Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 13

January 15, 2015

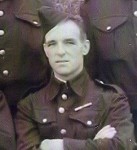

Company Sergeant Major George Mayer Symons

This is part of a series of essays about the First World War casualties commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Virginia.

Part of a Panoramic Photograph of Camp Lee, 1917

Company Sergeant Major Instructor George Symons was a pre-war regular soldier. In 1918 he was posted to the British Military Mission in the United States, where he died at Camp Lee, Virginia on 8 October 1918 during the influenza pandemic.

George Mayer Symons was born in Holborn, London in the third quarter of 1891—the seventh of the six sons and three daughters of Henry James Symons, a hansom cab driver, and Julia Mary Ann Symons (née Mayer).[1] The family later moved from Holborn to Camberwell south of the river.

George Symons enlisted as a regular soldier in late-1908, aged 18, (L/13400, Private) and joined The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment).[2] He was posted to the 2nd Battalion, which was stationed in India at Jubbelpore (Jabalpur) with a detachment at Pachmarhi Cantonment.

The 2nd Battalion sailed from India in December 1914, arriving in England in early-January 1915. It was based at Stockingford, near Nuneaton in Warwickshire as part of 86th Brigade, 29th Division—the Division was a regular formation made up of battalions that had been recalled from garrison duties across the Empire.

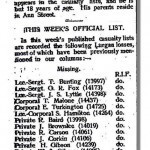

The 29th Division was ordered to the Mediterranean as part of the force that would take part in the Gallipoli campaign. Having been inspected by the King at Stretton-on-Dunsmore on 12 March, 2nd Royal Fusiliers sailed on 16 March on the SS Alaunia from Avonmouth, via Malta to Alexandria. George Symons did not, however, sail with the Battalion.

The reason for him remaining in the United Kingdom is not known—it is possible that he was attending a course of instruction—but he finally embarked for the Mediterranean sometime in August, arriving in that theatre of operations on 25 August.

By the time of his arrival 2nd Royal Fusiliers had seen considerable action. Having landed at X Beach, Cape Helles on 25 April the Battalion suffered half of its strength killed and wounded in three days’ fighting. It was engaged in major actions throughout May and by 7 June had been reduced to only 2 officers and 278 men. Having been withdrawn to Lemnos on 15 July, the Battalion returned briefly to Cape Helles before landing at Suvla on 20 August, where 86th and 87th Brigades took part in the attack on Scimitar Hill the next day; the attack, the last major attack of the Gallipoli campaign, was unsuccessful and 2nd Royal Fusiliers dug in near Chocolate Hill.[3]

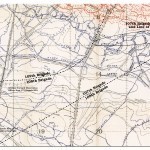

Suvla Bay and Anzac Cove, Gallipoli

It was here that Sergeant George Symons rejoined his battalion, with a large draft of officers and men that brought it up to strength for the first time since the landing in April. The Battalion was relieved and embarked for Imbros, where, although safe from the enemy, it suffered 200 more casualties from diarrhoea. The number of casualties suffered in the period since the landing in April is staggering—George Symons was lucky to have avoided becoming one of the 1,736 killed, wounded, missing or evacuated sick.[4] Following his inspection of 86th Brigade, the Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, General Sir Ian Hamilton, wrote:

‘11th September, 1915. Imbros. Ran across in the motor boat to see the 86th Brigade under Brigadier-General Percival. Went, man by man, down the lines of the four battalions—no very long walk either! These were the Royal Fusiliers (Major Guyon), Dublin Fusiliers (Colonel O’Dowda), Munster Fusiliers (Major Geddes), Lancashire Fusiliers (Major Pearson).

Shade of Napoleon—say, which would you rather not have, a skeleton Brigade or a Brigade of skeletons? This famous 86th Brigade is a combination. Were I a fat man I could not bear it, but I am as unsubstantial as they themselves. A life insurance office wouldn’t touch us; and yet—they kept on smiling!‘[5]

For two months from late September, when it returned to Suvla, the Battalion held the line near Chocolate Hill—this period included three night attacks and regular patrols. There is no way of knowing what part George Symons played in all of this or whether he was present during the flood that occurred on 26 November:

‘November 26th dawned fine, and so continued until about 5 p.m., when it began to rain. Almost at once it became a characteristic tropical downpour. In an hour there was a foot of water in the trenches. From the hills where the Turks lay a tremendous flood of water swept towards the Fusiliers’ position. The barriers reared so painfully against the Turks were swept away in a flash. In a few minutes the face of the country had changed. Into the trenches swept a pony, a mule, and three dead Turks. Several men were drowned. The whole area became a lake. The communication trenches were a swirl of muddy water. All that could be seen was an occasional tree and a muddy bank where the parados had been particularly high. The bulk of the battalion had scrambled out of the trenches, and stood about on the spots which remained above water, soaked to the skin, and at least half of them without overcoats or even rifles. The moon lit up these small knots of shivering men on little banks of mud in a waste of water. Not a shot was fired on either side. The common calamity had enforced an efficient truce.

Orders came by telephone that the battalion was to hold on to the line at all costs. Meanwhile two orderlies, Frost and James, had been sent to brigade headquarters, and had been compelled to swim most of the way. About 10 p.m. the water subsided slightly, and the men threw up rough breastworks of mud. There they lay huddled together in extreme discomfort, cut through by a piercing wind. The next day the trenches were still from 4 to 5 feet deep, and the men were forced to keep to them. The truce had ended as strangely as it had begun, and any one showing above the trenches was liable to meet the familiar fate. Captain Shaw was shot dead, Lieutenant Ormesher was mortally wounded; and with such object lessons the bitter discomforts of the trenches were made to seem preferable. In the afternoon the wind rose again. It became intensely cold. A blizzard swept the country. Men were sent back to hospital; but some of them died on the way, from exposure and exhaustion. Two of them, belonging to W Company, who shared this fate, had struggled on until they found some sort of shelter near the Salt Lake. There they had paused to rest. The younger of the two could probably have got back to camp alone, but he would not leave his comrade in the storm and darkness and snow. The next morning they were found together—frozen stiff. The younger, his arms round his companion, held a piece of broken biscuit in each frozen hand, and there were biscuit crumbs frozen into the moustache of the elder man.

Under such conditions the tacit truce was renewed. Rum and whisky were brought up to the trenches; but with the utmost difficulty. At midnight on the 27th, the wind was colder, the snow thicker. About 4 a.m. (November 28th) the commanding officer and the adjutant were the only survivors in the reserve line; and it was clear that even superhuman endurance had limits. Permission was obtained to bring the battalion back to the brigade nullah, where the ground was higher and more sheltered. There were only about 300 left in the firing line, and they were got back with great difficulty. Hardly a man could walk normally. The trench was crossed by a single plank. A few of the men were shot as they staggered across. Some failed to get back at all. Others were kicked along with merciful brutality, or they would have given up the struggle. There are few pictures in military history which equal in poignancy that of this little band who, having faced what was almost beyond the power of men, struggled back to life from the very gates of death.

By 7 a.m. the battalion had arrived at the nullah, where they were given warm food and put into blankets. The majority were taken to hospital during the day suffering either from exposure or frost-bite. The strength of the battalion was now 11 officers and 105 other ranks. A party of men, under Second Lieutenant Camies, were sent back to the Dublin Castle post to hold on to next evening. On the 29th it froze hard, and after midnight it was found that the party from another regiment who were to have relieved Second Lieutenant Camies, had lost their way. At 4 a.m. (November 30th) Camies and his men were found still at their posts, but in an almost helpless condition. Sergt.-Major Paschall was sent to take out the relieving party and bring back Camies. The outpost on return all went to hospital, and at 4 p.m. roll call showed only 10 officers and 84 other ranks (70 effective) remaining. The storm had wrought a greater havoc than any battle.’[6]

On 3 January, 2nd Royal Fusiliers finally left the peninsula and sailed for Egypt; by March 1916 it was in France.

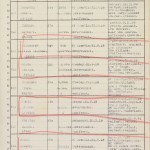

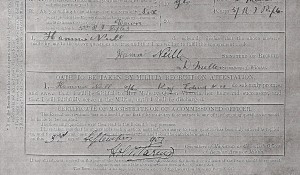

It is impossible to say when Sergeant Symons left the 2nd Battalion and, therefore, what experience he had of the Battalion’s actions in France. What is known is that at some time in late-1917 he was detached for duty with the Army Gymnastic Staff (AGS) as a physical training and bayonet fighting instructor, allocated a new regimental number (1125) and then promoted to Company Sergeant Major Instructor.[7] He is likely to have been a regimental physical training instructor and an instructor at a school before applying, or being selected, to join the AGS.

Soldiers on a Physical and Bayonet Training Course for Unit Instructors

The AGS had been formed in 1860 in order to provide a professionally trained cadre of instructors who could develop a more rigorous physical training programme for the Army, and to promote the organisation of sport. It was an establishment, not a corps, and men were attached to the AGS from their parent regiments. Like the rest of the Army, the AGS expanded to cater for the demands of the much bigger wartime Army. At the outbreak of war the Army actively recruited civilian gymnastic and physical training instructors, who were sent to Aldershot—to the School of Physical Training—where they were assessed. Successful completion of this assessment resulted in their appointment as an Acting Sergeant Instructor (or Acting Quartermaster Sergeant or Company Sergeant Major Instructor depending on their level of expertise) and posting to a training establishment or physical training school. Command Schools of Physical and Bayonet Training were established in 1916 to train unit instructors, to train and assess potential AGS instructors from men already serving in the Army, and to provide refresher training. 1916 also saw the establishment of schools in France to support the British Expeditionary Force.[8]

By July 1918, Company Sergeant Major Instructor Symons was held on the supernumerary strength of the 5th (Reserve) Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers and had been posted to the British Military Mission, for employment at one of the United States Army training camps. The training component of the British Military Mission numbered 261 officers and 226 NCOs spread across the training establishment—it was highly regarded and is credited, with its French equivalent, of being pivotal to the successful expansion of the United States Army in 1917 and 1918.

The AGS had provided instructors to the training mission in the United States since October 1917, when 25 officers and NCO instructors arrived and were assigned to the divisions then training.[9] Amongst a contingent of officers and men that sailed from Southampton on RMS Olympic on 27 July 1918, destined for the British Military Mission, was Company Sergeant Major Instructor George Symons.[10] He arrived in New York on 1 August. Also in this contingent of instructors was Captain Harry Daniels VC, MC—he had earned his awards as a company sergeant major with 2nd Battalion, The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) before being commissioned and attached to the AGS.

Symons’ new place of duty was Camp Lee, Virginia. Camp Lee—named after General Robert E. Lee—had been established on farmland acquired by the War Department east of Petersburg in Prince George County soon after the United States entered the war. It was one of 32 cantonments built to cater for 16 National Army and 16 National Guard divisions. Initially, Camp Lee was the home to the 80th ‘Blue Ridge’ Division—recruited from New Jersey, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, and District of Columbia—which embarked for France in June 1918. Camp Lee then became a training camp for replacements; its major units were the Infantry Replacement and Training Camp, 155th Depot Brigade, one of two Veterinary Training Schools, a school for bakers and cooks, and one of the five Central Officers’ Training Schools for infantry officers.

Recruits at Camp Lee exercising with a medicine ball

Company Sergeant Major Instructor Symons arrived at Camp Lee in early August 1918. A month later influenza arrived. The first case was reported on 13 September and the incidence of cases increased rapidly. The camp hospital was quickly overwhelmed and rooms in barracks, and later whole barracks, were set aside for the confinement and treatment of the milder cases. At the same time, blocks of barrack buildings ½ mile from the camp hospital were set up as an annex to the hospital. Quarantine restrictions were imposed to reduce contact with the civilian population, although by then the disease had spread to Richmond.[11] [12] The rate of new infections peaked in Camp Lee in the first week of October; by noon on 3 October 6,449 cases had been reported, resulting in 167 deaths.

Hospital Staff, Camp Lee

George Symons was one of those struck down by the disease during this period. He died at the camp hospital on Tuesday 8 October 1918, one of 28 men to die in that 24 hour period.[13]

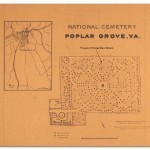

Poplar Grove National Cemetery

He was buried at Poplar Grove National Cemetery, Petersburg, one of seven burials in 1918.[16] Poplar Grove National Cemetery was established as a burial site for United States soldiers killed during the Siege of Petersburg. Confederate soldiers were buried at Blandford Church Cemetery. The work to clear the battlefield around Petersburg began in 1866 and was completed by 30 June 1869, when the burial corps that had carried out the work was disbanded. By then 6,178 Union and 32 Confederate soldiers, and five civilians had been buried in the cemetery; only 2,139 are identified. Since then there have been a further 32 Civil War burials (29 in 1931 and three in 2003) and 61 other burials between 1896 and 1957, when the cemetery was closed to non-Civil War interments.[15] George Symons is buried in grave 5596. It is in section C, in a radial row of graves established between 1896 and 1933 in the walkway in the centre of section C; it begins to the right of the gun monument and leads north-east. His grave lies between unknown soldiers in graves 3013 and 3014.

Unfortunately, his grave marker incorrectly records his number, name and date of death; it should read ‘L/13400’ ‘George M Symons’ and give his date of death as ‘8 October 1918’.

The marker for the grave of Company Sergeant Major George Mayer Symons

Acknowledgement:

Fort Lee Archive for the photographs of Camp Lee.

Sources:

Anwaerter, J; Curry, G W. (2006). Cultural Landscape Report for Poplar Grove National Cemetery. Boston: Olmstead Center for Landscape Preservation.

Campbell, J D. (December 2003). ‘The Army Isn’t All Work’: Physical Culture in the Evolution of the British Army, 1860-1920. The Graduate School, The University of Maine. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 185.

Hamilton, I. (1920). Gallipoli Diary. Volume 2. New York: George H. Doran & Co.

O’Neill, H C. (1922). The Royal Fusiliers in the Great War. London: William Heinemann.

Camp Surgeon, Camp Lee, VA. (7 November 1918). Report on the Influenza and Pneumonia Epidemic. RG 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army). National Archives.

1. (Back) Henry James Symons (born third quarter 1852) and Julia Mary Ann Mayer (born third quarter 1857) married on 6 September 1876 at Clarkenwell. In addition to George Mayer, they had eight children: Helen Amelia Mary (1877), Selina Julia (14 February 1881), Alfred James (1883), Richard Charles (1885), Arthur Thomas (1887), Albert James (1889), Ernest William (1895), Marian Louise (1897). Selina Julia, Alfred James, Richard Charles, and Arthur Thomas were baptised together on 27 May 1988.

2. (Back) The ‘L’ prefix on his regimental number indicates such a regular enlistment.

3. (Back) The summary of the Battalion’s actions is taken from the wartime history of the Regiment: O’Neill, H C. (1922). The Royal Fusiliers in the Great War. London: William Heinemann.

4. (Back) 19 officers and 260 other ranks were killed; 40 officers and 914 other ranks were wounded; 24 officers and 376 other ranks were evacuated sick and 7 officers and 96 other ranks were missing.

5. (Back) Hamilton, I. (1920). Gallipoli Diary. Volume 2. New York: George H. Doran & Co.

6. (Back) O’Neill. Op. Cit. pp 105-108.

7. (Back) This date is derived from an analysis of other records. In addition, the absent voter list for 1919 (compiled from information submitted in 1918) records him as living at 269 Beresford Street, Woolwich and as being in the Army Gymnastic Staff—1125, Company Sergeant Major.

8. (Back) An excellent history of the Army Gymnastic Staff in the war may be found here: Campbell, J D. (December 2003). ‘The Army Isn’t All Work’: Physical Culture in the Evolution of the British Army, 1860-1920. The Graduate School, The University of Maine. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 185.

9. (Back) Campbell. Op. Cit. p 212.

10. (Back) The other instructors in this contingent were:

1055 Company Sergeant Major Instructor George Henry Anderson, The East Surrey Regiment

38153 Sergeant Instructor Thomas Coburn, The Norfolk Regiment (formerly The King’s (Liverpool Regiment))

9074 Company Sergeant Major Instructor Charles Alfred Donnithorne DCM, The Border Regiment

8291 Company Sergeant Major Instructor Arthur Gosling, The Cheshire Regiment

9607 Company Sergeant Major Instructor John William Husher DCM, The Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment)

TR/8/11617 Sergeant Instructor Albert Clement Locker, The Devonshire Regiment (formerly 940, The Royal Warwickshire Regiment)

1727 Company Sergeant Major Instructor Daniel McConville, Army Gymnastic Staff (formerly 10599 The Gordon Highlanders) 7/17

8721 Quartermaster Sergeant Instructor John Thomas Murray, The South Wales Borderers

38076 Sergeant Instructor Walter Rushworth, The Norfolk Regiment

38009 Sergeant Instructor Stanley Frederick Smith, The Norfolk Regiment

10530 Company Sergeant Major Instructor William Robin Thomas DCM, The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

1147 Company Sergeant Major Instructor William Wilcox, Army Gymnastic Staff (formerly 8836, The South Wales Borderers)

1658 Sergeant Instructor Arthur James Wilkinson, Army Gymnastic Staff (formerly 10841, Coldstream Guards)

34227 Sergeant Instructor Percy Hutchings, The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

A number of other instructors in that contingent have not been positively identified (it is believed that they include some Canadian NCO instructors): William Denton, William Edwards, John Thomas Harper, James Hughes, Donald McDonald, Frederick Preston, Charles Price, James Fred Seaton, Henry Duncan Sheldon, Alfred V Smail, (?) Smith.

In addition to Captain H Daniels VC, MC, there were 29 officers on board: Brigadier General L R Kenyon, Director of Munitions Inspection; Captain C E Ashby MC, The London Regiment—an officer of the British Military Staff in Washington DC; 23 other officers of the British Military Mission (including two Canadians, Captain L Kirk-Greene, 5th Battalion Canadian Mounted Rifles, and Lieutenant John McWatters, Canadian Infantry); three officers of the British Naval Mission; and an officer returning to the British West Indies from sick leave. Most of the instructor officers were appointed as at 19 July in London Gazette 26 September. Issue 30920, pp 11405-406 (the officers appointed to the British Military Mission on 12 July in the same Gazette (and three Canadian instructor officers) had arrived in the United States on RMS Mauritania a week earlier).

11. (Back) Camp Surgeon, Camp Lee, VA. (7 November 1918). Report on the Influenza and Pneumonia Epidemic. RG 112, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General (Army). National Archives.

12. (Back) Here you can read more about the influenza pandemic in Camp Lee and Richmond.

13. (Back) In the report produced by the Camp Surgeon at Camp Lee the strength of the command was reported as 49,300 all ranks. Between 13 September and 7 November 1918, there were 11,637 cases of influenza and 1,960 cases of pneumonia, resulting in 674 deaths. In a smaller outbreak in December 692 cases were reported, of whom four died.

14. (Back) It is acknowledged that some of the Civil War soldiers buried here may not have been United States citizens.

15. (Back) Anwaerter, J; Curry, G W. (2006). Cultural Landscape Report for Poplar Grove National Cemetery. Boston: Olmstead Center for Landscape Preservation.

16. (Back) The burials in 1918 were all First World War casualties:

Private Charlie Favors, 155th Depot Brigade, Camp Lee; died on 16 March 1918; C5594

Private Arthur H. Heward, 155th Depot Brigade, Camp Lee; died on 12 June 1918; C5595

Private Mike Kosich, 155th Depot Brigade, Camp Lee; died on 9 January 1918; C5593

Captain Arthur L. Lynn, 8th Cavalry; died at Presidio, Texas on 11 October 1918; C5598

Private Stanley Urbanowicz, 3rd Camp Development Battalion, Camp Lee; died on 5 October 1918 C5597

Private Frank D. Williams, 465th Motor Truck Company; died in France 26 September 1918 and buried at American Cemetery 4, Neufchateau. Reinterred at Poplar Grove National Cemetery C3447A

January 8, 2015

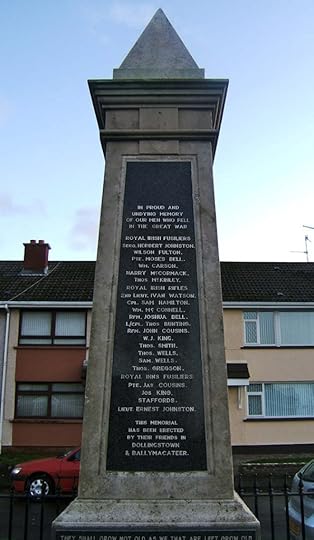

The Evolution of the Regular and Service Battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918 – Part 6, The 9th (Service) Battalion (County Armagh)/9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion.

This essay describes the evolution of the 9th (Service) Battalion (County Armagh)/9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion. The background to this essay may be found here.

This material is taken, from Blacker’s Boys Appendix 6; it has been summarised and is updated here based on new information received since publication.

‘B’ Company, 9th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (County Armagh) in early-1915

The First to Enlist

The first men to enlist into the County Armagh Battalion of the 2nd Brigade of the Ulster Division did so over six days beginning on 15 September 1914. Uniquely in the history of the Regiment, the men of this first draft were all Protestant and many were members of the Ulster Volunteer Force. They were mainly from County Armagh, with the majority from the north of the county around Lurgan and Portadown. There were some men from Counties Cavan and Monaghan, the other traditional recruiting areas for Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), and some from Counties Down and Antrim, and from Belfast.

The reported strength of the new battalion, when it formed at Clandeboye Camp on 21 September 1914, was 842 men. A little over forty more joined over the next few days before regimental numbers were issued. Of this first batch of recruits, the first to enlist in the County Armagh Battalion, 781 men have been identified by name.[1]

Of the known men, 652 sailed with the Battalion for France in October 1915. For a further 41 men there is no record of when they deployed to France and joined the Battalion.[2]

Enlistments between October 1914 and July 1915

Following the arrival of the first volunteers at Clandeboye, recruiting continued apace. Recruits joined the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers at Clandeboye directly until the formation of the depot company, which became responsible for the basic training of recruits after the Battalion left for Seaford in July 1915. This responsibility passed to the 10th (Reserve) Battalion when it was formed in September 1915. In general, men who enlisted before the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers moved to Seaford embarked for France with the Battalion in October 1915. Those who enlisted after July 1915 joined later as reinforcements from the 10th (Reserve) Battalion.

The absence of complete records makes it impossible to determine exactly the number of men who enlisted into the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers and the number discharged under King’s Regulations or transferred in the months that followed their enlistment. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify 440 men who enlisted between October 1914 and July 1915 and who joined the Battalion.

Of these, 17 men were discharged or transferred; 358 men are known to have embarked with the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers in October 1915; and 65 men served with the Battalion in France but they joined sometime after the main body had arrived.

In summary, the lowest estimate of enlistments between September 1914 and July 1915 is 1,282 men—1,221 have been identified by name. Of these, 1,010 are known to have landed in France with 36th (Ulster) Division in October 1915, with a further 106 men arriving in France sometime later.[3] The remainder were discharged, or transferred, or were posted elsewhere.

It is noteworthy that 332 of these men, a third, were killed in action, died of wounds, or died of illness, injury or accident.

Reinforcement Drafts

Following a period of familiarisation and training, the Battalion took its turn in the line north of Albert throughout the first half of 1916. 36th (Ulster) Division spent most of this time in two sectors astride the River Ancre with the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, and the other battalions of 108th Brigade, in the northern sector at Hamel.

Until the attack at Hamel on 1 July 1916, small drafts and individual reinforcements arrived from the 10th (Reserve) Battalion. These new men had enlisted in the latter half of 1915 and early 1916 and were from the same Ulster Protestant background as the Battalion’s original members. In addition to the large reinforcement drafts detailed below, as the war progressed the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers also received men from all of the other battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) as they filtered through the reinforcement cycle. These men were a mix of regular soldiers, men recalled from the Army Reserve, men who had enlisted as Special Reservists, and wartime volunteers. They also represented both Catholic and Protestant communities and, although mainly from County Armagh, they came from all over Ireland. They also reflected the drafts from English regiments that had been transferred to other battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), as explained in other essays. Many of those who had seen previous service had recovered from wounds, injury or sickness.

The first reinforcement of English soldiers took place after the attack on 1 July 1916. The attack had destroyed this fine battalion—it suffered 541 killed and wounded—and the 10th (Reserve) Battalion could not bring it fully up to strength again. On 8 August 1916 a draft of eighty-eight men of The Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment) arrived.[4] This was followed by a draft of 103 men, mostly of The London Regiment, on 26 November.[5] The final body of reinforcements to arrive in 1916 comprised 89 men of The Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) that arrived on 12 December.

Corporal (later Company Quartermaster Sergeant) F MacMahon

After the attack on 1 July 1916, and having been reconstituted, 36th (Ulster) Division moved north to Ypres, where it went into the line near Wytschaete. The 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers suffered a trickle of casualties as it held the line and raided along the River Douve and at Spanbroekmolen. It was not until the attack on 16 August 1917, the Battle of Langemarck, that the Battalion was again nearly destroyed and in need of massive reinforcement—on that occasion it suffered 456 officers and men killed, wounded and captured.

In September the largest draft to join the Battalion since its formation arrived. It comprised over 570 men compulsorily transferred for duty as infantry from the disbanded 2nd North Irish Horse, X Corps Cavalry Regiment. The majority of the Battalion now comprised the men of the North Irish Horse and it was duly renamed the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion.

The final action of note in 1917 was the attack at Moeuvres during the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, in which the Battalion suffered 89 all ranks killed and wounded.

Following the reorganisation of the infantry of the British Expeditionary Force in early 1918, the 7th/8th Royal Irish Fusiliers was disbanded. The war diary of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers records that a draft from the disbanded battalion arrived comprising 213 men.[6]

Sergeant F S Homersham DCM, MM

In late-March and early-April 1918 the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers suffered grievously for the third time being all but destroyed in the retreat from St Quentin and at Ypres. At this time the reserve battalions of the Irish regiments were reorganised compounding the problem of the lack of Irish reinforcements. The fourth draft of English soldiers was the second from The London Regiment and comprised 122 men. The Battalion also received a small draft of 14 men transferred from The Royal Irish Rifles.

On 8 June the Battalion was brought closer to its full strength by a large draft of 186 men, most of whom had been compulsorily transferred for duty as infantry from the Army Service Corps (105) and the Army Veterinary Corps (68).

The final phase of the war began for the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers with an attack in August 1918 north-west of Bailleul and the Battalion was then in almost constant action until 26 October. In this period it received its final draft of reinforcements—137 men transferred from The Royal Irish Rifles.

‘B’ Company, 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), Mouscron, November 1918

Details on each of these drafts may be found here: Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918 – Reinforcement Drafts

Back to ‘The Evolution of the Regular and Service Battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918‘ main page.

1. (Back) Detail about the enlistments into the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers between September 1914 and July 1915 may be found here.

2. (Back) This is based on an analysis of medal rolls and medal index cards. The records may be incomplete. Most of these men will have arrived in France by early 1916.

3. (Back) The Battalion’s war diary reported that it landed in France with a strength of 995 other ranks; the discrepancy is a small one (15 men) and likely to be explained by men on the advance party or detached for duty elsewhere.

4. (Back) The Battalion’s war diary reported it as being 90 men strong.

5. (Back) The Battalion’s war diary records that the full draft was made up of ‘34 Irishmen, 102 Englishmen and 1 Russian’. It is known that the ‘Russian’ was from The London Regiment.

6. (Back) The war diary of the 7th/8th Royal Irish Fusiliers records it being 220 men strong.

January 4, 2015

My Family in the First World War – Part 5: John Palmer Bowes

504226 Private John Palmer Bowes

Private John Palmer Bowes. 2nd Canadian Division Mechanical Transport Company, Canadian Army Service Corps.

John Palmer Bowes was my wife’s maternal great-grandfather. He was born at Oakwood in the township of Mariposa[1] in Ontario, Canada on 29 March 1869, the second youngest of the five children of Emmanuel and Elizabeth Bowes.[2] The family moved to Kansas City, Missouri in 1890, where Emmanuel re-established his business as a grocer. John later moved to St Louis and became a motor mechanic. In 1901 he married Emma Leming (née Young), a widow with three children from her first marriage.[3] Their son, Emanuel Adrian, was born at their home at 4120 Blair Avenue, St Louis on 12 December 1906.

By 1910 John was working as a mechanic for the Underwriter Salvage Corps. The Salvage Corps was created in 1874—it worked alongside the city’s fire patrols and would enter burning buildings to remove valuable items before they were destroyed. Sometime in 1914 John decided to move his family back to Canada. They settled in Edmonton, where they occupied a house at 11257 Jasper Avenue West, and where John went to work as a mechanic for Edmonton Fire Department.

John Palmer Bowes enlisted for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force on 28 February 1916, declaring his year of birth as 1878—shaving nine years off his age, making him just under 38 and of military age. He joined the Canadian Corps of Royal Engineers (504226, Sapper) and, after a period of initial training, he sailed for England on the RMS Baltic on 21 May 1916, arriving on 30 May. He immediately joined the Engineers Training Depot at Shorncliffe in Kent. The first Canadians had arrived in the spring of 1915 and the Canadian Training Division was based here in five large barracks.[4]

RMS Baltic

After training at Shorncliffe for three months his age began to tell and, in early September 1916, he reported sick with muscle pain, and a painful and swollen knee (he had also suffered from rheumatism), at which time he also declared his true age. As a result, a medical board assessed that he was unfit for ‘general service’ but that he was suitable for ‘permanent base duty’, at home and abroad.[5] He was posted to the strength of the Canadian Casualty Assembly Centre at Monks Horton, an administrative holding unit for hospitalised soldiers and those not fully fit, from 7 September 1916 and attached to the Engineers Training Depot for duty.

In mid-1917, however, his level of fitness and his previous employment as a mechanic resulted in his transfer to the Canadian Army Service Corps on 26 July. The Army Service Corps was responsible for transportation and supply services and, with an increasing reliance on motor vehicles, needed suitably trained and experienced men. Read more about the Canadian Army Service Corps.

Eastwell Manor

At about 8.30pm on 1 October 1917, while walking back to barracks, Private Bowes, as he was now, was hit by a car. He was admitted to Moore Barracks Canadian Hospital,[6] Shorncliffe—X-rays on 2 October 1916 showed that he had not, as first thought, broken his spine, ribs or shoulder. He was sent to a convalescent home at Eastwell Park at Ashford[7] and, after treatment and rest, he was discharged on 24 October. While undergoing his convalescence he was posted to the Canadian Army Service Corps Depot at Bramshott in Hampshire, which he joined after his convalescence.

At a medical board on 23 November he was again passed fit for ‘permanent base duty’—based on his age and his old knee injury—but on 8 December 1917 Private Bowes again joined the Canadian Army Service Corps Base Depot at Shorncliffe and six days later was assigned to a draft of men to be sent to France. He arrived in France on 15 December and after a week at the General Base Depot he was posted to the Canadian Corps Supply Column on 22 December as a reinforcement. He remained with that unit until 12 March 1918, when he was posted to the Canadian 2nd Division Supply Column. A month later, he joined the Canadian 2nd Division Mechanical Transport Company on 14 April. It was with this unit that he would spend the rest of the war.

‘Battle Flash’ of 2nd Canadian Division MT Company

The 2nd Canadian Division had been raised in late-1914 and it sailed for England in May 1915. After completing a period of training at Shorncliffe it arrived in France over the period 15-18 September 1915, at which time the Canadian Corps was formed. The Canadian Corps was one of the most highly regarded fighting formations of the war. By the time Private Bowes arrived in France in the spring of 1918, it comprised four infantry divisions. From June 1917, it was commanded by a Canadian officer—Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Currie, one of the Allies’ most effective corps commanders.[8]

Private Bowes first major action was the Battle of Amiens, which began on 8 August 1918 when the Canadian Corps attacked alongside an Australian Corps in the opening offensive of the final phase of the war. Read more about the Battle of Amiens.

There then followed the series of Allied attacks known as the ‘Hundred Days Offensive’ that led ultimately to the Armistice. The 2nd Canadian Division’s final actions were the Second Battle of Cambrai, 8-10 October 1918, and the Pursuit to Mons in the last days of the war. John Palmer Bowes finished his war in Belgium near Frameries, south of Mons.

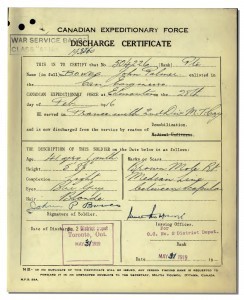

Discharge Certificate for Private John Palmer Bowes

Following the Armistice the Canadian Corps became part of the Army of Occupation and Private Bowes was stationed near Bonn in the Rhineland until the Canadians returned to Belgium at the end of January 1919. The 2nd Division was then based in the area of Auvelais, ten miles west of Namur, but it would be some months before the Canadian Divisions were finally disbanded.

Private Bowes returned to England on 29 April 1919 and sailed for Canada on the RMS Aquitania on 18 May, arriving in Halifax, Nova Scotia on 25 May. On his return to Canada, he was taken on strength at No. 2 District Depot, Toronto from which he was discharged on 31 May 1919 and he rejoined his family in Edmonton. Read more about repatriation and demobilization.

The family remained in Edmonton for the next decade, and John returned to work as a mechanic for Edmonton Fire Department. Sometime before 1930 the family moved back to St Louis, where John continued to work as a mechanic and later as a chauffeur and truck driver. In his later years, he became estranged from his wife and, from June 1939, he spent his final years being cared for by the Little Sisters of the Poor at their residence for the needy elderly at North Florissant Avenue in the St Louis Place neighbourhood; he died there on 10 August 1947, aged 78. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery, St Louis on 12 August 1947. His grave is unmarked.

Calvary Cemetery, St Louis

Acknowledgment:

Archive of the Little Sisiters of the Poor, St Louis.

Ian Boyle, Simplon Postcards, for the image of the RMS Baltic.

1. (Back) Now part of Kawartha Lakes, Ontario.

2. (Back) His father, Emmanuel A Bowes, a grocer, was born on 19 January 1835 in Ontario, Canada. His mother, Elizabeth Horsley, was born on 5 April 1838 in England. Emmanuel died on 8 March 1903 and Elizabeth died on 7 August 1918—they were buried together in Elmwood Cemetery, Kansas City.

3. (Back) Emma Young was born on 28 July 1865 in Pennsylvania, the daughter of a German immigrant father. She married William Bruce Leming on 20 December 1884 and had three children: Frank Rust (born 24 June 1886), Irene May (born around 1888), and (Daniel) Bruce (born 12 July 1891). William Leming died in 1899.

4. (Back) Ross Barracks, Somerset Barracks, Napier Barracks, Moore Barracks and Risborough Barracks.

5. (Back) The difficulty in employing overage men who were not fully fit (and, indeed, underage boys) placed a considerable strain on the Canadian Expeditionary Force depots in England. On 20 September 1916, Colonel Herbert A. Bruce produced a report on the Canadian Army Medical Service, which studied the fitness of the CEF after 31 July 1916. His findings were critical of the medal examinations being conducted at enlistment. As regards unfit men, he wrote: ‘Unfits in England are a great bother. They take the places on base duty of men who have been at the front and have a prior claim on any soft jobs available. Others clog up the hospitals, increasing the strain on the already overtaxed medical services.’ He wrote about overage men: ‘In the last four months we have had over 1,000 recommended for permanent base duty from over age, with an average age of 49 to 50 years for each man. It is a common occurrence for the men, when questioned as to their given age when enlisted, to make a statement that they gave their true age as 54 or 55 years, as the case may be, and the medical officer said they would call him 41 or 42 years. In one case he was informed by the soldier that, on enlistment, the recruit on giving his proper age was told to run around the block, think over his age, and come back again. …One of the over-age men was found to be 72 years old.’

6. (Back) Later renamed No. 11 General Hospital.

7. (Back) Eastwell Manor is a large country house in Eastwell Park near Ashford in Kent. It was built between 1540 and 1550 for Sir Thomas Moyle—a commissioner for Henry VIII in the dissolution of the monasteries, and speaker of the House of Commons. The building was added to in the 18th and 19thC. It was the home of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the second son of Queen Victoria, until 1893. During the First World War it was a convalescent hospital, largely for Canadian troops. After a fire in the 1920s it was rebuilt and it is now a country house hotel and spa.

8. (Back) General Sir Arthur (William) Currie GCMG, KCB was born on 5 December 1875 in Ontario. He served with 5th Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery from 1897, being commissioned in 1900. In 1909 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and was given command of the Regiment. In October 1913 he was given command of 50th Regiment (Gordon Highlanders of Canada). Command of 2nd Canadian Brigade followed on the outbreak of war and his sure handling of the Brigade resulted in him being made a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB), his promotion to major general and command of the 1st Canadian Division. He was instrumental in the success of the Canadians at Vimy Ridge in April 1917, for which he was knighted, being appointed KCMG. He was promoted to lieutenant general on 9 June and given command of the Canadian Corps. He was made KCB in 1918 and GCMG in 1919. In 1919, he became the first Canadian promoted to the rank of General. He died on 30 November 1933, aged 57, and was interred in Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal.

December 22, 2014

HMS Warrior

This is part of a series of essays about the First World War casualties commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Virginia.

Private Elmer Robert Darrock, Royal Marine Light Infantry

Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class Harold Gurney Davis, Royal Naval Reserve

Deck Hand William Kelly, Mercantile Marine Reserve

Deck Hand Joseph Prowse, Mercantile Marine Reserve

Private James Schofield, Royal Marine Light Infantry

Writer 3rd Class Thomas Henry Symons, Royal Navy

Deck Hand Herbert Thomas, Mercantile Marine Reserve

HMS Warrior

If the society pages of the Washington Post, the Washington Herald and the Washington Times are to be believed, HMS Warrior[1] provided a focus for some of the social whirl in Washington DC during the final months of the war. The influenza pandemic curtailed many of the normal opportunities for social gatherings but, in the words of one commentator, writing about the reception given for Sir Eric Geddes, then the First Lord of the Admiralty, who was visiting the United States:

‘A more impressive or significant party than the reception given to the distinguished foreign visitors could not be wished for than that aboard the British flagship Warrior, given by Vice Admiral and Lady Grant, who made the trip across on board some months ago. The Warrior is their Washington home and a charming one it is, out in the historic Potomac. It is by special permission of the admiralty that Vice Admiral Grant is accompanied on the Warrior by Lady Grant. The party on Wednesday was the first assembling of society this season, and it was not only a brilliant occasion but a happy reunion. The soft, familiar blue of the French uniforms, with a dash of red here and there, the gay trappings of our own and British, Italian and Canadian officers, both of army and navy, made a significant scene on decks, as well as a picturesque bit of colour against the somber gray of the sturdy warship.’[2]

The Daughters of the American Revolution Aboard HMS Warrior

The society pages did not, however, comment upon the importance of the presence of Vice Admiral Sir Lowther Grant, who had been in Washington since March. His primary concern was the protection of convoys in the north-west Atlantic and he sought greater participation by the United States Navy in anti-submarine operations. Sir Eric Geddes’ visit followed an increase in U-Boat activity in August and September 1918—although the dire warnings about a further increase in such attacks proved unfounded—and he hoped to push the United States into a quicker completion of its warship building programme, which was many months behind schedule. The presence in Washington DC of Vice Admiral Grant, Commander-in-Chief on the North American and West Indies Station, and his flagship HMS Warrior, was eminently sensible, given the complexity of the relationship between the Admiralty (and its policy of maintaining the effort in home waters), the Canadians and the United States.

Warrior, a luxurious steam yacht, designed by the Scottish naval architect George Lennox Watson and built for Frederick W. Vanderbilt, a scion of the Vanderbilt railway and shipping empire in 1904. In early 1914, after she had been grounded at the mouth of the River Magdalena on the Colombian coast, the 1,266-ton, 284 feet-long yacht was bought by Harry Payne Whitney. In early 1915, Whitney, a philanthropist businessman and sportsman, and Vanderbilt’s nephew by marriage, sold the ship to his brother-in-law, Alfred G. Vanderbilt, who renamed her Wayfarer. He did not own the ship for long—Alfred Vanderbilt was drowned when RMS Lusitania was sunk by U-20 on 7 May 1915—and the yacht was bought from his estate in 1916 by Alexander S. Cochran. Cochran, a wealthy philanthropist and yachtsman, restored her original name, Warrior.[3] His period of ownership was not wholly happy either—Warrior ran aground on Fishers Island, Long Island Sound in July 1916. This is a short video of Warrior taken in the 1930s (note that the design number is wrong, Warrior was ‘424’):

Warrior was hired by the Admiralty in February 1917 for service on the North American and West Indies Station and, armed with two 12-pounder 3-inch naval guns, served as HMS Warrior, an armed yacht with pendant number 090.[4] Her first deployment was to the Caribbean in July 1917.

The crew was a mix of Royal Navy, Royal Naval Reserve, Mercantile Marine Reserve and Royal Marine Light Infantry. The Royal Naval Reserve comprised men who were professional seamen of the Merchant Navy and fishing fleets and who undertook a month’s training every two years, primarily in gunnery. The Mercantile Marine Reserve comprised merchant seamen who served under a special wartime Naval engagement and were subject to Admiralty regulations and the Naval Discipline Act.[5] The Royal Marine Light Infantry (amalgamated in 1923 with the Royal Marine Artillery to form the Royal Marines), were shipborne infantry responsible for conducting boarding parties and for ship security.

HMS Warrior spent the first part of her war in the Caribbean. She arrived there from Bermuda in July 1917 spending most of the next six months in the Lesser Antilles but also visiting Jamaica and Belize. On 19 January 1918 she sailed from St Lucia back to Bermuda, where she arrived on 23 January. The next three weeks were spent here, cleaning and preparing the yacht for her role as the flagship of Vice Admiral Sir Lowther Grant KCB.

Vice Admiral Grant had been appointed Commander-in-Chief on the North American and West Indies Station on 7 January and had joined his flagship, HMS Highflyer, at Devonport on 23 January 1918. After an uneventful journey via the Azores, HMS Highflyer arrived in Bermuda on 10 February. Having completed the transfer of equipment and personnel to the new flagship, over the next few days HMS Warrior was readied for sea. Vice Admiral Grant raised his flag on the morning of 16 February 1918 and at noon HMS Warrior sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

HMS Warrior arrived at Halifax three days later on 19 February where she remained until she sailed for Washington on 23 March. She sailed down the eastern seaboard, into the Chesapeake Bay and up the Potomac River, coming alongside at Washington on the morning of 27 March; she would remain berthed at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia rivers at Washington Barracks[6] as Vice Admiral Grant’s flagship for the rest of the war, and the residence for him and his wife, who had accompanied him to Washington.

Launching the Daughters of the American Revolution Floral Wreath

In addition to the routine of ships maintenance, the yacht’s compliment enjoyed liberty in Washington and took part in a number of ceremonies and social functions in support of Vice Admiral Grant’s role, many of which were hosted by his wife. The first large event of note was on Memorial Day, Thursday 30 May.[7] The commemoration in 1918 was unusual. A ceremony planned to commemorate those who died in the sinking of RMS Lusitania was widened to include all of those who had died up to that date in the war. It began on board HMS Warrior and then moved to the USS Wicomico, a yard tug; it was from the latter that large wreaths were ‘launched down the historic Potomac River and above which the ‘Union Jack’ had been raised’. The ceremony also featured ‘a bevy of American girls, flanked by a group of British jack tars, and hydroplanes circling above dropping flowers on the scene’.[8] Thereafter, the receptions and social engagements hosted onboard were a regular feature in the local press reports.

Against this backdrop of strategic military debate and social engagement, the first cases of influenza were observed in Washington DC in August 1918. They were initially confined to the naval station and local army camps but by the end of September civilian cases were increasing and, in early October, schools were closed and four emergency relief stations and an emergency hospital were opened (although the city’s Black population was not similarly catered for until the end of the month). By early November the epidemic was seen to be in decline and restrictions were lifted but cases increased again in December. The epidemic continued until February 1919 by which time there had been over 33,000 cases and 2,895 deaths. It was ‘one of the more devastating epidemics in the nation’.[9]

The crew of HMS Warrior, 30 May 1918

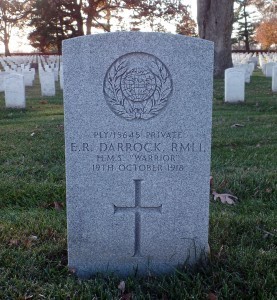

The Original Grave Marker for Private Elmer Robert Darrock

The log of HMS Warrior records 46 discharges to hospital between 6 August and 22 December—a substantial majority of her crew.[10] [11] Seven of these men succumbed to influenza, or to complications related to it in the New Naval Hospital at 23rd and E Streets NW.[12] They were buried in Arlington National Cemetery—the burial parties in all cases were provided by HMS Warrior’s crew.[13] With the exception of Harold Gurney Davis, all of the men are buried in Section 17, on the western side of the cemetery near the Confederate Memorial; Davis is buried nearby in Section 15A. The graves were originally marked with similar headstones to those used through Arlington National Cemetery but they have recently been replaced with Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones.

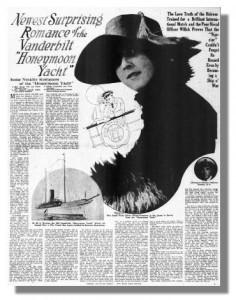

Romance on HMS Warrior

The final remarks about HMS Warrior reflect, again, the impact that the ship, the Admiral and his wife, and her crew had on Washington’s social scene. Lady Grant had left Washington soon after the Armistice but the romance that she had helped ignite between Lieutenant Charles Fellowes-Gordon and Miss Sara Price Collier, a cousin of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy and future President Franklin D. Roosevelt dominated the society press reports in November and December 1918. After the turn of the New Year, a series of functions were held to say goodbye to HMS Warrior’s crew, beginning on 3 January 1919 with a dance held by the crew at a venue ashore (the link to the right will take you to a typical society column from this period).

Sadly, three days later Deck Hand Joseph Prowse succumbed to influenza; he was the final crew-member to die. He was buried on 8 January and a little over a week later, on 17 January 1919, almost 10 months after her arrival, HMS Warrior left Washington DC.[14] Admiral Sir Lowther Grant (he had been promoted on 1 September 1918) sailed in HMS Warrior as far as New York before crossing the Atlantic on the RMS Adriatic, with departing senior members of the British Military Mission.

PLY/15645 Private Elmer Robert Darrock, Royal Marine Light Infantry

Private Elmer Robert Darrock, Royal Marine Light Infantry

Elmer Robert Darrock was born on 19 December 1894 at Cardiff in Wales—evidence points to his name being mis-spelled and that the correct spelling is ‘Darroch’.[15] On leaving school, he followed his brother and joined the Great Western Railway on 1 March 1909 as a lamp boy. He enlisted at Bristol into the Royal Marine Light Infantry on 25 March 1912. After his initial training, which included a period on the battleship HMS Exmouth, he joined the compliment of HMS Thunderer, an Orion-class battleship, on 10 September 1913 and on which he served until November 1916, seeing action at the Battle of Jutland. After a period of time ashore, he joined HMS Highflyer on 13 April 1917. Highflyer was then refitting in Gibraltar. She went to sea on 11 May and sailed to Plymouth before visiting Sierra Leone on 4 June, and then sailing for Bermuda, where she arrived on 23 June to join the North American and West Indies Squadron. There is no record of when Darrock joined HMS Warrior but given that Highflyer sailed immediately for Halifax, and that Warrior was about to sail for the Caribbean, it is possible that it was just after he arrived in Bermuda.[16]

Private Darrock was sent to hospital (with Deck Hand J Prowse, see below, and Leading Deck Hand D Murdock) on 10 October suffering from influenza—he died of pneumonia at 8.30am on 19 October 1918, aged 23. He was buried on the afternoon of 22 October. His grave is number 19325 in Section 17. Elmer Robert Darrock is also commemorated on the Grangetown War Memorial, Cardiff and in the Welsh National Book of Remembrance at the Welsh National Temple of Peace and Health in Cardiff.

Grangetown War Memorial

Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class Harold Gurney Davis, Royal Naval Reserve

Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class Harold Gurney Davis, Royal Naval Reserve

Harold Gurney Davis was born in 1886 at Seaview on the Isle of Wight, where he was christened on 23 January 1887. His father was a master mariner, and Harold and his brother Lionel both became maritime engineers. He married Olive Hill in the latter part of 1915 and they lived at Eddington, in St Helens.

Harold Davis was rated as an Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class—the equivalent of a Chief Petty Officer—but is referred to in HMS Warrior’s log as ‘Engineer Warrant Officer’. There were at least three such engineers on board in this period. All went to hospital while Warrior was in Washington. The first, R Russell was sent to hospital in Colorado in June 1918 to be treated for tuberculosis; he was discharged in November. J A Thompson was sent to hospital on 29 September suffering from influenza; he survived and was discharged a week later. Harold Davis was not so lucky. He had been sent to hospital on 13 September 1918 and died of thrombosis of the mesentery vein at 1.30pm on 16 September 1918, aged 32.[17] He was buried on the afternoon of 19 September. His grave is number 84-NS in Section 15A. Harold Gurney Davis is also commemorated on the Isle of Wight County War Memorial in the Church of St Nicholas in Castro, Carisbrooke—the chapel, founded in the 11thC, was reconstructed in 1904, reworked as the county war memorial by local architect Percy Stone and dedicated in 1929. He is also commemorated on the Seaview Parish War Memorial, which is built into an exterior wall of St Peter’s Church, Seaview; on the wooden triptych in the south aisle of St Peter’s Church; and by an inscription on his parents’ gravestone in St Helens Cemetery.

Seaview War Memorial

Deck Hand William Kelly, Mercantile Marine Reserve

Deck Hand William Kelly, Mercantile Marine Reserve

William Kelly was born to Richard and Mary Kelly—from County Cork—in 1897 in Poplar in the East End of London, where his father worked on the docks. He was the youngest of six children. A merchant seaman, he served with the Mercantile Marine Reserve as a crew-member on HMS Warrior; there is no record of any other service.

Deck Hand Kelly was sent to hospital on 30 September 1918, with Sub Lieutenant E G Old, Warrant Engineer J A Thompson and Steward R J Goulden, all of whom were suffering from influenza. He died at 7.30am on 13 October, aged 21, and was buried on the afternoon of 16 October. His grave is number 19399 in Section 17.

Deck Hand Joseph Prowse, Mercantile Marine Reserve

Deck Hand Joseph Prowse, Mercantile Marine Reserve

Joseph Prowse was born on 21 May 1893. He was a merchant seaman rated ‘able’ when he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on 28 October 1915 (MB/572, Motorboatman). He served first on the Motorboat Resourceful at Southampton until 10 January 1916, when he joined HMS Hermione, the depot ship for the motor boat patrol.[18] On 13 September he joined HMS Europa, the flagship at Mudros, Greece for service with the Motorboat Penelope. From November 1916 he was administered by HMS Victory II (one of a number of similarly named, shore-based, administrative locations) until 22 March 1917. In this period his movements are not known but may have involved his transit to Bermuda. His record is annotated that he then transferred to the Royal Naval Reserve and had signed to acknowledge his wartime Naval engagement and being subject to Admiralty regulations and the Naval Discipline Act.[19] Sometime after March 1917 he found himself in the North American and West Indies Squadron and a crew-member on HMS Warrior.

Deck Hand Prowse was sent to hospital (with Private E R Darrock, see above, and Leading Deck Hand D Murdock) on 10 October suffering from influenza—he died on 6 January 1919, aged 25. He was buried on 8 January.[20] His grave is number 19515 in Section 17.

PO/B/992 Private James Schofield, Royal Marine Light Infantry

Private James Schofield, Royal Marine Light Infantry

James Schofield was born on 10 October 1882 at Bradford in Manchester, the third of seven sons and a daughter of Richard and Mary Ann Schofield. Like their father, the seven boys all became miners in the Manchester coalfield. James sought an alternative employment, however, and enlisted in Manchester on 11 June 1901 into the Royal Marine Light Infantry (PO/11551, Private). His first period of sea service began on 28 May 1902 when he joined HMS Duke of Wellington, the sail and steam powered, first-rate, which had been launched in 1852. She was decommissioned in 1903 and, after a short period ashore, Private Schofield joined HMS Imperieuse, an elderly cruiser, for a few weeks until 1 October 1903 when he joined HMS Hawke, a re-commissioned cruiser used to ferry crews to the Cape. From May 1904 he served ashore until he joined HMS Good Hope on 8 February 1906. Private Schofield remained with Good Hope, the flagship of the 1st Cruiser Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet, until 22 July 1907, when he briefly joined HMS Prince George in the Home Fleet. His final periods of sea service before joining the Royal Fleet Reserve, were with the cruiser HMS Argonaut from September 1907 to August 1908, when he joined HMS Venus, upon its return from the Quebec tercentenary celebrations. Private Schofield was transferred to the Royal Fleet Reserve on 27 June 1909.

He attended his drill periods annually until 1913 when he volunteered for transfer to the Immediate Class, the Fleet’s high readiness reserve (renumbered PO/B/992). Following the outbreak of war he was mobilised on 10 August 1914 and joined HMS Leviathan. He spent almost all of the war on Leviathan, an armoured cruiser, which, following a period spent hunting German raiders and escorting convoys, became the flagship of the Commander-in-Chief on the North American and West Indies Station, arriving in Bermuda on 26 March 1915. Private Schofield transferred to HMS Highflyer in Halifax in July 1918 before joining HMS Warrior on 17 August in Washington.

Private Schofield was sent to hospital on 20 December 1918 (with the Officer’s Chief Cook W J Labett), where he died of pneumonia on 23 December, aged 36. In a double burial ceremony, he was interred on the afternoon of 24 December beside Writer Symons. His grave is number 19518 in Section 17. He is also commemorated on Denton War Memorial.

Denton War Memorial

M/18229 Writer 3rd Class Thomas Henry Symons, Royal Navy

Writer 3rd Class Thomas Henry Symons, Royal Navy

Thomas Henry Symons was born on 8 May 1893 at Liskeard in Cornwall, the third of six children. He worked as a solicitor’s clerk before he enlisted into the Royal Navy on 10 January 1916. He joined HMS Highflyer on 16 June 1916, where he served until he joined HMS Warrior on 30 August 1918.

Writer Symons was sent to hospital on 17 December and died of pneumonia on 21 December 1918, aged 25. In a double burial ceremony, he was interred on the afternoon of 24 December beside Private Scofield. His grave is number 19519 in Section 17. He is also commemorated on Liskeard War Memorial.

Deck Hand Herbert Thomas, Mercantile Marine Reserve

Deck Hand Herbert Thomas, Mercantile Marine Reserve

Herbert Thomas was born in 1887 at Liverpool. He became a merchant seaman; it is not known when he joined HMS Warrior.

Deck Hand Thomas was sent to hospital on 8 October 1918 (with Cook A J Edney and Assistant Cook F J Trim) and died of pneumonia on 22 October 1918, aged 31. He was buried on the afternoon of 24 October. His grave is number 19400 in Section 17.

The Graves of Private J Schofield, Writer T H Symons and Deck Hands H Thomas and W Kelly

Acknowledgements:

Dix Noonan Webb for the photograph of the Mercantile Marine Medal.

David Dixon for the photograph of Denton War Memorial (under a creative commons licence).

Amanda Fulcher, archivist for the National Society of Daughters of the American Revolution, for providing the photographs of the 1918 Memorial Day ceremony.

International Wargraves Photography Project for the photographs of the original grave markers in Arlington National Cemetery.

John Greyson for the photograph of Grangetown War Memorial (under a creative commons licence).

Kevin Quick for the photograph of Seaview War Memorial.

Sources:

Naval-History.Net. This is an outstanding resource for those studying the Royal Navy in the 20thC. In particular, the site provided me with the transcriptions of the logs of the ships mentioned.

Newspapers.com.

1. (Back) HMS Warrior is referred to in some sources as ‘HM Yacht’ or ‘HMY’ Warrior. The ship’s log uses the term ‘HMS’, as do the graves of the men who died, and that is the term that I have used throughout.

2. (Back) ‘Society’. (13 Oct 1918). The Washington Post. p 29.

3. (Back) ‘Spokes from the Rudder Wheel.’ (May 1916). The Rudder. Volume 32, number 5, p 244. New York: Rudder Publishing.

4. (Back) Known as ‘pennant number’ since 1948. See Naval-History.net.

5. (Back) Form T124. This form was also used for men serving with the Royal Naval Reserve Trawler Section and for mercantile marine officers commissioned into the Royal Naval Reserve.

6. (Back) Now Fort Lesley J. McNair.

7. (Back) Memorial Day, the commemoration of those who died serving in the armed forces, was traditionally held on 30 May until 1968, when it was moved to the last Monday in May.

8. (Back) ‘Memorial Services, Lusitania Victims.’ (August 1918). Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine. Volume 52, number 8, pp 486-487.

9. (Back) Influenza Encyclopedia produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library.

10. (Back) Twenty-five men are specifically annotated as suffering from influenza and three from pheumonia.

11. (Back) The exact size of the ship’s compliment is not known but the photograph of the crew taken on 30 May 1918 shows 59 officers, warrant officers, ratings and marines, not including the Admiral and his three staff officers.

12. (Back) The hospital building, behind the Old Naval Observatory, on what was known as Observatory Hill or, more recently, Potomac Annex is part of a historic site that is being redeveloped and renovated for the US Department of State.

13. (Back) It should be noted that the numbering of the sections of Arlington National Cemetery differs from the locations as described by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

14. (Back) HMS Warrior was released from service in January 1919. She was bought in 1920 and renamed Goizeko Izarra (Basque – Morning Star)—in which guise she was used to evacuate children from Bilbao during the Spanish Civil War—and again in 1937, when she reverted to the name Warrior. Requisitioned again during the Second World War, she was named HMS Warrior II. On 11 July 1940 she was bombed and sunk in the English Channel. Chief Steward John William Collins, Naval Auxiliary Personnel (Merchant Navy), aged 60, was killed in the attack. He is buried in Portland Royal Naval Cemetery. Collins had served in The Border Regiment for four years before enlisting into the Royal Navy in 1909. He served throughout the First World War (Mentioned in Despatches) and was discharged in 1928.

15. (Back) See: (a) General Register Office. (First quarter 1895). England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. Volume 11a, p 345. (b) The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO). Census Returns of England and Wales, 1891. (c) TNA. PRO. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901. (d) TNA. PRO. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911. (e) TNA. PRO. Great Western Railway Company: Staff Records. RAIL264, piece 432. (f) Other references include his brother’s marriage and death registration etc.

16. (Back) He could also have joined HMS Warrior later—a number of crew-members joined HMS Warrior from, and were discharged to, HMS Highflyer, while Warrior was alongside in Washington.

17. (Back) Reported as ‘…the effects of Spanish influenza.’ See: ‘The Island and the War. Seaview.’ (28 September 1918). Isle of Wight County Press. p 8.

18. (Back) For an account of service with motor boats see: Maxwell, G S. (1920). London: The Motor Launch Patrol. J M Dent and Sons [online at Internet Archive].

19. (Back) The only men of the Royal Naval Reserve engaged in this manner (i.e. with Form T 124) were trawlermen who crewed craft engaged in minesweeping and similar duties. The record indicating this transfer to the Royal Naval Reserve and Prowse being recorded as Mercantile Marine Reserve at the time of his death cannot be reconciled. He is recorded on the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and Mercantile Marine Reserve medal rolls, the former referencing the latter.

20. (Back) District of Columbia, Deaths and Burials, 1840-1964. This record records his name as ‘Prouse’.

December 11, 2014

My Family in the First World War – Part 4: Robert Thompson

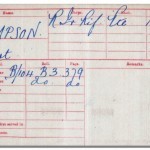

18/1141 Lance Corporal Robert Thompson

Robbie Thompson

My great-uncle Robbie was the eldest of the twelve children of Henry and Margaret Thompson, and the only one old enough to serve during the First World War.[1] He was born at Hyde Park, Mallusk in County Antrim on 25 December 1898 and enlisted, considerably underage, on 1 December 1915, a little less than a month short of his 17th birthday.

Robbie enlisted into The Royal Irish Rifles, the county regiment, intending to join the locally-raised 12th (Service) Battalion (Central Antrim), which was one of nine battalions of the Regiment in 36th (Ulster) Division.[2] By the time that he enlisted, the Ulster Division had completed its training and was in France, getting to grips with life in the trenches, and Robbie joined the 18th (Reserve) Battalion at Clandeboye near Newtownards, where he was allocated the regimental number 18/1141. The 18th (Reserve) Battalion had been formed in April 1915 from the depot companies of the 11th and 12th (Service) Battalions and had taken over the camp at Clandeboye, vacated when 108th Brigade moved to Seaford in Sussex, in July. It was here at Clandeboye that he completed his training.

It is not known when he arrived in France. Given the length of his training, the earliest that he would have travelled via England to a Base Depot in France was the summer of 1916—one of the reinforcements sent out to replace those lost when 36th (Ulster) Division had attacked at Thiepval and north of the River Ancre on 1 July. He was underage, however, and, if this was known, it is possible that he was held back until sometime in 1917, until after his 18th birthday.[3]

Rifleman Robert Thompson

Rifleman Thompson joined C Company, 15th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (North Belfast) in 107th Brigade. Not knowing when he arrived in France, it is impossible to describe his experiences before March 1918. If he joined the Battalion in early 1917 he was fortunate indeed to survive the three major attacks by 36th (Ulster) Division that year: On 7 June at Messines the Battalion attacked in the second wave against the ‘Black Line’ and suffered 12 men killed and 93 wounded; on 16 August, during the Battle of Langemarck, 15th Royal Irish Rifles was in reserve and there were few casualties, although there had been heavy casualties in B Company caused by shellfire in the preparatory phases; during the Battle of Cambrai the Battalion was uncommitted until 22 November when it attacked the Hindenburg Support Line. This action continued until the evening of 24 November, often at close quarters against a determined enemy. The casualties were severe but are not enumerated in the Battalion’s war diary; 64 officers and men are known to have been killed in action.[4]

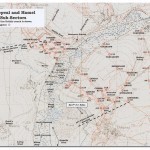

36th (Ulster) Division Sectors, March 1918

In 1918 Robbie Thompson found himself in a sector south-west of St Quentin near Grugies when 36th (Ulster) Division replaced French units there. By then he had been appointed a Lance Corporal in C Company. On 22 February there was a further reorganisation in the system of defence—from Blacker’s Boys:

‘…the manner in which defence was to be conducted was changed radically. Based on the German concept of ‘defence in depth’, the front was organised into three zones. The Forward Zone was essentially an outpost line in front of a line of supporting redoubts that would be held in enough strength to delay the enemy but from which its defenders would move back to the main line of defence — the Battle Zone — when attacked in strength. The Battle Zone, about two to three thousand yards back, comprised a series of well-built defence systems and redoubts that dominated the ground over which the enemy would attack. Reserves would also be available here to conduct local counter-attacks or to reinforce areas of particular threat. The third zone, the Corps Line, was to be set up in rear of the Battle Zone, but this was never achieved. The plan was a good one but, as would be proved, the troops were too thinly spread and insufficiently trained in it to make it effective.

In 36th (Ulster) Division’s area the ground was crossed by a series of ridges and valleys parallel to the front line. In the north, the outpost line lay on the same feature occupied by the enemy, and behind it lay the Grugies valley. This gave good cover from view and direct fire but provided a natural corridor along which the enemy could outflank the forward battalions. In addition, the front line of 14th (Light) Division on the right ran almost north-south, and the right flank was therefore weak and unlikely to hold if the villages of Urvillers and Essigny were captured. To the rear, the redoubts of the Forward Zone were on the next ridge, and farther back the redoubts of the Battle Zone lay on the low ridge along which ran the Essigny/Contescourt Road. The Ulster Division’s frontage was divided into three sectors, each allocated to a brigade. 108th Brigade was on the right, 107th Brigade held the centre and 109th Brigade was on the left.’

The men of 15th Royal Irish Rifles relieved 2nd Royal Irish Rifles in the Forward Zone on the night of 14/15 March. On 21 March the storm broke.

The exact dispositions of 15th Royal Irish Rifles and the detail of the action that took place on 21 March are difficult to determine—there is no official record of that period in the Battalion’s war diary.[5] The general dispositions may be deduced from the war diaries of Headquarters 107th Brigade, it’s two other battalions, the Division’s medium trench mortar batteries and 36th Battalion Machine Gun Corps (unfortunately it has not been possible to identify which company occupied each of the positions described below).

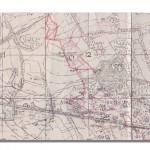

In the Forward Zone of 107th Brigade’s sector the ‘outpost line’ and the ‘line of resistance’ (see map) ran west-east, for 2,100 yards roughly along Auvergne Trench.[6] These lines, along the forward slope of a shallow ridge, were manned by two companies, with the four platoons of each company in strongpoints.[7] The role of the outpost line was to:

‘…keep the enemy’s front line, No-Man’s-Land and our own wire under constant observation by day and night from their own post to the next behind their own wire. All outposts will be wired round and alternative positions for each outpost prepared and used at different times to prevent the possibility of surprise by the enemy. The purpose of the outposts is to give warning of any enemy attack and to disorganise it in such a way as to give time to man the line of resistance. They are responsible that the post is held against small raiding parties. In the case of attack by a large force breaking through our line, they will fall back on their platoon in the line of resistance.’[8]

Positions Occupied by 15th Royal Irish Rifles on 21 March 1918

The Brigade Commander had identified four ‘points of tactical importance’. Two were in the line of resistance. The first of these was the higher ground south of Le Pire Aller on the left of the position.[9] The second was the plateau of slightly higher ground over the brigade boundary in 108th Brigade’s sector, which dominated his right flank. The platoons in the strongpoints along the line of resistance were ordered to hold ‘at all costs.’[10]

A third company was located on the reverse slop of the ridge, behind the line of resistance. It provided the ‘counter-attack company’, again with each of its platoons in strongpoints. The task of the counter-attack company ‘…in case of an enemy raid having effected a lodgement in our lines, is the immediate counter-attack by the two platoons nearest the lodgement.[11]

Behind the line of resistance was a shallow valley beyond which the ground rose again to the next line of defence. Here, one mile to the south-west of the line of resistance and 1,000 yards south of Grugies, was Racecourse Redoubt. The redoubt was centred on a fortified railway cutting—the third of the Brigade Commander’s points of tactical importance—and here were battalion headquarters, in a dugout in the cutting, and one company in the interlocking trenches of the fortified position around it.[12] The orders for those manning the redoubt were clear—they were to ‘…hold out to the last in case of a general attack in order to give time for the Battle Zone to be manned. It will on no account retire until orders are received from higher authority.’[13]

The defence of the Forward Zone was reinforced by 10 machine guns from B Company, 36th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps; two Stokes 3-inch mortars from 107th Trench Mortar Battery in the line of resistance; and two Newton 6-inch medium mortars from Y.36 Medium Trench Mortar Battery in Racecourse Redoubt.

From Blacker’s Boys:

Although there were some anticipatory British artillery barrages in the early hours, the night of 20/21 March was generally quiet. At 4.35am, however, the German offensive began with an intensive artillery barrage across the entire front. Employing guns and mortars firing high explosive, shrapnel and gas, it struck anything of importance, particularly communications, to a depth of two to four miles over a period of five hours. Between 6.00am and 9.40am the German infantry began its infiltration and advance.’

Lieutenant Colonel Claud George Cole-Hamilton CMG, DSO, KPM

The leading troops of the German 18th Army attacked 36th (Ulster) Division just after dawn. The enemy troops advanced in strength from the right flank along the valley behind the line of resistance—Lieutenant Colonel Cole-Hamilton,[14] the Commanding Officer of 15th Royal Irish Rifles wrote later; ‘…the front line was not attacked from the front at all, but from the rear.’[15] [16]

At 5.00am, after the order to ‘Man Battle Stations’ had been given, the Brigade Intelligence Officer, Lieutenant Cuming,[17] and the scouts had gone forward to Racecourse Redoubt. It was almost impossible for the companies and Battalion headquarters in the Forward Zone to convey what was happening because the heavy and well-planned artillery barrage had destroyed communications cable and telephone exchanges. Darkness at the early stages of the attack and the thick mist prevented visual signalling and the thick, foggy mist and the heavy shellfire compounded the problem for runners. Most importantly, communications between the forward battalions and their supporting artillery batteries were quickly lost.

At 8.00am Lieutenant Colonel Cole-Hamilton sent a message by a runner, who got it to brigade headquarters:

‘All communications forward and rear gone. Latest information from the line 6.45 a.m., received 7.45a.m. from Counter-attack Company says “Hostile artillery fire intense in this Sector. Casualties nil.” Very heavy shelling round redoubt. As far as known casualties 4 killed and one wounded. Fog still very thick.’[18]