Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 12

April 14, 2017

National Review: Syria, War Crimes, and the National Interest

This article was originally posted at National Review.

President Donald Trump’s decision last week to order airstrikes to punish Syria for a chemical-weapons attack that killed and injured scores of civilians has exposed conservatism’s intellectual confusion about U.S. foreign policy. Perhaps the most troubling thing about this debate is the deficit of historical perspective – a failure to consider the moral-theological tradition of the West that insists that civilized nations have a responsibility to protect civilian populations in times of war.

Amid the brutally destructive Wars of Religion, Protestant thinker Hugo Grotius wrote On Laws of War and Peace (1625). “Though there may be circumstances, in which absolute justice will not condemn the sacrifice of lives in war,” he argued, “yet humanity will require that the greatest precaution should be used against involving the innocent in danger, except in cases of extreme urgency and utility.”

Here is a political principle, rooted in Judeo-Christian ethics, which has helped to protect countless civilians from the savagery of war. Here is a concept about human dignity that has influenced every international document on the conduct of nations in wartime: from the Geneva Protocol (1925), banning the use of chemical weapons; to the Genocide Convention (1948), adopted in the aftermath of the Holocaust; to the United Nations Responsibility to Protect (2005), a resolution authorizing military force to prevent crimes against humanity.

Yet many of the critics of the U.S. missile strike seem indifferent to this tradition. Conservatives such as Andrew McCarthy argue that Bashar al-Assad’s use of a weapon of mass destruction — which targeted innocent men, women, and children — involved “no vital American interests.” No vital American interests? When did conservatism decide that the United States has no interest in upholding a universal moral norm that has helped to prevent the West from descending into a permanent state of barbarism? When, exactly, did the humanitarian ideals of the Western tradition become irrelevant to the conduct of U.S. foreign policy?

It was the abject failure of the United Nations to uphold these principles throughout the 1980s and 1990s that produced the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine: the proposition that there is a collective responsibility to protect people from genocide, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity — even if it means military intervention. Overwhelmingly approved by the U.N. General Assembly, R2P insists that nations cannot hide behind the U.N. charter and “national sovereignty” in order to wage war against their civilian populations. The signatories to the doctrine — which include the United States — agree to take “collective action . . . should peaceful means be inadequate” to protect populations at risk of gross human-rights abuses. In this, R2P pays homage to the Christian just-war tradition.

The problem, of course, is that the U.N. Security Council is deemed the only legitimate authority to implement the doctrine. Just-war theorist James Turner Johnson has written of the historic dysfunction of the United Nations in this regard: “The structure of the U.N. is such that clear purpose and effective command and control are virtually unimaginable.”

As long as Russia — Syria’s chief patron — retains its veto power on the U.N. Security Council, there will be no U.N. resolution to punish Assad or prevent him from committing more war crimes. Russian president Vladimir Putin has even suggested that the United States manufactured the chemical attack as a pretense for an invasion. We thus face the bizarre spectacle of a permanent member of the Security Council either complicit in a chemical-weapons attack or, at the very least, committed to a false and outlandish narrative of U.S. malevolence — all for the purpose of insulating a genocidal regime from censure. The result, if experience is any guide: an even more belligerent Syria, more mass atrocities, more attacks on humanitarian aid workers, and the near collapse of a universal moral principle.

And there are no vital American interests in play?

“If we are not able to enforce resolutions preventing the use of chemical weapons, what does that say about our effectiveness in this institution?” asked Nikki Haley, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. “When the United Nations consistently fails in its duty to act collectively, there are times in the life of states that we are compelled to take our own action.”

Ambassador Haley has a good deal of U.S. diplomatic history on her side. The 1999 NATO intervention in Kosovo — a bombing campaign that brought an end to the ethnic cleansing of the Balkan wars — lacked U.N. approval. It was, to be sure, a controversial intervention, and Bill Clinton’s deep aversion to American casualties contributed to the carnage and chaos during the campaign. But political realists who saw no important U.S. interests at stake — not even naked aggression and a humanitarian disaster within Europe’s borders could stir them — looked morally bankrupt once peace and security were restored to the region.

The same can be said about the American and British intervention on behalf of Iraqi Kurds after the first Gulf War. The Kurds of northern Iraq rebelled against Saddam Hussein in 1991, after his army was defeated and kicked out of Kuwait by the U.S.-led coalition. But the Iraqi army cracked down on the rebels, and seemed ready to exterminate the entire population — having used chemical weapons against them with impunity during the Iran–Iraq war. Within weeks, a million Kurds fled the region, with nearly 1,000 people dying each day.

The U.N. Security Council approved humanitarian assistance for the Kurds, but it never authorized the no-fly zones established under President George H. W. Bush. From April to September 1991, Operation Provide Comfort flew over 40,000 sorties, relocated 700,000 refugees, and restored many Kurdish villages destroyed by the Iraqi military. Over the next decade, U.S. and British pilots took anti-aircraft fire from Iraqi forces, shot down Iraqi planes, and successfully defended the no-fly zones. Today the Iraqi Kurds are among the most pro-Western allies in the Middle East, and arguably the most effective fighting force against the Islamic State. Their survival and contribution to stability in the region was the result of a humanitarian mission that, according to the realists, involved no vital American interests.

In both instances, the United States drew upon insights embedded in centuries of moral and political philosophy. Conservatives ought to know and care about these ideas, which have done so much to promote international peace and security.

President Trump’s decision to put aside his “America First” campaign pledge and to punish the Assad regime will not solve the nearly intractable problem of the Syrian civil war. The airstrike, confined to a single Syrian airfield, has hardly affected Assad’s capacity to deploy chemical weapons. But Trump’s decision to act, if part of a broader strategy of engagement, has the potential to reverse the diplomatic disaster created by Barack Obama’s feckless and disingenuous policies in Syria. It might help secure a measure of justice where diplomacy, absent the projection of American power, has utterly failed.

The United States has sent a message that lawless regimes cannot always evade the moral laws that govern civilized nations. It is a message that is consistent with America’s vital national interests — and with its most cherished political and religious ideals.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

April 6, 2017

Providence: The Great War & the Dawn of the American Century

This article was originally posted at Providence.

By the spring of 1917, the most advanced nations on earth had spent nearly three agonizing years destroying themselves in a frenzy of blood-letting never seen within the boundaries of Europe.

The United States watched, with bewilderment and anxiety, as a “Great War” among the European states broke out in August 1914. What began as a diplomatic kerfuffle between Serbia and Austria-Hungary quickly metastasized into a global conflict, ultimately involving dozens of nations. What was supposed to be a short, tidy campaign devolved into a ferocious stalemate, a war of attrition, with no end in sight.

America’s decision to enter the First World War on behalf of the Allied forces, in April 1917, shattered the wretched status quo. The nation’s economic and martial resources—the US military would swell to five million men within 18 months—would make a German victory impossible and hasten the end of the conflict.

Vera Brittain, an English nurse working in a London hospital, remembered seeing “a large contingent of soldiers pass by on the main road.” She noted “an unusual quality of bold vigor in their stride,” which “caused me to stare at them with puzzled interest.” Brittain didn’t recognize these fresh troops:

They looked larger than ordinary men; their tall, straight figures were in vivid contrast to the under-sized armies of pale recruits to which we were grown accustomed…Had yet another regiment been conjured out of our depleted Dominions? I wondered, watching them move with such rhythm, such dignity, such serene consciousness of self-respect. But I knew the colonial troops so well, and these were different; they were assured where the Australians were aggressive, self-possessed where the New Zealanders were turbulent.

Brittain then heard an excited cry from a group of nurses behind her: “Look! Look! Here are the Americans!” The arrival of American troops on the European continent also signaled the ascendance of the United States as the leading democratic power in the West. Prodded by a visionary American president, the entire international order would be transformed. The American century was about to begin.

This new American century, however, would begin under the political leadership of Woodrow Wilson, whose approach to international relations was a mix of sloppy moralism, liberal internationalism, and Kantian utopianism. Although understandably appalled by the results of realpolitik, Wilson sought to replace the European “balance of power” with a “community of power,” a union of democracies devoted to peacemaking as a transcendent political ideal. The result was a League of Nations that lacked both the will and the capacity to respond effectively to international aggression.

Beating Swords into Plowshares

There was nothing inevitable about US intervention in the First World War. Indeed, there was absolutely no possibility that the United States would quickly enter the conflict. For over a century, Americans had tried to avoid the political intrigues of Europe. The Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, the Franco-Prussian War, and now this latest outbreak of war—it all seemed to confirm George Washington’s counsel in his farewell address to avoid “entangling alliances” at virtually any cost. Hence the US ambassador to Great Britain, summarizing the American mindset: “Again and ever I thank God for the Atlantic Ocean.”

Woodrow Wilson’s first annual address to Congress, on December 2, 1913—the first time a president personally delivered his State of the Union address—revealed his lawyerly approach to peacemaking:

More and more readily each decade do the nations manifest their willingness to bind themselves by solemn treaty to the processes of peace, the processes of frankness and fair concession. So far the United States has stood at the front of such negotiations. She will, I earnestly hope and confidently believe, give fresh proof of her sincere adherence to the cause of international friendship by ratifying the several treaties of arbitration awaiting renewal by the Senate.

Wilson went on to boast that 31 nations, representing four-fifths of the world’s population, had agreed “in principle” to sign bilateral treaties with the United States to resolve disputes diplomatically. If diplomacy failed, the treaties instructed that all disagreements “shall be publicly analyzed, discussed, and reported upon by a tribunal chosen by the parties before either nation determines its course of action.” In other words, Wilson imagined that a “cooling off” period, legalistically imposed, could overcome nationalistic war fever. “There is no record,” writes Henry Kissinger, “that any such treaty was ever applied to a concrete issue.”

Less than a year later, Europe, and much of the world, would be at war. Wilson immediately declared American neutrality toward all belligerents in the conflict, and instructed US citizens to do likewise in their innermost thoughts.

Political neutrality is one thing; however, economic policy is another. In the first six months of the war, US bankers extended $80 million in credits to Britain, France, and their allies. America was also trading with Germany, but the British blockade of northern Europe made it difficult for the United States to offer loans or credits to the Central Powers. Additionally, there was the sale of armaments: Between August 1914 and March 1917, America sold $2.2 billion in arms to Great Britain and the Allied powers. Almost overnight, the United States became a creditor nation—and would emerge as the strongest economic power on earth by the end of the war.

“He Kept Us Out of War”

If President Wilson wanted a pretext for entering the European conflict, it arrived on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed the British-owned Lusitania. The luxury passenger ship sunk within 18 minutes, taking 1,119 of the 1,924 passengers with it. One hundred and twenty-eight Americans were among the dead—including women and infants. There were lurid newspaper accounts of people struggling to get into lifeboats, of mothers being separated from their babies, of lifeless bodies floating in the water. Americans were stunned and outraged at this “murder on the high seas.” Although support for “military preparedness” increased, there was no public clamoring for war.

Instead, Wilson got assurances from Germany that such atrocities would not happen again. “Peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world,” he said. “There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right.” British officers, who were dying by the dozens every month to combat German aggression, mocked the American president: British artillery shells that failed to explode were called “Wilsons.”

Less than three weeks later, on May 27, Wilson spoke before a crowd of 2,000 supporters at Washington, D.C.’s New Willard Hotel, assuring them that an era of “more wholesome diplomacy” was at hand. America was assuming responsibility in helping to secure the peace of the world, he said, and a new political organization was needed to bring it about.

“So sincerely do I believe in these things that I am sure that I speak the mind and wish of the people of America when I say that the United States is willing to become a partner in any feasible association of nations formed in order to realize these objects and make them safe against violations,” Wilson said. “God grant that the dawn of that day of frank dealing and settled peace, concord, and cooperation may be near at hand!” The room burst into applause, with the liberal press comparing the speech to the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address.

In the 1916 presidential election, Wilson’s campaign slogan—“he kept us out of war”—helped him to narrowly defeat Republican Charles Hughes. The president made several offers—sometimes clumsy and ill-advised—to mediate the conflict. All were rejected by the Allies and Central Powers. Yet Wilson’s effort exceeded anything America had ever attempted in European affairs. For the first time in its history, the United States was trying to negotiate an end to a major European war. “Clearly it reflected the sense that the Europeans were incapable of managing their own, and by extension, the world’s affairs,” writes Harvard historian Akira Iriye, “and that without some leadership role played by the United States, there could be no stable international order.”

Peace Without Victory

The opening months of January 1917 tested American neutrality to the breaking point. On January 21, Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare on all shipping headed for Britain, neutral or belligerent. The next day, addressing the Senate, Wilson made a final appeal for ending the war: a plea to the warring parties to give up the objective of military victory, enter into a peace agreement, and establish a new community of nations based on democratic principles. The end of the conflict must be founded upon “a peace without victory.”

I am seeking only to face realities and to face them without soft concealments. Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser, a victor’s terms imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only as upon quicksand. Only a peace between equals can last. Only a peace the very principle of which is equality and a common participation in a common benefit. The right state of mind, the right feeling between nations, is as necessary for a lasting peace as is the just settlement of vexed questions of territory or of racial and national allegiance.

Historians debate whether Wilson was blithely indifferent to the nature of the European conflict or a prophet doing battle with the spirit of his age. Nevertheless, after two and half years of industrialized slaughter, Wilson’s proposal didn’t stand a chance of being accepted by the European powers. The British believed that, unlike the United States, they had been sacrificing the best of their youth to defend the principles upon which Wilson was pontificating. Moreover, the “right feeling between nations” would not be achieved after so much suffering and loss. The French leader, George Clemenceau, was characteristically frank about Wilson’s aims: “Never before has any political assembly heard so fine a sermon on what human beings might be capable of accomplishing if only they weren’t human.”

In the end, Germany’s political and military leadership—determined to win the war and impose its will upon the Continent—rendered Wilson’s plea an irrelevance. When the conflict began, German author Thomas Mann, a future Nobel Prize winner, expressed the nationalist mood. The war, he said, was “a purification, a liberation, an enormous hope. The German soul is opposed to the pacifist ideal of civilization, for is not peace an element of civil corruption?” Thus, in December 1916, the German Reichstag approved an Auxiliary Service Law, which effectively conscripted every German male between the ages of 17 and 60. Men not sent to the front would be assigned to a munitions factory or some other industry to help the war effort. Like no other nation in European history, Germany embraced the concept of total war.

In pursuit of this goal, Germany made two of its most fateful mistakes in relation to the United States. The first was the decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, a direct threat to America’s economic interests. The second blunder was the Zimmerman telegram: an absurd plan to support a Mexican war against the United States. In February 1917, British naval intelligence intercepted and decoded the cable to Germany’s ambassador to Mexico City. The British government quickly shared its contents with the US ambassador in London. Within five days the telegram was released to the press. When Wilson called his cabinet together, everyone favored war.

A World Made “Safe for Democracy”

On April 2, 1917, the president asked Congress for a declaration of war. “The world must be made safe for democracy,” he announced. “Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty.” Wilson again made the case for a new international system to replace the old order of Europe:

A steadfast concert for peace can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations. No autocratic government can be trusted to keep faith within it or observe its covenants. It must be a league of honor, a partnership of opinion. Intrigue would eat its vitals away; the plottings of inner circles who could plan what they would and render account to no one would be a corruption seated at its very heart. Only free peoples can hold their purpose and their honor steady to a common end and prefer the interests of mankind to any narrow interest of their own.

Under Wilson’s vision, international peace and security would not rest upon a “balance of power,” but on democratic states binding themselves to treaties extolling universal moral laws. Foreign policy would not be driven by national self-interest, but instead by a sense of universal brotherhood. International disputes would not be resolved by force, but by diplomacy, based on reason, negotiation, and arbitration.

In Wilson’s famous “Fourteen Points” speech, delivered on January 8, 1918, these ideals were taken to their logical conclusion. There were to be no private agreements among nations, but rather negotiations conducted “always frankly and in the public view.” There would be no new arms race; instead, spending on national defense would be reduced “to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.”

The most contentious and problematic idea in Wilson’s speech, expressed in articles 5, 10, and 12, is often neglected: his insistence that the empires of Europe and Asia abandon their colonial holdings and allow their ethnic minorities to choose their own political path. Wilson imagined “a free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims.” Ethnic nationalities under colonial rule, he said, must be granted “an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development.” With the growing strength and prestige of the United States behind him, Wilson was promising nothing less than an absolute right to self-determination.

Many were ready to take him at his word. US mobilization began immediately, and by December 1917, 200,000 Americans were in Europe. Within 18 months, roughly 2 million men joined the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, mostly along the Western Front. The United States was fully committed to the conflict.

In September 1918, 600,000 American troops helped launch the last great offensive of the war—the largest in US history—and among the deadliest for the United States. More than 26,000 American soldiers were killed in the battle, including many from the 91st Division, where the author’s grandfather, Michael Loconte, was deployed as a private. Their orders were unambiguous: “Divisions will advance independently of each other, pushing the attack with utmost vigor and regardless of cost.” Their success is credited with crushing German hopes for victory, producing the Armistice on November 11, 1918.

“America now had one of the largest and most powerful armies in Europe,” writes historian Paul Johnson, “and could convincingly claim that it had played a determining role in ending Germany’s ability to continue the war.” More than that, the United States had entered upon the world stage at a moment of global catastrophe with the purpose of bringing the catastrophe to a decent and honorable conclusion. In this, under Wilson’s leadership, the nation made a contribution to world peace that only it could make.

Wilson’s vision for a new world order, his Fourteen Points speech, was widely circulated in European capitals. It became a kind of moral compass for millions of Europeans, Africans, and Asians. “They are the principles of mankind,” he told the US Congress, “and they must prevail.” They would not prevail, of course, but many in Europe were not prepared to believe it. All over the Continent there were parks, squares, streets and railway stations bearing Wilson’s name. Posters declared, “We Want a Wilson Peace.” Italians knelt in front of his image. In France, the left-wing newspaper L’Humanite devoted an issue to praising the American president. Nationalist movements from Korea to Arabia clung to the Fourteen Points as their lodestar.

Thus when the American president arrived in Paris on December 13, 1918, to hammer out a peace treaty, the United States was at the height of its influence and prestige. Throngs of admirers were there to greet him. They filled the streets, hung from windows, cheered from rooftops. “He was transfigured in the eyes of men,” writes H.G. Wells. “He ceased to be a common statesman; he became a Messiah.”

Many wanted to believe that, under Wilson’s enlightened leadership, democratic ideals of equality and self-government would guide the nations of the world. After a war that had devastated so many lives and national economies, Europeans longed for a redemptive outcome. Wilson, as the leader of the only democracy that seemed capable of negotiating a just and lasting peace, held out the prospect of a new global order. Historian Michael Kazin writes that the American president seemed to believe that “well-meaning Christians could transform the world into a polite, even brotherly place.” Margaret MacMillan summarizes his influence thus: “Wilson kept alive the hope that human society, despite the evidence, was getting better, that nations would one day live in harmony.”

Triumph & Tragedy

Although Wilson would get his “league of honor,” the participating nations would not live in harmony for long. When the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919, the leaders of 44 countries joined the newly created League of Nations. The League’s charter, in important respects, echoed Wilsonian principles: the elimination of armaments “to the lowest point consistent with national safety,” arbitration to resolve international disputes, a cooling-off period during the interim, the preservation of peace as a binding moral commitment. Nevertheless, unchecked aggression over the next two decades would bring the League into widespread disrepute. By 1939, Europe was again at war.

Conventional wisdom blames the harsh terms of German surrender stipulated in the Treaty of Versailles—widely known as “that wicked treaty”—as the guarantor of a second world war. Wilson offered the world a way out of its troubles, we are told, but the European powers wanted vengeance and a return to power politics. Americans, misled by an isolationist Congress, rejected Wilson’s vision and refused to join the League.

There are, however, problems with this interpretation of history, problems that go much deeper than a treaty or an international organization. Wilson proclaimed the “destruction of every arbitrary power anywhere” as an uncompromising goal of American participation. He repeatedly assured his audiences that once the Kaiser and the other “autocratic powers” of the world were toppled, newly liberated citizens would create self-governing democracies. This was the “war to end war,” the “culminating and final war for human liberty.” The world would be rebuilt on “American principles.” Wilson’s political progressivism, his liberal religious views of human potential, his trust in the power of democratic ideals to transform international relations—at times it all smacked of utopianism.

Assuming that all reasonable people desired peace, the American president extrapolated that all civilized nations would share the same goal: the perpetual peace dreamed of by Immanuel Kant. He helped design an international order built on this idea. “This was the sort of peace you got when you allowed war hysteria and impractical idealism to lie down together in your mind, like the lion and the lamb,” concluded the US diplomat George Kennan, “when you indulged yourself in the colossal conceit of thinking that you could suddenly make international life over into what you believed to be your own image.”

All of that may be right. Yet the enormity of the First World War—it’s sustained assault on the moral and religious ideals of the West—created challenges that no statesman could overcome. “Injuries were wrought to the structure of human society which a century will not efface,” observed Winston Churchill, a participant in the war. “The war really did change everything: not just borders, not just governments and the fate of nations, but the way people have seen the world and themselves ever since,” writes G.J. Meyer. “It became a kind of hole in time, leaving the postwar world permanently disconnected from everything that had come before.”

Into this hole—this vortex of suffering, terror, destitution, and disillusionment—stepped the United States. Historians such as Michael Kazin argue that American intervention was a mistake, that it “foreclosed the possibility of a negotiated peace” among the belligerents. Such a revisionist view, however, ignores the determination of Germany and its allies to dominate the Continent: Almost up until the Armistice, more British, French, and American troops were being killed in combat than Germans. The revisionist view rests on the fantastical idea that additional years of remorseless slaughter would have produced a better outcome for European civilization.

Whatever the aims of other nations engaged in the conflict, America’s motives for waging war were honorable, its objectives humane. Even if the United States could have produced the most equitable peace treaty imaginable, it probably would have been resented by a defeated and demoralized Germany. Even the most generous treaty would have been exploited by an embittered anti-Semite, a brooding and hate-filled demagogue by the name of Adolf Hitler.

Perhaps, as George Kennan wrote, the peace at Versailles “had the tragedies of the future written into it as by the devil’s own hand.” But the human condition, by its nature, is crippled by a tragedy of its own making: a disaster that is both moral and spiritual. Individuals, consumed by the lust to dominate, by the demonic, will always appear on the world stage. No paper treaty, no matter how enlightened, can negate the Will to Power.

American involvement in what Churchill called “the world crisis” of the Great War would not prevent the nations of Europe from being overwhelmed by new hatreds in another global conflict. This would become the task of a future generation of statesmen: men and women, awakened to the danger, resolute in their calling, and moved not by visions of power, but by moral purpose. By joining its fate to that of Europe a century ago, the United States can be credited with helping to preserve enough of Western civilization to make the appearance of such statesmen possible, before a hateful and hideous gathering storm could sweep them all away.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

March 8, 2017

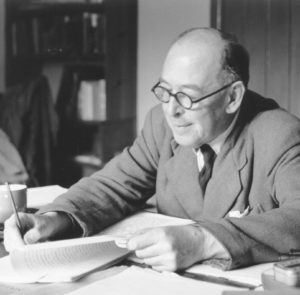

Weekly Standard: C.S. Lewis and the Hound of Heaven

This article was originally posted at The Weekly Standard.

A new one-man play about one man’s spiritual pilgrimage, C.S. Lewis on Stage: The Most Reluctant Convert, opens with a riff against a cruel, indifferent, and seemingly meaningless universe reminiscent of a Woody Allen monologue. “And what is ‘life’?” the protagonist asks in defending his youthful atheism. “It is so arranged that creatures live by preying on another…Creatures are born in pain, live by inflicting pain, and mostly die in pain.”

Playwright, director, and actor Max McLean achieves something rarely seen on stage or screen: a truthful, richly textured, and witty account of religious conversion. C.S. Lewis (1898-1963), the Oxford scholar renowned for works such as The Chronicles of Narnia and The Screwtape Letters, famously abandoned his atheism and became a Christian—but only after a long and tortuous struggle to reconcile his “ruthless dialectic” with the claims of the gospel. McLean traces Lewis’s journey with a script informed by an intimate knowledge of his subject’s thought and writings.

The play, now in its New York debut at the Acorn Theatre, is set in the 1950s in Lewis’s study in Magdalen College. As Lewis recounts his journey, beginning with his childhood, we learn that his mother’s death produced “a deeply ingrained pessimism.” He soon stopped believing in God. His tutor, William Kirkpatrick, was a hard-nosed atheist who helped him develop “intellectual muscle,” which eventually would undermine his materialist outlook. “I at least owe him in the intellectual sphere,” Lewis wrote after learning of his mentor’s death, “as much as one human being can owe another.”

McLean’s rendering draws attention to a singularly important feature of Lewis’s story, often neglected by biographers: his experience of war. A hundred years ago, in 1917, Lewis arrived as a soldier on the Western Front, “the hell where youth and laughter go.” He relates the grim memory of “horribly smashed men still moving about like crushed beetles…it was a ghastly interruption of rational life.” It was an experience which deepened his skepticism.

Yet war also quickened Lewis’s spiritual yearnings. It was during this time that he discovered the writings of George MacDonald, a nineteenth-century minister, mystic, and author of fantasy novels. When Lewis first picked upPhantastes: A Fairy Romance, nothing was further from his mind than Christianity: the cataclysm of the Great War was upending his generation’s cherished beliefs in progress and religion. The book stirred a longing for beauty and goodness, an experience of joy that challenged his materialism. “My imagination was baptized,” he says. “The rest of me took a bit longer.”

In a smart production that uses portraits of friends and authors who helped Lewis in his quest—from W.B. Yeats to G.K. Chesterton—we overhear a fateful conversation with J.R.R Tolkien, another Oxford don and a Catholic believer. On an evening in September 1931, on Addison’s Walk near Lewis’s college, the two friends talked until 3 a.m. about whether Christianity was simply a myth, like the pagan stories Lewis enjoyed about dying gods sacrificing themselves for a noble cause. “Jack, the story of Christ is a myth: working on us in the same way as other myths, but with one extraordinary difference. It really happened.” Lewis would regard his exchange with Tolkien as an intellectual breakthrough.

Whether moving from his armchair to his desk, or pouring himself a stiff drink, McLean delivers a performance that is worthy of its subject: learned, trenchant, wry, honest, and humane. “The Absolute had arrived, making a nuisance of itself,” Lewis explains, compelling him to do a moral inventory. “What I found appalled me—depth after depth of pride and self-admiration—a zoo of lusts, a bedlam of ambitions, a nursery of fears, a harem of hatreds. My name is legion.”

The play captures the complexity of Lewis’s struggle to believe, yet avoids the clichés and sanctimony that usually attend religious biographies. True to Lewis’s own account, McLean portrays a man almost embarrassed by his conclusions: even Lewis’s decision to adopt theism rendered him “the most dejected, reluctant convert in all England.” The ultimate step of faith comes unexpectedly, during a country ride with his brother in the sidecar of a motorcycle. “When we set out I did not believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God,” Lewis explains. “When we reached the zoo I did.”

C.S. Lewis on Stage delivers something truly novel in modern theater: a story about an immensely creative mind, through reason and imagination, arriving at the threshold of faith. “A cleft has opened in the pitiless walls of the world, and I have been invited to follow our great Captain inside,” Lewis says. “The following Him is, of course, the essential point.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

March 2, 2017

Providence: Lessons from FDR’s Russia Policy

This article was originally posted at Providence.

In his address to Congress this week, President Trump noticeably declined to mention his Byzantine relationship with Russia. The president defends his friendly posture toward Russia—including his campaign’s high-level contacts with Moscow, his praise of Vladimir Putin, and his selection of a Secretary of State with close business ties to the regime—as an effort to win Russian cooperation in the fight against the Islamic State. “Having a good relationship with Russia is a good thing,” Trump explains, “not a bad thing.”

We’ve heard arguments like these before, by the first American president to grant diplomatic recognition to the Soviet Union: Franklin D. Roosevelt. Against the objections of State Department hawks, FDR reached out to Joseph Stalin in 1933, the first year of his presidency. Twelve years later, after a campaign to convert the communist dictator into “Uncle Joe,” the noble war-time ally, the president’s pro-Russia policy was in shambles.

Like Mr. Trump, who brushes aside allegations of Putin’s involvement in war crimes and political assassinations, Roosevelt’s policy depended on a willful disregard for the most brutal acts by the regime in Moscow.

At the moment that FDR established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, for example, Stalin was engaged in a terror campaign against the nation’s farmers. In 1929, he ordered the “collectivization” of agriculture, but the “kulaks,” land-owners who belonged to the middle class, resisted. The state murdered them—many were put on trains bound for death camps—and seized their grain. The result was a man-made famine and mass starvation. By the spring of 1933, the famine was killing 25,000 people a day in the Ukraine. It is estimated that between 10 million and 14 million Soviet citizens suffered unnatural deaths between 1929 and 1934.

Though aware of the Soviet policy, Roosevelt made sure no one in the White House or the State Department discussed it publicly. “I trust that the relations now established between our peoples may forever remain normal and friendly,” he wrote to the Kremlin in November 1933, “and that our Nations henceforth may cooperate for their mutual benefit and for the preservation of the peace of the world.” Historian James Mace, former director of the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine, concluded that the Roosevelt administration participated in “perhaps the single most successful denial of genocide in history.”

From the moment that Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, in June 1941, the transformation of Stalin into a champion of democratic values began. At a White House dinner, Roosevelt prodded Hollywood producer Jack Warner to make a propaganda film, Mission to Moscow, based on the bestselling book by Joseph Davies, his former ambassador to the Soviet Union. In the 1943 movie, Stalin is portrayed as a courageous, pipe-smoking defender of the Russian people. Davies himself—who throughout the 1930s rationalized Stalin’s purges and show trials as necessary to national security—appears in the film’s opening credits to help dispel “prejudice and misunderstanding” about the Soviet Union. Author Saul Bellow, a man of the left, once called Davies “one of the most disgraceful appointments in diplomatic history.”

In 1943, the same year Hollywood released Mission to Moscow, mass graves were discovered by the German military in a forest in Soviet-controlled eastern Poland. On Stalin’s secret orders, the Red Army had executed at least 22,000 people: officers, doctors, professors, lawmakers, and priests. The largest massacre occurred in Katyn Forest. Each officer’s hands were tied behind his back before being shot with a single bullet through the base of the skull.

Under pressure, Roosevelt instructed his emissary to the Balkans, George Earle, to look into the incident. Convinced of Soviet guilt, Earle presented his evidence to the president. FDR dismissed the story as “German propaganda and a German plot.” Forbidden to publicly release his findings, Earle was transferred to Samoa. As historian Allen Paul observes: “Roosevelt himself was determined that US handling of the Katyn controversy should not offend the Soviets.” After decades of denial, official Soviet documents released in 1992 showed that Stalin was directly involved in the crime.

Roosevelt believed there were vital US interests at stake in maintaining strong relations with the Soviet Union: we needed their help to defeat the Nazis, and we wanted their help in the war against Japan.

The problem for the president—and for the American public—was that he seemed to believe the utterly false portrait of Stalin he helped to create. After his first meeting with the Soviet leader, in 1943 in Tehran, Roosevelt concluded: “I believe he is truly representative of the heart and soul of Russia; and I believe that we are going to get along very well with him and the Russian people—very well indeed.”

Yet barely fourteen months later, the dream of Russian cooperation with the West was turning into fairy dust. Almost immediately after the Yalta Conference in February 1945—where Stalin committed himself to a democratic future for Europe—the Soviet Union consolidated its control over those nations “liberated” by the Red Army. There would be none of the promised democratic elections in Poland or Eastern Europe. In March, FDR complained bitterly to an aide: “He has broken every one of the promises he made at Yalta.” In May, alarmed at Soviet designs on the continent, Winston Churchill actually instructed his military advisors to devise “Operation Unthinkable,” a plan to attack the Soviet Union.

Like Roosevelt, Donald Trump seems to believe that the truth about Russian behavior can become a prostitute to political necessity. “It is permitted in time of grave danger,” FDR explained, “to walk with the devil until you have crossed the bridge.” The Trump White House would do well to recall another old maxim: “He who dines with the devil had better have a long spoon.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

February 16, 2017

Providence: Executive Orders, Nativism, and National Security

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Warning about a rising tide of xenophobia, the American Civil Liberties Union assailed the White House’s most recent executive order as “the greatest deprivation of civil liberties in this country since slavery.” The administration that the ACLU had in its sights, however, was not that of Donald J. Trump. It was that of Franklin D. Roosevelt, champion of political progressivism.

Seventy-five years ago, on February 19, 1942, FDR issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the internment of tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans. The order came barely two months after Japan’s surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, which shocked the nation out of its isolationist complacency. Challenged in court, Roosevelt’s authority was upheld by the equally progressive Supreme Court of Justice Earl Warren, by a vote of 6-3. As President Trump’s critics warn of a constitutional crisis over his attempt to temporarily ban immigrants from seven Muslim-majority countries, they might reflect on the full-throated support by liberal elites for far more draconian policies—policies fueled not only by fear but by the intoxicating effect of unchecked executive power.

Hagiographic FDR biographers—Doris Goodwin Kearns and Robert Dallek chief among them—want us to believe that Roosevelt “reluctantly” signed the executive order, against his better instincts, because of pressure from his advisors. Nonsense. Gen. Mark Clark, the Army’s deputy chief of staff, Attorney General Francis Biddle, and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover all opposed the policy. Harry Stimson, Secretary of War, after a visit with Roosevelt in February, recorded in his diary: “He was very vigorous about it.” As Thomas Fleming notes in The New Dealers’ War, the president sought even more aggressive action than his cabinet. After issuing the order, he told Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox that he wanted Hawaii’s 140,000 Japanese evacuated as well, and was not worried about “the constitutional question.” (Military leaders objected—they needed the skilled labor of the Japanese in Hawaii for the war effort—and prevailed over the White House.)

Not surprisingly, FDR’s presidential library, though acknowledging the executive order as “a blemish on Roosevelt’s wartime record,” also shifts the blame to other actors. Rafael Medoff, director of the David S. Wyman Institute of Holocaust Studies, says the museum portrays the president “as the victim of irresistible pressure from his military advisors and public opinion.” FDR admirers tend to take the same line.

But that propagandistic version of events ignores the fact that Roosevelt was quite willing to overrule his military advisors on other war-related matters. Moreover, rather than being a victim of public opinion, FDR was a willing slave to it. Although there were security risks from Japanese resident aliens, his policy was emblematic of a “New Deal” presidency prepared to violate constitutional norms when it sensed no political cost for doing so.

Moreover, Roosevelt already had sought and won an unprecedented third term as president. After he first assumed office in 1933, in the middle of the Great Depression, he grew accustomed to using a national crisis to expand the powers of government. Thus FDR’s order gave the military broad authority to remove “any and all persons” from a 50- to 60-mile-wide coastal area stretching from Washington state to California, and to forcibly transport them to internment camps in the interior of the country. At least 120,000 Japanese-Americans living in the region were swept up in the net. The order was also applied to U.S. citizens of German and Italian descent: about 11,000 German-American residents were arrested and more than 5,000 interned, while roughly 3,200 Italian-Americans were arrested, about 300 interned.

The policy enjoyed tremendous popular support. The liberal press, enamored with FDR’s New Deal, was predictably compliant. The New York Times editorial page—which has savaged President Trump’s immigration ban as “cowardly and dangerous”—was not exactly a profile in courage during the Roosevelt era. The Times editors offered the meekest of criticism, lamenting that the Japanese internment was causing a shortage of lilies—since lily bulbs, according to the editors, usually came from Japanese gardeners. “We’re even short of cut flowers,” the paper complained.

A 1980 congressional commission report found that FDR’s internment policy, stoked by racism and war hysteria, represented “a failure of political leadership.” We are still learning about the human costs of that failure. In the fog of war, Roosevelt’s executive order turned thousands of patriotic, law-abiding citizens into suspected saboteurs. It left them, in the words of the executive order, “subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.” Thousands of families were separated, traumatized, and persecuted. Livelihoods were ruined. Entire communities were uprooted. “Most of them, citizens and aliens alike, were fiercely patriotic,” writes Richard Reeves in Infamy: The Shocking Story of the Japanese American Internment in World War II. “Guarded by soldiers in machine-gun towers, none of them were charged with any crime against the United States.”

President Trump’s executive order, blocked by the Ninth Circuit Court, has been widely criticized as discriminatory, ill-conceived, and clumsily executed. A little historical perspective, though, might embarrass some of the violent and vitriolic protestors: compared to the racist, dehumanizing, and socially destructive policies of Franklin Roosevelt—icon of modern liberalism—Trump’s three-month travel ban looks like afternoon tea at the Ritz-Carlton.

None of this is a defense of either the tone or posture of the Trump White House toward immigrants from Muslim-majority countries. A policy that cannot distinguish between desperate refugees fleeing the violence of radical Islam and the perpetrators of that violence is not merely an embarrassment; it is a morally and spiritually debased policy. Nevertheless, liberalism has generated far greater assaults on our democratic ideals than anything yet proposed by the current occupant of the White House.

Progressives now claim a vigilant—if not belated—regard for the constitution. We’ll be watching.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

February 15, 2017

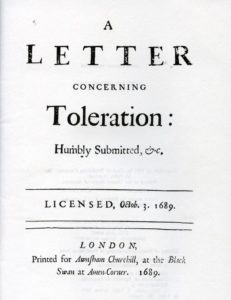

National Interest: Can John Locke Save Political Islam?

This article was originally posted at The National Interest.

“I NO sooner perceived myself in the world,” wrote English philosopher John Locke, “than I found myself in a storm.” Locke was referring to the maelstrom of religious fanaticism and intolerance that was tearing apart the social fabric of post-Reformation Europe. Born in 1632, Locke’s life encompassed one of the most turbulent periods of European history. The problem was not only the enmity and power struggles between Protestants and Catholics. Despite an official end to the wars of religion with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, militant Christianity could still destabilize governments, provoke mob violence, persecute religious dissenters and create a refugee crisis in the heart of Europe.

We can hardly ignore the parallels between Locke’s world and our own: the Syrian Civil War, the rise of the Islamic State, the horrific assaults on religious minorities, the massive flow of refugees from the Middle East, and the widening conflict between Sunni and Shia Muslims. The repression and violence in the wake of the Arab Spring has exposed the fundamental crisis in modern Islam: a culture of intolerance reminiscent of Europe’s legacy as a persecuting society.

When President Obama addressed Muslims worldwide in his celebrated 2009 speech in Cairo, he praised Islamic history for demonstrating “the possibilities of religious tolerance.” Speaking before the United Nations five years later, his mood was considerably darker. Though denying that America was at war with Islam, Obama warned of “the cancer of violent extremism that has ravaged so many parts of the Muslim world.” Even President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt speaking at Al Azhar University in January 2015, made an impassioned plea for “a religious revolution” to stymie extremist Islam that has “antagonized the entire world.”

…

Read the rest of this article at The National Interest.

January 21, 2017

The Times: Making America great again means welcoming Muslims

This article was originally posted at The Times.

The presidency of Donald Trump, barely twenty-four hours old, has left many Muslims in the United States anxious about their futures. Although Trump has backed off his campaign pledge to ban Muslim immigration outright, talk of a Muslim “registry” persists. Some members of his cabinet, not to mention many of his supporters, seem to regard Islam as a threat to liberal democracy. Conservative Christians, a key Trump constituency, are among the staunchest advocates of curtailing immigration from Muslim-majority countries.

There is a certain irony here, especially given the Trump mantra to “make America great again.” The architects of the American experiment tethered its political ideals to religious belief: they draw on the Christian tradition as a foundation for a political society upholding justice and equity for people of all faiths.

In this the American Founders looked to thinkers such as the seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke, who lived during a similar season of anti-Muslim fervor. The Anglican Church, to which Locke belonged, viewed itself as a bulwark against the advances of Islam and the Ottoman Empire. To many of Locke’s contemporaries, Muslims were “Scorpion Locusts” who advanced “the Satanical Kingdom of Mahomet.” Church and state were united in their hatred of the Turks, who were narrowly defeated on the battlefield on September 11, 1683, during the siege of Vienna.

Yet two years later, in the winter of 1685, Locke drafted A Letter Concerning Toleration, which advanced a concept of equal rights for Europe’s most despised religious minorities—including Muslims.

As Locke saw it, the principle of equity offered the best hope for civic peace: “But those whose doctrine is peaceable, and whose manners are pure and blameless, ought to be upon equal terms with their fellow-subject…Nay, if we may openly speak the truth, and as becomes one man to another, neither Pagan, nor Mahometan, nor Jew, ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth, because of his religion.”

Here is the radical idea of impartial justice, applied equally to all citizens, regardless of creed. Here is the beginning of the concept of a secular commonwealth. Universally embraced by the American Founders, Locke’s Letter became part of the canon of the liberal democratic tradition.

Near the heart of Locke’s argument, however, is a deeply Christian approach to the challenge of religious pluralism. Though considered an early Enlightenment figure, Locke never abandoned his belief in Christ’s redemptive purpose for all mankind. As he argued in his Letter, the idea of religious liberty for people of all faiths was “agreeable to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and to the genuine reason of mankind.” As Locke wrote elsewhere, Jesus “opened the kingdom of heaven to all equally, who believed in him, without any the least distinction of nation, blood, profession, or religion.”

Other reformers had interpreted the teachings of Jesus as an argument for toleration. But until Locke, no one had combined an appeal to the moral life of Christ—“the Captain of our salvation”—with such a broad and inclusive vision of a just society. According to Locke, the message of divine mercy, intended for all, carried social and political implications.

Thus Locke began his Letter with an appeal to religious leaders, the custodians of the conscience of Europe: “I esteem that toleration to be the chief characteristical mark of the true church.” From the onset of the Protestant Reformation, which shattered the unity of Christendom, arguments raged over which religious tradition bore the marks of the “true church.” Locke helped to transform the debate by putting the emphasis on acts of compassion and forbearance toward one’s enemies. “We must not content ourselves with the narrow measures of bare justice,” he wrote. “Charity, bounty, and liberality must be added to it.”

The American presidential election has exposed a deficit of charity toward our Muslim neighbors, whether here at home or toward those hoping to find refuge in the West. There are legitimate concerns about radical Islamists infiltrating and subverting our open, democratic societies. Locke, the father of modern liberalism, shared them. He insisted that religious doctrines be “peaceable”—that they conform to liberal and constitutional norms. No one should be tolerated, in other words, who openly threatened civil society.

Most Muslims, especially those fleeing the chaos and violence of war, don’t belong in this category. They need advocates, not accusers. They need more defenders who are devoted, in Locke’s words, to “the perfect example of the Prince of Peace.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

January 17, 2017

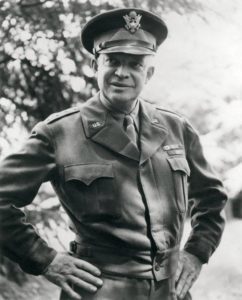

BBC Interview: What Eisenhower Might Think of Trump

I was interviewed by the BBC about how a Trump presidency might stack up to that of Dwight D. Eisenhower—a leader with no prior political experience, but arguably one of the best prepared men imaginable to assume the presidency in a time of crisis.

http://www.josephloconte.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/O-DONOGHUE-EISENHOWER-TRUMP.mp3

January 9, 2017

Providence: Obama’s Farewell Address: Goodbye to All That

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Perhaps the best-known memoir of post-war disillusionment is the 1929 book Goodbye to All That. In it, poet Robert Graves laid bare the confusion, cynicism, and loss of innocence brought on by the mechanized slaughter of the First World War. “Pessimism made everyone superstitious,” Graves wrote, “and I found myself believing in signs of the most trivial nature.”

That’s a pretty apt description of the psychological mood of Barack Obama as he ends his eight-year presidency and prepares to deliver his farewell address to the nation.

The pessimism arrived early. Despite his flowery promises about “hope and change,” Obama entered office embodying the most ambivalent view of American power since the end of the Vietnam War, which ushered in a similar season of post-war gloom. His years in the White House served only to deepen an emotional retrenchment: a seemingly scornful view of U.S. engagement in the world which, not unlike the characters in Graves’s book, underwrote a superstitious belief in the power of rhetoric over action.

Russian aggression in Ukraine, the premature withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq, the astonishing rise and success of the Islamic State, and the ongoing human catastrophe of the Syrian civil war—each of these failures of American foreign policy can be traced, at least partially, to Obama’s facile belief that mere words can tame tyrants, protect the innocent, and bring peace.

The bankruptcy of Obama’s faith, his trust in empty diplomacy for its own sake, was most painfully exposed in the horror of Aleppo. The Syrian city, one of the last rebel holdouts against Bashar al Assad, was not defeated by the Syrian army. It was destroyed in a campaign of barbarism led and subsidized by Russia, Assad’s chief patron. While Obama intoned about the sin of becoming “bystanders to injustice,” the inhabitants of Aleppo were being ravaged by war crimes legitimized by a farcical “peace process” orchestrated by his Secretary of the State. Not even air assaults on hospitals and aid convoys could shake the president loose from his superstitions.

Thus, even Leon Wieseltier of the Brookings Institution, a longtime editor of the New Republic and a man of the left, concludes that Obama’s high-minded inaction has left America “weakened and disgraced” in the eyes of the world:

As a direct or indirect consequence of our refusal to respond forcefully to the Syrian crisis, we have beheld secular tyranny, religious tyranny, genocide, chemical warfare, barrel bombs and cluster bombs, the torture and murder of children, the displacement of 11 million people, the destabilization of Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, the ascendancy of Iran in the region, the emergence of Russia as a global power, the diminishment of the American position in the world, the refugee crisis in Europe, the resurgence of fascism in Europe and a significant new threat to the security of the United States. It is amazing how much doing nothing can do, especially when it is we who do nothing.

No wonder Obama, in his final State of the Union address, in January 2016, did not breathe a single word about the Syrian refugee crisis—not a word, in a 6,100-word speech, about the worst humanitarian disaster since the end of the Second World War.

What could Obama possibly say now, in his farewell address, in light of these geo-political realities? What words of advice could he credibly offer the next commander in chief? What counsel from a president who, despite two terms in office, appears to have learned nothing about the indispensable role of American leadership in promoting peace and security?

The president’s speechwriters would be mystified by the words of Ronald Reagan, who also came to office during a time of American self-loathing. Reagan repudiated this mood in word and deed. Thus he could claim, with justification, that under his leadership there was a recovery of morale and moral purpose: “America is respected again in the world, and looked to for leadership.” Reagan ended his eight years in office with the same fierce attachment to American exceptionalism—America as “a shining city on a hill”—that had launched him into public life.

“And how stands the city on this winter night?” Reagan asked in January 1989. “She’s still a beacon, still a magnet for all who must have freedom, for all the Pilgrims from all the lost places who are hurtling through the darkness, toward home.”

Barack Obama entered politics devoid of this belief. Instead, he projected a posture of agnosticism—even cynicism—about America’s capacity to defend international norms of justice, democracy, and human rights. From the very beginning, Obama said goodbye to all that, and he governed accordingly. And, now, finally, we say goodbye to him, a goodbye that seems a long time coming.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

December 26, 2016

Georgetown Journal: Judgment Day: The Collapse of Soviet Communism

This article was originally posted at Georgetown Journal.

The peaceful disintegration of the Soviet Union twenty-five years ago, on December 26, 1991, astonished nearly everyone in the democratic West. Up until the collapse of its empire, the Soviet Union appeared to have an inexhaustible reservoir of influence and power. Ronald Reagan might have believed—as he predicted in a 1982 speech before the British Parliament—that Marxism-Leninism would be discarded on the “ash heap of history.” But almost no one agreed with him. Even Richard Pipes, a Reagan advisor and a leading Russia historian, called the Soviet Union’s demise “unexpected.”

The resurgence of Russian belligerence, whatever its causes and objectives, makes it vital to remember how profoundly mistaken the majority of Western intelligentsia was about Soviet communism—and why.

Consider a sampling of opinion throughout the 1980s. Columbia University’s Seweryn Bialer insisted that “the Soviet Union is not now nor will be during the next decade in the throes of a true system crisis, for it boasts enormous unused reserves of political and social stability that suffice to endure the deepest difficulties.” MIT economist Lester Thurow called it “a vulgar mistake to think that most people in Eastern Europe are miserable.” Harvard’s John Kenneth Galbraith predicted smooth sailing ahead for the Soviet economy: “The Russian system succeeds because, in contrast to the Western industrial economies, it makes full use of its manpower.”

After Reagan’s Westminster speech, historian Robert Byrnes collected essays from thirty-five experts on the Soviet Union—all from the American academy—in a book entitled After Brezhnev. Their conclusion? The Cold War was here to stay. “The Soviet Union is going to remain a stable state, with a very stable, conservative, immobile government… We don’t see any collapse or weakening of the Soviet system.”

The experts focused on external and materialistic signs of strength: small but steady growth in Soviet GDP and incomes, vast military expenditures, a seemingly stable empire, and a 5-million-strong military to patrol it. At a deep cultural level, however, the moral rot of Soviet society was taking its toll.

The decline was clear to those who took seriously the longings for political and religious freedom: the voices of Soviet dissidents and democratic resistance leaders in Eastern Europe. Pope John Paul II not only legitimized these voices during his historic 1979 trip to Poland, but also helped to catalyze them. As he told a crowd of over a million people in Warsaw’s Victory Square:

Man is incapable of understanding himself fully without Christ. He cannot understand who he is, nor what his true dignity is, nor what his vocation is, nor what his final end is…Therefore, Christ cannot be kept out of the history of man in any part of the globe, at any longitude or latitude of geography. The exclusion of Christ from the history of man is an act against man.

Here is the dimension often missing in statecraft—missing, that is, among many of our political, governmental, and academic specialists. It is the power of religious belief to champion human rights, to defend the individual against the State, and to supply the courage to transform political societies.

Atheistic communism revealed itself as an assault on human nature. “It is the Soviet Union that runs against the tide of history,” Reagan told his British audience, “by denying human freedom and human dignity to its citizens.” Like Reagan, Britain’s Margaret Thatcher understood the spiritual dynamic. During her 1988 trip to Poland, Thatcher urged Poland’s communist leadership to allow democratic reforms so that Poland and other Eastern European countries could “share fully in Europe’s culture, Europe’s freedom, and Europe’s justice—treasures which sprang from Christendom.” Western support for Poland’s Solidarity Movement, Reagan and Thatcher said, aimed to tap into the “spiritual energies” of those living under communist rule. This notion was the cornerstone of the Reagan administration’s 1983 national security strategy toward Eastern Europe “to loosen Moscow’s hold on the region while promoting the cause of human rights in individual East European countries.”

Secular-minded analysts tend to ignore the role of religion in international affairs. The CIA—which in 1979 failed to discern the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Iran—shared in the myopia about the Soviet Union’s weakness. As late as the summer of 1988, the CIA excluded the possibility of any significant changes in the satellite states of the Soviet Empire:

There is no reason to doubt [Gorbachev’s] willingness to intervene to preserve Communist Party rule and decisive Soviet influence in the region. For Gorbachev, as for his predecessors, the importance of Eastern Europe can hardly be exaggerated. It serves as a buffer zone, military and ideological, between the USSR and the West, a base for projecting Soviet power and influence throughout Europe and a conduit for Western trade and technology. It is a key external pillar of the Soviet system itself…There is no reason to doubt ultimate Soviet willingness to employ armed force to maintain Party rule and preserve the Soviet position in the region…The Berlin Wall will stay.

It is no coincidence that Poland created the first crack in the Iron Curtain. It was Poland that gave birth to Solidarity, the first independent trade union in the Eastern Bloc. Backed by the Vatican, Solidarity attracted millions of members, transforming itself into a spiritual and political revolution. In June 1989, when Poland’s communist leadership agreed to hold free elections, Solidarity candidates won 99 out of 100 seats in the legislature. “I blame the church,” complained an embittered General Wojciech Jaruzelski. “They are the main culprits.” The fire was lit: before the end of the year, virtually the entire Eastern Bloc—including Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany—had broken away from the Soviet Union. The Berlin Wall came down.

The desire for freedom soon overwhelmed the Soviet Union itself. By March 1990, the Baltic states declared their independence from Moscow. Boris Yeltsin, a democratic reformer, was elected president of Russia and quit the Communist Party. Kremlin hardliners tried to cling to power in a failed coup, but their totalitarian cause was hopelessly discredited throughout the empire. Mikhail Gorbachev resigned as General Secretary on Christmas Day in1991. The next day, the Supreme Soviet declared the end of the Soviet Union. The Soviet flag, which had flown over the Kremlin for seventy years, was mothballed.

Today’s revisionists claim all of this was inevitable: nothing the West did during the Cold War to challenge the Soviets made a difference. As Strobe Talbott, president of the Brookings Institution, once boasted: “The doves in the great debate of the past 40 years were right all along.” The reality, however, is that the doves were desperately wrong; they were naïve about the perverse nature of communism and indifferent to the human desire for freedom. None of the revisionists, in fact, predicted the sudden meltdown of the Soviet Union. Just the opposite. They belittled the West’s efforts to support Solidarity. They rejected Reagan’s characterization of the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” and denounced his policies to exploit its moral and spiritual bankruptcy.

In this sense, Mikhail Gorbachev possessed greater insight into the fatal weaknesses of Soviet communism than many of his Western admirers. Gorbachev realized that the best and brightest of Soviet society had abandoned communism because “it does not respect the man, [it] oppresses him spiritually and politically.” During his remarkable address on Christmas Day announcing his resignation, Gorbachev explained: “This society has acquired freedom. It has been freed politically and spiritually, and this is the most important achievement that we have yet fully come to grips with.”

This achievement, the liberation of half a continent from Soviet totalitarianism, defied the purveyors of doubt and defeatism. It was made possible because the forces of freedom, buoyed by Western leadership, did not shrink back at the moment of crisis. Today, Russia and the West may be heading toward a new crisis—another contest between freedom and authoritarianism. If the West is to prevail, it must learn to draw strength again from the deepest wells of its democratic faith.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

Joseph Loconte's Blog

- Joseph Loconte's profile

- 70 followers