Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 14

August 24, 2016

Providence: Syria’s White Helmets

This article was originally posted at Providence.

“People are dying,” explains Mahmoud Fadlallah, “and we run toward death.”

This is the ethos of the 3,000-strong Syrian Civil Defense, which conducts search-and-rescue missions in war-torn Syria. Known as “the White Helmets” for their signature headgear, they have saved thousands of Syrians, mostly civilians, since the onset of the civil war. Last week their volunteers helped to rescue five-year-old Omran Daqneesh from the rubble of an apartment building in Aleppo: the image of a small boy, covered in dust and blood and sitting alone in an ambulance went viral, and has reignited debate over U.S. policy in Syria.

“Leadership is not only about deciding what is specifically best for you; it’s also about visualizing the result and using all the tools available to push in that direction with friends and opponents,” writes W. Robert Pearson, former U.S. Ambassador to Turkey. “Events over the last three years may offer us a cautionary tale on the consequences of what happens after nothing happens.”

What has happened in Syria is what usually happens when a violent and ruthless dictator commits war crimes against a civilian population with impunity: a cascade of human suffering, starvation, dislocation, and death.

On Aug. 21, 2013, the government of Bashar al-Assad murdered more than 1,400 Syrians—including several hundred children—in a nerve gas attack. It was a war crime, and more crimes like it would follow. President Obama promised a military strike against Assad if he used chemical weapons, but backed down after Assad pledged to give them up. The U.N. Security Council has passed several resolutions forbidding the use of barrel bombs and chemical weapons, but has failed to punish the regime for ignoring them. Earlier this month, a group of 29 physicians sent a letter to President Obama pleading for a no-fly zone in the rebel-held portion of Aleppo to protect roughly 250,000 civilians from airstrikes. Similar appeals have been made to the Security Council. All have been ignored.

The paralysis of the “international community” stands in stunning contrast to the activism of ordinary—though extraordinarily brave—Syrians under fire.

The White Helmets arose from a network of citizen volunteers—pharmacists, bakers, carpenters, engineers, students and others—who refused to flee or remain in hiding as their neighborhoods came under assault. Now operating in 119 centers across Syria, they have become the first responders in rebel-held areas bombarded by the regime. They dig people out of collapsed buildings, often with their bare hands, and provide medical assistance and emergency shelter in areas where public services no longer function. Although the number cannot be confirmed, group director Raed Al Saleh estimates that his volunteers have saved 60,000 lives. Earlier this month the organization was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Make no mistake: operating in areas decimated by government airstrikes, rebel resistance, and Islamic State forces, the White Helmets are engaged in what has been called “the most dangerous job in the world.” Many have paid the ultimate price: At least 130 have been killed while trying to rescue others. “When I want to save someone’s life,” says one volunteer, “I don’t care if he’s an enemy or a friend. What concerns me is the soul that might die.”

These facts—the moral seriousness and quiet valor of everyday Syrians—have been ignored during a presidential election year blackened by nativism and anti-Islamic tirades. In the morally debased culture of American politics, it is now necessary to point out that the vast majority of White Helmet volunteers are believing Muslims. They cite the Quran as inspiration for their work. As Fadlallah recently told the Associated Press: “God watches over us.”

Many no doubt find great comfort in that belief. Yet the suffering of the Syrian people continues, unabated, while others avert their eyes or grasp at a “diplomatic solution” that merely rewards the forces of barbarism. “Our unarmed and neutral rescue workers have saved more than 60,000 people from the attacks in Syria, but there are many we cannot reach,” White Helmet director Saleh explains. “There are children trapped in rubble we cannot hear.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

August 10, 2016

Providence: Churchill, FDR, and the Atlantic Charter

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Nearly two years after the start of the Second World War—with most of continental Europe under German occupation—Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill held their first wartime meeting. From Aug. 9-10, 1941 at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, the two titanic leaders in the West agreed to find common cause in the struggle against Nazism.

As the Prince of Wales dropped anchor, one of Churchill’s aides remarked that his meeting with Roosevelt would make history. “Yes,” replied Churchill, “and more so if I get what I want from him.” What Churchill wanted was a U.S. declaration of war against Germany and a firm warning to Japan against taking aggressive action in the Pacific.

He would be disappointed. Despite two years of Nazi triumphs in Europe, despite Japanese belligerence and savagery in Asia, despite Britain’s existential struggle during the London Blitz, Americans remained in an isolationist mood. Public opinion polls revealed that 75 percent of American adults opposed going to war against Germany. Roosevelt—perhaps the most poll-driven president in American history—had done almost nothing to prepare the American people for the inevitable. Thus FDR told Churchill that he could not formally declare war at this moment. “I may never declare war,” he said.

Instead, Roosevelt agreed to a softer declaration: a general statement of war aims. Like his political hero, Woodrow Wilson, Roosevelt liked lofty proclamations of universal principles. Desperate to commit the United States to the war in Europe, Churchill helped in drafting the document. The result was the Atlantic Charter, a joint declaration of Anglo-American objectives.

The historic eight-point document asserted political and economic principles that would shape the post-war era. Importantly, the charter drew upon the shared liberal political tradition between the United States and Great Britain. Article 3, for example, captures the Lockean concept of government by consent of the governed: “They respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them.”

Churchill naturally interpreted this as being directed to those nations that had fallen under Nazi rule. But FDR, a staunch anti-colonialist, had a broader audience in mind: Britain’s colonial claims in Africa and India. Ironically, FDR’s repugnance for colonialism did not prevent him from scrapping the principle when it was time to negotiate with Stalin’s Russia over the fate of Eastern Europe.

Article 8 of the Atlantic Charter seems lifted from the Wilsonian playbook for establishing world peace:

They believe that all of the nations of the world, for realistic as well as spiritual reasons must come to the abandonment of the use of force. Since no future peace can be maintained if land, sea or air armaments continue to be employed by nations which threaten, or may threaten, aggression outside of their frontiers, they believe, pending the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential.

As biographer William Manchester explains, Churchill, ever the moral realist, went along with the language about disarmament in order secure a U.S. commitment to participate in a “permanent system of general security.” Since most Americans wanted nothing to do with an international coalition, this proved to be a key concession. Perhaps overstating its significance, Churchill called it “a plain and bold intimation that after the war the United States would join with us in policing the world.”

The most poignant moment of the Atlantic conference occurred on Sunday, August 10, when Roosevelt, his staff, and several hundred American sailors boarded the Prince of Wales to join their British counterparts in a worship service. Churchill understood something profoundly important about the power of Christian faith to unite people in moments of crisis. He was not ashamed to draw on the common Protestant heritage of Great Britain and the United States. Churchill designed every detail of the service, choosing the hymns himself. One of his favorites was “O God Our Help in Ages Past,” an Isaac Watts rendition of Psalm 90.

O God, our help in ages past,

our hope for years to come,

our shelter from the stormy blast,

and our eternal home.

It was a remarkable moment: as the Nazi war machine continued its deathly rampage in Europe, seemingly unstoppable, the fighting men of the world’s most powerful democracies, along with their political leaders, gathered to sing a hymn of praise to the God of the Bible. Writing in his memoirs, Churchill marked its significance. “It was a great hour to live,” he wrote. “Nearly half of those who sang were soon to die.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

August 5, 2016

Providence: Turkey’s Democratic Debt to NATO

This article was originally posted at Providence.

Four years ago, in celebrating the 60th anniversary of Turkey’s membership in the NATO alliance, Secretary General Anders Rasmussen offered unstinted praise. Turkey, he said, “has shown its commitment to stability, security, and solidarity time and time again.” He praised Ankara’s “steadfast commitment” to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan battling the Taliban. And he declared “a new era of cooperation between NATO, Turkey, and countries in the region.”

The “new era,” in fact, ended almost as soon as it allegedly began. Today the relationship of Turkey to NATO and the West is edging toward the brink of collapse: caught up in a miasma of Islamic radicalism, power-grabbing, and blunderingly naïve foreign policy.

The July 15 coup attempt against the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is more a symptom than a cause of the breakdown. Erdogan is widely seen as an Islamist attempting to transform Turkey’s secular constitution, a political arrangement that Turkey’s military has historically defended. Yet the regime blames a Pennsylvania-based Turkish cleric for masterminding the coup, with the knowledge—and even cooperation—of its Western allies. “I have to say that this was done by foreign powers,” Erdogan told a group of foreign investors in Ankara. “The West is supporting terrorism and taking sides with coups.”

Think of that: a member of NATO—a coalition of democracies historically devoted to defending democracy against totalitarian aggression—accusing fellow members of attempting to overthrow its democratically established government.

Some suspect that Erdogan himself orchestrated the botched coup for political advantage. That seems far-fetched, but the crisis has allowed the president to consolidate his power: He has declared a three-month “state of emergency” to expunge suspected enemies of the state. So far, more than 60,000 people have fallen into the government net—fired, suspended, harassed, or arrested. Their ranks include teachers, university deans, judges, police, and military officers. Members of the Alevi religious minority—a Muslim group considered heterodox by the Sunni majority—also fear they will become special targets of retribution. In short, Turkey’s core democratic ideals and institutions are at risk, throwing into doubt its continued membership in NATO.

The 1949 NATO treaty was founded “on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law”—ideas antithetical to the totalitarian project of the Soviet Union. The seriousness of this democratic commitment was cemented in an unprecedented insurance policy, contained in Article 5 of the treaty: an “armed attacked against one or more” of its member states “shall be considered an attack against them all.”

With scant experience in democratic self-rule, Turkey fell short of these principles when it was admitted to NATO in 1952. The nation had taken a significant step toward multi-party democracy in 1950, when it elected an opposition party over its secularist CHP party. But the military retained an outsized role, ready to intervene to defend the secular constitution.

Turkey’s admission into NATO coincided with a new phase of the Cold War, as the Soviet Union tightened its grip over Eastern Europe. In 1948, the Soviets staged a communist coup that toppled the democratic government in Czechoslovakia. In 1949, Joseph Stalin tried to force the Allies out of West Berlin by blockading the city. In 1950, Moscow gave the green light to North Korea to invade South Korea, embroiling the United States in a hot war on the Korean peninsula.

Hence the strategic and prudential judgment of the West: NATO membership would guarantee that Turkey, a Muslim-majority nation, would not fall under Soviet influence as it sought to work out its political future.

The threat today, however, is that Turkey will succumb to an equally destructive and aggressive ideology: Islamic radicalism. Erdogan and his AKP party are accused of attempting to impose “political Islam” on the rest of Turkey. Others view his actions as a naked power grab, manipulating Islam to mask his political ambitions. Whatever his intentions, Erdogan’s response to the coup has further deepened the divisions in Turkish society and pitted Turkey against its democratic allies.

If an Islamist-style Turkey provokes an armed attack, should NATO come to its rescue? If Turkey continues on its current anti-democratic course, should it even remain in NATO? Some analysts are doubtful. Concludes Gregory Copley: “Turkey has now formally declared the U.S. (and therefore NATO) as its enemy.”

The Obama administration’s neglect of its relationship to Turkey—and of its Middle East allies more broadly—has invited dire consequences. At risk is Turkey’s position as a launching pad for U.S.-led airstrikes against Islamic State forces in Syria and Iraq; the stationing and safeguarding of about 50 U.S. nuclear weapons on the Incirlik Air Base in southeast Turkey; the dominant role of the Turkish navy in the strategic Black Sea; and the willingness of Turkey to continue to absorb millions of refugees from the Syrian civil war. The White House, eager to disengage from the region, never developed a coherent Middle East strategy that put Turkey near the center of its thinking.

Despite all of this, there was a bright moment in the failed coup attempt, a moment mostly ignored by the Western media, which is worth pondering.

As Turkish columnist Mustafa Akyol observed, the events of July 15 repudiated Erdogan’s paranoid narrative of secular politicians plotting his overthrow. When tanks rolled into Istanbul and Ankara, the major opposition parties—some of whose leaders I met last summer on the eve of a tense national election—publicly denounced the coup. Academics, business leaders, mainstream news media, and ordinary citizens also stood against the renegade military. “All of this shows that Turkish society has internalized electoral democracy,” writes Akyol, “and Turkey’s secularists, despite their objections to the Erdogan government’s Islamism, seek solutions in democratic politics.”

If that assessment is right, the nation’s liberal instincts offer a basis for a more hopeful path for Turkey—if it can be seized. After all, the fiercest critics of an autocratic leader, at a moment of national crisis, put partisan resentments aside and stood up for the principle of government by consent of the governed. Democratic reformers took to the streets to help rescue an illiberal democracy.

The Turkish government must not deceive itself—either through paranoia, false piety, or the lust for power. It owes its very existence to NATO and its Western allies and the democratic ideals they represent. If it walks away from this alliance, it steps, alone and conflicted, into the shadows of militant religion.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

July 23, 2016

National Review: Sorry, but Trump Is No Eisenhower

This article was originally posted at National Review.

When the Western Allies needed a supreme commander for the newly created North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949, they unanimously agreed that Dwight Eisenhower was “the only man” for the job. The soldier most responsible for the liberation of Western Europe would help make sure that the Soviet Red Army — which already had enslaved Eastern Europe — would not advance an inch further. “I rather look upon this effort,” he said, “as about the last remaining chance for the survival of Western civilization.”

Today millions of Republicans are cheering the nomination of Donald Trump as their presidential candidate, giddy over the fact that the business mogul has no political experience, not a shred of diplomatic experience, and lacks even a basic knowledge of America’s military assets, not to mention its national-security challenges. Eisenhower, also a political novice, nonetheless marshalled every ounce of his military and diplomatic knowhow to guide the nation safely, over eight years, through some of the most dangerous moments of the Cold War.

During the 1952 presidential campaign, the Republican nominee made a surprise announcement: “I shall go to Korea.” The Korean War, mired in stalemate and increasingly unpopular, was claiming 2,000 U.S. soldiers a month. Eisenhower, the former Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe during the Second World War — the man who planned the U.S.-led invasion at Normandy — believed he needed a first-hand look to see if this latest war was winnable. He determined that it wasn’t, and quickly brokered an honorable peace.

Within months of assuming office in 1953, Ike ordered a review of Harry Truman’s Containment Doctrine that redefined U.S. foreign policy as an ideological struggle against international Communism. Project Solarium, as it was called, produced recommendations from three separate committees — ranging from continuing with containment to adopting a much more confrontational strategy.

“The president had been sitting and listening to each one of the presentations, not taking a single note,” recalled General Andrew Goodpaster, Ike’s adviser. “He then rose and spoke for forty-five minutes, summarizing the three presentations and commenting on the specific strengths and weaknesses of each one.”

Eisenhower said he’d reject any strategy that couldn’t gain the support of America’s allies, or which made a general war with the Soviets more likely. He argued that the build-up in U.S. military strength must not trigger a total breakdown in international relations; needlessly forcing a showdown would be a tragic error. Thus Eisenhower embraced containment, pledging to minimize the risk of war while preventing Soviet expansion in Europe. George Kennan later recalled that the president demonstrated “intellectual ascendancy over every man in the room . . . He had such a mastery over the military issues involved.”

Imagine, if you can, Donald Trump exercising the mental discipline required to analyze a complex national-security crisis. Imagine him, playboy who dodged the military draft, showing mastery over the military issues involved. Yes, it is unimaginable.

Recall that by 1954, Eisenhower faced strong pressures to send American soldiers into Vietnam. The French were losing their battle against Communist insurgents to re-establish their control in Indochina. They desperately wanted American help in the form of boots on the ground. Pressure also came from Eisenhower’s cabinet — including Vice President Richard Nixon — to rescue the French effort and stop the spread of Communism. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, along with Ike’s Air Force Chief of Staff, even suggested that the United States drop three small atomic bombs on the Viet Cong.

Eisenhower was appalled. “You boys must be crazy,” he said. “We can’t use those awful things against Asians for the second time in ten years. My God.” Although Eisenhower warned of a “domino theory” in Southeast Asia if Vietnam fell to the Communists, he opposed direct U.S. military involvement. The French emphasized their common struggle in the Cold War, but Ike considered the French army a “hopeless, helpless mass of protoplasm.” In the end, he provided military assistance, but refused to send American troops into combat: “I cannot conceive of a greater tragedy for America than to get heavily involved now in an all-out war in any of these regions.”

When a war scare broke out in 1955 over Communist Chinese aggression in the Formosa Strait, American hawks again raised the specter of nuclear weapons in a preventive strike “to destroy Red China’s military potential and thus end its expansionist tendencies.” The Secretary of State claimed the Chinese were “more dangerous and provocative of war” than Adolf Hitler. Eisenhower rebuked them, telling reporters that a nuclear war against China would create human misery on a massive scale. “What,” he demanded to know, “would the civilized world do about that?”

How would a President Trump, who speaks admiringly of Vladimir Putin while promising to destroy the Islamic State in short order, approach a crisis involving Russia, North Korea, Iran, or Syria? How would Trump’s cavalier attitude toward NATO — he’s happy to see it dismantled — improve the security of the United States and its democratic allies? How, exactly, will his appalling ignorance of foreign affairs help him make life-and-death decisions?

Diplomatic experience does not always translate into good judgment, of course, as Hillary Clinton’s record of incompetence and failure abroad makes blazingly clear. But real-world experience is a pre-requisite for effective leadership in a violent and unstable era: It offers the statesman a dose of moral realism, helping him to navigate between pacifist dreams and militarist adventures.

In his farewell address, Eisenhower famously warned against the encroaching influence of the “military-industrial complex.” Yet he did not shrink back from strengthening U.S. military power relative to the Soviet Union. “As one who has witnessed the horror and the lingering sadness of war—as one who knows that another war could utterly destroy this civilization which has been so slowly and painfully built over thousands of years—I wish I could say tonight that a lasting peace is in sight.”

No leader was better prepared — emotionally, morally, intellectually — to safeguard America’s national security during a Cold War that at any moment threatened to become hot. As Eisenhower once told an aide: “God help this nation when it has a president who doesn’t know as much about the military as I do.”

Yes, in the season of Trump vs. Clinton, God help the United States of America.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

July 15, 2016

Providence: The Nice Attack and the Clash of Civilizations

This article was originally posted at Providence.

There should be no confusion about the identity and motives of the Tunisian man who drove his truck into a crowd celebrating Bastille Day on a promenade in Nice, France, killing at least 84 and injuring hundreds. This is the face of the modern holy warrior, the fanatical foot soldier in the Islamic jihad against the West.

The French government was warned, after the Paris attack in November 2015, that its military intervention against the Islamic State made it a prime object of Islamist rage. As ISIS declared:

Let France and those who walk in its path know that they will remain on the top of the list of targets of the Islamic State, and that the smell of death will never leave their noses as long as they lead the convoy of the Crusader campaign, and dare to curse our Prophet, Allah’s peace and blessing upon him, and are proud of fighting Islam in France and striking the Muslims in the land of the Caliphate with their planes, which did not help them at all in the streets of Paris and its rotten alleys.

Here is the enemy that President Obama declines to name, much less to engage with anything like martial resolve. “Groups like ISIL can’t destroy us. They can’t defeat us,” Obama said in March. “They can’t produce anything. They’re not an existential threat to us.” It is an evasion: Islamist radicals are determined to use any means possible—including suicide bombers armed with chemical and nuclear weapons—to become an existential threat. It is an evasion because the refusal to confront the religious ideology of Islamic terrorism produces what the 9/11 Commission Report called “a failure of imagination”—the failure to remain vigilant and anticipate the tactics and determination of the jihadists.

In a way rarely seen before in the heart of Europe, cities have become soft targets of terror: Even a lone individual, driving a truck down a crowded avenue and prepared to die for his god, can inflict massive casualties.

ISIS affiliates are reportedly cheering the latest carnage. President Obama condemned yesterday’s attack “in the strongest terms” and said he stands “in solidarity and partnership” with the French people. What the president will not say, of course, is that his policy of prevarication toward radical Islam has made these attacks much more likely: the failure of the U.S.-led “coalition” to defeat ISIS on the battlefield has become the organization’s most effective recruiting tool. France began airstrikes against ISIS in Iraq in September 2014. A year later, France extended the campaign to Syria, and has been fighting Boko Haram, the violent Nigerian group in league with ISIS. But without strong American leadership, France’s military involvement amounts to an ineffectual, pin-prick strategy for defeating the terrorists.

All of this puts France, a nation in which Muslims make up about 10 percent of the population, at special risk. According to a study released in April by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), France is the leading European country of origin for foreign fighters who join the ranks of ISIS in Syria and Iraq. Estimates vary, but roughly 2,000 radicalized French nationals have become part of jihadist networks. At least a third of all foreign fighters, according to the study, have returned to their home countries. In June, Belgian security forces warned that France and Belgium faced “imminent” attacks from ISIS cells travelling across Europe. Eight months ago, after the Paris assault that killed 147, French President Francois Hollande placed the nation under a state of emergency.

It didn’t matter. Details are still coming in, but it takes no leap of logic to view the Bastille Day massacre as something much more than a target of convenience. July 14, 1789, the day of the storming of the Bastille Prison and the start of the French Revolution, marks not merely the popular assault on despotic power. It commemorates for the French a new phase in the European debate over human rights: belief in the natural freedom and equality of every human being as the moral bedrock of liberal democracy.

President George W. Bush was mocked and excoriated by then Senator Barack Obama and his liberal allies for engaging the United States in a “clash of civilizations,” a false contest between militant Islam and the West. In his view, Bush was a clumsy Manichean, a medieval Crusader who was ignorant of the “root causes” of terrorism: poverty, Western imperialism, etc. Although each new atrocity has exposed this narrative as fatuous nonsense, the Obama White House has nevertheless worked to ban the war-footing mentality from every agency of government.

Yet the war against the moral norms of Western Civilization rages on—in London, Paris, Brussels, Istanbul, Nice, and beyond. The policies of retreat and retrenchment have failed. Europe is now bearing the brunt of that failure: thrust into the path of the gathering storm. “The horror,” said Hollande, “the horror has, once again, hit France.”

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

July 14, 2016

Books and Culture: C. S. Lewis, George MacDonald, and the Great War

This article was originally posted at Books and Culture.

In March 1916, while waiting for a train at Great Bookham Station in Surrey, England, a precocious student with a taste for fantasy walked over to a book stall and bought a copy of Phantastes: A Faerie Romance. The young man’s name was C. S. Lewis. The work transformed him. “A few hours later,” he concluded, “I knew that I had crossed a great frontier.” Reaching deeply into his imagination, the book challenged his growing atheism and ultimately helped to make plausible the Christian account of the human predicament.

Many readers of Lewis are aware of MacDonald’s influence, but the timing of the book’s impact, a century ago, is perhaps not so well known. It is surely relevant that Lewis first encountered Phantastes in the middle of the Great War, with millions of soldiers already dead, with fresh reports of the slaughter at Verdun, with the prospect of the trenches haunting his 18-year-old mind. After a visit from his older brother, Warren, already serving as a second lieutenant with the British Expeditionary Force, Lewis noted in his diary: “had ghastly dreams about the front and getting wounded last night.”

While studying the classics under a tutor before applying to Oxford, Lewis was reaching for authors who would nourish a growing taste for fantasy and romance: William Morris, E. R. Eddison, John Keats, and Percy Bysshe Shelley. By his own description, he found himself “waste deep in Romanticism.” MacDonald (1824-1905), a dissenting Scottish minister turned author, wrote fantasy novels and children’s stories that became classics of the genre. Phantastes explores what at first seems …

Read more at Books and Culture .

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

July 12, 2016

Providence: NATO’s Gathering Storm

This article was originally posted at Providence.

On the eve of the NATO summit in Warsaw last weekend, the Atlantic Council released a report declaring that the Alliance “faces the greatest threat to peace and security in Europe since the end of the Cold War.” The report’s authors, Ambassador Nicholas Burns, lead negotiator on Iran’s nuclear program and an advisor to Hillary Clinton, and General James Jones, a former national security advisor to President Obama, announced that NATO “needs more consistently strong, determined American presidential leadership.”

Well, now. One is at pains to ask what these national security mavens were doing when the Obama administration opted to effectively ignore NATO as it “pivoted” to the Asia-Pacific theater.

In January 2012, the White House released its strategic guidance white paper, “Sustaining Global Leadership,” which justified the new Asia policy by insisting that “most European countries are now producers of security rather than consumers of it.” Since Europe no longer faced any serious security threats, “our posture in Europe must also evolve.” The already-dwindling number of U.S. forces in Europe would be cut in half.

We may add this strategic blunder to the laundry list of myopic miscalculations that have characterized the Obama White House and helped create the threats facing NATO and now so loudly deplored.

Four and a half years after that infamous white paper, the results are in: Russia smelled American ambivalence about European security and moved swiftly to violate Ukrainian sovereignty by seizing Crimea. The Islamic State—belittled by the White House as a “junior varsity” version of al Qaeda—has spread its murderous mayhem in Europe while redrawing the map of the Middle East. And the Syrian civil war, prolonged and deepened by presidential paralysis, has created a refugee crisis that endangers the security of NATO member states.

All of this has occurred as the military strength and preparedness of the 28-member Alliance has deteriorated. By 2015, average military spending among NATO states fell to its lowest level, at 1.45 percent of GDP. Despite a modest increase in 2016, just five Allies meet the NATO guideline to spend a minimum of 2 percent of their GDP on defense. Focusing much of its resources in areas outside of Europe—Afghanistan remains its primary operational theater—the Alliance has been caught off guard by the crises in its own backyard. Even President Obama, indifferent to the consequences of American retrenchment, nevertheless admitted at Warsaw: “In the nearly 70 years of NATO, perhaps never have we faced such a range of challenges all at once: security, humanitarian, political.”

The question now is this: will NATO act decisively to reverse these trends? NATO leaders promised to bolster Europe’s defenses against an “arc of insecurity and instability” from Moscow to North Africa. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg declared that “an independent, sovereign and stable Ukraine, firmly committed to democracy and the rule of law, is key to Euro-Atlantic security.”

The most significant announcement during the two-day summit was the decision to maintain roughly 13,000 troops in Afghanistan indefinitely, and to continue funding the Afghan National Security Forces in their fight against the Taliban. Still, troop levels remain inadequate to the task. The other commitments offer scant evidence of a NATO reformation at hand. A proposed “comprehensive assistance package” to Ukraine—including money for cyber defense and the “rehabilitation of wounded soldiers”—lacks the military assistance needed to actually deter further Russian aggression. Summit leaders pledged four battalions of roughly 1,000 soldiers each to be stationed in Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: states with painful memories of Soviet occupation. But this is a baby-step that would prove laughably inadequate in the face of a significant military threat.

The Warsaw meeting marked President Obama’s final NATO summit and, despite nearly eight years in office, he and his national security team remain in denial: “NATO is as strong, as ready and as nimble as ever.” That sounds like PR pabulum from Obama advisor Ben Rhodes, and no one believes it. Worse still, Obama and much of the liberal foreign policy establishment seem largely ignorant of the reasons for NATO’s success through the Cold War.

The political-moral premise of NATO was that the Soviet Union, rooted in a malevolent political ideology, could only be deterred from further aggression by the credible threat of overwhelming military force. Every aspect of American diplomacy during the Cold War proceeded from this moral principle.

The North Atlantic Treaty, signed on April 4, 1949, signaled a radical break from American isolationism: a peacetime alliance with the democratic nations of Europe in defense of Western security. Such a treaty became possible only because Soviet ambitions—its absorption of Czechoslovakia and blockade of Berlin the same year—stirred Americans out of complacency. And, from the very beginning, the Alliance required a dominant U.S. leadership role. “The Atlantic Alliance,” writes Henry Kissinger in World Order, “while it combined the military forces of the allies in a common structure, was sustained largely by unilateral American military power.”

Critics of Britain’s decision to leave the European Union have warned, with near hysteria, about its effect on European security—as if the EU brought about the stability and prosperity of modern Europe. In fact, it was NATO, united in its opposition to communist tyranny, that allowed democratic values and institutions to take root and flourish. The premier role of the United States in this military-political alliance helped to contain and ultimately defeat the Soviet Union, while avoiding another war on the European continent—a remarkable achievement.

How did they do it? NATO members, prodded by the United States, confronted honestly the ideological threat facing them during the Cold War. The character of that threat was described in detail in NSC-68, the National Security Council’s manifesto that defined the struggle with a philosophical clarity lacking among today’s policymakers:

Thus unwillingly our free society finds itself mortally challenged by the Soviet system. No other value system is so wholly irreconcilable with ours, so implacable in its purpose to destroy ours, so capable of turning to its own uses the most dangerous and divisive trends in our own society, no other so skillfully and powerfully evokes the elements of irrationality in human nature everywhere, and no other has the support of a great and growing center of military power.

The leaders who gathered at Warsaw are acutely aware of the problems facing their member states. There was much talk of the continuing threat of Russian belligerence, as well as the ongoing refugee and migrant crisis. But the focus seemed to be on the symptoms of these problems, rather than their causes. Their official communique acknowledged that the Islamic State “reaches into all of Allied territory, and now represents an immediate and direct threat to our nations and the international community.” Yet they managed to avoid any discussion of the political theology animating this threat or suggest a strategy for actually defeating it.

At the NATO summit the president declared the “unwavering commitment of the United States to the security and defense of Europe.” But like so many of Obama’s words, they had a vacuous and unconvincing ring about them, betrayed by an administration that still fails to grasp the relationship between power and diplomacy. As Anne Pierce wrote recently in this space, Obama’s flawed approach to deterrence has transformed American “soft power” into the “softening of American power and democratic leadership.”

It is ironic that Warsaw thus became the setting for another round of liberal bromides about peace and security. For Warsaw once represented the last outpost of resistance against Nazi tyranny before Poland’s liberation at the end of the Second World War: the Warsaw Uprising by Polish freedom-fighters. And yet, at the moment of its liberation, the city of Warsaw played host to the Soviet absorption of Poland into the Communist bloc, made possible by its betrayal at the Yalta Conference in 1945. A decade later came the Warsaw Pact, cementing Moscow’s military stranglehold over Eastern Europe.

Warsaw thus represented a defeat of the forces of democracy, authorized by another naïve American president who imagined that his diplomatic prowess could tame Joseph Stalin and the barbarism of Soviet communism. “I believe that we are going to get along very well with him and the Russian people,” declared Franklin Roosevelt, “very well indeed.”

Though once symbolizing the spirit of democratic defiance in the West, Warsaw fell under a shadow of self-delusion and defeat. With Europe and NATO at another crossroads, it is too early to tell which direction the West ultimately will take.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

July 1, 2016

New York Times: How J.R.R. Tolkien Found Mordor on the Western Front

This article was originally posted at The New York Times.

IN the summer of 1916, a young Oxford academic embarked for France as a second lieutenant in the British Expeditionary Force. The Great War, as World War I was known, was only half-done, but already its industrial carnage had no parallel in European history.

“Junior officers were being killed off, a dozen a minute,” recalled J. R. R. Tolkien. “Parting from my wife,” he wrote, doubting that he would survive the trenches, “was like a death.”

The 24-year-old Tolkien arrived in time to take part in the Battle of the Somme, a campaign intended to break the stalemate between the Allies and Central Powers. It did not.

The first day of the battle, July 1, produced a frenzy of bloodletting. Unaware that its artillery had failed to obliterate the German dugouts, the British Army rushed to slaughter.

Before nightfall, 19,240 British soldiers — Prime Minister David Lloyd George called them “the choicest and best of our young manhood” — lay dead. That day, 100 years ago, remains the most lethal in Britain’s military history.

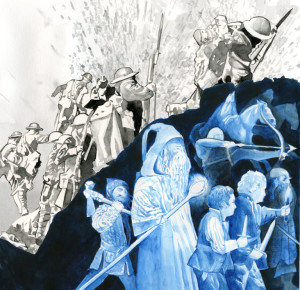

Though the debt is largely overlooked, Tolkien’s supreme literary achievement, “The Lord of the Rings,” owes a great deal to his experience at the Somme. Reaching the front shortly after the offensive began, Tolkien served for four months as a battalion signals officer with the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers in the Picardy region of France.

Using telephones, flares, signal lights, pigeons and runners, he maintained communications between the army staff directing the battles from the rear and the officers in the field. According to the British historian Martin Gilbert, who interviewed Tolkien decades later about his combat experience, he came under intense enemy fire. He had heard “the fearful cries of men who had been hit,” Gilbert wrote. “Tolkien and his signalers were always vulnerable.”

Tolkien’s creative mind found an outlet. He began writing the first drafts of his mythology about Middle-earth, as he recalled, “by candle light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire.” In 1917, recuperating from trench fever, Tolkien composed a series of tales involving “gnomes,” dwarves and orcs engaged in a great struggle for his imaginary realm.

In the rent earth of the Somme Valley, he laid the foundation of his epic trilogy.

The descriptions of battle scenes in “The Lord of the Rings” seem lifted from the grim memories of the trenches: the relentless artillery bombardment, the whiff of mustard gas, the bodies of dead soldiers discovered in craters of mud. In the Siege of Gondor, hateful orcs are “digging, digging lines of deep trenches in a huge ring,” while others maneuver “great engines for the casting of missiles.”

On the path to Mordor, stronghold of Sauron, the Dark Lord, the air is “filled with a bitter reek that caught their breath and parched their mouths.” Tolkien later acknowledged that the Dead Marshes, with their pools of muck and floating corpses, “owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme.”

In a lecture delivered in 1939, “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien explained that his youthful love of mythology had been “quickened to full life by war.” Yet he chose not to write a war memoir, and in this he departed from contemporaries like Robert Graves and Vera Brittain.

In the postwar years, the Somme exemplified the waste and futility of battle, symbolizing disillusionment not only with war, but with the very idea of heroism. As a professor of Anglo-Saxon back at Oxford, Tolkien preferred the moral landscape of Arthur and Beowulf. His aim was to produce a modern version of the medieval quest: an account of both the terrors and virtues of war, clothed in the language of myth.

In “The Lord of the Rings,” we meet Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee, Hobbits of the Shire, on a fateful mission to destroy the last Ring of Power and save Middle-earth from enslavement and destruction. The heroism of Tolkien’s characters depends on their capacity to resist evil and their tenacity in the face of defeat. It was this quality that Tolkien witnessed among his comrades on the Western Front.

“I have always been impressed that we are here, surviving, because of the indomitable courage of quite small people against impossible odds,” he explained. The Hobbits were “a reflection of the English soldier,” made small of stature to emphasize “the amazing and unexpected heroism of ordinary men ‘at a pinch.’ ”

When the Somme offensive was finally called off in November 1916, a total of about 1.5 million soldiers were dead or wounded. Winston Churchill, who served on the front lines as a lieutenant colonel, criticized the campaign as “a welter of slaughter.” Two of Tolkien’s closest friends, Robert Gilson and Ralph Payton, perished in the battle, and another, Geoffrey Smith, was killed shortly afterward.

Beside the courage of ordinary men, the carnage of war seems also to have opened Tolkien’s eyes to a primal fact about the human condition: the will to power. This is the force animating Sauron, the sorcerer-warlord and great enemy of Middle-earth. “But the only measure that he knows is desire,” explains the wizard Gandalf, “desire for power.” Not even Frodo, the Ring-bearer and chief protagonist, escapes the temptation.

When Tolkien’s trilogy was published, shortly after World War II, many readers assumed that the story of the Ring was a warning about the nuclear age. Tolkien set them straight: “Of course my story is not an allegory of atomic power, but of power (exerted for domination).”

Even this was not the whole story. For Tolkien, there was a spiritual dimension: In the human soul’s struggle against evil, there was a force of grace and goodness stronger than the will to power. Even in a forsaken land, at the threshold of Mordor, Samwise Gamgee apprehends this: “For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: There was light and high beauty forever beyond its reach.”

Good triumphs, yet Tolkien’s epic does not lapse into escapism. His protagonists are nearly overwhelmed by fear and anguish, even their own lust for power. When Frodo returns to the Shire, his quest at an end, he resembles not so much the conquering hero as a shellshocked veteran. Here is a war story, wrapped in fantasy, that delivers painful truths about the human predicament.

Tolkien used the language of myth not to escape the world, but to reveal a mythic and heroic quality in the world as we find it. Perhaps this was the greatest tribute he could pay to the fallen of the Somme.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

June 28, 2016

Weekly Standard: The Somme 1916, and the Funeral of a Great Myth

This article was originally posted at The Weekly Standard.

At 7 a.m. on July 1, 1916, the British Army unleashed a hellish assault against German positions on the Western Front in France, along the River Somme. The roar was so loud that it was heard in London, nearly 200 miles away. The barrage—about 3,500 shells a minute—was designed to obliterate the deepest dugouts and severely compromise German artillery and machine-gun power. Crossing No Man’s Land, that dreadful death zone stretching between opposing enemy trenches, would be a song.

Thus, at 7:30 a.m., nearly a hundred thousand British troops—to the sound of whistles, drums, and bagpipes—climbed out of their trenches and attacked. Like other great battles, this one was supposed to break the back of the German Army and hasten the end of the war. But the Germans had endured the pounding and were waiting, guns poised, for the British infantry. “We didn’t have to aim,” said a German machine-gunner. “We just fired into them.” Before the day was over, 19,240 British soldiers lay dead, nearly twice that number wounded. Most were killed in the first hour of the attack, many within the first minutes.

July 1, 1916, marks the deadliest single day in British military history. Sir Frank Fox, a regimental historian, summarized the scene this way: “In that field of fire nothing could live.” The Battle of the Somme would rage on, inconclusively, until November 18, dragging over a million men into its vortex of suffering and death.

Twenty-four-year-old J. R. R. Tolkien, a second lieutenant in the British Expeditionary Force, was among their number—an experience that would shape the course of his life and literary career. Tolkien spent nearly four months in the trenches of the Somme valley, often under intense enemy fire. As he recalled years later: “One has indeed personally to come under the shadow of war to feel its full oppression.” A hundred years hence and the Somme offensive still casts its oppressive shadow across the landscape of the West. It symbolizes not only the human tragedy of an ill-conceived war but the fearsome cost of a mistaken idea: the notion of human perfectibility.

The Dogma of Human Progress

By the start of the 20th century, attitudes about war and what it could accomplish were bound up with a singular, overarching idea: the myth of progress. Perhaps the most deeply held view in the years leading up to the First World War was that Western civilization was marching inexorably forward, that human nature was evolving and improving—that new vistas of political, cultural, and spiritual achievement were within reach.

Herbert Spencer, who converted Darwin’s theory of evolution into a social doctrine, had much to do with this. So did the success of the scientific and industrial revolutions. “Between 1900 and 1914, technological, social and political advances swept Europe and America on a scale unknown in any such previous timespan,” writes British historian Max Hastings, “the blink of an eye in human experience.”

Confidence in human progress led some to believe that, with the help of modern technologies, wars could be fought with minimal cost in life and treasure. Others argued that rational Europeans would soon dispense with war altogether. In The Great Illusion, British writer Norman Angell claimed that the Industrial Revolution—by creating economic growth and interdependence—had changed the dynamic among nation-states. The great industrial nations of Britain, France, Germany, and the United States were “losing the psychological impulse to war,” he wrote, just as they abandoned the impulse to kill their neighbors over religion. “The least informed of us realizes that the whole trend of history is against the tendency for men to attack the ideals and the beliefs of other men.”

First published in 1909, The Great Illusion became a runaway bestseller. The book seemed to speak to a deep and widely shared aspiration: the “perpetual peace” imagined by philosophers such as Immanuel Kant. Novelist H. G. Wells recalled the mood: “I think that in the decades before 1914 not only I but most of my generation—in the British Empire, America, France and indeed throughout most of the civilized world—thought that war was dying out. So it seemed to us.”

Such a view was congenial to religious leaders, especially those uncomfortable with Christianity’s doctrine of the fall from grace. On the eve of the outbreak of the war, Britain’s National Peace Council, a coalition of religious and secular peace organizations, foresaw an era of international harmony. The 1914 edition of its Peace Yearbook offered this astonishing prediction:

Peace, the babe of the nineteenth century, is the strong youth of the twentieth century; for War, the product of anarchy and fear, is passing away under the growing and persistent pressure of world organization, economic necessity, human intercourse, and that change of spirit, that social sense and newer aspect of worldwide life which is the insistent note, the Zeitgeist of the age.

This “change of spirit” was heralded from virtually every sector of society. Scientists, educators, industrialists, salesmen, politicians, preachers—all agreed on the upward flight of humankind. Each breakthrough in medicine, science, and technology confirmed it. Every invention and innovation was offered up as evidence, from Marconi’s radio transmissions to the Maxim machine gun. Darwin’s theory about biological change had ripened into a social assumption—a dogma—about human improvement, even perfection.

Or so it seemed to Tolkien and to his Oxford friend, C. S. Lewis, also a war veteran. “I grew up believing in this Myth and I have felt—I still feel—its almost perfect grandeur,” Lewis confessed. “It is one of the most moving and satisfying world dramas which have ever been imagined.” Importantly, the triumph of science and technology left no meaningful role for faith. Science, not religion, was driving human achievement. “Man was responsible for his own earthly destiny,” writes historian Richard Tarnas in The Passion of the Western Mind. “His own wits and will could change his world. Science gave man a new faith—not only in scientific knowledge, but in himself.”

A Glimpse of Mordor

Ironically, the tools of science that produced such optimism created the conditions that would smash it to pieces. Mortars, machine guns, poison gas, the mass production of artillery, the mechanized transport of troops and armaments: In the hands of military planners and politicians, science increased exponentially the destructive power of war.

The result was an assault on man and nature on a scale never before experienced in the West. When the Battle of the Somme was finally called off in November 1916, much of the Somme valley—a verdant mix of farms and forests—was desolate. Trees had been reduced to blackened sticks. Fields and crops were swallowed up by waves of mud and massive craters, filled with water. The stench of explosives and unburied corpses hung in the air.

Tolkien served as a battalion signals officer with the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers until trench fever took him out of the war. It was during this period that he laid the foundation for his mythology about an epic struggle for Middle-earth. Writing from his hospital bed, Tolkien produced a series of stories (later published as The Book of Lost Tales), which would inform his major works: The Silmarillion, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings. Each involves a violent contest between good and evil—and in each there are hints of the horrors of the Somme.

In The Lord of the Rings, Middle-earth is threatened by Sauron, the dark lord of Mordor, who seeks to possess the Ring of Power. The story centers on Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee, hobbits from the Shire, and their quest to destroy the ring and save Middle-earth. As they approach Mordor, they encounter a brooding and lifeless wasteland. “The gasping pits and poisonous mounds grew hideously clear,” Tolkien wrote. “The sun was up, walking among clouds and long flags of smoke, but even the sunlight was defiled.” Passing through the marshes, Sam catches his foot and falls on his knees, “so that his face was brought close to the surface of the dark mire.” Looking intently into the muck, he is startled. “There are dead things,” he exclaims, “dead faces in the water!”

Historian Sir Martin Gilbert, author of a definitive account of the Somme offensive, interviewed Tolkien in the 1960s about his life as a soldier. He notes that Tolkien’s description of the dead marshes matches precisely the macabre experience of soldiers at the Somme: “Many soldiers on the Somme had been confronted by corpses, often decaying in the mud, that had lain undisturbed, except by bombardment, for days, weeks and even months.” In a letter to L. W. Forster written on December 31, 1960, Tolkien confirmed the connection: “The Dead Marshes and the approaches to Morannon [Mordor] owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme.”

Although Tolkien never intended to write a trench memoir, we may suspect that memories of combat informed his description of the “Siege of Gondor” in The Lord of the Rings:

Yet their Captain cared not greatly what they did or how many might be slain: their purpose was only to test the strength of the defense and to keep the men of Gondor busy in many places. All before the walls on either side of the Gate the ground was choked with wreck and with bodies of the slain; yet still driven as by a madness more and more came up.

Hundreds of antiwar novels, memoirs, and works of poetry were published in the 1920s and 1930s, helping to create an image of war as inherently futile and irrational. The poems of Wilfred Owen, who was wounded three times before being killed in battle, offered no place for heroism: “What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? / Only the monstrous anger of the guns.” T. S. Eliot, in his epic 1922 poem, The Waste Land, seemed to speak for many in the post-war generation: “I think we are in rats’ alley / where the dead men lost their bones.”

For these authors, the First World War exposed the myth of progress for what it was—a monstrous illusion about the “civilized” West. The advanced “Christian” nations of Europe had engaged in a mutual suicide pact, leaving nearly 10 million soldiers dead and millions more grievously wounded. A frightening share of young men were emotionally debilitated by trench warfare and committed to asylums. “When at last it was over, the war had many diverse results,” wrote Barbara Tuchman in The Guns of August, “and one dominant one transcending all others: disillusion.”

The disillusionment of the postwar generation found an outlet—in literature, the arts, philosophy, religion, and politics. Just consider some of the books published in the first years after the conflict: The End of a World (1920), Social Decay and Degeneration (1921), The Decay of Capitalist Civilization (1923), The Twilight of the White Races (1926), and Oswald Spengler’s sweeping work, The Decline of the West (1918). “We cannot help it if we are born as men of the early winter of full Civilization,” Spengler wrote, “instead of on the golden summit of a ripe Culture.”

The Great War seemed to confirm a fatal weakness in liberal democracy, creating an openness to all kinds of utopian and illiberal schemes. When the Communist International held its first World Congress in 1919, for example, it drew delegates from 26 countries, including the United States. Meanwhile, European fascism emerged first in Italy, a society in tatters. A huge number of Mussolini’s “Blackshirts”—his 40,000-strong militia that marched on Rome and seized power in 1922—were disenchanted veterans. Within a decade, fascist parties and regimes took root all over Europe.

One of the most striking effects of the myth of progress was that, at the outbreak of war in 1914, many expected social and spiritual regeneration. Church leaders preached that war would advance the ideals of Christianity and democracy, that it would give birth to an epoch of peace and righteousness. Just as the earlier crusaders had unified Europe, wrote London minister Joseph Fort Newton, “so this, the greatest humanitarian crusade in history, will unify the world.” The progressive vision, rooted in secular idealism, had infiltrated European (and American) Christianity.

The catastrophic failure of this worldview created a backlash—an animus against the old religious orthodoxies. Christian faith and morality became two more casualties of the war. When T. S. Eliot was baptized into the Church of England in 1927, Virginia Woolf, a member of London’s literary set, was appalled. “I have had a most shameful and distressing interview with poor dear Tom Eliot, who may be called dead to us all from this day forward,” she wrote to a friend. “I mean, there’s something obscene in a living person sitting by the fire and believing in God.”

The door was thrust open to substitute religions—from fascism to Freudian psychology to Rudolph Steiner’s anthroposophy. Gilbert Murray, in his 1929 book The Ordeal of This Generation, bemoaned the “large and outspoken rejection” of Christianity. The false prophets of progress had discredited themselves and the values and institutions they claimed to defend. “The Age of Progress ends in a barbarism such as shocks a savage,” wrote Paul Bull, a former war chaplain. “The Age of Reason ends in a delirium of madness.”

Tolkien’s Heroic Vision

All of this makes Tolkien’s literary aims profoundly countercultural, even subversive. Like no previous war, the Great War assaulted the concepts of heroism, valor, and virtue. The helplessness of the individual soldier, ravaged by the instruments of modernity, was a recurring motif in the postwar period. Tolkien rebelled against this outlook. As a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford, he was at home in the worlds of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Tolkien sought to retrieve something of the medieval Christian tradition, the story of the great and noble quest.

Herein lies the signal achievement of his epic trilogy. In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien recovers the mythic concept of the heroic struggle against evil—and reinvents it for the modern mind. “To say that in it heroic romance, gorgeous, eloquent, and unashamed, has suddenly returned at a period almost pathological in its anti-romanticism is inadequate,” wrote C. S. Lewis in an early review. “Nothing quite like it was ever done before.”

How did he accomplish it? Although Tolkien’s work appears to lack a religious framework—there are no prayers or deities—its characters are conscious of a universal Moral Law to which they must give account. “How shall a man judge what to do in such times,” asks Éomer. “As he ever has judged,” replies Aragorn. “Good and ill have not changed since yesteryear; nor are they one thing among Elves and Dwarves and another among Men. It is a man’s part to discern them.” Lewis declared this to be “the basis of the whole Tolkienian world.”

In the conflict between Mordor and Middle-earth, every soul is tested. Every creature must choose sides in a titanic struggle between darkness and light; moral indifference is never an option. In Tolkien’s vision, heroic sacrifice for a just cause—even against terrible odds—carries its own transcendent meaning.

The vital thing is to remain faithful to the quest, regardless of the costs and perils. Frodo’s mission is to carry the Ring of Power to the fires of Mount Doom and destroy it—before it can destroy him. “I am not made for perilous quests,” Frodo exclaims. “Why was I chosen?” Replies Gandalf: “You may be sure that it was not for any merit that others do not possess: not for power or wisdom, at any rate. But you have been chosen, and you must therefore use such strength and heart and wits as you have.”

Here again Tolkien’s experience at the Somme worked on his imagination. Where did Tolkien get the idea for his hobbits? From being in close company with the ordinary English soldier and witnessing his loyalty and determination under fire. War correspondent Philip Gibbs, a critic of the military leadership, confessed his astonishment at the discipline and valor of the British Expeditionary Force, praising “individual courage beyond the natural laws of human nature as I thought I knew them once.” Tolkien explained that he made his hobbits small in size to reflect the hidden virtues of his fellow soldiers. “My ‘Sam Gamgee’ is indeed a reflection of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war,” he wrote, “and recognized as so far superior to myself.”

The Somme offensive left about 1.5 million men dead and wounded among the Allied and Central Powers, making it one of the most lethal battles in history. And to what end? In military terms, the campaign achieved almost nothing, since most of the British soldiers were killed on ground held by the British before the assault began. And yet the war continued for another two years, killing, maiming, and debilitating an entire generation. “Injuries were wrought to the structure of human society which a century will not efface,” wrote Winston Churchill, “and which may conceivably prove fatal to the present civilization.”

In this sense, the Somme represents the collision of facile dreams of human advancement with the loathsome limitations of human nature. For Tolkien, it marked the funeral of a great myth. Whatever illusions of human progress and perfectibility he may have nurtured in youth vanished into a storm of steel and death. Perhaps this helps explain the tragic dimension of Tolkien’s story: the failure of Frodo to willingly destroy the Ring of Power. In the end, the hero is not indomitable. “But one must face the fact,” Tolkien explained, “the power of Evil in the world is not finally resistible by incarnate creatures.”

The hero, and his quest, must be redeemed by an act of grace. Here is an epic myth, an ancient story, which the modern world still longs to hear.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West.

June 22, 2016

Huffington Post: Jo Cox And The Conscience Of The West

This article was originally posted at The Huffington Post.

The brutal murder of British parliamentarian Jo Cox, praised as a relentless and warm-hearted humanitarian, has sent a nation into mourning. A wife and mother of two small children, no British lawmaker fought harder for a more humane immigration policy toward refugees fleeing the Syrian civil war, especially the thousands of Syrian children who have lost their families in the conflict. Cox’s death invites some intense soul-searching — not only in Britain but also in the United States — about the West’s failure to prevent the worst humanitarian disaster since the Second World War.

Soon after joining Parliament in May 2015 as a Labour MP, the 41-year-old Cox help set up the All Party Parliamentary Group on Syria with Conservative MP Andrew Mitchell. The group collects evidence from military commanders, diplomats, and officials from the region about the plight of the roughly 4.5 million refugees who have fled Syria’s five-year civil war to neighboring countries. Earlier this year Cox fought for legislation to admit into the UK at least 3,000 child refugees from Syria — roughly three percent of the estimated 95,000 unaccompanied minors, mostly from Syria, now living precariously in Europe. “Those children have been exposed to things no child should ever witness,” she said, “and I know I would risk life and limb to get my two precious babies out of that hellhole.”

Though a junior parliamentarian in the opposition party, Cox quickly earned a reputation as a bold and principled human rights advocate. Her campaign for Syrian refugees was waged in the midst of Britain’s national debate over whether to remain in the European Union, which has been widely criticized for mishandling the immigration crisis. Cox’s assailant was a 52-year-old-man who shouted “Britain First,” a slogan associated with far right elements in Great Britain.

Many American conservatives would not agree with Cox’s views on immigration or her outspoken support for the European Union. But liberals would not have cheered her recent speech in Parliament, where she vigorously rebuked both David Cameron and Barack Obama for failing to act decisively to confront the escalating violence in Syria:

I believe that both President Obama and the Prime Minister made the biggest misjudgment of their time in office when they put Syria on the ‘too difficult’ pile. Instead of engaging fully, they withdrew and put their faith in a policy of containment. This judgment, made by both leaders for different reasons, will, I believe, be judged harshly by history, and it has been nothing short of a foreign policy disaster.

Of course, Cox is right: Britain has followed America’s lead on Syria, right into a moral quagmire of feckless and cynical diplomacy. Obama’s views on Syria were best expressed recently by Ben Rhodes, his principal foreign policy advisor: “Nothing we could have done,” Rhodes told a group of Syrian activists, “would have made things better.”

The problem is not just that the Obama White House has adopted, unflinchingly, this defeatist view of the Syrian tragedy. It is effectively the position of both presumptive party nominees for president, Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump. It is the position of Bernie Sanders, the Democratic Socialist who has drawn millions of voters into his isolationist mirage. It was, for anyone’s guess, the position of most of the 16 Republican presidential candidates who have since dropped out of the race.

The depth of America’s leadership crisis on Syria is indeed staggering. Aside from Rep. Chris Smith (R-New Jersey), Senator Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas), and a pitifully tiny handful of others, there are no members of Congress — Republican or Democrat — who match the humanitarian vision and commitment of Jo Cox. With regards to Syria’s refugee children, she has no counterpart in the U.S. Congress. Fears of Islamic radicals slipping into the refugee population have overtaken our politics, leaving child refugees out of sight and out of mind.

Secretary of State John Kerry, for his part, delivered a flawed Syrian “peace” initiative that simply allowed Bashar al Assad to strengthen his position, thanks to Russia’s unchallenged military intervention. The collapse of the peace plan, which has left tens of thousands of civilians at grave risk — many of them children — was predicted by diplomats involved in the negotiations. Even Samantha Power, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and an advocate of humanitarian intervention, has provided cover for the administration’s moral abdication in Syria.

Now compare Obama’s powder-puff diplomacy to that of Jo Cox, who took a Russian ambassador to task for his country’s bombing campaigns against Syrian civilians. “She was fearless, utterly fearless,” Andrew Mitchell wrote in The Telegraph. “Last year, we went to see the Russian ambassador in London, to give him a rollicking about the terrible way his country has behaved in Syria. He’s a professional diplomat and a pretty tough case. But Jo got the better of him: it was her mixture of charm and steel.”

Cox spent a decade at Oxfam, the British aid agency, and worked at the Freedom Fund, an anti-slavery organization, before joining Parliament. A devoted mother, she often brought her children with her into Westminster. Yesterday more than 1,500 parliamentarians from 40 countries signed a pledge to uphold Cox’s humanitarian legacy — an unprecedented expression of solidarity for a junior politician. “Jo was a lifelong campaigner against injustice,” the joint statement says. “We will do whatever it takes to renew our bonds and fight for those at the margins of our society, our continent, and the world.”

Can anyone imagine a similar outpouring of support for any major American politician?

Earlier this week in the House of Commons, parliamentarians wore white roses as they paid tribute to a colleague who had devoted most of her adult life helping people on the outskirts of civilization, regardless of race or creed. For an hour they spoke, with deep affection and eloquence, often choking back tears, as they put aside partisan differences to grieve together and to reflect on a remarkable life cut short. As one participant put it, “not in living memory has there been a House of Commons session like it.”

It is becoming increasingly difficult to imagine such a scene on the floor of the U.S. House or Senate: our politics has become so shallow and degraded, our leaders so morally compromised. In a nation once admired for its open borders, its commitment to human rights and humanitarian assistance, something has gone wrong — deeply and disturbingly wrong.

Jo Cox, I suspect, would have some ideas about how to set things right.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of God, Locke, and Liberty: The Struggle for Religious Freedom in the West.

Joseph Loconte's Blog

- Joseph Loconte's profile

- 70 followers