Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 2

March 17, 2024

Kohima War Cemetery

This is the second short post about Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries visited during a recent visit to India with ‘The Forgotten War Tour’ led by Dr. Robert Lyman MBE and organised by Bertie Alexander of Sampan Travel. (See the posts about Kolkata and Digboi).

Kohima War Cemetery was constructed on the site of the terraced grounds of the residence of the Deputy Commissioner[1] of the Naga Hills, on the slopes below what became known as Garrison Hill during the Battle of Kohima.

The cemetery was designed by C. St. C. R. Oakes, an Advisory Architect to the Imperial War Graves Commission (later Principal Architect) who had served with 72nd Infantry Brigade in the Arakan, for which he had been appointed an M.B.E.[2] A unique aspect of its design was the incorporation of the Deputy Commissioner’s tennis court, around which fierce fighting had taken place in April and May 1944.

The Cross of Sacrifice and the Tennis Court

The inscription inside the shelter at the base of the Cross of Sacrifice reads:

HERE AROUND THE TENNIS COURT OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER LIE MEN WHO FOUGHT IN THE BATTLE OF KOHIMA IN WHICH THEY AND THEIR COMRADES FINALLY HALTED THE INVASION OF INDIA BY THE FORCES OF JAPAN IN APRIL 1944

Buried here are 1,420 Commonwealth war dead, of whom 125 are unidentified. A further 917 Hindu and Sikh soldiers who were cremated in accordance with their faith are commemorated on the Kohima Cremation Memorial

The Cremation Memorial

The missing from the battles in the region are amongst those commemorated on the Rangoon Memorial.[3]

There are eight Royal Signals all ranks buried at Kohima, five of who were killed during the battle, and three who died in hospital in Kohima or elsewhere in the region at other times:

3603687 Signalman FRED HOUGHTON BOYD

3603687 Signalman FRED HOUGHTON BOYD

2nd Divisional Signals

Killed in action on 12 June 1944 during the latter stages of the Battle of Kohima.

2593635 Lance Corporal JOHN ROBERT RITSON DODD

2593635 Lance Corporal JOHN ROBERT RITSON DODD

7th Indian Divisional Signals

Died on 29 November 1944 as the result of an accident.

WE LEAVE HIM IN GOD’S ALL-WISE HANDS AND TRUST HIS PERFECT WILL

2377890 Lance Corporal ARTHUR EAGLE

2377890 Lance Corporal ARTHUR EAGLE

Unit Not Known (formerly 178th Assault Field Regiment Royal Artillery Signal Section, possibly 24th Reinforcement Centre)

Killed in action on 5 April 1944 early in the Battle of Kohima.

AT THE GOING DOWN OF THE SUN AND IN THE MORNING, WE WILL REMEMBER HIM

2365106 Signalman JAMES DUDLEY GREEN

2365106 Signalman JAMES DUDLEY GREEN

2nd Divisional Signals

Killed in action on 19 April 1944 in the Battle of Kohima.

Originally buried at Lancaster Gate, his remains were reinterred on 12 October 1944 at Kohima War Cemetery.

2585775 Lance Corporal THOMAS LUMLEY

2585775 Lance Corporal THOMAS LUMLEY

33rd Corps Signals

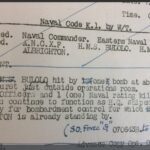

Following a bombing raid at Lancaster Gate on 15 May 1944 during the Battle of Kohima when he was a member of a line party, he died of wounds later that day. Sergeant M. Haythornthwaite, Corporal D. T. Radcliffe and Signalman A. Benson were wounded.[4]

Originally buried near Lancaster Gate, his remains were reinterred on 31 December 1944 at Kohima War Cemetery.

IN LOVING MEMORY OF OUR DEAR SON THOMAS

2362558 Corporal JOHN STANLEY TIPPER

2362558 Corporal JOHN STANLEY TIPPER

2nd Divisional Signals

Initially reported missing, he was killed in action on 17 June 1944 during the latter stages of the Battle of Kohima.

Originally buried along the Kohima-Imphal road just north of Mao Songsang, his remains were reinterred on 20 November 1944 at Kohima War Cemetery.

HE SLEEPS IN THE ARMS OF JESUS; A TRUE BRITISH SOLDIER AT REST

229399 Second Lieutenant GEORGE GREVILLE WILLIAMSON

229399 Second Lieutenant GEORGE GREVILLE WILLIAMSON

Unit Not Known

Commissioned in March 1942, he died on 30 November 1942 as a result of injuries sustained in a road traffic accident on the Dimapur-Kohima road.

Originally buried elsewhere, his remains were reinterred at Kohima War Cemetery.

“BE THOU FAITHFUL UNTO DEATH AND I WILL GIVE THEE A CROWN OF LIFE”

3860831 Serjeant JOHN YATES

3860831 Serjeant JOHN YATES

9th Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section, 5th Indian Division

Died of cerebral malaria on 13 December 1944 in 19th Indian Casualty Clearing Station.

LOVE’S GREATEST GIFT, REMEMBRANCE

Nine soldiers of the Indian Signal Corps are buried in Kohima War Cemetery:

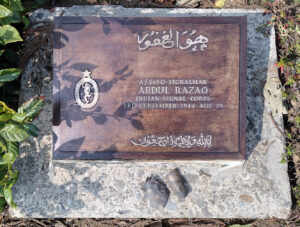

A/5690 Signalman ABDUL RAZAQ

A/5690 Signalman ABDUL RAZAQ

‘R’ Indian Line of Communication Signals, died on 3 September 1944

A/9360 Signalman AHMAD KHAN

7th Indian Divisional Signals, died on 8 October 1944

B/1020 Signalman BOSTAN KHAN

‘R’ Indian Line of Communication Signals, died on 13 June 1942

ISC/16330 Signalman FAQIR MUHAMMAD

ISC/16330 Signalman FAQIR MUHAMMAD

17th Indian Divisional Signals, died on 16 December 1943

ISC/46785 Signalman HAKIM ALI

17th Indian Divisional Signals, died on 2 August 1944

ISC/26083 Signalman MUHAMMAD LATIF

‘R’ Indian Line of Communication Signals, died on 7 June 1942

ISC/14496 Signalman NUR MUHAMMAD

‘T’ Indian Line of Communication Signals, died on 22 November 1944

A/9939 Signalman PREMANANDAN

A/9939 Signalman PREMANANDAN

23rd Indian Divisional Signals, died on 3 November 1943

04747 Labourer RAJ MUHAMMAD

‘R’ Indian Line of Communication Signals, died on 17 May 1942

Soldiers of the Indian Signal Corps commemorated on the Cremation Memorial

Nine soldiers of the Indian Signal Corps are commemorated on the Kohima Cremation Memorial:

ISC/60524 Signalman K. ANANDAN

Unit Not Known, died on 30 January 1944

ISC/58518 Signalman KUMARA VELU

19th Indian Divisional Signals, died on 24 December 1944

ISC/13910 Signalman K. KUNHI RAMAN

19th Indian Divisional Signals, died on 18 December 1944

010001 Labourer PERUMAL

‘R’ Indian Line of Communication Signals, died on 28 March 1944

ISC/36466 Signalman PUSWAMI

48th Light Indian Infantry Brigade Signal Section, 17th Indian Division, died on 21 March 1943

ISC/60166 Signalman RAM PARSHAD

Unit Not Known, died on 8 July 1945

ISC/57132 Signalman SHEO PUJAN

36th Indian Divisional Signals, died on 18 January 1945[5]

ISC/35938 Signalman SUBRAMANIAM

Unit Not Known, died on 30 October 1943

ISC/20162 Signalman SUKUMARA PILLAI

Unit Not Known, died on 18 January 1945

1. (Back) Charles Ridley Pawsey C.I.E., M.C. Later Sir Charles Pawsey C.S.I., C.I.E., M.C.

2. (Back) 45134 Major Colin St. Clair Rycroft Oakes, Royal Regiment of Artillery. M.B.E. (Military Division). Deputy Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General, 72nd Infantry Brigade, 36th Indian Division. London Gazette 8 February 1945; 36928, p. 794. Recommendation: The National Archives, WO 373/80/416.

3. (Back) There are 71 Royal Corps of Signals, 361 Indian Signal Corps, six Burma Army Signals, one Burma Posts and Telegraph Signals, seven East African Corps of Signals, and 14 West African Corps of Signals casualties who died during the Burma Campaign and who are commemorated on the Rangoon Memorial.

4. (Back) 2587910 Sergeant Maurice Haythornthwaite, 2326454 Corporal Dominic Thomas Radcliffe and 2586739 Signalman A. Benson. Sergeant Haythornthwaite and Corporal Radcliffe were mentioned in despatches.

5. (Back) The division became 36th Infantry Division in September 1944.

February 28, 2024

Bhowanipore Cemetery, Kolkata

During a recent visit to India with ‘The Forgotten War Tour’ led by Dr. Robert Lyman MBE and organised by Bertie Alexander of Sampan Travel, I was able to visit the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries in Kolkata and at Digboi in Assam. Here are the Royal Signals casualties that lie in the former, and in the gallery some interesting graves & stories. Thanks to Rabi Singh for the photos I missed.

The Cross of Sacrifice

Bhowanipore Cemetery in Kolkata lies one kilometre south of the Maidan and is accessed from Debendra Lal Khan Road. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission section is at the rear (western) part of the cemetery. In addition to war graves from the First and Second World Wars, it includes over 230 non-World War graves from the 19th and 20th centuries. The CWGC section was established in its present form in the 1950s when graves from other parts of the cemetery were concentrated. It is beautifully tended by the head gardener Rabi Singh.

Head Gardener, Rabi Singh

During the Second World War, No. 47 British General Hospital was in Kolkata from January 1943 to the beginning of February 1945; it was replaced by No. 21 British General Hospital in January 1945. Also established in Kolkata was No. 119 Indian General Hospital (Combined). All of the 15 Royal Signals (and one Indian Signal Corps) casualties died in those hospitals as a result of disease or natural causes, or as a result of accidents in the Kolkata area.

Royal Corps of Signals and Indian Signal Corps

6105402 Driver JOHN HERBERT BUTLER

No. 1 Special Communications Group Signals

Died on 10 March 1944 as a result of an accident.

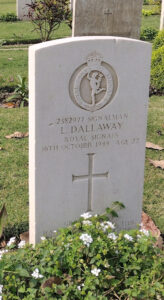

2382977 Signalman LEONARD DALLAWAY

Eastern Command Signals

Died on 16 October 1944, aged 22 as a result of an accident.

GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS, THAT HE GIVETH HIS LIFE FOR HIS FRIENDS

2572014 Lance Serjeant JOHN HARRY DOWNER

Eastern Command Signals

Died on 17 October 1944, aged 24.

IN GOD’S GARDEN OF REST UNTIL WE MEET AGAIN

2593613 Driver GEORGE DALGLISH DUNN

Eastern Command Signals

Died of smallpox on 17 June 1944, aged 25.

GOD’S GREATEST GIFT, REMEMBRANCE. GOOD NIGHT, DADDY

14878720 Signalman RONALD HESKETH

Eastern Command Signals

Reported missing, he was later declared to have died on 8 January 1946, aged 19

as a result of an accident.

THY PURPOSE, LORD, WE CANNOT SEE BUT ALL IS WELL THAT’S DONE BY THEE

2356187 Signalman JAMES KELLY

4th Corps Signals

Died on 28 September 1944, aged 33.

14212248 Signalman EDGAR MARTIN LITTLEJOHN

118th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery Signal Section (at the time the regiment was based in Assam as part of 14th (West African) Anti-Aircraft Brigade)

Died on 13 March 1944, aged 37

“O TRUE, BRAVE HEART! GOD BLESS THEE,

WHERESO’ER IN GOD’S GREAT UNIVERSE THOU ART TO-DAY!”

2385548 Signalman ELISHA LONGDIN

1st Indian Air Formation Signals

A former telegraphist with the General Post Office, he drowned on 30 July 1943, aged 20.

IN THE SWEET BYE AND BYE WE SHALL MEET ON THAT BEAUTIFUL SHORE

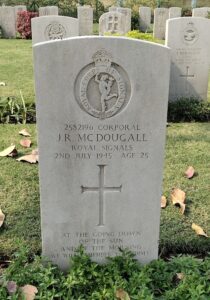

2582196 Corporal JAMES ROBERT MCDOUGALL

17th Indian Divisional Signals

Died of hepatitis and pneumonia on 2 July 1945, aged 25.

AT THE GOING DOWN OF THE SUN AND IN THE MORNING WE WILL REMEMBER YOU, JIMMY

2345086 Signalman ALFRED SIDNEY RICKETTS

No. 98 Telegraph Operating Section, ‘T’ Indian Line of Communication Signals

Died on 30 August 1943.

TOO GOOD IN LIFE TO BE FORGOTTEN BY HIS BROKEN-HEARTED MOM, SISTER AND ALL

ISC/18716 Signalman SELLAPPAN

Indian Signal Corps, Unit Not Known

Died on 21 April 1944, aged 24.

ॐ भगवते नमः (Sanskrit: Om Bhagwate Namah—O my Lord; unto the Supreme Personality of Godhead I offer my respectful obeisances.)

THIS HINDU SOLDIER OF THE INDIAN ARMY IS HONOURED HERE

2342137 Lance Corporal LEONARD WILLIAM SMITH

4th Corps Signals

Died on 28 June 1943, aged 27.

IN LOVING MEMORY OF MY DEARLY BELOVED HUSBAND “IN SPIRIT ALWAYS UNITED”

2593090 Signalman CYRIL LAWRENCE TEAGUE

17th Indian Divisional Signals

Died on 15 June 1945, aged 29.

WITH TENDER LOVE AND DEEP REGRET WE WHO LOVED HIM WILL NEVER FORGET

14274874 Signalman GUY BARRY TEARE

‘O’ Indian Line of Communication Signals

Died on 27 March 1944, aged 20.

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

5192180 Signalman FRANK THOMAS WEAVING

‘L’ Company (Unit Not Known—a unit of the Indian Signal Corps)

Died on 8 December 1942, aged 26.

AT THE GOING DOWN OF THE SUN AND IN THE MORNING WE WILL REMEMBER HIM

2361790 Signalman LEONARD WILLCOX

53rd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery Signal Section

Died on 11 February 1943, aged 26.

“AS WE HAVE BORNE THE IMAGE OF THE EARTHY, WE SHALL ALSO BEAR THE IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY”

Other Graves of Interest

(Details may be found by clicking on the image and interrogating the (i) button.)

London Gazette 28 September 1943; 36185, pp. 4291-4292) for his leadership when his ship, m.v. Medon, was sunk by the Italian submarine Reginaldo Giuliani on 10 August 1942 in the South Atlantic. All of his crew survived and those in his lifeboat were picked up by the Portuguese steamer Luso. All of the crew in three other boats were also picked up by various ships, including the Second Officer and 15 men found by the British merchant ship Reedpool, which in turn was torpedoed and sunk by U-515 on 20 September. They survived this second attack and were picked up the next day by the British ship Millie M. Masher. Chief Officer George Edge and Second Officer John Frederick Fuller were made an M.B.E." data-image-caption="

London Gazette 28 September 1943; 36185, pp. 4291-4292) for his leadership when his ship, m.v. Medon, was sunk by the Italian submarine Reginaldo Giuliani on 10 August 1942 in the South Atlantic. All of his crew survived and those in his lifeboat were picked up by the Portuguese steamer Luso. All of the crew in three other boats were also picked up by various ships, including the Second Officer and 15 men found by the British merchant ship Reedpool, which in turn was torpedoed and sunk by U-515 on 20 September. They survived this second attack and were picked up the next day by the British ship Millie M. Masher. Chief Officer George Edge and Second Officer John Frederick Fuller were made an M.B.E." data-image-caption="Fireman E. G. Cole of the merchant ship Asphalion

" data-medium-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." /> memorial to those who died may be found in St Matthew’s Church, Tay Street, Perth." data-image-caption="

memorial to those who died may be found in St Matthew’s Church, Tay Street, Perth." data-image-caption="Three soldiers of The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment)

" data-medium-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." data-large-file="https://www.nickmetcalfe.co.uk/wp-con..." />

The post Bhowanipore Cemetery, Kolkata first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.

The post Bhowanipore Cemetery, Kolkata first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.

July 10, 2023

Commemorating Royal Signals War Dead – New Page, ‘K’

The Royal Signals casualties whose surnames begin with ‘K’ have now been included on the War Dead page on this website (the document opens as a pdf). The 118 casualties include 34 who were killed in action or died of wounds (the most recent being Sergeant B. R. Keen, 14th Signal Regiment (Electronic Warfare), who was killed in action in Afghanistan in 2007), and 23 men who died as prisoners of war in the Second World War. As is the case across all of these pages over 12.5% of fatal casualties occurred in road traffic accidents, a figure that increases in the modern era reflecting the advances in medical care that reduce the number dying of disease.

Brookwood 1939-1945 Memorial © CWGC

Commemorated on the memorial to the missing of the Second World war are:

Company Quartermaster Serjeant Albert Horace Kemp, 8th Anti-Aircraft Brigade Signal Section, killed with his family at Merstham near Reigate in a bombing raid on 19 April 1941; their remains were never found.

Captain Oliver Cecil Kisch, Air Formation Signals, killed in action and lost at sea on 17 June 1943 when the troopship SS Yoma was sunk on route from Tripoli to Alexandria.

Signalman Robert Wilson Kerr, who drowned in the Firth of Forth on 16 October 1946.

June 28, 2023

Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals

Following the announcement of the Birthday Honours list, I have updated the Addendum to Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals. It includes the awards announced last week and also some new information; in this iteration, more detail on the awards to Company Sergeant Major Grey and Signalman Whitmore, who accompanied the first team into Italian occupied Ethiopia in August 1940.

The pdf is available to download midway down this page.

Military Medal of Haile Selassie I awarded to Warrant Officer Class I T. W. Whitmore

The post Honours, Decorations, and Medals to The Royal Corps of Signals first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.March 25, 2023

The Queen’s Gallantry Medal

Since writing For Exemplary Bravery, the story of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal and its recipients, I have regularly produced an online ‘addendum’ to share information received since publication in 2014 and to record new awards.

Following the accession of King Charles III, the medal was renamed ‘The King’s Gallantry Medal’; but no awards of this medal have been made yet. The final awards of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal were announced in the Civilian Gallantry List of 18 March 2023.

There have been 57 awards of the QGM since January 2014, bringing the total to 1,101—559 to civilians and 542 to military personnel; this includes 19 Bars. Two posthumous awards announced in 2018, one in 2019, and one in 2023 bring the total number of posthumous recipients to 42. The awards to Leading Seaman (Seaman Specialist) S. L. Hughes QGM, Mrs. L. Way QGM and Mrs. A. Bounouri QGM brings the number of female recipients to 27.

Following the announcement of the final awards of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal, I have updated the ‘addendum’, which is free to view and download here.

The post The Queen’s Gallantry Medal first appeared on Nick Metcalfe.October 20, 2022

HMS Bulolo—No. 1 Ship Signal Section, 1942-1945 (Part 2)

Part 1 of this tale covered the period from the formation of No. 1 Ship Signal Section in 1942 until the arrival of HMA Bulolo in Bombay (Mumbai) in September 1943.

HMS Bulolo

HMS Bulolo’s deployment to the Far East in the latter part of 1943 was in preparation for amphibious operations in the late spring of 1944 against Japanese-occupied Sumatra and Malaya (Operation Culverin) and against the Andaman Islands (Operation Buccaneer). The plans were ultimately abandoned but not before No. 1 Ship Signal Section had spent time passing on its experience to new signal sections of the newly-formed 218 Signal Assault Wing.[1] In October, Bulolo took part in a command post exercise with the staff of 33rd Indian Corps (Exercise Otter) that simulated a divisional landing, with the staff from 36th Indian Division and 29th Infantry Brigade on board HMS Keren—the former being described as, ‘completely satisfactory’ but the latter (i.e. embarked division and brigade headquarters) as, ‘a complete failure’.[2] A similar event (Exercise Swordfish) was conducted with 2nd Division the following month, by which time the lessons had been learned and communications were much improved. A third exercise was cancelled in mid-December and Bulolo was ordered back to the Mediterranean. After spending Christmas at Bombay, she sailed for Italy via the Suez Canal.

Bulolo arrived at Naples on 12 January 1944 and immediately embarked Lieutenant Colonel L. T. Shawcross, commanding officer of 1st Divisional Signals. The division had been allocated to United States VI Corps as one of the two assaulting division for Operation Shingle—an amphibious landing at Anzio. The divisional staff and additional signallers embarked over the following days and on 18 January an exercise was carried out in the Salerno area. On 20 January, an interoperability exercise took place with the headquarters ship USS Biscayne, the flagship for the operation, and the following day the assault force sailed for Anzio.[3] The landings were largely unopposed and, from the perspective of the signal section, somewhat routine. The divisional staff disembarked on 23 January and the following day, in the midst of an air attack, Bulolo sailed for Naples and thence to Malta. March 1944 was spent in Algiers and on 7 April the ship’s company prepared to depart the Mediterranean. Prior to sailing a signal was received from Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean that read: ‘Whilst on Mediterranean Station you have played a very active part in operations and may be justly proud of your share in our successes. Goodbye and good luck to you and your ship’s company’.

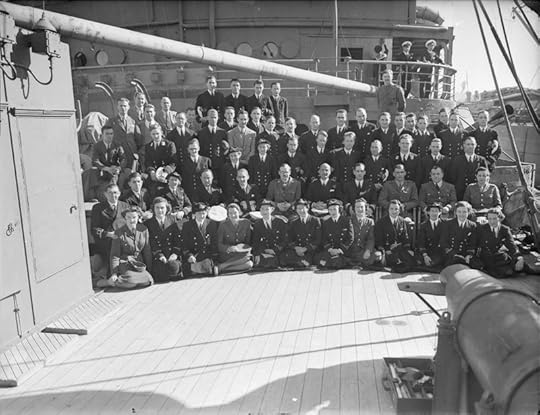

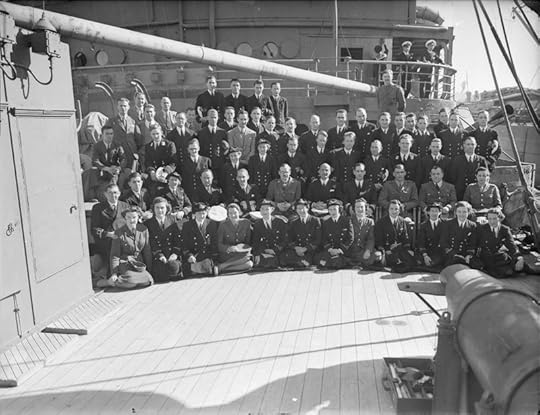

Bulolo was now destined for Portsmouth and a refit in preparation for its next task, the Normandy landings. The refit and various administrative activities took up the rest of the month before the ship sailed for Southampton where it embarked the staff of Commodore Sir Cyril Douglas-Pennant CBE, DSO commanding Task Force ‘G’ and began preparations for the first pre-landings exercise, Exercise Fabius, which also involved the commander and staff of 50th (Northumbrian) Division. Several days later a communications exercise took place with the divisional signals (Exercise Grab) and then with 30th Corps (Exercise Bargepole), and No. 2 Air Support Signal Unit (Exercise Blarney), all of which were successful. Similar exercise followed at the end of the month. The signal section was briefed on the plan for Operation Overlord on 21 May and on 24 May the ship hosted a visit by King George VI, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay KCB, KBE, MVO (Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief), and Rear Admiral Sir Philip Vian KBE, DSO (commanding Eastern Task Force). At the end of the visit the King took the salute at a ‘steam past’ of the landing craft of Force ‘G’.

King George VI taking the salute, 24 May 1944.

On 31 May all of the formation operation orders, codes and cyphers for the landings were received and by 2 June the embarked staffs were complete. On board were the staff of Task Force ‘G’; 50th (Northumbrian) Division (Major General D. A. H. Graham DSO, OBE, MC); and the air staff led by Group Captain W. S. P. Simonds DFC. The subordinate assault groups ‘G.1’ (231st Infantry Brigade) and ‘G.2’ (69th Infantry Brigade) were commanded from HMS Nith (with No 15 Ship Signal Section (Modified) embarked) and HMS Kingsmill (No. 14 Ship Signal Section (Modified)), respectively.[4] The follow-on assault group ‘G.3’ comprised 151st and 56th Infantry Brigades, the headquarters for which were on board HMS Albrighton and Landing Craft Infantry (Large) No. 255, both supported by No. 18 Ship Signal Section (Modified).

HMS Bulolo left Southampton for an anchorage in the mouth of the Beaulieu River on 3 June. In the event, the landings were delayed but on the morning of 5 June D-Day was confirmed as being the next day and the landing craft of Force ‘G’ began to move to convoy stations. The workload for the signal section took a sudden upturn that day with over 400 Top Secret packets being delivered to the message centre for despatch.

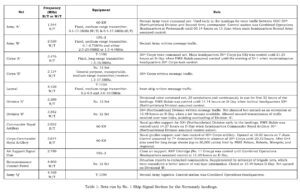

D-Day radio nets (waves) established by No. 1 Ship Signal Section

On D-Day HMS Bulolo sailed with the invasion armada to the French coastline and took up station about six miles off Gold Beach, with the ships providing naval gunfire support arraigned on either flank. Listening watch had been established on the principal nets at 05.30 hours and communications were established as the landing troops opened up on their nets. With the exception of a transmitter fault (soon rectified) on the 30th Corps net, communications from and to Bulolo were excellent throughout the day. Tactical headquarters 50th (Northumbrian) Division proceeded ashore early in the landings and assumed control of the divisional command net at 14.14 hours. Just prior to this, at Hordean at 13.00 hours, the corps commander, Lieutenant General C. G. Bucknall CB, MC, the staff of headquarters 30th Corps, and the GOC’s operators under the command of Second Lieutenant S. Harrison[5] embarked onto HMS Beagle and the destroyer at once sailed for the landing area, where it arrived alongside Bulolo at 18.00 hours. The transfer to Bulolo was complicated by the sea state but by 19.00 hours everyone was on board and the headquarters reconnaissance element was despatched ashore. HMS Bulolo became 30th Corps Main Headquarters at 20.10 hours. Lieutenant General Bucknall went ashore just before midnight. With the arrival of the bulk of the staff and 30th Corps Signals in France the following morning, and after a series of mishaps, the corps headquarters was finally established ashore on the afternoon of 7 June and took control from HMS Bulolo that night.[6]

Damage to HMS Bulolo, 7 June 1944

Tragedy struck on the morning of 7 June. At 06.05 hours a 250-lb bomb dropped by one of three attacking FW-190s hit HMS Bulolo and exploded on the port side, forward of the main support control operations room. In addition to the damage inside the operations room, it started a fire on ‘B’ Deck in the officers’ accommodation. The operations room was filled with smoke, with flames coming through the damaged area caused by the explosion, and the sick-bay on the deck beneath the fire was cut off by dense smoke. The sick-bay was badly positioned for use during action stations, however, and the casualties were taken to emergency medical stations in other parts of the ship. The fires were extinguished by 06.45 hours but two RAF signal officers, an RN cypher officer, and a naval gunner had been killed. The RAF officers were in their shared cabin asleep—Flight Lieutenant Bert Drury was killed outright by the blast, and Flight Lieutenant Ken Gate died of his burns a few hours later. The others killed were Sub-Lieutenant Cyril Oaker and Able Seaman George Young. Injured were a Royal Artillery major and two other officers—including the second-in-command of the signal section, Lieutenant F. E. J. Bishop[7]—two sailors and an RAF corporal.[8] The remains of the dead accompanied by a burial party were transferred to HMS Albrighton the following day and they were buried at sea about 10 miles off Queen Red beach.[9] For their conduct during the attack Flight Lieutenant F. D. Johnstone and Corporal F. B. Isles, the wounded RAF NCO, were mentioned in despatches; both were recommended by Group Captain W. S. P. Simonds DFC, who was also mentioned in despatches for his work leading the Force ‘G’ Air Staff.[10]

HMS Bulolo’s casualties, 7 June 1944

HMS Bulolo remained off Normandy until the afternoon of 27 June when she sailed for Spithead. After disembarking the staff, the ship remained in the Solent until 5 July when she sailed to Greenock pending a full refit and became an operational reserve. At the end of August she returned to Southampton and work on the extensive refit began. On 30 September, Major Kenworthy was replaced in command of No. 1 Ship Signal Section by Major A. W. L. Moon and took up an appointment as senior instructor at the Combined Operations School (HMS Dundonald II) at Troon.[11]

Sergeant P. A. A. Court MM, BEM

At this stage it is worth recording that Major Kenworthy was mentioned in despatches twice for his command of the section; he had done more than almost anyone in the establishment of the ship signal sections.[12] Notably, Sergeant P. A. A. Court, a Scottish-born, former GPO engineer from Derby who had enlisted in March 1940, was awarded the Military Medal, recommended by the captain of HMS Bulolo, Captain C. A. Kershaw, Royal Navy. Added by Rear Admiral Douglas-Pennant to the original recommendation is the phrase: ‘The example set by this NCO in Operation Neptune was of very high order.’[13] The section’s first second-in-command was also mentioned in despatches; Major K. A. Davis was recognised for his command of No. 3 Ship Signal Section aboard HMS Hilary during the Normandy landings.[14]

No. 1 Ship Signal Section spent its time ashore, most at HMS Dundonald, until the refit was complete in May 1945. HMS Bulolo sailed from Southampton for Greenock on 2 June where it began a series of trails and training exercises. Then, on 12 June, Bulolo departed Greenock for its final wartime deployment and sailed via Gibraltar and the Suez Canal to Bombay, where it arrived on 8 July. By the end of the month exercises had begun with 34th Indian Corps, which had been formed in May 1945 in preparation for Operation Zipper—the invasion of Malaya. The maritime task force, Force ‘W’, assembled at Mandapam at the end of August but the Japanese surrender put paid to the plan and a much modified operation to occupy Malaya was implemented. HMS Bulolo was at Singapore for the surrender ceremony on 12 September and the rest of the month was spent off the coast of Malaya, where control of operations was being exercised from HMS Largs and HMS Persimmon. In early October, the decision was taken to put No. 1 Ship Signal Section ashore and after some deliberation (and disagreement) all but an eight-man section were transferred to the SS Matiana for passage to Columbo, with Major Moon and Lieutenant McCarthy despatched to Bombay. The section reported to the shore station at Colombo, HMS Braganza III, pending disbandment and by the end of the year most men had been sent home. The section was disbanded on 19 December 1945. The final operational award to a member of the section was to Sergeant P. A. A. Court MM who was awarded a British Empire Medal for his work in the Far East, and which noted that he had turned down the opportunity for a commission in order to remain with the section.[15]

HMS Bulolo meanwhile had been despatched to Surabaya in Java (now part of Indonesia) to evacuate 500 Dutch civilian internees, mainly women and children. Decommissioned in December 1946, Bulolo returned to the Australian shipping line Burns Philp, her former owners, and continued to serve as a passenger, cargo, and mail carrier in the south Pacific. She was scuttled in 1951 to extinguish cargo fire but was refloated and repaired, continuing to sail until 1968 when she was scrapped in Taiwan.

1. (Back) Also referred to in some sources as 218 Combined Operations Signals. Its units were 220th-223rd Indian Ship Signal Sections, each initially comprising two officers and 35 other ranks.

2. (Back) 29th Infantry Brigade had previously been prepared for an amphibious landing at Akyab (Sittwe) in the Arakan. That operation was finally conducted in January 1945 by 3rd Commando Brigade, which had arrived in India in January 1944 in preparation for such an operation.

3. (Back) The landing of United States 3rd Division was commanded from the converted liner RMS Circassia.

4. (Back) HMS Nith was a converted River class frigate and HMS Kingsmill was a United States-built Captain class frigate, the latter being one of several of that type used as various headquarters ships during the landing. The Ship Signal Sections (Modified) were smaller sections, suited to the requirements of a brigade headquarters, comprising one sergeant and 15 other ranks, mostly operators.

5. (Back) Lieutenant Sidney Harrison was appointed an MBE in June 1945 for his endeavours with 30th Corps Signals reconnaissance headquarters during the North-West European Campaign. (LG 21 June 1945; 37138, p. 3220.) Accompanying him on to HMS Bulolo were the GOC’s operators, Corporal J. Turnbull MM and Signalman J. B. Oldendorp.

6. (Back) The detailed report on communications during Operation Overlord by 30th Corps may be found in the Royal Signal Museum Archive.

7. (Back) Lieutenant Bishop left the ship soon after its return to the United Kingdom and was replaced as second-in-command of No. 1 Ship Signal Section by Second Lieutenant Patrick Pearse Kevin McCarthy (14 July 1916-1999).

8. (Back) For details of the attack and the casualties suffered see: Medical Report of Operation ‘Neptune’, Enclosure No. 2 to Section III to Appendix ‘L’ to Report of Naval Commander Force ‘G’, Medical Report of Operation ‘Neptune’, p. 110. Report by the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force on Operation ‘Neptune’, Volume II.

The other injured personnel were:

Major Peter Holliday DobsonPeter Holliday Dobson, Royal Artillery; Sub-Lieutenant (Special Branch) Frederick James Leedham, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve; D/JX211888 Telegraphist John. W. Robinson, Royal Navy; D/MDX2944 Able Seaman John A Bovill, Royal Navy; and 1519013 Corporal Frank B. Isles, Royal Air Force.

9. (Back) Sub-Lieutenant Cyril Lanham Oaker, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve is commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial; P/JX234664 Able Seaman George Young, Royal Navy is commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial; 115811 Flight Lieutenant Herbert Drury, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve and 115817 Flight Lieutenant Kenneth Gate, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve are commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

10. (Back) All appear in LG 1 January 1945; 36866.

11. (Back) Major Arthur Walter Letcher Moon (6 October 1908-1969) had been commissioned into Royal Signals in July 1941; his pre-war expertise was in submarine cable telegraphy.

12. (Back) LG 9 November 1944; 36785, p. 5131 and LG 19 July 1945; 37184, p. 3728. The former for Normandy, the latter for the landings in Italy.

13. (Back) Military Medal. 2591601 Sergeant Philip Arthur Alden Court, No. 1 Ship Signal Section. Sergeant Court is the senior NCO of No. 1 Ship Signal Section of the Royal Corps of Signals embarked in HMS Bulolo since September 1942. Throughout the landings in North Africa, Sicily and Anzio and finally during Operation Neptune, his zeal, efficiency and devotion to duty have been of the very highest standard, as Army signal office superintendent and traffic controller. Additionally, he has done invaluable work in training the ship signal section and welding them into an efficient unit. The example set by this NCO in Operation Neptune was of very high order. LG 9 November 1944; 36785, p. 5131.

His Royal Air Force counterpart was similarly rewarded:

Distinguished Service Medal. 521022 Flight Sergeant Albert Docherty, Royal Air Force. This airman is the senior non-commissioned officer of the Royal Air Force section embarked in H.M.S. ‘Bulolo’ and has served in the ship since October 1942. During the amphibious operations in North Africa, Sicily and Anzio and, finally, during the landings on the Normandy coast on 6th June 1944, he displayed skill and unremitting devotion to duty as a wireless operator, and set a fine example to his subordinates by his cheerfulness, tact and sound discipline. LG 1 December 1944; 36820, p. 5515.

14. (Back) LG 3 August 1944; 36637, p. 3606.

15. (Back) 2591601 Sergeant Philip Arthur Alden Court MM. LG 6 June 1946; 37595, p. 2734. Recommendation: TNA: WO 373/82/399

October 14, 2022

HMS Bulolo—No. 1 Ship Signal Section, 1942-1945 (Part 1)

In the Summer 2019 edition of the Journal of the Royal Signals Institution, John Young wrote an excellent short history of 661 Signal Troop (LPD). I was prompted to write something about the troop’s predecessor and where it all began—No. 1 Ship Signal Section on HMS Bulolo during the Second World War. The article (somewhat bizarrely attributed to Captain Neil Donaghy, who in fact wrote the update about Project Caduceus) was published in the Journal but (due to another editing error) that version was incomplete and missing its footnotes and some illustrations. The story is told here in two parts…

HMS Bulolo

No. 1 Ship Signal Section was formed aboard HMS Bulolo at Chatham on 16 June 1942.[1] Arising out of the growing understanding of the requirements for effective command of amphibious landings, most importantly the need for a combined[2] headquarters afloat (a lesson learned on Operation Menace—the ill-fated attack on Dakar in 1940), HMS Bulolo was the first of several ships to be converted into a Landing Ship, Headquarters.[3] Designed as a passenger, general cargo and mail steamer, the 6,500-ton ship had piled her trade in the south Pacific for less than a year before war broke out in Europe. Bulolo was requisitioned in September 1939 and converted into an armed merchant cruiser, in which guise she worked as a convoy escort in the Atlantic until being bought by the Admiralty in March 1942. There then followed an extensive period of refitting—the forward cargo hold being converted into a three-deck suite of headquarters staff spaces and communications centres—which was completed that summer and by which time the conversion of a second ship, HMS Largs, had begun.[4] For most of this period, and for the period described here, HMS Bulolo was commanded by Captain R. L. Hamer DSO, the father of Lieutenant Colonel J. R. Hamer, Royal Signals.[5]

The initial establishment of No. 1 Ship Signal Section, the Army component of the tri-service communications staff, was for a major or captain in command (chief signalmaster), a subaltern as second-in-command (signalmaster), four sergeants (signal office superintendents) and 41 junior ranks of various trades. Posted from 11th Armoured Divisional Signals to take command was Captain H. Kenworthy. Like many excellent wartime signallers, Kenworthy had been an employee of the General Post Office before he was commissioned in September 1939; he would return to his post as a traffic superintendent in Preston after the war.[6] His second-in-command was Second Lieutenant K. A. Davis,[7] who joined from 1st Holding Battalion at Scarborough where he had just finished his training after being commissioned six months previously. Amongst the three sergeants who joined was Sergeant P. A. A. Court, who features later in this tale. The first 22 junior ranks also joined in June 1942.

Trade tests and a training programme began immediately, and Bulolo sailed via Sheerness, to load with ammunition, to Greenock where she would be based until the late autumn. From here there was regular movement of personnel to and from the ship and the Royal Signals Wing at the Combined Operations School (HMS Dundonald II) at Troon and for the next few months the men of the signal section would train at their principal tasks and in ship’s routine. On 13 July the section received its first American visitors, a group of US Army signal officers, who were briefed on the internal organisation of the ship and its procedures. From that day the section was ‘affiliated’ to First Army Signals and in August some men from that unit joined to bring the section up to strength.

In addition to controlling the amphibious landing, one of the primary tasks of the headquarters ship was to ensure coordination between the landing forces and supporting close air support. That work was carried out on board by an embarked Army Air Support Control and exercises in this work began in late July.[8] On 17 September a meeting was held on board to discuss procedures; commanding 7 AASC was Major J. D. Profumo MP, the future Secretary of State for War and the leading cast member in the ‘Profumo affair’.[9]

The radio room aboard HMS Bulolo in 1942; in the centre is the duty signalmaster.

On 14 October, HMS Bulolo was joined by Rear Admiral Sir Harold Burrough KBE, CB, DSO and a few days later by Major General Charles W. Ryder, Commanding General of the United States 34th Infantry Division, and Major General V. Evelegh OBE, General Officer Commanding the British 78th Division. On 24 October shore leave was suspended and two days later Admiral Burrough, Major Generals Ryder and Evelegh, and Air Commodore G. M. Lawson CBE, MC (the First Army air liaison officer) briefed the ship’s company on Operation Torch—an amphibious landing on the shores of North Africa. The operation would comprise three landings: The Western Task Force, which had sailed from the United States, would land troops on the Atlantic coast of Morocco; the Centre Task Force, would land at Oran in Algeria; and the Eastern Task Force at Algiers. Admiral Burrough would command the Eastern Task Force, the ground force for that landing being commanded by Major General Ryder.

That night HMS Bulolo sailed and joined a convoy at the mouth of the Clyde, beginning the voyage south to the Straits of Gibraltar under radio silence. On 6 November Bulolo and the accompanying convoy sailed into the Mediterranean and by 22.30 hours on 7 November was 12 miles off Algiers. Radio silence was broken at 01.00 hours the following morning as the landings commenced. The landings met with little opposition and on 9 October Bulolo came into port at Algiers. This somewhat ignominious arrival was at some speed and Bulolo hit the sea wall and a waterfront building due to damage to the engine room telegraph that had occurred the previous day when Bulolo narrowly escaped being hit by bombs dropped during a German air attack; the damage was unknown to the crew and resulted in a bell to the engine room being missed. With the divisional headquarters now ashore, the signal section spent the next few days responding to the demands of various groups of staff officers who required to use its extensive communications suite. A dispatch rider service was set up (using DRs from the two divisions) and on 12 November GOC First Army, Lieutenant General K. A. N. Anderson CB, MC, establish a temporary command post aboard. Although 90% of traffic on the day of the landings had been in plain language, over 23,000 cypher groups had been encoded or decoded by 14 November. On 10 December HMS Bulolo left Algiers in convoy bound for the United Kingdom, where she arrived a week later and where work was immediately started to make good on the lessons learned during Operation Torch.

The next task for HMS Bulolo and its signal section was not an amphibious landing but communications support for the Casablanca conference between the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill. The ship’s company was recalled from leave on 28 December and on 5 January, with a small team from No. 1 Ship Signal Section (one sergeant and 14 other ranks) and escorted by three destroyers, Bulolo sailed for Morocco. The remainder of the section meanwhile remained at HMS Dundonald II. The ship came alongside at Casablanca on 10 January and accepted a five-pair cable that allowed connection to the naval headquarters ashore and to the Anfa Hotel, where the conference was to take place. The lines to the hotel provided for a secure telephone link, a line to the hotel switchboard and a teleprinter circuit. The terminal equipment for the latter was provided by the Americans and a team arrived on board to train the British operators. The section’s war diary records that throughout the conference the telephone traffic was ‘heavy’. On 24 January after the conference the ship’s company was addressed by Churchill, who also toured the signal office and operations rooms. On 27 January Bulolo sailed for the United Kingdom arriving on the last day of the month.

Officers of the cypher staff, including civilians and officers of the WRNS and the ATS, onboard HMS Bulolo for the Casablanca Conference in January 1943.

Meanwhile in Troon, the remainder of the ship’s section had undertaken some intensive training alongside the less experienced men of No. 2 Ship Signal Section destined for HMS Largs. Much of February and March was spent in Liverpool where the ship underwent a refit and when she returned to Greenock in the middle of the month Lieutenant Davis was notified of his promotion and posting to command No. 3 Ship Signal Section. He was replaced by Second Lieutenant F. E. J. Bishop from 47th Divisional Signals.[10] On 16 March, with the full signal section and a detachment from General Headquarters Reconnaissance Regiment (Phantom) HMS Bulolo sailed again, this time via Freetown, Durban and Aden to Adabiya at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez.

On 5 May Captain Kenworthy reported to General Headquarters Middle East in Cairo for a discussion about the future role of the signal section on Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. Reflecting the British force elements that would conduct the initial landing, attending the meeting were Brigadier R. T. O. Cary, Chief Signal Officer Eighth Army, Colonel J. B. Adams, Chief Signal Officer 13th Corps, and the commanding officer of 5th Divisional Signals, Lieutenant Colonel E. L. L. Vulliamy.

The planning for the Sicily landings was fraught with difficulty—principal British and American naval, army and air force commanders and their forces were spread across North Africa and the Middle East, and fighting in Tunisia continued into May 1943 occupying the staffs of the Eighth Army and the United States I Corps (later redesignated as US Seventh Army). There is no space here to expand upon the complexity of the planning for the operation or, indeed, the detail of plan or conduct of the landings. Suffice it to say that, on 10 July 1943 following airborne landings, two task forces would assault the island. The Western Task Force was largely American and the Eastern Task Force was largely British and Canadian. In the Eastern Task Force, the British 13th and 30th Corps would land at four groups of beaches, nicknamed Acid (North and South) and Bark (East, South and West (the western beaches being nicknamed Cent and Dime). The commanders for each landing would be embarked on a headquarters ship:

Acid—on beaches south of Syracuse in the Gulf of Noto—Force ‘A’, HMS Bulolo (Rear Admiral T. H. Troubridge DSO, commanding Force ‘A’; Lieutenant General M. C. Dempsey CB, DSO, MC, commanding 13th Corps; and Major General H. P. M. Berney-Ficklin CB, MC, commanding 5th Division).

Bark East—on the east of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘N’, HMS Keren.[11]

Bark South—on the end of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘B’, HMS Largs.

Bark West—on the west of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘V’, HMS Hilary.[12]

In his account of life as a junior Naval officer in the Mediterranean, Sub-Lieutenant F. Wade, who served as a cypher officer on HMS Bulolo in this period recalled:

‘Our masts bristled with radio and radar aerials. The forward cargo hold had been modified to house a complete interservice headquarters. The hull in this part of the ship had been strengthened to withstand a direct hit. The hold itself was divided into three decks. The lowest deck, where I would work, was given over to communications and housed army, navy and air force cypher and code rooms, and W/T receiving and transmitting rooms. The Main Signal Distributing Room was right in the centre. This was manned exclusively by naval personnel but from here messages were dispersed for all three services to the Operations Room on the next deck above…

The Operations or Support Control Room deck, as it was called, contained three signal filtering rooms, one each for Navy Ops, Army Intelligence and the RAF filter room, with the main Support Control Room in the centre. The main room was what I had always imagined a huge operations room to be. It was dominated by a large map of Sicily, about twenty feet square, parallel to the deck and raised off the floor like a huge table. Around it would stand the plotters moving little markers showing the disposition of the three forces. Large notice boards were mounted on the bulkheads, containing lists which constantly had to be updated. high above was a balcony which gave the senior officers a panoramic view of the place…

There was also an adjacent room behind a glass wall which served as the Fighter Control Room compartment. Our fighter aircraft cover was to be directed from here until a control centre could be set up ashore. Likewise, the generals would control their forces ashore from this room until they could land their own headquarters staff. It was estimated that these rooms would be used for three or four days after the assault, depending upon how well the landings went. The top deck contained rooms for the senior officers.’[13]

On 13 May GOC 5th Division visited, and work was put in hand to make the various changes to the operations room that he required. A few days later, operators from 5th Divisional Signals joined and after briefings they were sent to run equipment in the troopships, Reina del Pacifico and Duchess of Bedford. Exercises were conducted every day until 7 June when the staff of 5th Division joined the ship. The 13th Corps staff arrived the following day and there followed a series of exercises with the staff in message handling. A pigeon loft arrived onboard 10 June. On the final exercise communications proved satisfactory ‘more or less’ except for the pigeons, all but two of which were lost—‘on being tossed immediately assumed low level flying, apparently in search of LCTs on which they had been trained’.[14] On 23 June after a final ‘netting’ exercise all the Army outstation radios were closed down.

On 30 June HMS Bulolo sailed through the Suez Canal to Port Said, complete with a new compliment of pigeons, which being better settled performed well. Finally, on 5 July Bulolo sailed for Sicily with the Eastern Task Force and in the early hours of 10 July the landings commenced and during which Bulolo lay offshore south of Syracuse. By 11.00 hours that morning GOC 5th Division was ashore and on 15 July, with 13th Corps tactical headquarters now ashore, Army communications were closed down and Bulolo sailed for Syracuse harbour.[15] Two days later she sailed for Malta, her part in the operation over, and the men of the section enjoyed a day of shore leave. HMS Bulolo then returned to Alexandria.[16]

After a period of planning for an operation in the Aegean Sea that was ultimately cancelled (Operation Accolade—landings on Rhodes and the Dodecanese islands), HMS Bulolo and No. 1 Ship Signal Section sailed again, this time bound for Bombay (Mumbai) which she reached on 17 September, the first of two trips the ship made to south Asia.

1. (Back) The section was officially established, however, on 10 June as ‘Force Headquarters, Ship Signal Section’. The story here is derived largely from the section’s war diaries. See: The National Archives (TNA): WO 257/1 and WO 257/2.

2. (Back) In the early stages of the Second World War the term ‘combined’ was used to mean multi-service (today ‘joint’); it is used in that way here.

3. (Back) For a detailed account of the Dakar affair, including much detail on the requirement for and failure of the combined (joint) and Anglo-Free French communications see Marder, A. J. (2016). Operation Menace: The Dakar Expedition and the Dudley North Affair. Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

4. (Back) HMS Largs was a former French Line banana boat, MV Charles Plumier seized at Gibraltar in 1940 and which had spent some time as an ocean boarding vessel. She became the home to No. 2 Ship Signal Section.

5. (Back) Captain Richard Lloyd Hamer DSO (13 January 1884-16 December 1951), commanded HMS Bulolo from October 1940 to December 1943. He had served throughout the First World War (Order of the Nile, Fourth Class) before retiring in 1923 and had been awarded the Royal Humane Society Bronze Medal in 1920. Recalled on the outbreak of the Second World War, he earned his DSO for a successful attack on a U-Boat while in command of the armed yacht HMS Viva II in June 1940. Lieutenant Colonel John Richard Hamer (19 December 1920-16 August 2011) was commissioned into Royal Signals in April 1942. He was mentioned in despatches in 1945 for his conduct in the North-West Europe Campaign with 56th Independent Infantry Brigade Signal Section. He retired in 1968.

6. (Back) Major Harold Kenworthy (17 June 1906-2 April 1987), Officer Commanding No. 1 Ship Signal Section, June 1942-September 1944.

7. (Back) Second Lieutenant (later Major) Kenneth Austen Davis (11 February 1912-6 June 1986). Later Officer Commanding No. 3 Ship Signal Section aboard HMS Hilary, for which he was mentioned in despatches for his conduct during the Normandy landings.

8. (Back) The assigned unit was No. 7 Army Air Support Control.

9. (Back) In most references Profumo’s military career during the war is glossed over, ignored, or incorrect. He proved to be a most able officer during Operation Torch, in the fighting in Tunisia and, for the remainder of the war, on the staff. Commissioned into the Royal Armoured Corps Territorial Army in July 1939 Profumo joined The Northamptonshire Yeomanry, a light tank regiment equipped with Guy armoured cars, and later came to specialise in air support operations. For his command of 7 AASC during the landings in North Africa he was mentioned in despatches (London Gazette (LG) 23 September 1943; 36180, p. 4222). On leaving 7 AASC in November 1943, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and joined the staff of Headquarters 15th Army Group (later renamed Allied Armies in Italy) as chief of the air liaison sub-section of the operations staff, responsible for the development of standard procedures for air support to the United States Fifth Army and the British Eighth Army. For his success in this he was made OBE in November 1944 (LG 21 December 1944; 36850, p. 5844. Recommendation: TNA: WO 373/72/93.) and awarded the United States Bronze Star Medal (LG 11 November 1947; 38122, p. 5353. Recommendation: TNA: WO 373/148/319.). Contrary to many accounts, Profumo did not take part in the D-Day landings but remained on the staff in Italy throughout 1944 and 1945.

10. (Back) Second Lieutenant (later Major) Frank Ernest John Bishop (20 September 1912-7 January 1981), wounded in action on 7 June 1944 (see Part 2) and posted to Combined Operations Headquarters.

11. (Back) HMS Keren was a liner, formerly the MV Kenya built in 1930 for the British India Company, converted into a Landing Ship, Infantry. She was not a true headquarters ship in the style of the others but had enough of a communications suite to allow command of the small naval and landing force (231st (Malta) Infantry Brigade).

12. (Back) HMS Hilary was a former British steam passenger liner, built in 1931. Like Largs, she began her war as an ocean boarding vessel before being converted into a Landing Ship, Infantry (Headquarters). She became the home of No. 3 Ship Signal Section.

13. (Back) Wade, F. (2005). A Midshipman’s War: A Young Man in the Mediterranean Naval War 1941-1943. Bloomington: Trafford Publishing. pp. 195-196.

14. (Back) Pigeons were kept aboard for nine months from May 1943 to January 1944, although they were used only during operation Husky. The pigeon service in the Mediterranean, under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel J. A. Hollingworth, proved extraordinarily successful in almost every campaign across the theatre.

15. (Back) The section war diary (TNA: WO 257/1) contains a short report on the operation that includes the radio nets established and their performance.

16. (Back) For more detail on Operation Husky see the despatches:

‘The Conquest of Sicily from 10th July 1943 to 17th August 1943.’ LG 12 February 1948; 38205.

‘The Invasion of Sicily.’ LG 28 April 1950; 38895.

HMS Bulolo—No. 1 Ship Signal Section, 1942-1945

In the Summer 2019 edition of the Journal of the Royal Signals Institution, John Young wrote an excellent short history of 661 Signal Troop (LPD). I was prompted to write something about the troop’s predecessor and where it all began—No. 1 Ship Signal Section on HMS Bulolo during the Second World War. The article (somewhat bizarrely attributed to Captain Neil Donaghy, who in fact wrote the update about Project Caduceus) was published in the Journal but (due to another editing error) that version was incomplete and missing its footnotes and some illustrations. The story is told here in two parts…

HMS Bulolo

No. 1 Ship Signal Section was formed aboard HMS Bulolo at Chatham on 16 June 1942.[1] Arising out of the growing understanding of the requirements for effective command of amphibious landings, most importantly the need for a combined[2] headquarters afloat (a lesson learned on Operation Menace—the ill-fated attack on Dakar in 1940), HMS Bulolo was the first of several ships to be converted into a Landing Ship Headquarters.[3] Designed as a passenger, general cargo and mail steamer, the 6,500-ton ship had piled her trade in the south Pacific for less than a year before war broke out in Europe. Bulolo was requisitioned in September 1939 and converted into an armed merchant cruiser, in which guise she worked as a convoy escort in the Atlantic until being bought by the Admiralty in March 1942. There then followed an extensive period of refitting—the forward cargo hold being converted into a three-deck suite of headquarters staff spaces and communications centres—which was completed that summer and by which time the conversion of a second ship, HMS Largs, had begun.[4] For most of this period, and for the period described here, HMS Bulolo was commanded by Captain R. L. Hamer DSO, the father of Lieutenant Colonel J. R. Hamer, Royal Signals.[5]

The initial establishment of No. 1 Ship Signal Section, the Army component of the tri-service communications staff, was for a major or captain in command (chief signalmaster), a subaltern as second-in-command (signalmaster), four sergeants (signal office superintendents) and 41 junior ranks of various trades. Posted from 11th Armoured Divisional Signals to take command was Captain H. Kenworthy. Like many excellent wartime signallers, Kenworthy had been an employee of the General Post Office before he was commissioned in September 1939; he would return to his post as a traffic superintendent in Preston after the war.[6] His second-in-command was Second Lieutenant K. A. Davis,[7] who joined from 1st Holding Battalion at Scarborough where he had just finished his training after being commissioned six months previously. Amongst the three sergeants who joined was Sergeant P. A. A. Court, who features later in this tale. The first 22 junior ranks also joined in June 1942.

Trade tests and a training programme began immediately, and Bulolo sailed via Sheerness, to load with ammunition, to Greenock where she would be based until the late autumn. From here there was regular movement of personnel to and from the ship and the Royal Signals Wing at the Combined Operations School (HMS Dundonald II) at Troon and for the next few months the men of the signal section would train at their principal tasks and in ship’s routine. On 13 July the section received its first American visitors, a group of US Army signal officers, who were briefed on the internal organisation of the ship and its procedures. From that day the section was ‘affiliated’ to First Army Signals and in August some men from that unit joined to bring the section up to strength.

In addition to controlling the amphibious landing, one of the primary tasks of the headquarters ship was to ensure coordination between the landing forces and supporting close air support. That work was carried out on board by an embarked Army Air Support Control and exercises in this work began in late July.[8] On 17 September a meeting was held on board to discuss procedures; commanding 7 AASC was Major J. D. Profumo MP, the future Secretary of State for War and the leading cast member in the ‘Profumo affair’.[9]

The radio room aboard HMS Bulolo in 1942; in the centre is the duty signalmaster.

On 14 October, HMS Bulolo was joined by Rear Admiral Sir Harold Burrough KBE, CB, DSO and a few days later by Major General Charles W. Ryder, Commanding General of the United States 34th Infantry Division, and Major General V. Evelegh OBE, General Officer Commanding the British 78th Division. On 24 October shore leave was suspended and two days later Admiral Burrough, Major Generals Ryder and Evelegh, and Air Commodore G. M. Lawson CBE, MC (the First Army air liaison officer) briefed the ship’s company on Operation Torch—an amphibious landing on the shores of North Africa. The operation would comprise three landings: The Western Task Force, which had sailed from the United States, would land troops on the Atlantic coast of Morocco; the Centre Task Force, would land at Oran in Algeria; and the Eastern Task Force at Algiers. Admiral Burrough would command the Eastern Task Force, the ground force for that landing being commanded by Major General Ryder.

That night HMS Bulolo sailed and joined a convoy at the mouth of the Clyde, beginning the voyage south to the Straits of Gibraltar under radio silence. On 6 November Bulolo and the accompanying convoy sailed into the Mediterranean and by 22.30 hours on 7 November was 12 miles off Algiers. Radio silence was broken at 01.00 hours the following morning as the landings commenced. The landings met with little opposition and on 9 October Bulolo came alongside in Algiers, having narrowly escaped being hit by bombs dropped during German air attacks. With the divisional headquarters now ashore, the signal section spent the next few days responding to the demands of various groups of staff officers who required to use its extensive communications suite. A dispatch rider service was set up (using DRs from the two divisions) and on 12 November GOC First Army, Lieutenant General K. A. N. Anderson CB, MC, establish a temporary command post aboard. Although 90% of traffic on the day of the landings had been in plain language, over 23,000 cypher groups had been encoded or decoded by 14 November. On 10 December HMS Bulolo left Algiers in convoy bound for the United Kingdom, where she arrived a week later and where work was immediately started to make good on the lessons learned during Operation Torch.

The next task for HMS Bulolo and its signal section was not an amphibious landing but communications support for the Casablanca conference between the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill. The ship’s company was recalled from leave on 28 December and on 5 January, with a small team from No. 1 Ship Signal Section (one sergeant and 14 other ranks) and escorted by three destroyers, Bulolo sailed for Morocco. The remainder of the section meanwhile remained at HMS Dundonald II. The ship came alongside at Casablanca on 10 January and accepted a five-pair cable that allowed connection to the naval headquarters ashore and to the Anfa Hotel, where the conference was to take place. The lines to the hotel provided for a secure telephone link, a line to the hotel switchboard and a teleprinter circuit. The terminal equipment for the latter was provided by the Americans and a team arrived on board to train the British operators. The section’s war diary records that throughout the conference the telephone traffic was ‘heavy’. On 24 January after the conference the ship’s company was addressed by Churchill, who also toured the signal office and operations rooms. On 27 January Bulolo sailed for the United Kingdom arriving on the last day of the month.

Officers of the cypher staff, including civilians and officers of the WRNS and the ATS, onboard HMS Bulolo for the Casablanca Conference in January 1943.

Meanwhile in Troon, the remainder of the ship’s section had undertaken some intensive training alongside the less experienced men of No. 2 Ship Signal Section destined for HMS Largs. Much of February and March was spent in Liverpool where the ship underwent a refit and when she returned to Greenock in the middle of the month Lieutenant Davis was notified of his promotion and posting to command No. 3 Ship Signal Section. He was replaced by Second Lieutenant F. E. J. Bishop from 47th Divisional Signals.[10] On 16 March, with the full signal section and a detachment from General Headquarters Reconnaissance Regiment (Phantom) HMS Bulolo sailed again, this time via Freetown, Durban and Aden to Adabiya at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez.

On 5 May Captain Kenworthy reported to General Headquarters Middle East in Cairo for a discussion about the future role of the signal section on Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. Reflecting the British force elements that would conduct the initial landing, attending the meeting were Brigadier R. T. O. Cary, Chief Signal Officer Eighth Army, Colonel J. B. Adams, Chief Signal Officer 13th Corps, and the commanding officer of 5th Divisional Signals, Lieutenant Colonel E. L. L. Vulliamy.

The planning for the Sicily landings was fraught with difficulty—principal British and American naval, army and air force commanders and their forces were spread across North Africa and the Middle East, and fighting in Tunisia continued into May 1943 occupying the staffs of the Eighth Army and the United States I Corps (later redesignated as US Seventh Army). There is no space here to expand upon the complexity of the planning for the operation or, indeed, the detail of plan or conduct of the landings. Suffice it to say that, on 10 July 1943 following airborne landings, two task forces would assault the island. The Western Task Force was largely American and the Eastern Task Force was largely British and Canadian. In the Eastern Task Force, the British 13th and 30th Corps would land at four groups of beaches, nicknamed Acid (North and South) and Bark (East, South and West (the western beaches being nicknamed Cent and Dime). The commanders for each landing would be embarked on a headquarters ship:

Acid—on beaches south of Syracuse in the Gulf of Noto—Force ‘A’, HMS Bulolo (Rear Admiral T. H. Troubridge DSO, commanding Force ‘A’; Lieutenant General M. C. Dempsey CB, DSO, MC, commanding 13th Corps; and Major General H. P. M. Berney-Ficklin CB, MC, commanding 5th Division).

Bark East—on the east of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘N’, HMS Keren.[11]

Bark South—on the end of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘B’, HMS Largs.

Bark West—on the west of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘V’, HMS Hilary.[12]

In his account of life as a junior Naval officer in the Mediterranean, Sub-Lieutenant F. Wade, who served as a cypher officer on HMS Bulolo in this period recalled:

‘Our masts bristled with radio and radar aerials. The forward cargo hold had been modified to house a complete interservice headquarters. The hull in this part of the ship had been strengthened to withstand a direct hit. The hold itself was divided into three decks. The lowest deck, where I would work, was given over to communications and housed army, navy and air force cypher and code rooms, and W/T receiving and transmitting rooms. The Main Signal Distributing Room was right in the centre. This was manned exclusively by naval personnel but from here messages were dispersed for all three services to the Operations Room on the next deck above…

The Operations or Support Control Room deck, as it was called, contained three signal filtering rooms, one each for Navy Ops, Army Intelligence and the RAF filter room, with the main Support Control Room in the centre. The main room was what I had always imagined a huge operations room to be. It was dominated by a large map of Sicily, about twenty feet square, parallel to the deck and raised off the floor like a huge table. Around it would stand the plotters moving little markers showing the disposition of the three forces. Large notice boards were mounted on the bulkheads, containing lists which constantly had to be updated. high above was a balcony which gave the senior officers a panoramic view of the place…

There was also an adjacent room behind a glass wall which served as the Fighter Control Room compartment. Our fighter aircraft cover was to be directed from here until a control centre could be set up ashore. Likewise, the generals would control their forces ashore from this room until they could land their own headquarters staff. It was estimated that these rooms would be used for three or four days after the assault, depending upon how well the landings went. The top deck contained rooms for the senior officers.’[13]

On 13 May GOC 5th Division visited, and work was put in hand to make the various changes to the operations room that he required. A few days later, operators from 5th Divisional Signals joined and after briefings they were sent to run equipment in the troopships, Reina del Pacifico and Duchess of Bedford. Exercises were conducted every day until 7 June when the staff of 5th Division joined the ship. The 13th Corps staff arrived the following day and there followed a series of exercises with the staff in message handling. A pigeon loft arrived onboard 10 June. On the final exercise communications proved satisfactory ‘more or less’ except for the pigeons, all but two of which were lost—‘on being tossed immediately assumed low level flying, apparently in search of LCTs on which they had been trained’.[14] On 23 June after a final ‘netting’ exercise all the Army outstation radios were closed down.

On 30 June HMS Bulolo sailed through the Suez Canal to Port Said, complete with a new compliment of pigeons, which being better settled performed well. Finally, on 5 July Bulolo sailed for Sicily with the Eastern Task Force and in the early hours of 10 July the landings commenced and during which Bulolo lay offshore south of Syracuse. By 11.00 hours that morning GOC 5th Division was ashore and on 15 July, with 13th Corps tactical headquarters now ashore, Army communications were closed down and Bulolo sailed for Syracuse harbour.[15] Two days later she sailed for Malta, her part in the operation over, and the men of the section enjoyed a day of shore leave. HMS Bulolo then returned to Alexandria.[16]

After a period of planning for an operation in the Aegean Sea that was ultimately cancelled (Operation Accolade—landings on Rhodes and the Dodecanese islands), HMS Bulolo and No. 1 Ship Signal Section sailed again, this time bound for Bombay (Mumbai) which she reached on 17 September, the first of two trips the ship made to south Asia.

(To be continued.)

1. (Back) The section was officially established, however, on 10 June as ‘Force Headquarters, Ship Signal Section’. The story here is derived largely from the section’s war diaries. See: The National Archives (TNA): WO 257/1 and WO 257/2.

2. (Back) In the early stages of the Second World War the term ‘combined’ was used to mean multi-service (today ‘joint’); it is used in that way here.

3. (Back) For a detailed account of the Dakar affair, including much detail on the requirement for and failure of the combined (joint) and Anglo-Free French communications see Marder, A. J. (2016). Operation Menace: The Dakar Expedition and the Dudley North Affair. Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

4. (Back) HMS Largs was a former French Line banana boat, MV Charles Plumier seized at Gibraltar in 1940 and which had spent some time as an ocean boarding vessel. She became the home to No. 2 Ship Signal Section.

5. (Back) Captain Richard Lloyd Hamer DSO (13 January 1884-16 December 1951), commanded HMS Bulolo from October 1940 to December 1943. He had served throughout the First World War (Order of the Nile, Fourth Class) before retiring in 1923 and had been awarded the Royal Humane Society Bronze Medal in 1920. Recalled on the outbreak of the Second World War, he earned his DSO for a successful attack on a U-Boat while in command of the armed yacht HMS Viva II in June 1940. Lieutenant Colonel John Richard Hamer (19 December 1920-16 August 2011) was commissioned into Royal Signals in April 1942. He was mentioned in despatches in 1945 for his conduct in the North-West Europe Campaign with 56th Independent Infantry Brigade Signal Section. He retired in 1968.

6. (Back) Major Harold Kenworthy (17 June 1906-2 April 1987), Officer Commanding No. 1 Ship Signal Section, June 1942-September 1944.

7. (Back) Second Lieutenant (later Major) Kenneth Austen Davis (11 February 1912-6 June 1986). Later Officer Commanding No. 3 Ship Signal Section aboard HMS Hilary, for which he was mentioned in despatches for his conduct during the Normandy landings.

8. (Back) The assigned unit was No. 7 Army Air Support Control.

9. (Back) In most references Profumo’s military career during the war is glossed over, ignored, or incorrect. He proved to be a most able officer during Operation Torch, in the fighting in Tunisia and, for the remainder of the war, on the staff. Commissioned into the Royal Armoured Corps Territorial Army in July 1939 Profumo joined The Northamptonshire Yeomanry, a light tank regiment equipped with Guy armoured cars, and later came to specialise in air support operations. For his command of 7 AASC during the landings in North Africa he was mentioned in despatches (London Gazette (LG) 23 September 1943; 36180, p. 4222). On leaving 7 AASC in November 1943, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and joined the staff of Headquarters 15th Army Group (later renamed Allied Armies in Italy) as chief of the air liaison sub-section of the operations staff, responsible for the development of standard procedures for air support to the United States Fifth Army and the British Eighth Army. For his success in this he was made OBE in November 1944 (LG 21 December 1944; 36850, p. 5844) and awarded the United States Bronze Star Medal (LG 11 November 1947; 38122, p. 5353). Contrary to many accounts, Profumo did not take part in the D-Day landings but remained on the staff in Italy throughout 1944 and 1945.

10. (Back) Second Lieutenant (later Major) Frank Ernest John Bishop (20 September 1912-7 January 1981), wounded in action on 7 June 1944 (see Part 2) and posted to Combined Operations Headquarters.

11. (Back) HMS Keren was a liner, formerly the MV Kenya built in 1930 for the British India Company, converted into a Landing Ship, Infantry. She was not a true headquarters ship in the style of the others but had enough of a communications suite to allow command of the small naval and landing force (231st (Malta) Infantry Brigade).

12. (Back) HMS Hilary was a former British steam passenger liner, built in 1931. Like Largs, she began her war as an ocean boarding vessel before being converted into a Landing Ship, Infantry (Headquarters). She became the home of No. 3 Ship Signal Section.

13. (Back) Wade, F. (2005). A Midshipman’s War: A Young Man in the Mediterranean Naval War 1941-1943. Bloomington: Trafford Publishing. pp. 195-196.

14. (Back) Pigeons were kept aboard for nine months from May 1943 to January 1944, although they were used only during operation Husky. The pigeon service in the Mediterranean, under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel J. A. Hollingworth, proved extraordinarily successful in almost every campaign across the theatre.

15. (Back) The section war diary (TNA: WO 257/1) contains a short report on the operation that includes the radio nets established and their performance.

16. (Back) For more detail on Operation Husky see the despatches:

‘The Conquest of Sicily from 10th July 1943 to 17th August 1943.’ LG 12 February 1948; 38205.

‘The Invasion of Sicily.’ LG 28 April 1950; 38895.

October 12, 2022

Sergeant Henry James ‘Harry’ May, 2nd Divisional Signals, Burma

The Mention in Despatches is arguably the United Kingdom’s oldest form of recognition for gallantry or meritorious service on operations. The inclusion of the names of those worthy of being brought to the attention of the Admiralty or War Office became well-established in the 19th Century. An excellent, early example is the ‘mention’ of Serjeant Moore of His Majesty’s 86th Regiment of Foot for his leadership of a forlorn hope in the assault at Bharuch on 29 August 1803 during the Second Anglo-Maratha War, which appeared in the London Gazette in April 1804.[1]

Unfortunately, in the modern era these awards are the most difficult to research. Even with information from a recipient’s family, service records and unit war diaries, the reason for the majority of mentions is impossible to determine.

During my research into Royal Signals honours and awards (there have been around 6,200 Mentions in Despatches to personnel of the Corps), I was contacted by the family of a Royal Signals sergeant who was mentioned for his conduct during the Burma campaign in the Second World War. Notwithstanding the wealth of information about him, we have been unable to track down any details of his award but his story is worth telling.

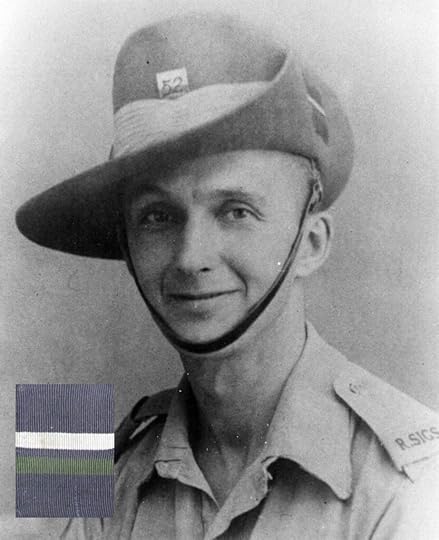

Corporal Henry James ‘Harry’ May before sailing for India

Harry May was born in Glasgow on 22 August 1913. He worked as a clerk and he was a pre-war Territorial Army solder. He had enlisted on 20 April 1939, just after the announcement that the Territorial Amy would be doubled in size, and joined 52nd (Lowland) Divisional Signals. He attended summer camp just prior to the outbreak of war, and was mobilised on 2 September and posted to the newly reformed 15th (Scottish) Division. By trade he was an ‘operator wireless and line’, an ‘OWL’. In April 1940, he was promoted to lance corporal and a bit over a month later to corporal. In June he was posted to No. 1 Company, 2nd Divisional Signals; it was with this unit that he would see out the rest of the war.

The division had just escaped from the beaches of Dunkirk and was based now in Yorkshire, where it was refitting and preparing to counter a German invasion. Harry May spent two years in Yorkshire during which time he was introduced to Frances, the sister of one of his friends, Alwyn Simpson. The Simpsons lived on Kirkland Street in Pocklington and Harry and Frances became a couple.

Japan attacked Pearl Harbour on 7 December and several hours later attacked Hong Kong. Burma was invaded in January 1942 and by April the British forces had retreated into India. Three British infantry divisions were sent out to reinforce India: 70th Division, which was disbanded in 1943 when its units were transferred to Special Force—the Chindits; 5th Division, which was sent to the Middle East after only three months; and 2nd Division.

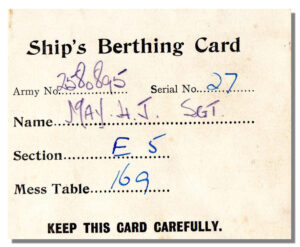

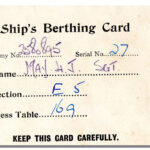

Harry May’s berthing card for the ‘cruise’ to India

The 2nd Division, including the Divisional Signals under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Claude Fairweather,[2] was originally destined for Suez and the 8th Army and it departed the United Kingdom in April 1942 amongst a large convoy.[3] Protected by its escorts, the convoy sailed far out into the Atlantic and then south to Cape Town, where everyone enjoyed some time ashore. Diverted to India, the division arrived in Bombay (Mumbai) on 7 June and, after a period of training at Poona (Pune), moved to Ahmednagar where it conducted jungle training until committed to operations in April 1944 as part of 14th Army. Most famously, the division fought at Kohima and in the actions to open the Imphal Road before taking part in the hard fighting through central Burma. The division was withdrawn to India in March 1945 for refitting.

Sergeant Harry May