Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 12

April 6, 2015

The Evolution of the Regular and Service Battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918 – Part 4, The 5th, 6th, 5th/6th & 11th (Service) Battalions

This essay describes the evolution of the 5th and 6th (Service) Battalions and the formation and short life of the 11th (Service) Battalion. The background to this essay may be found here.

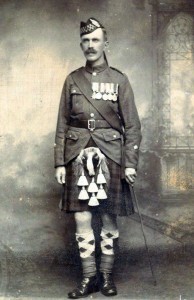

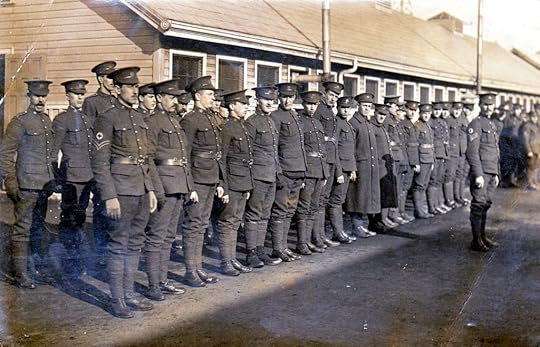

Colour Sergeant James Sergeant, 5th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers)

5th & 6th (Service) Battalions

Immediately on becoming Minister of War, Lord Kitchener proposed that the British Army be expanded by recruiting wartime volunteers, rather than building upon the Territorial Force. These men would sign up for three years or the duration of the war, whichever was longer. On 6 August Parliament authorised the expansion of the Army by 500,000 men[1] and recruiting began immediately.

The first New Army battalion of the Regiment was raised on 10 August 1914 in Armagh. On 21 August 1914, Army Order 324 authorised the formation of the first six new divisions, which included the 10th (Irish) Division.[2] The nomenclature specified by the order meant that the new battalion of the Regiment was to be the 5th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers).

The Battalion began recruiting at the Depot in Armagh, where it was joined by a number of regular officers. On 24 August it moved to Portobello Barracks in Dublin. Recruits arrived from counties Armagh, Cavan and Monaghan and comprised men from all walks of life, denominations and political views—the first to enlist have often been regarded as the best of their generation. On 10 September orders were received to transfer 400 men to form the 6th (Service) Battalion, at that stage still only a cadre.[3] At the end of the month 500 more men were dispatched to form the basis of the newly raised 7th (Service) Battalion, which was to be part of 16th (Irish) Division.[4]

These first enlistments to the 5th and 6th (Service) Battalions, including some of those dispatched to the new 7th (Service) Battalion, amounted to about 2,350 men by mid-September 1914.

The 5th and 6th Battalions trained in Dublin as part of 31st Brigade until April 1915 when they, and the other units of 10th (Irish) Division moved to Basingstoke, arriving on 29 April. After a further period of training, on 11 July both Battalions embarked at Devonport for the Mediterranean and the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers embarked with 30 officers and 951 other ranks; 6th Royal Irish Fusiliers embarked with 32 officers and 930 other ranks.

The Battalions landed at Suvla Bay on 7 August and for nearly two months fought in deplorable conditions, suffering significant casualties—by 16 September the 5th Battalion had been reduced to ‘four officers and about 160 other ranks’.[5]

Major F W E Johnston, 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers, wounded at Gallipoli

On 30 September 1915 both Battalions sailed for the island of Lemnos for a period of recuperation. Here 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers was reinforced by a draft of men from 10th (Irish) Division Base Depot at Mudros. Meanwhile, 6th Royal Irish Fusiliers received two officers and 105 men. These men comprised some who had been specifically detached to the Depot in early August and others who had arrived from Ireland during the Gallipoli operations. Also attached to 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers a few days later were three officers and 140 men of The Royal Irish Rifles.

On 28 October both Battalions arrived in Salonika, where the men of The Royal Irish Rifles rejoined their battalions. On 4 November 6th Royal Irish Fusiliers was reinforced by a draft of one officer and 98 men from the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion. Three weeks later, on 24 November, a large draft of nine officers and 349 men joined 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers; these men were from The Bedfordshire Regiment and were described as ‘very good material’.[6] This period of operations north-west of Lake Doiran was characterised by appalling winter weather, which caused many more casualties than the minor operations against the Bulgarians in December.

The Battalions’ moved south towards Salonika in December 1915, where until June 1916 they were engaged in security duties and the back-breaking work, building roads and the ‘cutting of trenches in almost solid rock’.[7] Both Battalions were then engaged in training and operations in the Struma Valley in northern Macedonia.

In January 1916 small drafts of men had joined 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers from the 10th (Irish) Division Base Depot—all Irishmen—and on 4 September a further 46 men arrived from the 4th (Reserve) Battalion. In October arrived small drafts of men from The Suffolk Regiment (10 men), The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) (14 men) and The South Wales Borderers (19 men).

Meanwhile, an officer and 14 men from The Dorset Regiment had joined 6th Royal Irish Fusiliers on 22 January and 19 Irishmen arrived on 28 January. On 5 April a large draft arrived from one of the reserve battalions at home—one officer and 173 men. Finally, 54 men arrived in mid-October who had been transferred from Yeomanry regiments for service with infantry.

5th/6th (Service) Battalion

Due to the casualties sustained by both battalions, mostly from sickness, on 1 November 1916 orders were received to amalgamate the 5th and 6th Battalions, which was duly done on 2 November. 31st Brigade was augmented by the arrival of the Regiment’s 2nd Battalion. The next 11 months were spent holding the line; this was a tedious period when the greater enemy was the winter weather and, come spring, malaria-carrying mosquitoes. A small draft of 18 men of The Welsh Regiment arrived in August 1917.

The next move of 5th/6th Royal Irish Fusiliers was to Egypt, where it arrived on 25 September 1917 and, soon thereafter, to Palestine. In the fighting there over the next seven months the battalion incurred a steady number of casualties but received little by way of reinforcement.

Finally, in May 1918, the Battalion left the Middle East for France, where it arrived on 27 May. Initially part of 14th (Light) Division, the 5th/6th Royal Irish Fusiliers suffered grievously from the change in climate and ‘several hundred’[8] men were hospitalised with a recurrence of malaria. The quality of the Battalion ensured its survival, however, rather than being broken up for drafts, and it was transferred to 30th Division and soon afterwards to 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division. In July and August 1918 large numbers of men went home on leave—many of them for the first time since late-1914/early-1915.

On 24 August 1918 5th/6th Royal Irish Fusiliers transferred between divisions for the last time. It transferred to 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division. When 150 other ranks of 11th Royal Irish Fusiliers were absorbed on 27 August, it became the only Irish battalion in the Division.[9] It was disbanded in June 1919.

11th (Service) Battalion

The 11th (Service) Battalion was raised at Greatham, West Hartlepool on 1 June 1918 from a cadre from the 3rd (Reserve) Garrison Battalion. It comprised, therefore, men from every Irish infantry regiment and from a number of English regiments and the Royal Army Service Corps. Some had seen service in France, Flanders or the Mediterranean, but others had only served in the United Kingdom.

It absorbed the training cadre of the 7th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers on 18 June. That Battalion had a similar history to the 5th and 6th Royal Irish Fusiliers—raised in September 1914 for 30th Brigade, 10th (Irish) Division; service at Gallipoli and in Salonika; and to France in June 1918, where it was reduced to a cadre. On its return to England it was absorbed by 11th Royal Irish Fusiliers a few days later.

11th Royal Irish Fusiliers joined 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division at Aldershot at the end of June and landed in France on 1 August 1918 with a strength of 30 officers and 262 other ranks. On 11 August a further 10 warrant officers and NCOs arrived from England. Notification that the Battalion was to be amalgamated with 5th/6th Royal Irish Fusiliers arrived on 23 August. That duly occurred on 27 August 1918, when 150 other ranks joined 5th/6th Royal Irish Fusiliers. The remaining men joined 16th Division Reinforcement Camp for onward posting.

Details on each of these drafts may be found here: Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918 – Reinforcement Drafts

Back to ‘The Evolution of the Regular and Service Battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918’ main page.

1. (Back) House of Commons. (6 August 1914). Hansard. Vol 65, c 2100.

Resolved, ‘That an additional number of 500,000 men of all ranks be maintained for service at home and abroad, excluding His Majesty’s Indian possessions, in consequence of War in Europe, for the year ending on the 31st day of March, 1915.’

2. (Back) AO 324 of 21 August 1914 ran to 13 pages and specified details of organisation and training. The nomenclature to describe the new battalions appeared early in the order:

I – Augmentation of the Army

With reference to Army Order II of 6th August 1914 (as amended by AO III of 7th August 1914) introducing special terms of enlistment into the Regular Army, His Majesty the King had been graciously pleased to approve of the addition to the Army of six divisions and Army Troops.

The composition and nomenclature of the new units and formations will be shown in Appendix A. The establishment of each unit will follow War Establishments (Part I) 1914.

The new battalions will be raised as additional battalions of the regiments of Infantry of the Line, and will be given numbers following consecutively on the existing battalions of their regiments. They will be furthur distinguished by the word ‘Service’ after the number, e.g. – ‘8th (Service) Bn. The Royal Welsh Fusiliers.’

Recruits will be clothed and equipped at depots, and subsequently collected at training centres, where brigades and divisions will be formed.

3. (Back) Johnson, F W E (Foreword). (1919). A Short Record of the Services and Experiences of the 5th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers in the Great War. Naval & Military Press Reprint, 2009.

4. (Back) Ibid.

5. (Back) Ibid.

6. (Back) Ibid.

7. (Back) Ibid.

8. (Back) Ibid.

9. (Back) Some records record that 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers absorbed 11th Royal Irish Fusiliers on 29 August. The Battalion’s war diary is clear this actually took place on 27 August, with the Battalion moving forward into reserve at Barlin on 28 and 29 August.

March 29, 2015

Parachute Training 1943

This essay is part of the the Antoni Paszkiewicz project.

‘Mass Dropping’ at Tatton Park

Toni Paszkiewicz arrived at RAF Ringway near Manchester in the late summer of 1943 for parachute training.

This was not the first training for his new role that he had undertaken. The Poles had a rigorous pre-parachute training regime at Largo House in Fife. From his conception of the idea of a Polish Parachute Brigade in early 1941, Colonel Stanislaw Sosabowski had placed great emphasis on fitness and preparing his men for the jumps course at Ringway and the rigours of war in the liberation of Poland.

Largo House became the training centre for Colonel Sosabowski’s brigade in February 1941. Built in the 1750s for landowner James Durham, the impressive house and its outbuildings were ideal for indoor instruction and the surrounding park became the focus for physical training. Engineers built an obstacle and confidence course in the woods that soon became known as Małpi Gaj—the Monkey Grove. One of Sosabowski’s officers wrote:

‘Jump, skip, hop. Stand, lie, fall. Arms, legs, heads. Swinging, bending, stretching. Aching, sighing, moaning, groaning. Into a mad Monkey Grove, shouted at by monkey-like men. Jump from fallen trees; somersault forwards, backwards, sideways. Fall gently—GO!—use angle of bones and limbs, fall side of calves, side of knees, thighs, roll onto back of shoulders. Stand up, fall down, stand up and get knocked down. Jump from tree trucks, fall out of windows…swing from trees…get thrown from trees…play monkey’s upside down…GO! GO! GO! Every other word is GO![1]

This emphasis on physical training was particularly important for the men who arrived from the Middle-East. Colonel Sosabowski was not impressed by the first to arrive in the late summer of 1942:

‘…I was appalled by their condition. Many were unfit to be in the army, let alone in a Parachute Brigade. Their physical condition after months of starvation and lack of exercise in concentration camps had left them weak and skinny.’[2]

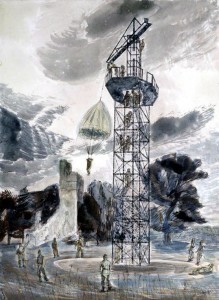

One of the most valuable training facilities was ‘the Tower’. This steel construction, which allowed instructors to train the men in the practical aspects of a parachute descent and landing, was the first of its kind to be built in the United Kingdom.

The Training Tower at Largo by Edward Bawden

Polish soldiers training on the Tower at Largo

After two weeks’ in the Monkey Grove and on the tower the men were sent to RAF Ringway for the next phase of their training.

Manchester (Ringway) Airport had been opened in 1937 and part of it had become RAF Ringway in 1940. In June 1940 it became the home of the Central Landing School. This new establishment became the Parachute Training Squadron of the Central Landing Establishment in October 1940. In February 1941 it became an independent unit and was renamed the Parachute Training School.

The school was responsible for the initial training of all allied paratroopers trained in Europe. The airfield itself was not suitable for a drop zone and a suitable site was found at nearby Tatton Park, the estate of the Egerton family since the 16thC, five miles from the airfield. The first jump by instructors there took place on 13 July 1940 from a converted Whitley bomber, with the first trainees jumping the next day.

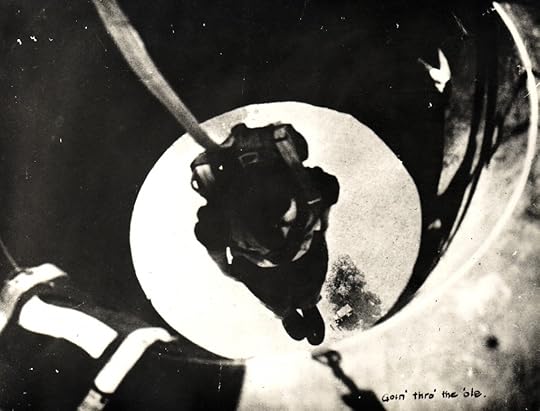

The jumps course at RAF Ringway comprised instruction in exiting the aircraft, controlling descent and landing techniques. This was followed by the first jumps from a balloon at Tatton Park. These were converted barrage balloons with a cage fitted underneath; the cage had a hole in the floor, to replicate the hole in the floor of the Whitley bomber, and a bar to which was attached the static line for the parachute. Having been bused to Tatton Park from Ringway, the trainees climbed into the cage in a group of four or five with an instructor. The balloon was then allowed to rise, tethered by steel cable, to 800 feet. The trainee then sat on the edge of the hole with his parachute’s static line connected to the bar. On the command “GO!” the trainee jumped, being careful not to lean forward, which would result in a bashed face, or lean back, which would result in his parachute catching on the rim of the hole, throwing him forward and, again, risking a broken nose. After a short fall the static line pulled the parachute out and the trainee descended, with an instructor on the ground giving instructions. The process was repeated until everyone had completed their two balloon jumps. Next was the real thing.

When Toni went through his training at Ringway, the aircraft used by the PTS was the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley. The Whitley was a medium bomber that had been in service with the RAF on the outbreak of war but which had been withdrawn from front-line bomber service at the end of 1942. It remained in service as a transport aircraft, for parachute training and towing gliders, and in a specialist electronic warfare role in 100 (Bomber Support) Group.

Dropping from a Whitley bomber at Tatton Park

The converted bombers had an exit hole in the floor of the fuselage through which the trainee exited; they carried ten trainees and an instructor. Tom Hicks, who served with the Royal Engineers and fought at Arnhem, wrote about his training at Ringway:

‘Jumping from a Whitley bomber is a different kettle of fish to jumping from a balloon, as inside they are long, narrow, windowless and dark with no room to stand up straight. The floor on which we had to sit was hard decking as the Whitley didn’t have any seats. We sat alternately opposite one another down the sides of the aircraft with our legs out straight, five before and five aft of the hatch that covered the hole…

…On approaching the Drop Zone (DZ) the hinged doors of the hole were folded back and the first man positioned himself on the rim with his legs in the hole, the next man sat directly opposite with his legs askance ready to swing his legs into the hole to follow. The green light came on and we were out. As practised many times in simulated training, the approach to the hole was made alternately on our backsides from either side of the aircraft. The whistle and cold blast of air from the hole was ignored as all concentration was on getting out fast. As you dropped out of the hole the strength of the slipstream threw you almost horizontal until clear of the aircraft and then you started to drop.’[3]

Goin’ thro’ the ‘ole

After five jumps from the Whitley in daylight and a final night jump, Toni had qualified as a parachutist, a few weeks before his 22nd birthday.

The eagle by the graphic artist Marian Walentynowicz that was the inspiration for the Polish parachute badge

The symbol of Toni’s qualification was the Znak Spadochronowy—the paratrooper’s badge. The idea for such a badge was conceived in June 1941. The design was based on an illustration by the graphic artist Marian Walentynowicz in Ziemia gromadzi prochy (Earth Gathers the Ashes) by Joseph Kisielewski. Published in 1939, the book described Kisielewski’s travels in Germany and predicted the imminent outbreak of war. It was banned subsequently by the German occupation administration but proved to be immensley popular in Poland and amongst the Poles in exile. The badge was formally established by order of General Władysław Sikorski, Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, on 20 June 1941. This order laid out the basic regulations for its design and award.[4]

The Znak Spadochronowy awarded to Toni Paszkiewicz

The silver-plated and oxidized brass badge is a representation of an attacking eagle, diving with its talons extended. On the reverse is stamped a unique serial number—Toni’s is 3767—and the motto ‘TOBIE OJCZYZNO’ (For You Motherland). It was made firstly in-house by Gr. Techn.[5] and latterly by Kirkwood & Son, a well regarded medalist in Edinburgh. The badge is attached to the tunic by a threaded metal post pushed through a hole in the tunic and secured by a brass ‘spinner’.

Antoni Paszkiewicz wearing his parachute qualification badge and parachute collar badges

Following the airborne assault at Arnhem, the order regulating the combat parachute badge was amended—a gilded, laurel wreath held in the eagle’s claws replaced the golden beak and talons. Toni Paszkiewicz did not receive the wreath—he was injured in a parachute jump prior to the Arnhem operation and did not parachute again.

This short news clip from British Pathé shows British and Polish troops training in 1943 (prior to Toni Paszkiewicz’s jumps training).

Acknowledgements:

http://www.591-antrim-parachute.info

The Bridgeford Family for the photographs of parachute training at RAF Ringway (from the estate of Captain R A Bridgeford RE).

British Pathé for the clip of paratroopers training.

1. (Back) Sosabowski, S. (2013). Freely I Served. p 100. Barnsley: Pen & Sword.

2. (Back) Sosabowski. Op. Cit. p 108.

3. (Back) Hicks, N. (2013 ) Captured at Arnhem: From Railwayman to Paratrooper. Barnsley: Pen & Sword.

4. (Back) I have attempted to make this translation accurate in meaning, rather than provide a literal translation.

The approved badge is in the shape of an attacking eagle. In exile, where Poles think constantly of their return home with different images in mind, it especially makes sense. The Polish Army foresees its return to the fight, sacrifice and glory. Before they rest in their liberated land, we want the victorious standards of our eagles to fall on the enemy.

I establish two types of parachute badge: combat and ordinary. The combat parachute badge differs from the ordinary badge in that the eagle has a golden beak and talons. The badge is to be worn on the left breast above medals. On the inner side of the badge is inscribed the motto: FOR YOU MOTHERLAND – and the registration number of the badge.

Only soldiers who have taken part in a combat parachute action have the right to wear the combat badge. Parachute troops having undertaken the relevant training have the right to wear the ordinary badge.

The combat parachute badge is awarded by the Commander-in-Chief on the recommendation of the Chief-of-Staff to the C-in-C. A Corps Commander, or equivalent, has the authority to award the ordinary badge. Awards of the combat badge will be announced in the orders of the Commander-in-Chief, ordinary badges in Corps Commander’s orders. The registration number of the badge is to be shown on the personal identity card.

The right to wear the parachute badge will be withdrawn for conduct unworthy of a Polish soldier’s uniform. Such decisions in relation to the combat badge are the responsibility of the Commander-in-Chief, and the Corps Commander or equivalent in relation to the ordinary badge.

Honorary parachute badges may not be awarded.

5. (Back) Grupa Techniczna Ośrodka Radio Sztabu Naczelnego Wodza w Londynie (The Technical Division of the Radio Unit of the Commander-in-Chief in London).

March 20, 2015

Journey to Britain

This essay is part of the the Antoni Paszkiewicz project.

Troopships RMS Aquitania and SS Ile de France

In the spring of 1943, Toni Paszkiewicz volunteered for service with the 1st (Polish) Independent Parachute Brigade—another essay will cover the formation of this fine brigade and Toni’s service with it.

His journey from the Middle-East to the United Kingdom was to be aboard the French liner SS Ile de France. This was a majestic ship—she was reputed to have had the most beautiful interiors of any of the ocean liners built for the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, the ‘French Line’.

Laid down in 1925 at Saint-Nazaire, the Ile de France was built by Chantiers de Penhoët, a major French shipbuilding company with a world-class reputation for the quality, size and style of its ships. She was decorated in the Art Deco style with large, open interior spaces, which were the subject of numerous magazine articles and news stories.

Launched on 14 March 1926, she sailed on 22 June 1927 for New York on her maiden voyage. The beauty of the ship and her popularity on the transatlantic crossing led to record profits for her owners. The ship had a catapult-launched seaplane fitted in 1928, which, carrying mail, flew from her rear decks for the first time on 13 August as she approached New York, reducing transatlantic mail delivery by a day.

SS Ile de France in her heyday

The final pre-war journey of Ile de France as a commercial liner began only hours before war was declared on 3 September 1939 when she sailed from her home port, Le Havre, to New York, berthing on 9 September. Her early wartime role was as a general transport, first for the French and then for the British, primarily on routes across the Indian Ocean between Durban and Suez, with the occasional foray to Bombay. In South Africa she was gutted of her beautiful finery and converted to a prisoner of war troopship to move German and Italian prisoners from north Africa to South Africa. In late-1942 she underwent another overhaul and refitting and, now able to carry over 7,000 troops, she began her final northward journey from Durban in April 1943.

Ile de France departed Durban on 19 April, sailing independently and relying on her speed to evade detection and attack. This ability to sail independently of an escort was a characteristic of the fast (more than 20 knots), large (over 35,000 tons), ocean-going liners used as troop ships and known as ‘monsters’—RMS Aquitania, SS Ile de France, RMS Mauretania, RMS Queen Mary, RMS Queen Elizabeth, and SS Nieuw Amsterdam.

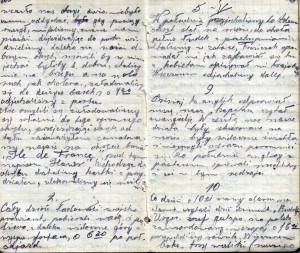

Toni Paszkiewicz’s diary describing the beginning of his journey to the United Kingdom

Ile de France arrived at Suez on 30 April and Toni Paszkiewicz and the others of the Polish party destined for the United Kingdom, along with a contingent of Commonwealth troops, embarked on 1 May. She sailed the following morning at 6.30am on an independent run down the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea for Aden, where she arrived three days later, on 5 May. She departed Aden the next day for Durban and sailed through the Gulf of Aden, south through the Indian Ocean and into the Mozambique Channel, arriving in Durban on 16 May. This was not the simple journey that it sounds. There was a considerable threat from German and Japanese submarines off the eastern coast of Africa, particularly around Madagascar.

Again sailing independently, Ile de France departed Durban on 22 May and sailed around the Cape into the south Atlantic. She was destined for Freetown in Sierra Leone but sailed to Rio de Janeiro, where she arrived on 3 June. The final stage of her journey took her back across the Atlantic to Freetown, arriving on 11 June and the next day she sailed alone for Scotland. Ile de France arrived safely in the Clyde on 20 June 1943.

Toni Paszkiewicz disembarked with his fellow Poles the next day and was transported to his new home with the 1st (Polish) Independent Parachute Brigade in Fife.

As for the Ile de France, she worked as a troopship for the rest of the war and returned to commercial use after a major overhaul and refitting that began in 1947. Her first crossing to New York was made in 1949 and she remained a popular ship until she was sold for scrap in 1959.

Her final role was as the SS Claridon in the disaster film The Last Voyage.

Acknowledgement:

Arnold Hague Ports Database for the detail of the journey of Ile de France from Durban to the United Kingdom.

British Pathé for the film clips of Ile de France.

March 4, 2015

The Sergeant Brothers

The Sergeant Brothers

In the Saturday edition of the Lurgan Mail on 25 November 1916 there was a page dedicated to ‘Patriotic Familes’—those families from the town with more than three members serving with the British Army, the Royal Navy and the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The page, the large format page rarely seen in newspapers today, had three columns of names and listed 88 families. Four families had six sons serving, one had a father and his five sons in the Army and Royal Navy, and 16 families had five sons at war. Two years into the conflict, the number of families recording multiple men killed, wounded and missing was considerable.

This degree of commitment was not unique to Lurgan nor, indeed, the United Kingdom—Mrs Charlotte Wood, an English born Canadian, saw eleven of her sons enlist, of whom five were killed in action and two severely wounded.

The Sergeant household from Gilford in County Down was another whose sons contributed much. This was a large family. Samuel, a linen bleacher, and Margaret Ann (née Sands) from Drumarran had 12 children, 11 of whom survived childhood—eight boys and three girls. Five of the brothers served during the First World War, and a sixth served after the war. One was a regular soldier, the others were wartime volunteers. One was killed in action on the first day of the Battle of the Somme; the others survived.[1]

16/512 Corporal George Edward Sergeant, The Royal Irish Rifles

Corporal George Sergeant (right)

George Sergeant enlisted in the autumn of 1914, aged 17. The 16th (Service) Battalion (2nd County Down) was raised somewhat later than the other battalions of 36th (Ulster) Division and some of its men came from those who had already volunteered and were in training at Clandeboye. The local newspapers of 7 November advertised for recruits for the new battalion and called for volunteers ‘who did not respond to Lord Kitchener’s initial appeal’.[2] In the absence of his service record it is impossible to say when exactly that George Sergeant enlisted but his regimental number puts him amongst those who joined the battalion in December 1914.

Private George Sergeant

George was barracked relatively close to home at Brownlow House in Lurgan. In January 1915, 16th Royal Irish Rifles was formally acknowledged as the pioneer battalion of 36th (Ulster) Division. Its training continued at Lurgan until it moved with the rest of the Division to Seaford on the Sussex coast. George landed in France with 36th (Ulster) Division on 5 October 1915.

At some time (possibly in early 1918) George Sergeant was renumbered 22021. He may have been wounded previously or fallen sick, and was discharged and subsequently re-enlisted. In this new guise he served for the remainder of the war, for a period in the 1st Battalion, finishing the war as a Corporal in 12th (Service) Battalion (Central Antrim) in 107th Brigade, 36th (Ulster) Division. After the war he was transferred to the Class Z Reserve.[3]

On 1 March 1921 George Sergeant married Sarah McCreanor at Tullylish parish church. George Edward Sergeant died at Gilford on 22 October 1935, aged 38; his wife died on 15 April 1976, aged 77.

His medals group comprises: 1914-15 Star; British War Medal 1914-20; and Victory Medal.[4]

8300 Company Quartermaster Sergeant James Sergeant, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), and The London Regiment

Colour Sergeant James Sergeant, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers)

James Sergeant was a regular soldier. He enlisted into the British Army in January 1904, aged 18, and joined Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers); he served with the 1st Battalion. It is not known whether he was serving when war broke out or if he was recalled from the Army Reserve but he joined the 5th (Service) Battalion in Dublin, part of 10th (Irish) Division, and was appointed as a company quartermaster sergeant.

The Battalion embarked on the RMS Andiana on 11 July 1915 destined for the Mediterranean. There is no record of James’ role in the Gallipoli landings nor, indeed, in the later history of the Battalion in Salonika or Egypt. It is known that he was promoted to Warrant Officer Class 2 and served as a Company Sergeant Major with the 5th/6th Royal Irish Fusiliers after the amalgamation in November 1916.[5]

Before the 5th/6th Royal Irish Fusiliers embarked for France in mid-May 1918, Company Sergeant Major Sergeant was attached to 1/10th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (Hackney) in 162nd Brigade, 54th (East Anglian) Division. He was transferred later and renumbered 424748. He served with 1/10th Londons until the end of the war in Egypt and through the final operations in Palestine, finishing the war in Beirut.

Company Sergeant Major James Sergeant, Princess Louise’s (Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders)

After the war, in 1919, he re-enlisted to serve as a regular soldier with Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (renumbered 32905 and renumbered 7041183 in 1920) and served as a company quartermaster sergeant with the 1st Battalion, which included the operations in Iraq and North West Persia in 1919 and 1920. Soon thereafter, he transferred to Princess Louise’s (Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders) and served as a company sergeant major. He was awarded the Long Service & Good Conduct Medal.

James Sergeant married Mary Crozier at Newmills Presbyterian Church on 26 January 1927. He died on 1 June 1964, aged 78.

His medals group comprises: 1914-15 Star; British War Medal 1914-20; Victory Medal; General Service Medal 1918-62 with clasps ‘IRAQ’ and N. W. PERSIA’; and Army Long Service & Good Conduct Medal.

Private Robert Sergeant

16/156 Private Robert John Sergeant, The Royal Irish Rifles & 143623 Royal Army Medical Corps

Robert John Sergeant enlisted on 16 November 1916 at Lurgan and, like his brother George, found himself in the 16th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (2nd County Down). He landed in France on 2 October 1915.

He served with 36th (Ulster) Division’s pioneer battalion in France and Flanders, in No. 2 Company, until he was wounded on 3 August 1917 (his only previous injury being a sprained toe in January that year).

No. 2 Company, 16th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (2nd County Down) (Pioneers)

The Third Battle of Ypres began on 31 July and, after the initial attacks that morning, 16th Royal Irish Rifles—at this stage under the orders of the Chief Engineer of XIX Corps—was one of the pioneer battalions ordered to prepare the way for further advance. For five days the Battalion laboured under shellfire and rain to rebuild a roadway near Wieltje, where it crossed the captured enemy front line. The lack of progress by the infantry meant that the enemy’s guns were well within rage and, coupled with the weather, conditions were grim. In the midst of this Private Robert Sergeant was shot in the right leg.

He was treated in hospital in France before sailing from Boulogne to England. He arrived at Western General Hospital at Fazakerley in Liverpool on 8 August 1917 (from when he was held on the strength of the Royal Irish Rifles Depot). Four months later he was assessed fit enough to join one of the Royal Irish Rifles’ reserve battalions and he arrived at 18th (Reserve) Battalion on 23 December 1917.

His wounds proved too much, however, and he was not able to return to duty as an infantryman. He transferred to the Royal Army Medical Corps (143623, Private) on 14 April 1918 and served the rest of the war in England with 20th Company, which supported the military hospital at Tidworth. He was discharged to the Class Z Reserve on 21 May 1919; his wound attracted a pension.

Robert Sergeant married Margaret McCreanor (his sister-in-law; the sister of the wife of his brother George) at Tullylish parish church on 11 July 1924. He died at Gilford on 1 May 1967. His wife died on 2 December 1988.

His medals group comprises: 1914-15 Star; British War Medal 1914-20; and Victory Medal.

1740 Bombardier Samuel Sergeant MM, Canadian Field Artillery

Private Samuel Sergeant, Canadian Expeditionary Force

This account is incomplete due to the process to digitise Canadian service records—it will be updated when his service record becomes available.

Prior to the war Sam Sergeant served with Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) Special Reserve. On 15 March 1911 he emigrated to Canada and settled in Oxford County, Ontario. Soon after the outbreak of war, on 20 November 1914, he enlisted in Toronto for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He served initially with the Canadian Medical Corps (1740, Private) but later transferred to the Canadian Field Artillery.[6]

Canadian Army Medical Corps

In France, Acting Bombardier Sam Sergeant served with 2nd Canadian Division Artillery, attached to the Trench Mortar Group.[7] During the Canadian Corps attack at Vimy in April 1917 he earned the Military Medal:

During VIMY operations terminating on April 8th 1917. This N.C.O. acted as linesman and superintended the maintenance of it in the Forward Area. Time and again he prepared broken wire under very heavy shell fire, displaying great courage and devotion to duty.[8] [9]

On 13 November 1917 Samuel Sergeant married Hester ‘Essie’ McGuinness at St Pauls Church of Ireland, Gilford.[10] Samuel Sergeant died on 19 November 1977 at Tillsonburg, Ontario and was buried in Tilsonburg Cemetery. His wife died in 1984, aged 90.

His medals group comprises: Military Medal, GVR; 1914-15 Star; British War Medal 1914-20; and Victory Medal.

13/498 Private Thomas Henry Sergeant, The Royal Irish Rifles

Private Thomas Sergeant

Thomas Henry Sergeant enlisted in mid-September 1914, aged 16. He joined the 1st County Down Battalion in the 2nd Brigade of the Ulster Division and began his training at Clandeboye Camp at the end of the month. That Battalion became 13th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (1st County Down). Tom Sergeant trained at Clandeboye and at Seaford in Sussex with ‘D’ Company before landing in France in 108th Infantry Brigade, 36th (Ulster) Division on 5 October 1915.

The Inspection of 36th (Ulster) Division by King George V

He was killed in action on 1 July 1916, aged 18, on the left flank of the attack by 36th (Ulster) Division at Thiepval. The Battalion’s casualties were severe. In his account of the battle Martin Middlebrook notes that the Battalion suffered 595 casualties that day; an awful total surpassed by only five other battalions of the more than 80 that took part in the attack.[11]

‘D’ Company provided a flank guard on the far left of the attack out of Thiepval Wood. It recorded 155 casualties—18 killed in action (including Thomas Sergeant), 60 men wounded (one of whom is noted as dying of wounds), seven men wounded and missing, and 70 men missing (most of whom were killed in action).[12]

The only officer of the Battalion to survive the attack was Second Lieutenant Marcus Fullerton of ‘D’ Company.[13] His account of the Company’s attack is in the Battalion’s war diary (a full account of the Battalion’s action may be found by following the link to the right.):

In the advance 14, 15, 16 Platoons reached the sunken road with few casualties, but from there to A1 line, we lost very heavily. I (2nd Lt Fullerton) arriving there with about 16 men, we then proceeded to bomb dugouts from there to the left for about 150 yards & we took about 70 prisoners. Then we were held up by a bombing party of the enemy, but held on and succeeded in gaining another 50 yards. Owing to our bombs giving out we had to barricade ourselves, & signaled for bombs and reinforcements but the enemy started to bomb us & we withdrew up the trench & barricaded ourselves again, but the enemy still continued to bomb us & I, having only a few men left, we had to withdraw back into our own lines.[14]

In the advance 14, 15, 16 Platoons reached the sunken road with few casualties, but from there to A1 line, we lost very heavily. I (2nd Lt Fullerton) arriving there with about 16 men, we then proceeded to bomb dugouts from there to the left for about 150 yards & we took about 70 prisoners. Then we were held up by a bombing party of the enemy, but held on and succeeded in gaining another 50 yards. Owing to our bombs giving out we had to barricade ourselves, & signaled for bombs and reinforcements but the enemy started to bomb us & we withdrew up the trench & barricaded ourselves again, but the enemy still continued to bomb us & I, having only a few men left, we had to withdraw back into our own lines.[14]

Private Thomas Henry Sergeant has no known grave and he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, Pier and Face 15 A and 15 B.

Thomas Sergeant on Thiepval Memorial

His medals group comprises: 1914-15 Star; British War Medal 1914-20; and Victory Medal.

Acknowledgements:

William Moffett for genealogy information and photographs of the Sergeant brothers.

The Sergeant family for photographs of the Sergeant brothers.

1. (Back) Samuel (13 Dec 1856 – 1 Jun 1903); Margaret Ann (née Sands) (18 December 1861 – 12 July 1938); Mary Jane (12 March 1883 – 20 November 1971); Joseph (7 May 1884 – 19 May 1960); James (11 August 1885 – 1 June 1964); Thomas (born and died in 1886); William H (23 June 1887 – 31 August 1959); Eliza (5 October 1889 – 19 June 1973); Samuel (19 November 1891 – 19 November 1977); Robert John (September 1893 – 1 May 1967); George Edward (21 December 1896 – 22 October 1935); Thomas Henry (9 June 1898 – 1 July 1916); Margaret Ann (24 July 1899 – 26 November 1969); and Lewis Alfred (14 June 1901 – 1972).

2. (Back) White, S N. (1996). The Terrors. 16th (Pioneer) Battalion Royal Irish Rifles. Belfast: The Somme Association. p 1.

3. (Back) The Class Z Reserve was established on 3 December 1918 to ensure that those who had been engaged for the duration of the war remained available for service in the event of the Armistice failing. It ceased to exist on 31 March 1920 and the men of the Class Z Reserve were discharged as of that date.

4. (Back) The 1914-15 Star was issued in the name ‘Sergent’.

5. (Back) For a short history of the 5th (Service) Battalion see: Johnson, F W E (Foreword). (1919). A Short Record of the Services and Experiences of the 5th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers in the Great War. Naval & Military Press Reprint, 2009.

6. (Back) His service record is being digitized and is not yet available.

7. (Back) The Trench Mortar Group comprised: ‘V’ Canadian Heavy Trench Mortar Battery, and ‘X’, ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ Canadian Trench Mortar Batteries.

8. (Back) London Gazette 9 July 1917. Issue 30172, p 6843.

9. (Back) See also: Library and Archives Canada. Honours and Awards Citation Cards. Accession 2004-01505-5. Volume 60. Item 97603.

10. (Back) The birth certificate for Hester McGuinness records her name as ‘Esther McGuiness’.

11. (Back) Middlebrook, M. (2006). The First Day on the Somme. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. Appendix 5, p 330. Note, however, that official casualty numbers for the first day of the Battle of the Somme are not always accurate.

12. (Back) The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO). WO95/2506-3. War Diary of 13th Royal Irish Rifles.

13. (Back) Marcus Fullerton was born in Donaghadee, County down in 1892. He was commissioned into The Royal Irish Rifles on 23 August 1915 and joined 13th Royal Irish Rifles in France in February 1916. He subsequently transferred to The King’s African Rifles and served with the 4th Battalion.

14. (Back) TNA. PRO. WO95/2506-3. Op. Cit.

February 19, 2015

‘Sacrifice‘ – My New Project

The Canadian Cross of Sacrifice at Arlington National Cemetery

During the First World War the American Expeditionary Force sustained over 53,000 battle deaths and over 63,000 non-combat deaths. The influenza pandemic in late-1918 and early-1919 alone claimed more than 45,000 American soldiers and sailors in Europe and in the United States.

These men were not the only American soldiers to die in the war.

From the earliest days of the war, American citizens volunteered—with men of other nations resident in the United States—for service with the Imperial forces of the British Empire. Even after the entry into the war of the United States in April 1917, American men enlisted into the British Army, the Canadian Expeditionary Force and, to experience a new mode of warfare, the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Air Force.

The Graves of Private J Schofield, Writer T H Symons and Deck Hands H Thomas and W Kelly

Those who died serving with the Imperial forces are commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. In the United States there are 362 casualties of the First World War commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in cemeteries across 42 states. Many are United States citizens, others are citizens of the countries of the British Empire who had emigrated here, and a few are from other countries in Europe. Some died in France, Flanders, the United Kingdom and Canada and their remains were repatriated. Some were members of the Royal Navy, British Army and Royal Air Force who died whilst serving in the United States.

Organised by State, Sacrifice aims to commemorate each of these men by presenting a short biography of each soldier, sailor or airman as a contribution to this centennial period.

All of the stories previously hosted here on my blog have now moved to the project’s website. Please visit Sacrifice.

The graves of Captain Angus Alexander Mackintosh of Mackintosh, younger; Major Hon. Charles Henry Lyell; and Captain Walter Frederick Fitch MC

February 9, 2015

Private John Paul Mantell

This is part of a series of essays about the First World War casualties commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Virginia.

The grave of Private John Paul Mantell

There is little information available to complete the service record of Private John Paul Mantell—the little that is available is difficult to substantiate.

John Paul Mantell was born about 1882 at Bowling Green, Kentucky.[1] He was a civil engineer by profession[2] and married to Augusta (née Hageman).[3] The family lived in Venice, Los Angeles, California, where their son, John William, was born in 1915.[4]

He enlisted in New York[5]—the British recruiting office there opened in June 1917. There is no record of his service outside the United Kingdom but he may have joined the Tank Corps[6] before joining ‘C’ Company, Inns of Court Officer Training Corps on 22 February 1918 (12641, Private).[7] Prior to being commissioned, he fell ill with pneumonia in early June 1918 and he died on 9 June, aged 36, in Frensham Hill Military Hospital, four days after being admitted.[8]

Private Mantell was buried initially in Bordon Military Cemetery.

After considerable, and often bitter, debate the law allowing the repatriation of United States war dead was signed by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919. The law entitled the next of kin to choose between permanent interment in an American military cemetery on foreign soil, repatriation of the remains to US soil for interment, or repatriation of the remains to the individual’s homeland or that of their next of kin.

John Paul Mantell’s remains were returned to the United States and reinterred in Arlington National Cemetery (Section 18, Grave 561) on Friday 5 November 1920.[9] The detail of this interment was only registered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in February 2007. Prior to that Private Mantell had been commemorated on The Maidenhead Register.[10]

1. (Back) London Regiment, Honourable Artillery Company Infantry, Inns of Court Officers Training Corps. (1921). Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914-1919. Part 76. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

2. (Back) Death Certificate. (1918). John Paul Mantell. General Register Office.

3. (Back) Soldiers’ Effects Records. (1901-60). Record 770445 – Mantell John Paul. National Army Museum, London.

4. (Back) Fourteenth Census of the United States. (1920). Venice, Los Angeles, California. Records of the Bureau of the Census. National Archives, Washington DC.

5. (Back) London Regiment. Op. Cit.

6. (Back) Interment Control Form. (1920). Mantell, J P. Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985. The National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

7. (Back) Errington F H L (Ed). (1922). The Inns of Court Officer Training Corps During the Great War. London: Printing Craft. p 251.

8. (Back) Death Certificate. Op. Cit.

9. (Back) Interment Control Form. Op. Cit.

10. (Back) The Maidenhead Register records the names of all non-Commonwealth foreign nationals who died serving as members of Commonwealth Forces and whose remains were repatriated. The new graves of these men have not been identified. The register contains the records of 87 casualties, 86 from the Second World War and one from the First World War: 288796 Corporal John Henry Dorman, Royal Air Force, an American from Illinois, who died in an accident on 21 June 1918 serving with No. 14 Training Depot Station, at RAF Lake Down near Amesbury.

Lieutenant William Strong

This is part of a series of essays about the First World War casualties commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Virginia. This account is incomplete, however, due to the process to digitise Canadian service records—it will be updated when his service record becomes available.

Lieutenant William Strong, Canadian Machine Gun Corps

‘This is a fight for humanity and I want to be in it.’[1]

William Strong came from prominent family in Washington DC—his paternal grandfather, also William Strong, was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.[2] His maternal grandfather, John Watkinson Douglass, had been President of the Board of Commissioners for Washington DC, as had his uncle, Henry Brown Floyd MacFarland. Reportedly, William Strong was the first man from Washington DC to volunteer to fight. He served with the Canadian Machine Gun Corps in France, was gassed and died in 1919.

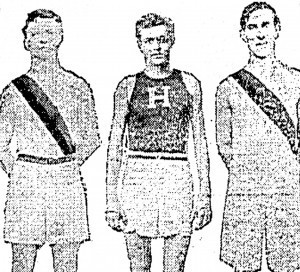

William Strong (centre), Princeton Cross Country, 1908

William Strong was born on 20 August 1887, in Washington DC, the only child of William Newton Strong, a barrister, and Josephine Strong (née Douglass), who had married in November 1886 after a long engagement. In June 1892, two months before Strong’s fifth birthday, his father died. Strong Jr attended the very best of schools—initially the prodigious Sidwell Friends School in Washington DC and then Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. He graduated from Princeton University in 1911 and from George Washington University Law School in 1912. Like his father and grandfather, he became a lawyer—he went to work in the legal department of the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Co.[3]

‘Billy’ Strong volunteered early in the war to fight with the Imperial forces, against the wishes of his friends, although the family, who had strong social ties with Canada, supported him. He enlisted in Toronto on 27 January 1915, and was reported as the first man from Washington DC to do so. In a letter written in the spring of 1919 to the conservative magazine Harvey’s Weekly he signed himself ‘one of America’s advance guard in the great war.’[4] He joined the Eaton Motor Machine Gun Battery in the second Canadian contingent as a Private with the regimental number 849.

After a period of training in Canada, the Battery moved to England and undertook further training at Shorncliffe in Kent before landing in France at the end of February 1916. The absence of his service record makes it difficult to confirm Stong’s movements over the next year or so but his is mentioned in a number of newspaper reports and magazine articles. A few days after his arrival in France, he was evacuated to England having suffered shell-shock when buried in a shelled dug-out.[5] After his recovery and attendance on machine gun training courses, he was posted to 7th Canadian Machine Gun Company in 7th Canadian Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division. He served with this unit until commissioned into the Canadian Machine Gun Corps on 27 June 1916, when he was posted to 11th Machine Gun Company in 11th Canadian Brigade, 4th Canadian Division.

While serving with 11th Machine Gun Company Strong was gassed in March 1917. He subsequently contracted pleurisy in May for which he was treated at a hospital in London. His mother sailed to England to join him, arriving on 3 July at Liverpool on the armed passenger liner SS St Louis. Unfit for further duty, Lieutenant Strong was sent home from Liverpool on the hospital ship SS Araguaya,[6] arriving in Quebec City on 25 September. His mother arrived at Halifax the same day aboard the troopship SS Justicia.[7]

Mother and son journeyed to the summer home of his mother’s sister, Mrs Henry McFarland, at Cap a L’Aigle in Quebec, where he continued his convalescence until the autumn, when he entered the Laurentian Chest Hospital at Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts—well known for its clean air and for the treatment of tuberculosis. Early in the summer of 1918 when his condition had improved, Strong returned to Cap a L’Aigle and it seemed that he had beaten the disease but he was struck down by influenza, which set back his recovery considerably. He returned to the Laurentian Chest Hospital at Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts. In October 1919, in the hope that drier air would enhance his chances of recovery, he moved with his mother to Pasadena in California.

It was there that William Strong died of tuberculosis on Sunday 21 December 1919, aged 32. His body remained in California until the spring of 1920 when it was brought back to Washington DC.

His funeral service was held at 5.00pm on 10 April 1920 at the Church of the Covenant. The pulpit, like his casket, was draped with British and American flags and a contingent of Canadian officers and soldiers acted as pall bearers.

The grave of Lieutenant William Strong

William Strong was buried in Arlington National Cemetery (Section 3, Grave 4113-NH) on 12 April. His grave was originally marked with a private memorial, which has since been replaced by a Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone.

Josephine Stone died on 8 May 1938, aged 77, and, on 10 May, was buried with her son; an stone slab inset at the foot of the grave commemorates her burial.

The gravestone for Josephine Douglass Strong in Arlington National Cemetery

William Strong is commemorated in the Memorial Atrium in Nassau Hall, Princeton and the Class of 1911 established the William Strong Memorial Scholarship in his memory. He is commemorated on page 543 of the Canadian Book of Remembrance.

1. (Back) ‘Lieut. W. Strong Jr. Dies in California.’ (23 December 1919). The Evening Star. p 3.

2. (Back) Justice William Strong was born on 6 May 1808 in Connecticut and graduated from Yale University in 1828. In 1846, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives as an abolitionist Democrat and served two terms. He was elected to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1857, where he served until 1868. Following the death of Edwin Stanton, four days after his confirmation by the United States Senate, Strong was nominated for the United States Supreme Court; he was sworn in on 14 March 1870.He served as an Associate Justice until 14 December 1880, when he retired and returned to private practice. He died at Lake Minnewassa in New York on 19 August 1895, aged 87.

3. (Back) ‘The Alumni.’ (14 March 1918). Princeton Alumni Weekly. Volume 14, No. 23, p 447.

4. (Back) ‘Your Monument – If You Believe’. (19 April 1919). Harvey’s Weekly. Volume 2, number 16, p 14.

5. (Back) Although his injuries and hospitalisation are mentioned in various newspaper reports, a summary of his service may be found in the Princeton University magazine: ‘The Alumni.’ (21 January 1920). Princeton Alumni Weekly. Volume 20, No. 15, p 362.

6. (Back) HMHS Araguaya was one of five ships chartered by Canada for use as hospital ships—the others were Essiquibo, Llandovery Castle, Letitia, and Neuralia. The SS Araguaya was owned by the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co Ltd until 1926. By 1940 she was in use with Compagnie Générale Transatlantique as the SS Savoie II. She was sunk during the Battle of Casablanca on 8 November 1942 by USS Massachusetts.

7. (Back) SS Justicia was sunk by UB-64 and UB 124 on 19/20 July 1918 off the coast of Scotland while travelling unladen to New York.

February 5, 2015

Private Charles Philip Gruchy

This is part of a series of essays about the First World War casualties commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Virginia. This account is incomplete, however, due to the process to digitise Canadian service records—it will be updated when his service record becomes available.

The Canadian Book of Remembrance showing the entry for Private Charles Philip Gruchy

Charles Philip Gruchy is typical of many of the men from the United States and Canada who are commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in the United States. He served in France, was wounded and succumbed to illness after the war; his death being attributable to his war service.

He was born at D’Escousse on Isle Madame in Nova Scotia on 12 June 1880.[1] His father, Peter William Gruchy, a merchant and trader, married his mother, Eliza Lucy (née Ward), in 1874. They had eight children, of which only three—Charles and his sisters Nellie and Violet—survived beyond childhood.[2]

After leaving school, Charles Gruchy worked as a bank clerk and he served for three years with 17th Field Battery, Canadian Artillery in the Non-Permanent Active Militia.

He first attested for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force on 22 September 1914, being allocated the regimental number 7236. From his attestation documents, it appears that he was not enlisted at that time—he was enlisted on 20 October 1916. He was posted to the 12th Reserve Battalion at the the Canadian Training Depot at Tidworth in Wiltshire.

At some time in early 1917 he was posted to the 3rd Battalion (Toronto Regiment), Canadian Infantry in 1st Canadian Brigade, 1st Canadian Division. It is not known when he arrived in the Battalion and, therefore, whether or not he took part in the attack at Vimy in April 1917.

On 10 July 1917, the Canadian Corps moved farther north to replace the British I Corps at the former coal-producing city of Lens. The Corps Commander, Lieutenant General Arthur Currie, had been ordered to capture the town but had found agreement that Hill 70 north of the town should be the Canadian Corps’ objective. The attack was planned for late-July but was postponed due to bad weather.

Charles Gruchy, by now appointed as a Lance Corporal in C Company, and the men of the 3rd Battalion spent July in support, although there were a few casualties on working parties. On 10 August the Battalion moved into the line at Loos for the first time. The Battalion position was at ‘Le Bis 14’, a mine-head 1,500 yards north-east of the town. The trenches here were in poor condition, many being shin-deep in water. C Company was in the centre of the Battalion’s position with A Company on its right and D Company on its left. The relief and the first hours in this postion were not without incident—six men were wounded during the relief (Private George Ballinger later died of his injuries) and later Private Toso Santo was killed and one man wounded when an artillery round dropped short.[3]

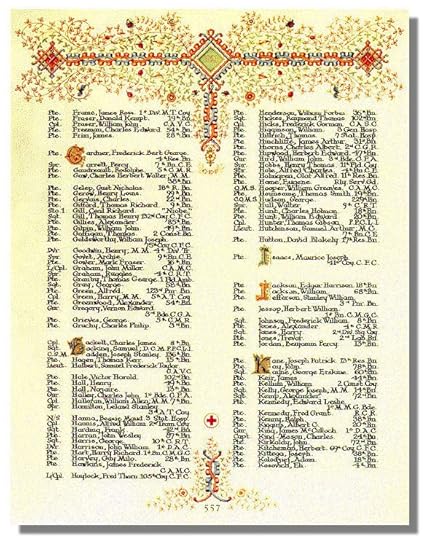

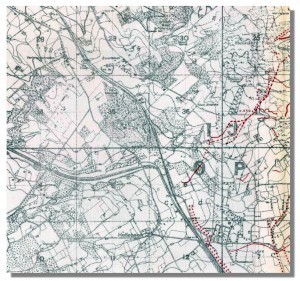

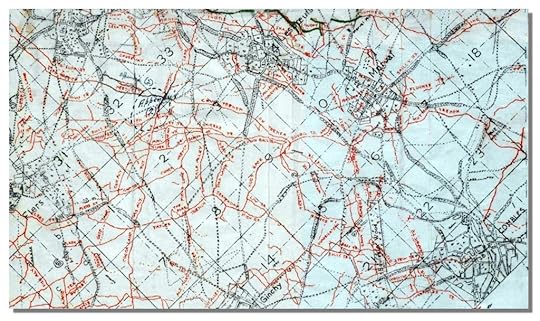

The positions of ‘A’, ‘C’, and ‘D’ Company, 3rd Battalion, Canadian Infantry on 12 August 1917

From the war diary entry of 12 August:

‘Night passed quietly, our patrols active without meeting any opposition from the enemy. 4 O.R. wounded in C Company. Capitan W.B. Woods returned from leave. Lieut. J.K. Gillespie to First Army Rest Camp. Gas attack by 2nd Canadian Division on our right about 2.20 a.m., effects felt very strongly by D Company, who were forced to put on their box respirators for 15 minutes. Band to 1st Canadian Infantry Brigade School. Trenches cleared from 2.00 p.m. to 6.00 p.m. to permit heavies to shoot on enemy front line. Weather – fine.[4]

One of the men wounded on 12 August was Lance Corporal Gruchy.[5] He was shot in the right thigh, causing a compound fracture of his right femur. He was evacuated through the medical system to hospital in England, where he remained in hospital and in convalescence until he sailed home on the hospital ship SS Araguaya,[6] arriving at Portland, Maine on 17 August 1919.[7]

3001 Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia

After he was demobilised Charles Gruchy eventually returned to work as an accountant. He was unmarried. His sister, Violet, married Kenneth Everet Finlay in 1912. In 1916 she, her husband, son, and mother, Mrs Eliza Gruchy, emigrated to the United States, firstly to Milton, Pennsylvania before settling in Richmond, Virginia at 3001 Monument Avenue. Sometime after April 1920, Charles Gruchy moved in with them.

He fell ill with tuberculosis and was treated at United States Public Health Service Hospital No. 60 at Oteen, North Carolina from 3 July 1921. He died there at 5.00pm on 5 July 1921 from chronic pulmonary tuberculosis; he also suffered from ankylosis in his right knee and chronic myocarditis. His death was determined as attributable to his war service. He was buried at Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Lot 81. Initially an Imperial War Graves Commission Stone was declined and the grave was marked with only a private memorial. A Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone has since been placed at his grave. Both it and the private marker read: ‘I thank God for every remembrance of thee.’

The grave of Charles Philip Gruchy

The original grave marker for Charles Philip Gruchy

Source:

The transcribed records of St John’s Anglican Church, Arichat.

Library and Archives Canada. RG9-III-D-3. War Diaries Textual Record. 3rd Canadian Infantry Battalion. June 1917 – February 1919.

1. (Back) St John’s Anglican Church, Arichat, Baptismal Records. This is at odds with his attestation and his death certificate, which record his year of birth as 1882. The baptismal record is, however, clear that he was born on 12 June 1880 and baptised on 13 July 1880. His original grave stone also records a birth date of 12 June 1882. See also note 2 below re his siblings.

2. (Back) St John’s Anglican Church, Arichat, Baptismal and Cemetery Records. Peter William Gruchy was born at D’Escousse on 30 January 1851. He died on 21 May 1913, aged 78. The other seven children were: Eva Weston (born 8 November 1875, died 9 April 1876); Gordon Dumarseq (born 1 July 1877, died 13 April 1881); Ellen ‘Nellie’ (born 18 August 1878); Martha Weston (born January 1882, died 20 March 1885); Edith (born 17 August 1884, died 17 September 1884); Violet Beatrice (born 24 August 1886); and Winifred Aldon (born 16 October 1888, died 2 September 1889). The children who died in childhood and their father, who died on 21 May 1913, are buried in St John’s Anglican Cemetery, Arichat.

3. (Back) Library and Archives Canada. RG9-III-D-3. War Diaries Textual Record. 3rd Canadian Infantry Battalion. August 1917, p 6.

4. (Back) Ibid.

5. (Back) Library and Archives Canada, Op. Cit. p 14. The others recorded as wounded were: 237315 Private Frederick Taylor (later awarded the Military Medal and promoted to Sergeant) and 201274 Private James Cecil Spivey. The fourth man is not recorded and it is assumed that his wounds were slight and that he remained at duty.

6. (Back) HMHS Araguaya was one of five ships chartered by Canada for use as hospital ships—the others were Essiquibo, Llandovery Castle, Letitia, and Neuralia. The SS Araguaya was owned by the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co Ltd until 1926. By 1940 she was in use with Compagnie Générale Transatlantique as the SS Savoie II. She was sunk during the Battle of Casablanca on 8 November 1942 by USS Massachusetts.

7. (Back) Library and Archives Canada. RG76-C. Department of Employment and Immigration fonds. Passenger Lists, 1865–1935.

February 2, 2015

The Military Attachés

This is part of a series of essays about the First World War casualties commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Virginia.

The first British military attaché in Washington DC was Major General J D McLachlan DSO, who had taken up his post in September 1917.[1] He was supported by an experienced and well-connected staff. When influenza struck—no discriminator between rich and poor, or the titled and working class—he lost two of his small team within days.

Major Hon. C H Lyell and Captain A A Mackintosh of Mackintosh, younger

Major the Honourable Charles Henry Lyell

Charles Henry Lyell was born in London on 18 May 1875, the son of Leonard Lyell, a Scottish, Liberal Member of Parliament, who became the 1st Baron Lyell of Kinnordy on 4 July 1914. His mother, Mary Stirling, was Canadian and he had two younger sisters.

Lyell was educated at Eton and New College, Oxford. Upon leaving Oxford he became a private secretary before standing successfully for election to represent East Dorset in a by-election in 1904. He was re-elected in the 1906 general election and was appointed as Parliamentary Private Secretary to Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary. In the general election of 1910 he stood to represent Edinburgh West but he was not elected. At a by-election in April that year he was successful in being elected for Edinburgh South and won re-election in the second general election of 1910 that was held in December. In February 1911 he was appointed as the Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Prime Minister, H H Asquith.

Miss Rosalind Watney and The Hon. Charles Lyell

The Hon. Charles Henry Lyell married Miss Rosalind Margaret Watney at Cornbury Park, Oxfordshire on 18 May 1911. Their first child, a daughter, Margaret Laetitia, was born on 22 April 1912 and their second child, a son, Charles Anthony, was born on 14 June 1913.

Charles Lyell’s military career began in the Volunteer Rifle Corps—he served as a Second Lieutenant in 4th (Eton College) Volunteer Battalion, The Oxfordshire Light Infantry until he resigned his commission on 21 November 1894. Lyell was commissioned subsequently into The Forfar and Kincardine Royal Garrison Artillery (Militia) and promoted to Lieutenant on 1 August 1900. He served until 1908 when he transferred to the Reserve of Officers but continued his association with the volunteer forces as vice-chairman of the Forfarshire Territorial Association.

After war broke out, he was commissioned into the Highland (Fifeshire) Royal Garrison Artillery (Territorial Force) as a Captain on 16 September 1914. 1/1st Highland (Fifeshire) Heavy Battery was originally part of 51st (Highland) Division, Territorial Force but when the Division sailed for France, the Battery, equipped with four 4.7-inch guns, was transferred to IV Heavy Brigade.[2]

Lyell was promoted to Major on 19 April 1915 and he commanded the Battery from its arrival in France on 4 May. In November 1916 he was badly burned on the face and hands following an accident on a gun line and was forced to relinquish his command; he was mentioned in despatches.[3] In May 1917, he stood down as a Member of Parliament, having been appointed Steward and Bailiff of the Three Hundreds of Chiltern.[4]

Major the Hon. Charles Lyell was formally appointed as the Assistant Military Attaché in Washington DC on 22 December 1917, the day he sailed on the SS Baltic from Liverpool. He arrived in New York on 26 December, and took up his post on 2 January 1918.

Captain Angus Alexander Mackintosh, younger of Mackintosh

Angus Alexander Mackintosh, younger of Mackintosh was also a Scot. He was born on 6 August 1885 at Moy Hall, Inverness—the seat of the chiefs of the Clan Mackintosh since the 14thC. His father, Alfred Donald Mackintosh of Mackintosh, was the 28th Chief. His mother, Harriet Diana Arabella Mary Richards, was from a Glamorganshire family. Mackintosh younger grew up at the family home at Cottrell, St Nicholas, in Glamorganshire and was sent to school at Wixenford and Eton.

He was commissioned into the Royal Horse Guards, ‘The Blues’, on 4 July 1906 and promoted to Lieutenant on 5 July 1908. After a period of regimental duty at Windsor, which included the coronation of King George V, on 22 September 1913 he was appointed as the aide-de-camp to General Sir Arthur Paget, Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in Ireland. This was a time of turmoil in Ireland and Mackintosh witnessed at first hand the role of Paget in the Curragh mutiny, although there is no indication of what his feelings were on the matter.

Captain Angus Alexander Mackintosh of Mackintosh, younger

After war broke out Mackintosh returned to his Regiment at Combermere Barracks, Windsor and took command of a troop. The Royal Horse Guards joined 7th Cavalry Brigade, in 3rd Cavalry Division, at Ludgershall before embarking on the SS Basil (regimental headquarters and a squadron of The Life Guards) and the SS Cardiganshire (three squadrons of Royal Horse Guards), destined for Belgium. Lieutenant Mackintosh landed with his troop at Zeebruge on 8 October, concentrating with the rest of the Regiment east of Bruges. By 14 October the Regiment was in Ypres and it then took part in the operations east of the city. On 17 October his squadron, commanded by Captain Lord Alastair Innes-Ker, conducted a reconnaissance of Roulers, which was found to be clear of the enemy. Mackintosh was posted at the railway station with his troop, which was subsequently attacked by a squadron of enemy hussars. The enemy were beaten off ‘with severe casualties’.[5]

Klein Zillebeke and Hollebeke Chateau

By 22 October the Regiment was in the area of Klein Zillebeke, where 7th Cavalry Brigade alternated with 6th Cavalry Brigade in the rudimentary trenches on the Zandevoorde Ridge. This position was held until 30 October when the strength of the enemy attack forced the squadrons on the ridge back to Klein Zillebeke. Two squadrons of The Blues were ordered to reinforce the Royal Dragoons, who held Hollebeke Chateau, south west of Klein Zillebeke. It was in this action Lieutenant Mackintosh was shot in the chest and severely wounded—one of 56 casualties from The Blues (three killed, 19 wounded and 34 missing).[6] He was evacuated to 7th Stationary Hospital at Boulogne, where he was treated before being sent to hospital in England in mid-November.[7]

During his stay in hospital he had been promoted to Temporary Captain (1 November 1914) and promotion to Captain followed on 1 February 1915. After six months in hospital and convalescing at home he was posted to Headquarters Southern Command as a Grade 3 staff officer. In September 1915, Captain Angus Mackintosh was appointed as the aide-de-camp to Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, the Governor General of Canada. He arrived in Canada on board the SS Missanabie[8] on 3 October 1915 and took up his post as one of four aides-de-camp at Government House.

On 25 October 1916, having been nominated by Prince Arthur, Captain Mackintosh was made an Esquire in the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem in England.[9]

Prince Arthur had served as Governor General since 1911 and in November 1916 he was succeeded by Victor Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire. Mackintosh remained in post as one of his aides-de-camp. The Duke of Devonshire was, naturally, accompanied to Canada by his family.

The Wedding of Captain Angus Mackintosh and Lady Maud Cavendish

His second child and eldest daughter, Lady Maud, was 20 years old and she caught the ADC’s eye.[10] On 31 August 1917, a little under a year after they had met, their marriage was announced, by which time Lady Maud had turned 21. The couple were married on 3 November 1917, at Christ Church Cathedral in Ottawa. This was a society wedding the like of which had not been seen in Canada. Lady Maud was the first child of a Governor General to be married in the dominion and the occasion was the society event of the decade.

The couple set off for the first part of their honeymoon at nearby Meech Lake before journeying to California. By early January the couple had established themselves in Washington DC, where Captain Mackintosh joined the staff of the British Military Mission as the Honorary Assistant Military Attaché on 9 January 1918.

The couple set off for the first part of their honeymoon at nearby Meech Lake before journeying to California. By early January the couple had established themselves in Washington DC, where Captain Mackintosh joined the staff of the British Military Mission as the Honorary Assistant Military Attaché on 9 January 1918.

The first cases of influenza were observed in Washington DC in August 1918. They were initially confined to the naval station and local army camps but by the end of September civilian cases were increasing and in early October schools were closed and four emergency relief stations and an emergency hospital were opened (for whites only; the city’s Black population was not catered for until the end of the month). By early November the epidemic was seen to be in decline and restrictions were lifted but cases increased again in December. The epidemic continued until February 1919 by which time there had been over 33,000 cases and 2,895 deaths. It was ‘one of the more devastating epidemics in the nation’.[11]

In early October 1918 Lyell and Mackintosh fell ill with influenza.

Mackintosh had just returned from Canada. His wife, pregnant with their first child, had returned there in early September, after a summer spent in a cottage at Buena Vista Springs near Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania. She gave birth to their daughter, Anne Peace Arabella, on 24 September 1918 at Cartierville in Montreal and in early October Mackintosh returned to Washington. He fell ill soon after his return and was admitted to Walter Reed General Hospital, Takoma Park, where he died a few days later of pneumonia on Monday 13 October. His wife, recovering from the birth and shocked by his death, remained in Canada and his mother-in-law, the Duchess of Devonshire, travelled immediately to Washington with two of her husband’s aides, Captain M A T Ridley, Grenadier Guards—who had been best man at Mackintosh’s wedding—and Captain W A Clive MC, Grenadier Guards. He was buried with full military honours on Wednesday 16 October in Arlington National Cemetery.

Charles Lyell had also fallen ill with influenza but had not been admitted to hospital. He died—of an embolism, complications of pneumonia—on the following Friday, 18 October, at his apartment at The Brighton Apartments. He was buried alongside Mackintosh at Arlington National Cemetery.

The grave of Major the Hon. Charles Henry Lyell

The grave of Captain Angus Alexander Mackintosh, younger of Mackintosh

Major the Hon. Charles Henry Lyell is also commemorated on the Houses of Parliament War Memorial in Westminster Hall and in The House of Commons Book of Remembrance 1914-1918 and in The House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, MCMXIV-MCMXIX. In Scotland, he is commemorated by the east window at St Mary’s Episcopal Church, Kirriemuir, which was dedicated on Sunday 31 August 1924, and on Kirriemuir War Memorial. He is also remembered on the Mortonhall Golf Club Memorial.

Lyell’s son, Charles Anthony Lyell, succeeded his grandfather to both the baronetcy and barony in 1926. During the Second World War he served with 1st Battalion, Scots Guards. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross on 12 August 1943, for his actions on 27 April at Dj Bou Arara in Tunisa.[12] He is buried in Massicault War Cemetery. He is commemorated on the Marylebone Cricket Club Roll of Honour, on the Kirriemuir War Memorial and on the memorial in Kirriemuir Barony Parish Church. He is also commemorated on a memorial slab at Cumberland Close, Kirriemuir.

In 1937 Lyell’s daughter married The Hon. Francis Alan Stewart-MacKenzie of Seaforth, a pre-war Territorial Army officer in the Royal Regiment of Artillery. He was killed in action in Italy on 11 September 1943 serving with 98th (The Surrey and Sussex Yeomanry Queen Mary’s) Field Regiment. He is buried at Salerno War Cemetery beside his brother, Major the Hon. Michael Victor Brodrick MC, Coldstream Guards, who was killed in action the previous day serving with the 3rd Battalion.

Captain Angus Alexander Mackintosh, younger of Mackintosh is also commemorated on the war memorial in St Nichols, in the Vale of Glamorgan, and on the remote Strathdern War Memorial, Tomatin in the Scottish Highlands.

Lady Maud Mackintosh remarried in 1923. Her husband, Major Hon. George Evan Michael Baillie MC, served with the Royal Horse Artillery during the First World War. On 6 June 1941, Brigadier Hon. Evan Baillie MC, TD died following a medical procedure. Lady Maud served during the Second World War as a Controller with the Auxiliary Territorial Service, for which she was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1945.[13] She died on 30 March 1975.

The medals group of Major the Honourable Charles Henry Lyell comprises:1914-15 Star; British War Medal 1914-20; and Victory Medal with mention in despatches emblem.

The medals group of Captain Angus Alexander Mackintosh, younger of Mackintosh comprises:1914-15 Star clasp with clasp ‘5TH AUG.-22ND NOV. 1914’; British War Medal 1914-20; Victory Medal; and Coronation Medal 1911.

Acknowledgement:

Dr Kerr Fraser for the photograph of Mortonhall Golf Course War Memorial.

1. (Back) Major General James Douglas McLachlan CB, CMG, DSO was born in Samarang, Java on 14 February 1869. Commissioned into The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders in 1891, he took part in the Nile Expedition in 1898 and the battle of Khartoum. He took command of the 1st Battalion in March 1913 and led it to France in the early stages of the war until September 1914, when he was severely wounded. He then commanded 8th Infantry Brigade from October 1915 to March 1916. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (June 1916) and mentioned in despatches twice (January 1916 and June 1916). He served on the staff as a Brigadier General before being appointed as the first wartime military attaché to the United States. He arrived in Washington with his assistant military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel The Hon A C Murray DSO, MP, on 11 September 1917. In-post, he was promoted to Major General. He was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath in June 1918 and a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in June 1919. He relinquished his post in June 1919, and reverted to his substantive rank of Colonel. He was awarded the United States Distinguished Service Medal in July 1919. He died on 7 November 1937.

2. (Back) Part of Southern Group, later No. 1 Group Heavy Artillery Reserve. Later equipped with six 60-pounder guns.

3. (Back) London Gazette 4 January 1917. Issue 29890, p 213.

4. (Back) Members of Parliament are not permitted to resign their seats. The mechanism of appointment to the sinecure post of Steward and Bailiff of the Three Chiltern Hundreds of Stoke, Desborough and Burnham, in the county of Buckingham, mandated that an MP stand down because, by law, he could not hold an office of profit under the Crown.

5. (Back) The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO). (1914-1919). WO95/1156-3. The Royal Horse Guards War Diary.

6. (Back) Op. Cit.

7. (Back) TNA. PRO. (1914-1919). WO95/3988-91. Matron-In-Chief, British Expeditionary Force, France And Flanders War Diary. (This dairy and other notes may be read on Scarlet Finders.)

8. (Back) SS Missanabie was an armed passenger liner of the Canadian Pacific Line, which sailed throughout the war between Canada and Liverpool. On 9 September 1918 she was sunk by U87, 50 miles off the coast of Ireland, with the loss of 45 lives.

9. (Back) London Gazette 27 October 1916. Issue 29804, p 10417.

10. (Back) Lady Maud Louisa Emma Cavendish was born on 20 April 1896.

11. (Back) Here you can read more about the influenza pandemic in Washington DC.

12. (Back) London Gazette 12 August 1943. Issue 36129, p 3625.

13. (Back) London Gazette 1 January 1945. Issue 36866, p 10.

January 21, 2015

Captain Walter Frederick Fitch MC