Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 15

June 22, 2016

Huffington Post: Jo Cox And The Conscience Of The West

This article was originally posted at The Huffington Post.

The brutal murder of British parliamentarian Jo Cox, praised as a relentless and warm-hearted humanitarian, has sent a nation into mourning. A wife and mother of two small children, no British lawmaker fought harder for a more humane immigration policy toward refugees fleeing the Syrian civil war, especially the thousands of Syrian children who have lost their families in the conflict. Cox’s death invites some intense soul-searching — not only in Britain but also in the United States — about the West’s failure to prevent the worst humanitarian disaster since the Second World War.

Soon after joining Parliament in May 2015 as a Labour MP, the 41-year-old Cox help set up the All Party Parliamentary Group on Syria with Conservative MP Andrew Mitchell. The group collects evidence from military commanders, diplomats, and officials from the region about the plight of the roughly 4.5 million refugees who have fled Syria’s five-year civil war to neighboring countries. Earlier this year Cox fought for legislation to admit into the UK at least 3,000 child refugees from Syria — roughly three percent of the estimated 95,000 unaccompanied minors, mostly from Syria, now living precariously in Europe. “Those children have been exposed to things no child should ever witness,” she said, “and I know I would risk life and limb to get my two precious babies out of that hellhole.”

Though a junior parliamentarian in the opposition party, Cox quickly earned a reputation as a bold and principled human rights advocate. Her campaign for Syrian refugees was waged in the midst of Britain’s national debate over whether to remain in the European Union, which has been widely criticized for mishandling the immigration crisis. Cox’s assailant was a 52-year-old-man who shouted “Britain First,” a slogan associated with far right elements in Great Britain.

Many American conservatives would not agree with Cox’s views on immigration or her outspoken support for the European Union. But liberals would not have cheered her recent speech in Parliament, where she vigorously rebuked both David Cameron and Barack Obama for failing to act decisively to confront the escalating violence in Syria:

I believe that both President Obama and the Prime Minister made the biggest misjudgment of their time in office when they put Syria on the ‘too difficult’ pile. Instead of engaging fully, they withdrew and put their faith in a policy of containment. This judgment, made by both leaders for different reasons, will, I believe, be judged harshly by history, and it has been nothing short of a foreign policy disaster.

Of course, Cox is right: Britain has followed America’s lead on Syria, right into a moral quagmire of feckless and cynical diplomacy. Obama’s views on Syria were best expressed recently by Ben Rhodes, his principal foreign policy advisor: “Nothing we could have done,” Rhodes told a group of Syrian activists, “would have made things better.”

The problem is not just that the Obama White House has adopted, unflinchingly, this defeatist view of the Syrian tragedy. It is effectively the position of both presumptive party nominees for president, Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump. It is the position of Bernie Sanders, the Democratic Socialist who has drawn millions of voters into his isolationist mirage. It was, for anyone’s guess, the position of most of the 16 Republican presidential candidates who have since dropped out of the race.

The depth of America’s leadership crisis on Syria is indeed staggering. Aside from Rep. Chris Smith (R-New Jersey), Senator Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas), and a pitifully tiny handful of others, there are no members of Congress — Republican or Democrat — who match the humanitarian vision and commitment of Jo Cox. With regards to Syria’s refugee children, she has no counterpart in the U.S. Congress. Fears of Islamic radicals slipping into the refugee population have overtaken our politics, leaving child refugees out of sight and out of mind.

Secretary of State John Kerry, for his part, delivered a flawed Syrian “peace” initiative that simply allowed Bashar al Assad to strengthen his position, thanks to Russia’s unchallenged military intervention. The collapse of the peace plan, which has left tens of thousands of civilians at grave risk — many of them children — was predicted by diplomats involved in the negotiations. Even Samantha Power, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and an advocate of humanitarian intervention, has provided cover for the administration’s moral abdication in Syria.

Now compare Obama’s powder-puff diplomacy to that of Jo Cox, who took a Russian ambassador to task for his country’s bombing campaigns against Syrian civilians. “She was fearless, utterly fearless,” Andrew Mitchell wrote in The Telegraph. “Last year, we went to see the Russian ambassador in London, to give him a rollicking about the terrible way his country has behaved in Syria. He’s a professional diplomat and a pretty tough case. But Jo got the better of him: it was her mixture of charm and steel.”

Cox spent a decade at Oxfam, the British aid agency, and worked at the Freedom Fund, an anti-slavery organization, before joining Parliament. A devoted mother, she often brought her children with her into Westminster. Yesterday more than 1,500 parliamentarians from 40 countries signed a pledge to uphold Cox’s humanitarian legacy — an unprecedented expression of solidarity for a junior politician. “Jo was a lifelong campaigner against injustice,” the joint statement says. “We will do whatever it takes to renew our bonds and fight for those at the margins of our society, our continent, and the world.”

Can anyone imagine a similar outpouring of support for any major American politician?

Earlier this week in the House of Commons, parliamentarians wore white roses as they paid tribute to a colleague who had devoted most of her adult life helping people on the outskirts of civilization, regardless of race or creed. For an hour they spoke, with deep affection and eloquence, often choking back tears, as they put aside partisan differences to grieve together and to reflect on a remarkable life cut short. As one participant put it, “not in living memory has there been a House of Commons session like it.”

It is becoming increasingly difficult to imagine such a scene on the floor of the U.S. House or Senate: our politics has become so shallow and degraded, our leaders so morally compromised. In a nation once admired for its open borders, its commitment to human rights and humanitarian assistance, something has gone wrong — deeply and disturbingly wrong.

Jo Cox, I suspect, would have some ideas about how to set things right.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West.

June 20, 2016

National Review: Brexit and British Exceptionalism

This article was originally posted at National Review.

The desire of many British citizens to leave the European Union is being assailed by American cultural elites as hysteria: a cancerous growth from the blighted soil of nativism, nationalism, and Islamophobia. New York Times columnist Roger Cohen, for example, finds it “unimaginable” that most Britons would vote “yes” in the June 23 referendum, known as Brexit: “I believe that reason will prevail over derangement.”

Only a degraded form of liberalism, however, fails to see why Great Britain might view the European Union with dismay. Whatever its noble intentions, the EU has come to embody a set of values fundamentally at odds with Britain’s historical ideals and institutions. Put simply, British exceptionalism will never make its peace with the secular and leftist assumptions of the European project.

Liberals on both sides of the Atlantic have conveniently forgotten the decisive role played by Great Britain in setting the foundation for the modern democratic state. Like no other country in Europe, Britain developed a tradition of natural rights, the rule of law, trial by jury — all informed by its Christian culture and institutions. Even Montesquieu, the French theorist most associated with the separation of powers, looked to the English example. “He was an ardent admirer of the English constitution,” says Russell Kirk in The Roots of American Order. “He finds the best government of his age in the constitutional monarchy of England, where the subject enjoyed personal and civic freedom.”

Britain’s political and social institutions, nourished by these ideas, stretch back centuries. “Where French kings relied on authority and force, the English sought consent and co-operation at every level, from Parliament to parish,” writes John Miller, professor of history at the University of London. “Louis XIV’s success owed much to the fact that the ruling elite and the king’s officials generally accepted the principles of absolutism. There was no such acceptance in England.”

That’s right — long before Madison, Jefferson, and Rousseau, English revolutionaries were rejecting political absolutism. They proclaimed man’s natural and inalienable rights and reimagined the purposes of government in light of these rights.

At the heart of their argument was the doctrine of consent: the God-given freedom of the individual to choose his political and religious commitments. As John Locke put it in his Second Treatise of Government (1690), political authority remains legitimate only if it retains the consent of the governed. “Men being, as has been said, by nature all free, equal, and independent, no one can be put out of this estate and subjected to the political power of another without his own consent.”

Now compare this with what Hobbes might call “the mighty leviathan” of the European Union. The Council of Ministers, the EU’s most powerful decision-making body, is made up of non-elected civil servants who can impose policies on member states without approval by those states. Although Britain remains outside of the euro, it is subject to laws generated by the unelected EU Commission: regulations, at least a thousand a year, which dictate everything from the size of olive-oil containers to immigration policy. Meanwhile, an unaccountable European Court of Justice decides whether British domestic law is in sync with EU law.

Perhaps the best summary of the EU’s trampling over British sovereignty comes from Justice Secretary Michael Gove. “As a minister I’ve seen hundreds of new EU rules cross my desk, none of which were requested by the UK Parliament, none of which I or any other British politician could alter in any way and none of which made us freer, richer, or fairer,” Gove explained in announcing his support for Brexit. “It is hard to overstate the degree to which the EU is a constraint on minsters’ ability to do the things they were elected to do, or to use their judgment about the right course of action for the people of this country.”

It’s true that Europe’s immigration and debt crises have added momentum to the campaign for EU withdrawal. But Great Britain’s discomfort with the European project has deeper historical roots. “For the English-speaking peoples, this is an opportunity to reflect on the benediction of our birth,” writes Daniel Johnson, editor of the London-based Standpoint. “No other family of nations has made so many converts for Western civilization, thanks to the ubiquity of the language and the uniqueness of the values which our intellectuals scorn at their peril.”

Ironically, some Brexit opponents invoke Winston Churchill — whose commitment to defending Britain’s political achievements was second to none — as one of the founders of the European Union. In a speech at Zurich University on September 19, 1946, with the dreadful prospect of European disunity amid the rising menace of Soviet Communism, Churchill called for a “United States of Europe.” The objective, he said, was to provide a structure under which the nations of Europe “can dwell in peace, in safety and in freedom.”

It is one of the achievements of the European Union — aided mightily by the United States and NATO — that the prospect of another European war is inconceivable. Peace on that troubled continent has been secured.

Nevertheless, thanks in part to the creeping despotism of EU institutions, Churchill’s other objectives for European unity — safety and freedom — are under assault. And no nation in Europe is more appalled by this assault than Britain, the longtime defender of security and freedom in Europe. From Henry V at Agincourt (1415), to Wellington at Waterloo (1815), to the British Expeditionary Force at the Somme (1916), to the Commonwealth troops at Normandy (1944) — England’s cultural identity is bound up with “preserving the liberties of Europe.”

This is British exceptionalism, something liberal intellectuals cannot abide. It is also a feature of the national character, which most Britons cannot disown. Locke captured well the English disposition during the nation’s hour of revolution: “For when the people are made miserable, and find themselves exposed to the ill usage of arbitrary power . . . [they] will be ready upon any occasion to ease themselves of a burden that sits heavy upon them.”

As the British people seek to lift the burden of arbitrary power from their island nation, they should know they have allies across the Pond — grateful inheritors of the same spirit of liberty.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West.

June 13, 2016

Providence: The Orlando Massacre and the War on Truth

This article was originally posted at Providence.

After beginning his murderous assault on a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida yesterday morning, Omar Mateen called 911 and pledged allegiance to the Islamic State. Within hours, ISIS claimed responsibility for the massacre that left 50 people dead and 53 wounded. The body count, expected to rise, makes the Orlando shooting the most lethal terrorist attack on U.S. soil since 9/11 and the worst mass shooting in American history.

Yet hours later, in his remarks to the nation, President Obama called the shooter’s rampage “an act of terror” and “an act of hate”— but not an act inspired by the ideology of radical Islam. Instead, the president politicized the event, calling it a consequence of lax gun control laws. “This massacre is therefore a further reminder of how easy it is for someone to get their hands on a weapon that lets them shoot people in a school, or in a house of worship, or a movie theater, or in a nightclub.” Even now, after the success of ISIS in recruiting and radicalizing thousands of individuals into the theology of violent jihad, the White House does not deviate from its posture of denial.

The president’s many allies, in politics and the media, embody the moral and spiritual poverty of modern liberalism. For over 15 years the West has faced a global network of terrorists, bound by a common ideology, committed to re-establishing an Islamic caliphate and enslaving or destroying anything that stands in its way. And yet the cultural left treats the Orlando assault as if none of this has been going on—as if religious belief played no role in the modern world, as if there was no difference between a school shooting by a young man who emotionally snaps and a suicide bombing planned and inspired by ISIS.

Consider just one example of the liberal frame of mind, from MSNBC yesterday:

CHUCK TODD: We don’t know—hate crime, terrorism…Should it matter? It’s a terrorizing situation no matter what.

TOM BROKAW: It shouldn’t matter…We don’t have any dialogue going on in America about all these mass shootings that have occurred since San Bernardino. And they’ve been going on around the country, three or more killed at a time…

CHUCK TODD: By the way, dead people are dead people. I hate to say, it all looks bad…

JOY-ANN REID: Whether it’s a hate crime or whether it’s related to international terrorism, we’re not getting to the core issue which is how easy it is to get a gun.

Here is the progressive response to the gravest threat to Western civilization since the Cold War: Dead people are dead people. The problem is not only what liberals think about the scourge of Islamic extremism. It is how they think—if, in fact, the rational act of thinking is even involved in their debased deliberations.

The problem, of course, is that the intellectual deceit of the Obama administration—the refusal to admit that a religious ideology linked to Islam lies at the center of the terrorist cancer—puts the United States at great risk. The bi-partisan 9/11 Commission Report, widely praised for its assessment of the threat posed by al Qaeda and its affiliates, explains why:

But the enemy is not just ‘terrorism,’ some generic evil. This vagueness blurs the strategy. The catastrophic threat at this moment in history is more specific. It is the threat posed by Islamist terrorism…With it there is no common ground—not even respect for life—on which to begin a dialogue. It can only be destroyed or utterly isolated.

Isolating and destroying radical Islamism involves not only an aggressive military response. It requires an intelligence community that understands the religious commitments of its enemy. Instead, for eight years, the president has weakened the intelligence-gathering tools essential to preventing attacks against American citizens. Thanks to the Obama administration, our national security officials are not trained in the teachings of radical Islam. Thanks to a politically correct White House, they are failing to learn from the attacks in Tel Aviv, Paris, Brussels, Boston, and San Bernardino. ISIS and its affiliates are focusing on “soft targets” to terrorize the West—and are increasingly adept at recruiting Muslims here and abroad as foot soldiers in their unholy war.

Nevertheless, with a straight face, President Obama told the American people yesterday: “We’ve reached no definitive judgment on the precise motivations of the killer.” He said this even after being briefed that twenty-nine-year-old Omar Mateen was investigated twice by the FBI for links to terrorism, most recently in 2014, for ties to Moner Mohammad Ausalha, an American who went to Syria as a suicide bomber. According to an agent at the FBI’s Tampa division, the bureau concluded that “the contact between the two men had been minimal” and “did not constitute a substantive threat.” Case closed.

Exactly how much contact with individuals swearing allegiance to the Islamic State is required before our security apparatus intervenes? We’ve reached no definitive judgment on the precise motivations of the killer. Of course they haven’t, since this White House is too morally degraded to make such a judgment. Fifty Americans are dead, fifty-three wounded: more collateral damage in Barack Obama’s war on the truth.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West.

June 10, 2016

Providence: Faith and a Free Press, Under Assault

This article was originally posted at Providence.

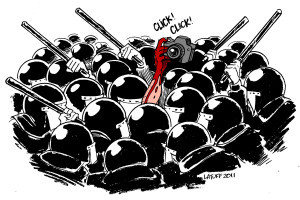

The deadly attack by the Islamic State on the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris last January was an omen of things to come: a growing campaign against freedom of the press, much of it driven by religious extremism. The result, according to recent reports, is that media freedom around the world has dropped to its lowest point in 12 years. The question now is whether those who care about press freedom understand its debt to a deeper freedom—liberty of conscience.

“Political, criminal, and terrorist forces sought to co-opt or silence the media in their broader struggle for power,” according to a 2016 annual report released by Freedom House. The problem is “most acute in the Middle East,” where governments and militias pressure journalists and media outlets to deliver their message or face demonization, death threats, or worse.

The Freedom House study confirms a report released in April by the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders, which noted a “deep and disturbing decline” in media freedom. “The climate of fear results in a growing aversion to debate and pluralism,” said Christophe Deloire, secretary-general of Reporters Without Borders. “Journalism worthy of the name must be defended against the increase in propaganda and media content that is made to order or sponsored by vested interests.”

Syria, a cauldron of religious extremism and violence, was the deadliest place for reporters in 2015, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. At least 14 journalists were killed, while three Syrian reporters who sought safe haven outside the country were assassinated. Press freedom has eroded significantly in Turkey, where President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has seized control of private media groups and cracked down on critics of his Islamist agenda. In China, where freedom of religion is severely restricted, “the Communist Party took repression to new heights,” according to Reporters Without Borders. And on it goes.

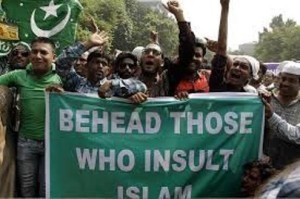

Lost among many journalists, civil libertarians, and human rights organizations, however, is the most salient fact—that freedom of the press is always under assault in nations that fail to respect freedom of religion. When, in January 2015, the government of Saudi Arabia punished Raif Badawi, a blogger, for allegedly insulting Islam—he was sentenced to 1,000 lashes—it was acting on the logic of religious authoritarianism. Media moguls such as The New York Times devote enormous attention to journalists harassed or threatened by thuggish regimes, but mostly ignore religious dissenters who endure far worse treatment—including beheading and crucifixion.

Western elites have forgotten how laws protecting free speech came about in the first place: they were a product of the vigorous debates over freedom of conscience during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—an argument rooted in the Bible.

The earliest champions of a free press were not Enlightenment philosophes. They were dissenting Christians, most of them Protestants, battling the political and religious authoritarians of the day. They defied the censorship regimes, risking prison and death to publish their works. They understood that religious belief—what Roger Williams called “soul freedom” and what John Locke called “the inner persuasion of the mind”—was the foundation for a host of other rights and freedoms, including a free press. “It is a woeful privilege attending all great states and personages,” wrote Williams, “that they seldom hear any other music but what is known will please them.”

Militant secularists, here and in Europe, are as guilty of neglecting these facts as militant Islamists. In both cases, the results are the same: the stifling of free speech and the breakdown of civic peace. In A Free People’s Suicide: Sustainable Freedom and the American Future, social thinker Os Guinness warns that it is “inadequate and foolish” for liberals to focus on the negative notions of hate speech and hate crimes to the near exclusion of religious freedom:

Without acknowledging the cornerstone place of religious liberty, Europe will not be able to accommodate both liberty and cultural diversity; Muslims will not be able to maintain the integrity of their own faith under the conditions of modernity, let alone learn to live peacefully with others; and America will never create the truly civil and cosmopolitan public square that the world requires today.

Herein lies the intellectual conceit that ultimately cripples the case for free speech and a free press: the pretense that freedom of conscience is expendable in modern, democratic societies. A grudging toleration of religious belief is no substitute for robust religious freedom and pluralism—and cannot itself be sustained for long. Until journalists and other cultural leaders learn to care about religious freedom as much as they care about press freedom, their task remains imperiled.

In the end, the secularist and the Islamist will join hands in the assault on liberty.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West.

June 3, 2016

Providence: Clinton on Trump’s Foreign Policy—Right Message, Wrong Messenger

This article was originally posted at Providence.

“Donald Trump’s ideas aren’t just different,” Hillary Clinton told an audience in San Diego yesterday. “They are dangerously incoherent.” There are several truths, bitter and profound, about Clinton’s speech in which she excoriated Trump for his foreign policy views. Taken together, they point to an almost unprecedented crisis in American political leadership that cuts across party lines.

The first truth is that Clinton, the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, is essentially correct about the presumptive Republican nominee. Trump’s foreign policy statements are indeed “dangerously incoherent” and, if implemented, would create a much more unstable and violent world.

Tired of seeing the United States bear the burden of providing security for our allies, Trump would allow a nuclear arms race in Asia—as if America’s careful stewardship of its nuclear dominance has done nothing to promote international security in the region. Resentful that our NATO allies fail to invest adequately in their own defense, he would encourage the dismantling of NATO—despite it being the most successful political-military alliance in history. He would order the military to torture and murder civilians related to terrorists—a war crime under international law. He would approve a ban on all Muslims trying to enter the United States—a repudiation of centuries of American immigration policy that plays into the hands of radical Islamic extremists.

Clinton also accused Trump of being “temperamentally unfit” for the office of president. “Now imagine Donald Trump sitting in the Situation Room, making life-or-death decision on behalf of the United States,” Clinton said. “Imagine him deciding whether to send your spouses or children into battle. Imagine if he had not just his Twitter account at his disposal when he’s angry, but America’s entire arsenal.”

Can even Trump’s most rabid supporters ponder this scenario without a twinge of anxiety? The power of the American presidency is like none other on earth. It is a certainty that Trump’s worst vices—his crudeness, his infantile attacks on critics, personal grudges, unchecked egotism—would be magnified the day he took office. Yes, try to imagine Trump with his finger on the nuclear button without trembling.

The second truth is that Trump’s ascendancy as the Republican standard-bearer promises to permanently deprive the party of one of its historic advantages over Democrats: its status as the political party most trusted by the American people to navigate the United States in foreign affairs, especially in the face of international crises.

“If America doesn’t lead, we leave a vacuum,” Clinton said. “And that will either cause chaos, or other countries will rush to fill the void.” Trump’s “America First” sloganeering is simply a revival of the morally obtuse isolationism of the 1930s. Under a Trump presidency, America’s indispensable role in promoting democracy and upholding international peace and security—American exceptionalism—would be trampled underfoot. Ronald Reagan’s “shining city on a hill” would slip into a fearful sinkhole of fortress America.

The irony of Clinton’s message, of course, is that she is the messenger. Her critique of Trump’s deficiencies is substantive, detailed, even devastating. Any of Trump’s rivals for the Republican presidential nomination could have delivered it, if only they had the courage of their convictions. But Hillary Clinton, despite her many years in political life, ranks as among the least capable—and least trustworthy—to guide the United States in an unstable and dangerous world.

“Unlike him,” she said of Trump, “I have some experience with the tough calls and the hard work of statecraft.” Yes, as a former Secretary of State, Clinton has experience in foreign affairs. But her experience culminated in a catalogue of duplicity, misjudgments, and failure.

Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, the humanitarian crisis in Syria, the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq, the lethal assault on the U.S. embassy in Benghazi (and the White House’s fraudulent attempt to cover up its blunders), the disintegration of the Libyan state into a terrorist stronghold—Clinton played a role in all of these debacles. Her dissembling about her illicit email account—regardless of the risks to national security—fits the Clinton pattern of ignoring laws and norms that conflict with her political aims.

If America doesn’t lead, we leave a vacuum. Here is a geo-political truth, uttered by Clinton’s own lips, that offers the ultimate indictment of her leadership. The projection of American weakness under the Obama-Clinton White House has indeed created a vacuum—filled by the forces of barbarism and lawless aggression. In the end, Clinton’s foreign policy speech, sober enough about Trump, devolved into prevarications, half-truths, and craven deception about her own diplomatic record.

Thus Americans are faced with two likely candidates for president, a Republican and a Democrat, who are both desperately unqualified for the office. America’s character crisis, long festering, has reached a new depth. We can thank a popular and political culture that worships celebrity and winks at cynicism—a culture of our own making. And we have forgotten, to our great peril, the democratic creed of our nation’s first commander in chief: “Let us raise a standard to which the wise and honest can repair; the rest is in the hands of God.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

May 24, 2016

Providence: The Vietnam Syndrome, Revisited

This article was originally posted at Providence.

President Obama’s announcement yesterday lifting the decades-old ban on weapons sales to Vietnam—despite the nation’s appalling human-rights record—fits a desultory pattern of the White House reinforcing bad behavior. Worse still, the rueful lessons of the Vietnam War, especially their roots in the hubris of modern liberalism, remain largely forgotten.

Arriving in Hanoi on Sunday, Obama is hoping to use his three-day visit in Vietnam to strengthen commercial and security ties, including approval for a 12-nation trans-Pacific trade agreement that has gone nowhere in Congress. Obama reportedly believes that “we can move beyond difficult and complicated histories” to find areas of common interest. But there seems to be little understanding in the White House of the historical and ideological reasons for this “complicated” history. There was not even the pretense in the president’s remarks that Vietnam, a communist state which tolerates no political opposition, is expected to initiate political or economic reforms.

Obama was predictably mute about the weekend “elections” in Vietnam, no doubt because they serve as an embarrassment: Only candidates approved by the Communist Party could participate. No matter. The government released a fabricated figure for voter turnout of 98.77 percent. Human rights organizations of all stripes agree about Vietnam: Freedom of speech, press, association, and religion are severely restricted. Private property rights are constantly under assault. Critics of the government face harassment, torture, and imprisonment. Even the left-leaning Human Rights Watch condemned the arms agreement. As the organization summarizes it: “Vietnam’s human rights record remains dire in all areas.”

Nevertheless, deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes claims that the lifting of the arms embargo “removes a lingering vestige of the cold war.” Yes, that pesky and distracting vestige known as the promotion of democratic ideals—the only proven safeguard of individual rights against the will to power—no longer applies. Ever the Machiavellian, Rhodes boasts of the progress being made in improved relations between the two countries, thanks to Team Obama. “You could not have a more contested, controversial, costly, tragic war than the Vietnam War,” Rhodes opined, “and now [Vietnam] is becoming a partner of the United States, an important partner.”

A thuggish and authoritarian regime, viciously determined to impose its communist creed on an unwilling majority, unrepentant about the storm of human destruction and misery unleashed in its cause—this nation is becoming a “partner” of the United States? While insisting that arms will not be sold capriciously to Vietnam, Obama sees no reason to let political ideology stand in the way. “We’re going to continue to engage in the case-by-case evaluation of these sales,” the president said. “But what we do not have is a ban that is based on an ideological division between our two sides.”

Perhaps the ideology animating the autocrats in Hanoi is not so different, after all, from that of modern liberalism and the political party that genuflects at its altar. Both share a utopian frame of mind about the capacity of the state to organize and calibrate virtually every aspect of society.

Critics of the Vietnam War focus on the Cold War doctrine of containment as the principal cause for the debacle of American involvement. A flawed military strategy, unreliable partners in South Vietnam, a profoundly determined and resilient foe—all of these factors help explain the U.S. failure in Vietnam. But perhaps the really decisive element was the attempt by a liberal Democratic president to apply his concept of the welfare state to southeast Asia.

As historian Walter McDougal explains in his masterful book, Promised Land, Crusader State, Lyndon Johnson thought he could impose on South Vietnam the values and the architecture of his “Great Society,” and that he could accomplish this in the midst of a ruthless military insurgency. “Yes,” McDougal writes. “Vietnam was the first war in which the United States dispatched its military forces overseas not for the purpose of winning but just to buy time for the war to be won by civilian social programs.”

An exaggeration? Hardly. By 1966, about 43 percent of USAID funding worldwide was flowing to South Vietnam. Billions of dollars in economic development schemes simply fueled a black market in stolen consumer goods and created an “economy” that pandered to the appetites of American soldiers and civilian aid workers—including drugs, alcohol, and prostitutes. As McDougal puts it: “South Vietnam’s cities—like much of inner-city America—soon became corrupt and dependent welfare zones.”

Johnson imagined that he could achieve military victory while instituting a political and economic transformation—in a post-colonial nation, a brand-new nation with no institutions to build upon, a nation that had never experienced self-government or the benefits of a market economy. Henry Kissinger—who has his own critics in his handling of Vietnam under President Nixon—viewed this as an innovation in American foreign policy. It was, he wrote, “a new concept not previously found in the diplomatic vocabulary.” It was, in a word, “nation-building.” Its abject failure in 1975, when American diplomats were forced to flee Saigon in disgrace, created the “Vietnam syndrome,” a fear and loathing of U.S. military engagement.

Whether nation-building was a new concept introduced in the Vietnam War is debatable. Just consider the American occupations and successful democracy-promotion efforts in Japan and Germany after the Second World War.

It must be said that naïve attitudes about nation-building are not confined to progressives and liberal Democrats. George W. Bush will be judged—and probably forever vilified—as the American president who unleashed his own vision of democracy promotion in Afghanistan and Iraq. Not even Bush’s defenders could claim irrefutable success in either of those countries, campaigns that have left the Republican Party, and the American people, deeply divided about U.S. engagement in the region.

Nevertheless, there was an astonishing hubris involved in the quagmire of Vietnam. Johnson, along with John Kennedy’s “best and brightest,” presumed they could impose their own ideas about economic and political reform on a population they knew little about. And they did so with astonishingly little regard for the human costs involved. Political liberalism, with its facile trust in the ideals and motives of its secular humanitarianism, is uniquely prone to this temptation.

That, too, is a lesson of Vietnam, a lesson apparently lost on the occupants of the White House. They do not see—they do not wish to see—that America’s “difficult” and “complicated” history with Vietnam was forged by their own ideological history, a story darkened by its own mistakes, tragedies, and quagmires.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

May 16, 2016

Providence: Obama’s Foreign Policy Deceptions

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Last week’s startling confession by White House operative Ben Rhodes—that the Obama administration lied to the American people about its dealings with Iran to secure a nuclear agreement—not only confirms the perception of a mendacious and arrogant presidency. It exposes a feverish and even delusional frame of mind: an uncompromising revulsion for war that has undermined American security and invited a cascade of extremism, violence, and human suffering.

In an interview with David Samuels published in the New York Times Magazine, Rhodes, deputy national security adviser for strategic communications, candidly explained how the White House spun the Iran negotiations. The official story, shaped by Rhodes, was that the Iran deal began in 2013, after the election of the “moderate” Hassan Rouhani supposedly marginalized “hardliners” opposed to negotiations. Under this happy scenario, the “moderates” sought a policy of “openness,” including a willingness to dismantle Iran’s illicit nuclear-weapons program. The only alternative to the agreement, according to this version, was war with Iran.

All of this was a fiction. Talks with Iran, in fact, had begun in 2012—with “hardliners” unlikely to negotiate in good faith. Obama’s closest advisors acknowledge he wanted talks with the Iranians from the start of his presidency. Most Iran experts see little difference between the militant mullahs and Rouhani, whose candidacy was handpicked by Iran’s supreme leader, the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. (Yes, that’s the “death to America” Khamenei.) Moreover, many believe that continuing the economic sanctions against Iran—instead of abandoning them at the outset—would have yielded a much stronger disarmament agreement with Tehran.

It is especially damning that Samuels, himself a liberal journalist and an Obama supporter, leaves no doubt about the administration’s strategy of deception: “The way in which most Americans have heard the story of the Iran deal presented…was largely manufactured for the purpose of selling the deal.”

Rhodes brags to Samuels about his role in misleading clueless journalists whose “only reporting experience consists of being around political campaigns.” Today’s large cohort of young reporters, he implies, are especially vulnerable to manipulation because “they literally know nothing.” With a kind of Trumpian self-regard, Rhodes details the Obama playbook:

We created an echo chamber. They were saying things that validated what we had given them to say…In the absence of rational discourse, we are going to discourse the [expletive] out of this. We had test drives to know who was going to be able to carry our message effectively, and how to use outside groups like Ploughshares, the Iran Project and whomever else. So we knew the tactics that worked.

Rhodes’ associate in the propaganda war is Tanya Somanader, a director at the White House Office of Digital Strategy, who even named some of the journalists in their echo chamber: Laura Rozen of Al-Monitor and Jeffrey Goldberg at The Atlantic. (My critique of Goldberg’s 19,000-word recent defense of the Obama doctrine can be found here.) The Soviet Union used to refer to Western journalists duped into applauding communism as “useful idiots.” What should we call journalists who cheerfully enlist in the Obama administration’s dangerous campaign of disinformation?

Behind all the messaging and manipulation lurks an emotion: an animus against U.S. military action, born out of a hatred for the war in Iraq. Rhodes shares this emotion with President Obama—“I don’t know anymore where I begin and Obama ends,” he confessed—and together they have brought about a radical reorientation of U.S. foreign policy. Indeed, according to the New York Times profile, Ben Rhodes is “the single most influential voice shaping American foreign policy aside from Potus himself.”

No matter what the issue—whether it is the Iranian nuclear threat, the Syrian civil war, the rise of the Islamic State—Rhodes retreats to his emotional lodestar, the Iraq war. As Samuels bluntly summarizes it: “Iraq is his one-word-answer to any and all criticism.” It is reminiscent of the post-Vietnam War syndrome that paralyzed the administrations of Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton.

Like other liberals disillusioned by America’s foreign policy misdeeds, Rhodes exudes the moral smugness of an Egyptian pharaoh. Dissenters are viewed as enemies, reactionaries, war-mongering troglodytes. Samuels writes revealingly of “the brutal contempt that is a hallmark of his private utterances” and the “aggressive contempt for anyone or anything that stands in the president’s way.”

Given the many mistakes and the painful sacrifices made during the Iraq war, the desire to keep America out of another conflict in the Middle East should not be met with similar contempt. But a revulsion for war cannot be the sum total of U.S. foreign policy.

What neither Rhodes nor Obama are willing to admit—after nearly eight years in the White House—is that the projection of American weakness and retreat invites instability and tragedy. Their facile assumptions about securing peace are akin to those of the peace-loving statesmen of the 1930s, whose horror at the prospect of war allowed international fascism to overwhelm Europe. “They have created an attitude of irresponsibility toward the tragic history of Europe,” wrote Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, “and a spirit of cynicism in estimating the consequences of the war.”

The United States has effectively stayed out of the Syrian conflict, for example, and to hear Rhodes tell it, we should congratulate the White House for its prudence and geo-political humility. No American soldiers, after all, have died in this war. But Rhodes has less to say about the 470,000 Syrians who have perished violently because of Bashar al-Assad’s determination to remain in power, or the fact that half of the population of Syria has become refugees. “Nothing we could have done,” he reportedly told a group of Syrian activists, “would have made things better.”

Nothing—absolutely nothing—could have made a difference in Syria? This is the lesson of Iraq? What about another lesson from Iraq, when Saddam Hussein threatened to exterminate the Kurds after the first Gulf War? The United States, along with Great Britain, created a no-fly zone to protect the Kurdish people from mass slaughter. We shot down Iraqi planes, risked war, and helped the Kurds to build a decent, independent, self-governing state. Today the Iraqi Kurds are intensely pro-American, pro-Western, and among our best allies in the fight against radical Islam.

Nothing we could have done would have made things better. This fatalism—a kind of internal mantra at the White House—reveals the character of Obama’s foreign policy team: their moral shallowness and blithe disregard for America’s strategic role on the world stage.

And their inexperience. Next to the president himself, no single person ever acquired the kind of political power that Rhodes has acquired with so little understanding of foreign affairs. On September 11, 2001, Rhodes was in an MFA program at New York University, planning to become a famous fiction writer. He was a mediocre student, having spent most of his high school years “drinking, and smoking pot and hanging out in Central Park.” Rhodes had no interest in diplomacy or American history. His only published work was a short story, “The Goldfish Smiles, You Smile Back.” It was good enough to gain him entry into the Washington political establishment as a speechwriter.

As for becoming a famous fiction writer, it seems that Ben Rhodes has achieved this goal beyond his wildest dreams. Yet there is a price for his success—a human cost being measured not only by what America does, but by what it fails to do. Smile on, Goldfish, smile on.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

May 2, 2016

Providence: Winston Churchill and the Crisis of American Leadership

This article was originally posted at Providence.

President Obama’s explanation for removing a bust of Winston Churchill from the Oval Office—he wanted to make room for a bust of Martin Luther King, Jr.—probably won’t satisfy his conservative critics. For years they’ve interpreted Churchill’s disappearance as a snub rooted in the president’s anti-colonial sentiments. “I love Winston Churchill,” Obama insisted during his recent UK trip. “I love the guy.”

The fact is that nearly every American president since Franklin Roosevelt, Democrat and Republican, has cited Churchill as their ideological ally—no matter how implausible the comparison. Like no other world leader, Churchill’s legacy as the great defender of Western Civilization at its darkest hour is enlisted to validate American foreign policy.

In his 1982 speech in Westminster, when Ronald Reagan consigned Soviet communism to the “ash heap of history,” he warned Great Britain against the error of “allowing the dictators to underestimate us.” With Cold War tensions at a new high (thanks in part to Reagan’s unsparing criticism of Moscow), Western unity was essential in the common struggle against communism. As President Reagan saw it, he was echoing Churchill’s challenge to the United States, just days after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor made them allies in the war against Nazism.

“What kind of people do they think we are?” he asked, quoting the prime minister’s 1941 speech to the U.S. Congress. “Free people, worthy of freedom and determined not only to remain so but to help others gain their freedom as well.” Reagan’s determination to go beyond containment—to actually defeat the Soviet Union—was indeed reminiscent of Churchill’s resolve to defeat Nazism. Like Churchill during his years in the political wilderness, however, the American president encountered a European audience deeply skeptical of his hawkish agenda.

Now consider Bill Clinton, the first American president born after the Second World War. On the eve of his decision to bomb Serbia for its ethnic cleansing in Kosovo, Clinton found in Churchill the martial voice he needed. Worried that public opinion would not support U.S. involvement in the conflict, President Clinton raised the specter of appeasement in the 1930s.

“What if someone had listened to Winston Churchill and stood up to Adolf Hitler earlier? Just imagine if leaders back then had acted wisely and early enough, how many lives could have been saved, how many Americans would not have had to die?” Serbia as Nazi Germany? The message seemed especially dubious coming from Clinton, who had pulled American troops out of Somalia in disgrace and refused to intervene to stop the genocide in Rwanda.

How about George W. Bush? Explaining why he had the Churchill bust brought into the Oval Office, Bush emphasized Churchill’s tenacity in the teeth of opposition—a British version of his Texas swagger. “He stood on principle. He was a man of great courage,” Bush explained. “He knew what he believed, and he really kind of went after it in a way that seemed like a Texan to me.”

Bush supporters see this quality in the president’s 2007 decision to authorize the “surge” of U.S. troops into Iraq to stabilize the country in the midst of a sectarian civil war. It was a deeply unpopular—and risky—decision. Military experts credit the surge with preventing Iraq from disintegrating into utter chaos. Yet others point to the initial decision to invade Iraq—without a workable exit strategy—as an example of not heeding Churchill’s counsel about war: “Never, never, never believe any war will be smooth and easy…The Statesman who yields to war must realize that once the signal is given, he is no longer the master of policy but the slave of unforeseeable and uncontrollable events.”

And what of Barack Obama? In a 2011 address at Whitehall, Obama looked to Churchill as he urged the United States and Great Britain to continue to work together to confront global crises. Concluding his speech with a Churchill quote from the end of the Second World War, he said the world would “look back to what we’ve done, and they will say ‘do not despair, do not yield…march straightforward.’”

But what foreign policy choices by President Obama recall the political courage of Britain’s greatest prime minister? The nuclear agreement with Iran, the inability to defeat the Islamic State, the failure to halt Russian aggression in Ukraine, the decision to break his “red line” pledge to punish Syria’s Bashar al-Assad for using chemical weapons against his own people—all of this looks more like Neville Chamberlain than Winston Churchill. Throughout his presidency, in fact, Obama has appeared profoundly uncomfortable with the qualities most often associated with Churchill: martial resolve, moral clarity, and supreme confidence in the transcendent ideals of Western Civilization.

Nevertheless, everyone wants the prime minister on his side. Conservative talk show host Michael Savage has even praised Donald Trump—arguably the least qualified individual to run for president in the modern era—as “the Winston Churchill for our time.” Trump as Churchill? A petulant, self-absorbed casino capitalist is compared favorably to one of the greatest democratic leaders of the twentieth century. It is a claim even less convincing than Obama’s “I love the guy.”

Here is the mournful cry of a political society in crisis: We can still recognize greatness; we cannot fully disown the achievements of leadership that have helped to preserve liberal democracy in the West. But we have forgotten how to produce great men. One is tempted to quote Churchill on this score: “The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

April 8, 2016

Providence: Moral Courage, Obama-Style

This article was originally posted at Providence.

One of Barack Obama’s proudest moments as president, by his own description, was his 2013 decision to repudiate his “red line” warning to Syria’s Bashar al Assad: the threat of U.S. military force to punish the regime for using chemical weapons against its own people. Instead, Mr. Assad, after killing thousands, agreed to surrender his chemical stockpile to international inspectors. “I’m very proud of this moment,” Mr. Obama recently told The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg. “The perception was that my credibility was at stake, that America’s credibility was at stake.”

Why is the president certain that this perception was wrong, and that his failure to enforce a U.S. threat of military action is a reason to boast?

Because, according to Mr. Obama, his decision went against the “playbook in Washington” that presidents typically adopt. “It’s a playbook that comes out of the foreign-policy establishment,” he told Mr. Goldberg. “And the playbook prescribes responses to different events, and these responses tend to be militarized responses.” As the Obama White House sees it, much of the D.C. foreign policy “establishment” is “doing the bidding of their Arab and pro-Israel funders.”

Translation: foreign policy experts who disagree with the president do not have the best interests of the United States in mind. This week some members of the so-called foreign policy establishment fired back.

At a gathering hosted by the Hudson Institute, senior fellow Michael Doran moderated a panel discussion with Republican Senator Lindsey Graham, a member of the Armed Services Committee; Robert Satloff, executive director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Michele Dunne, director of the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; and Ambassador Eric Edelman, of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. All of the panelists criticized the president’s reversal on the use of force against Assad as a dangerous misjudgment that has invited greater instability and international aggression.

Senator Graham said the “big winners” are “those dictators of the world who think they can do anything they want without reprisal.” Ms. Dunne called the president’s approach to Syria “a policy defined by the absence of a strategy.” Mr. Satloff sees a perverse ethical reasoning at work in the White House: “It is not moral courage to take on those who used chemical weapons against the innocent,” he said, “but it’s moral courage to take on the Washington establishment.”

Ambassador Edelman discerns a breathtaking hubris: the president’s belief that his words alone, joined to his personal biography, can change the nature of international politics. “He sees foreign affairs in need of a transformation, which can be accomplished by the force of his personality.”

No need to take the advice of his defense secretaries, three of whom opposed his Syria policy. No reason to heed the collective counsel of his other top military advisors about Afghanistan, Iraq, or the Islamic State. No reason to believe—as every modern president has believed—that breaking a promise to punish international aggression would only invite greater aggression. Such thinking, according to Mr. Obama, is merely the product of an outdated “playbook.”

In all this, says Ambassador Edelman, Barack Obama looks and sounds very much like the Republican presidential front-runner, Donald Trump. “I think what you see on display…is the president’s narcissism.” Whatever we make of that judgment, some of the catastrophic results of the president’s decision-making are on display: Mr. Assad’s continued butchery of Syrian civilians; the rise of the Islamic State and its genocidal violence against Christians and other religious minorities; the profound destabilization of Arab states, such as Jordan and Lebanon, trying to cope with the Syrian refugee crisis; and on it goes.

The long-term consequences of Mr. Obama’s “liberation” from the foreign policy “playbook” could be even more dire. Secretary of State John Kerry, in a rare flash of moral clarity, warned recently about the threat of ISIS—a threat, he neglected to mention, created and sustained by Mr. Obama’s policies in Syria: “You could have allies and friends of ours fail. You could have a massive migration into Europe that destroys Europe, leads to the pure destruction of Europe, ends the European project, and everyone runs for cover and you’ve got the 1930s all over again, with nationalism and fascism and other things breaking out.”

Will this be the ultimate legacy of the Obama doctrine—the collapse of Europe and the rise of new strains of fascist violence around the world?

Mr. Obama’s evident contempt for the foreign policy “establishment” has blinded him to a geo-political reality: The failure to act always carries consequences in the modern world. When the United States fails to act decisively at a moment of international crisis, there can be far more devastating results—more violence, more human suffering—than when America intervenes.

The ongoing effects of the president’s narcissism, if that’s what it is, await the next president.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

April 1, 2016

Providence: Reaping the Whirlwind of Apostasy Laws

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Reports of murderous assaults on Christians in Pakistan—like the Easter massacre last Sunday in Lahore—have focused on the Pakistani government’s double-dealing with the Taliban, or its intelligence failures, or the supposed blowback effects of U.S. drone attacks on terrorist cells in Pakistan. Most of this analysis evades the deepest threat confronting the government: a culture of religious extremism supported by Muslim leaders and underwritten by the Pakistani state.

To make matters worse, whatever influence the United States might have in fostering a more tolerant society in Pakistan is being squandered through ignorance or indifference to the problem.

The latest attack by the Taliban killed 75 people, including 29 children, all of them civilians. It follows an attack in January at Bacha Khan University, which killed 22 and injured 19. Last year the Taliban targeted a school in Peshawar, killing 145, most of them children. Although Muslims were among the slain in the Lahore assault, Christians were clearly the target. “It was our people who attacked the Christians in Lahore, celebrating Easter,” said a Taliban spokesman. “It’s our message to the government that we will carry out such attacks again until sharia [Islamic law] is imposed in the country.”

Why do the Taliban believe they can impose their radical, Islamic ideology upon a nation of 182 million people? Because Pakistan, like other Muslim-majority states, enforces a legal regime that criminalizes apostasy: Anyone accused not only of renouncing Islam but questioning or criticizing the Prophet Muhammed or the Quran faces arrest, imprisonment, torture, and possible execution. Apostasy laws are perfectly consistent with the Taliban’s totalitarian vision—an ideology based on fear and loathing of “the other,” meaning anyone who dissents from established Islamist orthodoxy.

There is only one conceivable result of this policy. “Religious minorities in Pakistan face pervasive societal and institutional discrimination and the threat of violence,” explains Mervyn Thomas, chief executive at the London-based Christian Solidarity Worldwide. “This situation is exacerbated by a culture of impunity and the unchecked influence of extremist groups.” Imams, political leaders, federal ministers—all have incited mob violence against religious minorities.

Pakistan receives about a billion dollars a year in U.S. military assistance, in addition to hundreds of millions of dollars in economic aid. What are the conditions for this support? The Obama administration’s posture is a loathsome mix of silence, confusion, and paralysis.

While condemning “in the strongest terms” the terrorist attack in Lahore, the State Department once again made no reference to Islamic extremism. Once again, State Department spokesman John Kirby failed even to mention the fact that Christians were overwhelmingly the victims of the attack. After being criticized, Mr. Kirby “clarified” his comments the next day: “We have no indications that their [the Taliban’s] claims of responsibility are false,” he said. “Therefore, I have no indications that the motivation that they claim was the reason is also false.”

This is what qualifies in the Obama White House as condemnation “in the strongest terms.” Neither President Obama, nor his secular-minded diplomats, dare to remind the Pakistanis of their obligations to protect the basic human rights of all their citizens—regardless of religious belief. It does not occur to most U.S. diplomats to praise the cultural importance of Christians and other religious minorities to Muslim-majority countries. Yet even the liberal Washington Post, in reporting the Easter massacre, made this observation:

The Christian minority has also contributed greatly to Pakistani society. Many of the best schools and colleges in Pakistan were established by Christians and attended by the country’s Muslim elite, and Christians have been among the most decorated and celebrated members of Pakistan’s military since independence.

Why is it so difficult for President Obama—or anyone else in his administration—to unapologetically proclaim America’s democratic values and to utter these words? There are ideological reasons for this silence, which will have to be unpacked another time. But there is also a widespread blindness to the importance of religious freedom in building stable and just societies.

Take one recent example: In a State Department briefing last November, spokesman John Kirby was asked about pending executions in Saudi Arabia for individuals accused of renouncing or insulting Islam, specifically the Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh. Mr. Kirby read from a prepared text explaining that “the United States strongly opposes laws, including—” He stopped and stammered, obviously uncertain about how to pronounce the next word of his text.

A reporter lent a helpful hand: “apostasy.” Mr. Kirby continued: “Apostasy laws, thank you,” and then stoically read from the remainder of his text about U.S. support for the exercise of “freedom of expression and religion.”

Think about that unscripted revelation of ignorance. We are nearly eight years into the Obama administration—eight years of Islamic extremism, sectarian civil wars, ruthless assaults against religious minorities, beheadings, crucifixions, terrorist attacks in the heart of Europe and on American soil—and a top State Department official does not know the meaning of the word apostasy.

We cannot “win hearts and minds” in the war against the ideology of Islamism if our own minds are not engaged in the battle. We cannot defeat militant religion with a strategy crippled by an uneducated secularism. We need national leaders who are “as wise as serpents and innocent as doves”—not the other way around.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

Joseph Loconte's Blog

- Joseph Loconte's profile

- 70 followers