Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 10

November 9, 2018

Wall Street Journal: What World War I taught the Clergy

This article was originally posted at Wall Street Journal.

The catastrophe of World War I, which ended 100 years ago Sunday, reshaped more than geopolitics. It also transformed a generation of Western Christians from holy crusaders into antiwar activists. This shift in thinking, coinciding with the rise of European fascism, contributed to the outbreak of World War II.

Religious leaders on both sides of the conflict demonized one another and conferred divine legitimacy on their war aims. In October 1914, German theologians endorsed a letter by prominent intellectuals that declared Kaiser Wilhelm II’s war policy a defensive necessity. In turn the Allies, backed by their national churches, characterized the German leader as “the Beast of Berlin.” London’s Bishop Arthur Winnington-Ingram said churches had a duty “to mobilize the nation for a holy war.” Germany, he argued, had abandoned Christianity for paganism. “The god the German leaders worship is an idol of the earth,” intoned G.A. Studdert Kennedy, one of Britain’s best-known chaplains: “a crude and cruel monster who lives on human blood.”

Although officially secular, the French government welcomed the crusading rhetoric of the Catholic clergy and helped lead the nation into a union sacrée. American Baptist leader Samuel Batten captured the apocalyptic mood when he called the war “a continuation of Christ’s sacrificial service for the redemption of the world.”

Four years of mechanized slaughter left the righteous crusade looking like an unholy debacle. With European democracy in tatters, a profound sense of disillusionment descended. The clergy were particularly affected.

By the early 1920s, churches on both sides of the Atlantic passed hundreds of resolutions renouncing war. Membership in peace societies exploded. In 1924 the Chicago Federation of Churches, representing 15 denominations, declared itself “unalterably opposed to war.” A nationwide poll found 60% of clergymen opposed any future war and nearly half vowed not to serve as wartime military chaplains.

The pacifist outlook culminated in the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact. Signatories, including the U.S., Germany, Japan and France, agreed to abandon war as a tool of national policy. Church leaders mobilized for passage. The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty in 1929. The Christian Century, liberal Protestantism’s leading journal, opined: “Today international war was banished from civilization.”

Yet within a decade, a series of political crises rendered the document moot. Japan invaded Manchuria, Mussolini marched into Ethiopia, and Hitler occupied the Rhineland and annexed Austria. Meanwhile in 1933, the University of Oxford’s debating society had decided overwhelmingly “that this House will under no circumstances fight for King and country.” Neither Britain nor France was in any mood to confront international aggression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt—with enthusiastic Christian support—signed the Neutrality Acts of 1935 and 1936, banning military aid to any nation in wartime.

When Hitler orchestrated the Munich Agreement in 1938—a desperate act of democratic appeasement that dismembered Czechoslovakia for a promise of peace—church leaders rejoiced. “The peace of Munich was possible,” Jesuit priest John LaFarge Jr. wrote in the Catholic journal America, “because of the habits and methods of peacemaking learned through two decades of international intercourse in the halls of the League of Nations.” Within a year Germany invaded Poland.

Throughout the 1930s Christian leaders played down the differences between Western democracies and the fascist regimes in Italy and Germany. When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Charles Clayton Morrison, editor of the Christian Century, denounced a potential Anglo-American alliance as “a war for imperialism.” Harry Emerson Fosdick, the popular social-gospel minister at New York’s Riverside Church, warned that American involvement in the war against Nazism would be “a colossal and futile disaster.”

Some Christian thinkers repented their pacifism as the Nazi blitzkrieg enveloped Europe. Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, on launching the magazine Christianity and Crisis, excoriated liberal churchmen for evading the problem of radical evil: “This utopianism contributed to the tardiness of the democracies in defending themselves against the perils of a new barbarism.” Christian apologist C.S. Lewis, who fought in France during the Great War, told a friend on the eve of World War II that “death would be much better than to live through another war.” Nevertheless, he saw no moral alternative in a world ravaged by the will to power.

“We know from the experience of the last twenty years,” Lewis wrote in 1944, “that a terrified and angry pacifism is one of the roads that lead to war.” It is a truth that bears repeating as the world reflects on the tragedy of World War I.

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

August 20, 2018

National Review: The Maker of Middle-earth, in Gorgeous Detail

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Oxford, England—After five months of ferocious and futile slaughter in “the Great War,” an Oxford undergraduate — knowing his deployment to the Western Front was inevitable — used his Christmas break in 1914 to cultivate his imagination. Twenty-two-year-old J. R. R. Tolkien began writing “The Story of Kullervo,” a heroic yet dark tale based on the Finnish saga The Kalevala. In May 1915, a year before he arrived in France as a second lieutenant in the British Expeditionary Force, he painted a watercolor, “The Shores of Faery,” which places Kor, the city of the Elves, at its center. Accompanying the painting, in his sketchbook, is a poem with the same name, describing Valinor, the “Undying Lands” that would form part of the landscape of his legendarium. Tolkien’s taste for fantasy, he explained, was “quickened to full life by war.”

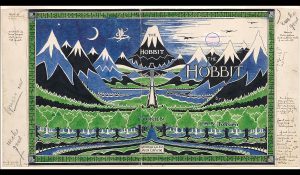

Such clues to the development of Tolkien’s creative imagination are beautifully assembled in “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth,” an exhibition by the Bodleian Library of Oxford University that represents the most thorough treatment of his life and work in decades. The collection includes draft manuscripts of his best-known works, such as The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, as well as fan letters, family photographs, and dozens of drawings, maps, and watercolors that Tolkien created to illustrate his stories.

Indeed, the numerous sketches and paintings in the Bodleian’s Weston Library, which is hosting the exhibition, will enlighten even longtime Tolkien fans about the intensely visual and artistic aspect of his creativity. For many years, Tolkien’s four children — John, Michael, Christopher, and Priscilla — were the recipients of his “Father Christmas” letters, which usually included images drawn with ink or watercolor. His invented stories for his children ultimately led to The Hobbit (1937), and he brought to the manuscript a series of artistic renderings to flesh out his vision. “I never could draw,” he wrote to his publisher with characteristic modesty, “and the half-baked intimations of it seem wholly to have left me.” Nevertheless, Tolkien produced dozens of drawings and watercolors, like the enchantingly pastoral “Hobbiton,” to help capture the forests and mountains and fields of Middle-earth.

The Bodleian’s Tolkien archivist, Catherine McIlwaine, has given the exhibition a tremendous vitality by placing Tolkien in the full context of his life: his role as son, scholar, tutor, author, husband, father, and friend. On display is a tattered portion of Tolkien’s 1926 prose translation of Beowulf, the Old English epic poem that he studied and taught for most of his professional life. He considered it the “greatest of the surviving works of ancient English poetic art,” and his college lectures on the poem drew large and enthusiastic audiences. “Dear Prof. Tolkien,” begins a 1941 letter from Betty Bond, one of Tolkien’s students. “Some of us among the home students would like to tell you how much we have enjoyed your ‘Beowulf’ lectures this term, and to thank you not only for enlightening but also entertaining us for two hours a week. We hope that we shall now be able to face the terrors of schools [examinations] as fearlessly as Beowulf met Grendel!”

Other letters in the collection capture moments of intense poignancy. “Dear Daddy, I am so glad I am coming back to see you it is such a long time since we came away from you,” the four-year-old Tolkien (with the help of his nurse) wrote to his father, then working in South Africa. “I hope the ship will bring us all safe back to you.” A telegram arrived the same day, bringing the news that Arthur Tolkien was seriously ill. He died the following day, February 15, 1896. A letter from Geoffrey Smith, one of Tolkien’s inner circle of school friends, hints at the experience of loss that would inform so much of his literary work. Smith, who arrived at the Western Front shortly before Tolkien, wrote him from France: “May God bless you my dear John Ronald and may you say the things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them, if such be my lot.” Smith was killed leading his men on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916.

One of Tolkien’s most famous tales is the love story of the mortal man, Beren, and the immortal Elf-maiden, Lúthien Tinúviel. He first told a version of the story in The Book of Lost Tales, which formed the basis for The Silmarillion. His hand-written manuscript begins thus:

Among the tales of sorrow and ruin that come down to us from the darkness of those days there are yet some that are fair in memory, in which amid weeping there is a sound of music . . . and under the shadow of death light that endureth.

As the exhibition explains, the legendary story of Beren and Lúthien was inspired by a true love story: the relationship between Tolkien and his wife, Edith, a marriage that endured for more than 60 years. A manuscript, written in Edith’s hand, forms the first chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, composed when Tolkien the soldier was recovering from trench fever. On Tolkien’s instructions, the names “Lúthien” and “Beren” are inscribed beneath their names on their shared headstone in Wovercote cemetery in north Oxford.

Implicit throughout the exhibition is Tolkien’s singular moral vision: a view of human life as both heroic and tragic. Here, it seems, is the motive force behind his astonishing creativity — an essentially Christian belief in the fall of man. In this, he was helped immeasurably by his circle of Oxford literary friends, the Inklings. All the members of the Inklings were professing Christians, and at the center of their weekly meetings was C.S. Lewis, another veteran of the Great War who became Tolkien’s closest friend for many years.

Lewis, also a lover of mythology and author of books such as The Chronicles of Narnia and The Screwtape Letters, was the first to challenge Tolkien to turn his private “hobbitry” into a published work. Tolkien confessed that he never would have completed The Lord of the Rings — a work twelve years in the making — without Lewis’s constant encouragement. “I have drained the rich cup and satisfied a long thirst,” Lewis wrote to Tolkien in 1949 after reading the story in manuscript. “So much of your whole life, so much of our joint life, so much of the war, so much that seemed to be slipping away . . . into the past, is now, in a sort, made permanent.”

Tolkien’s remarkable achievement was to use the genre of myth to reaffirm — against a culture of doubt and disillusionment — the “permanent things” about our lives, to engage his immense imaginative and artistic gifts to recover ancient truths about the human condition. Though often accused of escapism, no author in the 20th century expressed with greater power (as he once described it) “the beauty and mortality of the world.” The Bodleian exhibition richly tells the story of his quest: quickened while a soldier in the Great War; nurtured by his faith, family, and friendships; and deepened through sorrow and consolation. As Tolkien once described his great mythology: “It is written in my life blood.”

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

August 3, 2018

CNN: Pope Changes Death Penalty Doctrine

Last night I joined CNN’s SE Cupp to discuss Pope Francis’s new doctrine on the death penalty.

“I think this is a bombshell of historic proportions…This Pope comes along and says ‘no, they’ve all gotten it wrong and I’ve got it right.’” @secupp has @JosephLoconte explain why Pope Francis’ reversal on capital punishment is so significant. https://t.co/Rcx6xw8F6J

— HLN (@HLNTV) August 3, 2018

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

July 23, 2018

Weekly Standard: Chinese intimidation comes to Benedict Rogers’s mailbox

This article was originally posted at The Weekly Standard.

LONDON—If we needed more evidence of China’s deep insecurity about its communist rule, it could be found in a sleepy bedroom community outside London. On the day of my arrival recently at the home of Benedict Rogers, a leading British human rights advocate, I learned that my friend—along with his neighbors and his 77-year-old mother—had just received the latest of a series of anonymous letters attacking him for his criticism of China’s policy toward Hong Kong. The letters were postmarked from Hong Kong.

“In more than two decades of human rights advocacy work, including working on countries such as North Korea, Burma and issues such as radical Islamism in Pakistan and Indonesia,” Rogers told me, “this is the first time I have ever received letters of this kind or been subjected to this type of attempt at intimidation.”

When Great Britain transferred sovereignty of Hong Kong to China in 1997, Beijing agreed by treaty to respect the political and economic freedoms of the semi-autonomous city—the “one country-two systems” principle. Instead, China has orchestrated a campaign to erode Hong Kong’s civil liberties, prompting Rogers to launch Hong Kong Watch in 2017. He also has been a vocal critic of Beijing over its human-rights record. Last year, he was denied access to Hong Kong by immigration officials, ostensibly as a “threat to national security,” a claim echoed in the defamatory letters sent to his home. Two letters sent to his neighbors in Surrey instructed them to “keep an eye” on Rogers and included a photograph of him with the caption, “Watch him.” The letter to Rogers’s mother complained that he had “decided to take on a ‘crusade’ like attitude towards my country China and city Hong Kong,” and urged her to “talk some sense into him.”

Although Rogers says he doesn’t know the source of the anonymous correspondence, experienced observers from China and Hong Kong say that it is a common tactic of the Chinese regime. In October 2017, for example, a series of anonymous letters similar to those sent to Rogers and his neighbors were delivered to staff members at the Hong Kong Free Press, accusing them of spreading “hatred and dividing Hong Kong, China society.”

Rogers—like his mother, whom I have met—is not a wilting wallflower. As deputy chairman of the Conservative party’s Human Rights Commission, he has traveled extensively in China and southeast Asia and written widely about human rights abuses in the region. He told me that he established Hong Kong Watch because he believes that China is violating the terms of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, a legally binding treaty at the United Nations that safeguards the “rights and freedoms” of Hong Kong citizens. Those rights—which are not protected in communist mainland China—include freedom of speech, the press, assembly, association, private property, travel, choice of occupation, academic research, and religious belief.

“In recent years, China has completely disregarded its obligations under the Sino-British Joint Declaration, and trampled with increasing vigor on Hong Kong’s freedoms,” Rogers says. “Hong Kong is an international city, respected as the only city in China to have these freedoms based on the rule of law. It is therefore in all our interests to ensure that Hong Kong’s way of life is protected.”

Over the last several years, Beijing has become less tolerant of any signs of dissent across its territories, and President Xi Jinping has set the tone. “The party exercises overall leadership over all areas of endeavor in every part of the country,” Xi told delegates at a recent Communist party Congress meeting. No aspect of civil society, it seems, is beyond party control: All “socialist literature,” he explained, must extol “our party, our country, our people, and our heroes.”

Thus, five Hong Kong booksellers who went missing in 2015 turned up in the custody of mainland Chinese authorities. Control of all print media, including books, is now in the hands of the Communist party’s Central Propaganda Department. Also in 2015, the government targeted about 300 human rights lawyers, legal staff, and activists across 25 provinces, harassing, arresting, and detaining many of them for months. Earlier this year, China demanded that more than 30 international airlines, including some American carriers, delete from their websites any information suggesting that Taiwan, Macau, or Hong Kong are not part of China.

“It is increasingly clear that China is reaching well beyond its borders to silence critics, at the same time as becoming ever more repressive of dissent and debate within China,” Rogers explains. “Xi Jinping has presided over the worst deterioration in human rights in China since the Tiananmen massacre of 1989.” That’s no exaggeration.

Nevertheless, among Western political and economic leaders, the idea persists that the price of trade with China is silence on human rights. Some U.S. lawmakers have grown increasingly critical of China’s policies toward Hong Kong, including Rep. Chris Smith (R-N.J.), Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), and Sen. Ben Cardin (D-Md.), who introduced legislation authorizing “punitive measures” against government officials in Hong Kong or mainland China who are responsible for “suppressing basic freedoms in Hong Kong.” But the bill has yet to receive a hearing in either the House or Senate. In December, the Trump administration included on a sanctions list a Chinese police official it held accountable for the death of a rights activist, Cao Shunli, in 2014. However, the Washington-based Chinese Human Rights Defenders expressed “regret that the US Administration only named a low-level Chinese official.” The Washington Post reported in late June that Sam Brownback, the U.S. ambassador-at-large for religious freedom at the State Department, was urging the White House to punish Chinese officials cracking down on faith groups.

In the meantime, Beijing will continue to try to bully anyone—anywhere—who challenges its morally debased communist narrative. “If we do not act, to defend our values of democracy and human rights and to speak up for those who are repressed,” Rogers warns, “we will find China becoming ever more intrusive and invasive.”

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

July 9, 2018

Weekly Standard: Religion and the Renaissance

This article was originally posted at The Weekly Standard.

FLORENCE, Italy—If the inspiration for the highest ideals of the Western liberal tradition could be traced to a single city, it would be Florence: birthplace of the Renaissance and hotbed of radical individualism. The humanism of the Renaissance is either praised for shattering medieval superstitions or lamented for elevating the autonomous self against traditional religious authorities. Yet one of the most striking features of the period is the recovery of biblical concepts of human dignity and how they helped to unleash artistic, social, and intellectual genius.

The scientists who emerged during this period—some benefitting from Medici family patronage—saw no contradiction between pursuing knowledge about the physical world and pursuing the knowledge of God. Copernicus, Kepler, Newton, Galileo: each agreed that “the book of nature” was “written by the hand of God in the language of mathematics.” Against their critics, they saw their intellectual breakthroughs as contributing to a sacred mission. Newton once explained that his Principia (1687) had an apologetic purpose: “When I wrote my treatise about our System I had an eye upon such Principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity, and nothing can rejoice me more than to find it useful for that purpose.”

Renaissance artists like Michelangelo were driven by their love of beauty, an experience they connected intimately to God’s creative power. A contemporary biographer, Ascanio Condivi, wrote that Michelangelo “loved not only human beauty but universally every beautiful thing.” Though anxious not to make the human body an idol that blinded him to the need for repentance, Michelangelo would not abandon his longing for beauty to the stifling artistic conventions of his day. As he put it in one of his poems:

To what am I spurred by the power of a beautiful face?

Since there is nothing else in the world that brings me delight, to this:

to ascend while still alive among the blessed spirits by a

grace so great that every other seems inferior.

When Pope John Paul II in 1995 held mass in the Sistine Chapel to celebrate the restoration of Renaissance frescoes, he recalled Michelangelo’s achievement. “The frescoes that we contemplate here introduce us to the world of Revelation,” he said. “The truths of our faith speak to us here from all sides.” These artists, the pope explained, upheld a theology of the human body that celebrated the beauty of human beings created by God as male and female, suggesting the hope of a world transfigured by the risen Christ.

It is true that Renaissance humanists, in looking to ancient and classical sources for insight, often became enamored with pagan mythology. Some, like Pico della Mirandola, extolled the godlike potentialities of human beings as “the free and proud shaper” of their own destiny. Yet others, with a more chastened view of human nature, turned back to the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures: the Christian humanists such as Erasmus, who applied the new tools of classical scholarship to draw others into a deeper and more authentic knowledge of the Bible.

These biblical humanists emphasized individual moral responsibility and a program for reform based on the “philosophy of Christ.” By this they meant the obligation of every believer to understand and apply the teachings of Jesus in all realms of human experience: politics, economics, family life, and so on. “What else is this philosophy of Christ, which he himself calls being born again,” wrote Erasmus, “but renewal of a human nature well formed?”

For the Christian humanists, intimate knowledge of Scripture was the gateway to spiritual and social transformation. Risking church censure, Erasmus sought to have the Bible “translated into all languages” and “published as openly as possible.” In an age when holy writ was available only in Latin—and only to clerical elites—a more democratic approach to faith represented an appeal to the ethos of the ancient church. No wonder Martin Luther, as he launched his Protestant Reformation, called Erasmus “our ornament and our hope.”

Yet modern confusion about the Renaissance abounds. Liberals usually ignore the biblical assumptions that framed much of the scholastic and artistic genius of the period. Conservatives often attribute our modern woes to the supposedly unhinged individualism of the Renaissance spirit. But the Renaissance should be understood as a partial response to the moral turpitude of the medieval church: the crushing legalisms, inquisitions, heresy trials, and clerical hypocrisy.

Leonardo Da Vinci, the artist whose “Last Supper” ranks among the most famous of Christian paintings, also led the most exhaustive campaign of anatomical investigation ever attempted. Scholars believe that if his findings had been published in his lifetime, they probably would have altered the course of modern science. His discoveries, however, were based on secret dissections of dozens of human cadavers, a forbidden practice that invited execution.

“It is the business of little minds to shrink,” he wrote, “but they whose heart is firm, and whose conscience approves their conduct, will pursue their principles unto death.” Radical individualism? It was a similar defense of the rights of conscience—a commitment to pursue truth wherever it leads—that helped to bring the Christian church into existence.

In an age of skepticism, mediocrity, and moral indifference, we could use a few more radicals of the Renaissance type.

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

June 29, 2018

The Hill: When human rights are abused from all sides

This article was originally posted at The Hill.

In 1948, on the eve of the establishment of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Eleanor Roosevelt, campaigning for its adoption, warned her audience not to be deceived about the gravest threats to democracy and human rights in the post-war world. “We must not be deluded by the efforts of the forces of reaction to prostitute the great words of our free tradition,” she said, speaking at the Sorbonne, “and thereby to confuse the struggle.”

Roosevelt had in mind the Orwellian mischief of the Soviet Union, but attempts to compromise the concepts of freedom and human rights are alive and well today. Consider the Trump administration’s controversial immigration policy at the Mexican border: its flaws are manifest, but comparisons to the Nazi treatment of European Jews or the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II debase our moral vocabulary. Likewise, the White House decision to quit the politicized UN Human Rights Council — an organization essentially hijacked by autocratic regimes — is being denounced as a campaign “to undermine the human rights of all people everywhere, and their struggles for justice.”

Both the president and his critics could benefit from recalling Roosevelt’s leadership during a time of intensive disagreement over the meaning of human rights. Aware of her own country’s failure to uphold basic civil liberties for all its citizens, she nevertheless drew sharp distinctions between immovable totalitarian regimes and flawed democracies on the pathway to reform.

By 1948, the wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union to defeat Nazi German had shattered. Moscow had broken its promises to hold free elections in Eastern Europe, staged a blockade of West Berlin, and accused the United States of acting like a “fascizing” power by offering Marshal Plan assistance to Europe. Thus, the Cold War was in full swing when Eleanor Roosevelt, armed with the prestige of her husband’s legacy, assumed the chair of the newly established UN Human Rights Commission.

Roosevelt’s great task, in the aftermath of the atrocities committed during the Second World War, was to compose an international bill of rights that could win universal approval. She initially tried to charm the Russian delegates on the Commission with afternoon teas and dinner parties. But she quickly found herself embroiled in confrontations with the Russians over the rights of the individual vs. the interests of the State.

“We know the patterns of totalitarianism — the single political party, the control of schools, press, radio, the arts, the sciences, and the church to support autocratic authority,” she said. “These are the age-old patterns against which men have struggled for three thousand years. These are signs of reaction, retreat, and retrogression.” It was a brave and withering indictment: The communist government led by Joseph Stalin — whom her husband affectionately had called “Uncle Joe” — was just another installment in the historical catalogue of political despotisms.

Facing Soviet complaints of racism in American society, Roosevelt confessed that the United States struggled with “problems of discrimination,” but emphasized the potential for democratic reform. She pointed to the institutions of a free press, fair trials, freedom from arbitrary arrest, and freedom of religion and the rights of conscience as essential to a just society — rights that were categorically denied behind the Iron Curtain.

With the help of fellow commissioners such as Charles Malik, the Lebanese ambassador and an Arab Christian, Roosevelt secured overwhelming support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was adopted on December 10, 1948, during a UN General Assembly meeting in Paris, in a vote of 48-0, with eight abstentions. No less an achievement was Roosevelt’s repeated insistence that “the peace and security of mankind are dependent on mutual respect for the rights and freedoms of all.” By linking the promotion of democracy and human rights to international peace and security she helped to lay a new foundation for the conduct of American foreign policy in the second half of the twentieth century.

It is a lesson that needs serious attention in the age of Trump. Actions taken in the name of “national security” are no substitute for policies that are both prudent and humane. Stifling fundamental human rights — at home or abroad — can only weaken U.S. national security interests. Pretending that dictators and strongmen such as Kim Jong Un or Vladimir Putin are acting in the best interests of their people communicates American indifference to violations of human dignity.

At the same time, UN organizations such as the Human Rights Council must not be manipulated to shield thuggish regimes from censure. Thirteen years ago, I served on a Congressional Task Force on the United Nations that recommended the original Human Rights Commission be abolished and replaced by a Human Rights Council, “ideally consisting of democracies committed to upholding and promoting the highest standards in human rights.” No honest observer could claim that the existing human rights body is achieving that goal—or is anything close to what Eleanor Roosevelt had in mind.

“The propaganda we have witnessed in the recent past, like that we perceive in these days,” she said, “seeks to impugn, to undermine, and to destroy the liberty and independence of peoples.” Propaganda about human rights abounds. Only statesmen with moral clarity can cut through the fog.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

June 6, 2018

The Hill: On D-Day’s anniversary, Eisenhower reminds us of just war in action

This article was originally posted at The Hill.

On the eve of the Allied invasion at Normandy, June 6, 1944, the architect of the greatest amphibious assault in history drafted a handwritten note, to be delivered to the press if the campaign ended in disaster. “Our landings…have failed…and I have withdrawn the troops,” he wrote. “The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

The chief reason for the stunning success of D-Day was Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe. Writes biographer Stephen Ambrose: “Only his worries were infinite, only he carried the awesome burden of command.” And yet the story of Eisenhower’s capacity to shoulder the terrible burden of command has largely been left untold. Of all the forces that shaped Eisenhower’s approach to war — to his responsibility as a leader in wartime — the teachings of the Bible were decisive.

He was an unlikely war hero: the third son of David and Ida Eisenhower, common laborers from Abilene, Kan. Members of the Mennonites, they were pacifist in their politics and conservative in their Christianity. They communicated to their sons the old-fashioned virtues of honesty, ambition, integrity, and fear of God. Above all else, they gave Eisenhower a reverence for the Scriptures. “Our civilization is built upon its words,” he said. “It describes the condition of man and the promise of man with such power that, through many eras and generations, it has made the mighty humble and has strengthened the weak.”

Historians tend to disregard Eisenhower’s religious beliefs as political posturing. He once remarked that “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” But the remainder of the quote, uttered during the Cold War against Soviet communism, makes clear what he had in mind: “With us of course it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion that all men are created equal.” Eisenhower grasped intuitively the biblical taproot of American democracy.

He also believed that, even in wartime, democracy must not be defended by abandoning its central moral claim: the dignity and worth of every human soul. It is taken for granted today that the Allied forces attempted to wage a just war in Europe against the Nazis, not a brutal campaign of blind vengeance, of mass rape and mass executions. Whatever its excesses, the American-led military was not indifferent to the lives of soldiers and civilians. Moral cynicism was the defining feature of the Soviet military on the road to Berlin, not the Allied forces under Eisenhower.

To have advanced faster and further than the Russians into Eastern Europe, “it would have been necessary for the Western Allies to fight a very different and more ruthless war, at much higher cost in casualties,” writes historian Max Hastings. “Stalin and his marshals cared nothing for the preservation of civilian life or property… For all its commanders’ military sophistication, this was a barbarian army, which had achieved things such as only barbarians could.” It makes a difference if a nation’s military is led by individuals steeped in atheistic communism or rooted in the moral precepts of the Bible.

Biographers, however, often overlook a critical feature of Eisenhower’s approach as a military commander: the Christian assumptions that subordinated his ego to a noble cause. Unlike other successful generals, Eisenhower could never forget the individual human costs of war. Prior to D-Day, Ike spent many hours visiting troops in the field, because he wanted as many soldiers as possible to look into the face of the man ordering them into harm’s way. He was anxious to avoid “the unbearable burden of a conscience justly accusing me of the stupid, blind sacrifice of thousands of the flower of our youth.”

Probably no American general was more sober about the tragic nature of war. As Eisenhower put it in his farewell address as president, he had “witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war.” Nevertheless, he upheld the concept of the just war: the moral obligation to defend the innocent against the forces of evil. For Eisenhower, this became a personal obligation that could not be evaded, a truth he must have absorbed during the daily family Bible readings of his youth. “The only unforgivable sin in war,” he declared, “is not doing your duty.”

When Germany surrendered in May of 1945, Eisenhower was in command of more than three million American troops. An international hero, he was invited to give a speech in London, a victory celebration in Guildhall, where he would be honored with the Duke of Wellington’s sword. “I come from the very heart of America,” he said. “To preserve his freedom of worship, his equality before the law, his liberty to speak and act as he sees fit … a Londoner will fight. So will the citizen of Abilene.”

Here was a military leader who understood the political principles he felt called to defend. As he framed it in his war memoir: “We believe individual liberty, rooted in human dignity, is man’s greatest treasure.” Here was a commander of millions who submitted his own conscience to the moral demands of the Word of God. “To read the Bible,” he said, “is to take a trip to a fair land where the spirit is strengthened and faith renewed.”

Dwight Eisenhower made that trip many times during his military career, especially on D-Day. Throughout his life, Ike viewed the Bible as the Freedom Book: the basis for self-government, the bulwark against tyranny, and “the unique repository of eternal spiritual truths.” His great campaign, launched 74 years ago, helped to liberate a continent and to reassert these truths in the fog of war.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

May 15, 2018

National Review: Trump, North Korea, and the Reagan Doctrine

This article was originally posted at National Review.

On June 12 — 31 years to the day after Ronald Reagan stood at Germany’s Brandenburg Gate and called on Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall” — Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un will hold a historic summit in Singapore. The significance of the date should not be lost on anybody.

The speed with which relations between North Korea, South Korea, and the United States have improved — superficially, at least — is extraordinary. Only a few months ago, President Trump was warning Kim that the United States was prepared to rain down nuclear “fire and fury” on North Korea. The world seemed poised on the brink of war. Two weeks ago, however, Kim entered the world stage as the model of conviviality, embracing South Korea’s president, Moon Jae-min, at Panmunjom. For Trump, Kim went from being “rocket man” to “an honorable man.” The headlines might have read: “Rocket Man Lands on Moon.”

But euphoria and naïveté must be avoided. Indeed, wisdom and caution will be required, along with boldness and creativity, if the possibility of ending the state of war that has existed on the Korean peninsula for more than 50 years is to be seized. Likewise, if the opportunity presents itself to stop North Korea’s nuclear program — and even move towards denuclearization — it would be foolish to reject it. Olive branches, when offered, should generally be welcomed, not trampled underfoot. That was one of the lessons of the approach taken by Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and St. John Paul II in their dealings with the Soviets: From a position of strength, they responded to Gorbachev’s overtures with a generosity of spirit.

Yet there is one crucial aspect of Reagan’s Berlin Wall speech — and indeed the entire philosophy of Reagan, Thatcher, and John Paul II — that made them ultimately successful, and that so far appears to be missing from the North Korea narrative: placing the values of freedom, human dignity, and human rights at the heart of the conversation.

By virtually any measure, North Korea is the most closed and repressive society on earth. The United Nations has accused the regime of crimes against humanity that are “in a category of their own” and “without parallel.” In 2014, a UN Commission of Inquiry called for Kim Jong-un to be prosecuted at the International Criminal Court. At least 100,000 people languish in prison camps, subjected to slave labor, sexual violence, and torture. To be a Christian, to be found secretly worshipping or to possess a Bible, could earn you execution or a lifetime in a prison camp. Family members are routinely jailed for the political “crimes” of their relatives. Society is divided up and controlled by the “songbun” system of class structures, determined by political loyalty to the Kim regime. Any suspicion of insufficient loyalty to the ruling family can deny you access to employment, education, or health care. North Korea is the world’s ultimate Orwellian state.

Nevertheless, a recent report by Christian Solidarity Worldwide has found that, although the regime’s nature has not changed, the mindset of the North Korean people has shifted. The flow of information into the hermit kingdom — through radio broadcasts and the smuggling of DVDs and USBs containing South Korean soap operas — has created an awareness of the outside world. There is still no visible dissent, because to show dissent is to commit suicide, but within the privacy of people’s minds, discontent with the status quo is growing.

It is therefore essential, if the Singapore summit is to mean anything, that President Trump put human rights firmly on the table. He has no excuse not to, having met several North Korean escapees and invited one remarkable man, Ji Seon-ho, to the State of the Union address this year. As with the Helsinki process — which helped to open up the Soviet Union — human rights and international peace and security should be addressed together. For what peace can there be on the Korean peninsula if the terrible suffering of the North Korean people goes unchallenged?

It is worrisome that South Korea’s President Moon announced in advance of his meeting with Kim that human rights would be off the agenda. It is troubling that South Korea has not replaced the excellent Jung-hoon Lee as ambassador for human rights in North Korea, nor has it activated its foundation for North Korean human rights mandated by its own North Korea Human Rights Act. And there are warning signs that it is clamping down on the activities of Seoul-based human-rights groups focused on North Korea. Similarly, President Trump, 18 months into his administration, has not yet appointed a new special envoy for human rights in North Korea. Even more seriously, there is still no U.S. ambassador in Seoul. These gaps must be rectified urgently.

President Trump should read President Reagan’s Berlin Wall speech carefully and consider how to apply its principles to this new situation. Echoing President Reagan’s bracing challenge to Mr. Gorbachev, President Trump should deliver a clear message: “Mr. Kim Jong-un, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Korean peninsula, if you seek liberalization: Come to the prison camps! Mr. Kim, open the gates to the gulags! Mr. Kim, tear down the walls of the gulags! Mr. Kim, free all your political prisoners.”

The Brandenburg Gate symbolized a country divided physically and ideologically. Panmunjom is similar: a stark dividing line between an open, democratic, economically liberal and prosperous South Korea and the world’s most totalitarian, repressive, and closed country to the North. President Reagan described the dreary Berlin Wall that stood behind him as “part of a vast system of barriers that divides.” The armed guards, fences and “a gash of barbed wire, concrete, dog runs and guard towers” that divided Berlin describe North Korea today.

As Trump shakes Kim’s hand, he would do well to bear in mind the words of Ronald Reagan: “There stands before the entire world one great and inescapable conclusion: Freedom leads to prosperity. Freedom replaces the ancient hatreds . . . freedom is the victor . . . freedom and security go together, that the advance of human liberty can only strengthen the cause of world peace.”

Freedom can be the victor again. But in the interest of peace and in the cause of humanity, President Trump must find the moral courage to help make it so.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

April 16, 2018

National Review: C. S. Lewis and the Great War

This article was originally posted at National Review.

In the spring of 1918, Germany and the Central Powers staged a final massive offensive that threatened to overwhelm British and French forces along the Western Front. Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force in Europe, issued the order: “Every position must be held to the last man. . . . With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each man must fight to the end.”

One of the young soldiers with his back to the wall was Second Lieutenant Clive Staples Lewis. A confirmed atheist at the time, C. S. Lewis would survive the storm and steel of the First World War. But the experience of war would transform him, launching him on a spiritual journey that culminated, years later, in his conversion to Christianity. He would earn worldwide fame as a Christian apologist and author of a series of children’s books, The Chronicles of Narnia, which tell the story of “a great war . . . with all the world looking on,” a battle between the forces of Light and Darkness.

On the morning of April 15, 1918, however, Lewis was a long way from the religion of the Bible. His battalion, the Somerset Light Infantry, had come under German bombardment at the French village of Riez du Vinage. After five months in the trenches, he had had enough of war: “the frights, the cold, the smell of high explosive, the horribly smashed men still moving like half-crushed beetles.” His poetry during this period rails against a silent and indifferent universe: “Come let us curse our Master ere we die / For all our hopes in endless ruin lie.” Lewis might have joined the ranks of anti-war poets such as Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.

He might just as easily have been killed. A shell exploded nearby, obliterating his sergeant and wounding him with shrapnel. Lewis was dragged from the battlefield and taken to a hospital near Étaples. “I could sit down and cry over the whole business: and yet of course we have both much to be thankful for,” he wrote his father. “If I had not been wounded when I was, I should have gone through a terrible time.”

It was a terrible war, the most brutal and destructive conflict the world had ever seen. “When it was all over, Torture and Cannibalism were the only two expedients that the civilized, scientific, Christian States had been able to deny themselves,” wrote Winston Churchill, “and these were of doubtful utility.” On average, roughly 6,000 men were killed every day of the war. Before it was over, 9.5 million soldiers lay dead, millions more wounded. About half of the British soldiers fighting in France became a casualty of some sort. Lewis lost most of his closest friends in the final year of the conflict.

Yet the war and its aftermath seem to have stirred Lewis’s spiritual longings. On a train ride to a London hospital to recover from his wounds, he was seized by a sense of the transcendent as he beheld the natural beauty of the English countryside. “I think I never enjoyed anything so much as that scenery — all the white in the hedges, and the fields so full of buttercups that in the distance they seemed to be of solid gold,” he wrote a friend. “You see the conviction is gaining ground on me that after all Spirit does exist. I fancy that there is Something right outside time and place. . . . You see how frankly I admit that my views have changed.”

Nevertheless, Lewis insisted that he had no intention of “falling back into the most childish superstitions” of his youth. He was in good company. The mechanized butchery of the First World War instigated a mood of doubt and disillusionment among Europeans of all classes. For T. S. Eliot, the postwar world was a wasteland of despair. “I think we are in rats’ alley,” he wrote, “where the dead men lost their bones.” Erich Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1928) saw a generation of men “weary, broken, burnt out, rootless, and without hope.”

Yet, at Oxford University, where Lewis joined the faculty as a tutor in English literature, the Hound of Heaven seemed in hot pursuit. New friendships with scholars such as J. R .R. Tolkien — a veteran of the battle of the Somme and a devout Catholic — challenged his materialistic outlook. He read numerous works of philosophy and literature exploring the nature of God, myths, and the meaning of Christian atonement. “Now that I have found, and am still finding more and more of the element of truth in the old beliefs, I feel I cannot dismiss even their dreadful side so cavalierly,” Lewis admitted to a friend. “There must be something in it: only what?”

What Lewis found was something the Great War nearly destroyed for him: an explanation for his deepest longing, the desire for joy. What he discovered, from his own careful study of the gospels, helped him to cast off his doubts: a vision of God’s grace as well as his holiness. Here, in the life and teachings of Jesus, was “the only comfort” as well as “the supreme terror.”

Perhaps this was one of the lingering effects of Lewis’s experiences at the front. The grief and horror of combat was punctuated by acts of decency, compassion, and heroism. Lewis tasted the hatreds of war, but he also knew the intense camaraderie of soldiers under fire: the fears and friendships and loyalties of men caught up in a great conflict. He could not romanticize the concept of war — “we remember the trenches too well” — but neither did he reject war as an unmitigated evil.

Instead, the intimate experience of combat helped Lewis to imagine the mythical Narnia, a kingdom that bears the wounds — and the consolations — of a world at war. Its noble king, Aslan the Great Lion, is both a warrior and a peacemaker. “This is my real country!” Lewis wrote in The Last Battle. “This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now.”

Many others have made the same discovery. Lewis’s work, considered a children’s classic, has sold over 100 million copies and been translated into 46 languages. Not bad for an atheist in a foxhole.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

March 9, 2018

CNN: Pope Francis Losing Favor Among American Catholics

This video was originally posted at Vimeo.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

Joseph Loconte's Blog

- Joseph Loconte's profile

- 70 followers