Trần Tiễn Cao Đăng's Blog, page 2

May 14, 2025

On Translation

(basically what I talked about with students at a university a few days ago, in English)

(tóm gọn nội dung trao đổi với sinh viên một trường đại học vài hôm trước đây, bằng tiếng Anh)

***

I love this phrase beautifully expressed by one of my colleagues, “Hồn phách của tiếng Việt” “The soul of the Vietnamese Language”.

Speaking of “Hồn phách của tiếng Việt”, we’ll naturally think of the many accents, the distinct dialects, the rich expressions, the great poets, and the like. To these I’d like to add the fundamental grammar of Vietnamese language, which is largely different to that of English.

What I find deeply disturbing in my work as a translator and a linguistic instructor is the dire fact that a lot of Vietnamese, among them highly educated and competent professionals, do not have the much-needed mastery of Vietnamese, their native language.

When I ask my workshop attendees whether they know or have ever heard of the Topic - Comment structure, one of the most basic features of Vietnamese grammar, or else the verb serialization, yet another feature of this kind, the result is invariably like this: no more than one or two out of ten people can say ‘Yes’. And, mind you, some of these are professional translators, editors, copywriters, content writers, i.e. working in language-related fields, with at least some years of working experience.

One thing I know, as naturally as I know I am alive, is this: In order to be a good translator, you have to possess not only a mastery of the source language. You have also to possess a mastery of the target language, which, in this case, means your native language.

Fail to possess one of these and you will fall into one of the two fatal chasms of a translator: either you are unforgivably distant from the source material/the author, or you are shamefully alien to your target audience.

Speaking of the “fundamental grammar” of any language in general and Vietnamese in particular, we need some examples. Here one for you.

Whenever I open my mobile phone, I’m unpleasantly struck by the alienness of the notifications saying, for instance, “Đang mở điện thoại của bạn” (Opening your phone). What is the problem with this Vietnamese sentence? many may ask. Or, to put it more bluntly: Is there any problem at all? Yes, there is. A problem does exist here, only that it’s not recognized by so many, which is regrettable, taking into consideration the fact that they’re native Vietnamese speakers.

Let’s consider this phrase: “Tips on how to drive your car safely”. How can this be translated into Vietnamese? “Mẹo lái xe của bạn an toàn” or “Mẹo lái xe an toàn”? Ask this question to an ordinary Vietnamese, one of the vast “eighty percent consisting of non-English speaking Vietnamese people” and you will get an almost identical answer: “Why in the hell anyone can think of putting this stupid “của bạn” (“your”) into this simplest sentence?” The simple fact is, the Vietnamese language does not have, and hence does not use “possessive adjectives” in exactly the same way English does. The natural Vietnamese is “Mẹo lái xe an toàn”, which is literally translated into English as “Tips on how to drive car safely”. Note that none “your” is required. (It can be inferred from the context. Further information can be added in case it’s really necessary to differentiate whether it’s your own car or a borrowed/rented one).

Vietnamese does have specific means to indicate possession, of course, to avoid misunderstanding. For example:

“She combed her hair.” (her own hair)

=> “Cô chải tóc”. (literally: “She combed hair”. The fact that this hair belongs to her can be inferred from the context).

“She combed her hair.” (not her own hair but that of another person, her mother, for example)

=> “Cô chải (mái) tóc của bà” (Yes: “She combed her hair”, where “của bà/her” is used to refer to that another person mentioned earlier)

The same applies to “Đang mở điện thoại của bạn”. This is not how natural Vietnamese works. “Đang mở điện thoại” (lit. “Opening phone”) is good enough. The vast majority of Vietnamese out there, eighty percent of the total population, who are non-English speakers, they don’t speak that way in daily conversation.

This example, I hope, serves well to illustrate how a sound knowledge, or rather, a deep insight of the “inner workings” of our mother tongue is mandatory, if we are to become genuine experts in our language-related fields.

A writer well-versed in distant worlds and imagined lands should also be well-versed in his/her own mud-and-dirt country if he/she is to be a truly good author. A translator who is a virtuoso in foreign languages should also be a virtuoso in his/her native language. That’s the idea behind my translation workshops I have been conducting so far, which I call “Translation: from Hobby to Mastery”.

-----

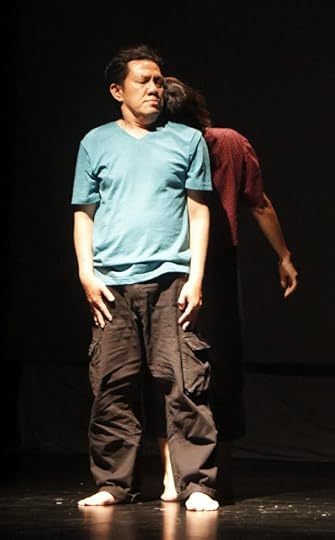

This photograph embodies the perilous situation of a "perfect" translator: She must exert all her efforts to find, and to sustain, an "impossible" balance based on the minuscule footing between the two opposite precipices: that of falling slave to the source text, and that of betraying the source in favor of the whimsical tastes of the audience—and of herself.

February 17, 2025

Nói về lý thuyết, hát về tình yêu

hay là

Hãy là chứng nhân tận tụy và thủy chung của cái đẹp.(tặng những ai đủ mạnh để vẫn tiếp tục tin vào tình yêu)

-----

(Một quán cà phê bình dân. Gần trưa, nắng dịu. B ngồi nơi một bàn ngoài trời, lơ đãng khuấy ly cà phê. A vào.)

A: A, chào bạn hiền, lâu quá không gặp. Đi một mình à? (không đợi mời, ngồi xuống ghế trống đối diện). Tôi ngồi cùng bàn được chứ, không quấy rầy anh phải không?

B: (mỉm cười) Không đâu.

A: Sao anh có vẻ ưu tư làm vậy?

B: Tôi nghĩ vơ vẩn thôi.

A: Anh bảo nghĩ vơ vẩn, nhưng biểu hiện của anh tố cáo là không phải. Anh nói thật đi. Anh biết là với người bạn như tôi, đôi khi anh có thể nói thật điều anh nghĩ.

B: (sau một lúc đắn đo) Thôi được. Tôi vừa gặp một cô gái.

A: Ha-ha-ha. Một cô gái khiến anh bạn ưa triết lý của tôi suy tư kịch liệt như đang suy tư về nguồn gốc của vũ trụ.

B: Nếu anh gặp cô ấy, anh sẽ không nói như vậy.

A: Chà, coi mòi nghiêm trọng thật đây. Tôi xin lỗi, tôi bộp chộp quá, xưa nay tôi vẫn thế. Thôi anh nói rõ hơn đi, để xem tôi có làm được gì giúp anh không.

B: (sau một hồi lặng dài) Cô ấy thật hoàn hảo.

A: Hẳn là hai chữ hoàn hảo không đủ.

B: Không.

A: Cô ấy đặc biệt?

B: Rất đặc biệt.

(sau một hồi lặng) Tôi không biết phải tả với anh ra sao. Thôi, tôi sẽ không tự nhận nhiệm vụ mô tả cô ấy với anh, vì chắc tôi sẽ thất bại. Tôi chỉ có thể nói rằng… (sau một hồi lặng nữa)… một phụ nữ như vậy, với khuôn mặt như Đức Mẹ Đồng trinh và thân hình Vệ Nữ hoàn hảo nhất, làm bên trong thân và tâm của ta diễn ra một cuộc xung đột kịch liệt.

A: Ha-ha-ha. Ra là vậy! Xung đột kịch liệt. Anh bạn triết gia - ca sĩ của tôi bị sét đánh rồi, một cú sét mang chữ ký của Đức Mẹ Đồng Trinh và Vệ Nữ nhưng trên thực tế là của quỷ. Ồ không, tôi đùa thôi, anh đừng để ý làm gì. (lấy lại giọng nghiêm trang) Tôi cũng rằng biết đâu đó trên đời có người như vậy tuy tôi từng chưa gặp. May là chưa gặp.

B: Phải, may cho anh.

A: Chẳng may cho anh. Anh không muốn mình chỉ là một gã mê đắm sắc dục, không hơn, khi ở trước mặt cô ấy.

B: Nói vậy không có nghĩa là tôi không mê đắm cô ấy.

A: Không mê đắm cô ấy thì không phải người bình thường, anh sẽ nói vậy chứ gì.

B: Tôi biết cô ấy biết tôi mê đắm cô ấy, song mặt khác cô ấy sẽ vui nếu thấy ở tôi không chỉ sự mê đắm. Tôi muốn trao cho cô ấy niềm vui đó… và cho cả tôi nữa. Cả hai chúng tôi sẽ vui hơn nếu giữa chúng tôi không chỉ có sức hút giữa những thể xác. Vẻ thuần khiết của cô ấy không chỉ là do đường nét khuôn mặt, nó là biểu lộ ra ngoài của sự thuần khiết tự bên trong. Cô ấy có những đòi hỏi cao về mặt tinh thần. Tâm hồn cô ấy lớn và sâu, tâm hồn đó không thể bằng lòng với những gì thô thiển, cạn cợt.

A: Sự đồng điệu về tâm hồn.

B: Cái gọi là đồng điệu về tâm hồn.

A: Cái đó sẽ quyết định liệu anh và cô ấy có phải là người sinh ra để cho nhau không.

B: Không phải. Cái đó sẽ quyết định liệu chúng tôi có phải là bạn của nhau không.

A: Chỉ bạn thôi?

B: Là bạn nhau. Bạn thực sự, có thể gọi là tri kỷ. Chừng đó là nhiều rồi.

A: Tình yêu thì không?

B: Không. Với tình yêu, đồng điệu về tâm hồn là không đủ. Anh biết điều đó mà.

A: Từng có không ít những mối tình phi biên giới, giữa những người rất chênh lệch nhau về tuổi tác, ngoại hình, tầng lớp xuất thân… Anh không tin rằng giữa cô ấy và anh cũng có thể có khả năng đó sao?

B: Có thể có một xác suất nào đó. Chỉ là nó hẳn rất nhỏ, và một khi nó rất nhỏ, ta không nên trông cậy vào nó, cũng như không nên trông cậy vào giải độc đắc từ tấm vé xổ số.

A: Anh tự ti quá.

B: Có lẽ một phần. Nhưng điều quan trọng là tôi biết rằng cô ấy, cũng như tôi, là típ người hướng đến cái hoàn hảo. Một người đàn ông đẹp cả bên ngoài lẫn bên trong, chân thành yêu thương cô ấy, đó là điều tốt lành nhất mà cô ấy muốn, và tự đáy lòng tôi mong cô ấy có được nó. Cô ấy xứng đáng như thế.

A: Nếu rốt cuộc cô ấy không tìm được thì sao?

B: Dù có nhiều điều không như ý, cô ấy vẫn sẽ tìm được hạnh phúc tại tâm. Cô ấy là người có phẩm chất tinh thần như thế, tôi biết.

A: Còn anh thì sao? Anh không muốn là người cô ấy sẽ chọn?

B: Nếu tôi bảo không thì tức là nói dối. Tuy nhiên, tôi không nói rằng tôi muốn; tôi chỉ mơ điều đó. Cũng giống như một người bị hội chứng phocomelia, sinh ra không có chân tay, sẽ không khỏi có những lúc mơ rằng mình có chân tay, kể cả dù anh ta đã quen với hoàn cảnh của mình và an lạc với nó. Mặt khác, chúng ta có thể yêu thương và bảo vệ cái gì đó quý giá với chúng ta bất kể nó có thuộc về chúng ta theo nghĩa hẹp hay không.

A: Anh nói cứ như một vị thánh.

B: Tôi là con người, không hơn. Giả sử có lúc nào đó tôi đang ở bên cô ấy và có những kẻ muốn xúc phạm cô ấy, thì bảo vệ cô ấy chẳng phải là việc mà một con người phải làm hay sao, bất kể cô ấy là vợ tôi, người yêu của tôi hay bạn tôi, đồng nghiệp của tôi? Dĩ nhiên là, nhìn tôi thế này, hẳn ai đó thấy buồn cười: tôi thì bảo vệ được cho ai? Nhưng khi chẳng còn ai khác cạnh cô ấy ngoài tôi ra, tôi sẽ làm tất cả những gì trong sức mình để bảo vệ cô ấy, kể cả dù phải mất mạng mình. Có thể là dù vậy tôi cũng không ngăn được kẻ xấu xúc phạm cô ấy, nhưng ít nhất tôi đã làm hết sức mình để bảo vệ một cái gì quý báu.

A: Sẽ rất ê chề nếu kể cả sau đó cô ta vẫn không yêu anh.

B: Tôi không làm vậy để cô ấy yêu tôi. Tôi làm vậy để thế giới vẫn tiếp tục có được cô ấy, được hưởng năng lượng tích cực từ vẻ đẹp của cô ấy, tâm hồn của cô ấy. Nhưng thôi, không cần đi sâu vào đó bởi đây chỉ là một giả thiết, không hơn. Ta nên dành thời gian cho những gì thiết thực, chẳng hạn như…

A: Chẳng hạn như buổi diễn tối nay! Trong lòng anh đang tràn đầy cảm xúc như vậy, anh có thể trút nó vào những bài hát.

B: Phải. Bình thường không phải lúc nào tôi cũng hát về tình yêu, nhưng tối nay tôi sẽ chỉ hát về tình yêu. Nãy giờ ta nói lý hơi nhiều. Lý luận cần lời, còn tình yêu, càng nói càng thừa, nên hát.

A: Tặng cho cô ấy.

B: Tặng cho cô ấy và tất cả những gì đẹp đẽ mà cô ấy là hiện thân, cho mọi cái đẹp dù lớn hay nhỏ trên trái đất.

A: Chẳng hạn anh sẽ hát bài gì?

B: “Lúng liếng”.

A: Dân ca quan họ?

B: “Mắt người lóng lánh như sao trên trời”. Một sự so sánh mà bây giờ nghe hơi sáo, nhưng cần nhớ rằng thời xưa nó không sáo. Được nhắc lại nhiều lần, nó trở thành sáo. Tôi muốn bằng giọng hát của mình trao lại cho mọi người vẻ đẹp nguyên tuyền của lối so sánh đó, “mắt người lóng lánh như sao”. Đó là sự thật, và nó đẹp.

A: Hy vọng người nghe sẽ cảm nhận được điều anh muốn truyền đạt. Bài gì nữa?

B: “Anh còn nợ em”.

A: Ha-ha-ha.

B: Sao anh cười?

A: Anh đã có gì với cô ấy đâu mà nợ cô ấy, nếu tôi không lầm.

B: Tôi không nợ cá nhân cô ấy, dĩ nhiên. Nhưng anh, tôi, tất cả chúng ta đều nợ thế giới này một cái gì đó, nợ những gì tốt đẹp đã không thành hiện thực. Chẳng hạn, tôi nợ người con gái Ấn Độ hai mươi bảy tuổi, bác sĩ thú y, bị bốn tên côn đồ hãm hiếp, giết hại, thiêu xác. Tôi nợ em tất cả những gì tốt đẹp mà lẽ ra có thể đến với em, tất cả những gì tốt đẹp mà lẽ ra em có thể mang lại cho thế giới. Tất cả chúng ta nợ thế giới những gì chúng ta chưa làm. Và, riêng cho cô ấy, thì đây không phải lời của bản thân tôi mà là lời của người đàn ông nào đó đã từng hoặc có thể sẽ có trong đời cô ấy, lời nhắc nhở rằng anh ta cần phải làm gì. Mặt khác, cũng có thể đúng là tôi nợ cô ấy. Tôi nợ cô ấy cái năng lượng tích cực từ vẻ đẹp toàn bích của cô ấy, nợ công sinh thành và dưỡng dục của song thân cô ấy, nợ sự huyền vi của Hóa công đã tạo nên cô ấy, và đến lượt mình tôi phải làm gì đó đẹp cho thế gian.

A: Sẽ chẳng mấy ai hiểu ý này của anh đâu.

B: Nếu cô ấy có nghe, cô ấy sẽ hiểu. Những người có tâm hồn như cô ấy sẽ hiểu.

A: Anh tự tin quá. Thôi bỏ qua. Còn bài gì nữa?

B: “O Sole mio,” “Mặt trời của tôi”.

A: Ồ, tôi thích bài đó, nhất là với giọng Pavarotti.

B: Tôi thì thích bài đó qua giọng của Andrea Bocelli hơn. Giọng Pavarotti hơi quá dày, quá mạnh, nghiêng về thuần túy phô trương. Giọng Bocelli có cảm xúc thật. Với những bài hát như thế này, cảm xúc quan trọng hơn.

A: Chắc anh ước gì mình hát được như Bocelli.

B: Và cố nhiên là không thể. Nhưng tôi sẽ hát bằng tất cả những gì mình có, bằng cảm xúc của mình. Người nghe sẽ cảm nhận được.

A: Hy vọng là với bài này thì họ cảm nhận được.

Hara Setsuko, một trong những phụ nữ đẹp nhất từng có mặt trên màn ảnh và trên thế gian.

Hara Setsuko, một trong những phụ nữ đẹp nhất từng có mặt trên màn ảnh và trên thế gian.B: “Đẹp biết bao nhiêu / Vầng mặt trời sau cơn bão / Nhưng còn đẹp hơn thế / Là khuôn mặt em.” Lời thật đẹp phải không? Trước khi hát tôi sẽ dịch lời bài hát cho mọi người. Thường tôi không làm vậy, nhưng đêm nay tôi làm. Và tôi sẽ nhắc cho mọi người rằng Bocelli bị khiếm thị từ nhỏ. Giả sử Bocelli hát bài này để tặng cho một phụ nữ cụ thể, ông ấy sẽ hát những lời này bằng trọn tâm hồn kể cả dù trên thực tế ông không thể thấy khuôn mặt cô ấy. Tôi sẽ nhắc người nghe, trước hết là nam giới, rằng chừng nào các bạn còn đôi mắt lành, các bạn đừng bao giờ bỏ sót vẻ đẹp của khuôn mặt người mình yêu. Sẽ có những lúc bạn là người duy nhất có mặt để chứng kiến cái đẹp ấy. Hãy là chứng nhân tận tụy và thủy chung của cái đẹp ấy.

February 14, 2025

Faínâhind-Arrobauth-Mattai (trích từ "Cospolist Nổi Loạn")

Một bản dịch tôi vừa mới hoàn thành:

"Faínâhind-Arrobauth-Mattai", một chương trong "Ngoại truyện Gurun" đi kèm với tiểu thuyết "Cospolist Nổi Loạn" sẽ xuất bản trong năm 2025.(Đây chỉ là bản dịch nháp, còn phải chỉnh sửa thêm)

-----

“That song from Shwevakenara, it mentions something like ‘girin stone’, right? How does it sound, Ăltâhind?” Faínâhind said, squinting at the warm, soft light emanating from the smoldering ember the colour resembling that of the rising sun.

“It goes like this, ma’am”, Ăltâhind said.

And she began to sing in a ringing metallic voice, with a more pronounced, sharper, silvery edge and a more subdued, softer, velvety one:

As I begin my song full of joie-de-vivre

From the yonder shore he gazes, struck with awe and passion,

His chest the colour of girin stone, so deeply azure.

Knows he me not, and yet all too well he knows

Who of us is the stronger.

Here Ăltâhind stopped, intuitively knowing at which point Faínâhind would like her to stop singing, in the same way as to which dimensions she would build her silence. And, amid the silence that stayed on after Ăltâhind’s last note, as its aftersound was going on vibrating the most fragile walls of human souls, Arrobauth began to speak in his calm, bone-dry voice.

“Your song sounds pretty good, in the Bongora tongue. And yet do you think it’ll shrink a bit if it’s forced into our Siră Kăntânări language at our command? Any Bongora song, I’m afraid, as soon as it’s converted into Siră Kăntânări, will have to reveal its true nature, which is to consist of too much fluid and fat and too few bones and muscles and sinews and blood. D’you think so, you the no-name from that land?”

From a farther, darker corner of the long carpet, Mattai calmly raised his head, not revealing on his face anything inside him, the face which had become a backdrop to the endless, intricate interweaving and transformation of the innumerable shades between brightness and darkness.

“My friend, Arrobauth, is someone with an ample pool of pride”, Faínâhind said. “With a pair of strained ears you can hear, in the heart of nocturnal silence, how the stars murmur among themselves in utmost reverence as they wait for him to decide the moment he’d go to bed. His blood flows much slower than yours, neither sluggishly nor listlessly, but in a dignified and elegant manner. Beware of him, Mattai”.

“Yes, the blood of ours, the people named Bongora, flows at a quicker pace than the Siră Kăntânări one does, and easier to spill out of our bodies”, Mattai said, slowly, deliberately, after a prolonged silence resembling that of “a ripe mango falling to the ground in the dead of night”. “The quicker our blood flows and the more it spills out of our bodies, the more profoundly we learn about the respect for life. You are right, my Highly-Revered Arrobauth. Typically, constantly, the Bongoran body lacks of blood; our blood stays outside our bodies as much as it does inside. We Bongorans, by nature, are much larger than you Siră Kăntânărins. We have this infinite universe which is our larger body; we reach out to the universe more than you do, for we feel the lack of that larger body more poignantly than you do. For you Siră Kăntânărins, you yourselves are large enough for you to contemplate and to feel self-sufficient. We Bongorans leave it to you. That’s not something for us”.

“You Bongorans are said to be a bit larger than your lot, which may be right”, Arrobauth said, sneering. “It does not strike me as strange that you are mentioned among the best story-fabricators on earth. The best thing you can do - your only pride, your sole and pathetic legacy - is to weave, from your imagination as untamed as a herd of wild horses, entirely unreal stories with no aim other than to entertain that throng of pitiably inferior, good-for-nothing types incapable of finding any more dignified way to fill their hollow years and empty selves. You know all too well that those powerful monarchs and rulers and aristocrats are excited by your stories, not by you. A princess falls hypnotised by the nightingale’s song, not by its excrements. What I like about pheasants is their hearts, not the mediocre seeds they consume so they can survive. We Siră Kăntânărins, we are different. Do I have to speak about that?’

A pause followed, and then Faínâhind said,

‘Listen, Mattai. I know all too well your riposte ability, which I admire. Do you think, however, that it’s better for you to sing rather than speak now? ‘One night of hearing your singing is worth more than ten years of conversation with you,’ thus goes one of your Bongorans’ sayings, as far as I remember”.

Taking a brief pause, she observed Mattai's momentary silence, perceiving an undercurrent of suppressed emotion pulsating within that quietude. Turning towards Arrobauth with composure and dignity, she then shifted her gaze to the others, raising her voice:

“Our Mattai knows better than anyone when a song of unrequited love deserves our attention more than the grandest martial epic. His most eloquent words always seem to know when to yield their place in the air and the human heart to the first birdsong at the break of dawn. Am I exaggerating a bit, Mattai?”

After a pause a bit longer than a couple of heartbeats, Mattai calmly said:

“All the best songs and most beautiful words on earth deserve being given form and birth even for a single reason, that of the presence of yours, Faínâhind. I would not hesitate to let all those songs and words flow through me on their return to you the same way all the rivers on earth return to the sea, if my time on earth permits. Thus are the workings of the universe. Within this grander scheme of the universe I am just a mud-covered river bed, the same way I am the realm of air through which the sea gives live force and inspiration to the rivers in the form of rains. The ones who sing those songs and say those words are nameless, invisible shadows without their own lives. There is no reason whatsoever for someone like me to be known and remembered, as High-Respected Arrobauth has said. There is no reason whatsoever for us to yearn for an eternal existence alongside that of the quintessence of soul residing inside us and flowing through us. We are blood vessels; the only reason for our existence contains in not allowing blood to spill over the grass.”

And, after a pause, he began to sing.

Ksbyámbâdŏrj-swénlig ăsshúpduven iryín,

Dolgöspāthnay féllâsargăn êrîvgálay íchten.

(...)

And please throw me a piece of bread -

O hot blood spills over moss and grass

And wild wind runs through ravines

And cold rain waters plateaus,

O-oh!

Just throw me a piece a bread.

During the silence that followed, Faínâhind calmly looked at Arrobauth.

Having clapped his hands three times, two of which slower, more leisured, the third one shorter, sharper, Arrobauth said:

“This song I’ve heard before. Yes, I like it a bit. Oh, I might be wrong. I might as well be speaking about another song, a song deemed different, albeit almost entirely similar to this one. In which ways is it similar? Let me think. Blood. Yes, of course. In the way it mentions blood. Words and notes and pitches that make you feel your own blood spill out of your body the same way dirty water flushes out of the drainage hole. That’s the quintessence of soul you mentioned, isn’t it, Mattai. The so-called quintessence that exists in numberless manifestations and permutations and yet always remains the same and gives itself solely to those eyes and ears capable of discerning and recognising it. You who know a myriad of apparently different songs, you can never convey anything other than that, right, you the noname from that land? The quintessence of soul of which you’re speaking with such hilarious and pathetic solemnity, it’s anything but abundant. And the whole of your talent, the whole of your mental power lies in showing this pitiable handful of quintessences in numerous, countless different forms, creating a deceitful illusion of a myriad-faceted, sophisticated world. You feed on the interest caused by this myriad-facetedness and sophisticatedness in the masses whose mind is no bigger than that of ducks and turkeys, you tell one thing and use all possible means to make it seem novel and, on the other hand, you hide, cover, silence the truth that it has been said before, no matter whether in different words or not. You cringe with terror at the thought that someone, upon hearing the words from your mouth, might feel these are something they’ve heard before, already known, or deeply familiar, even if they can’t quite recall when or how they came to know them”.

“Our Great Lord Arrobauth is renowned for being highly idealistic and demanding”, Faínâhind said. “To listen to a song, watch a play, or contemplate a painting, he uses his brain more than his ears, eyes, guts and heart. He judges and criticises before laughing and crying, instead of laughing and crying. That I admire, sometimes. That I like, sometimes. And now, you, Mattai, you ought to know better than I do what is best to be done at this moment. You who know well how to create another air, another realm that lasts for a short while, why don’t you do that right now? If not the blood that spills over the grass and the wind that I feel with the inner walls of my nose, then what?”

And then Mattai, with a light smile, began to sing.

A young girl prays to god:

Give me please the eyes of a dove

Give me please the eyes of a dove

Give me please the wings of a falcon

Give me please the wings of a falcon

So I can fly over the River Duna

So I can fly over the River Duna

And I can find a love for me

And then God gave her wings of a falcon.

And she found a boy that she loves.

And she found a boy that she loves.

After a prolonged pause, waiting until the last aftersound of the song dissolved in the world the way salt would dissolve in blood, Mattai said:

“So as to spare you any misunderstanding, Lord Arrobauth, I would like to assure that here is a song you have surely heard before, albeit perhaps through too many channels and passages and intermediate forms that now you can no longer recall its original source. This is a song titled ‘Malka Moma’ sung by a woman named Neli from a country called Bulgaria which lies in Terra, the world that, as they say, none of us have ever set foot in and never will and yet exists alongside us in every moment, every breath, like our own shadows cast into the depths of our very selves. Neli’s songs, as well as her own existence, are not unlike the first ray of sunlight, the first breeze, the first cloud of water mist in the world on the first day after it was born; by no way and in no future can we become like her and sing like her. It’s not because of this, however, that we don’t sing her through ourselves, don’t live her by means of our own lives. And when I begin with

When it is brought back, this apple

On a branch the bee hangs himself

And, leaning against this wall,

I weep.

just let him who hears this discern within it the echoes of something they’ve heard before, perhaps in another life or in a dream or in a dream within a dream; what is for someone else the echo or the aftersound or the silence that follows an aftersound is for us the pristine sound; the pristine voice of some part of the universe, yet another combination, occasional and inevitable, within the grand design of the Creator, the design according to which the pristine voice from someone can very well be the echo of something familiar to us, and yet there exists something much simpler than that: each of us is at the same time both the body and the shadow of ourselves and of each other, both the pristine voice and the echo of ourselves and of each other. Our job is nothing more than to give voice and shape to this inseparable interweaving of shadow and body, of pristine voice and echo. We are proud of our existence, our greatness being measured by the dimension of that endless interconnectedness between all things, unliving and living”.

Throughout the long silence that followed, all what could be heard was the crackling of something in the process of transformation within the carefully tended fire, and, alongside it, something else with a soundless voice that did not seek attention, a voice that, effortlessly and naturally, could be heard by the human soul.

Arrobauth said:

“One of my masters at the Börâkhon, Kărâdángy, would definitely accept you as His principle without putting you through any test as He had done with me”. He let out a short, dry laugh. “With that tongue of yours, sharpened and honed to perfection through decades of grueling practice under His guidance, you wouldn’t have needed more than a few words to turn a hero into a coward, a stalwart into a traitor, or a devout son into a despicable prodigal. And the other way round, of course. You are making me feel small and insignificant for I am lack of the capability to discern your Form inside me and my Form inside you. That capability you seem to possess, don’t you. I’m asking myself whether it is necessary to ask myself about that. That feeling of self-magnitude of yours, does it deserve a bit of my attention in my leisured time, you the noname from that land?”

Faínâhind’s hand-clappings, deliberately slow, with long, perfectly equal pauses, seemed to tear apart the dangerously taut, near-snapping silence.

Faínâhind said:

“My Arrobauth always treats the world cruelly, no matter how deeply he loves it—or, perhaps, precisely because he does. Poor Mattai! If you think Arrobauth does not cherish the songs flowing from your lips, or the souls that dwell within those songs, you are gravely mistaken. He knows this universe is vast enough to always open himself to welcome it, embrace it. If his disdain for you and your art ever cuts too deep, consider it as another face of love. Have you never known a man who scorns the woman he loves most? Can it truly be that the nature of love—of the romantic relationship between men and women—does not reach such heights of unpredictability? I do not believe such truths are not woven into your songs.”

After a short silence, Mattai said:

“What I feel in my heart towards Lord Arrobauth is not an expression of love, such a thing I have never said. I love him in the same way I love the beauty and power of a lightning as it spreads its magnificent and deathly branches across the sky. This one thing is etched deeply in the mind of storytellers, or rather, our minds are shaped by it: each act of creation is an act of love. No matter which what elements this love is mixed and hence how dissimilar it seems in comparison with love proper, if we accept it with an open and indiscriminative heart, which is at its core an act of love, then we’ll recognize it.

“Each time we sing a song and someone accepts it into her heart, then one more act of love is realised, accomplished. Each time such an act of love exists, we can feel it in our marrow, and we come to realise at this very moment the simplicity of the secret of existence: it’s the moment where death can be welcome with bliss and joy, in the same way life is. What we have just brought to life is sufficient for us not to hold on to life any more”.

“Yes, the whole of your life equals in cost precisely with the moment you make people shed tears, fall into daydreaming, or burst into laughing,” Arrobauth said, with a smile which he wanted others to perceive as merciful. This having been uttered, he intensely stared into Mattai’s eyes, calm and profound like the bottom of a closed bay. “All right”, after a short pause he said. “I’m going to clarify my point, so that you won’t misunderstand me with your narrow, tiny head.

“You know the story about Oglosméten and the magical or sinister playing of his instrument, don’t you? That, under the spell of his music, the souls of fallen heroes would appear and stand once more beside their living comrades and continue the endless battle against the enemies from the land of Kinka, enemies as powerful as God Himself? Now I have to tell you that I cannot bring myself to believe in such things. A reasonable man who builds his dignity on the basis of reason, I accept only those truths not hidden or hiding themselves from me. I’m telling you this so that you, someone perhaps more profound, though less informed, than I am, would not be faltered or enticed by the dark, deceiving aura of that story; instead you should concentrate on the sole essential point: To raise the dead, force them to stand again, and use them until they collapse once more—is it the best thing people like you are capable of doing? The soul of a woman who lived a thousand years ago, or that of a girl from Terra, the never-get-there world as you said, again it comes to life, throbbing, moving, captivating, driving you to tears. Yes. Very much so. In a blink of an eye. A blink of an eye which resonates with the eternity, as you said. Which is possible, I don’t deny. And yet, once this blink of an eye has ended, what is left are all the other moments which shape your real life, and you live your real life no matter there exists that particular moment or not. Is this not the truth? Ah yes, you can say whatever you can, in the most powerful, elegant, insightful manner of yours. And yet there exists one truth which you never say and which I do, and which nothing coming from you can ever reach or affect. Which is the following: For this world, the world where I reside, the world that exists for me and belongs to me, you and the like of you are nothing more than a bunch of inferiors specializing in entertaining the crowd by way of forcing the dead to reappear like the living and forcing people to accept these as true living. To create truly living things is something too far from of your reach. I consider my friends and peers no one less than those who work to pave each of the stones that make up the many roads linking the Empire and each of the finest buttons I caress with my fingers, who bring me the grapes which I put one after another into my mouth with full deliberation and in all solemnity, and who offer to me each of the arrows which I let go so lovingly from my bow, the arrow that shines and dazzles in the sun and heads toward the softest spot on a bird’s body into which it blissfully, hastily buries itself.

“Of course,” he says, raising one hand as if to forestall any objection even before it begins to form in someone’s mind, “I know, of course, that you—like others before you—will say that those songs of yours, as well as the tears, the laughter, the daydream, the turmoil, the torments caused in whomever happens to hear them, they are all the different faces and manifestations of a forgotten kingdom, a kingdom that has long lost its standing amid a world of trivial concerns and ephemeral pleasures. Oh yes, I know you all too well. I know you far better than what you could ever imagine, right? Ah I know you all too well, no matter how much I differ from you, or precisely because I differ from you that much. Ah, that’s what it all comes to: I despise you, knowing or not that you can also be more wealthy and profound than I am in some sense. Nothing is more natural and logical than that in the world we are in. To despise you and the like of you is one of the elements that make my essence, in the same way to run fast makes the essence of horses and to possess poison the essence of the tiny, lovely snake that you see lying coiled, doleful and sorrowful, in this jar of wine. Yeah, keep on saying, till your last breath if you like, about the universes that you and the like of you seem to be able to create and I don’t, the universes inhabited by those quasi-living or half-living or temporarily-made-alive-again of your making. To create a fake universe, it’s what you are born to do. What is it that I am born to do, you may ask. Let me tell you. The universe I am in, the real universe, I am having it in my hands, above me, under me, around me, inside me. It’s mine, this universe. It’s me, and you, one of the numberless petty things under my feet, you have no way whatsoever to affect me. Thus are the workings of the universe. You twist and turn, you wriggle, you thrash about in your cubbyhole, the most modest among the most modest ones, trying to give beauty and richness to this world in your way, according to how that brain of yours can ever perceive beauty and richness. Yeah, keep on doing that, man; that I allow you. That said, whenever I, Arrobauth, a citizen of the Siră Kăntânări Empire, speak to you about the place to which you and what you create are actually allotted in this world, then you must listen to me and understand precisely what I want you to. There exists a constant, insurmountable distance between you and I. No matter where you are, what you do, or sing, or say, or think, bear in mind that tiny cubbyhole, the only place you are permitted to stay.”

What followed was a short pause where everything that existed in the universe appears to have closed. And then, with a calmness that seemed to be a perfect mixture of a deep feeling of intimacy and a fine touch of sarcasm, Faínâhind said:

“Hey, Mattai. Where are your spirit and your tongue?”

“Tongue and spirit do not always go together, Lady Faínâhind,” Mattai said, in his calmness that never abated. “Who is it among us the one who has the right to assert, as an ultimate truth, that a rock that has existed from primordial times does not possess a spirit of itself? What I say is not as essential as what I think, this perhaps you understand. Is it not the truth that what I think is always infinitely greater, deeper, weightier than what I say? What I carry in my mind and heart is far heavier than what I carry in my stomach, yet only a handful like me truly grasp this. I have an only world in which I live, and yet within my head and my heart I carry hundreds and thousands of other worlds, they reside in me and in them dwell countless beings—people and animals, birds and fish, reptiles and insects, plants and herbs, to which those worlds I carry within myself are boundless, infinite. Thus, my body, mind, and soul are passages between the finite and the infinite. What is finite here is infinite there, and vice versa. Even if I die, the countless worlds within me do not cease to exist. Their passage through me may end, but they remain. They exist. Just look for another passage, and again they will open themselves for us in their entirety, primordial, intact. That is why we sing, we tell stories, handing over the songs and stories living inside us to those ready to receive and continue them and let them flow inside their bodies like blood and return once again to the infinite. Our profession is such that, as long as we are alive, as long as we still have a last drop of life inside us, we will continue to sing and tell about what is greater, better, finer than we are and to keep silent about ourselves. Yes, it’s the ethos of our profession: to have our say forever and to keep silent forever.

“And, on the other hand, there are moments when we must keep silent—because while we tell stories of our heroes and heroines, someone else may be telling stories about us. This storyteller, too, is human, shaped by a life of ups and downs much like our own. And so, it is entirely possible that one day, some misfortune may befall him, preventing him from continuing his stories about us and this would leave us in a state of both existence and nonexistence. That is why we persist in telling stories of our heroes and heroines: by doing so, we allow them to continue existing and keep their worlds from vanishing. And whenever one of us dies while in the midst of telling a story, another among us will take it up and continue it, ensuring it does not end: in this way, we fulfill our duty to those other worlds, keeping them within the realm of existence, and thus, when our time comes, we can depart with the quiet pride of knowing we have not lived in vain”.

He stopped. And then, from the bottom of the silence that was only infinitesimally punctured here and there by the cracklings of the woods being burned in the fire, rose Faínâhind’s voice, thin, vulnerable, trembling, not a bit resembling that of the ordinary Faínâhind, like the voice of a creature that has just returned from the other world, still unable to believe she’s now flesh and bone again and not only a bodyless soul.

“The infinitely remote realm that you said no one from us has ever set foot to, how is it called, Mattai?”

“That I cannot say for sure, o my beautiful Lady Faínâhind. There’s one thing I know, which is this: the place has a number of different names according to the different languages of the different peoples living there, one of them being Terra. It is one of the names most usually uttered from the lips of its inhabitants whenever they want to mention it, with love, nostalgia, pain, rage, or cold reason. Terra, or one of its many variants in several languages. Terre. Tierra. Tèra… Another name, even more often heard, is Earth. That world is as vast as ours, containing as many seas, rivers, mountains, forests, plains, ravines, deserts, and glaciers as ours does. There one can find many different countries exactly like here in our world, where numerous peoples vastly different from each other in sizes, appearances, temperaments, customs, and beliefs, exactly like here, in our world. And these people, no matter how hopelessly dissimilar from us they seem to be, in fact they are like us, very much like us. If such a person from Terra were ever to move to our world under some unknown circumstances, it’s entirely possible that someone from us would fall in love with him and be faithful to this love until her last breath, and vice versa. From this, countless wonderful songs and stories could be born. Alas, never can it happen. Terra is our shadow and we are its shadow. We cannot become our own shadow so as to fall in love with another shadow”.

“If it’s so,” Arrobauth said, trying to suppress a snicker, the hidden meaning of which eludes all efforts to fathom and discern, “what is the point of you going on about Terra? Letting our body be our body and our shadow our shadow, each secured in its allotted space and fate, is that not a better choice? Instead, why not take delight in contemplating this shadow, immersing yourself in it as if it were a dream you refuse to forget, and yet, at the same time, bear in mind that it is a world of shadows—shadows that are nothing more than apparitions, breezes, wisps of smoke, and, live to your last drop of blood, to your final breath, to the fullest of your being, in the real world—the only world that truly exists, the world of bodies, full of dirt and feces, and perhaps, fragrances as well. The world of Faínâhind. Of yours. Of mine. Are you capable of doing that? You do not sound like you are”.

“Those who cannot see, hear farther than those who can”, Mattai said, in a soft voice. “He who cannot stand on his own legs can make a fallen man pull himself and stand up with one word. Yes, it’s possible that we storytellers cannot stand on the face of earth as firmly as the workers who build roads for the Empire or the lumberjacks who fell down giant trees do—our bodies are not cut out for such tasks. And yet, with a pair of ears deep inside us and also countless miles away of us, we can hear someone in Terra tell stories about us, about no one else but us, thus making us more real to people living there, in that world. Whenever we keep a profound enough silence, we can hear our own silence there, in Terra. When, out of joy or wrath, we give forth a wholehearted scream, we can hear our own scream over there, Terra, not an echo but rather an alter ego of that scream. It’s then, and only then, we can fathom the truth that we live each of our moments here in order for us to live each of our moments there. Our body cannot get there, yet our spirit can. We tell stories about Terra in order to remind each of us of this truth, in the same way people from Terra tell stories about us. They and we exist alongside each other, live alongside each other through stories. The bodies and lives of ours, storytellers, are nothing more than the ends of the invisible threads connecting both sides. We cannot attach ourselves too tight to the visible lest we risk loosening the bonds between us and the invisible”.

Mattai stopped, and again the only sound that occupied the space and the human ears and hearts was the woods crackling in the fire. Several pairs of eyes were turned towards Arrobauth, who was sitting there engrossed in meditation. Faínâhind looked at him with infinite tenderness. If he ever looked back at her, he would realize that she had never looked at anyone with such tenderness, one that was boundless, infinite. He did not look at her, however. He seemed to see, through the warm flesh and blood of some living creature he loved, the blurred, elusive image of some remote dream returning to him, ephemeral, haunting, like a solitary chilling breeze in the burning heat of the driest summer. He seemed absorbed in some unusual sadness, “like the faint aura of a black star”. He who took a glance at Mattai at this moment would not fail to discern the unmeasurable softness with which he was looking at Arrobauth. It was as if Mattai was looking at his beloved blood brother who was going to kill him—he knew his brother was doing it without knowing what it was that he was doing. And the silence emanating from these two men—Arrobauth, lost in contemplation of something only he could see, and Mattai, contemplating something within Arrobauth that only he could perceive—was a silence that everyone knew they should not break, even though they could not fathom its essence.

@Trần Tiễn Cao Đăng

January 29, 2025

Khai bút đầu năm

Chỉnh lại một đoạn văn đã viết trước đây.

-----

And yes, it was how it all fell down upon me. Rain. Bucketfuls of rain. Downpour. Celestial torrents aiming at the core of the earth, the core of myself. Through my flesh, through my soul. Every cell of mine drenched and drowned, I stood, and then collapsed, sat, lay on the ground, reduced to nothing but one of the innumerable passages of rain (let’s call it rain, to give it a name, however arbitrary, for convenience).

And yet when it had all or almost all passed through this passage which had previously been me, I discovered something curious about it, this passage, myself.

There. Here. Within me.

A core.

A kernel.

As solid as diamond.

As weightless as light.

A free as a neutrino.

Immune to rain.

Immune to anything as raw as air.

Fresh like a new sprout.

An infant.

An infant aware of her own infancy, yet remaining an infant.

Ready for a new life.

For a new start, hopefully for something better, in this spoiled, rotten world.

I wait.

Patiently. Calmly.

Like one who, standing atop a mountain, waits for the sun to rise.

Like a hibernating bear waiting, subconsciously, for the warm weather to return.

I wait, for the night time.

December 20, 2024

Về 'Cospolist Nổi Loạn'

'Cospolist Nổi Loạn' sẽ phải đương đầu với rất nhiều trở ngại trên con đường đến với người đọc; đó là một điều có thể thấy trước, một điều đương nhiên. Nó là tiếng nói của một con người (mà do cơ duyên nào đó là người Việt Nam) hướng đến loài người trên khắp địa cầu; một con người (mà do cơ duyên nào đó sinh ra vào cuối thế kỷ 20) hướng đến loài người vài thế kỷ sau, nhiều thế kỷ sau. Với đất nước và thời đại nó sinh ra, nó là một sinh vật lạ, nói những điều không ai nói và gần như không ai hiểu, nghĩ những điều không ai nghĩ và gần như không ai hiểu. Phận của cuốn tiểu thuyết và phận của Cospolist Trungku, nhân vật chính, là phận của kẻ yêu loài người và không được loài người dung nạp, một kẻ không nhà, đau vì không thể làm gì hơn cho loài người ngày một băng hoại.

June 1, 2024

A Personal Manifesto: I Write to Define Myself

Something I wrote many years ago

A Personal Manifesto:

I write to define myself

(just for fun, "Ce n'est que pour rire, mesdames, messieurs...")

(Open) letter to the leaders of a(n) (imagined) Creative Writing Faculty at a(n) (imagined) (US-based?) University

(Draft, junk, improvised and (unbridled?) version)

To Whom It May Concern:

My name is Tran Tien Cao Dang (Tran is my last name, Dang my first name, Tien Cao my middle name).

I was born in 1965. I am working as an editor for the Vietnam-based online newspaper VietNamNet. I have published a short stories collection titled “Baroque and the Hidden Flower” (2005). As a translator, I have translated two books by some of the world's leading authors, namely, Milorad Pavic's “Dictionary of the Khazars”, and Haruki Murakami's “The Wind-up Bird Chronicle”. My latest translation, which will be published by the end of this year, is Kazuo Ishiguro's “Never Let Me Go”. I am now working on the translation of Franz Herbert’s “Dune”, one of the classic science fiction novels. My main foreign languages are English and Russian. I can read French, Spanish, Japanese, and a little Italian.

I am now working on a novel, my first one.

I am happy to write this letter to you on behalf of myself, a writer.

Why do I write?

I write to define myself, re-define myself, to regain my authentic identity, emancipating myself from the false identity imposed on me by others, the so-called mainstream, or what O. Pamuk refers to in his Nobel Lecture as the “center” of the world.

Vietnamese writers are so often thought of as being pre-ordained with a limited agenda to carry out throughout their writing life. This agenda consists of, namely: war, post-war conditions, totalitarianism, and, in a condescending goodwill action to allow for a picture of a somehow “full-fledge” culture, some exotic elements such as water puppets and Vietnam’s unique chèo or tuồng drama.

I’m too fed up with this faked destiny that is so unworthy to me.

What I am doing is to regain my authentic voice, develop it to its right power, and raise it to the right altitude, where it will be clearly heard and properly recognized by the world.

Here a sentence I read from an online document: “I was so consumed by reality to afford fantasy”. Well-said! I myself have for such a long time been “so consumed by reality to afford fantasy”, being caught in the trivial daily issues, but I’m now striving to get over it, to break through and lift myself to the point where I can take off with all the power of fantasy that has always been lying untapped inside me and the main, vital part of my so far unactualized self.

Now I know I can say the same as Pamuk did in his recent Nobel Lecture. For me, Vietnam is not any marginal part of the world. It is the center of the world. Similarly, we Vietnamese are not any Others to the rest of the world - implicitly, to the West. We are among the most authentic and qualified dwellers of the world. Here I live and write, creating, exploring, watching the growth of, and developing myself in, the entire multitude of imaginable and unimaginable worlds and realities.

These worlds are the territory where readers from all other corners of the world will not find an Otherness - a war-torn Vietnam, a post-colonial, totalitarianism-ridden Vietnam, an exotic, “unexplored” Vietnam, a “young tiger” Vietnam, you name it -, but rather another, strikingly alien yet disturbingly similar to their own world.

My project - my ongoing novel - is to create a multireality, multiuniverse version of what exists. The idea itself is far from “new” and unique, of course. The newness of the idea itself is not my concern. What essentially costs is the way the idea is developed and comes into full being, the way images, fantasies, emotions, passions, speculations, insights are added to it as bone, flesh, veins and blood are to a soul.

I am fully aware that many will find my future novel unsatisfying in the sense that it does not give a portray of Vietnam as they expected: no war atrocities, neither war victims nor war veterans, no retired generals, no bribing officials, no disappointed intellectuals, no would-be dissidents, no young people eagerly grasping the opportunities brought about by WTO and globalization.

This having been said, who knows, here and there in my novel this or that of all the abovementioned elements can be touched, yet it will be clear to readers that these are far from being what the novel is all about.

Here what I am doing: to discard any predetermined notion about the so-called Vietnam, to deconstruct any assumption of what a Vietnamese novel should be and should not be.

Anyone who couldn't imagine that a Vietnamese writer could afford to devote herself to, say, writing science fiction, will feel compelled to change his way of thinking as soon as he faces this kind of writing.

This kind of writing I am creating will partake in the workings of the world in such a way to adjust the common perception of one of its integral parts: in fact, I myself and Vietnamese writers like me are working to help change the world.

Naturally, it would be good for to me if I could attend a creative writing at your organization. It would be a good opportunity to me to see the world, physically. The world, which I know so intimately through words, sounds, and images, will present itself before me in all its mighty liveliness, infinite diversity, and rigorous beauty.

Of course, I’m not so stupid as to expect that such a trip will change my writing in a magical manner.

Instead, the trip would be, I think, one into larger dimensions of myself, one that would provide me with a deeper insight into the vaster realm which I would be able to partially fill with my own being.

In other words, this would help me strengthen the universal quality of my writing.

If, on the other hand, the trip would not be granted to me for this or that reason, I still have other, equally good ways to “attain the universal”, for, more than anyone else, I am fully aware of my free will and creative power.

The seed of something undefined and, although I’m barely aware of it at the present, much greater and better than me, has chosen to dwell within me, and it’s my responsibility to make it grow to the largest possible extent of its being.

Thanks for your kind(est) attention,

Tran Tien Cao Dang

April 3, 2024

Haiku verse around 'fork', 'hook' and 'heart'

And the day will come

When you wake up

With a fork that blossoms in your heart.

---

A fork slides

Along your mind

Until it meets its paradise

---

And earth and sky

Will look at your fork

As if at a thunder that severs the world.

---

A landslide, an avalanche

Are kept from moving down

By the hooks that are my eyes.

---

My hook keeps her

From disappearing

My fork draws her on a fog yet to come.

---

My body stinks

My hook radiates

My heart emits bright dark cries.

---

Of course it fits:

Your heart, your hits

The dream that twists you then quits.

---

Your heart, amid the fire,

Thinks it's a happy squire

Doesn't know it's a clown who burns himself.

---

Among the scattered ashes

Which had once been my heart

You can still find a splinter of smile.

---

The slips of your heart

The slides of your soul:

The knife and fork that slice you into songs.

March 29, 2024

India looks at me…

(A Brief Note on My Participation in the recent Dibrugarh UniversityInternational Literature Festival , Dibrugarh University, Assam, India,March 19-21, 2024)

-----

India looks at me withboth the stony, relentless stare of some local men from the poor neighbourhood alongthe Brahmaputra river and the open-hearted, pristine smiles of DibrugarhUniversity students. Each of the few days I spent here in this ‘remote’ part ofIndia, I felt myself hanging along the spider web-thin, razor blade-sharp, clear-cutand yet ever-shifting line that separates forces that weigh India down fromthose that pull her forward and upward.

Me staying at the luxuriousHM Resort had on one hand served as a superb protective shield against thenotorious Indian social violence and, on the other hand, encased me in a rigidetiquette framework out of which I always felt want to break free. I alwaysfelt drawn to the ‘real’ India behind these thick, transparent, impenetrablewalls of the luxury offered to me, the ‘real’ India that I felt bothintimidating and wonderful.

Mr. KrishnanSrinivasan, former State Secretary of India, told me he does not believe thatIndia has a future, the dire poverty and lack of education that ravage thegreat majority of its population being to be blamed. “It’s so sad”, he said. Hehas every reason to make this conclusion, of course, having been tormented bythis problem all his life. And yet, looking at the radiant faces of Dibrugarh Universitystudents and scholars turning toward us panelists and trying to answer theirwell-informed, ‘thorny’, highly inquisitive questions and having the honour toget to know their dreams, I’d want to be and remain a stubborn idealist who,despite all those bleakest signs and depressing indicators, keeps on believingthat this enormous country has every reason to believe she has a bright future.

A bright future, notonly for India but also for the whole world.

A lonely ‘old’ wolfwho would always prefer the harsh solitude within the privacy of his vastjungle of literature, I was not that ready to be in the company of suchwonderful representatives of my kind from around the world. I’m always aware,of course, of the fact that quite a few of members of my ‘tribe’ are scatteredall around the world. And yet, meeting them in their ‘real’ version, conversingwith them in the same physical room, and giving them the occasional tap ontheir shoulders, is something radically different from nurturing the company oftheir ‘incorporeal’ souls. Here I am, among them, and I feel that yes, I belongto a tribe, one of the not-that-numerous humans who see what many others don’tsee, think what many others don’t think, feel what many others don’t feel, andtry to do things that many others don’t do, out of a seemingly futile desire tomake the world a better, safer, and more tolerant place to live.

The mere fact thatwe’re all speaking about literature and spiritual values is ‘unusual’ initself: How could ever people like us, normally without any power, strive tooppose quite a large array of utterly real and huge powers that are doingnothing better than spoiling human souls and destroying Mother Earth? And yetwe go on speaking about how we can strive, about our paths, our efforts, ourdreams, our hopes: in a way, we are fighters who dedicate themselves to thecase of preserving humanity.

For this reason, noamount of gratitude would be enough to FOCAL and Dibrugarh University forcreating such an unforgettable event in my life, in our lives. May this spiritlive on forever.

Me speaking at the session, "The East European Tale", March 20, 2024, at Dibrugarh University, together with Halina Kruk (to the right) and Irena Karpa (to the left), both from Ukraine, and Ashes Gupta (far right) as the moderator.

Me speaking at the session, "The East European Tale", March 20, 2024, at Dibrugarh University, together with Halina Kruk (to the right) and Irena Karpa (to the left), both from Ukraine, and Ashes Gupta (far right) as the moderator.February 14, 2024

Về tình lãng mạn

Để làm nhân vật trong một mối tình lãng mạn, những “phẩm chất bên trong”, “vẻ đẹp tâm hồn”, “sự đồng điệu” không thôi, không đủ. Những thứ đó - “phẩm chất bên trong”, “vẻ đẹp tâm hồn”, “sự đồng điệu” - đủ cho một tình bạn đẹp, tình đồng chí, tình tri kỷ, tình yêu phi tính dục, phi giới tính. Đủ cho tình yêu lãng mạn thì không. Điều này không sao cả. Đơn giản là bạn không sinh ra cho vai đó -cũng như không phải ai cũng sinh ra để làm nhà leo núi, làm người mẫu nam, làm Bill Gate, làm Lionel Messi.

Khi đã ngộ ra điều này, bạn không mất thì giờ chờ đợi, đi tìm, xây dựng tình yêu lãng mạn. Thay vì vậy bạn biến con người mình, cuộc sống của mình, sự có mặt của mình trên trái đất thành chất liệu và nguyên liệu cho một tình yêu lớn, một tình yêu khởi đầu từ rác và tựu thành ở sự thấu cảm không phân biệt dành cho thế giới và mọi sinh thể. Mỗi người có vai của mình, giống như trong trận bóng đá. Có người mà vai trò chủ yếu hoặc duy nhất là tấn công. Có người mà vai trò chủ yếu hoặc duy nhất là bảo vệ. Cũng tốt nếu vai trò chủ yếu hoặc duy nhất của anh là, giống như thủ môn, không bon chen vào các cuộc tấn công (trừ vài trường hợp ngoại lệ), mà ở yên tại chỗ của mình, chuyên tâm bảo vệ những gì cần được bảo vệ.

Tình yêu lớn dành cho thế giới: đó là tình yêu duy nhất không làm bạn mệt mỏi chừng nào bạn còn sống.

Assol (Anastasya Vertinskaya) trong "Những cánh buồm đỏ thắm". Người đàn ông xứng đáng với nàng trước hết phải là người hùng mạnh, có đủ khả năng vật chất để cứu nàng khỏi số phận hẩm hiu.

Assol (Anastasya Vertinskaya) trong "Những cánh buồm đỏ thắm". Người đàn ông xứng đáng với nàng trước hết phải là người hùng mạnh, có đủ khả năng vật chất để cứu nàng khỏi số phận hẩm hiu.July 14, 2023

Kinh Thánh cho một người

Hãy đủ mạnh và đủ bao dung để là bạn tốt nhất của bản thân mi. Sao cho, khi mi gục ngã và không có ai bên cạnh, bản thân mi sẽ là bờ vai chắc chắn để mi tựa vào và cánh tay mạnh mẽ xốc mi đứng dậy. Sao cho, khi mi trở về nhà, với một niềm vui hoặc nỗi đau mà tim mi không chứa nổi, bản thân mi sẽ là người bạn với trái tim mênh mông thừa sức ôm trọn giùm mi niềm vui hoặc nỗi đau ấy. Sao cho, khi mi phạm lỗi lầm, bản thân mi sẽ là người tha thứ cho mi, không đay nghiến, không phán xét. Sao cho, khi mi sắp thở hơi cuối, bản thân mi sẽ là người nói với mi lời dịu dàng nhất mi từng được nghe trong đời, lời dịu dàng nó sẽ khiến mi thanh thản và yên vui đi sang thế giới bên kia.

-----

2

Hãy cho muôn loài và không mong được cho lại. Hãy giúp muôn loài và không mong được giúp lại. Hãy yêu muôn loài và không mong được yêu lại. Thỉnh thoảng, khi thật cần thiết, hãy dừng lại, tự cho mình, tự giúp mình, tự yêu mình, một cách vừa đủ, rồi tiếp tục cho, tiếp tục giúp, tiếp tục yêu. Hãy là một người trưởng thành giữa nhiều người chưa trưởng thành. Bản thân mình hãy là nguồn cho đi, nguồn giúp đỡ, nguồn yêu thương.

Trần Tiễn Cao Đăng's Blog

- Trần Tiễn Cao Đăng's profile

- 57 followers