Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 16

March 18, 2016

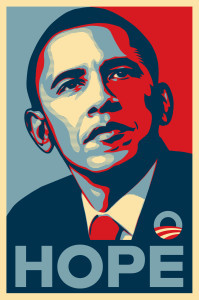

Providence: Journalism as Propaganda: Jeffrey Goldberg on the Obama Doctrine

This article was originally posted at Providence.

The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg begins his roughly 19,000-word examination of Barack Obama’s foreign policy by recounting the moment, on August 30, 2013, when the president reversed himself on his pledge to punish Syria’s Bashar al-Assad for using chemical weapons against his own people. Mr. Goldberg posits two contrasting judgments of that fateful hour: “the feckless Barack Obama brought to a premature end America’s reign as the world’s sole indispensable superpower” or “the sagacious Barack Obama peered into the Middle Eastern abyss and stepped back from the consuming void.”

Mr. Goldberg’s much-discussed article leans lopsidedly toward the latter judgment. He arrives at this unlikely destination by allowing Mr. Obama (and his advisors) to offer a specious, self-serving version of events unencumbered by unpleasant realities. Throughout the essay the reader is treated to a peculiar brand of journalism: an investigation that avoids asking hard questions, omits contradictory evidence, and either ignores or distorts seminal moments in American diplomatic history.

In Mr. Obama’s telling of his disastrous policy in Libya—now a failed state and safe haven for the Islamic State—the fault lies everywhere except at the White House. “When I go and ask myself what went wrong,” he said, “there’s room for criticism, because I had more faith in the Europeans, given Libya’s proximity, being invested in the follow-up.”

Here is the vintage Obama evasion: blame his failure of leadership on others, in this case the British, the French, or the previous administration. Mr. Goldberg is silent about the bitter irony that Mr. Obama, like his predecessor in Iraq, did not anticipate the chaotic aftermath of a post-Kaddafi regime in Libya. Nor is there any mention of the deadly assault on the U.S. embassy in Benghazi, or of the White House’s dishonest attempts to cover up their misdeeds in an election year.

In his treatment of the rise of the Islamic State, Mr. Goldberg simply parrots the administration’s risible claim that it was given bad intelligence about the organization’s potency: “By the late spring of 2014, after ISIS took the northern-Iraq city of Mosul, he came to believe that U.S. intelligence had failed to appreciate the severity of the threat and the inadequacies of the Iraqi army, and his view shifted.”

Nonsense. We know from congressional testimony that intelligence officials were warning the administration about the threat of the Islamic State long before the seizure of Mosul. We know that the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq made possible its lightening success in seizing large swaths of territory and strategic resources. Yet Mr. Goldberg does not allow these facts to intrude upon his narrative.

The omissions continue apace. There is no scrutiny of the fact that Mr. Obama, during his agonized decision-making over U.S. troop commitments in Afghanistan and Iraq, ignored the counsel of his top military advisors. His inept mishandling of Russia’s seizure of Crimea is brushed aside with glib fatalism. Mr. Obama is not asked about the Russian intrusion into Syria and its assault on Syrian rebels; or about Mr. Assad’s indiscriminate bombing campaigns on civilian targets, including hospitals; or about a refugee crisis not seen since the end of the Second World War. The president’s bluff over Mr. Assad’s use of chemical weapons is ultimately portrayed as an act of political courage. In all this, the reader never learns that three of Mr. Obama’s former defense secretaries have severely criticized him for his blindness to the threats to America’s national security.

President Obama defends his emphasis on diplomacy by denouncing what he calls “mythologies” about Ronald Reagan’s tough-minded foreign policy. President Reagan’s success in dealing with the Soviet Union, according to Mr. Obama, “was to recognize the opportunity that Gorbachev presented and to engage in extensive diplomacy.”

Here is liberalism’s fantastical version of the end of the Cold War. It had nothing to do with U.S. foreign policy, but rather was an inevitable and predictable outcome that coincidentally occurred on Mr. Reagan’s watch—except for the fact that not a single liberal predicted its collapse in the 1980s. We know—from Soviet dissidents, internal communist party communique, former Soviet officials, and even from Mr. Gorbachev—that it was the Reagan military build-up and the projection of U.S. military power that greatly accelerated the collapse of the Soviet Union. Yet instead of challenging Mr. Obama’s ignorance of these facts, his chummy interlocutor remains mute.

The president’s revisionist history grows from the soil of his ideological commitments. One is about power and its relationship to peace and security.

Mr. Obama denies, with an air of absurd self-assurance, that Russia has become more powerful following its adventures in Ukraine and Syria. To believe so, he says, “is to fundamentally misunderstand the nature of power in foreign affairs…Real power means you can get what you want without having to exert violence.” Here is the pacifist delusion: a vision of a world in which the forces of barbarism are domesticated through the sweet reasonableness of the “international community.”

Behind this view lies another ideological commitment—the enlightenment belief in human progress and unlimited human potential. “Look, I am not of the view that human beings are inherently evil,” Mr. Obama said. “I believe there is more good than bad in humanity. And if you look at the trajectory of history, I am optimistic. I believe that overall, humanity has become less violent, more tolerant…more able to manage difference.”

Many of the greatest figures in the Western tradition—its statesmen, political philosophers, and religious leaders—have held the opposite view. They took the fallen nature of man, the tragedy of the human soul alienated from its Creator, as the starting point for their politics. “What is government itself but one of the greatest reflections of human nature?” asked James Madison. “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.”

If Mr. Goldberg is familiar with this tradition, he is too timid to mention it. But can he really be as unreflective as Mr. Obama about the terrible lessons of the last century? I believe that overall, humanity has become less violent. For it was in the twentieth century when the most politically, technologically, and culturally advanced nations of the earth engaged in two horrific global conflicts. It was in this most recent century when political and social revolutions were unleased that enslaved and murdered hundreds of millions of human beings. It was in the century closest to our own that the word “genocide” had to be invented. Thus Russian Alexander Solzhenitsyn called the twentieth century “the caveman century.”

Mr. Goldberg’s conclusions about the “evolution” of the Obama doctrine, he informs us, are based on his exclusive conversations with Mr. Obama during his presidency. Perhaps his many omissions are best explained by his own frankly stated agenda: “My goal…was to see the world through Obama’s eyes, and to understand what he believes America’s role in the world should be.”

It is a curious mission for a journalist, since nearly all the major media outlets—not to mention most of the academy and the entertainment industry—trumpet Mr. Obama’s progressive vision of the world, and have done so every day of his administration. We already know what he believes about America’s role in the world. We now know what kinds of evils can be set loose when those beliefs direct American foreign policy.

In the end, Mr. Goldberg’s essay reveals practically nothing about the president’s thinking on foreign affairs. It merely reinforces the deeply impoverished mental outlook of modern liberalism.

Despite a posture of inquiry, the author’s journalistic empathy dissolves into rank advocacy: journalism as echo chamber. Here is what access to ultimate political power can breed: something that rings false from beginning to end, something much closer to propaganda than truth-seeking. Edward R. Murrow, who raised a new standard for honest and critically-minded journalism in the 1950s, warned about this trend. “A nation of sheep,” he said, “will beget a government of wolves.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

February 29, 2016

Providence: Syria Peace Plan and Diplomatic Delusions

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Testifying before Congress last week, Secretary of State John Kerry defended his role in brokering a cease fire in the Syrian civil war—a temporary “cessation of hostilities” that no one expects to produce a just outcome for the Syrian people. “If it doesn’t work, the potential is there that Syria will be utterly destroyed,” Mr. Kerry warned. “The fact is that we need to make certain that we are exploring and exhausting every option of diplomatic resolution.”

Exactly when, in the long annals of international diplomacy, has the determination to “exhaust” all the alternatives to the use of military force ever brought a genocidal regime to its knees? That fact is, never.

This is why the French ambassador to the United Nations called the cease fire “a smoke screen” that would allow Syria’s Bashar al-Assad “to crush the Syrian civilians and the opposition.” Yes, the French, under the socialist leadership of Francois Hollande—the French!—are more clear-eyed about the moral dynamic of the Syrian conflict than the United States under President Barack Obama.

Mr. Kerry and the White House pretend that Mr. Assad has even the slightest incentive to compromise with the Syrian rebels. Their entire diplomatic strategy—their discredited demand that “Assad must go”—is based on a fantasy. After six months of relentless Russian air strikes on U.S.-backed rebel forces, the Syrian regime has regained the military advantage. This will likely include control over the city of Aleppo, considered the rebel capital of the revolution. More militarily secure than he has been in months, Mr. Assad can dictate the terms of any agreement.

“Regardless of whether a ceasefire takes hold, any political settlement would reflect the current balance of power, which favors Mr. Assad,” Fawas A Gerges, professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics, told the BBC; “Far from the beginning of the end, the Syrian conflict has entered a new phase in which the Assad regime has momentum on the battlefield and the negotiating table.”

Mr. Assad can thank America’s complicity with Mr. Putin’s strategic intervention on behalf of the Syrian government: For months the administration downplayed or ignored Russia’s infusion of fighter jets, advanced weapons, and military advisors. Russia’s rising influence in the region, along with that of the Iranians—whose terrorist activities supporting Mr. Assad earned them a seat at the negotiating table—represent yet another foreign policy debacle for Mr. Obama and the United States.

Expect more to come. According to the United Nations, the Syrian military and the forces of the Islamic State have put at grave risk the lives of over 487,000 people caught in the crossfire and cut off from humanitarian assistance. Mr. Kerry reportedly planned to have a “serious conversation” with the Russian foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, about allowing humanitarian aid to reach them. But, like a muffin facing a machete, Mr. Kerry has been repeatedly outflanked by his Russian counterpart.

This brings us back to the Kerry principle of “exhausting every option of diplomatic resolution,” regardless of the human consequences. Where does this risible idea come from?

Among other places, it can be traced to an anti-nuclear weapons document produced by the U.S. Catholic bishops in the 1980s. Called “the Challenge of Peace,” their pastoral letter redefined the just war tradition to address the threat of nuclear war. Not only must military action be a last resort, they argued, but “all peaceful alternatives must have been exhausted.”

No one with lived memories of Cold War tensions can fault the bishops for wanting to avoid a nuclear holocaust. But their pacifist distortion of just war doctrine—which never included an exhaustive search for non-military means to check lawless aggression—has unwittingly aided the agents of barbarism. By prioritizing peace over justice, the Doctrine of Exhaustive Diplomacy has helped to dull the conscience toward the victims of violence. It has empowered the purveyors of genocide.

“None of us are under any illusions,” Mr. Obama claimed last week about the Syrian cease-fire agreement. “But history would judge us harshly if we did not do our part in at least trying to end this terrible conflict with diplomacy.”

In truth, U.S. policy has been rooted in a string of illusions—fallacies about America’s role in the world, about the nature of radical Islam, about the resilience of the forces of evil. Meanwhile, history’s judgment of Mr. Obama’s role in perpetuating these falsehoods, and deepening the human tragedy of this conflict, is already being written.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

February 22, 2016

Washington Post: Before Donald Trump, the Sad History of When Christians Anointed Another Political Bully

This article was originally posted at The Washington Post.

Evangelical Christians have just delivered Donald Trump — the Republican presidential candidate most out of sync with their biblical values — a resounding victory in South Carolina. Of the 65 percent of Republican voters who identify as evangelicals, a third of them cast their ballot for Trump, more than any other candidate. Why?

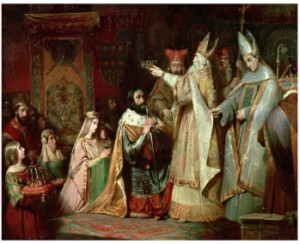

For roughly the same reason that a medieval pope, Leo III, anointed another political bully, Charles the Great, better known as Charlemagne. Put simply, they want a “protector in chief.” Facing a political culture increasingly hostile to their beliefs — and a government riding roughshod over their religious freedoms — evangelicals believe Mr. Trump will be the best guardian of their liberties.

“Trump is a fighter,” Mark Burns, pastor of the Greenville, S.C.-based Christian Television Network, told Fox News. “He is the one to fight for Christianity and for our conservative values we hold dear.”

That’s what Pope Leo believed about Charles, king of the Franks, when he personally crowned him king of the Holy Roman Empire on Christmas Day, 800 AD. Leo had become so unpopular in Rome that in 799 a band of assassins attacked him during a sacred procession and tried to cut out his eyes and tongue. Leo managed to escape and fled immediately to Charles, known as a defender of the church, and asked him to drive his enemies out of the city.

The king was happy to comply: On December 24, 800, he sent the pope back to Rome with an armed bodyguard, with himself marching “in full martial array” into the city. As Charles promised: “My task, assisted by divine piety, is everywhere to defend the Church of Christ.”

Thus occurred the spectacle of the leader of the Christian church, on Christmas Day, in the great Basilica of St. Peter, placing a crown on the head of the king — and prostrating himself in a Roman ritual resembling an act of emperor worship.

It didn’t matter that Charles had multiple wives and mistresses. Nor did it trouble the pontiff that he had a reputation for ruthlessness, earned during his wars against the Saxons, a Germanic tribe of pagan worshipers. In 782, in the Massacre of Verden, Charles ordered the execution of 4,500 prisoners, apparently for their refusal to convert to Christianity.

Here was a political leader who knew how to get things done, who could get tough with the church’s enemies, who could protect the empire from barbarian invaders. With the church on his side, he would restore Rome to its ancient glory. Sound familiar?

Thus evangelical voters joined other South Carolina Republicans in choosing Trump, by an 11 percent margin over his closest competitor, to “make America great again.” According to a recent Bloomberg Poll, they believe Trump is the candidate most likely to “keep their family safe” and “would be most feared by America’s enemies.”

Their own fears are causing them to abandon their principles. In America’s historic struggle to protect religious liberty, evangelicals fought hardest for a Bill of Rights that guaranteed equal justice — not only for themselves, but for unpopular religious minorities. They have been the loudest critics of discrimination based on religious identity.

Yet three-quarters of GOP primary voters in South Carolina — dominated by evangelicals — support Trump’s plan to block all Muslims from entering the United States.

One of the saddest chapters in the history of Christianity is how the courageous church of the martyrs became — with the help of the state — a fearful and persecuting church. Under Charlemagne, the punishment for refusing to be baptized into the Catholic faith was death. Conversion at the point of the sword became a cultural norm. In a letter to the pope, the new emperor explained his expectations of church and state:

“Our task is externally, with God’s help, to defend with our arms the holy Church of Christ against attacks by the heathen from any side and against devastation by the infidels and, internally, to strengthen the Church by the recognition of the Catholic faith. Your share, Most Holy Father, is to support our army with hands upraised to God, as did Moses in ancient days.”

Many evangelical voters seem ready to support Trump’s militancy, whatever form it takes, with hands upraised to heaven. They say they’re willing to endure their candidate’s “idiosyncrasies” because of his “authenticity.”

Never mind that he is an authentic egoist, or that he is unabashedly crude, proudly manipulative, and emotionally undisciplined. What has happened to the evangelical insistence that presidents be people of prayer, humility and integrity?

Like the medieval church, many American evangelicals expect to benefit from their anointing of Trump. Pope Leo’s constituency was granted access to political power and a privileged social status. They were given the opportunity to put their stamp on the empire’s laws and institutions.

But there was a cost for these privileges. Charlemagne wielded as much influence in church affairs as the pope himself. He appointed and deposed bishops, changed the church liturgy, wrote new rules for monastic life and dispatched agents to dismiss priests who seemed to lack education or piety.

A government that can shut down a mosque can shut down a church. A president who insults entire categories of human beings with impunity will not hesitate to attack any religious community that dares to criticize him.

After his coronation, Charlemagne declared himself “crowned by God, great and pacific emperor, governing the Roman Empire.” By consecrating a brutal political authority, the Catholic Church eventually gambled away its reputation — its spiritual vitality — for the thin gruel of a richer and more secure earthly kingdom.

In their embrace of Donald Trump, many evangelicals seem ready to do the same.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

February 15, 2016

Providence: The Decline of Freedom and the Obama Doctrine

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Although the leading Republican presidential candidates offer a sometimes vague and muddled mélange of views about American foreign policy, doubts about the Democratic Party’s ability to navigate the nation in a complex and dangerous world are legion. Skepticism is in order: think of Lyndon Johnson and the Vietnam War, Jimmy Carter and the Iranian Revolution and U.S. hostage crisis, or Bill Clinton and the Rwandan genocide and ethnic cleansings in Bosnia and Serbia.

Now consider—with fear and trembling—the foreign policy legacy of Barack Obama. In a mere seven years, Mr. Obama has presided over a flawed nuclear treaty with Iran, the meteoric rise of the Islamic State, the collapse of Libya and Yemen, the near-collapse of Iraq, Russian aggression in Ukraine, an increasingly belligerent North Korea, a genocidal civil war in Syria, and a refugee crisis on a scale not seen since the Second World War.

Now add one more metric of failure: in every year of Mr. Obama’s presidency, without exception, the cause of freedom has been in retreat around the world.

That is the conclusion of a Freedom House report, “Freedom in the World, 2016,” released last month. Based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the report measures political and civil liberties in 195 countries and 15 territories. Argentina, Bangladesh, China, Cuba, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, the Middle East, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Turkey—virtually every region of the world saw a decline in personal and political freedoms. “The world in 2015 was battered by overlapping crises,” the report concluded, “that contributed to the tenth consecutive year of decline in global freedom.”

Left-wing journals such as Slate, in summarizing the report, tried to muddy its findings with headlines like this: “America became a little less free last year.” The report’s methodology also has been criticized, but it’s hard to quibble with the overall conclusions: more people are experiencing serious human rights violations—from terrorist activities, repressive governments, and failing states—than ever before. Testifying last week before the Senate Intelligence Committee, James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence, described a “litany of doom” across the world stage: failing nation-states, the migration crisis in Europe, and so on.

What is striking is how many of these problems can be traced to the lack of strong American leadership. Though non-partisan in tone, the Freedom House report makes clear that the Obama administration has been complicit in the failures of the Western democracies to confront the human rights abuses and humanitarian crises enveloping much of the world. “Front and center was the democratic world’s inability to present a unified and credible strategy to end the murderous war in Syria and deal with the refugee crisis triggered by the conflict,” write Freedom House’s Arch Puddington and Tyler Roylance. “Whatever the underlying strength of their institutions, leading democracies betrayed a worrying lack of self-confidence and conviction during 2015.”

Here, in the end, is the epic tragedy of Mr. Obama’s foreign policy, a policy conceived and nurtured by his political progressivism. Mistaking self-confidence for arrogance, the president has telegraphed American weakness and withdrawal from strategic parts of the world. He has abandoned any conviction about America’s indispensable role in upholding international peace and security. As the Freedom House report suggests, the result is the weakening of civilizational confidence in the face of human rights atrocities. In regions such as the Middle East, the consequence is a humanitarian catastrophe, “a crisis of global proportions.”

In his first year in office Mr. Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize—not for any of his policies, but for his promises to make the world a more peaceful and humane place. Promises more facile and futile could hardly be imagined.

“Democracy, which must take account of the fears and apprehensions of the common people as dictatorships need not, cannot act in time,” observed Reinhold Niebuhr in Christianity and Power Politics. “It can act in time only if it has leaders who are willing and able to anticipate perils which the common man cannot see.” America and the civilized world, with a mix of hope and foreboding, wait for such leaders to emerge.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

February 5, 2016

Providence: The Troubled Conscience of Islam

This article was originally posted at Providence.

The butchery and barbarism committed under the banner of Islam—by groups such as the Islamic State, Boko Haram, and al-Shabaab—is finally generating a little soul-searching in the Muslim world. What faithful Muslims will ultimately discover from a spiritual inventory, though, remains to be seen.

Last month, for example, about 300 muftis, theologians, and scholars held a conference in Marrakesh, Morocco to address the problem of violence in Islamic states. The result is the Marrakesh Declaration, a 750-word document calling on Muslim countries to guarantee “full protection for the rights and liberties to all religious groups” and “confront all forms of religious bigotry.”

Participants cited as their inspiration the “Charter of Medina,” believed to have been established by the Prophet Muhammad after he fled Mecca for Medina (current day Saudi Arabia) to escape an assassination plot. Muhammad immediately faced a religiously diverse society, including a significant Jewish population, and designed a kind of social contract to accommodate them. The document promises, among other things, that “Jews who follow the Believers will be helped and will be treated with equality.”

Abdallah bin Bayyah, the 80-year-old United Arab Emirates sheik who led the “call to action” at the conference, views the Medina charter as the basis for citizenship in a modern, pluralistic state. “This document is the foundation for an inclusive multicultural, multi-religious society,” he said, “in which all individuals enjoy the same rights and shoulder the same responsibilities.”

That’s a contestable claim, of course, since Jews would soon be expelled from Medina and non-Muslims would never achieve equal rights and protections under the law. Although the Charter of Medina introduced the idea of the dhimmi, a compact guaranteeing security for non-Muslims, the Qur’an applies the term to groups subjugated by Islamic conquerors. “The price of their preservation,” writes C.E. Bosworth in Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire, “is to be reduction to a humiliating status in society as second-class citizens.”

This has been the historical pattern of Islam, not only in its confrontation with the West, but in its expansion throughout the world—a fact ignored in the declaration and denied outright by its framers. “The accusation that Islam oppresses minorities,” Bin Bayyah told the conferees, “has no basis in sacred law or in history.”

The statement would be laughable if the record of human misery in the name of Islam—ancient and modern—were not so voluminous. Just take the latest example: The Islamic State openly justifies the kidnapping, rape, and enslavement of young girls as a custom sanctioned under Sharia law. At least 5,000 Yazidis from Syria and Iraq have reportedly fallen into the hands of the jihadists—with a noticeable lack of outrage among leading imams.

Defenders of Islamic history, including President Barack Obama, are quick to recall the bigotry and violence carried out under the guise of Christianity. It is, in many respects, a dark and tortured history. But this misses the crucial point: Christians in the West did not whitewash the sins of the Christian church, but grieved over the church’s failure to uphold its deepest religious ideals. They engaged in an intensive, centuries-long debate about the nature of the Christian faith and its relationship to political authority.

Only then were religious thinkers ready to envision a pluralistic state that guaranteed equal justice to people of all faiths. Only then could they imagine a society that enshrined, in law and custom, the principle of religious freedom for all its citizens. As John Locke put in his Letter Concerning Toleration (1689): “The sum of all we drive at, is that every man enjoy the same rights that are granted to others.”

The crisis in modern Islam is that its leaders steadfastly refuse to confront their violent past. Thus there has been no serious and prolonged debate about why so much of the Islamic world remains hostile to democratic values and universal human rights.

Thanks to political correctness, Muslims are helped in their evasion by well-meaning Westerners, including the American president. In his speech this week to Muslims at a Baltimore mosque, Mr. Obama tried to counter the anti-Islamic venom that has degraded the presidential campaign, and to reassure Muslims that they are a vital part of the American story, a worthy enough goal. “This is a struggle between the peace-loving, overwhelming majority of Muslims around the world and a radical, tiny minority,” the president said. “We can’t suggest that Islam itself is at the root of the problem. That betrays our values.”

The real betrayal—a betrayal of reason and conscience—is the suggestion that Islam has nothing to do with the culture of oppression and rage that is enveloping the Muslim world. Some of those who gathered at Marrakesh know better. As their declaration put it: “It is unconscionable to employ religion for the purpose of aggressing upon the rights of religious minorities in Muslim countries.”

As the history of religious freedom in the West makes clear, the awakened conscience is a prerequisite to a reformation.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

February 1, 2016

CapX: Trump, Sanders, and the Ghost of Mussolini

This article was originally posted at CapX.

For those still trying understand the political rise of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, consider an insight from Eric Fromm’s 1941 book, Escape from Freedom that a sense of powerlessness created a willingness among ordinary people to surrender personal responsibility in order to regain a sense of control over their lives. Published when totalitarian ideologies were enveloping Europe and Asia, the book offers a psychological study into the malaise of the modern era.

“The first mechanism of escape from freedom,” Fromm wrote, “is the tendency to give up the independence of one’s own individual self and to fuse one’s self with somebody or something outside of oneself in order to acquire the strength which the individual self is lacking.” Welcome to the Sanders and Trump presidential campaigns. Their success thus far suggests that Fromm’s thesis is painfully relevant to our political moment.

On the far left we have Sanders, a self-proclaimed “democratic socialist” who promises an expansion of Medicare, universal child care and pre-K, free college tuition, paid sick leave, and family leave benefits for all workers—and that’s just for starters. The cost would be in the trillions of dollars. As Sanders confessed to reporters in Iowa: “I think there are a lot people, when they hear the word ‘socialist,’ get very nervous.”

The history of socialist schemes, in fact, should make any rational person extremely nervous. Wherever it has been tried, socialism has dissolved the meaning of democratic self-government. Socialist regimes transform citizens—the lifeblood of civil society—into wards of the state. A government intrusive enough to provide for every social need guarantees the decline of personal responsibility and individual freedom. Just ask the East Europeans who lived through the Cold War.

On the far right we have Trump, the supposed defender of American capitalism, who nonetheless has built his real-estate and casino empires by engaging in crony capitalism and trampling the private property rights of anyone who gets in his way. Trump promises to solve America’s illegal immigration crisis by building a massive wall and getting Mexico to pay for it. He will keep America safe from terrorist attack by temporarily banning any Muslim from entering the country. He will end the U.S. trade deficit with China by making businesses do his bidding. “We’re going to bring back the American dream,” he promises. “After all, wealth funds our freedom.”

Here are simple and reassuring answers to immensely complex problems. Yet the Trump agenda amounts to a new version of protectionism, nativism, and isolationism. All of these policies have been tried before—and have failed to produce prosperity or to safeguard liberty.

An angry and disillusioned electorate is propelling the Sanders and Trump campaigns, just as anger and disillusionment produced demagogues in the aftermath of World War I. It was no accident that fascism began in Italy, a society that seemed to be in tatters—economically, socially, and spiritually. The Great War left the Italians politically divided and mistrustful. The parliamentary government was corrupt and ineffective, the monarchy unpopular.

Enter Benito Mussolini, who after seizing power in 1922, became the first European leader to dispense with multi-party democracy. “The century of democracy is over,” he proclaimed. Mussolini vowed to close the gap between rich and poor, restore Italian greatness, and replace democratic weakness with totalitarian strength. “The Fascist State…has limited useless or harmful liberties and has preserved those that are essential,” he wrote. “It cannot be the individual who decides in this matter, but only the State.”

Whether from the political left or political right, Mussolini’s ghost seems to be haunting the American electorate. Demagogues cannot thrive without disillusionment, and disillusionment has become the watchword for our troubled times. Our escape from freedom is well underway.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

January 12, 2016

Providence: Neutrality in the Face of Terror

This article was originally posted at Providence.

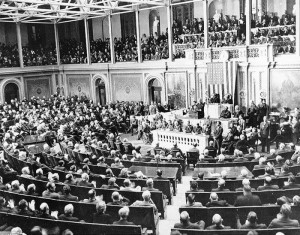

Whatever the actual “State of the Union,” as proclaimed by Franklin Roosevelt in his January 3, 1936 address to Congress, the president’s state of mind was a perplexing mix of admission, obfuscation, and denial. If President Obama’s speechwriters are casting about for models of statecraft in the age of terror, they should look elsewhere.

With the Depression in full swing—despite three years of unprecedented government intervention in the economy—FDR hoped to focus his speech on domestic concerns. But the real world, the world of terror and totalitarianism, had intervened.

Casting an eye on all of East Asia, Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, and then withdrew from the League of Nations two years later. The same year, in 1933, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party swept into power promising to tear up the Treaty of Versailles. In 1934 Japan renounced the London Naval Treaty, which had limited the size of its fleet. In March 1935, Hitler announced the establishment of a new German air force, the Luftwaffe, and reinstituted conscription into the Armed Forces, an open violation of the Versailles Treaty. In September 1935, Germany imposed the first raft of Nuremberg Laws, revoking the civil rights of all Jews and prohibiting them from marrying non-Jews. In October of the same year, Italy’s Benito Mussolini sent 100,000 troops into Ethiopia, converting the African nation into an Italian colony.

Thus FDR was forced to admit that the world, especially Europe and Asia, had changed since his arrival in office in 1933:

Not only have peace and good-will among men grown more remote in those areas of the earth during this period, but a point has been reached where the people of the Americas must take cognizance of growing ill-will, of marked trends toward aggression, of increasing armaments, of shortening tempers—a situation which has in it many of the elements that lead to the tragedy of general war.

Slippery phrases like “trends toward aggression” and “shortening tempers” were typical of Mr. Roosevelt during this period. So it’s significant that he went on to warn about the possibility of war, and to criticize the “fantastic conception” that the aggressor nations hoped to make the rest of the world subject to their rule:

I realize that I have emphasized to you the gravity of the situation which confronts the people of the world. This emphasis is justified because of its importance to civilization and therefore to the United States. Peace is jeopardized by the few and not by the many. Peace is threatened by those who seek selfish power.

Mr. Roosevelt said nothing about the fascist doctrines of these aggressor states, their totalitarian vision, or their racist ideology. There was no mention of the fierce anti-Semitism of the Nazi Party. The American people were told only that the dictators “seek selfish power.” Nevertheless, the president warned that global peace was threatened by their actions, and that this represented a threat to civilization itself.

What, then, would be America’s response to these renegade powers confronting the democratic West?

The United States, the president said, would continue to exert “our moral influence against repression, against intolerance, against autocracy,” while promoting freedom of expression, equality before the law, and religious tolerance. Moral influence—meaning diplomacy and perhaps economic pressure—was the proper instrument of persuasion.

But what, exactly, would be America’s political and military posture toward international lawlessness and aggression?

We hope that we are not again at the threshold of such an era. But if face it we must, then the United States and the rest of the Americas can play but one role: through a well-ordered neutrality to do naught to encourage the contest, through adequate defense to save ourselves from embroilment and attack, and through example and all legitimate encouragement and assistance to persuade other Nations to return to the ways of peace and good-will.

By “well-ordered neutrality” Mr. Roosevelt had in mind the 1935 U.S. Neutrality Act, legislation that he enthusiastically signed (and would expand upon in 1936). The law authorized the president to deny American businesses the right to sell arms or munitions to “belligerent nations.” For the first time in American foreign policy, all sides in a conflict—no matter what the cause—were to be treated as “belligerents,” that is, potential adversaries of the United States.

How did this amoral reversal of U.S. policy come about? Mr. Roosevelt, slavishly in step with American public opinion, was in an isolationist mood. In 1935 he was also busy rallying support for his “Second New Deal,” and he needed the votes of isolationists in Congress to get it. Historian Paul Johnson calls the Neutrality Acts “a complete departure from previous American policy, which had always permitted the U.S. government to make moral distinctions between participants in foreign wars.”

Hence the staggering conceptual muddle of Mr. Roosevelt’s foreign policy: whatever occurs outside of America’s hemisphere does not concern Americans—even if civilization itself is hanging in the balance. Nevertheless, FDR boasted of “a clear policy,” in which Washington adopted a “twofold neutrality” toward “any and all Nations which engage in wars” that are not of “immediate concern” to the United States.

The policy was quite clear—especially to America’s enemies.

Britain’s ambassador to Berlin, Sir Eric Phipps, reported back to London the Nazi response to Mr. Roosevelt’s State of the Union speech. The president’s criticism of the dictators “carried no weight with Hitler.” What caught the Fuhrer’s attention, he said, was “Roosevelt’s renewed declaration that America would in future remain aloof and observe neutrality in European affairs.” As Adolf Hitler reportedly remarked: “There has been no development during recent years more welcome than this.”

The United States promises to remain on the sidelines as a totalitarian juggernaut advances against the West—yes, no development could have been more welcome in Berlin than this.

What, then, is the State of the Union eighty years hence? Whatever President Obama and his swooning entourage may claim, now would be a good time to reckon with the consequences of America’s self-imposed neutrality as the forces of barbarism renew their ancient quest.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

January 8, 2016

Providence: China’s Frankenstein Monster, Unleashed

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Every once in a while the left-wing elites at The New York Times experience a spasm of moral clarity. “North Korea stains the record of President Obama, who took office promising to make ridding the world of nuclear weapons a priority,” its editors sheepishly admitted this week, following North Korea’s claim to testing a hydrogen bomb. “Its actions are a humiliation for President Xi Jinping of China, North Korea’s only ally, largest trading partner and economic lifeline for food and oil.”

Right on both counts.

North Korea’s belligerence has bedeviled both Republican and Democratic administrations. President Clinton’s naive 1994 treaty to freeze North Korea’s nuclear program merely gave the regime diplomatic cover to develop it. During the Bush administration, North Korea withdrew from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and conducted its first nuclear weapons test.

Yet Pyongyang has ratcheted up its aggressive behavior during the Obama years. Here’s a sampling: In 2009 North Korea staged its second illegal nuclear test. In 2010 the regime sank a South Korean warship, in an unprovoked attack, killing 46 seamen. In 2012 the government tested a long-range Taepodong-2 missile; the test failed. Later that year, it announced it had missiles that could hit the U.S. mainland. In 2013 the regime staged its third nuclear test, said to be more powerful than the 2009 test. Later that year, over the course of a weekend, North Korea launched four short-range missiles. In 2014 the regime test-fired two medium-range ballistic missiles for the first time in five years.

The regime’s latest act of nuclear brinkmanship has triggered the predictable round of international criticism. Even White House press secretary Josh Earnest, who has a complicated relationship with the truth, confessed: “The fact that we see provocative acts from North Korea is an indication we are not getting the results we’d like to see yet.”

The Chinese seem increasingly frustrated with North Korean behavior. China “firmly opposes” the nuclear test, according to Hua Chunying, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry. “China is steadfast in its position that the Korean Peninsula should be denuclearized and nuclear proliferation should be prevented to maintain peace and stability in Northeast Asia…We strongly urge the DPRK to honor its commitment to denuclearization, and to cease any action that may deteriorate the situation.”

But that’s not going to happen—thanks largely to China, North Korea’s perennial patron.

Beijing continues its role as the geo-political savior of North Korea, providing the regime with much of its food, arms, and energy. According to UNICEF, a quarter of its population—about six million people—do not have enough to eat. Without Chinese support, the economically decrepit North Korea would be pushed over the brink of starvation.

There are deep, historic ties between these two communist states. When, in 1950, North Korea invaded the South (the Republic of Korea), it was driven back by American and U.N. forces. As U.S. troops pushed into North Korea, Beijing came to the rescue: the Chinese launched a massive, surprise offensive that kept the North Korean military alive. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers perished in the Korean War, including the son of Chinese leader Mao Zedong, killed in a U.N. napalm strike and buried in Pyongyang. The leaders in Beijing also crave stability, and have viewed North Korea as a buffer between China and U.S. troops stationed in South Korea and Japan.

But the regime of Kim Jon Un, and his psychotic cult of personality, is anything but stable. China has propped up its Frankenstein monster for nearly seventy years, and can no longer control it.

What force on earth could change North Korea’s behavior, or cause it to give up its nuclear program? Will China finally act to bring the monster to heel? The oracles at The New York Times, in the same editorial, offer this counsel: “China is understandably concerned that really tough economic penalties would cause people to flee North Korea for China,” they write. “But even smaller gestures like preventing Mr. Kim and his friends from importing whiskey and other luxury goods might have an impact.”

No more whiskey and caviar—yes, this will bring the nuclear-armed narcissist to his knees. As suggested above, the editors at the Times exhibited a spasm of moral clarity by chastising the White House and China for their failed policies toward Pyongyang. The thing about spasms, though, is that they don’t last very long.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

January 4, 2016

Providence: Christian Realism and US Foreign Policy

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Seventy-five years ago, while America slept, Western Civilization was fighting for its life.

In September of 1940, after occupying and enslaving most of continental Europe in less than a year, Hitler’s Germany turned its gaze north, across the English Channel. Beginning on September 7, the Luftwaffe unleashed a storm of death and destruction on the city of London: the Blitz. The first round of bombing raids lasted fifty-seven consecutive nights. CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow was there: “I’ve seen some horrible sights in this city during these days and nights, but not once have I heard man, woman, or child suggest that Britain should throw in her hand.”

Everyone in Britain, including Prime Minister Winston Churchill, expected a Nazi invasion at any moment. And nearly everyone in the United States, including President Franklin Roosevelt, tried desperately to put Britain’s existential struggle out of their minds. “I’ll say it again, and again,” vowed FDR during his 1940 re-election campaign. “Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.”

We might expect this kind of talk from dissembling politicians, but what about the nation’s Christian leadership: its theologians, pastors, writers, and public intellectuals? The lamentable fact is that most failed to grasp the nature of Hitlerism; they refused to contemplate the practical consequences of a complete Nazi triumph over Europe. Instead, many insisted that the “ethics of Jesus” demanded a U.S. foreign policy of isolationism, pacifism, and national repentance.

“Can military force do much against soul force which folds its arms and bides its day?” asked Albert Palmer, president of the Chicago Theological Seminary. “Without military opposition the Hitlers wither away.” Harry Emerson Fosdick, pastor of New York’s Riverside Baptist Church and one of the most influential preachers of his day, was unmoved by the fate of millions already under Nazi occupation. “I can never use my Christian ministry in the support and sanction of war,” he wrote in January 1941. “My personal judgment is that for the United States to become a belligerent in this conflict would be a colossal and futile disaster.” Charles Clayton Morrison, editor of the prestigious Christian Century, denounced American participation in the conflict as “a war for imperialism,” as hateful a prospect as a Nazi victory. “For the United States to make a fateful decision to enter this war on the mistaken and irrational assumption that it is a war for the preservation of anything good in civilization will be the supreme tragedy of our history.”

By the 1920s and 30s, American Christianity—especially its liberal wing—shared the same mental outlook as that of political progressivism. In politics, both reacted to the cataclysm of the First World War determined to make international peace their supreme goal, whatever the cost. In matters of religion, both embraced a spirit of disbelief and evasion: a reluctance to admit the stubbornness and pervasiveness of human evil.

“In this liberalism there is little understanding of the depth to which human malevolence may sink and the heights to which malignant power may rise,” wrote Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr in Christianity and Power Politics (1940). “Some easy and vapid escape is sought from the terrors and woes of a tragic era.”

This frame of mind has returned with a vengeance in the post-9/11 era, fueled by the costly and inconclusive wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Its motive force, though, is a blinkered vision of the Christian gospel that has unwittingly debased the Christian conscience. At the very moment when the political and religious ideals of the West are threatened by new forms of terror and totalitarianism, much of the Protestant Christian church today lacks the intellectual and moral resources to fight back.

Consider the reaction of leading “progressive” Protestant ministers to the 9/11 attacks and the rise of radical Islamic extremism. The Rev. Tony Campolo, the self-described “Prophet of Red Letter Christianity,” has focused his righteous rage on American foreign policy. He compares U.S. military action against Islamic militants to the campaign of beheadings launched by the Islamic State (ISIS) against alleged infidels. “What can we do to stop this cycle of violence?” he asks. His answer: “What if President Bush and President Obama stood together at the rostrum of the U.N. General Assembly and did the biblical thing? What if, on behalf of the American people, they repented of what our nation has done?”

Soon after the 9/11 attacks, Jim Wallis and his Sojourners magazine produced a manifesto called “Confessing Christ in a World of Violence.” A critique of the U.S.-led “war on terror,” the document was signed by scores of theology professors, ethicists and church leaders. Its signatories sought to soften what they called the “crude distinctions” being made between radical Islamic jihad and Western democracy. They thus offered a misappropriation of Solzhenitsyn: “The distinction between good and evil does not run between one nation and another, or one group and another,” the petition read. “It runs straight through every human heart.” More recently, Wallis finds the solution to ISIS barbarism in tackling the “root causes” of terrorism, which are economic and political in nature. “Terrorism is always built on grievances—real and perceived—that are used to recruit for and perpetuate its ideology and violence,” he writes. “So addressing those grievances and correcting course along the way is essential to defeating terrorism.”

Stanley Hauerwas, professor of ethics at Duke University, delivered a jeremiad against the United States, even as human remains were being recovered from Ground Zero. He saw a terrible day of reckoning ahead: “I think that when America isn’t able to rule the world, that people will exact some very strong judgments against America—and I think we will well deserve it.” A look at his latest book, War and the American Difference, suggests that world events have left his views undisturbed. Hauerwas rejects U.S. military action in the Middle East, even to prevent crimes against humanity or genocide. “If the U.S. intervenes, we just reinforce the presumption, which is true, that we’re an imperial power.”

And on it goes. Religious progressives are not mistaken when they discover in the ministry of Jesus a life devoted to the love of neighbor: the unconditional love of God. Nor are they wrong to see in Jesus the quintessential peacemaker: the Prince of Peace. Yet their political vision is based entirely upon the principle of non-violence. Their politics, in all its particulars, is guided by one rule, “the law of love.”

The fatal problem with this view is that historic Christianity—especially Protestant Christianity—has never reduced the gospel to these elements. The cross of Christ cannot be comprehended without an awareness of the depth of human guilt and the power of radical evil. “The gospel is something more than the law of love. The gospel deals with the fact that men violate the law of love,” wrote Niebuhr in “Why the Christian Church is Not Pacifist.” “The gospel presents Christ as the pledge and revelation of God’s mercy which finds man in his rebellion and overcomes his sin.”

Like no other American theologian of the twentieth century, Reinhold Niebuhr exposed the assumptions of progressive Christianity that helped to create a mood of political ambivalence and isolation in an age of global terror. Niebuhr’s political theology—what became known as “Christian realism”—sought a more biblical view of how the Christian citizen can live responsibly within a civilization in crisis. During the 1930s and 40s, through his books, articles, and the magazine he founded and edited, Christianity and Crisis, Niebuhr reminded his generation that Protestant Christianity possessed unique resources to confront the problems and perplexities of the modern age.

We need to recover something of the Christian realism that proved so prescient in an era of theological confusion. As Niebuhr argued, contemporary historical events confirm the Reformation emphasis on the persistence of sin at every level of moral achievement; there is no way to fully escape the corrupting influence of power in any political act. To believe otherwise is to imagine that politics can transcend these earthly realities if only “the ethics of Jesus” would shape our priorities and methods.

No amount of Bible citations, Niebuhr explained, can conceal the humanistic assumptions behind this effort:

We have, in other words, reinterpreted the Christian gospel in terms of the Renaissance faith in man…We have interpreted world history as a gradual ascent to the Kingdom of God which waits for final triumph only upon the willingness of Christians to ‘take Christ seriously.’ There is nothing in Christ’s own teachings…to justify this interpretation of world history. In the whole of the New Testament, Gospels and Epistles alike, there is only one interpretation of world history. That pictures history as moving toward a climax in which both Christ and anti-Christ are revealed.

Progressive Christianity, whatever its merits, bases its politics on a fundamentally flawed understanding of the human predicament. By insisting on political outcomes akin to the vision of life held out in the Sermon on the Mount, it promotes a foreign policy largely detached from political reality.

A foreign policy rooted in Christian realism, by contrast, begins with a sober view of the exercise of power. Enforcing justice, punishing wrongdoing, building democratic institutions—all of this is exceedingly difficult work, a truism as easily forgotten by political conservatives as it is by progressives. One of the most deeply mistaken ideas surrounding the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, for example, was that liberal democracies would emerge organically, almost inevitably, out of the ashes of decades of repression and war.

In The Case for Democracy, former Soviet dissident Natan Sharansky argued that the democratic revolutions which toppled the Soviet Union depended on three key elements: enslaved people who yearned to be free, leaders outside who believed they could be, and policies that linked the world community to the regime’s treatment of its own people. The book was mandatory reading in the Bush White House. “It will work anywhere around the world,” Sharansky wrote, “including in the Arab world.”

How could that be true? History—especially recent history—reminds us that there is no formula to assure a transformation from tyranny to democratic self-government.

The Protestant tradition, which emerged as a reaction against Catholicism’s doctrine of perfectionism, is well-equipped to defend against this myth of progress. “The political life of man,” wrote Niebuhr, “must constantly steer between the Scylla of anarchy and the Charybdis of tyranny.” It is for good reason that the American Founders, armed with a strong dose of Protestant realism, worried that factions—especially those fueled by sectarian hatreds—would prove fatal to national unity. Thus Madison’s insight in The Federalist: “Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.”

Second, the Christian realist insists on an honest assessment of the threats to international peace and security. Let’s take the challenge of radical Islamic jihad. The claims and ambitions of al Qaeda, ISIS, and other terrorist groups cannot be wished away. Unlike the national security documents adopted by the Obama administration, a realistic National Security Strategy would identify the religious sources of the terrorist ideology that threatens the United States and its allies. Evasive and generic references to “terrorists” and “extremists” obscure the nature of the problem.

Even the editors at The New Republic, hardly a source of Christian realist thinking, nevertheless got close to the mark in an editorial shortly after the 9/11 attacks. “No, it was not Islam that took the towers down. But it was not Episcopalianism either,” they wrote. “The terrorists are waging a war of ideas, and the ideas upon which they are acting are ideas in the Islamic tradition…There are those who wish to deny the religious character of Al Qaeda’s violence, so as to transform bin Ladenism into another variety of anti-colonial protest.”

Meanwhile, Protestantism, which has always cared deeply about theology—Luther’s Reformation was, at its core, a spiritual campaign—has the necessary tools to come even closer to the mark. By placing the authority of the Bible above any individual or institution, Protestants are less restrained than other faith traditions in exposing the pretensions of political and religious leaders. They are better equipped to resist political correctness in any form.

For the Christian realist, the horrific acts of barbarism committed in the pursuit of a spiritual utopia are not the result of “grievances” with Western society. Rather, they are the latest expression of an ancient malignancy—the Will to Power—clothed in the robes and symbols of religion. C.S Lewis, in another context, described this will as the “ruthless, sleepless, unsmiling concentration upon self, which is the mark of Hell.” The demonic vision of radical Islam is not a force that can be bribed, appeased, accommodated, contained, or placated into submission. As Taliban leader Mullah Akhtar Muhammad Mansour recently described his objectives in Afghanistan: “the jihad will continue until there is an Islamic system.” Claims of a “peace process,” he said, are merely “the words of the enemies.”

Third, a foreign policy based on Christian realism makes the defense of Western political and religious ideals an overarching priority. Rooted in their understanding of divine grace, Protestant reformers delivered a withering critique of the entire legalistic project that had become “Christendom.” They laid the foundation for our liberal democratic order. Government by consent, the separation of powers, a constitution based on natural rights and human equality, freedom of conscience, free speech, freedom of assembly—all of these achievements are inconceivable without the moral capital and spiritual insights of evangelical Christianity. They are the defining features of American exceptionalism.

Yet religious progressives, when obsessed with America’s shortcomings, lose sight of these accomplishments. They find it hard to make moral distinctions between American democracy and even the most loathsome and oppressive dictatorships. Thus the lament of John Haynes Holmes, a New York City minister and chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union, so typical of liberal theologians in the 1940s: “Our sins have found us out, that’s all,” he concluded. “If Hitler triumphs, it will be as the punishment for our transgressions.”

Here is the spirit of the embittered utopian, alive and well in progressive Christianity. Recall the disturbing refrain of the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, President Obama’s ex-favorite pastor, in the wake of the 9/11 attack: “America’s chickens are coming home to roost…God damn America! God damn America!” Niebuhr and his fellow Christian realists would have none of it: “When the mind is not confused by utopian illusions,” he wrote, “it is not difficult to recognize genuine achievements of justice, and to feel under obligation to defend them against the threats of tyranny and the negation of justice.”

A one-time socialist candidate for Congress, Niebuhr was not blind to the deep injustices—economic and racial—in American society. Yet he could no longer abide the morally debased reasoning of his fellow socialists in response to fascist aggression; he resigned from the party. He then turned his mind toward combating the same moral confusion afflicting liberal Protestantism:

We believe the task of defending the rich inheritance of our civilization to be an imperative one, however much we might desire that our social system were more worthy of defense… We do not find it particularly impressive to celebrate one’s sensitive conscience by enlarging upon all the well-known evils of our western world and equating them with the evils of the totalitarian systems. It is just as important for Christians to be discriminating in their judgments, as for them to recognize the element of sin in all their endeavors.

The Christian realist can never equate American democratic values with gospel morality: this opens the door to Christian nationalism, a perversion of the faith. But a posture of cynicism toward the United States and the West is no less a corruption. Social perfection at home is not required before attempting to check aggression and punish injustice abroad.

It is at this point where Christian progressives fail most conspicuously in their stated objective: to demonstrate the love of Christ to their neighbor. Perhaps the most shameful behavior of American Christians during the Second World War was their practical indifference to the millions of victims of Nazism.

From 1938 to 1941, for example, American Protestant groups issued no fewer than 50 statements about how to achieve a just and durable peace. None offered a plan to rescue Jews from the anti-Semitic hatreds unleashed by the Nazis. There was lots of talk about debt relief and economic assistance. Yet barely a handful of these manifestos argued that the defeat of Nazism was essential to international justice.

Their progressive progeny are not hard to identify. Duke’s Stanley Hauerwas speaks for many when he denies the need for a foreign policy that could thwart the depraved ambitions of terrorist groups or rogue regimes. “My only response is I do not have a foreign policy. I have something better—a church constituted by people who would rather die than kill.”

What are we to make of this “theology of love”? The de facto pacifism of progressive Christianity presents us with a conscience insulated from human suffering. It is a conscience content to ignore the neighbor in crisis—whether he’s the Jew marched to the gas chambers at Auschwitz, the Tutsi villagers hacked to death in Rwanda, the girls forced into sexual slavery by Boko Haram, the families hunted down and executed by ISIS, the gays rounded up and tossed from rooftops, or the Syrian refugees facing starvation or extinction because of their faith.

Even secular political leaders at the United Nations have endorsed a doctrine known as the “responsibility to protect” when civilian populations become the object of genocide or crimes against humanity. At the moment when fresh thinking about the Christian just war tradition is desperately needed, religious progressives have abandoned the concept altogether. “Thus the Christian ideal of love has degenerated into a lovelessness which cuts itself off from a sorrowing and suffering world,” wrote Niebuhr. “Love is made to mean not pity and sympathy or responsibility for the weal and woe of others, it becomes merely the abstract and negative perfection of peace in a warring world.”

In this, religious progressives succumb to an old temptation. They allow their hatred of war to blot out all other virtues and obligations. But the historic and orthodox Christian church has never viewed peace—peace at any cost—as the highest good. Such a peace always ends in a preference for tyranny. It always adds to the catalogue of human suffering.

For the person whose life is threatened by violence, servitude, or death, the Christian conscience summons a full range of obligations: empathy, courage, sacrifice, and a determination to protect the neighbor from great evil. Protestants have long appreciated the distinct role of government in helping to carry out the last of these obligations. In his tract aimed at political leaders, On Secular Authority (1523), Martin Luther explained that the sword of the State “is a very great benefit and necessary to the whole world, to preserve peace, to punish sin and to prevent evil.”

A just peace may be the final result of these pursuits, God willing. But if peace is made the supreme goal, if it consumes all other obligations, it becomes an idol—and a snare to the statesman as well as the saint.

Christian realism sets itself squarely against this idol, and against the utopian assumptions that give it life. The post-9/11 era has exposed the resilience of the utopian idea in both politics and religion; it continues to exert a powerful hold on the mind of modern liberalism. Unchecked, it represents a threat to the health and even survival of liberal democracy in America and the West.

Where do we begin in confronting this outlook? We need to recover the wisdom and resolve of those who recognized the supreme malevolence of their own day. Only a handful of religious leaders realized the demons that Nazism had let loose in the world. Few could imagine the sacrifices required to meet them. And fewer still dared to predict the consequences of shrinking back from the duties assigned to America, Great Britain and their allies.

The Christians who did so sought to retrieve a more biblical understanding of the gospel as the foundation for their politics. They argued that the “gentleness” of Jesus was not the full and final revelation of the character of God. They insisted that both the Old and the New Testament took the wrath of God as well as the mercy of God seriously. “The divine mercy, apprehended by Christian faith in the life and death of Christ, is not some simple kindness indifferent to good and evil,” wrote Niebuhr. “The whole point of the Christian doctrine of Atonement is that God cannot be merciful without fulfilling within himself, and on man’s behalf, the requirements of divine justice.”

The biblical answer to the problem of evil in human history, Christ’s death and resurrection, cannot separate justice from mercy. Thus the way of Jesus—what C.S. Lewis once described as “terror and comfort intertwined”—dispels our utopian illusions. His gospel renders as futile our facile efforts to create a society based on “love” while failing to reckon with the negation of love which threatens every human endeavor.

Here there is no place for sentimental Christianity, either in our pulpits or our politics. Here is a road less travelled. And yet along this road lies our best hope: not for the immediate arrival of the kingdom of heaven, but for a greater measure of peace and justice within, and among, the nations of the earth.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

December 30, 2015

Providence: End of the European Project?

This article was originally posted at Providence.

In November 2013, tens of thousands of Ukrainians filled the central square of Kiev to protest President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to reject an “association agreement” with the European Union. Waving European Union flags, the crowds chanted slogans demanding to be part of the West. As Liudmyla Babych, a saleswoman from Kiev, told The Guardian: “We want to be in Europe.”

There are good reasons to want to be part of the European community. Like no other multi-ethnic region of the world, the Europeans can boast strong commercial ties, free-market economies, a system of international law over the use of force, and a shared commitment to liberal democratic values. A war among the European states is nearly unimaginable, an achievement of great importance to the United States.

Nevertheless, two years after the Ukrainian revolution that eventually ousted its thuggish president, enthusiasm for the European project has reached a new low—even among Europeans.

There are of course the ongoing economic woes: the Greek debt debacle remains unresolved, and most European economies are struggling with high unemployment and low growth rates relative to the United States. The gross domestic product of the 19 countries sharing the euro currency is smaller now than it was before the 2008 economic meltdown.

There is the rise of the Islamic State and terrorist violence that has exposed the vulnerability of Europe’s unprecedented achievement: its open internal borders among its 28-member states. Twice in less than a year, terrorist cells—moving freely across Europe—struck Paris with devastating results. “France is at war,” declared Socialist President François Hollande. The French government is trying to amend the constitution to allow the president to suspend civil liberties without parliamentary approval. Open borders mean a unique openness to Islamist terror.

There is the Syrian civil war, which has created a refugee crisis that has sent shock waves throughout European capitals. From January to October of this year, over 1.2 million migrants entered the European Union illegally. The influx of these individuals, mostly Muslim, is stoking xenophobia, as we well as legitimate worries about the compatibility of Islam with liberal democracy. Although Germany’s Angela Merkel had pledged to open the country to asylum-seekers, a public backlash elicited a promise to “reduce the number of refugees appreciably” before Germany was “overwhelmed in the long run.” Countries such as Hungary and Austria have built fences to keep them out, and most EU states have tightened their border controls.

And, of course, there is Ukraine, which has suffered the Russian takeover of its Crimean Peninsula and remains engaged in a fierce battle with Russian-backed separatists in its eastern region. Although EU states have imposed sanctions on Moscow, they have done nothing to hinder Russian designs in Ukraine. Meanwhile, some European leaders appear eager to cooperate with Vladimir Putin to help resolve the Syrian conflict.

All of these challenges have exposed the fundamental weakness of the entire European project—namely, its inability to muster the political leadership required for effective action. This vulnerability was hinted at in a lengthy essay by Jim Yardley in The New York Times. “Every elected national leader knows there is no political mileage to try to lead on European issues or push for more integration,” Frederick Erixon, director of the European Center for International Political Economy, told the Times. “The European idea is now a rapidly declining trend.”

The fact is that the European Union—with its generous welfare schemes, rejection of nationalist impulses, marginal military expenditures, and pacifist foreign policy—could only work in a world without crises. In other words, it could never succeed in the world as we actually find it. “It might never have been realistic to envision a United States of Europe,” concedes Mr. Yardley. Not realistic at all, in fact—and yet the reasons for its failures still elude liberal elites, especially those in the United States who want America to become more like Europe.

Whether from historical amnesia or ideological blindness, Mr. Yardley appears not to grasp that Europe owes much of its political and economic success to the United States. He notes that the European Union has built a stable and diverse economy, supported by democratic ideals. He explains that Europe prides itself on being a Western superpower “without the bellicosity or laissez-faire hardheartedness of the United States.” Yet Mr. Yardley fails to mention that few of Europe’s achievements would have been possible without American leadership: its moral seriousness, economic dynamism, the success of its democratic institutions, and the projection of its military power.

Robert Kagan, author and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has correctly observed that the United States created—and has sustained—the architecture for international security that made the European project conceivable. “Europe’s rejection of power politics and its devaluing of military force as a tool of international relations have depended on the presence of American military forces on European soil,” writes Kagan in Of Paradise and Power: America and Europe in the New World Order. “American power made it possible for Europeans to believe that power was no longer important.”

Yet the banality of this conceit has been exposed as never before—in Ukraine, Syria, Iraq, in Paris, and in the ongoing struggle against the fascist barbarism of the Islamic State. A European Union that fails to confront these new realities will be of little help to the United States—or to the liberal democratic order that it claims to represent.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

Joseph Loconte's Blog

- Joseph Loconte's profile

- 70 followers