Richard Goodman's Blog, page 2

June 28, 2025

Money

I can’t write a single post about the complexities of money. I can barely scratch the surface.

Money has caused such heartbreak and worry and brought so little joy. But it’s not going away, is it?

I was never in a household where money hung over our lives like the notorious pendulum in Poe’s pit. In which every cent counted. In which debts determined the emotional weather and consistently darkened the atmosphere. Later, I knew families who had chronic money problems, and I realized how ignorant I was about money. I witnessed the struggle and the worry. I saw how unforgiving money is.

Not having much money as a young man in my twenties, blithely on my own, was not a problem. That’s the way I lived in the East Village of New York City in the 1970s. Cheaply and well. I had everything I needed. I never really thought about what I didn’t have. When you’re young, you don’t need much to enjoy life.

That changed when I got married. My wife and I had a daughter. We needed things for her that cost money. Doctors, school, clothes, food. I had a passion to be a writer, but that has about as much chance of providing a reliable income as gambling on horses. Fortunately, my wife had a decent, steady income. We were like many married couples. We worried about money, but we covered the expenses—sometimes barely, but we did.

Then we divorced.

In New York, when I was a divorced dad and had a child to help support, I came up short on occasion. My jobs—guidebook writer, librarian, writing teacher, adjunct, dictionary editor—never brought in a lot of money. I always paid child support, but sometimes that made me unable to pay rent or the interest on credit cards I had maxed out. I had no savings. Money kept me awake at night.

Needing help, I asked my sister for money. I imagine it’s hard for anyone to ask for money. I know it was for me. The body flushes, pride takes a hard fall. There is no way you can feel good about yourself when you ask for money as a grown man approaching, or in, middle age. But I had responsibilities, and I needed to honor them. I swallowed my pride. I asked. She didn’t hesitate.

I learned a few things being a borrower. A person who comes to you hat in hand has probably already beaten themselves up considerably. It may be wise to consider you might be in that position one day—life constantly shocks and surprises. It’s hard to imagine going through life without once encountering dire money problems.

With some people, you pay interest on the money you borrow, and that interest is not paid in cash. It’s in the form of letting you know, subtly or even overtly, that they’ve lent or given you money, in case you forget. They exact a kind of implied subservience. My sister is not capable of that. I’m lucky to have had her in my life as angel and protector. I’ve thought of her example when I’ve rarely been in the position to loan or give someone money. Her example helps quell the worst in me. And I assure you, it’s there.

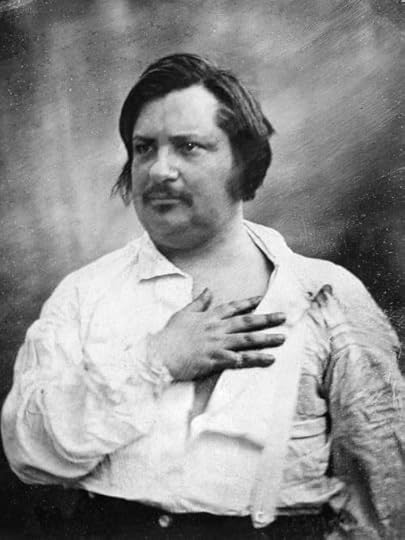

“Money,” wrote the great 19th century French novelist, Honoré de Balzac, “has never yet lost the smallest opportunity of proving its own stupidity.” Balzac was intimately familiar with money and the lack of it. He lived in a house—now a museum—under an assumed name to avoid his creditors. He had many. He still managed to write those masterpieces, including Cousin Bette, from which that maxim about money’s stupidity is taken. Money is at the heart of so many of his books, exerting its calculating influence.

Balzac, who knew a thing or two about money, especially not having it.

Balzac, who knew a thing or two about money, especially not having it.If you really want to see how stupid money is, observe any kind of inheritance where money is the central issue. Families can become unrecognizable. Bitterness, followed by plotting, emerges. Sides are taken. Money seeps through that situation like black ink on a paper towel, coloring decisions and responses darkly.

I take a bill out of my wallet. One dollar, five, ten or twenty. This innocuous paper! I remember seeing my father open his wallet when I was a kid and marveling at the slew of bills tucked in there. How rich he was, my dad! How magnificent to see all that green paper! Maybe someday I would have a wallet like his. It would be stuffed with tens and twenties and even bigger bills. I would have so much money I would never need more. I’m still waiting for that day.

I don’t want money to have the final word. But it’s a formidable and untiring adversary.

June 19, 2025

Frida

I went to an exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago a few days ago titled, “Frida Kahlo’s Month in Paris: A Friendship with Mary Reynolds.” Mary Reynolds was an American fine arts bookbinder who lived in Paris in the 1930s who had many friends in the Surrealist movement. Her lover was Marcel Duchamp. Kahlo went to Paris in 1939 at the behest of André Breton who wanted to include some of Kahlo’s paintings in an exhibition. While in Paris, Kahlo developed a kidney infection, and Mary Reynolds offered her apartment for Kahlo to recuperate. Thus her month in Paris.

It seemed to me an exhibition with a slim premise. If the size of the crowd was any indication, I could well be wrong about that. It doesn’t matter, because the exhibition allowed me to get a good look at some of Kahlo’s paintings, always an inspiration.

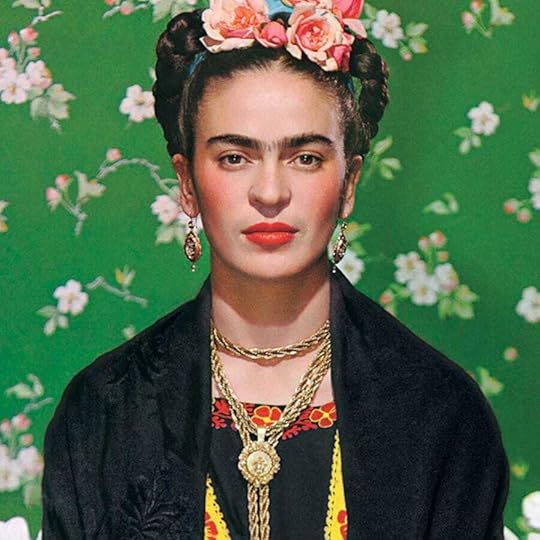

Fifty years ago, Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was not well known. That has radically changed. She’s on T-shirts now; a movie has been made of her life. When you say “Frida,” people know who you mean. Her face, with that dark unibrow, intense gaze and flowered hair has become as iconic as Picasso’s. If you want to know more, I might start here, where you can get a good overall idea of her life and work, including a sample of her remarkable diaries.

Many of her paintings are self-portraits, often dramatic and surreal—at times bloody and nightmarish. Has any artist been as fiercely, uncompromisingly truthful about themselves as she? When I look at a Frida Kahlo painting, especially a self-portrait, I am humbled by how brave she was in her life and art. She stands, or sits, naked before you, not literally (though sometimes) but in a more daring way: her soul is naked.

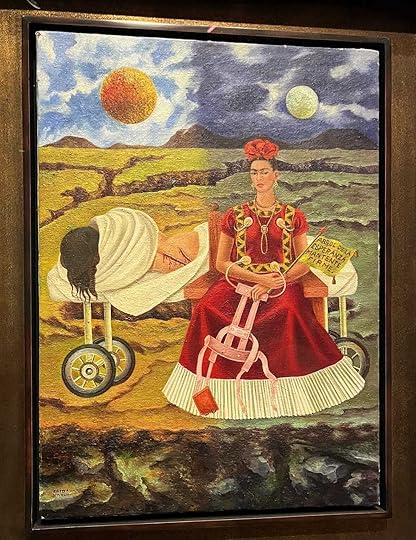

“Tree of Hope, Remain Strong.” Frida Kahlo, 1946.

“Tree of Hope, Remain Strong.” Frida Kahlo, 1946.Her life was full of pain, both extreme physical pain from a terrible bus accident when she was 18 that nearly killed her, and emotional pain from her labyrinthian relationship with her (twice) husband, the famed Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera. I would think now that many more people know about her and her work than about Diego Rivera’s.

There is a fierceness about her. A pride. She is quintessentially Mexican. She often wore vivid Tehuana dresses, from an indigenous culture in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. When she was away from Mexico, she was sad, she yearned to return.

Frida Kahlo.

Frida Kahlo.There aren’t that many Kahlo paintings in the exhibit. Still, a few are striking, pulsing with her bravery and skill. There is something that a painting can give your mind and heart, not to mention your eye, that no other art form can. There is a directness that paint—or whatever medium the artist uses—provides that your eyes drink. The painting doesn’t move, it doesn’t speak, it doesn’t make a melody. But it has a forthrightness that you absorb like a plant absorbs water.

Kahlo always gives you the truth, often in brutal images where she is suffering pain, where she can even be bloodied. If you want to see her at her most unflinching, look at her 1932 painting, Henry Ford Hospital, which depicts her miscarriage with a stark sense of loneliness and sorrow. But it isn’t just the shocking imagery that she gives you. It’s all of her, every single secret, every flaw, every disappointment, every yearning. Her paintings can be hard to see.

She also dispels any declaration that you can’t make yourself the overriding subject of your art with any lasting value. She did. She painted fifty-five self-portraits. Her work embodies Ezra Pound’s definition of literature, which I will broaden, “Art is news that stays news.” Kahlo’s work, which is to a great extent about her, is ever new.

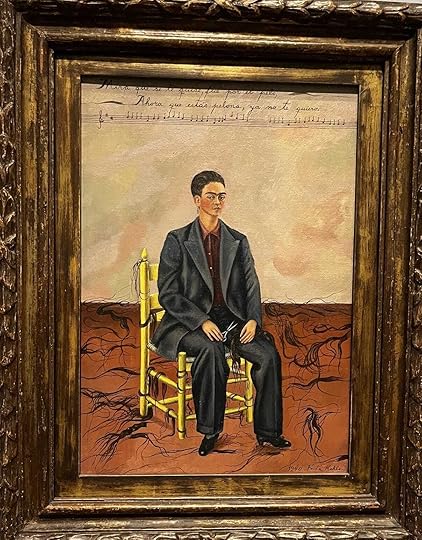

“Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair.” Frida Kahlo, 1940.

“Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair.” Frida Kahlo, 1940. The words at the top of the painting above from the exhibition, “Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair,” are taken from a popular song and are translated as, “Look, if I loved you it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore.” She painted this self-portrait in the wake of her divorce from Diego Rivera. It was painted eighty-five years ago but could have been painted yesterday.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.Rivera was not faithful. She wasn’t either. But Rivera’s infidelities were more frequent and in at least one case, cruel. He had an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister, who Kahlo adored. Kahlo said this about Diego Rivera, “I cannot speak of Diego as my husband because that term, when applied to him, is an absurdity. He never has been, nor will he ever be, anybody’s husband.”

After seeing the exhibition, I went to the Chicago Public Library to learn more about Kahlo. I found a book titled, Frida Kahlo: Face to Face, by the artist, Judy Chicago. It gave me a chance to see many of Kahlo’s works in a single volume, but Chicago’s offhandedness about Kahlo’s work, which sometimes borders on the dismissive, didn’t sit well with me. But seeing so many of Kahlo’s paintings was wonderful.

She is an artist who makes you think. You enter her world, with its troubles, pain, dilemmas, setbacks and beauty, and you become part of her struggle. You walk away from a Frida Kahlo painting elevated and also concerned.

If you are looking for someone who never averted her eyes, who spoke the truth always with paint and with words, look to Frida Kahlo. No braver artist ever lived.

June 12, 2025

New York City, summer of 1975

It is a sweltering summer day in August. Everyone with any sense has abandoned the city. Not you, though. You not only stay, you like it. It’s difficult to romanticize three-day old garbage in August heat. Still, you’re not appalled by the scent. Far from it. You think that if someone hasn’t spent a suffocating summer here they will never know the city completely.

You are a young man living in the East Village. It is 1975. The hot air sucks the breath out of you and hits you in the stomach. The heat is so fierce you have oasis shimmers in the back of your eyes, and you walk like a man with terminal heart disease. It is so hot, you have to be careful about touching streetlamps.

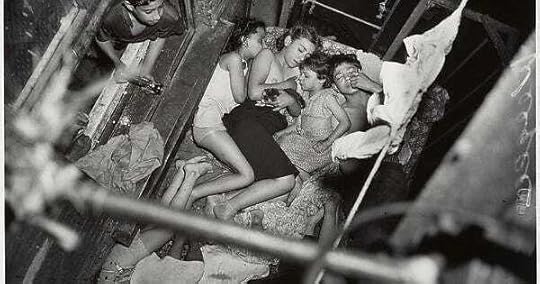

You are sitting on a stoop of a brownstone apartment next to people who live there. Some you know, some you don’t. The heat has forced you all out on the street. You are living in Elmer Rice’s city and in Weegee’s city and in Henry Roth’s city, a world you love, of ordinary people from another era.

There you all are, men and women, some younger, some older, all depleted from the heat, the women struggling against the despot of modesty, the men in armless T-shirts, or bare above the waist. Some, like you, have just moved to the city. Others have been here for decades with mayors now only in newsreels.

“Children on Fire Escape.” Photo by Weegee.

“Children on Fire Escape.” Photo by Weegee.You see women, normally vigilant about buttoned blouses and the high-water mark of skirts when they sit. They abandon all decorum. They have hair that sticks to sweaty necks, and the backs of the blouses are damp and flat against their back and the high backs of their skirts are damp, and so many blouse buttons are unbuttoned you believe in Santa Claus again. And when they sit on the stoops, they pull their skirts up high for any possible breeze, and this approaches the total sheet-discarding indifference of childbirth.

Still from “Street Scene” by Elmer Rice.

Still from “Street Scene” by Elmer Rice.Here on this stoop in the heat you encounter the oral tradition of storytelling from these urban griots. In the sultry evening, you listen to the man who went to parties where Kerouac sat on a couch and Ginsberg was there as well as Corso. What did they say, you ask? What were they like? You press them for the smallest details. You listen to the aged black superintendent who proudly says he saw Joe Lewis knock out Max Schmelling. And you say, you mean you were in there? And he says, yes, I was. And someone heard Emma Goldman speak once, in Union Square. You don’t know who Emma Goldman was yet, but you nod appreciatively.

You are part of summer city life, one that you never encountered before you came to New York and that you have grown to love. The unyielding heat produces an unlikely community of souls that wouldn’t assemble otherwise, and the building’s wide many-stepped stoop is ideal for this. Here you find an ease and familiarity with people you might normally pass wordlessly on the street. You’re joined in seeking relief in the stifling night on this stoop. The heat eliminates all hierarchy.

Here, everyone is a storyteller, and that’s what you want to be, too. You have a story you tell. It’s small and not as grand as theirs, but it’s yours and you dare to tell it. You are part of this oral tradition now, and the storytellers have cans of Schaefer beer and panting dogs and cigarettes glowing in the late evening, and you could listen all night, all night long.

June 5, 2025

Smoke alarm innovation!

We’ve all been rudely awakened, or startled, by a smoke alarm going off unexpectedly. And needlessly. It’s a relentless, piercingly-annoying sound. Yes, there probably was a bit of smoke, perhaps something burning in the oven, but nothing life-threatening. What’s worse, you often can’t get the bloody thing to shut up. It just keeps up its high-pitched screaming, the indoor equivalent of a never-ending car alarm.

Yet, we’re required, legally, to have them.

But now there’s an alternative. Invented by me!

Yes, I know what you’re thinking. How could a writer invent anything?

Well, it was out of pure frustration. I couldn’t stand the dog-pitch screeching of my smoke alarm anymore. So, I set to work. I read all the smoke alarm literature, much of it peer-reviewed. I consulted alarm scientists all around the country. I read the classic book on the subject, Smoke Alarms: How They Took Over the World.

Finally, after many false starts—isn’t that true of all great inventions? Look at Edison!—I came up with a revolutionary new smoke alarm. It’s unlike anything you’ve ever heard before. It eliminates completely that piercing sound we all hate. Yet, it will still alert you in case of smoke or, God forbid, a fire!

I’ve made a short video to demonstrate my invention. Here it is:

I know. I know. I’ve changed your life.

May 29, 2025

Surrendering to Provence

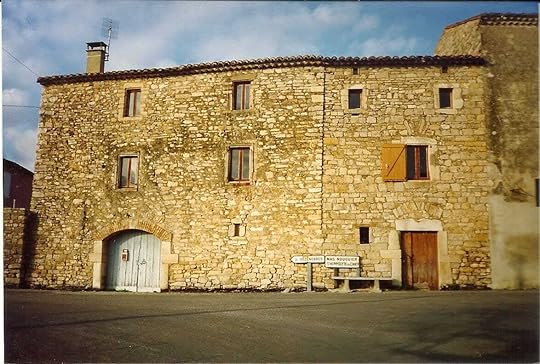

It was a stone house that was big and old with many rooms and walls as thick as a fortress. We lived there for a year in a small village in a corner of Provence about an hour from Avignon. My Dutch girlfriend and I were escaping New York City—just had had enough. New York had beat us down, as it does, every so often, everyone who lives there. New York—we loved you but we needed to separate from you for a while. Where would we go?

To the South of France. Why not? We had the fortune to find a place outside of time. It was a lovely way to live, in a house that had been built 200 years ago, hewn out of stone found not in quarries but in the fields.

It wasn’t easy at first. The village life seemed as durable and unchanging as the house and as mute. It was a while before she and I could begin to fathom the rhythm of its ways. Why didn’t the villagers respond to our greetings, except for the briefest answers? Why weren’t they the least bit interested in us? Why didn’t they accept us with open arms?

The house in Provence

The house in ProvenceA village in Provence can be exquisite and maddening. It took time for us to see that our sojourn was merely a blink in the villagers’ unwavering eyes. We did, at last, and it was the land that led us.

As she and I woke up day after day to a sun-flooded room, our casement windows open to the new morning, we began to become part of Provence. We couldn’t look out onto the softly undulating hills, with their legions of precisely-lined vine plants, without giving away our hearts. We couldn’t smell the subtle morning air, a perfume of everything that grew there, without becoming a little more lost in love with the place. We couldn’t have our vision enhanced by the marvel of the light without wanting never to leave.

The gap between their ways and ours lessened, and that was in part due to the power of the place. We were under its sway, and so many of the things that were important to the villagers became important to us.

We walked the rough little hills above the village and saw wild thyme growing. The plant is like a dwarf version of a stunted tundra tree, all twisted and leaning. It’s a tough thing, difficult to cut. I began using it in my cooking. I soon found the taste is not the same as domesticated thyme. Like many wild versions of a plant or spice we know, its flavor is more subtle and quieter and more interesting. It’s a good metaphor for some of the villagers we met. They were wild thyme. Their tastes weren’t revealed just by a single encounter.

Wild thyme

Wild thymeNo, we’d never be paysans—as the villagers unhesitatingly called themselves. Not farmers, peasants. They were people rooted to the land. Eventually, most everything in Provence comes back to the land. Pays, the root word of paysan, means “country.” If you visit Provence, try to walk in the maquis or the garrigue, the scrub hills, full of dry wonders and simplicity. Let yourself become part of this remarkable land. Day by day, we surrendered to its spirit.

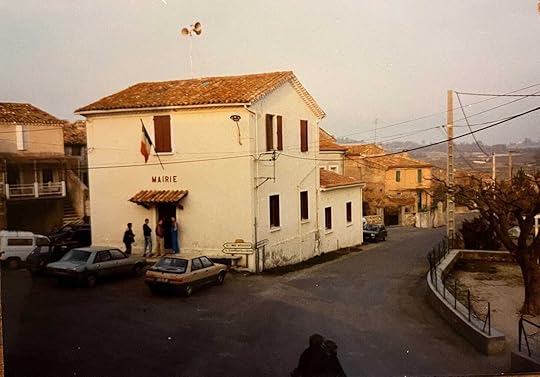

Town Hall

Town HallIn surrender, Provence simplified our lives. That’s what the place will do. Simplicity will come over anyone who stays there for even more than a few days. “Only in this sun-steeped country,” Colette writes, “can a heavy table, a wicker chair, an earthenware jar crowned with flowers, and a dish whose thick enameling has run over the edge, make a complete furnishing.”

We began to understand, like everyone else who has become attached to Provence, that there is no place on earth like it. No one can possibly prepare you for this consistently ethereal level of beauty. Not any book, movie, or essay. No painting. Not these words. Nowhere else do you find such a confluence of pellucid air, fierce sun, ravishing smells and tastes and grace.

It may not be your country, but it may not altogether foreign to you, either. As M.F.K. Fisher said of her first visit to Aix-en-Provence, “I was once more in my own place, an invader of what was already mine.” It may be singular, but you can become its citizen. You may feel as if you were born there, and perhaps you were.

We had a used car we had bought, scruffy and prone to seizures, but on the whole reliable. In it, we ventured near and far in the South of France and came to see much more of the land beyond our village during that year. We went to nearby Avignon first. What a shock it was to go from our little hamlet, with its stubbornly self-important ways, to a city that has had such a prominent role on the world stage. We—at least I—felt Avignon is a sad place. Even though it’s on the lyrical Rhône, that magnificent water, the city has a melancholy air. Cities have lived lives, too, and when you walk them, you begin to see exactly who they have become. I think of Avignon as not at peace with itself. For that very reason, it’s impossible to forget.

Road leaving the village

Road leaving the villageWe went to St.-Rémy in search of van Gogh’s ghost and then walked the sun-scorched hills nearby, the Alpilles, which he painted. We drove to Marseilles, a city as unjustly feared as New York, and that’s a pity, because Marseille is so sharply flavored and so alive. M.F.K. Fisher described the Marseille she loved as “mysterious, unknowable,” and I think it will haunt you and draw you back as it did her. We went to Nîmes and walked into its massive amphitheater and felt dread and awe in the face of the Roman Empire. We drove to L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue and watched trout swimming in the cool little stream and stayed in that pretty place until dusk at a table outdoors. We saw all these wonders and many more, and we continued to make forays into the heart of the heart of Provence all year.

Marseille

MarseilleBut no matter how far we went, we always came home to our village. To the well-wrought house that now was our home. To the simplicity and timelessness of a life that unfolded before us. We met everyone in the place, and we began to piece together their lives. We were even luckier to get work in the fields, so we experienced Provence’s light and air and scents throughout the long days. They paid us, too, in francs, by God! The wine tasted better in our dirt-caked hands, and so did the daube I cooked for us when the day was through.

It was a privilege to go to sleep weary in our village and to wake up with that slight feeling of reluctance physical labor bestows on you every morning. We had the gift of responsibility in Provence, and how much luckier can two people get? You cannot steal idle moments when everything is given to you.

We were not used to the hard work, to the bending, pulling, digging and planting. We were old people for an hour every morning, but nothing in the world would have induced us to quit. We went home to lunch at midday as the villagers did. We spooned our soup and devoured our bread happily with the morning’s cool still hovering over us. Sundays became as precious to us as long-awaited vacations. Nothing that year was sweeter than buying villagers we liked a pastis with money we earned working their land. If you can work in Provence, even for a single day, you should do it. It will bind you closer to the place.

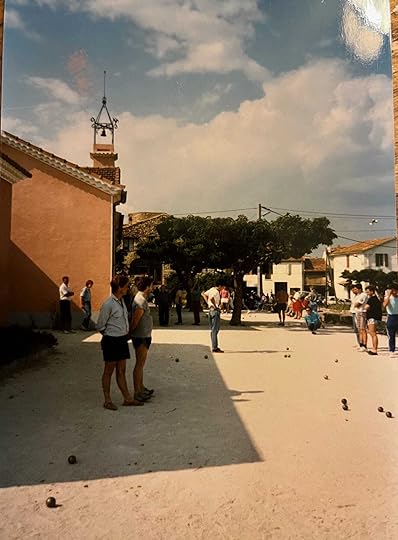

Playing pétanque, or boules, in the village.

Playing pétanque, or boules, in the village.Despite the fact that we were frugal and that we worked, we could see our money dwindling. This alarmed us and saddened us. We didn’t want to leave. We wanted to stay forever.

But we had to leave. We had to return to New York City, to that city we no longer felt was our home and wondered if it could ever be again. (It could.) We had to say goodbye to Provence, and to the village we had grown to love and that had taken root in our souls.

Colette’s words I quoted are from her book, Break of Day. If you love Provence, or you are going to Provence for the first time, I hope you read it. The prose is as potent and sensual as those Dionysian scents distilled from Provençal flowers in Grasse. Colette had a house in St.-Tropez, and she began staying there before that fishing village was anointed by Parisians to become the place to go to. Break of Day was published in 1928, but not an observation is obsolete. Her house was above the village, and she writes about gardening, the movements of the day, her animals, the people who come and go and the delicious, sensual tastes of the place. Here, Mother Nature doesn’t wear a silky dress; she walks naked. Colette writes with a pen dipped in sun, oil, sweat and salt.

“What a country!” she exclaims. “The invader endows it with villas and garages, with motorcars and dancehalls built to look like Mas. But during the course of the centuries how many ravishers have not fallen in love with such a captive? They arrive plotting to ruin her, stop suddenly and listen to her breathing in her sleep, and then, turning silent and respectful, they softly shut the gate in the fence. Submissive to your wishes, Provence…they have no other desire, Beauty, than to serve you and enjoy it.”

Go. Submit. Surrender.

May 22, 2025

The man who gave me Japan

He was a short, nervous, tightly-wound man. He always wore a coat and tie, most usually a bow tie—his dress was fastidious—which made him look like an accountant. His face was usually glistening with perspiration. His speech was somewhat pained, as if someone were forcing him to say words he never would have said otherwise.

He was Edward G. Seidensticker—that “G” followed him wherever he went—and he was a professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Michigan when I was enrolled there sixty years ago. He was my Magellan in the new world of Japan and its prose and poetry.

As a junior, I was looking to make the most of the four credits I could spend any way I wanted. I went to the Department of Asiatic Languages to consult with a graduate student friend who was majoring in Chinese. I had it in mind to take a course in Chinese literature.

“No,” he said, pulling out the course catalogue for the next semester. “Take this course.” It was Introduction to Japanese Literature, and the instructor had the unlikely name of Seidensticker.

“But…what about Chinese?”

“No. Take this course. He’s a giant.”

Edward Seidensticker was diminutive in stature, but, yes, he was a giant, although I didn’t know it at a time. When he walked into the classroom for the first time—I think there were just seven or eight of us—I thought, seeing how unlikely, how un-towering he looked, that I had made a grave error. I was thrown, too, by his choked, somewhat agonized way of speaking.

I got over that as soon as I started listening. What knowledge. What authority. What credibility.

Edward G. Seidensticker, in an uncharacteristically informal look, years after my class with him.

Edward G. Seidensticker, in an uncharacteristically informal look, years after my class with him.I knew nothing—and I mean nothing—about Japanese literature. I didn’t even know there was any such thing. I certainly didn’t know that Edward Seidensticker was one of the great translators of Japanese literature. (His major opus, the translation of The Tale of Genji, was still to come, ten years later.) I didn’t know that he was a friend of Yukio Mishima and Yasunari Kawabata, Japan’s first Nobel Prize winner. And that, by all standards, he was one of the great scholars of Japanese literature in the world at the time.

In his class, we studied Japanese poetry and prose from the earliest days until the present. So, we read Arthur Waley’s translation of the eleventh century masterpiece, The Tale of Genji, by Lady Murasaki Shikibu—or, as Professor Seidensticker would prefer to say, the Genji Monogatari, giving it its Japanese name. Japanese vowels are pronounced like Italian vowels, so students could actually say some of the names of books and authors. It made us feel worldly.

We also read excerpts from Sei Shōnagon's Pillow Book from the tenth century. (You can read her “Hateful Things” in The Art of the Personal Essay, edited by Philip Lopate.) Professor Seidensticker talked about these books as if he had personally known their authors, and, who knows, maybe he had. But for me who, somewhere, knew he wanted to be a writer, who wanted to throw his lot in with that calling, it was the Japanese poetry, not prose, that Edward Seidensticker taught and discussed that grabbed me by the heart and still does.

In order to understand the full impact of this class, allow me to elaborate on my ignorance. To me, the idea that a culture other than our own could have produced poetry of the highest order in the 8th century was, well, inconceivable. But here was this somewhat agitated, sweating, highly intense man telling me about a compilation of Japanese poetry called the Man’yōshū—The Book of Ten Thousand Leaves, as he translated the title. This was a book, Japan’s greatest book of poetry, compiled sometime in the middle of the eighth century on which there were poems from the fourth century to the eighth. I have a copy, still.

The truth is, I wasn’t a good student. I don’t mean I wasn’t smart enough. I was lazy. I was what they used to call a malingerer. I was negligent. I skipped classes. I didn’t do the readings. I wrote mediocre papers. It’s far too late in the game to be ashamed of this, but what I am is slightly melancholy, a perfect Japanese emotion, one those ancient poets often spoke to when they wrote about the briefness of life and how we are reminded of that by nature, especially so in the fall when the leaves fall and geese are calling as they fly in chevrons overhead.

In his half-agitated, half-shy way, Professor Seidensticker revealed the great voices of the Japanese poetic past. I still remember the names sixty years later: Akahito, Yakamuchi, Okura and Otomaro. But the poet who I am forever grateful to him for introducing me to is Kakinomoto no Hitomaro. When Professor Seidensticker spoke of him, he had a faraway look, as if he were transporting himself back to the end of the seventh century when Hitomaro lived.

17th century artist’s rendition of Hitomaro

17th century artist’s rendition of Hitomaro“Hitomaro was one of Japan’s six poetic saints,” the professor said, “and many think—as I personally do—that he was the greatest. We don’t know anything about him, except that he was married and had a child. It appears he was married twice. But it was about his first wife that he wrote so movingly and…so memorably.”

He had the Man'yōshū in Japanese as well as in English, and sometimes he would read us the Japanese first and then the translation. He did this with Hitomaro, and I wish I had the transliteration of the poem in Japanese, because I would print it here for you to read, even in this foreign language, the better to feel that moment when Professor Seidensticker read the Japanese words and, finishing, simply said,

“Wonderful. Wonderful.”

The poem he read from was “After the Death of His Wife.” He read the passage next in English:

In the days when my wife lived,

We went out to the embankment near by—

We two, hand in hand—

To view the elm-trees standing there

With their outspreading branches

Thick with spring leaves.

Abundant as their greenery

Was my love. On her leaned my soul.

But who evades mortality?—

One morning she was gone, flown like an early bird.

“Now,” he said, “if that doesn’t move you, there’s little I can do for you.”

Even then, as a punky, negligent college junior, I had to agree. What Kakinomoto no Hitomaro taught me was that this man with his “sleeves…wetted through with tears,” as he writes in his grief, could reach across 1300 years and touch me. That great art in its humanity is immortal. This man who walked the mountains in search of his dead wife, and who wrote, “But it avails me not, / For of my wife, as she lived in this world, / I find not the faintest shadow,” had the kind of compassionate heart I wanted to show on the page—if it was there, and I hoped and prayed it was. Hitomaro wrote the way I longed to write—he did in 690 AD!—and he wasn’t afraid. If I couldn’t stand beside Hitomaro, perhaps I could at least stand in his shadow, and that would be enough.

Professor Seidensticker led us through hundreds of years of Japanese literature, and he was a thrilling guide. But nothing, for me, equaled his talk about the Man'yōshū. I remember once he was talking about Ezra Pound’s translations from the Japanese. I don’t think he was too impressed. He had a kind of knowing smirk on his face and said,

“I really don’t think he knew much Japanese at all. I mean, it appears he always had help.”

But then he paused, and said,

“Well, but he did write, ‘Ariwara…Ariwara…Ariwara no Narihira.” It was music, as he said it to us. Then Professor Seidensticker titled his head and, with a small smile said, “He may have been slightly crazy, but once in a while, Pound did some wonderful things.”

As did Professor Edward G. Seidensticker, every day.

May 15, 2025

Finding grace in airports

When you travel by plane, you spend time, of course, in airports. That time can be expeditious, frustrating, wearying and, sometimes, a ball wrecker of plans. We all have stories.

There’s another side to that time spent in airports. It’s one of the few places where you can see, at least in larger airports, a cross section of humanity. And, if you’re not in a rush, where you can observe them closely.

I see all sorts. Single businessmen walking determinedly, speaking earnestly to their cell phones, saying the Most Important Things. College kids slouched in chairs wrapped in earphones, snacks strewn about, intently gazing at their phone screens.

A group traveling together all wearing the same unavoidable T-shirts.

And families.

I see young families. Some look breathtakingly young. They have one, two, three children, one of them maybe three weeks old. They have their retinue of carriages, tote bags, snacks, diaper bags and God knows what else, in that half-insane idea of flying from one place to another together.

I think back to the time when my wife and I had a young child, and a wave of nostalgia and protectiveness comes over me. It’s a small-smile moment for me, accompanied by wistfulness and thoughts of how rapidly time—yes, I’m in an airport—flies.

I remember what it’s like being a young parent. It takes a great deal of patience and teamwork to make this traveling with a family work. Sometimes the parents are not too good to one another; they’re perfunctory. That’s hard to see. But more often than not, the parents are good to each other. They’re a team.

The other day I was in the Dallas Airport on a layover on my way back home. Terminal C. Lots of travelers. I was seated at a table eating my Shake Shack burger looking at a young couple at the next table.

They had two kids. One was a little girl in a carriage. I didn’t see the other kid at first. Then the mother raised it up, a baby, hugged it, then held it high. She put the baby back and sat down across from a man who I assumed was her husband. They were both young. (What’s young? I hardly know anymore.) They were eating and talking about something and then pausing to talk to their older kid. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, even with discretionary straining. I wish I could have.

Then the mother laughed. It was a genuine laugh—you always know—full of delight. An open laugh. Uninhibited. From the heart. The best kind. It was a laugh prompted by I don’t know what, but I would think by something her husband said. Her laugh went right into me, charging me, instantly, with a heady dose of optimism. A couple. With two kids. Happy with each other, and the mom laughing. She looked so lovely.

“There are nice things in the world," Buddy tells Franny in J.D. Salinger’s Zooey, “and I mean nice things. We’re all such morons to get sidetracked.”

I could’ve watched them all day.

Finding inspiration in airports

When you travel by plane, you spend time, of course, in airports. That time can be expeditious, frustrating, wearying and, sometimes, a ball wrecker of plans. We all have stories.

There’s another side to that time spent in airports. It’s one of the few places where you can see, at least in larger airports, a cross section of humanity. And, if you’re not in a rush, where you can observe them closely.

I see all sorts. Single businessmen walking determinedly, speaking earnestly to their cell phones, saying the Most Important Things. College kids slouched in chairs wrapped in earphones, snacks strewn about, intently gazing at their phone screens.

A group traveling together all wearing the same unavoidable T-shirts.

And families.

I see young families. Some look breathtakingly young. They have one, two, three children, one of them maybe three weeks old. They have their retinue of carriages, tote bags, snacks, diaper bags and God knows what else, in that half-insane idea of flying from one place to another together.

I think back to the time when my wife and I had a young child, and a wave of nostalgia and protectiveness comes over me. It’s a small-smile moment for me, accompanied by wistfulness and thoughts of how rapidly time—yes, I’m in an airport—flies.

I remember what it’s like being a young parent. It takes a great deal of patience and teamwork to make this traveling with a family work. Sometimes the parents are not too good to one another; they’re perfunctory. That’s hard to see. But more often than not, the parents are good to each other. They’re a team.

The other day I was in the Dallas Airport on a layover on my way back home. Terminal C. Lots of travelers. I was seated at a table eating my Shake Shack burger looking at a young couple at the next table.

They had two kids. One was a little girl in a carriage. I didn’t see the other kid at first. Then the mother raised it up, a baby, hugged it, then held it high. She put the baby back and sat down across from a man who I assumed was her husband. They were both young. (What’s young? I hardly know anymore.) They were eating and talking about something and then pausing to talk to their older kid. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, even with discretionary straining. I wish I could have.

Then the mother laughed. It was a genuine laugh—you always know—full of delight. An open laugh. Uninhibited. From the heart. The best kind. It was a laugh prompted by I don’t know what, but I would think by something her husband said. Her laugh went right into me, charging me, instantly, with a heady dose of optimism. A couple. With two kids. Happy with each other, and the mom laughing. She looked so lovely.

“There are nice things in the world," Buddy tells Franny in J.D. Salinger’s Zooey, “and I mean nice things. We’re all such morons to get sidetracked.”

I could’ve watched them all day.

May 8, 2025

Rainy days in Paris

Paris in the rain is glorious, especially if the rain isn’t hard and unrelenting. My wife Gaywynn and I were in Paris, staying in the 16th arrondissement at our friend Philippe’s grand apartment in May. Philippe’s place is on the rue Raynouard, not far from the Seine, within walking distance of Trocadéro. We stayed a week. We stayed long enough so that we fell into a kind of domestic routine. That included shopping for food. It’s a lovely way to experience Paris, and we were grateful.

Some days it rained. It never stopped us.

Philippe walked us around his neighborhood, showed us where he shopped for food, greeting all the shop owners who clearly knew him. Later, we followed in his footsteps. We cooked a few meals for Philippe, and so we needed to buy food.

Where we were.

Where we were.We did our shopping mainly on the rue de l‘Annonciation, a narrow pedestrian street that flows into the broader, longer rue de Passy. We walked it many times, up and back, passing by all those shops and stores that truly sustain a neighborhood—butcher, produce, wine, bakery, seafood. Each is its own world, pulsing with tradition and high standards. Paris is a city of shops. (How many cities do you know still are?) They give you intimacy. They individualize you.

Rue de l’Annonciation. It became ours.

Rue de l’Annonciation. It became ours.Sometimes, we would eat at Aéro, a brasserie at the end of rue de l‘Annonciation on the Place de Passy, where we could sit outside. We came to think of it as our brasserie. That’s what happens when you stay for a while in Paris. You find a place to call your own. You make an attachment to it. It belongs to you, and you belong to it.

After a week, we belonged to our neighborhood and to Paris.

We bought meat at Les Bouchers Doubles at 43 rue de l’Annonciation. We bought vegetables at Marché Couvert de Passy. We bought pastries at Aux Merveilleux de Fred—yes, I know, “Fred” doesn’t sound French—and bread at Aux Pains de Manon, both on rue de l’Annonciation. Did any of the people behind the counters recognize us by the end of the week? I’d like to think, or to pretend, they did. They always smiled, in any case.

Les Bouchers Doubles themselves.

Les Bouchers Doubles themselves.

Marché Couvert de Passy. We bought artichokes there.

Marché Couvert de Passy. We bought artichokes there.

Aux Merveilleux de Fred. When school lets out, there’s an endless line.

Aux Merveilleux de Fred. When school lets out, there’s an endless line.Some days we went to Monoprix, a store I like very much. The name, Monoprox, is not very romantic. It’s a practical place, with a practical name, and I always feel practical shopping there. You don’t shop at Monoprix for souvenirs, but you do find things you need. For splendor, Gaywynn and I went to La Grande Épicerie de Paris on rue de Passy, where we found the best France has to offer. It was amazing to see what they considered exotic produce from America—they sold Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, for example.

The entrance to Monoprix. The name is in red.

The entrance to Monoprix. The name is in red.It rained several days while we were there. I never minded. I think rain brings out a stunning aspect of Paris. It makes the city moody, and me as well. I feel I’m a poet when I walk rainy Paris. Rain is disparaged too much, more than it should be. People talk about rain as if it were some kind of setback. It’s rain. That’s all. You can get wet. It’s all worth it when the rain is falling in Paris, and the gray light makes everything the best black and white film you’ve ever seen, and you smell the damp air and hear car tires hissing on the wet streets.

I think you can be a citizen of Paris by right of passion.

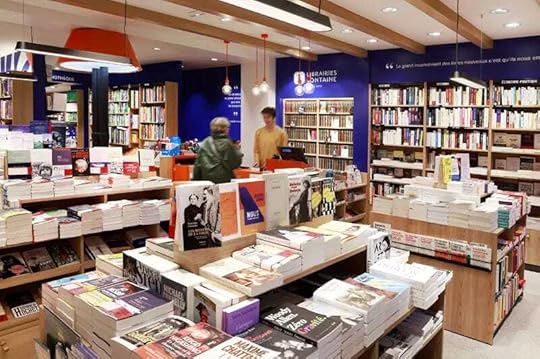

When it rained, we might dart into the Librairie Fontaine, a sweet bookstore on rue de l‘Annonciation. We discovered one of the young employees, who spoke flawless French, was American. I’d never heard any American speak French as well as he did. What I wouldn’t give to be able to work in a French bookstore! Well, here’s to reincarnation.

Inside Librairie Fontaine. All those marvelous books.

Inside Librairie Fontaine. All those marvelous books.I speak French passably. If a Parisian speaks, as they do sometimes, at the speed of light, then I’m lost. If the conversation is at a reasonable clip, though, and it’s just the two of us, I can manage. Speaking a language not your own and that you don’t speak fluently is a lesson in humility and error. But when you speak French in Paris and are understood, that’s a chest-rising feeling. So, I jump in. I never mind being clumsy. They’re not going to report me.

Returning after a long day on the Left Bank, we walked from our Métro station, Passy, up the long hill to rue de Passy. We didn’t have the climbing energy the students who disembarked with us had. Never mind. There was Desgranges bakery waiting at the top, on rue de Passy, with something weight-increasing, but God did it taste good. That gave us the motivation we needed.

Then home to rue Raynouard, into the small, slowly-rising elevator, off at our floor, inserting the key Philippe had given us, opening the door, throwing ourselves onto his couch, restoring ourselves, and then ready, in a while, to venture out again.

Our corner of Paris. It’s in our heart.

May 1, 2025

California

We went to California for a long weekend, visiting my cousin Beverly. She lives in Encinitas, which is about twenty-five miles north of San Diego.

I’ve been to California many times. Each time I come, I like what I see and experience. Despite what you may think about California—and we hear many things, a lot of them negative—I love it there. If you’re drawn to nature and to the natural world, this state is remarkable. It offers much. I can’t even scratch the surface.

The flowers and plants I see there are so unlikely that sometimes they seem dreamed up. Branches hang downward, like tresses. Bundles of buds leap out in a kind of wild ecstasy. The colors of the flowers are deep reds—a legion of reds—and purples and sun-like yellows, as if Matisse had mixed them. And so many grow on the sides of roads, lush and strong, overcoming the idea of sterility because of cars and traffic. You see unexpected hues in unlikely places. You get that in California. A ride to the post office can be a tour through a botanical garden.

Below are just a few of the flowers in my cousin’s yard. (Note: I used the iNaturalist app to identify them, because I couldn’t. So I can’t vouch for absolute accuracy.) All photos mine.

Ivy Geranium (Pelargonium pelatum)

Ivy Geranium (Pelargonium pelatum)

Tree Aeonium (Aeonium arboreum)

Tree Aeonium (Aeonium arboreum)

Fan Flowers (Scaevola aemula)

Fan Flowers (Scaevola aemula)The trees are dramatic. (I wasn’t even in Northern California where the titanic redwoods and sequoias grow.) I saw the rare Torrey pine (Pinus torreyana), which grows only in San Diego County and on Santa Rosa Island. I saw a Dragon Tree (Dracaena draco), with its giant, starfish-shaped seed cluster. These are imposing.

Dragon Tree.

Dragon Tree.Not to mention birds. Being on the west coast (I live in southwest Louisiana), I saw birds I wouldn’t otherwise see. I saw the Scaly-breasted Munia, a bird I’d never heard of before this trip. There it was at my cousin’s birdbath, flapping its wings, water flying everywhere. I also hadn’t seen, but did, a Black-necked Stilt, a Northern Rough-winged Swallow, a Spotted Towhee, Cassin’s Vireo and a Long-billed Curlew. I’m like a kid when I see a bird I’ve never seen before. I want to be like a kid.

Encinitas is near the ocean, so we went one day and walked the beach, which was restorative, as it always is. I grew up on the Atlantic Ocean, and though this is the Pacific, different in many ways, in basic presence and behavior there are so many similarities: vastness, the froth of waves, changing motions and complexions, ocean-y sounds, sand, briny air, shorebirds and seagulls, people walking the beach. I realize how much I miss it.

Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) with surfers in background.

Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) with surfers in background.The ocean is the great mother of us all. I feel a sense of belonging at the ocean. I am well aware that I’m not a fish, but I do feel an ancient pull, a sense of returning. When I watch turtles or seals being released at a beach and head, with urgency, to the water, part of me wants to join them. When I do go swimming in the ocean, those first steps in the water are familiar to me in some long ago way. The most atavistic part of me is returning home.

California is in peril. We know that. We watched the terrible fires in January. People seem to want you to acknowledge the negative aspects of a place or a situation. If you don’t, you’re considered untrustworthy. That’s insane. If I say a rose is beautiful am I required to mention its thorns? How many times do you need to be told about California’s earthquakes, fires and droughts, not to mention its traffic and smog? Being thrilled by beauty doesn’t make me—or anyone—naive. It makes you thrilled by beauty. Anywhere and everywhere we find beauty needs to be championed.

My five senses jolt awake here. I hear, smell, touch, taste and see startlingly pretty things here. I feel alive. That’s the essence of travel for me. I’m awakened. I’m alert. I’m engaged. My eyes are freshened. I feel more involved with the world. I learn. I grow.

Don’t think of it as a state. Think of it as a place. A place where nature flourishes.