Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 4

January 31, 2023

National Review: A Decades-Old Warning for Evangelical Christians Is More Relevant Than Ever

This article was originally posted at National Review.

In the years after the Second World War, an American theologian delivered a dire forecast about the future of Protestant Christianity. Unless the Evangelical church in America grappled with the great social questions of its time, warned Carl F. H. Henry, it “will be reduced either to a tolerated cult status” or become “a despised and oppressed sect” within two generations. That was in 1947.

Henry’s book, The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism, published 75 years ago, challenged the Evangelical church to tackle problems such as racism, materialism, economic injustice, and international aggression. Although himself a thoroughgoing Evangelical, Henry had worked as a reporter for the New York Times and got his Ph.D. in philosophy from Boston University. He was attuned to the issues that were shaping America’s future — and that demanded, in his view, a Christian response. “There is no room here for a gospel that is indifferent to the needs of the total man nor of the global man.”

For Henry, the post-war years brought those needs into focus. The 1940s saw the start of the civil-rights movement, as African Americans returned home from war to confront racial segregation; massive labor strikes, including a rail strike that triggered the intervention of federal troops; the formation of the United Nations to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”; and, at the international trials at Nuremberg, the startling revelations of Nazi atrocities.

Yet, as Henry observed, American fundamentalism had adopted habits of thought that isolated the Christian message from the central debates of the modern world. The broader Evangelical movement, he warned, was in danger of making the same mistake. He recalled a meeting with more than 100 Evangelical pastors and asking how many of them, in the previous six months, had preached a sermon addressing problems such as “aggressive warfare,” “racial hatred and intolerance,” or “exploitation of labor.” The result: “Not a single hand was raised in response.”

The church of the apostolic age, Henry explained, transformed the culture of pagan Rome because it offered a compelling and aspirational vision of human life. By contrast, he said, modern fundamentalism had reduced the gospel message to one of condemnation: “Whereas once the redemptive gospel was a world-changing message, now it has narrowed to a world-resisting message.”

The rise of the “social gospel” — the attempt by liberal Protestantism to address social ills while downplaying the biblical doctrines of individual sin and redemption — led to a backlash:

Fundamentalism, in revolting against the Social Gospel, seemed also to revolt against the Christian social imperative. It was the failure of Fundamentalism to work out a positive message within its own framework, and its tendency instead to take further refuge in a despairing view of world history, that cut off the pertinence of evangelicalism to the modern global crisis.

A plea to change course, The Uneasy Conscience was deeply controversial. Henry’s diagnosis of Evangelical retreat could be severe. His warning about capitalism without moral constraints seemed at odds with America’s economic dominance. To an audience hostile to Catholicism, he praised the Catholic Church for taking seriously the task of statesmanship. “The Roman Catholic Church has trained its candidates for world diplomatic posts with singular vision; in today’s world the ministry of world affairs is no less important than any other.”

Nevertheless, no one could accuse Henry of going soft on Christian orthodoxy. Man’s fundamental predicament was his “revolt against God,” and thus the “supreme aim” of the church was “the proclamation of redeeming grace to sinful humanity.” Henry reinforced these themes in his magnum opus, God, Revelation, and Authority. In the latter half of the 20th century, probably no individual worked harder to rescue Evangelicalism from the anti-intellectualism and self-imposed exile of fundamentalist Christianity.

Three quarters of a century after the publication of The Uneasy Conscience, what might Henry say about the Evangelical church in America?

That question was the subject of a recent conference co-sponsored by the Institute on Religion and Democracy and Pepperdine University’s School of Public Policy. It brought together scholars, pastors, historians, college presidents, and others to reflect on Henry’s legacy. To some of the participants, widespread negative perceptions of Evangelicalism confirmed Henry’s prophetic voice.

Yet there was broad agreement that Evangelicals are among the most crucial actors in civil society: notably, in charitable efforts to help people in need, regardless of their background or beliefs. Motivated by their love and obedience to Jesus, Evangelicals occupy what Anne Snyder, editor of Comment, called a “sacred sector.” Evangelical organizations, in fact, often lead the way in providing disaster relief, drug treatment, prisoner reentry programs, and education and mentoring for at-risk kids.

Henry brought his expansive vision into every institution in which he served, including Christianity Today, World Vision, and Prison Fellowship. “The cries of suffering humanity today are many,” he wrote. “No evangelicalism which ignores the totality of man’s condition dares respond in the name of Christianity.” Put another way: When the representatives of the gospel fail to speak to the whole person, their message goes unheard.

If the Evangelical conscience appears uneasy, Carl Henry’s challenge might just be the tonic it requires.

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

January 16, 2023

National Review: The Gospel According to Locke

This article was originally posted at National Review.

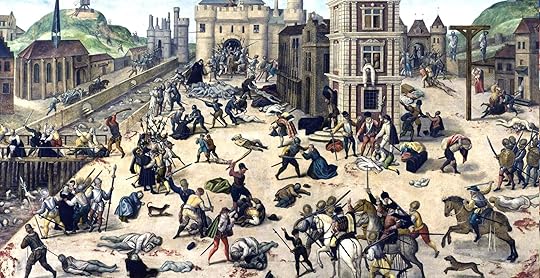

Conspiracy theories, nativism, militant religion, mob violence, a plot to topple the government — welcome to 17th-century England. English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) lived through one of the most turbulent and divisive periods in British history. At the center of the storm, he believed, was a degraded form of Christianity. “All those flames that have made such havoc and desolation in Europe, and have not been quenched but with the blood of so many millions,” he wrote, “have been at first kindled with coals from the altar.”

Locke’s response was to offer the world a new political vision: a liberal society based on a radical reinterpretation of the teachings of Jesus. The bracing message, contained in his Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration, was about the liberty and dignity of every human soul. It would form the bedrock of the American political order.

For Locke, the first order of business was to insist that every human being bore the imprint of an intelligent, personal, and purposeful Creator. No one must be treated as a means to an end, as someone else’s property. Rather, every individual belonged to God, and was designed for a noble and transcendent purpose. As Locke declared in his Second Treatise: “For men being all the workmanship of one omnipotent, and infinitely wise Maker; all the servants of one Sovereign Maker, sent into the world by his order and about his business, they are his property, whose workmanship they are, made to last during his, not one another’s pleasure.”

Most of Locke’s audience, literate in the Bible, would have recognized his allusion to a passage from Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians: “For we are God’s workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them” (Eph. 2:10).

The political and religious leaders of Locke’s day invoked the “divine right” of kings to justify political absolutism. In contrast, Locke argued that only a government based on the consent of the governed could honor the divine prerogative. Here, in brief, is his religious argument for the right to revolution: If the political authority tries to oppress God’s servants — by threatening their life, liberty, or property — it becomes morally illegitimate.

In the century before Locke’s birth, the Protestant Reformation had opened the doors to religious pluralism throughout Europe. For his political theory to work in societies with competing religious traditions, another sea change in thinking was required. The state must stop punishing people for refusing to endorse the preferred national religion. Likewise, church leaders must stop trying to manipulate the levers of power to impose their sectarian values on an unwilling population. “No peace and security, no, not so much as common friendship, can ever be established or preserved amongst men,” Locke wrote in A Letter Concerning Toleration, “so long as this opinion prevails . . . that religion is to be propagated by force of arms.”

In the wake of the wars of religion, it was assumed that the best guarantee of civic peace and social cohesion was the rigid imposition of a national creed — Catholicism in France, Calvinism in Geneva, Anglicanism in England, and so on. Yet laws criminalizing dissent created a permanent underclass across Europe. Locke watched in anguish as religious dissenters were persecuted, jailed, executed, or sent into exile.

Locke decided to turn conventional thinking on its head. The key to political stability was not conformity through coercion. Rather, a government that protected — with equal justice — the rights and freedoms of people of all faith traditions would enjoy widespread support. Presbyterians, Anabaptists, Catholics, Quakers, Jews, even Muslims — no one, according to Locke, should be denied his essential civil rights because of religion. “The sum of all we drive at is that every man enjoy the same rights that are granted to others.” (Locke is routinely accused of having denied toleration to Catholics, but a close and contextual reading of his Letter strongly suggests otherwise.) Here is a revolutionary application of the Golden Rule, one of the pillars of Christian morality.

The American Founders, supported by the nation’s clergy, thoroughly absorbed Locke’s political principles — from the separation of powers to the separation of church and state. Nevertheless, many on today’s religious right reject Lockean liberalism for supposedly opening the door to relativism and “radical individualism.” Progressives, on the other hand, applaud his commitment to individual rights but rip it from its religious foundation.

In fact, Locke’s political outlook was saturated with Christian assumptions about justice, equality, freedom, and natural rights. Like no thinker before him, Locke combined Whig political theory with a gospel of divine grace and mercy.

A lifelong student of the Bible, he searched the scriptures for examples of God’s indiscriminate love. He founded a philosophical society that required prospective members to affirm their love for “all men, of what profession or religion soever.” For many years he kept notes from a sermon based on Galatians 5:6, “the only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love” — a theme that appears throughout his writings and personal letters.

The life and teachings of Jesus were his lodestar. Jesus never bullied people into becoming his followers, never used force, and scolded his disciples when they were inclined to do so. Christ came into the world, Locke believed, to bring life and peace to those who had become God’s enemies. To Locke, Jesus was “our Savior,” “our Lord and King,” “the Captain of our Salvation,” and “the Prince of Peace.”

Thus, the moral economy of the Christian story must inform the ideals of a political society: The gospel offered a path by which people could live together with their deepest differences. “The toleration of those that differ from others in matters of religion, is so agreeable to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and the genuine reason of mankind,” Locke wrote, “that it seems monstrous for men to be so blind, as not to perceive the necessity and advantage of it in so clear a light.”

If the gospel according to Locke was an ingredient in the soil from which liberal democracy grew, then America, lacerated by new hatreds and divisions, could use a little more of that old-time religion.

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

November 2, 2022

National Review: The Totalitarian Temptation Remains

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Naples, Italy — In the days leading up to the Allied occupation of Naples during the Second World War, many residents fled to underground shelters and catacombs to escape the bombing raids that pounded the city. What some of them left behind amounts to a grim warning about the power of a utopian ideology to deceive and denigrate the human mind.

In the shelter I visited recently — a labyrinth of frightfully narrow passages and tiny caves at least 100 feet underground — our tour guide pointed out a drawing scratched onto one of the walls. It was a crude portrait of the fascist leaders who had plunged the world into war: Hirohito, Hitler, and Mussolini. Under the drawing was the word “Vincerò!” — I will win! Not even with the collapse of the Axis powers in sight, living like a rat in a sewer system, would the underground artist lose faith in his political religion.

A hundred years ago, on October 28, 1922, Benito Mussolini orchestrated the March on Rome, when 30,000 black-shirted followers coerced King Victor Emmanuel into effectively granting him control of the government. Within weeks, Mussolini installed the first fascist regime in Europe. “One day,” he said to his mother when he was a brooding and violent young boy, “I shall astonish the world.”

Mussolini kept his word. His achievement — the transformation of Italy from an insecure constitutional monarchy into a militarized totalitarian state — impressed a young Adolf Hitler. His charisma — as described by journalist Luigi Barzini, “there was something about him that startled and fascinated almost everybody” — allowed him to bend an entire nation to his will. For two decades Mussolini enjoyed absolute power: He was Il Duce, the leader, the “new man” of the early 20th century, as beloved and feared as any Caesar of the Roman Empire. “His powers were limitless,” writes Barzini in The Italians. “Where his legal prerogatives ended, his undisputed authority and immense personal prestige began.”

Also like the Caesars of old, Mussolini understood something about the human need to worship. In this case, the object of veneration would be the nation-state, embodied in a singular individual, a benevolent superman. As Mussolini proclaimed: “Fascism is not only a party, it is a regime; it is not only a regime, but a faith; it is not only a faith, but a religion that is conquering the laboring masses of the Italian people.”

Mussolini himself had no use for religion; he adopted his father’s atheistic and anti-Catholic outlook. He once derided Christ as “a small mean man who in two years converted a few villages and whose disciples were a dozen ignorant vagabonds, the scum of Palestine.”

The problem for Mussolini, though, was how to avoid a direct confrontation with the Catholic Church, which retained a deep cultural loyalty among ordinary Italians, whatever the quality of their personal faith. Mussolini had introduced the concept of a “totalitarian” political ideology. How could the church be accommodated if fascism could tolerate no rivals? As Mussolini wrote in The Doctrine of Fascism:

Liberalism denied the State in the name of the individual; Fascism reasserts the rights of the State as expressing the real essence of the individual. . . . The Fascist conception of the State is all-embracing; outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have value. Thus understood, Fascism is totalitarian, and the Fascist State—a synthesis and a unit inclusive of all values—interprets, develops, and potentates the whole life of a people.

Talks between the church and the government began in 1926 but stalled over Fascist education policies. The talks resumed, however, and on February 11, 1929, in a dazzling ceremony at the Lateran Palace, Mussolini signed protocols making Vatican City a fully independent enclave within Rome. Its citizens were exempt from Fascist law. Catholic authority over marriage was restored, as was compulsory religious education.

Thus, there were practical limits to Mussolini’s totalitarianism. As biographer R. J. B. Bosworth summarizes it: “Mussolini’s dictatorship had not, would not, and could not storm the citadel of Catholicism.” In praising the protocols, the papal paper, L’Osservatore Romano, declared that “Italy has been given back to God and God to Italy.” Yet Mussolini also got what he wanted: a way for the Italian people to somehow retain spiritual inspiration from Catholicism while directing their most important loyalties to the regime. Indeed, the idolization of the state continued apace: Militant nationalism was the new creed.

Fascist youth organizations — whose motto was “Believe, obey, fight” — were modeled on the Society of Jesus. The anniversary of the March on Rome was stage-managed into a pseudo-religious event, with an early-morning Mass and the mingling of Italian military, Fascist militias, and Catholic priests. Celebrations of military battles, such as the battle of Vittorio Veneto, followed a similar pattern. “Commemoration of Fascist martyrs freely confused Fascism with Christianity,” writes Michael Burleigh in Sacred Causes, “which the presence of so many clerics at such rituals did little to dispel, while Fascist memorabilia owed much to pious kitsch.”

Mussolini himself, despite his personal disdain for the church, was careful to cloak Fascist doctrine in the language of murky spirituality: “Fascism is a religious conception in which man is seen in his inherent relation to a superior law and to an objective will, which transcends the individual and makes him a conscious member of a spiritual society.”

Under the fascist view, citizens derive their sense of purpose and meaning from the regime: It is the state that “makes them aware of their mission,” “harmonizes their divergent interests,” and “leads men up from primitive tribal life to that highest manifestation of human power, imperial rule.” It was a short step from the idolization of the regime to the deification of its supreme leader. “The real novelty of his ambition,” writes Bosworth in Mussolini, “lay in his pretensions to enter the hearts and minds of his subjects, and so install Fascism as a political religion.”

Because he had seized complete control of the media, Mussolini portrayed himself as the only man who could rescue Italy from economic disaster, defeat her enemies, and restore her rightful place on the world stage. “I want to make Italy great, respected, and feared,” he said. As the nation’s youngest prime minister, he always appeared virile and self-assured. Pictures of him swinging a hammer, laying bricks, and cutting corn — usually bare-chested — appeared daily in the newspapers. Glasses that he drank from and pickaxes that he swung during his tours were considered holy relics. “There might be anti-Fascists, but there were few anti-Mussolinians,” writes Christopher Hibbert in Mussolini: The Rise and Fall of Il Duce. “He was not only a dictator. He was an idol.”

Mussolini’s personality cult reached its apex in 1936, when Italy brutally invaded and occupied Ethiopia. The world listened with outrage to accounts of defenseless natives choking on poison gas and being cut down by machine guns. Yet Mussolini had defied the League of Nations — a badge of honor for most Italians — and conquered. Paeans gushed from the Italian press. “Homer, the divine in Art; Jesus, the divine in Life; Mussolini, the divine in Action,” wrote journalist Asvero Gravelli. To others, he was “infallible,” a “titan,” a “genius,” and “divine.” After listening to Mussolini announce from his balcony that Ethiopia had been defeated and that Rome was once again the capital of a great empire, his collaborators were nearly overcome. “He is like a god,” one said. “Like a god?” the other replied. “No, no. He is a god.”

How could the Italian people, who lived amid the headquarters of the universal Catholic Church — whose Catholic-Christian identity was assigned to them at birth — transfer their deepest devotion to a pagan regime led by an irreligious despot? Italy, after all, was one of the victors in the First World War. Its post-war economy was bad, but not as bad as that of Germany. Nevertheless, its domestic conditions made it ripe for exploitation. Widespread poverty, war veterans with no hope of meaningful work, strikes, street violence, the threat of communism, political divisions, and a profound sense of disillusionment — all played a part in the story of a nation of 40 million souls looking for a political savior.

Mussolini, a performer more than a politician, assumed the role. He invented the modern totalitarian state. He took away the freedoms of the Italian people by giving them dreams of a nationalistic paradise nourished by imperialistic glory. He made it seem that Fascism was the evolutionary pinnacle of Western civilization.

In truth, Fascism proved to be a mutation: a wretched distortion of the political and religious ideals of the West. Mussolini’s hubris became his undoing. The democratic forces of the West punctured Italy’s fascist delusions, and the Italian people finished the job. Ousted from power, Mussolini tried to flee the country. He was caught, shot, and hung to cheers and mockery.

Yet Mussolini had legions of devoted followers who clung to hope — a hope severed from reason — like the artist crouching in a cave beneath the streets of Naples. Or like Manlio Morgagni, a journalist, mayor of Milan, and member of the Italian senate. When Morgagni got the news that Mussolini had been forced out of office, he committed suicide. “For over thirty years, you, Duce, you have had all my loyalty,” he wrote in a note. “My life was yours. . . . I die with your name on the lips and a plea for the salvation of Italy.”

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

October 20, 2022

The National Interest: Is This America’s Mussolini Moment?

This article was originally posted at The National Interest.

NAPLES, Italy—At a massive fascist rally on October 24, 1922, a black-shirted Benito Mussolini promised to drain the swamp of the political establishment and restore Italy’s greatness on the world stage. “We shall strangle the old Italian political class,” he told the crowd. They responded by shouting, “Rome, Rome!” Four days later, more than 30,000 squadristi—the fascist squads committed to political violence—marched on the capital.

Thus, a hundred years ago—more than a decade before Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party took over Germany—the first fascist regime was established in the cradle of European civilization. Adored by millions, Mussolini would boast that he had buried “the putrid corpse of liberty.” Biographer Paolo Monelli likened the Italian people’s embrace of “Il Duce” to that of opera stars: “As one does with tenors, they enjoyed his good long notes and the melody without paying any attention to the words, but, if they had listened more carefully, they would not have been surprised by the catastrophe later. He had announced it.”

The same might be said of Donald Trump, whose refusal to accept the 2020 presidential election results looks to many like an assault on liberal democracy. There are various reasons for the resilience of Trumpism, but the most important reason—fear and loathing of the political alternatives—demands our attention. It is what swept Mussolini and the fascists into power.

Italy was on the winning side of World War I, and its postwar economy was not as desperate as that of Germany. Yet its domestic situation was ready to be exploited. War veterans returned to a moribund economy; strikes and civil unrest had become the norm. The sense of disillusionment—650,000 Italian soldiers killed with little to show for it—deepened national divisions. Add to that the 1918 influenza virus, which killed about 466,000 Italians and contributed to a national malaise.

Enter Mussolini, who cast himself as the only man who could shake up the system, rebuild the economy, and end the “paralysis” and “parasitic incrustation” of the Italian state. Like today’s cynics of America’s electoral system, Mussolini derided Italy’s parliament as “the people’s toy,” ripe for a revolution. “What do we want, Fascists?” he asked the crowd. “We have answered quite simply: the dissolution of the present Chamber, electoral reform, and elections within a short time from now.”

King Victor Emmanuel invited Mussolini to become prime minister not because of his political aims, but because of the possibility of a complete breakdown in the rule of law. The growth of communism in Italy—which terrified much of the population—had a lot to do with it.

In the aftermath of the war, local Soviets, districts under communist control, were spreading rapidly. Strikes and riots were breaking out all over the country. Fascist mobs, armed with knives and pistols, clashed with communists, socialists, and their sympathizers. Fascist candidates for the Chamber of Deputies in the elections of October 1919 received only 4,000 votes; their socialist opponents received forty times as many. Mussolini, derided as a political corpse, rebranded himself.

The former socialist and editor of the left-wing Avanti declared himself the only force capable of rescuing Italy from Marxism-Leninism. Mussolini crafted an image as a champion of the poor, of war veterans, and of social justice. Perhaps most importantly, he developed a style of oratory—colorful, blunt, bombastic—that made him a captivating speaker, regardless of his disregard for facts and logic. Luigi Barzini, who covered Mussolini’s rallies as a journalist, said he possessed “an instinctive ability to ride the emotional wave of the day, whatever it was, to know what people wanted to be told, and by what low collective passions they would more easily be swept away.”

The government’s failure to maintain law and order seemed to confirm the claim that Bolshevism could only be stopped by “salutary violence.” Fearful of the militant atheism of the communists, many Catholics supported Mussolini, who spoke respectfully of the church and the “spiritual values” of the Italian people. Like no other political party, the fascists appeared to be “on the side of freedom against tyranny,” writes Christopher Hibbett in Mussolini: The Rise and Fall of Il Duce. “And so the virus of Fascism was allowed to spread.”

Trump and his conservative supporters are often accused of taking a page from the fascist playbook. Under this view, the January 6 insurrection was a botched version of the March on Rome. History will render its judgment of Trumpism. Yet one lesson from Italy’s fascist past must not be missed: The radical, utopian schemes of the political Left fueled a cultural backlash. The communist contempt for capitalism, private property, traditional values, patriotism, Italy’s cultural inheritance—it all made Mussolini’s political vision plausible, even attractive.

“Let it be known,” he declared shortly after seizing power, “that Fascism knows no idols and is no worshipper of fetishes. It has already trampled, and if necessary, will trample again, over the decaying body of the goddess liberty.”

In truth, Mussolini, along with Marx and Lenin, inaugurated the idolization of politics. Hence, the totalitarianism disease—the submission of the individual to an omnicompetent state embodied in a cult of personality—was unleashed. Although fascism is associated with the political Right, its mental outlook can just as easily be found among the political Left. And, as we’ve seen, politically motivated violence defies simple partisan labels.

Whatever the ultimate fate of Trumpism, America’s Mussolini moment is far from over.

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

September 26, 2022

Law & Liberty: A Forgotten Champion of Religious Liberty

This article was originally posted at Law & Liberty.

At the start of Europe’s wars of religion, a Dutch playwright advanced what was arguably the most visionary defense of freedom of conscience ever to appear during the first 1500 years of Christianity.

Dirck Coornhert, a patriot involved in the Dutch revolt against Spain, published Synod on the Freedom of Conscience (1582), a rebuke to both Protestant and Catholic belligerents in light of the moral demands of the gospel. Though rejected in his own day, Coornhert’s even-handed criticism of the intolerant policies of fellow believers would inspire the political outlook of John Locke and, eventually, the American Founders. In our own age of bitter partisanship, Coornhert’s Synod recalls the virtues necessary for a unified and just political order.

Coornhert was born 500 years ago, in 1522, when Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation was sending shock waves throughout Christendom. By the time he wrote the Synod, the breach was irreparable. The Catholic Church had condemned Protestantism as a heresy at the Council of Trent (1545-1563). The French wars of religion (1562-1593) already had claimed thousands of casualties among the Catholic and Protestant communities of France. With the spiritual unity of Europe shattered, sectarian violence threatened to destroy the social fabric of European society.

“Hateful partisanship makes us give false testimony against each other and makes us often accuse others of shortcomings that we ourselves are guilty of inside,” Coornhert wrote. “When it comes down to our own sins we are mild judges, but we are unforgiving towards the sins of others.”

That’s a pretty apt summary of the state of affairs in cancel-culture America. Moreover, not unlike the intense tribalism of American life, Coornhert’s fictional Synod is set in the multi-faith society of the Netherlands, where Anabaptists, Arminians, Calvinists, Catholics, Libertines, Lutherans, Zwinglians and others lived in a state of frequent dispute and friction.

Modeled on the humanist colloquies of the period, the Synod is a nineteen-part dialogue between Catholic and Protestant spokesmen that exposes the hypocritical and intolerant policies of both camps. It is stocked with prominent religious figures, including the Spanish Dominican Melchior Cano; John Calvin, the Reformed leader from Geneva; and Johannes Brenz, a Lutheran minister from Germany. The Synod quotes verbatim from their works, and each session ends with a summary of the various positions. An alternative view is offered by Gamaliel—Coornhert’s alter ego—a figure based on the Pharisee in the New Testament who counsels restraint to religious leaders plotting against Jesus’s disciples.

The unifying thread to the Synod is the Golden Rule: treat others as you wish to be treated. Gamaliel reminds the Reformed delegates, for example, that their Catholic adversaries are members of the same human family. They “are fellow human beings who, just like us, prefer to be kindly tolerated rather than violently forced.” No follower of Jesus, Gamaliel insists, can escape the ethical core of his teaching: “This law applies to both, indeed to all parties. We are all subjected to this law and I wish fervently that we would all act in accordance with it.”

The Union of Utrecht (1579) had enshrined freedom of conscience as the basis of the Dutch Republic; no one was to be punished because of his religious beliefs. Nevertheless, the Reformed Church held an official religious monopoly and prohibited or penalized non-conforming faiths. Coornhert himself had been muzzled by the authorities for criticizing Reformed ministers in print, and he devotes an entire session in the Synod to defending freedom of the press and freedom from censorship. As biographer Gerrit Voogt summarizes it, for Coornhert “free debate and disputation were the lifeblood of a healthy republic.”

Although Coornhert emphasized the inner life of faith over traditional Christian doctrine, he was never flippant about religious belief or the desire to honor the teachings of the Bible in public life. The antidote to false or controversial teaching, he believed, was not state-sanctioned crackdowns. Rather, the remedy was “to kill the heresy by means of the truth”—that is, to discuss and debate the meaning of the Scriptures. If the goal was to lead people into a deeper commitment to Christ, he reasoned, “what weapons could then be more useful or necessary to you than the power of God?”

The Synod doesn’t explain how a multi-confessional state might function. But it articulates political principles that would supply the building blocks for a more liberal society. In a striking passage, Coornhert quotes a Reformed author who wrote that because men and women are spiritual beings by nature, no authority could “drive religion from the heart,” the realm over which God retains exclusive authority:

The prosperity of the kingdom requires solid and sincere concord among all inhabitants. Now we can only have solid concord when all inhabitants enjoy common and equal rights, and this especially in religion. That is why the king should embrace all his subjects with a common and equal love, and this especially in the greatest and weightiest matter of all, religion. It is rooted so deep in people’s hearts that one could not find a better or more lasting seal of concord anywhere.

We must not miss the radical quality of the Synod’s argument. The unquestioned assumption in Coornhert’s day, held by Protestants as well as Catholics, was that the prince should use his political authority to uphold the teachings of the favored, established religion. This meant enforcing doctrinal conformity and punishing dissenters—with civil penalties, prison, banishment, or execution. It was an article of faith that the alliance of church and state toward this end was the only hope of establishing political unity and social peace.

Yet Coornhert reproves Lutherans, Reformed, and Catholics alike for forbidding each other’s teachings whenever they gain political power and “have the magistrate on their side.” He then flips the argument for stability on its head. If the prince seeks political security, he must not play favorites in matters of religion: “But wise politicians call inequality among the inhabitants or citizens of a country a pestilence to the commonwealth, as by the same token equality is the strongest bond of concord and stability.”

In a way that almost no one in the West had ever attempted, Coornhert made a biblical argument that the flourishing of the state depended upon the principle of equal justice: Every person, regardless of religious belief, must enjoy equal rights under the law.

A century later, this idea, known as the “great rule of equity,” began to take hold. “In the course of the seventeenth century,” writes historian Perez Zagorin, “the Dutch Republic acquired the reputation of being the most tolerant, pluralistic society in Europe.” This concept became a central element in John Locke’s proposal for a multi-faith political community. When he was in political exile in the Netherlands in the 1680s, just before he wrote his great defense of religious liberty, Locke acquired Coornhert’s Synod along with other tolerationist works. The primary duty of the civil magistrate, Locke explained, was the “impartial execution of equal laws” for all citizens of the commonwealth. “The sum of all we drive at,” he wrote in A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), “is that every man enjoy the same rights that are granted to others.”

It is true that Locke, though considered the father of the liberal project, would not extend equal rights to atheists. He shared the widely held view that “the taking away of God, though even in thought, dissolves all.” No one imagined that private morality and public virtue could be sustained without belief in a Creator. Nevertheless, in this principle of equity we can discern the political application of the Golden Rule, the moral taproot of constitutional democracy. Here is a vision of a pluralistic society, where the equal protection of fundamental rights creates a unified political community.

To reject this vision in order to defend “orthodoxy,” warned Coornhert, invited the judgment of heaven. “The prophets, the apostles, so many thousands of martyrs, and even the Son of God were put to death under the color of religion,” he wrote. “One day an account must be given of all this blood by those who have been shedding it so frivolously when they struck blindly during the night of ignorance.”

One could argue that the age of ignorance has returned: Coornhert would likely recognize the vengeful and apocalyptic rhetoric that characterizes American political discourse. He would challenge Americans to put aside partisan loyalties, treat one another as “fellow human beings,” and seek the good of the commonwealth. Other thinkers would play their part in the journey toward a more just and democratic society, notably in England and the American colonies. But it was a Dutchman, half a millennium ago, who pierced the darkness of his age and took a courageous stand for human freedom.

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

September 16, 2022

The National Interest: Toleration, Liberalism, and Lessons for a Fractured America

This article was originally posted at The National Interest.

TRENTO, Italy—Just two years after the Catholic Church completed its repudiation of Protestant doctrine at the Council of Trent (1545-1563), an Italian convert to Protestantism jumped into the fray. A layman trained as a lawyer, Jacopo Acontius delivered a brief that exposed the dark psychology of persecution in ways no one had ever attempted. His singular work, Darkness Discovered: Or the Devil’s Secret Stratagems Laid Open (1565), offered a defense of religious freedom that helped to revolutionize the relationship between church and state in the West.

“The best way to find out the devil’s Stratagems,” Acontius wrote, “is to take into serious consideration what the end is at which all his consultations aim, which is not Very hard to tell.” Satan’s great purpose, he said, is to lead men and women away from life with God—to lead them into conflict, misery, and death. This, he explained, was the consequence of the disputes over religion that threatened to overwhelm Europe. “Thus is the people divided into Sects which hate one another with deadly feud, abstaining from no kind of injuries, and … do not observe how in so doing they obey their own passions, but think they very much please God.”

The bitter sectarianism that enveloped sixteenth-century Europe offers a warning about the tribalism that now darkens American public life. Just as our modern culture wars have taken on a militant quality, so, too, did the disagreements over fundamental religious questions degenerate into violence. Europeans no longer seemed able to live together, as every dispute became a political question, framed in apocalyptic terms.

Such was the world as Acontius encountered it early in his career. Born into a Catholic family in about 1500 in or near Trento, he received a classical education, evidently immersed in the works of Aristotle, Plato, and Archimedes. We don’t know what circumstances led to his conversion, but as the Protestant Reformation spread through the continent, Acontius joined other Italian Protestants who fled to Switzerland. He met Italian Academicians educated in the humanism of the Renaissance.

Acontius also encountered the repressive policies of the contending religious communities. In Geneva, John Calvin set off a debate among Protestants when, in 1553, he authorized the execution of Servetus on charges of heresy. In the Netherlands, Catholic Spain struggled to contain the growing Calvinist minority. In France, the religious wars between Calvinists and Catholics (1562-1593) were already devastating much of the country.

What distinguished Acontius from other defenders of religious toleration—and there were not many in his day—was his desire to expose the scandal of persecution by getting to the root of the problem: the moral disposition of man. “Acontius sought to analyze and explain the psychology which underlies all religious persecution,” writes W.K. Jordan in The Development of Religious Toleration in England, “and his contribution in this regard has probably never been equaled.”

Arguing from Scripture, Acontius agreed that mankind was a being created good and in every way perfect, “yet breaking the command of God, he became of another Nature quite contrary, exceedingly corrupt and liable to all manner of vice.” Humanity’s vices—which Satan sought to exploit—included inordinate self-love, moral blindness, and self-righteousness.

The desire to persecute others, Acontius believed, was primarily the result of intellectual arrogance: a supreme confidence in the truth and rightness of one’s views. It was a weakness that afflicted ministers as readily as monarchs.

The character of European society, in which religious leaders held unquestioned authority, created a repressive dynamic. As Acontius summarized it, “every man’s life and reputation lies open to the lash of those they call Preachers.” And the preachers, he wrote, were especially prone to pride. If an individual disagreed with them—and thus challenged their knowledge or competence—he would “come under their censure” and “shall quite lose his credit.”

The problem was exacerbated by the church-state relationship. Once the pattern was set that religious controversies would be decided by the magistrate, he would not resist the temptation to abuse his power. Like the preacher, he would regard anyone who contradicted him as a heretic. Thus, Satan’s strategy, Acontius wrote, was to manipulate the political authority to implement the whims of an arrogant and embittered clergy. “But who is there bearing the sword, that will not be accounted godly, and that will not account for an Heretic whosoever thwarts him in matters of Religion?” The final arbiter of truth would be the hangman.

Persecution, instead of dampening disagreements over religion, made the problem worse. Dissenters hardened their position, convinced that their opponents were acting out of malice. “For they do not destroy errors, but make them invincible; they do not pluck them up, but they propagate them; they do not destroy them, but the multiply them in great abundance.” The result: the growth not only of sects and heresies but also of hatred and disorder. “And thus by a kind of Contagion the evil is spread far and near.”

This cycle of repression and social unrest, Acontius emphasized repeatedly, was rooted in “the disposition of man, naturally prone to pride and over great haughtiness of mind.” Its ultimate cause could be found in the Creation story: the temptation from the serpent in paradise that man could become like God. “So hath there ever since stuck such a persuasion in Mankind, that every man takes himself to be a kind of Deity.” In Darkness Discovered, Satan could be viewed not only as an actual malevolent being, but also as a symbol of human arrogance.

The answer to the problem of persecution was multi-faceted. First, Acontius placed an enormous emphasis on the need for rational argument, civil debate, and free inquiry. The persecution of alleged heretics simply encouraged the base motives of political and religious leaders. “His solution,” writes W.K. Jordan, “was rather to use moral and rational persuasion and to leave the heretic to the working out of his own salvation.”

Second, Acontius offered an approach to religious belief that would move it out of the realm of politics, beyond the reach of the state. “If there be controversies in Religion, let them contend on both sides with Scriptures and Arguments, but let the Magistrates look to it again and again, that they may under a penalty abstain from whatsoever may tend to provoke one another.” It was not the job of the political authority to enforce doctrinal orthodoxy.

The deepest remedy to the “contagion” of persecution, though, was a return to basic biblical concepts about God and his great patience toward sinners. The person who seemed to be in grave spiritual error, who had wandered from the fold of God, may not always remain so. Isn’t it possible, Acontius asked, that he “shall at length be found by that best of shepherds, healed and brought back to the flock?” The possibility demanded charity.

For Acontius, the supreme example of mercy was Jesus. The accuser’s eye should be fixed on him and not on the man he considered a heretic. “Thou oughtest not therefore to look upon his person, but upon the person of Christ whom he represents, and to remember how great his love hath been to thee,” he wrote. “In so much as he refused not, being himself just and innocent, to die for thee an unjust person, and the greatest of sinners, especially by so cruel and bloody a death.” In other words, the prime obligation of Christians caught up in theological disputes was to ponder the great love and mercy of Christ for them, expressed in his sacrificial death on the cross.

Here was a plea for Christian charity that would not be forgotten. When the English philosopher John Locke was in political exile in the 1680s in the Netherlands, shortly before he wrote his signature defense of religious freedom, he read Darkness Discovered, which was circulating among the dissenting Protestant community that had befriended him.

Locke purchased other tolerationist works while he was in Holland, but he seems to have been especially moved by the arguments he encountered from Acontius. Locke began A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), for example, by insisting that a demonstration of humility over religious differences was the identifying mark of the followers of Jesus. “If, like the Captain of our salvation, they sincerely desired the good of souls, they would tread in the steps and follow the perfect example of the Prince of Peace”—an example of patience and love in the face of intense hostility.

Like Acontius, Locke elevated the faculty of reason and the “inner persuasion of the mind” in matters of faith. “It is only light and evidence that can work a change in men’s opinions; and that light can in no manner proceed from corporal sufferings, or any other outward penalties.” Coercion produced hypocrites, he wrote, not true believers.

Locke also picked up on the idea of keeping the magistrate out of religious disputes—and took it to its logical conclusion. The power of the state, he wrote, “is confined to the care of the things of this world, and hath nothing to do with the world to come,” whereas “the church itself is a thing absolutely separate and distinct from the commonwealth.” The boundaries between these two institutions, Locke declared, “are fixed and immovable.”

Thus, the roots of liberal democracy—a political society based upon religious freedom and characterized by religious pluralism—were planted deeply into the soil of European thought.

Other thinkers, authors, and rebels would nurture this concept of freedom over the course of two centuries. Yet they were always in the minority. Jacopo Acontius stands out among them. His bold and generous vision was noted by John Dury in his prefatory note to the 1648 English translation of Darkness Discovered:

To be carried along with the stream, or to be silent when matters are not carried according to our mind, is no hard matter to any that hath any measure of discretion; but to row against the stream, to labor against the wind and tide, and the whole current of an age…is not the work of an ordinary Courage.

A man struggling against the strongest tides of convention in his day—against the authorities of church and state, and the threat of censure, disgrace, and persecution—with little to gain and, in worldly terms, everything to lose. Yes, no ordinary work of courage.

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

August 2, 2022

National Review: One Hundred Years Ago, ‘Following the Science’ Meant Supporting Eugenics

This article was originally posted at National Review.

In the 1920s, when he was still an agnostic, C. S. Lewis noted in his diary his latest reading: “Began G. K. Chesterton’s Eugenics and Other Evils.”

A controversial English Catholic writer, Chesterton published his book in 1922, when the popularity of eugenics was at flood tide. Respectable opinion on both sides of the Atlantic embraced the concept: a scientific approach to selective breeding to reduce, and eventually eliminate, the category of people considered mentally and morally deficient. From U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes to Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger, eugenics policies — including involuntary sterilization — were hailed as a “progressive” and “compassionate” solution to mounting social problems.

A hundred years ago, Chesterton discerned something altogether different: “terrorism by tenth-rate professors.” For a time, he stood nearly alone in his prophetic assault on the eugenics movement and the pseudo-scientific theory by which it was defended.

“People talk about the impatience of the populace; but sound historians know that most tyrannies have been possible because men moved too late,” Chesterton warned. “I know that it numbers many disciples whose intentions are entirely innocent and humane; and who would be sincerely astonished at my describing it as I do. But that is only because evil always wins through the strength of its dupes.”

Chesterton declared his aim openly, without qualification or compromise: The ideology of eugenics must be destroyed if human freedom is to be preserved. The eugenic idea, he wrote, “is a thing no more to be bargained about than poisoning.” In the end, it would require the discoveries at the death camps at Auschwitz and Dachau for most of the world to finally reject the horrific logic of eugenics. Yet Chesterton was one of the first to see it coming: when the machinery of the state would invoke the authority of science to deprive individuals — both the “unfit” and the unborn — of their fundamental human rights.

It is hard to overstate the degree to which eugenics captured the imagination of the medical and scientific communities in the early 20th century. Anthropologist Francis Galton, who coined the term — from the Greek for “good birth” — argued that scientific techniques for breeding healthier animals should be applied to human beings. Those considered to be “degenerates,” “imbeciles,” or “feebleminded” would be targeted. Anticipating public opposition, Galton told scientific gatherings that eugenics “must be introduced into the national conscience like a new religion.” Premier scientific organizations, such as the American Museum of Natural History, and institutions such as Harvard and Princeton, preached the eugenics gospel: They held conferences, published papers, provided research funding, and advocated for sterilization laws.

To many thinkers in the West, the catastrophe of the First World War, in addition to the problems of poverty, crime, and social breakdown, suggested a sickness in the racial stock. Book titles help tell the story: Social Decay and Degeneration; The Need for Eugenic Reform; Racial Decay; Sterilization of the Unfit; and The Twilight of the White Races. The American Eugenics Society, founded in 1922 — the same year Chesterton published Eugenics and Other Evils — was supported by Nobel Prize–winning scientists whose stated objective was to sterilize a tenth of the U.S. population.

The Supreme Court paved the way. Justice Holmes, a political progressive and eugenics advocate, wrote the 1927 Court opinion in Buck v. Bell, an 8–1 ruling upholding Virginia’s sterilization laws. He summed up the court’s philosophy thus: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Within a decade, laws mandating sterilization of those considered a threat to the gene pool — alcoholics, criminals, undesirable immigrants, African Americans — were passed in 32 states. Eventually, at least 70,000 people were forcibly sterilized, from California to New York.

As a Christian philosopher, Chesterton acknowledged the historic problem of churches’ enlisting the secular state to enforce religious doctrine. But he turned the issue around by accusing scientific elites of repeating the errors of the Inquisition:

The thing that really is trying to tyrannize through government is Science. The thing that really does use the secular arm is Science. And the creed that really is levying tithes and capturing schools, the creed that really is enforced by fine and imprisonment, the creed that is really proclaimed not in sermons but in statutes, and spread not by pilgrims but by policemen — that creed is the great but disputed system of thought which began with Evolution and has ended in Eugenics.

Under the eugenics vision, society’s most vulnerable would not find compassion and aid; they would find the surgeon’s knife. As Chesterton quipped, there would be no sympathy for the character of Tiny Tim, the crippled boy of the Cratchit family in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. “The Eugenicist, for all I know, would regard the mere existence of Tiny Tim as a sufficient reason for massacring the whole family of Cratchit.”

These facts are worth recalling in light of the debate set off by the recent Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Margaret Sanger trumpeted the eugenic features of birth control and found support from the nation’s leading eugenicists. As she put it in a speech at the 1921 International Eugenics Congress in New York: “The most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the overfertility of the mentally and physically defective.”

At the heart of the eugenics movement, Chesterton believed, was an utterly materialistic view of the human person: man as laboratory rat. “Materialism is really our established Church,” he wrote, “for the Government will really help it to persecute its heretics.”

The sobering truth is that the scientific community played the decisive role in the political and social acceptance of eugenics. Members across the medical and scientific professions used their immense cultural authority to persuade educators, lawmakers, jurists, journalists, and clergy that eugenics offered the best hope of rescuing the human race from decay and even extinction. Henry Osborn, a paleontologist and co-founder of the American Eugenics Society, summed up their outlook thus: “As science has enlightened government in the prevention and spread of disease, it must also enlighten government in the prevention of the spread and multiplication of worthless members of society . . .”

The ultimate political triumph of this idea, of course, arrived with the Nazis and their assault on the handicapped, homosexuals, gypsies, Jews, and anyone considered an enemy of the state. Indeed, Nazi doctors corresponded with American eugenicists as they designed their own sterilization programs.

The eugenics movement, as Chesterton predicted, became a wretched story of the negation of democratic ideals to serve a utopian vision. “Hence the tyranny has taken but a single stride to reach the secret and sacred places of personal freedom,” he wrote, “where no sane man ever dreamed of seeing it.” Wittingly or not, the eugenic dream unleashed a cataract of deeply rooted fears and hatreds — sanctified this time by a secular priesthood, the scientific community.

C. S. Lewis, the Oxford don whose conversion to Christianity was aided by Chesterton’s theological writings, also watched these developments with horror. Like Chesterton, he warned of the scientist untethered from the restraints of traditional morality or religion.

“The man-molders of the new age will be armed with the powers of an omnicompetent state and an irresistible scientific technique,” Lewis wrote in The Abolition of Man. In such an age, he predicted, man’s supposed conquest over nature would not lead to his liberation — quite the opposite. “For the power of Man to make himself what he pleases means, as we have seen, the power of some men to make other men what they please.”

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

June 21, 2022

Wall Street Journal: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lesson About Evil for Our Time

This article was originally posted at The Wall Street Journal.

[image error]

When the Soviet Union sent half a million troops into Finland on Nov. 30, 1939, J.R.R. Tolkien was sharing a glass of gin with his friend C.S. Lewis and reading him a chapter from his new story about hobbits, “The Lord of the Rings.”

It was the 19th-century Finnish epic, “The Kalevala,” that so impressed Tolkien as a young man and helped to inspire his own story. A collection of ancient songs and myths, “The Kalevala” gave the Finnish people a history and a cultural tradition—a national identity—of their own. And it is credited with helping the Finns to break away from Russian rule during World War I.

It seems likely that Finland’s fierce resistance to Russian aggression during World War II also worked on Tolkien’s imagination when he turned again to writing “The Lord of the Rings.” Not unlike the Ukrainians today, the Finns frustrated Russian plans for a quick victory. Moreover, the emergence of totalitarian regimes in Moscow and Berlin shattered European illusions about the preservation of peace in the face of evil—a theme that animates Tolkien’s mythology about the struggle for Middle-earth.

Tolkien was teaching at Oxford in 1933 when students at the Oxford Union Society approved the motion: “This House will under no circumstances fight for its King and country.” It was a shock to the political establishment. And it was a bad omen: Adolf Hitler had just become chancellor of Germany and was drawing up secret plans for remilitarization.

Tolkien began writing “The Lord of the Rings” in 1936, the same year Germany occupied the Rhineland and intervened on behalf of the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. In his introduction to the Shire and its inhabitants, Tolkien might well have been describing isolationist England under Neville Chamberlain: “And there in that pleasant corner of the world they plied their well-ordered business of living, and they heeded less and less the world outside where dark things moved, until they came to think that peace and plenty were the rule in Middle-earth and the right of sensible folk.”

A combat veteran of World War I, Tolkien watched with dread the rise of ideologies unleashed in the war’s aftermath: communism, fascism, Nazism and eugenics. Almost as soon as he began writing “The Lord of the Rings,” it took on adult themes not found in “The Hobbit.” Although Tolkien denied that his work was allegorical, he acknowledged in a 1938 letter to his publisher that his new story “was becoming more terrifying than the Hobbit. . . . The darkness of the present days has had some effect on it.”

Less than a year later, Britain was at war with Nazi Germany, its policy of appeasement in tatters. As Gandalf the Wizard explains to Frodo Baggins: “Always after a defeat and a respite, the Shadow takes another shape and grows again.” Or, as Elrond, the Lord of Rivendell, intones, “And the Elves deemed that evil was ended forever, and it was not so.”

Tolkien’s epic story embodies a moral tradition known as Christian realism: a belief in the existence of evil and in the obligation to resist it. We can hope that Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine will prod leaders in Europe and the U.S. to recover this outlook.

In Tolkien’s world, indifference to the evil of Mordor is portrayed as an evasion that can only result in catastrophe. Ending a decadeslong policy of nonalignment, the Finnish parliament recently approved a plan to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization—a turnabout that brings to mind a warning from Gildor the elf to the Shire: “The wide world is all about you: you can fence yourselves in, but you cannot forever fence it out.”

As a writer of fantasy, Tolkien has been accused of escapism. In fact, he used the language of myth not to escape the world but to suggest how humble, ordinary people—the hobbits—could confront with courage the sorrows, temptations and dangers of this world. In his review of “The Lord of the Rings,” Lewis wrote, “As we read, we find ourselves sharing their burden; when we have finished, we return to our own life not relaxed, but fortified.”

When Britain was thrust into the most destructive conflict in human history, Tolkien reached for an older literary tradition to find strength and resilience. He sought to give the English people what “The Kalevala” had given the Finns. The result was a war story, wrapped in myth, that teaches fundamentals about the human condition: harsh realities about the will to power and the virtues needed to stand against it.

—

Joseph Loconte is a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Grove City College and Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy. He’s also the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

June 9, 2022

National Review: Russia and Realism, American-Style

This article was originally posted at National Review.

At the start of the Cold War, American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr addressed critics of his magazine, Christianity and Crisis, who faulted him for taking a hard line against Joseph Stalin’s Russia. Niebuhr recalled that many of America’s domestic critics also believed that Nazi Germany could not be as bad as it seemed because we were not as good as we pretended. In this, he wrote, they failed to see the geopolitical realities staring them in the face.

“America is no shining light of democratic justice,” he wrote in 1947. “But that still does not change the fact that the generous nineteenth century Marxist dream of a universal classless society has changed into a nightmare of Russian tyranny, and that the free peoples of the world hope that they can count on our support in avoiding a new enslavement.”

As Vladimir Putin wages a remorseless war of aggression against Ukraine, the free peoples of the world are no doubt wondering the same thing. Indeed, in his speech to the United Nations Security Council last month, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky exposed the utter moral dysfunction of the U.N. system — an institution that was conceived, designed, and funded by the United States to ensure international peace and security: “I would like to remind you of the first article of the U.N. Charter. What is the purpose of our organization? To maintain peace. . . . Now the U.N. Charter is being violated literally from the first article. And, if so, what is the point of all the other articles?” Zelensky pressed home the point: “We are dealing with a state that turns the right of veto in the U.N. Security Council into a right to kill.” As he spoke, fresh evidence of Russian atrocities against civilians was being uncovered in Bucha and other cities in Ukraine.

In confronting the challenge that Russia now poses to international security, it’s vital to consider the role that America played in establishing a new world order at the end of the Second World War: a burden of leadership unprecedented in modern diplomatic history.

At its best moments, the United States has rejected both isolationism and utopianism and adopted a policy of realism — not a manipulative Machiavellian realism, but something that Niebuhr called “Christian realism.” It is a political outlook that takes seriously the biblical concept of the Fall of man, while avoiding cynicism about mankind’s inherent dignity and capacity for self-government. As Niebuhr viewed it, Christian realism draws upon America’s political and religious ideals — American exceptionalism — to help constrain its immense military and economic power and to deploy this power in the cause of human freedom.

Toward this end, for example, the United States led an alliance of democratic nations that agreed to fight the Axis Powers until final victory. On January 2, 1942, representatives from 26 countries — which Franklin Roosevelt called the “United Nations” — issued a declaration of war aims. They explained that victory was essential in order “to defend life, liberty, independence and religious freedom and to preserve human rights and justice” in the lands of the signatory nations “as well as in other lands.”

The core doctrine of the U.N. Charter protecting national sovereignty, “based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples,” owes a massive debt to American constitutionalism and the principle of government by consent. Likewise, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, drafted in the wake of Nazi atrocities, draws inspiration from the U.S. Bill of Rights. Indeed, the UDHR’s affirmation of mans’ natural and unalienable rights echoes the natural-rights arguments in John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, a favorite among the Founders: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

Here is the imprint of American idealism on the political architecture of the United Nations. Charles Malik, the Lebanese ambassador to the United Nations and one of the drafters of the UDHR, confessed his admiration for America’s democratic principles: “I cannot imagine the declaration coming to birth under the aegis of any other culture emerging dominant after the Second World War.”

Nevertheless, idealism requires the ballast of Christian realism. This brand of realism was missing when the permanent membership of the U.N. Security Council included the Soviet Union — the epicenter of atheistic communism, a collaborator with Nazi Germany in the dismemberment of Poland, and a ruthless dictatorship without regard for basic human rights. This Faustian bargain guaranteed that an institution at the heart of the U.N. system would be fatally compromised.

Indeed, the United Nations, for all of the good intentions of its founders, was a project crippled by liberal delusions about human nature and the nature of political societies. “In this liberalism there is little understanding of the depth to which human malevolence may sink and the heights to which malignant power may rise,” Niebuhr wrote in Christianity and Power Politics. “Some easy and vapid escape is sought from the terrors and woes of a tragic era.”

The international crisis set off by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has revealed the abject failure of escapism as a substitute for political realism. “Are you ready for the dissolving of the U.N.?” asked Zelensky. “Do you think that the time of international law has passed?” He bluntly challenged America and her democratic allies to help Ukraine check Russian aggression and expel Russia from the Security Council — or dissolve the institution outright.

There is at this hour a critical need for the United States to think and act creatively, with sober moral judgment, as it exercises its leadership responsibilities in light of a resurgent Russia. It has done so in the past — to great effect.

Within months of the end of the Second World War, for example, America acted decisively to hold the Nazi leaders to account for their wartime crimes. Alone among the great powers, the United States insisted upon an international tribunal, the Nuremberg trials, to judge the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime. America rejected the call for mass executions or show trials.

Instead, it set a new standard of justice for punishing crimes against humanity — not unlike the crimes now being committed by Russian forces in Ukraine. Robert Jackson, the lead prosecutor for the United States at the Nuremberg trials, put the case thus in his opening statement: “The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating, that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated.” The Nuremberg trials are widely credited with helping Germany to confront its Nazi past and reintegrate itself into the democratic West.

When Joseph Stalin launched a Soviet blockade of democratic West Berlin to force the withdrawal of American troops from West Germany, the United States rejected both isolationism and militarism. President Harry Truman ordered American pilots into the city — not on bombing raids, but on a mission of rescue. Over the next 323 days, the Berlin airlift delivered 2.3 million tons of food and fuel to preserve the lives and freedoms of their former enemies. Stalin ended the blockade, and West Berlin remained free and independent.

When the Soviet Union threatened to extend its grip over the nations of Western Europe and reduce their populations to servitude — as it had done in Eastern Europe — the United States stepped into the breach.

General George Marshall, who witnessed firsthand the ravaging effects of war on civilian populations, conceived of an economic lifeline for Europe. Begun in 1948, the Marshall Plan, costing U.S. taxpayers more than $13 billion (about $135 billion in today’s dollars), stabilized the vulnerable economies of 16 nations. Soft power was backed by hard power: the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance, the most successful political–military alliance in history. These policies rescued Western Europe from social breakdown and Soviet rule and made possible the astonishing transformation of illiberal societies into peaceful, free-market, democratic states.

America’s Cold War policy was rooted in its civilizational confidence: the belief that the American creed of human freedom and equality, based upon mankind’s unalienable rights, applied to people everywhere. In other words, American exceptionalism carried implications for everyone striving for a more just and humane world.

At the end of the Second World War, the United States was correct to insist that international peace and security depended upon the protection of man’s basic rights and freedoms. In the words of the U.N. Charter, each member state must “reaffirm faith . . . in the dignity and worth of the human person” and “in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small.” The rejection of this concept leads only in one direction: It invites the forces of disorder, violence, and dictatorship, which thrive on democratic weakness.

Even as the United States and Great Britain were battling Nazi Germany during the Second World War, Winston Churchill worried about Russian imperialism: “It would be a measureless disaster if Russian barbarism overlaid the culture and independence of the ancient States of Europe.”

The shadow of Russian barbarism has returned — and the impulse toward isolationism will not drive it out. As Reinhold Niebuhr warned, the exercise of American power always involves a measure of risk and hubris, but “the disavowal of the responsibilities of power can involve an individual or nation in even more grievous guilt.”

—

Joseph Loconte is a Senior Fellow at the Institute on Religion and Democracy and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. The trailer for the forthcoming documentary film series based on the book can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com.

June 8, 2022

National Review: When Ronald Reagan Sent the Soviet Union to the Ash Heap of History

This article was originally posted at National Review.

In the throes of the Cold War, when the American political and academic establishments almost in their entirety took for granted the continued strength and global influence of the Soviet Union, Ronald Reagan delivered a jeremiad against it — a prophecy about the total collapse of the Soviet communist empire.

Forty years ago, on June 8, 1982, Reagan stunned members of the British Parliament at Westminster when he turned Marxist revolutionary theory on its head:

In an ironic sense Karl Marx was right. We are witnessing today a great revolutionary crisis, a crisis where the demands of the economic order are conflicting directly with those of the political order. But the crisis is happening not in the free, non-Marxist West, but in the home of Marxism-Leninism, the Soviet Union. It is the Soviet Union that runs against the tide of history by denying human freedom and human dignity to its citizens.

Unlike today’s political Left and the New Right, Reagan believed deeply that liberal democracy — based on respect for the natural rights and freedoms of every person — was the best vehicle for human flourishing. Regimes founded upon the rejection of God and the negation of individual freedom, he said, would not endure.

Unlike today’s cynics and isolationists who reject America as a standard-bearer for democracy and human rights, Reagan announced a strategy for promoting democratic reform around the globe. “What I am describing now is a plan and a hope for the long term — the march of freedom and democracy which will leave Marxism-Leninism on the ash heap of history, as it has left other tyrannies which stifle the freedom and muzzle the self-expression of the people.”

Like no Cold War president before him, Reagan repudiated the doctrine of containment: The West would not merely restrain the growth of Soviet totalitarianism; it would triumph over it. Reagan’s rhetoric, his belief in American exceptionalism, enraged the apparatchiks in the Kremlin, as well as their liberal sympathizers in the American academy.

Indeed, it’s easy to forget that, to many in the West, the Soviet Union looked unstoppable. The Soviets had achieved strategic parity in the arms race and deployed nuclear missiles in Eastern Europe. Their satellite states were utterly compliant, and Moscow was waging proxy wars in Central America and southern Africa. The United States, by contrast, was still reeling from its catastrophic failure in Vietnam; the American economy was in a deep recession.

Thus, the popular view was one of equivalence: The United States and the Soviet Union had equally flawed, morally ambiguous political systems. They must work to “converge” and compromise for the sake of world peace. “Each superpower has economic troubles,” announced historian Arthur Schlesinger after a 1982 trip to Moscow. “Neither is on the ropes.” Harvard’s John Kenneth Galbraith parroted the Kremlin’s propaganda: “The Russian system succeeds because, in contrast to the Western industrial economies, it makes full use of its manpower.” MIT economist Lester Thurow called it “a vulgar mistake to think that most people in Eastern Europe are miserable.”

Reagan knew this was nonsense talk: He singled out and praised the democratic forces stirring in Poland. Launched in 1980, Solidarity, the first independent trade union behind the Iron Curtain, had gained more than 10 million members in a country of 36 million people. The movement was devoutly pro-Catholic, anti-communist, and pro-West. Its leaders campaigned for freedom of religion, speech, and the press and for free elections.

Six months before Reagan’s speech, in December 1981, Polish security forces had rolled into Warsaw, set up roadblocks, and arrested 5,000 Solidarity members in a single night. With Moscow’s backing, the communist regime declared martial law, driving the Solidarity movement underground. Reagan’s response to the Soviet crackdown in Poland delivered a clear message about America’s democratic objectives — unlike the mixed messages being sent by America’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

We can be grateful that the partisan voices degrading our political discourse today did not occupy the White House in 1982. The progressive Left, after all, views the United States as a racist and imperialist hegemon; the nationalism of the New Right renders it indifferent to human suffering outside our borders. Neither group would have exploited the crisis engulfing the Soviet Union.

Reagan understood that America’s security was linked to the security and freedom of Europe — and that Poland was poised to become the catalyst for massive democratic reform. “Poland is at the center of European civilization,” Reagan said. “It has contributed mightily to that civilization. It is doing so today by being magnificently unreconciled to oppression.”

As Reagan made clear in his speech, America’s plan to defeat Russian aggression involved both hard power and soft power. Reagan’s focus at Westminster was the latter: