‘Darkest Hour’, Calais—Capture and Escape

This article was published originally in 2018 on my website dealing with Royal Signals Honours and Awards; it is reproduced here in anticipation of that website closing.

I suspect many of the readers here will have seen Darkest Hour and Gary Oldman’s superb performance as Churchill. One aspect of the final days of the fighting in France that gets a deserved mention in the film is the ill-fated defence of Calais by Brigadier Claude Nicholson’s 30th Motor Brigade. Ordered to hold out at all cost, the Brigade and French troops in the town fought bravely until, position by position, they were forced to surrender on 26 May 1940. Two German divisions were diverted from their attack on the Dunkirk perimeter.

Headquarters 30th Motor Brigade was split between an Advanced Headquarters in the Citadel in the Old Town and a Rear Headquarters in the docks’ railway station; the latter moved on the afternoon of 26 May to a small fort at the end of the quay. First of the two to fall was Rear Headquarters which was completely surrounded and being slowly reduced by accurate and heavy mortar fire. The Royal Signals element there, led by Lieutenant William Millett of the Brigade Signal Section, and remnants of 1st Battalion, Rifle Brigade and 1st Battalion, Queen Victoria’s Rifles surrendered at about 4.00pm. The Advanced Headquarters, defended by French troops and a small party of Royal Marines, was overrun between 4.30pm and 5.00pm; it was here that Brigadier Nicholson and the Brigade Major, Captain Dennis Talbot were captured.

[image error]British Newspapers Archive." data-image-caption="Daily Record, Friday 31 May 1940

" data-medium-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." class="wp-image-7653 size-large" src="http://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-cont..." alt="" width="625" height="375" srcset="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con... 1024w, https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con... 300w, https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con... 768w, https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con... 1536w, https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con... 2048w, https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con... 624w" sizes="(max-width: 625px) 100vw, 625px" />Daily Record, Friday 31 May 1940

In common with other gallantry awards made to those captured in the Battle of France, the awards for those who fought at Calais were published after the release of prisoners—in this case in a single Gazette dated 20 September 1945. Nicholson was made a Companion of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, backdated to 25 June 1943, the day that he died in captivity in Rotenburg Castle in the Fulda valley in Germany. To Royal Signals went a Military Cross to Lieutenant Millett and three mentions in despatches.[1]

A former regular soldier of the Corps—he was a Sergeant when he was commissioned in April 1940—Millett sailed for France with 30th Motor Brigade Signal Section on 22 May. By the time his award came to be considered he had been captured, escaped and returned to the United Kingdom, posted to the Middle East and recaptured in eastern Libya; hence the delay in publication of his Military Cross.[2] His first adventure in occupied France is documented in a most detailed report written when he and his two fellow escapees returned to England.[3]

Escape Report (opens as pdf)

The account by Millet, Talbot (the Brigade Major) and Captain Alick Williams, the Adjutant of 2nd Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps, is long but worth reading in full. This amusing excerpt gives a feel for the final stages of their escape:

10 June 1940 (At a house near a chateau on the north bank of the River Authie near Groffliers.)

The people were ready to sell food and gave them a meal; they proved to be the caretaker of the chateau, his family and two refugee friends from Paris. Captain Williams asked and asked again about boats. When finally they left, the Parisians followed him out and told him, in strict confidence, of a party of French soldiers who had a motor boat ready laid up in a creek nearby. They also showed them a deserted house which would make a safe refuge.

The French party consisted of a very stout-hearted Capitaine called Bret, two other officers and four other ranks of the 23rd and 25th Tirailleurs d’Algerie. The boat—the St. Valery—was a cabin cruiser with a small cabin forward and lay in a narrow twisting creek off the River Authie. The French had moored her so badly a couple of days before that she had tipped over at low tide and the engines had been flooded with the result that they had not been able to get it to go. Since then they had dried out the engine and also obtained some oars. Owing to the persuasive powers of Captain Williams and the kindness of Capitaine Bret, the three Englishmen were finally accepted by the French as passengers in their already rather crowded boat.

11 June. As the tide was more or less suitable it was decided to make an attempt to get away this night. Water and as much food as possible was collected from the Chateau and neighbouring farm. When it became dark the party proceeded to the creek and loaded up the boat. The French seemed to have masses of kit and no attempt was made to stow it away. The Englishmen were there still rather on sufferance so it was difficult to interfere. Our allies’ lack of knowledge of affairs nautical soon became apparent for, owing to the incorrect casting off of the mooring ropes, the boat was suddenly discovered to be drifting inland on the flow with its stern towards the sea and it was the three English passengers who had to correct this error rather forcibly and quickly. The boat was then rowed rather erratically towards the mouth of the creek—when the rowing commenced, it was discovered that the only people on board. who could row were two of the passengers, Captains Talbot and Williams, though Capitaine Bret and Lieutenant Millett did their best and proved apt pupils.

The boat was anchored in the mouth of the creek, while the French who were in charge of the engine, endeavoured to start it. The more the engine refused to start, the more excited and energetic the engineers became until finally they prevented any further chance of getting it to go by smashing the starting gear. By this time it was rapidly becoming light and the tide was fast running out and so there was no alternative but to turn the good ship round and row her back again to the creek. This was eventually achieved after much gesticulation and shouting. How the German observers, reported to be in Berck lighthouse and the water tower near Fort Mahon failed to see the comedy, it is difficult to imagine, as it was broad daylight before the boat was safely moored again.

12-16 June. During this period, by devious slow means, a French mechanic was obtained and it took him three visits, including the removal of the starting apparatus back to his garage, before the engine was ready for work once more. Much kindness was shown to the party by the local landlord who was the biggest and wealthiest landowner in the district, and an Englishman who had lived in France for twenty-six years and owned a large cafe in Abbeville. Supplies were again obtained from the Chateau and farm, and they were greatly augmented as the result of two very successful sheep stealing excursions carried out by three of the Frenchmen and Captain Williams.

It was finally decided to make for England rather than Dieppe or Le Havre which had been the original plan. The French Capitaine most gracefully handed over command of the expedition to Captain Williams.

Night 16/17 June. The engine was finally repaired by the afternoon of 16th June and although the tide was really one hour too early (9.00 p.m.) for purposes of security, it was decided to make the attempt rather than risk another day of inactivity. Germans had already been seen at the chateau and at the neighbouring farms. At 8.30 p.m. the party went down to the boat in pairs. All spare kit was placed in the tiny fo’c’sle, and every member of the crew was given a job including three Frenchmen who were detailed for A.A. [anti-aircraft] defence. Captain Talbot was appointed navigator and helmsman while Captain Williams and Lieutenant Millett took charge of the engine. At 9.30 p.m. on the ebbing tide the moorings were finally cast off and the great journey commenced. Everyone was in highest of spirits and even the failure of the engine to do more than start and then stop again immediately failed to dishearten the crew. With a scratch four at the oars and with the help of the tide, the river was reached safely in spite of what appeared to be an extremely bright evening. Great difficulty was found in trying to discover the main channel of the river, and eventually at 9.15 the boat ran ashore on a sandbank. The tide was running out fast now and it was essential to lighten the boat and to push her off into deep water. The three English officers jumped overboard at once, but it took some time and much language before the remainder of the crew could be induced to remove their trousers. Eventually, with great relief, the boat was pushed to the channel, and the mouth of the river, and the open sea was reached mostly by rowing, but assisted by occasional spasms from the engine by about 11.00 p.m. The first Frenchman was sick in the river, the second as the open sea was reached, and the remainder by midnight.

17 June. Sunrise on the 17th June saw the St. Valery only off Le Touquet, but the engineer’s knowledge of the engine improved as the day went on and the periods of running increased to a quarter and half an hour. When off Boulogne, Captain Talbot set a course across the Channel for Folkestone, the method of navigation being right-hand on the tiller and left-hand holding a flickering and unknown compass as far away from the engine as possible. This compass had been presented by one of the Frenchman.

About midday, the wind freshened and a choppy beam sea caused some anxiety as it sounded as if the propeller shaft had worked loose. The engine stopped once again, however, and, avoiding a rapidly approaching and threatening German mine by energetic rowing, the boat was finally moored to the ‘Vergoyer’ [sic] buoy after a few exciting moments. Here lunch was taken and enjoyed, it is regretted, by only the three Englishmen and one Frenchman.

At about 4.00 p.m. ‘tea’ was taken—this was once again an English meal—in sight of what was fondly hoped to be a bank of haze along the coast. About 5.00 p.m. Dungeness was sighted on the port bow with great joy and the sight of land caused no less than three Frenchmen to join their Capitaine outside the cabin. From this time onwards ships began to appear on the horizon and then more and more land until Dover Castle could be discerned on the starboard bow. The engine had now run out of oil and it was only Captain Williams’ genius that kept it going. Nobly assisted by Able-seaman Millett, he had worked away at the engine gradually becoming its master, while Captain Talbot navigated and steered, without pause for twenty-three continuous hours. At

Lt W. Millett on exercise in England before sailing for the Middle East

7.30 p.m. when about 8 miles out from Folkestone, the engine finally stopped and a distress signal in the shape of Captain Williams’ once white towel was hoisted on an oar. Half an hour later a destroyer in the shape of HMS Vesper made a welcome appearance and, taking the party on board, left the good ship St. Valery adrift. The proverbial kindness of the Royal Navy was more than shown by Lieutenant Commander W F. E. Hussey DSO, and his officers and men, while the destroyer took the allied party to Dover.

For their successful escape, Williams was awarded the Military Cross[4] and Millett and Talbot were mentioned in despatches.[5] Both Talbot and Williams went on to have distinguished careers both becoming general officers. Millett’s career had a more ignominious end—he was cashiered and jailed in 1953 for fraud while in charge of a Sergeants’ Mess account.

Comments posted on the original article:

Neale Millett, 26 February 2018:

Hi, I am the son of Lieutenant William Millett mentioned in the story above. Although he spoke little of his wartime experience, in my teens I found a mimeographed copy, which I still have, of the full report you quote and this did elicit some more information about his service. His permanent commission was delayed as he had been adopted at birth with no paperwork or birth certificate so, as I understood him, he was still acting Lieutenant at the time of Calais.

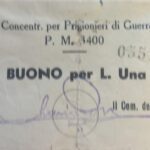

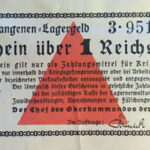

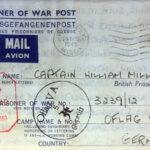

After some leave he was posted to the desert and captured. He was initially in prisoner of war camps in Italy, being moved North as the Allies advanced, ending up io Germany from where he was released at the European wars end.

He later served in Vienna before returning to Shrewsbury from where my mother and a 5 year old me were rapidly dispatched to live with her sister. I knew nothing of his being cashiered, just being told he was ‘away’ although in later life I suspected something of that sort.

On release he moved to the Chelmsford area, working for Marconi, ending his career as Stores Superintendent for GEC/Marconi before retiring in 1978 & passing away in 1980.

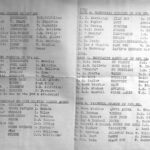

In response to this Neale Millet and I had several exchanges and he provided some fabulous photographs from his father’s service, particularly as a PW—see the gallery below.

Richard Talbot, 8 September 2018:

I am Dennis Talbot’s eldest son. My father also received the MC for Calais but no citation can be found. He and Alick Williams remained friends until their deaths after the 50th anniversary of ‘The Last stand at Calais’. I have a photo of them together at our home ‘50 years on’. The famous ‘dodgy’ compass is in the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Museum in Maidstone. Among my father’s papers I recently found a POW postcard from Nicholson in response to a letter from my father. I have been in touch with Nicholson’s son Richard who holds the famous painting ‘Last stand at Calais’. I have also recently been reading the recent Pardoe and Jay Calais POW books both of which give a very good picture of what would have happened to Talbot, Williams and Millet if they had not jumped the column as it stopped heading south (towards the French) and turned east towards Germany.

Col (Ret’d) Richard Talbot CD, Vancouver Island

International Bomber Command Centre):

International Bomber Command Centre):WE have just opened the “Cabaret Balalaika.” Nightly at 6 a huge crowd gather outside the “Empire Theatre” to watch guests arriving to dine – nearly all arrive in fancy dress or smart uniform. Famous Bill Millet, D.S.O., is the brilliantly dressed commissionaire ushering in the diners. They gasp as they see for the first time the transformed theatre.

The whole ceiling is light baby blue, the walls treated in graded shades of blue ranging from light to royal – single-line animal décor fill the dark panels in apricot to match the other furnishings, brilliant white napery, glittering silver and glass, and bowls of brilliant flowers fill the tables. Smartly uniformed waiters, mâitre d’hotel and head waiters in immaculate tails strut the floor shepherding diners to their reserved tables. The males seek the bar, their ladies gossip together admiring their dresses. On the stage a large accordion bands [sic] plays lively music.

“Dinner is served,” a five-course dinner commencing with iced soup, to coffee and petit fours, during which the accordions are replaced by a Gypsy Orchestra, the leader serenading the ladies on his violin. Then the Cabaret dance Orchestra, immaculate in white monkey jackets with blue lapels, bow ties and cummerbunds, play. The guests dance, the wine flows freely, a beautiful iced cake is raffled nightly and each night £35 or so goes to the Y.M.C.A.

In a spot-lit semi-circle on the floor comes the first turn of the floor show.

All the best features of London clubs have been hired to entertain – “Ranson and Rossita,” dancing divinely, “The Masqueraders.” a Russian trio in excellent voice; “Bubbles” that famous child impersonator; the “Western Brothers,” as British as ever; a fencing dance to rumba rhythm, and a musical mime “Hey Taxi.”

The floor show is over, the diners dance – the iced cake is presented to the lucky ticket holder – the guests depart. Three hours of London night life have been brought to every officer in Oflag VA.

The Cabaret Balalaika. Millett wrote: ‘Floor show is a tune called ’Underground’ and depicts a journey through London by Taxi and Underground.’

" data-medium-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." />

1. (Back) Captain Francis Richard Barnard Bucknall, Lieutenant Charles Alwyn Atkinson, and 2316102 Warrant Officer Class III E. G. Heaseman. All were captured.

2. (Back) Having been posted to the Middle East, he was captured, probably on or about 8 April 1941 while serving with 2nd Armoured Divisional Signals, during the advance of the Afrika Korps through eastern Libya. Held in PW camps in North Africa and Italy, he was moved to Oflag V-A in Weinsberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany following the Italian Armistice in September 1943 as the Allies advanced north through Italy.

3. (Back) The National Archives. Recommendation for Award for Millett, W. WO 373/60/302.

4. (Back) LG 3 September 1940; 34936, p. 5326.

5. (Back) LG 20 December 1940; 35020, p. 7183 & p. 7190.