Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 2

October 24, 2024

The American Spectator: The Republic of Venice Offers a Model for a Fractured America

This article was originally posted at The American Spectator.

VENICE, Italy — When Gasparo Contarini surveyed the political chaos of Italy’s city-states in the 1500s, he grew somber: “It is evident that almost every city in Italy, whether it is governed by a popular order or even by one of its own patrician citizens, eventually falls into the tyranny of some faction of its citizens.” Nevertheless, for Contarini, a lawmaker and diplomat, his beloved Republic of Venice offered an alternative: a dazzling and enduring model of self-government. “For this reason,” he said, “our ancestors decided that they had to try with all their might to prevent their Republic, splendidly organized and governed by excellent laws, from being afflicted by some such monster.”

The monster of political factions is stalking the American republic, as the Founders feared. Writing in The Federalist Papers, James Madison regarded the threat of factions — what we call tribalism — as “the mortal disease” of self-government.

Not since the era of the Vietnam War and the violence following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. has the nation been so deeply and angrily divided. Never have Americans registered such levels of distrust — and disgust — with the core institutions shaping public life. “Trust in all of these institutions, all the pillars that hold up the edifice of American democracy and society, is crumbling,” writes Wall Street Journal editor Gerard Baker in American Breakdown. The collapse of trust, Baker observes, is fueling social unrest and political violence.

It was precisely this outcome that the Founders sought to avoid. Why do most forms of government collapse into social chaos, violence, and tyranny — and why do others endure? These were the questions that occupied the Founders in Philadelphia during the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

As Alexander Hamilton neatly framed the issue in The Federalist Papers, the American people were uniquely positioned “to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.” Answering that question became urgent not only because of the failings of the Articles of Confederation. In 1776, Edward Gibbon began releasing volumes of his magisterial work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The fearsome story of Rome was near the forefront of their minds.

For more than a thousand years, throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Venice distinguished itself as a durable and prosperous republic in an era of monarchs, despots, powerful families, and political assassinations.

No American political thinker studied the history of republics more carefully than John Adams. In Thoughts on Government, Adams notes the longevity of the Venetian republic, “longer than any other that is known in history.” He was characteristically frank about its difficult journey toward republicanism, noting that factions arose early in its development. “For a long course of years after this,” he wrote, “the Venetian history discloses scenes of tyranny, revolt, cruelty, and assassination, which excite horror.”

They avoided the kind of moral cynicism that Machiavelli later endorsed. But they confronted, with sober realism, an ancient problem: what Friedrich Nietzsche would call the Will to Power. They were pragmatists. They took stock of their difficulties and created different and distinct sources of political authority: the “mixed” constitution described by Aristotle.

Executive power resided in a single individual, the Doge, who functioned like a monarch and symbolically represented the state — most laws were published under his name. His massive palace, the Palazzo Ducale, is a breathtaking display of opulence put toward a political purpose. The courtyards, corridors, and council halls (not to mention its hidden chambers) made it the physical powerhouse of government. Nevertheless, the Doge never became an absolute monarch — or he was removed or assassinated for trying.

“There has been an uncommon solicitude all along to restrain his power,” observed Adams. Indeed, the Doge was constrained by the city’s aristocratic class, exclusively men of noble birth and of education and virtue, presumably. These patricians constituted the Senate, which included a collegio, a kind of steering committee that helped to set the legislative agenda. Senators openly debated all the major issues facing the republic, with strict rules of debate: no personal insults against political opponents. “The whole business of governing the Republic,” wrote Contarini, “belongs to the Senate.”

Yet the Doge and the Senate were also held in check by the Great Council, the sovereign assembly of the Republic. It was the Great Council that elected the Doge and members of the Senate and approved legislation. It was a republican body in that its members — open to all patricians over the age of 25 — had equal voting power. They voted in silence, a procedure described by foreign visitors as “a spectacle of majesty.”

The Great Council theoretically represented the vast majority of Venetians, the popolo, who could not directly participate in political life. Nevertheless, membership in the Council gradually expanded, and by 1300 A.D. it had more than 1,100 members — or about 1 percent of the Venetian population (compared to the U.S. government with a representation of .0002 percent of the population). Thus, the Great Council emerged as the most representative political body in the world.

“The fact is that the greatest crimes are caused by excess and not by necessity,” Aristotle wrote in Politics. “Men do not become tyrants in order that they may not suffer cold.” The Venetians embraced this sober view of human nature. They designed a government whose constituent parts deliberated and determined all domestic and foreign policy issues. Yet none had absolute power, but rather were held in check by the other.

No wonder contemporary observers praised Venice for surpassing Athens, Sparta, and Rome as a model of a just and stable government. As Contarini expressed it in The Republic of Venice: “With this balance of government, our Republic has been able to achieve what none of the ancient ones did, however illustrious they were.” Adams agreed with that assessment: “Great care is taken in Venice to balance one court against another and render their powers mutual checks to each other.” As Harvard historian James Hankins summarizes it: “Venice became the prime example of the capacity of modern societies to surpass the ancients in political wisdom.”

In the stifling summer of 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention needed all the political wisdom they could get. The 13 newly independent states already were at odds over issues — including slavery, the nature of the presidency, and the power of the federal government — that threatened to extinguish their experiment in democratic freedom before it began.

They relied not only on the insights of the ancients, or the Italian city-states such as Venice. The Founders were determined to design a Constitution that enshrined the rights expressed in the Declaration of Independence: a government based upon a belief in universal, unalienable, and natural rights. And in this, like no other political revolution in history, they grounded these rights in the concept of a just and loving God. “God who gave us life gave us liberty,” Thomas Jefferson declared. “Can the liberties of a nation be secure when we have removed a conviction that these liberties are the gift of God?”

It was the Doge who insisted that the body of Mark the Evangelist, smuggled into the city in 828 A.D., be placed in a chapel adjacent to his palace. Mark’s chapel became a great basilica, the Basilica di San Marco, as grand a church as any in Christendom. Its proximity to the seat of political power sent an unmistakable message: The concept of the republic — a government antithetical to despots and tyrants — had the moral authority of the Catholic Church behind it.

“We pray God the Almighty to preserve it safely for a long time,” wrote Contarini. “For, if one can believe that anything good for men derives from God the Immortal, it must be considered more certain that this has happened to the city of Venice by divine intervention.”

In the United States, however, many Americans have lost all respect for their governmental institutions. The presidency, Congress, the administrative state, and the intelligence community: Their moral authority has been decimated by their abuse of power, deception, partisanship, and contempt for the common good.

Meanwhile, like no other period in its history, the United States is putting Jefferson’s political maxim to the test. The erosion of belief in God — and in the Moral Law that originates in God — is surely one of the sources of the divisions and hatreds that threaten to tear the republic apart.

The moment is ripe to recall the vigilance of the Venetians to safeguard their political unity. “In their view,” Contarini explained, “they should fear nothing so much as an internal enemy and hostility between citizens.”

—

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is a Presidential Scholar in Residence at New College of Florida and the C.S. Lewis Scholar for Public Life at Grove City College. He is the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War.

October 8, 2024

The West Is Abandoning Its Free-Speech Legacy

Venice — Not long after the Gutenberg press was up and running, a publisher in Venice announced his life’s ambition: to make sure that people devoted to the pursuit of knowledge and truth could get their hands on affordable books. “Until this supply is secured,” he declared, “I shall not rest.”

Aldo Manuzio, who opened his print shop in 1494, kept true to his word. His publishing house, the Aldine Press, became so successful that he sparked a publishing revolution. By the 1500s, Venice was producing and selling more books than any other city in Europe. As a result, the Venetians helped to introduce into the West the concepts of free speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of conscience: the foundational rights of a healthy democratic society.

Yet today, 500 years later, many educated elites have turned their backs on this legacy of liberty. New forms of censorship, the shutting down of academic debate, the cancel culture: Modern attempts to suppress the free exchange of ideas make 16th-century Venice look like a citadel of classical liberalism.

Consider: During the 1500s, more than 690 Venetian printers and publishers generated at least 15,000 titles, which had an average press run of about 1,000 copies. Some historians estimate that the Venetian presses produced more than 35 million books. Printers worked 12 to 16 hours a day, printing one sheet every 20 seconds. Venetian women, such as Antonia Pulci, wrote and published books and worked as editors, illustrators, and proofreaders. In the universe of publishing, Venice was the North Star.

Situated in the middle of a tidal lagoon, Venice has always astounded visitors with its waterways, its architecture, its incomparable Piazza San Marco. Yet Alessandro Marzo Magno, author of Bound in Venice: The Serene Republic and the Dawn of the Book, describes medieval Venice thus: “What struck foreign visitors most were the books: the dozens and dozens of bookmaking workshops that were gathered here in a density unequaled anywhere else in Europe.” The Venetians effectively invented the modern bookstore.

What were they selling?

The discovery of a ledger in 1810, in the attic of the Basilica of San Marco, was revelatory: a comprehensive list of 12,934 book sales, from 1484 to 1487, from a single book shop in Venice. Educated Venetians were not, for the most part, consuming the thin gruel that dominates much of our publishing today. There were lots of books on mathematics, rhetoric, medicine, and natural history. About 20 percent of the books were religious: Bibles and commentaries, sermons, writings of the Church Fathers.

Another 25 percent of the inventory were classic works from the ancient Greeks and Romans — Plato, Aristotle, Seneca, Cicero — along with medieval authors such as Dante. In other words, the Venetians were being nourished by the classical-Christian inheritance of the West.

And this is where Aldo Manuzio, better known by his Latin name, Manutius, enters the picture. When Manutius arrived in Venice, the classic texts of Greek literature, drama, philosophy, and history existed only in manuscript form in Europe. They might easily have been discarded as irrelevant to the problems facing ordinary Europeans. It was Manutius, trained as a humanist scholar, who first printed the complete works of Aristotle in Greek, along with the works of Aristophanes, Sophocles, Euripides, Herodotus, and Plato.

It is not too much to say that Manutius almost single-handedly jump-started the medieval interest in the works of classical antiquity, the literary lifeblood of the Renaissance.

Technological innovation is part of the story. Manutius pioneered the use of the smaller octavo-sized format for the works of antiquity. For the first time, beginning in 1501, he produced paperback “handy books” — editions of Virgil, Horace, Dante, Petrarch, and others — that were portable and affordable. Great literature, he believed, belonged to everyone and could be enjoyed anywhere. As humanist scholar Erasmus observed, Manutius was “building a library which knows no walls save those of the world itself.”

It’s vital to grasp what the burst of publishing and the recovery of classical texts represented: nothing less than the liberation of the medieval mind in a fresh pursuit of truth, wisdom, and beauty. It is no accident that this revolution began in the Venetian Republic, which had the oldest and most stable republican form of government in history. Never conquered by an external enemy, the Venetians cherished their independence, in publishing as well as in politics.

Yet it was not without controversy. As elsewhere in Europe, unregulated printing invited government censorship. The first literary censor, in fact, was a Venetian printer appointed by the state in 1516 to collaborate with the secret police of the city’s Council of Ten.

The censor’s role bore a striking resemblance to that of the present-day “digital commissioner” of the European Union, another unelected bureaucrat charged with suppressing speech considered offensive or dangerous. Before quitting his post, Thierry Breton had threatened to block transmission of Elon Musk’s interview with Donald Trump “to protect EU citizens from harm.” That’s pretty much the way the censors in the 16th century justified their coercive techniques of meting out fines, imprisonment, book burnings, etc.

The Venetian booksellers, however, were not going to be pushed around by either church or state. Protective of their financial interests, they kept the presses running. As Alessandro Magno points out, they mostly ignored the inquisitors. The sheer volume of Venetian printing in the early 16th century — half of all the books published in Europe were printed in Venice — confronted the inquisitors with an impossible task. As a result, Magno writes, “freedom of the press” would be “nearly absolute.”

Although moveable-type print was invented in China, its imperial government controlled the presses, just as the communist government in Beijing does today. Not so in Europe, especially in Venice, where publishing was a profit-making, entrepreneurial enterprise. “Anyone with money and some idea of which books would sell could purchase a printing press and set up shop,” writes Thomas Fadden in Venice: A New History. “For Europeans, therefore, printing became a craft. . . . Because it had the potential for great profits, printing expanded rapidly.”

More than any other society in their day, the Venetians, ever the entrepreneurs, placed a high value not only on books but also on the rights of those who wrote them. In 1486, Marco Antonio Sebellico was granted a copyright by the city, the first of its kind, for his book Decades Rerum Venetarum, a history of Venice. By 1545, with the book-publishing business at a fever pitch, the government declared that the individual writer possessed an “artistic personality” and was entitled to compensation.

In Inventing the World: Venice and the Transformation of Western Civilization, Meredith Small argues that the Venetian book publishers transformed the way we think about the life of the mind and the rights of the individual author. In Venice, uniquely, we find “the first evidence of intellectual property rights anywhere in the world.”

Venice thus boasts a long list of firsts in publishing. The city gave the world the first printed cookbook, the first book of fairy tales, the first book explaining how to make chocolate, and the first self-help book, On the Conduct of Honorable Men. In 1601, Lucrezia Marinella published The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, a riposte to a book critical of women and the first example of a woman arguing with a man in print. Indeed, Venice functioned almost like a year-round book fair. As Alessandro Magno notes, “There are accounts of how Renaissance bookshops, meeting places for intellectuals, reverberated with discussions and debates, at times resembling the halls of academe.”

There is a profound bond between the concept of self-government and an ethos of intellectual freedom. Thomas Jefferson, the father of the Library of Congress, summarized the relationship thus: “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.” The Venetians instinctively understood the linkage. The first book published in Venice, for example, was a work from Cicero, Rome’s greatest statesman: Cicero devoted his political career to defending Rome’s republican government against the forces of corruption and tyranny.

In similar fashion, Manutius emerged as a champion of republican freedom, and his humanism — rooted in a biblical outlook — was the reason. He believed that the recovery of the classics, alongside the teachings of Christianity, was the key to moral and cultural renewal. He published the devotional letters of Catherine of Siena, he explained, as a check against the immorality that offended a just God. “There is nothing left in man but the form and the name,” he wrote. “He no longer cares for honor or reputation.”

For nearly three centuries, the Republic of Venice sustained a vibrant printing industry, one that elevated eloquence, virtue, and the wisdom of the ancients. Its democratic form of government was buttressed by the cultural commitment to truth-seeking that this industry created.

Modern-day inquisitors, however, have betrayed this legacy. Contemptuous of the literary canon of the West, they have discarded the concept of moral excellence. Ignorant of the sources of our democratic freedoms, they follow the lead of the medieval book-burners: They would censor every point of view that refused to conform to their blinkered vision of human life and human societies.

Venice’s premier publisher would have stood them down. As one historian summarizes it, Manutius believed that books, and the intellectual freedom they demand, provided “an antidote to barbarous times.” Surely the barbarians are at the gates.

Manutius would be ready for them. “I do hope that if there should be people of such spirit that they are against the sharing of literature as a common good,” he wrote, “they may either burst of envy, become worn out in wretchedness, or hang themselves.” Hang the inquisitors — metaphorically speaking — and we just might save the republic.

—

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is a Presidential Scholar in Residence at New College of Florida and the C.S. Lewis Scholar for Public Life at Grove City College. He is the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War.

National Review: The West Is Abandoning Its Free-Speech Legacy

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Venice — Not long after the Gutenberg press was up and running, a publisher in Venice announced his life’s ambition: to make sure that people devoted to the pursuit of knowledge and truth could get their hands on affordable books. “Until this supply is secured,” he declared, “I shall not rest.”

Aldo Manuzio, who opened his print shop in 1494, kept true to his word. His publishing house, the Aldine Press, became so successful that he sparked a publishing revolution. By the 1500s, Venice was producing and selling more books than any other city in Europe. As a result, the Venetians helped to introduce into the West the concepts of free speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of conscience: the foundational rights of a healthy democratic society.

Yet today, 500 years later, many educated elites have turned their backs on this legacy of liberty. New forms of censorship, the shutting down of academic debate, the cancel culture: Modern attempts to suppress the free exchange of ideas make 16th-century Venice look like a citadel of classical liberalism.

Consider: During the 1500s, more than 690 Venetian printers and publishers generated at least 15,000 titles, which had an average press run of about 1,000 copies. Some historians estimate that the Venetian presses produced more than 35 million books. Printers worked 12 to 16 hours a day, printing one sheet every 20 seconds. Venetian women, such as Antonia Pulci, wrote and published books and worked as editors, illustrators, and proofreaders. In the universe of publishing, Venice was the North Star.

Situated in the middle of a tidal lagoon, Venice has always astounded visitors with its waterways, its architecture, its incomparable Piazza San Marco. Yet Alessandro Marzo Magno, author of Bound in Venice: The Serene Republic and the Dawn of the Book, describes medieval Venice thus: “What struck foreign visitors most were the books: the dozens and dozens of bookmaking workshops that were gathered here in a density unequaled anywhere else in Europe.” The Venetians effectively invented the modern bookstore.

What were they selling?

The discovery of a ledger in 1810, in the attic of the Basilica of San Marco, was revelatory: a comprehensive list of 12,934 book sales, from 1484 to 1487, from a single book shop in Venice. Educated Venetians were not, for the most part, consuming the thin gruel that dominates much of our publishing today. There were lots of books on mathematics, rhetoric, medicine, and natural history. About 20 percent of the books were religious: Bibles and commentaries, sermons, writings of the Church Fathers.

Another 25 percent of the inventory were classic works from the ancient Greeks and Romans — Plato, Aristotle, Seneca, Cicero — along with medieval authors such as Dante. In other words, the Venetians were being nourished by the classical-Christian inheritance of the West.

And this is where Aldo Manuzio, better known by his Latin name, Manutius, enters the picture. When Manutius arrived in Venice, the classic texts of Greek literature, drama, philosophy, and history existed only in manuscript form in Europe. They might easily have been discarded as irrelevant to the problems facing ordinary Europeans. It was Manutius, trained as a humanist scholar, who first printed the complete works of Aristotle in Greek, along with the works of Aristophanes, Sophocles, Euripides, Herodotus, and Plato.

It is not too much to say that Manutius almost single-handedly jump-started the medieval interest in the works of classical antiquity, the literary lifeblood of the Renaissance.

Technological innovation is part of the story. Manutius pioneered the use of the smaller octavo-sized format for the works of antiquity. For the first time, beginning in 1501, he produced paperback “handy books” — editions of Virgil, Horace, Dante, Petrarch, and others — that were portable and affordable. Great literature, he believed, belonged to everyone and could be enjoyed anywhere. As humanist scholar Erasmus observed, Manutius was “building a library which knows no walls save those of the world itself.”

It’s vital to grasp what the burst of publishing and the recovery of classical texts represented: nothing less than the liberation of the medieval mind in a fresh pursuit of truth, wisdom, and beauty. It is no accident that this revolution began in the Venetian Republic, which had the oldest and most stable republican form of government in history. Never conquered by an external enemy, the Venetians cherished their independence, in publishing as well as in politics.

Yet it was not without controversy. As elsewhere in Europe, unregulated printing invited government censorship. The first literary censor, in fact, was a Venetian printer appointed by the state in 1516 to collaborate with the secret police of the city’s Council of Ten.

The censor’s role bore a striking resemblance to that of the present-day “digital commissioner” of the European Union, another unelected bureaucrat charged with suppressing speech considered offensive or dangerous. Before quitting his post, Thierry Breton had threatened to block transmission of Elon Musk’s interview with Donald Trump “to protect EU citizens from harm.” That’s pretty much the way the censors in the 16th century justified their coercive techniques of meting out fines, imprisonment, book burnings, etc.

The Venetian booksellers, however, were not going to be pushed around by either church or state. Protective of their financial interests, they kept the presses running. As Alessandro Magno points out, they mostly ignored the inquisitors. The sheer volume of Venetian printing in the early 16th century — half of all the books published in Europe were printed in Venice — confronted the inquisitors with an impossible task. As a result, Magno writes, “freedom of the press” would be “nearly absolute.”

Although moveable-type print was invented in China, its imperial government controlled the presses, just as the communist government in Beijing does today. Not so in Europe, especially in Venice, where publishing was a profit-making, entrepreneurial enterprise. “Anyone with money and some idea of which books would sell could purchase a printing press and set up shop,” writes Thomas Fadden in Venice: A New History. “For Europeans, therefore, printing became a craft. . . . Because it had the potential for great profits, printing expanded rapidly.”

More than any other society in their day, the Venetians, ever the entrepreneurs, placed a high value not only on books but also on the rights of those who wrote them. In 1486, Marco Antonio Sebellico was granted a copyright by the city, the first of its kind, for his book Decades Rerum Venetarum, a history of Venice. By 1545, with the book-publishing business at a fever pitch, the government declared that the individual writer possessed an “artistic personality” and was entitled to compensation.

In Inventing the World: Venice and the Transformation of Western Civilization, Meredith Small argues that the Venetian book publishers transformed the way we think about the life of the mind and the rights of the individual author. In Venice, uniquely, we find “the first evidence of intellectual property rights anywhere in the world.”

Venice thus boasts a long list of firsts in publishing. The city gave the world the first printed cookbook, the first book of fairy tales, the first book explaining how to make chocolate, and the first self-help book, On the Conduct of Honorable Men. In 1601, Lucrezia Marinella published The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, a riposte to a book critical of women and the first example of a woman arguing with a man in print. Indeed, Venice functioned almost like a year-round book fair. As Alessandro Magno notes, “There are accounts of how Renaissance bookshops, meeting places for intellectuals, reverberated with discussions and debates, at times resembling the halls of academe.”

There is a profound bond between the concept of self-government and an ethos of intellectual freedom. Thomas Jefferson, the father of the Library of Congress, summarized the relationship thus: “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.” The Venetians instinctively understood the linkage. The first book published in Venice, for example, was a work from Cicero, Rome’s greatest statesman: Cicero devoted his political career to defending Rome’s republican government against the forces of corruption and tyranny.

In similar fashion, Manutius emerged as a champion of republican freedom, and his humanism — rooted in a biblical outlook — was the reason. He believed that the recovery of the classics, alongside the teachings of Christianity, was the key to moral and cultural renewal. He published the devotional letters of Catherine of Siena, he explained, as a check against the immorality that offended a just God. “There is nothing left in man but the form and the name,” he wrote. “He no longer cares for honor or reputation.”

For nearly three centuries, the Republic of Venice sustained a vibrant printing industry, one that elevated eloquence, virtue, and the wisdom of the ancients. Its democratic form of government was buttressed by the cultural commitment to truth-seeking that this industry created.

Modern-day inquisitors, however, have betrayed this legacy. Contemptuous of the literary canon of the West, they have discarded the concept of moral excellence. Ignorant of the sources of our democratic freedoms, they follow the lead of the medieval book-burners: They would censor every point of view that refused to conform to their blinkered vision of human life and human societies.

Venice’s premier publisher would have stood them down. As one historian summarizes it, Manutius believed that books, and the intellectual freedom they demand, provided “an antidote to barbarous times.” Surely the barbarians are at the gates.

Manutius would be ready for them. “I do hope that if there should be people of such spirit that they are against the sharing of literature as a common good,” he wrote, “they may either burst of envy, become worn out in wretchedness, or hang themselves.” Hang the inquisitors — metaphorically speaking — and we just might save the republic.

—

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is a Presidential Scholar in Residence at New College of Florida and the C.S. Lewis Scholar for Public Life at Grove City College. He is the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War.

July 10, 2024

A Founding Father’s Stirring Condemnation of Slavery

‘So much hath been said upon the subject of Slave-keeping, that an apology may be required for this paper,” wrote a Philadelphia physician two years before the start of the American Revolution. “The only one I shall offer is, that the evil still continues.”

What followed was one of the most devastating intellectual assaults on slavery ever published in the American colonies. The pamphlet titled “Address to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies upon Slavekeeping” struck a nerve: All 1,200 copies quickly sold out. Its author, Benjamin Rush, would soon join the revolutionary cause and sign the Declaration of Independence.

Like no other American Founder, Rush embodied the intellectual and moral alliance between liberal democracy and Protestant Christianity: He read John Locke alongside his Bible.

Appealing to conscience and common sense, Rush demolished the rationalizations for slavery then in vogue, beginning with the assumption that Africans were a naturally inferior race to white Europeans. He cited evidence of their “ingenuity” and “humanity” as proof that “they are equal to the Europeans.” He praised their virtue as impressive “as ever adorned a Roman or a Christian character.”

Next came the dubious claim that slavery was an approved practice in the Scriptures. “Christ commands us to look upon all mankind, even our enemies, as our neighbors and brethren,” Rush argued, “and ‘in all things, to do unto them whatever we would wish they should do unto us.’” Like the religious reformers of the previous century, Rush insisted that the Golden Rule — what he called “the law of equity” — should be applied to political life, regardless of race or creed.

Arguments for the economic necessity of slavery were taken to the woodshed. Economic prosperity did not depend upon the enslavement of other human beings. Quite the opposite: “Liberty and property form the basis of abundance, and good agriculture,” he wrote. “I never observed it to flourish where those rights of mankind were not firmly established.” Such was the divine will of “the great Author of our Nature, who has created man free.”

Although Rush’s name did not appear on the pamphlet, published in 1773, his writing revealed his scientific training. He soon began to acknowledge his authorship privately among his friends.

For a young physician still trying to establish himself in the Philadelphia social scene, it was a brazen act of defiance. A quarter of all the households in Philadelphia had slaves, and some of these slave-owners — including Benjamin Franklin and John Dickenson — were significant people in Rush’s professional life. “He became something of a celebrity in the abolitionist world,” writes biographer Stephen Fried, “and something of a pariah in the doctoring world.”

It didn’t matter. Rush called for an end to the slave trade and the gradual abolition of slavery in the colonies. Young slaves should be “educated in the principles of virtue and religion — let them be taught to read and write — and afterwards instructed in some business, whereby they may be able to maintain themselves,” he wrote. “Let laws be made to limit the time of their servitude, and to entitle them to all the privileges of free-born British subjects.”

The point must not be missed: Nearly a century before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, a leader of the American Revolution — an abolitionist — gave voice to the most radical vision of human equality on the world stage.

Rush became a protégé of Franklin, a confidant of John Adams, an editor of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, and George Washington’s surgeon general in the Continental Army. The slavery question would be put aside in the struggle for independence. But Rush’s prominence in the anti-slavery movement — he supported the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and helped raise funds for the independent black churches in Philadelphia — was not without effect.

Importantly, the Bible was Rush’s battering ram in the abolitionist cause. He was especially concerned with the social and psychological impact of the slave trade: The entire thrust of the moral code of Jesus of Nazareth, he argued, was at odds with the degrading effects of slavery.

“Every prohibition of covetousness — intemperance — pride — uncleanness — theft — and murder, which he delivered — every lesson of meekness, humility, forbearance, charity, self-denial, and brotherly-love which he taught, are levelled against this evil,” Rush wrote. “For slavery, while it includes all the former vices, necessarily excludes the practice of all the latter virtues, both from the master and the slave.”

Addressing the clergy directly, Rush delivered a jeremiad against ministers who provided religious rationales for their slave-owning congregants. Do not invoke the religion of Jesus, he warned, to “sanctify their crimes” against humanity. “In vain will you command your flocks to offer up the incense of faith and charity, while they continue to mingle the sweat and blood of Negro slaves with their sacrifices.”

In all of this, Rush’s legacy offers a rebuke to the progressive Left as well as the new Right. Modern liberalism, which treats religion as the enemy of human freedom, has effectively excised Christianity from America’s founding. The Left views the American story as a racist project from beginning to end. The new Right, however, regards the Founders’ emphasis on individual rights and freedom as the serpent in the garden, the wellspring of radical individualism and moral relativism.

It is a safe bet that Rush knew the Bible better than today’s cultural elites. He became the founder of the Sunday school movement in America and a leader of the American Bible Society. Rush’s letter “The Bible as a School Book,” addressed to a reverend in Boston, clearly reveals that Rush wanted the nation’s children to be immersed in the Scriptures as they learned to read. Even if the Bible said nothing about achieving eternal life with God, he wrote, it should be read in the schools because it contains “the greatest portion of that kind of knowledge which is calculated to produce private and public temporal happiness.”

As nearly all the Founders agreed, the Bible was America’s freedom book. Yet if liberty and equality were the birthright of every human soul, then slavery must be the enemy of the American Revolution. This, the doctor reasoned, was the moral logic of the 1776 project.

“The plant of liberty is of so tender a nature, that it cannot thrive long in the neighborhood of slavery,” he warned. “Remember the eyes of all Europe are fixed upon you, to preserve an asylum for freedom in this country, after the last pillars of it are fallen in every other quarter of the globe.”

—

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is a Presidential Scholar in Residence at New College of Florida and the C.S. Lewis Scholar for Public Life at Grove City College. He is the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War.

National Review: A Founding Father’s Stirring Condemnation of Slavery

This article was originally posted at National Review.

‘So much hath been said upon the subject of Slave-keeping, that an apology may be required for this paper,” wrote a Philadelphia physician two years before the start of the American Revolution. “The only one I shall offer is, that the evil still continues.”

What followed was one of the most devastating intellectual assaults on slavery ever published in the American colonies. The pamphlet titled “Address to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies upon Slavekeeping” struck a nerve: All 1,200 copies quickly sold out. Its author, Benjamin Rush, would soon join the revolutionary cause and sign the Declaration of Independence.

Like no other American Founder, Rush embodied the intellectual and moral alliance between liberal democracy and Protestant Christianity: He read John Locke alongside his Bible.

Appealing to conscience and common sense, Rush demolished the rationalizations for slavery then in vogue, beginning with the assumption that Africans were a naturally inferior race to white Europeans. He cited evidence of their “ingenuity” and “humanity” as proof that “they are equal to the Europeans.” He praised their virtue as impressive “as ever adorned a Roman or a Christian character.”

Next came the dubious claim that slavery was an approved practice in the Scriptures. “Christ commands us to look upon all mankind, even our enemies, as our neighbors and brethren,” Rush argued, “and ‘in all things, to do unto them whatever we would wish they should do unto us.’” Like the religious reformers of the previous century, Rush insisted that the Golden Rule — what he called “the law of equity” — should be applied to political life, regardless of race or creed.

Arguments for the economic necessity of slavery were taken to the woodshed. Economic prosperity did not depend upon the enslavement of other human beings. Quite the opposite: “Liberty and property form the basis of abundance, and good agriculture,” he wrote. “I never observed it to flourish where those rights of mankind were not firmly established.” Such was the divine will of “the great Author of our Nature, who has created man free.”

Although Rush’s name did not appear on the pamphlet, published in 1773, his writing revealed his scientific training. He soon began to acknowledge his authorship privately among his friends.

For a young physician still trying to establish himself in the Philadelphia social scene, it was a brazen act of defiance. A quarter of all the households in Philadelphia had slaves, and some of these slave-owners — including Benjamin Franklin and John Dickenson — were significant people in Rush’s professional life. “He became something of a celebrity in the abolitionist world,” writes biographer Stephen Fried, “and something of a pariah in the doctoring world.”

It didn’t matter. Rush called for an end to the slave trade and the gradual abolition of slavery in the colonies. Young slaves should be “educated in the principles of virtue and religion — let them be taught to read and write — and afterwards instructed in some business, whereby they may be able to maintain themselves,” he wrote. “Let laws be made to limit the time of their servitude, and to entitle them to all the privileges of free-born British subjects.”

The point must not be missed: Nearly a century before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, a leader of the American Revolution — an abolitionist — gave voice to the most radical vision of human equality on the world stage.

Rush became a protégé of Franklin, a confidant of John Adams, an editor of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, and George Washington’s surgeon general in the Continental Army. The slavery question would be put aside in the struggle for independence. But Rush’s prominence in the anti-slavery movement — he supported the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and helped raise funds for the independent black churches in Philadelphia — was not without effect.

Importantly, the Bible was Rush’s battering ram in the abolitionist cause. He was especially concerned with the social and psychological impact of the slave trade: The entire thrust of the moral code of Jesus of Nazareth, he argued, was at odds with the degrading effects of slavery.

“Every prohibition of covetousness — intemperance — pride — uncleanness — theft — and murder, which he delivered — every lesson of meekness, humility, forbearance, charity, self-denial, and brotherly-love which he taught, are levelled against this evil,” Rush wrote. “For slavery, while it includes all the former vices, necessarily excludes the practice of all the latter virtues, both from the master and the slave.”

Addressing the clergy directly, Rush delivered a jeremiad against ministers who provided religious rationales for their slave-owning congregants. Do not invoke the religion of Jesus, he warned, to “sanctify their crimes” against humanity. “In vain will you command your flocks to offer up the incense of faith and charity, while they continue to mingle the sweat and blood of Negro slaves with their sacrifices.”

In all of this, Rush’s legacy offers a rebuke to the progressive Left as well as the new Right. Modern liberalism, which treats religion as the enemy of human freedom, has effectively excised Christianity from America’s founding. The Left views the American story as a racist project from beginning to end. The new Right, however, regards the Founders’ emphasis on individual rights and freedom as the serpent in the garden, the wellspring of radical individualism and moral relativism.

It is a safe bet that Rush knew the Bible better than today’s cultural elites. He became the founder of the Sunday school movement in America and a leader of the American Bible Society. Rush’s letter “The Bible as a School Book,” addressed to a reverend in Boston, clearly reveals that Rush wanted the nation’s children to be immersed in the Scriptures as they learned to read. Even if the Bible said nothing about achieving eternal life with God, he wrote, it should be read in the schools because it contains “the greatest portion of that kind of knowledge which is calculated to produce private and public temporal happiness.”

As nearly all the Founders agreed, the Bible was America’s freedom book. Yet if liberty and equality were the birthright of every human soul, then slavery must be the enemy of the American Revolution. This, the doctor reasoned, was the moral logic of the 1776 project.

“The plant of liberty is of so tender a nature, that it cannot thrive long in the neighborhood of slavery,” he warned. “Remember the eyes of all Europe are fixed upon you, to preserve an asylum for freedom in this country, after the last pillars of it are fallen in every other quarter of the globe.”

—

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is a Presidential Scholar in Residence at New College of Florida and the C.S. Lewis Scholar for Public Life at Grove City College. He is the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War.

July 9, 2024

The American Spectator: A Frail President in a Hostile World

This article was originally posted at The American Spectator.

Before Biden There Was FDR

Joe Biden is not the first ailing American president to seek another term of office, despite being manifestly unfit for the job. But the last time it happened — with the re-election of Franklin Roosevelt for an unprecedented fourth term — the result was disastrous for the cause of democracy and human rights in the world.

Those in close contact with FDR during the 1944 presidential campaign knew that he was in a state of mental and physical decline. Senator Harry Truman, his newly picked running mate, was stunned by what he saw, “I had no idea he was in such a feeble condition,” he told an aide. On his way to Crimea for the Yalta Conference in February 1945 — the crucial wartime meeting between Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin — Roosevelt was, in the words of one physician, “a very sick man.”

Throughout much of the eight-day conference, the president physically projected weakness and capitulation. The end result of his performance was the forcible absorption of central and eastern Europe into the Soviet Union.

The conventional wisdom, touted for decades by Roosevelt’s sycophantic admirers, is that the Soviet army already occupied these European states by the time of the Yalta conference; there was nothing the president could do to alter Moscow’s intention to create “friendly states” along the border of the Soviet Union. “If he failed at Yalta, it wasn’t because of his physical or mental capacity,” insists author and New York Times editor Joseph Lelyveld. “Had he been at the peak of vigor, the results would have been much the same.”

Yet the transcripts of the Yalta conference and the memoirs of key participants expose this narrative as fairy dust. In fact, Roosevelt’s mental decline accentuated his naïve, progressive instincts and played into the hands of Stalin, the ruthless realist hellbent on dominating Europe.

It is true, of course, that the Red Army, in thwarting the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, occupied most of eastern Europe and was not about to leave. But the decisive issue at Yalta — the hinge upon which Soviet designs depended — was Poland. The American president possessed the power to intervene on behalf of its democratic future. Instead, FDR used Poland as a bargaining chip for his Wilsonian dream of a rejuvenated League of Nations.

Churchill went to Yalta with a supreme objective: to preserve Poland’s political independence. It was the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, in 1939, that ignited the Second World War and created an existential crisis for Great Britain. “Everyone here knows the result it was to us, unprepared as we were, and that it nearly cost us our life as a nation,” Churchill said. “Never could I be content with any solution that would not leave Poland as a free and independent state.”

In stark contrast with Churchill, FDR seemed indifferent to the sacrifice and valor of the 150,000 Polish ex-patriates who fought with the Allied forces at Monte Cassino, at the Battle of Britain, and in other theaters against the Nazis. His interventions on behalf of Poland were sophomoric, vacuous, and ineffective. Against the calculating and duplicitous Stalin, he adopted a posture of perpetual retreat.

The Polish democratic resistance, with its leadership in London, was dead set against the communist puppets installed in Warsaw during the fog of war. The American and British negotiating teams wanted the Soviets to agree to a new Provisional Government in Poland — reorganized “on a broader democratic basis” — to offset the Warsaw communists. After that, democratic elections would be held.

But the Soviets balked, and Roosevelt backed down. “The United States will never lend its support in any way to any provisional government in Poland which would be inimical to your interests,” he assured Stalin.

It was an absurd and astonishing thing to promise: The Soviet Union had made it clear that any democratic government on its border was “inimical” to its interests. Stalin confirmed this when, in September 1939, the Soviet army invaded Poland from the east as the Nazis invaded from the west. He confirmed it again when he proceeded to brutally dismember Polish society, ordering the deportation and execution of tens of thousands of ordinary citizens.

If elections were to be held without a more broadly democratic government in place, Roosevelt and Churchill insisted upon the presence of election observers. Churchill took the lead: “The U. S., Britain, and Russia should be observers to see that they are carried out impartially. These are no idle requests.”

Yet the prime minister lacked the one thing he desperately needed: the clear and unconditional support of the American president. It never arrived. Eager for a Polish settlement to secure domestic support for his dream of a United Nations, FDR instructed his aides to delete the “offending” provision for election observers. Soviet membership in the United Nations, Roosevelt believed, would moderate Stalin’s illiberal instincts.

British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, at Churchill’s side at Yalta, summarized FDR’s frame of mind thus: “He was deluding himself.” Hugh Lunghi, a translator and member of the British delegation at Yalta, was astonished by FDR’s naivete. “Those of us who worked and lived in Moscow knew that there was not a chance in hell that Stalin would allow free elections in those countries when he didn’t allow them in the Soviet Union.”

In February 1945, the American president was commander in chief of the most powerful military in the world and was within months of possessing an atomic weapon. At the beaches of Normandy, U.S. and Allied forces had staged the largest and most successful amphibious invasion in the history of warfare, ensuring the defeat of Nazi Germany. The United States boasted unrivaled industrial might and was the engine of the global economy. Yet with all of these resources in hand, Roosevelt would not even insist upon election observers in a European state that had been brutalized by both the Nazis and the Russians.

Was the President’s Health Determinative?

Did Roosevelt’s fragile condition contribute to his posture of appeasement? Of course it did.

In Malta, on his way to Yalta, Churchill’s physician, Lord Moran, interacted with Roosevelt and recorded in his diary: “The president appears to be a very sick man. He has all the symptoms of hardening of the arteries of the brain, in an advanced stage … I give him only a few months to live.” (Roosevelt died two months later). When he arrived at Yalta, recalled Lunghi, “the President, waxen cheeked, looked ghastly.” His condition deteriorated throughout the conference. Those present believed Roosevelt probably heard only half of what was said during the meetings.

In his memoirs of the Second World War, Churchill complained that Roosevelt took “a distant view” of the Polish question. “It seemed to me, throughout the sessions of that conference, that the President had a distant view on many other problems as well,” recalled A.H. Birse, Churchill’s chief interpreter at Yalta. His aides, Birse added, “appeared to be putting the words into his mouth for him to say.” Indeed, based on the notes of his physician, Howard Breunn, it seems likely that Roosevelt suffered a pulsus alternans (when every second heartbeat is weaker than the preceding one) during one of the debates over Poland.

Thus, a frail American president embodied political impotence at a moment of geo-political crisis. By not demanding a free and fair democratic election in Poland, Roosevelt telegraphed a clear message to Stalin: The United States would not object if Poland’s sovereignty and independence were destroyed, nor that of Eastern Europe’s. The message was received in the Kremlin, loud and clear.

Nevertheless, with a compliant press corps, Roosevelt later declared to Congress that the Yalta conference had been a smashing success, especially with regards to Poland. There were difficulties, he admitted, “but at the end, on every point, unanimous agreement was reached. And more important even than the agreement of words, I may say we achieved a unity of thought and a way of getting along together.”

It was a deception based upon a delusion underwritten by political ambition and personal vanity.

What difference might a democratic Poland have made, caught in the communist grip of the Soviet bloc? That question was answered in 1989, when the Polish democratic resistance movement, known as Solidarity, compelled the regime to allow free and fair elections. Solidarity candidates won in a landslide. The downfall of communism in Poland led directly to the collapse of communism in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

The democratic revolutions of 1989 might have occurred much earlier had a stronger American leader been present at Yalta. Joseph Stalin displayed a ruthlessness, a disregard for moral norms, and a lust for domination that has few historical rivals. The sick and feeble Roosevelt was no match for “the man of steel.”

If history is any guide, America’s enemies are taking stock of the fragile president who melted into incoherence during his first debate with Donald Trump — and they are praying that he stays in the race and wins in November.

—

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is a Presidential Scholar in Residence at New College of Florida and the C.S. Lewis Scholar for Public Life at Grove City College. He is the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War.

May 8, 2024

National Review: A Christian Prophet’s Unheeded Warning to the Academy

This article was originally posted at National Review.

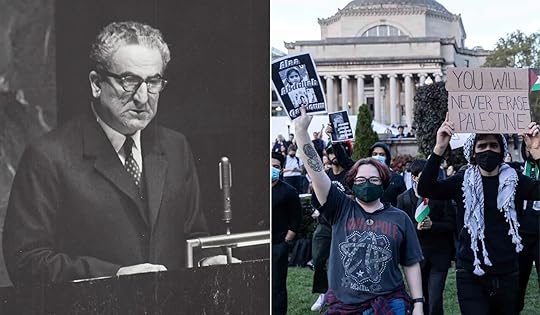

The intellectual and moral chaos that is ravaging American higher education — typified by the campus protests and outbursts of antisemitism — is serving as a wake-up call to religious conservatives. In fact, the wake-up call was first delivered more than 40 years ago by a leading Christian public intellectual.

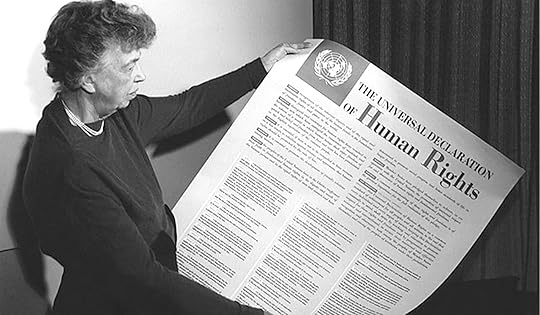

“No civilization can endure with its mind being as confused and disordered as ours is today,” declared Charles Malik, the first Lebanese ambassador to the United States and an architect of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to a gathering of Evangelical leaders in September 1980. “At the heart of the crisis in Western civilization lies the state of the mind and the spirit in the universities.”

Speaking at the dedication ceremony for the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College, Malik described a “total divorce” in the secular academy between the life of the mind and the truths of biblical religion. The elite academic institutions in the United States and Europe, he said, were awash in materialism, atheism, nihilism, and the will to power. As a result, “all the preaching in the world, and all the loving care of even the best parents . . . will amount to little, if not to nothing” if the universities remain indifferent or hostile to faith. “The enormity of what is happening is beyond words.”

A scholar, educator, and diplomat, Malik understood the intellectual currents of 20th century. He went to Germany in the late 1930s to study philosophy with Martin Heidegger, but the political climate forced him to change plans and complete his Ph.D. in philosophy at Harvard. Returning to Lebanon, he established the Department of Philosophy at the University of Beirut. He was soon tapped by the Lebanese president to represent his country at the founding conference of the United Nations in 1945. His political career — including a stint as president of the U.N. Security Council — deepened his awareness of the ideological forces enveloping the academy.

The decline of the humanities, Malik observed, was at the center of the problem. The humanities —the disciplines of philosophy, politics, history, literature, the arts, and theology — explore the most important questions about the meaning and purpose of our mortal lives. As the humanities go, he said, so goes the university. “It is there,” he said, “that the foundations of character and mind and outlook and conviction and attitude and spirit are laid.”

Malik issued a summons to the Christian community: Christians of all denominations should produce, within a decade, an exhaustive study of what was occurring in the field of humanities in the great universities of Europe and America. Malik challenged his Evangelical audience to assemble the finest minds — including scientists, philosophers, poets, and preachers — to explore how the humanities could be renewed by the reintroduction of ancient wisdom and “right reason.” The task was never taken up by the Christian leadership of any denomination.

Next came a warning. Malik embraced the Evangelical emphasis on Scripture, salvation by grace, and heartfelt faith. “I speak to you as a Christian,” he said. “Jesus Christ is my Lord and God and Savior and Song day and night.” Yet he rejected a form of piety that neglected the life of the mind. “I must be frank with you,” he confessed. “The greatest danger besetting American Evangelical Christianity is the danger of anti-intellectualism.”

It was a sobering thing to announce at Wheaton College, then considered the Harvard of the Evangelical academy. Nevertheless, anti-intellectualism was “an absolutely self-defeating attitude” that led to one result: the abdication of the arenas of cultural influence to the adversaries of biblical religion. “For the sake of greater effectiveness in witnessing to Jesus Christ himself, as well as for their own sakes, Evangelicals cannot afford to keep on living on the periphery of responsible intellectual existence.”

Malik could hardly have anticipated that this problem would be aggravated by political activism. In 1979, a year before his address, the “Christian Right” had burst upon the American political landscape with the creation of the Moral Majority. Since then, Evangelicals have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in national political campaigns but barely a fraction of that amount supporting Christian scholars or building new academic centers to counter the reigning orthodoxies. With the recent closure of The King’s College, for example — where I taught Western civilization for a decade — there is not a single Christian institution of higher learning in New York City.

With remarkable prescience, Malik warned that the outcome of this crisis concerned Jews as much as Christians. Ideologies that cannot abide the claims of revealed religion undermine the foundations of Western civilization. “If the highest Christian values be overturned,” he said, “so will the highest Jewish values.” Militant secularism and antisemitism march in lockstep: It is thus unsurprising that Jews no longer feel safe on many of America’s elite campuses.

There is a profound sense of urgency to Malik’s message, flowing from a life devoted to working for a more just and humane social order, built on Christian ideals. Malik was burdened by the reality that the most prestigious universities in the world, captured by bankrupt philosophies, could not address the deepest ills afflicting the soul of the West: hedonism, cynicism, breakdown of the family, corruption of character, and “the dearth of grace and beauty.”

He implored his fellow believers to step into the breach. “If Christians do not care for the intellectual health of their own children and for the fate of their own civilization, a health and a fate so inextricably bound up with the state of the mind and spirit in the universities, who is going to care?”

The cognitive and spiritual turmoil of the academy suggests that Malik’s challenge remains unanswered.

—

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is a Presidential Scholar in Residence at New College of Florida and the C.S. Lewis Scholar for Public Life at Grove City College. He is the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War.

April 10, 2024

National Affairs: Locke, Virtue, and a Liberal Education

This article was originally posted at National Affairs.

Following the Boston Massacre in March 1770, the Massachusetts lawyer and patriot Josiah Quincy, Jr., joined John Adams in defending the British soldiers involved. The sentries had fired into an unruly crowd of civilians, killing three and wounding eight. If convicted, they would hang. In his argument for the defense, Quincy cited three main sources: the Bible, English common law, and the English philosopher whose theories on government would fuel the American Revolution.

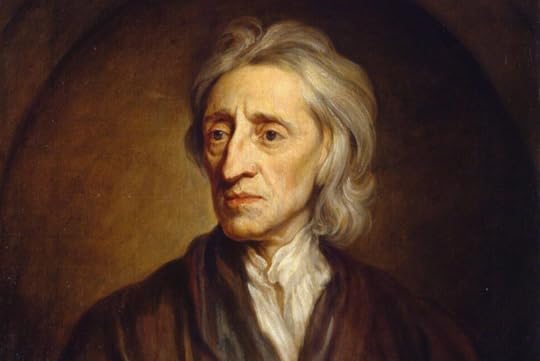

The writings of this philosopher, Quincy argued, represented “the wisdom and policy of ages,” coming from a man “who [had] done as much for learning, liberty, and mankind, as any of the Sons of Adam; I mean the sagacious Mr. Locke.” After quoting from John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, Quincy concluded his tribute thus: “We cite this author to show the world, that the greatest friends to their country, to universal liberty, and the immutable rights of all men, have held tenets, and advanced maxims favourable to the prisoners at the bar.”

The jury found the British soldiers not guilty. At a key moment in America’s struggle for independence, against an enraged mob of public opinion, the principle of impartial justice was reaffirmed.

For Quincy, and for other colonial Americans, Locke was more than a political philosopher: He was a man renowned for his “humanity,” writes Claire Rydell Arcenas in America’s Philosopher: John Locke in American Intellectual Life. He was “a companion in thought and an exemplar.” And unlike any other 17th-century author, Locke was for many Americans “an immediate, daily authority” over the conduct of their public and civic lives.

For a growing cohort of conservatives in our own time, however, Locke’s influence on the American founding explains the wretched condition of our national culture. The decline of religion, the breakdown of the family, the idolization of the free market, the soul-destroying materialism, expressive individualism, and widespread moral rot: All of these ills are laid at Locke’s doorstep, tied to his conceptions of equality, freedom, and natural rights.

According to critics like philosopher Yoram Hazony, Notre Dame’s Patrick Deneen, and First Things editor R. R. Reno, the chief aim of Lockean liberalism is to liberate individuals “from the constraints imposed by the natural world.” The last half-century of scholarship on Locke has convincingly refuted this portrait. Yet there is a much deeper problem than intellectual laziness among Locke’s conservative critics: Not unlike the progressive left, they fail to grasp how the preservation of republican government depends on the inculcation of republican virtues.

LOCKE’S INFLUENCE

In reality, Locke regarded the cultivation of republican virtue as the central task of the educator. Character formation — rooted in the classical Christian tradition — is the subject of Some Thoughts Concerning Education, the collection of letters Locke wrote to his close friend Edward Clarke. According to the late Cambridge historian Peter Laslett, Locke’s practical and innovative approach ranks as “one of the most influential” in the history of education. It is largely forgotten today that Locke not only made the definitive case for government by consent; he also promoted, with genuine insight into human nature, an educational philosophy that would produce the kinds of citizens fit for self-government.

Locke composed his correspondence with Clarke during his political exile in the 1680s, when the question of representative government was the subject of intense international debate. Political absolutism was on the rise in Great Britain (under Charles II and James II) and France (under Louis XIV). Meanwhile, religious despotism, practiced by the Protestants in the Church of England and the Catholics in France, threatened Europe’s social fabric. Implicated in a failed plot to assassinate the English monarch, Locke fled to the Netherlands, where he reflected on several major themes: the nature of human understanding, the necessity of religious freedom, and the role of education in creating a more liberal society. Locke’s educational advice reflects the turmoil of his age:

By what fate vice has so thriven amongst us these few years past, and by what hands it has been nursed up into so uncontrolled a dominion, I shall leave to others to inquire. I wish that those who complain of the great decay of Christian piety and virtue everywhere, and of learning and acquired improvements in the gentry of this generation, would consider how to retrieve them in the next. This I am sure, that, if the foundation of it be not laid in the education and principling of the youth, all other endeavours will be in vain.

This is precisely what Locke set out to explain in his letters: how to transmit traditional piety and moral character to the next generation. “[N]othing that may form children’s minds is to be overlooked and neglected,” he declared, and “whatsoever introduces habits, and settles customs in them, deserves the care and attention of their governors.”

Locke touched a nerve. Probably no thinker had a greater impact on the educational philosophy of the Anglo-American world in the century after his death. In Sermons on the Religious Education of Children, for example, Congregationalist minister Philip Doddridge cited Locke alongside King Solomon. Historian Samuel Pickering, Jr., observed that Locke’s writings on education “were practically biblical” in their importance to the emerging middle class. “By the 1730s,” he pointed out, “Locke’s educational ideas had been absorbed into the thought of the century.”

What ideas animate Locke’s educational handbook? More than any of his other works, Some Thoughts Concerning Education demolishes the crude caricature of Locke as a secular hedonist made vogue by political philosopher Leo Strauss in the 1950s and parroted more recently by numerous voices on the new right.

Instead of Locke the economic materialist, we find a man admonishing parents to curb their child’s desire for material goods at every turn. Instead of Locke the Enlightenment utopian, we meet a student of the Bible with a sober view of the doctrine of the Fall. Instead of Locke the radical individualist, we see a patriot trying to nourish a culture of responsible citizenship. And instead of Locke the moral agnostic, we encounter a religious believer who defined true virtue as “the knowledge of a man’s duty, and the satisfaction it is to obey his Maker, in following the dictates of that light God has given him, with the hopes of acceptation and reward.” In short, we find in Locke’s philosophy of education a deep and abiding concern for virtue.

EDUCATING FUTURE LEADERS

It may seem odd that a middle-aged bachelor would offer child-rearing advice. Locke himself confessed, “I am too sensible of my want of experience in this affair.” But Edward Clarke, married with two young children, sought him out. Locke had served as a tutor to young students at Oxford; was given charge over the grandson of his political mentor, Lord Shaftesbury; and had gained a reputation for engaging the minds of children on serious topics. “It is quite clear,” writes biographer Roger Woolhouse, “that he was a keen and reflective observer of the young.”

There is a sense of urgency in Locke’s correspondence, a conviction that what a child learns during his earliest years creates “habits woven into the very principles of his nature.” The willful neglect of this truism probably accounts for most of the social problems ravaging America and the West today.

Locke’s advice was intended for the sons of English gentlemen, who were expected to set an example of civility and integrity in their public and private lives, so the stakes were high. Elsewhere in his writings, he explained that a gentleman should devote special attention to “moral and political knowledge” on those studies “which treat of virtue and vices, of civil society and the arts of government, and will take in also law and history.” English gentlemen were expected to engage in public affairs, and Locke hoped to influence the quality of their leadership.

Nevertheless, Locke did not aim his counsel exclusively at one particular class; the moral code he recommended befitted “a gentleman or a lover of truth.” Neither did Locke believe that gender made a significant difference in education. Writing to Mrs. Clarke in January 1684, he said that nothing in his previous letter about the education of her son required alteration with respect to her daughter; he saw “no difference of sex in your mind relating…to truth, virtue and obedience.” The exchange affords a glimpse of what I call Locke’s “democratic conscience” — his belief in the universal human capacity to apprehend moral and spiritual truths. This conviction anchored the views of human equality and independence that he expressed in his political writings.

CURBING THE APPETITES

Locke’s modern critics allege that he viewed man in purely economic terms — that behind his enthusiasm for private property lurked a craven materialism, a blank check for instant gratification. The decidedly anti-materialist message of Some Thoughts plainly undermines that claim.

An overriding theme of Locke’s letters is that children must learn to restrain their desires — not just for frivolous or sensual things, but even for innocent pleasures. If a child asks to be given certain clothes or other “trifles” that he doesn’t need, for example, the mere asking should ensure that he does not get them. “The best for children is, that they should not place any pleasure in such things at all, nor regulate their delight by their fancies, but be indifferent to all that nature has made so.” Locke acknowledged that “tender parents” may find this approach too severe. Nevertheless, he insisted it is necessary if children are to grow into respectable adulthood:

By this means they will be brought to learn the art of stifling their desires, as soon as they rise up in them, when they are easiest to be subdued. For giving vent, gives life and strength to our appetites; and he that has the confidence to turn his wishes into demands, will be but a little way from thinking he ought to obtain them….The constant loss of what they craved or carved to themselves should teach them modesty, submission, and a power to forbear.

The same Spartan attitude, he believed, should be applied to children’s physical training. Parents should not shield their children from all physical discomforts, because hunger, thirst, lack of sleep, and weariness from work “are what all men feel.” These inconveniences can serve a good purpose: They are signposts on the road to character. “The pains that come from the necessities of nature,” he argued, “are monitors to us to beware of greater mischiefs….But yet, the more children can be inured to hardships of this kind, by a wise care to make them stronger in body and mind, the better it will be for them.”

So much for Locke as the Epicurean playboy.

THE LOVE OF LEARNING

Although parents and tutors must take pains to curb the desire to have, they should never quash the desire to know. “Curiosity,” Locke advised, “should be as carefully cherished in children, as other appetites [are] suppressed.” He rejected “the ordinary method of education,” which involved “the charging of children’s memories, upon all occasions, with rules and precepts,” all quickly forgotten. In The Educational Writings of John Locke, John William Adamson explains that in Locke’s view, attempts to compel students to learn would fail. Another form of motivation was necessary.

Locke wanted children’s education to be engaging and enjoyable, both intellectually and emotionally. “None of the things they are to learn should ever be made a burden to them or imposed on them as a task,” he contended. “Whatever is so proposed presently becomes irksome.” Locke also rejected the “rough discipline of the rod,” instead recommending that parents direct their child’s interests, likes, energy, and creativity graciously.

How might parents and educators captivate children in this way? Locke saw a strong connection between the love of learning and the love of freedom that engages children in their play. In this he echoed Montaigne, who observed that “children’s games are not games; we ought to regard them as their most serious occupations.” Locke encouraged any recreation that does not endanger the child’s health, deeming such play “as necessary as labor or food.” Recreation, he believed, will help create deep bonds between children and their educators, who will be free to talk with their charges “about what most delights them.” The impact on children will be transformative:

[T]hey may perceive that they are beloved and cherished and that those under whose tuition they are, are not enemies to their satisfaction. Such a management will make them in love with the hand that directs them, and the virtue they are directed to.

To achieve all this, Locke acknowledged, requires “patience and skill, gentleness and attention.” This is one reason Locke rejected state education and urged parents to teach their children at home, with the help of carefully chosen tutors. The moral formation of their children during this crucial season of their lives was the most important task of both mothers and fathers; it could not be left to chance. With this in mind, Locke urged fathers to make their sons their friends “as fast as their age, discretion, and good behaviour could allow it.”

So much for Locke as the enemy of the traditional family.

PROPERTY AND THE WILL TO POWER

Many interpreters of Locke have assumed (wrongly) that his conception of the “state of nature” was lifted from Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan. For Hobbes, the state of nature acknowledges no fundamental moral law, leaving human beings at each other’s throats, desperate for an all-powerful Sovereign to preserve their individual lives. But in Locke’s state of nature, there exists a known and enforceable moral law, which obliges everyone not only to preserve his own life, but also the life of his neighbor:

Children should from the beginning be bred up in an abhorrence of killing or tormenting any living creature, and be taught not to spoil or destroy any thing….And truly, if the preservation of all mankind, as much as in him lies, were every one’s persuasion, as indeed it is every one’s duty, and the true principle to regulate our religion, politics, and morality by, the world would be much quieter, and better natured than it is.

Unlike Hobbes, Locke sought to “instill sentiments of humanity” at the earliest possible age. This is essential, he wrote, because human nature inclines us in the opposite direction: “I told you before that children love liberty….I now tell you they love something more; and that is dominion: and this is the first original of most vicious habits, that are ordinary and natural.” Locke’s anthropology here deserves attention: For him, the lust to dominate is “ordinary and natural” for all human beings. Scholars debate Locke’s religious beliefs about the effects of the Fall, but the glib association of Locke’s views with those of the Enlightenment philosophes — who assumed mankind’s essential goodness — cannot be credibly maintained.

Locke argued that the “love of power and dominion shows itself very early” among the young, “almost as they are born.” This impulse appears in a child’s desire to possess things — whatever he wants and whenever he wants it. “[T]hey would have property and possession, pleasing themselves with the power which that seems to give, and the right they thereby have to dispose of them as they please.” Locke identified this disposition as the source of “almost all the injustice and contention that so disturb human life.” It is to be rooted out, he wrote, at almost any cost.

Is this the same Locke famous for his defense of private property? To be sure, the concept of private property is indispensable to Locke’s triad of natural rights: As the fruit of human labor, the possession of property is an inalienable right and deserves the same vigorous protections as life and liberty. Indeed, in 17th-century Europe, with its political and religious authoritarianism, the seizure of property was the favored technique to produce compliant citizens. It needed special protection.

Nevertheless, the acquisition of property, absent a strong moral culture, endangers a child’s soul. “As to the having and possessing of things,” Locke observed, “teach them to part with what they have, easily and freely to their friends.” Parents and tutors must determinedly combat avarice in children and replace it with generosity: