Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 3

September 27, 2022

Signalman Arnold Osmond Topliff BEM

Arnie Topliff was one of only two men to earn a gallantry award in the aftermath of the sinking of the prisoner of war transport SS Lisbon Maru in October 1942. His award of the British Empire Medal was one of 56 to Royal Signals soldiers during the Second World War for acts of gallantry.

Signalman Arnie Topliff BEM

The eldest of two sons and two daughters, he was born in Derby on 9 March 1919. He started school there before the family moved to a small-holding in Quarndon.[1] Arnie was a keen sportsman, representing the village at cricket and football, and a strong swimmer. He was also a chorister in the parish church, St Paul’s. His father had served with the Royal Navy before, during and after the First World War, initially on battleships and later as a submariner[2] and after the war he joined Derby Corporation Electrical Department. When he left school, Arnie Topliff also joined the Derby Corporation, as an electrical cable joiner. It was natural, therefore, that when he enlisted on 6 December 1939 and joined Royal Signals he became a lineman. During his training early in 1940 Arnold Topliff married Nellie Moseley. After his training he was posted to the Far East, to the Hong Kong Signal Company.

On 8 December 1941, the Japanese attacked Hong Kong. After 17 days of hard fighting the garrison surrendered; approximately 11,000 men went into captivity on or near the island. In late-September 1942, over 1,800 men were moved aboard the cargo ship SS Lisbon Maru destined for labour camps in Japan. On 1 October, in the East China Sea the Lisbon Maru was hit by a torpedo fired by the United States submarine USS Grouper; she sank the next day. In the course of the aftermath, Arnie Topliff rescued an officer of the Middlesex Regiment in most gruelling circumstances—the story of the Hong Kong Signal Company and the Lisbon Maru may be read here.

The survivors from the Lisbon Maru were shipped first to a camp near Shanghai and then on the Shinsei Maru to Osaka in Japan. ‘Topper’ Topliff, as he became known, spent most of his captivity at Osaka Main Camp No. 1B. The camp, called ‘Honjo’ or ‘Chikko’ and known by many of the prisoners as ‘Hoincho’, was established in September 1942 with the arrival of 150 men from another camp. On 11 October, around 500 survivors of the Lisbon Maru arrived. The camp was established to provide a workforce of stevedores for the commercial transportation companies using the nearby port. A detailed description of the camp and the role of the prisoners may be found in the report for the Supreme Commander Allied Powers written in February 1946.

In May 1945, Topliff was amongst a group from Osaka transferred to the small branch camp Notogawa (Camp No. 9B), which was on the shore of Lake Biwa near Notogawa Station in Shiga Prefecture, about 30 miles north-east of Kyoto. Here the prisoners—Americans, Australians, British and Dutch—were engaged in dike and canal construction to create rice fields. As had been the case at Osaka, conditions were harsh, the food was poor, and the two barracks were over-crowded.

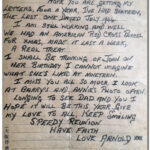

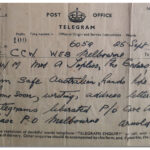

The camp was abandoned by the Japanese guards just after the end of the war. During the planning for the Allied occupation of Japan—Operation Blacklist—work had been undertaken to locate where prisoners of war and civilian internees were being held and to plan a series of airdrops to provide them with food and essential equipment, prior to their recovery and repatriation. By the end of September 1945 almost all the 32,000 prisoners in Japan were on their way home. Most of the British and Australian prisoners were taken to Australia and Arnie Topliff arrived in Melbourne in mid-September. One of the first things that he did was to telegram his parents to let them know that he was safe.

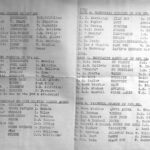

The repatriation of Arnold Topliff and others to Australia, September 1945

Signalman Topliff’s BEM was announced in the London Gazette in March 1946. He was demobilised on 1 May that year and returned home to Quarndon. His medal was sent to him in the post (a common practice) in April 1947. His other medals for his war service were the 1939-45 Star, Pacific Star, British War Medal 1939-45, and Defence Medal. He went to work with the East Midlands Electricity Board, where he became a mains foreman, and he was a regular attendee at Royal Signals and Prisoners of War reunions. His marriage to Nellie did not last and the couple were divorced in June 1947. More happily, in early 1951 Arnold Topliff married Evelyn Sturgess and the couple had a son, Ian, born in 1957.[3] Tragically, Arnold Topliff BEM died suddenly of a heart attack on 24 December 1969, aged only 50. Typically of the man, he had been into work only hours before to check on ‘his blokes’ in Derby who were working on an electricity breakdown in the town and were struggling to reconnect the power in time for Christmas Day. He was buried at St Pauls’ Church, Quarndon. Evelyn died in 1982.

here, reel three, at 14.55). The sign-off ‘tak san benjo’ translates roughly (in prisoner vernacular) as ‘a lot of crap’.

here, reel three, at 14.55). The sign-off ‘tak san benjo’ translates roughly (in prisoner vernacular) as ‘a lot of crap’.Photo: Topliff family.

" data-image-caption="Reunion letter from fellow prisoner George Bainborough, May 1963

" data-medium-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." /> here.

here.Photo: Topliff family.

" data-image-caption="George Harry Bainborough, Royal Navy

" data-medium-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." />

1. (Back) Ernest Osmond Topliff (18 June 1895-October 1970) married Annie Elizabeth Lynch (13 September 1894-September 1972) at Holy Trinity Church, Derby on 11 February 1917. Both are buried at St Pauls’ Church, Quarndon. The couple had another son who died in infancy.

2. (Back) After serving on the battleships HMS Renown, HMS Revenge (both pre-war) and HMS Dreadnought, Able Seaman Topliff (a 1st Class Stoker) retrained as a submariner in 1916 and served on the submarine C-13. He was based in various submarine service depot ships in the war (HMS Dolphin, HMS Bonaventure, and HMS Titania) and at the end of the war was posted to the minesweeper HMS Hebe. He joined the submarine K-22 on 4 February 1919, and then submarine H-23 in September 1922, which was his last boat. He was rated as a Leading Stoker in 1923, posted ashore in April 1924 and transferred to the Royal Fleet Reserve in August 1924. He was awarded the Royal Fleet Reserve Long Service Medal in 1928 to add to his 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-20, and Victory Medal.

3. (Back) Mary Evelyn Sturgess (2 February 1925-26 January 1982).

July 23, 2022

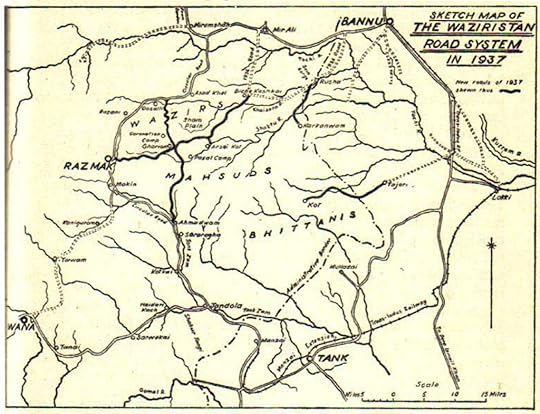

The Shahur Tangi Ambush, Waziristan, 1937

This blog post originally appeared in 2018 on my website dealing with Royal Signals honours and awards. With the closure of that site I have updated it (substantially) and moved it here. More details on the casualties may be found in the blog post about Manzai Fort cemetery.

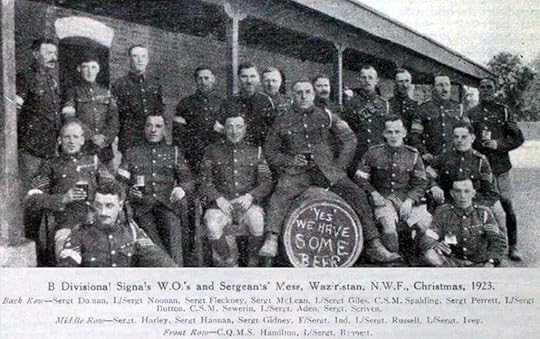

Operations in Waziristan and elsewhere on the North-West Frontier of India, earned for Royal Signals some of its very first awards for gallantry—the earliest in the 1920s are dealt with in the chapter of the book that deals with the Meritorious Service Medal for gallantry.

By 1924 conflict in the region had largely abated but a British and Indian Army garrison remained to piquet the roads that had been built between small population centres as a means of increasing control of the tribal area. Such duties were not without danger. On 18 August 1924, during a road opening operation north of Razmak Narai, near Duncan’s Piquet, a vehicle carrying a small Royal Signals party from Razani was ambushed below the picquet. In the action that followed, Lance Sergeant Percy Cook, aged 23, was killed and Signalman C. Punter and an Indian signaller were wounded.[1] This incident was the subject of the Corps painting Frontier Ambush by Peter Archer.[2]

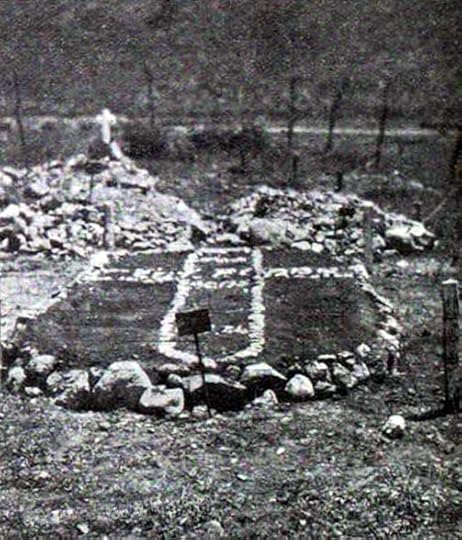

The grave of Lance Serjeant Percy Everitt Cook, Razmak

Less well known, certainly in Royal Signals, is a much larger ambush in 1937 that claimed the lives of two Royal Signals soldiers and over 70 others killed and wounded.

Mirza Ali Khan, The Faqir of Ipi

In 1936 anti-colonial rebellion in the North-West Frontier was fuelled largely by the rhetoric of a Tori Khel Wazir, Mirza Ali Khan, known as the Faqir of Ipi. Initial operations in 1936 were successful in deterring rebellion but in response to increasing unrest, operations in the Khaisora valley against the Tori Khel at the end of the year—aimed at restoring peace and demonstrating the government’s determination to maintain peace—were strongly opposed. Withdrawal of the two columns greatly increased the Faqir’s influence.

In early 1937 raids were becoming larger and more numerous, and on 6 and 7 February two British officers were ambushed and murdered.[3] As the situation deteriorated, reinforcements were brought into the region until, by September, Wazirforce comprised two divisions—Waziristan Division and 1st Indian Division. The force totalled seven brigades—the three Waziristan brigades reinforced by 1st (Abbottabad), 2nd (Rawalpindi), 3rd (Jhelum), and 9th (Jhansi) Infantry Brigades, and a commensurate number of artillery, sapper, and logistic units. At its height there were over 60,000 British, Indian and irregular troops in the region.

The scale and complexity of the communications required to support the force and its mobile operations resulted in major deployment. ‘A’ Corps Signals, Waziristan District Signals, and 1st Indian Divisional Signals were supported by detachments from ‘B’ Corps Signals, 3rd Indian Divisional Signals, 2nd Indian Cavalry Brigade Signal Troop, and Kohat District Signals.[4] In general, cable was used in the rear areas and along lines of communication (although these areas were not immune to the destruction and theft of the cable runs), wireless was most important in the forward areas (considerable expertise was developed in dealing with the climatic and geographical challenges of the region), and dispatch riders proved invaluable. The Waziristan operations of late 1936 and to the end of 1938 earned Royal Signals a considerable number of awards, including three Military Medals. One of these was to Signalman Marcel Hooper, who was later commissioned and earned an MBE in India as the Assistant Commandant of the Special Armed Constabulary in Central Province and Berar; his medals are shown in the gallery below.

Throughout the operations of 1937 the rebellious tribes mounted large and successful attacks on road protection troops and convoys. On the early morning of 9 April 1937, a convoy set out from Manzai fort destined for the garrison at Wana carrying supplies and some officers and men returning to their units at Wana. The convoy was a large one, comprising forty-nine lorries (mostly from No. 30 (Independent) Mechanical Transport Section, Royal Indian Army Service Corps, based at Manzai), an ambulance, and three private cars, all escorted by four armoured cars (8th Light Tank Company, Royal Tank Corps), with a company of infantry in lorries (from 4th Battalion (Bhopal), 16th Punjab Regiment) and a lorried detachment from Waziristan District Signals. One of the armoured cars was at the front, another at the rear, and two more were amongst the transport. Similarly, the infantry in their lorries were distributed along the length of the convoy. Amongst the convoy were officers and men from various units returning to Wana after a period of leave, including a party from No. 2 Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners.

Throughout the operations of 1937 the rebellious tribes mounted large and successful attacks on road protection troops and convoys. On the early morning of 9 April 1937, a convoy set out from Manzai fort destined for the garrison at Wana carrying supplies and some officers and men returning to their units at Wana. The convoy was a large one, comprising forty-nine lorries (mostly from No. 30 (Independent) Mechanical Transport Section, Royal Indian Army Service Corps, based at Manzai), an ambulance, and three private cars, all escorted by four armoured cars (8th Light Tank Company, Royal Tank Corps), with a company of infantry in lorries (from 4th Battalion (Bhopal), 16th Punjab Regiment) and a lorried detachment from Waziristan District Signals. One of the armoured cars was at the front, another at the rear, and two more were amongst the transport. Similarly, the infantry in their lorries were distributed along the length of the convoy. Amongst the convoy were officers and men from various units returning to Wana after a period of leave, including a party from No. 2 Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners.

The long snake of lorries wove its way uneventfully past Jandola and then westward onto the Jandola-Wana road. At about 7.40 am it was ambushed at the western end of the Shahur Tangi, a narrow, steep-sided, three-mile long gorge, eight miles west of Jandola. There, having been slowed by camels let loose on the road, the convoy was attacked by a large party of Mahsuds and Bhitannis, who had occupied positions on the precipitous hillsides.

Exit of the Shahur Tangi

The leading armoured car and first three trucks, having passed out of the gorge, were not attacked directly and sped to the next manned outpost, carrying news of the attack; the armoured car subsequently returned to the fight. Meanwhile, the lorries at the front of the convoy in the gorge were disabled when their drivers were killed, trapping the others behind. Raiders hidden in the rocks close to the road attacked the convoy along its length causing very heavy casualties but, although some trucks were looted, the armoured cars, the infantry escort from 4/16th Punjab Regiment and the other troops with the convoy fought most gallantly and prevented the convoy from being overrun. An aircraft providing support overhead was badly damaged and forced to land. Reinforcements from 4/16th Punjab Regiment and the South Waziristan Scouts arrived later in the day and fighting continued sporadically until nightfall. In the evening as the firing lessened the lorries that could be moved were either sent on to Sarwakai or back to Chagmalai at the entrance to the Shaur Tangi and the wounded were evacuated—the withdrawal of the South Waziristan Scouts to Chagmalai was particularly heavily contested by the raiders. By the following morning the attackers had gone and by the afternoon on 10 April all of the vehicles that had not been destroyed had been recovered and either sent on to Wana or back to Manzai.

The detachment from Waziristan District Signals was commanded by Corporal Edward Turner. The lorry was driven by an Indian soldier and carryied four Royal Signals soldiers and another Indian signalman. In the morning’s battle, Turner and Signalman Norman Davies were killed, the Indian driver (Signalman Joseph) and Signalman Thomas Bowkett were wounded, the latter severely, but three other men, Signalmen Bartlett and McKenna and an Indian soldier, escaped unscathed.[5]

In total, the attack claimed six British officers and two other ranks (Turner and Davies) killed, five British officers and one other rank (Bowkett) wounded, one Indian medical officer and 20 Indian other ranks killed, and 39 Indian all ranks wounded.[6] The bodies of the British casualties were recovered and buried at Manzai Fort cemetery. In accordance with tradition, the Indian casualties were cremated.

The graves of Corporal E. C. Turner and Signalman N. Davies

[image error]Awards for Gallantry

The gallantry of the British officers and soldiers who defended the convoy, and some of those who came to its rescue, was rewarded by one Distinguished Service Order, three Military Crosses, one Distinguished Conduct Medal and one Military Medal. Indian Viceroy commissioned officers, NCOs, and other ranks were rewarded with the two awards of the Indian Order of Merit, 2nd Class and seven Indian Distinguished Service Medals. For a list of these awards see here.

1. (Back) 1856992 Lance Corporal (Acting Lance Sergeant) Percy Everitt Cook, ‘C’ Divisional Signals, serving with Signals Tochi and Khaisora Area. He was buried in Razmak cemetery and a memorial may be seen on his mother’s grave at Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough. The wounded Royal Signals soldier was 2307047 (formerly 625793) Signalman (later Corporal) Cecil Punter, ‘G’ Divisional Signals.

2. (Back) The painting hangs in the Headquarters Officers’ Mess at Blandford.

3. (Back) Captain John Anthony Keogh, 1st Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment, attached to the South Waziristan Scouts; and Lieutenant Ronald Nicholson Beatty, 10th Duke of Cambridge’s Own Lancers (Hodson’s Horse), attached to the Tochi Scouts and serving as the Officiating Assistant Political Agent for North Waziristan. Keogh’s orderly was also killed, as were two Indian levies travelling with Beatty.

4. (Back) Royal Signals and the Indian Signal Corps were inextricably linked from the formation of Royal Signals in 1920. From Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals for Gallantry & Distinguished Service 1920-2020:

‘Officer posts were filled by Royal Signals and, commonly, by seconded officers from other regiments. As time went by, the latter either transferred to Royal Signals or returned to their parent regiment, in much the same way for officers seconded to Royal Signals in the same period. British other ranks (no more than one-third of the unit establishments) came from Royal Signals or were attached regimental signallers; all were held on the Indian Unattached List. Until 1927, when Royal Signals assumed responsibility for the provision of all British other ranks, some attached signallers transferred to Royal Signals, some remained ‘attached’, and others returned to their parent regiment. In that year all attached other ranks were transferred to the Royal Signals Special Roster (India). During the Second World War the Indian Signal Corps was greatly expanded and units served in the Middle East, East Africa, Italy, Iraq, Iran, Burma, Malaya, Singapore and on the North-West Frontier. The partition of India in 1947 did not immediately result in all Royal Signals officers and soldiers being withdrawn and some served in positions in the Indian and Pakistan armies until the mid-1950s. In consequence, because of the inseparable link with Royal Signals all awards to personnel in units of the Indian Signal Corps are included in one form or another, either in the Register of Awards (i.e. Royal Signals all ranks or those personnel who transferred to Royal Signals) or in the various appendices in the case of all ranks of the Indian Signal Corps. In short, recounting the history of Royal Signals without including the part played by the Indian Signal Corps is telling only a portion of the story. These arguments apply equally to Burma Army Signals.’

5. (Back) 2316052 Corporal Edward Cooper Turner and 2324234 Signalman Norman Davies. The latter is recorded on the Royal Signals Roll of Honour as ‘Signalman C Davis’.

2324319 Signalman Thomas Bowkett recovered from his wounds in England before returning to India to join ‘A’ Corps Signals. During the Second World War he served as the section sergeant of ‘M’ Section, 6th Airborne Divisional Signals; he was wounded in action by mortar fire in the breakout from Normandy on 25 June 1944. On 25 March 1945 Sergeant Thomas Bowkett died of wounds received the previous day during Operation Varsity, the crossing of the River Rhine. Originally buried in a cemetery at Gildern-Kappellen, his remains were reinterred in Reichswald Forest War Cemetery on 19 November 1946.

The wounded Indian Signal Corps driver was 8880 Signalman Joseph.

6. (Back) In addition to the Royal Signals personnel, those known to be casualties were:

Killed in action or died of wounds:

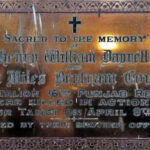

Major Henry William Dayrell Palmer, 3rd Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment.

Captain Myles Bertram Courtney, 3rd Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment.

Captain Nisar Muhamad Durrani, Indian Medical Services, Combined Indian Military Hospital, Wana.

Lieutenant Michael Earle, Royal Regiment of Artillery, 2nd (Derajat) Mountain Battery (Frontier Force).

Lieutenant Eric Charles Langford Hinde, Corps of Royal Engineers, 19th Field Company, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners.

Lieutenant Edwin Stuart Rainier France, 3rd Battalion (Duke of Connaught’s Own), 7th Rajput Regiment.

Second Lieutenant George Laurence Scott, 3rd Royal Battalion (Sikhs), 12th Frontier Force Regiment.

Twenty Indian other ranks were killed in action or died of wounds.

Wounded:

Major Alexander Paton MC, Royal Regiment of Artillery, 2nd (Derajat) Mountain Battery (Frontier Force).

Major Thomas Zachariah Waters MC, Royal Indian Army Service Corps.

Captain Stanley Davison Wilcock, 1st Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment, attached to the South Waziristan Scouts.

Lieutenant Frank Douglas Robertson, 1st Kumaon Rifles, 19th Hyderabad Regiment, attached to the South Waziristan Scouts.

Second Lieutenant Lionel Henry Mosse Parsons, Probyn’s Horse (5th King Edward VII’s Own Lancers). (See the citation for the Distinguished Conduct Medal to Lance Corporal A. Williams, 8th Light Tank Company.)

Subadar Abdul Rahman, 3rd Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment.

Subadar Dalip Singh, No. 30 (Independent) Mechanical Transport Section, Royal Indian Army Service Corps.

Thirty-seven Indian other ranks were wounded.

Manzai Fort Cemetery, Pakistan

This blog post originally appeared in 2020 on my website dealing with Royal Signals honours and awards. With the closure of that site I have updated it and moved it here.

I must firstly record my most sincere thanks to Muhammad Naeem, a civil engineer from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, for his enthusiastic help in providing the photographs used here. For more information on the men buried at Manzai Fort cemetery, please read the notes linked to each of the photographs in the galleries.

One of the interests that I have developed while working on the Royal Signals honours and awards project relates to the fate of the Corps’ casualties, particularly those who lie in graves not maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. One of my keenest interests is in the casualties of the inter-war years, particularly those men who died in the North-West Frontier Province.[1]

Most of the military cemeteries and many of the civilian graveyards in which they lie are no longer in use and are not maintained. Although many have become derelict they remain a feature of the locale and some are protected by virtue of the fact that they sit within or near military or Frontier Constabulary bases.

In the account of the Shahur Tangi Ambush, which occurred a little over 85 years ago on 9 April 1937, I showed photographs of the graves of Corporal E. C. Turner and Signalman N. Davies who were killed in action. They were buried in the cemetery at Manzai Fort.

The graves of Corporal E. C. Turner and Signalman N. Davies

A British military outpost was first established at Manzai in 1919 during the Third Anglo-Afghan War and over the next two decades it grew into an important base in the region, served by a narrow-gauge railway and a small airstrip. Located at 1,600 feet on a 13-miles long ridge in the land of the Mahsud, Manzai Fort is a little over 60 miles from the ancient city of Dera Ismail Khan to the east, the headquarters of Waziristan District Signals through much of the 1920s and 1930s. Twenty-five miles by road to the east is Tank, the district capital and an important British base for operations into southern Waziristan. Twelve miles to the north-west is Jandola, another important post throughout the various Waziristan campaigns, which lies at the junction of the Shahur and Tank Zam rivers and the start of the two main routes into Mahsud tribal territory. Running along the ridge on which the fort sits is the Tank-Jandola road. Testament to the site’s importance it remains in use by the Frontier Constabulary. For much of its existence the fort had a small hospital, which accounts for the number of men who died here of illness and disease.

The cemetery is located on the east of the Tank-Jandola road, half a mile north of the fort.[2] Built on a shallow slope, the cemetery is surrounded by a stone wall with decorative corner posts. Some of the graves are covered with stone plinths and each grave has a cement-covered, stone marker inscribed with the details of the casualty. These cement-covered markers appear to be as a result of a refurbishment of the cemetery in the late-1930s, and this may explain some of the errors on them. The harsh weather in the region accounts for most of the damage but some stone blocks making up the plinths have been removed.

[image error]Fort Manzai Cemetery – view from the north-west corner

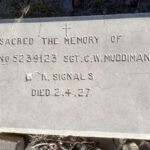

Royal Signals Burials at Manzai Fort

(Additional details may be found linked to the photographs in the gallery.)

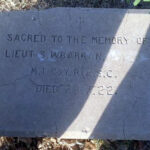

-2309555 Lance Corporal Alfred John Cowderoy, ‘B’ Divisional Signals, died of disease or illness at Mazai Fort on 28 March 1923, aged 21.

-2324234 Signalman Norman Davies, Waziristan District Signals, killed in action on 9 April 1937 at Shahur Tangi, aged 22.[3]

-5239123 Sergeant Caleb William Muddiman, W/T Section, Manzai Detachment, Waziristan District Signals, died suddenly of disease or illness at Manzai on 2 April 1927, aged 36.

-2316052 Corporal Edward Cooper Turner, Waziristan District Signals, killed in action on 9 April 1937 at Shahur Tangi, aged 31.

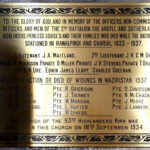

Killed in Action on 9 April 1937 at Shahur Tangi & Buried at Manzai Fort

(Additional details may be found linked to the photographs in the gallery.)

-Major Henry William Dayrell Palmer, 3rd Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment.

-Captain Myles Bertram Courtney, 3rd Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment.

-Lieutenant Michael Earle, Royal Regiment of Artillery, 2nd (Derajat) Mountain Battery (Frontier Force).

-Lieutenant Edwin Stuart Rainier France, 3rd Battalion (Duke of Connaught’s Own), 7th Rajput Regiment.

-Lieutenant Eric Charles Langford Hinde, Corps of Royal Engineers, 19th Field Company, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners.

-Second Lieutenant George Laurence Scott, 3rd Royal Battalion (Sikhs), 12th Frontier Force Regiment.

Other Burials at Manzai Fort

(This list should not be considered complete. Additional details may be found linked to the photographs in the gallery.)

-Captain Frederick Herbert Fardell MC, Royal Regiment of Artillery, 8th Lahore Mountain Battery, died of disease or illness on 21 September 1927.

-Flying Officer Kenneth Northcote Lees, No. 5 (Army Cooperation) Squadron, Royal Air Force, was killed in an air crash on 11 March 1937.

-Lieutenant Arthur Sidney Noel Barron, No. 14 Indian Motor Transport Company, Indian Army Service Corps, died of disease on 29 July 1922.

-1040 Company Quartermaster Sergeant C. W. Rowley, No. 8 Indian Motor Transport Company, Indian Army Service Corps died on 13 July 1922.

-787349 Staff Sergeant John Davies, Indian Army Service Corps, died on 22 July 1934.

-5878587 Staff Sergeant R. Weaver, The Northamptonshire Regiment attached to the Indian Army Service Corps, died on 16 December 1923.

-M/14716 Sergeant Alfred William Beer, No. 18 Indian Motor Transport Company, Indian Army Service Corps, died on 15 May 1926.

-M/14476 Sergeant Albert Edward Beavan, No. 24 Indian Motor Transport Company, Indian Army Service Corps, took his own life on 8 November 1923.

-1852132 Lance Sergeant Allan Urquhart Liddell, Corps of Royal Engineers, died on 15 July 1926.

-7870494 Private Douglas Alexander Hay, 9th Armoured Car Company, Royal Tank Corps, took his own life by way of a self-inflicted gunshot from a revolver on 25 April 1923.

-Private-Follower Joseph, 1st Madras Pioneers, died 2 December 1921.

Private D. Davidson, 2nd Battalion, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Princess Louise’s), was killed in action on 27 May 1937.

-2979103 Private Neil McCracken, 2nd Battalion, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Princess Louise’s), was killed in action on 27 May 1937.

-5242658 Private Ernest W. Mealin, The Worcestershire Regiment attached to Headquarters 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, died of disease or illness at Manzai on 21 June 1922.

-2979738 Private J. Moore, 2nd Battalion, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Princess Louise’s), was killed in action on 27 May 1937.

Manzai Fort Cemetery

Royal Signals Graves at Manzai Fort

9 April 1937 Shahur Tangi Casualties Buried at Manzai Fort

may be found here.

may be found here.Photo: Muhammad Imran Saeed.

" data-image-caption="Memorial to Major H. W. D. Palmer and Captain M. B. Courtney at the Holy Trinity Cathedral Church, Sialkot

" data-medium-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." />

Other Burials at Manzai Fort

[image error]

[image error]

1. (Back) Now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, which since 2018 has included the Federally Administered Tribal Areas.

2. (Back) Manzai Fort coordinates: 32.249555, 70.246004. Cemetery coordinates 32.261531, 70.243371.

3. (Back) Incorrectly recorded on the Royal Signals Roll of Honour as ‘Signalman C. Davis’.

July 20, 2022

Lieutenant Luigi Parisotti, 4/39th Garhwal Rifles

As a researcher of military history, one of my greatest sources of satisfaction is the acceptance by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission of a correction to a record of commemoration. Mostly as a consequence of the digitisation process, such errors are legion. Additionally some casualties were missed for various reasons. My first success was the inclusion of one of Blacker’s Boys, the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, on the Addenda Panel at Thiepval; he was killed on 1 July 1916 but his death had not been recorded. For some years I have been examining the CWGC commemorations from the First World War in the United States and recently I have been working on a project to ensure the correct commemoration for all Royal Signals casualties. My latest success, however, was for an infantry officer killed in action in Waziristan in a fight that earned another officer a posthumous Victoria Cross, whose date of death and regiment were recorded incorrectly.

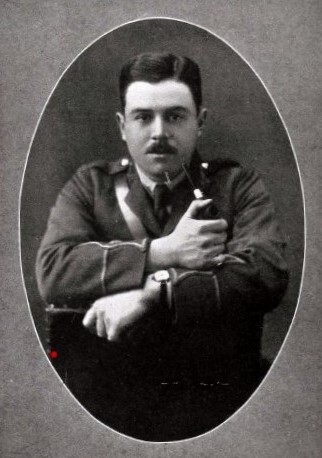

Lieutenant Luigi Maria Parisotti was born on 25 July 1891 in Paddington, London, the son of an Italian father and an English mother; he was the fourth of five children.[1] He was educated at Stonyhurst College; Collège Saint Pierre, Calais; and the Sorbonne.[2] At some time he began to use the name ‘Louis’.

Luigi Parisotti

Parisotti was commissioned into Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own (Yorkshire Regiment) on 2 September 1915. After a period with the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion at West Hartlepool, he joined the 2nd Battalion of the Green Howards near Carnoy in France as a platoon commander in ‘D’ Company in February 1916. The battalion was part of 21st Brigade in 30th Division, which had transferred from 7th Division the previous December and on doing so lost two of its regular battalions to other brigades in 30th Division, receiving two ‘Pals’ battalion in their place—18th (Service) Battalion, King’s (Liverpool Regiment) (2nd City) and 19th (Service) Battalion, Manchester Regiment (4th City).

The attack by 21st Brigade on 1 July 1916 at Montauban was conducted by 18th Liverpool Pals on the left with 19th Manchester Pals on the right. 2nd Green Howards was in support with 2nd Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment in reserve.[3] Two platoons from 2nd Green Howards were detached to the two attacking battalions as clearing platoons—Parisotti’s platoon being attached to the Liverpool Pals and that of Second Lieutenant Arthur Dickinson to the Manchester Pals. As the attack progressed, 18th Liverpool Pals suffered grievously from a machine-gun firing into its left flank, which also inflicted severe casualties on Parisotti’s platoon and those advancing on the left flank of 2nd Green Howards. Parisotti was one of those wounded in this endeavour; the battalion’s war diary gave an account of the action:

‘Of the 2 ‘clearing’ platoons, one, 2Lt PARISOTTI’S had been practically exterminated in the crossing. One or two men under Cpl PEAT who succeeded in reaching the German trench did very good work and held up a party of Germans who were bombing their way up from VALLEY TRENCH until the other platoon under 2Lt DICKINSON came to their assistance. 2Lt DICKINSON with commendable promptitude and decision, on seeing the state of affairs, at once got his men on to the top and overwhelmed a considerably superior number of Germans who threw up their hands.’ [4]

For their gallantry that day, Second Lieutenant Dickinson was awarded the Military Cross and Corporal Peat was awarded the Military Medal.[5]

18th Liverpool Pals lost almost 500 all ranks killed and wounded and 2nd Green Howards sustained about half that number of casualties. Parisotti was evacuated to the United Kingdom for medical treatment and did not return to the battalion. After he recovered from his injuries he applied for the Indian Army, into which he was admitted as a lieutenant on probation on 28 November 1917. He joined 2/3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles on 9 December 1917 and at some time thereafter was attached to 3/7th Gurkha Rifles, with which he took part in the Third Anglo-Afghan War.

4th Battalion, 39th Garhwal Rifles was raised at Dehra Dun in the Garhwali District of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh[6] on 28 October 1918. ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies were transferred from the 3rd Battalion and ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies joined from 3/11th Gurkha Rifles in November.[7] One of the officers to join at this time was Second Lieutenant W. D. Kenny, newly commissioned into 3/11th Gurkha Rifles.

Parisotti joined the battalion on 3 November 1919 as officer commanding ‘C’ Company. In May the battalion had been engaged in fighting Afghan forces at Thal and after the armistice had been stationed at the Peiwar Pass on the Afghan border. Ordered to join Waziristan Force, the battalion marched to Kohat and then Bannu before joining the Tochi Column near Miranshah. Waziristan Force had been mobilised to subdue the Tochi Wazirs and the Mahsud tribes that had become even more hostile to British presence after the conclusion of the Third Anglo-Afghan War, conducting numerous raids against British posts; in the period between the armistice and the beginning of the operations on 3 November, Waziristan Force had lost 139 all ranks killed and 159 wounded. The background to the campaign and its conduct may be read in the despatch by Commander-in-Chief in India[8] and in the history of the campaign produced by the Army General Staff.[9]

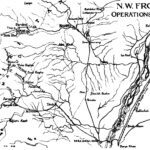

North-West Frontier Operations, 1919-1921

The operation by Waziristan Force was a considerable undertaking. The force numbered a little under 30,000 troops with about 33,000 non-combatants in support. The first part of the operation would be against the Tochi Wazirs, mounted by the Tochi Column (two brigades, 43rd and 67th) advancing from Miranshah north-east to Datta Khel. This operation was largely uneventful and by the end of the month the troops were back at Miranshah. The subsequent operation against the Mahsud (Maseed) was another matter. The target of the operation was ultimately the Mahsud town of Kaniguram. At that time no road existed to the south-east between Miranshah and Kaniguram and the direct route there over the snow-covered Razmak Narai negated that route. Instead the formation, now renamed the Derajat Column, would march via Bannu and Pezu to a concentration area at Jandola. That manoeuvre was complete by mid-December and preparations were made for the advance north-west up the Takki Zam river. The fighting throughout the early advance immediately north of Jandola was tough and by 21 December five battalions had been heavily engaged and were in need of relief. In consequence, two battalions were withdrawn from the column for duties on the line of communication and were replaced by 4/39th Garhwal Rifles, 2/76th Punjabis and 2/152nd Punjabis. By the end of the year the entrance to the route north along the Takki Zam (the Spinkai Ghash[10]) had been secured and on 29 December the column headquarters and 43rd Brigade moved four miles farther up the river to Kotkai.

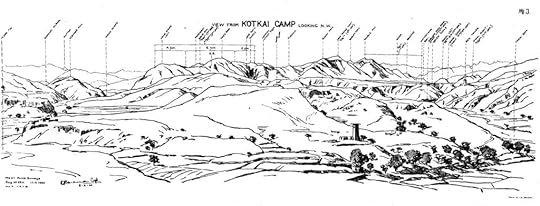

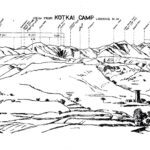

View from Kotkai Camp looking north

Over the next several days piquets were established on the high ground north of Kotkai. This operation was largely unopposed but on 2 January, during work to establish a piquet on ‘Scrub Hill’, an attack was mounted against the covering force, 4/39th Garhwal Rifles, on Spin Ghara ridge farther to the north.[11]

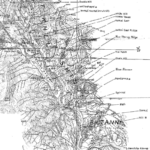

Spin Ghara – Dispositions of 4/39th Garhwal Rifles on 2 January 1920

The action is described in the regimental history, and should be reproduced in full:

‘ At 10.40 hours objectives were taken without opposition, except for long-range sniping from across the Inzar Tangi. ‘C’ Company, however, in its position on the exposed flank, was heavily sniped from inaccessible hills about 350 to 600 yards away, but effectually counter-sniped the enemy. At about 11.50 hours the enemy, moving up the nallahs to the west, developed an attack 100 strong, under cover of a heavy fire from the north-east, against this company. As the casualties were now considerable, ‘C’ Company was reinforced by ‘D’ Company. At 13.00 hours parties of the enemy were seen in the distant river bed of the Tank Zam moving south. Casualties from sniping further increased, and Lieutenant L. Parisotti, ‘D’ Company Commander, was killed at this time. At about 14.15 hours the second enemy attack developed; rushes were made by the enemy, and fighting at close quarters ensued. The attack was driven off by bombs and Lewis gun fire. Lieutenant W. D. Kenny, ‘C’ Company Commander, used bombs and a rifle himself with great effect. Where there was open ground and a field of fire the enemy broke and fled in disorder, but from now onwards they remained in the dead ground within bombing distance. A charge by the company was impossible down the steep rocky hillsides, and was subject to heavy enfilade fire. Casualties were coming back steadily, and evacuation became exceedingly difficult owing to the number of carriers required and the particularly steep ground. During the second attack ‘B’ Company caught a party of the enemy 80 strong in a nallah, and inflicted heavy casualties with a Lewis gun.

In spite of hand grenades and artillery and aeroplane support, the enemy at 14.50 hours developed the heaviest attack of the day against the right flank, and hand-to-hand fighting ensued. The enemy in the rear shouted and charged. Lieutenant Kenny himself freely used the bayonet and organized counter-cheers of “Garhwal”, and this attack was also driven back to the dead ground close below the position. The time of withdrawal was 15.00 hours, but the last attack and evacuation of wounded necessitated postponement till 15.15 hours, at which time ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies commenced to retire, covered by ‘B’ Company, who punished the enemy attempting to follow up over the crest. At this moment Subadar Jhagar Sing Bisht, ‘C’ Company, seeing a Lewis gun in danger of capture, though wounded in the left hand, came to grips with the leading Mahsud and knocked him down with a stone, saving the gun. For his conspicuous gallantry on this occasion Subadar Jhagar Sing Bisht gained the immediate award of the 2nd Class Indian Order of Merit.

Lieutenant Kenny had now retired the greater part of ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies, but, seeing further casualties, he returned with a handful of men left with him and charged the enemy, enabling the casualties to be removed.

He fought, using his kukri and revolver, till he and his men were killed. This gallant act of self-sacrifice also assisted the withdrawal from the whole position. The posthumous award of the Victoria Cross was subsequently made for Lieutenant Kenny’s most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty on this occasion. In the award to their leader rests the recognition of the gallant ‘handful’ who went back and died with him.

The command of ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies now devolved on Subadar Indar Sing Bisht, who continued to direct their retirement with great skill and gallantry, and drove back two enemy attacks, thus gaining the immediate award of the 2nd Class Indian Order of Merit. The withdrawal was carried out by all in an orderly manner, covered by two companies 57th Rifles. But the Mahsuds, who temporarily and quickly showed themselves along the ridge in large numbers, contrary to their custom declined to follow up the withdrawal.’[12]

The bodies of both officers were brought back from the ridge and were buried in Jandola Cemetery.[13] The remains of the 28 Garhwali troops killed in action were cremated. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has not been able to maintain Jandola Cemetery and all of the casualties buried there who died between 4 August 1914 and 31 August 1921 are commemorated on the India Gate in New Delhi, as are all of the Indian troops who died during the campaign. In addition to those killed, the action cost the battalion 29 wounded. A list of the British and Garhwali casualties from 4/39th Garhwal Rifles for the campaign in Waziristan between November 1919 and May 1920 may be found here.

The bodies of both officers were brought back from the ridge and were buried in Jandola Cemetery.[13] The remains of the 28 Garhwali troops killed in action were cremated. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has not been able to maintain Jandola Cemetery and all of the casualties buried there who died between 4 August 1914 and 31 August 1921 are commemorated on the India Gate in New Delhi, as are all of the Indian troops who died during the campaign. In addition to those killed, the action cost the battalion 29 wounded. A list of the British and Garhwali casualties from 4/39th Garhwal Rifles for the campaign in Waziristan between November 1919 and May 1920 may be found here.

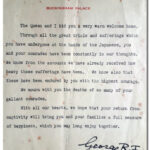

Kenny’s Victoria Cross was announced in the London Gazette the following September.[14] It was presented to his father by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 3 November. As the extract from the regimental history records, two Viceroy commissioned officers were awarded the Order of Merit. In addition, an NCO and a sepoy received the Indian Distinguished Service Medal. All four were amongst those mentioned in despatches. For a list of awards to 4/39th Garhwal Rifles see here.

Kenny’s Victoria Cross was announced in the London Gazette the following September.[14] It was presented to his father by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 3 November. As the extract from the regimental history records, two Viceroy commissioned officers were awarded the Order of Merit. In addition, an NCO and a sepoy received the Indian Distinguished Service Medal. All four were amongst those mentioned in despatches. For a list of awards to 4/39th Garhwal Rifles see here.

Luigi Parisotti was not the only member of his family to serve nor the only tragedy. His younger brother Joseph served with 1st Battalion, Irish Guards; he died of wounds on 2 April 1918, aged 18, in No. 22 General Hospital at Camiers; his wounds possibly sustained near Boisleux-Saint-Marc south of Arras during the early part of the German offensive at the end of March.[15] He is buried in Etaples Military Cemetery.

His older brother Albert was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest in July 1912. He was commissioned into the Royal Army Chaplains Department in September 1915 and served with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force during the Gallipoli Campaign aboard the hospital ship Kildonan Castle. For his services in the Palestine Campaign he was appointed an OBE in 1919 and mentioned in despatches.[16] He continued to serve with the Royal Army Chaplains Department (reverting in grade after the war) and was appointed Chaplain to the Forces 3rd Class in 1931, 2nd Class in 1935, and 1st Class in 1938. He served throughout the Second World War (as Chaplain to the Forces 1st Class, ranking as Colonel) and retired on 8 May 1945. The Reverend Albert Parisotti OBE died in Leicestershire in 1970, aged 84.

Sources:

Photo of Luigi Parisotti : Ryan Johnson.

Map of North-West Frontier Operations: Evatt, J. (1922). Historical Record of the 39th Royal Garhwal Rifles. Vol. 1 1887-1922. Aldershot: Gale and Polden.

Map Jandola to Kotkai: History of the campaign: General Staff, Army Headquarters India. (1921). Operations in Waziristan, 1919-1920. Calcutta: Government Printing.

View from Kotkai Camp: History of the campaign, op cit.

Satellite Image of Kotkai: Google.

1. (Back) Luigi Parisotti (21 June 1853-6 April 1923) married Sarah Augusta Geary (9 April 1955-1929) in London in 1884. Although from an English family, Sarah had been born in New York. Luigi senior was a music (singing) teacher who began his career in Rome; he also gave well-received vocal performances. He emigrated to the United States in December 1915 and his wife followed in 1918. The couple lived in an apartment on Claremont Avenue in New York, where Luigi died of pneumonia in 1923. (Obituary: The Musical Leader, 12 April 1923. Vol. 45, No. 15, p. 344.) His wife died in England in 1929.

2. (Back) For information about Stonyhurst during the war see the school magazine archive.

3. (Back) For an excellent description of the battle with maps and illustrations see Zero Hour Z Day.

4. (Back) The National Archives (TNA). 2 Battalion Yorkshire Regiment. WO/95/2329/2.

5. (Back) Military Cross. Second Lieutenant Arthur Dickinson, 2nd Battalion, Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own (Yorkshire Regiment). For conspicuous gallantry during operations. He met a superior number of the enemy firing at our advancing troops and bombing up the captured trench. He at once got his platoon on the top of the parapet and killed or captured the whole enemy party. LG 25 August 1916; 29724, p. 8459. Company Quartermaster Sergeant Arthur Dickinson had been commissioned from a service battalion on 23 April 1916 and joined the 2nd Battalion at the end of that month. His award was notified on 26 July 1916. In January 1917 he joined ‘C’ Company as a platoon commander before leaving the battalion to become an instructor at 30th Division’s depot. He rejoined the battalion in the spring before being sent to England as a bombing instructor. After a return to ‘C’ Company in the autumn, at the end of 1917 he left to join the Machine Gun Corps Training Centre at Grantham. He subsequently transferred to the Machine Gun Corps.

Military Medal. 7838 Corporal Duncan Peat, 2nd Battalion, Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own (Yorkshire Regiment). LG 16 November 1916; 29827, p. 11142.

6. (Back) Now Dehradun, Uttarakhand.

7. (Back) These were two companies from 39th Garhwal Rifles that had been transferred to form ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies of 3/11th Gurkha Rifles when it had been raised in Iraq in May 1918. The battalion had arrived back in India in June 1918.

8. (Back) Despatch by Commander-in-Chief in India: LG 8 December 1920; 32156.

9. (Back) History of the campaign: General Staff, Army Headquarters India. (1921). Operations in Waziristan, 1919-1920. Calcutta: Government Printing. (Accessed here.)

10. (Back) The pass is just to the west of the site of Spinkai Cadet College, Jandola, the location then of the brigade’s encampment for these operations.

11. (Back) The attack on 4/39th Garhwal Rifles was against the northern flank of the battalion in the area between coordinates 32.440792, 70.021546 and 32.444229, 70.023724. Scrub Hill piquet was at approximately 32.427390, 70.029450.

11. (Back) 109th Infantry, 4/39th Garhwal Rifles, 2/150th Infantry and 2/152nd Punjabis.

12. (Back) Evatt, J. (1922). Historical Record of the 39th Royal Garhwal Rifles. Vol. 1 1887-1922. Aldershot: Gale and Polden. pp. 111-113.

13. (Back) Unmaintained in the intervening years, Jandola Cemetery is now derelict. As far as can be ascertained, the cemetery is to the rear and a short distance north-east of Jandola Fort near coordinates 32.336151, 70.121402.

14. (Back) LG 8 December 1920; 32156. His Victoria Cross is displayed at the Lord Ashcroft Gallery at the Imperial War Museum, London.

15. (Back) 12322 Private Joseph Bernard Bruno Parisotti, 1st Battalion, Irish Guards.

16. (Back) OBE (Military). Chaplain to the Forces 3rd Class Reverend Albert Parisotti. Deputy Assistant Principal Chaplain. Palestine Campaign. LG 3 June 1919; 31371, p. 6924.

Despatches. Chaplain to the Forces 3rd Class Reverend Albert Parisotti. Deputy Assistant Principal Chaplain. Palestine Campaign. LG 5 June 1919; 31383, p. 7174.

The post Lieutenant Luigi Parisotti, 4/39th Garhwal Rifles first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.

July 14, 2022

Non-Commissioned Officers and the Military Cross

This blog post originally appeared in 2016 on my website dealing with Royal Signals honours and awards. With the closure of that site I have updated it and moved it here.

The medals of Lance Sergeant D. E. Ward MC

After the 1993 review of decorations and medals for gallantry, the Military Cross replaced the Military Medal as the third level award for non-commissioned officers and other ranks. Prior to 1993 there were 98 Military Crosses, including two bars, awarded to officers of the Corps, one award to a warrant officer during the Second World War and one to a warrant officer during the Borneo Confrontation. In addition, there were several awards to officers of the Indian Signal Corps serving alongside their Royal Signals counterparts in actions in North Africa, the Italian Campaign and Burma. Since 1993 there has been only one Military Cross awarded to a Royal Signals non-commissioned officer—to Sergeant N. J. Hillyard in 2016.[1] He is not, however, the first NCO of the Corps to wear the ribbon of the Military Cross.

In India on the evening of Saturday 1 February 1936, two NCOs of Kohat District Signals were returning to camp in a motor-cycle and sidecar along a mist-covered road east of the town when they hit a bullock cart—one was killed and the other badly injured.[2] The dead man was Lance Sergeant D. E. Ward MC, an attached NCO from ‘A’ Corps Signals.[3]

Kohat District Signals (Lance Sergeant D. E. Ward MC is on the left)

17714 Private Dennis Ward, 20th Hussars, 1915

Dennis Ward was born in Derby on 15 March 1895, the son of a well-known pig dealer. Just after the outbreak of the First World War he enlisted and in May 1915 he arrived in Flanders to join 20th Hussars, part of 5th Cavalry Brigade in 2nd Cavalry Division.[4] He did not stay long with the regiment, being selected for a commission and dispatched for officer training in November that year. On 27 December, Ward was commissioned into The Northumberland Fusiliers. The regiment became the second largest during the First World War, and amongst the 45 battalions raised after 1914 were the eight battalions (four each) of the Tyneside Scottish and Tyneside Irish. Ward was destined to join a battalion of the former. He did not join his battalion immediately, however, remaining in England with the 29th (Reserve) Battalion (Tyneside Scottish) when the four battalions of the Tyneside Scottish that made up 102nd Brigade went to France with 34th Division in January 1916.[5]

[image error]Second Lieutenant D. E. Ward, The Northumberland Fusiliers (Tyneside Scottish)

During the attack at Marsh Valley near La Boiselle on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 20th (Service) Battalion (1st Tyneside Scottish) suffered severe casualties—all the officers were killed or wounded.[6] Ward was posted to that battalion in one of the reinforcement drafts after the battle. He served with the battalion in the latter part of 1916 and through 1917. In February 1918, the 1st and 2nd Tyneside Scottish were disbanded as part of the reorganisation of the British Expeditionary Force and the officers and men were posted to the two surviving battalions in the brigade. Ward, to his great fortune, was dispatched elsewhere. He joined VI Corps Signal School for training as a battalion signals officer. In doing so avoided becoming one of the many casualties suffered by 34th Division and the Tyneside Scottish Brigade at Croisilles south of Arras when the German offensive began on 21 March 1918. The remnant of the division moved north to recuperate. On 2 April, Ward joined 23rd (Service) Battalion (3rd Tyneside Scottish) as Signals Officer and the same day 131 reinforcements arrived; for the next few days the battalion reorganised and retrained before moving into the line near Armentieres on 5 April.

The battalion would now face the second phase of the German offensive that began with a bombardment on 7 April, lasting until the German assault two days later. For the next three days the battalion was in action as the German offensive pushed north-west towards Bailleul. On the evening of 12 April, it was ordered to move to a new position in front of the De Seule-Neuve Eglise (Nieuwkerke) road[7] and to ‘restore the front line…’.[8] By the following morning, the new position had been wired and a tentative enemy attack was driven off. In the evening the enemy attacked in strength and pushed the Tyneside Scottish back. Lieutenant Ward was sent out on a patrol along the Neuve Eglise road to find out what was happening on the left flank, which he managed to do until he was wounded. He was evacuated for medical treatment, and on 1 May embarked for hospital in England. For his gallantry in this action he was awarded the Military Cross. The award was announced in the battalion’s war diary on 17 June and published in the London Gazette in September:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. Whilst the enemy was delivering a violent attack and the situation on the left flank was obscure, this officer took out a reconnoitring patrol, and for an hour and a half, under very heavy fire, kept the enemy movements under observation, and sent back valuable messages. He continued his work until seriously wounded in the leg later in the evening.[9]

Ward relinquished his commission in February 1919. For his war service he was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal 1914-20 and Victory Medal. He rejoined the family’s hog business with his brothers but in March 1924 he enlisted into Royal Signals as a soldier (resigning his commission with effect from 18 March). After his training at Maresfield, Ward was posted to India where he served with ‘A’ Corps Signals and where he proved to be a handy sportsman, representing the unit at cricket and soccer. Promoted to corporal in April 1928 and lance sergeant in April 1932, ‘Tubby’ Ward was a popular member of the unit and his exploits regularly featured in The Wire.

Lance Sergeant Ward’s funeral at Kohat was well attended with representatives from ‘A’ Corps Signals and several other units and his grave was covered in a mass of floral tributes. Later a substantial grave marker was erected. Kohat Christian Cemetery is largely overgrown now, and it is not known if the grave marker is still in place. Soon after his death his medals were returned to the War Office; they were sent to his sister in September 1936. In addition to those described above, Ward had also been awarded the Service Medal of the Order of St. John.

The grave of Lance Sergeant Dennis Edwin Ward MC, Royal Signals

A second Royal Signals NCO also served as an officer during the First World War but with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in 8th (Anson) Battalion in 188th Brigade, 63rd (Royal Naval) Division. After only six weeks in Flanders as a platoon commander in ‘B’ Company, Sub-Lieutenant William Stevenson took part in the attack by the brigade on 26 October 1917 north-west of the Passchendaele Ridge in support of the main attack by the Canadian Corps. The fighting was harsh—the day cost the battalion two officers killed, seven wounded and one missing, and 260 other ranks killed, wounded and missing—but against the odds Sub-Lieutenant Stevenson with the remnants of his platoon captured Varlet Farm[10] (a little over a mile north-west of Tyne Cot Cemetery). The citation for his Military Cross recorded:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in leading his platoon against a farm strongly held by the enemy. In spite of a stubborn resistance, and heavy losses, he finally succeeded in capturing the farm, with seven men—all that remained of his platoon. Although nearly surrounded by the enemy, he held the position until relieved that night[11]

The Anson Battalion cap badge

Stevenson was born in Salford, Lancashire on 7 December 1893, where he qualified as an electrical engineer. When war broke out, he enlisted into The King’s (Liverpool Regiment) and joined the 13th (Service) Battalion in 25th Division but before the division had embarked for France in September 1915, he had transferred to the Divisional Cyclist Company with which he served as a lance sergeant. When the company was reorganised in May 1916, he was transferred to The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, posted to the 9th (Service) Battalion in 74th Brigade and promoted to sergeant.[12] Recommended for a commission, he left France in the summer of 1917 and attended No. 21 Officer Cadet Battalion at Fleet in Hampshire. Stevenson was commissioned as a temporary sub-lieutenant on 30 May and after a period at the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion at Blandford, in September he arrived in Flanders and joined the Anson Battalion. In March 1918 Stevenson was at home on leave when he fell ill and was admitted to hospital. Diagnosed with severe gastritis, a medical board in May judged him unfit for general service until he had been treated further. On 25 May, King George V presented him with his Military Cross at an investiture at Buckingham Palace. Stevenson did not return to the front but served at home, including a period from April 1919 with the Ministry of Labour attached to No. 3 District Officer University & Technical Courses, until he was demobilised on 29 June 1919.[13] For his war service he was awarded the British War Medal 1914-20 and Victory Medal.

After he was demobilised (and married), he enlisted as a soldier and joined Royal Signals in its earliest days.[14] Promoted to lance sergeant in September 1921 he served at Abbassia with Egypt Command Signals (where his daughter was born in August 1922 and where his infant son died in December 1923) and where he was made acting sergeant in January 1925. Posted to India in 1929, he joined 1st Indian Divisional Signals at Upper Topa, where he was promoted to company quartermaster sergeant in March 1933. Stevenson left India in early 1934 bound for the Signal Training Centre at Catterick where, sadly, his wife died in December that year.[15] Stevenson joined 3rd Divisional Signals in July 1935 and was promoted the following September, after which he served as the company sergeant major of No. 1 Company. In 1938 he was posted to 5th Divisional Signals, where he was serving on the outbreak of the Second World War. While at Bulford he remarried in November 1938; the couple had several more children. He was commissioned as a Technical Maintenance Officer on 9 September 1939 (inexplicably he transferred to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps in July 1941 and back to Royal Signals in April 1942).[16] Subsequently promoted to captain, his career ended when he was dismissed the Service by sentence of a General Court Martial on 20 October 1943. He died in early 1946.

Acknowledgement:

Mary Wortley for permission to use the photographs of her great-uncle Dennis Ward MC.

1. (Back) London Gazette 18 March 2016; 61529, p. 6082.

2. (Back) See: The Wire, April 1936, p. 152. The injured NCO was 2313843 Sergeant Ronald Arthur Douglas Sprunt (2 April 1903-March 1974).

3. (Back) 2316138 Lance Sergeant Dennis Edwin Ward MC.

4. (Back) 17714 Private.

5. (Back) For an excellent account of the four battalions in the First World War see: Stewart, G. & Sheen, J. (2014). Tyneside Scottish. Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

6. (Back) The battalion’s war diary records 10 officers killed in action, 10 wounded and seven missing, and 62 other ranks killed in action, 305 wounded and 267 missing. The final tally for the officers would be 17 killed in action and 10 wounded.

7. (Back) Today the N331.

8. (Back) The National Archives. War Office: First World War and Army of Occupation War Diaries, 23 Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers. WO 95/2463/2.

9. (Back) London Gazette 16 September 1918; 30901, p. 11030.

10. (Back) Today the farm is a popular bed and breakfast destination.

11. (Back) Announced on a Divisional Routine Order on 20 November 1917. Published: London Gazette 17 December 1917; 30431, p. 13184. Citation: London Gazette April 1918; 30645; p. 4881.

12. (Back) Stevenson served as: 19299 Lance Corporal, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment); 6047 Lance Sergeant, Army Cyclist Corps; and 25133 Sergeant, The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment.

13. (Back) The Department of Officer University & Technical Courses was responsible for the placement of disabled officers onto education and training courses.

14. (Back) 2306007 Signalman William Stevenson MC.

15. (Back) Lilian Young was born in Lancashire in 1894; the couple married there in the second quarter of 1919. She died in York on 20 December 1934.

16. (Back) 100626 Lieutenant William Stevenson MC.

June 27, 2022

Operation Plainfare – The Berlin Airlift 1948

A similar blog post originally appeared in 2020 on my website dealing with Royal Signals honours and awards. With the closure of that site I have updated it and moved it here. The events that it commemorates began 74 years ago this week. The ‘On This Day‘ series by the Royal Signals Museum also has a short piece about the Berlin Airlift.

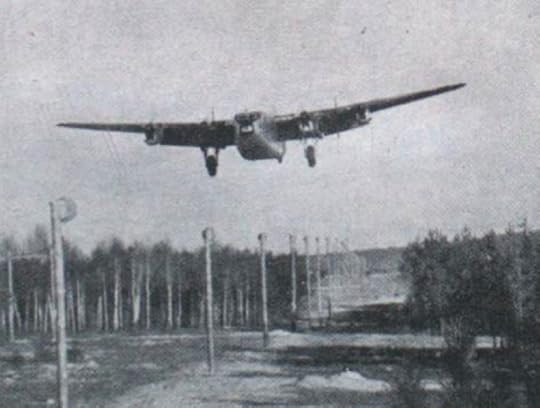

A Royal Air Force Avro York at landing at RAF Gatow

In 1948, plans to create a new West German state from the zones occupied by the Western Allies, and the introduction of a new currency—the Deutschmark—resulted in the withdrawal of the USSR from the Allied Control Council and the blockade of road, rail, and canal links into West Berlin. In response, the United States began Operation Vittles on 26 June, and the United Kingdom followed with Operation Plainfare two days later. The operations proved to be an extraordinary success and lasted until the blockade was lifted on 11 May 1949.

The Royal Signals support to the operation was directed by Colonel L. de M. Thullier OBE, Chief Air Formation Signal Officer, Headquarters British Air Forces of Occupation. His account of the operation and the part played by 11th Air Formation Signal Regiment appeared in The Wire in March 1950, which is easily found in the archive.[1] Other unit articles can be found in various editions from 1947 to 1950.

The importance of the work and the manner in which it was executed resulted six awards to 11th Air Formation Signal Regiment, which were announced in the 1950 New Year honours list.[2] Unfortunately, the original recommendations have not survived.

OBE:

Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel A. T. Sladen[3]

MBE:

Warrant Officer Class II (Squadron Sergeant Major) G. M. Derwent[4]

British Empire Medal:

Squadron Quartermaster Sergeant (Foreman of Signals) C. P. Bolton, for his work establishing a new teleprinter room at Headquarters British Air Forces of Occupation.

Sergeant S. F. Caird, NCO i/c Lines, No. 67 Wing Signal Troop.

Sergeant N. S. Richardson, No. 112 Terminal Equipment Troop.

Signalman P. Cowley.

[image error]Squadron Quartermaster Sergeant (Foreman of Signals) C. P. Bolton BEM

Sergeant S. F. Caird BEM

1. (Back) ‘Operation Plainfare’. The Wire, March 1950, pp 91-93.

2. (Back) London Gazette 2 January 1950; 38797.

3. (Back) Obituary: The Wire, January 1985, p. 8.

4. (Back) Details corrected in London Gazette 28 March 1950; 38873.

June 20, 2022

Gallantry During The Blitz

This blog post originally appeared in 2016 on my website dealing with Royal Signals honours and awards. With the closure of that site I have updated it and moved it here. The events that it commemorates took place just over 81 years ago (I also wrote about them here).

Signalman Robert Hamilton Tinto GM

On the evening of 29 December 1940, a German bombing raid on London caused what became known as the ‘Second Great Fire of London’. Most frequently illustrated by the iconic photograph of St Paul’s Cathedral that came to symbolise London in the blitz, the attack targeted the City of London and the high explosive and incendiary bombs started a firestorm that swept all before it. The area destroyed was more than that devastated by the Great Fire of 1666 and cost the lives of over 160 civilians and 14 firemen.[1]

St Paul’s Cathedral, 30 December 1940

Although the target of the raid was north of the Thames, south of the river the Borough of Southwark suffered grievously too. At 7.30pm the air-raid shelter on Keyworth Street[2] was hit and destroyed; thirteen civilians were killed and many more injured.[3] Many of the injured were trapped by debris and had to wait until rescue crews dug them out hours later. Signalman Robert Tinto—a former GPO telegraph linesman from Maryhill in Glasgow—was one of a number of men stationed nearby[4] who went out to help with the rescue. He crawled into the shelter through a small hole, ‘an aperture which seemed impossible for any human to get through’,[5] and, with the rescue crew working immediately above him, he dug with his bare hands to get to four trapped civilians. For four hours he then remained with them, reassuring them and administering morphine to the badly injured. The rescue crew, meanwhile, attempted to move a large slab of concrete from above where he had tunnelled, which, had it fallen, would have had ‘disastrous results’.[6]

The award of the George Medal to Signalman Tinto was published in the London Gazette on 27 May 1941. The fierce bombing raid and firestorm of 29 December resulted in 44 gallantry awards—one MBE, eight George Medals, 22 British Empire Medals and 13 Commendations for Brave Conduct—those awards may be seen here. After the war, Robert Tinto remained in the Army and by 1959 he was the Squadron Sergeant Major of 234 Signal Squadron in Malta. He died in 2003 in Dunbar, East Lothian, aged 87.

[image error]The George Medal

The George Medal was instituted in 1940 to reward ‘acts of great bravery’.[7] Six awards of the George Medal have been made to personnel of the Royal Corps of Signals, and one award was made to a schoolboy who later served with the Corps. Four of the military awards were for saving life during the Second World War, one was for gallantry during the rescue of the hostages held in the Iranian Embassy in 1981, and one was for gallantry on operations in Northern Ireland. The award to schoolboy Derrick Baynham was for the attempted rescue of crashed aircrew in heavy seas off Anglesey in 1941.

Acknowledgements:

Imperial War Museum: Photograph of St Paul’s Cathedral

Noonans: Photograph of the George Medal.

1. (Back) For a full account of this attack see: Gaskin, M. (29 September 2005). Blitz: The Story of 29th December 1940. London: Faber & Faber.

2. (Back) Named after Lance Corporal Leonard James Keyworth VC.

3. (Back) The 13 civilians killed were: Mr Frederick William Feldon, his wife Mrs Ethel Annie Feldon and 15-year-old daughter Ethel Feldon of 40 Keyworth Street; Mr Thomas Gleid and Mrs Mary Ann Glover, a widow, of 96 Lancaster Street (the former wrongly commemorated as dying on 29 October 1940); Mrs Ellen Flora Morris, a pensioner, of 48 Ontario Street; Mrs Edith Stead, from Drighlington, Yorkshire, of 166 Southwark Bridge Road; Mrs Caroline Maud Still and her 17-year-old daughter Caroline Ellen Still of 269 Southwark Bridge Road; Mr Alfred William Swain, aged 19, and his brother Mr George Frederick Swain, aged 17, of 89 Lancaster Street; and Mr Robert J. Webber and his wife Sarah Maria Webber of 100 Borough Road.

4. (Back) S.E.L.T.T.G. (South East London Technical Training Group).

5. (Back) The National Archives (TNA): Home Office: Inter-departmental Committee on Civil Defence Gallantry Awards: Minutes and Recommendations. Case Number: 997. Name: R H Tanto. (sic) HO 250/23/997.

6. (Back) Ibid.

7. (Back) London Gazette 31 January 1941; 35060, p. 623.

The Book Cover

This article was published originally in 2021 on my website dealing with Royal Signals Honours and Awards to describe the various photos on the book’s cover; it is reproduced here in anticipation of that website closing.

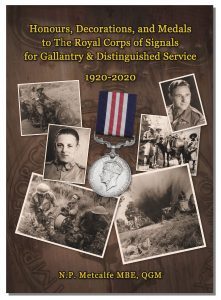

Designed by Jag Lal, the cover of Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals for Gallantry & Distinguished Service 1920-2020 shows seven images, with another making up the textured background.

Designed by Jag Lal, the cover of Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals for Gallantry & Distinguished Service 1920-2020 shows seven images, with another making up the textured background.

Royal Signals dispatch rider in Waziristan, 1935

Left Top: A Royal Signals despatch rider in Waziristan, 1935. He is riding the military version of the 350cc Douglas Motors L3 which in India replaced the well-regarded Triumphs in the early 1930s. In 1932 Kohat District Signals reported in The Wire: ‘Since receiving our new pattern Fords, we have also had a new outfit of Douglas motor-cycles. The old Triumphs have passed out, much to our regret, and the steady purr of the Doug has come to stay.’[1] They were not as popular as the Triumphs and apparently not as reliable. 1st Indian Divisional Signals on exercise south-east of Rawalpindi in late 1932 recorded: ‘There was plenty of hard work for everyone, but the Douglas motor cycles could not stand up to the type of country over which they had to work and were all out of action before the ‘war’ proper commenced, leaving the three Triumphs to carry out the motor cycle D.R. work.’[2] By the Second World War they had been largely replaced by the Norton WD16H.

Signalman Arnold Topliff BEM

Left Centre: Signalman A. O. Topliff BEM, Hong Kong Signal Company. Having survived the sinking of the prisoner of war transport, the SS Lisbon Maru, and having swum for several miles to an island, Signalman Arnie Topliff saw that another survivor was unable to reach shore and was being swept out to sea by a change in the current. Although exhausted, and at considerable risk, he went back into the water and rescued an officer of the Middlesex Regiment, for which he was awarded the British Empire Medal. In other blogs here you can read more about the Hong Kong Signal Company and the Lisbon Maru and Arnie Topliff.

Linemen of 56th (London) Divisional Signals in the Italian Campaign

Left Bottom: Linemen of 56th (London) Divisional Signals in the Italian Campaign during the attack on Monte Camino on 3/4 December 1943. During the action Lance Sergeant R. Lowe of ‘J’ Section (167th (London) Infantry Brigade Signal Section) was awarded the Military Medal for his conduct at the height of the attack between 2 and 4 December: ‘In spite of considerable and persistent enemy fire [he] carried out a difficult and hazardous climb carrying a spare wireless set. He visited each of the four battalions in turn, repairing sets where possible or if not carrying back damaged sets to brigade headquarters and later taking replacements up himself. Ronald Lowe was also mentioned in despatches for his earlier conduct during the Battle of Anzio. He was born on 21 June 1921 and lived in Barnard Castle in County Durham where he worked as an engineer for the General Post Office, as had his father who served with the Royal Engineers Signal Service during the First World War with ‘L’ Signal Battalion.[3] Ronald Lowe returned to work for the General Post Office after the war. He died at Sandbach in Cheshire on 24 January 1998, aged 76.

Military Medal

Signalman Alfred Coxon MM

Centre: The Military Medal awarded to Territorial Army Signalman Alfred Coxon of 70th Infantry Brigade Signal Section, 23rd (Northumbrian) Division, for his bravery as a despatch rider during the Battle of France on 20 May 1940 when he carried out a difficult run ‘although subjected to enemy bombing and machine-gunning with armoured fighting vehicles operating in the area’. The only element of 23rd (Northumbrian) Divisional Signals to deploy to France was a small despatch rider section commanded by Lieutenant D. C. J. Bell. Highly praised for its work, the men of the section earned a Military Cross (Bell) and two Military Medals (Coxon and Signalman T. Thompson). Prior to the war Alfred Coxon had worked on the staff of the Clerk of Durham County Council. He later served throughout the Western Desert and Italian Campaigns. The medal image was provided by the auction house Noonans.

Right Top: Lance Corporal D. A. Bowstead MM. During the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944, Lance Corporal Danny Bowstead came ashore on Gold Beach at D+15 minutes with the signal section supporting 90th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery. Throughout the day he operated his set under the most gruelling conditions. His medal recommendation, written by the commanding officer of 90th Field Regiment, recorded that his efforts contributed ‘in no small measure to the success of 1 DORSET’, the leading battalion. You can read more about Danny Bowstead on this account of the awards earned by Royal Signals personnel on D-Day.

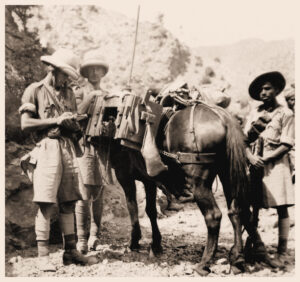

Signalman J. Petrie, Waziristan District Signals and his W/T Detachment in Waziristan in 1937

Right Centre: Signalman J. Petrie, Waziristan District Signals (far left) and his W/T detachment in Waziristan in 1937. A typical detachment comprised one or two Royal Signals operators, an Indian Signal Corps mule driver, and a mule mounted with the No. 1 set and its batteries and ancillaries. The Royal Signals operators were armed with revolvers and the mule driver with a rifle (Short Magazine Lee–Enfield No. 1 Mk. III). Signalman Petrie was mentioned in despatches for his conduct during the campaign. He had served in England for a year after completing his training before being posted to India in 1933. He transferred to the Army Reserve in 1939 but was recalled when war broke out. He was mentioned in despatches for a second time as a sergeant for his conduct during the Burma Campaign.

A line detachment under shell-fire in the Salerno beachhead

Signalman Forbes Kirkhope DCM

Right Bottom: A line detachment under shell-fire in the Salerno beachhead in the early days of the assault on mainland Italy, 14 September 1943. The landings saw the only award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal to a Royal Signals soldier during the Italian Campaign for ‘conventional’ operations. Signalman W. A. F. Kirkhope landed with 2nd Special Service Brigade Signal Troop at Vietri sul Mare and was decorated for performing line repairs ‘under conditions of extreme danger’ and, after relieving an exhausted operator at a relay station, remaining at his post without sleep for a further day and under very heavy mortar fire to maintain the only link forward. Forbes Kirkhope was born in Dunfermline, Fife in 1919. He was the grandson of the Labour politician William Adamson MP, a former Secretary of State for Scotland. He attended Dunfermline High School before joining a firm of chartered accountants in Edinburgh but enlisted in November 1939 before taking his final examination. Kirkhope was commissioned into the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders on 16 August 1945 (he was married the following day) and relinquished his commission after the war. Having qualified as an accountant, he established a successful business in the royal burgh of Brechin in Angus. Forbes Kirkhope DCM died on 23 February 2008 at Hay Lodge Hospital in Peebles, aged 88.

Distinguished Conduct Medal

Bob Tracy, 1939, Bulford

Finally, the underlying image is the Distinguished Conduct Medal awarded to Sergeant A. H. Tracy of 1st Armoured Divisional Signals, earned for his bravery in the actions against the Abbeville/St. Valery bridgehead west of the River Somme prior to 5 June 1940, when he was captured. His award—the only gallantry medal to 1st Armoured Divisional Signals for the Battle of France—was published in November 1945 after his release. Arthur Herbert ‘Bob’ Tracy was born on 7 February 1914 in Lancashire and was a pre-war regular soldier. Having served for several year in India, he joined Mobile Divisional Signals (later re-designated 1st Armoured Divisional Signals) at Bulford in 1939 and was promoted to sergeant after the outbreak of war as Royal Signals expanded in size. After his capture, he was held at Stalag XX-A/Stalag 357 in Thorn (Toruń) in Poland until September 1944 when he was moved to a camp at Oerbke, on Lüneburg Heath in Lower Saxony. In April 1945 during the move of prisoners of war eastwards he escaped and lived rough until he met up with the advancing Allies. Due to his treatment as a prisoner of war Tracy suffered later from poor health; he died at Chelmsford and Essex Hospital on 20 June 1963, aged 49, after suffering a heart attack.

1. (Back) The Wire, June 1932, p. 241.

2. (Back) The Wire, March 1933, p. 112.

3. (Back) 211164 Sapper Fred W. Lowe. ‘L’ Signal Battalion was responsible for the Line of Communication and by the end of the war comprised over 4,100 all ranks.

June 12, 2022

‘Darkest Hour’, Calais—Capture and Escape

This article was published originally in 2018 on my website dealing with Royal Signals Honours and Awards; it is reproduced here in anticipation of that website closing.

I suspect many of the readers here will have seen Darkest Hour and Gary Oldman’s superb performance as Churchill. One aspect of the final days of the fighting in France that gets a deserved mention in the film is the ill-fated defence of Calais by Brigadier Claude Nicholson’s 30th Motor Brigade. Ordered to hold out at all cost, the Brigade and French troops in the town fought bravely until, position by position, they were forced to surrender on 26 May 1940. Two German divisions were diverted from their attack on the Dunkirk perimeter.