Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 10

October 31, 2015

Sacrifice – Tennessee

The biographies of the three men buried in Tennessee are now complete.

The grave of Private Thomas Camp, Chattanooga National Cemetery

Private Thomas Camp served in England with 23rd Reserve Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force. He was sent home suffering from tuberculosis and died on 2 May 1921 in the United States Public Health Service Hospital at Whipple Barracks, Arizona. He is buried in Chattanooga National Cemetery.

Sapper Lee Arvel Moss served in France and Flanders with 4thBattalion, Canadian Railway Troops. He died of tuberculosis at Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, Quebec on 19 August 1919 and is buried in Short Creek Church Cemetery, near Athens.

Corporal William Vannah Taylor was born in Louisiana and served with 3rdCanadian Engineers Reserve Battalion in England. He died of nephritis in Memphis on 25 August 1919 and is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery Midtown.

Blacker’s Letters – October 1915

The letters written by Lieutenant Colonel S W W Blacker in October 1915 have now been published; you can read them all in chronological order at the link below. The A-Z of personalities has been amended to include those who will appear in November’s letters.

Blacker’s Letters

September 13, 2015

Nurses in the Great War

Three nurses and two wounded men

Many will be familiar with the Great War biographical memoire of Vera Brittain—Testament of Youth—in which she recounts her experiences as a VAD in England, Malta and France. The image of the doughty VAD from a well-to-do family, doing her bit—Lady Sybil in Downton Abbey—is how most people see the nurses of the Great War. This caricature was certainly my view for a long time, although I was aware of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, and the Royal Navy’s equivalent, Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nursing Service.

No-one has done more to enlighten me about the reality of nursing in the Great War than Sue Light, a nurse who has spent many years studying her profession, in particular military nursing in the late 19th and early 20th Century. Her work is extensive, thorough, detailed and fascinating.

The first of her three on-line information depositories is Scarlet Finders, which provides a wealth of information on British military nurses. Particularly interesting is the transcribed war diary of the Matron-in-Chief, British Expeditionary Force, France And Flanders.

A second website—The Fairest Force – Great War Nurses in France and Flanders—provides information ‘on all administrative and organisational aspects of the British military nursing services in France and Flanders during the Great War’, including areas such as pay, contracts, mobilisation and demobilisation, marriage, off-duty time, sickness and discipline.

Finally, her blog—This Intrepid Band—gives us her take on some of the issues and provides fascinating vignettes of some of the nurses of the Great War and the life they led.

For anyone seeking information about nursing in the Great War I cannot recommend her work highly enough.

Wounded and nurses in 2nd Western General Hospital in Manchester

The only area missing from her research is the Ulster Volunteer Force Medical and Nursing Corps, which provided trained nurses and the equivalent of VADs for UVF and other hospitals in Ulster during the Great War. This is a most difficult area to research due to the paucity of records, although a significant number of photographs and newspaper articles give some idea of the organisation and women of that unofficial but well-regarded Corps.

Volunteers and nurses of the UVF c1913

Acknowledgement:

Sue Light for the photographs of wartime nurses.

September 12, 2015

Sacrifice – Kentucky

The biographies of the two men buried in Kentucky are now complete.

Cave Hill National Cemetery

Private John Benjamin French was an African-American soldier, who served in France and in the Army of Occupation with No. 8 Company, Canadian Forestry Corps. He died of tuberculosis on 10 May 1920 in Montreal General Hospital and his remains were repatriated to Lexington, where he was buried in Cove Haven Cemetery.

Private James Henry Hartley was a British soldier who served in France and Flanders with the Machine Gun Corps. He was serving as an instructor at Camp Zachary Taylor when he died of pneumonia on 20 April 1918. He is buried in Cave Hill National Cemetery, Louisville.

August 21, 2015

The U.S. World War I Centennial Commission

I am very pleased to announce that our project Sacrifice has been endorsed by The U.S. World War I Centennial Commission.

August 13, 2015

Sacrifice – Louisiana

Greenwood Cemetery, New Orleans

The biographies of the four men buried in Louisiana are now complete. Two were covered in a previous post, the final two are Private Joseph Henry Wosikowski, Royal Marine Light Infantry and Private Francis George Thomas, Labour Corps.

It was satisfying to identify that Private Wosikowski’s name was spelled incorrectly on the Southampton war memorial and, having made contact with the War Memorials Officer at Southampton City Council, that is now recognised and his name will be added to the new glass panels at the memorial, correctly spelled.

‘Sacrifice – Louisiana

Greenwood Cemetery, New Orleans

The biographies of the four men buried in Louisiana are now complete. Two were covered in a previous post, the final two are Private Joseph Henry Wosikowski, Royal Marine Light Infantry and Private Francis George Thomas, Labour Corps.

It was satisfying to identify that Private Wosikowski’s name was spelled incorrectly on the Southampton war memorial and, having made contact with the War Memorials Officer at Southampton City Council, that is now recognised and his name will be added to the new glass panels at the memorial, correctly spelled.

August 1, 2015

Sacrifice – Update

I have been remiss in updating my blog with the progress of the Sacrifice project. In addition to completing the stories of men whose graves I visited last year or earlier this year, I have received great support from volunteers who have visited graves near where they live or where they have been on holiday.

The latest essays are those for:

Private Sylvester Williams, who served with No.2 Construction Company (Coloured) in France. He died of tuberculosis on 4 August 1919 after his return to Canada and is buried in Miami Cemetery, Corwin, near his home town of Waynesville, Ohio.

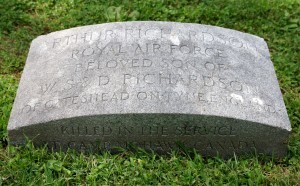

The grave of Cadet Arthur Richardson

Cadet Arthur Richardson, Royal Air Force, who drowned in an accident on 4 October 1918 near Camp Mohawk, Deseronto, Ontario and who is buried in Bellefontaine Public Cemetery, Saint Louis, Missouri.

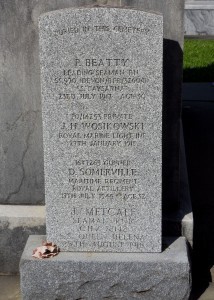

The Special Memorial in Greenwood Cemetery commemorating Leading Seaman Beatty and Seaman Metcalf

Leading Seaman Peter Beatty, Royal Navy, who was a gunner on the armed merchant ship SS Baysarua. He drowned on 23 July 1917 when the ship was alongside in New Orleans. He was buried in New Orleans in Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 but his grave was lost and he is commemorated in Greenwood Cemetery.

Seaman James Metcalf, Royal Naval Reserve, who was a gunner on the armed merchant ship SS Queen Helena. On 25 August 1918 when she was alongside in New Orleans, he fell off the ships gangway and drowned. He too was buried in New Orleans in Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 but his grave was also lost and he is commemorated in Greenwood Cemetery.

July 6, 2015

Sacrifice – Latest Post – Private James Doval Stewart

The latest addition to the Sacrifice project is the story of Private James Doval Stewart. The recruitment of Black Canadians for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force caused much debate in Canada. Many Black Canadians, swept along by patriotic fervour at the beginning of the war wanted to volunteer but prejudice prevented widespread recruitment.

The latest addition to the Sacrifice project is the story of Private James Doval Stewart. The recruitment of Black Canadians for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force caused much debate in Canada. Many Black Canadians, swept along by patriotic fervour at the beginning of the war wanted to volunteer but prejudice prevented widespread recruitment.

Private James Doval Stewart from Savannah, Georgia was one of approximately 165 African-Americans who served with 2nd Construction Company (Coloured). He died in 1919 and is buried in Savannah.

June 29, 2015

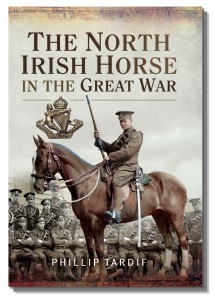

The North Irish Horse in the Great War by Phillip Tardif

A number of years ago, when I was putting together Blacker’s Boys, I began to share information with Phillip Tardif, an Australian whose grandfather, Frank McMahon, and my great-grandfather, William Neill, served together during the First World War. No-one knows more about the actions of the North Irish Horse or the men who served in its ranks and I am very pleased that Phillip has written this unique history of the Regiment. This short essay by Phillip is a super introduction to an excellent piece of work that will contribute much to the bibliography of work about Ireland in the Great War.

North Irish Horse Private, at Ballyshannon

In his account of the British Army’s role in the first months of the Great War, Sir John French, its former Commander-in-Chief, praised ‘the fine work done by the Oxfordshire Hussars and the London Scottish‘ as the first non-regular army units ‘to enter the line of battle‘ in the Great War. He added, by way of a footnote: ‘The North and South Irish Horse went to France much earlier than these troops but were employed as special escort to GHQ.’ In other words, these Irish units could not claim the distinction of being the first non-regulars involved in the fighting in the First World War. That would have been news to the families of North Irish Horsemen Private William Moore of Balteagh, County Londonderry, Private Henry St George Scott of Carndonagh, County Donegal, and Lieutenant Samuel Barbour Combe of Donaghcloney, County Down, whose deaths in September and October of 1914 were so far into the ‘line of battle’ that their bodies were never recovered. It would also have surprised Private William McLanahan of Garvagh, County Londonderry, who at this time ‘accounted for three Uhlans and took two horses single-handed‘. The truth is that the North Irish Horse was the first non-regular unit of the British Expeditionary Force actively engaged in fighting in the First World War, their presence in France dating from 19 August, just two weeks after Britain declared war, and their involvement with the enemy dating from just five days later.

North Irish Horse recruit Frank McMahon, 1914

The men of the North Irish Horse saw the war in almost every theatre (though mostly in France and Belgium), and through every phase. They were rearguard to the British army on the retreat from Mons and advance guard when the Germans were forced back to the Aisne in August and September 1914, taking part in many thrilling adventures that could have been taken word-for-word from a Boy’s Own story-book. As the lines became more static they took their turn in the trenches on the la Bassée front, on the Ancre and at Ypres. They amused themselves in the rear areas with polo, cock-fighting and steeplechases. They were at the Somme on 1 July 1916 as witness to the destruction of the 36th (Ulster) Division, and through that month cleared the battlefield of the massed and mangled bodies of the men who had fallen that day. At Messines and Passchendaele in 1917 they waited in vain for the order to advance through broken German lines. As infantry, they fought with the Ulster Division in the assault on the Hindenburg Line at Cambrai. They were in the lines in front of St Quentin when the Germans threw all they had at them in the offensive of March 1918, fighting a desperate retreat almost to the gates of Amiens. Weeks later at Kemmel they faced another equally ferocious offensive. As infantry and as cyclists they joined the ‘Advance to Victory’, a three month offensive that broke German resistance and brought the war to an end. By then the North Irish Horse was barely recognisable from that which was rushed to France in August 1914. When the war began they were a part-time reserve regiment, staunchly Unionist, and the regiment of choice for the wealthy landed gentry, farmers and rural tradesmen of Ireland’s north. By the end of 1918 they were very different—military professionals, urbane, more religiously diverse, and with officers and men drawn from as far afield as Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and Australia. Most obviously, they had been dismounted and converted to cyclists and infantry, retaining their ‘cavalry’ title in name only. Many whose service began in the North Irish Horse found themselves transferred elsewhere; they saw action as tank crews, airmen, military police and artillerymen in the European theatre, the Balkans and even further afield.

Many of them never returned to Ireland. They lie in Belgium, France, England, Egypt and Palestine. Their names are inscribed amongst the ranks of the missing at Pozières, Tyne Cot, Thiepval, Cambrai, le Touret, Loos and Ploegsteert, and on gravestones in more than ninety cemeteries around the world; stones that speak of family grief and faith:

The glory dies not, and the grief is past.

He died for us.

Having served his generation, by the will of God, he fell on sleep.

In memory of our son who is sadly missed, by his father, mother, brothers and sisters.

Not dead to those that loved him.

Death is swallowed up in victory.

Two North Irish Horsemen, one ‘unknown’

One hundred years on, their story is worth the telling, as it is for all those who served with the North Irish Horse during the Great War.

Phillip Tardif is the leading expert on the North Irish Horse in the First World War. His previously published works include ‘Notorious Strumpets and Dangerous Girls; Convict Women in Van Diemen’s Lane 1803-1829′ and ‘John Bowen’s Hobart: The Beginning of European Settlement in Tasmania’—the latter won the Tasmanian Bicentenary Local History Prize and was shortlisted for the 2005 Tasmania Prize. He lives in Canberra, Australia.

Phillip Tardif is the leading expert on the North Irish Horse in the First World War. His previously published works include ‘Notorious Strumpets and Dangerous Girls; Convict Women in Van Diemen’s Lane 1803-1829′ and ‘John Bowen’s Hobart: The Beginning of European Settlement in Tasmania’—the latter won the Tasmanian Bicentenary Local History Prize and was shortlisted for the 2005 Tasmania Prize. He lives in Canberra, Australia.

There is a huge amount of information about the North Irish Horse on Phillip’s website. His book ‘The North Irish Horse in the Great War‘ is published by Pen and Sword; it can also be bought at Amazon.