton and that her parents, my grandparents, lived there.

I didn’t know she’d gone to college, to Wheaton, an esteemed women’s college in the east. I didn’t know then that after she graduated, she came back to Dayton and that she’d had her own newspaper column at the Dayton Daily News. It was called, “And Incidentally….” I didn’t know that she also wrote feature articles and did interviews for the paper before she married my father and left Dayton and her position on the paper to follow him to Virginia.

I didn’t know she loved classical music and that my father made her throw away all her phonograph records one day. I didn’t know that he hit her. I didn’t know anything about her, really, other than she was my mother, until she was much older and the rancor between us settled and I could ask her about her past and I learned all these things and more, including the story of Orville Wright.

When my parents divorced in 1957, my mother moved us north to St. Clair, Michigan, where her sister lived. My grandparents would drive up from Dayton to see us from time to time. That must have been a sad trip for them. To see their bright, able daughter, so unhappy, sometimes in drink, raising three children alone, in a small, cheerless house.

Mom, bridesmaid while at Wheaton

Mom, bridesmaid while at WheatonI’ve often wondered what my mother’s life would have been like if she’d never married. If she’d lived her life on her own terms, to the full measure of her powers. She was so smart and capable. Like so many women of her time, she didn’t have the encouragement to do that. She got married instead. I can’t regret that, because she had me.

Still, I can’t help but wonder what her life would have been like if, powered by her intelligence and by her passions, buoyed by the wind of hope, all vistas before her possible, she had taken flight.

July 10, 2025

Zaphra

A friend wrote to me that Zaphra Reskakis died recently. Even though she was 93 when she died, it’s still a shock, such was Zaphra’s vitality and thirst for life.

Maybe the first thing you should know about Zaphra—if you haven’t figured it out already from her last name—is that she was Greek. She was Greek through and through. Her parents came to America from Greece. She married a Greek-American. She spoke Greek. She thought Greek. She lived the Greek culture, talked about it, and, ultimately, wrote about it. Her e-mail address was yiayiazaph@… “Yiayia” means grandmom in Greek. Greece and all things Greek ran through her veins.

Zaphra

ZaphraShe was a small woman with a high sense of curiosity and chutzpah, or whatever the word for that is in Greek. The closest I can find in Google translate is θράσος, or thrásos, which means “audacity.” Yes, she was audacious, but calmly and doggedly so. She just did things. I met her in a writing class I taught at the West Side YMCA in New York many years ago.

She said that when she entered college, she told her parents she wanted to be a journalist. “They said, ‘No. You'll be running all over the world meeting men.’ So they pushed me to become a pharmacist, which they somehow thought was a mainly female profession. As it turned out, my class at Columbia was comprised of 90 boys and 10 girls.” She worked as a pharmacist all her life.

She later married—not well, according to her account. But she had her adored children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

She began writing late in life. Not only did she write, she published. Not only did she publish, she read her work on a semi-regular basis at the Cornelia Street Cafe in New York’s Greenwich Village. I saw her here, her diminutive figure just barely reaching over the microphone, reading her work and making people laugh. She was fearless.

Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village where Zaphra often read her work

Cornelia Street Cafe in Greenwich Village where Zaphra often read her workWhen she was a girl, her father at one point had—what else?—a Greek diner, called B-29, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and she wrote about that. That piece was published. She wrote about a (maybe) serial killer living next door to her. That piece was published.

The ever-ebullient Zaphra Reskakis

The ever-ebullient Zaphra ReskakisI would visit her from time to time at her apartment on West 52st and 8th Avenue. It was a small place, but it suited her fine. It was subsidized housing for older New Yorkers, and it looked pretty good to this broke writer, I can tell you.

She was adored by her children and grandchildren, and sometimes when I visited her, one of them would be there, attending to Yiayia and listening to her stories and eating her Greek sweets.

In later life, she was a translator for the Department of Justice. They needed people to translate wiretapped conversation they picked up by suspected criminals who spoke in Greek. She loved it. Eventually, she moved to an assisted care facility in Yonkers. She kept going, going, going.

We kept in touch sporadically. She was on Facebook, and we messaged. We e-mailed. She would comment on my Substack pieces, one of which was about how no one has ever seen the Gideons place a Bible in a hotel room, but clearly they do. Zaphra wrote me, “Love this. Maybe Gideon’s will deliver by drone as the elders age—just sayin.”

Zaphra, still telling her stories to the end.

Zaphra, still telling her stories to the end.As the writer Patty Dann, who also taught Zaphra writing, said about her, “She was an amazing person, with remarkable stories—she never ceased moving forward and trying new things—a real inspiration.”

So true, Patty, so true.

July 4, 2025

43 bis villa d'Alésia

The year is 1972. We’re young, Alex Jones and I. In our mid-twenties. We have decided to travel through Europe for as long as our money will last. We’ve quit our jobs and emptied our meager bank accounts. We have no responsibilities. We have enough money to travel for a year, at least. We have our shiny, unbroken backpacks. We meet up in Greece and travel through Eastern Europe that summer, storing up adventures and encounters.

Sometime that summer, as we are tramping along, Alex says, “We need to live in Paris.”

I’ve never been to Paris, so, I think—why not?

When we arrive, we go to the American Center where they have listings of apartments for rent by Americans for Americans. We find one for an apartment in the 14th arrondissement, wherever and whatever that is. The address is 43 bis villa d’Alésia. The short description sounds promising. It says it’s a studio apartment. That means small to me, but I decide to have a look anyway. I go there alone. The apartment is located on a pretty little curved street that is cobblestoned.

Villa d'Alésia, Paris

Villa d'Alésia, ParisI knock on the door, and it’s answered by Dorianne Lee, a young American woman from Hawaii who teaches English in Paris. She leads me up a flight of stairs to show me the apartment. I encounter a huge room. It has door-high windows that open to the street below. I almost gasp. I’ve never seen a place like this.

“I’m looking,” Dorianne says, noting me carefully, “for a female roommate.”

I realize this is an opportunity that must be seized. Oh, no, you aren’t, I think. You’re looking for two guys. And those two guys are Alex and me.

I return with Alex. He’s from Tennessee, and he can charm a spoon with his beguiling southern speak. So, after one or two hours of flattery, promises and little white lies, not to mention traveler’s checks, we convince Dorianne to accept us as roommates. I wonder, now, who was looking out for us? Someone, somewhere, I’m certain.

43 bis villa d’Alésia. At the top of the stairs, a door opened into the kitchen, which was spacious, friendly. Then, to the left, a doorway that led to the main room. It was a huge, light-filled room. It had been a painter’s studio. Thus, the description in the listing. Think of it: we were living in a painter’s studio in Paris! That was out of a book. Or out of a dream I was too inexperienced to have.

The vast room’s ceiling was two floors in height. The wall that faced the street was made entirely of glass, floor to ceiling. The glass was opaque. You couldn’t see through it, but a profusion of natural light entered the room. In the center of this glass wall were those two large doors, also of glass, that opened to the street. We threw them open in good weather, inviting all of Paris into our room. Sounds, smells, conversations, footsteps on the cobblestones below, the songs of birds, all became part of our every day. Not to mention the Parisian air, lightly traced with diesel and life.

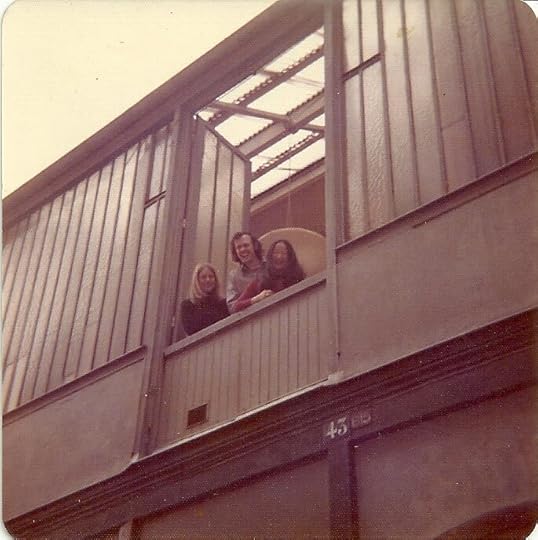

Looking up at our apartment at 43 bis. Alex (center) and Do (right), 1972

Looking up at our apartment at 43 bis. Alex (center) and Do (right), 1972Upstairs was Dorianne’s room and, beyond that, a second bedroom. From Do’s—everyone called her Do—room, there was a balcony from which you could look out onto the large main room below. This often became a stage where one of us, usually me, created manic, improvised, often interminable theater after dinner for everyone below. There was a round table in the atelier where we ate and talked and laughed and told stories and where guests sat when they came to eat Do’s wonderful food. Because Do was a wonderful cook.

The author at the entrance to 43 bis, 1972

The author at the entrance to 43 bis, 1972There were times when I’m sure Do might have regretted her decision to let these two rogues into her life, much less into her apartment. She was gracious and calm. We were coarse and boisterous. In the morning, on her way to work, she would inevitably encounter a half dozen empty wine bottles on the table and ashtrays heaped to overflowing with Gitanes and Gauloises, those harsh-tasting French cigarettes we smoked incessantly. She might have said no to us and saved herself from several near nervous breakdowns. But, years later, she’s still talking to us.

We had our place, our street, our neighborhood, our shops, our Métro stop.

Everything was new to me, and different, and had the ring of a place that was very sure of itself. I’d never been to a city that had nothing to prove. I saw different cars. Renault, Peugeot. What were these curious shapes? I saw workers in blue jumpsuits. Blue? Why? Street cleaners with brooms made of twigs.

My ignorance was bliss. It put me in a state of wonder and of learning. It threw me back in time to when I learned things for the first time as a boy. This time, though, the learning was thrilling.

At one moment, I don’t recall when, I knew. Perhaps after I’d had a jambon-beurre, a sandwich with ham and butter on half a fresh, crusty baguette that is not only cheap but scrumptious. Maybe it was when I saw that French money had pictures of artists on their bills, Saint-Exupéry, Debussy and Delacroix, and it was beautiful to look at.

Jambon-Beurre

Jambon-BeurreOr maybe it was when Alex and I sat in a bistro and were served our wine by men with long white aprons that stretched nearly to the floor with a confidence and surpassing dignity. Or maybe it was when I saw that buying things in shops, especially food, was far more than just a transaction. That it was a ritual of courtesy and patience.

The glory of tradition

The glory of traditionI don’t know. But I do know that a young man in his twenties suddenly knew, even if he couldn’t express it at the time in words, that people in Paris knew how to live. That this was a way you were supposed to live, how you were supposed to feel walking through the day, that life was to be lived well and fully and richly, every single moment of it.