The snows of yesteryear

It’s impossible to be certain you’re getting what’s essential in a poem by the 15th century French poet François Villon. As Galway Kinnell says in his introduction to his translation of Villon’s poems, Villon is toe-to-top in slang. That slang was already hard to decipher 100 years after Villon’s death. And here we are over 500 years later.

Villon, born in 1431, is one of these writers who had a hyper-romantic life that included being a thief and a killer, almost being hanged, imprisoned more than once and who, to enshrine his aura forever, vanished from recorded history in 1463, providing for freewheeling speculation as to his fate ever since. There have been movies, plays and novels created about him. But he isn’t, I don’t think, a poet most Americans are familiar with. I’m not sure what the French think of him.

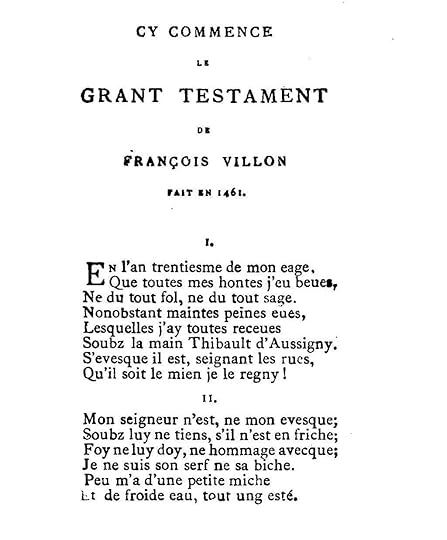

“Much of Villon’s popularity arises from sympathy for the difficult life he led,” the Poetry Foundation says, “which is described with both humor and poignancy and at great length in his largely autobiographical poetry.” His major work is Le Testament (“The Testament”), written in 1461. In it, he describes the hardships he endured, but with a sense of straightforward melancholy. He does hope his tormentors get their due, though.

The most famous line of Villon’s is “Mais ou sont les neiges d’antan?” It’s usually translated as, “But where are the snows of yesteryear?” This line, repeated at the end of stanzas in Villon’s poem, Ballade des dames du temps jadis, (Ballad of Ladies of Time Gone By), is about famous women in history (Héloïse, Joan of Arc) and their passing. “Where are the snows of yesteryear” has long emerged from that specific reference to signify the melancholy of death and loss that visits us all.

Tennessee Williams places the words, Ou sont les neiges, on a scrim at the beginning of The Glass Menagerie. He calls Glass Menagerie a memory play, which makes the Villon reference apt.

And who knew that these words could also be considered prophetic? With less snow everywhere.

Few poets I’ve read, in English or in translation, write about the loss of beauty and youth and the cold starkness of death as memorably as Villon. He’s the great poet of “Where have they gone?” So, now, age 79, when I think of my old friends, some of whom I haven’t seen in decades, I turn to François Villon’s words from The Testament in Kinnell’s translation:

Where are the happy young men

I hung out with in the old days

Who sang so well and spoke so well

So excellent in word and deed?

Some are stiffened in death

And of those there’s nothing left

May they find rest in paradise

And God save the ones who remain.

Villon, supposedly

Villon, supposedlyAll I can do is think of my friends from my youth—of Dud, Chris, Alex, Sandy, Rick, Bill, Monty and others. Some I’ve seen through the years. Some I see infrequently. Some I no longer see. One I can’t find. One died recently. And, yes, they sang so well and spoke so well. And they were happy. And they were excellent in word and deed. And God save them all.