Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 6

September 22, 2021

National Review: The Freedom Letter to the Romans

This article was originally posted at National Review.

This essay series explores Italy’s unique contribution to the rich inheritance of Western civilization, offering a defense of the West’s political and cultural achievements. Find previous installments here, here, here, and here.

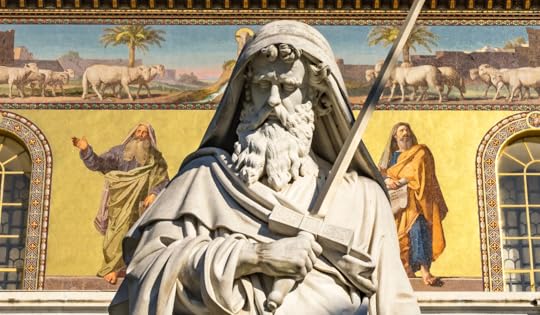

Rome, Italy — Outside the Basilica San Paolo Fuori le Mura, commonly known as the Basilica of Saint Paul, stands an imposing marble statue of a man who appears ready to do battle with the world. Bearded and hooded, he clutches a Bible in his left hand and a long cross in his right — but holds the cross over his chest as if it were a sword. It is a fitting representation of the man whose writings arguably have done more to rout the forces of bigotry and tyranny than those of any other figure in history.

Saul of Tarsus, an observant Jew who was renamed Paul after his dramatic conversion to Christianity, claimed a divine calling to bring the message of Jesus to those outside the Jewish faith, that is, to the Gentiles. His mission ended here when, according to tradition, he was executed by the authorities of Rome. Hence, the historical irony: Paul’s letter to the believers in Rome, the theological loadstar of the Christian church, helped to topple the regime that could not tolerate his uncompromising message of redemption.

A relentless evangelist with almost reckless courage, Paul is the dominant figure in the early decades of the Christian movement. Of the 27 documents that compose the New Testament, 21 are letters; 13 of them are attributed to Paul. His Letter to the Romans stands apart. Written around 57 a.d., near the end of his career, it contains the most thorough exposition of Christian doctrine in the Bible. It also advances concepts considered utterly radical for their time — ideas that would shape the course of Western civilization and the American political order.

In his Social Contract (1762), Jean Jacques Rousseau claimed that “Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” Paul disagreed. To the apostle, every person was born into a state of spiritual slavery and death. Everyone stood guilty before a holy God, no matter what their achievements or circumstances: “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). His second proposition remains as controversial today as when it first appeared: Jesus was sent by God to set people free, making salvation available to everyone through faith in his death and resurrection. “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord, and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Romans 10:9). The last proposition, which follows from the others, involves an astonishing universalism. “There is no difference between Jew and Gentile — the same Lord is Lord of all and richly blesses all who call on him” (Romans 10:12). The sacrifice of Jesus renders null and void the deep, cultural divisions within the human family; all are welcomed into God’s new spiritual community.

In a way no ancient text had contemplated, the Letter to the Romans introduced two great themes into the bloodstream of the West: human equality and human freedom. No ideas in the history of political thought would prove more transformative and ennobling.

Some of history’s most influential figures have considered Paul’s letter their north star. Scholars often draw attention to the role of the letter in the conversion of Augustine of Hippo. This saint’s Confessions (circa 400 a.d.) grew out of his meditations on Romans, Chapter 7, with its description of how faith in Christ empowers the individual to prevail in the struggle against sin. Yet Augustine’s epic defense of the faith, The City of God (426 a.d.), also owes an immense debt to the central themes of Romans. “In the city of the world both the rulers themselves and the people they dominate are dominated by the lust for domination,” he wrote, “whereas in the City of God all citizens serve one another in charity.”

More than a thousand years later, when Christendom was racked by a series of internal crises, an Augustinian monk turned to the Letter to the Romans in his own desperate quest to find peace with God. Martin Luther, a professor of the Bible at Wittenberg University, was initially terrified by the concept of the “righteousness of God” as described in Romans, Chapter 1. His insight — what he regarded as a recovery of the gospel of grace — completely upended his life:

I had greatly longed to understand Paul’s letter to the Romans. . . . I grasped the truth that the righteousness of God is that righteousness whereby, through grace and sheer mercy, he justifies us by faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise.

Unlike any work of literature or philosophy, it was Paul’s epistle that compelled Luther to launch what became the Protestant Reformation. He called the letter “the soul’s daily bread,” “the gospel in its purest expression,” and “a brilliant light, almost enough to illumine the whole Bible.” In his seminal treatise, The Freedom of a Christian (1520), Luther contrasted the liberty of the gospel, properly understood, with “the crawling maggots of man-made laws and regulations” imposed upon believers by church authorities. Luther’s teachings about spiritual freedom — what might be called a spiritual bill of rights — became a rallying cry throughout Europe.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the themes of freedom and equality in the Letter to the Romans can be discerned in the beloved hymn, “Amazing Grace,” written by a former slave-ship captain, John Newton; in the social reform efforts of John and Charles Wesley; in the campaign to abolish the slave trade in Great Britain; and in the sermons that shaped the Protestant and democratic culture of colonial America. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, Jonathan Mayhew preached a widely disseminated sermon justifying rebellion against tyranny. His text was Romans, Chapter 13 — Paul’s instruction to believers to submit to political authorities:

Thus, upon a careful review of the apostle’s reasoning in this passage, it appears that his arguments to enforce submission, are of such a nature, as to conclude only in favor of submission to such rulers as he himself describes, i.e., such as rule for the good of society, which is the only end of their institution. Common tyrants, and public oppressors, are not entitled to obedience from their subjects, by virtue of anything here laid down by the inspired apostle.

John Adams, reflecting on the origins of the Revolution years later, cited Mayhew’s sermon as a factor in persuading pious believers of the legitimacy of political resistance. Mayhew may also have persuaded the more secular-minded Ben Franklin, whose proposed motto for the American seal was “rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”

The Letter to the Romans gained renewed prominence in the 20th century after the carnage of the First World War. In his Epistle to the Romans (1918), Swiss theologian Karl Barth shook off his attachment to theological liberalism and its illusions of human progress by meditating on the letter’s key doctrines. “The mighty voice of Paul was new to me,” he wrote, “and if to me, no doubt to many others also.” According to Catholic theologian Karl Adam, Barth’s recovery of the concept of man’s alienation from God and his need of divine grace dropped “like a bombshell on the theologians’ playground.” It is surely no coincidence that Barth was one of the first European theologians to recognize the apostasy of Nazism. He also was the lead author of the Barmen Declaration (1934), the first major ecclesiastical challenge to the racist ideology of the Nazi state.

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. saw many parallels in his own life and that of the Apostle Paul. He used Paul’s Letter to the Romans like a battering ram in his campaign for civil rights. In a 1956 sermon in Montgomery, Ala., plainly modeled on Paul’s epistle, King warned American Christians, in the words of Paul, not to conform “to the pattern of this world,” but rather to recommit themselves to the binding moral and spiritual truths of the gospel:

Don’t worry about persecution America; you are going to have that if you stand up for a great principle. I can say this with some authority, because my life was a continual round of persecutions. . . . I came away from each of these experiences more persuaded than ever before that ‘neither death nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come . . . shall separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.’ I still believe that standing up for the truth of God is the greatest thing in the world.

King’s citation, from Romans, Chapter 8 — about the relentless love of God in the face of great evil — was a spiritual anchor in his long struggle for justice. Like Paul, his sense of vocation led to persecution, imprisonment, and, ultimately, a violent death.

Historians debate Paul’s precise motives for writing his treatise to the Christians in Rome. By virtue of its location in the seat of the Roman Empire, the church at Rome was a thoroughly cosmopolitan congregation: a mix of Jews and Gentiles, rich and poor, citizens and slaves. Paul told the believers that he planned to visit them on his way to Spain. Instead, the apostle found himself under arrest and taken to Rome to await trial. He made good use of his confinement: He wrote four letters to other Christian churches that became part of the New Testament canon. As a Roman citizen, Paul was allowed a measure of freedom, and for two years he “welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance” (Acts 28:30-31).

Eventually, not even Rome’s emperors could resist the gospel message to which Paul devoted his life. As historian Ernle Bradford described it in Paul the Traveler, the apostle never hesitated to hurl himself into the center of the storm: “Rome was always what he sought, the heart of power, the heart of darkness, where he could set fire to the aspirations of millions.” Nearly 2,000 years after Paul’s martyrdom, the hope of freedom and redemption burns steadily in nearly every corner of the world.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

September 14, 2021

National Review: A New Order for the Ages

This article was originally posted at National Review.

This essay series explores Italy’s unique contribution to the rich inheritance of Western civilization, offering a defense of the West’s political and cultural achievements. Find previous installments here, here, and here.

Naples, Italy — At a crisis moment in his life, the epic hero of Virgil’s mythic account of the founding of Rome turns to a woman for counsel. Aeneas, the prince of Troy, had fled the ruins of his city when it fell to the Greeks and arrived in Cumae, west of Naples, anxious and uncertain about his fate. He asks the Sibyl of Cumae, one of the most revered prophets of the ancient world, to guide him in his journey to the underworld. She agrees, but not before delivering a message filled with foreboding:

You have braved the terrors of the sea, though worse remain on land — you Trojans will reach Lavinium’s realm — lift that care from your hearts — but you will rue your arrival. Wars, horrendous wars, and the Tiber foaming with tides of blood, I see it all!

The Aeneid has been described by one scholar as “the single most influential literary work of European civilization for the better part of two millennia.” It is a story about origins, written by Rome’s greatest poet when his nation was in the throes of an identity crisis. The Roman people had discarded their republican form of government in favor of an empire run by autocrats. Virgil, probably prompted by the Emperor Augustus, sought to give Rome a revived sense of its civilizing mission in the world — to somehow reconcile the ideals of the republic with the fearsome realities of the empire.

The encounter at Cumae marks a turning point for Aeneas. “Come, press on with your journey,” says the Sibyl. “See it through, this duty you’ve undertaken.” Aeneas, obedient to the calling on his life, forges ahead.

America’s founding generation absorbed Virgil (70–19 b.c.) and the lessons of Rome. They admired the story of Aeneas, the man who led a tiny group of intrepid refugees across the sea to create a great nation in a hostile world. Like Rome, the American republic would inaugurate a new social and political order. Indeed, the motto on the Great Seal of the United States, a novus ordo seclorum — a new order for the ages — was borrowed fromVirgil’s book of poems, The Eclogues. Unlike Rome, however, this political order would be based on the concepts of human equality and human freedom.

It thus comes as no surprise that the progressive assault on America as a racist and imperialist juggernaut has drawn into its wake a raft of revisionist views of Virgil’s work. Awash in woke assumptions about the West, critics don’t have much to say about some of the key elements of the story, such as virtue, sacrifice, and faith. “Two thousand years after its appearance,” writes Daniel Mendelsohn in The New Yorker, “we still can’t decide if his masterpiece is a regressive celebration of power as a means of political domination or a craftily coded critique of imperial ideology.”

It does not occur to the leftist literati that there are other, legitimate ways of appreciating Virgil’s achievement that avoid these crude tropes. The English classicist Bernard Knox, for example, identified three major virtues on display in the work. All of them, it turns out, are essential for republican government.

There is the concept of auctoritas, the respect that is earned by those who lead and govern wisely and bravely, whether in war or peacetime. It suggests an intangible yet widely acknowledged moral authority. There is the idea of gravitas, a deep seriousness about political and religious matters. It requires maturity, a grasp of the ultimate issues at stake in the contest at hand.

Lastly, there is pietas, which signifies duty and devotion: honoring one’s binding commitments regardless of the personal costs. In the early lines of the poem, Aeneas is called “a man outstanding in his piety.” This quality was immensely significant to C. S. Lewis, the Christian author and scholar of English literature at Oxford University. Lewis regarded the Aeneid, with its emphasis on pietas, as one of the most important influences on his professional life. “It is the nature of a vocation to appear to men in the double character of a duty and a desire, and Virgil does justice to both,” he wrote. “To follow the vocation does not mean happiness: but once it has been heard, there is no happiness for those who do not follow.”

When the American founders wrote that “civic virtue” was essential for republicanism, they had the Roman concept of pietas especially in mind. As Knox explains, the Latin word carries a broad meaning. It includes the idea of piety, of course, or devotion to the Divine. Aeneas “is always mindful of the gods, constant in prayer and thanks and dutiful in sacrifice.” It also involves devotion to family, an outstanding trait in the life of Aeneas. George Washington kept on his mantelpiece a bronze sculpture of Aeneas carrying his father as they escaped from the fires of Troy.

Yet pietas contains another obligation in addition to what is owed the gods and family, a quality that has come under sustained assault in the progressive age of rage: duty to one’s country. For Aeneas, his loyalty is to Rome. His task is not only to wage war and defeat defiant tribes, his supreme mission is nothing less than to establish a new civilization: “Roman, remember by your strength to rule Earth’s peoples — for your arts are to be these: to pacify, to impose the rule of law, to spare the conquered, battle down the proud.”

Aeneas accepts his calling reluctantly, sensing the hazards that lie ahead. When he wavers — as when he falls in love with Dido of Carthage and convinces himself that Carthage, not Rome, can be the new home for the Trojans — he invites disaster. It is only when Aeneas submits unreservedly to the divine calling that he achieves his stature as a great leader. In this, he becomes a model of civic virtue: the individual who chooses the public good over private ambition, who sacrifices himself for the sake of the Roman republic, the res publica.

Virgil helped to make the concept of pietas an ideal for all Romans. His tomb, a place of pilgrimage for centuries, is in Naples, where he owned a villa. It forms the center of a park dedicated to his memory.

When the American founders considered the virtues necessary for self-government, they turned instinctively to Rome. Most of them were trained in the classics. They devoured the works of Cicero, Tacitus, Livy, and Plutarch. They reflected deeply on the inevitable clash between freedom and order, between individual liberty and the will to power. The result was a written constitution that has made possible the most democratic, prosperous, and welcoming society in history.

Today, however, the United States, lacerated by divisions and self-doubt, seems to sit on the edge of a knife. After years of civil war, the Romans looked to Virgil to recover the virtues that helped to establish and sustain their republic. In the end, their political project collapsed into tyranny. Now in the throes of a culture war over the moral legitimacy of our political order, Americans are uncertain where to turn for guidance or inspiration. Rather than pietas, impiety is all the rage.

Words from the Sibyl come to mind: “Man of Troy, the descent to the Underworld is easy. Night and day the gates of shadowy Death stand open wide, but to retrace your steps, to climb back to the upper air — there the struggle, there the labor lies.”

Editor’s note: This article originally stated that the phrase “new order for the ages” came from the Aeneid; it came from Virgil’s Ecologues.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

September 7, 2021

National Review: Cicero: A Republic — If You Can Keep It

This article was originally posted at National Review.

This essay series explores Italy’s unique contribution to the rich inheritance of Western civilization, offering a defense of the West’s political and cultural achievements. Find previous installments here and here.

Formia, Italy — When the American struggle for independence was beginning to look like a fool’s errand, John Adams left for Paris to help Ben Franklin secure a military alliance with the French. His ten-year-old son, the future president John Quincy, was with him when they sailed from Massachusetts in February 1778.

During the journey, Adams helped his son translate a famous address by Cicero in which he accused a Roman senator, Lucius Sergius Catilina, of planning to overthrow Rome’s republican government:

That destruction which you have been long plotting against us ought to have already fallen on your own head. . . .You will go at last where your unbridled and mad desire has been long hurrying you.

More than any other authority from the classical world, the American Founders looked to Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 b.c.), Rome’s greatest statesman, as they sought to design a democratic republic that would not collapse into despotism.

Cicero’s career was a cautionary tale. His decades-long struggle to preserve Rome’s republic — with its “mixed” constitution — ended here, in his seaside villa north of Naples. In 43 b.c., assassins sent by Marc Anthony, his political rival, approached him with swords drawn. “There is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier,” he reportedly told them, “but try to kill me properly.” They cut off his head.

“Cicero came to stand for future generations as a model of defiance against tyranny,” writes Anthony Everitt in Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician. More importantly, the writings of Tully (as his name was Anglicized) were required reading for all educated people in 18th-century Britain and the United States. As a result, writes Everitt, “he became an unknowing architect of constitutions that still govern our lives.”

Cicero’s most important contribution to modern political thought was the concept of mixed government, an idea he got from the Greeks. Plato identified three basic forms of government: monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. In his Politics, Aristotle argued that a combination of the three, in which their powers were balanced, was the best form of government.

Cicero seized upon the concept and made it the centerpiece of The Republic (54–51 b.c.), written just before the outbreak of civil war. No one form of rule should be allowed to dominate the political system, he said, because “each of these governments follows a kind of steep and slippery path which leads to a depraved version of itself.” Rome’s leadership ignored Cicero’s warning, putting an end to him — and to the republic that he idolized.

The Founders knew this history well. They wanted a constitution that could weather the storms of faction, jealousy, and lust for power. As James Madison put the matter in The Federalist Papers (1787–88), the Americans sought “a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government.”

And they seized upon Cicero. In his influential Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States (1787), which circulated at the Constitutional Convention, Adams traced the development of the balanced constitution from Aristotle to Cicero, his hero. “As all the ages of the world have not produced a greater statesman and philosopher united in the same character,” Adams wrote, “his authority should have great weight.”

The Founders also turned to thinkers such as the French philosopher Montesquieu (1689-1755), author of The Spirit of Laws, one of the great works in the history of political thought. Montesquieu famously developed a theory of the separation of powers: legislative, executive, and judicial. “When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates,” he wrote, “there can be no liberty.” Yet, in this, Montesquieu acknowledged his own intellectual debt to Cicero and Rome’s example.

In addition to his politics, Cicero was beloved among the Founders because of his eloquence. Lawyer, senator, consul, philosopher — in each of these roles Cicero honed his reputation as one of Rome’s greatest orators. Fifty-two of his speeches, including his Catiline Orations, delivered to the Roman senate in 63 b.c., have survived. In works such as De Oratore (55 b.c.), Cicero argued that the effective speaker must combine logic and wisdom with the heart of a poet and the instincts of an actor. “Nothing, therefore, is more rarely found among mankind,” he complained, “than a consummate orator.”

The American Revolution produced more than a few. By 1776, there were nine colleges in the colonies, all with essentially the same entry requirements, namely, the ability to read Cicero and Virgil in Latin and the New Testament in Greek. When he applied to King’s College (now Columbia), John Jay had to translate three orations from Cicero. John Adams, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton faced similar requirements for their entrance exams to Harvard, the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), and King’s College, respectively. As president of the College of New Jersey (1765–1792), the Reverend John Witherspoon transformed the school into an academic training ground for statesmen, elevating rhetoric along Ciceronian lines. (Witherspoon named his home Tusculum, after Cicero’s Italian villa.)

Cicero wrote with great insight about the concepts of justice, education, morals, and the character of the ideal statesman. But perhaps his most important contribution to the American political order was his understanding of natural law.

Cicero believed that a rational Providence oversaw the world, a world embedded in divine law: a set of moral and religious truths that govern the human condition. These truths were etched into the mind and conscience of every human being. “The nature of law must be sought in the nature of man,” he wrote in The Laws. “Man is a single species which has a share in divine reason and is bound together by a partnership in justice.”

As Cicero explained it, a political commitment to justice was only possible because of the universal and unchangeable character of natural law. It alone provided “the bond which holds together a community of citizens.” His description of natural law would be embraced by thinkers ranging from Thomas Aquinas to John Locke to Thomas Jefferson:

We cannot be exempted from this law by any decree of the Senate or the people; nor do we need anyone else to expound or explain it. There will not be one such law in Rome and another in Athens, one now and another in the future, but all peoples at all times will be embraced by a single and eternal and unchangeable law; and there will be, as it were, one lord and master of us all—the god who is the author, proposer and interpreter of that law. Whoever refuses to obey it will be turning his back on himself. Because he has denied his nature as a human being he will face the gravest penalties for this alone.

All of the Founders subscribed to some version of natural law; it seemed to confirm the teachings of Christianity, held in high regard in the Protestant culture of colonial America. Thus, most of the Founders had Cicero in mind when they made natural law part of their political discourse. “Although the Founders had access to every level of Western discourse on natural law,” writes historian Carl J. Richard, “they cited Cicero in support of the theory even more than in support of mixed government.”

The great innovation of the advocates of republicanism in the 17th and 18th centuries was to base their arguments for “unalienable” natural rights on a universal natural law. Neither Cicero nor any of the other classical philosophers made this conceptual jump.

In the history of political theory, the most developed and persuasive account of natural rights appears in Locke’s Second Treatise of Government (1689), the document that helped to ignite the American Revolution. It is no accident that Locke absorbed the writings of Cicero and deployed his natural-law concepts for his own revolutionary purposes. Indeed, in explaining the potency of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson confessed thus: “All its authority rests, then, on the harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversation, in letters, in printed essays, or the elementary books of public right, [such] as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, etc.”

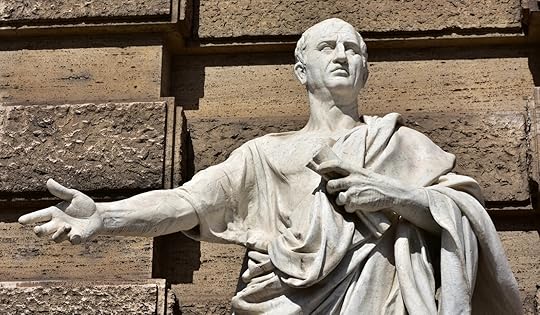

With the ideals of Western Civilization under intense assault, how should we evaluate Cicero’s legacy? The remains of an ancient villa in Formia are said to contain his tomb, an easily overlooked tourist destination. His statue sits majestically in front of the Palace of Justice in Rome, home of Italy’s Supreme Court. That seems fitting. In his political theory and his public career, Cicero embodied an outlook that is essential for a healthy democratic society: an authentic passion for justice. “Nothing can be sweeter than liberty,” he wrote. “Yet if it isn’t equal throughout, it isn’t liberty at all.”

For all his faults and personal ego, Cicero also possessed a quality desperately lacking in our degraded political culture: the willingness to surrender power for the sake of the republic.

In his speech before the Roman Senate, Cicero exposed Catiline’s plot to ignite an insurrection across Italy and seize power. Before he finished speaking, Catiline fled the Senate; he and other leading conspirators were either killed in battle or executed. As consul, Cicero was granted emergency powers. Instead, he walked away from absolute rule and restored the republic. Cicero was awarded the honorary title of Pater Patriae, Father of the Country, the same title given to George Washington, who willingly resigned his military commission and repeatedly declined to serve as king.

“The people that is ruled by a king lacks a great deal,” wrote Cicero, “and above all it lacks liberty, which does not consist in having a just master, but in having none.” Can Americans recover Cicero’s insights into human nature and the nature of political power? Upon the answer to that question hangs the future of this republic.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

August 31, 2021

National Review: Bologna: Birthplace of the University

This article was originally posted at National Review.

This essay series explores Italy’s unique contribution to the rich inheritance of Western civilization, offering a defense of the West’s political and cultural achievements.

Bologna, Italy — The idea of the university, of an institution devoted to freedom of thought in the pursuit of truth, stretches back nearly a millennium. Its origins can be traced here, when a daring and powerful woman invited a famous scholar to teach Roman law to a small group of ambitious young men.

The Countess Matilda, heiress to vast tracts of land in Tuscany and a friend of Pope Gregory VII, was as fervent in her quest for knowledge as in her piety. In 1080, the discovery in an Italian library of texts of Roman law, compiled under Justinian in the sixth century but lost for many years, created a sensation. As historian Harold Berman explains, Europeans viewed Justinian’s law as “the ideal law, the embodiment of reason,” and applicable everywhere. The texts were copied and began to be studied, as students gathered to hire teachers to expound their meaning. A popular and dynamic teacher known as Irnerius caught the attention of Matilda, and in 1088 she arranged to have him teach in her native Bologna.

It marked a quiet yet profound revolution in the history of education. The Bologna students quickly organized themselves into a guild, what they called a universitas, a term from Roman law to describe an association with a legal personality. It was a bottom-up affair: The students paid the salaries of the professors themselves — and penalized them if they were not fulfilling their academic duties. They secured a charter from the city of Bologna that made them responsible for:

The cultivation of fraternal charity, mutual association and amity, the care of the sick and needy, the conduct of funerals and the extirpation of rancor and quarrels, the attendance and escort of our candidates for the doctorate to and from the place of examination, and the spiritual welfare of members.

The school at Bologna eventually drew teachers and students from all over Europe and from other disciplines — medicine, theology, philosophy, the liberal arts — and organized them into an academic profession. This spontaneous experiment marked the birth of the university, the oldest in the world, and the first institution to establish academic requirements and award degrees. The principle of academic freedom had taken root.

Bologna introduced a completely novel approach to education in the West. Before the eleventh century, formal education in Europe occurred almost exclusively in monasteries. In the emerging cathedral schools, education was supervised by ecclesiastical authorities, charged with upholding the doctrinal teachings of the Catholic Church. The desire to ensure orthodoxy intensified as tensions mounted between church and state. They hit a high-water mark during the Papal Revolution, a campaign begun in the eleventh century to preserve the independence and authority of the Church of Rome against the claims of emperors and kings. Thus, there were hard limits on what could be taught or debated, even at Bologna, which was not under church supervision.

Nevertheless, there was a spirit of innovation and freedom at Bologna, where the city and the university collaborated to preserve their independence and advance a common educational vision. The city of Bologna, under the slogan libertas, had sought to escape feudal rule and become a free commune. For the first century of its existence, the university was free to establish its own academic priorities and operated independently of the church. Bolognese jurists could support opposing views about the extent to which Roman law supported papal or imperial claims. Students were encouraged to do the same in a curriculum that included the disputatio, a debate supervised by a professor, a precursor to the modern moot court.

Bologna’s revival of Roman law also set the stage for the compilation and study of canon law, the papal rulings, and other decrees issued through the centuries. This became the lifework of Gratian, another Bolognese scholar. His Decretum offered a comprehensive body of church rulings touching nearly every conceivable realm of human activity. Gratian opened the Decretum with words from the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Ephesians: “For the whole law can be summed up in this one command: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’”

The combination of Roman law and church law put Bologna at the center of a revolution: The Roman ideals of justice would be reframed and reinterpreted by the Christian concept of love. The fundamental understanding of law would be transformed. “No longer did it exist to uphold the differences in status that Roman jurists and Frankish kings alike had always taken for granted,” writes Tom Holland in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. “Instead, its purpose was to provide equal justice to every individual, regardless of rank, or wealth, or lineage — for every individual was equally a child of God.”

The development of a medieval legal tradition, drawing on both civil and canon law, was exported. The greatest professors of the day carried the new outlook across Europe, to schools emerging in Paris, Prague, Vienna, Heidelberg, and Oxford. The foundation for centuries of Western legal thought — the basis for much of English common law and American jurisprudence — was being laid. And at its heart was the concept of equal justice, an innovation nearly as revolutionary as the Sermon on the Mount.

By the end of the twelfth century, the University of Bologna was renowned as the premier center for higher learning in Europe. Students from across the continent were drawn to its culture of truth-seeking. Graduates could teach anywhere, spreading their reputation as La Dotta, the Learned. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I (1122–1190) granted special protection to Bologna’s foreign scholars, ensuring them “freedom of movement and travel for the purposes of study.” As a result, some of the most radical minds of the Middle Ages — including Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca, and Erasmus of Rotterdam — studied at Bologna. A noblewoman named Bettisia Gozzadini, after studying philosophy and law at Bologna in 1237, became the first woman in history to be awarded a university degree and allowed to teach at the university level. Even during the turbulent years of the Protestant Reformation, the university kept its doors open and protected Protestant students from prosecution by the Inquisition.

Today the University of Bologna, with eleven schools and more than 86,000 students, ranks among the top academic institutions in Europe. Its history is intimately bound up with the city of Bologna. In the historic squares, for example, it is not the statues of political or military heroes that dominate — but rather the tombs and memorials to medieval professors. Local churches, as well, pay homage to figures such as Scholastica, founder of the Benedictine nuns and the patron saint of education. It is largely forgotten that the popular term alma mater, used by university graduates around the world, comes from the University of Bologna: Its full name is Alma Mater Studiorum Universita di Bologna, or “the Nourishing Mother of Studies University of Bologna.”

The modern university could use some intellectual nourishment, Bolognese-style. Unlike the contempt for Western civilization that animates much of the academy, the students at Bologna paid homage to their cultural inheritance: the classical-Christian tradition. Unlike the tribalism and grievances that characterize campus culture, Bologna sought to create an academic community devoted to meeting the physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual needs of its members.

The University of Bologna, in author Tom Holland’s words, became “a new nerve-center for the transfiguration of Christian society.” The recovery of its intellectual and spiritual vision is perhaps the most urgent task of our time.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

August 24, 2021

National Review: Pliny’s Problem with Christianity — and Ours

This article was originally posted at National Review.

This essay series explores Italy’s unique contribution to the rich inheritance of Western civilization, offering a defense of the West’s political and cultural achievements.

Como, Italy — In the façade of the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, better known as the Como Cathedral, are statues depicting various saints, the Virgin Mary, and the Archangel Gabriel. Also displayed among them, though, is the figure of a Roman official famous for his role in establishing the empire’s policy of persecution against the Christian church.

Not long after being appointed governor over the province of Bithynia-Pontus, in modern-day Turkey, Pliny the Younger wrote to the Emperor Trajan about the growing problem of a new religious sect known as Christians. He put a series of questions to Trajan about their treatment. He professed to be “unaware what is usually punished or investigated, and to what extent.” The emperor’s response, a blend of brutality and pragmatism, helped to cement imperial policy for the next hundred years.

Pliny’s letter to Trajan, written around 110 A.D., reveals Rome’s attitude toward Christianity at a moment of great cultural and political vulnerability for the church. It also represents an analog of the condescension and hostility of the modern liberal state toward traditional religious belief: a pretense of toleration unable to conceal an appetite for repression.

The founder of Christianity, of course, had run afoul of Rome’s political establishment: Jesus of Nazareth was crucified, in part, for rejecting Caesar’s claims to absolute authority. His earliest followers did likewise, insisting that they would worship Jesus alone as God, proclaim his message of salvation, and bear witness to his resurrection — regardless of Roman law. Their stirring note of defiance is recorded in the New Testament book of Acts: “We must obey God, rather than men.” Confrontation with Rome was inevitable.

Although there were occasional bursts of intense persecution in the first several decades of the life of the church — such as under the Emperor Nero following the Great Fire in 64 A.D. — there was no systematic policy. Rome initially regarded the Christians as a sect of Judaism, which enjoyed limited toleration.

By the time Pliny became governor, however, the status of the Christians had changed. They were viewed as members of a breakaway sect — and they were on the move, winning converts throughout the empire. “For the matter seemed to me to warrant consulting you, especially because of the number involved,” wrote Pliny. “For many persons of every age, every rank, and also of both sexes are and will be endangered. For the contagion of this superstition has spread not only to the cities but also to the villages and farms.”

Pliny held the establishment view that Rome’s glorious history, her mission to civilize and dominate the world, was sanctified by the imperial religion. The ancestral gods, it was believed, had ordained Rome’s transformation from a small city-state in Italy to a world empire. As Pliny expressed it elsewhere in his correspondence, the emperor uniquely embodied the compact between the gods and the people of Rome. “We have celebrated with due piety the day on which the guardianship of the human race was passed to you in most blessed succession,” Pliny wrote. “We commended to the gods, from whom you derive your rule, both our public vows and our joys.”

State religion, rule by divine right, priests as agents of government — in all of this, Rome followed the pattern of the ancient world. The Christians uniquely threatened the established order of things, inviting the displeasure of the gods. Thus, to refuse to worship the approved deities amounted to an act of sedition. “As an apologist for the traditional religion,” writes historian P. G. Walsh, “Pliny reacted with dismay to the remarkable rise of Christianity in the province of Bithynia.”

Prior to writing the emperor, Pliny had adopted an ad hoc policy toward those brought before him and identified as Christians:

I asked them whether they were Christians. If they admitted it, I asked them a second and a third time, threatening them with execution. Those who remained obdurate I ordered to be executed, for I was in no doubt, whatever it was which they were confessing, that their obstinacy and their inflexible stubbornness should at any rate be punished.

Thus, the justification for putting Christians to death was not for any criminal activity but for refusing to submit fully to the authority of Rome in matters of religion. Although many historians underscore Rome’s policy of accommodating a variety of beliefs, there were no protections for the rights of individual conscience when it clashed with the state.

Pliny investigated for himself the activities of the Christians in his province, apparently because he took seriously his charge to govern. “But I chose you for your practical wisdom,” Trajan wrote to him, “so that you would . . . establish the norms which would be good for the enduring peacefulness of the province.” What he discovered must have challenged some of his assumptions. The Christians met at dawn on a fixed day of the week, sang a hymn to Christ as God, and bound themselves with an oath, “not for the commission of some crime,” but to avoid theft, adultery, greed, and other vices.

Perhaps this explains Pliny’s uncertainty about imperial policy. What exactly were the criminal offenses of the Christians, and how should they be punished? “I am more than a little in doubt . . . whether it is the name Christian, itself untainted with crimes, or the crimes which cling to the name which should be punished.”

In response, Trajan announced what some consider a measured, even tolerant policy. The Christians were not to be hunted down as if they were insurrectionists in waiting. “Christians are not to be sought out,” he wrote. If they were brought to the attention of the authorities, they could renounce their faith without penalty “by worshipping our gods.” In addition, Trajan definitively rejected accusations from anonymous sources: “Documents published anonymously must play no role, in any accusation, for they give the worst example, and are foreign to our age.” The emperor was keenly aware of how personal vendettas, through anonymous sources, could destroy a person’s reputation. (It is worth noting that, on this point, Rome took a more ethical position than do modern newspapers such as the New York Times and the Washington Post.)

Nevertheless, the brutal fact remains: Rome made the execution of “unrepentant” Christians — those who refused to renounce their faith in Christ — a legal norm. Trajan wrote that “no general rule can be laid down” to govern the treatment of Christians, but he then proceeded to do precisely that. “If brought before you and found guilty, they must be punished.” The emperor’s answer to Pliny’s original question is clear: To merely call oneself a Christian was enough to be sent to the lions.

It is sobering to remember that neither the emperor nor his hand-picked governor was considered brutal or inhumane by the standards of the day. Throughout antiquity, the principate of Trajan (98–117 A.D.) was regarded as a golden age, a return to the representative role of the Senate. Pliny’s letters are filled with practical concerns: A colony needs an aqueduct to “contribute to the health and pleasure of the city.” Another colony needs economic aid “to relive the poverty of those in greater need.”

Nevertheless, the social and psychological divide between Rome’s ruling elite and its ordinary citizens was immense. Pliny was one of the most prominent aristocrats of his generation. He owned several magnificent villas and threw elaborate dinner parties. As he explained to a friend, one of his villas in Bellagio, Italy, sat so close to Lake Como that “you can yourself fish, casting your line from your bedroom and virtually even from your bed, as though from a small boat.” Modern political dinner parties at Cape Cod, Mass., and the Hamptons on Long Island come to mind.

One of the lessons of Rome is that the life of extreme privilege weakens the capacity for empathy, which makes persecution of outsiders more plausible. We need not exaggerate the modern hostility to professed Christians and other religious believers in the United States who challenge established orthodoxies. Nevertheless, the deepening secularization of American public life is putting many religious believers at odds with some of its most powerful institutions. Today’s elites embrace the latest ideological fads — from critical race theory to gender-reassignment surgery — as though they were substitute faiths. Backed by the coercive power of government, they would search out, punish, and silence dissent.

The American Founders took a different view of the rights of conscience. For them, no political regime could invade the sacred realm of belief between the individual and her Creator. James Madison made religious freedom the linchpin of constitutional government: the moral and philosophical basis for the freedoms protected by the Bill of Rights. “It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him,” Madison wrote. This obligation, he explained, preceded the claims of civil government. “Before any man can be considered as a member of Civil Society, he must be considered as a subject of the Governor of the Universe.”

Madison knew his Bible. The Christians who confounded Pliny, who defied the political establishment, who faced death rather than bow to the idols of their age, embraced a profound imperative from their Teacher and Lord: “Render to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and render to God what belongs to God.” Rome trampled this concept underfoot, accelerating its own corruption and disintegration — a lesson the Founders never forgot.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

July 15, 2021

National Review: 1776: A Lockean Revolution

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Ten years before the American Revolution, Charles Pratt, the chief justice of Common Pleas in Great Britain, took to the floor of the House of Lords to argue that members of the British Parliament “have no right to tax the Americans.”

Although the government had repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766, it immediately proposed the Declaratory Act, which insisted that Parliament had “full power and authority” to pass laws binding on the colonies. Pratt, also known as Lord Camden, saw a backhanded attempt to violate the “fundamental laws” of nature and of the English constitution by continuing to deny Americans representation in Parliament. At the heart of his argument was the political thought of one of Britain’s most celebrated philosophers: John Locke.

“So true are the words of that consummate reasoner and politician Mr. Locke,” Camden said. “I before have alluded to his book. I have again consulted him; and finding what he writes so applicable to the subject in hand, and so much in favor of my sentiments, I beg your lordships’ leave to read a little of this book.”

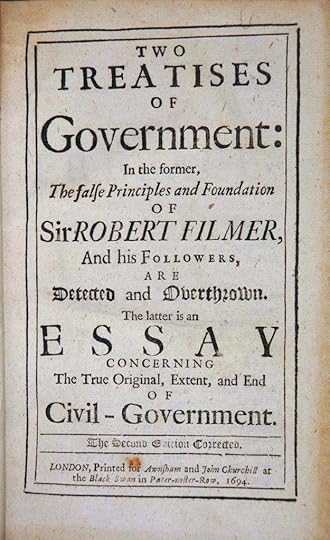

The book in question was Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1689), the political tract that demolished the case for absolute monarchy and helped to set colonial hearts on fire. Indeed, the American Revolution was a Lockean Revolution: The Americans declared, for the first time, that a nation was coming into existence based upon a belief in human equality, freedom, and universal rights. Upon this foundation alone could government by consent be sustained. Wrote Locke: “The supreme power cannot take from any man, any part of his property, without his own consent.”

Camden spoke for nearly an hour and, although there is no transcript of his speech, he apparently quoted extensively from Locke’s Second Treatise. It is a good bet he made use of Locke’s ability to employ a grammar of natural rights grounded in biblical revelation. Unlike Thomas Hobbes, for example, Locke’s “state of nature” was framed by a moral order whose origin was the Divine will.

The state of Nature has a law of Nature to govern it, which obliges everyone, and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions; for men being all the workmanship of one omnipotent and infinitely wise Maker; all the servants of one sovereign Master, sent into the world by His order and about His business; they are His property…

Locke’s modern interpreters — from both the secular left and the religious right — often appear ignorant of his scriptural references. But American readers in the 18th century would have recognized lines from Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, describing men and women as the handiwork of God: “For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them.” Locke based his entire approach to politics on an anthropology — a view of human nature — that drew its authority from the Bible, a book that most colonial Americans revered.

The governing authorities, Locke reasoned, must respect God’s relationship with the people he has created: They are “His property,” having been sent into the world “by His order.” Political absolutism, he wrote, robs God of His divine prerogative.

Thus, after “a long train of abuses,” when political rulers make their “design visible” for all to see, they “put themselves into a state of war with the people.” Whenever that happens, Locke warned, “it is not to be wondered that they should then rouse themselves, and endeavor to put the rule into such hands which may secure to them the ends for which government was first erected.”

The American revolutionaries found in this English theorist a political-theological ally. Governments preserve their legitimacy only by fulfilling the purpose for which they were instituted: the protection of our God-given rights and freedoms. To ignore these “self-evident” truths is to open the door to slavery and despotism — and revolution. As the Americans expressed it in their Declaration:

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security…

Why was Locke so influential in the American struggle for independence? No political author was cited more frequently. Ministers quoted him as enthusiastically as politicians: Samuel Cooper praised his “immortal writings”; Elisha Williams called him “the great Mr. Locke.” Even if Locke’s works were not explicitly mentioned, his rhetorical defense of human freedom, equality, and government by consent had permeated the thought of colonial America. In his groundbreaking book Locke: Two Treatises of Government (1960), Peter Laslett wrote that Locke established a set of principles for liberty and equality “more effective and persuasive than any before written in the English language.”

In his address to Parliament, Camden recognized Locke’s achievement with words that surely incensed his colleagues. In his “inestimable treatise,” he said, Locke had proved that “the people are justified in resistance to tyranny; whether it be tyranny assumed by a monarch, or power arbitrarily unjust, attempted by a legislature.” No wonder Camden’s speech was reprinted in numerous American newspapers and cited regularly in the pamphlet press.

The American Revolution is usually considered a radical event in political history, and it was. But it also exhibited a conservatism that is often neglected. In rebelling against their colonial masters, the Americans claimed their “chartered rights” as Englishmen and invoked a natural-rights tradition that Locke articulated with compelling power. “His principles are drawn from the heart of our constitution,” Camden explained, and formed the bedrock of England’s Glorious Revolution a century earlier. “I know not to what, under providence, the Revolution and its happy effects, are more owing, than to the principles of government laid down by Mr. Locke.”

Those principles — for which Locke became a fugitive and risked his life — included government by consent, the separation of powers, equal justice, and religious freedom. This English philosopher thus had a hand in two of the greatest political revolutions for human freedom in world history. That’s a legacy worth recalling this July 4.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

June 8, 2021

National Review: Anti-Semitism Is an Attack on American Principles

This article was originally posted at National Review.

The renowned British historian Paul Johnson has called anti-Semitism “a disease of the mind.” There seems to be no permanent cure for this disease. It has flared up again, not just in the usual international settings — in the United Nations General Assembly, for example — but much closer to home.

During the first week of the Israel–Hamas conflict, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) received 193 reports of anti-Semitic incidents in the United States. Two weeks ago, Jews were attacked by gangs in New York City and Los Angeles, and synagogues were vandalized in Skokie, Tucson, and Salt Lake City.

Attacks on Jews, however, began long before the most recent clash between Israel and the Islamist terrorist organization of Hamas. In 2019, the ADL recorded more than 2,100 anti-Semitic acts, the highest number in the 40-year history of the organization’s report. The murderous rampages in synagogues in California and Pittsburgh, a shooting at a kosher grocery store in Jersey City, the arson at the Portland Chabad Center for Jewish Life, the stabbing at the rabbi’s home during Chanukah in Monsey, N.Y., and brutal assaults on Hasidic men in Brooklyn — such incidents are no longer a rare occurrence.

Anti-Semitism is more than a hate crime. It represents a unique assault on America’s founding principles of equality and freedom. Despite the manifest violation of these principles from the start of the American experiment — the existence of slavery and the treatment of Native Americans — the United States created a civic culture that would regard Jews as equal citizens. Outside of Israel, America would become the most welcoming home to Jews of any nation in the world.

America’s journey toward religious pluralism stretches back to its early days. When the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam fell to the English in 1664 and became New York, Jews were granted all the rights of English citizenship “so long as they demean themselves peaceably and quietly.” New York governor Edmund Andros made a special effort to include Jews when he guaranteed equal treatment to all law-abiding persons “of what religion soever.” With regard to their civil rights, their Jewish identity was a nonissue; Jews voted in elections and held public office.

The Revolution of 1776 signaled to the world that a nation was coming into existence predicated upon the natural and inalienable rights of mankind — rights that could not be taken away because they were the endowment of a Creator, not the largesse of the state. The Constitution enshrined these rights in a political system of limited, republican government.

Religious freedom, considered the “first freedom” by the American Founders, was the linchpin. America has never had a national church: The government is prohibited from establishing or favoring any religion over another. The First Amendment guarantees religious liberty to people of all faiths, while the Constitution proclaims that “no religious Test shall ever be required” as a qualification for public office. State constitutions ultimately embraced these principles of religious freedom and equal justice.

The result, for Jews and all other minority faiths, was transformative. As nowhere else in the world, Jews were free to worship God according to the demands of their faith and conscience. They were also free to dissent from the religious views of the majority without fear of persecution. We call this American exceptionalism, an approach to political life — a fundamental respect for the spiritual commitments of all its citizens — that gives everyone a stake in the nation’s success.

The warm letters exchanged in 1790 between George Washington and a Jewish congregation in Newport, R.I., bear eloquent testimony to America as a safe harbor for religious pluralism. “May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in the land continue to merit and enjoy the goodwill of the other inhabitants,” Washington wrote. “While everyone shall sit safely under his own vine and fig-tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.” The leadership of Jeshuat Israel did not withhold their gratitude: “We now . . . behold a Government which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance — but generously affording to All liberty of conscience, and immunities of citizenship — deeming everyone, of whatever nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental machine.”

Washington, always conscious of the example he set as the first president of the United States, knew exactly what he was doing. It is hard to think of another major political leader at the time, in any other government in the world, expressing such a hopeful and inclusive message to his nation’s Jewish inhabitants.

Not everyone in America, of course, shared this generous outlook toward the Jews; prejudice persisted, especially during new waves of immigration. Yet, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed during his 1830s tour, the United States established a civil society that was diverse, tolerant, and deeply religious — a combination that rarely appeared in Europe or other parts of the world. “Among us, I had seen the spirit of religion and the spirit of freedom almost always move in contrary directions,” he wrote in Democracy in America. “Here I found them united intimately with on another: they reigned together on the same soil.”

Unlike in Europe, Jews in America never experienced systematic persecution. They had no reason to isolate themselves or create distinct legal systems. They were welcomed as equal citizens of a self-governing republic. “Since all religious groups had virtually equal rights, there was no point in any constituting itself into a separate community,” writes Paul Johnson in A History of the Jews. “All could participate in a common society.” “Thus, for the first time, Jews, without in any way renouncing their religion, began to achieve integration.”

Another reason for America’s warm embrace of the Jewish people must not be overlooked: the influence of the Bible. The earliest Puritan settlers established a “covenant” with one another modeled on the covenantal theology of the Hebrew Bible. Explains Gabriel Sivan in The Bible and Civilization: “No Christian community in history identified more with the People of the Book than did the early settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who believed their own lives to be a literal reenactment of the Biblical drama of the Hebrew nation.” Likewise, colonial ministers during the Revolution compared the battle for independence with the biblical story of Exodus: how the Jews escaped the slavery of an Egyptian tyrant and found freedom in the Promised Land. The inscription on the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, of course, is taken from Leviticus 25:10: “Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

Thanks to the impact of Protestantism, many Americans were intimately familiar with the Bible. Indeed, next to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the Bible became a third founding document for colonial Americans. According to the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, the chief rabbi of Great Britain, the “self-evident” truths of the Declaration — that “all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights” — were anything but self-evident. “They would have been unintelligible to Plato, to Aristotle, or to every hierarchical society the world has ever known,” he wrote. “They are self-evident only to people, to Jews and Christians, who have internalized the Hebrew Bible.”

American Christians of all denominations recognized in Judaism one of the great gifts to Western civilization: the concept of a moral law given to mankind by a divine Lawgiver. From their very beginnings as a nation — like no one else in the ancient world — the Jewish people sought to order their social, political, and religious life according to these norms. The Ten Commandments supplied the ethical bedrock not only for Judaism but also — quite remarkably — for Western civilization throughout the centuries.

The American Founders were acutely aware of this cultural inheritance and its importance to their new republic. They paid homage to it in countless ways, not least of which was in the physical architecture of their most important political institutions. It is almost impossible, for example, to ignore the carved image of Moses — deliverer of the Ten Commandments to the Jewish people — dominating the frieze atop the U.S. Supreme Court. As James Madison explained: “We have staked the whole of our political institutions upon the capacity of mankind for self-government, upon the capacity of each and all of us to govern ourselves, to control ourselves, to sustain ourselves according to the Ten Commandments of God.”

The unique contributions of the Jewish people to American political and cultural life may help explain the rise in anti-Semitism. Although white nationalism, draped in Christian symbolism, is a problem, the much greater threat comes from the secular Left. Political and cultural antagonism to Jews — in politics, entertainment, and mainstream media — is the product of a thoroughgoing materialism.

What does an increasingly secular and materialistic society have to do with anti-Semitism? If there is a single feature uniting the disparate elements of the Left, it is their rejection of moral truths, rooted in the divine will. The Jews, like no one else, delivered these truths to the world: an example of Jewish exceptionalism. Thus, the Jews stand in the way of the Left’s rage against transcendent truth, against the achievements of the West, against the claims of American exceptionalism.

If this is so, then the answer to anti-Semitism (a partial answer, to be sure) is the reassertion of America’s first principles: the recovery of our historic commitment to the God-given worth and dignity of every human soul.

This was precisely the response of Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, when he encountered an outburst of anti-Semitism among his generals. General Ulysses S. Grant issued an order to banish Jews “as a class” from his war zone. At Holly Springs, Miss., a Union Army supply depot, Jews were rounded up and forced out of the city on foot. A Jewish delegation, led by Cesar Kaskel, arrived at the White House to contest the order.

Lincoln: And, so, the children of Israel were driven from the happy land of Canaan?

Kaskel: Yes, and that is why we have come unto Father Abraham’s bosom, seeking protection.

Lincoln: And this protection they shall have at once.

Lincoln immediately countermanded Grant’s order. (Grant would regret the order and overcome his prejudice.) This is what America’s great leaders do in the face of prejudice and injustice: They return to first principles, to the ideals of justice and equality embedded in the Declaration and the Constitution. If there is a remedy to the disease of anti-Semitism, it begins here.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

April 7, 2021

National Review: How C. S. Lewis Accepted Christianity

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Shortly before he was admitted to Oxford University in 1916 to study English literature, C. S. Lewis, a recent convert to atheism, got into an argument with a friend about Christianity and its supernatural elements. His letters on the topic during this period reveal the spirit of the age: a disposition against religious belief. It has found many allies over the last century.

Lewis chided his friend for not accepting “the recognized scientific account of the growth of religions.” The miraculous stories of the life of Jesus were “on exactly the same footing” as that of Adonis, Dionysius, Isis, and Loki. All religion, he wrote, was an attempt by primitive man to cope with the terrors of the natural world. Just so with Christianity: The story of the resurrection was a sublime retelling of ancient pagan myths about gods and goddesses who, by initiating the cycle of the seasons, represented the pattern of death and rebirth.

By the beginning of the 20th century, it seemed that science had consigned the doctrine of the resurrection to the realm of wish fulfillment. The new discipline of psychology would do much the same. Sigmund Freud, the creator of psychoanalysis, viewed religious feeling as an expression of the childhood need for a father’s protection. “The origin of the religious attitude can be traced back in clear outlines as far as the feeling of infantile helplessness,” Freud wrote in Civilization and Its Discontents. “There may be something further behind that, but for the present it is wrapped in obscurity.”

Lewis was perfectly in step with the newly established zeitgeist, which regarded religion as inherently irrational and repressive. “Superstition of course in every age has held the common people,” he wrote, “but in every age the educated and thinking ones have stood outside it.” Mysteries about the universe remained to be uncovered, he conceded, but “in the meantime I am not going to go back to the bondage of believing in any old (and already decaying) superstition.”

Fifteen years later, however, Lewis — by then an Oxford scholar in English literature — abandoned his atheism and embraced historic Christianity. He went on to become the 20th century’s most celebrated Christian author. His works of apologetics, such as Mere Christianity and The Problem of Pain, have never gone out of print. His children’s series, The Chronicles of Narnia, awash in biblical imagery, has been translated into more than 47 languages.

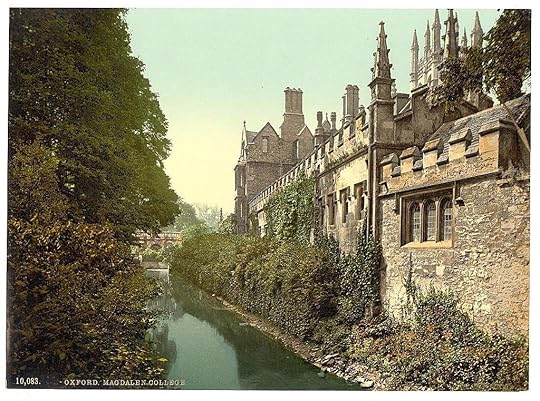

Ironically, it was an argument over mythology — about the meaning of myth in human experience — that brought Lewis around. On September 19, 1931, in what might rank as one of the most important conversations in literary history, Lewis took his friend and colleague J. R. R. Tolkien on a walk along the River Cherwell near Magdalen College. A professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, Tolkien had been studying ancient and medieval mythologies for decades; he had begun writing his own epic mythology about Middle-earth while he was a soldier in France during World War I.

As Lewis recounted the conversation in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, Tolkien insisted that myths were not falsehoods but rather intimations of a concrete, spiritual reality. “Jack, when you meet a god sacrificing himself in a pagan story, you like it very much. You are mysteriously moved by it,” Tolkien said. Lewis agreed: Tales of sacrifice and heroism stirred up within him a sense of longing — but not when he encountered them in the gospels.

The pagan stories, Tolkien insisted, are God expressing himself through the minds of poets: They are “splintered fragments” of a much greater story. The account of Christ and his death and resurrection is a kind of myth, he explained. It works on our imagination in much the same way as other myths, with this difference: It really happened. Perhaps only Tolkien, with his immense intelligence and creativity, could have persuaded Lewis that his reason and imagination might become allies in the act of faith.

Lewis’s objections melted away, like ants into a furnace. “The old myth of the Dying God, without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history,” he wrote after his conversion. “We must not be ashamed of the mythical radiance resting on our theology.”

The modern mind, buttressed by science and psychology, seems either ashamed or baffled by this radiance. Even many church pulpits have transformed the historic teaching of the resurrection into a homey metaphor of springtime renewal: an unwitting nod to pagan religion.

Yet herein lies the startling, nonnegotiable claim of the Christian faith, the event that turned a disillusioned band of followers into the most resilient and transformative religious community in history. At its heart, it is the story of the God of love on a rescue mission for mankind: Christ has died, Christ is risen. Once introduced into the world, the hope of the resurrection became the axis upon which Western civilization turns.

For believers from every corner of the globe, the truth about the human story — what once seemed “wrapped in obscurity” — was revealed in a shattering gleam of light on Easter morning: Myth became fact.

—

Joseph Loconte is the director of the Simon Center for American Studies at the Heritage Foundation and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West. His most recent book is the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com

March 23, 2021

National Review: An American Defense of Britain’s Constitutional Monarchy

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Historians may puzzle for many years over why a rambling, emotional interview between members of the British royal family and an American media tycoon-cum-billionaire became a rallying cry to destroy the British monarchy.

But so it has: The radical Left has seized upon Oprah Winfrey’s televised spectacle with Prince Harry and Meghan, Duchess of Sussex in a crusade to invalidate one of the most consequential conservative institutions on the world stage.

Accusations of racism within the royal family are not the point. The aim of modern liberalism can be symbolically discerned in William Walcutt’s painting, Pulling Down the Statue of George III at Bowling Green, July 9, 1776. It is to tear down everything the monarchy represents: tradition, authority, virtue, duty, love of country, and biblical religion.

The Left’s demolition campaign has a better chance of succeeding today, thanks to the stupefying ignorance of the history of Britain’s constitutional monarchy, which afflicts even the most highly educated. Now is a ripe time to refresh our memories of the monarchy — and recall the debt which Americans owe to the political ideals and institutions it helped to create.

Britain’s monarchy stretches back over 1,000 years, even before the Norman Conquest of 1066. Although Britain has flirted with absolute monarchy — in which the powers of the king or queen are virtually unlimited — the English have always returned to constitutionalism. The signing of the Magna Carta (1215) was one of the great hinges of political history. The monarchy agreed that no political leader was above the rule of law. The monarchy asserted the principles of due process and trial by jury.

No other political system at that time, anywhere in the world, upheld these basic concepts of justice. Foundational to the American constitutional order, they still have no place in many parts of the world today.

When King Charles I tried to rule without Parliament, he set off a constitutional crisis. Although there were other issues in play, the English Civil War (1642–1651) was an existential struggle between political absolutism and constitutionalism. In the end, Thomas Hobbes and his Leviathan lost the argument. In the decades that followed, England became the epicenter of the most important debates occurring anywhere over mankind’s inalienable rights: freedom of speech, of the press, of the right to assemble, and the right to worship God according to the dictates of conscience. All of these rights, of course, would be exported to the American colonists and enshrined in their state constitutions.

The British monarchy, despite its often-contentious relationship with Parliament, became an indispensable ally in the struggle for self-government: The Glorious Revolution (1688–89) marked another milestone in constitutionalism.

To most Britons, William of Orange was not an invader. The real invader was James II who, after ascending the throne, trampled the ancient English constitution underfoot. The new monarchs, William and Mary, came to restore it. They committed themselves — as Protestant rulers, submissive to the authority of the God of the Bible — to obey the laws of Parliament. They agreed to limit their own powers and defend the principle of government by consent of the governed. And they endorsed the English Bill of Rights, which is considered the model for the American Bill of Rights.

The new monarchs stood reverently as Parliament read out its terms for governance:

That the pretended power of suspending of laws or the execution of laws by regal authority without consent of Parliament is illegal. That Elections of Members of Parliament ought to be free. That the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament.

John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1689), his revolutionary defense of government by consent, was vindicated in this remarkable political and cultural moment. These and other documents, legitimized and enforced by the British Crown, laid a new foundation in the West for individual rights and constitutional government. Together, they shaped the fundamental laws of the North American colonies.

Thus, a century before the Americans launched a revolution to reclaim their “chartered rights” as Englishmen, England’s monarchs had decisively rejected political absolutism. They presided over a culture of common law, rooted in a belief in mankind’s “natural and inalienable” rights. In this way, they helped the West to reimagine the core purpose of government: to secure these God-given rights and freedoms for all citizens of the commonwealth.

The impact of all this on the American Founders was profound — not only on the concepts embedded in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights, but also on the very structure of the Constitution itself. As the Founders designed the separation of powers, for example, they turned to Montesquieu, the French theorist who prized the English example. “He was an ardent admirer of the English constitution,” wrote Russell Kirk in The Roots of American Order. “He finds the best government of his age in the constitutional monarchy of England, where the subject enjoyed personal and civic freedom.”