Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 9

September 11, 2019

National Review: John Locke, Catholicism, and the American Founding

This article was originally posted at National Review.

In the summer of 1704, English philosopher John Locke began writing a response to a critic of his controversial treatise on religious freedom, A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689). It was, in fact, the third letter from Locke addressed to Jonas Proast, a chaplain at Oxford University, who insisted that government coercion in religious matters was necessary to preserve social order. Locke fired back: “Men in all religions have equally strong persuasion, and every one must judge for himself,” he wrote. “Nor can any one judge for another, and you last of all for the magistrate.”

Locke died before finishing the letter, but his revolutionary voice is being heard once again. A manuscript titled “Reasons for Tolerating Papists Equally with Others,” written in Locke’s hand in 1667 or 1668, has just been published for the first time, in The Historical Journal of Cambridge University Press. The document challenges the conventional view that Locke shared the anti-Catholicism of his fellow Protestants. Instead, it offers a glimpse into the radical quality of his political liberalism, which so influenced the First Amendment and the American Founding. “If all subjects should be equally countenanced, & imployed by the Prince,” he wrote, “the Papist[s] have an equall title.”

Here was a visionary conception of equal justice for all members of the commonwealth, regardless of religious belief — a principle rejected by every political regime in the world, until 1787 at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. “Locke was willing to contemplate the toleration of Catholics in a fashion which others would never countenance, and he did so with startling impartiality,” write independent scholar J. C. Walmsley and Cambridge University fellow Felix Waldman, who discovered the manuscript. “The tone is emollient, and nowhere replicated in Locke’s works.”

They have it half right. The attitude of English Protestants toward Catholicism in Locke’s day was shaped by over a century of religious conflict. To the Protestant mind, the advance of “Popery” and “priestcraft” represented a temporal and spiritual threat: ranks of religious believers loyal to a foreign potentate, blinded by superstition, hungry for arbitrary power, and latent with schemes of papal domination. Protestant sermons routinely identified the pope with the Antichrist. Locke’s career coincided with the Restoration (1660–88), when Catholics were excluded from public office and their rights of religious worship were severely restricted. By the 1660s, the rise of Catholic France under an absolute monarch, Louis XIV, instigated a fresh round of anti-Catholic fervor. In this acrimonious climate, Locke’s plea for political equality for Catholics was remarkably egalitarian.

Yet — contrary to Locke’s modern interpreters — it was consistent with his views about Catholics and other religious minorities throughout most of his political career. As an assistant to Sir Walter Vane, for example, Locke’s first diplomatic mission in 1665 took him to the Duchy of Cleves, in modern-day Germany. In one of his reports, Locke admits that

the Catholic religion is a different thing from what we believe in England. I have other thoughts of it than when I was in a place that is filled with prejudices, and things known only by hearsay. I have not met with so many good-natured people or so civil, as the Catholic priests, and I have received many courtesies from them, which I shall always gratefully acknowledge.

Locke also records his surprise at the social harmony between Calvinists, Lutherans, and Catholics, who each practiced their faith in relative freedom: “The distance in their churches gets not into their houses. . . . I cannot observe any quarrels or animosities amongst them upon the account of religion.” It was his first encounter with religious pluralism, and it left a deep and lasting impression.

In his first major treatise supporting religious liberty, An Essay Concerning Toleration (1667), Locke constructs an argument, a defense of the rights of conscience, that he will build upon for the rest of his life. He argues that magistrates have no right interfering in religious beliefs that pose no obvious threat to the social order: “In speculations & religious worship every man hath a perfect uncontrolled liberty, which he may freely use without or contrary to the magistrate’s command.” The challenge of accommodating different religious traditions, including Roman Catholicism, is front and center. “If I observe the Friday with the Mahumetan, or the Saturday with the Jew, or the Sunday with the Christian, . . . whether I worship God in the various & pompous ceremonies of the papists, or in the plainer way of the Calvinists,” he wrote, “I see no thing in any of these, if they be done sincerely & out of conscience, that can of itself make me, either the worse subject to my prince, or worse neighbor to my fellow subject.”

It was an extraordinary claim for an Englishman of his era: that Catholics, Calvinists, Jews, and Muslims alike could all be good citizens and good neighbors. Twenty years later, in the throes of another season of anti-Catholic anxiety, Locke delivers the same argument, yet even more forcefully.

In A Letter Concerning Toleration — now considered foundational to the Western canon — Locke insists that the equal protection of civil rights for all religious groups is “agreeable to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and to the genuine reason of mankind.” He uses Catholicism as a test case for explaining why religious doctrines should be of no concern to the magistrate: “If a Roman Catholic believe that to be really the body of Christ, which another man calls bread, he does no injury thereby to his neighbor.” Locke applies his argument not only to Catholics but to the most despised religious minorities of 17th-century Europe. The best way to safeguard the rights of conscience, he concludes, is “to distinguish exactly the business of civil government from that of religion.” The American Founders took note.

Nevertheless, Locke has his critics. Political progressives find his religious outlook — he considered the pursuit of God’s gift of salvation the “highest obligation” facing every human being — outdated and offensive. Many conservatives are also ambivalent or even hostile. Catholic thinkers such as R. R. Reno, editor of First Things, not only take Locke’s anti-Catholicism for granted, they view it as evidence of animus toward biblical religion, underwritten by a contempt for the sources of “traditional authority.” In Why Liberalism Failed, Notre Dame’s Patrick Deneen faults Lockean liberalism for “the destruction of social norms” and the “untrammeled expansion of private identity.” Others, such as Yoram Hazony, in The Virtue of Nationalism, denounce Locke’s entire approach to politics as “a far-reaching depreciation of the most basic bonds that hold society together.”

We are entitled to wonder whether these critics have the slightest idea of the actual political and cultural catastrophe that had engulfed Western society when Locke made his most famous arguments for human liberty. The sources of “traditional authority” wistfully recalled by these writers — the state churches and social hierarchies of European society — had transformed much of Europe into a violent, sectarian battlefield. Under the banner of the cross of Christ, the “basic bonds that hold society together” — such as compassion, forgiveness, and mutual respect — were being shredded without a twinge of conscience.

It was Locke’s moral outrage over the widespread abuse of power, reaching another crescendo in the 1680s, that drove him to compose his Two Treatises of Government (1689) and A Letter Concerning Toleration. English society was in crisis: riven by a brutal crackdown on religious dissent, by the return of political absolutism, and by the growing threat of militant Catholicism. “The idea of a Counter-Reformation design against English Protestantism was far from absurd,” writes historian John Coffey, “and we should resist the temptation to treat Protestant fear as irrational paranoia.” The Dutch Republic, where Locke was living in political exile, was absorbing thousands of religious refugees fleeing Catholic France. The reason: On Oct. 22, 1685 — a few weeks before Locke began composing his Letter — Louis XIV invalidated the Edict of Nantes. France’s brief experiment in religious toleration of its Protestant (Huguenot) population had come to an end.

And a bloody end at that. At least 200,000 Protestants fled in the first wave of persecution. Locke met and befriended many of them. It would have been impossible to ignore the reports of Protestant children taken from their parents, of churches demolished, of ministers beaten, imprisoned, or executed because of their faith. Princeton historian Jonathan Israel describes the mounting Catholic–Protestant tensions thus: “The resurgence of anti-Catholic sentiment, in reaction to the persecution of the Huguenots in France, pervaded the entire religious and intellectual climate of the Republic.”

Despite all of this, Locke defends the civil and religious rights of Catholics in his Letter, as part of a broader argument for freedom of conscience. “I will not undertake to represent how happy and how great would be the fruit, both in church and state, if the pulpits everywhere sounded with this doctrine of peace and toleration.” It is a curious doctrine coming from a man supposedly hobbled by anti-Catholic bigotry.

Why, then, do Locke’s critics conclude that he opposed equal protections for Catholics in the commonwealth? Because in his Letter and other writings, Locke objects to tolerating those who teach that “faith is not to be kept with heretics” or that “kings excommunicated forfeit their crowns and kingdoms.” Such views were a matter of Catholic policy, and it seems clear that Catholic leaders were the chief subjects in Locke’s mind.

Yet Locke makes a crucial distinction between Catholics who pledged loyalty to the political regime under which they lived and those who sought its overthrow — a fifth column “ready upon any occasion to seize the government.” Locke’s detractors fail to acknowledge the machinations of the Catholic Church, in England and elsewhere, in which the Holy See acted to destabilize political authorities or condemn them as heretics and see them toppled. What Locke found intolerable was not Catholic theology per se but rather the agents of political subversion operating under the guise of religious obedience. As he put it in the newly discovered manuscript: “It is not the difference of their opinion in religion, or of their ceremonys in worship; but their dangerous & factious tenets in reference to the state . . . that exclude them from the benefit of toleration.” On this point, Locke could be as tough on Protestants as he was on Catholics.

Today we take political stability and civil order for granted; we do not exist in fear of sectarian forces sweeping away our liberties. But no one living in Locke’s tumultuous times enjoyed this luxury. Some ideas threatened the moral taproot of civil society; they could not be tolerated. In Locke’s world — as in ours — the constitution must not become a suicide pact. Political philosopher Greg Forster insightfully observes that Locke “towers over the history of liberalism precisely because virtually everything he wrote was directed at coping with the problem that gave birth to liberalism — religious violence and moral discord.”

Such is the world as we find it. If prejudice taints Locke’s political legacy, perhaps it is the prejudice of those who prefer false and comforting narratives to difficult moral and historical realities. Locke’s critics have blinded themselves to the bracing nature of his democratic vision: “But those whose doctrine is peaceable, and whose manners are pure and blameless, ought to be upon equal terms with their fellow-subjects.” Here is the only tenable solution to the challenge of religious diversity: equal justice under the law for people of all faith traditions.

No political doctrine has been more integral to the success of the United States, for no nation has been so determined to regard religious pluralism as a source of cultural strength. America’s experiment in human liberty and equality is profoundly Lockean. It is also, in some important respects, deeply Christian. Locke believed that the gospel message of divine mercy — intended for all — implied political liberalism. The founder of Christianity, he wrote, “opened the kingdom of heaven to all equally, who believed in him, without any the least distinction of nation, blood, profession, or religion.”

It would be hard to conceive of a better doctrine on which to build a more just and humane society. A revival of Lockean liberalism would do much to tame the hatreds now afflicting the soul of the West.

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

September 3, 2019

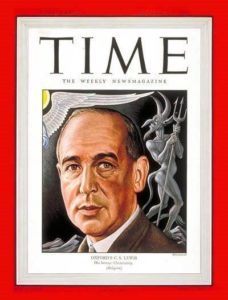

National Review: Oxford Don vs. the Devil

This article was originally posted at National Review.

‘The lecturer, a short, thickset man with a ruddy face and a big voice, was coming to the end of his talk.” That was the opening sentence of the Time magazine cover story for September 8, 1947. The subject of the story, who swiftly exited the classroom for the nearest pub, was the Oxford University don and best-selling author Clive Staples Lewis. How did a scholar of medieval literature, with no formal theological training — a strident atheist in his youth — become, in the words of Time, “one of the most influential spokesmen for Christianity in the English-speaking world”?

This is one of the questions taken up by James Como in C. S. Lewis: A Very Short Introduction, a recent title in the Oxford University Press series of compact introductions to wide-ranging topics. Como’s unlikely achievement is to deliver a brief (under 200 pages) yet compelling literary survey of Lewis’s works, which include over 40 books, 200 essays, 150 poems, short stories, a diary, and three volumes of letters. I can think of only a handful of authors qualified to take on such a project, and Como is among them. A professor emeritus of rhetoric at York College (CUNY), a founding member of the New York C. S. Lewis Society, and the author of Branches to Heaven: The Geniuses of C. S. Lewis (1998), he is a leading Lewis scholar.

Nevertheless, the task is daunting. Lewis’s writings — his fantasy, science fiction, apologetics, and theological essays — were as diverse as his public personae. He excelled in his roles as a university lecturer, literary historian, broadcaster, debater, preacher, and public intellectual. His series of children’s books, The Chronicles of Narnia, has sold over 100 million copies in over 40 languages. Though he was a lifelong Protestant (Anglican), his works could be found at the bedside of Pope John Paul II. Como puts it nicely: “Withal it is easy to lose sight of just how complex, productive, influential, charismatic, and steadfast this portly, rumpled man was.”

Indeed, Lewis was a force of nature — and, we are entitled to suspect, of something beyond nature. As Como notes, Lewis’s first published writing was a collection of poetry, Spirits in Bondage (1919), a work he began when he was serving with the British Army in France during the Great War and which bears the imprint of the soldier turned cynic:

Come let us curse our Master ere we die,

For all our hopes in endless ruin lie.

The good is dead. Let us curse God most High . . .

We built us joyful cities, strong and fair,

Knowledge we sought and gathered wisdom rare,

And all this time you laughed upon our care . . .

Lewis’s diary, All My Road Before Me (1922–27), offers clues about what lured him away from his egoism and materialism. The last line of the diary reads, “Is there never to be any peace or comfort?” He would find both in the teachings of the Bible. But only with the help of many Christian authors and friends — including George MacDonald, G. K. Chesterton, Owen Barfield, and J. R. R. Tolkien — did Lewis overcome his fierce doubts and embrace the Christian faith. Explains Como: “The great value of his diary is this: it shows us the man Lewis converted from, and the reader is relieved to be done with it.”

What offended and confounded many of Lewis’s peers at Oxford was his supernaturalism: an unapologetic belief in the traditional Christian doctrines of heaven and hell and in Jesus as the incarnate Son of God. The concepts are embedded in his science-fiction mythology, The Space Trilogy. The series begins with Out of the Silent Planet (1938), which traces the adventures of Dr. Elwin Ransom, a Cambridge philologist who battles the forces of evil that have turned earth into a quarantined and “silent” planet in the cosmos.

As Como reminds us, the sin of pride, and its fatal consequences, lie near the center of the story. Ransom travels to Melacandra (Mars), a planet with a benevolent guardian spirit, the Oyarsa, who presides over creatures untouched by sin. To the inhabitants Ransom tries to explain earth’s history of hatred, war, slavery, and oppression.

“It is because they have no Oyarsa,” said one of the pupils.

“It is because every one of them wants to be a little Oyarsa himself,” said Augray.

Ransom’s adventures continue in Perelandra (1943) and That Hideous Strength (1945), in which the malignant powers of perverted science endanger the entire human race. “Finally we understand what is at stake,” Como writes. “Earth may be one small part of a larger design, yet the reader sees with fresh eyes the enormity of the Fall and the magnitude of the forces that range both against us and for us.”

Walter Hooper, Lewis’s personal secretary and renowned editor of his works — to whom Como dedicates his book — observes that many of Lewis’s best books were conceived under the shadow of the Second World War. He began writing The Problem of Pain (1940) in the summer of 1939, on the eve of Hitler’s invasion of Poland. In the same year, within weeks after the first air-raid sirens were sounded in London, Lewis wrote a fragment of what would become The Chronicles of Narnia, probably his best-known work. The first book in the series, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950), tells the story of the Pevensie children, who travel through a magic wardrobe into Narnia, the kingdom ruled by Aslan, the Great Lion: “This story is about something that happened to them when they were sent away from London during the war because of the air-raids.”

Likewise, it was during a church service on Sunday, July 21, 1940—at the start of the Battle of Britain — that Lewis got the idea for The Screwtape Letters (1942), the fictional correspondence between a senior devil, Screwtape, and his apprentice, Wormwood. His most significant apologetic work, Mere Christianity (1952), was based on a series of radio talks he delivered over the BBC, beginning in 1941, when the survival of Western civilization was an open question. Like no one else, Lewis could transform dry religious dogma into something plausible and appealing. Not only has Mere Christianity been bought, translated, and quoted more than any of his other works but, Como says, it “has catalyzed many conversions.”

Comprehensive, lucid, rich in moral insight, C. S. Lewis pays homage to Lewis’s talent for uniting Christian teaching with the deepest yearnings of the human heart. In his autobiography, Surprised by Joy (1955), Lewis describes what he calls “the dialectic of desire,” when we experience a sudden stab of joy and longing, which quickly vanishes and sends us on a search for its source. “Joy itself, considered simply as an event in my own mind, turned out to be of no value at all,” he wrote. “All the value lay in that of which Joy was the desiring.”

Lewis concluded that this experience, which he mediated through books, or music, or nature, could not be a cruel fiction. Thus we read in Till We Have Faces (1956), a retelling of the myth of Cupid and Psyche: “The sweetest thing in all my life has been the longing — to reach the Mountain, to find the place where all the beauty came from. . . . Do you think it all meant nothing, all the longing? The longing for home?” Como writes that Lewis “lost interest in Joy itself after his conversion.” Perhaps it is better to say that Lewis redirected his attention: from his own experience to that of his fellow travelers.

Joy was the subject of probably his most famous sermon, “The Weight of Glory.” Preached on June 8, 1941, in the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin in Oxford, it must rank as one of the most profound and poignant messages about divine love ever delivered from any modern pulpit:

At present we are on the outside of the world, the wrong side of the door. We discern the freshness and purity of the morning, but they do not make us fresh and pure. We cannot mingle with the splendors we see. But all the leaves of the New Testament are rustling with the rumor that it will not always be so. Some day, God willing, we shall get in.

If Lewis’s vision of God’s glory is correct, then perhaps no other author over the last century has done more to help others to taste the divine happiness, to find their way home, to reach Aslan’s country. “A cleft has opened in the pitiless walls of the world, and we are invited to follow our great Captain inside,” Lewis wrote. “The following Him is, of course, the essential point.”

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

August 16, 2019

National Review: An Insider’s Guide to Italian Insults

This article was originally posted at National Review.

The tragicomic irony of Chris Cuomo’s pugilistic outburst earlier this week — cursing and physically threatening a man for taunting him with a reference to the movie The Godfather — is that the CNN anchor reinforced the usual tropes about Italian Americans. We are all wise-guys, goons, and Mafiosi, just itching to beat the stuffing out of anyone who gives us the malocchio, the evil eye.

“No, punk-ass b—es from the right call me ‘Fredo.’ My name is Chris Cuomo. I’m an anchor on CNN,” Cuomo says in a video that went viral. Cuomo is painfully aware that conservative talk-show hosts routinely refer to him as “Fredo,” i.e., Frederico Corleone, the dumb, wimpish brother from the Godfather trilogy.

The argument between the two men escalates:

Cuomo: “It’s a f—ing insult to the people. … It’s like the N-word for us.”

“What are you going to do about it?”

Cuomo: “I’ll f—ing ruin your sh—t. I’ll f—ing throw you down these stairs like a f—ing punk…Take a swing, c’mon boy.”

In his feverish imagination, Cuomo is gallantly defending his honor and ethnic heritage in front of his wife and nine-year-old daughter. In his stunted emotional world, threatening to maim or murder a man for calling him an idiot should inspire admiration.

And it does, beginning with CNN. “Chris Cuomo defended himself when he was verbally attacked with the use of an ethnic slur in an orchestrated setup,” wrote CNN spokesman Matt Dornic in a statement. “We completely support him.” People as ideologically diverse as actor Alec Baldwin and Fox News host Sean Hannity — who seem to know as much about Italian Americans as they do about anger management — offered their support. What Cuomo and his defenders cannot understand is that rather than exonerating himself, he reduced himself to a cultural stereotype.

Other than Chris Cuomo, no Italian American thinks that “Fredo” is the moral equivalent of the N-word to African Americans. In fact, we have a much more colorful stock of words to insult people for their lack of intelligence or other infirmities. Let me share a few.

There is the provocative scungille, which literally means a large snail. We might toss them in a salad or serve them in a red sauce (scungilli a la marinara). But, as urban dictionaries indicate, we often use it to mean “a slow person who cannot perform ordinary tasks.” At a baseball game, for example, if an infielder for the home team keeps bobbling routine ground balls, we might say, “Get that scungille off the field.”

There is the rhythmic mammalucco. It means a chump, a patsy, a guppy. As the older Italian brother might say, “My sister is dating a real mammalucco.”

There is the innocuous-sounding ciuccio, which literally means a baby’s pacifier. But we use it (along with the abbreviated slang chooch) to mean a moron or a jackass: “Tony gambled away his nest egg for retirement. What a chooch.”

There is the unpleasant fa schifo, which means “you make me sick, that’s disgusting.” Italian mothers use this phrase all the time, usually aimed either at their husbands or whatever mess their children are getting themselves into.

And there is the lyrical mezza stunad, a Loconte family favorite. It is derived from the Italian stonato, “out of tune.” It means you have your head in the clouds, or you’re not paying attention to reality: “Hey, mezza stunad, you walked right past me and didn’t say hello.”

My father was born in southern Italy, near Bari, and my mom’s family (Aiello) emigrated from an island off the coast of Naples, and so these were everyday expressions in the Loconte household.

I should add that throughout the years of the Clinton administration, my father became very fond of the word bugiardo, which means liar. Which brings us back to Chris Cuomo. There is nothing racist about being called Fredo. It means you are dimwitted and insecure, if sometimes well-intentioned. It was a lie to pretend otherwise — a race-baiting slander that has become the immoral reflex of the disciples of modern liberalism.

Although Cuomo has shown a glimmer of regret for his unhinged, violent outburst, he has revealed himself fully for what he has long appeared to be: a teppista, a thug in a thousand-dollar suit. Cuomo is the ugly embodiment of what is happening in elite circles in America — in politics, in the academy, entertainment, and journalism. Rational debate is being replaced by self-righteous rage, the citizen displaced by the stormtrooper.

Fredo, in fact, would be an improvement.

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

June 28, 2019

Wall Street Journal: The Versailles Treaty Gets a Bum Rap

This article was originally posted at Wall Street Journal.

The agreement that officially ended World War I has borne an impossibly heavy burden: The harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, embittered Germany and set the stage for the rise of Nazism and World War II. This is mostly a myth. It was the Great War itself, not the treaty that concluded it, that set loose the forces and ideologies that would convulse Europe and initiate another global conflict.

The year 1919 was, in fact, a catalytic moment in the history of the West. In January, the German Workers’ Party, the fiercely nationalistic and anti-Semitic precursor to the Nazis, was launched in Munich—nearly six months before the terms of the Versailles treaty were known. In March, Benito Mussolini, a war veteran, founded what became the Fascist Party in Milan. “The Fascist conception of the State is all embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value,” he declared. Mussolini became prime minister in 1922. The first European state to dispense with constitutional government and embrace fascism was Italy—one of World War I’s victors.

Also in March 1919, 51 representatives from two dozen countries met in Moscow at the Founding Congress of the Communist International. Long before Versailles, the other great totalitarian ideology of the 20th century, Marxism-Leninism, was on the march.

Civilization itself had been ravaged by the Great War. Empires collapsed; national economies were ruined. More than 40 million people were killed, injured or permanently disfigured—and for what? The shellshocked veteran became a walking metaphor for the mental outlook of many Europeans.

Yet historians often neglect the spiritual calamity brought about by the conflict—the emotional and moral vertigo that afflicted both elite and middle-class Europeans in the first decade after the war. Erich Remarque’s blockbuster novel, All Quiet on the Western Front (1928), described ex-soldiers returning to civilian life as “weary, broken, burnt out, rootless, and without hope.” In The Ordeal of This Generation (1929), Gilbert Murray, a leading classicist scholar, warned of “a large and outspoken rejection of all religion and particularly of all morality.” Before he became a Christian, C.S. Lewis—who was nearly killed in the trenches in France—confessed his newfound atheism to a friend: “I am not going to go back to the bondage of believing in any old (and already decaying) superstition.”

Skepticism was all the rage. American journalist Walter Lippmann lamented the decline of traditional religious beliefs and the moral order they provided. “The acids of modernity have dissolved that order for many of us,” he wrote in A Preface to Morals (1928), “and there are some in consequence who think that the needs which religion fulfilled have also been dissolved.”

The watchword of the decade was disillusionment. Nearly everything associated with the ideals and institutions of liberal democracy, including traditional religion, was taken to the woodshed. It was, after all, the “enlightened” nations of Europe that had engaged in what amounted to a remorseless suicide pact. “When it was all over, Torture and Cannibalism were the only two expedients that the civilized, scientific, Christian States had been able to deny themselves,” observed Winston Churchill, “and these were of doubtful utility.”

It is true that Hitler and the Nazis exploited resentment at the reparations demanded of Germany for its role in the conflict. The “war-guilt clause” of the Versailles treaty—making Germany and its allies responsible for causing “all the loss and damage” of the conflict—was widely denounced as “the war-guilt lie.”

The real deception, however, was the fantastical narrative of victory concocted by Germany’s military leaders. Even after the terrible losses during their failed spring offensive in 1918, even after American troops began pouring into France at the rate of 200,000 a month, the German people believed that their army was invincible—and undefeated in the field. So why did they capitulate at Versailles? The German nation, its leaders claimed, had been “stabbed in the back” by socialists, Jews and other enemies of the Reich. No treaty could have undone the psychological damage the German leadership inflicted upon its own citizens.

The catastrophe of the Great War left a hungry void. Communist predictions of the self-immolation of capitalist societies seemed to be stunningly validated. Fascist warnings about a “sickness” in the racial stock of European society found support in educated circles, where the new “scientific” theory of eugenics was already established. No treaty, no matter how just or generous, could puncture the utopian delusions that were displacing the political and religious beliefs of entire populations.

Traditional religion, in its most prophetic and morally serious expression, might have held back the forces of bigotry and terror. But the teachings of the Bible were being discarded throughout Western society. “The modern man has ceased to believe in it but he has not ceased to be credulous, and the need to believe haunts him,” wrote Lippmann. “It is no wonder that his impulse is to turn back from his freedom, and to find someone who says he knows the truth and can tell him what to do, to find the shrine of some new god, of any cult however newfangled, where he can kneel and be comforted.”

Secular idols—new and fearsome political religions—had appeared in Europe, and no treaty could have kept them from capturing the hearts of millions of worshipers. In 1919, a new age of faith had begun.

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

June 27, 2019

Providence: 1919: Wilson, the Covenant, and the Improbable League

This article was originally posted at Providence.

VERSAILLES, France—From a window in the Hall of Mirrors at the Versailles Palace, the view of its famed gardens and fountains is a welcome reward for negotiating the crush of tourists throughout the palace chambers. Here is a haven of natural and man-made beauty, serenity, and order. Yet a hundred years ago the view from this room would have been much different.

Beginning early in the day on June 28, 1919, onlookers gathered outside the palace, waiting for the outcome of diplomatic negotiations that had dragged on for months. The scene was a swirling mix of emotions: anxiety, grief, bitterness, resignation, and hope. Collectively, they had endured the industrialized slaughter of their youth, the near collapse of their economies, the shattering of their political institutions. The diplomats, who had assembled in the Hall of Mirrors at 3:00 pm, emerged less than an hour later to announce that the Treaty of Versailles—the agreement officially ending the First World War—had been signed. The crowd showered the delegates with flowers and erupted into cheers and shouts of relief.

The man of the moment was US President Woodrow Wilson. More than any other statesman, Wilson imposed his will upon the Versailles Treaty: a breathtaking attempt to redesign the entire international order based on democratic ideals.

Wilson’s brainchild and crowning achievement, the League of Nations, offered a new vision for international relations: a peace-loving “community of power” to replace the “balance of power” that had dominated European politics for centuries. It would be based on “the principle of justice to all peoples and nationalities, and their right to live on equal terms of liberty and safety with one another, whether they be strong or weak.” This was the central democratic truth that the League was meant to embody. “We have accepted that truth,” Wilson said, “and we are going to be led by it, and it is going to lead us, and through us the world, out into pastures of quietness and peace such as the world never dreamed of before.”

Barely 20 years later, in September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, igniting the Second World War.

Diplomatic historians invoke the phrase “Wilsonian idealism” to describe the American president’s outlook as he tried to reimagine the new world order. Yet many fail to grasp how Wilson’s humanistic and religious assumptions turned his democratic project into a fool’s errand.

Up until the First World War, European diplomacy was based on practical and materialistic factors, such as economic competition, access to markets, and military strength. It was rooted in realpolitik: in the observable fact that nations were engaged in the acquisition and maintenance of power, and that they made alliances and went to war to defend their national interests. After the defeat of Napoleonic France, the equilibrium in Europe was maintained by a balance of power, a network of alliances that sought to prevent any single state or combination of states from dominating the continent.

Wilson was determined to tear away and rebuild the entire foundation for international politics. He seemed to have recent history on his side. The political machinations of the European powers had failed to prevent the catastrophe of 1914–18, the costliest and most devastating conflict ever fought. No rational individual, Wilson reasoned, would want to undergo another global war—nor would any rational nation. “There is only one power to put behind the liberation of mankind, and that is the power of mankind,” Wilson said in a 1919 speech defending the League. “It is the power of the united moral forces of the world, and in the Covenant of the League of Nations the moral forces of the world are mobilized.”

The treaty’s articles establishing the League of Nations bear the Wilson stamp. Article 10 provides that “the Members of the League undertake to respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members of the League.” Article 16 builds upon this communal obligation: “Should any Member of the League resort to war in disregard of its covenants…it shall ipso facto be deemed to have committed an act of war against all other Members of the League.”

It is a remarkable proposal, underscored by Wilson’s insistence on the use of the phrase “covenant,” an effort to endow the League with a sacred aura. (Wilson was a lifelong Presbyterian, though his commitment to historical Christianity is debated by his biographers.) Under the terms of the treaty, an act of aggression anywhere in the world created a moral and political obligation upon all other League members: a willingness to mobilize their economic and military resources to confront the aggressor state, whether or not their national interests were threatened. Unlike any other international arrangement in human history, Wilson’s League would be an alliance based not on national interests, but rather on the principle of peace and the defense of democratic ideals.

Although the US Senate failed to ratify the treaty, 63 other nations adopted it. Gilbert Murray, a British classical scholar who served on an advisory committee to the League, suggested that Wilson’s view was embraced by a growing number of politicians and ordinary citizens throughout the 1920s and ’30s. “The whole enterprise of the League is a great adventure, and an adventure based upon a great Repentance,” writes Murray in The Ordeal of This Generation (1928). “The abolition of war among the civilized nations is not yet assured, but it is within human power. It is almost within reach.”

The concept of national “repentance” has a long historical pedigree, of course, but it is fraught with intellectual confusion. Nation-states, after all, are not like individuals; they do not possess an immortal soul, with an individual conscience, to which they are held accountable to God. Yet Wilson seemed to believe that what applies to individuals applies to nations. He apparently believed in the essentially rational and pacific nature of man:

The most dangerous thing for a bad cause is to expose it to the opinion of the world. The most certain way that you can prove that a man is mistaken is by letting all his neighbors know what he thinks, by letting all his neighbors discuss what he thinks, and if he is in the wrong you will notice that he will stay at home, he will not walk on the street. He will be afraid of the eyes of his neighbors. He will be afraid of their judgment of his character. He will know that his cause is lost unless he can sustain it by the arguments of right and of justice. The same law that applies to individuals applies to nations.

It follows that members of the League will dissuade other members from taking aggressive action against their neighbors; their collective moral judgment, expressed through an international tribunal and other institutions, will deter international conflict.

Yet Wilson’s first premise—the belief that an individual ready to commit an act of aggression will be thwarted by the threat of public shame—is verifiably untrue. It might describe some members of the faculty at Princeton University, where Wilson served as president before entering politics. It does not describe human societies as we have known them since the dawn of civilization. And what is not true of the individual inclined toward evil could not possibly be true of nation-states, with their potential for collective evil magnified by the tools of modern science and technology.

Nevertheless, historian Margaret MacMillan writes that “Wilson kept alive the hope that human society, despite the evidence, was getting better, that nations would one day live in harmony.” Henry Kissinger, the quintessential realist during the Cold War, saw in this a deficient understanding of human nature. “European leaders had no categories of thought to encompass such views,” he writes. “Neither their domestic institutions nor their international order had been based on political theories postulating man’s essential goodness.”

Wilson’s League could not reckon with the ways in which the Great War had damaged the moral and spiritual outlook of European society. As Winston Churchill described it, “The fire roared on till it burned itself out.” Nations that had been so devastated by the mechanized horror of the war could not easily quell the resentments and grievances of their populations. Thus, the tragedy of Versailles is twofold. First, there was the belief that governments would be prepared to transform their foreign policies into expressions of the Sermon on the Mount. Second, there was the notion that a “community of power” would be capable of acting collectively to face down the inevitable threats to international peace and security.

“Truly, this was a peace which had the tragedies of the future written into it as by the devil’s own hand,” writes George Kennan, US ambassador to the Soviet Union. “This was the sort of peace you got when you allowed war hysteria and impractical idealism to lie down together in your mind, like the lion and the lamb; when you indulged yourself in the colossal conceit of thinking that you could suddenly make international life over into what you believed to be your own image.”

Under this humanistic vision, no treaty, no covenant, no league of nations could effectively confront the Will to Power. By 1919, when the Treaty of Versailles was signed, the forces of totalitarianism were already on the move: Italy’s Benito Mussolini founded the first fascist party in Europe; the German Workers’ Party, the precursor to the Nazis, was launched in Munich; and representatives from two dozen countries met in Moscow at the Founding Congress of the Communist International.

Perhaps an insight from the character of Elrond in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, about the nature of our mortal lives, offers a measure of Christian realism in the face of Versailles: “And the Elves believed that evil was ended forever, and it was not so.”

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

June 25, 2019

National Review: Mussolini and the End of Liberal Democracy

This article was originally posted at National Review.

One popular myth about European fascism is that its roots were planted in the rancid soil of Versailles — the Treaty of Versailles, that is, signed a century ago, on June 28, 1919, which officially ended the First World War. The punitive terms of the agreement, we are told, enraged and demoralized a defeated Germany, making the rise of Hitler and Fascism inevitable. In fact, the origins of Fascism can be traced here in Milan, in the Piazza San Sepolcro. It was here, three months before Versailles, that Benito Mussolini, a former soldier who had fought on the winning side of the war, launched the Fascist movement.

It was a ragbag of a gathering. On Sunday morning, March 23, Mussolini addressed a group of perhaps 120 men and several women: dispirited socialists, ex-soldiers, futurists, anarchists, and other unclassifiable revolutionaries. What united them, among other things, was a belief that Italy’s horrific sacrifice for the Allied cause in the Great War — over 650,000 killed and 950,000 wounded — demanded national regeneration. She must not be denied the spoils of war: no vittoria mutilata, or mutilated victory. Barely three years later, 25,000 black-shirted followers marched on Rome, sweeping Mussolini into the government. “Liberalism denied the State in the name of the individual,” he proclaimed. “Fascism reasserts the rights of the State as expressing the real essence of the individual.”

The Italian journey from constitutional monarchy to Fascist dictatorship is a cautionary tale for both liberals and conservatives. Although he is viewed as a creature of the political right, Mussolini often enlisted the ideals and tactics of the political left. His success — he ruled for 20 years — is not only a warning about the fever of nationalism. It is a reminder that leftist promises to create perfectly egalitarian societies can reap a whirlwind of violence and disillusionment.

Mussolini began preaching revolutionary change in February 1918, after returning from the front and resuming his job editing Il Popolo d’Italia. Although he had abandoned his socialism a few years earlier, he understood its appeal: “It is a question of organizing the state to ensure the greatest individual and social well-being.” Italy’s parliamentary government, he suggested, should be dominated by “a man who is ruthless and energetic enough to make a clean sweep.”

Bombastic, charismatic, visionary: Mussolini presented himself as that man, ready to seize the historical moment. He organized his followers into a fascio di combattimento, a fighting group, who took the Roman fasces, the term for a bundle of sticks bound with ropes, as their symbol of unity. “We demand the right and proclaim the duty to transform Italian life,” he said at the Milan meeting, “if it proves inevitable using revolutionary means.”

Italy’s post-war economic situation, though not as severe as the one in Germany, was ripe for exploitation. There were painful divisions over Italy’s participation in the war. Parliament — denounced by Mussolini as “invincibly nauseous” — was widely discredited. The monarchy was unloved. Writes historian R. J. B. Bosworth in Mussolini’s Italy: “For Italy, least of the great powers, poorest of the great economies, most fragile of the great societies . . . the conversion from war to peace entailed a sea of troubles.”

The war appeared to ravage the assumptions of the old order. All over Eastern Europe, political legitimacy was in doubt and national borders were being contested. Meanwhile, the violence and disorder created by the advance of international Communism was causing a panic. The Bolsheviks had plunged Russia into a vicious civil war, and although Italian socialism proffered a more humane face, to many Italians it led to the same future: class warfare, the erosion of property rights, mob violence, and contempt for national and cultural identity.

Italy’s economic woes accentuated the socialist appeal. Inflation was rising faster than it had during the war. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers returning from combat — including 220,000 who were disabled — struggled to find work. On a personal note: My Italian grandfather, Michael Loconte, was living and working in the United States when war broke out. He opted to fight with the American military in France, was naturalized as a U.S. citizen after the war, and settled with his family in New York City. His instincts were good: In the summer of 1919, of the 1.5 million Italian soldiers still serving in the army, roughly a quarter were deployed within Italy to guarantee public order. There was a palpable fear of a socialist revolution.

Those fears were magnified in the general election of November 16, 1919. Mussolini and his Fascist allies were on the ballot, but they suffered humiliating losses. Meanwhile, the socialists won roughly 1.8 million votes and claimed 156 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, making them the largest political party. The left-wing paper, Avanti!, declared Mussolini a political corpse; his coffin was paraded through the streets of Milan, along with dirge-singing demonstrators.

The funeral celebrations were premature. Efforts to reconvert the war economy were flailing; strikes and riots over the cost of living accelerated. All over Italy, trains, banks, and public buildings were attacked by mobs. Local “Soviets” were announced, and some areas of the country fell under complete Communist control. But neither the Socialist party nor the Italian Popular party (composed of Catholic socialists) offered any effective polices. Fascism found nourishment in socialism’s weakness. Writes Christopher Hibbert in Mussolini: The Rise and Fall of Il Duce: “The Fascists put themselves forward as saviors of the country, the only force by which Bolshevism could be checked and strangled.”

There was a good deal of strangling to be done. Squads of Fascists, the squadristi, armed with knives, rifles, and revolvers, assaulted Communists and their sympathizers. With government complicity, roughly 3.000 anti-Fascists were murdered between October 1920 and the March on Rome in October 1922. Mussolini did not have to seize power; he was offered it by King Victor Emmanuel III. Immediately after forming a coalition government, he demanded from the Chamber of Deputies unrestricted authority to implement his reforms. He was granted these powers by a majority of 275 votes to 90.

It would not be long before Mussolini articulated his view of the state, which would captivate Adolf Hitler:

The Fascist conception of the State is all embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value. Thus understood, Fascism is totalitarian, and the Fascist State — a synthesis and a unit inclusive of all values — interprets, develops, and potentiates the whole life of a people.

Thus, it was Mussolini, not Hitler, who introduced the Fascist disease into the bloodstream of Europe. And he succeeded not because Italian diplomats failed to deliver the goods at Versailles. Whatever his motives in his campaign to rebuild a battered nation, Mussolini understood something of the human longing for purpose and community. Perhaps our current political culture is not so immune as we think to the cant and propaganda of Il Duce’s Italy.

Italian Fascism, after all, promised national greatness, unity, spirituality, and a “third way” between capitalism and socialism. Instead, it brought to the Italians World War II, the bombing and occupation of their cities, widespread poverty, and the loss of basic civil liberties. While claiming that the Fascist state “defends and protects” religion, Mussolini despised the teachings of Christianity and manipulated the Vatican to consolidate his power. Italy’s political unity was short-lived — achieved by a singular Duce with a violent disregard for dissent — and it left behind a deeply divided society.

With no sense of irony, liberals now invoke fascism as an epithet to dismiss their conservative critics. But is the echo of Mussolini more likely to be heard among the political Right? The animating spirit of fascism — its martial zeal for a statist utopian vision — seems quite welcome in the citadels of modern liberalism. The fascist negation of religious truths, by which all political choices are to be judged, has found countless disciples in progressive circles. The Fascist state “has curtailed useless or harmful liberties while preserving those which are essential,” Mussolini declared. “In such matters, the individual cannot be the judge, but the State only.”

Benito Mussolini was the first political leader to write the epitaph for liberal democracy in Europe. Yet it was liberal democracy, through a recovery of moral vigor, that managed to defeat Fascism. In the Piazza San Sepolcro in Milan, the building in which Mussolini and his followers first vowed to overthrow the established order still stands. It houses a police station. The rule of law has replaced the rule of the dictator. Once worshipped like a god, Mussolini became a pariah because of his disastrous alliance with Hitler’s Germany. He fled Milan in April 1945 but was caught and executed: Shot in the chest, his body was strung up to cheers and mockery.

It was, according to an eyewitness, “as if the whole thing was a dream from which we would awake to find the world unchanged.”

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

May 14, 2019

National Review: Tolkien Film Fails to Capture the Majesty of His Achievement

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Perhaps Finnish film director Dome Karukoski took on an impossible task with his biopic Tolkien. When J. R. R. Tolkien began writing The Lord of the Rings, he hoped to give England something he thought it lacked: an epic and transcendent tale of its mythic origins. “I was from early days grieved by the poverty of my own beloved country,” Tolkien explained. “It had no stories of its own (bound up with its tongue and soil), not of the quality that I sought.” The astonishing appeal of the work — it has sold more than 150 million copies and been translated into dozens of languages — suggests that Tolkien has come closer to achieving that goal than any other author.

And therein lies the challenge: to produce a film about imagination. In Tolkien’s case, this requires much more than biographical knowledge. Screenwriters David Gleeson and Stephen Beresford recreate some beautiful and authentic moments, especially in exploring Tolkien’s passion for languages. The relationship between Tolkien and Edith, the love of his life, is told with tenderness and reserve. Tolkien’s combat experience in the First World War — the plot is revealed through a series of flashbacks from the trenches in France — is a key ingredient in the story. Ultimately, however, the film fails to tap the deepest sources — both human and divine — of Tolkien’s restless, creative genius.

It is refreshing to see a film that takes up the theme of friendship, especially robust male friendship, which was so vital to Tolkien’s life and career. Tolkien (capably played by Nicholas Hoult) establishes a rich circle of friendships at the King Edward’s School in Birmingham. Together with Geoffrey Bache Smith, Christopher Wiseman, and Robert Gilson, the boys fashion a literary-artistic club with no mean purpose: to change the world.

Yet the film devotes more time to idle bantering and boozing than it does to the group’s literary and moral purposes. It also overlooks a crucial exchange: a meeting in December 1914, dubbed “the Council of London,” which was transformative for Tolkien. “In fact it was a council of life,” writes John Garth, author of the magisterial Tolkien and the Great War. The prospect of the trenches had a sobering effect. Late into the night they talked and debated — about love, literature, patriotism, and religion. It was at this moment, and among this fellowship, that Tolkien began to sense his literary calling. “For Tolkien, the weekend was a revelation,” Garth concludes, “and he came to regard it as a turning point in his creative life.”

If the film’s writers wanted to depict such a revelatory scene — which they don’t — it would have required familiarity with an ancient source of wisdom. We no longer appreciate how the educated classes of Tolkien’s generation were schooled in the classical and medieval literary traditions. From works such as Virgil’s Aeneid, Tolkien not only read the mythic and violent story of Rome’s beginnings, but also absorbed the concept of the noble and sacrificial quest. Indeed, probably the most influential work in Tolkien’s professional life was Beowulf, which he read as a young man and considered one of the greatest poems of English literature. Declares its epic hero: “Fate oft saveth a man not doomed to die, when his valour fails not.” Tolkien taught, translated, and studied the poem throughout his career.

These older works — once taught as part of the canon of Western civilization — embody something that is almost anathema to our twitter-saturated minds: depth of imagination. “In all these works there was a sense that the author knew more than he was telling,” writes Tom Shippey in The Road to Middle-Earth, “that behind his immediate story there was a coherent, consistent, deeply fascinating world about which he had no time (then) to speak.” This, of course, is part of Tolkien’s remarkable legacy. By drawing maps, inventing new languages, and creating histories and genealogies for the inhabitants of his world, Tolkien convinces us that Middle-earth was a real place where real things of great consequence occurred.

The literature important to the man who created perhaps the most beloved character of modern fiction — the hobbit — offers a view of the heroic pointedly at odds with the Hollywood conception. Tolkien was attracted, aesthetically and spiritually, to works that exalted courage in the context of a tragic world — a world in which defeat is likely and there are no permanent victories. “The worth of defeated valor in this world is deeply felt,” Tolkien declared in his 1936 lecture “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” The author of Beowulf, he explained, “showed forth the permanent value of that pietas which treasures the memory of man’s struggles in the dark past, man fallen and not yet saved, disgraced but not dethroned.”

These are deep waters. Like no one else, Tolkien retrieved the truths and virtues of the ancient myths and reintroduced them to the modern mind. And, remarkably, he accomplished this in a post-war European society — a “waste land,” in T. S. Eliot’s words — that had soured on the ideas of bravery, valor, virtue, and patriotism. “To say that in it heroic romance, gorgeous, eloquent, and unashamed, has suddenly returned at a period almost pathological in its anti-romanticism is inadequate,” wrote his Oxford friend C. S. Lewis in an early review. “Nothing quite like it was ever done before.”

Perhaps this is the most regrettable failing of Tolkien: For all of its impressive production values — and for all the respect its director brings to his subject — the film does not grasp the nature of Tolkien’s achievement, much less its potential sources. Instead, we are presented with World War I battle scenes where a shell-shocked Tolkien has visions, or hallucinations, of the fire-breathing dragons and Black Riders that will terrify us in The Lord of the Rings. Of course, no soldier who fought at the Battle of the Somme, where Tolkien tasted “the animal horror” of combat, passed through its hellish flames unscathed. But, as John Garth insightfully explains, Tolkien thought carefully about how the experiences of war can illuminate other, nobler aspects of the human condition. His epic work, Garth writes, “puts glory, honor, majesty, as well as courage, under such stress that they often fracture, but are not utterly destroyed.”

It is this aspect of Tolkien’s fiction that seems to demand something more than a purely materialist or humanist outlook: We cannot fully account for his staggering creativity absent his Christian beliefs. A convert to Catholicism in his youth, Tolkien was unambiguous about the importance of his faith to his life and work. He viewed myths, for example, not merely as human inventions but as a literary means by which God communicates a portion of his truth to the world: a “splintered fragment of the true light.” Tolkien likened the work of the myth-maker to that of a “sub-creator” who helps to fulfill God’s purposes as the Creator.

The author of The Lord of the Rings is still accused of “escapism,” of being so burdened by the loss and sorrows of war that he sought refuge in his imaginary Shire. It is a charge that Tolkien cannot refute, because the film lacks the author’s spiritual commitments. Tolkien’s entire conceptual approach, anchored in a belief in the fall of man and in the hope of redemption, helps to account both for the extraordinary realism and imaginative power of his fiction.

Here is what animates Tolkien’s fierce literary ambition, the central mystery that the film cannot penetrate: It is a belief in what he called the eucatastrophe — a sudden act of grace — whose expression he regarded as the highest function of the fairy tale. “It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance,” he writes in On Fairy Stories. “It denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

Grief and Joy, as sharp as swords, reconciled by grace: that would be a story worth telling.

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

March 19, 2019

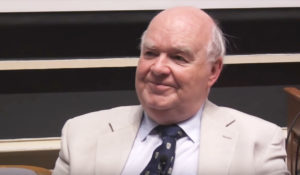

National Review: John Lennox, The Oxford Mathematics Professor Who Defends Christianity

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Oxford, England — John Lennox, emeritus professor of mathematics at the University of Oxford, leans forward in his chair, his blue eyes brightening, as he explains how his peculiar profession nearly shipwrecked the academic career of one of his intellectual heroes, Christian author and apologist C. S. Lewis.

Shortly before he disembarked for France to fight in the British Army during the First World War, Lewis failed his “fearsome” qualifying examination in algebra to continue his studies at Oxford. “He had to go to a crammer, which is an ancient word for a school where they crammed the information into you,” Lennox tells me. “But the world war intervened.” When Lewis returned to Oxford in January 1919, the university waived the mathematics requirement for him and other war veterans. “So, we were in a hair’s breadth of never having Lewis’s literary genius and output because of algebra — the subject I love,” he laughs. “There is something ironic in that.”

Perhaps something providential as well. By the time Lennox arrived at Cambridge University as an undergraduate in 1962, he already had devoured many of Lewis’s writings. He couldn’t resist sneaking out of his math lectures to hear Lewis lecture on John Donne before a packed auditorium.

More than any other thinker, it was Lewis — an atheist who converted to Christianity with the help of J. R. R. Tolkien — who gave Lennox the conceptual tools to confront the materialist objections to faith in God. “I thought it was very important to try to walk inside the shoes of someone who knew atheism from the inside, and Lewis provided that guide to me,” he says. “In all his questioning, there was the slow development of his impression that there was a God who could be taken seriously. All of that became very important to me.”

Now, at 75, Lennox has distinguished himself internationally for his intellectual defense of Christianity. He has debated — and, according to his admirers, bested — celebrated atheists such as Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and Peter Singer. A fellow in the philosophy of science at Oxford, he writes books that explore the essential compatibility between the scientific quest, rightly understood, and religious belief. Newton, Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo: All believed in a God who created and sustained the universe. “Instead of the founders of modern science being hindered by their belief in God,” Lennox reminds me, “their belief in God was the motor that drove their science.”

Citing Lewis’s approach in works such as The Abolition of Man, Lennox assails the notion that science is the only pathway to truth, or that it can explain the mystery of the human condition. In his sights are thinkers such as Peter Atkins, a professor of chemistry at Oxford who claims that “there is no reason to suppose that science cannot deal with every aspect of existence.”

Lennox discerns in this a self-defeating materialism. In books such as God’s Undertaker: Has Science Buried God? he argues that the scientist’s confidence in reason ultimately depends on the existence of a rational and purposeful Creator. Otherwise, our thoughts are nothing more than electro-chemical events, the chattering of soul-less synapses. “If you take the atheistic, naturalistic, materialistic view, you’re going to invalidate the reasoning process,” he says, “because in the end you’re going to say that the brain is simply the end product of a blind, unguided process. If that’s the case, why should you trust it?”

The materialist view inevitably gives birth to a form of determinism that appears to mock our essential humanity. Richard Dawkins, evolutionary biologist and atheist, expresses the modern scientific outlook thus: “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at the bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good. Nothing but blind, pitiless indifference. DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is. And we dance to its tune.” Yet biological determinism, Lennox explains, robs human beings of any claim to dignity and freedom. Free will, we are told, is an illusion.

Ironically, certain strains of conservative theology, what Lennox calls “religious determinism,” lead to the same result. In his recent book, Determined to Believe: The Sovereignty of God, Freedom, Faith and Human Responsibility, Lennox finds fault with Calvinist interpretations of Scripture that effectively negate human decision-making and moral responsibility.

“Free will,” he writes, “is that gift of God that gives us the capacity to come to God with empty hands.” By insisting that every decision and action in the world has been brought about by divine fiat, religious determinists make God the author of unspeakable evil. “It is hard to imagine that anyone could believe that such extreme deterministic ideas are even remotely Christian,” he writes. “They seem infinitely far away from describing the God of love revealed to us in Jesus Christ.”

In all of this Lennox follows in the footsteps of his theological mentor, C. S. Lewis. From his post at Oxford, he continues to communicate — in clear, compelling, and persuasive prose — the essential truths of the Christian faith to a wide and diverse audience. With a mathematician’s passion for logic, he embraces one of Lewis’s most famous maxims: “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen: not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.” Before our conversation ends, I am reminded of another link between them: Like Lewis, Lennox was born in Northern Ireland and made England his permanent home, while retaining his Ulster charm.

“C. S. Lewis was a brilliant intellectual. But he was an Irishman, you know,” he says with a smile. “There’s a warmth there, a visceral nature . . . he had a deep interest in understanding where people were coming from, and to relate his Christian faith to helping them.”

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

February 14, 2019

National Interest: The War over Liberal Democracy

This article was originally posted at The National Interest.

Fatalism about liberal democracy is nothing new and has always found a disaffected audience. Left-wing politicians, writers, academics, activists: for decades they have denounced the Western liberal project as the primal cause of racism, inequality and exploitation. This time, though, the most strident prophets of gloom are residents of the cultural and religious right. Liberalism has collapsed, they tell us, because it was steeped in sin from its birth: it has failed “because it was true to itself.”

The conservative critics of liberalism offer an important and often penetrating analysis of our social ills. The epidemic of loneliness, the rampant materialism, the dissolution of ties to family and community—these are fearsome problems. Yet the true object of their complaint lies in the very origins of the liberal order: its foundational beliefs and ideals. The right-wing condemnation of liberal democracy—supported by intellectual sins of omission and outright distortions of fact—is as mistaken as that of the radical left.

Behind their protest, one detects a wistful nostalgia for the pre-modern world, an attachment to the medieval concepts of virtue, community and authority. In this, they fail to reckon seriously, if at all, with the sins of Christendom: the denigration of individual conscience, the criminalization of dissent, the corrosive entanglement of church and state, the hedonism of clerical leadership and the deeply rooted anti-Semitism. The Catholic medieval project, for all its achievements, ultimately failed to uphold one of the most transformative ideas of the Jewish and Christian traditions: the freedom and dignity of every human soul.

The conservative critics of liberalism thus ignore its actual historical beginnings. The attempt to construct a Christian society through coercion led to the betrayal of the most basic biblical and humanistic ideals. The quest for a unified community, once idolized, unleashed a long campaign of repression and terror. This, at root, is what produced the existential crisis of Christendom.

Yet this catastrophic failure—judged as a deep contradiction of the life and teachings of Jesus—generated a robustly Christian response. In this sense, the liberal project began as a protest: whispered in the Christian humanism of Erasmus, quickened by Luther’s Reformation, advanced by John Locke’s biblical vision of natural rights and culminating in James Madison’s religiously rooted republicanism. The abandonment of liberalism—as suggested by its critics—will lead where it always has led: to widespread ignorance, servitude, tyranny and totalitarianism. Understanding and defending liberalism’s historical achievement is the first step toward any serious effort at cultural renewal.

The Christianization of the Roman Empire brought with it profound reforms in European law, politics and society. The Catholic Church ended Rome’s gladiatorial games, established institutions to care for the poor and abolished human slavery. The universities founded by the church in Paris, Bologna, Oxford and Toulouse were an innovation: institutions devoted primarily to higher learning. At its best, the monastic tradition helped to dignify the concept of work, challenged the materialism of medieval society, extolled the disciplines of prayer and the study of the Scriptures, and strengthened the relationship between Christian belief and Christian virtue.

Nevertheless, the medieval church eventually replicated—and institutionalized—the repressive habits of pagan Rome. By the eleventh century, the Roman pontiff embodied the desire of the church to impose its inflexible will on the entire Western Christian world.

In 1075, in an effort to end the emperor’s intrusion into church affairs, Pope Gregory VII issued “Dictates of the Pope,” an utterly revolutionary document in church-state relations. Among other propositions, it asserted the infallibility of the church and authority of the pope over every living creature—including every political authority. “He himself may be judged by no one,” the pope declared, adding that “all princes shall kiss his feet.” He even granted himself the power to depose emperors. In 1302, Pope Boniface VIII reaffirmed these claims in his Unam Sanctam (“One Holy”): “We declare, state, and define that it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff.”

Conservative critics of modernity properly fault those enlightenment thinkers who promoted “radical individualism” under the banner of liberty. One of the consequences, they explain, is a relentless quest for political power that renders democratic self-government impotent. The rise of the omni-competent state is indeed a formidable problem.

Yet it is not an entirely novel problem. In asserting claims of supremacy for the Roman pontiff, Gregory began by “looking within his own breast” for authority: an expression of individual autonomy that would make enlightenment philosophes blush. By attempting to consolidate in a single individual unprecedented—and unchallengeable—religious and political power, the church endorsed a theory of governance that would rival the political absolutism of Thomas Hobbes. By overreaching, the medieval church discredited itself before the emerging power centers of Europe.

There were other self-inflicted wounds. The Renaissance popes—who evidently inspired Mario Puzzo’s The Godfather —were notorious for their venality and greed in their own day. Clerical bribery, nepotism, sexual immorality, ruthless violence: these were open secrets among a disillusioned laity. Meanwhile, the sale of religious relics and indulgences invited the rank commercialization of the gospel. Patrick Deneen, a Catholic political scientist at Notre Dame, excoriates liberalism for promoting “hedonistic titillation” and a society obsessed with “consumption, appetite and detachment.” The critique neatly describes the ecclesiastical culture of late medieval Europe.

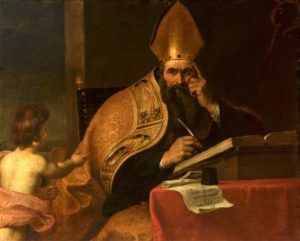

s between church and state, however, were not the only cause of the deepening crisis of Christendom. The gravest issue was its domestic policy: confronting the religiously unorthodox. Unlike ancient Rome, the Holy Roman Empire would not tolerate religious pluralism within its borders. No Christian thinker did more to legitimize the use of force against religious dissenters than Augustine of Hippo.

The patristic works of Origin, Jerome, Ambrose and others had cited the Bible to anathematize heterodox belief. But it was Augustine (354–430) who interpreted Jesus’ parable of the wedding feast in Luke’s gospel—“compel them to come in, that my house may be full”—as a rationale for the use of force against heretics. For Augustine, coercion of this kind was “a just persecution” aimed at rescuing souls from damnation and preventing the heretical disease from spreading. “The church persecutes out of love,” he wrote, “the ungodly out of cruelty.”

Thus, the greatest authority in Western Christianity—whose writings were disseminated widely in medieval Europe—put his stamp on state-sanctioned violence against the unorthodox. So entrenched was the Augustinian doctrine that the seventeenth-century philosopher, Pierre Bayle, a convert to Protestantism, was moved to compose a 600-page (in modern type) rebuttal. “I don’t think it possible to imagine anything more impious, or more injurious to Jesus Christ, or more fatal in its Consequences,” he argued in A Philosophical Commentary , “than his having given Christians a general Precept to make Conversions by Constraint.”

Nevertheless, a theology of coercion would instruct European society for well over a thousand years. It helped to underwrite the Inquisition: church tribunals created to root out heresy—a capital offense—and reconcile heretics to the church. First authorized by a church council in 1229 in France, clerical leaders vowed to “diligently, faithfully, and frequently seek out heretics” in their parishes. Church courts to judge the accused soon were established throughout Europe.

We need not overstate the brutalities of the Inquisition. Those judged guilty of heresy who renounced their views could find mercy and be restored to the church. Large public executions—like the two hundred Cathars burned at the stake at Verona in 1278—were rare. The machinery of the Inquisition was never as efficient as its proponents claimed. Nevertheless, over the span of six centuries, tens of thousands of people met violent deaths, their property seized and their families left destitute, for one reason: they dared to think differently about God than the established order.

In his much-discussed book, Why Liberalism Failed, Patrick Deneen fails to mention this feature of Christendom. Instead, he argues that the medieval cultivation of virtue was “a central defense against tyranny” and one of the distinguishing marks of European Christianity. “Protection of rights of individuals and the belief inviolable human dignity, if not always consistently recognized and practiced, were nonetheless philosophical achievements of premodern medieval Europe,” he writes. Rod Dreher, an editor at The American Conservative , brushes aside church abuses by extolling the “enchanted world” of medieval Europe, with its consciousness of spiritual realities. Medieval men and women “carried within their imagination a powerful vision of integration,” he writes in The Benedict Option . “In the medieval consensus, men construed reality in a way that empowered them to harmonize everything conceptually and find meaning amid the chaos.”

These are essentially pious fictions. The tragedy of Christendom—the everyday reality for ordinary men and women—was the establishment of a moral bond between Christianity and a culture of coercion, betrayal and terror. The church of the martyrs had transformed itself into the church of the inquisitors.