Joseph Loconte's Blog, page 11

January 15, 2018

Weekly Standard: In Praise of Folly

This article was originally posted at The Weekly Standard.

The presidency of Donald Trump, nearly a year old, has revived a political debate that began in earnest in sixteenth-century Europe: does a nation require leaders of good moral character in order to flourish?

Niccolo Machiavelli, who witnessed the violent collapse of the Florentine Republic, famously answered the question in the negative: Politicians must often commit acts of evil to maintain public order and unity—and they shouldn’t be troubled by this reality. “How praiseworthy it is for a prince to keep his word and to live with integrity and not by cunning, everyone knows,” he wrote in The Prince (1513). “Nevertheless, one sees from experience in our times that the princes who have accomplished great deeds are those who have thought little about keeping faith and who have known how cunningly to manipulate men’s minds.”

Trump is hardly the first president to put Machiavelli’s thesis to the test. What is stunning, though, is how he so easily has persuaded social and religious conservatives—the self-styled guardians of American virtue—that Machiavelli was right. How else to explain the enthusiasm among evangelicals for Trump, despite his unscrupulousness? They transformed Alabama’s Roy Moore, credibly accused of making sexual advances on teenage girls, into “God’s vessel” to advance Trump’s political agenda. They compare Trump, a conniving business mogul and reality television host, to Winston Churchill, the soldier-statesman who helped to rescue Western Civilization from Nazi barbarism.

Perhaps it’s time to recirculate a sixteenth-century blockbuster, In Praise of Folly (1511), the most trenchant rebuttal to the Machiavellian outlook ever written. Composed by the Christian humanist Desiderius Erasmus, it exposed the debased morality of the political and religious authorities of his day.

The work is narrated by Folly, wearing the costume of a fool and standing before an eager crowd to extol her own virtues. “I follow that well known proverb,” she explains, “which says that a person may very well praise himself if there happens to be no one else to praise him.” A leader can surround himself with flatterers and sycophants, she says, yet remain “a man ignorant of the law, almost an enemy to the common good, intent on advancing his own private interests, addicted to pleasure, a man who hates learning, who hates liberty and truth…”

In Praise of Folly skewers the idea that a perverse man could be a good governor: his corruption would spread “like a deadly plague” and infect the commonwealth. Public office imposed upon rulers a high standard of conduct, “so that he may either promote the welfare of his people by his spotless character, like a beneficent star, or he may, like a baleful comet, bring disaster upon them.” The just prince—rejecting the clamor of factions, the politics of tribalism, and his own private whims—must “give no thought to anything except the common good.”

In Renaissance Europe, where popes still functioned as kingmakers, political reform was nearly impossible without reform in the churches. Although a lifelong Catholic, Erasmus singled out the church establishment for its hypocrisy and spiritual pride. Folly chides clerics for “looking down from high above on all other mortals as if they were earth-creeping vermin almost worthy of their pity.” She upbraids believers for being “far more taken with appearances than reality.” She mocks theologians who wear close-fitting caps to distinguish themselves in public. “Therefore, don’t be surprised when you see them at public disputations with their heads so carefully wrapped up in swaths of cloth,” she explains, “for otherwise they would clearly explode.”

In Praise of Folly was condemned by the Catholic Church, excoriated by church authorities, and placed on the Index of Prohibited Books. It didn’t matter. The book’s subversive appeal could hardly be contained. During Erasmus’s lifetime, thirty-six editions appeared from the presses of twenty-one printers in eleven cities. His withering assessment of church and state touched a nerve, and arguably laid the groundwork for the Protestant Reformation.

Machiavelli effectively produced a how-to guide for cynically preserving the status quo. To maintain order, he wrote, a ruler “must often act against his faith, against charity, against humanity, and against religion.” To Erasmus, these were the tactics of Folly: the path to political ruin, social unrest, and cultural rot. There is truth in Machiavelli’s dictum that it is better to be feared than loved. But Erasmus believed that this brand of political realism, detached from religious conscience, would end in futility. As he warned elsewhere: “He who is feared by all must himself be in fear of many, and he whom the majority of people want dead cannot be safe.”

A man of letters and a counselor to princes, Erasmus was not naïve about the will to power. But, unlike Machiavelli, he was devoted to a program of social reform based on “the philosophy of Christ”—the teachings and example of Jesus—and rejected cynicism in all its forms. Against Machiavelli’s duplicitous secular prince, Erasmus wanted rulers trained in Christian ethics and morality. As Folly sardonically boasts: “I consider that I am being worshiped with the truest devotion when men everywhere do precisely what they now do: embrace me in their hearts, express me in their conduct, represent me in their lives.”

In the age of Trump, many have built a temple to Folly, burned incense, and bowed the knee at her altar. She has a habit, though, of betraying her worshippers and turning devotion into disillusionment.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

January 14, 2018

BBC RADIO: President Trump, One Year On

This article was originally posted at BBC Radio Wales.

On the eve of the election which put Donald Trump in the White House, All Things Considered brought together a panel of American commentators to discuss what they expected to happen. In this week of the first anniversary of his inauguration, we reunite them to talk about the reality, and in particular about the religious elements at play. We review an eventful and predictably controversial year for arguably the most unlikely individual ever to reach this office.

http://www.josephloconte.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/AllThingsConsidered-20180114.mp3

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

October 27, 2017

Wall Street Journal: How Martin Luther Advanced Freedom

This article was originally posted at The Wall Street Journal.

Martin Luther was an unlikely revolutionary for human freedom. When the Augustinian monk hammered his “Ninety-Five Theses” to the Wittenberg Castle Church on Oct. 31, 1517—and unleashed the Protestant Reformation—he was still committed to the spiritual authority of the Catholic Church and retained many of the prejudices of European Christianity.

Yet Luther’s personal experience of God’s love and mercy—“I felt myself to be reborn”—supported a democratic approach to religious belief. In his theological works, Luther introduced…

To view the rest of this article, please visit The Wall Street Journal.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

How Martin Luther Advanced Freedom

This article was originally posted at The Wall Street Journal.

Martin Luther was an unlikely revolutionary for human freedom. When the Augustinian monk hammered his “Ninety-Five Theses” to the Wittenberg Castle Church on Oct. 31, 1517—and unleashed the Protestant Reformation—he was still committed to the spiritual authority of the Catholic Church and retained many of the prejudices of European Christianity.

Yet Luther’s personal experience of God’s love and mercy—“I felt myself to be reborn”—supported a democratic approach to religious belief. In his theological works, Luther introduced…

To view the rest of this article, please visit The Wall Street Journal.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

National Geographic: Martin Luther and the Long March to Freedom of Conscience

This article was originally posted at National Geographic.

There is no simple explanation for why, 500 years ago, an obscure German monk decided to risk all and challenge the authoritative teaching of the Catholic Church. But by hammering 95 indictments to the door of All Saints’ Church at Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, Martin Luther launched a reformation with a singular effect. Deliberately or not, he overturned many of the bedrock assumptions of Western culture, instigating a revolution in human freedom that continues to shape the modern world.

At its heart, Luther’s protest against the church was theological, an attempt to recover the historic meaning of the Christian gospel from what he saw as a legalistic corruption. The pathway to peace with God, Luther insisted, was not through good works, religious rituals, or scholastic reasoning, but rather through heartfelt faith in Jesus Christ and his atoning death on a cross.

Nevertheless, in defending a gospel of salvation “by faith alone,” Luther introduced a new source of authority into the bloodstream of the West. For nearly a thousand years, every European man and woman owed allegiance to two kinds of authority: political (kings, nobles, magistrates) and religious (popes, councils, bishops, or their representatives). When it came to deciding matters of faith, however, Luther found both to be deeply flawed and untrustworthy.

This was the crux of Luther’s defense of his writings at the Diet of Worms in 1521. “My conscience is captive to the Word of God,” he told his accusers. “I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. Here I stand.” The individual believer and his conscience, standing before God and his Word—here was a confession that redefined the meaning of faith and the dignity of the human person.

In the process, Luther laid bare the scandal of Christendom: a political society that preserved spiritual unity through coercion and violence. Dissent from orthodoxy was outlawed, heresy was rooted out and punished by fire and sword. The papal bull of 1520 excommunicating Luther from the Catholic Church, for example, accused him of promoting 41 heresies and “pestiferous errors.” One of the alleged errors was his view that “the burning of heretics is against the will of the Holy Spirit.”

Luther did not address the issue of freedom of conscience in his Ninety-Five Theses, nor did he ever devise a political theory supporting religious pluralism. But his letters and major works leave no doubt that the father of the Protestant Reformation hoped to reconstruct the entire medieval approach to religious belief. Luther offers his fullest treatment of these issues in Secular Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed (1523), where he sharply distinguished the aims of church and state, limiting the reach of government to preserving life and property.

“For over the soul God can and will let no one rule but Himself,” Luther wrote. “Therefore, where temporal power presumes to prescribe laws for the soul it encroaches upon God’s government and only misleads and destroys the souls.”

Rejecting the notion of a Christian commonwealth, Luther argued that the state possessed neither the competence nor a mandate from heaven to intrude into spiritual matters. “The soul is not under Caesar’s power,” he wrote. “He can neither teach nor guide it, neither kill it nor make it alive.” Other reformers sought a radical separation of church and state, a concept that Luther ultimately rejected. Others went further in defending the rights of all religious believers, even heretics and non-believers, in civic and political life.

Nevertheless, virtually every important defense of religious freedom in the 17th century—the liberal politics of William Penn, Roger Williams, Pierre Bayle, and John Locke—took Luther’s insights for granted. “The one only narrow way which leads to heaven is not better known to the magistrate than to private persons,” wrote Locke in A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), “and therefore I cannot safely take him for my guide, who may probably be as ignorant of the way as myself, and who certainly is less concerned for my salvation than I myself am.”

In the 18th century, the United States became the first nation to enshrine in its constitution the Protestant conception of the rights of conscience. James Madison, the mind behind the First Amendment, was inspired by Luther’s achievement. In a letter to F.L. Schaeffer, dated 1821, Madison explained that the American model of religious liberty “illustrates the excellence of a system which, by a due distinction, to which the genius and courage of Luther led the way, between what is due to Caesar and what is due God, best promotes the discharge of both obligations.”

When the modern human rights movement took shape after the Second World War, a committee of public intellectuals acknowledged Luther as they searched for a philosophical basis for an international bill of rights. Their 1947 UNESCO document cited the Reformation, because of its “appeal to the absolute authority of the individual conscience,” as one of the historical events most responsible for the development of human rights.

Similarly, the language of Article 18 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—“everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion”—pays homage to Luther’s vision. Its prime author, Lebanese Ambassador Charles Malik, a delegate to the original UN Commission on Human Rights, was also a student of the Reformation. “People’s minds and consciences are the most sacred and inviolable things about them,” Malik wrote, “not their belonging to this or that class, this or that nation, or this or that religion.”

Today the Catholic Church, once a fierce opponent of religious liberty, is one of its most vigorous defenders on the world stage. “Man demands civil liberties that he may lead in society a life worthy of a man,” wrote John Courtney Murray, an architect of Vatican II’s support for the rights of conscience. “And this demand for freedom from coercion is made with special force in what concerns religion.” Here, it seems, is a quiet tribute to Luther’s revolution: “I will preach it, teach it, write it, but I will constrain no man by force, for faith must come freely without compulsion.”

The social realities of Christendom—the deep entanglement of church and state—prevented Luther from working out the implications of his political theology. Once Protestantism became an established faith, he approved the use of force against heretics; his rough treatment of Jews followed the woeful pattern of European Christianity.

Nevertheless, the moral courage and intellectual coherence of Luther’s dissent should not be undervalued. If Luther was a flawed prophet of human freedom, his voice was nonetheless vital in the long march toward a more just and pluralistic society. In Luther, we find an advocate for human dignity who defied the forces of religious oppression and reimagined the political ideals of medieval Europe.

In his defiance, Luther delivered a challenge to the conscience of the West like no other since the Sermon on the Mount—as essential today as it was half a millennium ago.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

Martin Luther and the Long March to Freedom of Conscience

This article was originally posted at National Geographic.

There is no simple explanation for why, 500 years ago, an obscure German monk decided to risk all and challenge the authoritative teaching of the Catholic Church. But by hammering 95 indictments to the door of All Saints’ Church at Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, Martin Luther launched a reformation with a singular effect. Deliberately or not, he overturned many of the bedrock assumptions of Western culture, instigating a revolution in human freedom that continues to shape the modern world.

At its heart, Luther’s protest against the church was theological, an attempt to recover the historic meaning of the Christian gospel from what he saw as a legalistic corruption. The pathway to peace with God, Luther insisted, was not through good works, religious rituals, or scholastic reasoning, but rather through heartfelt faith in Jesus Christ and his atoning death on a cross.

Nevertheless, in defending a gospel of salvation “by faith alone,” Luther introduced a new source of authority into the bloodstream of the West. For nearly a thousand years, every European man and woman owed allegiance to two kinds of authority: political (kings, nobles, magistrates) and religious (popes, councils, bishops, or their representatives). When it came to deciding matters of faith, however, Luther found both to be deeply flawed and untrustworthy.

This was the crux of Luther’s defense of his writings at the Diet of Worms in 1521. “My conscience is captive to the Word of God,” he told his accusers. “I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. Here I stand.” The individual believer and his conscience, standing before God and his Word—here was a confession that redefined the meaning of faith and the dignity of the human person.

In the process, Luther laid bare the scandal of Christendom: a political society that preserved spiritual unity through coercion and violence. Dissent from orthodoxy was outlawed, heresy was rooted out and punished by fire and sword. The papal bull of 1520 excommunicating Luther from the Catholic Church, for example, accused him of promoting 41 heresies and “pestiferous errors.” One of the alleged errors was his view that “the burning of heretics is against the will of the Holy Spirit.”

Luther did not address the issue of freedom of conscience in his Ninety-Five Theses, nor did he ever devise a political theory supporting religious pluralism. But his letters and major works leave no doubt that the father of the Protestant Reformation hoped to reconstruct the entire medieval approach to religious belief. Luther offers his fullest treatment of these issues in Secular Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed (1523), where he sharply distinguished the aims of church and state, limiting the reach of government to preserving life and property.

“For over the soul God can and will let no one rule but Himself,” Luther wrote. “Therefore, where temporal power presumes to prescribe laws for the soul it encroaches upon God’s government and only misleads and destroys the souls.”

Rejecting the notion of a Christian commonwealth, Luther argued that the state possessed neither the competence nor a mandate from heaven to intrude into spiritual matters. “The soul is not under Caesar’s power,” he wrote. “He can neither teach nor guide it, neither kill it nor make it alive.” Other reformers sought a radical separation of church and state, a concept that Luther ultimately rejected. Others went further in defending the rights of all religious believers, even heretics and non-believers, in civic and political life.

Nevertheless, virtually every important defense of religious freedom in the 17th century—the liberal politics of William Penn, Roger Williams, Pierre Bayle, and John Locke—took Luther’s insights for granted. “The one only narrow way which leads to heaven is not better known to the magistrate than to private persons,” wrote Locke in A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), “and therefore I cannot safely take him for my guide, who may probably be as ignorant of the way as myself, and who certainly is less concerned for my salvation than I myself am.”

In the 18th century, the United States became the first nation to enshrine in its constitution the Protestant conception of the rights of conscience. James Madison, the mind behind the First Amendment, was inspired by Luther’s achievement. In a letter to F.L. Schaeffer, dated 1821, Madison explained that the American model of religious liberty “illustrates the excellence of a system which, by a due distinction, to which the genius and courage of Luther led the way, between what is due to Caesar and what is due God, best promotes the discharge of both obligations.”

When the modern human rights movement took shape after the Second World War, a committee of public intellectuals acknowledged Luther as they searched for a philosophical basis for an international bill of rights. Their 1947 UNESCO document cited the Reformation, because of its “appeal to the absolute authority of the individual conscience,” as one of the historical events most responsible for the development of human rights.

Similarly, the language of Article 18 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—“everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion”—pays homage to Luther’s vision. Its prime author, Lebanese Ambassador Charles Malik, a delegate to the original UN Commission on Human Rights, was also a student of the Reformation. “People’s minds and consciences are the most sacred and inviolable things about them,” Malik wrote, “not their belonging to this or that class, this or that nation, or this or that religion.”

Today the Catholic Church, once a fierce opponent of religious liberty, is one of its most vigorous defenders on the world stage. “Man demands civil liberties that he may lead in society a life worthy of a man,” wrote John Courtney Murray, an architect of Vatican II’s support for the rights of conscience. “And this demand for freedom from coercion is made with special force in what concerns religion.” Here, it seems, is a quiet tribute to Luther’s revolution: “I will preach it, teach it, write it, but I will constrain no man by force, for faith must come freely without compulsion.”

The social realities of Christendom—the deep entanglement of church and state—prevented Luther from working out the implications of his political theology. Once Protestantism became an established faith, he approved the use of force against heretics; his rough treatment of Jews followed the woeful pattern of European Christianity.

Nevertheless, the moral courage and intellectual coherence of Luther’s dissent should not be undervalued. If Luther was a flawed prophet of human freedom, his voice was nonetheless vital in the long march toward a more just and pluralistic society. In Luther, we find an advocate for human dignity who defied the forces of religious oppression and reimagined the political ideals of medieval Europe.

In his defiance, Luther delivered a challenge to the conscience of the West like no other since the Sermon on the Mount—as essential today as it was half a millennium ago.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

June 23, 2017

Congressional Quarterly: Future of the Christian Right

This article was originally posted at The Congressional Quarterly.

Pro/Con

Will its support of President Trump hurt the Christian Right?

Pro

Joseph Loconte

Associate Professor of History, King’s College, New York City. Written for CQ Researcher, June 2017.

If the conservative Christians who endorsed Donald Trump for president are having qualms, there isn’t much evidence. Trump delivered his first commencement speech as president at evangelical Liberty University in Lynchburg, Va.

Liberty President Jerry Falwell Jr. delighted the audience with this hymn of praise: “I do not believe any president in our lifetimes has done so much that has benefited the Christian community in such a short time span as Donald Trump.”

Whatever the imagined benefits, the costs of enthusiasm for this presidency are likely to be severe.

First, the notion that character is irrelevant to political leadership is becoming normalized. For all the effort the Founders invested in designing a constitution, they never imagined that republican government could be preserved without virtue. George Washington, in his Farewell Address, deemed religion and morality “indispensable supports” to political prosperity, calling them the “firmest props of the duties of Men and citizens” and essential to patriots.

By embracing Trump, conservative Christians have validated a secular mythology about America’s experiment in self-government: no need for faith or morals. They have forgotten that history is littered with the tragic mistakes of leaders blinded by ambition, hubris, lust, racism and greed.

Second, we are likely to see a continued deterioration of trust in our political institutions. Conservatives complain that the political Left, by using executive orders and federal courts to impose a social agenda, has subverted the democratic process.

They have a point. But Trump is unlikely to reverse this trend. His personal attacks on public servants and government agencies — he has compared CIA officers to Nazis — make the problem worse. We can expect more cries to simply “blow up the system.”

Finally, there is the cancer of identity politics — an obsession with “rights” based on group identity, regardless of any obligations to the common good. This brand of tribalism, pioneered by liberals, now threatens to infect conservative Christianity. Hence the message of Trump supporters: The president can play the bully, as long as he is our bully. By endorsing a politics of grievance, Christians will further weaken and marginalize their influence in public life.

Is this the new face of Christians in politics? Maybe we need a little more of that old-time religion: the gospel of grace that rescues the poor in spirit and breaks the backs of the proud.

Con

Joshua C. Wilson, Amanda Hollis-Brusky

Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Denver; Associate Professor of Politics, Pomona College. Written for CQ Researcher, June 2017.

In 2016, the Christian Right seemed headed for a walk in the political wilderness. The Supreme Court had ruled against a promising means of restricting abortion access, and Hillary Clinton’s anticipated election would allow Democrats to fill a vacant Supreme Court seat. The fight against gay marriage appeared lost, and the emerging battle against the transgender community had met potent resistance.

The November election changed everything. And while some argue that support of President Trump could harm conservative Christians, it already has produced benefits, redirecting the movement from the margins to the center of power. The appointments of Justice Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, Betsy DeVos as Education secretary, and Jerry Falwell Jr., president of Liberty University, to head a higher education task force show what the Christian Right can gain.

Gorsuch is hailed as a natural successor to the late Antonin Scalia. He favors states’ rights and is deeply skeptical of the regulatory state. But whereas Scalia demonstrated hesitance to elevate religious liberty concerns over health, safety and welfare regulations, Gorsuch has favored a muscular interpretation of religious liberty, deriving from a commitment to natural law — the belief that specific, God-given rights form the basis of law.

This commitment forms the heart of the Christian Right’s legal movement and has implications for reproductive rights, physician-assisted suicide and, perhaps, the death penalty.

DeVos’ interest in school vouchers that could be used at religious schools, and how the Christian Right stands to benefit from them, is clear. While the details regarding the higher education task force are unknown, Falwell’s selection suggests intent in part to open up accreditation standards and federal qualifications for higher education institutions such as religious universities and religious law schools that have had problems in the past.

Christian leaders have long faced questions about how to preserve their educational institutions’ unique character in the face of accreditation standards and federal rules regarding non-discrimination. Some schools faced internal battles over allowing students to accept federal financial aid, since doing so might threaten a school’s ability to control its mission. As task force head, Falwell stands to lower the costs of creating such schools and to strengthen their abilities to control their Christian character.

As with the Christian Right generally, these schools’ prospects of reaching their goals was in question half a year ago. The elevation of Gorsuch, DeVos and Falwell demonstrate Trump’s recognition of the importance of empowering the Christian Right.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

June 14, 2017

National Interest: Christian History Shows Why an Islamic Reformation Is Harder Than It Sounds

This article was originally posted at The National Interest.

Five hundred years after Martin Luther unleashed his jeremiad against the Catholic Church, a question has seized the attention of the West with a special urgency: can Islam undergo its own reformation?

The terrorist attack on Iran’s national parliament and shrine to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini; the assault on security officials in Paris; the knife-wielding attack in London; the rampage against teenage concert-goers in Manchester; the assassination of Christian pilgrims outside Cairo, Egypt; the raft of executions of civilians in Iraq; the sectarian rage fueling the Syrian Civil War—it all suggests a sickness in the soul of Islam. What is needed, many argue, is a new interpretation of sacred texts that delegitimizes the advocates of terror. Even Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi—no champion of political liberalism—has called for “a religious revolution” to rescue Islam from those who would pervert its message.

The problem with this approach is that it evades the bitter historical lessons of Luther’s disruption of medieval Christianity. For all that it accomplished, Luther’s revolution failed to transform a society that had grown accustomed to burning heretics, persecuting the heterodox and treating religious dissenters as enemies of the state.

Make no mistake: Luther’s assault on the Catholic Church was, at its heart, a theological one—a debate about the authority of the Bible and the true path to spiritual salvation and peace with God. Against the dictates of popes and princes, Luther introduced a new source of authority into medieval Europe: individual conscience, guided by a fresh interpretation of scripture. “My conscience is captive to the word of God,” he declared. “I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.” This was the most radical aspect of his revolution.

Nevertheless, Luther was unable to overturn the political dogmas of European society. Perhaps the most deeply rooted belief, which is also embedded in the culture of Islam, was that religious conformity, enforced by the state, was essential to preserving order.

History seemed to support this arrangement. Not long after the conversion of the emperor Constantine to Christianity in the fourth century AD, the “church of the martyrs” adopted Rome’s rough methods for maintaining social cohesion. Dissent from religious orthodoxy was criminalized throughout the empire. The institution of the Inquisition, launched in the thirteenth century, was only the latest and most severe effort to check religious divisions. “Even if my own father were a heretic,” declared Pope Paul IV, “I would gather the wood to burn him.”

Remarkably, Luther initially repudiated the entire theocratic project and offered a stirring defense of freedom of conscience. “Worldly government has laws which extend no farther than to life and property and what is external upon earth. For over the soul God can and will let no one rule but Himself,” he wrote in 1523. “Therefore, where temporal power presumes to prescribe laws for the soul, it encroaches upon God’s government and only misleads and destroys the souls.”

Luther’s appeal, however, fell on deaf ears, even among fellow Protestants. John Calvin’s aim in Geneva, for example, was to establish a holy commonwealth—a “new Israel”—a Protestant version of Christendom. Although he attacked Catholicism for its theology of persecution, Calvin quickly devised his own. Unorthodox teachings, viewed as both a political and spiritual threat, were outlawed. A denial of Calvin’s doctrine of predestination meant banishment. The state must “prevent the deadly poison from spreading.”

Most Protestants and Catholics agreed: heresy was a threat to social peace; the safest remedy was execution. Nevertheless, Calvin’s infamous role in the trial and death of Michael Servetus, condemned and burned as a heretic in 1553, shocked the conscience of some in the Protestant community. They accused the Genevan authorities of adopting the “popish” ways of the Catholic Church. Sebastian Castellio, a French theologian and humanist, broke with Calvin over the issue and initiated one of the first debates over religious toleration in Europe. “I do not see how we can retain the name of Christian,” Castellio argued, “if we do not imitate His clemency and mercy.” Calvin did not yield an inch.

The die was cast. Like their Catholic antagonists, most Protestants viewed the political and religious realms as part of an unbroken spiritual unity. For all their theological innovation, they never imagined that the church could achieve its religious mission without the coercive arm of the state. The result, of course, was a series of religious wars in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that devastated the social fabric of Europe.

Only after this cataclysm were European leaders prepared for a second reformation: a separation of church and state that would enshrine religious freedom as a natural and inalienable right. Like Luther’s campaign, this one also originated from within the Christian community. Roger Williams, William Penn, Pierre Bayle, John Locke—virtually all of the early defenders of freedom of conscience considered the teachings of Jesus their moral lodestar. All appealed to scripture to imagine a new kind of commonwealth: a pluralistic society that guaranteed equal justice under the law, regardless of religious belief.

Still, it would take the European enlightenment—especially its American expression—to actualize this political vision. With Europe’s religious wars in mind, James Madison, the principal author of the First Amendment, insisted on a clean break from the theocratic past. “Religion or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it,” he wrote in 1785, “can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence.” It is no small thing that Madison also praised “the genius and courage of Luther,” who helped the West to understand “what is due to Caesar and what is due to God.”

Modern Islam is already undergoing something akin to Europe’s wars of religion. Its reformations—religious and political—are long overdue.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

May 26, 2017

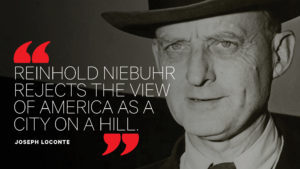

Christianity Today: Why Reinhold Niebuhr Still Haunts American Politics

This article was originally posted at Christianity Today.

A couple weeks before President Trump fired James Comey, we learned that the then-FBI director was an admirer of 20th century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Thanks to sleuthing by Gizmodo, we learned that Comey’s Twitter display name was named after the father of Christian realism and that he had written his college thesis juxtaposing Niebuhr and Jerry Falwell. A recent article at CT made a case for how Comey’s recent actions may have been influenced by the theologian:

A Christian has an obligation to seek justice, the theologian argued, and this means entering the political sphere because that is the realm where one can find the power necessary to establish whatever justice is possible in the world. Comey’s decision to work for the FBI can be understood as a way of fulfilling Niebuhr’s vision of Christianity as a defender of justice.

Comey’s not the only recent public figure influenced by the late theologian, whose admirers include people on the left and right, including Jimmy Carter, Barack Obama, John McCain, and David Brooks. But what shaped Niebuhr’s worldview?

“You really can’t understand Niebuhr’s political theology unless you appreciate the fact that his life was really bracketed by war,” said Joseph Loconte, a history professor at The King’s College in New York City.

Niebuhr was a young man during World War I and had come into his own as a “Christian Protestant public intellectual” just prior to World War II, a period in which he embraced pacifism and socialism. As totalitarian socialism and fascism took off in the 1930s, “what had become settled beliefs for him, now they’re being upended by the realities in which he finds himself,” Loconte said.

Niebuhr himself admitted that his ideas shifted not as the result of “study, but the pressure of world events,” Loconte said.

Loconte joined assistant editor Morgan Lee and editor in chief Mark Galli to discuss what Niebuhr’s theology does and does not justify, what America’s foreign policy decisions on Iraq and Syria look like through a Niebuhrian lens, and what happens when people with good intentions make decisions with unintended consequences.

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at the King’s College in New York City and the author of A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: How J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Rediscovered Faith, Friendship, and Heroism in the Cataclysm of 1914-1918.

April 27, 2017

Winners of The Tolkien Society Awards 2017 Announced

This article was originally posted at The Tolkien Society.

We are pleased to announce the winners of The Tolkien Society Awards 2017.

The Tolkien Society Awards recognise excellence in the fields of Tolkien scholarship and fandom, highlighting our long-standing charitable objective to “seek to educate the public in, and promote research into, the life and works of Professor John Ronald Reuel Tolkien CBE“.

This year, for the first time, Tolkien Society members were invited to vote on shortlists prepared by the Trustees based on nominations submitted by members of the public.

Congratulations to all winners!

The Tolkien Society Awards 2017

Best Artwork

“Finrod Crossing the Helcaraxe” by WiseNailArt

“Flight from Amon Hen” by Jay Johnstone

WINNER: “Maglor” by Elena Kukanova

Best Article

WINNER: “How J.R.R. Tolkien Found Mordor on the Western Front” by Joseph Loconte

“‘The Lord of the Rings’ as Pastoral” by Adam Roberts

“Tolkien and the aesthetics of philology” by Edmund Weiner

Best Book

WINNER: A Secret Vice, ed. Dimitra Fimi and Andy Higgins

The Elvish Writing Systems of J.R.R. Tolkien, by Matthew Coombes

The Hobbit Facsimile First Edition, by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun, ed. Verlyn Flieger

Outstanding Contribution

WINNER: John Garth

Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull

Joseph Loconte's Blog

- Joseph Loconte's profile

- 70 followers