Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 11

June 12, 2015

Sacrifice – Latest Post – Cadet Arthur William Webster Eden

Cadet Arthur William Webster Eden

The latest addition to the Sacrifice project is the story of Cadet Arthur William Webster Eden who was killed in an aircraft crash at Camp Taliaferro, Texas on 21 December 1917. His body was returned home and buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, Baltimore.

May 31, 2015

Sacrifice – Latest Post – Leading Seaman Joseph Thompson Clark

The latest addition to the Sacrifice project is the story of Leading Seaman Joseph Thompson Clark, a gunner on the defensively armed merchant ship SS Courtown. Clark was nearby when HMS Natal blew up in Cromarty Firth in 1915, was present at the Battle of Jutland, and survived being torpedoed in the Mediterranean only to drown in a swimming accident in Baltimore harbour in 1917.

Read about Leading Seaman Joseph Thompson Clark.

Port Covington, Western Maryland Railroad Yards

The Loss of a Ship

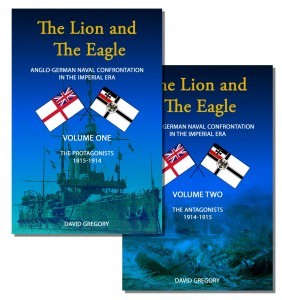

On the 99th anniversary of the Battle of Jutland, the largest naval battle of the First World War, it is appropriate that my first guest post is by David Gregory, the author of the maritime trilogy ‘The Lion and The Eagle’. He has written a thought-provoking and heartfelt piece about the devastation wrought by the total destruction of a capital ship. This essay gives meaning to that simple and inadequate phrase ‘lost with all hands’.

The battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary

The bald accounts of battles cover events and statistics. Personal memoirs describe individual experiences. The death of a ship, involving, as it does, an entire community, is difficult to chronicle when there are often few, or even no, witnesses to its demise.

There is something uniquely devastating about the destruction of any ship, great or small. If it is fortunate enough to sink as the result of a gradual accumulation of damage, there remains the prospect that a reasonable proportion of those who have survived the enemy’s bombardment may eventually be rescued. Even in this circumstance, however, the seriously wounded have little chance of saving themselves.

A naval battle brings a double jeopardy to the crews of the engaged vessels should they be sunk. To the malign efforts of the enemy is added the subsequent struggle to survive the sea. Far from land; or in foul weather; or at night; or a combination of all three, rescue becomes a lottery in which there are few winners. By the very fact that the ship has been brought to the point where it can no longer float, it is unlikely that most, if any, of its boats and lifesaving equipment will still be serviceable. Pieces of flotsam represent the only source of artificial buoyancy, and, in icy temperatures and high seas, the onset of hypothermia is rapid. In tropical waters, the merciless sun, dehydration, sharks and predatory seabirds soon achieve the same result. In the meantime, the battle moves on at 20-30 miles per hour, and the longer the conflict lasts, the further away disappears the means of succour. Only the fittest, the previously unscathed, and the luckiest, live to perhaps tell the story of the ordeal.

The problem is compounded by the nature of modern war. In the Napoleonic era and before, naval battles were fought at point blank range between wooden walls that bombarded each other until one or the other was no longer able to resist. At that point, the defeated ship surrendered. Its sturdy wooden construction usually ensured that, no matter how shattered, it continued to float, and that the wounded at least had a secure platform on which their injuries could be treated, however inadequately. In the new era of steam and steel, battle ranges increased to the point that they were only limited by visibility or the scope of the guns. Where wooden ships floated next to their conqueror, steel ships sank miles distant from their opponent. The opportunities for rescue, and care of the injured, drastically reduced as naval warfare changed. In any case, five or ten miles distant from an opponent, there was little ability to communicate a wish to surrender even if that humiliation could have been contemplated. A final painful irony is the fact that if the ship had been fought well, it would almost certainly have destroyed, or rendered temporarily useless, most of the victor’s seaboats and life-rafts, and with them, therefore, the latter’s ability to rescue survivors.

Despite all of this, in the new ironclad era there arose an irrational belief that surrender was somehow shameful. The consequent loss of good men, in hopeless situations, became a triumph of glorious and tragic stupidity over common sense. There were very few commanders who had the moral courage to strike their flag when resistance was no longer possible.

That is the lot of the ‘fortunate’.

For a ship that explodes to its death, thoughts of surrender are entirely irrelevant. The process is almost instantaneous and there are very few, if any, survivors of the cataclysm. All the physical remains of the ship vanish into the depths of the sea within a few minutes bar some pieces of flotsam. In the case of a large ship, a whole, living, self sufficient, community with the complexity and working male population of a medium sized town, has vanished in the blink of an eye. There is no other military catastrophe that can equate to this event. For a ship that blows up in action, the loss is total—absolutely total and final.

The destruction of HMS Queen Mary

A Battleship or Battlecruiser carries a crew the size of an army battalion. There is not just a Captain, a Commander, navigators, engineers, sailors and gunners. There are also bakers, butchers, cooks, stewards, policemen, medical staff and supply personnel. There are mechanics, carpenters, electricians, armourers, blacksmiths and artisans of every kind. There are Doctors, schoolmasters, and a Padre or two. The Royal Marines provide soldiers, gun crews and a band. Livestock is carried on board, and also the cats, dogs, birds and other creatures that are the pets of the crew. There are youngsters in their teens to grizzled old veterans; there are saints and sinners at all levels, and there are the progeny of aristocracy and the orphans of the dockyard ports. It is a Ship’s company.

For several years, this body of diverse humanity coheres, learns to exist as an independent entity, live together, entertain itself, and hone its skills. It becomes with training and experience a close knit community and a highly efficient weapon of war. The ship itself is at the core of the community. Some, for unexplained reasons, are better than others. All have their own personality, which filters down through the characters and events which have encompassed its life. On a basic level, it provides the generating station for electricity, and, therefore, the light, power, heating and ventilation for its myriad compartments. Its own internal telephone system links every area and its kitchens, machine shops, wireless rooms, laundries, Sick Bays, et al., cater for its population. It feeds them and houses them in its canteens, dormitories and cabins. Its small boats shuttle them to and from shore. In return, the crew maintain its machinery, keep it clean and ready to fight. They polish its bright bits, scrub its wooden bits and paint its grey bits even though the constant drudgery drives them to distraction. The older it gets, the more effort is required, but, if the work is begrudged, the old ship starts to become a character, however grumpy, and engenders, sometimes, a sense of pride in its inhabitants. Even its evident faults and geriatric perversions become a source of grim amusement and bad jokes. This is not always evident within the confines of the ship but is sometimes made apparent to outsiders who intrude on ‘in house’ gripes.

In times of peace or inactivity, crews are employed on tasks that owe more to the principle of giving idle hands something to do than to any meaningful end. On the day of battle, this changes. The numbers of people accommodated on the ship are not there by accident. Every single person on board has a specific purpose. Officer’s Stewards become medical orderlies; Midshipmen under training become communication links; Boy Seamen become runners between sections of the ship; Seamen and Stokers not immediately required to man the armament or the boilers form teams to deal with damage control. As the ship goes into action, there would not be anyone who did not have an allocated station or a clear idea of his place in the overall organisation of the ship. Every single man on that ship is fully engaged in a useful activity at the moment of his death.

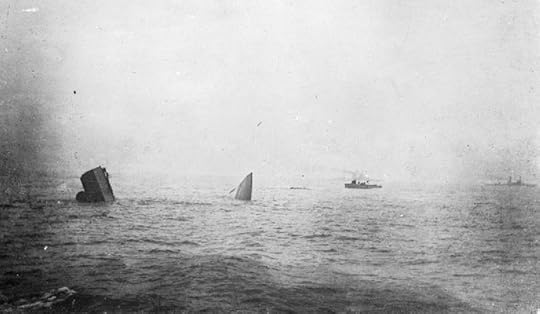

The destruction of HMS Indefatigable

When the hit comes that destroys the ship, it finds this community at its highest level of intensity, and at the moment of its greatest sense of purpose. It is at the climax of its existence, and at the very height of its efficiency. The adrenaline is flowing in every vein of every person that mans the ship. The ship itself is probably being forced to speeds and performances that touch the limits of its design, and are requiring efforts that are testing its ageing bones and muscles to the utmost. Then, in one instant, everything, human and inanimate, is utterly and irrevocably obliterated.

The only comparable event to the blowing up of a capital ship in action would be a nuclear strike on a medium sized town. Think about it—and, when any writer talks about a ship being lost in action, or blown up, think a little more—and perhaps remember the vibrant communities that comprised the crews of the three lost British battlecruisers at Jutland: Indefatigable, Queen Mary, and Invincible. Spare a thought also for the old cruisers Defence and Black Prince, the German battleship Pommern, and the cruiser Frauenlob. These were ships whose destruction was measured in seconds, and from whom there were no survivors from complements of mostly over 750 men.

In some respects their crews might even be considered fortunate. In their case, death came without preamble, and without any time to consider the prospect. Other vessels fought hopelessly for hours, and their crews had to witness the appalling progressive destruction of their ship and the slaughter of their friends and compatriots before they, themselves, succumbed to drowning without a chance of rescue. It is no denigration of the other armed services to make the point that no force other than the navy is ever exposed to the totality of loss that is always present in a naval engagement. There are no eye witness accounts of the demise of Scharnhorst or Good Hope; nor of Koln or Monmouth. Their destruction was protracted and cannot have been anything other than an appalling experience whilst it was being endured beyond hope of any relief. To properly appreciate any account of naval warfare and the sacrificial effort involved, the bald and inadequate descriptions of the loss of ships should be read with these images in mind. We, who write about these events, and those of you who read about them, can only thank our lucky stars that we were not part of them, or at least not on the wrong end of them.

The bow and stern of HMS Invincible standing upright on the bed of the North Sea after being sunk during the Battle of Jutland

David Gregory served as a seaman officer in the Royal Navy during the 1960s before spending six years in the Sea Wing of the nascent Abu Dhabi Defence Force. Subsequently, he worked worldwide in the offshore oil industry as master of salvage tugs and support ships. In 1980, he became a full time professional yacht captain and delivery skipper.

David Gregory served as a seaman officer in the Royal Navy during the 1960s before spending six years in the Sea Wing of the nascent Abu Dhabi Defence Force. Subsequently, he worked worldwide in the offshore oil industry as master of salvage tugs and support ships. In 1980, he became a full time professional yacht captain and delivery skipper.

He is the author of the ‘The Lion and The Eagle’, a trilogy dealing with Anglo-German naval affairs and conflict before and during the First World War. The third volume of the series will be published in 2016.

May 17, 2015

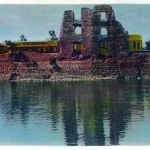

Photo Gallery: Iraq – Historical & Religious Sites

This is part of the the Antoni Paszkiewicz project.

The Lion of Babylon in the ancient city of Babylon, November 1942

Notwithstanding the looting that took place following the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the recent destruction of ancient artifacts and religious sites by the grotesque extremists of the so-called Islamic State, Iraq has always been rich in historical antiquities.

Toni collected postcards and took photographs of a number of sites that he visited in November and December 1942. This gallery shows his photographs and more modern images, which show the sites as they are today and provide a short description of them.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

May 15, 2015

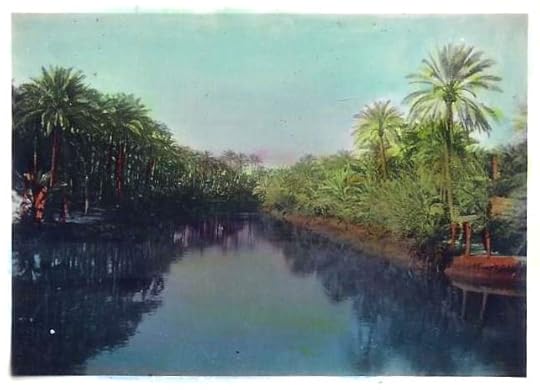

Photo Gallery: Iraq – Date Palms

This is part of the the Antoni Paszkiewicz project.

‘Irak, daktyle, 1942r’ – Iraq, dates, 1942

The date palm has always been an important part of the agricultural bedrock of Iraq and the precursor nations and empires in this region. Cultivated for over 5,000 years, the date palm has been used for food, medicine and building materials from the time of the Sumerians. The trees were grown in huge numbers along the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates and in the south around Basra. Iraq became the largest producer of dates in the world and had the largest date forest in the world. Sadly, this important staple crop was largely destroyed in the south of the country during the Iraq-Iran war and subsequent conflicts have prevented its resurgence.

Toni grew up in eastern Poland, was imprisoned in Soviet Russia and was now in the ‘Garden of Eden’. Travelling in Iraq must have been an extraordinary experience. Not surprisingly, he took a number of photos of date palms, which characterise this exotic land.

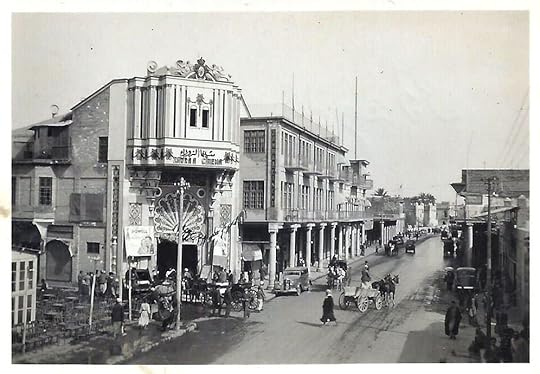

Photo Gallery: Iraq – Baghdad

This is part of the the Antoni Paszkiewicz project.

‘Bagdad, XI 1942r’ – Baghdad, November 1942. The Zawraa cinema; the film being shown is ‘Rendezvous’, a 1935 film starring William Powell and Rosalind Russell.

The majority of Polish forces were concentrated at Khanaqin, a little over 250 miles north-east of Baghdad. From the captions on the back of his photographs, it appears that Toni visited Baghdad in November 1942 and February 1943.

May 14, 2015

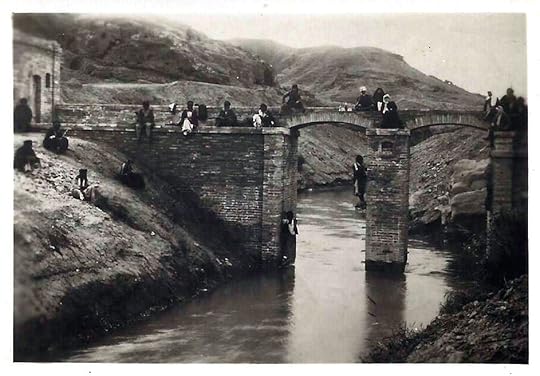

Photo Gallery: Iraq – The Land of the Two Rivers

This is part of the the Antoni Paszkiewicz project.

Iraq, December 1942

Through Iraq flow the two great rivers, the Euphrates and the Tigris. They rise in the mountains of eastern Anatolia and course south-east through the gorges of modern Syria and northern Iraq, across the alluvial plain of central Iraq to Al-Qurnah in the south, where they join to form the Shatt al-Arab, the ‘Stream of the Arabs’ (in Persian, the Arvand Rud, the ‘Swift River’). The Shatt al-Arab then flows past Basra and into the Persian Gulf at Al Faw.

Many of Toni photographs are of the rivers or the people that worked on them. The Polish captions are Toni’s, written on the back of the photographs; English translations and English captions are mine.

May 13, 2015

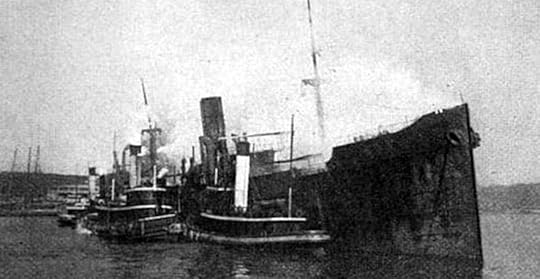

Sacrifice – Latest Post – the SS Kerry Range

The latest addition to the Sacrifice project is the story of the SS Kerry Range, which was wrecked in a fire that destroyed Pier 9 at Locust Point, Baltimore on 30 October 1917. A Royal Navy sailor, Leading Seaman Eustace Alfred Bromley, two Mercantile Marine sailors, and a local civilian clerk were killed. Only Leading Seaman Bromley is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Read about the fire that wrecked the SS Kerry Range.

SS Kerry Range scuttled in shallow water in Baltimore harbour

April 24, 2015

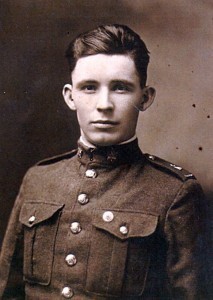

ANZAC Day – Lieutenant Norman Travers Simpkin

Sergeant Norman Travers Simpkin, 2nd Australian Light Horse Regiment

To add to the ANZAC commemorations I have written a piece for the Sacrifice project about the only soldier to serve at Gallipoli who is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in the United States. Travers Simpkin served with 2nd Australian Light Horse Regiment and was wounded at Quinn’s Post in August 1915. He died in California in 1919.

April 13, 2015

‘Sacrifice‘ – Project Update and New Post

The website for the new project has now been populated in outline with biographies completed for North Carolina and Virginia. Please consider following the project by subscribing to the blog. We’re just about to begin to publicise it and to seek volunteers to help with the work.

The website for the new project has now been populated in outline with biographies completed for North Carolina and Virginia. Please consider following the project by subscribing to the blog. We’re just about to begin to publicise it and to seek volunteers to help with the work.

Private Baxter Franklin

The latest post tells the story of Baxter Franklin, a young farmer from North Carolina, who worked as a teamster in Canada and volunteered in 1914, aged 17, fought in Flanders with 10th Battalion (Canadians), and was evacuated sick in 1916. He died in Toronto in 1918 and was buried at Lake Logan, NC, near where he was born.