Nick Metcalfe's Blog

May 22, 2025

Commemorating Royal Signals War Dead – New Page, ‘D’

The Royal Signals casualties whose surnames begin with ‘D’ have now been included on the War Dead page on this website (completed letters are hyperlinked; the documents open as pdfs). They amount to 255 all ranks who died on operations in the inter-war years, in the Second World War and in the campaigns of the post-Second World War period. Included on this list are three members of the Auxiliary Territorial Service who served with Royal Signals, and a Lady Teleprinter Operator of Malaya Command Signals who died in a Japanese internment camp.

The graves of Corporal E. C. Turner and Signalman N. Davies at Manzai Fort cemetery showing their original construction.

The very weathered concrete grave marker for Signalman Norman Davies as it is now at Manzai Fort Cemetery.

The casualties include:

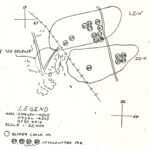

Seventy-five men were killed in action or died of wounds or were killed as a result of terrorist action, including:On the early morning of 9 April 1937, a convoy set out from Manzai Fort destined for the garrison at Wana carrying supplies and some officers and men returning to their units. At about 7.40a.m. it was ambushed at the western end of the Shahur Tangi, a narrow, steep-sided, three-mile long gorge, eight miles west of Jandola. Raiders hidden in the rocks close to the road attacked the convoy along its length causing very heavy casualties but the armoured cars, the infantry escort from 4/16th Punjab Regiment and the other troops with the convoy fought most gallantly and prevented the convoy from being overrun. In the convoy was a detachment from Waziristan District Signals commanded by Corporal E. C. Turner. Corporal Turner and Signalman N. Davies were killed in action, the Indian driver (Signalman Joseph) and Signalman T. Bowkett were wounded,[1] the latter severely, but three other men, Signalmen Bartlett and McKenna and an Indian soldier, escaped unscathed. In total, the attack claimed six British officers and two other ranks (Turner and Davies) killed, five British officers and one other rank (Bowkett) wounded, one Indian medical officer and 20 Indian other ranks killed, and 39 Indian all ranks wounded. You can read about the ambush in the Shahur Tangi here and about Manzai Fort Cemetery here (as casualties outwith the World Wars, their remains were not reinterred in a C.W.G.C. cemetery and Manzai Fort Cemetery is not maintained by the C.W.G.C.).

Signalman J. G. Dart, 2nd Air Formation Signals, was killed on 20 November 1942 during an air raid at Maison Blanche Airfield, Algiers just after the landings in North Africa during Operation Torch. The raid on the harbour and the airfield resulted in the death of 35 all ranks of the Army, Royal Air Force and Merchant Navy. Others from 2nd Air Formation Signals killed at Maison Blanche were Company Quartermaster Serjeant R. Turner and Lance Serjeant J. R. Humpries. Lance Corporal N. F. Alderman, 45th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery Signal Section and Signalman L. J. Wallington, 1st Parachute Brigade Signal Section were also killed in the attack.

Driver J. H. Davies, 4th Army Group Royal Artillery Signal Section, was killed in action on 14 July 1944 when a line maintenance party was attacked by enemy aircraft. Lance Corporal G. G. Hoy, Signalman A. W. Clayton, Signalman S. Radley, and Signalman H. Salad were wounded; for his bravery in Normandy and the aftermath Lance Corporal Hoy was awarded a Military Medal.[2]

During the Aden Emergency in the Federation of South Arabia in operations against dissident tribesmen astride the Lahej-Dhala road in the Thumier area, following a report that four hand grenades had been found hidden under rocks which were placed to block the road, Corporal M. R. Davies, Federal Regular Army Signal Squadron attached to 4th Battalion, Federal Regular Army, volunteered to go out with a Land Rover to assist in road clearing operations. He was killed in action on 3 April 1964 when his vehicle hit a land mine.

In addition, 4 men were killed in action at sea—one during the evacuation from Dunkirk in May 1940, two when R.M.S. Lancastria was sunk in the evacuation from western France on 17 June 1940 and one in the evacuation after the Battle of Greece in April 1941.Forty-four men died as prisoners of war in the Second World War—39 as prisoners of the Japanese and five as prisoners of the western Axis powers. Of the prisoners of the Japanese, the majority died while working as labour on the Thai-Burma Railway but seven prisoners of war were killed in action at sea when ships they were aboard were sunk by Allied submarines and aircraft (over 10,000 Allied prisoners of war were lost at sea in the Far East). One man was killed in action in Europe when the area in which he was working was bombed. In addition, two men were murdered as prisoners of war.Signalman J. K. Davies, 30th Corps Signals, was captured on 25 November 1941 in Operation Crusader during the Western Desert Campaign. Held in Italy until the Italian Armistice, he was transferred to Stalag IV-C near Bystřice in the Sudetenland (now Dubí, Czech Republic). He was killed in action on 12 May 1944 in bombing raid by aircraft of the United States Army Air Forces on the Sudetenländische Treibstoffwerke (Sudetenland Fuel Works) at Brüx (Most, Czech Republic). No fewer than 34 prisoners of war were killed in the raid. This was the first attack by the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe in the ‘Oil Campaign’.

Signalman A. Dawes, formerly No. 28 Wing Signal Section, 2nd Air Formation Signals, was captured on Java in March 1942 during the Japanese invasion of the Netherlands East Indies. He was part of a large party transported from Batavia (Jakarta) on 22 October 1942 on board S.S. Yoshida Maru to Singapore and then from Singapore on 29 October 1942 on board S.S. Singapore Maru to Moji (Moji-ku, Kitakyūshū), Japan, arriving on 25 November. He died of dysentery on board on 19 November 1942. Over 100 all ranks, including six Royal Signals soldiers, died en route or soon after arriving in Japan due to the awful conditions on the ship. With 334 others who died at Moji, his remains were cremated and interred in a communal urn and at the end of the war transported to Tokyo, and then interred in the British mausoleum at Yokohama. They were finally reinterred on 22 October 1946 at the Yokohama Cremation Memorial, Yokohama War Cemetery, Japan.

Lance Corporal G. W. Dent, formerly No. 83 Medium Wireless Section, 10th Corps Signals, was captured in June 1942 in the Battle of Mersa Matruh during the Western Desert Campaign. Transported to Italy, he was held at Prigione di Guerra 78 (Campo 78) near Sulmona until the Italian Armistice when he escaped with Sapper A. Parker.[3] Having evaded capture for over 150 miles while heading south towards Allied lines, on 12 September 1943 near Cerignola the two men, in an attempt to evade imminent capture, joined a group of 11 Italians, but were immediately captured by German troops. Soon after their capture, Lance Corporal Dent and an Italian were taken away and shot; Parker survived by declaring himself a British escapee, after which the other Italians were murdered. Parker later escaped again and reached Allied lines. Lance Corporal Dent has no known grave and is commemorated on the Alamein Memorial, Egypt.

Captain P. L. Dudgeon M.C was an early volunteer for Special Forces and took part in raiding operations with No. 62 Commando (Small Scale Raiding Force), for which he was awarded the Military Cross.[4] These included Operation Basalt, the raid on Sark in the Channel Islands that resulted in the German Kommandobefehl (Commando Order) that called for the immediate execution of captured Allied ‘commandos’. Having joined 2nd Special Air Service Regiment, Captain Dudgeon was dropped into the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy on the night of 7/8 September 1943 on Operation Speedwell but he and his partner, Gunner B. O. Brunt,[5] were captured at Passo della Cisa on 2 October 1943. After being interrogated, they were shot the following afternoon, 3 October 1943, close to where they had been captured.[6] Originally buried where they were killed, the remains of both men were reinterred in August 1945 at Florence War Cemetery, Italy.

Five men died in air crashes, including:Signalman C. Dawson, 6th Airborne Divisional Signals, was killed during a training flight on the morning of 7 December 1943 when General Aircraft Hotspur glider, serial BT822, of 2nd Battalion, Glider Pilot Regiment and flying from R.A.F. Netheravon, crashed into a field near Collingbourne Ducis, Wiltshire just after being released from the tug aircraft. Also killed were Lance Serjeant M. King and Signalmen C. Campbell, S. Jackson, A. Pallett, and H. Simpson and the Glider Pilot Regiment crew, Staff Serjeant E. A. Jeffs and Serjeant P. D. Taylor.

Lieutenant Colonel R. P. G. Denman, who had twice been mentioned in despatches during the First World War, was a specialist in radio countermeasures at the War Office and was attached to No. 109 Squadron, Royal Air Force. While aircraft of the squadron were conducting a V.H.F. radio jamming mission supporting Operation Crusader during the Western Desert Campaign, he and the crew of Vickers Wellington, serial Z8907, were killed on 21 November 1941 when the aircraft was shot down. Originally buried in a common grave near the site of the crash, their remains were reinterred in a collective grave on 26 January 1944 at Halfaya Sollum War Cemetery, Egypt. His widow, Mrs. C. M. Denman, joined the Signals Directorate of Special Operations Executive from the War Office in December 1942. For the remainder of the war she ran the clerical aspects of the directorate and was appointed an M.B.E. (Civil Division) in 1946.[7]

Fifty-four men died of disease or natural causes, many from diseases that today are readily treatable,Thirty-three died in road traffic accidents, two died in ‘battle accidents’ and 11 men died in various other accidents,Four men took their own lives,One man died as a result of ‘misadventure’—Lance Corporal W. T. Davies from 2nd Parachute Brigade Signal Section who had been engaged in a series of armed robberies with Signalman J. Metheringham and both of whom, whilst resisting arrest, were shot and killed by two members of the Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali, which acted as a security and police force in support of the Allied forces after the Italian Armistice. Regardless of the manner of their deaths, they are considered war casualties and both men are commemorated by the C.W.G.C. and in the Royal Signals Roll of Honour.Six men drowned while swimming when off duty,Four men died as a result of the negligent discharge of a weapon,Fourteen men died of unknown causes. These were mostly men who died after the war had ended but in the period of post-war commemoration, and most probably died of disease or natural causes.Also included are three members of the Auxiliary Territorial Service serving with Royal Signals—one died of disease/natural causes, one was killed n an accident and Section Leader V. M. Divey who was killed in action on 17 October 1940 in an air raid at Fort Bridgewoods when a bomb exploded beside the lorry in which she was a passenger. Also killed were Volunteers G. M. E. Alrich and I. M. Sparrow.Finally, also included is Lady Teleprinter Operator S. A. Daniel of Malaya Command Signals. Having escaped from Singapore in February 1942 during the Malayan Campaign/Battle of Singapore, she was captured in Sumatra and held at Palembang Women’s Camp, where she died on 25 August 1945, aged 44. Mrs. Daniel is the only such C.W.G.C. commemoration.1. (Back) 2324319 Signalman Thomas Bowkett; and 8880 Signalman Joseph. Signalman Bowkett recovered from his wounds in England before returning to India to join ‘A’ Corps Signals. During the Second World War he served as the section sergeant of ‘M’ Section, 6th Airborne Divisional Signals; he was wounded in action by mortar fire in the breakout from Normandy on 25 June 1944. On 25 March 1945 Sergeant Thomas Bowkett died of wounds received the previous day during Operation Varsity, the crossing of the River Rhine. Originally buried in a cemetery at Gildern-Kappellen, his remains were reinterred in Reichswald Forest War Cemetery on 19 November 1946.

2. (Back) Military Medal. 2360982 Lance Corporal George Gill Hoy, 4th Army Group Royal Artillery Signal Section, First Canadian Army. Lance Corporal Hoy has commanded a line detachment in this headquarters with outstanding success throughout operations on the continent, and it is greatly due to his untiring efforts that communications between my headquarters and regiments have been so good; he has never spared himself and has been an example to all around him. On one occasion on 14th July 1944, whilst on line maintenance his party was attacked by enemy aircraft: his driver was killed and he himself (and three other members of his detachment) was wounded. In spite of his wound Lance Corporal Hoy remained in charge and helped with the evacuation of the other wounded, until he himself became unconscious. LG 11 October 1945; 37302, p. 5002.

3. (Back) 1877817 Sapper Alfred Parker had been captured on Operation Colossus, the raid in February 1941 by ‘X’ Troop, 11th Special Air Service Battalion at Tragino in southern Italy. For his escape he was mentioned in despatches (LG 15 June 1944; 36563, p. 2855); the recommendation records the killing of Lance Corporal Dent.

4. (Back) Military Cross. 131676 Lieutenant Patrick Laurence Dudgeon, No. 62 Commando (Small Scale Raiding Force). Operation Dryad—Les Casquets, and Operation Basalt—Sark, Channel Islands, European Theatre, 1942. Lieutenant Dudgeon has shown himself to be a most trustworthy and reliable officer, and to be possessed of resourcefulness and determination in action. In addition to the power of leadership which he has displayed, he speaks fluent German, and proved himself invaluable on Operation Dryad when it was necessary to interrogate German prisoners. On this operation Lieutenant Dudgeon’s task consisted of entering one of the buildings alone and overcoming any resistance met with; he took two prisoners in this building and whilst holding them up extracted useful information from them regarding the disposition of arms, number of men on the post and other details. He has proved to be at all times cheerful and willing and to be a brave and courageous officer. Lieutenant Dudgeon also took part in Operation Basalt and as one of those trying the doors and windows of the houses entered did excellently. He was also invaluable as an interpreter. L.G. 15 December 1942; 35821, p. 5437.

Despatches (Posthumous). 131676 Captain Patrick Laurence Dudgeon. 2nd Special Air Service Regiment. Operation Speedwell— Emilia-Romagna. Italian Campaign. L.G. 30 August 1945; 37244. Rank corrected in L.G. 23 January 1947; 37861.

5. (Back) 1800118 Gunner Bernard Oliver Brunt, Royal Regiment of Artillery.

6. (Back) For a detailed account of their service and death see X. QGM, Ex-Lance Corporal. (2016). The SAS and LRDG Roll of Honour 1941-47. Privately Published. Vol. 2, pp. 145-151.

6. (Back) M.B.E. (Civil Division). Mrs. Charlotte Mathilde Denman. Clerical Assistant, Signals Directorate, Special Operations Executive, Home Forces. L.G. 1 January 1946; 37412, p. 291.

April 1, 2025

Commemorating Royal Signals War Dead – New Page, ‘M’

The Royal Signals casualties whose surnames begin with ‘M’ have now been included on the War Dead page on this website (the document opens as a pdf).

Of the first letter for surnames in England, ‘M’ accounts for about 7% but this rises to over 20% in Scotland. Notwithstanding the large number of Scottish soldiers who have served with Royal Signals, surnames beginning with ‘M’ tend to the former, making up a little over 8% of Royal Signals casualties (446 all ranks).

Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery in the north of Poland. Buried here is Signalman Cecil McCormack of 2nd Anti-Aircraft Brigade Signal Section who was captured in the latter stages of the Battle of France and held at Stalag XX-A in Thorn (Toruń) in Poland, where he died as a prisoner of war on 25 December 1940. (Photo: C.W.G.C.)

The casualties include:

One hundred and seventeen who were killed in action or died of wounds or were killed as a result of terrorist action, including:In the early stages of the Malayan Campaign, in the Battle of Jitra fought by 11th Indian Division, Captain J. L. Mainprize, Officer Commanding 28th Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section was killed in action on 12 December 1941 with Captain A. S. Hargreaves, 15th Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section, when they were caught by crossfire while travelling in a vehicle near Gurun. On 15 December Captain K. Mole was posted from 9th Indian Divisional Signals to 15th Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section with Second Lieutenant R. D. G. Meek to replace Captain Hargreaves and Second Lieutenant A. J. Aitken, the latter having been killed in action on 13 December. Both Captain Mole and Second Lieutenant Meek were killed in action on 11 February 1942 in an ambush in the Battle of Bukit Timah.

Following the ‘Quit India’ speech by Mahatma Gandhi in August 1942, a series of bomb attacks were carried out across India by activists allied to the Indian National Congress. On 26 January 1943 an explosion occurred at the ‘Capitol Talkies’ cinema at East Street, Poona in the Bombay Presidency (Pune, Maharashtra) that mortally wounded Lance Corporal R. G. Miller of 2nd Divisional Signals; he died of his injuries later that night at No. 3 (Indian) General Hospital, Poona. Two other soldiers died and 13 were wounded. A second bomb was found that evening at another cinema but it was rendered safe by the soldier who found it.

Lieutenant D. W. Mackay, 7th Indian Divisional Signals, who was killed in action on 6 February 1944 during the attack on the headquarters of 7th Indian Division during the Burma Campaign. After the attackers had established light machine-guns of the ridge north of Laung Chaung, the Indian other ranks of an engineer battalion holding a portion of this sector became restive. Lieutenant Mackay, in charge of the divisional signals’ defence in this area, reported to the commanding officer for instructions. Having been ordered to make the 40-strong detachment of the engineer battalion stay in their positions, he returned to that area but on the way was badly wounded in both legs. Also in this area was Lieutenant H. D. Crittall who was awarded a Military Cross for his part in the defence and for attempting to save the life of Lieutenant Mackay. Eight Royal Signals and 18 Indian Signal Corps all ranks were lost in the action.

On 13 August 1967 in a grenade attack on Singapore Lines, Aden during the Aden Emergency in the Federation of South Arabia Signalman M. S. Mileson of 2 Squadron, 15th Signal Regiment was killed and three men were wounded.

In addition, 14 men were killed in action at sea, including:Serjeant H. W. W. Middleton, serving with Special Communications Unit No. 1, part of Section VIII (Communications) of the Secret Intelligence Service, had served during the First World War as a Boy 1st Class at the Battle of Jutland on board the battleship H.M.S. Barham. Recruited for service with Special Communications Unit No. 1, he was killed in action at sea on 21 February 1941 when the ship in which he was travelling was torpedoed. The ship has not been identified.

Serjeant A. Murray of No. 21 Army Air Support Control Signal Section was killed in action at sea on 12 September 1942 en route from Suez to the United Kingdom via Cape Town when the troopship and prisoner of war transport R.M.S. Laconia was sunk by U-156 in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, 800 miles south of Monrovia, Liberia. Over 1,600 people were lost (most being Italian prisoners of war) and Lieutenant P. W. McCreeth of No. 3 General Headquarters Signals was the only other Royal Signals casualty in the incident.

Signalman J. Marshall, 2nd Anti-Aircraft Brigade Signal Section, who was killed in action on 26 July 1943 during Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, when M.V. Fishpool exploded in Syracuse harbour after being attacked the previous night. Also killed were Corporal G. Roberts and Signalmen J. C. Beck, J. R. Clark and V. P. Donnelly. For their bravery during the attack Corporal C. H. Yates was awarded the British Empire Medal and Captain W. J. T. Stewart was mentioned in despatches. Several other awards were made to Royal Navy personnel for gallantry in the aftermath of the attack.

Eighty-two men died as prisoners of war in the Second World War—70 as prisoners of the Japanese and 12 as prisoners of the western Axis powers. The majority died while working as labour on the Thai-Burma Railway but five prisoners were killed in action or died of wounds (three in air raids, one soon after being captured and one having escaped) and 14 prisoners of war were killed in action at sea (10 in the Far East and four in the Mediterranean) when ships they were aboard were sunk by Allied submarines and aircraft (over 10,000 Allied prisoners of war were lost at sea in the Far East). These include:Signalman R. D. Millar, 12th Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section, was captured during the Malayan Campaign/Battle of Singapore. He was transported from Singapore to Kuching, Sarawak on the S.S. Imabari Maru (S.S. DeKlerk) on 28 March 1943 (with the Australian ‘‘E’ Force’ that was destined for Sandakan) and held at Batu Lingtang, and then transported from Kuching to Labuan Island, Borneo in August 1944 (the ‘Labuan Party’) to construct an airfield, where he died as a prisoner of war on 5 January 1945. Of the 25 Royal Signals all ranks transported with ‘‘E’ Force’ (two officers, a warrant officer and 22 other ranks), 16 died, 10 of whom died on Labuan or later having been taken off the island. None of the 100 prisoners from Sandakan or 200 men from Kuching (the ‘Labuan Party’) that were transferred to Labuan Island survived—more than half died on the island and the remainder died (some being murdered) between March and June 1945 in Brunei and at locations in and around Miri, Sarawak.

Signalman R. Miles, formerly Malaya Command Signals, was captured during the Malayan Campaign/Battle of Singapore and transported to work on the Thai-Burma Railway on 9 October 1942 in the ‘River Valley Road Party’ (Train 1). He worked in ‘No. 1 Group’ and returned to Singapore in June 1944. Transported on 2 February 1945 on board S.S. Haruyasa Maru to Saigon in French Indochina (Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam), he was killed in action as a prisoner of war on 9 April 1945 when a train carrying P.W. from the camp at Long Thành (No. 10 Branch Camp) to another camp was attacked by a United States Army Air Forces Consolidated B-24 Liberator on the North-South Railway near Tan Son Hoa on the eastern outskirts of Saigon. Fifty prisoners of war were killed in the attack and five were seriously injured, losing limbs.

Seven men died in air crashes, including:Signalman A. D. McCormick, ‘G’ Company, Air Formation Signals, was wounded on 18 December 1944 during the Dekemvriana (the ‘December events’ preceding the Greek Civil War) in the attack by the Greek People’s Liberation Army (E.L.A.S.) at Kifisia, the site of Air Headquarters, Greece, in which Drivers H. Summers and J. M. Vitty were killed in action. He was killed on 21 December 1944 when South African Air Force C-47 Dakota, serial KG498, crashed near Bari, Italy while travelling from Athens, Greece to Brindisi, Italy with four aircrew and 19 mostly wounded all ranks. There was only one survivor. Signalman D. Laurie was also killed in the crash.

Corporal M. P. Murphy, 22nd Special Air Service Regiment Signal Troop who was killed on 4 May 1963 when Royal Air Force Bristol Belvedere, serial XG473, of No. 66 Squadron, Royal Air Force crashed in the Trusan River Valley near Long Merarap, Sarawak during the Borneo Campaign. All nine crew and passengers were killed.[1]

Ninety-nine men died of disease or natural causes, many from diseases that today are readily treatable,Sixty men died in road traffic accidents, three died in ‘battle accidents’ (one of which was also a traffic accident) and 16 men died in various other accidents,Fifteen men took their own lives,Two men died as a result of ‘misadventure’—one who inadvertently drank poison, and Signalman J. Metheringham from 2nd Parachute Brigade Signal Section who had been engaged in a series of armed robberies with Lance Corporal W. T. Davies and both of whom, whilst resisting arrest, were shot and killed by two members of the Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali, which acted as a security and police force in support of the Allied forces after the Italian Armistice. Regardless of the manner of their death, they are considered war casualties and both men are commemorated by the C.W.G.C. and in the Royal Signals Roll of Honour.Two men were murdered:After the war but in the period of commemoration, on 9 October 1947 Mat Taram bin Sa’al was travelling with his family on the train from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur. He ran amok with a knife in the restaurant car and attacked four Royal Signals soldiers and two civilians and, after jumping from the train near Bangi south of Kuala Lumpur, attacked more people in a rubber plantation and alongside the railway. Serjeant H. V. K. Marston was killed during the initial attack; Driver J. Cormack was severely wounded and died of his injuries on 10 October 1947; Driver Robert Ralston was severely injured and another soldier was slightly wounded. Nine civilians were killed in the rampage or died of their injuries and ten other civilians were wounded. The killer was later arrested, and in April 1948 was tried and sentenced to be confined at a mental hospital. The Royal Signals soldiers were travelling to the United Kingdom to be discharged at the end of their service.

Following serious riots and looting in Ismailia in the Canal Zone in the autumn of 1951, the police in the city were reinforced by a large contingent of armed auxiliary police from Cairo, many of whom were based at a police sub-barracks, a former hospital known as the Bureau Sanitaire. In mid-November, however, the police perpetrated a series of fights, some through indiscipline others deliberate, that resulted in a serious escalation of violence against British troops and their families in the town. On 17 November the trouble came to a head when a patrol roused a policeman from sleep who then fired on the patrol and ran into the Bureau Sanitaire crying that an attempt had been made to kidnap him. The police in the barracks rushed into the street and there, and from the barracks itself, proceeded to fire at anything that moved. After several hours, the police were persuaded to stop firing and it was then that the body of the first British casualty was discovered near the Bureau Sanitaire; Major J. C. S. McDouall of General Headquarters, Middle East Land Forces had been beaten and then shot at close range. Five more British military personnel were killed over the next 24 hours. A Royal Signals N.C.O., Sergeant J. G. Christie, was awarded a British Empire Medal for his bravery during the troubles.

Five men drowned while swimming when off duty,Five men died as a result of the negligent discharge of a weapon,Nineteen men died of unknown causes. These were mostly men who died after the war had ended but in the period of post-war commemoration, and most probably died of disease or natural causes.1. (Back) Those killed were:

Crew: 607191 Flight Lieutenant Arthur Paul John Dobson; 166081 Flight Lieutenant Derek Reginald Watson Viner; and 3524433 Corporal John Llewelyn Williams from No. 66 Squadron, Royal Air Force.

Military Passengers: 297716 Major Ronald Henry Douglas Norman M.B.E., M.C., The Parachute Regiment and Second-in-Command, 22nd Special Air Service Regiment; 189285 Major Henry Arthur Irwin Thompson M.C., Royal Highland Fusiliers and Operations Officer, 22nd Special Air Service Regiment; and 410460 Captain John Frank Conington, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) and 22nd Special Air Service Regiment.

Civilian Passengers: Mr. Michael Henry Day, Foreign Office (Secret Intelligence Service); and Mr. Derrick Stanley Hatton Reddish M.M., The Borneo Company.

7891584 Corporal D. S. H. Reddish, 3rd County of London Yeomanry (Sharpshooters) was awarded the Military Medal for his gallant conduct during the Western Desert Campaign (LG 20 January 1942; 35422, p. 330. Recommendation: THA: WO 373/18/295.) Later Major D. H. S. Reddish M.M. He was awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct for his service during the Borneo Campaign; the award, authorised before he died, was dated 3 May 1963 (LG 28 May 1963; 43003, p. 4597).

February 18, 2025

The Mechanised Transport CorpsPart 1: The Early Years

As part of a project looking at honours and awards to some of the women’s services, I came across an article about the award of the Croix de Guerre to British women volunteers of the Mechanised Transport Corps who had served with the French Army during the Battle of France in 1940. Intrigued I did a bit of digging but with little result—most of the available sources online are scanty in their detail and many conflate the various components of the M.T.C. As is often the case, a search of the British Newspaper Archive provided many good leads and those led to a visit to the Library of Congress to read some long-out-of-print memoires. This is the first of four articles about this most interesting volunteer organisation. For details of the honours and awards to the M.T.C. see here.

Edith, Marchioness of Londonderry D.B.E.

Founder of the Women’s Legion.

The Mechanised Transport Corps had its origins in the motor transport section of the Women’s Legion that remained independent after the formation of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in 1917; it served with great distinction in the United Kingdom and then in France after the Armistice. The section continued on a much smaller scale after the war and in 1927 the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers was recognised by the Army Council as a voluntary reserve transport unit and took its place on the Army List, albeit unfunded by the War Office.[1] Throughout the inter-war years, the President of the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers was Lady Londonderry[2] (the founder of the Women’s Legion) and its secretary was Miss B. G. Ward O.B.E.,[3] both of whom had been recognised for their service during the First World War. In 1937 it was renamed Women’s Legion Mechanical Transport Section.

Women’s Legion Motor Drivers, 1918

Prior to the Second World War, in July 1937 Lady Londonderry proposed a ‘new’ Women’s Legion.[4] Beginning as an extension of the Women’s Legion Mechanical Transport Section, it began training in anti-gas drills, first aid, map reading and signalling at Regent’s Park Barracks in November that year. Aged between 18 and 40, its members were required to have a clean driving licence, paid a subscription upon enrolment and purchased their own uniforms. The unit established at Regents Park became No. 1 Company and was led by Mrs. G. M. Cook O.B.E., a driving force behind the transport section in the earlier war.[5] Early success led to a plan in January 1938 to expand the organisation to provide many more women capable of driving commercial transport in the event of a national emergency and recruitment soon began in earnest. Miss Ward commented, ‘There is no difficulty in finding women who can drive lorries… they are quite capable of driving large ambulances and lighter lorries. During the war they did it and they would be able to do it again.’[6]

Mrs. G. M. Cook O.B.E

Corps Commandant, Mechanised Transport Corps

On 6 May 1938, at a meeting chaired by Major General Sir John Brown,[7] Deputy Director General Territorial Army, and attended by representatives of the principal women’s voluntary emergency organisations,[8] the foundation was laid for the formation of what would become the Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women’s branch of the British Army. The formation of the A.T.S was announced in September 1938 and it quickly subsumed the various women’s organisations with the exception of the Women’s Legion Mechanical Transport Section which was able to maintain its independence as a volunteer organisation.

With its headquarters at 33 Leinster Gardens, Bayswater and under Mrs. Cook’s leadership it began further recruitment. It was renamed the Mechanised Transport Training Corps in early 1939 but at the end of that year ‘Training’ was dropped from its title. The M.T.C. expanded quickly and at its height comprised over 3,000 personnel organised into companies in 12 regions.[9] It proved very popular with women ineligible for service with the armed forces and married women with family commitments.

The women of the M.T.C were uniformed in the style of A.T.S. officers (which caused some controversy) with their uniforms piped in blue.[10] A distinctive badge was worn on the uniform cap and tunic lapels. The brass cap and lapel badges of the M.T.T.C. comprised crossed open-ended spanners on top of a vehicle tyre with the letters ‘M’ & ‘T’ on the top spanner ends and ‘T’ & ‘C’ on the bottom spanner ends. On the lower edge of the tyre was the motto ‘PRO PATRIA’ (‘For One’s Country’). After the change of name, the second ‘T’ was removed and the ‘C’ moved to the centre of the crossed spanners. Buttons were plain with an embossed fleur-de-lis under the letters ‘M T C’. In time, several different armbands, badges and lapel flashes were worn by components of the M.T.C. linking them to the organisation for which they worked or to indicate wartime service in France. Officers’ rank badges were a combination of five-pointed stars, roses and gold bars.[11] (See the gallery below.)

In the early part of the Second World War the M.T.C. provided drivers for Civil Defence organisations and the Home Guard. Notable amongst the former were the women of an M.T.C. company who volunteered to drive the Lambeth Borough Council Air Raid Precautions’ stretcher parties. Two drivers, Maisie Coppock and ‘Denny’ Goodbody,[12] were awarded the British Empire Medal for their bravery in the aftermath of an air raid. The incident occurred at 7.45p.m. on 15 October 1940 at Morley College, Westminster Bridge Road in Lambeth, which was being used as an emergency rest centre by Lambeth Borough Council and at the time of the attack held 193 people, many of whom had lost their homes. It was struck by a single bomb that demolished much of the structure and killed 57 people. Three men of an A.R.P. stretcher party and the two drivers dug a tunnel with their hands and freed about 14 people, passing them from one to another. Later, Goodbody was separated from the group and assisted a rescue party that had made a tunnel that was too small for any of the men to get through. She volunteered to try and was able to wriggle through to a trapped woman but heavy rubble resting prevented her rescue; the woman was extracted later after another opening was made. The three men of the stretcher party were also awarded the B.E.M.

Mr. Richard Rance B.E.M., Mr. Norman Jaeger B.E.M. (Leader), Mrs. Mary Denise Goodbody B.E.M. and Mr. Alexander Muirhead Kerr B.E.M.; Air Raid Precautions, Lambeth

No fewer than four women of the M.T.C. were killed during the Blitz, recorded as ‘Civilian War Dead’ by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission:[13]

Eileen Knocker,[14] a nurse and midwife who had served in France during the First World War with a Voluntary Aid Detachment, was killed at Trebovir Road, Earl’s Court during an air raid on 24 September 1940; 10 others were killed in the blast.

Mrs. Eve Ellerbeck,[15] an assistant company leader based at No. 2 Stretcher Party Station, South Lambeth Road School, was killed in an air raid on 5 November 1940 when the station was hit; eight A.R.P. stretcher bearers stationed there were also killed, as were several civilians taking shelter.

Mrs. ‘Molly’ Orton,[16] and Mrs. Patricia Parley[17] were killed in an air raid on 17 February 1941 when a bomb hit the house on South End Road, Hampstead in which they were staying with Parley’s mother, Adelaide, Lady Moore who was also killed, as was the housekeeper Mrs. Rebecca Henry.

Elsewhere during the Blitz, the organisation provided a considerable number of drivers for American Ambulance Great Britain, a fleet of vehicles paid for by donors in the United States that provided ambulances, mobile first aid posts and mobile surgical teams in areas suffering air raids. By the end of the war the responsibility for running the organisation’s 27 stations was split almost equally between the M.T.C. and A,A.G.B. The M.T.C. also drove for the Queen’s Messenger Convoys (the ‘Food Flying Squad’) made up of vehicles, mostly donated by the British War Relief Society of America, managed by the Ministry of Food and staffed by the Women’s Voluntary Service that provided canteen services in bombed towns and cities. By November 1941 22 convoys were in operation, each comprising three mobile canteens, two food lorries, two kitchen lorries, a water carrier and a staff liaison car.

W.V.S. and their M.T.C. drivers of the Queen’s Messengers Convoy.

Increasingly, drivers were provided for various government ministries, the Blood Transfusion Service,[18] and the exiled governments and forces of Allied nations, notably for elements of the United States forces that began to arrive in 1942. The highest profile of these was probably Mrs. K. H. M. ‘Kay’ Summersby who drove for General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, earning her the British Empire Medal.

While well-regarded in Great Britain in the early years of the war (although as will be seen in a later article, not without some criticism), it would be the accolades earned during the Battle of France that would cement the reputation of the M.T.C.

Part 2—The Battle of France. (To follow.)

1. (Back) Army Order 180 of 1927 recognised the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers on the same terms as those approved by Army Order 94 of 1927 in the case of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (Ambulance Car Corps), i.e. ‘…for service in any national emergency, either as a unit or, in the event of a Women’s Reserve being organized, as individual members of that reserve. The corps will receive no financial assistance from army funds.’

2. (Back) Edith Helen Vane-Tempest-Stewart D.B.E., Marchioness of Londonderry. (3 December 1878-23 April 1959.)

D.B.E. (Civil Division). Edith, Marchioness of Londonderry. Founder of the Women’s Legion. LG 24 August 1917; 30250, p. 8794. (Award transferred to the Military Division in LG 23 January 1920; 31750, p. 963.)

3. (Back) Miss Beatrice Gascoigne Ward O.B.E. (26 August 1876-14 October 1970.)

M.B.E. (Civil Division). Miss Beatrice Gascoigne Ward. Deputy Commandant, Motor Section, Women’s Legion. LG 1 January 1918; 30460, p. 407. (Award transferred to the Military Division in LG 15 April 1919; 31296, p. 4990.)

O.B.E. (Military Division). Miss Beatrice Gascoigne Ward. Assistant Commandant, Women’s Legion. LG 3 June 1919; 31377, p. 6994.

4. (Back) Not to be confused with the Women’s Section of the British Legion, also known colloquially as the ‘Women’s Legion’.

5. (Back) Mrs. Grace Muriel Cook (née Barnes; divorced 1920) (27 February 1881-1November 1970), a pre-war suffragette, was an Assistant Commandant in the Women’s Legion during the First World War responsible for the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers.

O.B.E. (Military Division). Assistant Commandant Grace Muriel Cook. Women’s Legion Motor Drivers, Army Service Corps. In recognition of valuable services rendered in connection with Military Operations in France and Flanders. L.G. 12 December 1919; 31684, p. 15452.

6. (Back) ‘Women Wanted To Man The Lorries’ Manchester Evening News, 3 January 1938.

7. (Back) Later Lieutenant General Sir John Brown K.C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O., T.D., J.P., D.L., F.R.I.B.A., F.R.I.C.S.

8. (Back) Women’s Legion, Mechanical Transport Section—Lady Londonderry;

Women’s Transport Service (F.A.N.Y.)—Mildred Hogg, Viscountess Hailsham and Commandant Miss Mary Baxter Ellis;

Voluntary Aid Detachment Council—Dame Beryl Oliver D.B.E., R.R.C., Lady Oliver and Ethel Perrott R.R.C., Lady Perrott;

Women’s Emergency Service—Dame Helen Gwynne Vaughan G.B.E.;

Women’s Section of the British Legion—Miss Dorothy Niven Gerds.

9. (Back) Aligned with the Civil Defence regions. Region 1 – Northern, Region 2 – North Eastern, Region 3 – North Midland, Region 4 – Eastern, Region 5 – London, Region 6 – Southern, Region 7 – South Western, Region 8 – Wales, Region 9 – Midland, Region 10 – North Western, Region 11 – Scotland, Region 12 – Northern Ireland.

10. (Back) A detailed study of the uniforms and badges of the M.T.C. is apparently provided here: Mills, J. (2008). Within the Island Fortress: The Uniforms, Insignia & Ephemera of the Home Front in Britain 1939-1945, No. 4: The Mechanised Transport Corps (MTC). (Orpington, Kent: Wardens Publishing, 2008). This is a rare book and I have not seen a copy.

11. (Back) Rank badges evolved into this arrangement:

Ensign—one star

Lieutenant—two stars

Captain—three stars

Commander—one gold bar with a rose above

Commandant—two golds bar with a rose above

Senior Commandant—one gold bar with a fleur de lis above

Staff Commandant—two gold bars with a fleur de lis above

The Corps Commandant—three gold bars with a fleur de lis above

12. (Back) Driver (Miss) Maisie Eirene Coppock and Driver (Mrs.) Mary Denise Goodbody, Air Raid Precautions, Lambeth. See M.T.C. Honours & Awards.

13. (Back) Being civilians, those who died in circumstances other than by enemy action are not commemorated by the C.W.G.C in any fashion. One other example is known: Miss Priscilla Corry Gotto, serving with the Ministry of Supply and travelling home to Belfast, was killed when United States Army Air Forces Boeing B-17-G Flying Fortress, serial 43-38847, en route from Stanstead to Royal Air Force Langford Lodge crashed at Dhustone Quarry, Clee Hill, Shropshire. All three crew-members and three passengers were killed. She is buried in Belfast City Cemetery, Glenalina Extension.

14. (Back) Driver (Miss.) Eileen Agnes Charlotte Knocker Driver is buried at Croydon Cemetery.

15. (Back) Ensign (Mrs.) Doris Lilian Eve Ellerbeck (née Hill) was cremated and her ashes buried in the grave of her husband’s grandfather at Chipperfield.

16. (Back) Driver (Mrs.) Florence Margaret ‘Molly’ Orton (née Fisher; widow of Sub-Lieutenant F. H. J. Orton, Royal Naval Reserve killed in action on 23 November 1939 when H.M.S Rawalpindi was sunk). Mrs. O. M. Sherington represented the M.T.C. at her funeral, although the place of burial is unknown. Her mother-in-law, Mrs. Bertha Orton, the leader of the theosophical ‘Group for Sacrifice and Service’ was killed in an air raid on 11 May 1941 at 43 York Terrace, where ninety-nine people prayed to the moon for peace; 14 others were killed.

17. (Back) Driver (Mrs.) Doreen Patricia Parley (née Moore; daughter of Major General Sir John Moore, K.C.M.G., C.B., F.R.C.V.S). The remains of Patricia Parley were not recovered until July 1948 during rebuilding work. She is buried with her mother and father at Quainton Churchyard, Buckinghamshire.

18. (Back) Organised nationally by the British Red Cross Society until taken over by the Emergency Medical Service of the Ministry of Health in 1940.

Part 1: The Early Years first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.

The Mechanised Transport Corps—Part 1: The Early Years

As part of a project looking at honours and awards to some of the women’s services, I came across an article about the award of the Croix de Guerre to British women volunteers of the Mechanised Transport Corps who had served with the French Army during the Battle of France in 1940. Intrigued I did a bit of digging but with little result—most of the available sources online are scanty in their detail and many conflate the various components of the M.T.C. As is often the case, a search of the British Newspaper Archive provided many good leads and those led to a visit to the Library of Congress to read some long-out-of-print memoires. This is the first of four articles about this most interesting volunteer organisation. For details of the honours and awards to the M.T.C. see here.

Edith, Marchioness of Londonderry D.B.E.

Founder of the Women’s Legion.

The Mechanised Transport Corps had its origins in the motor transport section of the Women’s Legion that remained independent after the formation of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in 1917; it served with great distinction in the United Kingdom and then in France after the Armistice. The section continued on a much smaller scale after the war and in 1927 the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers was recognised by the Army Council as a voluntary reserve transport unit and took its place on the Army List, albeit unfunded by the War Office.[1] Throughout the inter-war years, the President of the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers was Lady Londonderry[2] (the founder of the Women’s Legion) and its secretary was Miss B. G. Ward O.B.E.,[3] both of whom had been recognised for their service during the First World War. In 1937 it was renamed Women’s Legion Mechanical Transport Section.

Women’s Legion Motor Drivers, 1918

Prior to the Second World War, in July 1937 Lady Londonderry proposed a ‘new’ Women’s Legion.[4] Beginning as an extension of the Women’s Legion Mechanical Transport Section, it began training in anti-gas drills, first aid, map reading and signalling at Regent’s Park Barracks in November that year. Aged between 18 and 40, its members were required to have a clean driving licence, paid a subscription upon enrolment and purchased their own uniforms. The unit established at Regents Park became No. 1 Company and was led by Mrs. G. M. Cook O.B.E., a driving force behind the transport section in the earlier war.[5] Early success led to a plan in January 1938 to expand the organisation to provide many more women capable of driving commercial transport in the event of a national emergency and recruitment soon began in earnest. Miss Ward commented, ‘There is no difficulty in finding women who can drive lorries… they are quite capable of driving large ambulances and lighter lorries. During the war they did it and they would be able to do it again.’[6]

Mrs. G. M. Cook O.B.E

Corps Commandant, Mechanised Transport Corps

On 6 May 1938, at a meeting chaired by Major General Sir John Brown,[7] Deputy Director General Territorial Army, and attended by representatives of the principal women’s voluntary emergency organisations,[8] the foundation was laid for the formation of what would become the Auxiliary Territorial Service, the women’s branch of the British Army. The formation of the A.T.S was announced in September 1938 and it quickly subsumed the various women’s organisations with the exception of the Women’s Legion Mechanical Transport Section which was able to maintain its independence as a volunteer organisation.

With its headquarters at 33 Leinster Gardens, Bayswater and under Mrs. Cook’s leadership it began further recruitment. It was renamed the Mechanised Transport Training Corps in early 1939 but in early 1940 ‘Training’ was dropped from its title. The M.T.C. expanded quickly and at its height comprised over 3,000 personnel organised into companies in 12 regions.[9] It proved very popular with women ineligible for service with the armed forces and married women with family commitments.

The women of the M.T.C were uniformed in the style of A.T.S. officers (which caused some controversy) with their uniforms piped in blue.[10] A distinctive badge was worn on the uniform cap and tunic lapels. The brass cap and lapel badges of the M.T.T.C. comprised crossed open-ended spanners on top of a vehicle tyre with the letters ‘M’ & ‘T’ on the top spanner ends and ‘T’ & ‘C’ on the bottom spanner ends. On the lower edge of the tyre was the motto ‘PRO PATRIA’ (‘For One’s Country’). After the change of name, the second ‘T’ was removed and the ‘C’ moved to the centre of the crossed spanners. Buttons were plain with an embossed fleur-de-lis under the letters ‘M T C’. In time, several different armbands, badges and lapel flashes were worn by components of the M.T.C. linking them to the organisation for which they worked or to indicate wartime service in France. Officers’ rank badges were a combination of five-pointed stars, roses and gold bars.[11] (See the gallery below.)

In the early part of the Second World War the M.T.C. provided drivers for Civil Defence organisations and the Home Guard. Notable amongst the former were the women of an M.T.C. company who volunteered to drive the Lambeth Borough Council Air Raid Precautions’ stretcher parties. Two drivers, Maisie Coppock and ‘Denny’ Goodbody,[12] were awarded the British Empire Medal for their bravery in the aftermath of an air raid. The incident occurred at 7.45p.m. on 15 October 1940 at Morley College, Westminster Bridge Road in Lambeth, which was being used as an emergency rest centre by Lambeth Borough Council and at the time of the attack held 193 people, many of whom had lost their homes. It was struck by a single bomb that demolished much of the structure and killed 57 people. Three men of an A.R.P. stretcher party and the two drivers dug a tunnel with their hands and freed about 14 people, passing them from one to another. Later, Goodbody was separated from the group and assisted a rescue party that had made a tunnel that was too small for any of the men to get through. She volunteered to try and was able to wriggle through to a trapped woman but heavy rubble resting prevented her rescue; the woman was extracted later after another opening was made. The three men of the stretcher party were also awarded the B.E.M.

Mr. Richard Rance B.E.M., Mr. Norman Jaeger B.E.M. (Leader), Mrs. Mary Denise Goodbody B.E.M. and Mr. Alexander Muirhead Kerr B.E.M.; Air Raid Precautions, Lambeth

No fewer than four women of the M.T.C. were killed during the Blitz, recorded as ‘Civilian War Dead’ by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission:[13]

Eileen Knocker,[14] a nurse and midwife who had served in France during the First World War with a Voluntary Aid Detachment, was killed at Trebovir Road, Earl’s Court during an air raid on 24 September 1940; 10 others were killed in the blast.

Mrs. Eve Ellerbeck,[15] an assistant company leader based at No. 2 Stretcher Party Station, South Lambeth Road School, was killed in an air raid on 5 November 1940 when the station was hit; eight A.R.P. stretcher bearers stationed there were also killed, as were several civilians taking shelter.

Mrs. ‘Molly’ Orton,[16] and Mrs. Patricia Parley[17] were killed in an air raid on 17 February 1941 when a bomb hit the house on South End Road, Hampstead in which they were staying with Parley’s mother, Adelaide, Lady Moore who was also killed, as was the housekeeper Mrs. Rebecca Henry.

Elsewhere during the Blitz, the organisation provided a considerable number of drivers for American Ambulance Great Britain, a fleet of vehicles paid for by donors in the United States that provided ambulances, mobile first aid posts and mobile surgical teams in areas suffering air raids. By the end of the war the responsibility for running the organisation’s 27 stations was split almost equally between the M.T.C. and A,A.G.B. The M.T.C. also drove for the Queen’s Messenger Convoys (the ‘Food Flying Squad’) made up of vehicles, mostly donated by the British War Relief Society of America, managed by the Ministry of Food and staffed by the Women’s Voluntary Service that provided canteen services in bombed towns and cities. By November 1941 22 convoys were in operation, each comprising three mobile canteens, two food lorries, two kitchen lorries, a water carrier and a staff liaison car.

W.V.S. and their M.T.C. drivers of the Queen’s Messengers Convoy.

Increasingly, drivers were provided for various government ministries, the Blood Transfusion Service,[18] and the exiled governments and forces of Allied nations, notably for elements of the United States forces that began to arrive in 1942. The highest profile of these was probably Mrs. K. H. M. ‘Kay’ Summersby who drove for General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, earning her the British Empire Medal.

While well-regarded in Great Britain in the early years of the war (although as will be seen in a later article, not without some criticism), it would be the accolades earned during the Battle of France that would cement the reputation of the M.T.C.

Part 2—The Battle of France. (To follow.)

1. (Back) Army Order 180 of 1927 recognised the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers on the same terms as those approved by Army Order 94 of 1927 in the case of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (Ambulance Car Corps), i.e. ‘…for service in any national emergency, either as a unit or, in the event of a Women’s Reserve being organized, as individual members of that reserve. The corps will receive no financial assistance from army funds.’

2. (Back) Edith Helen Vane-Tempest-Stewart D.B.E., Marchioness of Londonderry. (3 December 1878-23 April 1959.)

D.B.E. (Civil Division). Edith, Marchioness of Londonderry. Founder of the Women’s Legion. LG 24 August 1917; 30250, p. 8794. (Award transferred to the Military Division in LG 23 January 1920; 31750, p. 963.)

3. (Back) Miss Beatrice Gascoigne Ward O.B.E. (26 August 1876-14 October 1970.)

M.B.E. (Civil Division). Miss Beatrice Gascoigne Ward. Deputy Commandant, Motor Section, Women’s Legion. LG 1 January 1918; 30460, p. 407. (Award transferred to the Military Division in LG 15 April 1919; 31296, p. 4990.)

O.B.E. (Military Division). Miss Beatrice Gascoigne Ward. Assistant Commandant, Women’s Legion. LG 3 June 1919; 31377, p. 6994.

4. (Back) Not to be confused with the Women’s Section of the British Legion, also known colloquially as the ‘Women’s Legion’.

5. (Back) Mrs. Grace Muriel Cook (née Barnes; divorced 1920) (27 February 1881-1November 1970), a pre-war suffragette, was an Assistant Commandant in the Women’s Legion during the First World War responsible for the Women’s Legion Motor Drivers.

O.B.E. (Military Division). Assistant Commandant Grace Muriel Cook. Women’s Legion Motor Drivers, Army Service Corps. In recognition of valuable services rendered in connection with Military Operations in France and Flanders. L.G. 12 December 1919; 31684, p. 15452.

6. (Back) ‘Women Wanted To Man The Lorries’ Manchester Evening News, 3 January 1938.

7. (Back) Later Lieutenant General Sir John Brown K.C.B., C.B.E., D.S.O., T.D., J.P., D.L., F.R.I.B.A., F.R.I.C.S.

8. (Back) Women’s Legion, Mechanical Transport Section—Lady Londonderry;

Women’s Transport Service (F.A.N.Y.)—Mildred Hogg, Viscountess Hailsham and Commandant Miss Mary Baxter Ellis;

Voluntary Aid Detachment Council—Dame Beryl Oliver D.B.E., R.R.C., Lady Oliver and Ethel Perrott R.R.C., Lady Perrott;

Women’s Emergency Service—Dame Helen Gwynne Vaughan G.B.E.;

Women’s Section of the British Legion—Miss Dorothy Niven Gerds.

9. (Back) Aligned with the Civil Defence regions. Region 1 – Northern, Region 2 – North Eastern, Region 3 – North Midland, Region 4 – Eastern, Region 5 – London, Region 6 – Southern, Region 7 – South Western, Region 8 – Wales, Region 9 – Midland, Region 10 – North Western, Region 11 – Scotland, Region 12 – Northern Ireland.

10. (Back) A detailed study of the uniforms and badges of the M.T.C. is apparently provided here: Mills, J. (2008). Within the Island Fortress: The Uniforms, Insignia & Ephemera of the Home Front in Britain 1939-1945, No. 4: The Mechanised Transport Corps (MTC). (Orpington, Kent: Wardens Publishing, 2008). This is a rare book and I have not seen a copy.

11. (Back) Rank badges evolved into this arrangement:

Ensign—one star

Lieutenant—two stars

Captain—three stars

Commander—one gold bar with a rose above

Commandant—two golds bar with a rose above

Senior Commandant—one gold bar with a fleur de lis above

Staff Commandant—two gold bars with a fleur de lis above

The Corps Commandant—three gold bars with a fleur de lis above

12. (Back) Driver (Miss) Maisie Eirene Coppock and Driver (Mrs.) Mary Denise Goodbody, Air Raid Precautions, Lambeth.

13. (Back) Being civilians, those who died in circumstances other than by enemy action are not commemorated by the C.W.G.C in any fashion. One other example is known: Miss Priscilla Corry Gotto, serving with the Ministry of Supply and travelling home to Belfast, was killed when United States Army Air Forces Boeing B-17-G Flying Fortress, serial 43-38847, en route from Stanstead to Royal Air Force Langford Lodge crashed at Dhustone Quarry, Clee Hill, Shropshire. All three crew-members and three passengers were killed. She is buried in Belfast City Cemetery, Glenalina Extension.

14. (Back) Driver (Miss.) Eileen Agnes Charlotte Knocker Driver is buried at Croydon Cemetery.

15. (Back) Ensign (Mrs.) Doris Lilian Eve Ellerbeck (née Hill) was cremated and her ashes buried in the grave of her husband’s grandfather at Chipperfield.

16. (Back) Driver (Mrs.) Florence Margaret ‘Molly’ Orton (née Fisher; widow of Sub-Lieutenant F. H. J. Orton, Royal Naval Reserve killed in action on 23 November 1939 when H.M.S Rawalpindi was sunk). Mrs. O. M. Sherington represented the M.T.C. at her funeral, although the place of burial is unknown. Her mother-in-law, Mrs. Bertha Orton, the leader of the theosophical ‘Group for Sacrifice and Service’ was killed in an air raid on 11 May 1941 at 43 York Terrace, where ninety-nine people prayed to the moon for peace; 14 others were killed.

17. (Back) Driver (Mrs.) Doreen Patricia Parley (née Moore; daughter of Major General Sir John Moore, K.C.M.G., C.B., F.R.C.V.S). The remains of Patricia Parley were not recovered until July 1948 during rebuilding work. She is buried with her mother and father at Quainton Churchyard, Buckinghamshire.

18. (Back) Organised nationally by the British Red Cross Society until taken over by the Emergency Medical Service of the Ministry of Health in 1940.

February 7, 2025

Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals

Following the announcement of the New Year Honours list, I have updated the Addendum to Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals. It includes the awards announced at the end of last year and also some new information. Most of the new information comprises the identification of units of men mentioned in despatches that has been gleaned from war diaries found in the Indian National Archives – Abhilekh Patal. This is an extraordinary treasure trove of information but the website is clunky and needs patience,

The pdf is available to download midway down this page.

The post Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.July 31, 2024

Operation Varsity, The Rhine Crossing—Royal Signals & United States 17th Airborne Division

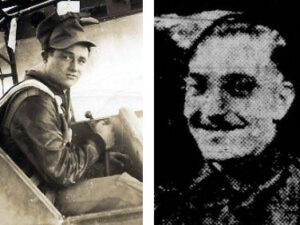

1st Lieutenant Arnold L. Holt

Material provided to me by the grandson of Lieutenant Arnold L. Holt, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, United States Army Air Forces created a route to a treasure trove of information from various sources that allows a more complete story to be told of the fate of some of the Royal Signals participants on Operation Varsity in March 1945.

Operation Varsity was the airborne component of the Rhine crossing (Operation Plunder) and was concentrated on the capture of the Diersfordter Wald near the village of Hamminkeln. It was conducted by United States XVIII Corps (Airborne). The British 6th Airborne Division landed by parachute and by glider at drop zones and landing zones in the north of the area and the United States 17th Airborne Division landed in the south.

Detachments of Royal Signals soldiers from 1st Airborne Corps Signals attached to No. 2 Air Support Signal Unit were landed by glider to support both divisions.[1] The use of British signallers by 17th Airborne Division was necessitated by the use of the British Second Tactical Air Force[2] for close air support. The No. 2 ASSU ‘tentacles’ (radio detachments) provided links to Headquarters Second Army and to the Group Control Centres of Second Tactical Air Force. No. 2 ASSU also provided a radio detachment at Headquarters XVIII Corps (Airborne).

In addition it was planned that each division would have a Forward Visual Control Point for the control of close air support. As a result of lessons learned from previous airborne operations, 100% spares were generated to mitigate losses. Six FVCP (each comprising two Royal Air Force officer controllers and two or three radio operators) were generated for Operation Varsity to guarantee one FVCP for each division and one spare. In addition to providing radio communications to divisional headquarters (operations and artillery staffs), the FVCP could join a brigade forward observation officer net. In broad terms, an ASSU tentacle communicated rearward (tasking) and upward (to pilots), and an FVCP upward (to pilots) and forward (to units in contact). The Waco CG4 glider was not big enough to carry a Jeep and the two-wheeled communications trailer. In consequence, all of the FVCPs were to land in the 6th Airborne Division area (Landing Zone ‘R’) in Horsa gliders, with those allocated to 17th Airborne Division ordered to drive to the divisional headquarters after the area around the landing zones was secure.[3]

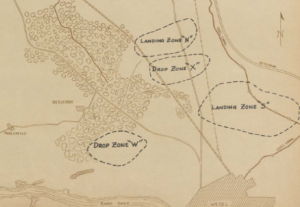

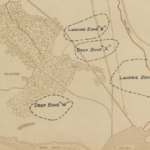

The 17th Airborne Division glider assault would be split over two landing zones. ‘N’ was the northern LZ and lay on the divisional boundary. To its south was Drop Zone ‘X’ and south-east of DZ ‘X’ was LZ ‘S’. The ASSU tentacles were destined for LZ ‘N’. Also landing on LZ ‘N’ were the gliders carrying the divisional signals—517th Signal Company, commanded by Captain David O. Jesberg.

17th Airborne Division Drop & Landing Zones

Eighty of the 314 gliders allocated to Landing Zone ‘N’ were from 314th Troop Carrier Group and would fly in two serials from airfield ‘B-44’ at Poix in France, where it had arrived three weeks earlier from RAF Saltby.[4] Those flying serials comprised:[5]

A-21:

Chalk Nos. 1-20 (62nd Troop Carrier Squadron)

Chalk Nos. 21-40 (61st Troop Carrier Squadron)

A-22:

Chalk Nos. 41-60 (32nd Troop Carrier Squadron)

Chalk Nos. 61-80 (50th Troop Carrier Squadron)

Two air liaison officers and three ASSU tentacles, each of three Royal Signals soldiers from 1st Airborne Corps Signals, joined 17th Airborne Division in France for training on the Waco glider and for the organisation of loads.[6] They were airlifted to LZ ‘N’ by eight gliders—Chalk Nos. 30-37—with Jeeps and communications trailers split between gliders. In addition, Chalk No. 80 carried a detachment from General Headquarters Liaison Regiment (Phantom).

Very heavy ground fire resulted in severe casualties amongst the glider crews of chalks 30-37 and the passengers from 1st Airborne Corps Signals:

Chalk No. 30[7]

Pilot: O-524959 1st Lieutenant Gene Evans Canova, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Co-pilot: O-780951 2nd Lieutenant Bruce Hoitt, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Passengers: 89306 Captain Oswald Barry Stannus Gray,[8] The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), Air Liaison Officer, and 14345928 Lance Corporal Frank Brookes Walker, 1st Airborne Corps Signals.

Lance Corporal Walker and Captain Barry Gray were aboard Waco CG-4A glider, serial 43-41167, designated Chalk No. 30 in Serial A-21, flown by 1st Lieutenant Gene E. Canova with 2nd Lieutenant Bruce Hoitt as co-pilot. The glider was hit by ground fire during the landing and then subject to machine-gun and mortar fire. 1st Lieutenant Canova was killed in action by mortar fire as he left the glider; Captain Gray and Lance Corporal Walker were also killed in action about this time. 2nd Lieutenant Hoitt was wounded in the chest and face but was found by United States forces and evacuated; he survived the war.

1st Lieutenant Gene E. Canova is buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten. Captain O. B. S. Gray and Lance Corporal F. B. Walker were originally buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery; their remains were reinterred on 29 and 28 April 1947, respectively, at Venray War Cemetery, Netherlands.

Chalk No. 31

Pilot: T-60427 Flight Officer Lyle Evans Holland, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Co-Pilot: T-6198 Flight Officer Thomas Owen McCay, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Passengers: Not identified.

Waco CG-4A glider, serial 43-39825, designated Chalk No. 31 in Serial A-21, flown by Flight Officer Lyle E. Holland with Flight Officer Thomas O. McCay as co-pilot, landed in the centre of LZ ‘N’. Flight Officers Holland and McCay survived the landing and the war.

Chalk No. 32[9]

Pilot: T-60411 Flight Officer Clement Anthony Casella, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Co-Pilot: T-60424 Flight Officer Francis Jackson Hanner, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Passengers: 2591081 Corporal John Stell Glassford, 1st Airborne Corps Signals and 5954299 Signalman Edward Thomas Beddington, 1st Airborne Corps Signals.

Corporal J. S. Glassford, 1st Airborne Corps Signals (left) after landing by glider at LZ ‘N’ during Operation Varsity. Like all of the British detachments that landed with 17th Airborne Division, he is wearing US uniform and equipment but with his own helmet and carrying a Mark V Sten gun.

This photograph is part of a series that includes Corporal Glassford, taken by a United States Army Signal Corps photographer (see the gallery below).

Corporal Glassford and Signalman Beddington were aboard Waco CG-4A glider, serial 43-40163, designated Chalk No. 32 in Serial A-21, flown by Flight Officer Clement A. Casella with Flight Officer Francis J. Hanner as co-pilot. Flight Officer Casella and Flight Officer Hanner were killed in action by ground fire; the location of their landing site is not known but it was probably on 6th Airborne Division’s LZ ‘R’. Corporal Glassford and Signalman Beddington survived and were able to complete their task. For his gallantry during the operation Corporal J. S. Glassford was awarded the Military Medal:[10]

Corporal Glassford throughout the whole of the operation commencing on 24th March, when he flew in with 17th (United States) Airborne Division, gave a magnificent performance of efficiency and coolness under enemy fire. Having extricated himself from his glider, which was set on fire by a direct hit, he succeeded in reaching the correct rendezvous, without a map and under heavy enemy shell and mortar fire. He established contact with the rest of his party and then immediately made several patrols into areas held by the enemy to locate other gliders containing signal equipment vital to the success of air support communications. Having done this and being the senior NCO remaining alive, he organised the establishment of his radio set. Throughout the succeeding days he never lost contact with Headquarters Second Army and air support could therefore be provided. By his bravery and devotion to duty he set a superb example to others.

The remains of Flight Officer Clement A. Casella were repatriated and reinterred at Long Island National Cemetery. Flight Officer Francis J. Hanner is buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten.

Chalk No. 33

Pilot: T-120251 Flight Officer Fredric Daniel Manget, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Co-Pilot: T-64962 Flight Officer Fred B. Lewis, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Passengers: Not identified. (It is possible, given that the casualties from all this chalk occurred immediately upon landing, that the Royal Signals passenger was Corporal J. Beresford—see table below.)

Waco CG-4A glider, serial 42-56296, designated Chalk No. 33 in Serial A-21, flown by Flight Officer Fredric D. Manget with Flight Officer Fred B. Lewis as co-pilot, landed in the southern part of LZ ‘N’. The aircrew were killed in action by ground fire while still strapped in their seats.

Flight Officer Fredric D. Manget is buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten. The remains of Flight Officer Fred B. Lewis were repatriated and reinterred at Rose Hill Cemetery, Humboldt, Gibson County, Tennessee.

Chalk No. 34

Pilot: T-136236 Flight Officer Don Floyd Conover, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Co-Pilot: T-120429 Flight Officer Herbert Peter Holkestad, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Passengers: Not identified.

Waco CG-4A glider, serial 43-37443, designated Chalk No. 34 in Serial A-21, flown by Flight Officer Don F. Conover with Flight Officer Herbert P. Holkestad as co-pilot, landed at the western end of DZ ‘X’. Flight Officers Conover and Holkestad survived the landing and the war.

Chalk No. 35[11]

Pilot: T-124233 Flight Officer Max Lee Hunt, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Co-pilot: O-780956 2nd Lieutenant Arnold Lester Holt, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Passengers: 4860807 Lance Corporal Arthur Oldham, 1st Airborne Corps Signals and 5438169 Lance Corporal Leslie Albert Norman Watkins, 1st Airborne Corps Signals.

Lance Corporal Oldham and Lance Corporal Watkins with a communications trailer were aboard Waco CG-4A glider, serial 43-40591, designated Chalk No. 35 in Serial A-21 flown by Flight Officer Max L. Hunt with 2nd Lieutenant Arnold L. Holt as co-pilot. The glider was hit by ground fire during the landing and then subject to machine-gun and mortar fire; the landing site is not known. Soon after landing Lance Corporals Oldham and Watkins were killed in action by machine-gun fire (one man in the act of surrendering) and Flight Officer Hunt was killed by mortar fire. 2nd Lieutenant Holt was severely wounded by mortar fire and, after being cared for by a local German family, was found by United States forces and evacuated; he survived the war. (See this account by Arnold L. Holt.)

Flight Officer Max L. Hunt & Lance Corporal Arthur Oldham

Flight Officer Max L. Hunt is buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten. Lance Corporal A. Oldham and Lance Corporal L. A. N. Watkins were originally buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery; their remains were reinterred on 28 April 1947 at Venray War Cemetery, Netherlands.

Chalk No. 36[12]

Pilot: T-136240 Flight Officer Thomas E. Daugherty, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Co-pilot: O-2067055 Second Lieutenant Morton Hassman, 61st Troop Carrier Squadron, 314th Troop Carrier Group, United States Army Air Forces.

Passenger: 14668835 Signalman Derrick Berry, 1st Airborne Corps Signals.

Signalman Derrick Berry

Signalman Berry with a communications trailer was aboard Waco CG-4A glider, serial 43-36788, designated Chalk No. 36 in Serial A-21, flown by Flight Officer Thomas E. Daugherty with Second Lieutenant Morton Hassman, a C-47 pilot, as co-pilot. The signal detachment’s Jeep was in a preceding glider. Both gliders were hit by ground fire during the landing and then subject to machine-gun and mortar fire. Immediately after landing, Signalman Berry was killed in action by mortar fire while inside the glider. Second Lieutenant Hassman was severely wounded and, although treated by a German medic, died soon after landing. Flight Officer Daugherty was wounded but survived; he escaped captivity and rejoined United States forces near the landing zone; he survived the war. (See this report by Thomas E. Daugherty.)

Second Lieutenant Mortan Hassman is buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten. Signalman D. Berry was originally buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery; his remains were reinterred on 1 April 1947 at Venray War Cemetery, Netherlands.

Chalk No. 37

Pilot: Not identified.

Co-Pilot: Not identified.

Passengers: Not identified.

Glider serial: Not identified. Landed at the southern end of DZ ‘X’ with Chalks 38-40.

Amongst the other passengers carried in these chalks were:

2315996 Corporal James Beresford, 1st Airborne Corps Signals. Killed in action on 24 March 1945 at LZ ‘N’. Originally buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten, his remains were reinterred on 28 April 1947 at Venray War Cemetery, Netherlands.

2569563 Corporal William Ainsworth, 1st Airborne Corps Signals. Wounded in action on 28 March 1945 at or near LZ ‘N’. Awarded the Bronze Star Medal:[13]

Corporal William Ainsworth was non-commissioned officer in charge of a tentacle with Headquarters 17th United States Airborne Division during the operations immediately following the crossing of the Rhine and was wounded in the arm by enemy shell fire. He, nevertheless, remained at his post and maintained communications without interruption. Throughout his attachment to Headquarters 17th United States Airborne Division he gave a valuable service both in the performance of his normal duties and also in liaison duties with the air staff of the division.

A second, British Air Liaison Officer (unidentified).

One Royal Signals other rank (a Signalman) (unidentified).[14]

Summary of Air Support Signal Unit Personnel Attached To 17th Airborne Division

Captain O. B. S. Gray, Air Liaison Officer (killed in action), Chalk No. 30

Air Liaison Officer No. 2 (unidentified), Chalk No. NK

Corporal W. Ainsworth (wounded), Chalk No. NK

Corporal J. Beresford (killed in action), Chalk No. NK

Corporal J. S. Glassford MM, Chalk No. 32

Lance Corporal A. Oldham (killed in action), Chalk No. 35

Lance Corporal F. B. Walker (killed in action), Chalk No. 30

Lance Corporal L. A. N. Watkins (killed in action), Chalk No. 35

Signalman E. T. Beddington, Chalk No. 32

Signalman D. Berry (killed in action), Chalk No. 36

One Royal Signals other rank (a Signalman), Chalk No. NK

Acknowledgements:

The family of Arnold L. Holt for his report and photographs.

The National WWII Glider Pilots Association for the report by Thomas E. Daugherty.

1st Airborne Corps Signals on the landing zone:

1. (Back) The ‘tentacles’ were attached to No. 2 Air Support Signal Unit from 1st Airborne Corps Signals for this task, rather than them being integral to No. 2 Air Support Signal Unit.

2. (Back) In addition to the Royal Air Force squadrons, Second Tactical Air Force had Australian, Belgian, Canadian, Czech, French, New Zealand, Norwegian and Polish squadrons.

3. (Back) In the 6th Airborne Division area, the divisional air staff officer (the ‘G2 (Air)’ i.e. Staff Officer Grade 2 (Air)) acted as air liaison officer and joined its FVCP. The 6th Airborne Division FVCP was in operation a little under two hours after landing. The 17th Airborne Division FVCP reached the divisional headquarters at 11.00 hours on D+1 and was in operation soon afterwards.

4. (Back) Vlahos, M. C. The Rhine Crossing – 314th Troop Carrier Group. Silent Wings Museum Newsletter, Vol. 19, No. 3, Spring 2020, pp. 8-11. (See also Vlahos, M. C. (2019). “Men Will Come” A History of the 314th Troop Carrier Group 1942-1945. Self-Published: Lulu.)

5. (Back) For a breakdown of flying serials and their component units see United States Army. (July 1945). 17th Airborne Division Historical Report of Operation Varsity. Annex 2—Air Movement Table (Glider).

6. (Back) United States Army. (July 1945). 17th Airborne Division Historical Report of Operation Varsity. p. 35.

The war diary of 6th Airborne Divisional Signals records the arrival at Bulford of 6th Airborne Division’s four ASSU tentacles on 16 March 1945: ‘1800—ASSU tentacles arrive. 1 Sgt, 12 Operators. 4 Jeeps and trailers’. (United Kingdom National Archives (UKNA), WO 171/4163. War Diary 6th Airborne Divisional Signals, March 1945.)

7. (Back) United States National Archives & Records Administration; Record Group 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General; Series: Missing Aircrew Reports; 43-41167.

8. (Back) Mentioned in despatches for his earlier conduct during the North-West Europe Campaign. London Gazette 8 May 1945; 37072, p. 2462.

9. (Back) United States National Archives & Records Administration; Record Group 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General; Series: Missing Aircrew Reports; 43-40163.

10. (Back) London Gazette 12 July 1945; 37172, p. 3594. (Incorrectly published as ‘John Still Glassford’.) Recommendation: UKNA, WO 373/54/913.

11. (Back) United States National Archives & Records Administration; Record Group 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General; Series: Missing Aircrew Reports; 43-40591.

12. (Back) United States National Archives & Records Administration; Record Group 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General; Series: Missing Aircrew Reports; 43-36788.

13. (Back) London Gazette 17 October 1946; 37761, p. 5140. Recommendation: UKNA, WO 373/147/461.

14. (Back) There were three other casualties from 1st Airborne Corps Signals on Operation Varsity (noting that 1st Airborne Corps Signals also supported 6th Airborne Division): 837517 Corporal A. J. Axam, 1st Airborne Corps Signals was wounded on 24 March 1945; 2380510 Signalman Derrick Connop was wounded in action on 25 March 1945; and 5346039 Signalman William Alfred Ford died of wounds on 28 March 1945. Given the rank structure of the tentacles, however, either Signalman Connop or Signalman Ford could be the missing signaller with 17th Airborne Division. The missing signaller could, however, have survived unwounded and his name remain unrecorded.

Royal Signals & United States 17th Airborne Division first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.

July 18, 2024

Commemorating Royal Signals War Dead – New Page, ‘B’

The Royal Signals casualties whose surnames begin with ‘B’ have now been included on the War Dead page on this website (the document opens as a pdf).