Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 14

October 26, 2014

Commonwealth War Graves Commission Commemorations in Maryland

I travelled to Baltimore to attend the annual meeting of the Western Front Association East Coast Chapter and decided to take the opportunity to investigate the deaths of the four CWGC commemorations in Maryland. An essay about each man will follow:

Acting Leading Seaman Joseph Thompson Clark, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, serving on the armed merchant ship SS Courtown. He died on 28 July 1917 and is buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery, Baltimore.

Leading Seaman Eustace Alfred Bromley, Royal Navy, serving on the armed merchant ship SS Kerry Range. He died on 30 October 1917 and is buried in Oak Lawn Cemetery, Baltimore.

Private Harry Ross, 97th Battalion, Canadian Infantry. He died on 6 May 1916 and is buried in Russian Cemetery, Philadelphia Road, Baltimore.[1]

Cadet Arthur William Webster Eden, Royal Flying Corps. He died on 21 December 1917 and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, Baltimore.

1. (Back) Ross is an alias and this cemetery no longer exists under this name. Research is required to identify exactly where this man is buried.

October 23, 2014

5 iconic sites added to this year’s Heritage at Risk Register | Heritage Calling

5 iconic sites added to this year’s Heritage at Risk Register | Heritage Calling.

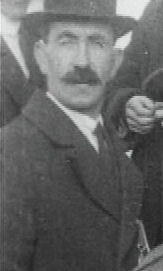

Steven Paul Ainsworth QGM

English Heritage ‘champions historic places and advises the Government and others on how to help today’s generation get the best out of our heritage and ensure it is protected for the future‘.

In the blog post above the photograph, English Heritage describes five sites added to the ‘at Risk Register’. One of those sites is Geevor Tin Mine at Pendeen in Cornwall. This was the site of an underground accident on 15 January 1980, when two miners were buried alive at the bottom of a narrow cavity. For their gallantry in the subsequent rescue attempt, Mr Stephen Ainsworth, a shift boss, and Mr Alan Brewer, a mine captain, were awarded the Queen’s Gallantry Medal.[1] The citation for their award read:

During the day shift on 15 January 1980, two miners were digging in the sides of an ore pile which had partially subsided, when there was a further major subsidence and they were engulfed and buried alive at the bottom of a narrow cavity.

Alan Brewer QGM

Mr. Ainsworth and Mr. Brewer were the first officials at the scene and realised the very serious difficulties presented by the overhanging sides of loose rock on the exposed walls of fractured granite; by the narrow working area and, not least, by a mass of unsupported ore sticking between the walls of that working space which might fall at the slightest vibration. Access to the men, therefore, had to be achieved without disturbing the sides of the pile or the central hanging mass and, at great personal risk, they improvised an unorthodox means of descent. With the assistance of a timber spreader which they erected between the walls, they suspended a pulley used in conjunction with a winch on the level above. They were then lowered by this contraption on a wire rope into the hole where they quickly located the men, but were unable to uncover their faces. Mr Ainsworth, a trained rescue team member, immediately directed an oxygen supply into the rock pile to assist the trapped miners’ breathing. Mr Brewer and Mr Ainsworth then worked alone in the cavity and began to make timber barricades to prevent the rock pile shifting or falls of rock rolling down and further burying the men. The rope pulley and winch could not be used to lower more men because of the ever increasing instability of the overhanging rock wall. When a safer and better access had been established additional men then descended by the less precarious means of a steel ladderway and assisted in putting up the wooden casings. Eventually after more than twelve hours the trapped men were freed and, at the time of their release, the conditions were so cramped that there was insufficient room to lay them down and they had to be supported upright to be strapped into the stretchers. Both men were alive when released, but one unfortunately died almost immediately afterwards.

Mr. Ainsworth and Mr. Brewer displayed bravery and devotion to duty of a high order when, without regard for their own safety, they worked in dangerous and cramped conditions for many hours to bring about the rescue of the trapped men.

Both men feature among the 1,044 recipients of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal in For Exemplary Bravery but I have very little other information about the incident, the casualties or the two rescuers. I would be pleased to hear from anyone who could add to the account of the rescue.

1. (Back) London Gazette: 13 February 1981. Issue 48522, p 2139.

October 22, 2014

SOLDIERS – An Exhibition by Tom McKendrick

SOLDIERS by Tom McKendrick

In For Exemplary Bravery, the history of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal, I wrote:

In a book such as this it is relatively easy to outline the events that prompt gallant and selfless action.

It is much harder to convey the horror or terror or sense of danger inspired by a raging fire, a furious storm at sea, the actions of an armed and violent person or war at its most personal and bloody.

It is impossible to convey adequately the long-term mental and physical consequences to many of those who have acted so gallantly.

I could not have had a better illustration to help make that point than the emotive portrait of Corporal David Timmins QGM by the Scottish artist Tom McKendrick.

Corporal David Timmins QGM

Tom has painted another recipient of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal—Lieutenant Colonel Peter Shields MBE, QGM. Peter was recognised for his gallantry in the aftermath of a massive ammunition explosion in Kuwait on 11 July 1991.

Lieutenant Colonel Peter Shields MBE, QGM

Both of these portraits feature in a new exhibition by Tom—SOLDIERS—which opens to the public at the Studio Pavilion, Bellahouston Park, Glasgow on Monday 3 November and will run until 22 December from 11.00am to 4.00pm daily.

Historically the relationship between artists and soldiers is long and well established. Rembrandt, Dix, Palmer, Bone, Orpen, Nash, Goya and many, more painted soldiers or produced work on military themes.

In this project Tom McKendrick has turned his eye to the human condition in the context of conflict.

In the exhibition are portraits and the experiences of people who have ‘served’, creating personal snapshots of recent British military history through the eyes of its witnesses.

In portraits painted to date, images and documentary evidence of people who fought at Monte Cassino, Dunkirk, Normandy, Greece, North Africa and Germany and the more up to date conflicts of Northern Ireland, Falklands, Iraq and Afghanistan have been recorded.

The aim of this project is to create a unique collection of images of individuals, their personal reflections and experiences in war.

October 20, 2014

Dr Henry William Wilson Davie MRCVS

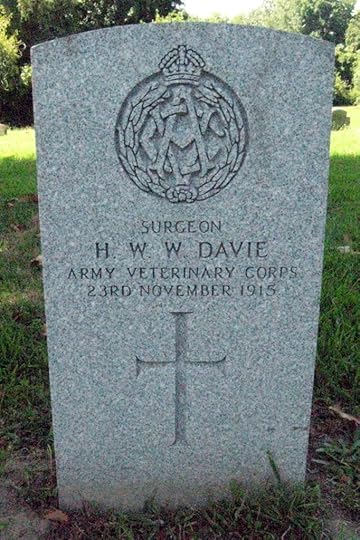

The grave of Dr Henry William Wilson Davie MRCVS at Greenlawn Cemetery, Newport News

This is part of a series of essays about the First World War casualties commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Virginia.

The death and commemoration of Dr Harry Davie are unique for two reasons. Firstly, he is the only civilian veterinary surgeon commemorated by the CWGC. Secondly, he is the only CWGC commemoration in Hampton Roads, the large metropolitan area in south-east Virginia based around the sea ports of Norfolk and Newport News. Sadly, the tragedy of his death was not the only terrible event to befall his family.

Henry William Wilson Davie was born in Barnstaple, Devon in the second quarter of 1871. His father, James Headon Davie, was a saddler—as was his father—who ran a business in The Square in Barnstaple. James and his wife Annie (née Wilson) had five children, of which Harry was the eldest.

Harry Davie graduated from the Royal Veterinary College on 12 May 1893 and registered as a Member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.[1] He returned to Devon and set up a successful veterinary practice in Crediton. In 1897 he married Mary Elizabeth Copp. They had a son, Thomas, and a daughter, Edith, and the family lived at The Green in Crediton, with Mary’s nephew William Abberley Copp.[2]

Following the outbreak of war, Harry Davie was contracted to provide a veterinary service in Devon in support of the purchase of horses by the Army Remount Service. At some time in 1915, he left his veterinary practice when he received an appointment to provide care on the trans-Atlantic crossings for mules and horses that had been purchased in north America.

The rapid expansion of the Army had resulted in an equally rapid expansion of the establishment for horses, particularly draft animals.[3] That, in turn, demanded an increase in the number of veterinary surgeons supporting the war effort. Requirements were met firstly by engaging local veterinary surgeons at civil rates of pay but ‘later it was found necessary to grant temporary commissions in the Royal Army Veterinary Corps to practically all veterinary surgeons, whether employed in the United Kingdom or overseas’.[4] It appears, however, that the veterinary surgeons employed to care for animals being transported by sea were civilians, recruited both from the United Kingdom and from the United States and Canada.[5] It was amongst this group that Harry Davie was employed.

The purchase of horses and mules in north America was a huge effort. The British Remount Commission was established in Montreal and commanded initially by Major General Sir Frederick Benson KCB.[6] Remount stockyards were established first in Canada and later in the United States—initial fears that the neutrality of the United States would prevent buying horses there proved unfounded. Once purchased, the horses were moved by rail to stockyards at one of the ports used by the Commission on the Atlantic seaboard.

It would have been impossible to achieve and sustain the British Army’s establishment for remounts were it not for the efforts of the Remount Commission. By 11 November 1918 the Commission had shipped 428,608 horses and 275,097 mules . By contrast, by 31 March 1920 horse purchases in the United Kingdom totalled 468,323.[7]

One of the largest east coast ports in the United States was (and remains) Newport News. The city was established as a settlement in the early 17thC and by the late 19thC had become a major rail terminal, linked to Richmond, the state capital, and, importantly, to Huntington in West Virginia on the Ohio River. Coal from West Virginia was a major commodity transported through the port, which led to the construction of large coal piers owned by the rail and shipping companies. The construction of a shipyard led to Newport News becoming the world’s biggest shipyard; it remains the largest in the United States. It was here that the Remount Commission established a large stockyard at Breeze Point, capable of handling up to 5,000 horses, and developed Newport News as the primary port for the shipment of horses from the United States. The importance of the depot was such that it became a target for German sabotage efforts in 1915 and a number of horses were poisoned.

Harry Davie had crossed the Atlantic a number of times in his role as a veterinarian officer. His first journeys were on the converted cattle-ship SS Russian[8] accompanied by a team of horsemen & muleteers and, on occasion, an assistant veterinary surgeon. In early November 1915 Harry Davie was in Newport News having been appointed as the veterinarian officer for the SS Orthia,[9] which was due to leave the port bound for the United Kingdom with a cargo of horses and mules.

On Wednesday 10 November 1915 Harry Davie disappeared. When news of his disappearance became known there was speculation in the press that he had ‘met with foul play’. His family was notified by telegram by the British vice-consul and, as police enquiries were made, ‘wild rumors (sic) …began to go the rounds’.[10]

Newport News Coal Piers

Two weeks later, on Tuesday 23 November, his partly decomposed body was found floating in the James River near the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway coal piers at the foot of 18th Street. The body was taken to the morgue of the undertaker William E. Rouse on 25th Street where it was examined at 5.00pm that evening by the coroner, Dr Henry F. James Jr. When no signs of violence were identified, and cash to the value of $24.50 and a valuable watch were found in his clothing, the coroner recorded that ‘I examined the body of Dr Harry Davey (sic) and the evidence causal to his death showing as accidental drowning on Nov. 23, 1915’.[11] It was speculated in the press that he had fallen off one of the piers in the area while out walking.

The death certificate, compiled by Warwick County, incorrectly registers his name as ‘Dr Harry Davey’. The details of Harry Davie’s name, occupation and age were provided to the county by Major R H Marsham, then the Staff Officer Embarkation of the British Remount Commission at Newport News.[12]

Harry Davie was buried at 10.30am on 24 November 1915 at Greenlawn Cemetery in Newport News, in a graveside service conducted by Reverend Henry G. Lane, the rector of St Paul’s Episcopal Church. The cemetery, established in 1888 as the first public cemetery in Newport News, covers more than 50 acres and contains over 43,000 burials in more than 20,000 plots. In the graveyard is a large obelisk that marks the mass grave of 163 Confederate prisoners of war, who died nearby at Camp Butler and were buried originally at West Farm, close to where the body of Harry Davie was discovered. Harry Davie is buried in the Old Single Section, in grave 3134. This is on the western side of the cemetery, 450ft due west of the commemorative obelisk. He is buried under a large maple tree alongside two Confederate veterans of the Civil War—John B. Nottingham and William H. Booker.[13]

The circumstances of his death explain the various dates reported in official records and in the newspapers in Devon when his disappearance and, later, his death were announced. His medal index card records his death as 23 November 1918, as does the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The news reports record, for example: ‘All Crediton and North Devon will regret to hear the sad news received yesterday of the death of Mr. H. Davie, M.R.C.V.S. As far as the meagre details received tell us, Mr. Davie was accidentally drowned some ten days ago while carrying out his duties in Montreal Canada’.[14] and, ‘It is with deep regret that we have to record the death of Mr. Harry W. Davie, M.R.C.V.S., of Crediton, who was accidentally drowned on Nov. 10th while carrying out military duties Montreal, Canada.’[15] The report of his death being in Montreal may be explained by a misinterpretation of a message from the headquarters there of the British Remount Commission. The probate record is a little more accurate and notes that probate was granted on 14 February 1916 to his widow, that he died at Newport Mews (sic) on 10 November 1915 and that he left an estate of £410 17s 7d.

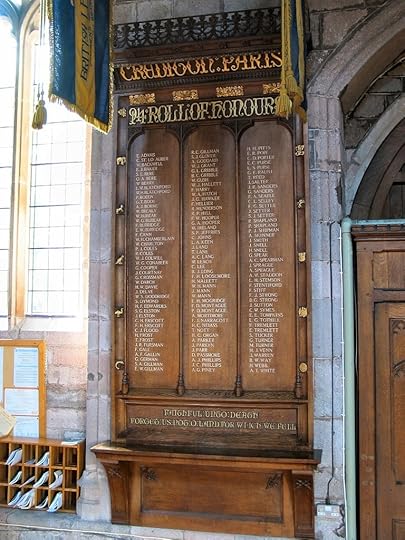

War Memorial in the Church of the Holy Cross, Crediton

In addition to the CWGC headstone on his grave in Newport News, Harry Davie is commemorated on the impressive wooden war memorial in the Church of the Holy Cross at Crediton. This memorial was designed by the church architect William Douglas Caroe, and dedicated in a ceremony immediately prior to the dedication of the town’s war memorial on 16 May 1923.

Crediton Town and Hamlets War Memorial

He is also commemorated on the south-east panel of Crediton Town and Hamlets war memorial. The memorial was designed by the architect Frederick Bligh-Bond and comprises an octagon of stone tablets contained within an oak-framed, open-sided, shingle-roofed shelter. It records 137 casualties from the First World War, 40 from the Second World War, and one from operations in Aden in 1965. It too was dedicated on 16 May 1923 and unveiled by Field Marshal Sir William Robertson Bt, GCB, GCMG, KCVO, DSO.[16]

It is noteworthy that his name has been omitted from the First World War memorial of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.

Later Family Tragedies

Harry Davie’s widow, Mary, died on 15 February 1946, aged 73, at The Green, Crediton, where she had lived throughout her life. She would witness two more terrible family tragedies.

Harry and Mary’s son, Thomas James Davie, was born on 25 November 1899. On leaving school he worked as a motor engineer and he enlisted into the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (Bristol Division, BZ/2159) on 13 June 1917, aged 17. He joined Royal Naval Shore Station HMS Victory VI (known as ‘HMS Crystal Palace’) on 10 September 1917 for training for Signal Duty but a few days later was not approved for that duty on ‘educational grounds’. He remained at HMS Victory VI until he moved to HMS Victory II (also at Crystal Palace) on 4 March 1918. On 21 April 1918 he joined HMS Excellent, at Portsmouth—the gunnery training school. He completed his training there on 19 July 1918 and he subsequently served as a gunner on a defensively armed merchant ship. He was promoted to Able Seaman on 10 December 1918 and demobilised on 13 May 1919.[17] After the war he joined the National Provincial Bank as a clerk and worked in the Thornbury branch in Gloucestershire. It was in June 1925 that his mother experienced a second great tragedy. Thomas Davie’s fiancé, Geraldine Esme Young, a maternity nurse, left Thornbury that month to attend the wife of the stationmaster at Woolaston. On Thursday 25 June Davie wrote to her and broke off their engagement. Regretting his decision, on Saturday 27 June he travelled to Woolaston on his motor bike to see her and pleaded to renew their engagement. The following morning they talked on the station platform and arranged to meet for a walk. When Miss Young returned having prepared for the walk Davie had disappeared. Just before midnight that night he was found dead in a wheat field behind the railway station. His throat had been cut seven or eight times with a razor, which was lying nearby. At the subsequent inquest the coroner recorded a verdict of ‘suicide whilst of unsound mind’.[18]

The third tragedy to befall her involved her nephew. William Abberley Copp was born in London in 1898. He attended Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, Crediton and, while there, lived with the Davie family. In the latter stages of the First World War, he served as a Second Lieutenant with The Devonshire Regiment and subsequently became an accountant with the National Provincial Bank. On 17 June 1937, aged 38, he committed suicide, by jumping in front of an underground train at Waterloo station. He left a wife, Marjorie (née Marjorie Evelyn Sharland), and a young son. At the subsequent inquest the coroner recorded that he too had committed ‘suicide whilst of unsound mind’.[19]

Harry and Mary’s daughter, Edith Annie ‘Nancy’ Davie, was born in the fourth quarter of 1900. On 3 June 1927 she married Sidney James Talbot Herbert at Crediton. The family subsequently settled in Kingston-on-Thames before returning to Devon. Nancy Herbert died at Exmouth on 20 September 1954 and Sidney Herbert died at Exmouth on 20 September 1956.

Acknowledgments:

Crediton Parish Church for the photograph of the church war memorial.

Donna Egan for the photograph of Crediton War Memorial.

Sources:

The War Office (WO). (March 1922). Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War. 1914-1920. London: HMSO.

Banks, C B. (1917). The Veterinarian’s Duties as ‘Conducting Officer’ in Trans-Oceanic Shipment of Horses. American Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Volume 12, 1917. pp 370-373.

Winton, G. (19 June 2013) Theirs Not To Reason Why: Horsing the British Army 1875-1925. Solihull: Helion and Company.

The archives of: Daily Press (Newport News), Western Times; The North Devon Journal; The Devon and Exeter Gazette; & Gloucester Journal.

1. (Back) ‘Proceedings of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and Veterinary Medical Services’. (1893). Veterinary Journal and Annals of Comparative Pathology, Volume 36. p 418. London: Baillière, Tindall & Cox.

2. (Back) Mary Elizabeth Copp was born in 1872 at Moortown, near Great Torrington. Their son, Thomas James Davie, was born on 25 November 1899 and their daughter, Edith Annie Davie, was born in 1900. Mary’s nephew, William Abberley Copp, was born in London in 1898 and is shown as living with them in both the 1901 and the 1911 census. Note that the 1911 census may be mis-transcribed as ‘Davis’.

3. (Back) In 1914 the establishment for remounts was 25,000 animals; by 1917 that had increased to 869,931 (See: The War Office (WO). (March 1922). Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War. 1914-1920. p 396.)

4. (Back) WO. Op. Cit. p 187.

5. (Back) The contract for United States veterinarians and a very detailed account of the role of a veterinarian conducting officer working for the British Remount Commission may be found at: Banks, C B. (1917). The Veterinarian’s Duties as “Conducting Officer” in Trans-Oceanic Shipment of Horses. American Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Volume 12, 1917. pp 370-373.

6. (Back) Major General Sir Frederick William Benson KCB. Born at St Catharines, Ontario in 1849 and educated at Upper Canada College, Toronto. He served with the 19th Battalion Volunteer Militia (Infantry) during the Fenian Raids in 1866 and subsequently attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He was commissioned into the 21st Regiment of Hussars in 1869 and served with the 12th (The Prince of Wales’s) Royal Regiment of Lancers from 1876. Appointed Aide-de-camp to the Lieutenant Governor, North West Frontier, India in 1877, he attended the Staff College in 1880. He then served with 5th (Princess Charlotte of Wales’s) Dragoon Guards) and 17th (The Duke of Cambridge’s Own) Lancers; was Brigade Major, Poona, India 1882-1884; Garrison Instructor, Bengal, India 1884-1890; Commander, Egyptian Cavalry 1892-1894; Deputy Assistant Adjutant General (Instruction) Dublin, Ireland 1895-1898; Assistant Adjutant General South Eastern District 1898-1900; Assistant Adjutant General 6th Division, South African Field Force 1900-1901; Mention in Despatches 16 April 1901; CB 19 April 1901; Inspector General of Remounts 1903-1904; Director of Transport and Remounts 1904-1907; and Major General in charge of Administration 1907-1909, when he retired. KCB 24 June 1910. He died in Montreal on 20 August 1916, aged 67 and was buried in St Catharine’s (Victoria Lawn) Cemetery.

7. (Back) WO Op. Cit. p 396 & p 861.

8. (Back) SS Victorian was a cattle-ship built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast in 1895 for F Leyland & Co. It was later operated by the White Star Line. It served as a horse transport during the South African War and in the First World War (renamed SS Russian) until it was sunk by UB-43 in the Mediterranean on 14 December 1916.

9. (Back) SS Orthia was a cattle-ship built for the Donaldson Line in 1896. It served as a horse transport during the First World War and was broken up in 1922 after a collision in the St Lawrence River.

10. (Back) ‘Veterinarian is Found Dead Near C.&O. Coal Pier’. (24 November 1915). Daily Press.

11. (Back) Library of Virginia. Commonwealth of Virginia Death Certificate, No. 27072. The death certificate incorrectly registers his name as ‘Dr Harry Davey’. The details of Harry Davie’s name, occupation and age were provided by Major R H Marsham, then the Staff Officer Embarkation, British Remount Commission, Newport News.

12. (Back) Brevet Lieutenant Colonel The Honourable Reginald Hastings Marsham OBE was born on 1865 the second son of Charles Marsham, 4th Earl of Romney. He was commissioned into the 4th Battalion (Militia), The Bedfordshire Regiment, on 10 April 1886 and appointed Second Lieutenant 7th (Queen’s Own) Hussars on 8 February 1888. In 1894 he was appointed Aide-de-Camp to Major General G Luck CB in India. He was promoted Captain on 14 April 1897. During the South African War he served as the head of the British Remount Commission in New Orleans. Promoted Major on 5 October 1904 and retired on 26 February 1908. He was recalled during the First World War and joined the Remount Service; he was posted to the British Remount Commission in 1915. On 29 March 1917 he was appointed to command a Remount Squadron and on 12 May 1919 he became a District Remount Officer. OBE 15 April 1919. When released from service he was appointed Brevet Lieutenant Colonel. He died on 8 November 1922, aged 56. His younger brother, Captain The Honourable Douglas Henry Marsham, was killed in action at Cannon Kopje during the the Siege of Mafeking on 31 October 1899, while serving with the British South Africa Police.

13. (Back) Sergeant John B. Nottingham enlisted at Williamsburg into Company F, 32nd Virginia Infantry Regiment (his grave records 39th Virginia Infantry Regiment) on 20 May 1861. He was captured at the battle at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865. Private William H. Booker enlisted into Company G, 1st Virginia Cavalry in 1861.

14. (Back) ‘Death of Mr. H. Davie, M.R.C.V.S.’ (30 November 1915). Western Times.

15. (Back) ‘Death of Mr. H. W. Davie, M.R.C.V.S.’ (2 December 1915). The North Devon Journal.

16. (Back) For a full account of both ceremonies see: ‘Crediton. War Memorial. Unveiling Ceremony.’ (17 May 1923). The Devon and Exeter Gazette. p 3.

17. (Back) Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Service Record.

18. (Back) ‘The Woolaston Tragedy’. (4 July 1925). Gloucester Journal.

19. (Back) ‘Bank Accountant Mourned’. (25 June 1937). Western Times.

October 14, 2014

My Family in the First World War

My great-grandfather William Neill was the influence behind my exploration of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers that led to Blacker’s Boys. Since writing the book I have discovered other relatives who served during the First World War. Each has a very different story:

14577 Sergeant William Neill DCM, Transport Sergeant, 9th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (County Armagh)/9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers).

4732 Sergeant Hamilton Neill, 2nd Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles. Wounded on 16 June 1915 at the Battle of Bellewaarde. He served as a regular soldier after the war with The Royal Ulster Rifles.

18/1141 Lance Corporal Robert Thompson, 15th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (North Belfast). Captured on 21 March 1918 at Racecourse Redoubt, St Quentin.

17/673 Private Thomas Bunting, 9th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (West Belfast). Killed in action on 1 July 1916 at Thiepval. He is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial.

In addition, my wife’s great-grandfather enlisted in Canada:

504226 Private John Palmer Bowes, enlisted for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission Commemorations in Virginia

Having discovered a single CWGC First World War commemoration in the Hampton Roads area where I live, I decided to investigate the other burials in Virginia and to write a short piece on each. Initial research has identified some very interesting aspects to almost all of these deaths.

In this series of essays I hope to add to the commemorations in this centenary period by remembering the 16 casualties of the First World War who are buried in Virginia:

Private Elmer Robert Darrock, Royal Marine Light Infantry serving on HM Yacht Warrior. He died on 19 October 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Surgeon Henry William Wilson Davie, Army Veterinary Corps. He died between 10 and 23 November 1915 and is buried in Newport News (Green Lawn) Cemetery.

Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class Harold Gurney Davis, Royal Naval Reserve serving on HM Yacht Warrior. He died on 16 September 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Cadet John Dunn, Royal Flying Corps. He died on 26 March 1918 and is buried in Petersburg (Blandford) Cemetery.

Captain Walter Frederick Fitch MC, The Suffolk Regiment, attached to the British Military Mission. He died on 1 November 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Deck Hand William Kelly, Mercantile Marine Reserve serving on HM Yacht Warrior. He died on 13 October 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Major The Hon Charles Henry Lyell Royal Garrison Artillery. Assistant Military Attaché, Washington DC. He died on 18 October 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Captain Angus Alexander Mackintosh, Royal Horse Guards, attached to the British Military Mission. He died on 13 October 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Private John Paul Mantell, Inns of Court Officer Training Corps. He died on 9 June 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Deck Hand Joseph Prowse, Mercantile Marine Reserve serving on HM Yacht Warrior. He died on 6 January 1919 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Private James Schofield Royal Marine Light Infantry serving on HM Yacht Warrior. He died on 23 December 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Lieutenant William Strong, Canadian Machine Gun Corps. He died on 21 December 1919 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Warrant Officer Class 2, Company Serjeant Major George Mayer Symons, The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) , attached to the British Military Mission. He died on 8 October 1918 and is buried in Petersburg (Poplar Grove) National Cemetery.

Writer 3rd Class Thomas Henry Symons, Royal Navy serving on HM Yacht Warrior. He died on 21 December 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Deck Hand Herbert Thomas, Mercantile Marine Reserve serving on HM Yacht Warrior. He died on 22 October 1918 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Private Charles Philip Gruchy, formerly 3rd Battalion (Toronto Regiment) Canadian Infantry. He died on 5 July 1921 and is buried in Richmond (Hollywood) Cemetery.

Commemoration

Szeregowiec (Private) Toni Paszkiewicz (right) with an unknown Polish starszy szeregowiec (Lance Corporal).

A story of wartime commemoration may seem an odd place to start the series of essays about the life of Toni Paszkiewicz, but it is timely, given that this year sees the 70th anniversary of the attack at Monte Cassino and the airborne attack at Arnhem, in both of which Polish troops played an important role.

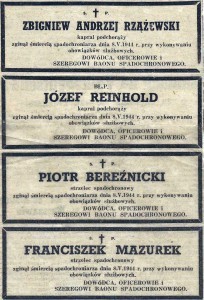

Less well known, the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade Group had suffered a number of deaths and injuries prior to the attack at Arnhem in September 1944. Among Toni’s papers is a newspaper cutting that commemorates four of his fellow soldiers who died preparing for an—then unknown—airborne attack in occupied Europe. This year is also the 70th anniversary of their death.[1]

Toni had joined the Polish Parachute Brigade when he arrived in Scotland from Iraq in June 1943 and had been posted to the 1st Polish Parachute Infantry Battalion. He would not take part in the attack at Arnhem, however—he was badly injured in May 1944.

Parachute accidents were relatively uncommon and the Poles had suffered only a handful of deaths after the first fatal accident on 16 June 1941, when Podporucznik (Second Lieutenant) Jan Twardawa[2] was killed at RAF Ringway, then the home of the Parachute Training Squadron of the Central Landing Establishment. But on 8 May 1944, when the Battalion was taking part in an exercise somewhere near Salisbury plain—the exact location is unknown—a serious accident occurred that resulted in the deaths of four men. It is believed that this was the exercise in which Toni was seriously injured also. He had lightened the load in his leg bag—the bag held the soldier’s field equipment and was lowered on a rope; it reduced the weight carried by the soldier on landing—and he had been blown away from the drop-zone. Toni landed badly in a ploughed field and suffered severe head injuries. He was in hospital for nearly a year and his injuries precluded further military service.

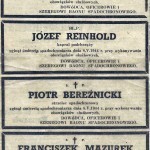

Newspaper Commemorations – May 1944

Among Toni’s papers is a newspaper cutting that commemorates three men who died on 8 May and one who died the following day. The yellowing paper was obviously important to him. Those killed were: Kapral Podchorazy (Corporals (Officer Cadets)) Jozef Reinhold, age 22; and Zbigniew Andrzej Rzazewski, age 24; and Szeregowiec (Privates) Piotr Bereznicki, age 20 and Franciszek Mazurek, age 26.[3] The four men were buried in Tidworth Military Cemetery.[4]

The newspaper commemorations recorded that the men ‘died the death of a parachutist on 8 May 1944 in the performance of official duties’. Each commemoration is signed: ‘commander, officers and men of the parachute battalion’.

While Toni lay injured in hospital the 1st Battalion continued its training and learned of its role in Operation MARKET GARDEN. The Polish Parachute Brigade came under British command in June 1944 and was ordered to move from Fife in Scotland to the area around Stamford in England. The 1st Battalion moved to the beautiful, limestone village of Easton-on-the-Hill on the edge of Northamptonshire. It was from here that it conducted its final preparations for the assault on ‘fortress Europe’.

Spring Close, Easton on the Hill

On 21 September elements of the 1st Battalion finally dropped at Driel, south of Arnhem—the remainder of the Battalion and the 3rd Battalion were not dropped due to the bad weather. On the edge of Easton-on-the-Hill, amongst the trees in a small park, known locally as Spring Close, is a small, unremarkable, stone pyramid. It is the memorial to those other friends and colleagues of Toni Paszkiewicz in the 1st Polish Parachute Infantry Battalion who died during Operation MARKET GARDEN.

I would like to hear from anyone who has more information about the accident on 8 May 1944.

1. (Back) The worst training accident to befall the Brigade occurred on 8 July 1944, when two C-47s of 309th Squadron, 315th Transport Carrier Group, United States 9th Air Force, touched wings shortly after takeoff from RAF Spanhoe. They were part of a parachute exercise involving 33 aircraft carrying 369 men of the 1st Polish First Independent Airborne Brigade, who were to drop at RAF Wittering. The two aircraft crashed close to the river Welland near Tinwell. Twenty-six Polish soldiers and eight United States Army Air Forces personnel were killed. There was only one survivor, United States Corporal Thomas W. Chambers was standing at the rear door of one of the aircraft and was forced out as the collision occurred. The Polish casualties are buried in Newark-upon-Trent Cemetery.

2. (Back) Podporucznik (Second Lieutenant) Jan Ernest Twardawa was undergoing training for operations in Poland. He is buried in the Second World War plot at Manchester Southern Cemetery and commemorated on the memorial to the 17 Polish casualties buried there. None are commemorated by individual headstones.

3. (Back) Bereznicki, Mazurek, and Rzazewski died on 8 May, and are recorded as serving with the 1st Battalion. Reinhold died on 9 May and is recorded as serving with the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. The newspaper cutting, however, records all four men as having died on 8 May 1944.

4. (Back) Section F, Polish Section, Graves 43 (Mazurek), 44 (Bereznicki), 49 (Rzazewski) & 50 (Reinhold).

5. (Back) Oosterbeek War Cemetery, Grave 34.A.9.

October 6, 2014

The Evolution of the Regular and Service Battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918 – Part 2, The 1st Battalion

This essay describes the evolution of the 1st Battalion. The background to this essay may be found here.

1st Battalion

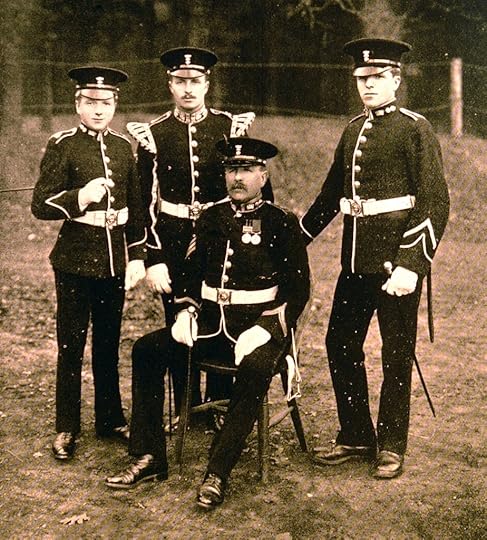

Pioneer Sergeant A L W Steele and his sons

When war broke out the 1st Battalion was stationed at Shorncliffe in Kent. The Army Reserve (those who had finished their period of regular service) had been mobilised by Royal Proclamation on 4 August 1914 and the men were ordered to report directly to the 1st Battalion or to the depot in Armagh.[1] The 1st Battalion was part of 10th Brigade, 4th Division, which had not deployed with the British Expeditionary Force in case of a German landing in Great Britain. It was dispatched in early August and the 1st Battalion landed in France on 23 August 1914.

The 1st Battalion subsequently suffered more casualties than any other battalion of the Regiment. It was sustained by drafts of Irish soldiers from the 3rd (Reserve) and 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalions until 1918. These were initially men of the Army Reserve and men of the Special Reserve—and some Cavalrymen transferred for infantry service—but increasingly from early 1915 the men who joined the 1st Battalion were wartime volunteers with a smattering of regular enlistments.

In August 1917 the 1st Battalion moved to 36th (Ulster) Division. The scale of the casualties suffered throughout late-1917 resulted in an influx of English soldiers to the Division and the 1st Battalion took its share, the first arriving in early 1918. These were men from the Army Service Corps and Army Ordnance Corps transferred for service as infantry, who joined in January and February 1918. Also in February 1918 the 1st Battalion absorbed 241 men from the disbanded 7th/8th (Service) Battalion, which included some men who had served previously in the 5th and 6th (Service) Battalions and in English regiments or in the support services.[2]

After the retreat from St Quentin in March 1918, which saw the near-destruction of the 1st Battalion, it received drafts of soldiers in early April from The London Regiment, most of whom were young conscripts new to France. It was this contingent of nearly 200 Londoners that fought at Wulverghem in April 1918, when the scale of the casualties reduced the Battalion to little more than a company and saw it attached to the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion.

The subsequent reconstitution of the 1st Battalion began with a draft of 32 men from The Prince of Wales’s Volunteers (South Lancashire Regiment), who joined on 1 May 1918, and a mixed batch of 75 men of The Hampshire Regiment and Prince Albert’s (Somerset Light Infantry). It also received a series of drafts totaling 229 men transferred from The Royal Irish Rifles and The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. Many of these men had previously been transferred from English regiments (including a draft of 65 men from The London Regiment transferred to the Royal Irish Rifles) but who had not been posted to their battalions before being reallocated to Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers); a majority of them were recovered wounded and sick men who had seen previous service in France and Flanders.

Such was the make-up of the 1st Battalion until 22 September 1918 when a draft of 132 men joined; they had been transferred from The Royal Irish Rifles and were soldiers of various backgrounds, including men from English regiments and men from the Army Service Corps who had been transferred previously to The Royal Irish Rifles.

Details on each of these drafts may be found here: Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918 – Reinforcement Drafts

1. (Back) This and related proclamations may be seen on The Long Long Trail.

2. (Back) The War Diary of the 7th/8th (Service) Battalion records 240 men posted to the 1st Battalion. The War Diary of the 1st Battalion records receiving 241 men.

September 18, 2014

Flanders Field American Cemetery and an American with 36th (Ulster) Division

This post is republished to include archive material and photographs that I have rediscovered, some new information and a new image that I received as a result of the original post.

The visit by President Obama to Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial at Waregem in Belgium in March 2014 brought back memories of my own visit there a few years ago. The site of the cemetery is near where the US 91st Division attacked and captured the wooded area of Spitaals Bosschen. It is beautiful and it has a very different ‘feel’ to Commonwealth cemeteries. Well-spaced rows of white crosses surround the chapel, which stands in the centre of the six acre site. Inside the chapel, the altar and walls are marble and the furniture is of carved oak, stained to reflect the black altar. On either side are the Walls of the Missing, inscribed with the names of the 43 men who fell in Flanders and ‘who sleep in unknown graves’. Bodies of some of these men have been recovered since and identified; those names are marked with a rosette.[1]

Flanders Field Memorial Chapel

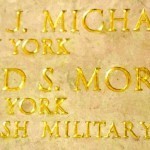

I was working on Blacker’s Boys, the history of the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Princes Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), and, after months of research, I had identified that one of the Battalion’s officers was commemorated in the memorial chapel. The man I was looking for—Lieutenant Harold Sydney (Syd) Morgan, United States Army Medical Reserve Corps—was killed in action on 12 April 1918.

Syd Morgan came from Welsh and English stock. His father, Davy, was a miner born in Pontypridd, Glamorganshire on 3 March 1851 and his mother, Ellen Matilda ‘Nellie’ Shafer, was born on 20 October that year in London. They married in Pontypridd in 1873. Their first child, Davy Shafer Morgan, was born in the second quarter of 1877 in Pontypridd and, on 20 December, the family emigrated to the United States from Liverpool. They settled in Winton, Pennsylvania, where Davy naturally found work as a miner, and he and Nellie had five more children (other children were born but did not survive)—Mabel Florence (26 June 1879), Jeannette Catherine (30 July 1882), (Paul) Victor (5 April 1885), Gwladys M (14 July 1888), and Harold Sydney ‘Syd’, the youngest, born on 2 May 1890.

The Morgan Family

In 1901, Nellie died and the family uprooted and moved to Coronado, California, where Syd Morgan was raised by his older sisters.[2] He graduated from high school in San Diego in 1908 and went on to Stanford University (Phi Delta Theta), where he graduated in 1912. In 1911 his father had died and that year he began his medical studies at Stanford. In the summer of 1914, he served as an assistant on the Hospital Ship Strathcona, which provided medical care at the remote communities in Labrador and northern Newfoundland. His medical studies were completed at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, from which he graduated as a doctor in 1915. Syd Morgan joined the house staff at Bellevue Hospital, New York on 1 January 1916. In the memorial book subsequently compiled by Bellevue Hospital, Syd Morgan was described as …a great addition to any circle; he possessed a buoyancy of spirits and an equanimity of temper that altogether fitted him for the company he was now in. Moreover he was large, of athletic build, capable of much endurance. He was a great tennis player—supreme on the courts at Bellevue and tennis champion at Johns Hopkins, Stanford and at high school.[3]

Lieutenant Harold Sydney Morgan, United States Army Medical Reserve Corps

The United States entered the war on 6 April 1917 and Syd Morgan was commissioned into the United States Army Medical Reserve Corps as a Lieutenant on 9 August. He sailed from New York on the SS Cedric—a former White Star liner, built at Harland & Wolff in Belfast—on 3 October 1917, and reported for duty at American Base Hospital No. 2 (Presbyterian Hospital, New York City) at Etretat on 17 October. This base hospital had taken over the roll of No. 1 General Hospital and supported the British Expeditionary Force for the remainder of the war. In November 1917 Syd Morgan was posted with two other Army Medical Reserve Corps doctors to 36th (Ulster) Division.[4]

Their departure and early time with the Ulster Division is documented in Cheerio!,[5] the memoir of Major Harold M. Hays—which he dedicated to Syd Morgan. Hays served with 110th Field Ambulance and, for a short time in February 1918, as the medical officer of 2nd Royal Irish Rifles. He was then posted to No 1 General Hospital at Etretat on 25 February 1918 and subsequently to the American Expeditionary Force base hospital at Hyères in southern France.

Harold Hays, at the time a captain, Syd Morgan and 1st Lieutenant Cook[6] joined the Ulster Division just as its involvement in the Battle of Cambrai was drawing to a close. Hays and Morgan joined 110th Field Ambulance on 25 November 1917, and Cook joined 108th Field Ambulance the same day. Having had their first experience of treating battlefield casualties, Hays and Morgan moved to the rear with 110th Field Ambulance when the Ulster Division was withdrawn from the attack on 26/27 November. Their relief was short-lived, however, and they were rushed forward again as the German army counter-attacked. 36th (Ulster) Division came under command III Corps on 3 December and the next day Syd Morgan was detached to 16th Field Ambulance in 6th Division, where he worked assisting another medical officer in a dugout for 48 hours. By 15/16 December 36th (Ulster) Division was exhausted and its units, including 110th Field Ambulance, were withdrawn from the line.

In late January 1918, Syd Morgan joined the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers in 108th Brigade as the battalion medical officer. 36th (Ulster) Division was now holding the defensive zones south-west of St Quentin. On 19 March, in his last letter to Harold Hays, he wrote:

Ah—your Majority has arrived at last. I was mighty glad to hear of it, for certainly you should have had it long ago. Dave told me in a recent letter that you had withdrawn from the 2-bar class. Knowing that you were spending leave in Cannes, the enclosed clipping from the Mail caught my eye, and I was interested to see your name, together with those of Stevens and Cassamajor. I’m sure you’re having one wonderful bit of sport down there, and I must admit I’d much like to be in the crowd. Dave and Art and I expected to put in a week or so of leave there. Cannes is a regular Monte Carlo, they say.

As it happens, I am still with the worthy 9th, in reserve right now at Grand Seracourt (sic). Our tours in the line have been simple enough lately and casualties rare. It has been good sport, however, for the weather recently has been absolutely perfect, giving wonderful observation. I’ve seen plenty of Boche and have missed his machine-gun bullets successfully. One night the C.O. and I went all around the line about twelve o’clock, going out into the saps and wandering about in No-man’s Land. Incidentally a machine-gun turned near us and d___ near cut the grass between our legs. The Boche is quiet these days, however, and he hardly replies at all to the rather heavy strafing he gets night and day. One thing certain now is our guns are not afraid to speak. The best sight I have seen recently was watching the tremendous shell of a 12-inch howitzer flying off into space. It is very remarkable how one can see the shell for fully a minute or two from the moment it leaves the muzzle until it goes out of view.

I hope I may see you before long as I have applied for leave, going to England by way of Havre, stopping a day in Etretat if I can arrange it O.K. I’d much like to see these poor unlucky devils who had to stay around the Base while we were having the only real sport in the war—at the front. You and I certainly had it on the rest of the crowd. I applied for leave yesterday, and if it goes through all right I expect to be in Etretat in a couple of days. I surely hope so. My very best to you.[7]

The ‘Boche’ were not quiet for much longer. On 21 March 1918 the first attack of the German spring offensive—the Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle)—swept all before it and 36th (Ulster) Division fought a withdrawal action over a period of seven days from St Quentin to Erches. In this most heroic series of actions, the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers suffered 522 officers and men killed, wounded and captured. For his gallantry during this period Syd Morgan was awarded the Military Cross—one of 173 such awards to medical officers from the United States.[8] His citation stated:[9]

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during the retirement from Grand Seraucourt on the morning of March 22nd. This officer was retiring behind the rearguard, and on approaching Artemps was told that some wounded were still lying in Grand Seraucourt. Although he knew that the enemy was already on the outskirts of the village he returned at once with some stretcher bearers and succeeded in bringing out the wounded. He thus at the commencement of the operations set a splendid example to his stretcher bearers of devotion and courage.

He would not know of his award, which was not published until later in 1918.

Having been withdrawn from the line on the night of 27 March, the Ulster Division was moved north to Ypres, where it spent the first week of April refitting and absorbing reinforcements. Syd Morgan wrote home on 3 April to his friend, Margaret Sanborn:[10]

Possibly at the present time in far away California you are reading all about the great German offensive on the western front and maybe wondering about what part I saw of it all and where I have been pushed about in that time. Well, Margaret, it certainly has been an active time and frankly enough, I’ve seen a bit of warfare and looking back upon the last couple weeks, I would take nothing for the experiences I’ve had. As it happened, my battalion was well in the center of things at the start and remained so for some time. To think of it now, it is sort of a blurred dream and so many things have taken place. It was a wild adventure sure enough and a fact that for five days I had no opportunity to sleep more than about four hours in all, it shows that there was plenty going on. Some quite funny things took place and when I think of it, I indeed am absolutely lucky I’m not residing in Germany today. Karlsruhe escaped the privilege. Warfare during this period had become quite open in nature, not like the old trench fighting, and certainly my place gave me full opportunity to be a first hand eye witness. I can’t say too much as to what actually happened but there was plenty. I assure you we are now away from the war and one could not tell a war was going on anywhere by the quiet life in this little French cottage. Our three days have been a luxury and to sit down once again to a table to have good meals and to sleep full nights in a curtain bed have been the keenest joy possible. I saw a lot of American doctors yesterday and quite a few US nurses, the first American girls I have seen since November. That doesn’t sound like much. It was a big treat after seeing nothing but French and for the most of the time nothing but British soldiers. We are leaving this village again tonight for somewhere else in France. Wherever that may be, I can’t tell you.

I hope you are well, Margaret, and that the family and all are very happy and enjoying life a much as I. I am indeed having a splendid time of it always and have no regrets whatever.

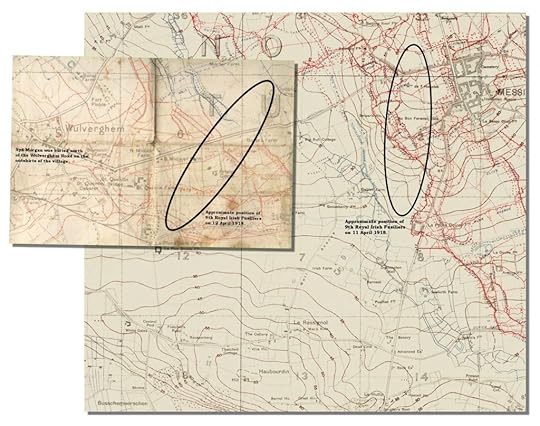

While most of the Division was concentrated to the north of the ruined town, 108th Brigade was detached to 19th (Western) Division to act as the reserve for II Corps and on 10 April it took up a position south-west of Ypres. Here the remnants of 108th Brigade would meet the second phase of the German offensive—Operation Georgette. The 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers were deployed into the line at the Kemmel defences at Lindenhoek Corner, just east of the hill on the Kemmel-Neuve Eglise Road. There was no time to settle here due to the pressure on the line from the renewed German offensive and 108th Brigade was hurried farther forward. By 7.00am on 11 April 108th Brigade was in position on the Wulverghem-Messines Road (see map). 12th Royal Irish Rifles had deployed onto the Wulverghem-Spanbroekmolen Ridge with 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers to the north of the Wulverghem-Messines Road and on the right of the South African Brigade (actually little more than a South African battalion reinforced with a battalion from each of 108th Brigade and 56th Brigade). The 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers was in support farther south between the road and the River Douve, and the 9th‘s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Philip Kelly, took command of this sub-sector from the battalion headquarters in Stinking Farm.

Both Irish Fusilier battalions suffered intensive shelling throughout that night; it was particularly heavy on the ridge itself. At 3.30pm the enemy attacked in strength. The fighting was fierce and the men in the forward trenches were pressed back but a spirited counter-attack by the 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers and the South Africans restored the line. That evening the bombardment began again. The troops on the left of the South Africans were pushed back and Hill 63 to the south was captured, opening the flanks of 108th Brigade to heavy machine-gun fire. The situation was grave and, to avoid losing more men, 108th Brigade was pulled back and the front pivoted around 9th Division, which was firm in Wytschaete in the north of the sector. 12th Royal Irish Rifles remained on the Wulverghem/Spanbroekmolen Ridge and 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers moved back towards Wulverghem with the much depleted 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers farther to the rear in support.

At 6.40pm on 12 April, as dusk fell on another day spent under heavy shellfire, the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers were attacked from La Petite Douve Farm, where they had seen the enemy massing. The fierce German assault drove in the left flank but the Commanding Officer ordered an immediate counter-attack by the reserve company. Lieutenant Hamilton and the men of B Company rose from their trenches and attacked with a small party from 12th Royal Irish Rifles. The enemy were sweeping the road with machine-gun fire and there was a number of casualties immediately.

9th Royal Irish Fusiliers dispositions 11 & 12 April 1918

It was during the fighting on the afternoon of 12 April that Syd Morgan was killed. He was tending to the wounded with two stretcher-bearers when he was hit on the leg. As he was being placed on a stretcher he was killed by an exploding shell, which also injured one of the men with him. He was buried nearby, north of the Wulvergham-Messines Road, on the outskirts of Wulverghem.

Sometime after his death, his sisters received a letter from an officer in the Battalion who wrote of his death and provided a rough sketch map that showed where he had been buried. On 30 January 1922, Gwladys and Jeanette applied for their passports, specifically stating on the applications that they were travelling to Belgium to find their brother’s grave. They travelled to Southampton from New York as 2nd Class passengers on board RMS Mauretania, arriving on 24 July 1922. Their search proved fruitless—the area of his burial had been searched and the battlefield graves cleared in late-1919. It is not known if they visited Flanders Field American Cemetery. The sisters returned to the United States on 27 January 1923 on the RMS Berengaria.

There is some evidence to indicate that Syd Morgan’s body may have been exhumed and taken to Flanders Field American Cemetery during the period of cemetery concentration after the war, but positive identification proved impossible. Inexplicably, of the 39 men of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers killed in action on 11 and 12 April 1918, only one lies in a marked grave; 37 are commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial and Syd Morgan is commemorated in the Flanders Field Memorial Chapel. He is also commemorated on the City of San Diego and San Diego County Memorial Roll.

Acknowledgments:

Patty Mackey & Patrick Lernout for the photographs of Syd Morgan and the information about his family.

Daniel Mansdoerfer for the photograph of the Presidential Certificate.

Sources:

Burrows, A R. (1925). The 1st Battalion The Faugh-a-Ballaghs in the Great War. Aldershot: Gale & Polden.

Carlisle, R J. (1922). A Seven Years’ Record of The Society of Alumni of Bellevue Hospital 1915 to 1921. New York: The Society of Alumni of Bellevue Hospital.

Hays, H M. (1919). Cheerio! New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Metcalfe, N P. (2012) Blacker’s Boys. Timberland: N P Metcalfe.

Rauer, M. (Ed Sanders, M). Yanks In The King’s Forces: American Physicians Serving With The British Expeditionary Force During World War 1. p . U.S. Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History.

War Department. (1923). Annual Report Of The Secretary Of War To The President War Department Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1923. pp 162-174. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage

1. (Back) The names of the missing are listed here.

2. (Back) Davy junior became an electrical engineer and, like their brother, Gwladys and Mabel became doctors (osteopaths)—Gwladys also wrote children’s books and was a suffragette; Mabel became the President of the Business and Professional Women’s Club in San Diego. Jeanette was a librarian; she was the Chief Librarian for the San Diego City Schools. Victor began to study to become an engineer but became a banker.

3. (Back) Carlisle, R J. (1922). A Seven Years’ Record of The Society of Alumni of Bellevue Hospital 1915 to 1921. New York: The Society of Alumni of Bellevue Hospital.

4. (Back) This was a common practice; in response to a request from the United Kingdom for additional medical personnel and in order to provide the greatest experience to the medical officers of the American Expeditionary Force they were attached to British and Commonwealth hospitals and field ambulances, and as unit medical officers. The first American unit to arrive in France, in May 1917, was a base hospital and the first American casualty, in July 1917, was a medical officer. Yanks In The King’s Forces is worth reading and contains excellent photographs.

5. (Back) Hays, H M. (1919). Cheerio! New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

6. (Back) I have not been able to identify this officer. Any assistance in doing so would be appreciated.

7. (Back) Hays. Op. Cit.

8. (Back) Rauer, M. (Ed Sanders, M). Yanks In The King’s Forces: American Physicians Serving With The British Expeditionary Force During World War 1. p . U.S. Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History. A total of 323 awards of the Military Cross were made to personnel from the Unites States—see: War Department. (1923). Annual Report Of The Secretary Of War To The President War Department Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1923. pp 162-174. Washington: Government Printing Office.

9. (Back) Carlisle. Op. Cit.

10. (Back) Margaret Sanborn was born at Redlands, California on 18 February 1891, the daughter of a doctor. Her brother, Tom, was a friend of Syd Morgan’s, with whom he attended Stanford University. Margaret is believed to have been Syd’s ‘sweetheart’. Margaret Sanborn married Harvey Elgin Hall in 1945. She died on 3 February 1965.

September 4, 2014

My Family in the First World War – Part 1 William Neill

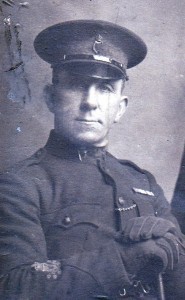

14577 Sergeant William Neill DCM

Sergeant William Neill DCM

It was the stories about my great-grandfather, William Neill, that led me to write Blacker’s Boys. I had been told that he had earned a Distinguished Conduct Medal at Ypres and I embarked on an attempt to separate family myth from fact. I have largely succeeded, with one exception—William Neill believed that he had been awarded a Bar to his Distinguished Conduct Medal but no record of that exists. During his post-war service with the Ulster Special Constabulary he wore a rosette on his ribbon bar, his obituary and his gravestone both state that he had a Bar, and my father’s memory of him was that his Bar was a source of great family pride. It is evident, however, that this second award was never made. Nevertheless, it must have been commonly agreed that he was entitled to it. He served in the USC alongside other former officers and soldiers of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers and it is hard to believe that a man of his considerable good reputation decided to award it to himself. How he came to believe that he had been awarded that Bar is now lost to history.

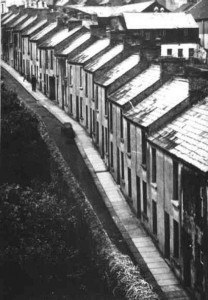

Taylor’s Court, Lurgan

William Neill was born on 1 June 1876 at Tullyherron, a townland in Donaghcloney parish near Waringstown.[1] He left school at 14 and began work with his father and siblings in a local mill.[2] The mills were the biggest employer in Lurgan; you can read more about linen in Northern Ireland here and about Lurgan here. On 27 August 1897, he married Emily Matthews, of Anne Street, Lurgan, at Shankill Parish Church.[3] They lived at Taylor’s Court. In the census of 1901 he described himself as a ‘yardhand’—for a period around this time he worked at the Lurgan Gas Light & Chemical Company at William Street. In 1911 he left Lurgan Gas Light—according to a letter of reference ‘to take a better job’—and went back to work in one of the town’s linen mills as a damask weaver, a highly skilled worker in this huge and important industry. In 1911 he, Emily, and their four young daughters were living at 28 James Street.[4] He and Emily would have one more child in 1913 and adopt another in 1922.

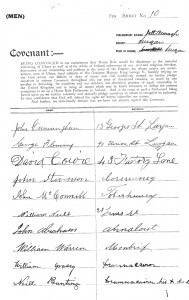

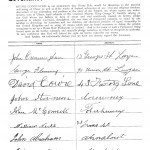

The political issue of the day was Home Rule—self-government exercised by an Irish Parliament in Dublin. There was considerable opposition in the northern, and largely Protestant, province of Ulster to any measure that would see an end to the Union and a shift in the balance of power and economic priorities away from Belfast. The signing of the Solemn League and Covenant, a pledge to ‘defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland’, was to become the focus of public opposition to the Home Rule Bill and 28 September was to be ‘Ulster Day’, when the Covenant would be signed across the province.[5]

Ulster Covenant signed by William Neill

When the day came 237,368 men put their names to the Covenant, and 234,046 women signed the accompanying Declaration. Among them were the men and women of the Neill family, including William Neill, who signed at Lurgan Town Hall and Emily, who, with a number of other ladies from James Street, signed at Shankill Parochial Hall.[6]

William Neil also joined the Ulster Volunteer Force. Moves to arm a Unionist militia had begun as early as 1910 and by January 1913 the Ulster Unionist Council decided that the volunteers for such activities should be united into one body known as the Ulster Volunteer Force. The organisation of the force progressed quickly. Ulster was divided into fourteen divisions: the nine counties, Londonderry, and the four parliamentary constituencies of Belfast. Each of these was organised into a number of regiments and battalions—County Armagh, central to this story, raised five battalions. In addition to these, supporting units were formed to provide communications, transport, and medical facilities. Two units of light cavalry were raised—the Ballymena and Enniskillen Horse. William Neill joined ‘B’ Platoon in the 5th (Lurgan) Battalion.

The Home Rule Bill was passed on 25 May 1914. Fortunately, the day passed peacefully, as did the following 12 July when the Orange Order held its annual parades. But all was not well. Ireland was tense, and the men of the Ulster Volunteers paraded openly over the north of Ireland. Guns were landed for the Irish Volunteers—the nationalist counter to the Ulster Volunteer Force—on 26 July and the shooting of Irish nationalists by the British Army in Dublin that day inflamed the population. To many, war in Ireland seemed certain. Only the outbreak of war in Europe saved the situation.

It was evident that the Ulster Volunteer Force had the potential to become a formidable fighting force. After some discussion with Kitchener, Sir Edward Carson promised a division and on 3 September, at a meeting of the Ulster Unionist Council in Belfast, in a long and emotive speech Carson appealed to the men of the Ulster Volunteer Force: “Go and help to save your country and to save your Empire; go and win honour for Ulster and for Ireland.” For those members of the Ulster Volunteer Force responding to Carson’s call in Lurgan, recruiting began on 15 September. The official recruiting age was between nineteen and thirty-five (raised from thirty in late August) and William Neill, at thirty-seven years old, was over age. He was among the first to volunteer, however, and was duly attested.

Clandeboye Camp 1914

He enlisted into Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) and on Monday 21 September travelled with his friends and colleagues to Clandeboye near Newtownards, where the 2nd Brigade of the new Ulster Division was to be based (see the newspaper article in the photo gallery below). It was at Clandeboye that he was given the regimental number 14577. On 2 October, the County Armagh battalion was named the 9th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (County Armagh).[7] His service follows that of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, with which he served for the duration of the war. He landed in France on 4 October 1915, initially as a Corporal in ‘C’ Company. Prior to the attack at Hamel on 1 July 1916 he joined the Battalion Transport and he became the Transport Sergeant on 24 August 1916. He served as the Transport Sergeant for the rest of the war—during the period holding the line at Messines from the autumn of 1916 through to the attack there in June 1917; at the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August 1916, when the Battalion Transport Officer, Lieutenant James Stronge, was killed; at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917; during the retreat from St Quentin in March 1918 and during the next phase of the German offensive at Ypres in April 1918; and in the Advance to Victory.

Lieutenant James Matthew Stronge

The death of James Stronge was a notable episode in William Neill’s life, an episode which would be talked about in the family for years to come. James Matthew Stronge was born on 10 January 1891 at Tynan Abbey, County Armagh, the son and heir of the 5th Baronet, Sir James Stronge. His family were staunch Unionists and Stronge was a member of the Ulster Volunteer Force. He enlisted into the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers on 14 September 1914 and was commissioned on 12 October. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 1 May 1915 and he served as the Battalion’s Transport Officer until he was killed in action at the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August 1917, aged 26. At the time of his death he had been married for a little over one month.

It is not known precisely where and when he was mortally wounded or killed but it was almost certainly on the route from Wieltje to the Battalion’s position, along Roeselarestraat, an old clinker brick road that was now a muddy, shell-torn lane, laid in part with corduroy track. It is known that Sergeant Neill called for volunteers to help him find Lieutenant Stronge—it may be surmised that he was actually present when he was mortally wounded or that knew that he had been badly wounded somewhere on the route to the Battalion’s forward position at Pommern Redoubt. It is not known whether he was dead when he was found but his body was brought to the rear by William Neill and four men. He was buried in Brandhoek New Military Cemetery Number 3. William Neill subsequently wrote to the Stronge family and described the events of that day, their son’s death and where he had been buried. In thanks, the family wrote back, sent him a silver framed photograph of James Stronge and invited him to visit. After the war William Neill visited Tynan Abbey on a number of occasions, at least once with my father.[8]

Sergeant William Neill was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in June 1918.[9] His citation does not indicate a specific act of gallantry:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He has been with the battalion since its formation, and has rendered very valuable service as transport sergeant. His unfailing cheerfulness, coolness under fire and zealousness have been most marked.

The Battalion’s final actions involved the crossing of the Lys in October 1918 and its final day in action was 26 October. When the war ended the Battalion moved to Mouscron, where it remained until it was disbanded in June 1919. William Neill left Belgium in January 1919 for demobilisation and was at home in time to attend the ‘Welcome Home Banquet’ for the held at Portadown Town Hall on 30 January, at which the guests of honour were the prisoners of war repatriated in November and December 1918. He was transferred to the Class Z Reserve on 16 March 1919. In addition to the Distinguished Conduct Medal, he was awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal 1914-20 and the Victory Medal.

Sergeant William Neill DCM at the dedication of the Ulster Battlefield Memorial Tower, 21 November 1921.

When the Ulster Battlefield Memorial Tower was opened and dedicated on Saturday 19 November 1921, Sergeant William Neill DCM planted the tree on behalf of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers.[10] It is not often that one can identify relatives in news reels from this period, but this clip from British Pathé of the dedication of the Ulster Battlefield Memorial Tower, shows William Neill DCM in the final few seconds.

As if those who had suffered on the Western front had not had enough to contend with, they returned to Ireland at the dawn of a new era in Irish politics and conflict. Voting in the 1918 general election began on 14 December and the result was a shock to many. Sinn Féin candidates were elected in seventy-three constituencies. The Irish Unionist Party secured twenty-two seats, largely limited to Ulster, and the Irish Parliamentary Party won only six seats. After the election the Sinn Féin MPs chose to boycott the Westminster Parliament and formed the revolutionary parliament—Dáil Éireann. On the same day two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary guarding quarry explosives were ambushed and killed at Soloheadbeg in Tipperary by members of the Irish Volunteers. Thus began the Anglo-Irish War that would ultimately result in the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922 and the partition of Ireland.

The response by Unionists to the attacks of the Irish Republican Army in 1920 and 1921 was to form local militias across Ulster, based loosely on the pre-war Ulster Volunteer Force and manned by many former soldiers. In an effort to regulate these and to bolster the efforts of the police, the government agreed to the creation of the Ulster Special Constabulary as a reserve element of the Royal Irish Constabulary. This was achieved using existing legislation—the Special Constables (Ireland) Act, 1832. The Ulster Special Constabulary was divided into several categories, the most well known of which was the part-time ”B’ Specials’. There was also, however, a uniformed, regular cadre, the ‘A’ category. About half of the ”A’ Specials’ were assigned to duty in police barracks and acted as uniformed police, with the other half being formed into motorized platoons.

Head Constable William Neill DCM

Among those who joined the ‘A’ Specials was William Neill, who joined on 16 May 1922. He was allocated the number 7295 and was initially appointed as a platoon Sergeant. He was promoted to Head Constable at the end of the year and served in that capacity with 39th Platoon in Armagh. The ‘A’ and ‘C’ Specials (the latter were a non-uniformed reserve) were disbanded in March 1926 and on 17 April 1926, William Neill left the Ulster Special Constabulary. This was a difficult time but he found work with Lurgan Urban Council as a road construction foreman and his references from the officers of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers and the Ulster Special Constabulary are testament to his reputation.

At some time in this period the family moved to 40 Gilford Road, Lurgan and William Neill embraced the Elim Pentecostal Church; he became a lay-preacher. On Sunday 20 February 1955, as the family were waiting for a bus to take them to church, he felt unwell and decided not to go with them. He died at 9.30pm that night from a heart attack. He was 78 years old. He was buried at Lurgan New Cemetery on 23 February 1955.

Many of the images in the gallery include more detailed information. Thanks are due to my cousin, Gillian, for the images of William Neill’s medals and badges, the newspaper extracts and the photographs of him and his wife in later life.

","created_timestamp":"1312977226","copyright":"COPYRIGHT, 2009","focal_length":"10.1","iso":"100","shutter_speed":"0.016666666666667","title":"

","created_timestamp":"1312977226","copyright":"COPYRIGHT, 2009","focal_length":"10.1","iso":"100","shutter_speed":"0.016666666666667","title":"1. (Back) He was the sixth of the seven children of Gilbert Neill (born 1837), my great-great-grandfather, and Ellen Thompson (born 1833), who were married on 2 September 1864 in Magheralin Parish Church (The Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, Magheralin). The other children were: Annie (born 1863), Thomas George (born 3 November 1865), Joseph (born 28 October 1867), Elizabeth Jane (born 21 August 1870), Moses (born 28 April 1873), and Hamilton (born 5 September 1884). William Neill was my father’s maternal grandfather.

2. (Back) Almost every member of my family in the generations up to my mother’s and father’s worked in the linen mills. On my father’s side they worked in the Lurgan area and on my mother’s side they worked in the mills in Hydepark, Mallusk in County Antrim.

3. (Back) The Church of Christ the Redeemer, Lurgan. This is the largest, non-cathedral Church of Ireland church in Ireland.

4. (Back) Elizabeth (known as Cissie) (born 12 August 1900), Olive (born 28 September 1902), Annie, my grandmother, (born 26 November 1907) and Marie (known as Miriam) (born 16 August 1910). A fifth child, Joseph (known as Joey), had been born on 22 September 1898 but had died on 20 March 1901. They would have one more child, May (Mary) (born 30 July 1913) and adopt another, Teddy (born 18 December 1922).

5. (Back) The Covenant was largely the work of James Craig MP, and was based on the Scottish Covenant of 1580/1581 and its successor covenants. Men signed the Covenant while women signed the accompanying Declaration.

The Covenant.

Being convinced in our consciousness that Home Rule would be disastrous to the material well-being of Ulster as well as of the whole of Ireland, subversive of our civil and religious freedom, destructive of our citizenship and perilous to the unity of the Empire; we, whose names are underwritten, men of Ulster, loyal subjects of His Gracious Majesty King George V, humbly relying on the God who our fathers in days of stress and trial confidently trusted, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn covenant throughout this our time of threatened calamity to stand by one another in defending for ourselves and our children our cherished position of equal citizenship in the United Kingdom and in using all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland. And in the event of such a Parliament being forced upon us we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority. In such confidence that God will defend the right we hereto subscribe our names. And further, we individually declare that we have not already signed this Covenant.

The Declaration.

We, whose names are underwritten, women of Ulster, and loyal subjects of our gracious King, being firmly persuaded that Home Rule would be disastrous to our Country, desire to associate ourselves with the men of Ulster in their uncompromising opposition to the Home Rule Bill now before Parliament, whereby it is proposed to drive Ulster out of her cherished place in the Constitution of the United Kingdom, and to place her under the domination and control of a Parliament in Ireland. Praying that from this calamity God will save Ireland, we hereto subscribe our names.

6. (Back) The signatories of the Ulster Covenant may be found on the PRONI website.

7. (Back) When the battalions of 36th (Ulster) Division were named the County Armagh Battalion in 2nd Brigade was initially titled: 9th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (County Armagh Volunteers). The suffix ‘…Volunteers’ was used for all of the battalions of the Ulster Division. The use of this suffix appeared once in the London Gazette—on 27 October 1914; the Gazette that appointed the first officers to the battalions of the Division—and never in the Army List. By November 1914 the word ‘Volunteers’ had been dropped from all of the battalion titles.