Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 8

October 3, 2016

Blacker’s Letters – September 1916

The letters written by Lieutenant Colonel Blacker in September 1916 have now been published and you can read them all on the project’s website. The Battalion continues to settle into its new routine in increasingly wet weather.

The River Douve, which ran near the Battalion’s trenches, flooding them when it burst its banks.

September 18, 2016

Sacrifice – Connecticut

The stories of the seven men commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Connecticut are finished and may be read here. Most were United States citizens but one was a British officer working as a small-arms inspector with Winchester and Remington, which were contracted to manufacture the P14 rifle.

The P14 Rifle

The ‘Rifle, .303 Pattern 1914’, known as the P14, was a new rifle, based on the design of the Pattern 1913 Enfield (the P13), an experimental rifle designed to fire a new .276 Enfield rimless cartridge, which had been developed as a result of experience during the Boer War. The outbreak of the First World War made the adoption of this new cartridge impracticable and, in essence, the P14 was the P13, built to accept the standard British .303 cartridge. 1,235,293 rifles would be manufactured by Winchester and Remington (and one of Remington’s subsidiaries). Initially issued in some numbers, the P14 was replaced in front-line service in 1916 by the ubiquitous Short Magazine Lee Enfield No.1 Mk3*, which was by then being produced in the United Kingdom in sufficient quantity. The P14 was then used primarily as a sniper rifle and was highly regarded for its accuracy.

September 4, 2016

The Royal Reserve Regiments and The Royal Garrison Regiment

In researching the essay about my great-great-uncle Moses Neill, I came across reference to the Royal Garrison Regiment, into which he enlisted in 1902. A search for information about the Regiment revealed little and the information that was easily found has proven to be wrong or inaccurate. A number of sources conflate the Royal Garrison Regiment with the earlier Royal Reserve Regiments; while it is true that the men of the latter were recruited for the former, these two organisations were raised at different times and for very different purposes. In the sections below, hyperlinks will lead to a transcription or copy of the relevant Royal Warrant or Army Order.

The Royal Reserve Regiments

Officers of the Royal Irish Fusiliers Reserve Regiment, 1900

The Royal Reserve Regiments of cavalry and infantry was a corps of the British Army authorised by Royal Warrant, dated 17 February 1900 and promulgated by Army Order Army 48, for ‘the defence of the United Kingdom’ during the Boer War. The move to re-enlist former soldiers was one of a number taken to expand the British Army, both regular and volunteer units, for service in South Africa and at home.[1]

In parallel with the issuance of the Royal Warrant, in a letter to the Commander-in-Chief[2] from the Queen’s private secretary written from Osborne House on 17 February,[3] the Queen’s wishes regarding the naming of the new units were made known:[4]

My dear Lord Wolseley,

As so large a proportion of the Army is now in South Africa, the Queen fully realises that necessary measures must be adopted for home defence.

Her Majesty is advised that it would be possible to raise for one year an efficient force from her old soldiers who have already served as officers, non-commissioned officers or privates.

Confident in their loyalty to country and devotion to her Throne, the Queen appeals to them to serve once more in place of those who for a time are absent from these islands and who, side by side with the people of her colonies, are nobly resisting the invasion of her South Africa possessions.

He Majesty has signified her pleasure that these battalions be designated ‘Royal Reserve Battalions’ of her Army.

Subsequent to the original Royal Warrant, an Army Order issued on 7 March 1900 gave more detail about the terms of service, confirmed that the corps into which men were to be attested was the ‘Royal Reserve Regiments’, and gave more organisational details. In particular, the Order laid out the alignment between Line regiments and the new Royal Reserve Regiments; for example, it stated that the Royal Irish Fusiliers Reserve Regiment would comprise men of the ‘Royal Innsikilling Fusiliers, Royal Irish Fusiliers, Royal Munster Fusiliers, and Royal Dublin Fusiliers’. It noted that members of the Militia were excluded from enlistment. A later Army Order added to the elements of the Army excluded from re-enlistment or transfer.[5] An Army Order of 5 April confirmed the names of the cavalry regiments and laid out the establishments for both cavalry and infantry: The establishment of each infantry battalion was to be 1,006 all ranks (24 officers, two warrant officers and 980 other ranks), although the two Scottish battalions were authorised an additional nine men—a sergeant piper and eight other pipers. The establishment of the cavalry regiments was 594 all ranks (23 officers, two warrant officers and 269 other ranks), and 417 horses, of which six were draught animals. Army Order 106 of May 1900 allowed for the re-enlistment of some men in the Royal Reserve Regiments for service in South Africa.[6]

Recruiting was enthusiastic but there were delays in fully equipping the new regiments and battalions, which resulted in Parliamentary questions that were widely reported in the press. A total of 24,130 men were enlisted for service with the Royal Reserve Regiments before recruiting was stopped on 10 June 1900.[7]

Four regiments of cavalry, and 18 battalions of infantry in 10 regiments were raised. Two of the cavalry regiments were based in England and two in Ireland. Of the infantry battalions, 13 were in England, two were in Ireland, two in Scotland and one in Wales:

Her Majesty’s Reserve Regiment of Dragoon Guards (Newbridge, County Kildare, Ireland)

Her Majesty’s Reserve Regiment of Dragoons (York, Yorkshire, England)

Her Majesty’s Reserve Regiment of Hussars (Hounslow, Middlesex, England)

Her Majesty’s Reserve Regiment of Lancers (Ballincollig, County Cork, Ireland)

1st Battalion, Royal Guards Reserve Regiment (London; Wellington and, from October 1900, the Tower of London, England)

1st Battalion, Royal Home Counties Reserve Regiment (Aldershot, Hampshire, England)

2nd Battalion, Royal Home Counties Reserve Regiment (Aldershot, Hampshire, England)

1st Battalion, Royal Northern Reserve Regiment (Woking, Surrey, England)

2nd Battalion, Royal Northern Reserve Regiment (Pembroke Dock, Pembrokeshire, Wales)

3rd Battalion, Royal Northern Reserve Regiment (Aldershot, Hampshire, England)

4th Battalion, Royal Northern Reserve Regiment (Aldershot, Hampshire, England)

1st Battalion, Royal Rifles Reserve Regiment (Portsmouth, Hampshire, England)

2nd Battalion, Royal Rifles Reserve Regiment (Portsmouth, Hampshire, England)

1st Battalion, Royal Southern Reserve Regiment (Portsdown Forts, Hampshire, England)

2nd Battalion, Royal Southern Reserve Regiment (Portsmouth, Hampshire, England)

1st Battalion, Royal Lancashire Reserve Regiment (Preston, Lancashire, England)

2nd Battalion, Royal Lancashire Reserve Regiment (Aldershot, Hampshire, England)

1st Battalion, Royal Scottish Reserve Regiment (Fort George, Inverness, Scotland)

2nd Battalion, Royal Scottish Reserve Regiment (Edinburgh, Midlothian, Scotland)

1st Battalion, Royal Eastern Reserve Regiment (Warley, Essex, England)

1st Battalion, Royal Irish Reserve Regiment (Athlone, Westmeath, Ireland)

1st Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers Reserve Regiment (Belfast, County Antrim, Ireland)

In a very British way, there was little uniformity of badges and emblems across this new organisation. Officers were to wear uniforms ‘as a general rule similar to that used in the corresponding regiments’ and the men would wear the uniform of regiments ‘serving at home’, eschewing the khaki ‘fad’.[8]

Other Ranks Helmet Plate, Reserve Regiment of Lancers

Each of the cavalry regiments had a unique badge—common to all were the gothic letters ‘H M R R’, surmounted by St. Edward’s crown and below the letters was a scroll inscribed ‘DRAGOON GUARDS’, DRAGOONS’, ‘HUSSARS’, or ‘LANCERS’; collar badges were smaller and omitted the crown. In addition, each of the cavalry regiments had unique officers’ and other ranks’ helmet plates.

The single battalion of the Royal Guards Reserve Regiment was organised into three ‘divisions’ each wearing the uniform and badges of the three Regiments of Foot Guards—Grenadier Guards, Coldstream Guards and Scots Guards. The Royal Scottish Reserve Regiment wore the uniform of The Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment) and, on their glengarries, the two battalions wore a thistle badge either on a red, pinked felt background or on a black background with a black feather hackle. The Royal Rifles Reserve Regiment wore the uniform of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps and had as its badge the light infantry bugle. The other English infantry battalions wore the uniform of the Royal West Surrey Regiment and the badge used (for cap and collar) was the Royal Arms; this badge latter became that of the Royal Garrison Regiment (see below). The Royal Irish Reserve Regiment wore the uniform of the Royal Irish Regiment and its badge was a harp surmounted by a crown, similar to the badge of the Royal Irish Constabulary, with the officers’ full-dress badge being surrounded by a shamrock wreath. The Royal Irish Fusiliers Reserve Regiment wore the uniform of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers); its badge was a fired grenade with a shamrock trefoil superimposed on the grenade body.

The men of other arms were organised into units already existing and wore the uniforms and badges of their corps.

The Royal Reserve Regiments were disbanded on 14 May 1901. Men not enlisting into the new Royal Garrison Regiment were sent on furlough until the expiration of their term of service. The issue of the ‘character’ of men that was noted on discharge papers caused some debate. With only one year in the Army, those men who were discharged could only receive a character of ‘very good’. Men whose character had previously been ‘exemplary’ were unable to explain the reason for this variation. The issue resulted in a flurry of letters and commentary in the press.

The Royal Garrison Regiment

Men of the 5th Battalion, Royal Garrison Regiment at Wellington Barracks, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1905

The Royal Garrison Regiment was a corps of the British Army authorised by Royal Warrant, dated 23 February 1901 and promulgated by Army Order 59, for garrison duty ‘…in the Mediterranean and at certain other non-tropical stations’.[9] Although eight battalions were planned, only five and a depot were raised.[10] Four battalions were raised in 1901—the 1st, 3rd and 4th battalions were sent to Malta, whilst the 2nd was sent to Gibraltar. In 1902, the 5th Battalion was raised for garrison duties in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The establishment of the Battalions was 1,012 all ranks.[11] Initially, recruiting for the new regiment was restricted to men of the infantry battalions of the Royal Reserve Regiment, including those who had been discharged from that regiment within the preceding year. That latter restriction was removed (by Army Order 98 of 1902[12]) and recruitment was widened to include discharged soldiers of the regular Army and of the Royal Marines, Royal Marine Artillery and ex-infantry soldiers of the Militia.[13]

The cap badge of the Regiment was the Royal Arms in brass, with a smaller version worn on the collar; the shoulder title comprised the letters ‘R G R’, also in brass.[14]

[image error]

3rd Battalion Memorial, St Paul’s Pro-Cathedral, Valetta, Malta

This was a regiment of the regular British Army and, notwithstanding some differences in terms of service, some men of the regiments were accompanied by their families to their duty stations in the Mediterranean and Canada and separation allowance was paid to those whose families remained at home. When the 3rd Battalion left for Malta, for example, it was accompanied by 38 wives and 54 children.[15] This proved to be a considerable expense; the age of the men in the Battalions of the Regiment meant that many more were married than would be found in a battalion of a Line regiment.[16]

In 1903, a new Royal Warrant, dated 28 February 1903 and promulgated by Army Order 35, superseded the original Royal Warrant. It laid out amended terms of service, the principle changes being that the length of service was increased from two to three years and that the Regiment ‘may in the future be required to serve in the South Africa Command…’[17] The four battalions in the Mediterranean were duly sent to South Africa to undertake garrison duties in 1904.

Recruitment tailed off after the initial effort in 1901: 4,052 men were recruited that year, 2,250 in 1902, 1,121 in the first nine months of 1903, and a further 561 men before recruiting ended in 1904; a total of 7,984 all ranks.[18], [19] The decision to abolish the Royal Garrison Regiment had been taken prior to their departure for South Africa and recruiting for the Regiment stopped on 14 April 1904.[20]

In 1905, three battalions (the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th) returned from South Africa and the 5th Battalion, with its families, returned from Canada; all were then disbanded. The 1st Battalion remained at Fort Napier in Pietermaritzburg, Natal throughout 1906, where it reduced in size as men came to the end of their engagements.[21] The Regiment was finally disbanded on 1 September 1908 during the period of the Haldane Reforms.[22]

Five battalions of infantry and a regimental depot were raised:

Regimental Depot.

Established at Warley Barracks, Essex on 10 May 1901.

February 1903, the Regimental Depot relocated to Fort Widley, one of the defensive forts on Portsdown Hill near Cosham in Hampshire.

24 February 1906, all men with more than 12 months’ unexpired service embarked for South Africa to join the 1st Battalion.[23]

15 April 1906, the Regimental Depot at Fort Widley was closed[24] and the maintenance of the Regiment’s records fell to the Records Office, Winchester.

Commanding Officers:

Captain Frank Bevan, The Northumberland Fusiliers, June 1901-January 1902.

Major Almeric Edmund Frederic Rich (formely The Lincolnshire Regiment), January 1902-November 1903.

Lieutenant Colonel Harrison Midwood (formerly The Highland Light Infantry and Second-in-Command of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Garrison Regiment), November 1903-April 1906.

1st Battalion.[25]

Raised at Aldershot, Hampshire on 10 April 1901, at Salamaca Barracks.

23 May 1901, embarked on SS Formosa at Southampton for Malta, arriving on 31 May, where it relieved 1st Battalion, Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment).

Garrison duties at Fort Verdala, Cospicua, on the eastern side of the Grand Habour until 1903, when it moved to Fort St. Elmo in Valetta. In early 1904 the Battalion moved to Gozo.

29 April 1904, embarked on SS Sicilia for Durban, South Africa, arriving on 26 May 1904.

Took over garrison duties at Fort Napier in Pietermaritzburg, Natal.[26]

The Battalion remained in Pietermaritzburg until its remnants returned to the United Kingdom in 1906, after which the Battalion was disbanded.

Commanding Officers:

Lieutenant Colonel Frederick John Evelegh (formerly The Oxfordshire Light Infantry), April 1901-mid-1906.

Major Christopher Montagu Blackett (formerly The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own)), 1906.

2nd Battalion.

Raised at Aldershot, Hampshire on 10 April 1901, at Talabera Barracks.

15 May 1901, embarked on SS Dilwara at Southampton for Gibraltar, arriving on 20 May, where it relieved 1st Battalion, Princess Charlotte of Wales’s (Royal Berkshire Regiment).

11 April 1904, embarked on SS Dunera for Durban, South Africa, arriving on 4 May.

Took over garrison duties at Standerton in the Transvaal.

11 July 1905, embarked on SS Dunera at Durban for Southampton, arriving on 4 August.

The 2nd Battalion was disbanded on 15 September 1905.

Commanding Officer: Lieutenant Colonel Charles Owen Hore CMG (formerly The South Staffordshire Regiment), April 1901-September 1905.

3rd Battalion.

Raised at Warley, Essex on 20 June 1901.

20 September 1901, embarked on SS Assaye at Southampton for Malta, arriving on 28 September.

Garrison duties at Fort Verdala, Cospicua and Lower St. Elmo Barracks, Valletta. In late 1902 the Battalion moved to Mtarfa Barracks.

20 April 1904, embarked on SS Plassy for Capetown, South Africa, arriving on 13 May.

Took over garrison duties at Tempe Barracks, Bloemfontein in Orange River Colony.

9 September 1905, embarked on SS Dilwara at Capetown for Southampton, arriving on 2 October.

The 3rd Battalion was disbanded on 30 November 1905.

Commanding Officer: Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Stringer (formerly The Royal Welsh Fusiliers and Royal Home Counties Reserve Regiment), May 1901-May 1905.

4th Battalion.

Raised at Warley, Essex on 1 September 1901.

12 September 1901, moved to Aldershot.

7 December 1901, ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘D’ Companies embarked on SS Assysia at Birkenhead for Malta, arriving on 18 December.

12 May 1902, Battalion Headquarters and the remainder of the Battalion embarked on SS Borneo at Royal Albert Dock, London for Malta, arriving on 21 May.

Garrison duties at Fort Verdala, Cospicua.

29 June 1904, embarked on SS Dunera for Durban, South Africa, arriving on 25 July.

Took over garrison duties at King’s Hill, Harrismith, in Orange River Colony.

4 July 1905, embarked on SS Dilwara at Durban for Southampton, arriving on 29 July.

The 4th Battalion was disbanded on 30 September 1905.

Commanding Officer: Lieutenant Colonel Wilfred Heaton (formerly The South Wales Borderers and Royal Irish Fusiliers Reserve Regiment), September 1901-September 1905.

5th Battalion.

Raised at Aldershot on 1 March 1902.

20 September 1902, embarked on SS Aurania for Halifax, Nova Scotia, arriving on 30 September.

Garrison duties at Wellington Barracks, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

14 November 1905, embarked on SS Canada at Halifax for Liverpool, arriving on 24 November.

The 5th Battalion was disbanded on 31 December 1905.

Commanding Officer: Lieutenant Colonel Henry Melville Hatchell DSO (formerly The Royal Irish Regiment), August 1902-December 1905.

[image error]

1. (Back) For the measures taken in 1900 see: ‘General Observations on the Regular Army.’ (9 April 1901). Annual Report of the Inspector General of Recruiting for the Year 1900. Part 1. pp 3-4. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

2. (Back) Field Marshal the Right Honourable Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley, KP, GCB, GCMG (later made OM).

3. (Back) Lieutenant Colonel Sir Arthur Bigge KCB, CMG; later Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Bigge, 1st Baron Stamfordham GCB, GCIE, GCVO, KCSI, KCMG, ISO, PC.

4. (Back) ‘Court Circular. The War in South Africa’. (21 February 1900). The Times. p 9.

5. (Back) These included ‘…men now serving with the Regular forces or in the Imperial Yeomanry, City Imperial Volunteers, or Volunteer companies formed for service in South Africa…’.

6. (Back) Army Order 106 laid down that the men had to be under 37 years of age and to have completed 12 years of service in the Army. On re-enlistment they would be retained until age 41 or until they had completed 21 years’ of service, if that occurred before they reached the age limit. These men remained eligible for the second bounty (£10) on the anniversary of their enlistment into the Royal Reserve Regiment. Army Order 62 of 1901 ended re-enlistment of men of the Foot Guards or Infantry of the Line under these arrangements, citing the issuance of Army Order 59 of 1901, which established the Royal Garrison Regiment. Men of the Reserve Regiments of cavalry could continue to re-enlist, however, and Army Order 62 laid out the regiments to which they were to be allocated.

7. (Back) ‘General Observations on the Regular Army.’ (9 April 1901). Annual Report of the Inspector General of Recruiting for the Year 1900. Part 1. p 4. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

8. (Back) Commentary on the uniforms and badges of the Royal Reserve Regiments appears in numerous regional newspapers in early April 1900. See, for example: ‘Uniform of the Royal Reserve Regiments’. (3 April 1900). The Times. p 2.

9. (Back) ‘AO 59—Royal Garrison Regiment.’ (8 March 1901). The Monthly Army List for March, 1901. pp 1417-1418. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

10. (Back) A saving of £530,000. See: ‘Comparison with Estimates for 1903-04.’ (1904). Memorandum of the Secretary of State for War relating to the Army Estimates for 1904-05. p 2. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

11. (Back) ‘Royal Garrison Regiments.’ (6 May 1901). Hansard. HC Deb. Vol 93 c737.

12. (Back) ‘AO 98—Royal Garrison Regiment—Enlistment of Ex-Royal Reservists.’ (30 April 1902). The Monthly Army List for May, 1902. p 1410. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

13. (Back) ‘Royal Garrison Regiment.’ (20 February 1902). Annual Report of the Inspector General of Recruiting for the Year 1901. Part 1—General Observations on the Regular Army. p 6. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

14. (Back) The cap badge has been worn by various military corps over the years including some of the Royal Reserve Regiments, the Labour Corps in the First World War (until late-1918), and the General Service Corps. It is most often seen in modern use by soldiers under training in the first phase at Army Training Regiments. The principle difference is the crown used in the era of different monarchies.

15. (Back) ‘Troops for Malta.’ (24 September 1901). Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette. p 8.

16. (Back) It was estimated that a battalion of the Royal Garrison Regiment would cost about £20,000 (about 30%) more than a Line battalion undertaking the same duties. See, for example: ‘The Royal Garrison Regiment.’ (8 October 1906). The Times. p 3.

17. (Back) ‘AO 35—Royal Garrison Regiment.’ (9 March 1903). The Monthly Army List for March, 1903. p 1405. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

18. (Back) ‘Royal Garrison Regiment.’ (28 January 1905). Annual Report of the Director of Recruiting and Organization for the Year Ended 30th September 1904. Part 1—General Observations and Recruiting for the Regular Army. p 8. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

19. (Back) ‘Annual Report of Recruiting for the Year Ended 30th September, 1907.’ (1907). General Annual Report on the British Army for the Year Ending 30th September, 1907. Section 1. p 4. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

20. (Back) ‘Royal Garrison Regiment.’ (28 January 1905). Op. Cit.

21. (Back) Various sources show it as being less than 200 men strong at the beginning of 1906. See, for example: ‘Imperial Troops in Natal.’ (4 April 1906). Hansard. HC Deb. Vol 152 c1288. The Army List for July 1908 (published on 30 June 1908) shows the Battalion as being at Pietermaritzburg (for Pretoria), commanded by Captain Francis William Lawson (formerly The Connaught Rangers, Reserve of Officers).

22. (Back) ‘War Office.’ (1 September 1908). London Gazette. Issue 28173, p 6371. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

23. (Back) ‘Significant Army Order.’ (10 February 1906) Belfast Telegraph. p 5.

24. (Back) ‘The Army.’ (2 April 1906). Portsmouth Evening News. p 5.,

25. (Back) The movements of all five Battalions are taken from: The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO). (1901-1920). Stations of Regiments. WO 379/15.

26. (Back) Garrison locations for all four battalions in South Africa are taken from the Army List.

August 31, 2016

Blacker’s Letters – August 1916

The letters written by Lieutenant Colonel Blacker in August 1916 have now been published and you can read them all on the project’s website. There is a familiarity to the tone of the letters; the Battalion is engaged in much the same work that it was in the Somme region prior to the attack on 1 July. The difference being the weather, the flies and the poor billets out of the line.

Cloth Hall, Ypres

New Headstone for Company Serjeant Major George Mayer Symons

Warrant Officer Class 2, Company Serjeant Major, George Mayer Symons, The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), attached to the British Military Mission, died during the influenza epidemic at Camp Lee, Virginia on 8 October 1918. He was buried in Poplar Grove National Cemetery near Petersburg. Unfortunately, his grave marker was incorrectly inscribed. On Saturday 27 August I was privileged to attend the dedication ceremony for the new headstone. You can read about the ceremony here.

The new gravestone for George Symons, August 2016

August 20, 2016

My Family at War – Part 6: Moses Neill

2739 Private Moses Neill

Bugler Moses Neill in India

Moses Neill—known as ‘Mosey’—was the older brother of my great-grandfather William Neill. He served with The Royal Irish Rifles from 1890 for 12 years, including during the South African War, and a further two years with the Royal Garrison Regiment.

He was born on 28 April 1873 at at Tullyherron, a townland in Donaghcloney parish near Waringstown.[1] After he left school, he became a labourer. He enlisted into the Militia on 5 September 1889, aged 16 but declared himself to be a year older, for a six-year engagement with the 5th Battalion (Royal South Down Militia), The Royal Irish Rifles.[1] He was allocated the regimental number 1356. The following year he decided to enlist into the regular Army and he attested on 26 May 1890. He joined the Depot in Belfast, where he was renumbered 2739, and after his period of training was posted to the 2nd Battalion in Malta. The Battalion had arrived in Malta from Egypt in March 1891 and Private Moses Neill joined in September that year; he was posted to ‘H’ Company. He was appointed Bugler on 7 May 1892.

On 18 November 1894 the Battalion sailed for India on the troopship Victoria, arriving at Bombay (Mumbai) two weeks later. Moses Neill would spend four years in India in the Bombay Presidency, in Bombay until 1896 and thereafter in Poona. During this period it is evident that his conduct was not ideal; he was deprived of his Lance Corporal’s appointment twice, forfeited his good conduct pay, and his extension to 12 years’ service (granted in 1892) was cancelled on 4 June 1897. He arrived back in Ireland on 21 January 1898 and was discharged and transferred to the Army Reserve two days later.

Army Order 23 of 1898 made provision for the re-enlistment of men from the Army Reserve for a bounty of £20, a considerable sum then, and Moses Neill re-enlisted under these conditions on 16 November 1898 and was posted to the Depot. The 2nd Battalion had arrived back in Ireland on 16 February 1899 and Private Neill rejoined his Battalion in Belfast on 25 February.

The outbreak of war against the Boers in South Africa resulted in the 2nd Battalion sailing from Queenstown (Cobh) in County Cork on the SS Britannic on 24 October 1899. The Britannic arrived in Cape Town at the end of November and, after collecting Major General Sir William Getacre KCB, DSO, General Officer Commanding 3rd Division, and his staff, she sailed on to East London in Eastern Cape. Here the Battalion moved by train and foot to Putter’s Kraal. There is no record the course of his war in South Africa, nonetheless, it may be surmised from his medal clasps that he took part in the action at Stromberg on 10 December—a misdirected action that cost the Battalion 12 men killed, over 50 officers and men wounded, and over 200 captured. The Battalion remained in the region until 15 March 1900 when Major General Gatacre’s force crossed the Orange River into the Orange Free State. There followed the disastrous action at Reddersburg, which resulted in three companies of the Battalion being captured. These two setbacks resulted in the Battalion being employed largely in garrison duties in the Orange Free State (after its capture renamed Orange River Colony). What part Moses Neill played in all this is not known.

The Queen’s and King’s South Africa Medals

In the early part of this garrison duty in early November 1900 he was charged with drunkenness and tried by Field General Court Martial. The sentence was severe—70 days’ field imprisonment. He seems to have kept himself out of trouble thereafter, however, being awarded his good conduct pay in January 1902. The Battalion returned home in July 1902. Moses Neill was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal with clasps ‘CAPE COLONY’, ‘ORANGE FREE STATE’, and ‘TRANSVAAL’, and the King’s South Africa Medal with clasps ‘SOUTH AFRICA 1901’, and ‘SOUTH AFRICA 1902’. His time expired, he was discharged on 31 August 1902 and awarded the gratuity for service during the South Africa campaign—£6.15.0.

On 16 October 1902 he enlisted again, into the Royal Garrison Regiment, and was allocated the regimental number 5890. The Royal Garrison Regiment, initially of four battalions, had been authorized in February that year. It recruited former soldiers, many of whom had served in the Royal Reserve Regiment on garrison duty in the British Isles. Three of the four battalions were sent for garrison duty in Malta and a fourth was sent to Gibraltar. A fifth battalion was raised later for service in Halifax, Nova Scotia. It is not known which of the battalions Moses Neill served with. After his two-year engagement, he was discharged at Fort Widley—one of the defensive forts on Portsdown Hill and by that time the Depot of the Regiment—on 15 October 1904.

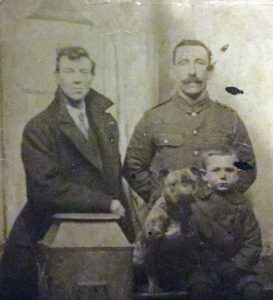

Mosey Neill & William Neill, 1914

Moses Neill returned to Lurgan and became a sailor, a ship’s rigger; little is known of his later working life. On 23 February 1907, he married Maria McCleary, a mill worker from Lurgan, in Moira Presbyterian Church.[1] The couple had a son, James, born on 9 January 1910 and Maria and her son continued to live with her family in Avenue Road, Lurgan while Moses was away from home. A daughter, Ellen, was born there on 15 October 1911. The family moved to Belfast and lived at 29 St Andrews Square, East, where their third child, Thomas, was born on 27 February 1914. Moses Neill died of myocarditis on 2 October 1954 at 12 Mount Vernon Park in Belfast, aged 81. He was buried in the north-west part of Belfast City Cemetery on 5 October, in grave V1/191. Maria died on 14 January 1963 and his son James died on 23 August 1976; both are buried with him.

1. (Back) He was the fifth of the seven children of Gilbert Neill (born 1837), my great-great-grandfather, and Ellen Thompson (born 1833), who were married on 2 September 1864 in Magheralin Parish Church (The Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, Magheralin). The other children were: Annie (born 1863), Thomas George (born 3 November 1865), Joseph (born 28 October 1867), Elizabeth Jane (born 21 August 1870), William (born 1 June 1876), and Hamilton (born 5 September 1884). Moses Neill was my great, great uncle.

2. (Back) The Royal Irish Rifles had been formed in 1881 as a consequence of the Cardwell Reforms, which restructured the British Army. The 83rd (County of Dublin) Regiment of Foot and the 86th (Royal County Down) Regiment of Foot amalgamated to become, respectively, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, The Royal Irish Rifles. The reforms also aligned militia units with the county regiments. In this case the Royal North Down (Rifles) Militia became the 3rd Battalion (Royal North Down Militia), with its headquarters at Newtownards; the Antrim (Queen’s Royal Rifles) Militia became the 4th Battalion (Royal Antrim Militia), with its headquarters at Belfast; the Royal South Down Militia became the 5th Battalion (Royal South Down Militia), with its headquarters at Downpatrick; and the Louth (Rifles) Militia became the 6th Battalion (Louth Militia), with its headquarters at Dundalk.

3. (Back) Maria McCleary was born on 8 February 1879, the daughter of James and Jane McCleary (registered as Marie McCleery). James Neill’s birth registration records his mother’s name as ‘McClury’. Ellen and Thomas Neill’s birth registrations record their mother’s name as ‘McCleery’.

August 15, 2016

My Family at War

My great-grandfather William Neill was the influence behind my exploration of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers that led to Blacker’s Boys. Since writing the book I have discovered other relatives who served during the First World War, and some who served during the Boer War and the Second World War. Each has a very different story:

14577 Sergeant William Neill DCM

Transport Sergeant, 9th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (County Armagh)/9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) throughout the First World War. He was my great-grandfather.

Sergeant William Neill DCM

5/4732 Sergeant Hamilton Neill

Attached to 2nd Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles during the South Africa War in 1902, later served with the 5th Battalion in the Special Reserve, and then with 2nd Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles throughout the First World War. Wounded on 16 June 1915 at the Battle of Bellewaarde. He served as a regular soldier after the war with The Royal Ulster Rifles and, for six years, was attached to the 2nd Battalion, Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway Regiment. He was my great-great-uncle.

Sergeant Hammie Neill

2739 Private Moses Neill

A regular soldier in 2nd Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles, he served in Malta, India and during the South Africa War and later with the Royal Garrison Regiment. He was my great-great-uncle.

Bugler Moses Neill in India

17/673 Lance Corporal Thomas George Bunting

9th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (West Belfast) during the First World War. Killed in action in the period 1-3 July 1916 at Thiepval. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. He was my first cousin, twice removed.

Private Thomas Bunting

18/1141 Lance Corporal Robert Thompson

15th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (North Belfast) during the First World War. Captured on 21 March 1918 at Racecourse Redoubt, St Quentin. He was my maternal great-uncle.

Rifleman Robert Thompson

Private Samuel Thompson

Ulster Home Guard during the Second World War. He was my maternal grandfather.

Private Samuel ‘Sammy’ Thompson

Private James Thompson

Ulster Home Guard during the Second World War. He was my maternal great-uncle.

Private James ‘Jimmy’ Thompson

Private John Thompson

Ulster Home Guard during the Second World War. He was my maternal great-uncle.

Private John ‘Johnny’ Thompson

In addition, my wife’s great-grandfather enlisted in Canada:

504226 Private John Palmer Bowes

2nd Canadian Divisional Mechanical Transport Company, Canadian Army Service Corps, Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War.

Private John Palmer Bowes

August 6, 2016

Charleville Communal Cemetery, France

Recently, two parallel pieces of research overlapped, out of which came an idea for a short piece about a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery that no longer exists. As with all things about the First World War, the story has more facets than at first may seem to be the case.

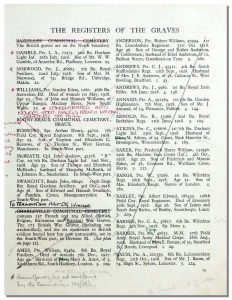

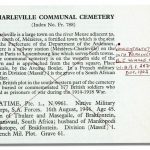

The CWGC register for Charleville Communal Cemetery, closed in 1962

The town of Charleville sits on the north bank of the River Meuse in the Ardennes department, the only department of France to be wholly occupied by the German army throughout the First World War. Famous for the Charleville musket—a mainstay of the Continental Army during the American War of Independence—and, more recently, as the birth place of the poet Arthur Rimbaud, in modern times the town merged with the adjacent town of Mézières. The latter was the capital of the Ardennes region, a function that now falls to the combined commune of Charleville-Mézières.

After falling to the German army early in the war, in September 1914 the town became the site of the supreme German headquarters,[1] the component parts of which were established in the best homes, chateau and municipal buildings throughout the town. An English language account of the German occupation of the two towns was written in 1919 and is worth reading.[2] In addition to the other facilities and organisations required to support an important garrison, a German military hospital was set up in Saint Remi primary school—Kriegslazarett 8, Remischule zu Charleville—to service the garrison and the region. Although French prisoners had been treated in the town in the civil hospital since 1914, in late 1917 the Kriegslazarett began to accept British prisoners of war.

The prisoners who died in the hospital were buried in the town’s old cemetery, known as ‘Cimetière du Boutet’, in the western suburbs of Charleville on Avenue Charles Boutet.[3] In his story of the occupation of the town, Domelier wrote:

‘There was another kind of ceremony which used to perturb the police, namely, the funeral of French or Allied soldiers. A certain number of these brave fellows had died in hospital and were buried in the cemetery at Charleville, in a plot specially reserved for our heroes.

At the beginning of the occupation, the bodies were handed over to the civil authorities, who celebrated their obsequies with due solemnity. A flag in the national colours was laid upon the coffin; the fire-brigade, in uniform, but without arms, paid military honours in the name of the French army. The municipality was officially represented, and in its train marched a long procession of patriots. The hearse was buried beneath flowers and wreaths tied with tricolour ribbons.

At the graveside, the head of the municipal council spoke a few words of farewell, impregnated with a lofty spirit of patriotism.

Germany was in danger! First of all, one of Bauer’s agents was sent to the cemetery to eavesdrop on the speeches and conversations. Next came an order to remove the flags and national colours of ‘the enemy’. Then the procession was limited to fifty persons, and finally, as the result of an incident created on 5th April, 1918, by a pastor who celebrated the obsequies half an hour before the time fixed by the Kommandantur (an incident which provoked a protest on our own part, and cost us seven days in prison at the Charleville Detention House), the population was forbidden to take any part whatever in these obsequies. Only a delegation from the municipal council, composed of three members, was admitted to the cemetery.

These regulations lasted till 10th November, 1918, when Charleville was finally liberated, and, without constraint or spies, but under the shells of a bombardment, was able to bury two brave young poilus who had been mortally wounded at the crossing of the Aisne.’[4]

Buried there by the end of the war were 341 Allied casualties. They were mostly men who had died as prisoners of war, most of whom had died in the Kriegslazarett in Charleville. Of these, 177 were British, 137 were French, three were from the United States and the remainder were Belgian, Romanian and Russian.

The Russian prisoners were men of the Russian Expeditionary Force. In December 1915, Tsarist Russia had agreed to send infantry brigades to fight with the French and British forces on the western front and in Salonika. Only four brigades had been dispatched by the time of the Russian revolution, comprising a little over 44,000 men, including 450 Estonians. The 1st Special Infantry Brigade, largely equipped by France, arrived in Marseilles in April 1916; the 3rd Special Infantry Brigade followed in August 1916, meanwhile the the 2nd and 4th Brigades were sent to Salonika. The two Brigades on the Western Front took part in the Neville Offensive in April 1917, suffering 4,542 men killed wounded and missing.[5]

The three United States casualties will be the subject of another essay on the Sacrifice blog.

The Special Memorial to Private W J Scott

The Imperial War Graves Commission established Charleville Communal Cemetery in the south-west part of the town cemetery, in Division M. Although mostly buried in national groups, some French, Russian and Romanian casualties were buried amongst the British graves. In 1962 Charleville Communal Cemetery was closed. The remains of the British and United States casualties were removed and reinterred in Terlincthun British Cemetery at Wimille in early December 1962. The reinterred comprised 170 known casualties, one unknown British soldier, and one officer and two soldiers of the United States Army. The British casualties were reinterred in Plots VIII (Rows B, C & D), and Plots XVI and XVII (Rows E & F) (see the cemetery map). In addition, a soldier of the Native Military Corps of the South African Army, who died in 1944 and who had been buried in the French plot at Charleville, was reinterred in Plot XIX at Terlincthun. The graves of six other British soldiers buried in Charleville Communal Cemetery had not been identified when the cemetery was constructed in the years after the First World War. They were originally commemorated on a cross inscribed ‘Buried in this cemetery, actual graves unknown’. Subsequently six headstones were erected inscribed ‘Known to be buried in this cemetery’. In Terlincthun British Cemetery six new headstones were erected alongside the boundary wall in the south-east corner of the cemetery beside Plot XIX. Amongst them is an inscribed Duhallow Block, the last two lines of which are from Ecclesiasticus 44, chosen by Rudyard Kipling to commemorate those buried in another cemetery whose graves have been lost:

To the Memory of these six soldiers

Buried at the time in

Charleville

Communal Cemetery

Ardennes

But whose graves

Are now lost

Their glory

Shall not be blotted out

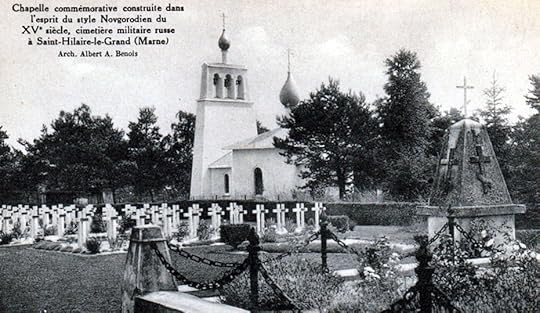

In 1988, 35 Russian soldiers were exhumed at Charleville and reinterred in the Russian military cemetery at Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand. Buried in this concentration cemetery are 915 Russian soldiers—489 known and unknown soldiers in individual graves, and 426 unknown soldiers in two ossuaries. Included amongst the graves is that of a Russian officer of 23rd Marching Regiment of Foreign Volunteers who was killed in 1940. All of the graves are inscribed, ‘MORT POUR LA FRANCE’. Nearby is a monument to the casualties of the 2nd Special Regiment, which is inscribed, ‘Children of France! When the enemy is defeated and you can freely pick flowers on these fields, remember us, your Russian friends, and bring us flowers!’.[6] Beside the cemetery is a small Russian Orthodox chapel, dedicated on 16 May 1937 to the 4,000 Russian soldiers who fell in France and in Salonika.

The Russian chapel at Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand

In Charleville there remains a French military plot in which are buried 141 soldiers from France and the French colonies who died during the First World War. Nearby is a memorial to the Russian soldiers who now rest in Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand.

French military graves at Charleville

In the gallery below may be found a roll of the British and Empire casualties originally buried in Charleville Communal Cemetery as recorded in the original registers of the cemetery produced by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

1. (Back) The General Headquarters of His Majesty the Emperor and King (Der Große Hauptquartier Seiner Majestät des Kaisers und Königs).

2. (Back) Domelier, H. (1919). Behind the Scenes at German Headquarters. London: Hurst and Blackett.

3. (Back) Charleville Communal Cemetery. Lat/Long: 49°46’33.7” N, 4°42’18.7” E. Digital Degrees: 49.776018, 4.705193.

4. (Back) Domelier. Op. Cit. pp 157-158.

5. (Back) For a detailed history of the Russian Expeditionary Force see: Cockfield, J H. (15 December 1997). With Snow on Their Boots: The Tragic Odyssey of the Russian Expeditionary Force in France During World War I. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

6. (Back) ENFANTS DE FRANCE! Quand l’ennemi sera vaincu et quand vous pourrez librement cueillir des fleurs sur ces champs souvenez-vous de nous VOS AMIS RUSSES et apportez-nous des fleurs.

August 1, 2016

Blacker’s Letters – July 1916

The letters written by Lieutenant Colonel Blacker in July 1916 have now been published and you can read them all on the project’s website. The 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers took part in the attack on 1 July and suffered grievously; the letters that follow are tragically sad. By the end of the month the Battalion is back in the line, much reduced but reinforced by men from the 10th (Reserve) Battalion. It has moved north, to a sector near Messines, south of Ypres, where it will remain until the summer of 1917.

The area over which the Battalion attacked on 1 July 1916.

July 20, 2016

Sacrifice – Rhode Island

The biographies of the six men buried in Rhode Island are now complete; two were American, two were British, one was Canadian and the nationality of one cannot be confirmed. One case is rather unusual: the ashes of Second Lieutenant Evanda Berkeley Garnett were repatriated to the United States from England over 40 years after his death in a flying accident.

Second Lieutenant Evanda Berkeley Garnett